* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Illustrated Quebec

Date of first publication: 1893

Author: Graeme Mercer Adam, 1830-1912

Date first posted: Jan. 19, 2018

Date last updated: Jan. 19, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180131

This eBook was produced by: Brenda Lewis, David T. Jones, Alex White, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in 2009 with funding from

Ontario Council of University Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/illustratedquebe00adam

The Transcriber's Notes are placed at the end of this document.

1535-1608 : 1763-1893

Illustrated

QUEBEC,

(The Gibraltar and Tourists' Mecca of America)

Under French and English Occupancy:

THE STORY OF ITS FAMOUS ANNALS;

WITH PEN PICTURES DESCRIPTIVE OF THE MATCHLESS BEAUTY AND QUAINT MEDIÆVAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE

CANADIAN GIBRALTAR,

By G. M. ADAM.

With an Introduction by Arthur G. Doughty, M.A., and supplementary Chapters by J. M. Lemoine, F.R.S.C.

|

SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS IN CANADA. |

PUBLISHED BY JOHN McCONNIFF. Union Ticket Agent. Office: Rotunda, Windsor Hotel, MONTREAL |

DESBARATS & CO., ENGRAVERS, PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS, MONTREAL. |

Entered, according to Act of Parliament of Canada, in the year 1891, by John McConniff, at the Department of Agriculture, Ottawa

To all old Friends; to those who dwell

Secure in yonder Citadel.

To old Quebec, whose glorious fame

Few cities of to-day can claim.

Quebec! Past, Present and to Be,

Greeting: Our pen shall tell of Thee.

n the contemplation of the matchless panorama spread out under a Canadian sky, the varied and unceasing loveliness of nature passes before the eye like some vast train of meteoric splendour, enchanting the imagination with its beauty and grandeur. It is true that the field is being gradually narrowed by the onward march of progress and invention which has done much to despoil the beauties of the past, and we may sometimes wish that we could hear the murmur of the gentle rivulet, where the engine now tears on its mad career, that we could listen to the song of the peasant boy wending his way homeward in streets that are now the centres of busy commerce. The domain of our fair Dominion, however, is so broad, that on either hand we may find a lavish display of Nature's art, unadorned by the heedless hand of man. But civilization while robbing us of some few natural charms often gives something in return; the events which followed in its train have given to us an historic past, in which deeds of heroism and valor stand out conspicuously. Around the quaint old city of Quebec, the cradle of Canada, is gathered much of what has ennobled her. Here shrouded in the frame work of an entrancing landscape are the spots consecrated by the lives and deaths of her worthies.

Quebec seems to have been specially formed by Nature for the important part assigned to her in the drama on this continent. Deeds of heroism, of religious fervour, of obstinate defence, are her pride, her natural complement. Perched upon a commanding eminence, which rises in grandeur and strength from its watery bed, it forms a fitting memorial, as well as the sentry of Canada and the keystone of an empire that has past.

That pristine glory when, from its rugged height, the eye could take in a boundless stretch of unsophisticated nature, while "Canada, as a virgin goddess in a primeval world, walked in unconscious beauty among her golden woods and along the margin of her trackless streams," has departed, but who would barter even those gorgeous scenes for the pages inscribed in letters of gold in the annals of Quebec?

Full of glowing memories is the ancient city which binds us together so strongly with the past. Religious zeal, martial and naval combat, the politician's wiles, Old World refinement, New World barbarity, each furnish a tint, bright or sombre, to the picture of its infancy.

Conquest, change of rule, modern progress, have left their impress upon thee, quaint old Quebec, since the clays of thy noble founder Champlain. Startling scenes have been enacted within thy staunch bastions. Once the silver toned Vesper bell and the solemn chant of white robed priest, was drowned in the deafening roar of cannon and the bursting of murderous shell upon the Heights of Abraham; once in the gray dawn of a September morn, the hearts of two of the noblest sons of France and England were flushed with the assurance of victory, but before the setting of the sun, the verdure of thy pleasant fields, red with the blood of illustrious dead, bore silent token to the truth, that—

"The path of glory leads but to the grave."

It needs no pen to tell the glory of their death, no song to rescue their deeds from the dark oblivion of a tearless grave. Silently, morn and eve, in noonday heat, in biting frost, that granite column in the Governor's garden points aloft its finger to the sky, telling of "Wolfe and Montcalm." Vanquisher and vanquished lie silent in the tomb, but their names are linked together, bound in a wreath of indissoluble glory.

"Sunt lachrymæ rerum, et mentem mortalia tangunt."

Changed, and not changed is old Quebec. There is still a more potent charm than the memory of what she has been, in the fact that much remains to-day, as when the events which have immortalized here were being worked out.

Imposing in the magnificence of its situation, captivating in its picturesqueness, and classic in its memories, Quebec has no rival in the New World.

Much has been told, in prose and verse, of the grandness of the view from the Citadel, in the bursting of the springtide, of the dazzling sheen of the noonday heat, of the matchless hues of autumnal tints; but surely the views of summer have never eclipsed the picture presented to our vision one clear moonlight night in January. Looking down from the giddy heights on to the tops of the houses tumbled together in wild incongruity, with here and there a light flashing from a window, or the red glare of a stove indicating that all was life and cheer within, we could not help contrasting it with the summer picture. How sharp the contrast! The bosom of the mighty river held fast in the grasp of icy winter, the city hushed in the silence of the night, and, over all, rich and poor, hut or palace, temple or cot, was cast the spotless mantle of snow. The glorious landscape that gladdened our eyes at harvest had donned its winter garb, and every roof and fane, every tree and shrub shrouded in icy cerements, which no human hand or artifice could imitate, formed in the silver light of the moon a picture of fairy-like magnificence.

The object of this little work is to set before the tourist and the student, those natural and artificial beauties, which are seldom found in greater profusion than in the city of Quebec and its immediate vicinity, and to present him with a volume that may prove reliable as a guide or acceptable as a souvenir.

But enough, our task is done. In these few words have we introduced thee, curious old Quebec, to the Modern Reader; leaving thy frowning battlements and winding streets of quaint gables pervaded with the historic atmosphere of departed centuries to speak to him of days for ever past—of days when alternate hope and despair filled the breasts of thy brave pioneers as they heroically struggled against hostile fleets and savage foes without, and biting famine and wasting distress within, trusting mainly to thy magnificent strength for victory and the empire of a great continent; of days which crowned "thy clergy and sisterhoods with the aureole of martyrdom," the guerdon of whose labors is the consummation of legislative and scholastic influence which has rolled onward over vast prairies and inland seas to the great sunset ocean; of days which nurtured thy offspring for the proud position awaiting them in the "Olympus of Nations"—of days, the glory of which based upon the principles of eternal truth, will survive long after thy foundations lie crumbling in the dust.

"Quaint old town of toil and traffic,

Quaint old town of art and song,

"Memories haunt thy pointed gables,"—

Noble deeds around thee throng.

on the continent of the New World has Nature done more for any city than she has done for Quebec. Its majestic situation and marvellous scenic environment commands universal admiration. Well may Jacques Cartier's pilot have exclaimed "Quel bec!" (what a beak) as he first

looked upon its frowning forest-covered height, though we must be careful not to receive the Norman sailor's phrase as the accredited explanation of the origin of the term "Quebec." Only Heidelberg in Germany, Sterling and Edinburgh in Scotland, and Ehrenbreitstein on the Rhine, observes a writer, can contend with Quebec for grandeur of situation and noble beauty. Even these grand historic sites can hardly with justice be compared to the "Canadian Gibraltar." This, indeed, is affirmed, with remarkable unanimity, by every visitor to the antique City. The novelist, Charles Dickens, thus speaks of the picturesque beauty and historic interest of Quebec:—"The impression

left upon the visitor, by this Gibraltar of America,—its giddy height, its Citadel, suspended as it were in mid air, its picturesque steep streets and frowning gateways, and the splendid view which bursts upon the eye at every turn, is at once unique and lasting. It is a place not to be forgotten or mixed up in the mind with other places, or altered for a moment in the crowd of scenes which a traveller can recall. Apart from the realities of this most picturesque city, there are associations that would make a desert rich in interest. The dangerous precipices along which Wolfe and his brave companions climbed to glory; the Plains of Abraham, where he received his mortal wound; the fortress so chivalrously defended by Montcalm, and his soldier-grave, dug for him while yet alive by the bursting of a shell, are not least among them."

J. M. LeMoine, the historian, whose works have done more than any other to perpetuate the memory of the picturesque old city, thus speaks in an address of welcome, to the American Association for the Promotion of Science, on a recent visit to Quebec:—

"The annals of this vast dependency of Britain, which we are proud to call our country, vaster even in extent than the territory of your prosperous republic, are divided into two distinct parts:

The first century and a half—1608 to 1759—represents the French domination.

Though totally alien in its aims and aspirations from the succeeding portion, it has nevertheless for Quebec an especial charm, most endearing memories. It was the fruitful era of early discovery, missionary zeal and heroism, wealthy fur trading companies,—shall we call them monopolies? incessant wars with the ferocious aborigines and sanguinary raids into the adjoining British provinces. When the colony expanded, an enlarged colonial outfit required more powerful machinery, more direct intervention of the French monarch: a Royal Government in 1663,—to save and consolidate the cumbersome system based on the Seigniorial Tenure in land; a mild form of feudalism implanted, at Quebec, by Richelieu. It would take me far beyond the limits I have prescribed to myself, were I to unravel the tangled web of early colonial rule or misrule, which until the conquest by Britain, in 1759, flourished, under the lily banner of the Bourbons, on yonder sublime cliff. Let us revert then, to that haunted dreamland of the past; let us glance at a period anterior to the foundation of Jamestown, in 1607, even much anterior to the foundation of St. Augustine, in Florida.

On the north bank of the River St. Charles, about a mile from its entrance, Jacques Cartier wintered in 1535. What a difference in the tonnage of the arrivals from sea, in September, 1535; the "Grande Hermine," 120 tons; the "Petite Hermine," 60 tons; the "Emerillon," 40 tons, and, in August 1860, Captain Vine Hall's leviathan, the "Great Eastern," of 22,500 tons!

What terror the shipping news that morning of September, 1535, must have caused to swarthy Donnacona, the chieftain of the Indian (Iroquois or Huron?) town of Stadacona! the first wave of foreign invasion had surged round the Indian wigwams which lined the northern declivity of the plateau on which Quebec now stands (between Hope Gate and the Côteau Ste. Geneviève)! Of course you are aware this was not Cartier's first visit to the land of the north; his keel had, in 1534, furrowed the banks of Newfoundland and its eternal fogs; in 1541-2, he had wintered a few miles higher than we now are—at Cap Rouge—west of Quebec. Then there occurs in our annals of European settlement, a gap of more than half a century. No trace, nor descendants on Canadian soil, of Jacques Cartier's adventurous comrades. The wheel of time revolves; on a summer day, (3rd July, 1608), the venerated founder of Quebec—Samuel de Champlain—equally famous as an explorer, a discoverer, a geographer, a dauntless leader, and what to us, I think, immeasurably superior, a God-fearing, Christian Gentleman—with his hardy little Band of Norman artificers, soldiers and farmers, amidst the oak and maple groves of the lower town, laid the corner stone of the "Abitation" or residence, so pleasantly, so graphically described by your illustrious countrymen, Parkman and Howells.

Ladies and gentlemen, mine must be a brief discourse; if, instead of pointing out to you the historical spots, now brought under your notice in the course of our excursion, it were my lot to address, as a Canadian annalist, such an appreciative audience as I see here, what glowing pictures of soldier-like daring, of Christian endurance, of heroic self-sacrifice, could be summoned from the pregnant pages of Champlain's journal and from that quaint repository of Canadian lore the Relations of the Jesuits? you would, or I am much mistaken, be deeply moved with the story of the trials, sufferings, and unrequited devotion to country, of the denizens of this old rock; your heart would warm towards that picturesque promontory sometimes, seemingly dear to sunny old France. One would be tempted occasionally to forgive the cruel desertion of her offspring in its hour of supreme trial.

From the womb of a distant past, would come forth a tale of deadly, though not hopeless struggles with savage or civilized foes, a tale harrowing, not however devoid of useful lessons. The narrative would become darker, more dreary, when to the cruelty of Indian foemen would be added, as oft was the case, the horrors of a famine, or the pitiless severity of a northern winter. A transient gleam of sunshine would light up the canvass when perchance, the genius of a Talon, the wisdom of a Colbert, or the martial spirit of a Frontenac succeeded in awakening a faint Canadian echo on the banks of the Seine. In those winding, narrow, uneven streets, the forest-avenues of de Montmagny and de Tracy, which now resound to no other sounds but the din of toil and traffic, you would meet a martial array of fearless, gay cavaliers, and plumed warriors, hurrying to the city battlements to repel the maraudering savage, or the foe from old or New England, equally objects of dread. From the very deck of this steamer, with the wand of the historian you could conjure the thrilling spectacle of powerful fleets, in 1629, in 1690, and in 1759, anchored at the very spot which we now cross, belching forth shot and shell on the sturdy old fortress, or else, watch flotillas of birch bark canoes laden with lithe, tattooed, painted warriors landing on that ere beach, bearing peace offerings to great Ononthio. Varied, indeed, would be the panorama which history would unroll. Finally, you might cast a glance on that crushing 13th of September, 1759, which closed the pageant of French rule on our shores, when all the patriotism of the yoemanry lead by the Canadian gentilshommes—the de Longueuil, de Vaudreuil, de Beaujeu, de St. Ours, de la Naudière, etc., was powerless against the rapacity and profligacy of Bigot, and his fellow plunderers and parasites . . .

These were truly the dark days of the colony under French rule; a glimpse of the doings in those times suffices to explain why French Canada, deserted by France, betrayed by some of her own sons, accepted so readily, as a fait accompli, the new regime; why, having once sworn fealty to the new banner implanted on our citadel by the genius of a Chatham, it closed its ear and steeled its heart even against the blandishments of the brave, generous Lafayette, held out in the name of that grand old patriot and father of your country, George Washington."

Eliot Warburton, the gifted author of "The Crescent and the Cross," has also left us a charming word-picture descriptive of the general features of Quebec on an autumn morning. "Take," he writes, "mountain and plain, sinuous river and broad, tranquil waters, stately ship and tiny boat, gentle hill and shady valley, bold headland and rich, fruitful fields, frowning battlement and cheerful villa, glittering dome and rural spire, flowery garden and sombre forest,—group them all into the choicest picture of ideal beauty your fancy can create, arch it over with a cloudless sky, light it up with a radiant sun, and, lest the sheen be too dazzling, hang a veil of lighted haze over all, to soften the lines and perfect the repose,—you will then have seen Quebec on this September morning." Not less delightful is the picture limned for us by Mr. Hawkins, the early historian of the fair city, and in his day one of its most impassioned admirers. The sketch, like that of Mr. Warburton, comprehends whole beautiful panorama. "The scenic beauty of Quebec," Mr. Hawkins observes, "has been the theme of general eulogy. The majestic appearance of Cape Diamond and the fortifications; the cupolas and minarets, like those of an Eastern city, blazing and sparkling in the sun; the loveliness of the panorama; the noble basin, like a sheet of pure silver, in which might ride with safety a hundred sail of the line; the graceful meandering of the River St. Charles; the numerous village spires on either side of the St. Lawrence; the fertile fields, dotted with innumerable cottages, the abodes of a rich and moral peasantry; the distant Falls of Montmorenci; the park-like scenery of Point Lévis; the beauteous Isle of Orleans; and, more distant still, the frowning Cape Tourmente, and the lofty range of purple mountains of the most picturesque forms which bound the prospect, unite to form a coup d'œil, which, without exaggeration, is scarcely to be surpassed in any part of the world."

Many of the more notable descriptions of Quebec, naturally enough, deal with its historic aspects, and chiefly with those curious phases of the city that recall a bye-gone age. Mr. Goldwin Smith refers to it as a surviving offset of the France of the Bourbons, cut off by conquest from the mother country and her revolutions. "Its character has been perpetuated by isolation, like the form of an antidiluvian animal preserved in Siberian ice." "Quebec and Montreal," the same writer remarks, "are the only historic cities of the Dominion, and Quebec alone retains its historic aspect. Even in Quebec there are in the way of buildings but scanty remnants of the Bourbon days. But the Citadel the prize of battle between the races, the key and throne of empire, still crowds the rock which stands a majestic warder at the portal of the Upper St. Lawrence; and the city with its narrow, steep and crooked streets, crouching under its guardian fortress, recalls an age of military force and fear in contrast to the cities of the New World, with their broad and straight streets spreading out freely in the security of industrial peace." The late Henry Ward Beecher has also written interestingly of the place, as a relic of the mediæval era, untouched by the eddying rush of modern progress. "Curious old Quebec!" he writes, "of all the cities of the continent of America the most quaint! It is a peak thickly populated! A gigantic rock, escarped, echeloned, and, at the same time, smoothed off to hold firmly on its summit the houses and castles, although, according to the ordinary laws of matter, they ought to fall off; like a burden placed on a camel's back without a fastening. Yet the houses and castles hold there as if they were nailed down. At the foot of the rock some feet of land have been reclaimed from the river, and that is for the streets of the Lower Town. Quebec is a dried shred of the

Middle Ages, hung high up near the North Pole, far from the beaten tracks of the European tourists—a curiosity without parallel on this side of the ocean. We traversed each street as we would have turned the leaves of a book of engravings, containing a new painting on each page. * * * The

locality ought to be scrupulously preserved antique. Let modern progress be carried elsewhere! When Quebec has taken the pains to go and perch herself away up near Hudson's Bay, it would be cruel and unfitting to dare to harass her with new ideas, and to speak of doing away with the narrow and tortuous streets that charm all travellers, in order to seek conformity with the fantastic ideas of comfort in vogue in the nineteenth century."

Nor have Canadian writers failed to pay at this seat of ancient dominion the homage which it extorts from visitors from other lands. Very eloquent have been the tributes paid by many of them, for few have approached the grand old storied rock without emotion, or been insensible to the stirring influences incited by its position and history. Here is an apostrophe from the graceful pen of the lady who writes under the familiar nom de plume of "Fidelis": "Quebec—the spot where the most refined civilization of the Old World first touched the barbaric wildness of the New—is also the spot where the largest share of the picturesque and romantic element has gathered round the outlines

of a grand though rugged nature. It would seem as if those early heroes, the flower of France's chivalry, who conquered a new country from a savage climate and a savage race, had impressed the features of their nationality on this rock fortress forever. May Quebec always retain its French idiosyncracy! The shades of its brave founders claim this as their right. From Champlain and Laval down to De Lévis and Montcalm, they deserve this monument to their efforts to build up and preserve a New France in this Western world; and Wolfe for one would not have grudged that the memory of his gallant foe should here be closely entwined with his own. All who know the value of the mingling of divers elements in enriching national life, will rejoice in the preservation among us of a distinctly French element, blending harmoniously in our Canadian nationality. 'Saxon and Celt and Norman are we;' and we may well be proud of having within our borders a 'New France' as well as a 'Greater Britain.'"

"Imagination," Fidelis continues, "could hardly have devised a nobler portal to the Dominion than the mile-wide strait, on one side of which rise the green heights of Lévis, and on the other the bold, abrupt outlines of Cape Diamond. To the traveller from the Old World who first drops anchor under those dark rocks and frowning ramparts, the coup d'œil must present an impressive frontispiece to the unread volume. * * * Looking at Quebec first from the opposite heights of Lévis, and then passing slowly across from shore to shore, the striking features of the city and its surroundings come gradually into view, in a manner doubly enchanting if it happens to be a soft, misty summer morning. At first, the dim, huge mass of the rock and Citadel—seemingly one grand fortification—absorbs the attention. Then the details come out, one after another. The firm lines of rampart and bastion, the shelving outlines of the rock, Dufferin Terrace with its light pavilions, the slope of Mountain Hill, the Grand Battery, the conspicuous pile of Laval University, the dark serried mass of houses clustering along the foot of the rock, and rising gradually up the gentler incline into which these fall away, the busy quays, the large passenger boats steaming in and out from their wharves, all impress the stranger with the most distinctive aspects of Quebec before he lands."

But we must conclude these extracts from writers who treat chiefly of scenic Quebec. What has been left unsaid will, no doubt, be readily supplied—perhaps even what has been said will be not less delightfully substituted—by the impressions of the individual visitor. Yet, however fervent may be the enthusiasm of those who come to pay homage at the shrine of the matchless city, how short of the glory of the reality will be the conception formed in the mind of even the most ardent onlooker. But besides the picturesque beauty, how full of memories is the quaint old place! Discovered by Cartier three hundred and fifty years ago, founded by Champlain three-quarters of a century later, the place still preserves the traditions and maintains much of the civil and religious character of that early time. The fur trade, it is true, has disappeared, and with it the Indian trapper and woodsman; but the French race remains and flourishes, and with it the Mother Church and the ecclesiastical system which founded and reared the Gallic colony. Nor has the "great red rock," though shorn of its trees and their many-tinted foliage, lost much of its old-time character. Since the days of Cartier and Donnacona, it has taken on a military aspect, and from its frowning fortifications Frontenac defied and Montcalm succumbed to an enemy; but its scenic aspects are still grandly the same. Enduring also is much of the zealous ecclesiastical life for which the theocratic city has been noted. Though time and the elements have wrought their ravages in the monuments of the Ancien Régime, in which Quebec abounds, not a few of the old landmarks remain which are associated with the adventurous years of the seventeenth century.

Those that have passed away have left their romantic history, while the buildings by which they have been replaced speak ever impressively of their early associations. The local antiquary has here a peculiarly rich field for his research. Those at all familiar with the history of the place will turn with special interest to those relics of a by-gone time. One, and, perhaps, the chief of these, is the church called Notre-Dame des Victoires, built on the site of Champlain's Abitation de Québec, which stands on the marketplace of the Lower Town. Another is the Basilica, formerly known as the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. This church, which was consecrated by Bishop Laval in 1666, was destroyed by Wolfe's batteries at the Conquest, but rebuilt thereafter. Other relics there are that date from the period of the English occupation, which are full of the traditions of that stirring era. Not a few of these, such as the ancient gates of the city, have yielded to the necessities of a later civilization, and been replaced by modern structures, happily preserving, however, much of their unique military character. To these the eye of the visitor will be drawn as well as to other places of noteworthy interest, such as the Seminary of Quebec, Laval University, the Ursuline Convent, and the Hôtel-Dieu Convent and Hospital. These will recall to the historical student, not only the France of the Bourbons, but a Canada which was once her cherished military and clerical outpost. But perhaps the chief attraction, for at least the English-speaking tourist, will be the scenes famous in the annals of British prowess, the Plains of Abraham, Wolfe's Cove, the Citadel and ramparts, with the magnificent panorama spread out to view from the King's Bastion. There is hardly in the world a grander outlook than that from the King's Bastion, or from the terrace below, the favorite promenade of the citizens. From either point may be seen the wharves, the shipping and the gleaming river; the fortified bluffs of Pointe Lévis opposite; and, off in the distance, the Laurentian peaks, with, nearer at hand, the Isle of Orleans, the mouth of St. Charles, and the Beauport shore.

Nor is the view less memorable from the noble river that laves the feet of the fair city and sweeps onward to the sea. As seen from the deck of the outgoing ocean steamer, or from the Pointe Lévis ferry, the retrospect to the Citadel-rock and the high-perched city, is singularly impressive. With so magnificent a theatre for action, what wonder that brave deeds were done before the walls of Quebec, deeds that have immortalized their actors and consecrated the stage on which they were wrought.

Quebec occupies a position which seems to have been naturally created for the site of a great city. Even the Indians appreciated its advantages when they established here the village of Stadacona with the instinct of a dawning civilization. But it is to the commanding genius of Samuel de Champlain that the city owes its origin. This great man, whose character has been compared with that of Julius Cæsar, quickly saw the greater advantage of settlement in Canada to colonization in Acadia, and wisely

concluded that those who commanded the St. Lawrence would hold the key of Canada. In the year 1608 he laid the foundations of the fortress city by building the "Abitation de Québec," of which he has left us a sketch. It was situated in the present Lower Town on the river bank, in the corner where Notre-Dame street meets Sous le Fort street. After the promulgation of the Edict of Nantes, when France enjoyed a respite from religious wars and persecutions, Henry IV. turned his attention to commerce and colonization. It was in pursuance of this policy that Champlain was sent to Canada.

Before Henry IV.'s day, the chief aim of exploration in the New World was the search, if happily it might be found, of a western waterway to the Orient. Failing in this, the results of Cartier's visits to Stadacona and to the Indian village higher up the mighty river, which he named the St. Lawrence, were disappointing to the court of France. Nor was Roberval's expedition practically more fruitful than that of his pilot-general. Both enterprises were regarded as failures, and French adventure cooled its exploratory ardour and ceased for a time to contend in New France against a savage people and an arctic winter. From the period of Cartier's and Roberval's expeditions, fully fifty years elapsed before France renewed her efforts to colonize the New World. Her

success, measured by that of her British rival, was small. Champlain, the first of her real colonizers in New France, had many of the elements of greatness in his character and policy, but at the outset he committed an unfortunate error in arousing the enmity of the warlike Iroquois who became the scourge of the infant colon. After laying at Quebec the foundation of French dominion in the New World, Champlain set forth to explore the country. He unfortunately consented to ally himself with the Hurons and to assist them in repelling the raids of the Iroquois confederacy. This policy subjected the French colony to harrassing Indian attacks for over a hundred years, and led to the final extirpation of its Huron allies, and to the martyrdom of the Jesuit missionaries among the dusky braves. However, the little colony grew apace and Quebec bade fair to become an important outpost of the French Crown on the American continent. Unfortunately for the colony, its seemingly bright prospects were marred by the outbreak of a war between France and Britain, and the despatch of an English expedition, under Sir David Kirke, to capture Quebec and hold the country. Kirke appeared twice before Quebec, and, on the second occasion (A.D. 1629), compelled Champlain to surrender that stronghold, and with it the whole territory of New France.

The English held the country for three years, when, to the joy of Champlain, it was restored to France by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Becoming master again of the country, Champlain redoubled his efforts to establish French dominion in the New World on a stable basis, to pacify the dreaded Iroquois, and to extend among the friendly Indian tribes the religion of the Cross. But, on Christmas Day, 1635, this great work was interrupted by the death of Champlain; and the colony mourned its founder and noblest administrator. The Hundred Associates, a company of political favorites who enjoyed a monopoly in the fur trade, made no serious effort to people the colony, and the labors of Champlain were almost nullified, until the company's charter was cancelled, and the irrule of the fur traders gave place to an administration by the Crown. The deplorable condition of the colony had at last won sympathy in France, and its

affairs were now placed in the hands of a Supreme Council, appointed by the king, with a number of officers who were sent out to look after its temporal and spiritual welfare. Under this "royal government" the colony revived and Quebec entered upon a proud period of heroic action. With the coming of Frontenac, as governor, French adventure again plumed its wing, and led by La Salle, extended the domain of France westward to the Mississippi and southward to the Gulf of Mexico. But brief was the respite from war and Indian turbulence. While Frontenac was at the head of the administration, the Indian enemies of France were kept in subjection and had a wholesome fear of his name. But dissension broke out in the colony, caused by a conflict of authority, and Frontenac was for a time recalled to France. He was succeeded first by M. de la Barre, and afterwards by the Marquis de Denonville, the latter of whom, by an act of perfidy, coupled with the invasion of the Seneca country, roused the Iroquois once more to invade New France. The whole colony was now in the greatest jeopardy, and news of this reaching the mother country, Count Frontenac was forthwith despatched to Quebec and reinstated in the governorship. With Frontenac's return, New France once more took heart, for his active mind and imperious will infused new life and vigor into the administration. Unhappily for the country, his first act was to punish the English on the seaboard for inciting the Iroquois to make their fiendish attack on the colony. This he did by fitting out three separate expeditions to harry the border settlements in New York, Maine

and New Hampshire. The assault on the English settlements brought its sad tale of reprisal, for the governments of New York and Massachusetts organized a combined military and naval expedition for the invasion of Canada. Owing to the failure of the Indian allies of the English Colonists to join the expedition, the military section of the invading force accomplished nothing, but the naval contingent, under Sir William Phips, wrested Port Royal from the French, and then, sailing up the St. Lawrence, demanded the surrender of Quebec. The fleet appeared before that stronghold in October, 1690, but the haughty Frontenac was prepared for its coming. Phips, elated at his success at Port Royal, with no little bravado called upon the Governor to surrender. Frontenac's answer was to open fire on the invader's ships and to drive off the assailants.

Soon after the opening of the Seven Years' War, in Europe, the French and English were soon again contending for the prize of empire in the New World. Through two years' operations, the English, in North America, were without competent leadership, and success rested with the French arms. In the struggle the latter were greatly aided by the genius and experience of Louis Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, an officer who worthily represented the gallant race from which he sprang. Montcalm had the invincible spirit of a soldier, but unfortunately for his country, he was ill-supported by Old France, and his difficulties were increased by the maladministration of affairs in the colony. Despite these drawbacks, he was for some years the means of protracting the gallant struggle in America, and of bringing many disasters on the English arms. But a turn came in the tide of fortune when Pitt, "the great English Commoner," assumed the direction of the war and planned the overthrow of French power in America. In 1758, the French met the first of a series of reverses, in the fall of Louisbourg, at which Wolfe, the most interesting figure in the military history of the time, greatly distinguished himself. Then followed, in succession, the surrender or abandonment of Fort du Quesne, in the Ohio Valley, Frontenac (Kingston) on Lake

Ontario, Crown Point and Ticonderoga, on Lake Champlain, and finally Niagara. With these disasters the French were swept from the Lakes, and Destiny closed in upon Montcalm in the last act of the drama—the spirited siege of Quebec. Very menacing to the French must have been the combined land and sea force Wolfe brought with him to attempt the capture of the all-but-impregnable city. With Wolfe, now General of the Forces of the St. Lawrence, came his brigadiers—Monckton, Townshend, and Murray; and in command of the fleet were Admirals Saunders and Holmes. They appeared before Quebec at the end of June, 1759. Disembarking his army of 7,000 or 8,000 men on the Isle of Orleans, but presently

occupying also Pointe Lévis and the eastern bank of the Montmorenci River, Wolfe proceeded to view the bristling line of French defences along the Beauport shore, and the towering red-rock fortress, the possession of which was to change the destiny of the continent. The young General was appalled at the formidable task he had undertaken. To capture Quebec seemed to him hopeless, and the consciousness of this, after many long weeks passed in various assaults, which ended only in discomfiture, helped to bring on a fever, which long prostrated him and weakened his already enfeebled frame. But Wolfe's heroic spirit remained undaunted. The French vigorously maintained the defensive, trusting to the seemingly unassailable citadel, the fire-belching batteries which surrounded it, and the many fortified camps disposed along the north shore of the river from the St. Charles to the Montmorenci. There was, however, no lack of courage in the assailants. For months the siege was maintained, amid almost incessant cannonading from the English warships. Calamitous was the effect of the siege upon the doomed city. "The buildings in the Lower Town," says a native writer, "were soon reduced to ruins. Fires in the Upper Town were of well nigh daily occurrence. Sometimes several buildings were seen blazing at once, presenting the appearance of a vast conflagration. On the 17th of July, and again on the 19th, large numbers of buildings were set on fire by the shot, and continued a long time burning, as if the whole city had become

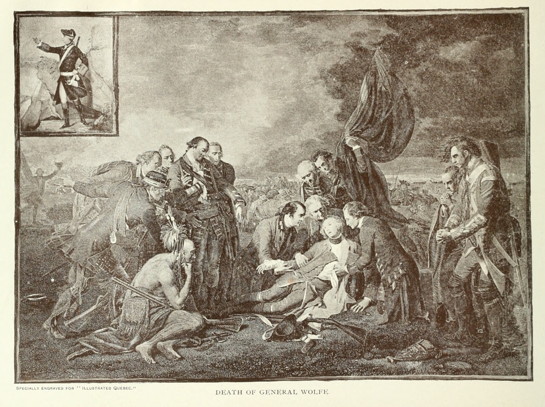

a prey to the flames. Before the siege ended, more than five hundred buildings were destroyed, including private and public edifices, the cathedral and other places of worship. Of the inhabitants, the non-combattants, who had not retired before, fled for refuge into the country, many were killed and wounded, struck by cannon balls, some in the streets and thoroughfares, others within the walls of public places of resort and private dwellings. By the middle of August the city was virtually destroyed—most of its resident population having vanished, its principal habitations and edifices in ruins, and even the pieces of ordinance on the ramparts for the most part rendered useless." Another month passed, a month of fruitless effort on the part of the assailants. Wolfe became increasingly sick and discouraged. Recovering his spirits, however, as he saw something must be done before the approach of winter, he daringly grappled with a project which led him to victory and to a victor's grave. This project was to scale the almost inaccessible cliffs of Sillery and gain the Plains of Abraham, in rear of the city, and there to bring Montcalm to battle. Orders were issued to have the fleet in readiness to make a feigned attack on the Beauport shore, while the bulk of the army was to move up the river, drop down again over night, climb the precipice and form on the heights to attack Quebec from the rear. The night of the 12th September saw this daring scheme put into execution.

The dawn saw the English army massed in position on the Heights, and the surprised French army, under their brave leader, Montcalm, gallantly marched, from Beauport, to attack the invaders. Brief was the struggle that followed. The English reserved their fire until the enemy was within forty paces of them, when they poured a deadly rain of bullets on the advancing French and Canadians, and the Scottish regiments charged with bayonet and broad sword. The native militia broke and fled, and the veterans of France, after stubbornly contesting the position, were compelled to fall back and seek refuge in the Citadel. The commanders of both sides fell mortally wounded—Wolfe dying on the field, and Montcalm breathing his last on the morrow within the walls of Quebec. Three days afterwards Quebec surrendered, and the flag of Britain supplanted the emblem of France. In the ensuing winter the city was held by an English garrison, under General Murray, and in the following spring it narrowly escaped capture by De Lévis, at the head of seven thousand men who had come from Montreal to attack it. The timely arrival of a British fleet saved the now British stronghold, while Montreal was in turn invested, and that post and all Canada surrendered to the British Crown. Three years later the Peace of Paris confirmed the cession of the country to Britain and closed the dominion of France in Canada.

In the Revolutionary War the stability of England's conquest of Quebec was threatened by American invasions under Arnold and Montgomery. In the war, the Americans called upon the French-Canadians to join them in their revolt, and though it is true that a small band responded, the majority remained stanch in their allegiance to Britain and resisted the blandishments of treason. This passive attitude of the French Province, when it was expected to rally to the standard of revolt, so angered the Americans that they determined to invade Canada and wrest it from the British Crown. In 1755 two expeditions were fitted out for this purpose, one of which seized the forts on Lake Champlain, the gateway of Canada, and, thinking that the Canadians would offer no resistance, proceeded to invest Montreal. Another expedition advanced upon Quebec. Montreal being indifferently garrisoned, surrendered to the Americans, but the attack on Quebec failed, after some weeks' siege. The American general, Montgomery, who had formerly fought for Britain in Canada, was killed in storming the Citadel on the 31st of December, and the discomfited invading force was in the following spring driven from the country.

Some writers have confounded Major General Richard Montgomery, who was slain, as just stated, with Captain Alexander Montgomery, of Kennedy's or the 43rd Regiment, who also served under Wolfe at the conquest of Quebec. The error has been accounted for by a writer in the Magazine of American History, as follows: Some years since, the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, published an extract

from a manuscript journal relating to the operations before Quebec, in 1759, kept by Colonel Malcolm Frazer, then Lieutenant of the 78th (Frazer's Highlanders), serving in that campaign. Under date of August 23rd, 1759, it is recorded in the journal: "We were reinforced by a party of about 140 Infantry, and a company of Rangers, under the command of Captain Montgomery, of Kennedy's or 43rd Regiment, who likewise took command of our detachment, and we all marched to attack the village to the west of St. Joachim, which was occupied by a party of the enemy to the number of about 200, as we supposed, Canadians and Indians. There were several of the enemy killed and wounded, and a few prisoners taken, all of whom the barbarous Captain Montgomery, who commanded us, ordered to be butchered in the most inhuman manner." The editor of the publication, not content to let the journal speak for itself, appended a note stating that the Captain Montgomery here spoken of was "the Leader of the Forlorn Hope who fell at Près-de-Ville, 31st December, 1775," thus falling into the grave error of confounding Lieutenant Richard Montgomery, of the 17th Regiment, with Captain Alexander Montgomery, of the 43rd. Doubtless, this unfortunate note, published under the sanction of an Historical Society, on the very spot where these events transpired, has done much to perpetuate a mistake now almost crystalized into history. Richard Montgomery rose to the rank of Captain in the British army and sold out his commission, April 6th, 1772, after having served with distinction throughout the campaign from 1758 to the final surrender of the French at Montreal, in 1760.

We have set before the visitor to Quebec the special features of the city as seen from the river, and the general aspects of the incomparable scene to be witnessed from the frowning Citadel or from Dufferin Terrace, the magnificent promenade which perpetuates the name of one of Canada's most popular governors. Now let us land and view in some detail, however brief, the more striking monuments—military, ecclesiastical and civil—of this matchless Mecca of the tourist. As one puts foot on the historic soil, the "metropolis of a once forest State," the ancient and foreign aspect of the city is borne in upon the mind. The quaint, picturesque figures of

the habitants, their alien speech, their primitive vehicles of locomotion, their antique French houses huddled together and poised high up on the edge of the cliff, the enwalled citadel and menacing fortifications, the narrow, crooked streets and winding steep ascent to the Upper Town, recall some old world capital, a survival of mediæval times. But, besides these features of interest to the visitor, there are others which appeal with irresistible force to the mind of the historical student, for Quebec is the one city on the continent which preserves, almost intact, the romantic characteristics of its early origin with the feudal and monastic aspects of an old-time enleaguered town. The roots of the city are intertwined with those which form the beginnings of Canada, and to which we trace the origin of her people. In this respect Quebec fitly stands at the portals of the country, whose far-separated shores are laved by the waters of three oceans. What an air of distinction too there is about the site! The city is perched on a high bluff which terminates a lengthened stretch of elevated tableland.

Its highest point is the citadel-crowned Cape Diamond, almost 350 feet above the St. Lawrence. Nature no less than Art has divided the city into an Upper Town and Lower Town, the latter, on its eastern front, being wedged between the base of the cliffs and the river. Built on a promontory, the city has room for expansion only to the southward, across the historic Plains of Abraham, its other flanks being girt by the St. Lawrence on the east and the river and valley of the St. Charles on the west. A wide range of wharves juts out from its water front and furnishes ample accommodation, for its large shipping trade. The Lower Town is given up chiefly to commerce but this has now intruded into the Upper Town, where are the better class of residences. The lumber and ship building trade of the city have diminished, but on the other hand many and enterprising factories have been established, which for the most part have done well; but the city's commercial importance is not now what it has been. Montreal with its more progressive British element, has of late encroached seriously on its trade.

The chief interest of Quebec, however, lies not in its commerce. Like some cities of the Old World—such as Edinburgh—its attractions are those that appeal to the historical and imaginative sense, and to a wealthy and leisured class, whose tastes are those of their order. Not a stone's throw from the landing-place, just under Dufferin Terrace, still stands the Church of Notre-Dame des Victoires, erected in 1690 to commemorate the defeat of Sir William Phips and his New England Naval force. Hard by also is the site, now occupied

by a market, of Champlain's Abitation de Quebec, with its moat and walled enclosure, within which the little French colony, including trader, soldier and black robe, shielded itself from the pitiless assaults of the ever-prowling Iroquois. Just overhead once frowned the old fortress of Quebec, whence "France in the New World" was ruled for the space of two centuries. Within and adjoining the fortress, from the earliest years, sprang up those numerous seminaries, convents and hospitals, which Quebec owed to the zeal and devotion of successive governors, bishops, and great missionaries of the Church. As one views those old sites, what memories gather round the place, and how apt is the imagination to repeople the scene! Chief among the figures which the memory summons must be those of the heroic Jesuits, the spiritual fathers of the colony. With the ecclesiastical atmosphere still permeating the city, it is easy even now to recall them. There are the gorgeously arrayed officers of the army, and here the great ladies of the mimic court, while in the back ground is a confused rabble of musketeers, pikemen, traders, voyageurs and workmen. Nor would the picture be complete without the stalwart Indian, "wrapped to the throat in embroidered moose-hides," jostled, it may be, by a tipsy sailor on furlough from some late arrival in the harbour. But the Quebec of to-day

recalls more than these early memories. We come down the years, and the pageant of shadows passes before the mind of the student-onlooker. Governors, intendants and bishops are figures in the flitting procession. We cite the names of but a few of the more notable personages. The devout Champlain, in the course of time, gives place to the militant Frontenac, while Frontenac in turn gives place to Gallissonière and the two Vaudreuils. In the office of Intendant, Talon is followed by Beauharnois and Bigot; in the Church, Laval, Quebec's first bishop, is succeeded by St. Vallier and De Morny. Each played his part in the drama of the time, Quebec meanwhile owning the sway of the two Louis—the one who made and the other who unmade the colony and its capital. The contemporary period in English history is that covered by six sovereigns of

Britain, from Charles II. to George II. Then comes the era of the Conquest, and how rich is it in the figures that enoble the time! Two illustrious personages stand out distinctively and with pathetic interest from the canvas—the figures of Wolfe and Montcalm. Besides these immortal heroes, there were on the French side De Lévis, De Bougainville, De Ramezay, Senezergues, Bourlamarque and St. Ours; on the British side, Saunders and Holmes of the fleet, with Monckton, Townshend, Murray, Carlton and Amherst of the army. A little later, in the heroic annals of the city, appear Arnold and Montgomery, the two hapless leaders of the American army of invasion. How the story intwines itself, through two fateful centuries, round these several names! Nor does the human interest in these actors on the stage of the Ancient Capital end with the Conquest. Though Quebec passes now under the peaceful rule of Britain, interest does not altogether cease in the rulers of the colony. The city has known many of these rulers and owes much to not a few of them, from the era of Dorchester and Haldimand to that of Dufferin, Lorne, Lansdowne and Stanley. Since Confederation, Quebec has also had its successive local governors, who have kept alive the traditions of the place and made it the scene of occasional State pageantry and an old-time hospitality.

Quebec is still a fortress; and, though not now garrisoned by the soldiery of Britain, from the bastions of the Citadel there still floats the red cross banner, the symbol of her power. Perhaps the most

impressive view of what has been termed the "Gibraltar of America" is that from Dufferin Terrace, the magnificent promenade, which is the pride of every Quebecer. From this commanding position, half way up the slope of the historic rock, a fine view is had of the Citadel and of the fortifications which enwall it and its forty acres of parade-ground, bastions and entrenchments. How the British heart swells at sight of those frowning walls, which even in these days of destructive military armaments could still give a good account of themselves! Nor would the response be less effective since they are now manned by loyal Canadian youth. Approached from almost any quarter of the city, the fortress of Quebec inspires the visitor with awe. "The fortifications," says an American writer, "are omnipresent. No matter from what point you look towards the ancient city, for eight or ten miles away, they are there still with their geometry against the sky." Nor does a nearer view disenchant one. Entrance to the fortress is gained by what is called the Chain Gate, which gives access to the trenches, and by Dalhousie Gate, which ushers one into the heart of the Citadel. Passing across the parade-ground

and the officers' and men's quarters, we quickly mount the ramparts and gain the King's Bastion. Here the glorious spectacle, already referred to, bursts upon the delighted visitor, and long will he linger to take in the full beauty of the ever-changing scene. Hardly less fine is the outlook from other parapets and eminences within the grim fortress. On one side far and wide flows the noble river; on the other the eye follows, across the St. Charles Valley, the high rounded summits of the far-off Laurentides, the oldest range of mountains in the world. To the west, stretch out the historic Plains of Abraham; while in another direction rises the imposing front of Laval University, tapered off by the countless dwellings that cling to the sloping flanks of the great red rock. In the latter quarter also shoot up the numberless spires and steeples that crown the uptown section of the interesting city. There also may be distinguished Quebec's far-famed Basilica, flanked by the seminaries, convents, hospitals and the cluster of ecclesiastical institutions whose past makes rich the annals of the place. Nor does the least interest attach to the city's gates, even in their modern attire, which remind the visitor of the old military régime, and which happily form part of the reconstructed line of fortifications. A rich history clings to them, though only two of the five original gates are now preserved. These are St. Louis and St. John's gates, Kent Gate—a new gate—forms part of the Dufferin plans of city embellishments. It commemorates the sojourn in Quebec, of H. R. H. the Duke of Kent. The visitor will be grateful for the revival of these interesting heir-looms, though, historically, he will miss Hope Gate, Palace and Prescott gates, the quaint picket-flanked structures which marked the era of the British occupation of Quebec. Prescott Gate was sacrificed to the demands of commerce and to the thoroughfare which led up Mountain Hill from the Lower Town; and Hope Gate was likewise demolished at the call of the same ruthless traffic. With these fell also Palace Gate, a relic of the earlier occupation of the city, and once the portal to the palace of the French Intendants. Happily, however, as we have said, three of the more characteristic gates have been rebuilt, and in a style that does credit to the taste of the public-spirited viceroy who was instrumental in securing their restoration. These memorial structures not only form in themselves a series of interesting and picturesque arch-ways, but agreeably diversify the scene in the stroll round the ramparts, which should not be omitted by the visitor.

Ecclesiastical Quebec is hardly less attractive to the visitor than military Quebec, for in the churches, seminaries and convents of the city is embodied the religious life of a town still breathing the monastic spirit of the seventeenth century. Crowning the cliffs, attempted by Montgomery, stands the stately edifice of the Laval University, the chief seat of French culture in the Dominion. In its foundation may be traced the beginning of intellectual development in the New World. Laval is nobly equipped as a university, and possesses, in a high degree, both the staff and the practical appliances for modern culture. Its conspicuous position, no less than the scope of its imposing buildings, single it out as one of Quebec's worthiest sights. Nor are these all its attractions; for it is rich in art treasure, which vie with its historical associations in drawing visitors within its walls. Laval had its rise in the Seminary of Quebec, founded in 1663 by the princely prelate who was the first bishop of the See, and who endowed the institution with his vast wealth. Fire has, at various times, played havoc with this as with other of the city's interesting edifices. The present buildings are modern, as is the Seminary Chapel, which, when it fell a prey to the flames, lost most of the famous paintings which once were its glory. Modern, too, is the University Charter, for it dates back only to 1852, when it took the name of its distinguished early founder. Over half a dozen colleges and seminaries are affiliated with Laval, which maintains four faculties—those of Arts, Theology, Law and Medicine. It has a splendid library, museum, and art gallery, each of which will well repay inspection. From the dome of the central building a magnificent view of the St. Charles Valley and the River St. Lawrence may be had.

On the eastern side of the old Market Square stands the Basilica, or Roman Catholic Cathedral of Quebec. It is, perhaps, the most interesting object in the city, for it occupies the site of the ancient Church of Notre-Dame de la Recouvrance, erected in 1633 by Champlain, to commemorate the restoration of the colony by Britain. Within its walls were interred the remains of Laval, Frontenac, and others of Quebec's most notable historic figures. To the lover of art it has special attractions, for it possesses many rare and notable paintings, some of which were brought for safe-keeping to Quebec while France was passing through the horrors of the Revolution. Among these treasures will be found the Crucifixion ("the Christ of the Cathedral"), by Vandyke, the "Ecstacy of St. Paul," by Carlo Maratti, with other paintings of inestimable value. Not far from the Basilica is the Cardinal's Palace, the official residence of His Eminence the Cardinal-Archbishop of Quebec; and close by, also, is the site of the once famous Jesuits' College, recently demolished.

In Garden street is the far-famed Ursuline Convent, its beautiful gardens, some seven acres in extent, charmingly setting off the historic buildings they enclose. The convent, which dates from 1686, though founded fifty years earlier, owes its origin to the missionary zeal of Madame de la Peltrie and Marie de l'Incarnation—two remarkable women, whose religious devotion are the themes alike of native poets and historians. Bossuet calls Marie de l'Incarnation "the St. Theresa of the New World." The Chapel contains many very valuable paintings, the works of the most noted artists of the chief continental schools. But perhaps its chief attraction, above even the ecclesiastical relics enshrined here, is the skull of Montcalm, whose remains were interred within the precincts of the convent in a hollow said to have been made during the siege of the city by the bursting of a shell.

Another institution highly prized by Quebecers is the Hôtel-Dieu, founded in 1639 by a niece of Cardinal Richelieu. During the seventeenth century it played an important, sometimes a tragic, part in the religious life of the French colony. Attached to the convent and hospital is the chapel, which contains the bones of Lallemant and the skull of Jean de Brebeuf, the "Ajax of the Jesuit Missions." Students of Mr. Parkman's narratives, recounting the doings of the "Jesuits in North America," will be interested in seeing these martyr-relics. The hospital is situated on Palace street and the chapel on Charlevoix street. In the latter will be found many valuable paintings.

If the Parliament Buildings have lost their old historic site, on Mountain Hill, they have gained by the change. Spacious as well as imposing is the pile which has recently been erected for the Provincial Legislature on the Grande Allée, just outside St. Louis Gate. It includes not only the two Legislative Chambers, but the Departmental Offices, the whole forming a massive square, each front of which is 300 feet long and four stories in height. The style is that of the seventeenth century—French; the main entrance is handsome and striking and the interior ornate. There is an extensive and valuable library, rich in its store of documents preserved from the French régime.

Passing out from the Parliament Buildings, the visitor, if he is driving, will be disposed to proceed along the Grande Allée, past the Drill Shed and Armoury, and beyond the Martello Towers to the renowned Plains of Abraham. The classic ground is marked by a modest column, on which is inscribed the simple words, "Here Died Wolfe Victorious." On a spot so sacred as this, where fell the conqueror of Quebec, no more ambitious memorial is needed. Not only the Plains, but city and citadel are his monument. A short distance off, on the scarp overhanging the St. Lawrence, is the path by which the British troops scaled the cliffs on the night before the battle. At the foot of the cliff is Wolfe's Cove. Crossing over to the Ste. Foye Road, another memorial of the struggle for empire between the two races will be seen. It is the monument erected by the St. Jean-Baptiste Society of Quebec, "Aux braves de 1760," who fell in the engagement between De Lévis and Murray, when France sought to regain Quebec and undo the results of Wolfe's victory. Before returning to the city, either by the Grande Allée or by Ste. Foye Road, the visitor may take advantage of the proximity of Spencer Wood to call and pay his respects to His Honour the Lieutenant-Governor. The gubernatorial residence, it will be found, is a magnificent one, finely situated in eight acres of land, the drives and gardens of which are replete with beauty.

The famous Provincial Mansion commands a delightful view of Cape Diamond, the Citadel, the mighty St. Lawrence, and the Point Lévis shore. Near by the Lieutenant-Governor's residence is the picturesque home of Quebec's learned antiquary and historian—Mr. J. M. Lemoine, F. R. S. C. In the neighbourhood also are Mount Hermon and Belmont, the two most picturesque of the city cemeteries. Re-entering Quebec, the visitor must be left pretty much to his own devices. He will naturally seek the open spaces before pursuing his further quest of the interesting. The Esplanade, with its green lawns and delightful shade trees, will entice the lounger and give him new glimpses of the city's fortifications and new gates.

Here is the habitat of the Garrison Club, and in the vicinity are the barracks of the Royal School of Canadian Cavalry. A stroll along the ramparts between St. Louis and St. John's Gates will well repay the sight-seer. The other breathing spaces of the city proper are the Place d'Armes, a pretty little park lying between Dufferin Terrace and the Anglican Cathedral, and the Governor's Garden, which opens out from the Terrace, and is adorned by that most interesting of Quebec's memorials, the column erected to the illustrious memories of Montcalm and Wolfe. For four generations, now have vanquished and vanquisher lain silent in the grave, but their old-time chivalry links their names forever in Canadian annals and gilds with undimmed lustre one of the most thrilling episodes in the history of the two nations.

To the calèche-driver, that characteristic personage to be met with everywhere about the Ancient Capital, the visitor will be beholden, if not for much enlightenment, for the means, at least, of getting to and fro in old Quebec and its interesting environs. Our itinerary has been far too brief to exhaust the attractions of the place. Much else remains to be seen, even in the city proper; while the vicinity of Quebec abounds in places and objects of interest. The city's public buildings are not numerous, nor are many of them striking in their architectural features.

One or two of them, however, are not without interest. The Post Office, with its old French quatrain, which preserves the traditions of the feud between the Intendant Bigot and the merchant Phillibert, will draw the curious to Buade street, the scene of the Chien d'Or legend. The Anglican Cathedral, erected by the British Government at the opening of the century, will, in spite of its unpretentious appearance, attract the visitor, for it occupies the site of the old Recollet Monastery. It, moreover, preserves the memory of the first Anglican prelate of Quebec—Bishop Mountain—and holds the dust of Governor-General, the Duke of Richmond, who died in 1819 of hydrophobia. Nor will the visitor, if a Presbyterian, omit to visit the Morrin College, the divinity hall of his denomination. Here are the headquarters and the rich library of the Quebec Literary and Historical Society, one of the oldest and most useful of Canada's literary organizations. The society is noted for its important historical researches. Near by is St. Andrew's Church, the worshipping place of the Scottish Presbyterians. Chalmer's Church is another Presbyterian place of worship of note. The Methodist and Baptist denominations have also substantial churches in the ancient city. The Irish Roman Catholics have in St. Patrick's Parish Church an attractive sanctuary, while the French Catholics have on St. John street, without the gate, a sumptuous edifice in the St. Jean-Baptiste Church. On the same street is St. Matthews, an ornate structure, the property of the Anglican body. In the suburbs are two other Roman Catholic churches—St. Sauveur and St. Roch's. Of other institutions and public buildings in the Ancient Capital, little room is now left us to speak. The Custom House is a notable building, reached from St. Peter street, the centre of commerce, by way of Leadenhall street. Other public buildings hitherto unmentioned are the Academy of Music, the City Hall, the Court House, the Masonic Hall, and the Hall of the Y. M. C. A. Nor must the city's hotels be forgotten, the chief of which are the Florence, the Chateau Frontenac, St. Louis, and Russell House. The new Florence is of modern structure, under most excellent management and commands a magnificent view of the St. Charles Valley and the distant Laurentian chain of mountains.

Quebec is essentially a city of relics, architectural and antiquarian. No tourist will, of course, fail to have a look at the old "Break Neck Steps," or omit to saunter through the quaint Old World region of the city, known as "Sous le Cap." This locality has been sadly changed in appearance by the falling, a few years ago, of a portion of the cliff which overhung Champlain street. The huge mass of rock and earth fell without a moment's warning on the roofs of the houses below. Many lives were lost and much suffering, sorrow and loss of property entailed upon the unfortunate residents. As a matter of course, many of the antiquities of Quebec are well worthy of study. Not only in public repositaries, but in the homes of many of the old families of the city, are to be found numerous rare treasures and heirlooms, with many quaint old bits of furniture and miscellaneous bric-à-brac. Quite recently was discovered a small mahogany cabinet or cupboard, supposed to have belonged to Champlain, and in its art-workmanship certainly a manufacture of the founder's era. Another interesting relic, also recently picked up, was a combined toilet and writing case, of curious old English workmanship, said to have once been in the possession of General Wolfe. General Montgomery's sword, found near him when he fell, is deposited, for safe keeping, in the museum of the Literary and Historical Society, at Morrin College.

The almost world-wide repute of Quebec includes more than the city proper; it is shared, in some measure, by its historic environs. The scenery which is surpassingly fine, is also no inconsiderable factor. Among these interesting resorts is the site in ruins of the Chateau Bigot, the once proud manor house of the most profligate Intendant New France was ever cursed with. Beaumanoir, or as it is sometimes called, the Hermitage, lies beyond the picturesque hamlet of Charlesbourg, about eight miles east of the city. In the drive thither, a splendid view may be had of the great red rock and citadel, a view which no doubt often charmed the eye of the roystering Bigot and his graceless companions. Of his once luxurious summer chateau, all that remains are a fast crumbling wall and two gaunt gables.

The emblem of his faith is ever before the Canadian habitant: In these drives to the famous environs of Quebec are always to be met with, the Parish Church and the wayside cross, and frequently a venerable curé, in his black "soutane."

Beauport is passed on the way to Montmorenci. The long-drawn-out village is associated with the illustrious names of Wolfe and Montcalm, for the latter had once his abode here, while the place bore the brunt of Wolfe's siege artillery in the operations preceding the Conquest. Traces are here to be met with also of the mansions of representative families of the Old Régime. In another direction lies the Huron village of Lorette. It is prettily set upon a hill, about ten miles from the city, while at its base, flowing leisurely, along, is the St. Charles River. The beautiful Lorette Falls are in the immediate neighbourhood. Six miles from Lorette is Lake St. Charles, a notable resort of sportsmen. A drive of three miles by the

Grande Allée and the Cap Rouge Road brings the visitor to Sillery, where a Mission was founded in 1637 by the Chevalier who has given his name to the village. This grand seignior, history relates, was an officer of high rank at the Court of Marie de Médicis, but afterwards renounced the pomp and vanities of the world to undertake a mission to the Indians. Here the Church maintains the Convent of Jésus-Marie. A little beyond Sillery is Cap Rouge, near by which Jacques Cartier wintered with Roberval in 1541-2.

Beyond Montmorenci lie the pretty riverside parishes of L'Ange Gardien and Château Richer. Beyond these again, about twenty miles from Quebec, is the famous pilgrimage village, La Bonne Ste. Anne. The festival day of the saint is July 26th, and at that date the visitor, who is sceptical on the matter of cures will be able to witness the triumphs of faith in the miracles which are yearly reported at this great pilgrimage shrine of the Church. The local church is of ancient foundation, and is much venerated by the faithful. A modern edifice has of recent years been erected to accommodate the increasing bands of devout pilgrims who resort to the wonder-working shrine of Ste. Anne. Over the high altar in the church is a valuable painting by the famous Le Brun, entitled "Ste. Anne and the Virgin." It is said that over 80,000 pilgrims visit here annually. Let all who have the time make a visit to this world-renowned spot. More solemn scenes are not to be witnessed in any other part of the world.

The Chateau Frontenac is the name of the new hotel on the celebrated Dufferin Terrace; an esplanade unrivalled on the continent, and in some respects unequalled by any in Europe.

The site and the hotel are worthy of one another; the one crowning the mercantile portion of the city of Quebec and affording in three directions magnificent views of the lovely scenery of the St. Lawrence and the Valley of the St. Charles; and the hotel, complete in its appointments combines an architectural beauty and excellence of construction unsurpassed by any similar edifice in North America. The Chateau Frontenac is built of Scotch fire-brick and grey-stone, in the sixteenth century style of architecture. It cost about half a million dollars. Over the main entrance is a stone found in the walls of the old chateau when that was being torn down, and bears the date of 1647.

Nine miles north-west of Quebec, on a lofty wooded plateau, sloping in a southerly direction towards the River St. Charles, intersected by the highway and skirted by the new line of the Quebec and Lake St. John Railway, stands the Huron village of Lorette. It comprises forty to fifty cottages with a small church and occupies land set apart by Government, under regulations of the Indian Bureau, at Ottawa, as an Indian reserve, as such watched over by the Dominion Government with paternal solicitude.

It is governed by the customs of the antique Indian tribe located there for two centuries.

No white man is allowed to settle within the sacred precincts of the Huron reserve, composed: first, of the plateau of the village which the tribe occupy; second, of forty square acres, about a mile and a half to the north-west of the village; third, of the Rocmont settlement in the adjoining county of Portneuf, in the very heart of the Laurentides mountains,—ceded to the Hurons by Government, as a compensation for the seigniory of St. Gabriel, of which it took possession, and to which the Hurons set up a claim—as well as to lands in Sillery, west of Quebec.

The settlement is administered by a Council of Sachems; in case of any misunderstanding, an appeal lies to the Ottawa Bureau. Lands descend by right of inheritance: the Huron Council alone being authorized to issue location tickets, none are granted but to the Huron boys; strangers being excluded, though Hurons owning land beyond the village and paying taxes and tythes thereon, such as Tahourenche, Vincent and others, are admitted to vote in parliamentary elections.

The Hurons are divided into four families: that of the Deer; of the Tortoise: of the Bear; of the Wolf. The children take rank from the maternal side;—thus, the late great chief, Francois Xavier Picard (Tahourenche) was a Deer and his son, Paul, a Tortoise, because Madame Tahourenche, in her youth a handsome woman, was a Tortoise.

A census of the settlement taken in 1879, sets forth the population as composed of 336 souls, divided as follows: adult males, 94; adult females, 137; boys, 49; girls, 56; total, 143 males to 193 females. Bachelors must have been at a premium in the village.

According to the legend of the Great Serpent, of which more hereafter, the population is doomed to remain stationary. It certainly is not on the increase.

Each family has its chief or war captain: he is elected by choice. The four war captains choose two council chiefs; the six united select a grand chief, either from among themselves or from the honorary chiefs, should they think proper. The annals of this once powerful and warlike tribe, present tragical episodes. At one time it numbered 15,000 souls and inhabited chiefly the country bordering on lakes Huron and Simcoe. Sagard styles them "nobles" among savages, in contradiction to the Five Nations Confederacy—more democratic in their ways—also speaking the Huron language and known as the Five Nations: Mohawks, Oneydoes, Onondagas, Cayugas and Senecas, styled by the French, the Iroquois. The Mohawks at one time nearly overpowered by the Hurons, succeeded in the end by strategy and repeated massacres in dispersing their enemies, the Hurons, who never recovered their past prestige.

Their final overthrow dates back to the great Indian massacres of 1648 and 1649, at the Huron towns or missions on the shores of Lake Simcoe, St. Louis, St. Joseph, St. Ignace, Ste. Marie, St. Jean. The inmates who escaped the general slaughter sought safety in flight. A portion established themselves in Manitoulin Island; others, and they fared the worst, sought protection on the south shore of Lake Erie, from the Erie tribe and were incorporated with them. A Jesuit Father escorted three or four hundred of these terror stricken people to Quebec, on the 25th July, 1650, and located them on land at the Island of Orleans, where a picket fort was erected for their protection, at a cove called on that account L'Anse du Fort.

Even under the protection of this little fort, the tomahawk and scalping knife of their implacable foes found them out. Six of their number were butchered and eighty-five carried into captivity by the Iroquois, on the 20th May, 1656. They fled to Quebec in June following, and obtained leave to camp under the big guns of Fort St. Louis, where they rested in comparative peace, until 1666, when they removed to Beauport, where they were allowed to squat, for one year, on lands owned by the Jesuits.

In 1667, they left and pitched their wigwams four and a half miles west of Quebec, at the mission of Notre-Dame de Foye, now Ste. Foye.

On the 20th December, 1673, restless and alarmed, the helpless sons of the forest sought the leafy shades and green fields of Ancient Lorette. Twenty-four years later, in 1697, allured by the hopes of more abundant game, they packed up their household goods and settled on the elevated plateau, closeby the foaming rapids of St. Ambroise, now known as Indian or Jeune Lorette. From the date of the Lorette settlement, in 1697, down to the year of the capitulation of Quebec, 1759, the history of the tribe offers but few startling incidents; an annual bear, beaver, or cariboo hunt, or the departure or return of a war party with gory scalps—English probably, from the border warfare—as the tribe had a wholesome dread of meddling with Iroquois scalps. In their allegiance to France, they readily enlisted in its wars against Britain. We find them, trying their hands as friseurs on the wounded British, at Beauport flats, on 31st July, 1759: at the bloody defeat of Murray, on 28th April, 1760; at Ste. Foye, where Indian barbarity, on the dead and wounded was conspicuous.