* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Canadian Portrait Gallery - Volume 4

Date of first publication: 1881

Author: John Charles Dent (1841-1888)

Date first posted: Jan. 5, 2018

Date last updated: Jan. 5, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180106

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

In attempting to place before the public an account of the lives of the leading personages who have figured in Canadian history, from the period of the first discovery of the country down to the present times, the editor has encountered the difficulties incidental to such an undertaking. With respect to past times the principal difficulty has been one of selection. It has constantly been necessary to bear in mind the fact that the present is a Canadian, and not a mere Provincial work, and that many names must be excluded from its pages which would rightfully find a place in a Biographical Cyclopædia of a particular Province. During the period before the Conquest, for instance, there were many gallant gentlemen whose lives and achievements are pleasant to recall, and who left at least a temporary impress upon the civil, political and ecclesiastical institutions of New France. The interest in the lives of these personages, however, is for the most part confined to the inhabitants of the Lower Provinces, and only a few sketches of the lives of the more prominent among them could be admitted into the present work with due regard to their relative importance. Similar remarks are applicable to various personages who have played a not insignificant part in the history of the Maritime Provinces, and even to some who have figured in the annals of the Province of Ontario. It is believed, however, that no name of really national importance has been omitted, and that the selection has been made with due regard to the comprehensive scope of the work.

As respects the present day, it has been found necessary to adopt a much wider range. There are many living persons who, from the mere fact of their occupying more or less conspicuous positions, are entitled to notice in the work, but who would undoubtedly have had no place there by reason of their personal merits or abilities. This is an incident of every work which attempts to deal with contemporaneous biography, and it is one which can neither be ignored nor surmounted.

The four volumes comprised in The Canadian Portrait Gallery contain, in addition to the title pages and tables of contents, 960 printed pages. The number of sketches is 204. For 185 of these, containing a total of 888 pages, the editor is personally responsible. A few of them had been published in a Toronto newspaper prior to their appearance in this work, but the sketches so previously published were subjected to a thorough revision, and in most cases a good deal of important matter was added. The remaining 16 sketches, containing an aggregate of 72 pages, are the work of five valued contributors. The sketch of Sir John A. Macdonald was prepared by Mr. Charles Lindsey, of Toronto, whose "Life and Times of William Lyon Mackenzie," published nearly twenty years ago, made his name known from one end of this country to the other. The sketch of Sir George E. Cartier is the work of a writer well fitted for such an undertaking by his personal acquaintance with that gentleman during the latter's lifetime. The sketches of the Rev. Dr. Crawley, Sir Samuel Cunard, and the Hon. S. H. Holmes were contributed by the Rev. Robert Murray, editor of the Presbyterian Witness, of Halifax, N.S. The sketch of Sir Dominick Daly was written by Sir Francis Hincks, whose intimacy with Sir Dominick during that gentleman's residence in Canada, and whose active participation in the political life of the time render him peculiarly well qualified for the task. The remaining contributor is Mr. George Stewart, jr., editor of the Quebec Chronicle, a gentleman well-known to the Canadian public as the author of "Canada under the Administration of the Earl of Dufferin," and of other valuable historical and literary works. Mr. Stewart's contributions consist of the sketches of Sir S. L. Tilley, The Hons. A. G. Archibald, T. A. R. Laflamme, R. E. Caron, E. B. Chandler, J. C. Allen, C. E. B. De Boucherville, H. G. Joly, T. W. Anglin, J. J. C. Abbott, Sir William Young, Mgr. Laval, and the Most Rev. John Medley. The editor deems it right to take this opportunity of bearing public testimony to his high sense of the services of his friends above referred to, and to the pleasant nature of his relations with them during the progress of this work through the press.

With respect to the literary execution of the work, it is hoped that it will be found to maintain the promises made on its behalf in the prospectus issued towards the close of the year 1879. "In this country"—so ran the prospectus—"where political issues develop strong sympathies—and even prejudices—it is of the first importance that the sketches of public men shall be written with justice, and with entire freedom from political bias. This difficult task—difficult, more especially in the case of living persons—the editor will endeavour faithfully to discharge." It is scarcely to be expected that the editor's estimate will in every case meet with universal acceptance. It is believed, however, that no reader will dispute the fact that there has been an honest attempt to do justice to the character and actions of every man whose life is delineated in these volumes. It was a matter of course that a work of such dimensions would not pass through the press without some errors creeping into it, in spite of the utmost care in reading and correcting proof-sheets. The Canadian Portrait Gallery doubtless contains many such. Several of the more important may as well be referred to in this place, as it is not proposed to issue a table of errata. The first error occurs on the very first page of the first volume, in the sketch of the present Governor-General of Canada. It is stated that Archibald, Marquis of Argyll, was brought to the scaffold during the Protectorate, for his espousal of the Royalist cause. As matter of fact the Marquis was beheaded on the 27th of May, 1661, after the Protectorate had come to an end; and his execution was due to his having intrigued with Cromwell, and engaged in a treasonable correspondence with General Monk. Another error occurs on page 53 of the third volume, in the sketch of the Hon. William Hume Blake. A tribute to the deceased Chancellor's memory is quoted as having been pronounced by the late Chancellor Vankoughnet, when as matter of fact the tribute was pronounced by the present Chief Justice Spragge. The critical reader will also notice that the surname of Sir Allan MacNab is spelled in various ways in different sketches. This can scarcely be pronounced an error, as different branches of his family spell the name in a variety of ways. It would have been preferable, however, had the spelling been uniform throughout the work. As matter of fact Sir Allan—at all events during the latter years of his life—always spelled the name as it will be found spelled in the sketch of his life contained in the fourth volume—MacNab. The ecclesiastical prefix "Most Reverend" was accidentally omitted in the title to the sketch of Archbishop Connolly; and the prefix "Sir" from the title to the sketch of Sir W. P. Howland. There are doubtless other errors which have not been detected by the editor, but it is believed that there are no others of importance.

During the passage of the work through the press, various events have occurred which affect the text as it stands, and which may appropriately be recorded here. On the 4th of January last the Judicial Bench of Ontario sustained a grievous loss by the death, at Nice, France—whither he had gone for the improvement of his health—of Chief Justice Moss. On the 28th of the same month the Hon. Mr. Letellier died at his home in the county of Kamouraska. The Rev. Dr. Punshon died in England on the 14th of April last. The services of Lord Dufferin at St. Petersburg have come to an end, and he is about to take up his abode in a diplomatic capacity at Constantinople. The Hon. F. G. Baby has ceased to be a member of the Government at Ottawa, and has accepted a seat as one of the Judges of the Court of Queen's Bench for the Province of Quebec. The Hon. James McDonald, late Minister of Justice, has succeeded Sir William Young as Chief Justice of Nova Scotia. The Hon. J. G. Spragge has ceased to be Chancellor of Ontario, and has become Chief Justice of the Court of Appeal. The Hon. S. H. Blake has retired from the Bench, and has resumed practice at the Ontario Bar. On the 24th of May the Hon. Hector Langevin and Chief Justice Ritchie were created Knights Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. There have also been several other changes in the composition of the Dominion Government, but as they are understood to be of only a temporary nature, it is considered unnecessary to specify them.

Toronto, June 1st, 1881.

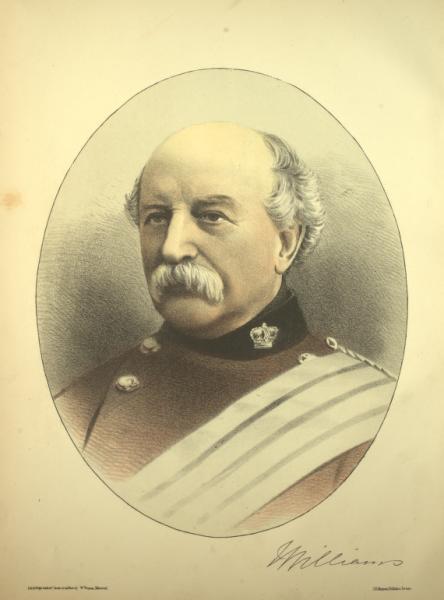

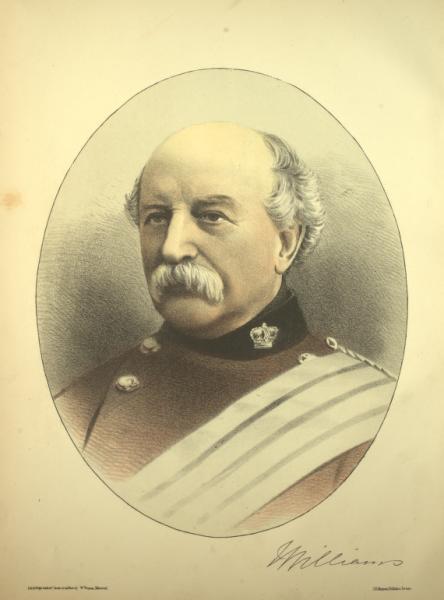

To tell the story of the life of "the Hero of Kars" as it deserves to be told, and as it will assuredly have to be told in the not distant future, would require much greater space than can be allotted for the purpose in the present work. The life of Sir Fenwick Williams, like that of his friend and fellow-countryman Sir John Inglis, forms a glorious chapter in the history, not of Nova Scotia alone, but of the British Empire, in which it must ever occupy a conspicuous and an honoured place. In the annals of the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny—two of the most notable conflicts of modern times—the names of these gallant sons of Nova Scotia stand out in bold relief. The career of Sir John Inglis was brought to a close eighteen years ago. Sir Fenwick Williams, though he has passed by a decade the allotted term of three score years and ten, is happily still preserved to us. His life is co-existent with the present century, the history of which he has materially contributed to make. In none but a conventional sense can he be said to have fallen into the sear and yellow leaf. It would be too much to expect that a veteran of fourscore will add fresh lustre to his name by any further military achievements, but he is fully entitled to repose under the shade of his laurels for the remainder of his days, surrounded by

He comes of military stock on both sides of his house. His father, of whom he is the only surviving son, was Thomas Williams, Commissary-General and Barrack Master at Halifax, who subsequently rose to the rank of a Lieutenant-Colonel, and who died in 1807. His mother was Maria, daughter of Captain Thomas Walker. He was born at Annapolis Royal, the ancient capital of Nova Scotia, on the 4th of December, 1800.1 He had an elder and only brother, Lieutenant Thomas Gregory Townsend Williams, of the Royal Artillery, who served under Wellington in the Peninsula and in France, and who died after the combat at New Orleans in 1814-15.

For the greater part of his early training, military and otherwise, he was indebted to his relative, Colonel William Fenwick, of the Royal Engineers. In May, 1815, through the influence of the Duke of Kent, who was a friend and patron of his father, he was placed at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, in England. While there he developed a passion for a military life, and studied military tactics with extraordinary diligence. In 1821 he passed a very successful examination, and in 1825 was gazetted to a second lieutenancy in the Royal Artillery. Two years later he was promoted [Pg 6]to a first lieutenancy, and was stationed at Gibraltar. In 1829 he was transferred to the East Indies, and was stationed in the island of Ceylon. He spent considerable time in travelling through India in the capacity of a military engineer, and penetrated to districts which were known to few Europeans in those days. Through the good offices of Sir Robert Wilmot Horton, he obtained an appointment in the department of the Surveyor-General of Ceylon, where he superintended the erection of various public buildings and bridges, and the construction of several highways in the neighbourhood of Colombo, the capital of the island. Towards the close of 1835 he bade adieu to India and proceeded to Egypt, where he formed the acquaintance of the Viceroy, the famous Mehemet Ali. Thence he proceeded to Syria and Constantinople, and, after a somewhat prolonged sojourn at the Turkish capital, returned to England in 1839 and rejoined his regiment. Early in the following year he was promoted to a captaincy.

During his stay in Constantinople he had been presented to Mahmoud II., the Sultan, whose authority his great feudatory, Mehemet Ali, had nearly succeeded in throwing off. The young English officer had thus had an opportunity of personally estimating the respective characters of these illustrious personages, and of forming a more intelligent opinion as to the merits of the controversy between them than any one who had not travelled in their dominions could have been expected to do. The Sultan died about this time, and was succeeded by his son Abdul Medjid, who inherited but a very moderate share of his father's statesmanship and energy. Great Britain, being then, as in times much more recent, suspicious of Russian intrigues, and having resolved upon "maintaining the integrity" of the Ottoman Empire, prepared to interfere in the quarrel between the Sultan and his insubordinate vassal. While the preparations were afoot, Lord Palmerston, who was Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, sent down to Woolwich a requisition for an energetic and capable artillery officer, who was to proceed to the Turkish capital and inspect the arsenals there. The object of such inspection was to remedy the numerous deficiencies which were believed to exist, and to put the Turkish marine in an efficient state of defence. Captain Fenwick Williams was the officer selected for this important duty. He repaired to Constantinople, and served in the arsenals there for three years. Towards the close of the year 1843 he received his majority, and immediately afterwards proceeded as British Commissioner to the conference held at Erzeroum, in Upper Armenia, with a view to a settlement of the boundary-line between Persia and Turkey in Asia. The commissioners were four in number, and represented Great Britain, Russia, Turkey and Persia. Their conference lasted about four years, and after the Treaty was signed the commissioners were detailed to see its more important provisions carried out. This involved an official survey of the entire territory lying between Mount Ararat and the head of the Persian gulf. The survey occupied several years more, during the greater part of which period the commissioners were compelled to endure many privations and hardships. They slept under canvas tents, and were exposed to terrible vicissitudes of alternate heat and cold. While engaged in his labours he was prostrated by a serious illness, and was compelled to return to England.

For his services in connection with the making of the Treaty of Erzeroum he had been advanced, in 1848, to the brevet rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. During his illness the Crimean War was entered upon, and scarcely had he recovered ere the news reached England that the Turkish forces had been driven under the walls of Kars [Pg 7]by the Russians under Prince Bebutoff. The intelligence was regarded as momentous, as it was considered certain that the Russians would follow up their success by renewed efforts in Asia. It was highly desirable that Great Britain should have a representative there, to keep her informed of the state of the respective armies, and as to the general course of events. Colonel Williams, who was thoroughly familiar with the ground, and of whose abilities the War Office justly entertained a very high opinion, was forthwith despatched to the scene of action as Her Majesty's Commissioner. He reached Constantinople on the 14th of August, 1855, and put himself into immediate communication with Lord Raglan, Commander of the British Forces in the Crimea, and with Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, the British Plenipotentiary at Constantinople. He then set out for his destination, accompanied only by three men, viz.: Lieutenant Teesdale, Mr. Churchill, and Dr. Sandwith. On the 24th of September the little party reached Kars, and Colonel Williams forthwith set himself to work to reorganize the Turkish forces. He found that there had been gross peculation and mismanagement, and that the equipments and commissariat were in a wretched condition. The army was an unsightly rabble in rags and tatters, bearing, except in the matter of numbers, considerable resemblance to that famous regiment with which Sir John Falstaff refused to march through Coventry. The rations served out to the men were scanty and foul. The officers were shiftless and incompetent. The payment of the troops was more than twelve months—and in some cases more than twenty-two months—in arrear. As a result, a state of insubordination prevailed. Drill was altogether neglected, and many of the troops were absolutely too lazy to take exercise. Such was the condition of things which prevailed when Colonel Williams arrived at Kars.

His first proceeding was to send off despatches to Constantinople representing the state of affairs. His next was to make an attempt to evoke some sort of order out of the chaos which prevailed all around him. Upon receipt of the despatches Lord Stratford de Redclifte submitted the situation to the Turkish Government, and urged them to find a remedy. In response to this appeal the Turkish Government sent to Kars an insolent and incapable drunkard named Shukri Pasha, who, instead of being of any service to Colonel Williams did all he could to thwart his efforts at reorganization. The Colonel, after much routine and delay, was appointed a Lieutenant-General in the Sultan's service. In his commission he was styled Williams Pasha; and this is the first instance on record of a Christian being appointed to high rank in the service of the Sublime Porte under his own proper name. The custom had previously been to bestow Moslem names upon such officers, when promoting them to positions of distinction. In the following November Lieutenant-General Williams, repaired to Erzeroum, which he placed in as efficient a state of defence as the means at his disposal rendered possible, leaving Lieutenant Teesdale behind at Kars to maintain discipline there. In the following spring he was reinforced by Colonel Lake, Captain Olpherts, and Captain Thompson, from the Indian army. The fortifications at Kars were strengthened and largely reconstructed, and provisions were stored up for a siege, for it was known that a strong Russian force under General Mouravieff would attempt to take the place. The attempt was not long delayed. "Never, probably," says a recent historian, "had a man a more difficult task than that which fell to the lot of Williams. He had to contend against official stupidity, corruption, delay; he could get nothing done without having first to remove whole mountains of [Pg 8]obstruction, and to quicken into life and movement an apathy which seemed like that of a paralyzed system. He concentrated his efforts at last upon the defence of Kars, and he held the place against overpowering Russian forces, and against an enemy far more appalling, starvation itself. With his little garrison he repelled a tremendous attack of the Russian army under General Mouravieff, in a battle that lasted nearly seven hours, and as the result of which the Russians left on the field more than five thousand dead. He had to surrender at last to famine; but the very articles of surrender to which the conqueror consented became the trophy of Williams and his men. The garrison were allowed to leave the place with all the honours of war, and 'as a testimony to the valorous resistance made by the garrison of Kars, the officers of all ranks are to keep their swords.' Williams and his English companions—Colonel Lake, Major Teesdale, Major Thompson and Dr. Sandwith—had done as much for the honour of their country at the close of the war as Butler and Nasmyth had done at its opening. The curtain of that great drama rose and fell upon a splendid scene of English heroism. The war was virtually over."

General Williams and his valiant comrades in arms were taken to Russia as prisoners of war—first to Moscow, and afterwards to St. Petersburg; but they were treated with the courtesy and respect due to brave enemies. Immediately after the conclusion of terms of peace they left for England, where they landed, amid the acclamations of the entire British nation, in May, 1856. Honours flowed in upon General Williams thick and fast. A Baronetcy and a Companionship of the Bath were conferred upon him, and a pension of a thousand pounds a year was granted to him for life. The House of Lords and the House of Commons vied with each other to do honour to the hero who had so valiantly maintained the national prestige against overwhelming odds. Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, in a speech in the Commons, while reproaching the Government for its mismanagement of affairs in the East, said: "The stain of the fall of Kars will still cling to your memory as a Government, as long as history can turn to the record of a fortitude which, in spite of your negligence and languor, still leaves us proud of the English name." The Earl of Derby, in the House of Lords, said: "We honour the valour and prize the fame of the brave but unsuccessful defenders of Kars as not below those of the more fortunate conquerors of Sebastopol." The Sultan of Turkey conferred upon the Hero of Kars the dignity of a Pasha or Medjidie of the highest rank, together with the title of "Mushir," or full General in the Turkish service. The Emperor of the French created him Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour, and personally presented him with a diamond-hilted sabre. But perhaps no token of the esteem in which he was held affected the recipient more than one from his native Province of Nova Scotia. The Attorney-General of that Province, Mr.—now Sir William—Young, made a motion in the Local House of Assembly to the effect that the Lieutenant-Governor should be requested to expend a hundred and fifty guineas in the purchase of a sword, to be presented to General Williams as a mark of the high esteem in which his character as a man and a soldier, and more especially his heroic courage and constancy in the defence of Kars, were held by the Legislature of his native Province. The Hon. J. W. Johnston seconded the resolution—which passed unanimously—in eloquent terms. The General's appreciation of the honour is sufficiently attested by a letter which he addressed from Berlin, Prussia, to a gentleman in Halifax, under date of May 28th, 1856: "How thankful I [Pg 9]ought to be"—so runs the letter—"and indeed am, to God for having spared me through so many dangers, to serve the Queen in such a manner as to obtain her approbation, and the good will of all my countrymen on both sides of the water. Of all the proofs which I have, or shall receive of this too general sentiment in my favour, the sword voted to me by the Nova Scotians is the most acceptable to my heart; and when I again come in sight of the shores of that land where I first drew my breath, I shall feel that I am a thousand times requited for all I have gone through during the eventful years of the last terrible struggle."

In the way of lesser honours, the University of Oxford, at the annual commemoration of 1856, conferred upon General Williams the honorary degree of D.C.L. The Corporation of London invested him with the freedom of the city, accompanying the investiture by the gift of a costly sword. In the month of July, 1856, he was appointed to the command of the garrison at Woolwich, and was about the same time returned to the House of Commons in the Liberal interest as representative of the borough of Calne. He was again returned for the same constituency at the general election of 1857. About two years later he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the forces in British North America, and upon his arrival in his native land he was received with salvos and acclamations from one end of the Province of Nova Scotia to the other.

The subsequent important events in his life may be chronicled very briefly. From the 12th of October, 1860, to the 22nd of January, 1861, he administered the Government of Canada during the absence of the Governor-General, Sir Edmund Head. He also administered the Government of Nova Scotia for some time after the departure from that Province of Sir Richard Graves Macdonnell, in 1865. As senior military officer, he was appointed the first Lieutenant-Governor of that Province, after the accomplishment of Confederation, and retained that position until the month of October, 1867. On the 2nd of August, 1868, he was raised to the full rank of a General in the British Army; and in the course of the following year he was appointed Governor-General of Gibraltar, as successor to Lieutenant-General Sir R. Airey. He administered the Government there until the month of November, 1875, when he resigned. In October, 1877, he retired from the army, since which time he has not taken any prominent part in public affairs. A few weeks ago he was appointed Constable of the Tower of London, a position which he still retains. At the present time, though he has passed his eightieth year by several months, he retains a large measure of vigour.

Archbishop Taschereau is descended from Thomas Jacques Taschereau, a French gentleman who emigrated from Touraine to Canada during the early years of the seventeenth century, and whose descendants have ever since been conspicuous members of society in the Province of Quebec. Soon after the arrival of the founder of the Canadian branch of the family in the Province he was appointed to the post of Marine Treasurer, and in 1736 he received a grant of a seignory on the banks of the River Chaudière. The present Archbishop of Quebec is the grandson of this gentleman, and was born at Ste. Marie de la Beauce, on the 17th of February, 1820. When only eight years of age he was sent to the Quebec Seminary, where he soon became distinguished for his diligence and cleverness. In 1836, when he was in his seventeenth year, he visited Rome in company with the Abbé Holmes, of the Seminary, and in the following year received the tonsure at the hands of Monseigneur Piatti, Archbishop of Trebizonde, in the Basilica of St. John Lateran. Later in the same year he returned to Quebec, and commenced his theological studies, which, with other branches of learning, occupied his attention for about six years, when, though he was still under canonical age, he was ordained Priest. His ordination took place on the 10th of September, 1842, at the Church of Ste. Marie de la Beauce, his native place, in the presence of Monseigneur Turgeon, then Coadjutor, and subsequently successor to Archbishop Signai.

Within a short time after his ordination he was appointed to the Chair of Philosophy in the Seminary, and this position he held for a period of twelve years. An episode in his life during this interval deserves to be recorded in a permanent form. About thirty miles below Quebec, in the middle of the River St. Lawrence, opposite the village of St. Thomas, is an island, the chief use of which is for a quarantine station for emigrants, and the name of which is Grosse Isle. In the year 1847 a malignant fever broke out with great virulence among the emigrants there. It ran a rapid course, and the victims died in great numbers. The emigrants at that time were chiefly composed of Irish Roman Catholics, who had been driven by poverty and famine to seek an asylum in Canada. Their vitality had been much impaired by starvation and suffering, and they fell easy victims to the terrible pestilence, which in some cases carried them off in a few hours. The greater part of the island was for a short time little better than a mass of loathsomeness and pestilence. The heroism which enables a man to face such a danger as this is quite as praiseworthy as that more demonstrative courage which enables him to walk up to the mouth of a cannon. Father Taschereau felt the call of duty, and volunteered his services to assist the Rev. Father McGavran, who was then [Pg 11]Chaplain at Grosse Isle, to minister to the spiritual necessities of the victims of the pestilence. His proposal was thankfully accepted, and he landed on the island, where he remained until he himself was struck down by the scourge, and brought literally to death's door. His conduct at this time endeared him very much to the Irish Catholic population of Quebec.

In 1854 he again repaired to Rome, charged by the second Provincial Council of Quebec to submit its decrees for the sanction of His Holiness. He spent two years in the capital of Christendom, during which period he occupied himself chiefly in studying the Canon Law. In July, 1856, the Roman Seminary conferred upon him the degree of Doctor of Canon Law. He soon afterwards returned to Quebec, where he was appointed Director of the Petit Seminaire, a position which he filled until 1859, when he was elected Director of the Grand Seminaire, and appointed a member of the Lower Canada Council of Public Instruction. In 1860 he became Superior of the Seminary and Rector of Laval University. In 1862 he accompanied Archbishop Baillargeon to Rome, and upon his return the same year, was appointed Vicar-General of the Archdiocese of Quebec. In 1864 he again visited Rome on business connected with the University. His term of office as Superior having expired in 1866, he was again appointed Director of the Grand Seminaire, which office he held for three years, when he was reëlected Superior. He again accompanied Archbishop Baillargeon to Rome when the Œcumenical Council was held, and on his return resumed his duties as Superior of the Seminary and Rector of the University. After the death of the Archbishop, in October, 1870, he administered the affairs of the Archdiocese conjointly with Grand Vicar Cazeau. On the 13th of February, 1871, it was announced that he had been appointed successor to the late Archbishop, and on Sunday, the 19th of March, he was consecrated in the presence of a vast concourse of people, many of the clergy of the diocese, and of the Bishops of Quebec and Ontario, the Archbishop of Toronto officiating. From that time down to the present, Archbishop Taschereau has discharged the onerous duties of his dignified position with entire acceptance. He is held in honour by persons of all classes and creeds, and watches with zealous care over the many and various interests committed to his charge.

The Chief Justice of the Court of Queen's Bench for Ontario was born at Dublin, Ireland, on the 17th of December, 1816. His father, Mr. Matthew Hagarty, was a gentleman of refined and scholarly tastes, and at the time of his son's birth held the post of Examiner of His Majesty's Court of Prerogative for Ireland. The future Chief Justice received his early education at a private school in Dublin taught by the Rev. Mr. Haddart. Soon after entering upon his sixteenth year he entered as a student at Trinity College, where he was known for a bright intelligent boy, and was very popular among his fellow-scholars. He was also known as a diligent, although somewhat fitful student, with a ready grasp of the salient points of a lesson. He made rapid progress during his brief collegiate career, and devoted himself with much ardour to classical studies. His fondness for such studies has accompanied him throughout the subsequent years of a busy and useful life. It is to be regretted that a scholastic career of such promise should have been so early broken off. He did not remain long enough at college to obtain his degree, as he became infected with the mania for emigration which was so common among clever and spirited young Irishmen at that period. In 1834 he bade adieu to his native land, and made his way to Canada. In the course of the following year he reached Toronto, which had been incorporated only a few months before (in March, 1834), and which was growing rapidly. There he pitched his tent, and there he has ever since resided. That he should succeed in such a community—or indeed in almost any community—was a matter of course. He had brilliant abilities, a pleasing manner, high principles, and much strength of will. He studied law in the office of the late Mr. George Duggan, and was called to the Bar of Upper Canada in Michaelmas Term, 1840. There were many strong men at the local Bar in the early years of the Union of the Provinces. Robert Baldwin, William Hume Blake, Henry Eccles, William Henry Draper, Robert Baldwin Sullivan and John Hillyard Cameron were all formidable competitors in the race for professional distinction. Young Mr. Hagarty took his place by their side, and won his full share of fame and honour. He had an ingratiating manner with juries, and never failed to do full justice to any case in which he was engaged. His language was apt and incisive, and his conduct and demeanour were uniformly marked by a high-minded respect for himself and his profession. He prospered in his calling, and no one grudged him his prosperity. The usual inducements were held out to him to enter political life, but he preferred to confine himself to the profession in which he had already won a proud position. He interested himself in municipal affairs, however, and in 1847 was an Alderman of the [Pg 13]city. In course of time he formed a partnership with the late Mr. John Crawford, who in after years represented East Toronto in the Canadian Assembly, and finally became Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario. This partnership, which was carried on under the style of Crawford & Hagarty, existed for many years, and in fact was only dissolved when Mr. Hagarty retired from practice and accepted a seat on the Judicial Bench. In 1850, during the tenure of office of the second Baldwin-Lafontaine Administration, he was appointed a Queen's Counsel, and he frequently thereafter represented the Crown in important cases, both civil and criminal.

In the society—and more especially in the most cultivated literary society—of Toronto, Mr. Hagarty had ever since his arrival been regarded as a decided acquisition. He had fine taste, brilliant powers of conversation, wide acquaintance with ancient and modern literature, and a never-failing fund of ready humour. He was, like every other true Irishman, fond of poetry, and did not disdain to occasionally throw off a few verses on his own account. He contributed several poetical effusions to the "Maple Leaf," a costly illustrated Annual set on foot, in 1847, by his friend and fellow-countryman Dr. McCaul. The most noticeable thing about these contributions is their exquisite perfection of rhythm, but they display a certain degree of genuine poetic inspiration, and are of a much higher class of workmanship than the conventional "offerings" in the English Annuals of that date. He is also known as an author by a pamphlet entitled "Thoughts on Law Reform," published in Toronto a few years ago. During the early years of his career in Upper Canada he was also a frequent contributor to the newspaper press, and many of the smart, crisply-written paragraphs of that day were attributable to his pen.

Mr. Hagarty was also an active member of the Canadian Institute, in the proceedings of which he has taken a warm interest ever since its foundation, and of which he has once or twice been elected President. The St. Patrick's Society was another organization with which he allied himself early in his professional career. He was President of the latter Society in 1846.

His elevation to the Bench took place on the 5th of February, 1856, when he was appointed a Puisné Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. This dignity he retained until the 18th of March, 1862, when he was transferred to the Court of Queen's Bench, where he remained until the 12th of November, 1868, when he was appointed Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, as successor to the Hon. (now Sir) William Buell Richards, who had been promoted to the dignity of Chief Justice of Ontario. Immediately after the death of the late Chief Justice Harrison, Mr. Hagarty became Chief Justice of the Court of Queen's Bench for Ontario, which position he still retains. He is a sound and well-read lawyer, and his expositions of the law are clear and lucid. His quickness of perception has long been proverbial among the profession. He grasps the points of an argument almost before it has been uttered, and if there be any fallacy about it, it is rarely necessary for the opposing counsel to urge it upon the attention of the Court. His judicial humour is another characteristic which has long been recognized by the profession. He sees the ludicrous, as well as the legal side of a question, and has the faculty of presenting it in a light which is sometimes irresistibly provocative of laughter. Many of his humorous sayings have passed into currency among his brother judges and professional men. Alike as a man and a judge he is held in the highest respect, and his written judgments are equally conspicuous for elegance of diction and profound learning.

The Bishop of Rupert's Land is a son of Mr. Robert Machray, advocate, of Aberdeen, Scotland. He was born at Aberdeen in the year 1832, and in his early boyhood entered King's College, University of Aberdeen, for the purpose of receiving a clerical education. He graduated in 1851, and subsequently entered Sidney College, Cambridge, where he graduated as B.A. in 1855, taking high honours in mathematics. He in due course obtained the degrees of M.A. and D.D. Immediately after receiving his baccalaureate degree he was elected a Foundation Fellow of Sidney College, and in the course of the same year was advanced to Deacon's Orders by His Grace the Lord Bishop of Ely. In 1856 he was advanced to the Priesthood by the same Prelate. In 1858 he was elected Dean of his College. In 1860 and 1861 he was University Examiner, and in 1865 he became Ramsden University Preacher.

For several years prior to his elevation to the Episcopate he officiated as Vicar of Madingley, a village situated about five miles west of Cambridge. In 1865 he was appointed by the Crown as Bishop of Rupert's Land, and was consecrated at Lambeth Palace by the Archbishop of Canterbury, assisted by the Bishops of London, Ely, and Aberdeen, and by the Right Rev. David Anderson, a former Bishop of Rupert's Land. His first exercise of his Episcopal functions consisted of the holding of an ordination for the Bishop of London, whereat he ordained to the Priesthood the Rev. William Carpenter Bumpus, the present Bishop of Athabasca, in the North-West Territories.

Bishop Machray's Episcopate has been marked by great progress in the welfare of the Church of England in his diocese. The diocese of Rupert's Land was originally constituted in 1849, and comprehended the whole of what now forms the Province of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. The subsequent formation of separate bishoprics curtailed the See of its proportions. The See of Rupert's Land now consists of the Province of Manitoba, with part of the District of Cumberland, and the Districts of Swan River, Norway House, and Lac La Pluie. In 1874, on the subdivision of the diocese, Bishop Machray was chosen Metropolitan, under the Primacy of the Archbishop of Canterbury. He is held in very high esteem throughout his diocese, and has done much to promote the cause of education. He is Chancellor and Warden of St. John's College, Manitoba, and is also Professor of Ecclesiastical History in the Theological College. His sermons and charges to his clergy are marked by practical good sense, and his manner, whether in the pulpit or out of it, is eminently calculated to make for him many friends. Though he makes no pretence to brilliancy of diction or extraordinary gifts of oratory, he is capable of rising, upon an important occasion, to a high degree of eloquence and spiritual fervour.

The honour of being the original discoverer of the American continent is commonly vouchsafed, by persons who do not read, to Christopher Columbus. As matter of fact the honour belongs neither to him nor to the mendacious Florentine, Amerigo Vespucci, who was the first to publish an account of the New World which bears his name. Leaving the mythical accounts of western voyages by the Welsh and Irish out of the question, as well as the semi-mythical discoveries of the Norsemen in the ninth and tenth centuries, Columbus may justly lay claim to having led the van in the way of American discovery, and to have wrested from the western seas the marvellous secret which they held hidden in their bosom. Columbus deserves all the credit which even the most partial writers have claimed on his behalf. His merits as a discoverer and a man of genius have long been matters beyond dispute, and the brightness of his fame can never be tarnished. But, saving the more or less mythical personages above-mentioned, the first discoverer of the mainland of America—the first man to set foot upon its shore, and to hold personal communication with its inhabitants—was the intrepid navigator whose name stands at the head of this sketch.

Sebastian Cabot was of Venetian extraction, but of English birth, having been born at Bristol—then the first of English seaports—sometime in the year 1477. His father, Giovanni Cabotta, was a native of Venice, and was engaged in various maritime operations of considerable magnitude, which compelled him to reside almost entirely in England for many years. As the time passed by he became to all practical intents an Englishman. His sympathies, language, and habits of thought were all of the land in which he dwelt, and he even Anglicized his name, and was known as John Cabot. He was a man of some learning and enterprise, and is entitled to a share of the honour accorded to his more celebrated son.

The precise day upon which Sebastian Cabot was born is unknown. There was formerly a dispute as to his birthplace, but that point may now be said to be definitely settled. There does not seem to have been any good ground for difference of opinion about the matter at any time. It arose from conflicting expressions in various authors, some of whom wrote under the belief that he had been born at Venice. Purchas says of him ("Pilgrims," vol. iii., p. 901), "He was an Englishman by breeding, borne a Venetian, but spending most part of his life in England, and English employments." Harris, in his "Collection of Voyages," vol. ii., p. 191, has the following:—"Sebastian Cabote is, by many of our writers, affirmed to be an Englishman, born at Bristol, but the Italians as positively claim him for their countryman, and say he was born at Venice, which, to speak impartially I believe to be [Pg 16]the truth, for he says himself, that when his father was invited over to England, he brought him with him, though he was then very young." Other writers have indulged in similar remarks, which were probably made in good faith. The impression that he was by birth an Italian, however, was clearly erroneous. The navigator's own statement to Richard Eden, a careful writer and a contemporary and personal friend of Sebastian, was sufficiently explicit. "Sebastian Cabot tould me," says Eden, "that he was borne in Brystowe, and that at iiii. yeare ould he was carried with his father to Venice, and so returned agayne into England with his father after certayne years, whereby he was thought to have been born in Venice." The work in which these words occur ("The Decades of the New World," fol. 255,) was originally published in the English language in 1612. Its accuracy, so far as we know, has never been disputed by any one; notwithstanding which we find the Quarterly Review, vol. xvi., p. 154, commenting upon the credit due to England, for having "so wisely and honourably enrolled this deserving foreigner in the list of her citizens." Since the publication of Mr. Richard Biddle's "Memoir," in 1831, there has never, we presume, been any doubt as to Sebastian Cabot's birthplace.

The only information obtainable with respect to his youth is that he was carefully instructed in mathematics and navigation, and that he made several more or less extended voyages in his father's company before he was twenty years of age. There is ground for believing that one of these voyages extended to Iceland, and probably as far as Greenland. The great discoveries of Columbus in the western seas inflamed all the maritime powers of Europe with a passion for exploration. The Spanish court did its utmost to keep the momentous secret, but in vain. It was a secret which could not be kept. Among the enterprising mariners who were roused to a high degree of enthusiasm by the wonderful news was John Cabot, who applied to King Henry VII. for a patent of exploration, with the ostensible view of finding a short route to the Indies. Henry, who had narrowly missed securing the services of Columbus, was willing enough to encourage such an undertaking. On the 5th of March, 1496, a patent was granted to John Cabot and his three sons, Lewis, Sebastian and Santius, authorizing them to seek out, subdue and occupy, at their own charges, any regions which before had "been unknown to all Christians." Permission was given to the patentees to set up the royal banner of England, and to possess any territories discovered by them as the king's vassals. The expedition consisted of five vessels, and sailed from Bristol in the month of May, 1497. There is no evidence that either John, Lewis or Santius accompanied it, though the weight of testimony is in favour of the father's having done so. Sebastian was learned and mature beyond his years, and was certainly the chief director of the expedition. He embarked on board the Matthew, and sailed in a north-westerly course until he reached the fifty-eighth degree of north latitude,2 when the intense cold and floating masses of ice compelled him to steer to the south-west. He had a fair wind, and at five o'clock in the morning of the 24th of June he came in sight of land. This land he christened Prima Vista, because it was his first view of a region hitherto unknown to Europeans. Much learning has been expended in attempts to establish with certainty the precise locality of this land, which has been variously represented as Labrador, the island of Newfoundland, the island of Cape Breton, and the peninsula of Nova Scotia. It is claimed by some writers that Cabot entered Hudson's Bay during this expedition, and one goes even so far as to [Pg 17]state, without offering a particle of evidence in support of the assertion, that he (Cabot) ascended the river subsequently called St. Lawrence as far as the mouth of the Saguenay. Much must necessarily be matter of conjecture. The map of the course pursued by the expedition, which was made either by Cabot himself or under his personal supervision, was engraved in 1549 by one Clement Adams, and formerly hung in Queen Elizabeth's gallery at Whitehall. It has long since disappeared, and it is thus impossible to fix the route with any approach to certainty. The royal patent issued during the following year, however, seems to recognize the fact that "a Londe and Isles" had been discovered during the expedition; and it is at least tolerably clear that Sebastian Cabot, during the summer of 1497, sighted and landed on the American continent—probably on the coast of Labrador—and that he was the first European who had done so since the days of the Norse expeditions of several centuries before.

Cabot returned to England with his vessels, and landed at Bristol in August, 1497. The king, as may well be supposed, was much gratified at the result of the expedition A second patent, being the one referred to in the foregoing paragraph, was issued to "John Kabotto, Venecian," on the 3rd of the following February. It authorized him, "by him, his deputie or deputies," to take six English ships of not more than 200 tons, and proceed to the land and islands previously discovered. John, the patentee, died before the preparations had been completed, and the two sons, Lewis and Santius, are supposed about this time to have settled in Italy. The expedition sailed from Bristol, under the command of Sebastian, in the following May. It seems tolerably certain that he penetrated into Hudson's Bay during this voyage, whatever may have been the fact with reference to that of the preceding year. He appears to have been accompanied by about three hundred men, with a view to colonization. The accounts of this second voyage, however, are exceedingly vague, and very little is definitely known about it. It is said that he sailed far to the northward, in the hope of finding a passage to the Indies; that when the sailors found themselves in such a desolate and unknown region, surrounded by icebergs and the various perils and discomforts of Arctic exploration, they refused to proceed farther, and broke out into open mutiny; that the commander therefore turned back and explored the American coast nearly as far south as Florida, after which, his stock of provisions having run short, he returned to England, taking with him three native Americans from northern climes.

His subsequent adventures have no special interest for Canadian readers, and may be given very briefly. In 1499 he engaged in an expedition to the Gulf of Mexico, as to which nothing specific is known. He subsequently entered the naval service of Ferdinand of Spain, and supervised a revision of the royal maps and charts. In 1517 he joined Sir Thomas Perte, Vice-Admiral of England, in an expedition to Spanish America. In 1518 he returned to Spain, where he is said to have been appointed Pilot-Major. He made other voyages to South America, hoping to discover a southern route to the Indies. He ascended the River La Plata and built a fort near one of the mouths of the Parana. He finally settled in England, and was actively employed in maritime affairs by the Government, who settled upon him a pension of two hundred and fifty marks. Hakluyt asserts that the office of Grand Pilot of England was created for, and conferred upon him, the duties of the office consisting of having "the examination and appointing of all such mariners as shall from this time forward take the charge of a Pilot or Master upon him in any ship within this our realm." It seems doubtful, however, [Pg 18]whether such an office ever existed in England. During the latter years of his life he disclosed to King Edward the phenomenon of the variations of the magnetic needle. His later life was distinguished by the organization of a company, and the equipment of an expedition which proved a great national benefit in opening a lucrative trade with Russia. His life, which was one of ceaseless physical and mental activity, was a long, and upon the whole a glorious one. His personal character is highly commended by all who have written about him. The precise date of his death, like that of his birth, is uncertain. He is presumed to have died in London, sometime in the year 1557. Even the place of his interment is unknown.

It is worth mentioning that a work published at Venice, in 1583, entitled "Navigatione nelle parte Settentrionale," has been attributed by many writers to Sebastian Cabot. Researches conducted during the present century, however, have established the fact that Cabot had nothing to do with the authorship of the work, which was probably written by one Stephen Burrough, an adventurous navigator of the sixteenth century. There is another error which is worth correcting, viz., that one or both of the Cabots (John and Sebastian) received the dignity of knighthood from King Henry VII., in testimony of his appreciation of their discoveries. The error was originally perpetrated by Purchas, who mistook the purport of an inscription under a portrait of Sebastian. The error was adopted as truth by Dr. Henry, in his "History of Britain," and from him has been copied by scores of writers who have been content to adopt blunders without investigation. In more than one history of Canada we find references to "Sir John Cabot." There never was any such personage. The fame of the Cabots rests on a higher and more solid foundation than any empty titular dignities which it is the province of kings to confer. A full exposure of the blunder will be found in Biddle's "Memoir," already quoted from.

An original portrait in oil of Sebastian Cabot, painted by the celebrated Holbein, is in existence. It was formerly placed in the royal picture gallery at Whitehall, but is now in private hands. It has several times been engraved, and is doubtless familiar to many readers of these pages.

Concerning the early life of Louis de Buade, Count de Frontenac, who has been called "the Saviour of New France," but little is known. He came of an ancient and noble race, said to have been of Basque origin, and was born in 1620, seven years after the marriage of his father, who held a high post in the household of Louis XIII., who became the child's godfather, and gave him his own name. Even the diligence and enthusiasm of Mr. Parkman have not enabled him to discover any further circumstances relating to the Count's childhood; and the known facts relating to his youth may be comprised within a very few lines. It appears that at the age of fifteen the young Louis showed an uncontrollable passion for the life of a soldier, and was sent to serve under the Prince of Orange, in Holland. Four years later, when he was nineteen, he was a volunteer at the siege of Hesdin. Next year he distinguished himself during a sortie of the garrison at Arras. At twenty-one he took part in the siege of Aire, and at twenty-two he was at the sieges of Caillioure and Perpignan. At twenty-three he became colonel of a regiment, and commanded in several battles and sieges during a campaign in Italy. He was repeatedly wounded, and in 1646 had an arm broken at the siege of Orbitello. He was then twenty-six years of age, and before the year was out he had been made a maréchal de camp—the French equivalent for the rank of a brigadier-general. A year or two later he was residing in his father's house in Paris; and these isolated facts include about all that is certainly known with respect to the first twenty-six years of the life of a man of whom Mr. Parkman says, "a more remarkable figure, in its bold and salient individuality and sharply marked light and shadow, is nowhere seen in American history."

The next episode in his career as to which we have any precise information is his marriage, which took place at the church of St. Pierre aux Bœufs, in Paris, in the month of October, 1648. His bride was the young and beautiful Mademoiselle Anne de la Grange-Trianon, whose portrait, painted as Minerva, hangs in one of the galleries at Versailles at the present day. She was one of the "professional" or court beauties of that day, and was the friend and companion of Mademoiselle de Montpensier, grand-daughter of Henry IV. Her marriage with Frontenac was contracted without the consent of her parents. It soon appeared that the romantic and wayward couple were unsuited to each other. The young wife conceived an aversion to her husband, and after the birth of a son she left his protection, and attached herself to the suite of Mademoiselle de Montpensier. The attachment between the two ladies was not permanent. They quarrelled, and the beautiful young Countess was dismissed. The latter seems to have intrigued to get her husband [Pg 20]sent out of the kingdom. The Count was in high position at court, and was possessed of fine and polished manners, as became one of his ancestry and rank. He is said to have been one of the many lovers of the famous Madame de Montespan, the haughty and extravagant mistress of the king, Louis XIV. He had, however, an imperious and at times ungovernable temper, and had run through his fortune. In 1669 he was chosen by the great Marshal Turenne to conduct a campaign against the Turks in Candia, where he displayed dauntless courage and high military ability to very little purpose. In 1672, after his return to his native land, he was appointed Governor and Lieutenant-General of New France. Various scandalous stories have been told as to the origin of his appointment. Several chronicles aver that the king was aware of his intimacy with Madame de Montespan, and wished to get him out of the way. St. Simon, on the other hand, says:—"He (Frontenac) was a man of excellent parts, living much in society, and completely ruined. He found it hard to bear the imperious temper of his wife, and he was given the government of Canada to deliver him from her, and afford him some means of living." He was at this time fifty-two years old. "Had nature disposed him to melancholy," says Mr. Parkman, "there was much in his position to awaken it. A man of courts and camps, born and bred in the focus of a most gorgeous civilization, he was banished to the ends of the earth, among savage hordes and half-reclaimed forests, to exchange the splendours of St. Germain and the dawning glories of Versailles for a stern gray rock, haunted by sombre priests, rugged merchants and traders, blanketed Indians, and wild bush-rangers. But Frontenac was a man of action. He wasted no time in vain regrets, and set himself to his work with the elastic vigour of youth. His first impressions had been very favourable. When, as he sailed up the St. Lawrence, the basin of Quebec opened before him, his imagination kindled with the grandeur of the scene. 'I never,' he wrote, 'saw anything more superb than the position of this town. It could not be better situated as the future capital of a great empire.'"

He forthwith set himself vigorously to work to reduce his dominions to a state of order. He convoked a council at Quebec, and administered an oath of allegiance to the chief personages of the colony. His principles of government were aristocratic and monarchical, and he founded the three estates of his realm—clergy, nobles and commons—with great pomp and solemnity. The clergy were ready-made to his hand in the persons of the Jesuits and seminary priests. To the three or four gentilshommes whom he found at Quebec, he added a number of officers, and these formed his nobility. The merchants and citizens constituted the third estate. The magistracy and members of council were formed into a distinct body. He made an oracular speech in which he informed his subjects that fealty to him was not only a duty, but an inestimable privilege. He also established a sort of municipal government at Quebec. He took kindly to the Indians, over whom he gained an extraordinary influence. But—and here was his gravest mistake of policy—he quarrelled with the clergy.

At the time of his arrival in the colony the priesthood still possessed an undue influence, which they were by no means content to restrict to spiritual affairs. Several of Frontenac's predecessors had had enough to do to maintain the civil authority against them. But Frontenac brooked no rival. He set himself in determined opposition to the clerical influence from the first. To the Jesuits and Sulpicians he was especially hostile, and to this day many of them regard him as an impious impostor. An impostor, however, he was not, for he was by no means [Pg 21]extravagant in his professions of orthodoxy. Religion, with him, was a mere sentiment, though, by mere force of custom, he continued to respect and practise the formal observances of the church throughout his life. The only priests that found any favour in his eyes were the Récollets, whom he befriended at first out of a mere spirit of opposition to the Bishop and the Jesuits, and afterwards, it may be believed, from a feeling of genuine kindness. These Récollets had originally been sent out to Canada to counteract the machinations of the rival order, and of course found no favour in the eyes of the Bishop and his adherents. The breach between them was widened by the patronage of Frontenac. The priestly method of exercising power by secret means was very distasteful to the frank and courtly soldier, who could not for the life of him understand why any man should dissemble his real opinions. He found that the priests abused the confessional, intermeddled with private family affairs with which they had no right to concern themselves, set wives against their husbands and children against their parents—"and all," says Frontenac, in a letter to Colbert, the king's famous minister—"and all, as they say, for the greater glory of God." He sent home constant complaints against the priesthood, and they, in turn, were equally assiduous in traducing him at headquarters. These two powerful influences were thus pitted against each other in the colony, and an energy that ought to have been exerted in promoting the common weal was largely expended in mutual opposition.

Frontenac was favourable to western exploration. He found at Quebec a young man who was very willing to promote any such schemes. This young man was no other than La Salle, whose life has been sketched in an earlier volume. "There was between them," says Mr. Parkman, "the sympathetic attraction of two bold and energetic spirits; and though Cavelier de la Salle had neither the irritable vanity of the Count, nor his Gallic vivacity of passion, he had in full measure the same unconquerable pride and hardy resolution. There were but two or three men in Canada who knew the western wilderness so well. He was full of schemes of ambition and of gain; and, from this moment, he and Frontenac seem to have formed an alliance, which ended only with the governor's recall." Frontenac's predecessor, Courcelle, had urged upon the king the expediency of building a fort on Lake Ontario, in order to hold the Iroquois in check, and intercept the trade which the tribes of the Upper Lakes had begun to carry on with the Dutch and English of New York. Thus, a stream of wealth would be turned into Canada, which would otherwise enrich her enemies. Here, to all appearance, was a great public good, and from the military point of view it was so in fact; but it was clear that the trade thus secured might be made to profit, not the colony at large, but those alone who had control of the fort, which would then become the instrument of a monopoly. This the governor understood; and without doubt he meant that the projected establishment should pay him tribute. How far he and La Salle were acting in concurrence at this time it is not easy to say; but Frontenac often took counsel of the explorer, who, on his part, saw in the design a possible first step towards the accomplishment of his own far-reaching schemes. La Salle was thoroughly familiar with the country along the shores of Lake Ontario, and convinced Frontenac that the most appropriate site for his projected fort was at the mouth of the River Cataraqui; and there, on the site where now stands the city of Kingston, the fort was built accordingly, during the month of July, 1673. Frontenac's patronage of La Salle continued throughout the former's tenure of the Governorship. He [Pg 22]also patronized other enthusiastic western travellers, and sent Marquette and Joliet to explore the regions of the Mississippi. Meantime his quarrels with the clergy were incessant, and the perpetual recriminations which were sent over to France were no slight cause of annoyance at court. The French king finally determined to send over an intendant to manage the details of the administration, and to report upon the merits of the perpetual disputes between the Governor and the clergy. The intendant arrived in the colony in due course, in the person of M. Duchesneau. This gentleman sided with the clerical party, and became the strenuous partisan of Bishop Laval. This brought down upon his head the fierce wrath of Frontenac. Into the bitter quarrels, charges and counter-charges, that ensued it is not necessary to enter. The strife of the rival factions grew fiercer and fiercer. Canes, sticks, and even drawn swords were imported into the quarrel. In February, 1682, both Frontenac and Duchesneau were recalled. La Barre succeeded as Governor, and Frontenac repaired to Paris, where he spent seven years, by which time La Barre, and his successor, Denonville, had contrived to bring the colony to the brink of ruin. In this contingency the king once more had recourse to Frontenac, who was at this time (1689) in his seventieth year. "I send you back to Canada," he is reported to have said, "where I am sure that you will serve me as well as you did before; and I ask nothing more of you." The Count accepted the responsibility, and bade a last farewell to France and his sovereign.

One of the principal drawbacks to the success of the colony of New France was the proximity of the Iroquois in the Province of New York, who made frequent incursions into Canada, and generally spread devastation in their track. It was understood at Quebec that these incursions were not only winked at by the authorities at Albany and New York, but were even in some instances incited by them. There were also perpetual troubles between the French and English colonies respecting the fur-trade. No sooner had Frontenac been reappointed as Governor than he conceived the design of invading and ravaging the British colonies in America, and thus removing the chief drawback to the prosperity of New France by laying waste the territory of her foes. He had no sooner set foot in Canada than his spirit began to infect the entire French population there, and for the first time for seven years some traces of energy were visible in the streets of Quebec and Montreal. The terrible massacre which had taken place at Lachine only a few months before was almost forgotten in the ardour of the approaching expedition against the British colonies. Three separate war parties were organized, and set out on their mission. The history of their subsequent proceedings is a terrible record of cruelty and bloodshed into which it is unnecessary to enter here. Various points in New England and New York were attacked almost simultaneously, and with success for the French arms. The British colonies became thoroughly aroused, and organized a counter expedition against Canada. A detachment under Colonel Winthrop of Connecticut advanced from Albany upon Montreal, and a naval armament under Sir William Phips menaced Quebec.

The expedition against Montreal under Winthrop was a failure, owing, in part, to the combined effects of famine and small-pox. Sir William Phips, on the 5th of October, (Old Style) 1690, anchored his fleet of thirty-five vessels a little below Quebec, and sent an envoy ashore with a summons to Frontenac to surrender. Sir William had delayed on his way up the St. Lawrence, and the French had had time to put the garrison in an efficient state of defence. When the envoy presented his summons to Frontenac in the Castle of St. Lewis, he was [Pg 23]grossly insulted by some of the officers, but was treated by the Governor himself with as much courtesy as the occasion called for. The summons to surrender was conceived in a most peremptory style, and could not fail to give serious offence to such a haughty aristocrat as Frontenac was. It demanded, in the name of William and Mary, King and Queen of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, a surrender of forts, castles and stores, as well as of the persons and estates of the Governor and his chief officials. It referred to the cruelties and barbarities which had been practised by the French and Indians against the colonists; and concluded by demanding a positive answer within an hour. When it had been translated aloud, Sir William's envoy took his watch from his pocket and handed it to the Governor. The latter calmly waved it aside, and delivered his memorable reply, which, stripped of the florid ornamentation with which it has been garnished by successive generations of translators, was as follows: "I will not keep you waiting so long. Tell your general that I do not recognize King William; and that the Prince of Orange, who so styles himself, is a usurper, who has violated the most sacred laws of blood in attempting to dethrone his father-in-law. I know no king of England but King James. Your general ought not to be surprised at the hostilities which he says that the French have carried on in the colony of Massachusetts; for, as the king my master has taken the king of England under his protection, and is about to replace him on his throne by force of arms, he might have expected that his Majesty would order me to make war on a people who have rebelled against their lawful prince." Then, turning with a smile to the officers about him: "Even if your general offered me conditions a little more gracious, and if I had a mind to accept them, does he suppose that these brave gentlemen would give their consent, and advise me to trust a man who broke his agreement with the governor of Port Royal, or a rebel who has failed in his duty to his king, and forgotten all the favours he had received from him, to follow a prince who pretends to be the liberator of England and the defender of the faith, and yet destroys the laws and privileges of the kingdom and overthrows its religion? The divine justice which your general invokes in his letter will not fail to punish such acts severely." The startled messenger asked for an answer in writing. "No," returned Frontenac, "I will answer your general only by the mouths of my cannon, that he may learn that a man like me is not to be summoned after this fashion. Let him do his best, and I will do mine." He was as good as his word. He opened a fire on the fleet. The upshot of the expedition was that Sir William was completely discomfited, and sailed off down the St. Lawrence to the sea, leaving his artillery, which had been disembarked near the mouth of the St. Charles, behind him. He lost nine of his vessels by rough weather on his way back to Boston. Frontenac's victory was commemorated by the erection of the little church, still standing in the Lower Town of Quebec, dedicated to Notre Dame de la Victoire.

The repulse of Phips and his fleet may be pronounced the culminating point in the career of the Count de Frontenac, although eight years more of vigorous life remained to him. Such vigour and energy in a man of his age has few parallels in history. In the summer of 1696, when he was in his seventy-sixth year, he led an army in person from Montreal into the heart of the Province of New York, and laid waste the country of the Onondagas and Oneidas. For this achievement his royal master sent him the cross of the Military Order of St. Louis. He had a due share of quarrels for the rest of his life with the clergy and with certain [Pg 24]of his officials, but he succeeded in restoring the fallen fortunes of France in North America. He paid the penalty of being a blood-horse, and ran till he dropped. In November, 1698, he was seized with a mortal illness, and sank very rapidly. He died with perfect calmness and composure, as became him, on the 28th of the month. He was buried in the Church of the Récollet Fathers. On the destruction of that church his bones were removed to the cathedral of Quebec, where they now repose. His heart, by his direction, was enclosed in a case of silver to his Countess. Tradition says that the lady refused to receive it, saying that she would not have a dead heart which had never been hers while living.

Of Frontenac's services to French Canada there can be no doubt. "His own acts and words," says Parkman, "best paint his character, and it is needless to enlarge upon it. What perhaps may be least forgiven him is the barbarity of the warfare that he waged, and the cruelties that he permitted. He had seen too many towns sacked to be much subject to the scruples of modern humanitarianism; yet he was no whit more ruthless than his times and his surroundings, and some of his contemporaries find fault with him for not allowing more Indian captives to be tortured. Many surpassed him in cruelty, none equalled him in capacity and vigour. When civilized enemies were once within his power, he treated them, according to their degree, with a chivalrous courtesy, or a generous kindness. If he was a hot and pertinacious foe, he was also a fast friend; and he excited love and hatred in about equal measure. His attitude towards public enemies was always proud and peremptory, yet his courage was guided by so clear a sagacity that he never was forced to recede from the position he had taken. Towards Indians, he was an admirable compound of sternness and conciliation. Of the immensity of his services to the colony there can be no doubt. He found it, under Denonville, in humiliation and terror; and he left it in honour, and almost in triumph."

The Countess survived her husband about nine years, and succeeded to the bulk of his property after his death. Her only child, the son whose birth was recorded in the early part of this sketch, was slain in battle, or, as some say, in a duel, at an early age.

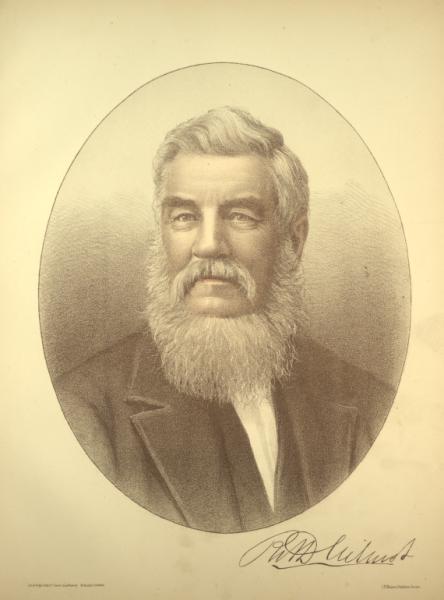

Mr. Burpee, one of the most distinguished members of the Liberal Party in the Province of New Brunswick, is descended from one of those old Huguenot families which were driven by persecution to emigrate from France during the latter part of the sixteenth century. The Burpee family sought refuge in England, and remained there for a generation or two, when, being debarred from the enjoyment of full religious freedom there, they once more tried the experiment of emigration. In 1622 or thereabouts they followed in the wake of those Pilgrim Fathers who, two years before, had crossed the billowy Atlantic, and founded a little colony upon the rugged coast of Massachusetts Bay. They settled in what is now the State of Massachusetts, and there they and their descendants remained for about 140 years. In 1763, immediately after the making of the Treaty of Paris, Jonathan Burpee, the head of the family, removed from Rowley, Massachusetts, to Maugerville, on the north shore of the St. John River, in what is now the Province of New Brunswick. His descendants have ever since resided in that Province, and many of them have held important public offices there.

The immediate ancestor of the subject of this sketch was Isaac Burpee, of Sheffield, N.B., who married Phœbe, daughter of Moses Coban. The present Isaac Burpee was the eldest son of this couple, and was born at Sheffield on the 28th of November, 1825. He received his education at the County Grammar School, and at an early age devoted himself to mercantile pursuits. In 1848, when he was in his twenty-third year, he removed from Sheffield to St. John, the commercial capital of the Province, and soon afterwards, in partnership with his younger brother Frederick, he entered into business as a hardware merchant, under the style of I. & F. Burpee. Both these young men displayed great aptitude for commercial life, and soon succeeded in building up a large and prosperous business connection. The senior partner acquired a very prominent position, not only as a merchant, but as a man of large views and public spirit. He took an interest in all questions affecting the welfare of the people, and was an active promoter of the establishment of manufactures to provide employment for the surplus population. He also took an active part in the movement which secured for Portland—a town contiguous to St. John, and in which his own residence is situated—an Act of incorporation, whereby the old system of irresponsible magistrates appointed for life was done away with, and whereby the management of municipal affairs was placed under the public control. He was elected Chairman of the first Town Council—an office identical with that of Mayor—and continued to hold that position for several successive years.

[Pg 26]On the 8th of March, 1855, he married Miss Henrietta Robertson, the youngest daughter of the late Mr. Thomas Robertson, a prominent hardware merchant of Sheffield, England. The business carried on by the firm of I. & F. Burpee continued to prosper, and after some years another brother, Mr. John P. C. Burpee, was admitted as a member. It was almost a matter of course that so influential and public-spirited a citizen as the senior partner should take a lively interest in political matters. He had been reared in Liberal principles, and had always adhered to the Reform side. He first appeared in the rôle of a candidate for Parliament at the general election of 1872, when he was returned to the House of Commons for the city and county of St. John, his colleague being Mr. A. L. Palmer, a leading member of the local Bar. Both the successful candidates, though of Liberal tendencies, expressed their intention of giving the Government of Sir John A. Macdonald an independent support, and this Mr. Burpee continued to do until the fall of that Government in the autumn of 1873, consequent on the Pacific Scandal disclosures. Since then Mr. Burpee has been a vigorous opponent of the Conservative Party, and has been able to indulge his Liberal prepossessions. Upon the formation of Mr. Mackenzie's Administration he accepted the portfolio of Minister of Customs, and upon presenting himself to his constituents for reëlection he was returned by acclamation. Upon accepting office he retired from his connection with the commercial firm, the success of which he had been mainly instrumental in establishing, deeming such a connection incompatible with his position as a member of the Cabinet.