* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: They Left the Back Door Open

Date of first publication: 1944

Author: Lionel Shapiro (1908-1958)

Date first posted: Sep. 29, 2017

Date last updated: Sep. 29, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170933

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Copyright, Canada, 1944, by

THE RYERSON PRESS, TORONTO

All rights reserved. No part of this

book may be reproduced in any

form, by mimeograph or any other

means (except by reviewers for the

public press), without permission

in writing from the publishers.

Published October, 1944

PRINTED AND BOUND IN CANADA

BY THE RYERSON PRESS, TORONTO

IN MEMORY OF SANDY MORRISON

It is not my wish to play a dedication piece on the heart-strings of my friends Bill and Happy Morrison. Their only son, Pilot Officer Sandy Morrison, R.C.A.F., was flying a Hurricane in the March skies over Burma when he was killed in combat, and I would not parade their freshly tear-stained memories of him if this were not to high purpose.

This is the stage of the war when we are exhilarated by our superior and still growing resources and by the vision of victory. We think less about individuals and more about armies; less about pilots, more about air power. It is inevitable. Four years of war and death has blunted the sharp edge of concern we felt when we suffered our first casualties. We have bitterly outgrown the sensitive feel for tragedy we developed during twenty-five years of peace.

But we must strive to recapture it; we must make certain that four or more years of war does not leave us psychologically crippled—else we will have lost a proper regard for peace.

The moment war becomes impersonal to us, and our glory in victory more fervent than our grief for the fallen—at that moment we will have established that war is the natural bent of mankind.

It is in elaboration of this point that I dedicate this book to the memory of Sandy Morrison, and for this purpose that I stir, perhaps cruelly, the settled grief of his parents Bill and Happy Morrison.

Not many years ago Bill Morrison was my first editor. On the early trick Sunday afternoons Bill sometimes brought along his boy Sandy. He was a lad in knee pants, under ten, and his crop of sandy hair curled at the ends, much to his disgust because having been brought up as the baby brother in a family of sisters he had a healthy aversion to anything pretty.

It was not long before I moved away on assignment as a roving reporter. But I did not lose track of the Morrisons. On my visits home two or three times a year I always dropped in to see Bill and Happy. Sandy was in high school now, trying hard to lower his voice, playing football and hockey with a skimpy little frame that didn’t seem to grow high or wide.

The last time I saw him at home he had reached the gawky age between boyhood and youth, still trying to make his voice sound manly, still abashed by the fate that made him a baby boy in a household of girls. At sixteen a fellow wants to grow up quickly.

“This generation has a rendezvous with destiny.”

I heard President Roosevelt utter the words during a 1936 campaign speech. A fine sentence, I thought; it thrilled you before you could break down its significance.

Three years later, on a misty Sunday morning in New York, I heard Neville Chamberlain’s dull voice come over the radio. “We are at war with Germany . . . we will be fighting evil things . . .”

Both events came to my mind on another Sunday—in London, 1941. The reception clerk at the Savoy had phoned to say, “Sergeant-pilot Morrison is here to see you”—and I stood in the hall and watched Sandy limp toward me with the aid of two canes. His left foot was in a cast, the result of a crack-up.

He stopped when he saw me, waved one of his canes, grinned boyishly. Then he hobbled forward eagerly. The ends of his sandy hair curled around his side cap.

“Sergeant-pilot Morrison.” I mumbled the words to myself. It didn’t seem real that Sandy should be a veteran of air battles. He was a boy—nineteen. At home he would be reprimanded for staying out past midnight. His sisters would make him blush furiously by mentioning he had been seen walking a girl home and swinging her hand along with his.

“This generation has a rendezvous with destiny,” I recalled. “We will be fighting evil things . . .”

This generation was Sandy!

He hadn’t changed at all. The young are blessed that way. War to them is a wonderful adventure.

Yet Sandy was glad to see someone and something from home. I gave him the chocolates his mother had put in my baggage. He asked eagerly about home, his boyish voice still quavering in its struggle to reach down to mannish levels. He shrugged off his adventures in the sky.

“There’s nothing much to talk about,” he said. “Tell them not to worry. A fellow can’t get hurt if he knows how to handle his kite . . .”

Sandy talked a long time in his diffident, gawky way. War or no war, he had not yet grown up. He was slight and skinny, and he still had the bashful bravado of a boy brought up in a household of girls.

I carried his box of chocolates to the door for him, helped him into a taxi. He waved his canes and grinned as the cab chugged away.

The Middle East and India. The King’s commission. And in the no-man’s-land of a Burmese wilderness a British patrol found Sandy lying close to the plane in which he had fought and fallen.

Now the war goes our way. We are going to win. Victory will be glorious. There will be peace.

What kind of peace? It depends on those who survive the victory. If they remember the Sandy Morrisons of this war vividly enough, there will be no peace as we have known peace. There will be short shrift and hard justice for those who foment hate and caress power. There will be righteous anger and eternal vigilance. We will be fighting evil things always—always.

Otherwise Sandy Morrison is doomed to battle forever. And death, not life, will take the blush of youth from his cheeks.

This is intended to be a book for the United Nations. In it I have discussed the campaigns conducted by British, American and Canadian troops in Sicily and Italy, and I have tried to handle my material with true Allied realism; that is, with frankness for all no less than pride in all. My motivation has been the ideal of full and unselfish co-operation between our forces fighting in the West to high purpose.

Because I am a Canadian, I can do this perhaps with an easier manner than my British or American colleagues. Canada is now a crossroads of the world; it has always been, as Mr. Churchill once put it, the linchpin binding together the two great English-speaking powers. We in Canada have merged the philosophies and inherited some of the qualities of both nations; happily, we have developed the prejudices of neither. The Canadian is at once a North American and a fervent citizen of the British Commonwealth.

My own experience has extended this pattern. After completing my schooling and basic newspaper training in Canada, I spent seven years as a correspondent in the United States, including two years in the White House press room. This was followed by a year in Britain; a campaign with the Eighth Army; and finally accreditation to Lieut.-General Mark Wayne Clark’s headquarters of the Fifth Army.

The reader will note that I have written only of what I have seen, and something of what I felt as an eyewitness. This has necessarily made for certain glaring omissions. For instance, because I campaigned with the Eighth Army in Sicily, I have neglected almost completely the role of Lieut.-General Patton and his Seventh United States Army. Similarly, my description of fighting on the Italian mainland is devoted principally to the Salerno operation with hardly a mention of the Eighth Army’s important function. In my consideration of the American soldier’s attitude toward war, I have based my conclusions on what I saw of him in the Mediterranean theatre. His attitude in the Far Pacific may be entirely different. If I have overlooked Russia, it is because my war experience has not brought me into contact with our magnificent ally. In other words, this book devotes itself to what I have actually seen.

I should like to record my thanks to The Montreal Gazette, my employer during the Mediterranean campaign, and to the North American Newspaper Alliance and MacLean’s Magazine, my current employers. Despatches to these offices have been used as background material for this book. I must include a note of appreciation for the goodwill of Mr. Alfred Lunt and Miss Lynn Fontanne. They have occupied adjoining rooms to mine in the Savoy Hotel these last few weeks and their forbearance has been remarkable. I am happy to note that the endless clatter of my typewriter, which certainly must have imposed upon their leisure, has not interfered with their magnificent success at the Aldwych Theatre.

Lionel S. B. Shapiro.

London, February 23, 1944.

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| FOREWORD | ix | |

| I. | SUMMONS TO A BATTLEFIELD | 1 |

| II. | SPANISH INTERLUDE | 17 |

| III. | WITH MONTGOMERY IN SICILY | 42 |

| IV. | FACE TO FACE WITH FASCISM | 72 |

| V. | THE ALLIED COMMANDERS | 85 |

| VI. | PEACE COMES TO SICILY | 99 |

| VII. | DESTINATION—SALERNO BAY | 111 |

| VIII. | THE ASSAULT | 120 |

| IX. | DRAMA UNDER A HAZY MOON | 135 |

| X. | THE CRISIS | 145 |

| XI. | VICTORY BEFORE NAPLES | 160 |

| XII. | MEN IN BATTLE | 170 |

| XIII. | OBITUARY UTTERED BY A PRINCE | 182 |

List of Illustrations

In the dark days before Alamein changed the shape of the war, the wounded didn’t cry. Neither did Quentin Reynolds. War correspondents foregathered from all parts of the world, mostly from America, in London’s Savoy Hotel and there we waited with excessive patience for the second front, murmuring hardly a complaint except to growl, “Jeez, Gus, where are those two doubles I ordered ten minutes ago?” During the day we wrote brave stories, dope stories and expense accounts; and on the midnight we transformed the austere resident’s lounge of the Savoy into a happy haranguerie incorporating the best features of Bleeck’s 41st Street and the powder room of the Embassy Club.

The performance was on at the stroke of midnight when Gus, the night waiter, arrived in the lounge with two pitchers of iced water and his order pad. The programme thereafter was anybody’s guess. Sometimes it was utterly unpredictable. One never knew when Larry Rue (Chicago Tribune) would stop harassing President Roosevelt and go into a practical demonstration of his baseball prowess as one-half of the battery of Rue and Fugelberg. Or when Jamie MacDonald (New York Times) might come in from a bomber station with a breathless recounting of his trip over Berlin a few hours before.

Sometimes Frank Owen and Michael Foot, brilliant editors whose radical minds were harnessed by Lord Beaverbrook to his capitalist press, chanted the Internationale on the urging of several bottles of champagne. This hardly disturbed Hector Bolitho; certainly it did not prevent him from reading benignly to his assembled audience the autobiographical passage which had come to him in bed that very afternoon. Negley Farson might arrive, later, and glance around the room with evil intensity, looking like any Barrymore playing Mephistopheles badly.

Frequently the night manager appeared at the door, then disappeared, his blanched face tweaking with helpless anguish. No wonder. He could remember the day when the only sound heard in this distinguished room was the scratching of a pen at the writing desk and perhaps the heavy breathing of Lord Chislebeak as he addressed himself to his eight-thirty sherry.

Now the world was in chaos and this was the Savoy’s Calvary. Only an Allied offensive in the west could remove the war correspondents from this rollicking halfway house, thus restoring to the lounge the charm of unemployed luxury which is the hallmark of the hotel distingué. I think that the night manager was one with Joseph Stalin in heartfelt passion for a second front.

As the months of 1942 rolled by, Messrs. Roosevelt and Churchill and their combined chiefs of staff conspired to solve the Savoy’s problem.

The Alamein offensive took some of the correspondents. The North African assault took more. The mardi gras spirit of the lounge after midnight was withering.

Then one day early in June, 1943, the telephone tinkled in my room. That ended my beachcombing on expense account.

In the next five months I was to know the stench of Sicily and the terror of Salerno; I was to witness the last inglorious days of Italian Fascism and to see lying off the hubcaps of a jeep the ultimate degradation to which Fascism can bring a civilized nation.

During the third week in May, 1942, the battle for Africa ended. The Allied world reacted joyously, but no more joyously than the Canadian First Division. These original Canadian volunteers had been in Britain three years and five months seeking, hoping for, finally praying for a battlefield. Their record was one of frustration. In April, 1940, the division was ordered to recapture Trondheim while there was still a chance to break the German hold on Norway. It boarded ship at a Scottish port, but before the convoy could get under way the operation was cancelled. Early in the following June, the division was once again moved to a British port. This time the forlorn cause was France, and once more the order was rescinded. Dunkerque was too close to its tragic climax. France was gone and a single division could not save it.

Three years and five months! A long time for volunteer soldiers to wait three thousand miles from home. Too long for men who had rushed to recruiting offices in September, 1939, in the first flush of a desire to fight Nazi Germany. Too long, much too long, to spend in the bleak encampments of England. Youths of twenty had become twenty-four; many had married apple-cheeked Sussex girls, reared families with multiple offsprings.

With bitter humour they cracked: The First Division is the only formation in the history of war in which the birthrate is higher than the deathrate.

Now Africa was conquered. And they were engaged in assault exercises and mountain training. The next battlefield must be theirs. Surely the vigil was ended!

It was. During the first week in June tanks and heavy equipment of the division rolled to west British ports for loading on ships.

On Saturday morning, June 12, at eleven-thirty o’clock, my telephone tinkled. The exact time is unimportant except to me. The bell was summoning me to an experience which was to affect my life so drastically as to be almost fatal.

“Hello, Lionel. This is Eric Gibbs. There’s a parcel just arrived for you. Would you come down and pick it up?”

“Thank you. I’ll be down in twenty minutes.”

My hand clutched the telephone headset long seconds after Gibbs rang off. This was the summons. I knew it. There was the collusion of rumour and premonition. Besides which, Major Gibbs, second in command of the Public Relations Office, Canadian Military Headquarters, was not in the habit of informing me of the arrival of parcels from home.

Fifteen minutes later I was striding down the Strand, across Trafalgar Square where the band of the Scots Guards was playing a noon-hour concert, into the drab building on Cockspur Street.

I walked directly into the office of Lieut.-Colonel Abel, Chief Public Relations officer. Major Gibbs followed me in, closed the door behind him. I heard what I expected to hear.

“You are going on operations,” Abel began. He paused to fill his pipe, an old habit of his when he wanted time to think between sentences. “We don’t know what kind of operations. They may be only manœuvres. Who knows? Anyway, you leave Monday night. Better take all your equipment with you. And check out of the hotel.”

Gibbs was a little more specific. “Be at the station at eight o’clock Monday night. I’ll meet you there and tell you where you go. And, for God’s sake, don’t tell anybody about this. You’re just going away for a few days, see? A hell of a lot of security depends on you—to say nothing of your own skin.”

The Scots Guards band was still playing when I came out on Trafalgar Square. A June sun glinted on polished brass instruments pumping out a Friml medley. I think it was the “Rose Marie” music. I could not be sure because I stood in a small vacuum of my own making and I was the star of my own little melodrama.

Here were all these people standing in the Square, listening to music, probably on their way home. How drab! I was on the threshold of new adventures, probably thrilling ones. I felt the tingle of superior power. I knew something these people didn’t know. When they next read big black headlines in their newspapers, I would be in the midst of the story they read. I might even write that story.

I hardly noticed that the band concert was finished. I moved out of the Square with the crowd, still absorbed with my own exhilaration. There was a note of mystery to add to the symphony swirling within me. I didn’t know where we were going. Of course I suspected the Mediterranean. But one never knew.

In the Savoy I met Hannen Swaffer, his bearing lending majesty to a figure designed for nothing better than a starved vaudevillian.

“How are you, m’boy?” he said. “Anything new?”

Nothing was new, I told Swaff. Same old routine of waiting for something to break—oh, yes, and I was going out of town on Monday for a swing around Canadian camps. This, with an air of bored nonchalance. (Which, as I learned later, didn’t fool Swaff!)

Thus I passed the week-end with my secret wrapped up excitingly within me like a Christmas parcel almost coming undone in the arms of a small boy. Here were bursting moments and I was unable to share them with my friends. I could only sift the thoughts that crossed my mind, while I made last-minute preparations for life on the march.

If these are desperate days through which to live, we are offered the crowning compensation of a sense of history. It is real compensation for those who are vivid enough (and fortunate enough) to collect it. In order to do so, one must be at once selfless and the extreme introvert; one must remove oneself from his generation and view this unique and magnificent struggle from the heights of historic perception, and at the same time embrace eagerly the circumstance of having been born to this generation and of having contributed to the shortcomings and emotions which precipitated this climactic drama. We are both spectators and players—every last one of us—and we must be conscious of both roles. What a desolate circumstance it would be if schoolchildren a hundred years from now should know better than we the flavour and the breathlessness of this time.

There are some to whom this war is nothing but blood, tears, toil and sweat. Yet the man who offered only these to Britain in 1940 could, from the vantage point of history, see behind and beyond the shadowed valley. He was both player and spectator in that delicate balance which produces courage for living and hope for life.

I am endowed with no such Churchillian perception. Instead I have a modest substitute, a sort of hammy awareness that I am witnessing a chapter of mankind’s story which will be the wonder of those who come after. I will have lived and felt and perhaps been crushed by events a description of which in cold type will tingle the jowls of the reader of tomorrow.

What would one give to have lived through Trafalgar and Waterloo? Or to have marched with General Washington, knowing that the rumble of drums was summoning to life a new and wondrous nation?

These events are flicks on the face of history compared with the grand upheaval through which we are living. Ours is the generation accursed with the heartbreak of violent change; yet—who would remove himself to the maddening frustration of Victorian existence? The innocent died then, cruelly, wantonly, perhaps in number comparable with today; they were struck down by the diseases of poverty and ignorance. They did not recognize their tormentors, nor was their gruesome passing more than briefly noted by the fine little world of royal courts and middle-class carriages.

Today’s ordeal thrums with the overtones of spectacle and poignance and truth. We know at least why we die: and because of this perhaps we may learn how to live. We feel a sullen purpose in this crimson and confusing pattern. (And suddenly, one is chilled. Has this not been said before—in finer terms, by great men, in other wars?)

These considerations contain a degree of consolation and courage, and I put them in a last letter to my mother, hoping my sudden ascent into intellectual acrobatics would serve to inform her of my departure from London to a fighting zone. Then I sent my last expense account to my newspaper, which told my editor nothing because it was no departure from the regular routine.

My zeal for security knew no bounds, proof of which I submit in the fact that I failed to cancel an after-theatre dinner engagement with a mannequin. Our dinner was arranged for a Tuesday night; I left London on the Monday, thus sacrificing a fine and promising amour in the interests of secrecy. In fact, on the Sunday I walked the streets of London rather than remain in the hotel and risk becoming involved in heated discussions on military operations. I was afraid my bursting secret might split at the seams.

Monday, the 14th, was filled with the bustle of departure. Troubles, I found, are about the only thing you can pack in a kitbag. Selecting only essential needs for an extended journey, I found myself buying an extra duffle bag, then salvaging a zipper bag from a previous clipper journey, finally dumping a lot of extra kit in my bedding roll. I struggled into the station looking like John Steinbeck’s Mrs. Joad on the move.

The next morning I detrained at a little town and was driven to the concentration area of a Canadian Army Tank Brigade.

Headquarters was situated in an old castle of Hearstian proportions. It was complete with moat, drawbridge and ghost. Inside it was less livable than a second-class stable. The plumbing had been modernized, I guessed, in anticipation of the last visit of Henry VIII, and the chill was so penetrating I had to keep turning in front of the fireplace, as though impaled on a perpendicular spit, in order to keep myself uniformly warm.

The Brigade had been concentrated in the area for a month. Some of its units with tanks had already gone forward to be loaded on LST’s (landing ship tank). This is the flat-bottomed type designed by Andrew Higgins of New Orleans for amphibious operations. It is capable of long sea voyages, and when it runs up on a beach, its square prow opens like a drawbridge so that the tanks can roll off on land.

The last of the tanks went forward while I was still in the castle. I was left there with the brigadier and his staff, and certain infantry, supply and workshop units who were scheduled to travel to Sicily on the headquarters ship, the last to be loaded.

For eleven days, from June 15 to the 26, we remained in the castle. Waiting became the principal discomfort, followed closely by the damp of the castle and the muscular rats which filled the nights with the clamour of their athletics.

Secrecy was rigidly maintained even in the lonely castle. Although most staff officers knew details of the operational plan, no hint was dropped through long nights of conversation, card-playing and modest drinking that Sicily was our destination. Indeed, I began to doubt that we were to assault any part of Italian soil. I pondered the possibilities of Corsica and Salonika.

In order that no hint should be dropped to near-by villagers that operations were pending, I was stripped of my war correspondent’s insignia and given three pips denoting a captaincy. Thus I was able to drive to a near-by town one night to see a motion picture. The feature was one currently running in London—“China,” starring Loretta Young and Alan Ladd.

Drama is a counterfeit thing. It has to be dressed up to be appreciated. Here was a piece of Hollywood fiction about a handsome American civilian in China advancing to attack a Japanese concentration and it had my heart leaping about my throat. The tension within me was immense as the hero moved stealthily toward the Japanese positions. It did not occur to me until I was walking out of the theatre that I was on the threshold of an adventure certainly as daring, perhaps more thrilling.

Back at the mess, an officer paused in his card-playing to tell me of an accident that evening. A tank was proceeding to the embarkation point; its commander was sitting halfway out of the top turret. As the tank turned a corner, its 75mm. gun struck a signpost. The gun swung round on its turret and decapitated the officer cleanly as though by guillotine.

“Tidying up the tank was a messy job,” grumbled the officer as he returned to his card-playing.

This was my first acquaintance with sudden death. There was no reaction within the room, hardly any within me. The movies do this sort of thing much better.

The next morning the brigadier invited me to accompany him on a last inspection of units before embarkation.

“You’ll see regiments out there, young man,” he said to me at breakfast. “I’m proud of them. They’re keen as mustard. They’ve been here two years waiting to go into action, but we in the tanks have had no morale problem. We’ve had our equipment headaches—but that’s another story. Our morale has always been first class.”

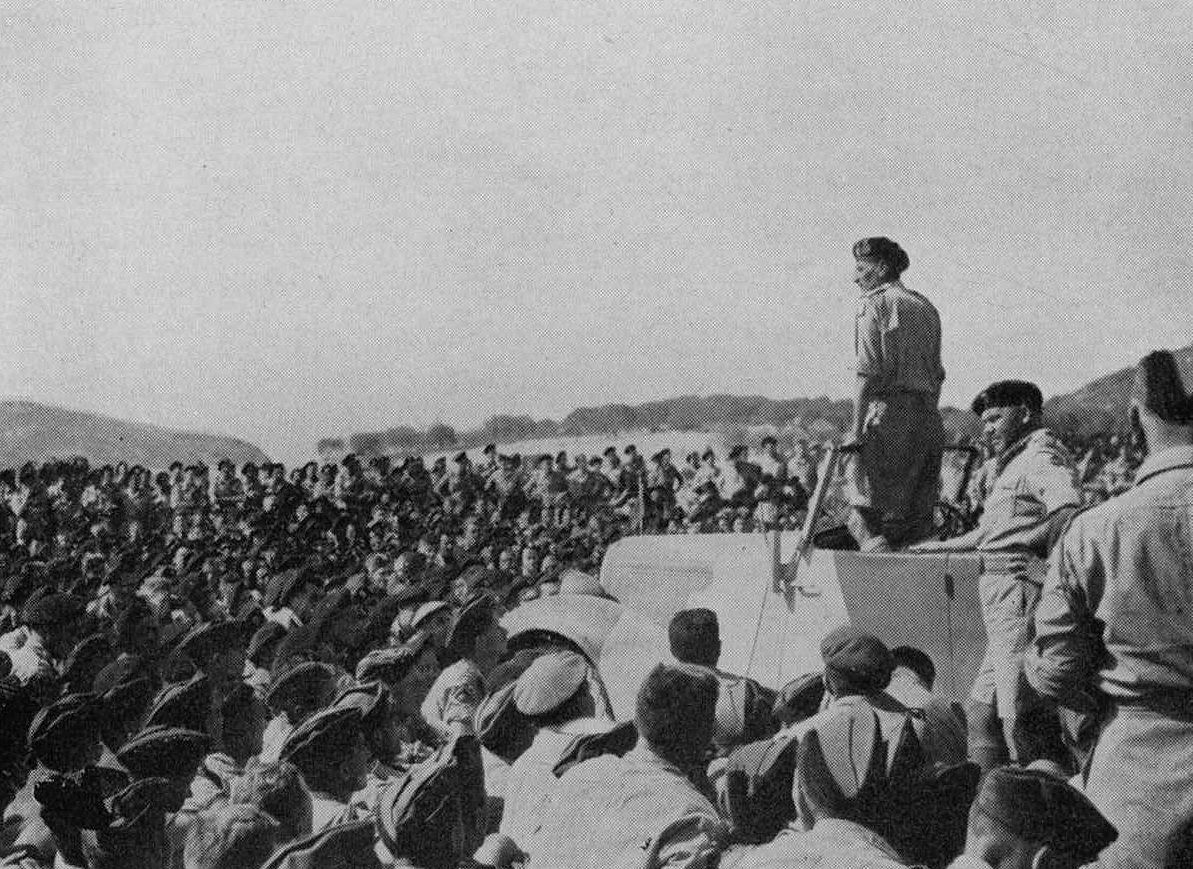

Our cavalcade rumbled over the cobblestones of a town hoary with the architectural cobwebs of history, squirmed through a country road. Emerging from a clump of forest we came into full view of a regiment lined up on the gradual incline of a hill. The men were in full battle kit. A general salute was ordered as the brigadier strode toward the officer commanding the regiment.

The brigadier examined each man from head to foot, prodded pieces of equipment, tugged at belts and buckles. Then he moved back to a position facing the regiment.

“Men,” he began, his deep voice booming over the parade-ground, “you have been singularly honoured and privileged to form part of the first armoured formation in the history of Canada to move into active operations against the enemy.”

This was the first official word given to the men that they were about to go into action on the battlefield. Smiles broke on some faces; on most there was no visible reaction.

“You have everything,” the brigadier went on, “except actual battle experience. That, I am confident, you will learn quickly and effectively. But I want to sound a note of caution. Feel your way at first. Do not move in headlong no matter how great the temptation. Be cautious. Be careful at first. In short, make haste slowly.

“I wish the best of luck to each and every one of you. May God see fit to give His blessing to your efforts. Thank you.”

I stood beside the brigadier at the march-past and I watched for reactions in the faces of these youngsters who three years ago were clerks and farmers and shopkeepers in Canada. I was disappointed. There was none.

Back at the mess I mentioned this observation to the padre, a young Roman Catholic priest from a small Ontario town.

“I find them no different now than they were before they heard the news,” he said. “My services are no better attended. I suppose they’re no longer men, as we know men. They’re good soldiers. A pity, isn’t it?”

Life at the castle had become almost unbearably dull. The whole of the Brigade, except the headquarters squad, had already gone forward to transports; the clusters of Nissen huts surrounding the castle were deserted, the roar and clamour of tanks uncomfortably absent. Nothing looks so enthusiastically lived in as a Nissen village, and nothing so bare and desolate as one recently vacated.

Then on Saturday, June 26, it happened.

“We move tonight.”

Our card-playing in late afternoon was broken up by this quietly spoken remark. It was uttered by the brigade major as he entered the officers’ mess.

“A vehicle will pick up your bedrolls at midnight,” he added. “You will be ready to move an hour later. Dress order for the journey will be full webbing, big and small pack, and tin hat.”

Cards were tossed on the table. We raced to our quarters to get our gear in travelling shape. Boredom was routed as the halls of the castle echoed with scuffling and laughing and shouting. The two officers whose room I shared rolled wrestling on the floor out of sheer exhilaration.

Our last packs were being neatly crammed when the door of our room was flung open and the quartermaster sergeant staggered in, sagging under the weight of a towering armful of equipment. He dropped it on the floor.

“What’s that?” we shouted almost in unison.

“Tropical kit,” said the sergeant—and he walked out.

So it was. Two khaki drill shirts, two shorts, two long trousers for each man. Also a mosquito net, tent poles, sun goggles, knee length socks and short puttees. We groaned as we proceeded to rearrange our packing to include the new equipment.

“Well,” one of my roommates mumbled, “that eliminates Murmansk.”

Dusk lingered long on this June night. It was not until very late that darkness descended upon the turrets of the castle. A convoy of vehicles moved out of the courtyard, edged through the deserted Nissen village and, reaching the highway, leaped through the darkness toward the railway station of a near-by town.

Some three hundred men, last of the headquarters squadron, were lined up on the station platform beside the blacked-out train. Sergeants called the roll, their voices echoing over the sleeping town below the station platform. It was a moonless night and the faint glint of starlight played on the helmets of the troops.

On orders, the officers moved up the platform to where the first coaches awaited. The men remained, standing easy, along the lower length of the train. The wind was sharp, the night dark, and we waited. These were long minutes. Webbing supporting big and small packs strained at my shoulders. The journey into battle awaited the order of the officer commanding.

I glanced at the luminous dial of my wrist watch. It showed two-fifteen a.m. In New York it was eight-fifteen on a Saturday night. People at home were at dinner. Or on their way downtown to the movies, their girl friends clinging to their arms. The cocktail bars were filled with clinking and conversation. I thought of the Stork Club and my friends gathering at the big table in the far corner of the room; of the theatre orchestras warming up in the pit before the curtain’s rise. I thought of California and the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel. It was four-fifteen in the afternoon there, probably bright sunshine and drinks in tall frosted glasses. I thought of these things with unashamed sentimentality, but I did not long for them. My place in the drama of our time was too precious. I was privileged, I thought. . . .

Down the line the waiting men began to sing, with exaggerated pathos, “Sweet Adeline.”

The tune was cut short by a crisp order—“Board train! The first four compartments are reserved for officers. Quickly, men, quickly!”

We were off to the wars.

A few hours later the screech of brakes disturbed the easy rhythm of wheels on rails and broke the doze into which I had fallen. Someone lifted the black-out shade and the compartment was filled with early morning light. We stretched ourselves, carefully because there was a scarcity of space. Six of us were in the compartment and we lay in a bower of packs, big and small, haversacks, binoculars, coats, revolvers and tommy-guns.

The train was coming to a stop.

Doors were flung open by military police and Royal Marines. Wearily we donned the webbing and the packs. On the platform the men were lined up. In a few moments we marched a short distance to a tender.

In the bay a flotilla of troop transports floated at anchor. Handsome ships they were, some easily recognizable despite their drab colouring. Not far away were ships of the Royal Navy, destroyers, cruisers and aircraft-carriers. Our tender steamed into deep water, passed dozens of ships, and finally coddled by the side of a transport I recognized as being formerly in the Atlantic run. We scrambled aboard.

The steward of the stateroom I shared with two other officers helped us with our baggage. “How long a voyage have we in prospect?” I asked, fishing gingerly for information.

“That all depends where we’re going, sir,” he replied. “Personally, I have no idea.”

We weighed anchor toward dusk on a placid day late in June and sailed under the magnificent patronage of the biggest and reddest sun I have ever seen. Through the protective boom our convoy of ocean liners moved in single file. These were all fast ships. The slower LST’s carrying our tanks sailed before us.

Darkness closed in while we were still in sheltered waters, and we retired to a carefree sleep. The next morning we were in open sea. The vista from the boat deck was both proud and terrifying. Our group of ocean liners ploughed through a summer sea which rippled no more ardently than the average lake. Etched against the horizon in every direction steamed British and American destroyers, the legs, eyes and arms of this solid body of great ships. Closer in were bigger warships of the Royal Navy, their glinting guns making communion with the morning sky. And overhead aircraft of Coastal Command circled around, giving us a feeling of easy confidence.

As I looked upon this magnificent panorama I knew at once the supreme purpose of sea power in a world war. In these ships a fully equipped army was sailing safely and confidently on a split-minute schedule toward a point of our own choosing. We were circling the Fortress Europe, reserving the oceans, greatest of all highways, for our exclusive use and denying it to the enemy. Our ships cut serenely across a painted ocean. In the distance the destroyers raced proud and impudent like thoroughbred terriers. This was our highway. So long as we could use it and the enemy could not, we might fall upon him at any point of his long coastline. We could wield the initiative and strangle him with it.

The ship’s permanent regimental sergeant-major, a weatherbeaten veteran of 1914, stood beside me as I scanned the scene through binoculars.

“You’ve got to ’and it to the Navy, sir,” he grunted. “I’ve been on transports for three years now. Travelled most everywhere. Around the Cape, Suez, Malta, India, Alex—yes, and Greece. The Navy took me there and brought me back. You’ve got to ’and it to ’em. They do the job every time. The army ’asn’t been so ’andy at times. But the Navy they never fails. Them blokes is good.”

Good they are. I was destined to learn just how good. Before my odyssey in the Mediterranean was ended, they were to save my life and tens of thousands of others, and to turn this war’s threatening Gallipoli into the triumph of Salerno.

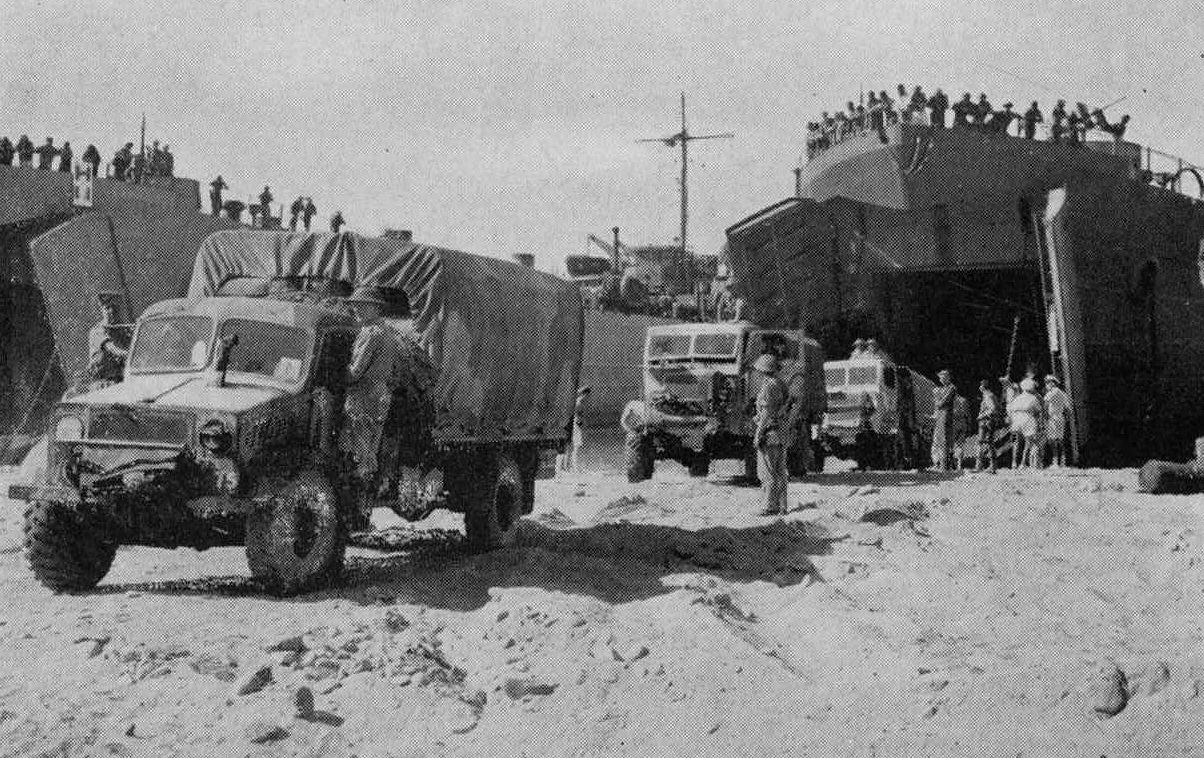

Above: “I knew at once the supreme purpose of sea power in a world war.” Part of the assault convoy sailing to Sicily.

Above: A demonstration of the firepower of American Sherman tanks, used by the Eighth Army in Sicily. A single shot from a Sherman at point-blank range severed the turret from this German Mark IV.

This is the story of a man who went out and did something about freedom and justice and decency. He did not rest his foot on a rail and pound the words into a mahogany bar until his fist shook the tumblers all along the line. Nor did he decry Fascism from a platform and rest content that he had done his duty by arousing an audience of liberals and intellectuals. He did not write brave and biting articles in the press to prod the conscience of mankind. He clenched his bare young hands and moved in wrath toward the enemies of freedom and justice and decency.

A simple fellow, to be sure. I doubt that he knew the meaning of Fascism; to him it was probably a word in a newspaper headline. Certainly he never listened to a speech in which a politician intoned eloquently the glories of democracy. He was not well educated. In his intellectual gawkishness he only knew right from wrong, and his awareness of wrong automatically set him in motion toward correcting what seemed to him a patently ridiculous situation. His utter simplicity was his great strength. The mental acrobatics which ponder ways and means and compromise were grossly lacking in him.

But his is a story of our world in the middle nineteen-thirties. In it are caught up the frustration, deceit and cowardice of that time, the hypnosis which gripped us as we watched Fascism coil for the kill and also the Quixotic courage of our awakening. It is a story both brave and anguished; full of the greatness of small men and the smallness of great nations.

I came by the story long before we moved into battle. It was related to me on the deck of our troopship bound for Sicily.

On a dark and moonless night in July our convoy passed through the Straits of Gibraltar. Proud and triumphant, their guns raised high toward the dark skies as though in celebration, two destroyers of our escort led us into the narrow channel where the Mediterranean makes confluence with the Atlantic.

From the jet-black deck of our troopship I scanned the south shore. Less than a mile to our starboard the lights of Tangier lay scattered beyond the rocky coast. They were the first night lights many of us had seen for more than a year; we were transfixed by them. Across the Straits on the European side, a few lights flickered in the hills. This was Algeciras.

On the dark water between, the bulky shadows of our blacked-out ships moved slowly through the narrow channel. These are tricky waters and our huge vessels moved dangerously close one upon the other. It seemed our propellers were barely turning. Like masked creatures we crept stealthily into the Mediterranean, passing the lights of the Spanish mainland with a breathless quiet and almost brushing the base of Gibraltar without a gesture of recognition. Then into the open waters of the inland sea.

The next morning was sunswept and dazzling. After the murky waters of the Atlantic the Mediterranean appeared a deep and decorative blue. Our convoy resumed operational formation and we sailed—gaily it seemed—at full speed. The mountain peaks off the Spanish coast could be seen rising above the ground haze. I scanned these from the boat deck, and I wondered how many German agents stood on those peaks scanning us, counting our ships, examining through powerful binoculars the particulars of our convoy and reporting back to Berlin.

Leaning on the rail beside me was Captain John Donaldson of the Brigade staff. He was also examining the hills of Spain with a curious intensity. Captain Donaldson was a typical Canadian volunteer—tall, lean of body and broad of shoulder, handsome in a healthy way. I did not know much about him except that he came from a town near Regina and before joining the army in 1940 he was an engineer working for the Saskatchewan provincial government.

“That’s where it started, John,” I said. “Beyond those hills. I imagine if we had beaten Fascism there seven years ago, we wouldn’t be going to Italy now. At least not to fight.”

John was silent a long time. The hills seemed to hypnotize him. He blinked in the morning sun and continued to examine the distant peaks.

“I’ve got a score to settle,” he said, “beyond those hills. I had a brother there. He fought for the Loyalists.”

I was surprised. Not because a Canadian should have fought with the Loyalists—there were hundreds in the Mackenzie-Papineau battalion—but because one of them should have been John’s brother. It was a far cry from a western Canadian homestead to a Spanish battlefront. And John did not strike me as a militant liberal. He was a typical young Canadian, rather comfortable and content, inclined to be cold toward radical movements.

We leaned on the rail and watched the Spanish hills recede into the haze as our convoy moved deeper into the Mediterranean. And quietly, bitterly, John related the story.

It started in 1919 when hearty, thick-set George Donaldson returned from the Great War to his working-class home in the suburbs of Glasgow. He had left home as a private in 1914, fought for four years in France, and returned home as a private. That was typical of George Donaldson. He had neither ambition nor airs. He was a Scottish working man—a stoker by trade—and it did not surprise his impoverished wife that George, having fought through all the campaigns of the western front, should not have collected so much as a single stripe on his sleeve.

Mrs. Donaldson wouldn’t have minded—although keeping a roof over the heads of her three children and herself was no easy matter on a private’s allowance—if George had come back the same, sound, stolid man he went away. He was not. A hacking cough convulsed his thick frame and the strength developed in a lifetime of hard labour was no longer within him. Mustard gas and the damp of the Flanders winters had robbed him of the cheerful vigour which once enabled him to earn rent and food money tending the power furnace in the dungeon of a Glasgow factory.

George went back to work. But Mrs. Donaldson knew it could not be for long. Hers was a gamble with time, a race between George’s failing strength and the upbringing of her three children. She knew she must lose. The children were still under ten. And although George gave the impression of cheerfulness when he came home each night, she knew with a sure instinct that the time had come for the Donaldson family to make decisions. She could no more watch George die slowly in the stoke-hole of a factory than she relished the prospect of her three children growing up in the grey sadness of a Glasgow slum. She knew there must be somewhere a brighter place to live and a better prospect for her children.

So it came to pass that George, his wife and their three children sailed one day out of the mists of the Clyde. Their destination was Canada and the windswept spaces of the west, their journey aided by the anxiety of the Canadian government to people the plains between Winnipeg and the Pacific.

They settled in a little town near Regina. Here George died. Mrs. Donaldson buried him and she was content at least that he had known on his death-bed the freshness of the western wind and the promise it held for his children.

Within the tidy necessity of the living Mrs. Donaldson eked out of the Canadian west, the children had a wholesome upbringing. Betty was the eldest; then came Bill and John. Those who knew the Donaldsons when they first arrived from Glasgow could trace the impulses of heredity as the children matured into youth. Betty and John were keen, ambitious, determined to raise their station in life. Within them was the fierce purpose of their mother when she collected her brood and her ailing husband and broke away from the Glasgow slums.

Betty trained herself for a business position; thereafter lost no time in finding herself a husband and a home. John worked his way through the University, thereafter took a government position as an engineer. When this war broke out he easily obtained a lieutenant’s commission, soon became a captain. But I am running ahead of my story . . .

Bill was much like his father. He grew to young manhood with the same stolid cheerfulness, the same honest simplicity that marked the life and death of Stoker George.

In this tale we are concerned mainly with Bill Donaldson.

Bill was never much. In his youth he talked little and laughed a lot. He went to school grudgingly and resisted effectively the imposition upon his mind of anything more than the fundamentals of literacy. His mother looked upon him with chagrin not unmixed with affection because Bill was in almost all respects Stoker George the younger. He displayed the same contentment with almost nothing of the world’s goods, and he possessed the same honesty of temperament which had made George’s love the only clean and grand experience she had known in the Glasgow slums.

While Betty and John studied and worked, widening their spheres in the community, Bill plodded through youth with heavy tread. He earned his living by sweat, working at any job which happened along requiring a pair of hands and a strong body. He was not a child of the new world, his mother used to say. He still belonged to Glasgow, to the forlorn masses, wanting nothing more than a job, a bed, porridge in the morning and fish and chips at night. In the cacaphony of the growing Donaldson family, Bill played the bass drum, always throwing in a fundamental note, never aspiring to be leader of anything.

Bill was old country in more ways than one. Although his recollections of Scotland were dimmer than those of his brother and sister, the hold of Britain upon his imagination was stronger. He was like Stoker George, who went to the recruiting offices on August 4, 1914. Britain first and forever was his motto.

The blind and desperate patriotism of her people is Britain’s main strength, and Bill had this in fullest measure. His dullish mind rarely glowed, save when the subject of homeland was raised. He could not abide young Canadian intellectuals to whom the British connection was merely a fortunate political and economic arrangement. To him Britain was a religion and the Empire the greatest power for freedom and decency on the face of the earth. He could not argue the point; he merely believed it with the immense passion of his simple nature.

Thus Bill grew from youth into manhood, loved by his family, ignored by his community; he was content with the one as he was oblivious of the other. He didn’t demand much from life and that’s what he was getting. He was happy in an ox-like way, though even his capacity for happiness was limited by the narrowness of his desires.

In 1935, when Bill was twenty-two, a great poverty swept the Canadian west. Farm prices fell disastrously. Grain bulged elevators all over the prairies; it was piled in mountains by railway sidings. While Europe’s masses seethed for want of adequate bread, Canadian wheat withered for want of economic power to move it. The west was gravely stricken.

It was characteristic of Bill that he declined to buck the economic storm. His mother was cared for, thanks to the superior ambition of his brother and sister; so Bill decided to become a soldier. This was an entirely logical move for him. There was security in being a private soldier in the permanent army; there was no future, but that too was quite all right with Bill. Above all, he would be a British soldier. That meant a lot to him.

At Regina Bill caught the transcontinental. He sat in a coach for three days and three nights. Reaching Montreal he moved to the dockyards, hired on a freighter as a deck-hand. Two weeks later he was in Liverpool. And the next day he enrolled for a six-year hitch as a private in the British Army.

Bill was a good soldier and a happy one. His letters to Betty breathed with contentment. The hard routine of Britain’s permanent army patterned Bill’s simple tastes and his pride in wearing the King’s uniform was as great as his pleasure in rediscovering the land he only faintly remembered as a child.

He was like a baby in fairyland. On his first leave he went to London—of course! He arrived in the capital on a foggy October night and, as he wrote Betty, he was so excited he could not sleep. He sat all night at the window of his Jermyn Street hotel and revelled in the anticipation of the dawn which would unfold to him the heart of the Empire, its ancient history and its continuing glory.

As the first streaks of grey daubed the rooftops of Lower Regent Street, Bill was dressed and ready. He strode across Waterloo Place, and through Admiralty Arch, pausing in the misty light to peer at Nelson’s monument. Then he swung down the Mall and feasted his eyes on Buckingham Palace. Thence to Westminster and up Parliament Street where stood the Cenotaph. Here he stopped. He was alone in the street, save for an early morning bus rumbling past. But in his mind’s eye the scene was invested with silent crowds and in a little clearing before the Cenotaph he pictured King George V standing slightly in front of the four Princes. This was his most familiar London setting; he had seen it so many times in newspapers and movies. Now he was here. And the monument was so plain, nothing on it but the words, “The Glorious Dead.” Bill liked that. It made him glad that he was British.

The city awakened to the day’s work while Bill leaned on the sidewall of Westminster Bridge watching the Thames flow past the Commons. It was all just as he expected to find it. In fact, Bill had an uncanny feeling he had been here before; the scenes of glory and tradition fitted too well into the grooves of his imagination. Not for him was the exhilaration of the sightseer gawking for the first time at old world history. These scenes were part of him; he felt a deep satisfaction, a vibrant affinity, a sense of homecoming.

“You know what Mom used to say,” he wrote to Betty. “I’m old country. I guess she’s right.”

If Britain did nothing else for Bill, it awakened in him an urge for writing down his thoughts. Perhaps this was a result of the double impact stemming from the spell of England on his prairie-nurtured mind and a stubbornly unspoken lonesomeness. He wrote voluminous letters on barracks paper and, except for friendly notes at Christmas and Easter, he sent them all to Betty. He admired Betty—always had—and she loved him with the fierce devotion of a worldly woman for her simple and kindly brother.

Reading his letters, the Donaldson family was content that Bill had at last found his niche in life. It was not expected he would ever be anything more than a private—perhaps, with luck, a lance-corporal—because Bill, as his mother constantly reminded Betty, was too much like his father. At least, Bill would have a healthy life. Not like Stoker George who baked at the hole of a furnace most of his days. Bill would travel. His latest letter said they were training for service in India and he was ecstatic over the prospect. “Imagine it. India!” he wrote. “What an Empire! It’s wonderful to be British.”

Of course, Mrs. Donaldson used to say, being a soldier Bill might have to fight some day and that’s dangerous. But this was hardly possible. Mr. Baldwin was such a sensible man and so was Mr. Chamberlain. They were settling things by diplomacy, like the Italian business in Ethiopia, and besides, Britain simply couldn’t afford to fight. No country could. Bill, she mused, was safe enough in the army.

Thus passed the spring of 1930.

Training hard for the promised Indian tour of duty, Bill hardly noticed the headlines in the newspapers of July 20. If he did, he made no mention of it in his letters. A revolution had broken out in Spain when General Francisco Franco moved across the Straits from Spanish Morocco to attack the Republican government in Madrid.

Not only was India on his mind, but Bill had begun to mention often a girl in Birmingham. This disturbed Mrs. Donaldson because Bill’s diffident description of her was not entirely complimentary. She worked in a steelwares factory for two pounds a week, of which she sent one pound home to Leicester. Her father lived on the dole with five small, motherless children. Although she was only eighteen, she had cooked and kept house for the family since she was twelve. Her father beat her regularly—because he was depressed, she said—so one day when she was seventeen she ran away to Birmingham. “She’s pale and thin,” Bill wrote, “but she’s neat and her hair is blonde, real blonde, and piled up on top of her head.”

“Isn’t that Bill to the minute,” said Mrs. Donaldson, looking up from the letter. “She’s pale and thin but she’s neat. And living on one pound a week. Bill would go and lose his heart to her. Isn’t it just as easy to fall in love with a substantial girl?”

In October Bill wrote that she was coughing badly and that the doctor said one of her lungs was infected. “She won’t quit work,” he wrote, “because the county only gives her father nineteen shillings a week for himself and the five kids. I guess I’ll marry her as soon as the army lets me to get her out of that factory. Also because I think she’s fine.”

Bill didn’t marry the girl. In December she died. Bill visited her family in Leicester after the funeral and he wrote home bitterly about the plight of the kids and the hopelessness of their father.

It is not quite clear how Bill came to develop an anguished interest in the Spanish civil war. Probably a combination of events rather than a single incident drew him to ponder, in his simple, puzzled manner, the plight of the Spanish people. Certainly there is no record that he acquired left-wing friends, or that the British Army furnished him a liberal education in European politics.

His brief and tragic romance may have aroused in him an active indignation he never before felt. Perhaps the persecution of Spain’s working-class families made communion with an overtone still sounding in his mind as he came away from the Leicester funeral. Whatever the cause, his letters to Betty during January and February of 1937 made frequent references to the Iberian conflict. Neither astute nor scholarly were these commentaries.

“It’s not right, Betty, it’s not fair,” was his most frequent complaint. Once in the heat of his feeling, he bethought himself a longer sequence, “The government was elected by the people. It was their government. What does this man Franco want?”

At home, Betty and the family were mildly amused and not a little amazed by Bill’s sprawling attempts to lift himself to intellectual heights of discussion. But there was a deadly serious note to Bill’s adoption of the Spanish cause. Thick, honest men come hard to understanding; yet when truth finally seeps into their minds and their hearts, they are seared by a clean passion not given to others who have devoted their lives to the acquisition of cleverness.

At first Bill refused to allow the Spanish situation to compromise his faith in Britain. “It’s just a matter of time,” he wrote. “We’ll never let Franco win. Our army will go in sooner or later and polish Franco off. The British will never let this thing go on in their backyard. I hope we go to Spain instead of India. Anyway, I’ve been hearing rumours.”

A lilt of hope came into Bill’s letters that summer as Loyalist armies swept Mussolini’s expeditionary legions from the fields of Guadalajara. He had a renewal of faith in the outcome of the struggle, and deceived by his own blind reliance in the righteousness of British policy, he attributed the brighter outlook to what he believed was secret British aid.

The truth came to him slowly during the autumn and winter months of 1937. His letters became increasingly anguished, not only because the Loyalists were losing battle after battle but also because disillusion was gnawing at his deep-seated faith in his country.

“Why don’t they send us?” he would write over and over again. “The government is asleep. Aren’t the Spanish people as deserving as the Belgians? We could save them so easily.” Then in a burst of simple passion: “I was brought up to believe that right always triumphs in the end. What if it doesn’t? What if evil is the winner? What happens to everything we know and believe? . . . I just can’t think.”

The bitter trend of Bill’s letters continued into February, 1938. Toward the end of that month, the Donaldson family was chilled by a short note received by Betty. “My regiment has been ordered to proceed to India. I am on two weeks’ embarkation leave. What do you think of it? India instead of Spain! I don’t think I’ll be able to serve there, so far away from everything. Maybe something will happen before I leave. The British have always done their duty well, even if the government won’t. God bless you all. Bill.”

A month later the British Army posted the name of a deserter: Private William Donaldson.

Desertion is serious enough an offense; desertion to avoid embarkation for foreign service is not much less serious than treason. To Bill, revelling in his British uniform and in the daydreams of his youthful exuberance for the homeland, the decision must have been filled with torture—the torture of doubt, not of fear.

Thereafter Betty received two letters from him. One was from Hendaye on the French side of the Franco-Spanish border, the other from Madrid.

At Hendaye he was apparently resolving his doubts. “Tomorrow I will be across the border,” he wrote. “I am satisfied that I am doing what I feel I should do. I am sorry if Mom feels I have brought shame to the family. Please try and explain to her that I have not. I am not going to fight for Spain; I am going to fight for Britain, really. If Britain won’t do the job, some of us who are British must. Some day Mom will understand.”

A month later came the letter from Madrid. It had a lighter tone. “I am living in an old school. It looks like an abandoned grain elevator now taken over by rats. They don’t seem to mind us at all. Damn friendly of ’em! You’d never guess why I have been kept here in Madrid for so long. No kidding, I’m waiting for a rifle. They can’t send me to the front until I’ve got a gun. That’ll give you some idea of what the people here are up against. A fellow coming out of the line hands his gun to the fellow going in. However, they’re fighting against an Italian division north of here and we expect to have plenty of Italian rifles any day now. Well, so long. Bill.”

That was the last letter received from him.

The Fascist shadow broadened and lengthened over Spain during the latter half of 1938, and a corner of it darkened the Donaldson household in Canada. Betty’s frantic letters remained unanswered and with each Franco victory the gloom at home became more ominous.

“If only Bill had joined up with the Mackenzie-Papineau battalion or the Abraham Lincoln brigade or some other English-speaking unit,” Betty said, “we might know what was happening to him. But that’s Bill all over. Never arranges anything. If he had to fight for Spain, why couldn’t he do it properly? No, not Bill. Like a great big ox, he just goes up and begins fighting. I don’t know what to do. I’ve tried to reach him every way. No one seems to know about him.”

Mrs. Donaldson shook her head. “I can’t understand how Bill could ever have decided to go to Spain. His father, bless his soul, was patriotic but he didn’t go around looking for wars that weren’t his own. I just don’t know what got into the boy.”

The Franco rack turned hard on Spain during the following winter, and in the spring of 1939 the breath of resistance was running out. German, Italian and Spanish regulars, black troops of the Spanish African regiments, equipped by Krupp and Junkers and Messerschmidt smashed down on the people’s armies from the west and the north. Weary volunteers trudged back to Hendaye and other French border towns; beaten, starved and embittered they were, many wounded, some dying.

On March 28, 1939, following the rout and slaughter of Loyalist battalions on the plains of Aragon, the end came. Human endurance had reached its last tortured moment and then was no more. Generalissimo Francisco Franco adjusted his most striking sash and made a triumphal entry into Madrid.

The hope that fled the hearts of the Spanish people on that day remained stubbornly in the Donaldson household. There were thousands of Loyalist troops in the concentration camps of southern France. More thousands lay in Spanish prisons. Perhaps Bill was among those forlorn warriors.

Betty appealed to an organization known as Friends of the Mackenzie-Papineau battalion with headquarters in Winnipeg. In June of that year she received a reply. Because Bill was not a member of the Canadian unit, no definite information was available. But a report was received that he had fallen in the last retreat from Aragon.

On September 3, 1939, the British people finally learned the true nature of the Spanish tragedy. Now they were part of the pattern. The lesson came to them from the awkward lips of Neville Chamberlain at eleven a.m. on that Sunday morning, the same Neville Chamberlain who, sitting these years in the enlightened atmosphere of No. 10 Downing Street, failed to share the awareness instinctive in that thick-set, dullish youth called Bill Donaldson.

The Canadian Parliament declared war on Germany seven days later. And John Donaldson, Bill’s younger brother, joined his university O.T.C. to train as an officer.

It is one of the weaknesses of our war effort and one of the dangers of the post-war period that men will fight for their country more readily than for the ideals which made their country beloved to them. For Mrs. Donaldson it was only natural and fitting that her remaining son should go to war. At the same time her grief for Bill was anguished by the circumstance that she could not understand why he should have been in Spain at all.

John drew his commission as a lieutenant and sailed to Britain with an early Canadian contingent. He had a lively intelligence, an attractive manner and a fine education. He got along well in the army. Soon after his arrival in England he attained his captaincy and became adjutant of his battalion.

One day, late in 1940, he received a letter from Betty. It read: “I have news of Bill. Just this morning the Mackenzie-Papineau people wrote that Bill was wounded and spent many months in hospitals in Spain and the south of France. This news comes from Canadian wounded just repatriated from France. They say Bill suffered ugly wounds on the left side of his body and face, that he was discharged from hospital still an invalid, and that he is back somewhere in England. Mom is frantic. Do try to find him.”

John was beset by doubts. His first reaction was to disbelieve the story that Bill might be alive. If Bill were, surely he would have written home! Then again, John thought, Bill was still, in the eyes of the British Army, a deserter with a heavy prison sentence awaiting him. Even this, though, should not have prevented him from getting secretly in touch with the family. No, John thought, he must be dead. Then hope argued again. Perhaps Bill was so cruelly crippled he felt it best to disappear into a world of his own.

These considerations swirled within John as he moved about London on a seven-day leave. The city was in turmoil. Each night the underground shelters were jammed with weary people; each morning the streets were filled with rubble and shattered glass and crisscrossed with hose-lines. This was the full flower of the Guernica experiment, and John began to know the simple truth of his brother’s passion. “I am not going to fight for Spain; I am going to fight for Britain, really,” he recalled from Bill’s letters.

At Communist headquarters in London there was no hope. The Party had never heard of Bill Donaldson. John was referred to an organization called Friends of Republican Spain. Here, a thin man with a haggard, deeply-lined face received John and nodded slowly as the story was unfolded.

“Yes,” he said sadly. “I know of your brother. He died on the field at Aragon. He was a magnificent fighter.”

If hope is but a flicker, there is no great shock when it is snuffed out. There is often relief in decision no matter how tragic. John mumbled his thanks and walked from the room. His search was ended. Aimlessly he trudged London’s streets on this lowering November afternoon; suddenly his leave had become bereft of purpose and he was just another soldier on a holiday in a strange city. He traversed the shabby turnings of Aldgate, wondering how he might spend the rest of the evening. His first inclination was to make for Victoria Station and return to camp where he had friends to talk to and a useful job to command his energies. He dismissed this idea almost the moment it entered his mind; after all, a seven-day leave was too precious to pass up. He thought of a club on the Haymarket where Canadians congregated. It had a good bar. But this, too, was foreign to his mood. Perhaps he had better go to his hotel and write a letter to Betty.

Darkness was falling fast over the frowsy, smoke-stained streets when John came across a queue shuffling into the underground shelters for the night. Many of the hollow-eyed men held babies. The women carried blankets and greasy parcels of food and like sheep dogs herded unhappy children before them. The queue moved slowly and those in the street glanced anxiously at the sky, then shouted impatiently toward the head of the line. The crowd pushed forward. Children cried. Women snapped at one another like fishwives.

John watched this bedraggled procession disappear into the mouth of the underground. This was Britain, he thought; no longer proud, still defiant, but no longer supreme master of her destiny. He was glad Bill was not here to see it—Bill to whom Britain was a religion and London the grand arbiter of mankind’s ills. As John watched London cower under the night skies he felt somehow that Bill’s fate was not altogether without pattern or order. He had an idea Bill was one of the last of the great Britons.

The bombs fell almost simultaneously with siren’s howl. A piercing whistle in violent crescendo assailed John’s ears, and he flattened himself on the pavement, burrowing close to a brick wall and throwing his arms around the back of his head. An explosion convulsed the pavement. John lay motionless for a few moments; then hearing the shouts of men and the patter of feet, he lifted his head and looked around. A near-by fire bathed the street with a pink glow. Steel-helmeted men were running into the next turning. From the shadows of doorways dark figures were racing frantically to the underground entrance. John scrambled to his feet and followed them down dimly-lit stairs until the lowest level was reached.

Here were the people of Aldgate shuffling about in a confused babel of crying babies and excitable conversation, of smells and sighing and hysterical laughter. The explosions above were now dull thumps like the sound of a distant bass drum.

John squeezed through to the far end of the platform and found a square foot of sitting space between a gaunt, fear-stricken woman and a one-legged young man. The latter picked up his crutch to make room for John.

“How do you know when the raid is over? Do they tell you?” John asked.

The crippled youth smiled. “Don’t worry, brother. It won’t be over till morning. No use climbing all those stairs. You’ll just have to come back.”

“But I’ve got to get down to Piccadilly.”

“Why?” said the youth. “It’s even worse down there.”

John shrugged his shoulders, pulled his cap over his eyes and tried to doze.

“This your first raid, Canada?”

John nodded. The crippled youth was clear-eyed and handsome in a dark, stubby way. John figured he was a Jew.

“Does this happen every night in London?”

“Oh, they’ve been giving us a packet most every night for three months now,” the youth said. Then, as an afterthought: “I envy you that uniform, brother. At least you’ll be able to go after them. I won’t—any more. They’ve fixed me for fair.” He patted his crutch.

“Bombs?”

“No. Bullets.”

“France?”

“No. Spain.”

John swallowed the words that came to his lips. Bill was a closed chapter and he would not reopen it. He pulled his cap over his eyes and simulated sleep. The air was putrid and the woman on his left kept sniffling and talking to herself.

“Why did you go to Spain?” John asked haltingly.

The youth’s shrill laughter sang bell-like over the babel. “Because, you silly ass, I wanted to fight them while we still had a chance to beat them. It was better than this, I’ll tell you, a lot better. Is this a way to fight the bastards? Naah! Climbing into holes like a lot of rabbits! Some of us didn’t wait like a lot of idiots I know strutting around in their fancy uniforms and singing ‘Rule Brittania’—but don’t take this personally, brother . . .”

“It’s okay,” said John. “My brother fought there, too.”

“In Spain?”

“Yes. Spain.”

“Mackenzie-Papineau bunch?”

“No. He went by himself.”

“Oh. What’s his name?”

“Bill Donaldson.”

“Bill Donaldson . . . Hmm . . . So you’re his brother. That’s nice . . . What’s he doing now?”

“He was killed.”

“Where? Here?”

“No. In Spain.”

“Did you say Bill Donaldson? . . . Stocky little Canadian? . . . The wires are crossed somewhere, brother. He was in hospital with me.”

“Did you know him? What hospital?”

“No, I didn’t know him. But he was there all right—in a place near Bordeaux. There were hundreds of us there. I couldn’t get around on account of my leg. But Bill Donaldson was in the gang. I heard them mention him a lot. Machine-gun bullets in his left side and shrapnel in his face. But he made the grade. He left the hospital before I did.”

“Did he go back to Spain?”

“Of course not. This was June, 1939. It was all over . . .”

The next morning John went to Scotland Yard. A man whose manners were excruciatingly polite listened to the story almost from the very beginning. Then he disappeared into a file room, was away an endless time, perhaps half an hour. When he returned he carried a card in his hand.

“There is very little we can do,” he said. “Not the way London is today. This is your brother’s card. We got it from the Army a long time ago. Charge of desertion. But it’s not in the current file any more. You see, we simply haven’t the manpower to keep cases alive as long as we are accustomed to. Nowadays, with this blitz and all, there are too many urgent cases . . . No, I’m afraid we’ll have to have more specific information if we are going to reopen the case . . .”

Months passed. The blitz was relegated to memory. Russia had withstood the great attack and was now throwing the Germans back from Moscow and the Caucasus. Dieppe was bright and recent history.

John’s interim visits to Scotland Yard produced nothing but uniformly polite headshakes. His frequent excursions with his one-legged friend to the haunts of Spanish war veterans brought nothing but vague reminiscences of Spanish battlefields and French hospitals.

One morning in September, 1942, at his station on the south coast, John opened a letter. It was neither dated nor signed.

It read: “Bill Donaldson is living at 136, Strathcombe Street, near the London Docks.” The handwriting was not Bill’s.

Quickly obtaining leave on compassionate grounds, John was an hour later on a train bound for London. At Victoria he hired a taxi. Painfully, slowly, it rolled along the Embankment, through the city, down Commercial Road. And finally it creaked to a stop in a grey and deserted street before a two-storey dwelling.

A short and shapeless woman opened the door. As she noticed John’s rank she wiped her hands on her apron.

“Yes, indeed, sir,” she said, nodding her head vigorously. “Mr. Donaldson is one of the guests here and a very nice gentleman he is . . . Bill Donaldson, yes. The Canadian gentleman . . . No, he’s not in at present. But if you care to wait, sir.”

John sat in a parlour full of threadbare chairs and cheap china. The housekeeper bustled around him and pointedly placed an ashtray within six inches of John’s cigarette.

“No, I’m sure Mr. Donaldson won’t be long,” she said in the panting fashion of overstuffed persons. “He usually comes in about four. He can’t work long hours, poor man, you know. He was dreadfully hurt in the war, you know—the Spanish war—and his whole left side is a mass of pain. I’ll never know how he gets along. And so kind with it all . . . We’re all ever so fond of him, poor man . . . He never mentioned having a brother here in England. But then, he never talks much about home. He never talks much about anything. He’s on the quiet side, you know . . .”

John was glad when she bustled out of the room, panting. He wanted to think what he would say if his brother Bill really did walk into the room. Yet he could not think clearly. He was confused by doubt and by the wreckage of so many hopes previously dashed. His mind could not encompass the end of the search; the endless trail had become so much a part of the routine of his life. He pondered how Bill would look; he hadn’t seen him for seven years. He tried to imagine what Bill would say—if this man were Bill. He didn’t believe it possible, and yet the evidence seemed so conclusive . . .

The minutes were not winged. John started and snuffed out his cigarette each time he heard the doorbell ring; then relaxed and relighted when it turned out to be the postman, the raid warden, the housekeeper’s sister dashing in for a drop of sugar. The ashtray was filled with John’s half-smoked cigarettes.

Then the front door banged shut without benefit of ring, and John heard a woman’s panting voice say, “Oh, Mr. Donaldson, there’s a visitor to see you in the parlour. I didn’t know you had a brother here . . .”

John’s eyes were glued on the door. In the half light that struggled through the old-fashioned curtains, he saw a heavy-set figure, not quite straight, head bent over the left shoulder. And he heard a deep voice saying, “My brother? There must be some mistake . . .”

The man limped forward to the centre shaft of light. John darted toward him, then turned away momentarily. He could say nothing. His throat was choked with bitterness.

“I thought I heard Mrs. Simmons say something about a brother. There must be some mistake.”

“I’m sorry,” John said. “The mistake must be mine. I was looking for a man called Bill Donaldson. I was told he lived here.”

The man sat down and looked eagerly at John.

“But I am Bill Donaldson,” he said. “And you are? . . .”

“My name is John Donaldson. I had a brother called Bill who was missing after the Spanish war and I thought—”

“And you thought I might be your brother. That’s sad. I’m sorry, really sorry. I know how you must feel.”

John picked up his hat and gloves.

“Please sit down. Perhaps Mrs. Simmons will make us some tea. I think I can help you a little, just a little. You see, I fought in Spain, too, and though I never met him, I heard about your brother—many times from many people. It seems a long time ago now, but we were always getting mixed up. It was only natural. Two Bill Donaldsons from Canada—fighting in Spain. I came from Montreal and your brother came from—Calgary?”

“Regina.”

“Yes, Regina. It was quite a coincidence. Two Bill Donaldsons from Canada. Let’s see if Mrs. Simmons will get us some tea and I’ll tell you all I know about your brother. I think—I think you need look no more.”

Bill Donaldson held his tea cup with his right hand and smiled a crooked smile which was lost in the scars on the left side of his face.

“The Spaniards loved your brother. I often lived in his reflected glory when I came to Madrid and later in France. He was a section leader—that would be about a corporal in our army—and he fought in all the big actions of the last eighteen months. I don’t think we won a single one of those battles. Those were the bad times. But the Spaniards loved your brother because he was cheerful, laughing all the time, and he had a hatred of the Fascist that must have grown very deep and very strong inside him.

“I’m sorry. You want to know what happened to him. Well, I’ll skip the stories I heard about him in the early battles. There’s no record of them anyway, except in the hearts of the Spanish peasants who fought with him. But this, I know. It was told to me by a man who got away to France after the collapse.

“It must have been around the middle of March—in ’39. You know what was happening then. We were done for—we knew it. They’d prepared the last push for a long time. Germans and Italians, Moroccans and Spanish regulars were in the encirclement move on the Aragon front. They had heavy artillery, mortars and planes, hundreds of ’em. We had nothing. Some of us didn’t even have rifles.

“Your brother’s regiment was falling back with the rest. In good order? Well, yes. The units on the flanks had first priority on the rifles so the Fascists couldn’t pull their squeeze play. We knew there was no hope, but if we could get as many men as possible into France—perhaps, we thought, they might fight again, when the world woke up.

“Well, there came a time when we didn’t even have enough rifles to cover our flanks. Some who had rifles didn’t have ammunition. It was a pitiful retreat. We died by the thousands.

“On one of the last days, it got really desperate. They were almost around us. We were not delaying their advance effectively enough. Only a series of counter-attacks could do that. But we had no ammunition, hardly any food. The colonel called for volunteers. And your brother’s whole section stepped forward. A few of the men had grenades. Your brother Bill made himself a club from the branch of a tree.

“There was no time to wait for darkness. In broad daylight your brother led his section against the Fascists. He was last seen, club in hand, advancing on a machine-gun post. Club in hand, John! Club in hand—against machine-guns . . .”

John and I leaned on the rail of the troopship and we watched the peaks of Spain rising over the ground haze. Our convoy moved swiftly into the open waters of the Mediterranean—swiftly to the battlefield and the enemy. The same enemy.