* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: How to Parse

Date of first publication: 1878

Author: Edwin A. Abbott (1838-1926)

Date first posted: Aug. 21, 2017

Date last updated: Aug. 21, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170817

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

HOW TO PARSE.

An Attempt to Apply the Principles of Scholarship

TO

ENGLISH GRAMMAR.

WITH APPENDIXES

ON

ANALYSIS, SPELLING, AND PUNCTUATION.

BY THE

REV. EDWIN A. ABBOTT, D.D.,

Head Master of the City of London School.

FIFTH THOUSAND.

JAMES CAMPBELL & SON,

TORONTO.

Entered according to the Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand eight hundred and seventy-six, by James Campbell & Son, in the Office of the Minister of Agriculture.

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HUNTER, ROSE AND CO.,

TORONTO.

The First Part of this book is intended for pupils so far advanced as to be able to distinguish the Parts of Speech. The author’s object has been to teach elementary English Grammar as simply as is consistent with the honest recognition of difficulties, and not to accumulate masses of information that might be of use to foreigners, but must be useless to English boys.

I have been accused, by a very friendly and favourable reviewer, of “unkindness” in completely ignoring the “Article” in my introductory treatise How to Tell the Parts of Speech. It has occurred to me, in consequence, to prefix to this work a Glossary of Grammatical Terms—many of them, let us hope, obsolete or obsolescent. Here the pupil may now and then refresh his memory as to the meaning of Article, Genitive, Nominative, Accusative, Case, Proper Noun, Conjugation, Decline, and the like; and by this means he will be able in satisfy himself that many of these terms, when applied to the Grammar of his native tongue, are absolutely superfluous or erroneous. It is also probable that ready access to a Glossary, explaining etymologically Cardinal, Inflection, Apostrophe, Climax, Bathos, Verse, &c., may in many cases be of positive as well as negative benefit.

The Exercises are specially written to illustrate the rules. This has involved some labour; but I am convinced that the labour was well spent. A pupil cannot be regarded as thoroughly tested in his knowledge of grammatical rules till he has applied them to connected narrative. As long as he is tested in nothing but short sentences, you can never feel sure that his accuracy is not merely mechanical.

Paragraphs 1—82 are of a much simpler character than those that follow; and the pupil should be well drilled in them before passing onward. The grammar-lessons of three or four months may be very well spent in teaching boys how to select the Subjects and Objects of the different Verbs in a Sentence, and a month or two more may well be given to Relative Sentences. Indeed, if the majority of a class of boys, between 11 and 12 years old, can, after six months’ training in grammar, parse “jay” in:—

“The jay that robbed the other birds of their feathers was afterwards punished for robbing them”—

I should, myself, think the six months spent to very good purpose.

Paragraphs 82—162 are decidedly more difficult, and constitute work for a higher class. The chapter on the Subjunctive Mood is put last, out of its place, owing to the extreme difficulty of the subject.

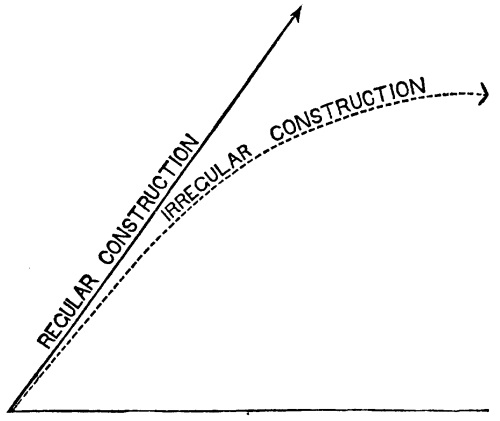

The chapter on Irregularities, Paragraphs 191—230, is of a different nature from the former part of the book. It is intended to prepare the pupil for Part II., and is an attempt to apply the principles of scholarship to the explanation of the irregularities of English Grammar. These principles are few, and capable of brief enunciation, viz., (1) that every irregularity is a deviation from a “regula” or rule; (2) that there must be some attracting force to produce this deviation; (3) that this attracting force is generally one of three causes, of which the “confusion of two constructions” is by far the most common. Simple and brief though they are, these principles require, as every teacher knows, careful and constant inculcation before the pupil is imbued with them. But when the pupil has once mastered them, he has the key to unlock any idiomatic irregularity, in any language—always provided that he is well acquainted with the particular language in its regular expressions.

Not much space is given to Analysis; but perhaps as much as the subject deserves. If this subject is to be taught at all—and there is much in it that constitutes a useful mental exercise—it ought, in the opinion of the author, to be disencumbered of its present technicalities, and to be taught more logically. For example, in most treatises on Analysis, it is assumed that, in such a sentence as:—

“Feeling the man’s hand in my pocket I turned suddenly round,”

—the words “feeling the man’s hand” are an Adjective Phrase, or “Enlargement of the Subject.” But nothing surely ought to be more obvious than that (whatever the grammatical construction may be) “feeling” here means “when, or because I felt,” and is nearly the same as “on feeling;” so that the words in question form really an Adverbial, and not an Adjectival Phrase. It is almost startling that this Adjectival error should have been gravely inculcated for a generation in the best, as in the worst, treatises on English Grammar. Possibly the servile imitation of Latin Grammar—the ruin of all good English teaching—has been at work here, as in so many other cases, assimilating the English to the Latin Active Participle, and ignoring the extent to which the English Participle has been merged in the English Verbal Noun.[1]

For these reasons, in the Chapter on Analysis, several changes have been introduced with the view of discarding technicalities: and the terms Phrase, Clause and Sentence, are rigidly used according to their definitions. (See Glossary and also Par. 239.)[2]

In the “Hints on Spelling,” Paragraphs 266—291, an attempt has been made to give explanations, or suggestions of possible explanations, of a few among the thousand anomalies that strew this wilderness and despair of teachers. The author has at least succeeded (Par. 283) in impressing upon himself, what he never could remember before, the right spelling of “succeed,” “proceed,” and “exceed.” Whether others will derive the same benefit from the explanation is perhaps doubtful; but the mere fact that an explanation exists is a just cause for thanksgiving. Mr. Laurie’s useful Manual of Spelling has been of great service in the composition of this chapter.

Part II. Chapter I., is explained by its title, “Difficulties and Irregularities in Modern English.” It is intended for the higher (not for the highest) classes in our first-grade schools. Here I must acknowledge very large obligations to Mätzner’s two volumes on English Syntax. Adopting his arrangement, I have selected from these two volumes every difficulty that appeared likely to be a difficulty to an English boy—I believe I may add, in many cases, to an English man—as distinct from a foreigner. A few examples from Campbell, Scott, and Byron have been quoted from Mätzner, unverified; but in such cases, the reader is always warned by a foot-note. The vast majority of the examples have been modified or re-written to illustrate the difficulty under consideration, or they are the fruits of my own reading.

In this part of the work it has been of course necessary to illustrate modern English by older English of different periods: and here, while again acknowledging my obligations to Mätzner, I must also add the name of Dr. Morris, whose elaborate Historical Outlines of English Accidence—a book that, the more you study it, impresses you the more with the feeling that much is left to study—have been laid under large contributions for this part of my work, and more especially for the Appendix on the “Growth of the English language.” Here I have also to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Mr. Skeat, who was kind enough to correct the proof-sheets of the Appendix, and from whose edition of the Gospel of St. Mark[3] I derived great help in obtaining an insight into the “Period of Confusion” in early English. I have had the less hesitation in occasionally referring to statements and examples about early English found in the Shakespearian Grammar, because all of these were supervised and many of them originated by Mr. Skeat, but for whose kindness and learning I should scarcely have ventured on ground of which it may be said, no less than of the field of criticism, that—

“Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.”

The chapter on Poetical Constructions will, I hope, be found as useful as any in the book. It is an attempt to draw out in grammatical detail the principles of poetry as laid down by Professor Seeley and myself in English Lessons for English People, and to lead the pupil to see the reason and the beauty of “poetical irregularities.”

In the Appendix on the “Growth of the English Language,” I have ventured so far to differ from Dr. Morris, in his account of the “Periods of the English Language,” as to assign a separate period to the sixteenth century, and also to give names to the several periods. I do not think boys will find it easy to remember the periods without epithets of a rather more picturesque nature than ordinal numbers. I have also added some remarks on the Elizabethan period.

A few tables of the Early Forms are added in the Appendix with the view of illustrating remarks scattered through the book. But no attempt has been made to give any complete system of Accidence. To try to do this completely, in the face of Dr. Morris’s Accidence, would have been superfluous: and to do it imperfectly, in the way in which it has been done in many Grammars, under the title of “Etymology,” would have been worse than superfluous, mystifying English children by telling them what, when they know what well enough already, and need only to be told why. But to tell the why of English Accidence requires—and it is useless disguising the fact—a great deal of knowledge in the teacher and not a little in the pupil. If it is to be done at all, it should be done thoroughly, with the aid of such a book as Dr. Morris’s, and by pupils old enough to appreciate it.

Consequently, though the pupil will find “strong” and “weak” verbs defined in the Glossary, he will see no lists of them in the book. Lists of irregular plurals will also be missing; the teacher will look in vain for focus, foci; datum, data; nebula, nebulæ. The only apparent sacrifice to the mania for “learning something by heart” is this, that the modern verb will be found “conjugated” in the Appendix to Part II. But this has been done, not to give the pupil something to learn by heart, but to enable him to compare the old verb with the new at a glance. Throughout the book, the author has endeavoured to keep in view the main object of a teacher teaching English grammar to English children, viz., to teach, not so much what as why.

The division of the book into parts, the first of which is differently arranged from the second, might cause some difficulty in referring, were it not that a full Alphabetical Index is inserted at the end—an appendage that, in the Author’s opinion, may fairly claim to be accepted as a compensation, in a book of this kind, for many faults of non-arrangement or mis-arrangement.

In passing the book through the press I have derived most valuable assistance from the two gentlemen whose names I had occasion to mention in the preface to How to Tell the Parts of Speech, viz., Mr. G. S. Brockington, one of the Assistant Masters of King Edward’s School, Birmingham, and Mr. T. W. Chambers, B.A., Scholar of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, one of the Assistant Masters of the City of London School, whose sound judgment and practical experience have frequently induced me to modify or even re-cast large portions of the First Part. I must also mention two others among my colleagues, Mr. T. Todd, and Mr. James Pirie, M.A., whose criticism and corrections have been of very great service.

Lastly, while expressing my obligations to the admirable “Shakespeare Lexicon,” compiled by Dr. Schmidt, and published by Messrs. Williams & Norgate, I may be also permitted, coming nearer home, to say that I have gained much help and many apt examples from the inspection of the proof-sheets of a Complete Concordance to the Poetical Works of Pope, compiled by my father, and now in course of publication.

[1] See Paragraphs 585—595.

[2] I gladly acknowledge my obligation to Mr. Mason for his excellent method of indicating the Subordination of Sentences by underlining.

[3] The Gospel according to St. Mark, in Anglo-Saxon and Northumbrian Versions, Synoptically Arranged. Edited for the Syndics of the University Press by the Rev. Walter W. Skeat, M.A. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, & Co. 1871.

| PART I. | |||

| ETYMOLOGICAL GLOSSARY OF GRAMMATICAL TERMS | xvii | ||

| RULES AND DEFINITIONS | xxviii | ||

| CHAPTER I. | |||

| SUBJECT AND OBJECT | 1 | ||

| CHAPTER II. | |||

| THE RELATIVE PRONOUN | 17 | ||

| CHAPTERS III. and IV. | |||

| USES AND INFLECTIONS: | |||

| I. | Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, &c. | 28 | |

| II. | Verbs | 45 | |

| CHAPTER V. | |||

| THE INDIRECT OBJECT, &C. | 88 | ||

| CHAPTER VI. | |||

| THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD | 112 | ||

| CHAPTER VII. | |||

| IRREGULARITIES | 127 | ||

| APPENDIX I. | |||

| THE ANOMALIES OF THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD | 148 | ||

| APPENDIX II. | |||

| THE ANALYSIS OF SENTENCES | 153 | ||

| SCHEME OF ANALYSIS | 172 | ||

| APPENDIX III. | |||

| HINTS ON SPELLING | 174 | ||

| APPENDIX IV. | |||

| HINTS ON PUNCTUATION | 185 | ||

| SCHEME OF PARSING | 195 | ||

| PART II. | |||

| DIFFICULTIES AND IRREGULARITIES IN MODERN ENGLISH. | |||

| CHAPTER I. | |||

| PROSE | 199 | ||

| CHAPTER II. | |||

| POETICAL CONSTRUCTIONS | 281 | ||

| APPENDIX. | |||

| ON THE GROWTH OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE | 293 | ||

| ALPHABETICAL INDEX | 327 | ||

[1] For all detailed reference the reader is referred to the Alphabetical Index at the end of the book.

Few of the terms explained below are used by the author, and many of them are misused or badly constructed, e.g. “article,” “accusative.” But, as they are used in many grammatical treatises, it has been thought desirable to explain them, especially as an explanation is sometimes the best means of proving them to be superfluous or erroneous, when applied to English Grammar.

The References, when not otherwise stated, are to the Paragraphs in How to Parse.

The meaning given opposite to each word is the Etymological meaning. For a fuller or more accurate definition the pupil is referred to the Paragraph mentioned in each case.

Ablative (Case) [L. ab., “from;” latus, “carried”]. The name for a Latin case denoting, among other things, ablation, or carrying away from.

Absolute (Construction) [L. ab, “from;” solut-, “loosed”]. A construction in which a Noun, Participle, &c., is used apart, i.e. loosed from, its ordinary Grammatical adjuncts (Par. 135).

Abstract (Noun) [L. abs, “from;” tract-, “drawn”]. The name of an abstraction, i.e. of something considered by itself, apart from (drawn away from) the circumstances in which it exists.

Accent [L. ad, “to;” cantus, “song”]. Perhaps originally a sing-song, or modulation of the voice, added to a syllable. Now used of stress laid on a syllable.

Accidence [L. accident—“befall”]. That part of grammar which treats of the changes that befall words.[1]

Accusative (Case).[2] The Latin name for the Direct Objective Inflexion. Possibly the Romans regarded the object as being in front of the agent, like an accused person confronted with the prosecutor.

Active (Voice). The form of a Verb that usually denotes acting or doing.

Adjective [L. ad, “to;” jact, “cast or put”]. A word put to a Noun.

Aphæresis [Gr. ap, “from;” hairesis, “taking”]. Taking a letter or syllable from the beginning of a word.

Adjunct [L. ad, “to;” junct, “joined”]. A word grammatically joined to another word.

Adverb [L. ad, “to;” verb, “word” or “Verb”]. A word generally joined to a Verb (45).

Adversative [L. adversus, “opposite”]. An epithet applied to Conjunctions that (like “but”) express opposition.

Affix [L. ad, “to;” fix, “fixed”]. A syllable or letter fixed to the end of a word.

Agreement. The change made in the inflections of words so that they may suit or agree with one another in a sentence. (78).

Alexandrine. A rhyming verse of twelve Iambic syllables, said to be so called from its being used in an old French Poem on Alexander the Great.

Alphabet [Gr. alpha, beta; “a,” “b”]. The list of letters, so called from the names of the first two letters in Greek.

Anacolouthon [Gr. a-, “not;” acolouthon, “following”]. A break in the Grammatical sequence, or following.

Analysis [Gr. ana, “back;” lusis, “loosing”]. Unloosing anything (e.g. a Sentence) back into its constituent parts. Hence an analytical period in a language. See Par. 556.

Anomaly. A Greek-formed word meaning “unevenness,” “irregularity.”

Antecedent [L. ante, “before;” cedent, “going”]. (a) That part of a sentence which expresses a condition (167). So called because the condition must go before its consequence. See consequent (2). (b) Also used for the Noun that goes before a Relative Pronoun.

Anti-climax. The opposite of a climax. A sentence in which the meaning sinks in importance, instead of rising at the close.

Antithesis [Gr. anti, “against;” thesis, “placing”]. The placing of word against word, by way of contrast.[3]

Apodosis [Gr. apodosis, “a paying back”]. A Greek name for the “Consequent.” The condition was regarded by the Greeks as demanding its consequence, as a sort of debt, to be paid in return for the fulfilment of the condition.

Apostrophe [Gr. apo, “from;” strophe, “turning”]. A mark shewing a vowel is omitted, so called because it is turned away from the next consonant.[4]

Appellative [L. appella, “call to.”] Another name for the Vocative or calling use of a noun. Paragraph 32.

Apposition [L. ad, “near;” posit, “placed”]. The placing of one noun or pronoun near another, for the purpose of explanation (137).

Archaism [Gr. archaios, “ancient”]. An ancient word or expression.

Article [L. articulus, “a little joint or limb”]. A name (a) correctly given by the Greeks to their “article” because it served as a joint uniting several words together; (b) then loosely used by the Latins (as was natural seeing they had no “article”) of any short word whether Verb, Conjunction, or Pronoun; (c) foolishly introduced into English, and once used to denote “the” and “a.”

Aspirate [L. ad, “to;” spira-, “breathe”]. The strongly breathed letter, h.

Asyndeton [Gr. a, “not;” syndeton, “bound together”]. The omission of Conjunctions, so that sentences are not bound together.

Attribute. A quality attributed to a person or thing.

Auxiliary (Verbs) [L. auxilia-, “to help”]. Verbs that are used as helpers or companions to other Verbs (95).

Bathos [Gr. bathos, “depth”]. A ludicrous fall to a depth, i.e. a descent from the elevated to the mean in writing or speech.[5]

Cardinal (Numbers) [L. cardin-, “hinge.”]. That on which anything hinges or turns: hence, “important,” “principal.” A name given to those more important forms of Numeral Adjectives from which the Ordinal forms are derived.

Case [L. Casus, “falling”]. The Latin translation of the Greek term for the uses of a Noun. The Greeks regarded the subjective form as “erect” and the other forms as more or less falling away from it. Hence the terms “oblique,” “decline” &c.

Clause [L. claus-, “shut”]. A number of words shut up within limits. In this book the word is used of a sentence preceded by a Conjunction, the sentence and Conjunction together being called a Clause (239).

Climax [Gr. climax, “ladder”]. The arrangement of a sentence like a ladder so that the meaning rises in force to the last.[6]

Cognate (Object) [L. Co-, “together;” nat- “born”]. The name given to an object that denotes something akin to (born together with) the action denoted by the Verb (125).

Colon [Gr. colon, “limb”]. The stop marking off a limb or member of a sentence.

Comma [Gr. comma, a “section”]. The stop marking off a section of a sentence (294—308).

Common (Noun). A name that is common to a class and not peculiar or proper to an individual.

Comparative (Degree). The form of an Adjective denoting that a quality exists in a greater degree in some one thing than in some other with which it is compared.

Complementary [L. comple-, “fill up”]. That which completes or fills up (97, 106).

Complete (State). A name given to an action (whether Past, Present, or Future) that was, is, or will be complete (72).

Complex (Sentence) [L. con- “together;” plic-, “fold”]. A sentence that is folded together, or involved. Hence a sentence containing one or more Subordinate sentences (250).

Compound (Sentence) [L. con, or com, “together;” pon- “place”]. A sentence made up of a number of Co-ordinate sentences placed together (247).

Concord. The name given to syntactical agreement between words, e.g. between Verb and Subject.

Conjugation [con, “together;” jugatio “joining”]. A number of Verbs joined together in one class.[7]

Conjunction [L. con, “together;” junct-, “joined”]. A word that joins two sentences together.

Consequent. The name given to that part of a Sentence which expresses the consequence of the fulfilment of a condition. See Antecedent, and Paragraph 167.

Consonant [L. con, “together;” sonant-, “sounding”]. Letters (such as p) that can only be sounded together with a vowel.

Continuous (State). The name given to an action (whether Past, Present, or Future) that is, was, or will be continuing or incomplete (72).

Copula [L. copula, “bond”]. The word “is,” so called because it binds or connects Subject and Predicate in Logic.

Correlatives. Words that are related together or mutually related, e.g., “either,” “or;” “both,” “and;” “when,” “then.”

Dative [L. dativ[8] “that which has arisen from giving”]. The Latin name for the Indirect Objective case used after Verbs of giving &c. (126).

Declension. The bending or declension of the Oblique (see Oblique below) cases from the Subjective form, which was regarded as “erect.” Hence applied to the statement of the cases of a Noun.

Definite (Article). A name given to the Adjective “the” from the fact that “the” defines its Noun. See Article.

Definition [L. de, “from:” finit-, “marked out,” “bounded”]. That which marks out the boundaries of anything so as to distinguish it from all other things. N.B. Not a mere “description.”

Degree (of comparison) [L. gradus, Fr. degré, “step”]. The forms expressing the steps or degrees in which a quality can be expressed by an Adjective.

Dentals [L. dent-, “tooth”]. Consonants pronounced with the aid of the teeth; d, n, t.

Dependent (Sentence). Sometimes used for Subordinate. But generally applied to Subordinate sentences that are the Subjects or Objects of Verbs.

Diæresis [Gr. diairesis, “separation”]. The mark placed over one of two vowels to show that each is to be pronounced separately e.g. in “aërial.”

Diphthong [Gr. di, “twice;” phthongos, “sound”]. Two vowel sounds pronounced as one.

Direct (Object). The Noun that denotes what is regarded as the direct object of the action of a Verb.[9]

Ellipsis [Gr. elleipsis, “omission”]. The omission of words (said to be “understood” i.e. implied) in a Sentence.

Emphasis [Gr. emphaino, “I make clear”]. Stress of the voice laid on particular words or syllables in order to make the meaning clear.

Epigram [Gr. epi, “on;” gramma, “writing”]. A writing on a monument. Hence a short poem. Hence a short pointed poem or saying.[10]

Epithet [Gr. epithetos, “placed to”]. An Adjective placed to a Noun to describe some quality of the person or thing denoted by the Noun.

Etymology [Gr. etymon, “true meaning;” logia, “science”]. The science of the true meaning of words, according to their derivation.

Euphony [Gr. eu, “well;” phone, “sound”]. That which sounds well.

Flat (Consonants). B, d, g.

Foot. The metrical sub-division of a verse. A verse being supposed to run, its limbs or members might well be called feet.

Frequentative (Verb). A Verb that expresses a frequently repeated action, e.g. “pat-t-er.”

Gender [L. genus, Fr. genre, “breed,” or “class”]. Forms to denote classification according to sex. There are no inflexions for Genders in English (37).

Genitive (Case) [L. genitiv-, “generating”]. The name for the Latin case denoting generation, origination, possession. Sometimes applied to the English Possessive Inflection.[11]

Gerund [L. gero, “I carry on”]. Part of a Latin Verb denoting the carrying on of the action of the Verb. There was once a gerundive form in English (551).

Grammar [Gr. gramma, a “letter;” Fr. “grammaire”]. The science of letters; hence the science of using words correctly.

Gutturals [L. guttur, “throat”]. Throat letters, k, and hard g.

Heterogeneous (Sentence) [Gr. hetero, “different;” genos, “kind”]. A Sentence combining a number of Sentences of so different a kind from each other that they ought not to be combined.[12]

Iambus [Gr. iambos]. In English, a foot of two syllables, the first unaccented, the second accented.

Idiom [Gr. idioma, “peculiarity”]. A mode of expression peculiar to a language.

Imperative (Mood). [L. impera-, “command”]. The commanding Mood (70).

Impersonal (Verbs). Verbs not used in the first or second Person (328).

Incomplete (State). The forms of the Verb denoting an action in an Incomplete State (72).

Indefinite (Article). A name given to “an,” “a,” because the Adjective leaves its Noun undefined, or indefinite. See Article; also Definite.

Indefinite (State). The forms of the Verb denoting an action of which the State is not defined (72).

Indicative (Mood), [L. indica-, “point out”]. The Mood that points out or indicates an action, &c., as a past, present, or future existence (70).

Indirect (Object). The Noun or Pronoun denoting the person or thing regarded as not directly but only indirectly influenced by the action of the Verb. But see Paragraph 118 for a more satisfactory test.

Infinitive (Mood) [L. in, “not;” finit-, “limited”]. A Mood not limited by any definition of Person or Number (70).

Inflection [L. inflecto, “I bend”]. The bending of a word from the simple form, by means of varying the termination. See Oblique below.

Interjection [L. inter-ject-, “thrown between”]. An utterance thrown in between words, to express emotion. Not a Part of Speech.

Intransitive (Verb). [L. in, “not”; transitiv-, “passing across”]. A Verb whose action is not supposed to pass across to any Object. But see Transitive below.

Labials [L. labium, “lip”]. Lip-letters: f, v, p, b, m, hw (the real sound in which) and w.

Language [L. lingua, Fr. langue; “tongue”]. The expression of meaning by the tongue.

Linguals [Latin lingua, “the tongue”]. Letters whose sounds are produced by the tongue; sh, s in pleasure.

Liquids. Letters of a flowing, liquid sound, as l, r.

Metaphor [Gr. meta, “from one to another”; phora, “carrying”]. The carrying of a relation from one set of objects to another e.g. of the relation of ploughing from “plough” and “land,” to “ship” and “sea.”[13]

Metre [Gr. metron, “measure”]. The measuring of language out into verses.

Monosyllable [Gr. mono, “only”]. A word of only one syllable.

Mood [L. mod-, “manner”.] The form of a Verb expressing the manner of action (70).

Mutes [L. mut-, “dumb”]. Letters that are dumb, without the aid of a vowel: k, g, t, d, n, p, b, m.

Nasal [L. nas-, “nose”]. Consonants sounded through the nose; n, m.

Nominative (Case) [L. nomina-, “to name”]. An old Latin term for the Subject, used because the Subject was regarded as a person or thing named.

Noun [L. nomen, Fr. nom, “name”]. The name of anything.

Object. The word, or group of words, denoting that which is regarded as the object or mark aimed at by the action of a Verb or the motion of the Preposition.[14] (13). But see Definition in Paragraph 14.

Oblique (Case). A name given to all Cases but the Subjective. By the Greeks the Subjective form of a Noun was regarded as erect, and all the other forms as fallings or oblique deviations from the Subjective.

Ordinal (Adjective) [L. ordin-, “order”]. An Adjective, that answers to the question “in what order.”

Orthography [Gr. ortho, “correct”; grapho, “I write”]. The correct writing of words, i.e. correct spelling. N.B. Not “calligraphy,” “pretty writing.”

Parenthesis [Gr. para, “aside”; enthesis, “insertion”]. A word, phrase, or sentence, inserted aside, or by the way, in a sentence complete without it.

Participle [L. particip-, “participating”]. A form of a Verb participating of the nature of a Verb, and of the nature of an Adjective.

Partitive [L. part-, “part”]. Denoting partition.

Passive (Voice) [L. pass-, “suffering”]. The form of a Verb in which the Subject is supposed to suffer an action[15] (60).

Palatals. Letters whose sounds are produced by the palate: ch, j.

Perfect (Tense) [L. perfect-, “complete”]. The Name for the Latin Tense that has to represent (owing to the paucity of their Tenses) the Indef. Past and Complete Present.

Period [Gr. peri, “round”; od-, “path”]. (1) The full, rounded path of a complex sentence, (2) a mark at the end of a sentence.

Person [L. per, “through”; son-, “sound;” hence, persona “a mask through which an actor sounds;” “an actor’s part in a play.”]. The part played in conversation, whether (1) speaking; (2) spoken to; (3) spoken of (79).

Personification. Endowing what is impersonal with a Personal Character.[16]

Phrase [Gr. phrasis, a “saying”]. A group of words not expressing a statement, question, or command (239).

Pluperfect (Tense) [L. plu-, “more;” perfect-, “complete”]. A more than complete Tense. A Latin way of expressing the Complete Past.

Plural (Number) [L. plu-, “more”]. The form of a Noun that denotes more than one (34—36).

Poetry [Gr. poietes, a “maker”]. Language that is artistically made, as distinguished from that which is ordinarily written or spoken.

Polysyllable [Gr. poly, “many”]. A word of many syllables.

Positive. The simple form of an Adjective; so called because it expresses a quality not comparatively, but positively (42).

Possessive (Use) [L. possess-, “possessed”.] The name given to the use or case of a Noun denoting possession (37).

Potential (Mood) [L. potent-, “powerful”]. An old name for a supposed Mood, which is really either the Mood of Purpose, or else simply the Indic. of an Auxiliary Verb. So called, because it involves the meaning of power or possibility.

Predicate [L. “prædica-,” “proclaim,” “state”]. A word or group of words making a statement about a Subject (263).

Prefix [L. præ, “before;” fix-, “fixed”]. A letter, syllable, or word fixed before another word.

Preposition [L. præ “before;” posit-, “placed”]. A Word (not a Verb) placed before a Noun or Pronoun as its object.

Preterite (Tense) [L. præterit-, “past”]. A pedantical expression for “the Past Tense.”

Prodosis [Gr. pro, “before;” dosis, “giving”]. Literally, giving before. Hence, in a sentence, the Antecedent or Condition. See Apodosis.

Pronoun [L. pro, “for;” L. nomen, “noun”]. A word used for a Noun.

Proper (Noun). [L. propri-, F. propre; “peculiar”]. A name that is peculiar or proper to the individual, not common to a class. See Common.

Prose [L. prosa, for prorsa, for pro-versa,[17] i.e. “turned forward”]. Writing that does not turn like verses (see Verse below) but runs straight on. Hence, the straight forward arrangement of prose.

Prosody [Gr. prosodia, a “song”]. Hence, that part of Grammar which treats of verse, whether intended to be sung or not.

Punctuation [L. punctum, “point”]. Dividing a sentence by means of points representing the pauses.

Quantity. The quantity of time necessary to pronounce a syllable.

Redundant [Latin re(d), “back;” undant-, “flowing”]. Flowing back or over, i.e. superfluous. N.B. This word is often lazily used to appear to get rid of a difficulty. But few words are, strictly speaking, redundant; they serve some purpose, although the purpose may not be easy to detect.

Reflexive (Verb) L. [reflect-, “bend back”]. A Verb in which the action of the Subject is as it were bent back on the Subject, so that the Subject and Object denote the same person or thing.

Relative (Pronoun) [L. re, “back;” lat-, “carried”]. A name given to who, which, &c. when they do not carry one forward (as they do when used Interrogatively) but carry one back to the Antecedent.[18]

Retained (Object). The name given to one of the Objects of a Transitive Verb when retained as the Object of the same Verb in the Passive (123).

Rhyme [A.S. rim, “number”], identity of sound (from the vowel to the end) between two syllables at the end of two lines.[19] The Anglo-Saxon Poetry was not based on rhyme but on alliteration.

Rhythm [Gr. rhythmos, “flowing motion”], the flowing regular motion of verse and of periodic prose.

Root. That form from which another word springs, as a tree springs from its root.

Semicolon [L. semi, half; Gr. colon, “limb”]. Half of the colon, i.e. of the stop that marks off a separate limb or member of a sentence.

“Sensuous” [L. sensu-, “sense”]. Appealing to the senses. Milton says that Poetry should be “simple, sensuous, and passionate.”

Sentence [L. Sententia, a “meaning”]. A group of words of a meaning so far complete as to express a statement, question, command (239).

Sharp (consonants): k, p, t, so called from their sharp sound.

Sibilant [L. sibila-, hiss]. Hissing letters: s, z, sh.

Simile. A sentence expressing the similarity of relations e. g. between “plough” and “land,” “ship” and “sea.”[20]

Solecism [Gr. soloikismos; “speaking like the men of Soloi”[21]]. Inaccuracy of expression.

Spirants [L. spira-, “breathe”]. Letters in the pronunciation of whose sounds the breath is not wholly stopped, as it is in the pronunciation of “mutes.”

Stanza [It. stanza, a “stop”]. A division of a poem containing every variation of measure in the poem, and generally furnishing a stopping place at its termination.

Strong (Verbs). Verbs that make their Past Tenses and Passive Participles not by adding -ed, -t, but by vowel changes.

Style [L, stilus, “an instrument for writing”]. A manner of expressing thought in language.

Subject [L. subject-, “placed under”]. That which is placed under one’s thoughts, as the material or topic for speech. Hence, the Subject of a Verb is said to be that about which the Verb makes a statement. But see Par. 1, note.

Subjunctive (Mood) [L. subjunct-, “subjoined”]. A Mood expressing a purpose, condition, &c., subjoined to some statement, question, or answer (163).

Subordinate (sentence) [L. sub, “beneath;” ordin-, “rank”]. A sentence that ranks beneath another sentence. See Par. 249.

Substantive (Noun) [L. substantia, “substance”]. A useless name given to Nouns denoting things said to have substantial existence.

Suffix [L. sub, “beneath,” fix-, “fixed”]. Same as Affix.

Superlative (degree) [L. super, “above;” lat-, “carried”]. An Adjectival form denoting the expression of a quality in a degree carried above other degrees (42).

Supplement [L. sub, “up;” ple-, “fill”]. That which fills up, or supplies what is wanting in a Verb (148).

Syllable [Gr. syn, “together;” lab-, “take”]. A group of letters taken together so as to form one sound.

Syncope [Gr. syn, “altogether” or “quite;” cope, “cutting”]. A considerable curtailment[22] or cutting of a word, by omitting letters in the middle, e.g. ne’er for never.

Syntax [Gr. syn, “together;” taxis, “arranging”]. The arrangement of words together in a sentence.

Synthesis [Gr. syn, “together;” thesis, “placing”]. Placing together parts so as to form a whole. The opposite of analysis. Hence a synthetical period in language. See Par. 551.

Tense [L. tempus, Fr. temps, “time”]. The forms of a Verb indicating the time of an action (71).

Transitive [L. trans, “across;” it-, “going”]. A Verb that has an Object, so called because the action of the Verb is regarded as passing or going across to the Object (55).

Trochee [Gr. trochos, “a running”]. In English, a foot of two syllables consisting of an accented, followed by an unaccented syllable. So called from its brisk, or running nature.

Verb [L. verb-, “word”]. The chief word in a sentence.

Verse [L. vert, “turn”]. A line of poetry at the end of which one turns to a new line.

Vocative [L. voca-, “call”]. The use or case of a Noun when the person or thing is called to (32).

Vowels [L. vocalis “having voice”]. The letters that have a voice or are sounded (not as the “consonants” but) by themselves: a, e, i, o, u.

Weak (Verbs). Verbs that form their Past Tenses and Passive participles by adding d or t, and not by changed Vowel.

[1] Quintilian I. 5, 41: “frequentissime in verbo, quia plurima huic accidunt.”

[2] Probably a Latin mistake. The Greek original meant (1) cause, (2) accusation. The Latins took it in sense (2) instead of (1).

[3] See How to Write Clearly, Par. 41.

[4] In Rhetoric, the apostrophe is the turning away from one’s audience to address some absent person. The old name for the Grammatical apostrophe was apostrophus; and this would be useful to distinguish it from the Rhetorical term.

[5] See Par. 40, How to Write Clearly.

[6] See Par. 39, How to Write Clearly.

[7] Hence to conjugate a Verb is to repeat the inflections belonging to the class or conjugation. But the Romans used decline and not conjugate in this sense (Madvig).

[8] Termination -ivus in Latin, when added to Participles, denotes that which has arisen from, e.g. “captivus,” that which has arisen from “capture.”

[9] See Par. 14.

[10] The point will generally be at the end. Intentional “bathos” sometimes borders on “epigram.” See How to Write Clearly, Par. 42.

[11] The Latin “genitivus” is a mistranslation of the Greek genike, which meant the generic case i.e. the case, that denoted the genus or class. For example, “life,” “What class of life?” “Man’s life.”

[12] See Par. 43, How to Write Clearly.

[13] English Lessons for English People, page 78.

[14] This Definition, though in accordance with Etymology, is often Grammatically inapplicable.

[15] This definition is unsatisfactory, see Par. 60.

[16] English Lessons for English People, page 131.

[17] Compare our e’er, o’er for ever, over.

[18] See How to Tell the Parts of Speech, p. 124.

[19] Syllables altogether identical do not rhyme.

[20] See English Lessons for English People, page 126.

[21] The derivation usually given, but probably inaccurate.

[22] Perhaps “a cutting in the middle so as to pull the extremes together.”

It is assumed that the ten following Definitions are known to the pupil:—

1. A Noun, is a name of any kind (page 19[1]).

2. A Pronoun is a word used for a Noun (page 21[1]).

3. An Adjective is a word that can be put before a Noun either to distinguish it, or to point out its number or amount (page 32[1]).

4. A Verb is a word that can make a statement (page 39[1]).

5. An Adverb is a word that answers to the question “how?” “when?” “where?” or “how far is this true?” (page 54[1]).

6. A Preposition is a word that can be placed before a Noun or a Pronoun, so that the Preposition and Noun or Pronoun together are equivalent to an Adjective or Adverb (page 76[1]).

7.[2] A Sentence is a collection of words expressing a statement, question, or command (page 45[1]).

8.[2] Any other collection of words, having a meaning, is called a Phrase (page 45[1]), or Clause. See Glossary.

9. A Conjunction is a word that joins two sentences together (page 85[1]).

10. A Relative Pronoun is a Conjunctive Pronoun used so as to refer to a preceding Noun or Pronoun called the Antecedent (page 125[1]).

[1] The figures denote the pages of How to Tell the Parts of Speech on which the first ten Definitions will severally be found.

[2] A Sentence preceded by a Conjunction ceases to state, command, or question; it therefore becomes a Phrase, e.g. “When I saw John.” Such a Phrase may conveniently be called a Clause. See Par. 239.

1. The Subject of a Verb making a statement is the word or words answering to the question “who?” or “what?” before the Verb (Par. 1).

2. The Object of a Verb or Preposition is the word or words answering to the question “whom?” or “what?” after the Verb or Preposition (14[1]).

3. When the Relative is followed by a Conjunction introducing a new Sentence, leave out this sentence in parsing the Relative (24).

4. The Antecedent must sometimes be supplied from the sentence (25).

5. The Relative is sometimes omitted (26).

6. Some Pronouns are used Interrogatively, Conjunctively, and Relatively (28).

7. The Uses or Cases of a Noun are four, viz. Subject, Object,[2] Possessive, and Vocative (32).

8. The Plural of a Noun is formed by adding -s to the Singular (34).

9. The Possessive Use or Case, in the Singular and Plural, is formed by adding ’s to the Singular or Plural form (37).

10. An Adjective has three Degrees of Comparison, viz. Positive, Comparative, and Superlative (42).

11. To form the Comparative and Superlative, add -er, -est to Positives of one Syllable. “More” and “most” are used in other cases (43).

12. A Verb that can have an Object is called Transitive; a Verb that cannot, is called Intransitive.[3]

13. The Passive Voice of a Transitive Verb is the form assumed by the Verb when its Object is made the Subject (60).

14. The Active Voice of a Transitive Verb is the form that can be used with an Object (61).

15. A Participle can be distinguished by the fact that it can be, in part, replaced by a Conjunctive word (66).

16. Each Voice has four Moods: Infinitive, Indicative, Imperative, and Subjunctive (70).

17. The Infinitive Mood speaks of an action without defining the doer (70).

18. The Indicative Mood definitely points out an action (70).

19. The Imperative Mood commands an action (70).

20. The Subjunctive Mood expresses condition, purpose, wish, &c. (70).

21. Verbs have three Tenses: Past, Present, and Future (71).

22. Each Tense has four “States” of Action: the Indefinite, the Complete, the Incomplete, and the Complete Post-Continuous (73, 74).

23. A Verb agrees with its Subject in Person and Number (78).

24. “May,” “can,” “must,” “will,” “shall,” “let,” &c. are called Auxiliary Verbs (95).

25. “To” is omitted in the Infinitive after the Auxiliary Verbs, and after “see,” “hear,” “feel” (96).

26. An Infinitive may be used (1) as a Noun; (2) as an Adverb; (3) as an Adjective.

27. The Indirect Object of a Verb is the word or phrase answering to the question “For, or, to, whom?” “For, or, to, what?” when used after the Verb and the Direct Object (118).

28. When an Active Verb taking two Objects is changed into the Passive Voice, one Object becomes the Subject of the Passive Verb, but the other is retained as Object (122).

29. Some Verbs, generally Intransitive, can take an Object of a nature akin or cognate to the Verb, called the Cognate Object (125).

30. The Object is sometimes used Adverbially to denote extension, price, point of time (127—131).

31. The Subject, generally with a Participle, is sometimes used Adverbially (135).

32. A Noun or Pronoun, not Subject or Object of a Verb, but so connected with another Noun or Pronoun that we can understand between them the words “I mean,” “that is to say,” &c., is said to be in Apposition to the latter (137).

33. Nouns and Pronouns are used Subjectively when in Apposition to Subjects, and Objectively when in Apposition to Objects (138).

34. The (1) Intransitive Verbs “is,” “looks,” “seems,” “appears,” &c., and (2) the Transitive Verbs “make,” “create,” “appoint,” “deem,” “esteem,” being used to express identity, and, as it were, to place one Noun or Pronoun in apposition with another, may be called Verbs of Identity, or Appositional Verbs (147).

35. Verbs of Identity, when Intransitive and Passive, take a Subjective Supplement; when Transitive, take an Objective Supplement (150).

36. “It” and “there” are sometimes irregularly used to prepare the way for the Subject or Object (151).

37. In a Conditional Sentence, (1) the Clause expressing the condition is called the Antecedent; (2) the Clause expressing the consequence of the fulfilment of the condition is called the Consequent (167).

38. Auxiliary Verbs (when not following “if” or any other Conjunction expressing Condition) are used Indicatively, whenever they can be altered into the Indicatives of other Verbs (181).

39. Whenever language is irregular, there is some cause for the irregularity (192).

40. The three principal causes of irregularity are I. Desire of brevity; II. Confusion of two constructions; III. Desire to avoid harshness of sound or of construction (198).

41. A Simple Sentence is a sentence that has only one Subject and only one Stating, Questioning, or Commanding Verb (245).

42. When several Simple Sentences are connected by “and,” “but,” “so,” “then,” &c., so that each sentence is, as it were, independent, and of the same rank as the rest, each is called a co-ordinate Sentence[4] (246).

43. A Compound Sentence is a Sentence made up of Co-ordinate Sentences (247).

44. When a number of Sentences are connected by Conjunctions that are not Co-ordinate, the Sentence that is not introduced by a Conjunction is called the Principal Sentence (248).

45. Sentences connected with a Principal Sentence by Conjunctions that are not Co-ordinate are called Sub-ordinate[4] (249).

46. A Complex Sentence is the whole Sentence formed by the combination of the Principal and Subordinate Sentences (250).

47. When a word passes from one form to another, a letter is often changed or doubled in order to preserve the original sound (266).

48. Final -e is dropped before an affix beginning with a vowel, but retained before an affix beginning with a consonant (270).

49. A monosyllable ending in -ll, when followed by an affix beginning with a consonant, or when itself used as an affix, generally drops one -l (275).

50. If the termination of a word is a consonant preceded by a vowel, then, on receiving an affix beginning with a vowel, the final consonant in the word is doubled, provided that the word is a monosyllable, or accented on the last syllable (277).

51. When a word is separated from its grammatical adjunct by any intervening Phrase, the Phrase should be preceded and followed by a comma[5] (224).

[1] These and the following References are to the Paragraphs in How to Parse.

[2] If the Indirect Object is called a separate use, there will be five Uses of a Noun.

[3] The usual Definitions are given in Par. 55; but they are very unsatisfactory.

[4] The mark of a Subordinate Sentence is that when preceded by its Conjunction, it cannot generally stand as a Sentence by itself. A Co-ordinate Sentence can thus stand by itself.

[5] For words, idioms, &c., the pupil is referred to the Alphabetical Index at the end of the book.

HOW TO PARSE

1

The Subject in a Stating Sentence.

All Verbs that make a statement must be accompanied by some Noun, or equivalent of a Noun, about which the statement is made:—

(1) “Thomas failed.”

(2) “He failed.”

(3) “The attempt to take the city failed.”

(4) “That he failed is certain.”

In each of the three examples above, if you ask the question “Who or what failed?” the answer, being the subject of our statement, is called the Subject of the Verb.

This leads us to a Definition:

The Subject of a Verb in a stating sentence is the word or collection of words answering to the question asked by putting “Who?” or “What?” before the Verb.[1]

[1] It is not enough to say that the Subject is “that about which the statement is made.” For, in “A tempest wrecked our ship,” the statement is just as much about “ship” as about “tempest”; but “ship” is not the “Subject.”

2 Caution I. If the Verb is accompanied by an Adverb, as—

(1) “He seldom sleeps.”

(2) “She does not sleep.”

—the Adverb should be repeated in the question:

(1) “Who seldom sleeps?” Answer: “He,” Subject.

(2) “Who does not sleep?” Answer: “She,” Subject.

3 Caution II. If the Verb is accompanied by words necessary to give the meaning, as—

(1) “John is a mere boy.”

(2) “Thomas was made happy.”

—these words may be repeated in the question:

(1) “Who is a mere boy?” Answer: “John,” Subject.

(2) “Who was made happy?” Answer: “Thomas,” Subject.

4

The Subject in a Questioning Sentence.

In a Questioning Sentence, e.g.—

(1) “Did John come?”

—ask “Did who come?” Answer: “Did John come?” Therefore “John” is the Subject.

5 Caution. If the Sentence only answers our question by repeating “Who?” “What?” “Which?” &c. as—

(1) “What made you so foolish?”

(2) “Who saw him die?”

—then, “Who?” “What?” “Which?” are themselves the Subjects.

6

The Subject in a Commanding Sentence.[1]

The Subject in a Commanding Sentence is almost always “you”; or, in Poetry, “thou” or “ye.” It is generally not expressed:

(1) “Stay (you) where you are: the rest may go.”

(2) “Follow (thou) me.”

[1] In these sentences, the name “Subject” is usually given to the Pronoun denoting the person to whom the command is addressed.

7 Caution. Where a Verb follows a Conjunction, as—

(1) “. . . that the attempt may prosper.”

(2) “. . . if Thomas helps me.”

—it is useful sometimes to repeat the Conjunction before “Who?” or “What?”:—

(1) “That what may prosper?” Answer: “The attempt,” Subject.

(2) “If who helps me?” Answer: “Thomas,” Subject.

The Conjunctions “and,” “but,” “for,” “then,” “so,” “therefore,” &c. need not be repeated.

Exercise I. (Specimen).

Find out the Subjects of the italicized Verbs in the following Exercise:[1]—

Once upon a time there* lived[2] a mighty king whose* name was Xerxes, and he reigned over Persia. Does every boy know where Persia is? If you do not know, look it out in the Map. Though he was king of the Persians, and reigned over almost all the nations of the East, yet he was not satisfied with this; nothing but the whole world could satisfy him. So, learning that a little nation lived not far from him, on the other side of the Ægean sea, and had not yet submitted to him, the king determined to conquer it. This nation, which consisted of several independent cities—Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and many others—was called altogether by the name of “Greeks.” All the Greeks together, when they mustered all their fighting men, did not amount to a hundred thousand, while Xerxes was obeyed by more* than a million of soldiers. Besides, the Greeks were often divided against themselves, one city fighting against another, so that they seemed to have no chance against the Great King—for this was the name by which the King of Persia was known.

Xerxes did not believe for a moment that the Greeks, few and divided as* they were, would resist him. So before he collected an army, he determined to try peaceable means. Accordingly he sent heralds to all the principal cities in Greece, and bade them demand from each city “earth and water.” What made him ask for that? Why, you must know this was the Persian way of demanding obedience and subjection; for, among them, giving earth was the sign of surrendering their land to the Great King, and giving water meant that they surrendered their sea and navy to him. The heralds therefore, with this message from Xerxes, went forth on their several journeys.

“Who lived?” “A mighty king,” Subject.

“Does every boy know?” “Does who know?” “Every boy,” Subject.

“If who do not know?” “You,” Subject.

“Look it out.” A command: Subject “you,” implied.

“Though who reigned?” “He,” Subject. (Note that reigned is joined by the Conjunction “and” to the Verb was, and both these Verbs follow the Conjunction “though.” We therefore repeat “though,” in asking the question to find the Subject. Note, also, that the answer is “he,” not “Xerxes.” The answer must always be a word in the sentence.)

“Who or what could satisfy him?” “Nothing but the whole world,” Subject.

“Who or what had (not yet) submitted?” “A little nation,” Subject. These words are also the Subject of lived, which is joined to had submitted by “and.”

“Who or what was called?” “This nation,” Subject.

“Who or what did (not) amount?” “All the Greeks,” Subject.

“Who was obeyed?” “Xerxes,” Subject.

“Who were often divided?” “The Greeks,” Subject.

“Who seemed?” “They,” Subject.

“What made him ask?” Here the answer is the same as the question, viz. “What;” and “What” is the Subject of “made.”

“What was (the sign of surrendering)?” “Giving earth.” Subject.

[1] In this Exercise, and in those that follow, the Pupil may be asked to point out Nouns, Verbs, Adverbs, &c. But in that case, words marked thus * should be omitted.

[2] The term “Subject” includes not merely the Noun that answers to the question “Who?” or “What?” before the Verb, but also all Adjectives or Adjective Phrases put to the Noun; e.g. “a mighty king” is the Subject of “lived.” “King” may be called the “Noun part of the Subject,” or the “Noun Subject.”

8

Position of the Subject.

The Subject of a Verb expressing a statement generally (a) comes before the Verb; but it (b) sometimes comes after the Verb, e.g. when “there” or an emphatic Adverb, or some other emphatic word, comes at the beginning of the sentence:—

“He reigned in Persia.”

“There is no doubt about it.”

“Next came my brother.”

“ ‘Stop,’ cried the soldier.”

9 In Poetry, the Subject often comes after the Verb (See Pars. 513—4):—

(1) “Loud blew the blast.”

10 In Questions, the Subject is generally (1) in the middle of the Verb, but sometimes (2) after the Verb—

(1) “What did the man say?”

(2) “What said the man?”

—unless the Subject happens to be “Who” or “What”—

(1) “Who saw him die?”

Exercise II.

Write down the Subjects of the italicized Verbs in the following Exercise:—

When the heralds had arrived at the cities of Greece, and delivered their message, they were received differently in different places. Some cities gave earth and water, because they were afraid of the Great King; others, because they were jealous of their neighbours, and hoped the Great King would help them and destroy their enemies. But the men of Athens and of Sparta would give neither earth nor water. Indeed the Athenians were so angry at the message, that they threw one of the heralds into a pit, and bade him take his earth thence; another they threw into a well, telling him that he could find water there.

Xerxes, when he heard how his heralds had been treated, and how the men of Athens and Sparta had refused earth and water, determined at once to levy an army and to conquer Greece. Never before was so vast a host collected. They drank whole rivers dry.* The Hellespont, across which they had to pass into Greece, was bridged with boats: a promontory (its name was Mount Athos) was cut through to give a passage to their fleet. And now this monstrous army, amounting to a million at least, had penetrated Greece, and was marching southward. Still no one ventured to oppose them, and in a few days the hosts of Xerxes, with undiminished numbers, had reached a pass called Thermopylæ.

11

Different forms of the Subject.

The Subject may be—

1. A Noun, Pronoun, or Adjective put for Noun:—

“John runs,” “He runs,” “Who runs?” “That is a mistake.”

2. A group of Nouns connected by “and”:—

“Two and three make five.” “You and I are cousins.”

3. A Noun-Phrase, or Noun-Clause:—

(1) “To write an exercise without a fault requires much care.”

(2) “That he was guilty was not proved.”[1]

[1] The Noun-Clause in (2) may be called a Noun-Sentence, for convenience; but it must always be borne in mind that a Sentence preceded by a Conjunction, so that it no longer states, questions, or commands—ceases, strictly speaking, to be a Sentence, and becomes a Clause. See the Definitions, p. xxviii. The word Phrase includes Clause.

Exercise III.

Write down the Subjects of the italicized Verbs in the following Exercise:—

“What is a pass?” perhaps you ask. A narrow path with steep mountains on both sides is called a pass. In this case there* were mountains on one side, and, on the other side, was a marshy place stretching down to the sea, so that there* was only room for a cart or two to pass. In such a place, to resist a host was an easy matter for a few* brave men. But, just then, the Greeks were terrified. To remain at Thermopylæ seemed to them certain death; so they determined to retreat. Then Leonidas, who was king of the Spartans, when he found that he could not persuade the other Greeks to remain, determined to remain by himself with a few* brave Spartans, to resist Xerxes, and to gain time for his countrymen. With him remained about three hundred men, and the* rest* departed.

When Xerxes, after arriving at Thermopylæ, saw the handful of Spartans prepared to resist him, he laughed at them, and bade his soldiers bring them to him in chains. But the Persian soldiers, on advancing to the charge, found that their master was mistaken in his laughter. Charge after charge was made by the Persians, but to no purpose. The Persians were slain in hundreds, but the Greeks were neither taken nor driven back. That the Persians were no match for the Greeks was made evident even to the proud King Xerxes; and, when the sun set, he retired to his tent in great sorrow.

12

The Object.

Supply what is wanting to complete the sense after the following Verbs and Prepositions:—

1. The grey-hound killed ____. 2. I am travelling towards ____. 3. The woodman felled ____. 4. The soldier shot ____. 5. We wish for ____. 6. We desire ____. 7. I look for ____. 8. John is seeking ____. 9. I come to ____. 10. They reach ____. 11. The cart-wheel ran over ____. 12. I am thinking about ____. 13. I am living in ____.

The best way to supply what is wanting is to repeat the Verb or Preposition, and ask whom? or what? (not before the Verb, as when you were finding the Subject, but) after the Verb.

For example, “Killed what?” Answer: “A hare.” “Towards what?” Answer: “Paris.”

Now “hare” is called the Object of the Verb “killed,” and “Paris” the Object of the Preposition “towards.”

13

“Object” means “put in the way.” Just as a target is put in the way of the marksman, and is called the object at which he shoots, so the word or group of words answering to the question whom? or what? after a Verb or Preposition, often denotes the object of the action of the Verb, or of the motion implied by the Preposition. For example, “the hare” is the object of the action of “killing”: “Paris” is the object of the motion implied in “towards.”

Hence the name “Object” is given to the words answering the question whom? or what? after the Verb or Preposition, even in some cases where the name may seem misapplied.

For example, in “He is travelling from Paris,” you can hardly say that Paris is the object of motion. Nevertheless, in conformity with the general rule, “Paris” is called the “Object” of the Preposition “from.”

14 The word or collection of words answering to the question whom? or what? after a Verb or Preposition is called the Object.[1]

[1] As in finding the Subject, so here, if the Verb is modified by “not,” or any other Adverb, the Adverb may be repeated with the Verb in asking the question.

15

Different forms of the Object.

The Object, like the Subject, must be a Noun, or the equivalent of a Noun:—

1. A Noun or Pronoun:—

“I like playing, John, nothing.”

2. A group of Nouns connected by “and”:—

“He is sitting between you and me”; “This railway connects Paris and Brussels.”

3. A Noun-Phrase, or Noun-Clause:—

(1) “I like to play, to hear music, hearing music, a rascal to be punished.”

(2) “I know that he was not guilty.” “I asked whether he had arrived.”

16

Position of the Object.

The Object generally follows the Verb or Preposition, but not always. For example:—

I. When the Object is an Interrogative or Relative Pronoun:—

(1) “Whom did you see?”

(2) “The house that I live in.”

17 II. When the Object is emphatic:—

(1) “Silver and gold have I none.”

(2) “Not one word did he say.”

(3) “Some he killed, others he took alive.”

18 III. In Poetry (514):—

“A monarch’s sword when mad vain-glory draws.”

19

Some Verbs have no Object.

Some Verbs denote (1) states, e.g., “be,” “remain,” “seem,” “appear,” and generally all forms of “be” followed by the Verbal forms in -ed, -en, &c.; others denote (2) actions not regarded as having an external object, e.g., “run,” “walk,” &c.

These two classes of Verbs do not take a Grammatical Object. The former class suggests the question “who?” not “whom?” e.g., “He seems ——”; “seems who or what?” Answer, “He seems a rascal.” Here “rascal” answers to the question “who?” (not “whom?”) and is not called the Object of “seems.” See Par. 147.

Exercise IV. (Specimen)

Find out the Objects of the italicized Verbs and Prepositions in the following Exercise:—

Next day the Persians attacked the Greeks again, but to no purpose. Not the slightest impression did they make on the little Greek phalanx. Their gold and silver armour was no match for the steel spears of the brave Greeks. Besides, the Greeks were fighting for their country, while the Persians did not want to fight, and were driven to the battle with the lash. So the sun set again, and Xerxes found that he was again defeated. But, that night, while the King was angrily thinking that he should have to retreat, a traitor came to his tent and offered to show him a path over the mountains, by which the Persians might come down behind the Greeks, and thus (might) attack them in the rear as well as in front. At once, a Persian battalion set out under the guidance of the traitor, and by sunrise next morning, the Persians, with two vast hosts, had shut in[1] the little band of Greeks between the sea, the mountains, and their enemies.

“Attacked whom?” “The Greeks,” Object.

“They did (not) make what?”[2] “The slightest impression,” Object.

“For what?” “The steel swords of the brave Greeks,” Object.

“For what?” “Their country,” Object.

“Did (not) want what?” “To fight,” Object.

“With what?” “The lash,” Object.

“Found what?” “That he was again defeated,” Object.

“Was (angrily) thinking what?” “That he should have to retreat,” Object.

“To what?” “His tent,” Object.

“Offered what?” “To show him a path over the mountains,” Object.

The rest you can answer for yourself.

[1] “Shut in” is one Compound Verb. See How to Tell the Parts of Speech, p. 77.

[2] See Note on page 10.

The term “Object” includes, not merely the Noun, but the whole of the answer to the question “whom?” or “what?” after the Verb. The Noun-part of the Object, may, for convenience, be called the Noun-Object, and may be stated separately, if desired, e.g., “the slightest impression” is the “Object,” but “impression” is the “Noun-Object,” of “did make.”

20 Many parts of the Verb that take no Subject may take an Object.

For example, you cannot ask “Who or what killing?” but you can ask “killing whom or what?” Consequently “killing” can have no Subject, but may have an “Object.” And so may “to kill.”

Exercise V.

Find out the Objects of the italicized Verbs and Prepositions in the following Exercise:[1]—

Leonidas saw at once that he and his men had no chance of escape. But instead of lamenting, he seemed delighted at the thought of dying honourably. He told his men to clean their armour and weapons, and to prepare themselves as if for a feast. Then, when the sun was sinking, “Take your suppers,” said he, “and remember that you will take your breakfast elsewhere.” But in that little band there was not one man that feared to die; for a soldier’s death was counted an honourable, and not a terrible thing, among the Greeks. When night came, out marched the Greeks against the army of Xerxes. Wherever they went, they carried death and terror with them; they overturned the tent of Xerxes and slew his guards. The proud king was forced to flee for his life; and, if the night could have lasted for a night and a day, perhaps they might have destroyed the whole of that vast host. But, when day began to dawn, the enemy discovered the small number of the Greeks, and took courage. The Greeks were weary with slaying their thousands, the Persians were fresh; the Greeks were three hundred men, the Persians were more than three hundred thousand. So the Persians gathered round the Greeks, attacking them with slings and darts and spears, because they did not dare to attack them in close fight. When the Greeks charged, the Persians fled from them; when the Greeks retired, the Persians approached them. First one and then another of the Greeks fell beneath the shower of darts, others were wounded and could scarcely stand; but none would surrender. Before sunset, every Greek was slain, and the Persian army had gained the victory. But, from that day to the present (day), all men have honoured the names of Leonidas and his brave Greeks, who have left for us and for all men an example teaching us not to be afraid of dying honourably.

[1] The Subjects of the italicized Verbs may also be found both in this and in the preceding Exercise.

Exercise VI.

Write or repeat the Subjects of the italicized Verbs, and the Objects of the italicized Verbs and Prepositions, in the following Exercise:—

Tommy had heard from Mr. Barlow many stories about the taming of wild animals; so he thought to himself he should like to tame[1] a pig. He had heard that the youngest animals are most easily tamed[1]; so he chose out the youngest pig in the farm-yard, and approached it with some bread in his hand. “Come here, little pig,” said he; but the pig ran away. “Then I must fetch you,” cried Tommy, and, so saying, he caught it by the leg. The little pig squeaked, and the old sow, coming up, ran between Tommy’s legs, and knocked him down in the mud. “Who did all this mischief?” said Mr. Barlow, coming out that moment from the house. “That foolish pig,” said poor Tommy. “Oh! no,” replied Mr. Barlow, “that foolish boy.”

In doing the above Exercise, make three columns, thus:—

| Answer to the question who? or what? before the Verb, i.e. | Answer to the question whom? or what? after the Verb or Preposition i.e. | |

| WORD. | SUBJECT. | OBJECT. |

| had heard | Tommy | many stories about the taming of wild animals |

| from | — | Mr. Barlow |

| to tame | — | a pig |

Exercise VII.

Write or repeat the Subjects of the italicized Verbs, and the Objects of the italicized Verbs and Prepositions, in the following Exercise:—

A lion, while* quietly sleeping, was surrounded by some mice. They began dancing round him, and at last[2] one young mouse, bolder than* the rest,* jumped up on his body and scampered across his face. The lion awoke with a roar, and the mice ran away: but the young mouse was stopped by the lion’s* paw. “Spare me!” cried she, “and I will never disturb you again.” The lion good-humouredly took his paw off her, and lay down again. Some days afterwards, the lion was caught in a net spread by some huntsmen. In vain[2] he roared and struggled: he found that his struggles only entangled him more in the net, and he cried in despair, “I have no chance of escaping.” Just then, up came the little mouse with a thousand brothers and sisters. To work they fell, gnawing the net, and in ten minutes the lion was released by the mice.

[1] Some of these Verbs, e.g. to tame, have no Subjects; some, e.g. are tamed, have no Objects.

[2] An Adverbial Phrase. See How to Tell, &c., page 79.

21

How to Find whether the Relative is Subject or Object.

In the sentence “Bring the book that pleases you best,” what is the Subject of “pleases?” Perhaps you may ask the question in the usual way, “What pleases?” Answer, “the book.” But this is not right. “Book” is the Object of “bring.” “Bring what?” Answer, “the book.”

Now the same word is never both Object and Subject; so “book” cannot be the Subject of “pleases;” and the real Subject of “pleases” is the Relative Pronoun “that.”

You will generally answer questions of this kind rightly if you remember that the Relative Pronoun[1] is in some sense a Conjunction, so that it joins together two sentences, one of which states, commands, &c., and may be called (Par. 248) the Principal Sentence; while the other—as it is introduced by the Relative Pronoun—may be called a Relative Sentence. If these Sentences are kept quite distinct—the Principal Sentence being first repeated and parsed by itself, and afterwards the Relative Sentence—the pupil will have no difficulty.

[1] How to Tell, &c., page 125.

22 In parsing the Relative Sentence, the Noun or Pronoun for which the Relative Pronoun is used—that is, its Antecedent[1]—should be written in brackets by the side of the Relative Pronoun. Thus, in parsing the Sentences of the next Exercise, write down the Principal and Relative Sentences as follows:—

| Principal | Sentence | . . . | (1) | “The jay was very soon punished for her robbery.” |

| Relative | „ | (2) | “That (jay) robbed the peacocks of their feathers.” |

If the Sentence contains two or three Relative Sentences, they may be taken separately, e.g. in the seventh Sentence of the following Exercise:—

| Principal | Sentence | (a) | (1) | “The girl that I told you of was taught a lesson that she never forgot.” |

| Relative | „ | (a) | (2) | “Who (the girl) counted her chickens before they were hatched.” |

| Principal | „ | (b) | (1) | “The girl was taught a lesson that she never forgot.” |

| Relative | „ | (b) | (2) | “I told you of that (girl.)” |

| Principal | „ | (c) | (1) | “The girl was taught a lesson.” |

| Relative | „ | (c) | (2) | “She never forgot that (lesson).” |

The form who, or whom, will of itself tell you at once whether it is Subject or Object.

In parsing a Relative Pronoun, state—

1. Antecedent.

2. Subject of what Verb, or,

3. Object of what Verb or Preposition.

Exercise VIII.

Parse the Relative Pronouns in the following sentences:—

1. The jay that robbed the peacocks of their feathers was very soon punished for her robbery. 2. The ass that frightened the beasts of the forest was laughed at when he began to bray. 3. The crow dropped the cheese, which the fox immediately snapped up. 4. The lion that spared the mouse was afterwards released by the mouse. 5. The travellers, all of whom had seen the chameleon, could not agree about its colour. 6. Shakespeare tells us that the man that does not love music is fit for murders and conspiracies. 7. The girl that I told you of, who counted her chickens before they were hatched, was taught a lesson that she never forgot. 8. Have you ever heard of Horatius Cocles, who defended the bridge against a host of enemies, and whom the Romans honoured by erecting a statue to his memory?

Write these down as follows:—

| Word. | Antecedent. | Subject of | Object of |

| that | jay | robbed | — |

| which | cheese | — | snapped up |

Find out the Subjects and Objects of all the Verbs in the foregoing sentences.

[1] How to Tell, &c., page 125.

23

The Position of the Relative.

Note that the Relative Pronoun, when used as Object, precedes both the Subject and the Verb. The reason is that the Pronoun, serving the purpose of a Conjunction, has to precede the sentence that it joins to the Principal Sentence.

24 When a Parenthetical Sentence intervenes between the Relative Pronoun and its Verb, that sentence must be carefully separated from the Relative Sentence.

A Parenthetical sentence is a sentence inserted in the midst of another sentence, the latter being complete without the former.

The following are examples of sentences containing Relative Pronouns followed by Parenthetical sentences:—

(1) “Yesterday I met Robert, who—you will hardly believe it—has grown to be six feet high, with a beard reaching to his watch-chain.”

(2) “Yesterday I met Robert, whom (though I had not seen him for ten years) I recognized at once.”

In the following Exercise, the Conjunctional sentences are inserted between parenthetical marks; but the pupil must be prepared to parse the Relative hereafter without the aid of these marks. The following will be found a useful Rule:—

When the Relative is followed by a Conjunction (e.g. “though” above in (2)) introducing a new sentence, leave out this sentence in parsing the Relative.

Exercise IX.

Parse the Relative Pronouns in the following Exercise, stating the Antecedent, and the Verb or Preposition of which each is Subject or Object:—

Once there was a quarrel between the eyes and the nose about the ownership of the spectacles, which (so said the nose) were undoubtedly intended for him and not for his two neighbours the eyes; who, on their part (although they admitted that the nose had a share in the spectacles), yet claimed the largest share for themselves. The two ears, whom both parties accepted as judges, called on the tongue, who was counsel for both, to plead first the cause of the eyes, and then that of the nose. So the tongue began by saying that spectacles that had no eyes to look through them, were of no use; the word “spectacle,” which the Latins used to denote a “place for seeing,” proved, of itself, that the instrument was meant for seeing and not for smelling. The judges, who (though they became rather inattentive while Latin was being quoted) had listened with great patience to the arguments that the tongue brought forward, now desired to hear what the nose had to say. So the tongue, taking that side of the question, which he pleaded remarkably well, called attention to the saddle that was between the two glasses, which, said he, was clearly intended for the nose. He added, with great force, that, if the eyes were closed or even altogether removed, the spectacles would still remain faithfully in their place, but a man that suddenly lost his nose would certainly lose his spectacles as well—“which,”[1] said he, “clearly proves that the nose is the owner of the spectacles. If a dog were placed between two claimants, should we not readily admit that the claimant to whom the dog went would be the rightful owner? My lords, the spectacles, which (because they have no power of motion) sit patiently there between my two clients, would clearly shew you, if they could move, to which claimant they adhered. Cut out the eye, the spectacles will sit unmoved: cast down the nose, the trusty spectacles will immediately follow their fallen master.”

Here the judges, declaring that what[2] they had heard was enough to enable them to arrive at a decision, stopped the counsel, and at once decided in favour of the nose.

Exercise X.

Write or repeat the Subjects and Objects of the Verbs italicized in the last Exercise.

[1] See “Omission of the Antecedent,” Par. 25.

[2] What should be parsed here thus: “what is put for that which; that is the Subject of was; which is the Object of had heard.” The sentence, fully expressed, would run thus: “declaring that that (Subj.) which (Obj.) they had heard was enough,” &c.

25

Omission of the Antecedent.

Tell me the Antecedent of which in the following sentence:—

“The ass in the lion’s skin frightened all the beasts in the forest till he began to bray:* which at once changed their fear into laughter.”

There is no Noun or Pronoun here that can be called the Antecedent of which. Which stands for “the ass’s beginning to bray,” or “the braying of the ass,” or some other words to be supplied from the previous sentence. In parsing which you must say, “which stands for an Antecedent to be supplied, viz. ‘the braying of the ass.’ ”

26

The Omission of the Relative.

When the Relative would be the Object, it is often omitted:—

(1) “The book (that) you sent me is not mine.”

(2) “Where is the parcel (that) I left here yesterday?”

(3) “The message (that) I was sent with was to this effect.”

In Poetry it (Par. 520) is sometimes omitted, even where, if inserted, it would be the Subject:—

(1) “ ’Tis distance (that) lends enchantment to the view.”

Exercise XI.

Write down the Subjects and Objects of the italicized Verbs, and parse the Relatives, as in the last Exercise:—