* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Green Fingers: A Present for a Good Gardener

Date of first publication: 1936

Author: Reginald Arkell (1882-1959)

Date first posted: July 23, 2017

Date last updated: July 23, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170719

This ebook was produced by: Barbara Watson, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

GREEN FINGERS

“A Lovesome Thing—God Wot!”

GREEN FINGERS

A PRESENT FOR A GOOD GARDENER

by

REGINALD ARKELL

pictured by

EUGÈNE HASTAIN

McCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED

PUBLISHERS TORONTO

Copyright, 1936,

By McCLELLAND & STEWART, Limited

All rights reserved—no part of this book may be

reproduced in any form without permission in

writing from the publisher.

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. BY

Quinn & Boden Company, Inc.

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

RAHWAY, NEW JERSEY

I’LL tell you a rather remarkable thing:

The wall of my garden belongs to the King.

And, would you believe it, the rent that I pay,

Is merely a trifle of twopence a day.

My garden, I have to admit it, is small;

But you should see the roses I grow on the wall.

Richmond.

August, 1934.

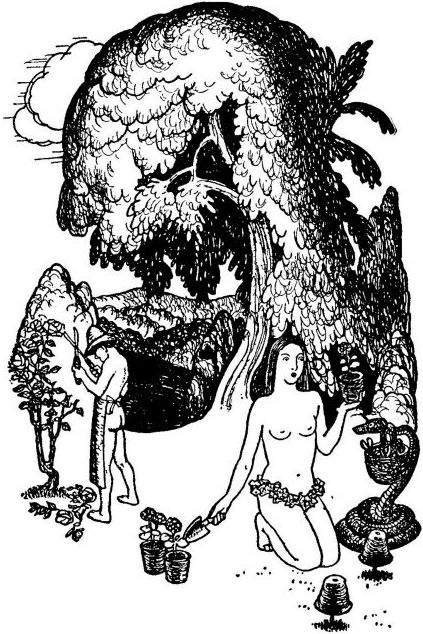

| “A Lovesome Thing—God Wot!” | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

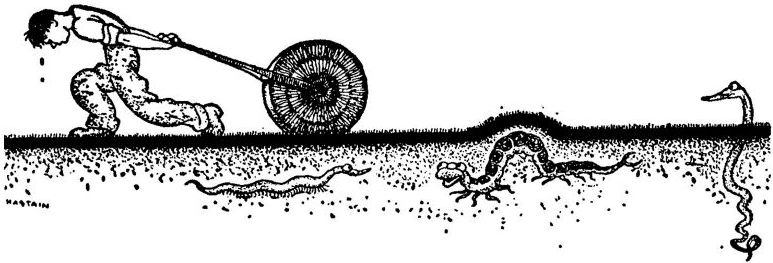

| “I saw Nine Pests” | 28 |

| “Noah was never a Gardener” | 36 |

| “The Garden of Eden was not a Success” | 80 |

| “He likes to lie and smoke his Pipe” | 86 |

THIS book is meant for people who

Can always make their gardens do

Exactly what they want them to;

Who search their borders every night,

And catch their slugs by candle-light;

Who always start at crack of dawn

To dig the plantains from their lawn;

Whose paths are always free from weeds;

Whose plants are always grown from seeds;

Who are most careful not to prune

That standard rose a day too soon;

Who are quite rude to men who sell

Tobacco plants that have no smell;

In fact, to all of you, I mean,

Whose fingers are reputed green

Because you keep your borders clean.

WHAT is a nation?

Just the same

Old garden with

A different name.

It may be here,

It may be there;

We grow the same roses

Everywhere.

It doesn’t matter

What we do,

You are the same as me,

And I, as you.

It doesn’t matter

If short or tall—

We grow the same roses

After all.

Though some are poor

And some are rich,

It doesn’t matter

Which is which.

Though men are brave

And women fair,

We grow the same roses

Everywhere.

It doesn’t matter

Where we sit,

Some choose the gallery

And some, the pit;

Some like the circle

And some a stall—

We grow the same roses

After all.

English or Russian,

French or Scot;

We seem so different—

We are not.

And though we quarrel

Now and then,

We kiss and make it

Up again.

The earth was made

For every one;

We share the same old stars,

The same old sun.

It doesn’t matter,

The world is small—

We grow the same roses

After all.

YOU know, of course, that pleasant rhyme,

“Come down to Kew in Lilac-time”:

I often feel it isn’t fair

To other flowers growing there

So I intend to write a rhyme,

“Come down to Kew at any time.”

Come down to Kew, I mean to say,

When Bluebells paint the woods of May;

Come down to Kew, shall be my tune,

When Roses, rioting in June,

Usher the summer pageant in

Until the Autumn days begin.

Come down to Kew; though days are cold,

The leaves are yellow, brown and gold.

Come down to Kew, I mean to write,

And see the Winter Aconite;

Its little ruff is wet with rime—

Come down to Kew at any time.

LAST winter, when I was in bed with the ’Flu

And a temperature of a hundred and two,

I was telling the gardener what he should do.

You must keep the Neurosis well watered, I said.

Be certain to weed the Anæmia bed.

That yellow Myopis is getting too tall,

Tie up the Lumbago that grows on the wall.

Those scarlet Convulsions are quite a disgrace,

They’re like the Deliriums—all over the place.

The pink Pyorrhœa is covered with blight,

That golden Arthritis has died in the night.

Those little dwarf Asthmas are nearly in bloom—

But just then the doctor came into the room.

THERE once was a lady, divinely tall,

Who lived high up in a castle wall,

And longed to be lord in her husband’s hall.

A troubadour chanced to be passing by,

As the lady looked down from her casement high.

He stood at the foot of the castle wall,

And sang to the lady, divinely tall,

Who longed to be lord in her husband’s hall:

“A holy father, from over the sea,

Has brought me this cutting of Rosemary.

“Plant it carefully by the wall.

If it grows a tree, both healthy and tall,

You shall be lord in your husband’s hall.”

The lady listened, and so it befell.

She wore the doublet and hose as well.

And even to-day

There are cynics who say:

The wife who means to master her man

Will trot down the path with her watering-can—

And if you follow her, you will see

She always waters her Rosemary.

THE Queen was in the garden,

A-smelling of a rose.

She started for to pick one,

To please her royal nose;

When up speaks the gardener:

“You can’t have none of those.”

The Queen was in the green-house,

A-looking at a grape.

She started to admire one:

Its colour, bloom and shape.

When up comes the gardener,

Before she could escape.

The Queen is in the parlour

A-slamming of the door;

And writing of a letter

Because she feels so sore:

“I don’t want no gardener;

So don’t come back no more.”

SOME men make money

As bees make honey;

They spend their lives

In filling hives—

I think that’s funny.

I’m not a busy bee;

No honest toil for me,

And when my Banker,

Each time I meet him in the street,

Gets frank and franker,

He does not worry me—

I have a recipe;

I find some busy bee

Who has the sense to be

Friendly to me.

MY next-door neighbour, Mrs. Jones,

Has got a garden full of stones:

A crazy path, a lily pond,

A rockery, and, just beyond,

A sundial with a strange device,

Which Mrs. Jones thinks rather nice.

My next-door neighbour, Mrs. Jones,

Puts little plants between the stones.

They are so delicate and small

They don’t mean anything at all.

I can’t think how she gets them in,

Unless she plants them with a pin.

My next-door neighbour, Mrs. Jones,

Once asked me in to see her stones.

We stood and talked about a flower

For quite a quarter of an hour.

“Where is this lovely thing?” I cried.

“You’re standing on it,” she replied.

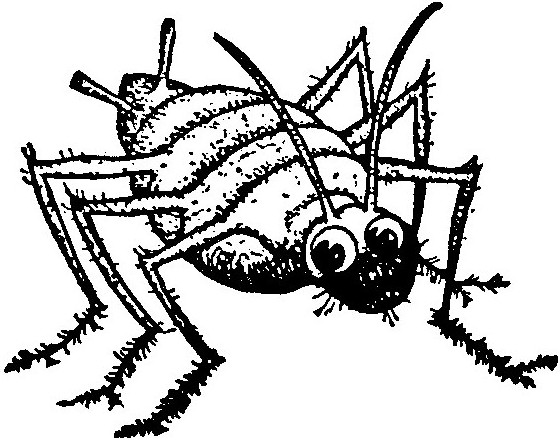

OF every single garden pest,

I think I hate the Green Fly best.

My hate for him is stern and strong;

I’ve hated him both loud and long.

Since first I met him in the Spring

I’ve hated him like anything.

There was one Green Fly, I recall;

I hated him the most of all.

He sat upon my finest rose,

And put his finger to his nose.

Then sneered, and turned away his head

To bite my rose of royal red.

Next day I noticed, with alarm,

That he had started out to charm

A lady fly, as green in hue

As all the grass that ever grew.

He wooed, he won; she named the night—

And gave my rose another bite.

Ye gods, quoth I, if this goes on,

Before another week has gone,

These two will propagate their kind,

Until, one morning, I shall find

A million Green Fly on my Roses,

All with their fingers to their noses.

I made a fire, I stoked it hot

With all the rubbish I had got;

I picked the rose of royal red

Which should have been their bridal bed;

And on the day they twain were mated

They also were incinerated.

I THINK that I shall never be

So popular that I shall see

A Passion Flower named after me.

Though famous people of to-day,

Are honoured in this curious way.

In Carter’s Catalogue, I see

That Mary Pickford is a Pea.

Jack Hobbs, Lord Beatty, Nurse Cavell,

And Sonny Boy, are Peas as well.

When they name something after me,

I only hope that I shall be

A Passion Flower and not a Pea.

THE Missus seems

To think it fun

To work from dawn

To set of sun,

And do two jobs

Instead of one.

The Missus loves

To rush around,

And do each job

That can be found.

She covers quite

A lot of ground.

I can’t think why

She works that way,

For, after all,

She gets no pay

And never has

A holiday.

THERE is a lady, sweet and kind

As any lady you will find.

I’ve known her nearly all my life;

She is, in fact, my present wife.

In daylight, she is kind to all,

But, as the evening shadows fall,

With jam-pot, salt and sugar-tongs

She starts to right her garden’s wrongs.

With her electric torch, she prowls,

Scaring the Nightjars and the Owls,

And if she sees a slug or snail

She sugar-tongs him by the tail.

Beware the pine-tree’s withered branch,

Beware the awful Avalanche—

And Slugs, that walk abroad by night,

Beware my wife’s electric light.

PREPARE the ground in Autumn

And sprinkle lime about;

Give the soil time to settle

Before you plant them out.

The trenches should be three feet deep

And also two feet wide,

With bone-meal, soot and farm manure

Mixed with the soil inside.

You’ll find that mid-September

Is the proper time to start:

Thin out the plants until they stand

Just half a foot apart.

Be careful how you drain the soil,

Put sand along each row—

But, Gladys, she just shoves them in,

And, golly, how they grow!

I ALWAYS thought it was a pity

That dwellers in our garden city

Had not seen fit to emulate

The owner of some great estate

Who throws his garden open wide

That every one may walk inside.

So I suggested to some friends

That we should try to make amends:

It seemed the least that we could do,

To throw our gardens open, too;

And let the Garden City see

Just what a garden ought to be.

Two weeks before the fateful day,

My Calliopses passed away.

And e’er another week was past,

My pet Gloxinia breathed her last.

While, crowning tragedy of all,

The Flowering Peach began to fall.

And so I fled—I could not face

Humiliation and Disgrace.

A MAN, as mad as any hatter,

Once said that mud is misplaced matter;

And he would argue, I suppose,

A weed is any plant that grows

Outside its own especial sphere—

I trust I make my meaning clear.

And you are wondering, no doubt,

What all this bother is about.

While walking down my garden way,

I found a buttercup to-day;

A lovely thing it was, indeed,

And yet, in theory, a weed.

“Alas, poor Buttercup,” I said,

“Already you’re as good as dead.

If Mary sees you, Buttercup,

Your number is distinctly up.

What can be done?” Just then, my wife

Swooped forward with her pruning-knife.

“Observe,” I cried, “dear wife of mine,

Observe this Lesser Celandine,

The fairest flower by poets sung,

In every land and every tongue . . .”

But Mary merely shook her head:

“It is a Buttercup,” she said.

A GARDEN is a lovesome thing—

When it starts blooming in the Spring.

The daffodil, the snowdrop white,

The dainty Winter Aconite. . . .

And just as it is going strong,

The Woolly Aphis comes along.

Wire Worms and Weevils think it fun

To eat your annuals one by one.

Until the Caterpillars start

To break your horticultural heart.

Go, take a flat or buy a yacht.

A garden is a lovesome thing—God wot!

ROCK Gardens are really ridiculous things,

Like peaches with pepper and donkeys with wings.

You make out a list of the plants you must buy,

You stick them in pockets, and most of them die.

And if you are foolish enough to suppose

You can keep them alive with the aid of a hose—

What dire disillusion awaits you next day:

The water is certain to wash them away.

“HAVE you forgotten, Curly Head,

That night beside the Parsley Bed?”

“I have forgotten it,” she said.

“Do you recall the word you spoke

That night beneath the Artichoke?”

“Oh, that,” said she, “was just a joke.”

“Have you forgotten how you cried

Among the Onions?” I sighed.

“Well, do you blame me?” she replied.

I spoke of sympathetic scenes

Between the Parsnips and the Beans;

But when I called her my Shalot

And said what Celery I got—

She told me not to talk such rot.

Ah, Kitchen Garden, soaked in rain

I ne’er shall see her like again.

THE old red wall

Seemed terribly tall

To children at their play;

Its top, so high

That it reached the sky,

Seemed ever so far away.

It was built of brick,

So terribly thick

That nothing could make it fall;

Each holiday time

We longed to climb

To the top of the old red wall.

The world seems strange;

The maps all change

And Empires pass away.

But the old red wall

Doesn’t worry at all,

It dreams of a child at play.

And the child come back

On a well-worn track,

Has grown so terribly tall:

He can sit and sigh

For the days gone by

On the top of the old red wall.

Visitor:

YOU see that summer-house, which stands

Across the road from “Happylands”?

I have been wondering a lot

About the chimney it has got.

Is it a summer-house, or not?

Rustic:

Well, now you mentions it to me,

That be a caution, so it be.

I’ve lived here eighty year or more

And never thought of that before.

It be a caution, to be sure.

Gardener:

The gazebo, Miss? They used to wait

For coaches that were always late,

On what was once a busy track,

And so it had a chimney stack—

Those coaching days are coming back. . . .

And so they gossip and explain,

While I, behind the window-pane,

Search Memory’s ever-shifting sands

For laughing eyes and little hands—

The girl who lived at “Happylands.”

WHENEVER I met the Tomato Man,

I took to my heels and away I ran.

He used to stand at his cottage door

Oozing tomatoes from every pore.

I always felt that the back of his head

Was like a tomato—his cheeks were red,

And he smoked a pipe, when I stopped to talk,

That was rather like a tomato stalk.

Tomato Men are the same to-day;

You can always tell them a mile away:

They lean on the fence, they smoke a pipe

And are just a little bit over-ripe.

MUMMY has a garden

That is all her very own;

She often goes to sit there

When she wants to be alone.

When she feels un-so-ciable,

She won’t come out to play,

And if I try to peep at her

She makes me run away.

Mummy’s little garden

Has an arbour and a seat.

Sometimes she lets me sit there

As a most es-pe-cial treat.

Nobody must talk to her

Until ’tis time for tea.

I wonder what she thinks about?

I wonder if it’s me?

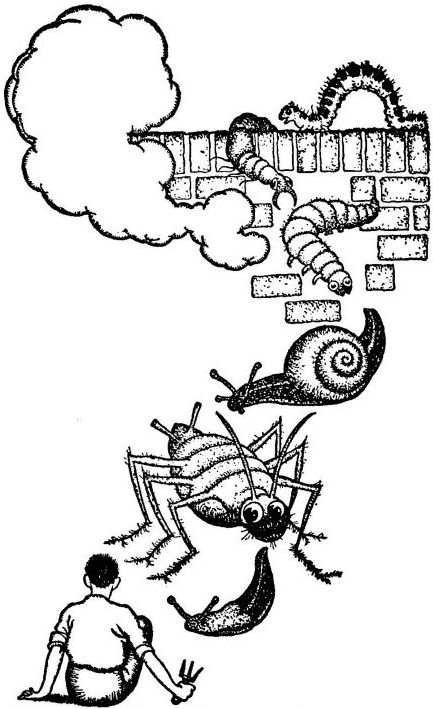

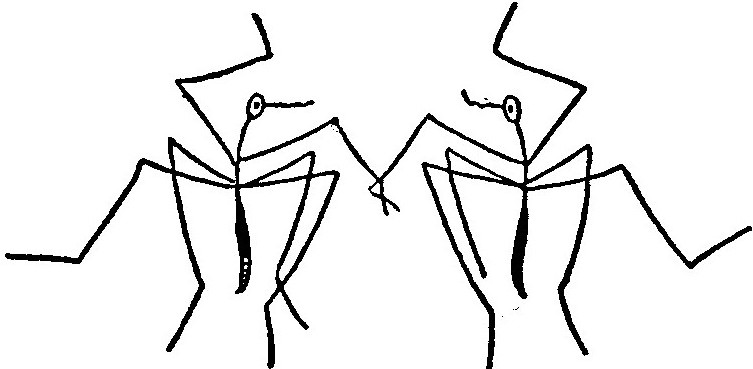

“I saw Nine Pests”

AS I sat under a poplar tall,

I saw nine pests come over the wall.

I saw nine pests come wandering by;

A slug, a snail and a carrot fly.

I saw nine pests descending on me:

Wire-worm, weevil and radish flea.

I saw nine pests, a depressing sight:

Pear midge, mildew and apple blight.

Nine garden pests came over the wall,

And the woolly aphis was worst of all.

THE Squire has got a greenhouse,

Where Easter lilies grow.

They stand beside the altar,

And make a lovely show.

While simple snowdrops that I send

Are hidden at the other end.

When I have got a greenhouse,

My flowers will be so fine,

The lilies at the altar

Will every one be mine;

And all the flowers that others send,

Will decorate the other end.

WHEN my first book has been published, dear,

I’ll take a cottage not far from here—

A little old place where roses climb

Smelling so sweet in the summertime;

And every morning, from ten till one,

I’ll scribble, and when my work is done

We’ll drift together, just me and you

(Bother the grammar), in our canoe.

I will paddle and you will steer

When my first book has been published, dear.

GOOD gardeners all will deprecate

The man who shuts his garden gate.

My garden gate is open wide,

And any one can walk inside—

Except, of course, the ass who says:

“My lupins have been out for days.”

THE old house stands to-day

As when you went away:

The shaded porch, the poplar tall,

The Hollyhocks along the wall.

The shrubbery,

With hammock swinging drowsily.

The writing on the window-pane:

“I go, but I return again.”

The corner, too,

In which the Christmas roses grew.

Nothing has altered, as you see,

Yet everything is changed for me.

OLD-FASHIONED gardens, underneath the trees,

Cowslips and columbines are nodding in the breeze;

Lilac and lavender so sweet and shy,

Bring back the memories of days gone by.

Old-fashioned gardens, waking with the dawn,

Daisies and daffodils are laughing on the lawn;

Harebells and hollyhocks that grow so high,

Bring back the memories of days gone by.

A GARDEN is a funny thing;

However much you try,

Some plants will never seem to grow,

They fade away, and die.

I cannot say why this should be:

Some flowers will never grow for me.

I sometimes think, in Paradise,

That garden in the sky,

The borders will be full of blooms,

And none will ever die.

And in that garden I shall see

The flowers that would not grow for me.

“Noah was never a Gardener”

NOAH was never a gardener,

Or he would have said to Shem:

“When the animals walk in, two by two,

Be certain that Japheth and Ham and you

Stop those horrible wire-worm from getting through—

I couldn’t be plagued with them.”

Columbus wasn’t a gardener,

Or, standing on deck, one night,

He’d have turned his vessel the other way;

He wouldn’t have gone to the U.S.A.,

And our orchards would never have known to-day

That foul American blight.

I KNEW a girl who was so pure

She couldn’t say the word Manure.

Indeed, her modesty was such

She wouldn’t pass a rabbit-hutch;

And butterflies upon the wing

Would make her blush like anything.

That lady is a gardener now,

And all her views have changed, somehow.

She squashes green-fly with her thumb,

And knows how little snowdrops come:

In fact, the garden she has got

Has broadened out her mind a lot.

MY lawn is very, very old;

Three hundred years, at least, I’m told.

It saw the Roundheads marching through,

And heard the cheers for Waterloo.

A man admired my lawn, to-day;

And how it laughed to hear him say:

“Your bit of turf looks nice and flat.

Next year, I’ll have a lawn like that.”

AND did the honeysuckle climb

On Eden’s arbours, cool and green?

And was the lesser celandine

In Eden’s pleasant pastures seen?

And did the yellow buttercup

And cowslip gild some golden glade?

And did the bluebell and the rose

Bloom in the garden He had made?

I will not rest by day or night,

Until the tripper’s thoughtless hand

Has left some flowers for our delight

In England’s green and pleasant land.

I KNOW a charming woman,

And every time she calls

She leaves my carpet on the floor,

My pictures on the walls.

She doesn’t steal my silver,

Or ask me for a loan;

She doesn’t use my fountain-pen—

She always brings her own.

But shew her in your garden

The treasures you have got,

And, if you turn your head away,

She’ll pinch the blooming lot.

WHEN I was very young indeed

They always wanted me to weed

The garden path, and mow the lawn—

I started at the crack of dawn

And carried on till dewy eve:

Or, so I made myself believe.

To-day, with my increasing weight,

My heart is in an awful state,

And stooping down to pull a weed

Might make me very ill indeed.

Such simple tasks, to tell the truth,

Are still the privilege of youth.

ONE day, in early Spring,

I placed a special order

For very special seeds

For a very special border;

Then wrote a label, with great care,

To tell me what the flowers were.

A month or two went by;

I saw with consternation

That not a single seed

Had arrived at germination.

And so the label I had penned

Became a tombstone in the end.

MARTHA had a garden,

And she tended it with care.

She took a pail and watered it,

Each slug or snail—she slaughtered it;

There were no green-fly there.

She scratched and scraped it with a hoe;

There were no seeds she didn’t sow,

And yet her garden wouldn’t grow.

Mary has a garden

Which is full of happy flowers.

She doesn’t do a thing in it

But walk about and sing in it

For hours and hours and hours.

She never weeds and never hoes,

And yet her garden always grows—

Because she loves it, I suppose.

A NUMBER of people are perfectly willing

To show you their grounds if you pay them a shilling;

And, being a bit of a gardening fan,

I see all the gardens I possibly can.

I wander, with crowds of inferior vassals,

Through acres of gardens of Courts and of Castles;

And here is a point I can never make out:

The owner is seldom seen standing about.

I fancy I hear the head gardener say:

“Now, listen, I open the garden to-day,

And, as we are sure to be thick on the ground,

I can’t have the family hanging around.”

WHEN my work is ended,

And finished for the day;

When I’ve swep’ the garden

And put my tools away;

Then the lady prowls around,

Sticking seeds into the ground.

When the sun starts shining,

Them seeds they germinates;

And up comes the rubbish

A proper gardener hates:

Nasty, stupid little seeds

Turning into horrid weeds.

First them filthy fox-gloves

Clutters up the view;

Stinking periwinkle

And creeping jenny too—

When the lady’s back is turned,

All that lousy stuff gets burned.

HE always comes at crack of dawn

And always starts to mow the lawn

When you are only half awake—

“Oh, stop that noise, for goodness’ sake!”

You always pay him by the hour,

And if you want to pick a flower

To make a nosegay or a wreath,

He snarls at you and shows his teeth.

There are some things he likes to do,

And some he likes to leave to you—

While he is putting in the seeds,

You will be pulling up the weeds.

THERE are some people that I hate.

They gather round my garden gate,

Discussing, till I’m sick and sore,

The Lady Who Was Here Before.

They stand and whisper: “What a shame.

I’m thankful Mrs. What’s-her-name

Is dead, poor dear, and doesn’t know.

She used to love her garden so.”

“They’ve thrown away those lovely rocks

She got from Cheddar—and the Box

She planted round her heart-shaped plots

Of Heartsease and Forget-me-nots.”

“They’ve moved her Salpiglossis bed,

And planted Primulas instead.

They’ve put an ugly Poplar tree

Where that nice Privet used to be.”

They’ll get me so upset, some day,

That I shall spring at them, and say:

This is my garden. GO AWAY!

A FUNNY old man just knocked at the door,

I’ve noticed him hanging about before.

He said that he wanted to come inside,

And see the old garden—before he died.

Then he gives me a sort of worn-out look,

And he starts to cry—Can you beat it, Cook?

“Do you know the Master or Mistress?” I said.

“I don’t,” said he, with a shake of his head;

“I left the district some years ago,

There’s nobody left that I used to know:

But I thought, somehow, I would like to look

At the place again”—Can you beat it, Cook?

I just stood there, and I shook my head.

“The Master and Missus is out,” I said.

“As likely as not I should get the sack

If they found you about when the car came back.

You take my advice and you sling your hook.”

And sling it he did—Can you beat it, Cook?

WHEN I select some special bloom

To decorate my drawing-room,

I wonder, in my artless way,

What all the other flowers say.

Do lesser blossoms, which remain

To face the sunshine and the rain,

Reflect with envy and with pride

Upon their fellow who has died?

It may be so. And yet, again,

Perhaps they sorrow for the slain,

And murmur, as I wander past:

“Poor Emily has gone at last.”

THERE was a Prince of Austria,

His coat was royal red;

The finest Prince of Austria

In all the tulip bed.

“Here stands a Prince of Austria,”

The name-plate should have said.

Alas, that Prince of Austria,

He stood, in sad disgrace.

They thought he was a Crimson King

When plotting out the place.

When the head gardener came along,

You should have seen his face.

IF I could be a boy again;

A boy of eight or nine or ten,

Why then—

I’d buy a barge in Brentford town,

And on the river, old and brown,

Go floating down.

The tide would bear me on my way,

Until I came, at close of day,

To countries far away;

Where lovely girls their flowers would fling

While dancing round me in a ring—

And I would be their king.

IN winter, when she goes to town,

She dons a dainty silken gown.

Her heels are high as Babel’s tower,

She is as fragrant as a flower.

While unconsidered moments pass,

She stands before her looking-glass,

To paint the lily, gild the rose

And put more powder on her nose. . . .

But when the sun is shining down,

She doesn’t give a thought to town.

Wearing a cotton over-all,

She trains the roses on the wall.

Her shoes have got the flattest heels;

Beside the lily-pond she kneels,

And, as the golden moments pass,

She needs no other looking-glass.

She doesn’t think about her clothes,

There is no powder on her nose. . . .

THE Master knows his proper place,

And never picks a rose;

The Missus cuts a basketful

Beneath my very nose.

The Master, he’s a gentleman

And knows his limitations;

The Missus, on the other hand,

Plays hell with my carnations.

The Master has the common sense

To leave a man alone;

The Missus muddles round the place,

As if it was her own.

The Master says: “Good morning, John;

I hope you’re feeling nicely.”

The Missus says: “Your time to start

Is eight o’clock, precisely.”

It makes me go all hot and cold,

To think such things should be.

Why is it that the likes of her

Should rule the likes of me?

Why should she always make me feel

I has to beg her pardon

Each time she ever shoves her nose

Inside my kitchen garden?

WHILE sitting by the lake at Kew;

A thing I very often do;

I thought that I would like to sing

A little song about the Spring:

My dear, I bring to you

Forget-me-nots of blue;

No mournful lilies guard your sleep,

Nor rosemary, nor rue;

But early violets from the brake,

To greet you when you wake.

I sang my little song of Spring;

I sang and sang, like anything;

Until a dabchick darted out

To see what it was all about.

My dear, I place with care

Beside your pillow there

A daffodil from Carrow Hill,

None finer anywhere.

These cowslips hold the morning dew—

I picked them, dear, for you.

The dabchick gave his tail a shake,

And hurried, with a widening wake,

Across the water, cool and green,

To tell his friends what he had seen.

WHAT is a garden?

Goodness knows!

You’ve got a garden,

I suppose:

To one it is a piece of ground

For which some gravel must be found.

To some, those seeds that must be sown,

To some a lawn that must be mown.

To some a ton of Cheddar rocks;

To some it means a window-box;

To some, who dare not pick a flower—

A man, at eighteen pence an hour.

To some, it is a silly jest

About the latest garden pest;

To some, a haven where they find

Forgetfulness and peace of mind. . . .

What is a garden?

Large or small,

’Tis just a garden,

After all.

I HAVEN’T got a greenhouse;

I don’t see why I should.

I can’t afford a greenhouse;

I wouldn’t if I could.

Why people build a greenhouse,

I’ve never understood.

You’ll find inside a greenhouse

Each strange exotic thing

That shuns our English sunshine

And fears our English spring—

An oak without an acorn,

A lark that cannot sing.

I’d rather have the flowers

Our simple fathers knew,

Than these new-fangled blossoms

Of every shape and hue—

I’d rather have a skylark

Than a parrot at the Zoo.

MISS LETTUCE is a débutante,

Deserving of a ballad;

She does not quickly run to seed,

Is very popular indeed

In any social salad.

In June, when she is coming out,

Miss Lettuce can resist the drought.

Miss Lettuce has the biggest heart

In all the kitchen garden.

Be sure to pick her in her prime,

For if she isn’t caught in time

Her heart is apt to harden.

You’ll find her at her best, I mean,

When she is young, and fresh—and green.

WE worshipped at the wicket,

Till the sporting legend grew

That the playing-fields of Eton

Paved the way to Waterloo;

And to say “It isn’t cricket”

Was the ultimate taboo.

To call a man a hero,

Just because he wields a bat,

Would savour in these testing times

Of talking through one’s hat.

Let’s say “It isn’t gardening”

And let it stop at that.

THE lawn is like a lump of lead,

Your garden has been put to bed

And you have locked the potting-shed.

The snow has just commenced to fall,

The world is wrapped in winter’s pall.

There are no signs of life at all.

When, like a star which shines at night,

That miracle of green and white—

A Christmas Rose creeps into sight:

A lonely herald of the Spring,

Of happy birds that nest and sing,

Of butterflies upon the wing,

Of fairies dancing in a ring—

And all that sort of thing.

BETWEEN the lilac and the rose—

The drifting tide of blossom flows;

An ecstasy of pink and white

Scenting the quiet aisles of night

As though the branches of the trees

Had caught the foam of coral seas.

The world is young, both man and maid

March in its eager cavalcade.

In city street and scented lane,

The golden age is born again;

And there is happiness to win,

For summer is a-coming in.

THE Director of Kew

Is a gentleman who

Knows more about flowers than my grandmother knew;

And she, if the stories about her are true,

Knew more about gardens than any one knew.

This speaks rather well

For the gentleman who

Has charge of the wonderful

Gardens at Kew.

SIR BUMPUS BULKELEY—

May his tribe decrease—

Awoke, one afternoon,

From dreams of peace;

To see a stranger

Looking through the gate

That kept the common herd

From his estate.

Sir Bumpus did not fly into a passion

(One deals with cads in quite another fashion);

He merely looked the fellow up and down—

(A common person, from the market town)

And said: “Excuse me, but may one elicit,

Without offence, the object of this visit?”

“Certainly,” said the stranger, with a yawn.

“I stopped to count the plantains on your lawn.”

AT Kempsford in Gloucestershire

The Thames is small, but very clear;

Clear as crystal and so small,

It wouldn’t float a boat at all.

Just a tiny, tiny stream,

Only old enough to dream.

Dreaming dreams of yester-year,

When some gallant cavalier,

Passing by the ford we knew,

Picked forget-me-nots of blue—

As we used to do.

The cavalier is dead and gone,

But still the stream goes dreaming on.

IT is a most exciting thing,

To take a garden in the Spring:

To wonder what its borders hold;

What secrets lurk beneath the mould?

What kinds of roses you have got;

Whether the lilac blooms, or not?

Whether the peach tree, on the wall,

Has ever had a peach at all. . . .

It is a most exciting thing,

To take a garden in the Spring;

And live in such delicious doubt,

Until the final flower is out.

“THE early Hopes which set our hearts astir,

Turn Ashes,” said some old Philosopher:

“And, one by one, fade as the morning mist,”

Croaked, through his beard, that Ancient Pessimist.

It isn’t true. When we were very small,

We loved a yellow Rose upon a wall;

The scent of Sweet Briar and of Mignonette—

We loved them long ago, we love them yet.

Some early hopes of ours, alas, are dead;

They turned to ashes, as the Cynic said:

But, planted in the country or the town,

You’ll find a garden never lets you down.

1471

WHEN Margaret slept at Owlpen

On the Eve of Tewkesbury fight,

Roses grew in the garden,

Rose of red and white—

The red rose of Lancaster

And the Yorkist rose of white.

1934

Here, while the ghosts of Owlpen

Walk in the quiet night,

Roses bloom in the garden,

Roses of red and white—

The red rose of Lancaster

And the Yorkist rose of white.

THEY have stolen the scent

From the damask rose;

It flatters the eye

And insults the nose.

IN Devonshire, the diamonds

That glisten on the grass

Are smaller than the diamonds

Behind these panes of glass.

You can keep your diamonds,

Which people place in pawn,

And I will have the diamonds

That laugh upon the lawn.

A GARDEN should be rather small

Or you will have no fun at all.

It should be sheltered from the cold:

As full of flowers as it can hold.

The sun-dial, standing on the lawn,

Should bear these words: I Wake at Dawn.

A sweetly scented border, set

With rosemary and mignonette.

A garden path of living green—

None of that crazy stuff, I mean.

If these instructions you obey,

You will be happy every day.

IN Oxford meadows, long ago,

I wandered in a dream

Among those little purple flowers which grow

Beside that silver stream.

And, later, talking to a don

Of sad and solemn mien

I happened, idly, to remark upon

Wild tulips I had seen.

Alas, we are no longer friends,

Though he is living still:

There’s a fritillary rough-hews our ends

Re-shape them how we will.

MRS. MYOSOTIS

Sits under the wall

In a little blue bonnet

And a green over-all.

She’s like that old woman

Who lived in a shoe:

She has so many children

She doesn’t know what to do.

Each in a blue bonnet

And a green over-all.

I’m sure we shall never

Find room for them all.

We shall have to throw some of them

Over the wall.

WHEN, with my garden hose,

I slake the sod,

I am as one of those

Who walk with God.

I am His April shower,

His summer rain;

I cause the drooping flower

To bloom again.

O, thirsting sod,

Fear not that brazen sky;

I am your god—

Until His springs are dry.

IT was a simple country child

Who took me by the hand:

Why English flowers had Latin names

She couldn’t understand.

Those funny, friendly English flowers,

That bloom from year to year—

She asked me if I would explain,

And so I said to her:

Eranthis is an aconite

As everybody knows,

And Helleborus Niger is

Our friend the Christmas rose.

Galanthus is a snowdrop,

Matthiola is a stock,

And Cardamine the meadow flower

Which you call lady’s smock.

Muscari is grape hyacinth,

Dianthus is a pink—

And that’s as much as one small head

Can carry, I should think.

She listened, very patiently;

Then turned, when I had done,

To where a fine Forsythia

Was smiling in the sun.

Said she: “I love this yellow stuff.”

And that, somehow, seemed praise enough.

OUR station-master’s garden is particularly fine,

It’s rather like those landscapes that they hang upon the line;

And all the railway passengers put out their heads and say:

“The station-master’s garden’s looking very bright to-day.”

Our station-master’s garden is the favourite on the rails,

And all the railway passengers to Paddington or Wales,

Smile across at one another, in their carriages, and say:

“The station-master’s garden’s looking very bright to-day.”

THERE is a village by the Seine

I haven’t seen for years.

I go again and yet again

To see that village by the Seine—

It always disappears;

Its houses hidden in a mist

Of opal and of amethyst.

“The Garden of Eden was not a Success”

BEVERLEY NICHOLS

And Marion Cran

Hadn’t been born

When the world began.

That is the reason,

I’m bound to confess,

The Garden of Eden

Was not a success.

I HEARD an ancient gossip say:

Upon the twenty-first of May,

The man who owns a garden plot

Should count the blossoms he has got.

If he should find their number odd,

His crimes will cry aloud to God;

But if their number should be even,

Then all his sins shall be forgiven.

But why the twenty-first of May

Should always be the vital day

That ancient gossip didn’t say.

YOU’VE been, at Bluebell time, to Kew;

And, like the lady at the Zoo,

When first she saw a kangaroo,

You’ve said: “Of course, it isn’t true.”

THE Spring comes in

When no one is looking;

You’re lying in bed

With a cold in the head,

Or you may be cooking;

Putting new covers upon the chairs—

When, suddenly, taking you unawares,

A thrush in the orchard starts to sing

And, once again, you have missed the Spring.

I NEVER know which.

Jasmine sounds terribly, terribly rich.

And Jessamine, somehow, sounds terribly poor;

I picture her over a cottager’s door,

Her head in the thatch and her feet in a ditch,

While Jasmine prefers a more orthodox pitch.

Jasmine or Jessamine?

I never know which.

“He likes to lie and smoke his Pipe”

A HUSBAND is the sort of man

Who tries to help you all he can;

But, somehow, never quite succeeds

In doing what the garden needs.

He likes to lie and smoke his pipe,

And wonder if the pears are ripe;

Or else he’ll smell the mignonette

Before he lights a cigarette.

But, ask him if he’ll clear the dump,

Or carry water from the pump,

And he will find some fine excuse—

In fact, he’s not the slightest use.

LUPINS, like lots of society leaders,

Are rather important and very gross feeders.

Daisies are neat little servants in villas,

Who wait upon tulips, narcissi and scillas.

Snowdrops are choirboys—such emblems of purity

May lose this effect on approaching maturity.

The Poppy—a flapper, who’s “almost a lydy,”

A bit highly-coloured and very untidy.

Lilies are like Miss Elizabeth Arden

(Or Helena Rubinstein—begging her pardon);

And Weeds are the tramps in a gentleman’s garden.

YOU’VE never finished working in a garden,

Until ’tis time for you to go to bed.

You’re either squirting soapsuds on the roses,

Or picking all the pansies that are dead.

You’re either tying up that new delphinium,

Or hammering a nail into the wall—

But any proper gardener will tell you

That waiting is the hardest job of all.

THE band is playing a waltz refrain,

I hold you, dear, in my arms again.

And none will stare,

For none will care—

Each one is deep in his own affair.

The floor is right,

The band is right.

They have seen two lovers before to-night.

Come into the garden,

Never mind the band;

Never mind the dancers,

They will understand.

There’s a fellow feeling

Through the music stealing—

Come into the garden,

Never mind the band.

ONE day, I was passing the snapdragon bed,

You will find in Hyde Park, when a snapdragon said:

“Well, here’s a ridiculous state of affairs,

These chaps are so anxious to charge for the chairs

That no one has noticed the stupid mistakes

This foolish and fat-headed gardener makes.”

I stopped, and addressing the snapdragon bed:

“Excuse me, but what is the matter?” I said.

“I may not be much of a gardening fan,

But tell me what’s wrong and I’ll help, if I can.

Your troubles can all be adjusted, no doubt.

Suppose you explain what you’re worried about.”

“The trouble is this,” a pink snapdragon said:

“We fellows are pink and this fellow is red.

If you were a snapdragon, what would you think

Of a blossom of red in a border of pink?”

The point was too clear to be argued at all,

So I threw the red snapdragon over the wall.

SOME blossoms jealously refuse

To let their scent take wing;

You have to pick a damask rose

And hold it tightly to your nose

Before you smell a thing.

The scent of honeysuckle floats

Like music on the air.

It does not hold its perfume fast,

And, as you wander idly past,

It tells you it is there.

BEFORE you put this little book away,

Please promise me that you will never say:

“You should have seen my garden yesterday.”

Mis-spelled words and printer errors have been fixed.

Inconsistency in hyphenation has been retained.

[The end of Green Fingers: A Present for a Good Gardener by Reginald Arkell]