* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Canada

Date of first publication: 1907

Author: William Wilfred Campbell (1860-1918)

Date first posted: July 21, 2017

Date last updated: July 21, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170716

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

CANADA

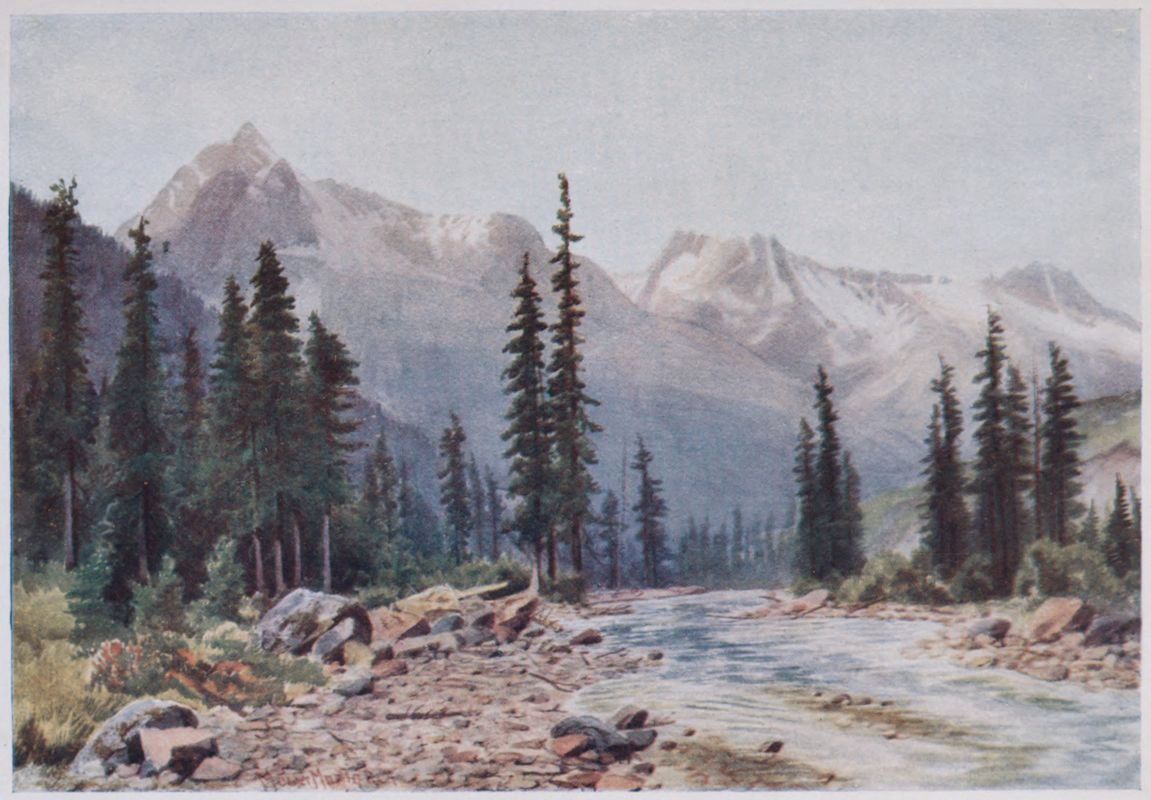

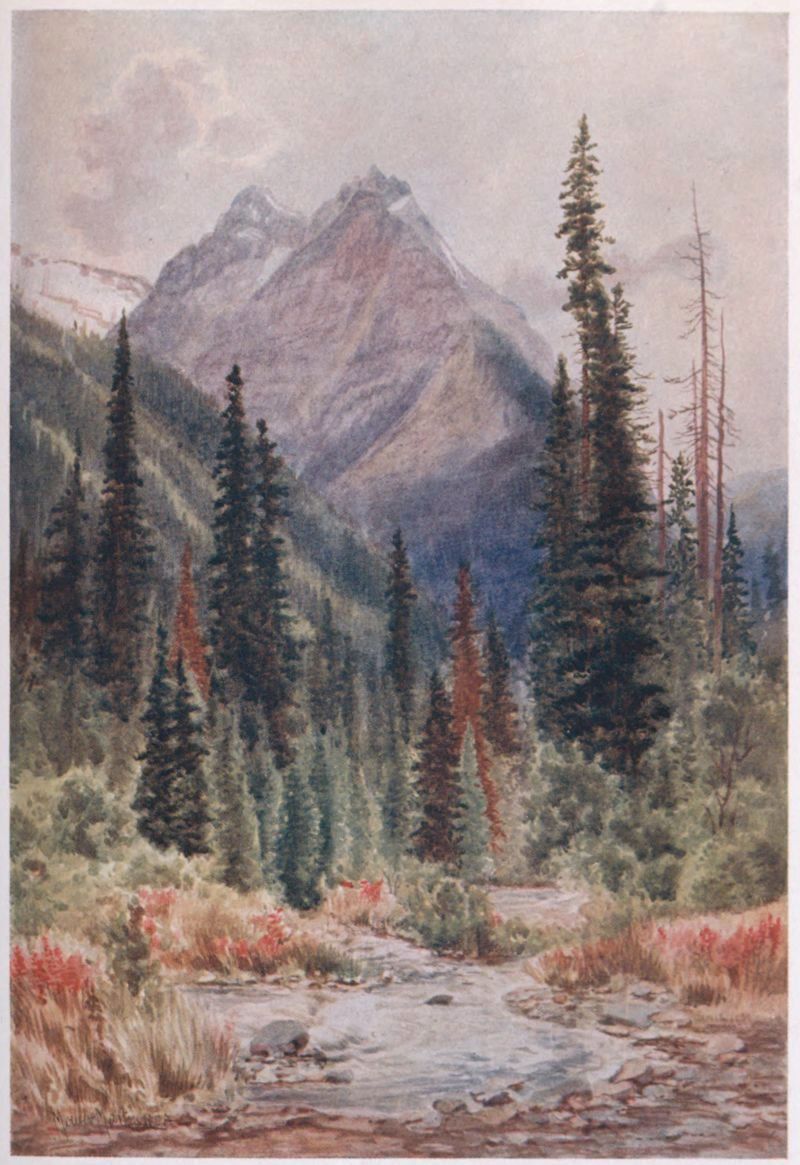

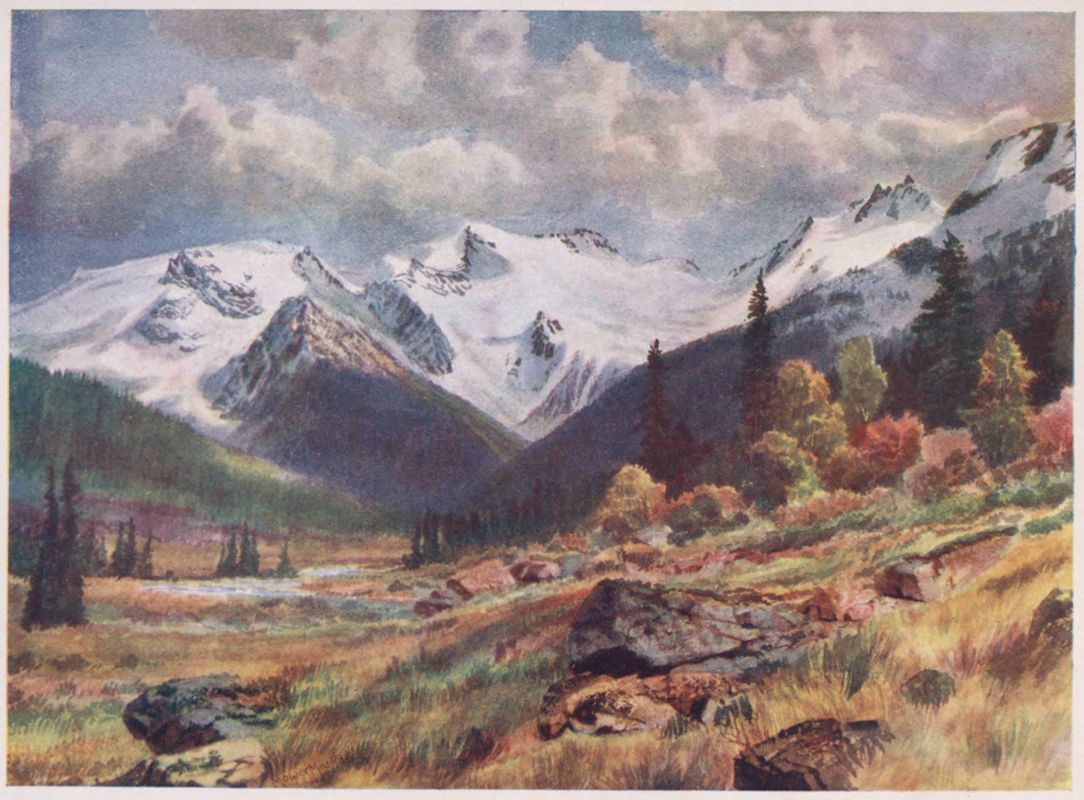

ILLECILLEWAET BELOW SIR DONALD

CANADA

PAINTED BY T. MOWER MARTIN R.C.A.

DESCRIBED BY WILFRED CAMPBELL LL.D.

PUBLISHED BY A. & C. BLACK • LONDON MCMVII

To

HIS EXCELLENCY

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

EARL GREY, G.C.M.G.

GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF CANADA

THIS BOOK IS BY PERMISSION

DEDICATED

The author has not attempted to give a history of Canada. It is a new country, and not the stage of centuries of human struggle and effort, in the sense that European countries are. Therefore his idea has been to describe the great natural features of the land, in its broader characteristics—its coasts, rivers, mountains, lakes, and prairies, those physical beauties and sublime effects of nature for which the region is specially famous. With this he has attempted to depict the seasons, and the beauty of the Canadian woods.

In addition there is given a brief sketch of the settlement and development of the different communities, with special reference to the great centres of provincial and racial activities, and a reference to the people, its origins, composite ideals, and the leading actors on its historical stage of progress and accomplishment.

Ottawa, Canada.

December 1906.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Maritime Provinces and the Early Discoverers | 13 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Maritime Provinces—Later History and Characteristics | 29 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Quebec and the Lower St Lawrence Valley | 49 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Montreal and the Upper St Lawrence | 72 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Ottawa, the Capital of the Dominion | 94 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Canadian Seasons and Woods | 119 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Toronto and Western Ontario | 143 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Canadian Lake Region | 177 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Old North-West and Manitoba | 206 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Two New Prairie Provinces | 224 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| British Columbia and the Rocky Mountains | 237 |

| INDEX | 263 |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

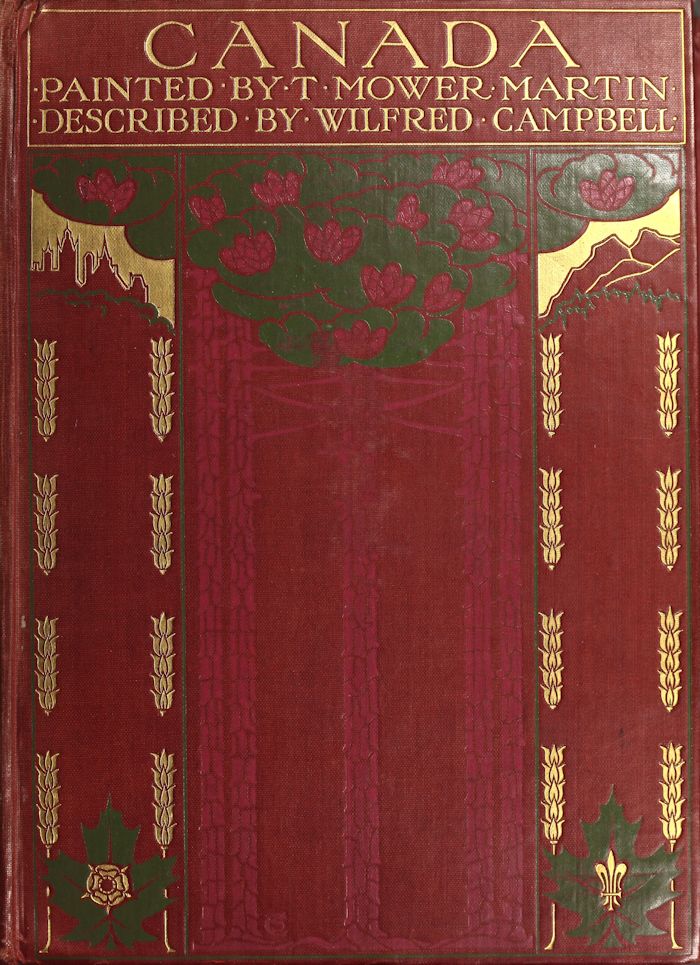

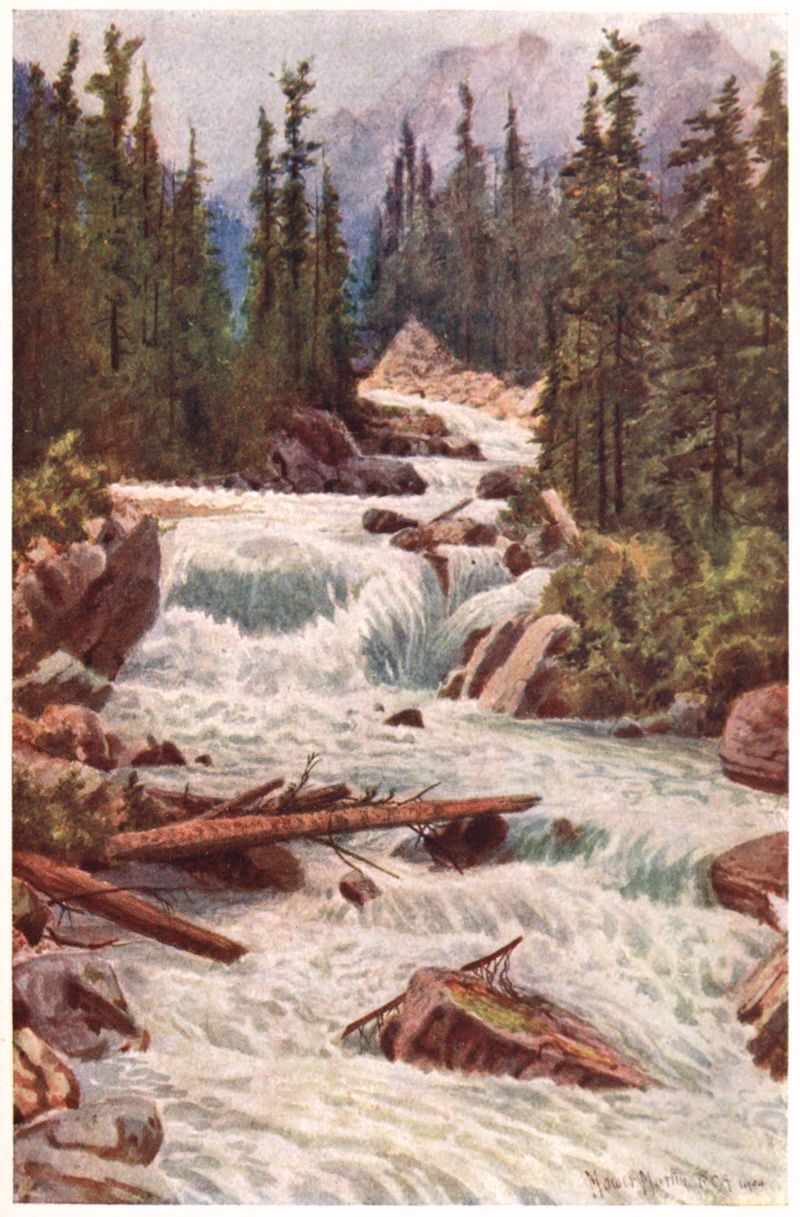

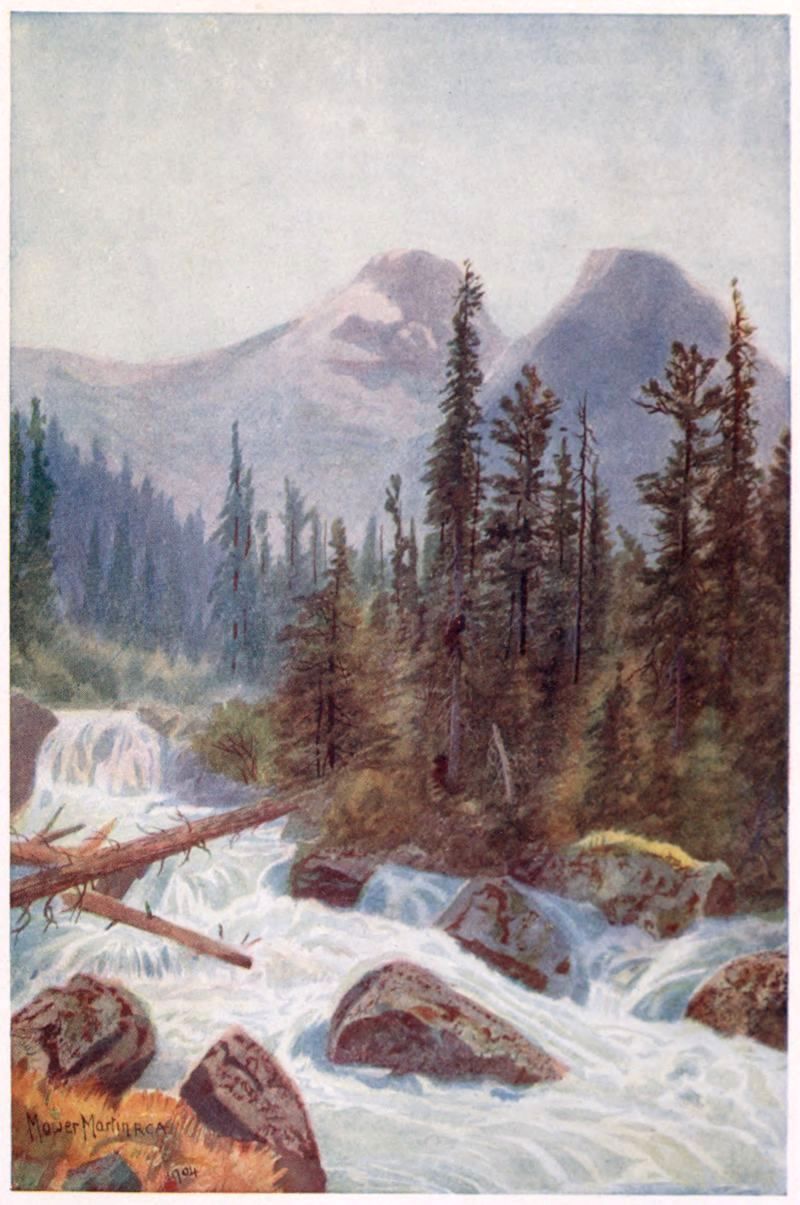

| 1. | Illecillewaet below Sir Donald | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | ||

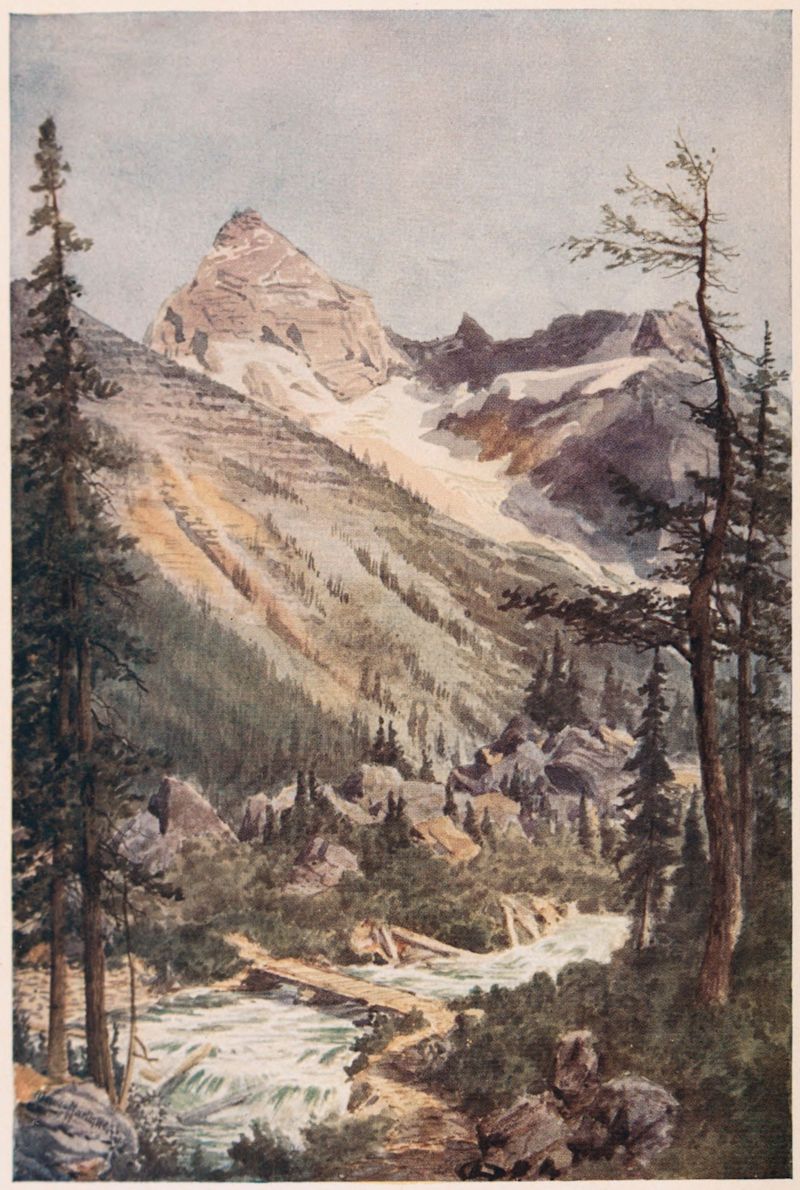

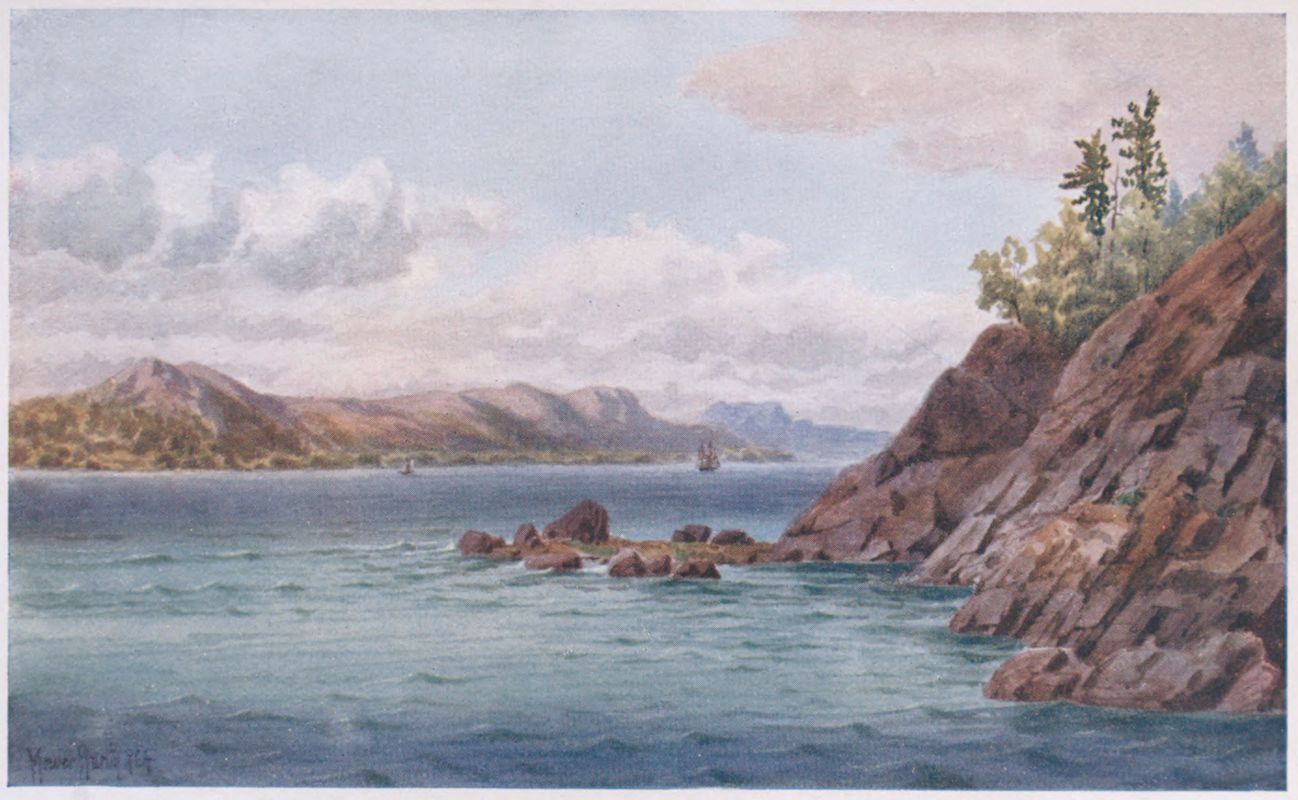

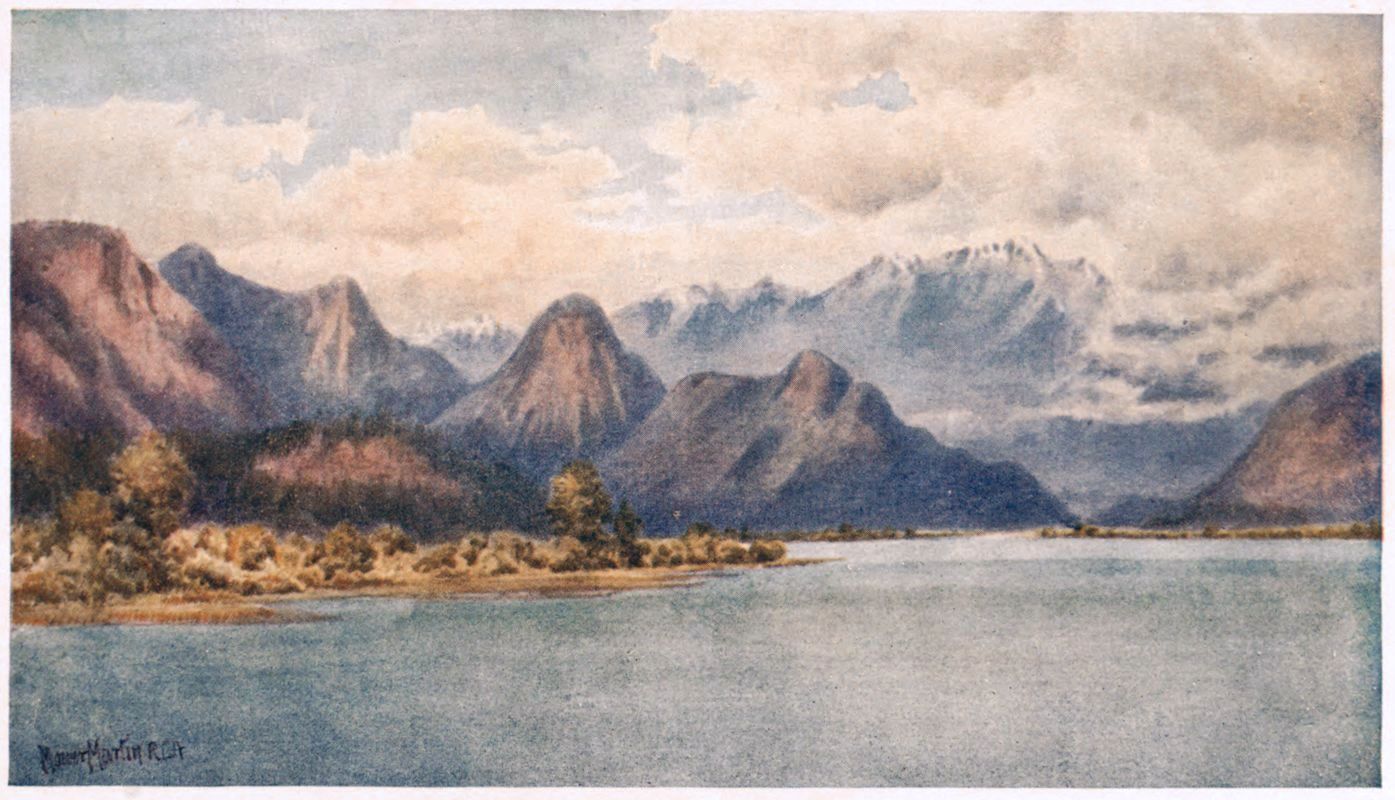

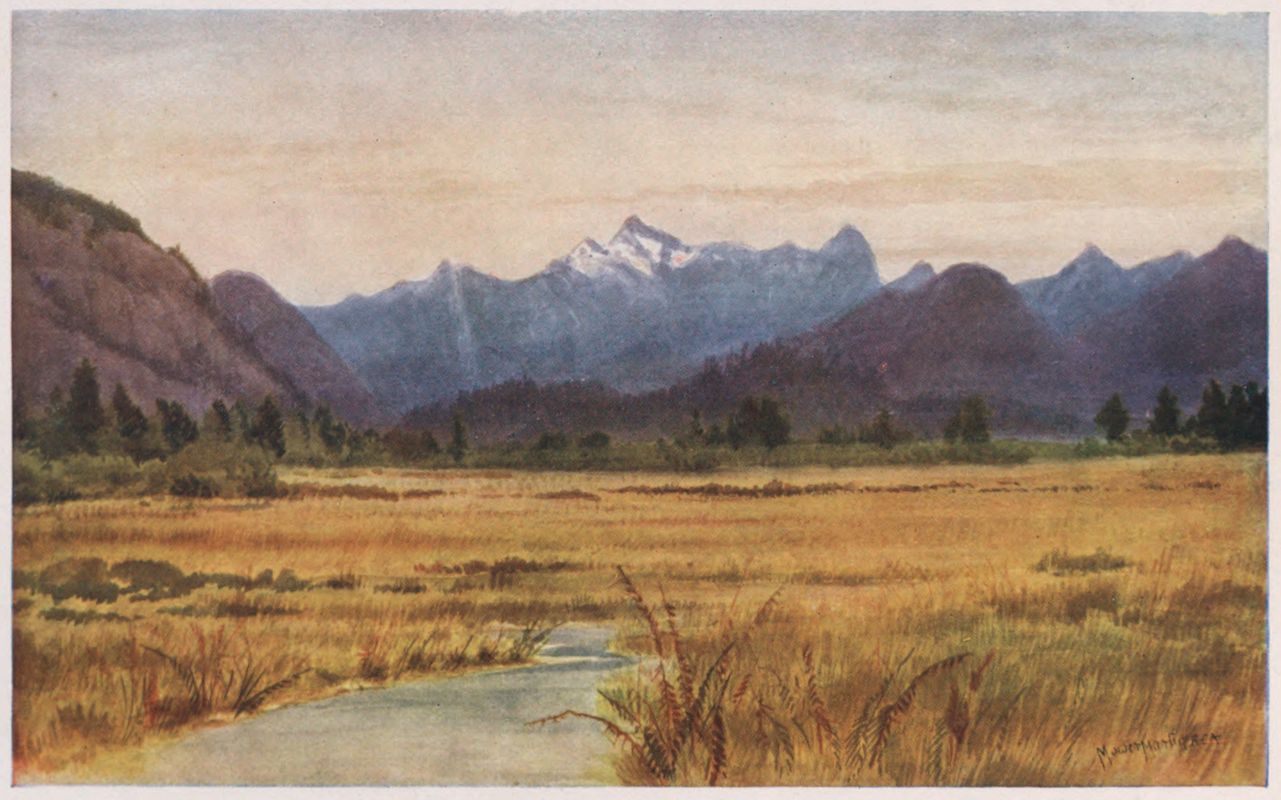

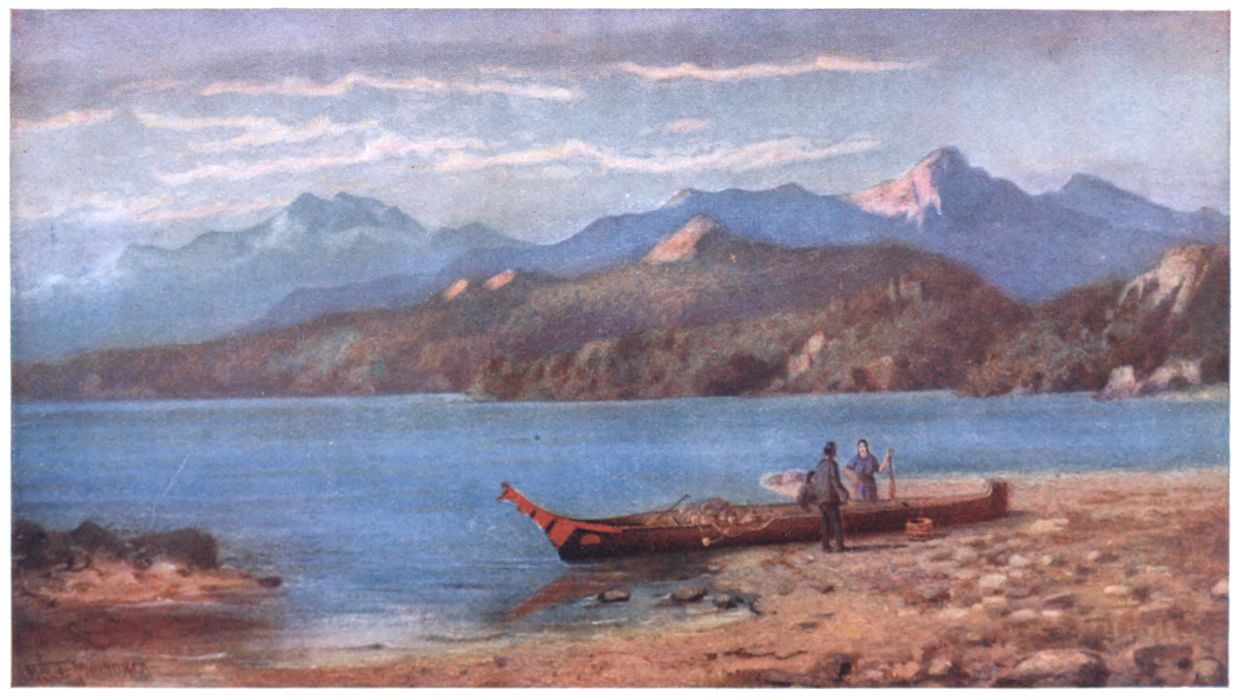

| 2. | North of Howe Sound, Pacific Coast, British Columbia | 2 |

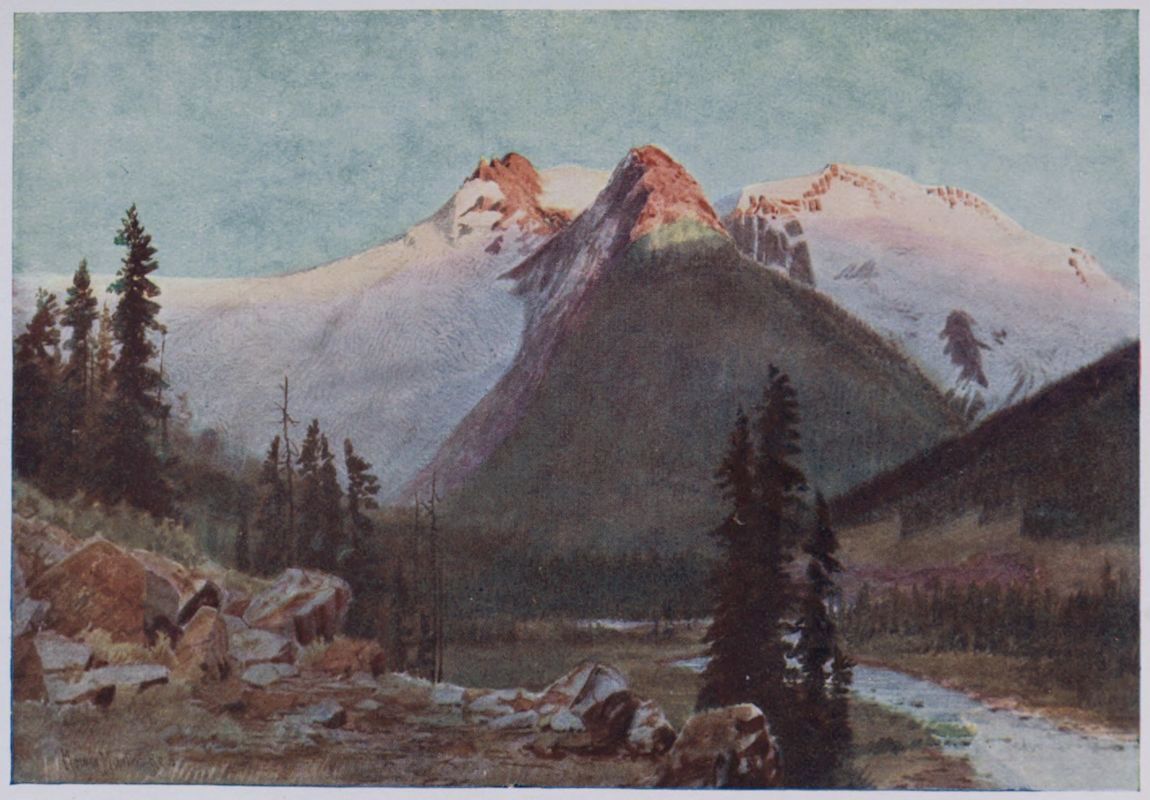

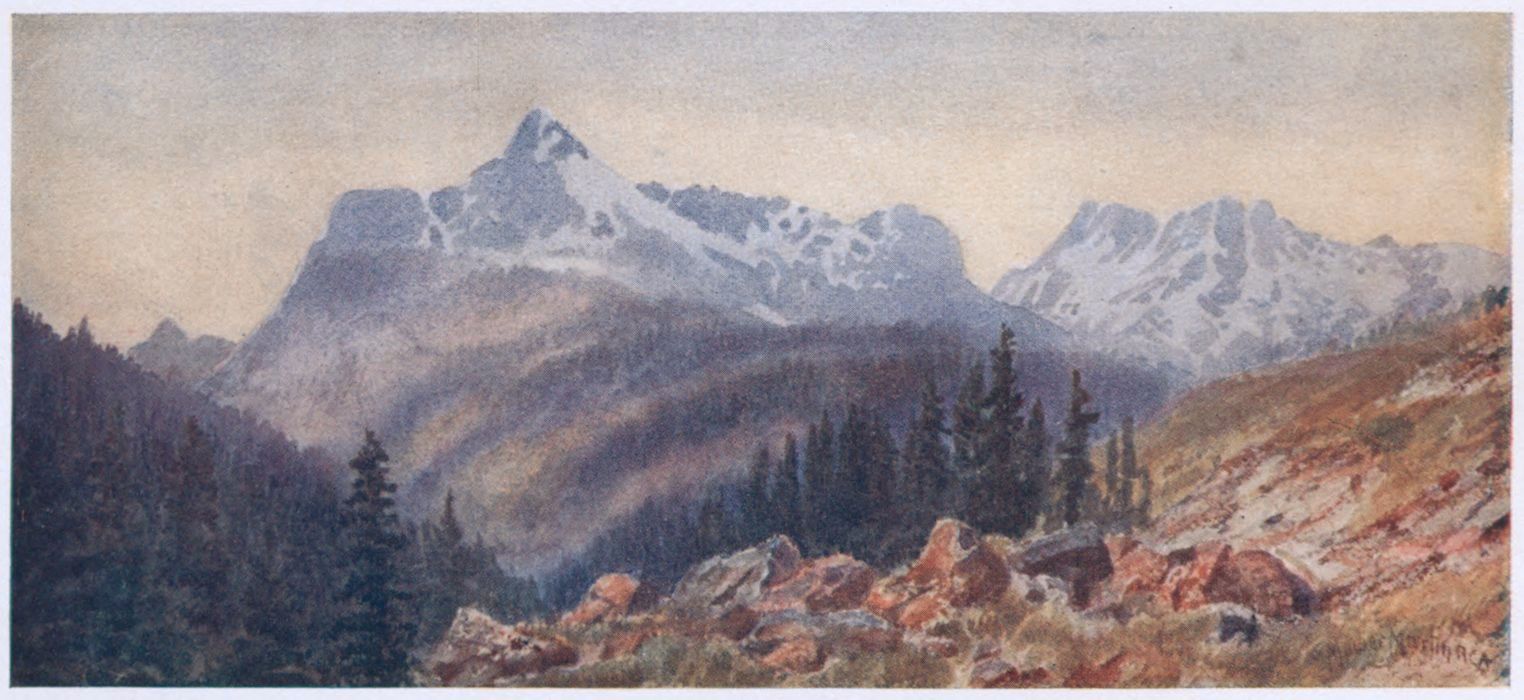

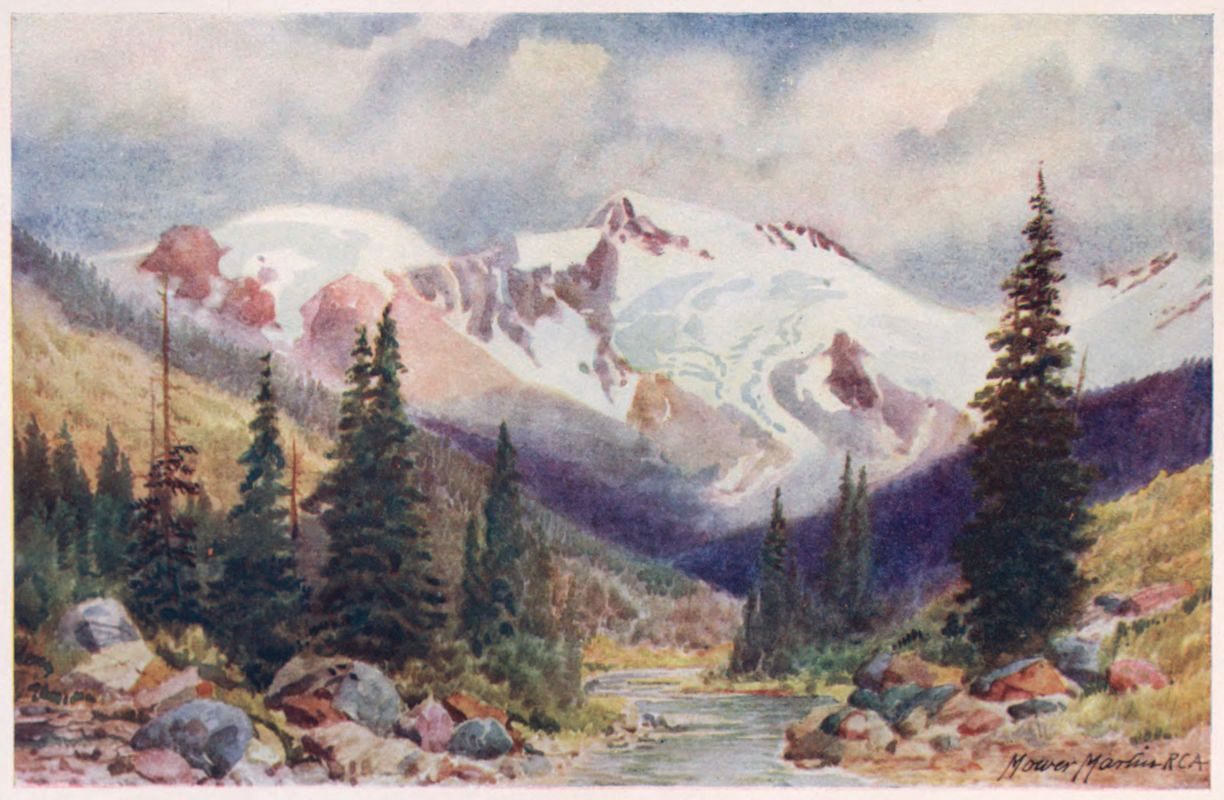

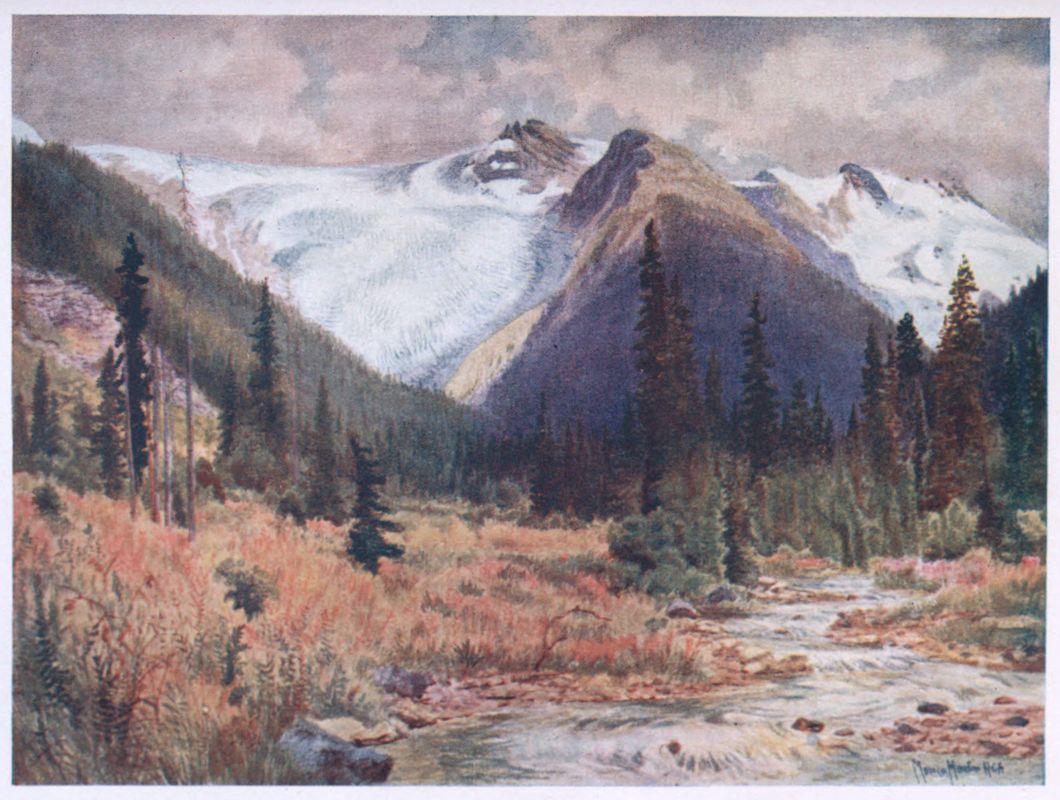

| 3. | Mount Cheops and the Hermit Range | 4 |

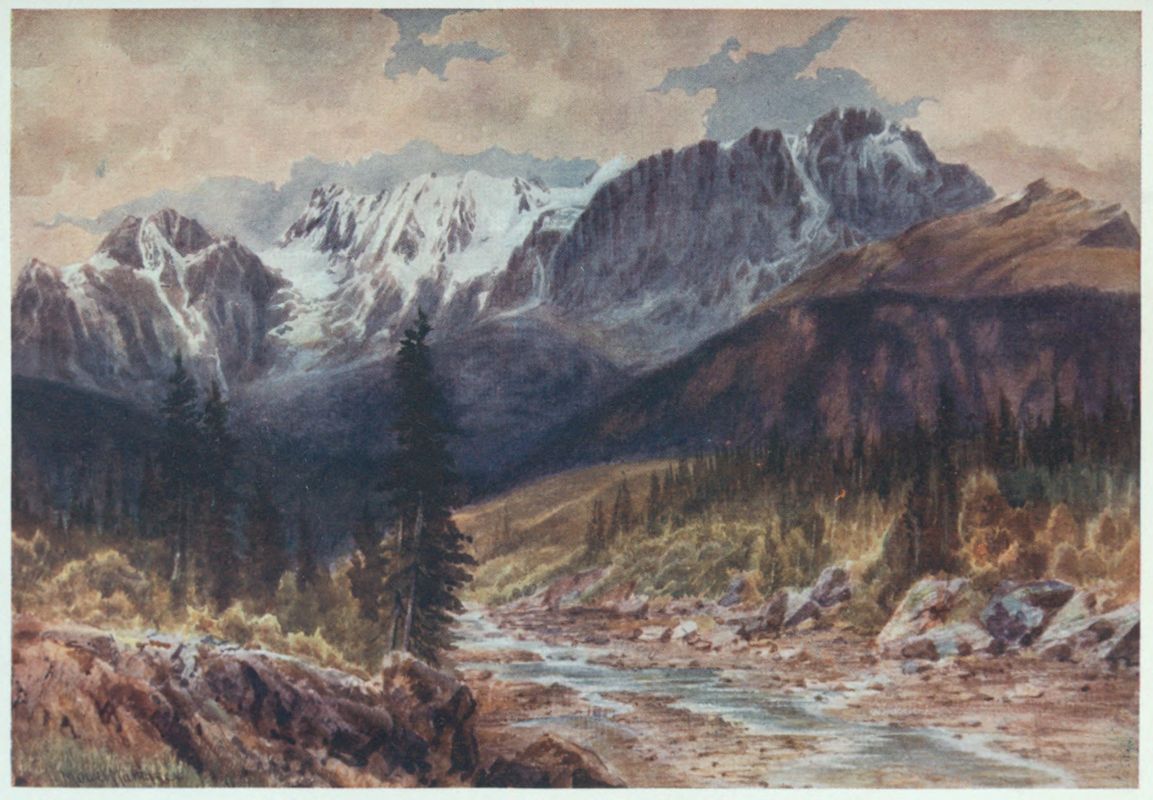

| 4. | Sunset on the Great Selkirk Glaciers | 6 |

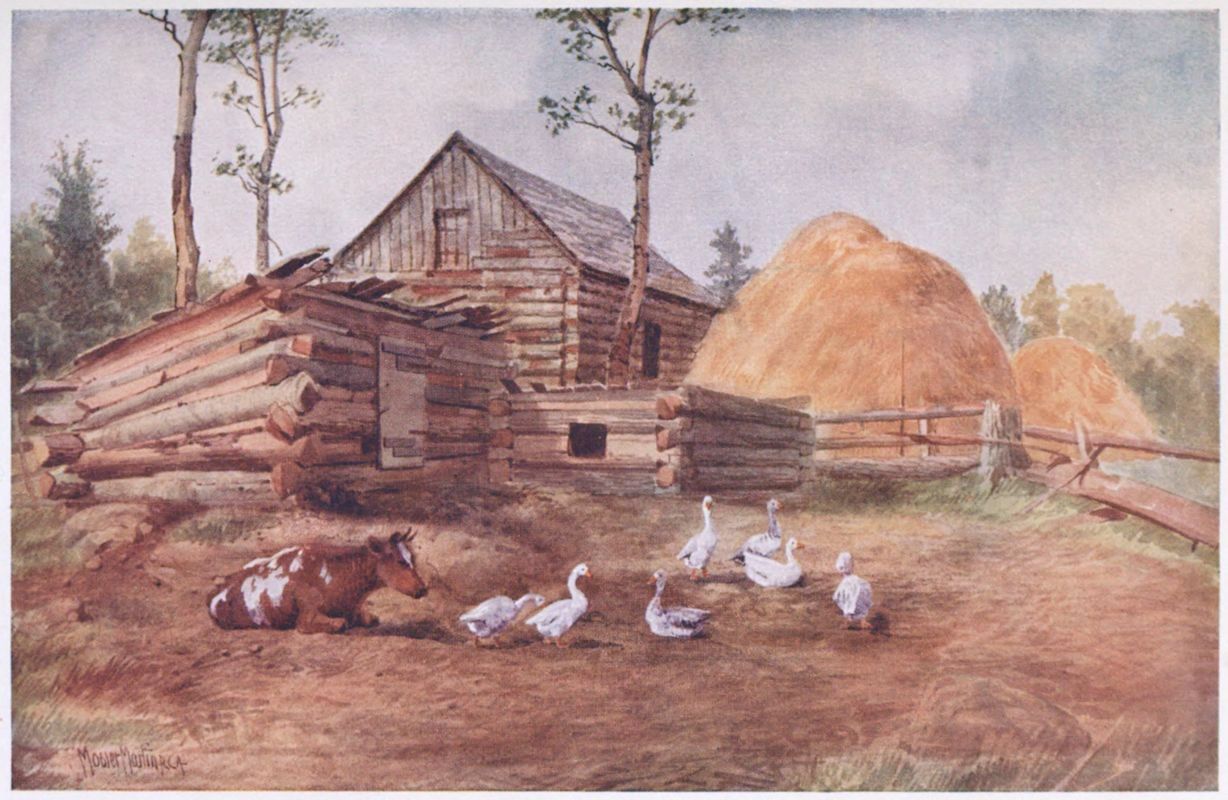

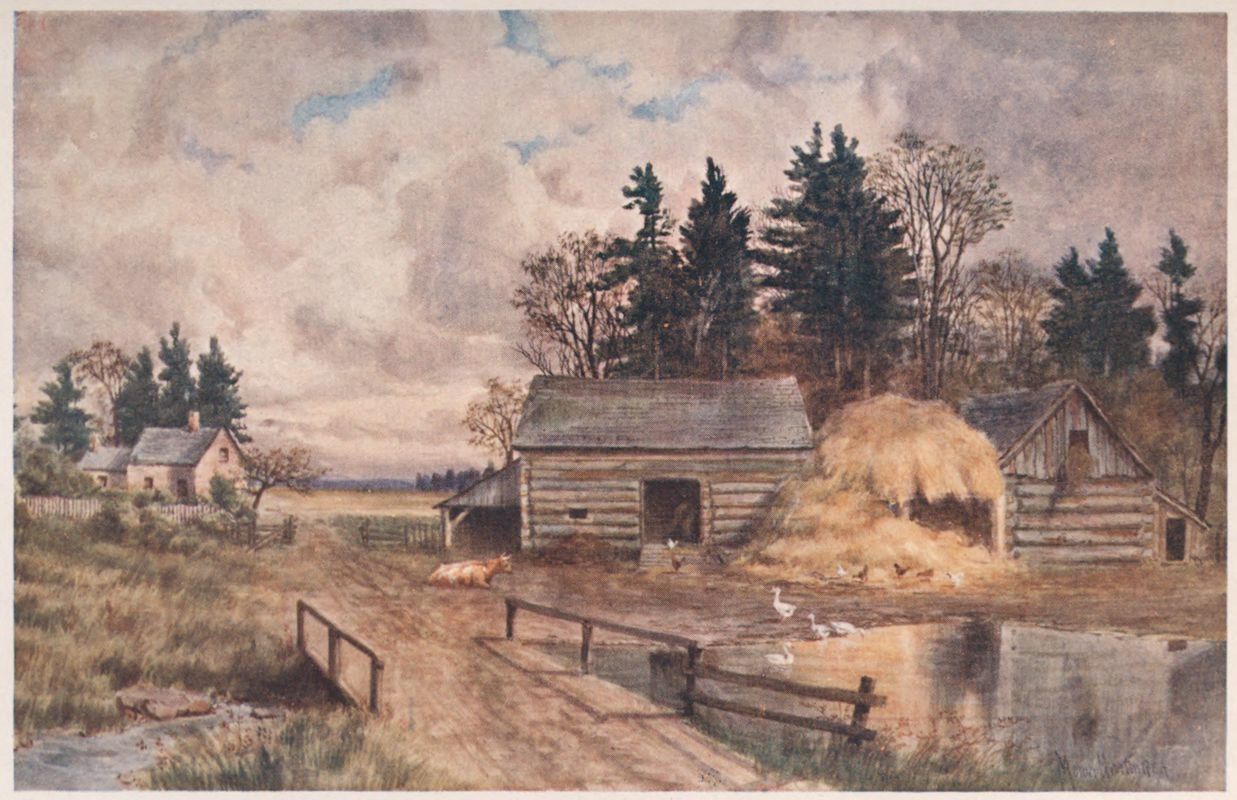

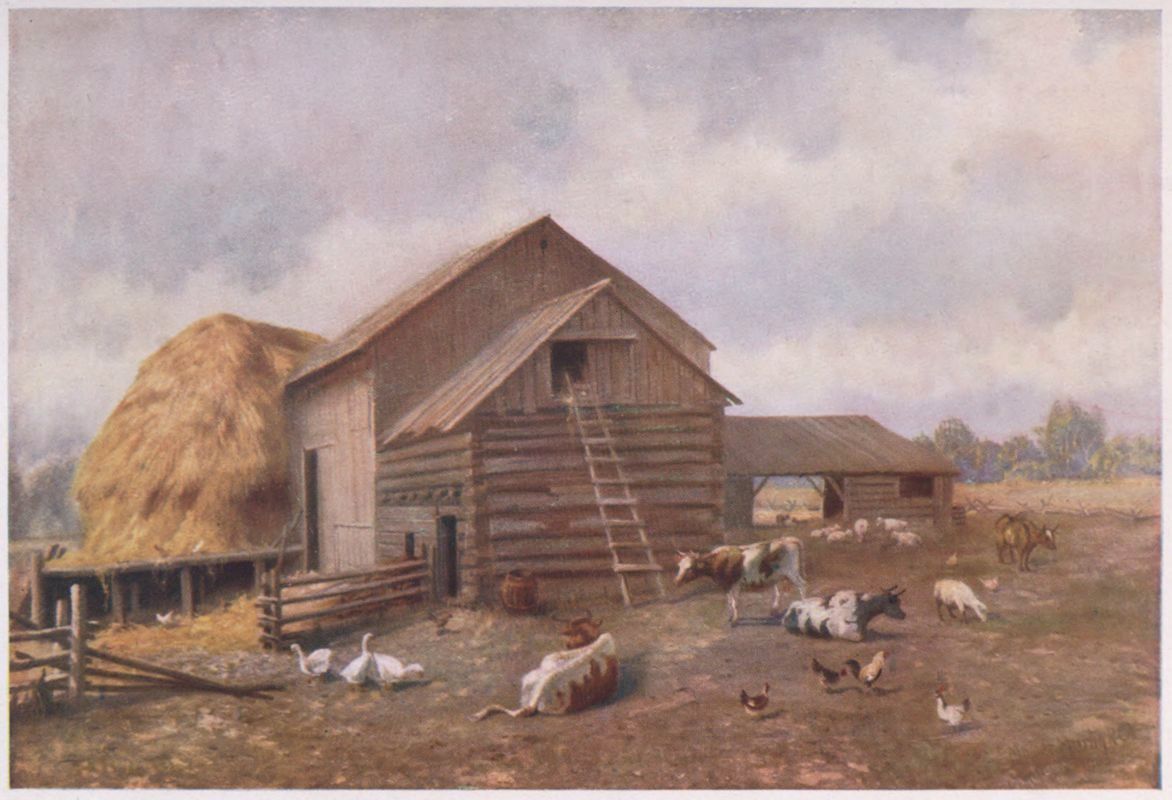

| 5. | Settler’s Farmyard, Muskoka | 8 |

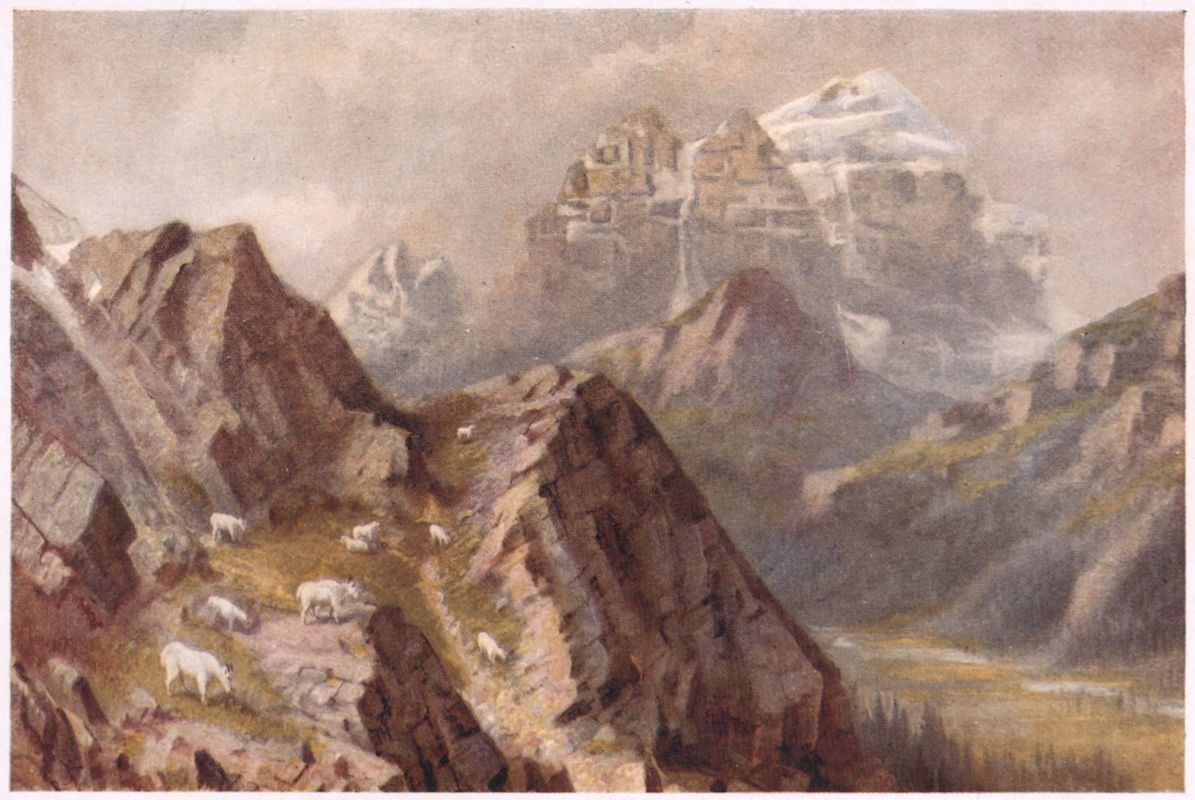

| 6. | Mountain Goats Feeding | 10 |

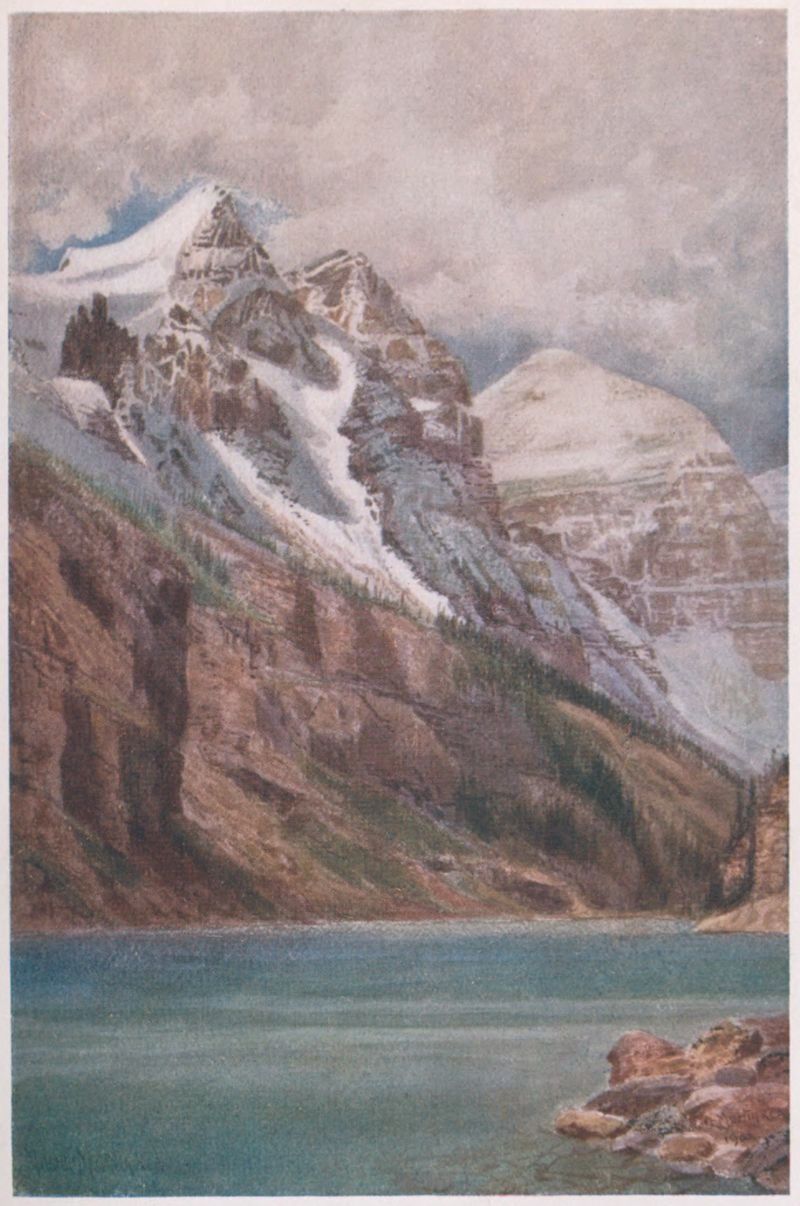

| 7. | End of Lake Louise, and Mount Aberdeen | 12 |

| 8. | Road near the Bay of Fundy, Autumn | 16 |

| 9. | Fall of the Year, Nova Scotia | 20 |

| 10. | Port Hawkesbury, on the Strait of Canso, Cape Breton | 24 |

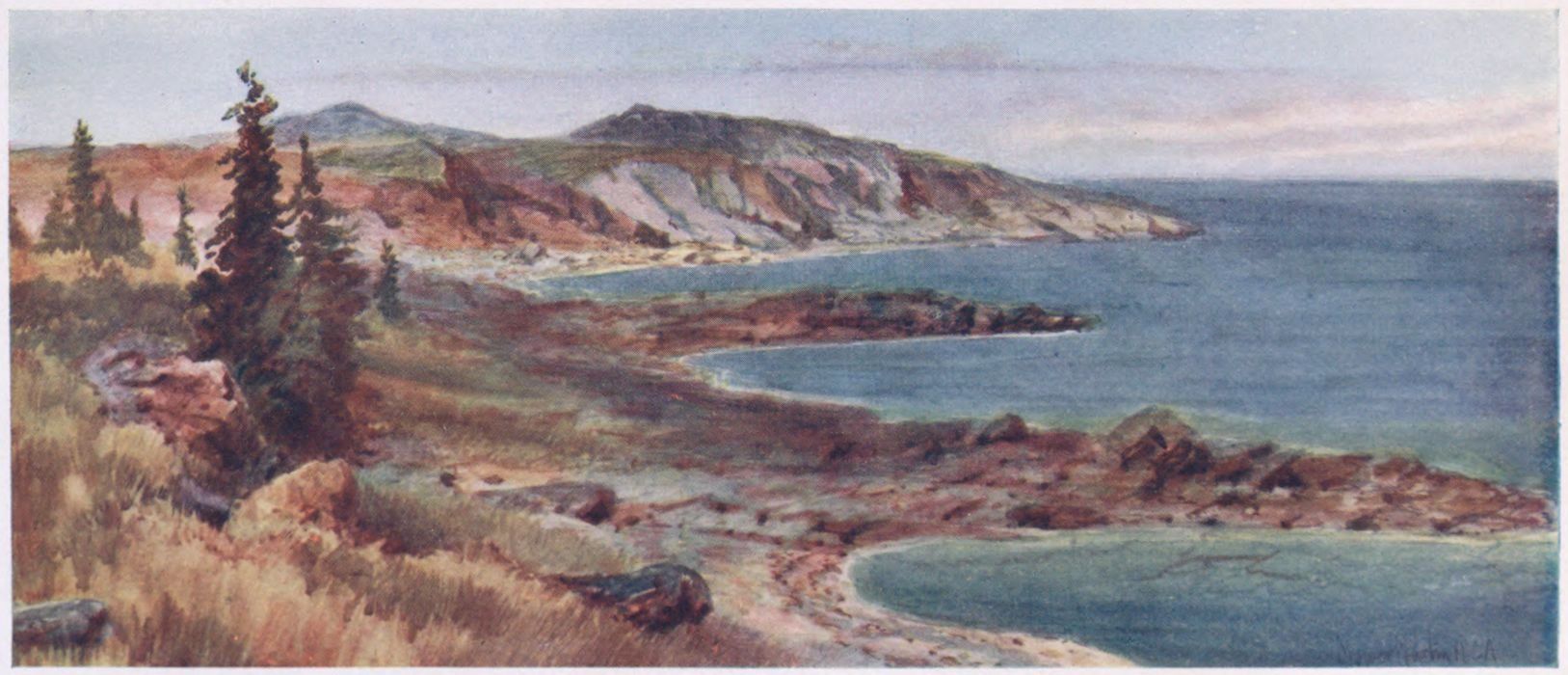

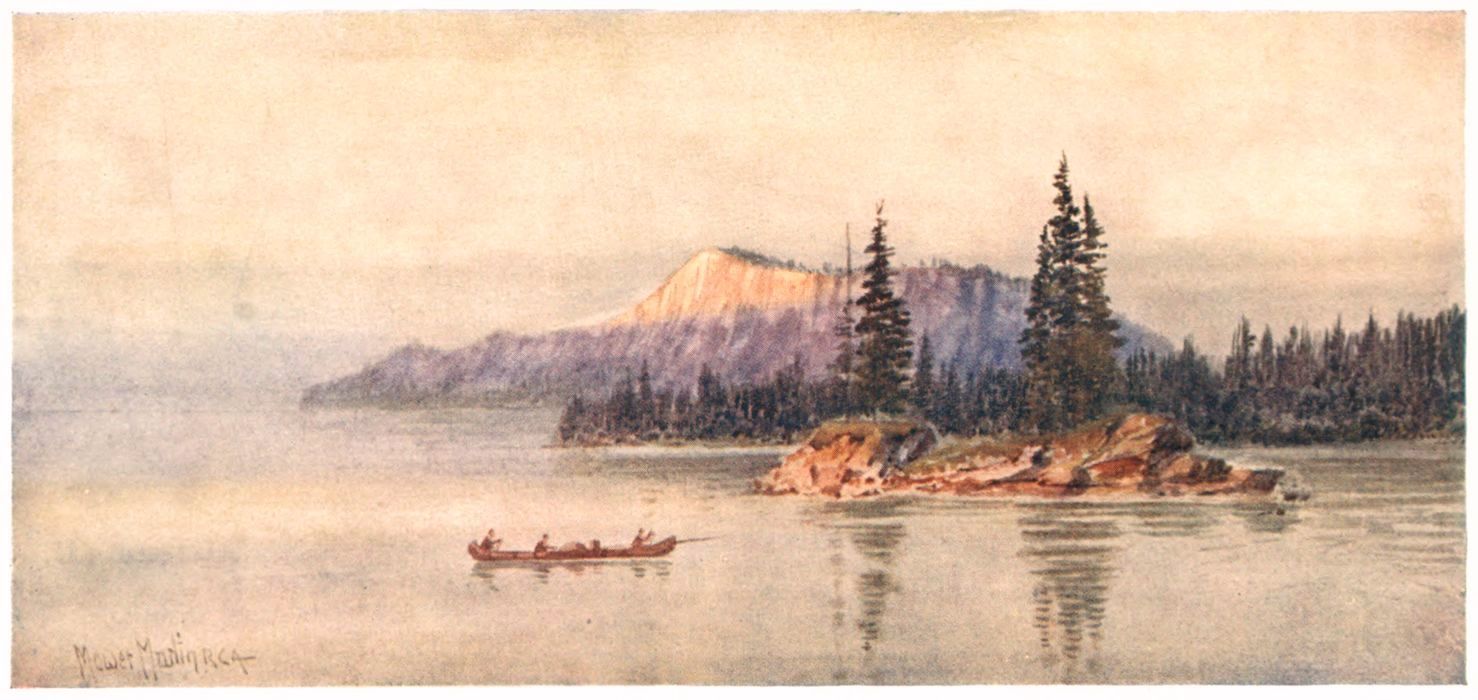

| 11. | Cape Porcupine, Gut of Canso, Cape Breton | 28 |

| 12. | Old-fashioned Farm, New Brunswick | 32 |

| 13. | Basin of Minas, Nova Scotia | 36 |

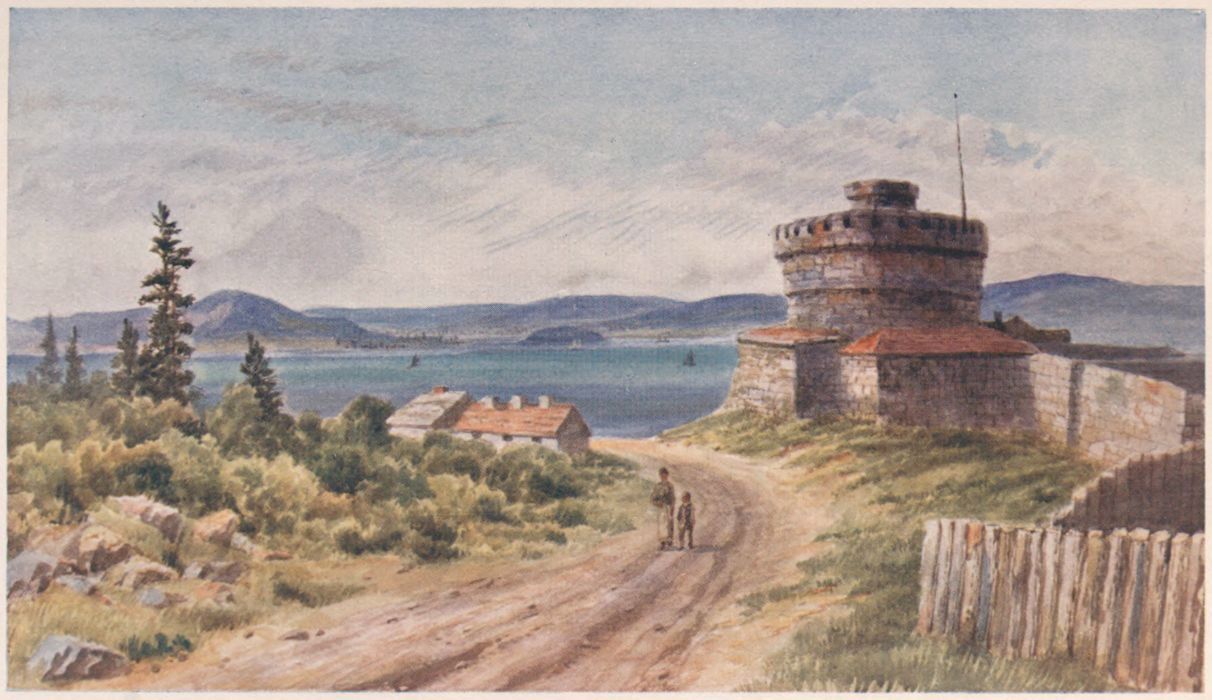

| 14. | York Redoubt, and Halifax Harbour | 40 |

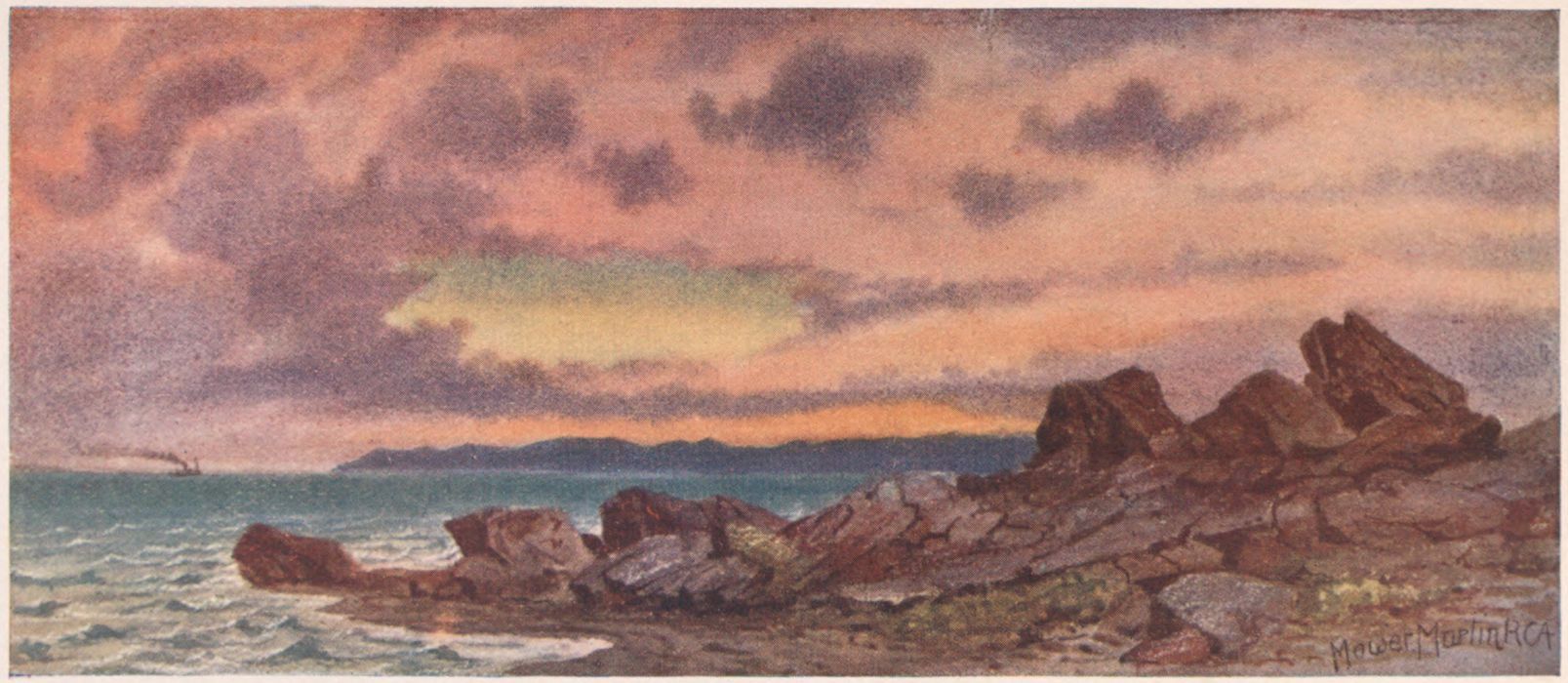

| 15. | Stormy Sunset, Coast near St John, New Brunswick | 44 |

| 16. | St Lawrence, near Sillery Cove | 54 |

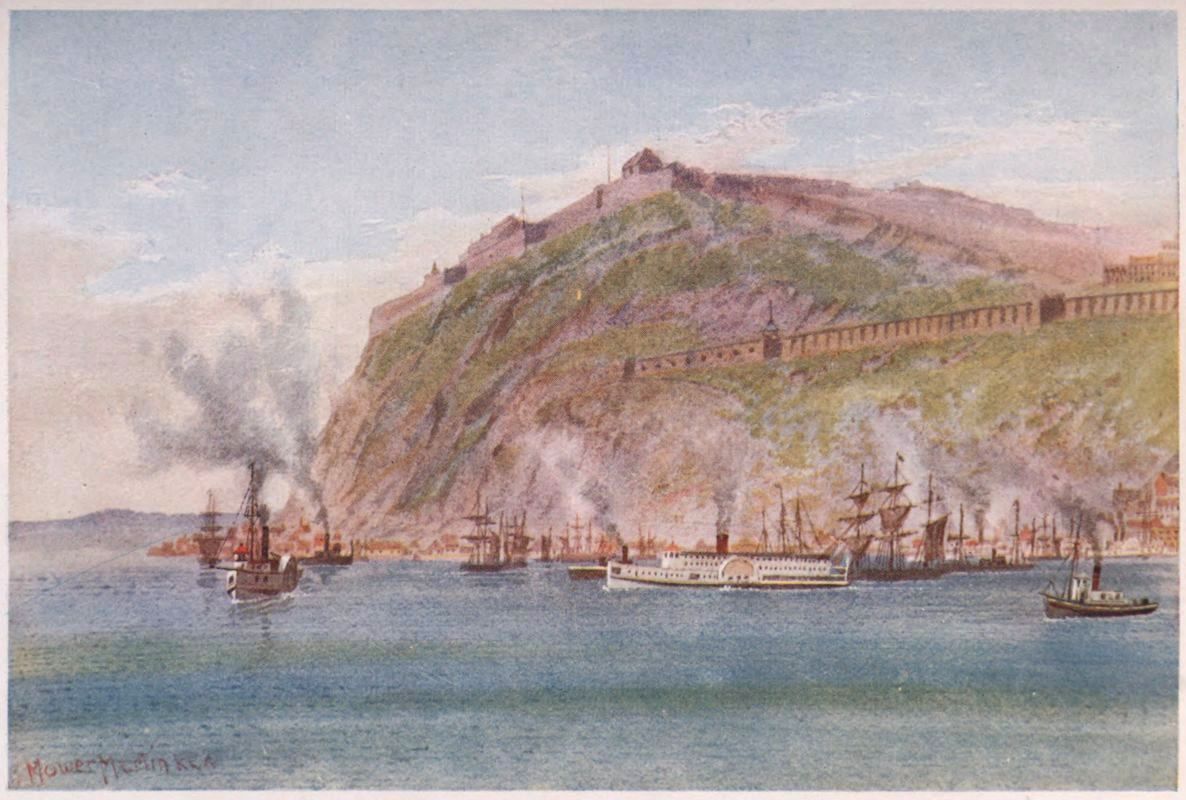

| 17. | The Citadel, Quebec | 62 |

| 18. | Quebec, from Point Levis | 64 |

| 19. | Martello Tower, Plains of Abraham | 70 |

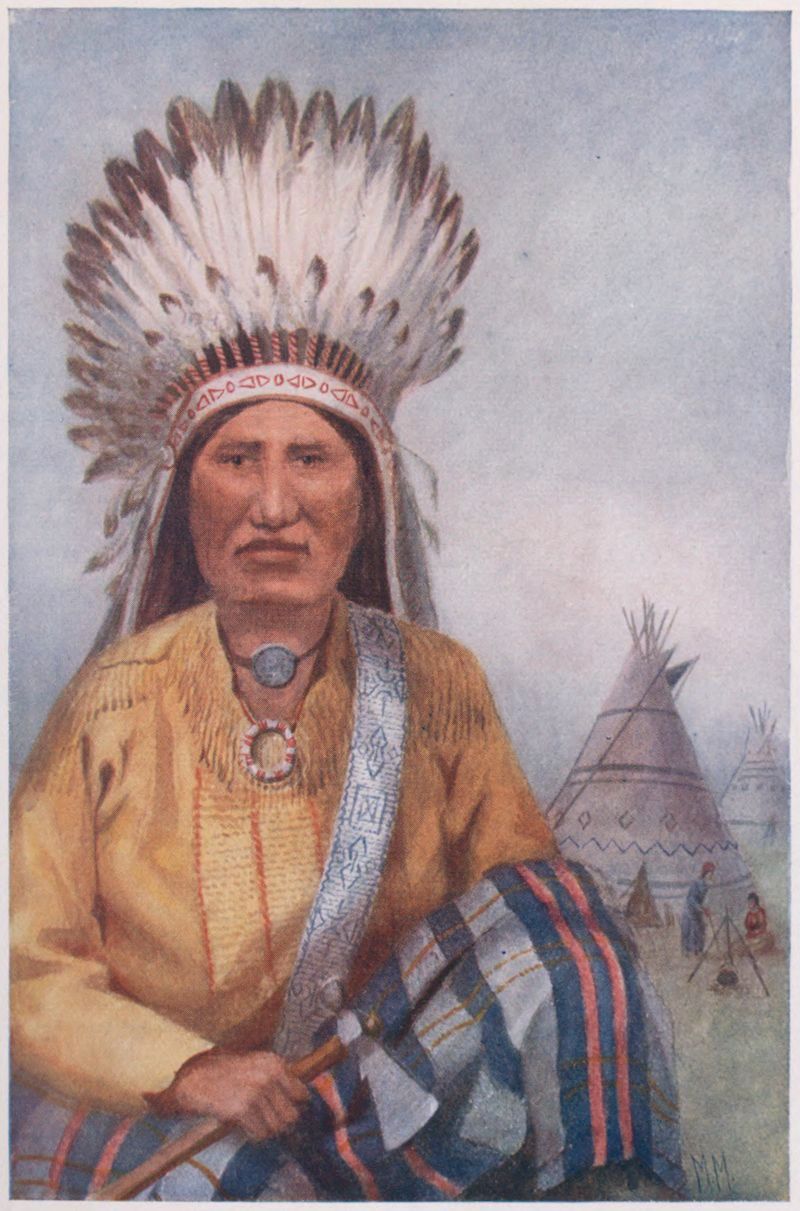

| 20. | An Indian Chief | 74 |

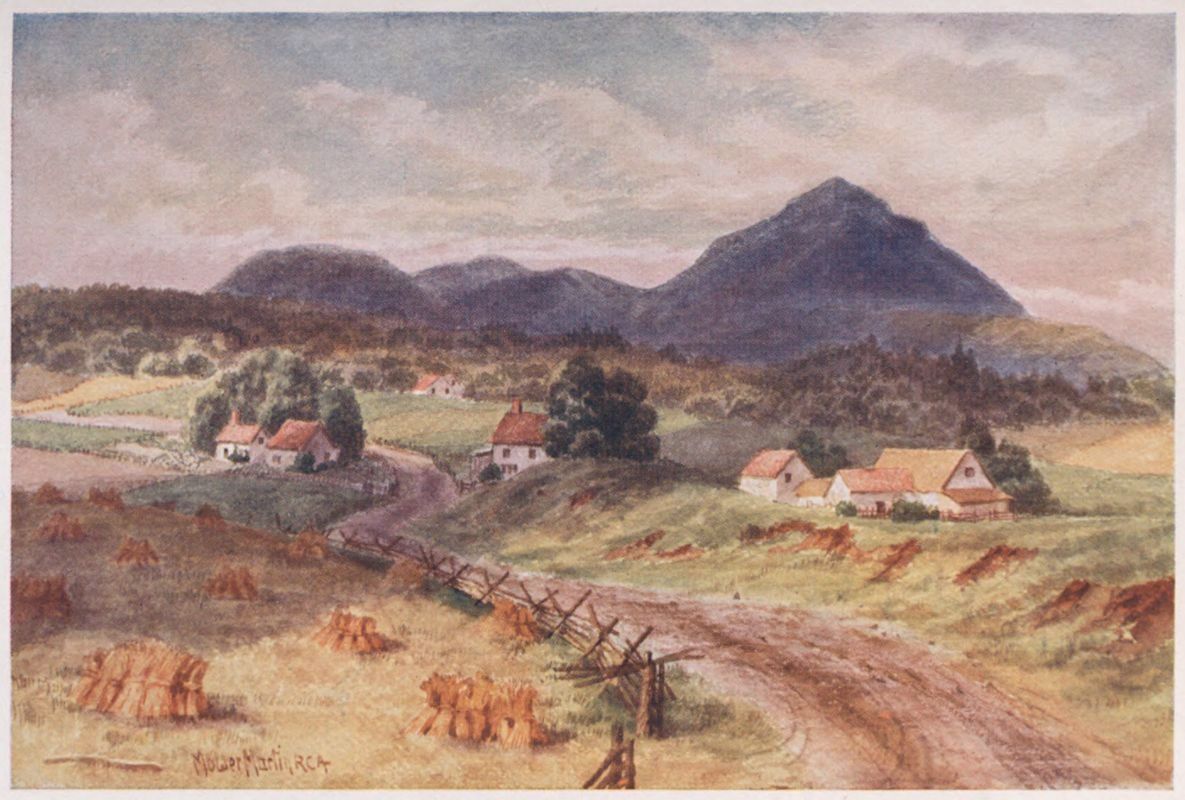

| 21. | Owl’s Head Mountain, near Montreal | 76 |

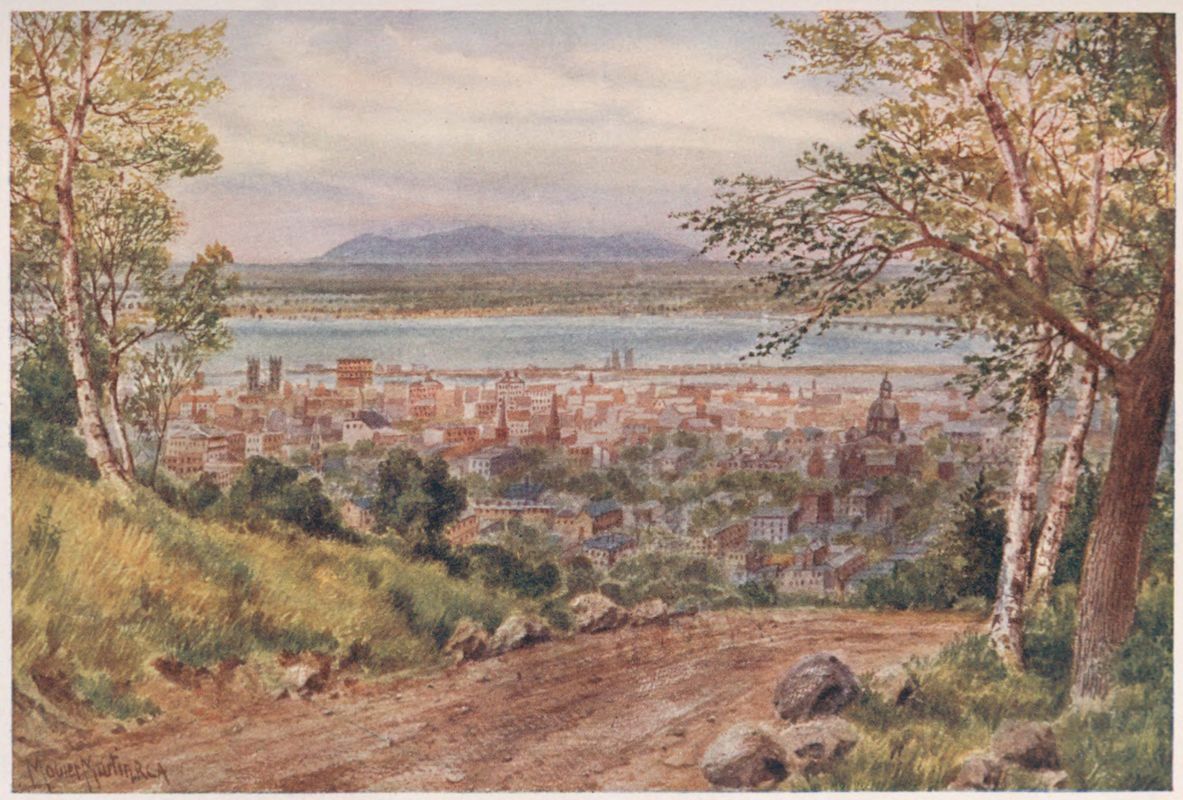

| 22. | Montreal: the River St Lawrence from the Mountain | 80 |

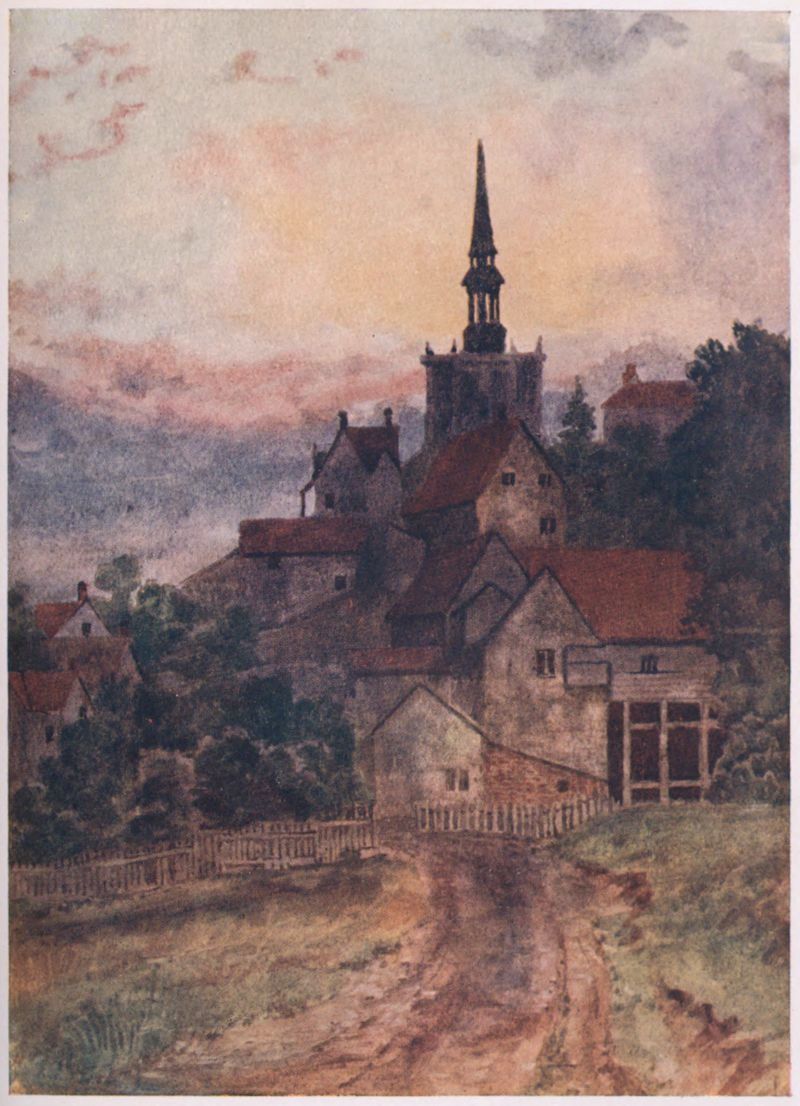

| 23. | In Sherbrooke, Eastern Townships, Quebec | 86 |

| 24. | A Farmyard in Ontario | 94 |

| 25. | Ottawa, from near the Experimental Farm | 102 |

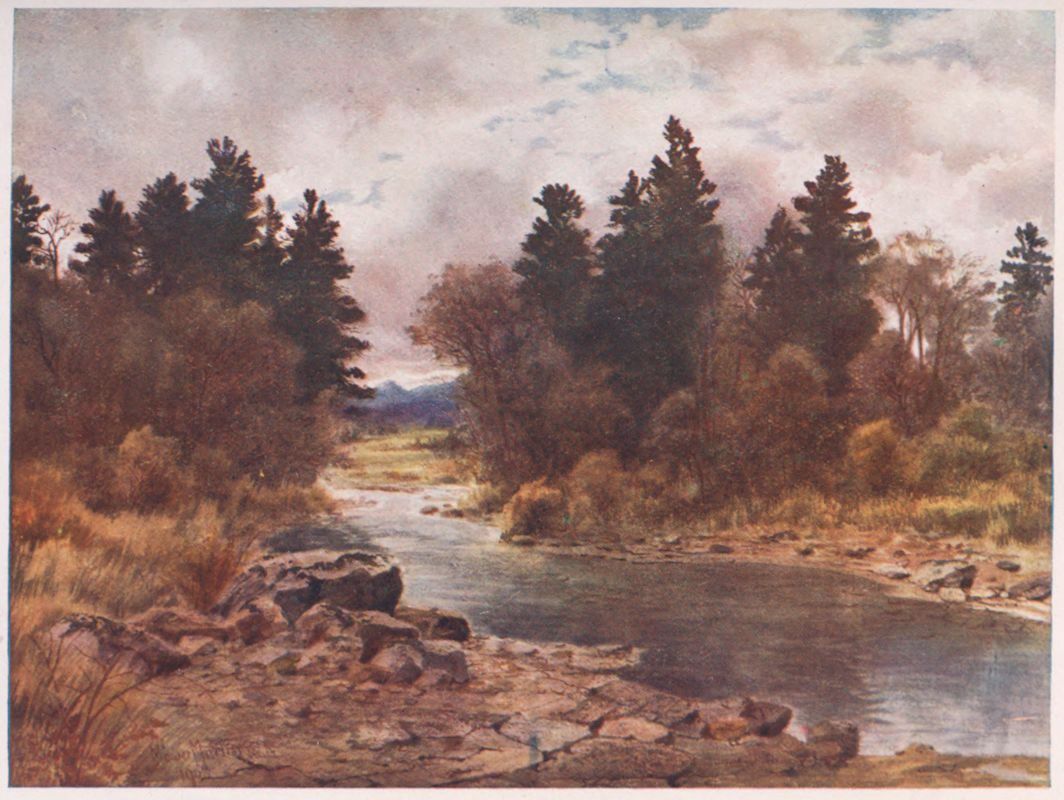

| 26. | The Ottawa at Vaudreuil | 108 |

| 27. | Early Spring, near Victoria, British Columbia | 120 |

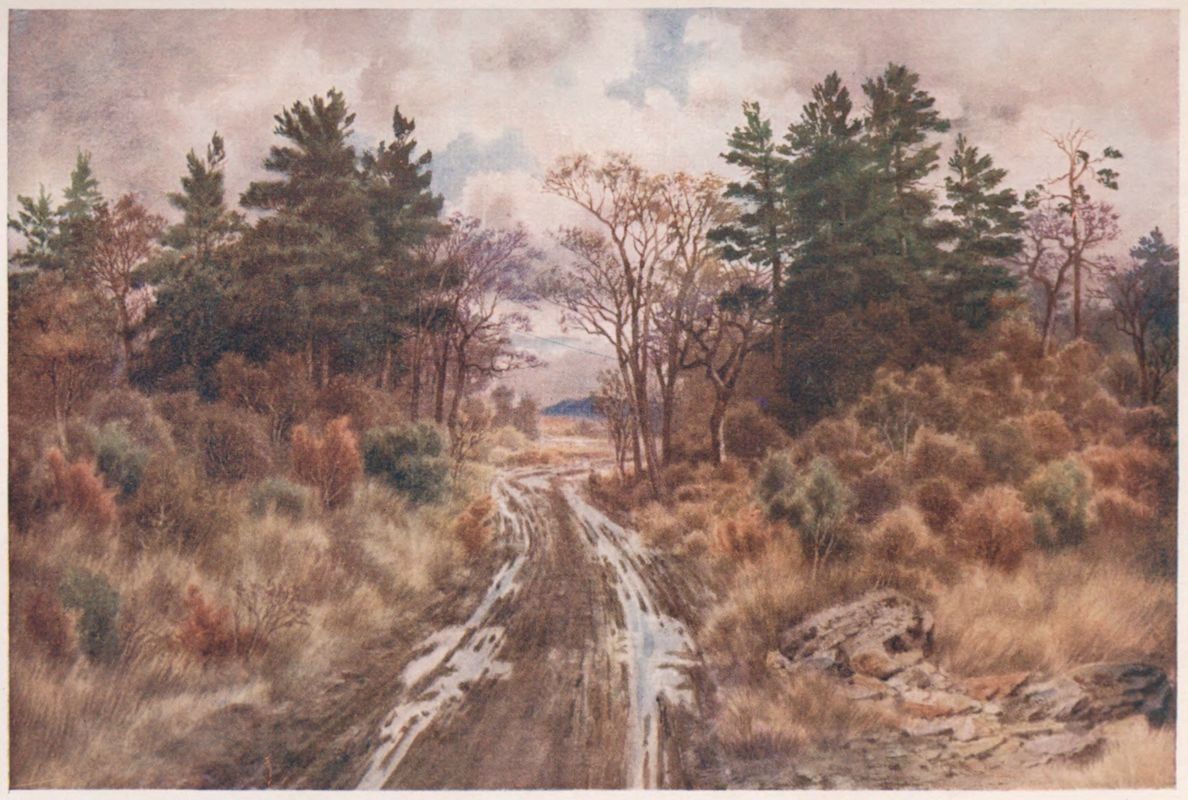

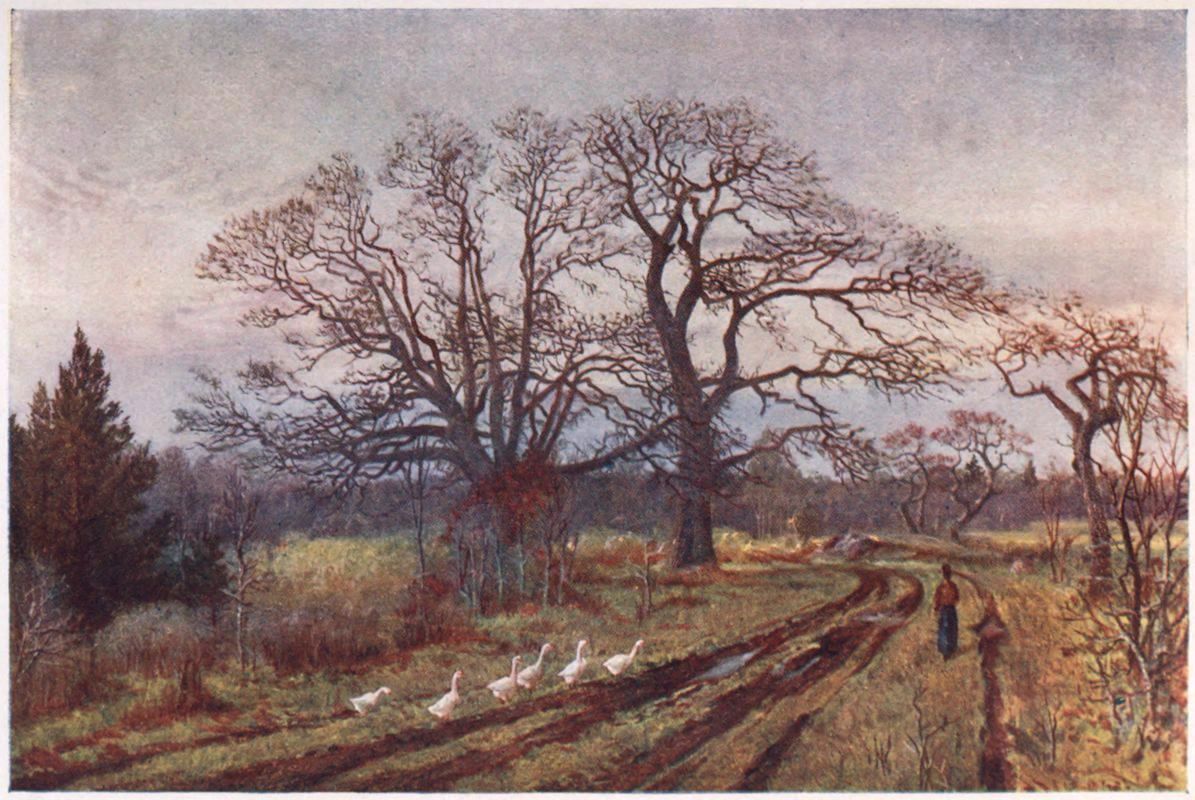

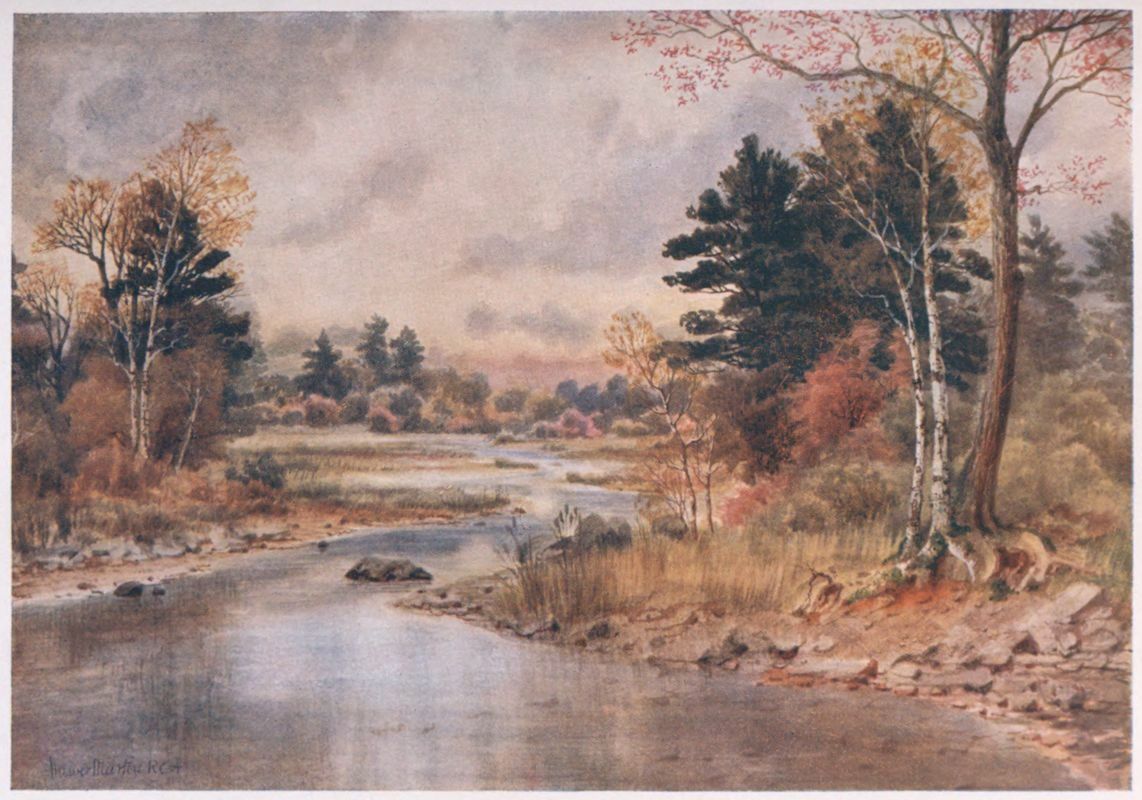

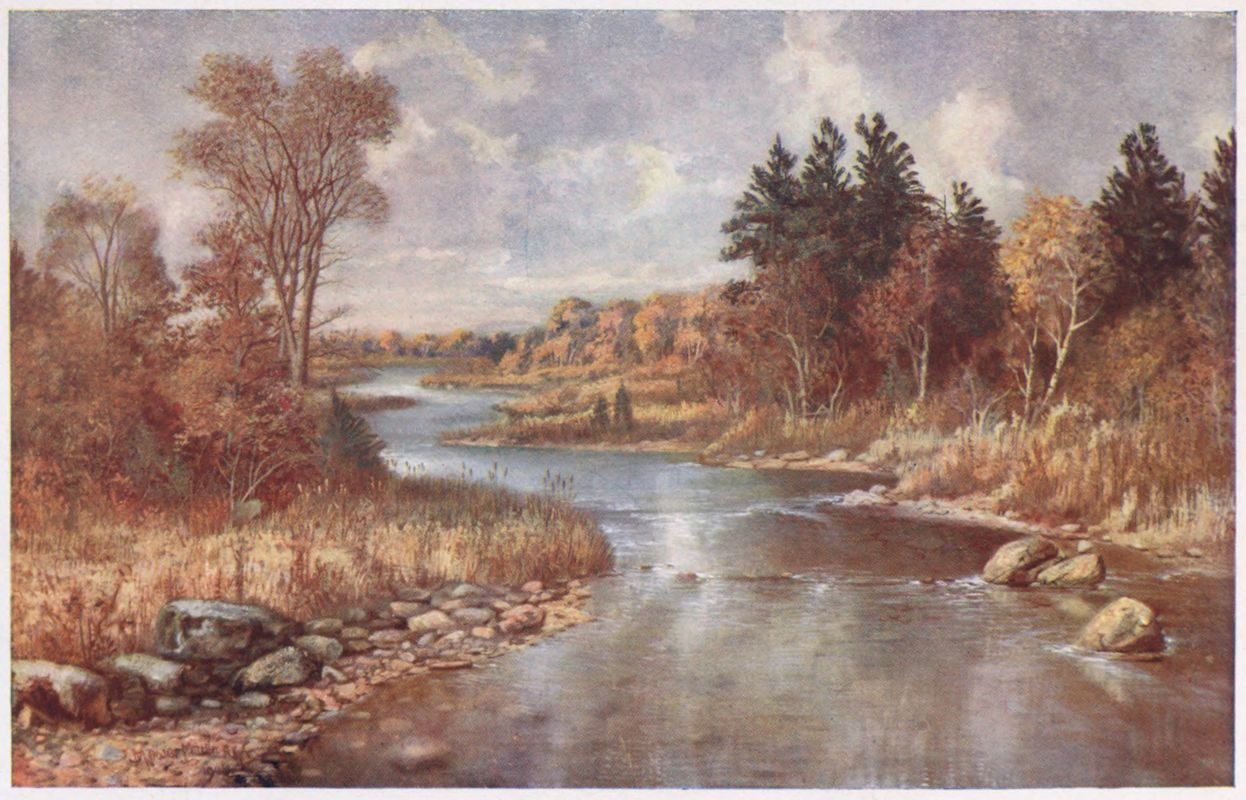

| 28. | Autumn in New Brunswick | 124 |

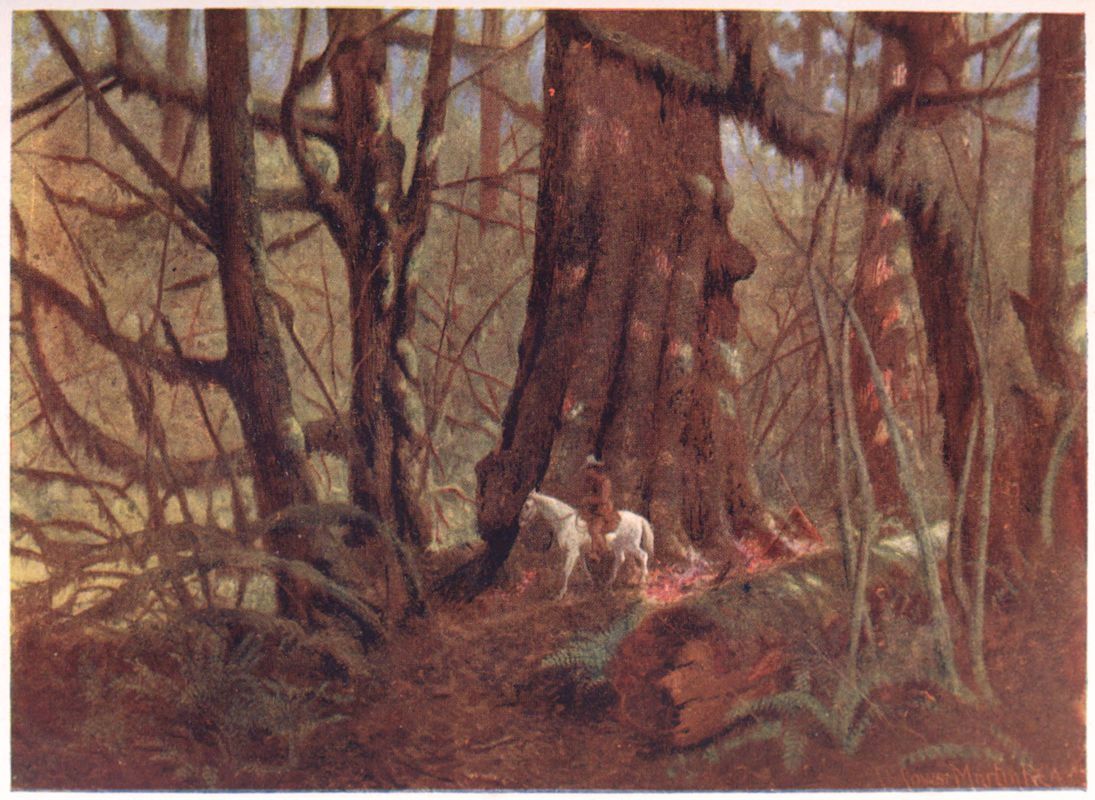

| 29. | Big Spruce in Stanley Park | 128 |

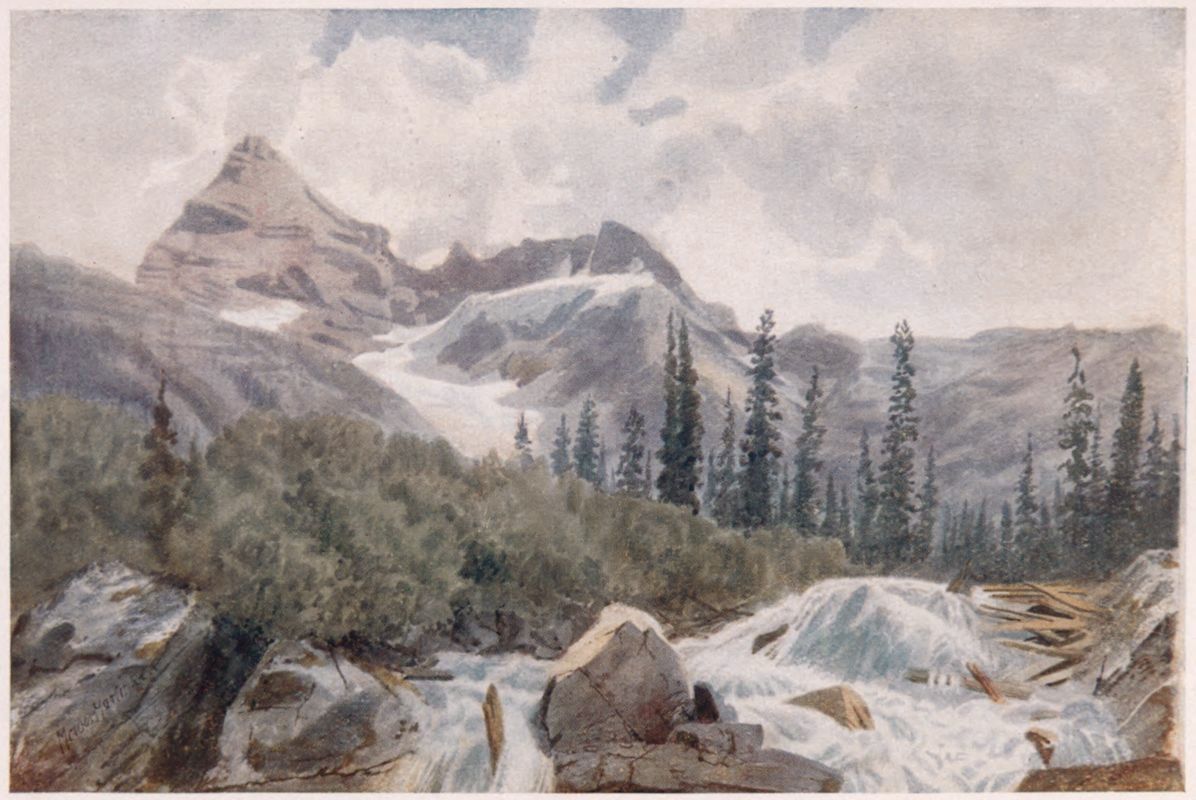

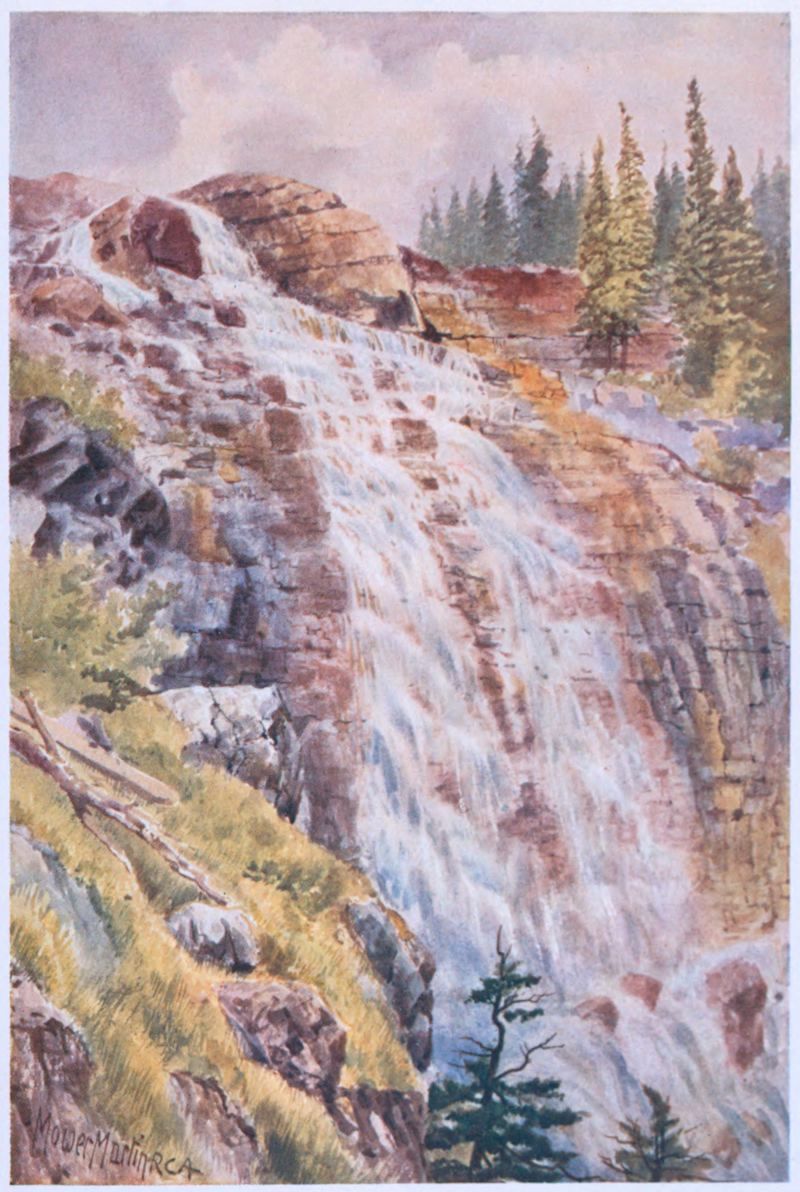

| 30. | Falls on the Illecillewaet River, Selkirk Mountains, British Columbia | 130 |

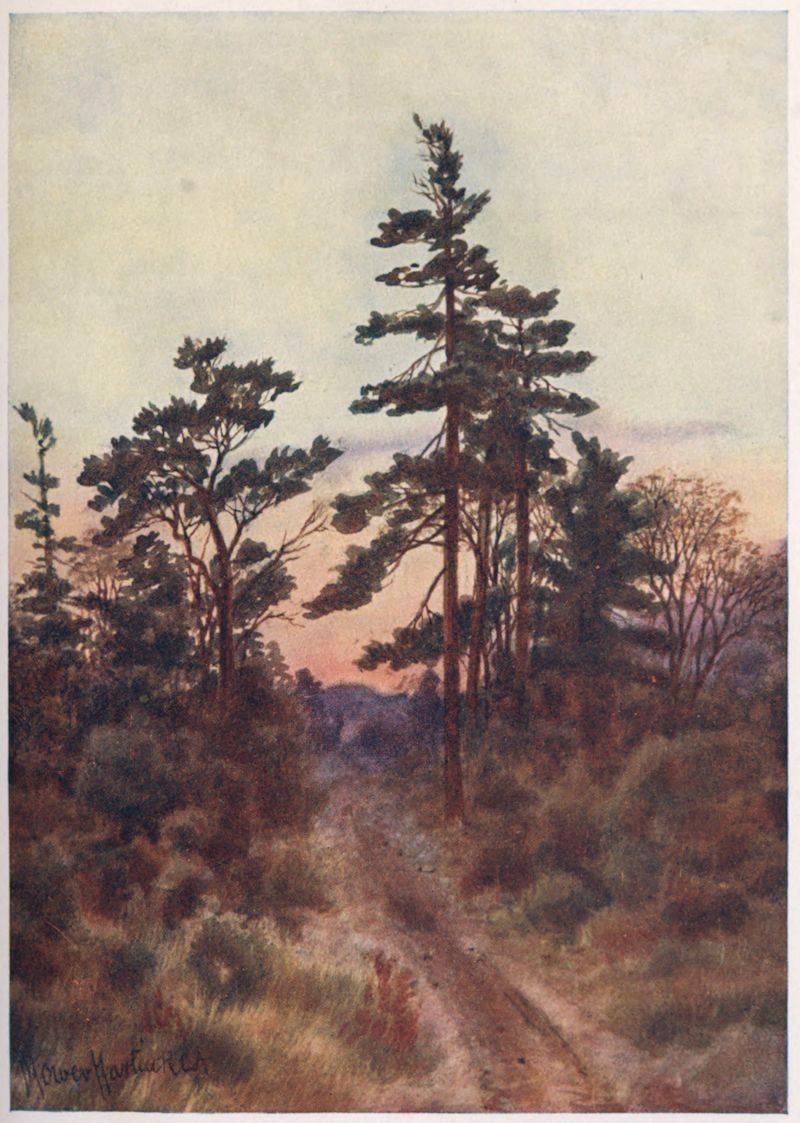

| 31. | Road near Victoria (Evening) | 132 |

| 32. | Winter-time in Vancouver Island, British Columbia | 136 |

| 33. | Ross Peak, Selkirk Mountains, British Columbia | 140 |

| 34. | Toronto, from the Island | 150 |

| 35. | Toboganning at Rosedale, Toronto | 158 |

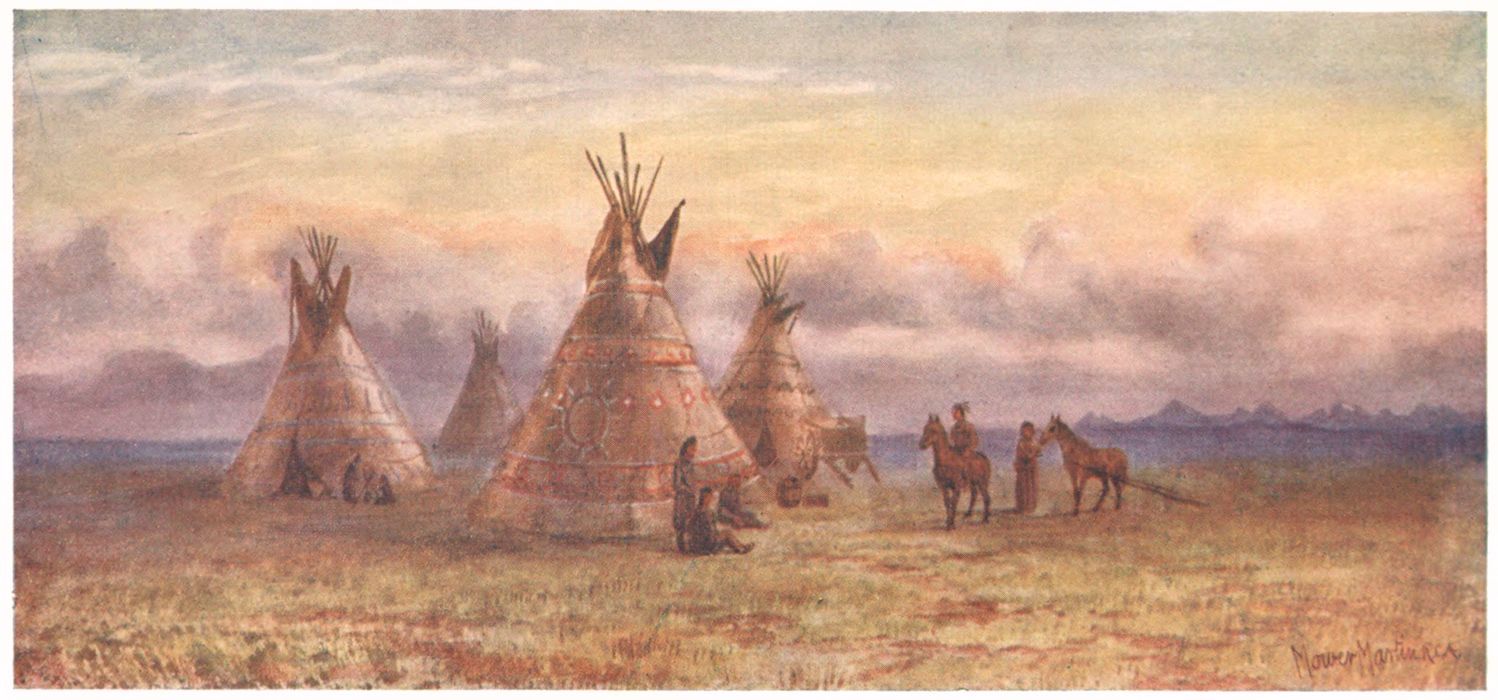

| 36. | Indians in the Olden Time | 164 |

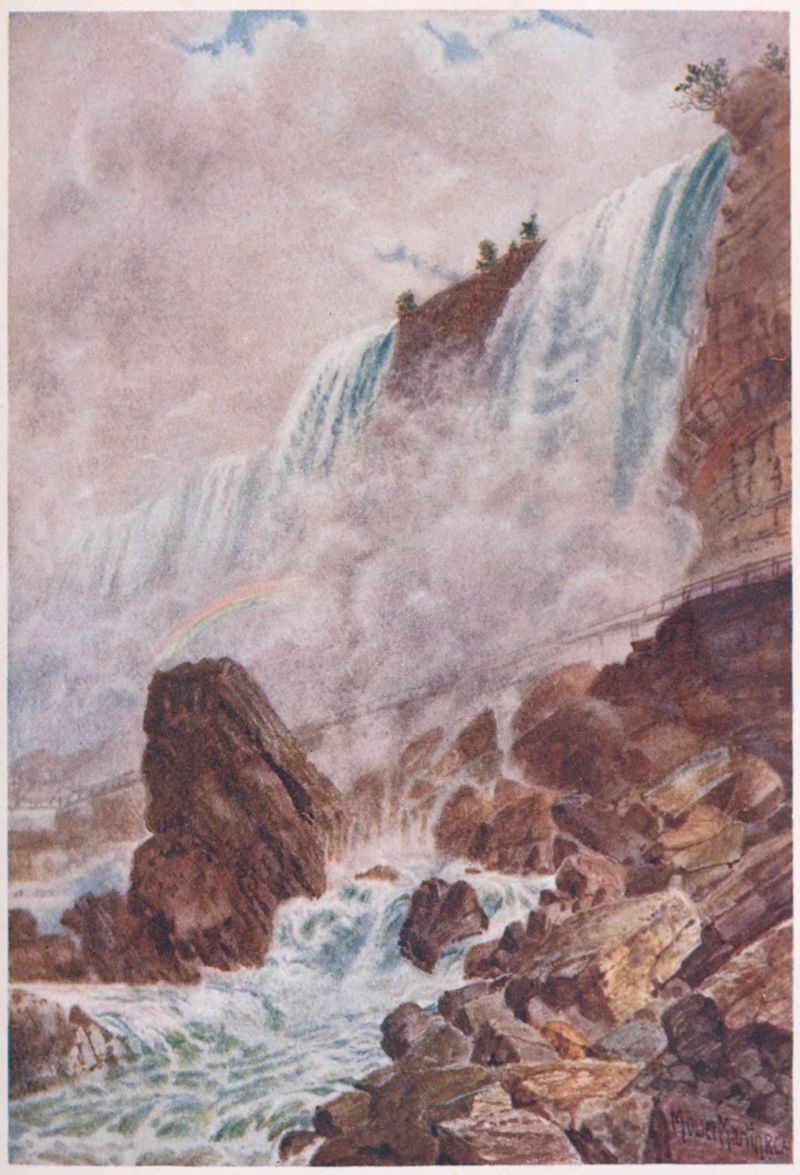

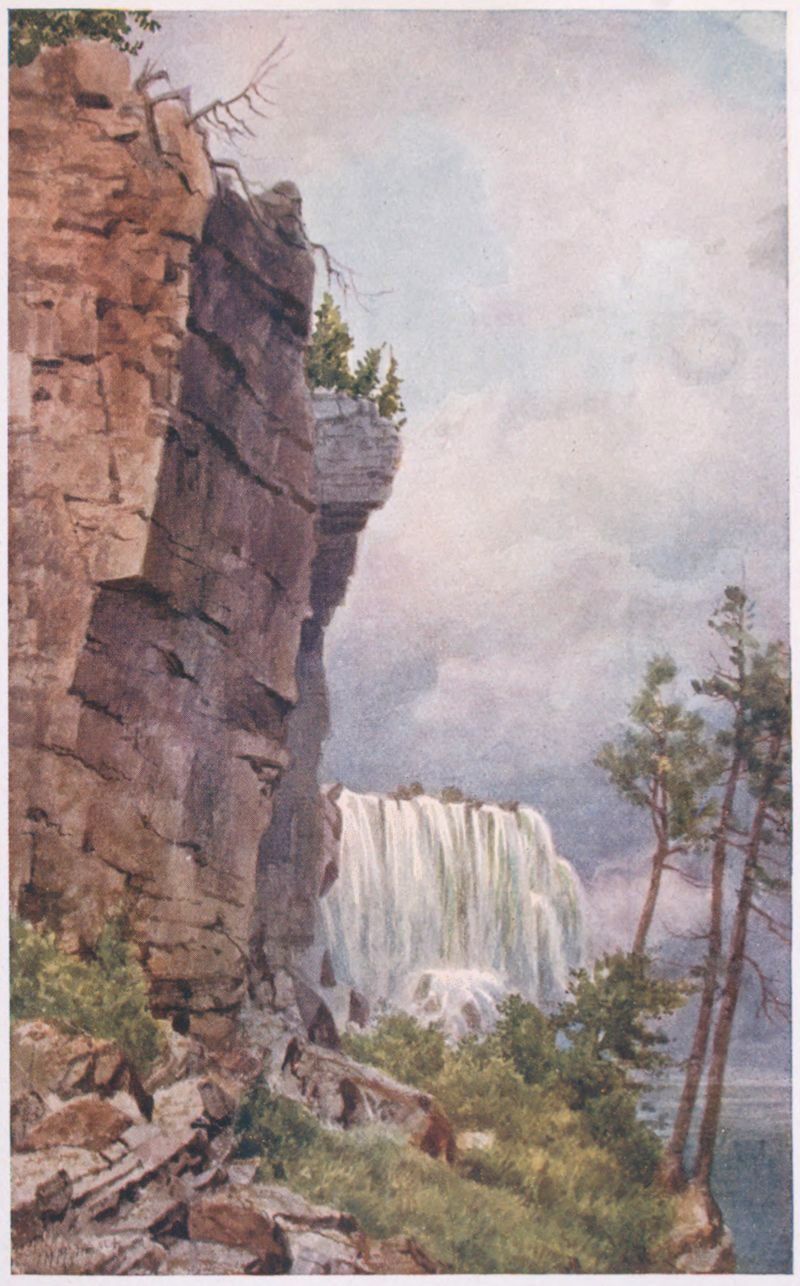

| 37. | Niagara Falls | 166 |

| 38. | A Glimpse of Niagara from under Luna Island | 168 |

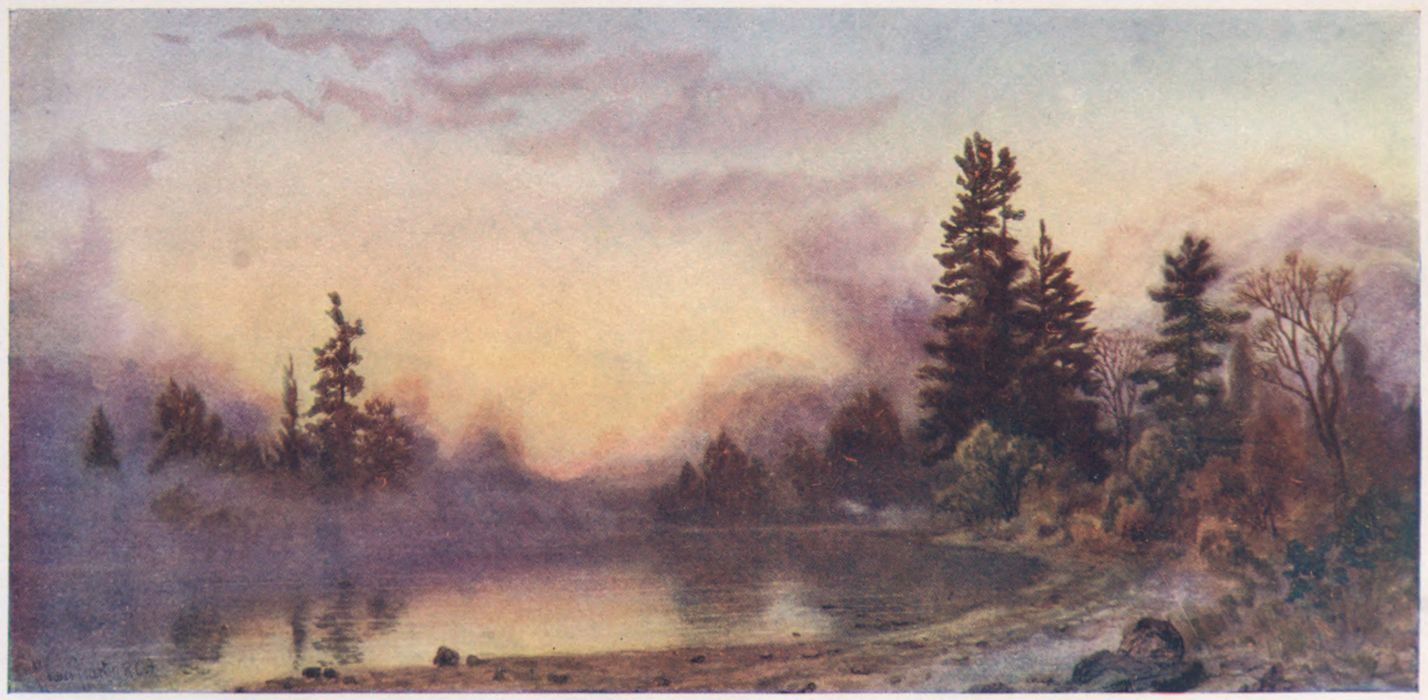

| 39. | Evening Mists, Muskoka | 178 |

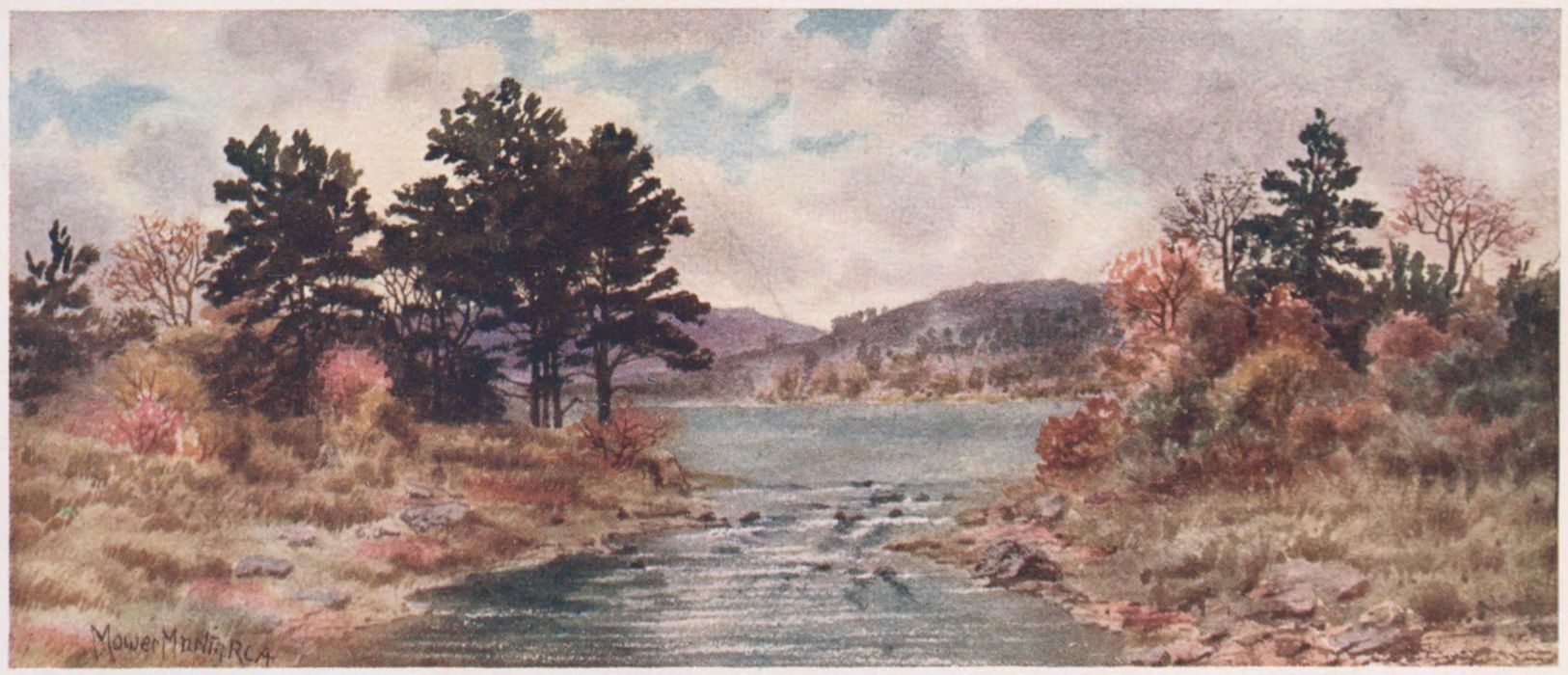

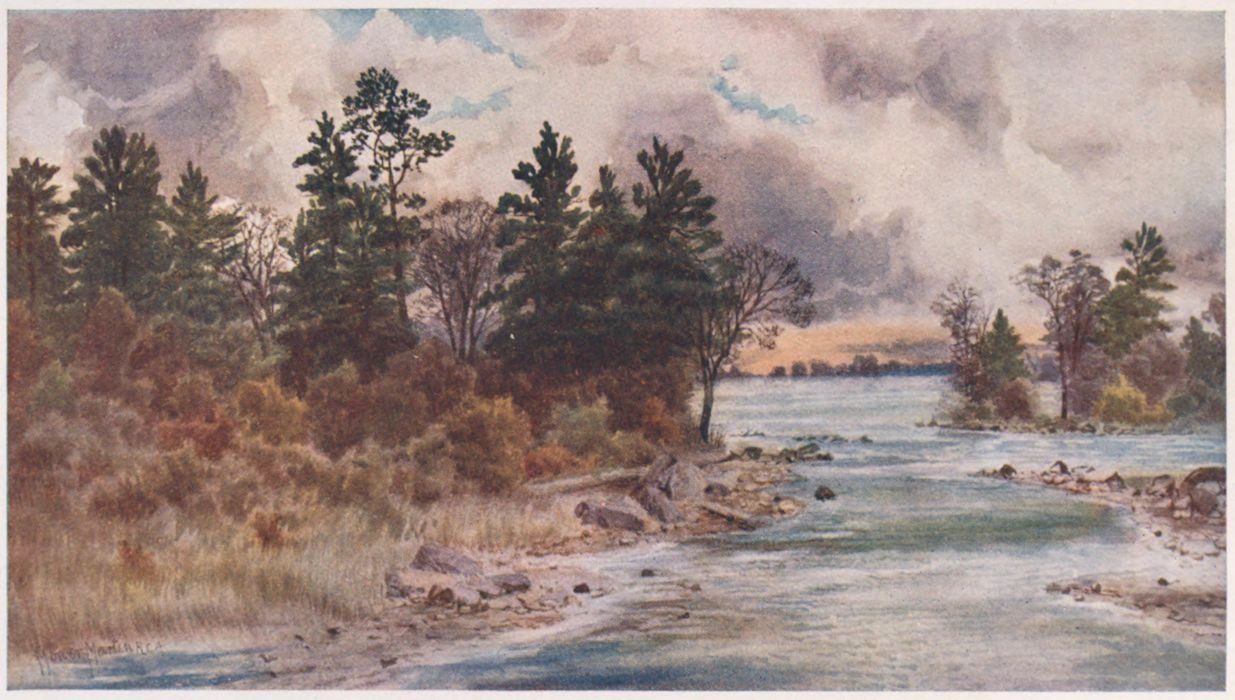

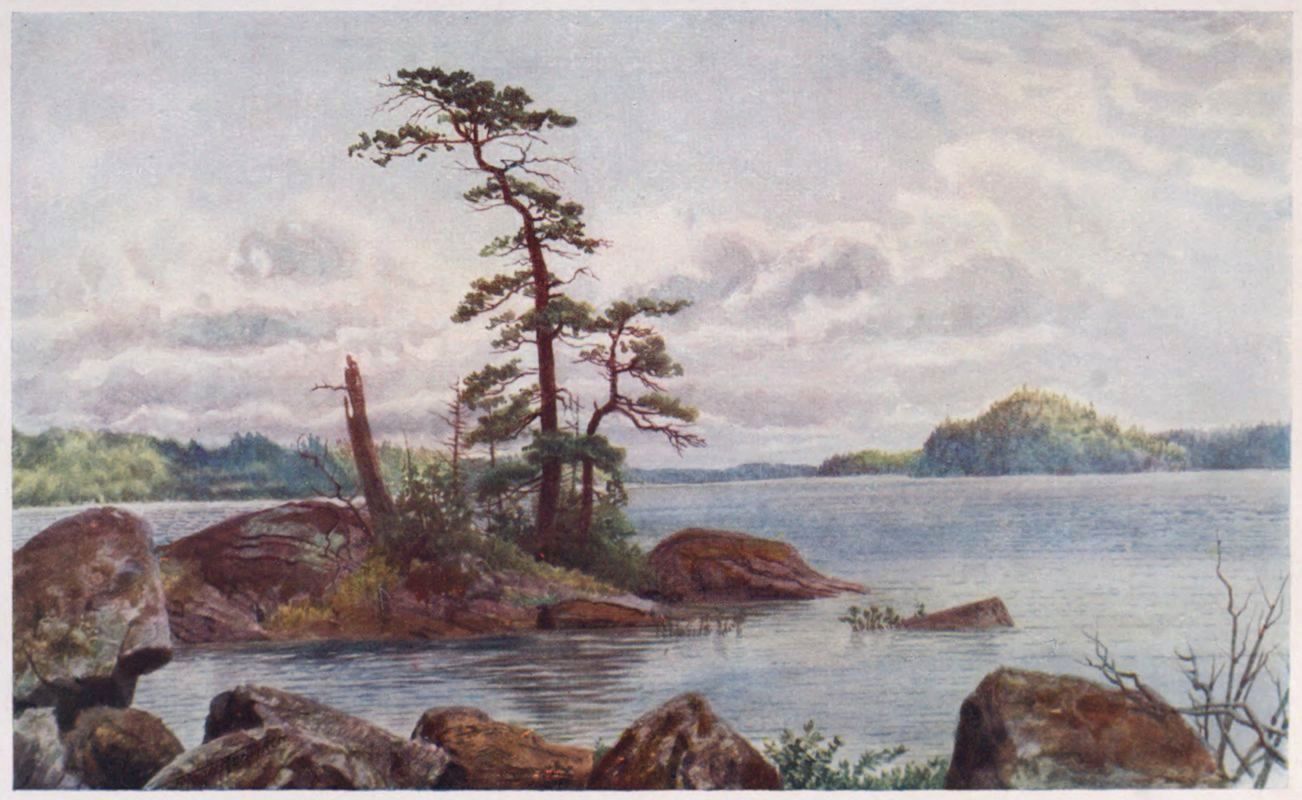

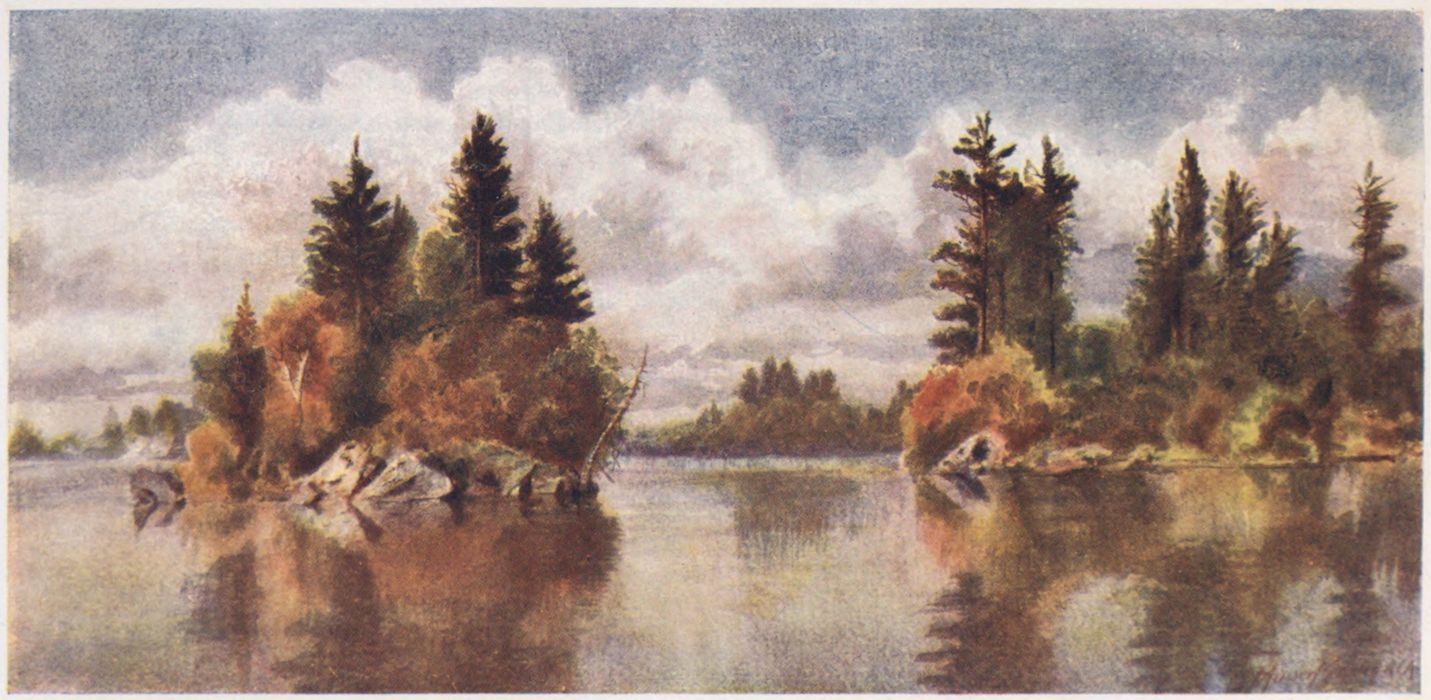

| 40. | Muskoka Lake, North Ontario | 180 |

| 41. | Showery Weather, Muskoka Lake | 182 |

| 42. | Autumn on Lake of Bays, Muskoka | 186 |

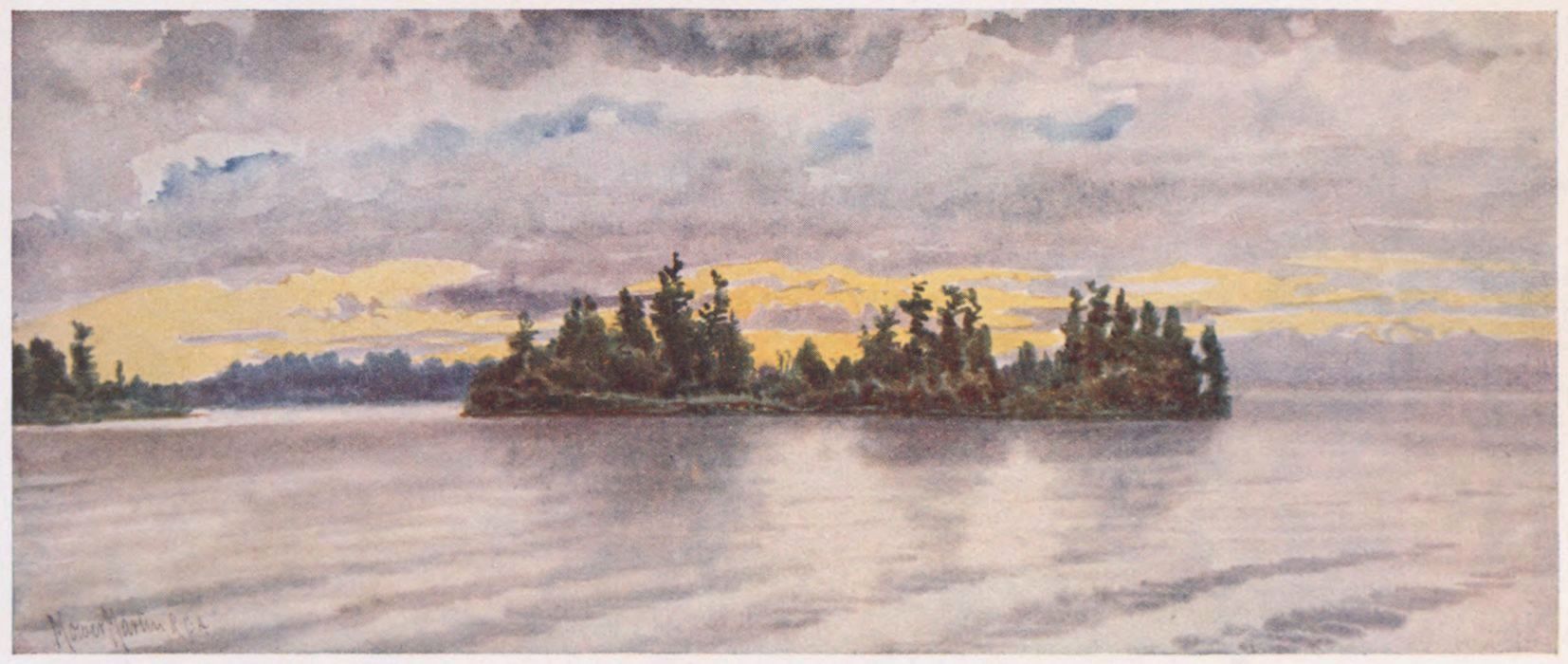

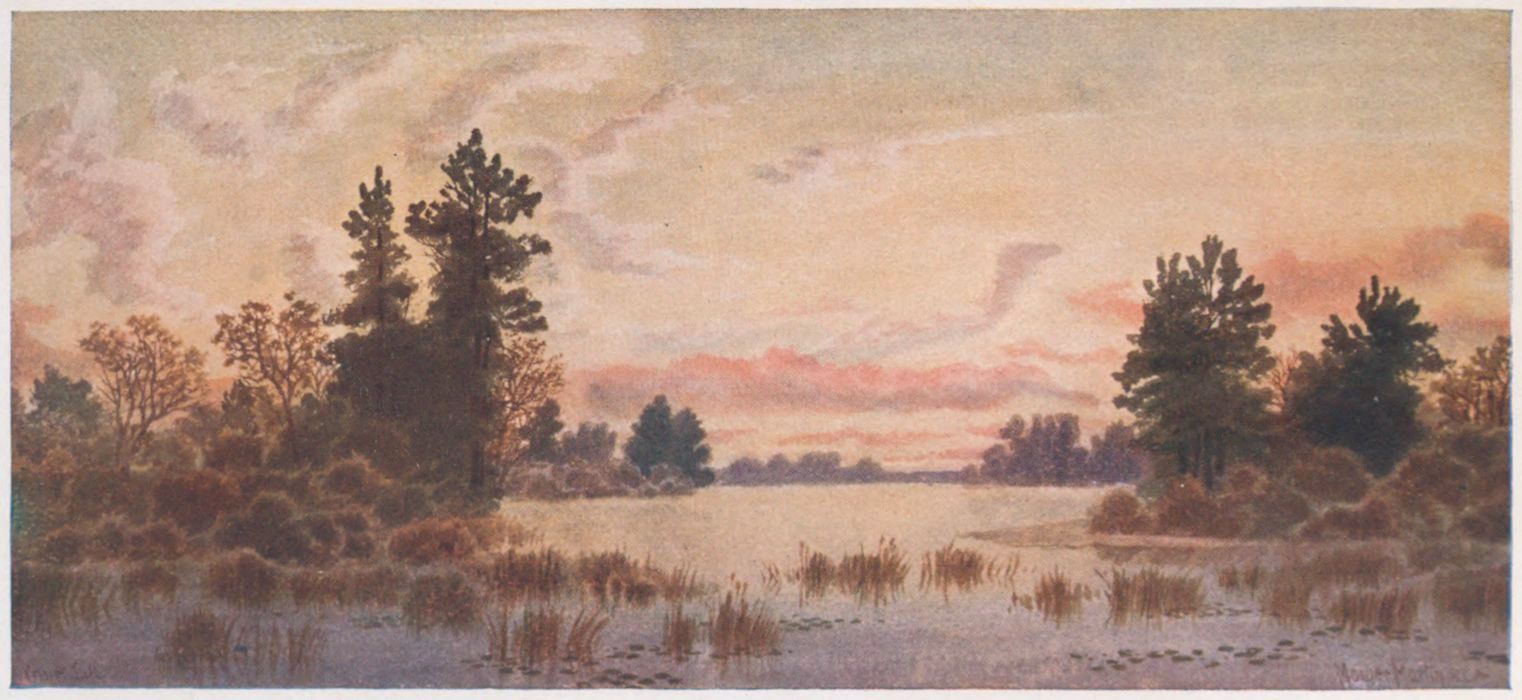

| 43. | Sunset on Canoe Lake, Parry Sound | 190 |

| 44. | Portage on Surprise Lake | 196 |

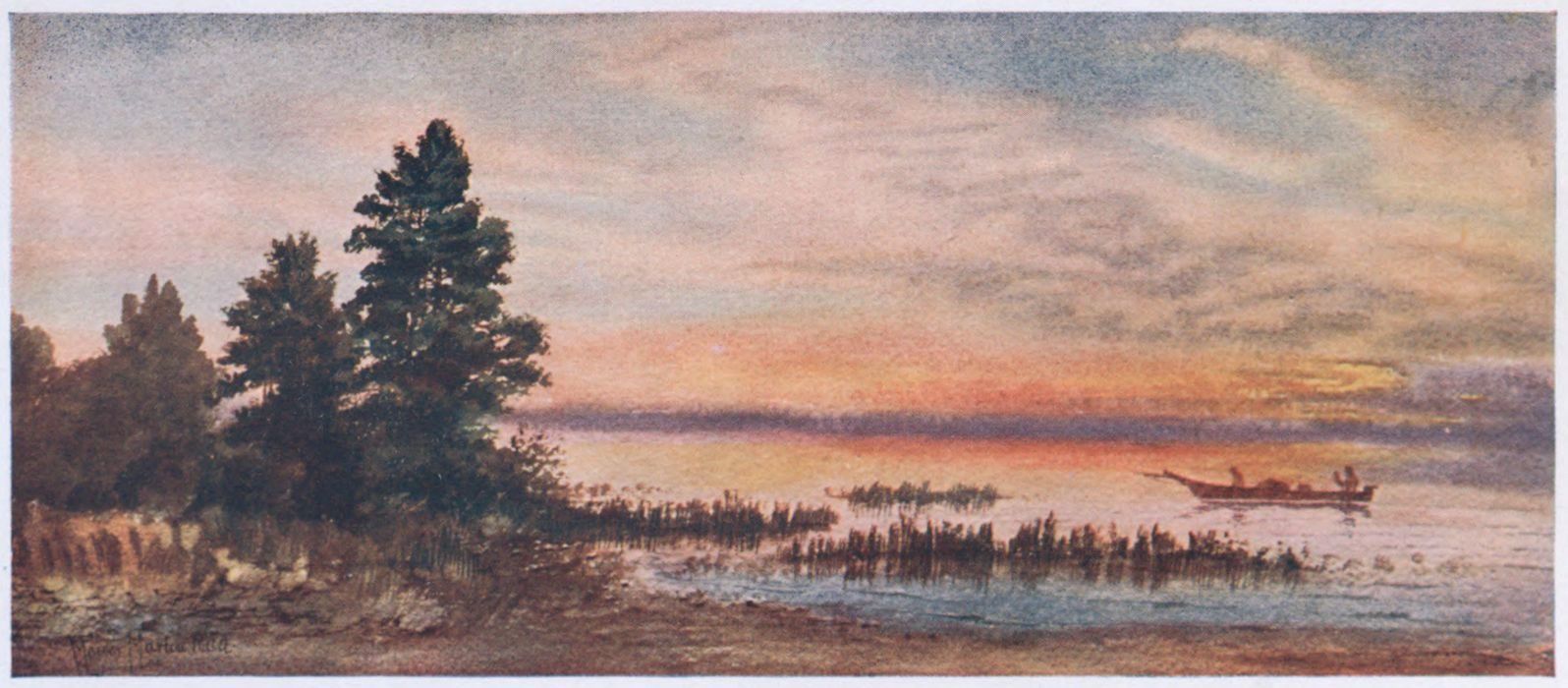

| 45. | Sunset on Lake Superior | 198 |

| 46. | North Shore, Lake Superior | 200 |

| 47. | In the Moose Country, near Lake Superior | 202 |

| 48. | Cariboo Island, Thunder Bay | 204 |

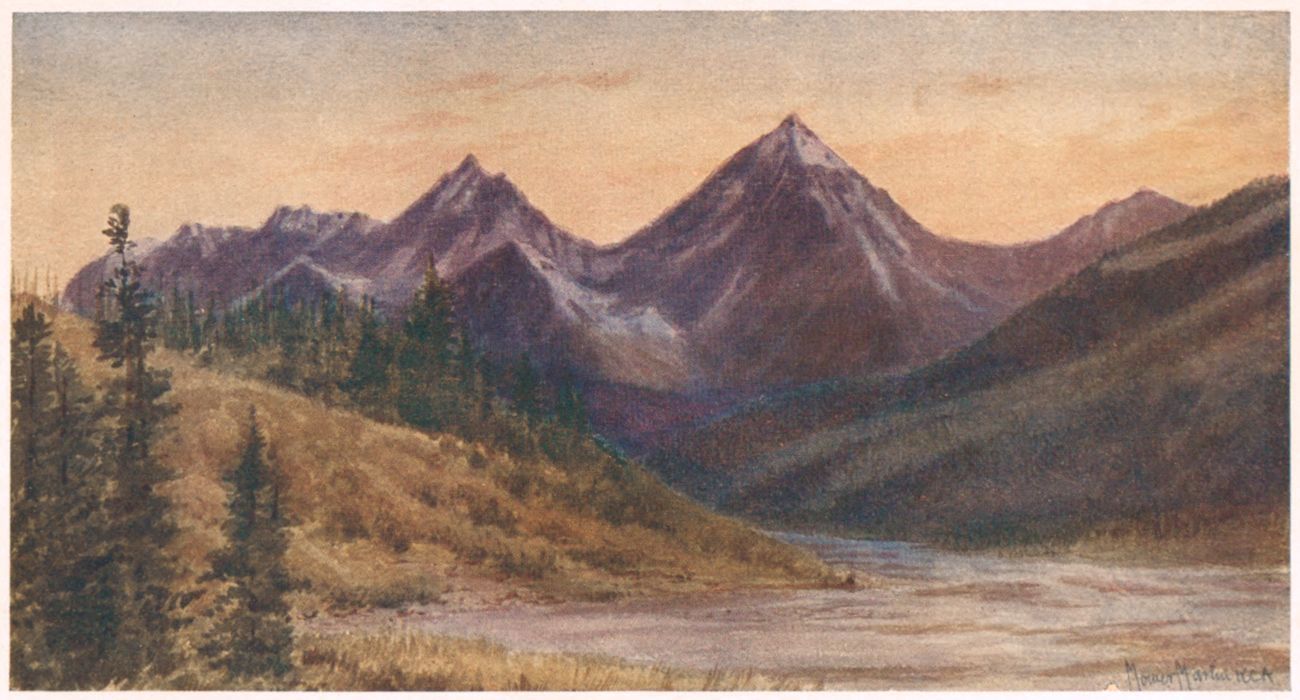

| 49. | Van Horne Range (Evening) | 206 |

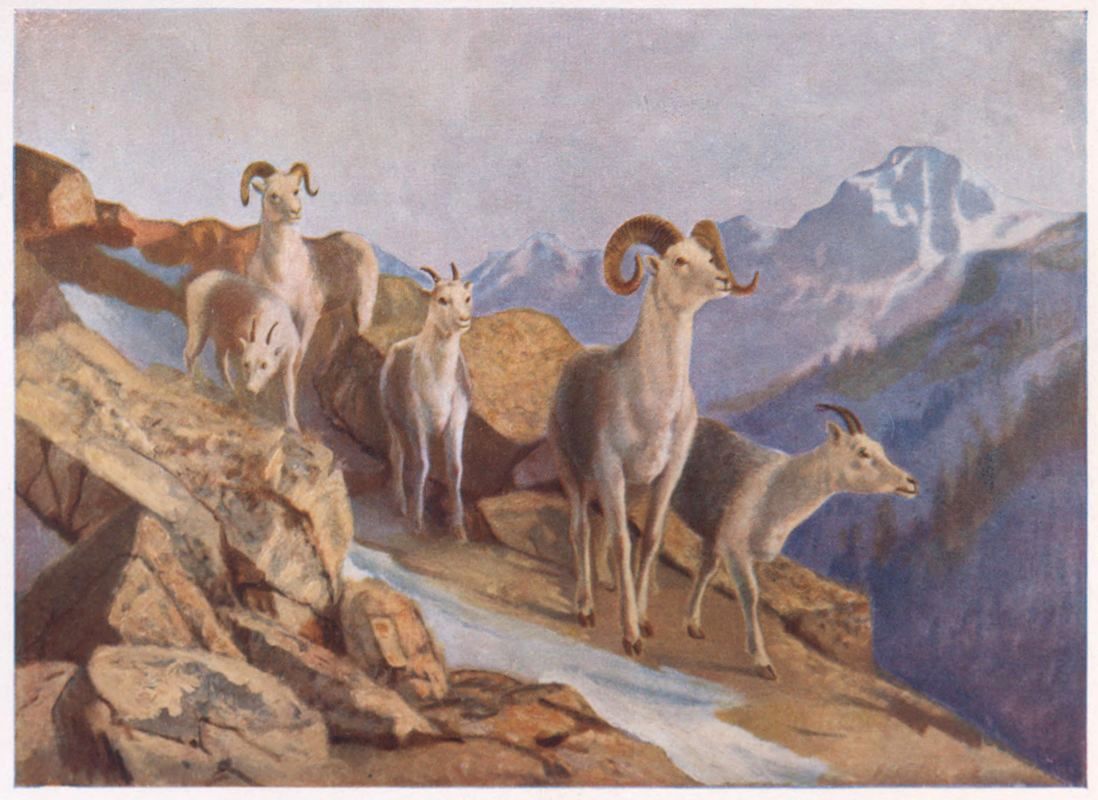

| 50. | Mount Temple, with Wild Goats Feeding | 208 |

| 51. | Mounts Aberdeen, Lefroy, and Victoria, on Lake Louise | 210 |

| 52. | Pitt River and Golden Ear Mountains | 212 |

| 53. | From the Foot of Eagle Peak, Selkirk Mountains | 214 |

| 54. | Mount Sir Donald, in the Selkirks | 216 |

| 55. | Winnipeg: Corner Main Street and Portage Avenue | 218 |

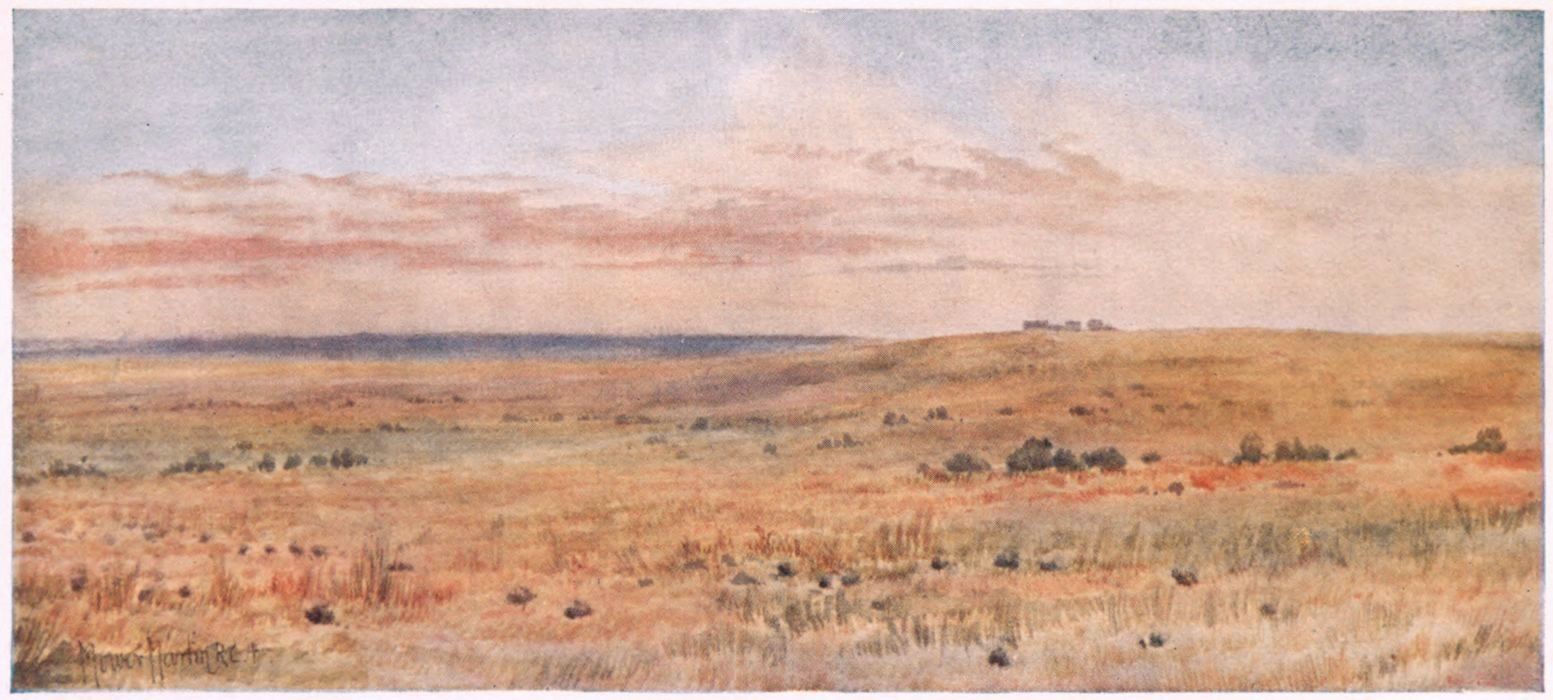

| 56. | Out on the Prairies | 220 |

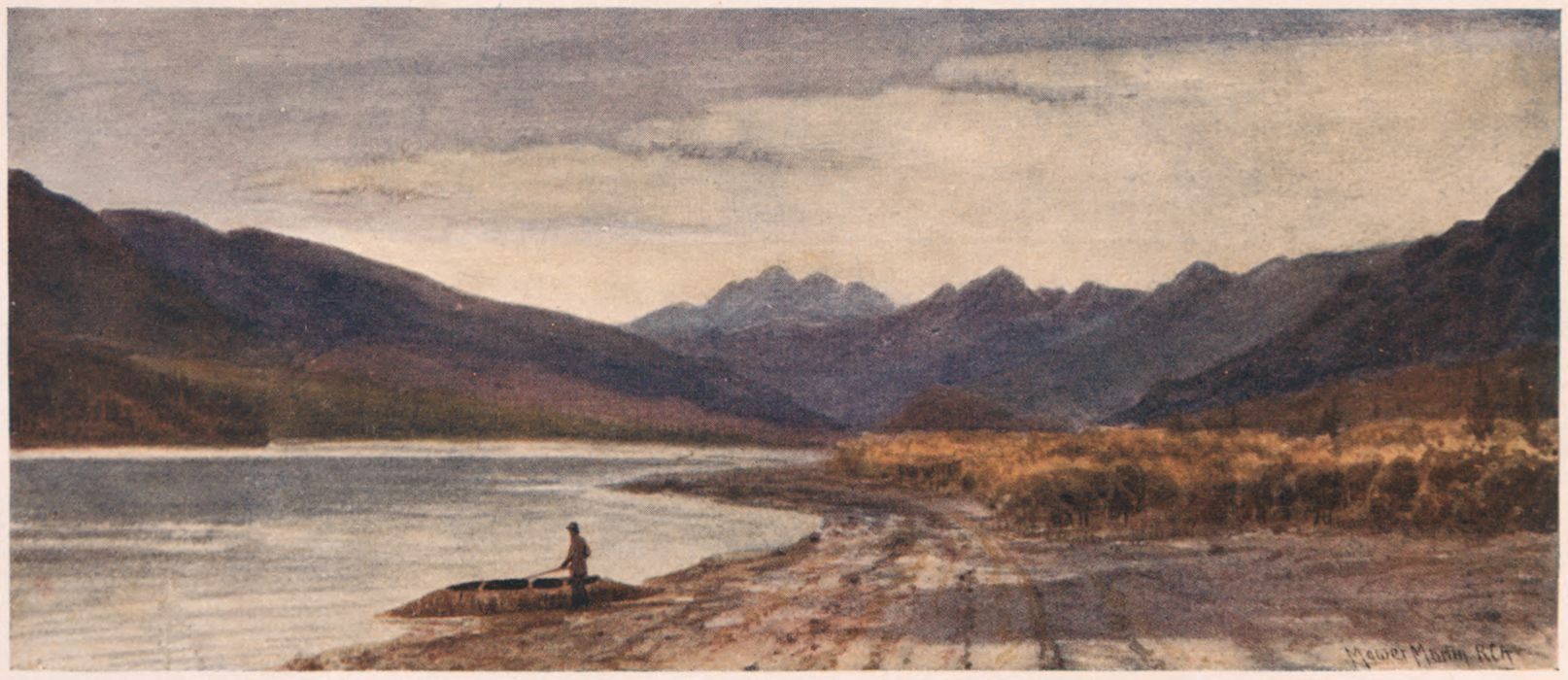

| 57. | On Arrow Lake, Columbia River | 222 |

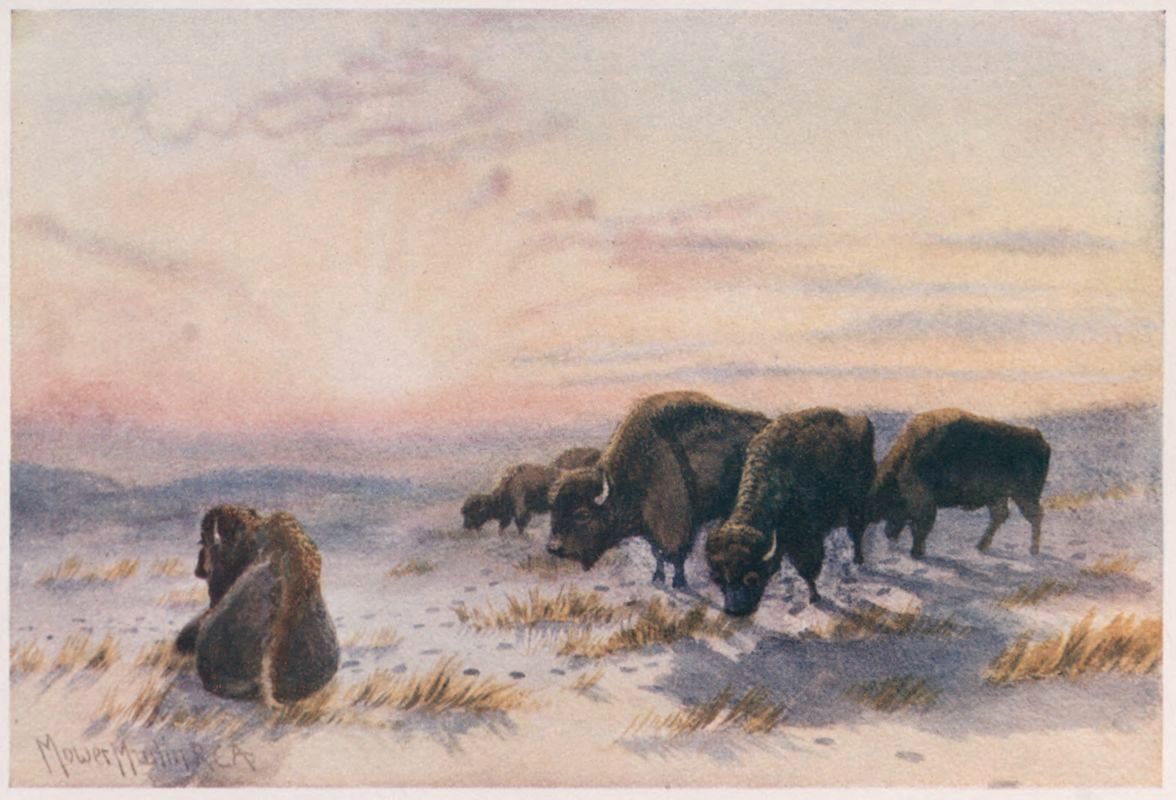

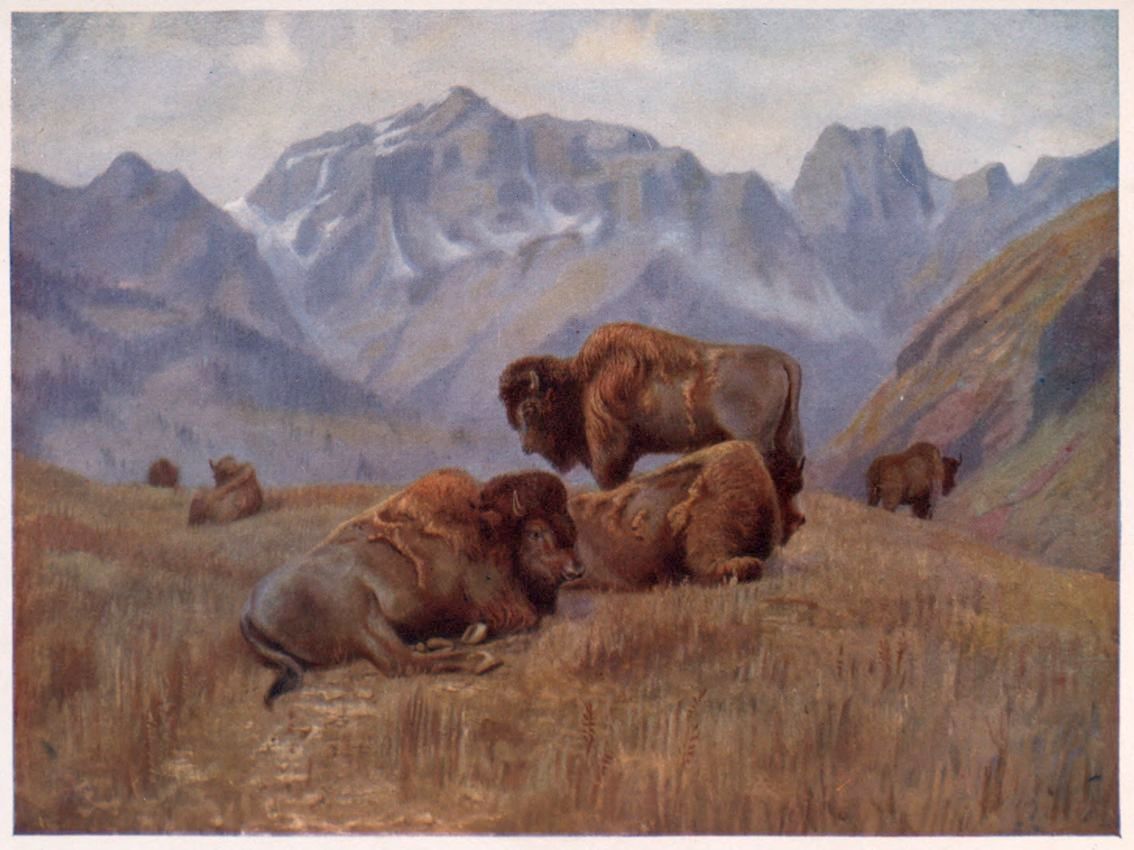

| 58. | Buffalo Feeding in Winter | 224 |

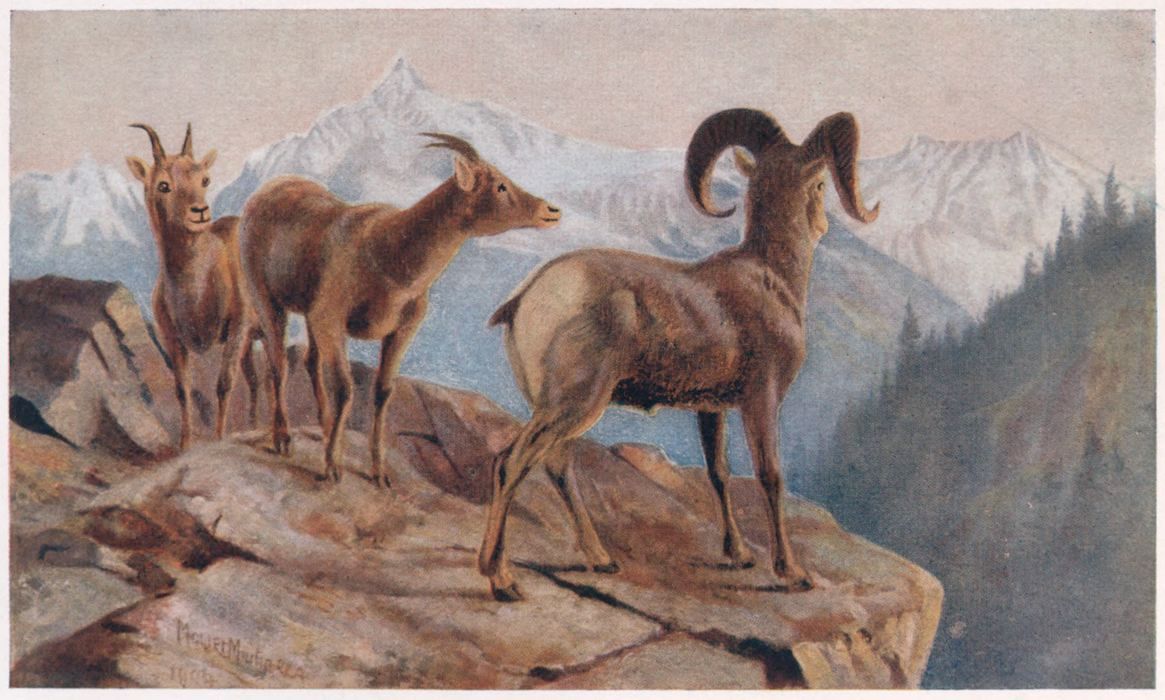

| 59. | Mountain Sheep at Home | 226 |

| 60. | The Valley from Rogers Pass | 228 |

| 61. | Pitt Meadows, on the Fraser River, British Columbia | 230 |

| 62. | Back Country Farmyard, Winter | 232 |

| 63. | Source of the Beaver River | 234 |

| 64. | Buffalo in Summer-time, on Bow Range, near Banff | 236 |

| 65. | Ottertail Range, Rockies, British Columbia | 238 |

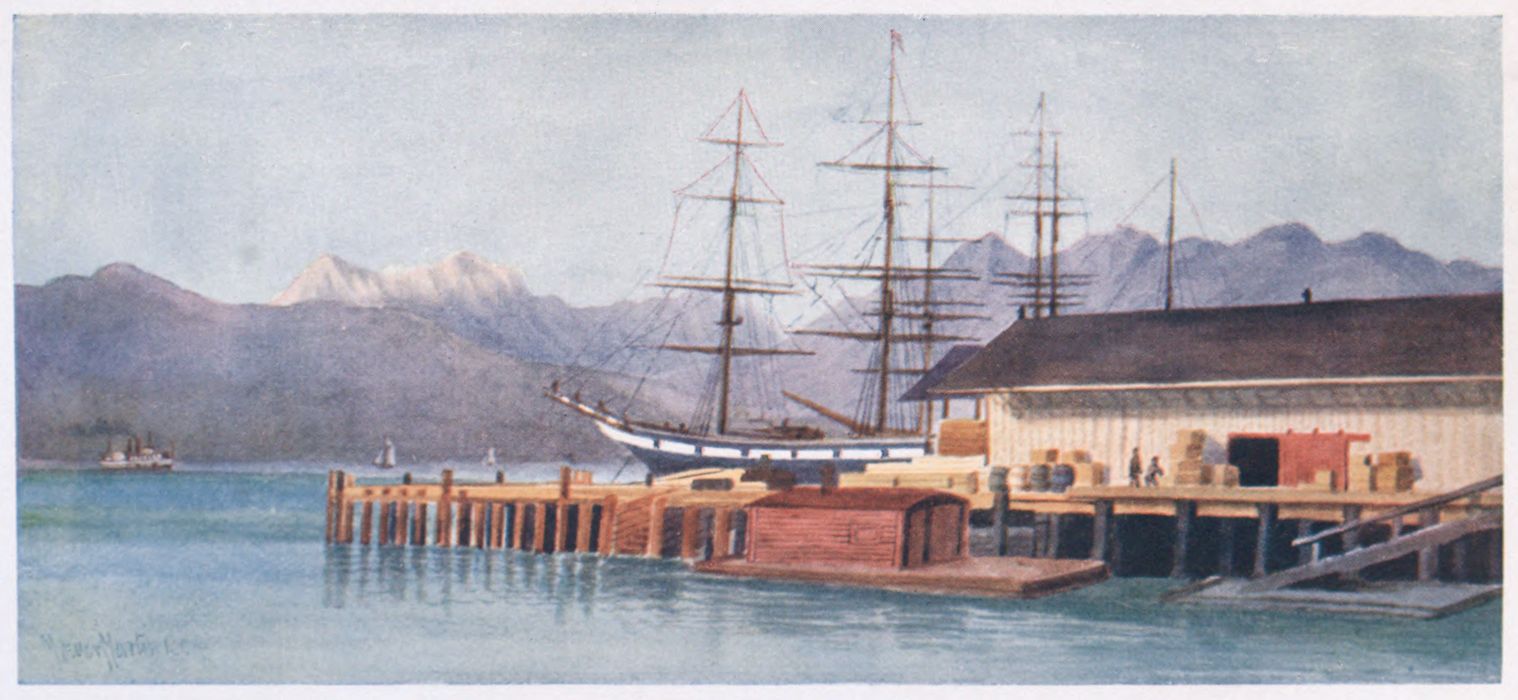

| 66. | Hastings Wharf, Vancouver | 240 |

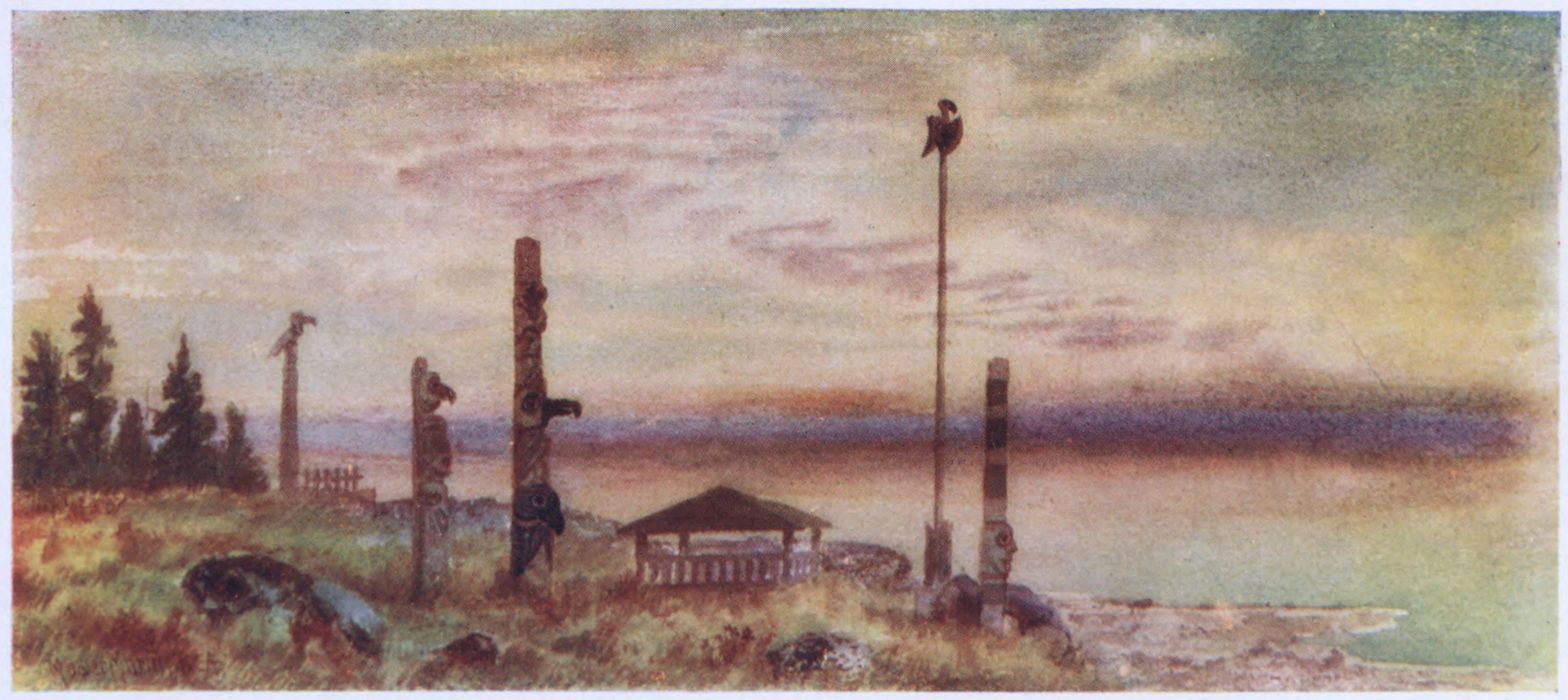

| 67. | Burial-ground of Siwash Indians | 242 |

| 68. | Outlet of Lake Agnes | 244 |

| 69. | Fanning Sheep coming down to Feed | 246 |

| 70. | Glacier Crest, Illecillewaet | 248 |

| 71. | Great Illecillewaet Glacier | 250 |

| 72. | Lake Louise, Laggan | 252 |

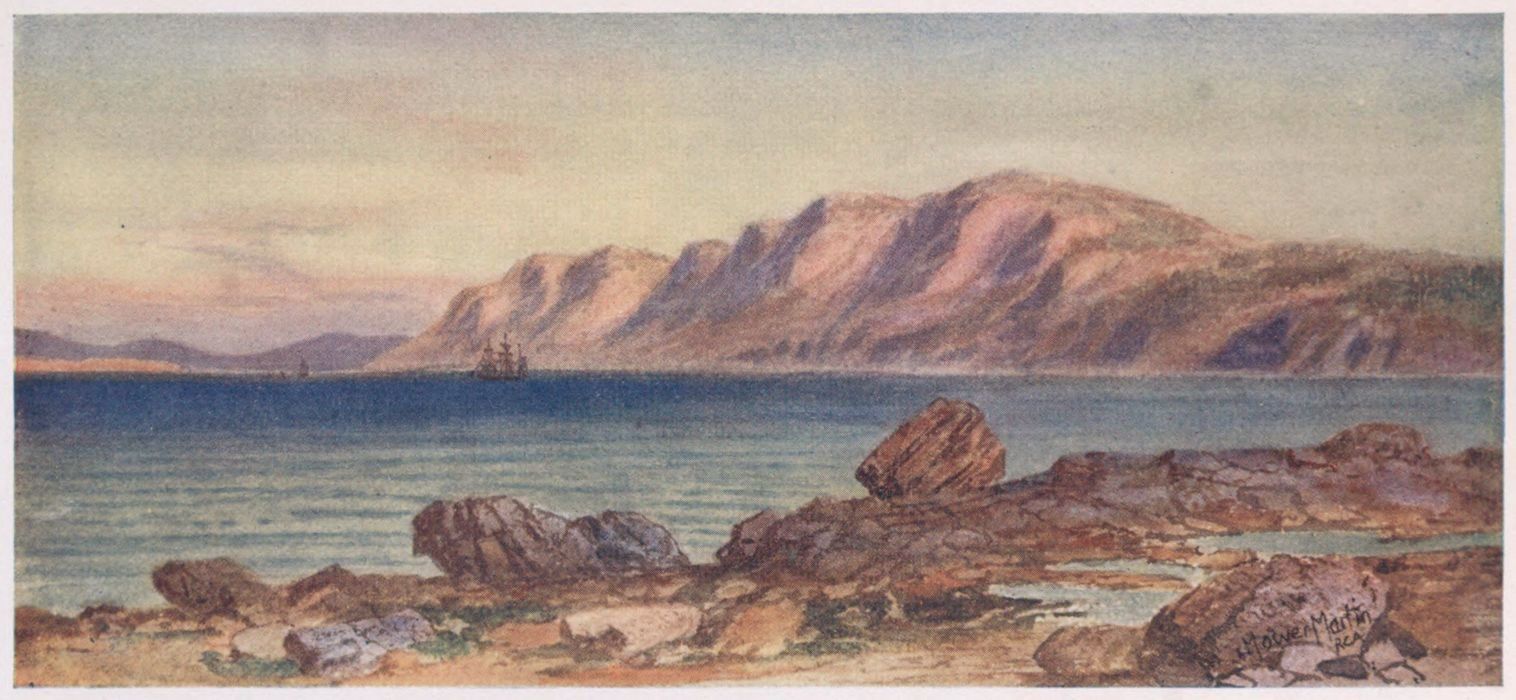

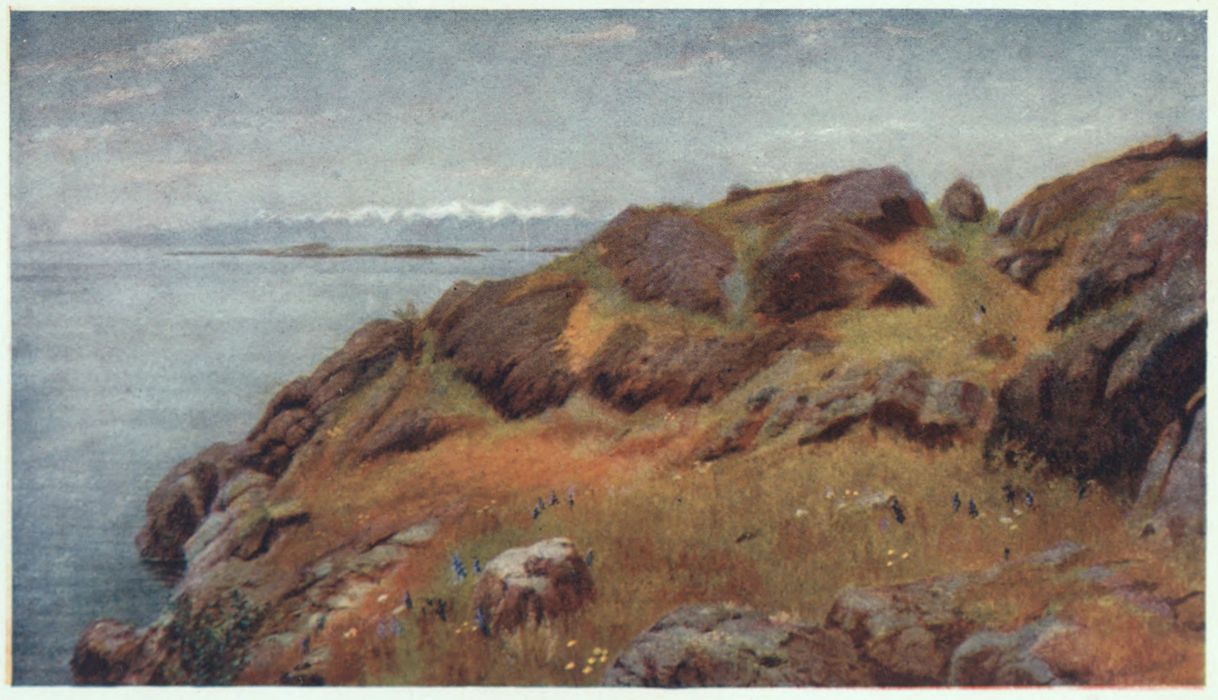

| 73. | Coast near Sechelt, British Columbia | 254 |

| 74. | Coast of Vancouver Island | 256 |

| 75. | Siwash Village, Pacific Coast | 258 |

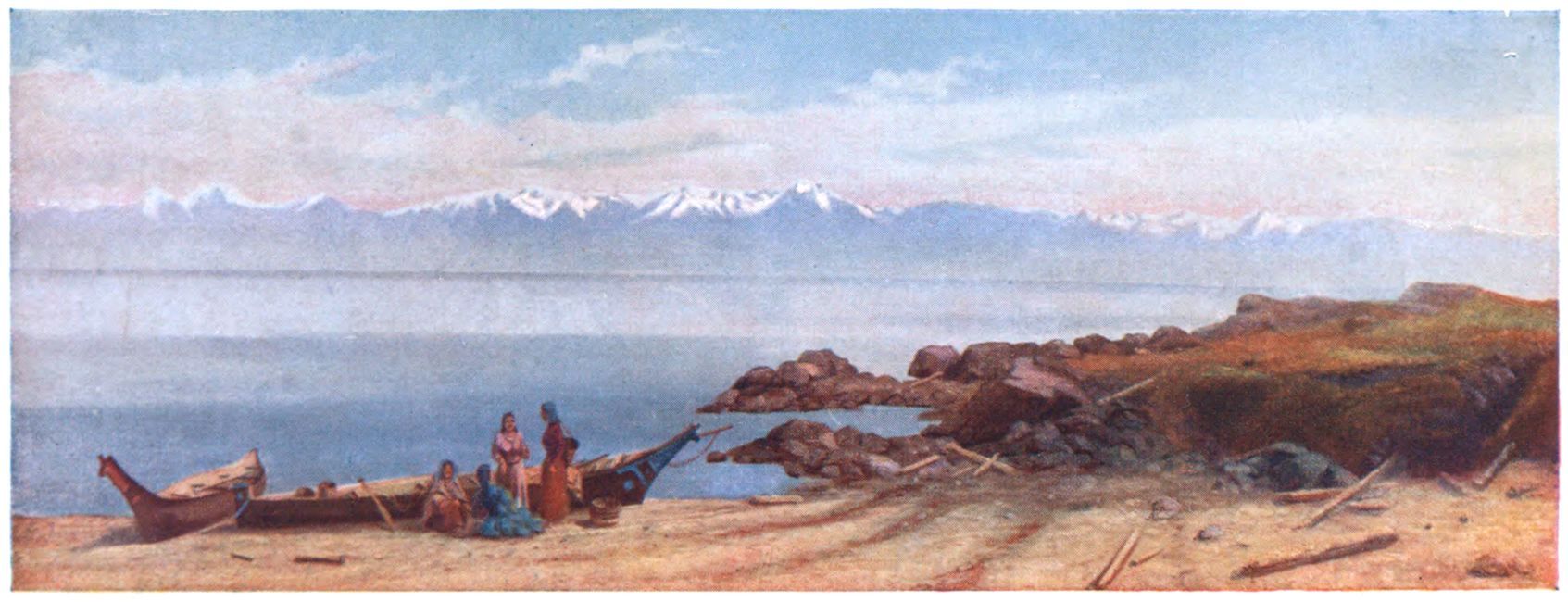

| 76. | Olympic Mountains, from Coast near Victoria | 260 |

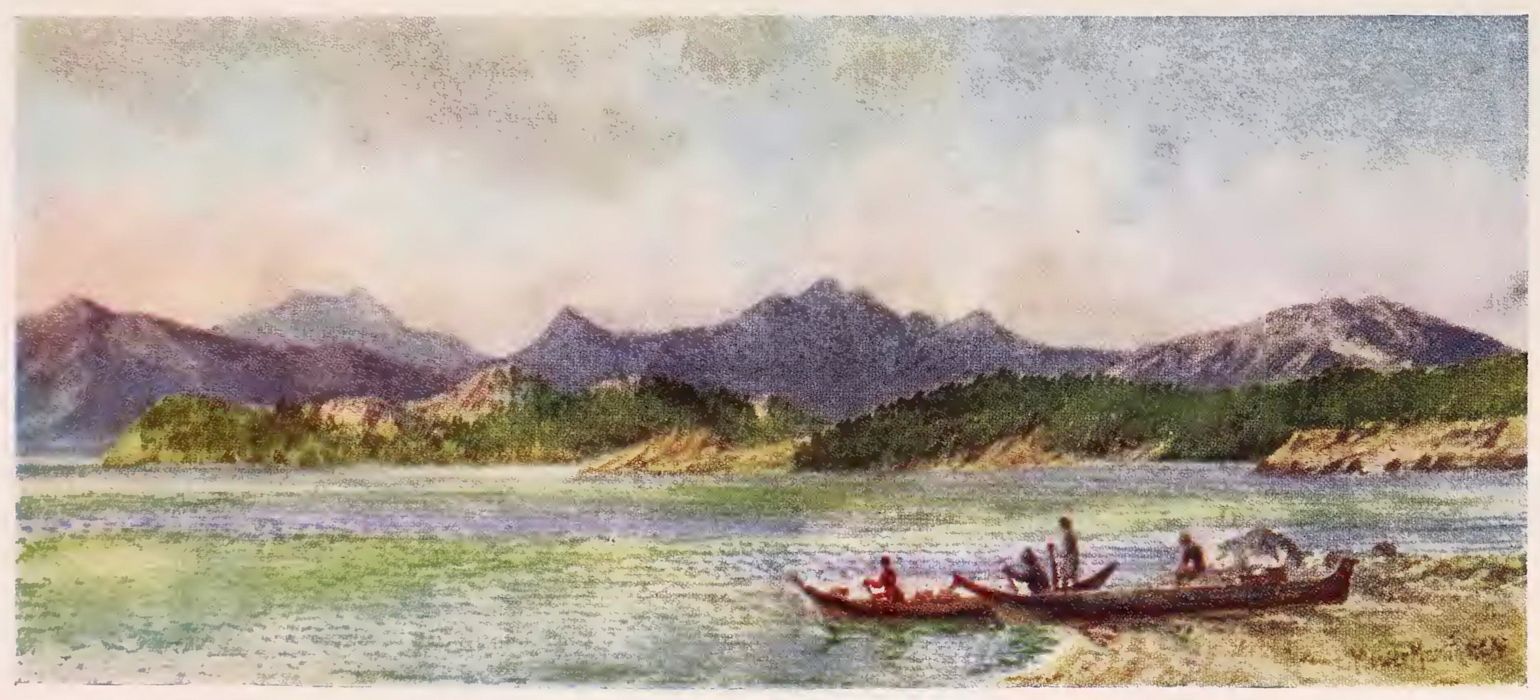

| 77. | Pacific Coast near Nelson’s Island | 262 |

Thou land for gods, or those of old

Whom men deemed gods, of loftier mould,

Sons of the vast, the hills, the sea,

Masters of earth’s humanity:

I stand here where this autumn morn,

Autumnal garbs thy hills adorn,

And all thy woodlands flame with fire,

And glory of the world’s desire.

Far northward lie thy purple hills,

Far vasts between, thy great stream fills,

Ottáwa, his fleet tides impearled,

From deep to deep, adown the world.

O land, by every gift of God

Brave home of freemen, let thy sod,

Sacred with blood of hero sires,

Spurn from its breast ignobler fires.

Keep on these shores where beauty reigns,

And vastness folds from peak to plains,

With room for all from hills to sea,

No shackled, helot tyranny.

Spurn from thy breast the bigot lie,

The smallness not of earth or sky

Breed all thy sons brave stalwart men,

To meet the world as one to ten.

Breed all thy daughters mothers true,

Magic of that glad joy of you,

Till liberties thy hills adorn,

As wide as thy wide fields of corn.

Let that brave soul of Britain’s race,

That peopled all this vastness, trace

Its freedoms fought, ideals won,

Strength built on strength from sire to son

Till from thy earth-wide hills and seas,

Thy manhood as the strength of trees,

Thy liberty alone compare

With thy wide winnowed mountain air,

And round earth’s rim thine honour glows,

Unsullied as thy drifted snows.

Wilfred Campbell.

CANADA

INTRODUCTION

A country of dry frost in winter, and of fruitful heat in summer, with numerous delightful climates in between—this is the rising nation, Canada. And of a similar strange mixture are its people, at once the most hard-working and yet most hopeful of any people upon earth, in the mind of him who deeply ponders upon their unique conditions. The destiny of a young and vigorous people animated by high ambitions must be either lofty or sordid. It is between these two extremes that national tragedy lies. Canada promises either to be the theatre of one of the greatest commonwealths the world has seen, or else, failing this, to be the land where race has died out in a crude, vulgar cosmopolitanism; where patriotism has been destroyed by a foolish party system, and all idealism crushed out in a hard materalism. There is no blinking the situation. We are the youngest people in the world, and yet we have some of the gravest problems to solve; and it is all because we are strong and proud, and have taken the bit in our teeth with a brave spirit and an ambition to rule ourselves, and be all or nothing.

The Scotland of America, Canada should well be called, both from its northern position on this continent, its rugged, austere lands, its severe, invigorating climate, and the fact that the greater portion of its people, with the exception of the French, are of the blood which has made famous in history that remarkable home of great souls, North Britain.

There is no doubt that Canada is the Scotland of America, and that, as in Scotland, the very semi-poverty of her people, or rather lack of great wealth, coupled with her bracing and vigorous climate, has had much to do with the production of a hardier, more determined race than the country to the south on the whole produces. The north has ever been the home of liberty, industry, and valour. History teaches that conquerors have not usually come from the south. With all his faults—and he has his own—the young Canadian is unusually self-sustaining. He is over-eager to leave home and struggle for himself. The fate of his future for the most part depends purely upon his personal ambition and mental energy. Where this is combined with a highly ethical conception of life, a personality of uncommon force of character is likely to be produced. And there is not wanting evidence that such a type may develop here in Canada.

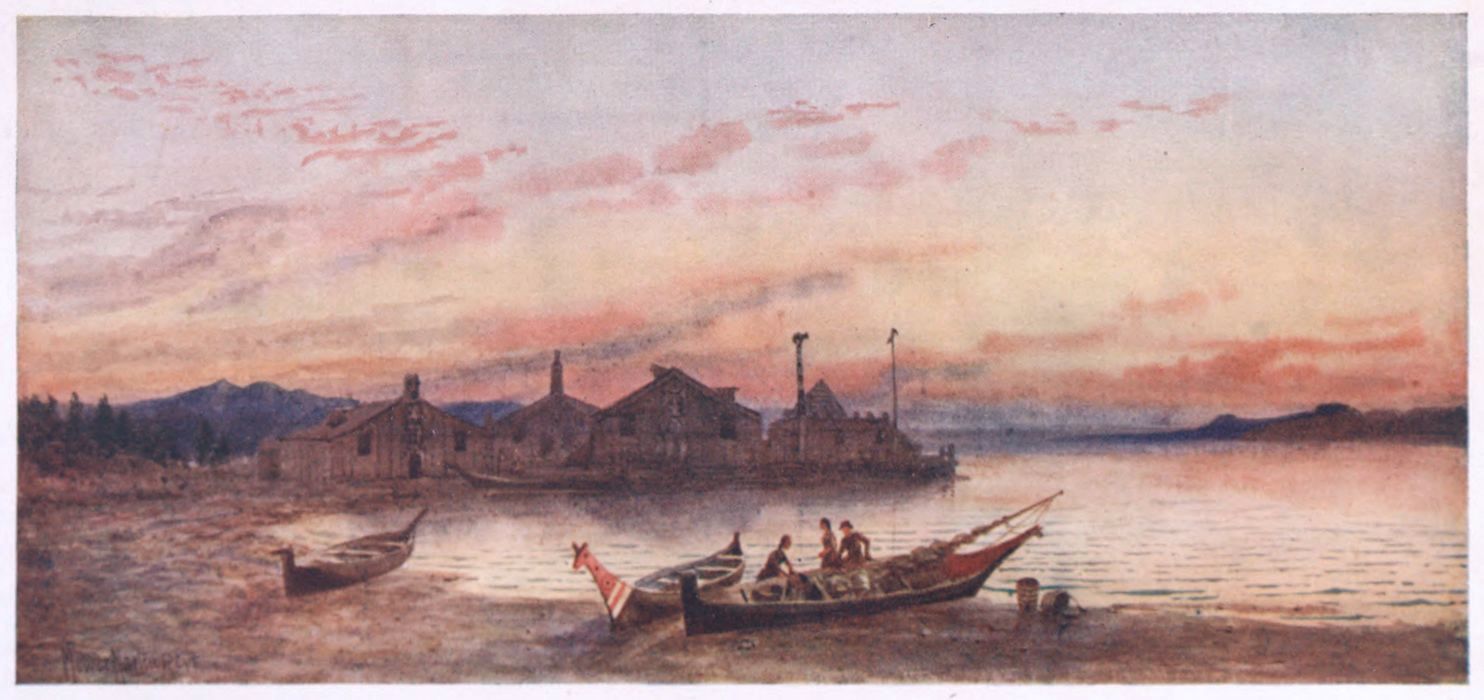

NORTH OF HOWE SOUND, PACIFIC COAST, BRITISH COLUMBIA

It is this possibility as to character, this promise of a strong, individual, intellectual, ethically-governed manhood, that gives most hope for the Canada of the future. Not all the millions of acres of wheat-lands of her prairies, not all her cities of smoking factories and busy commerce in the east and west, will succeed in making her dominant in the world-arena, as will the strong personality, the unflinching character, of her coming men.

The northern peoples have always been the truest, the wisest, and the deepest thinkers; and their imagination has always been the most beautiful and the sanest, because the nearest to nature. They have ever been the strongest in personality and the self-rulers of the world. Northern Europe, Northern Britain, Northern Ireland, are all historical evidence of this fact. Even in the United States this is so far true; and Canada cannot escape this great law of life and nature.

But it is not all a mere matter of zone or climate; it is rather owing to the stock of people, who by a natural instinct seek, or brave, through preference, those more rugged temperate climes. It is this heredity, this temperament, which is needful to make a people really great. Never in a soft, enervating clime has man sought for God and interpreted His personality and relationship to life so clearly, so humanly, and so sublimely, and in so personal a manner, as he has done in the opens of Northern Europe and America.

Never has man been so wide awake as an individual to the whole responsibilities and possibilities of his existence as he has been among those more rugged, self-ruling, self-searching, dominant, nature-subduing races of the northern zone. It is this, after all, which makes a people really great—this slow, sure, true development of a race individuality. May the people of Canada retain this strong individual interest in the race-ideals of the past, and emulate the greatness of their ancestors.

But the Scot is not the only man who has made Canada what it is to-day. The earliest discoverer here was the Norman, that strong world-conqueror of the past; and he, the cousin in blood of the Scot, is his partner and rival in the future destinies of this newer Britain, as he has been in that older Britain of William the Conqueror.

MOUNT CHEOPS AND THE HERMIT RANGE

Then there are the English, the sturdiest, the most independent stock of men in the whole world; and next follows the north of Ireland Scot, who has perhaps more than any other class dominated and moulded the character, and affected the speech and accent, of the Canadian people.

After these comes the Irishman, the genial southern Celt with warm heart, who has ever stood for culture, and also for liberty everywhere save, sad to say, in his own land. Ireland has been represented in Canadian history by a remarkable band of gifted men, such as D’Arcy M‘Gee, Edward Blake, and Archbishop Connolly. Last but not least, the United Empire Loyalists, who came in from the republic to the south, rather than live outside of British rule, and who are of British stock, have been a prominent element in the making of the Canadian community.

But remarkable as is the personality of the Canadian of the past and present, it is not the Canadian himself that attracts the attention of the outside world; it is rather the physical advantages of the country in which he is so fortunate to dwell.

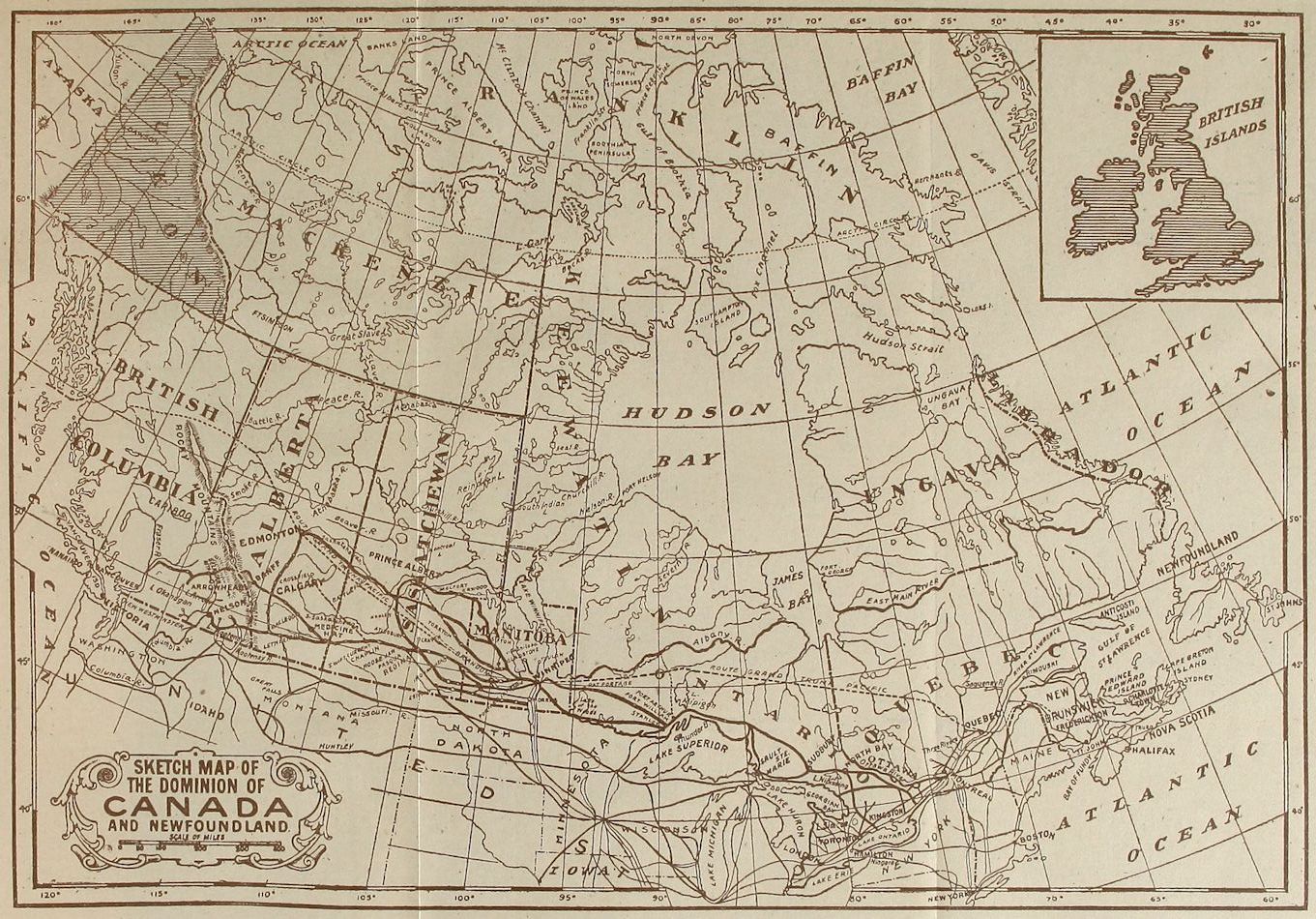

That which must, first and last, compel the wonder and admiration of the old-world traveller in this new land, is its vastness, its distances, the grandeur of the scale upon which the natural features which characterise the broad half of this great western continent known as Canada are formed. He has possibly heard that the Dominion stretches from ocean to ocean, that it contains great inland seas, and a chain of mountains rivalling any in the world; that its riverways are the vastest water highways on the globe; yet it is a question if he is ever prepared for the reality.

We ourselves scarcely realise the wealth of the Dominion in both scenery and natural resources. We have fallen into our inheritance without any of the struggle and sacrifice of our forefathers. Even the memory of that struggle is, sad to say, passing. The trackless forest is no longer assailed by the puny hands of a few settlers, endeavouring to carve out a home for themselves in the wilderness. Railways and government surveys have changed all this. The outsider must realise that we, as a people, have passed into a more advanced, if less picturesque, stage, and that even the literature of our country no more represents the backwoods and the Indian; and he who would so represent us misrepresents our true condition. The life of the canoe and the wilds is long past, and as alien from the great modern life of cultured Canada as it is from the civilisation of London. We have a few writers who, without any true human grip of the Canadian life as it is, and seeking what they falsely think makes their work unique, strain to make out that the spirit of Canada is yet to be found in the wilds; but these are mere posers, who do not count in our real advancement—flies on the national wheel, such as are found in every country. Even these men produce their literary pabulum in the heart of American or Canadian cities. The truth is that we have a greatness of nature about us in Canada; but it is at our very doors; and in the environs of the capital of Canada will be found as grand natural scenery as is to be seen anywhere in the world.

SUNSET ON THE GREAT SELKIRK GLACIERS

Our chief characteristic in the eyes of the stranger, is that we are still regarded, perhaps wrongly, as a virgin land. To the rest of the world there still hangs over our country that delightful golden mist of great and boundless possibilities which makes the Avalon of desire, the Eldorado of dreams, a field for adventure and enterprise where every man has a chance, and hope as a guiding star shines bright, with success ever in sight. This glamour will always exist where men are dreamers, and discontented with their own surroundings. As the poet has said:

“’Tis distance lends enchantment to the view,

And robes the mountain in its azure hue.”

We have, however, a climate in many ways without compare, either dry or moist, moderate or severe, according to locality; lands rich and waiting for cultivation, virgin forests covered with timber, and in some parts still abounding in game. We have vast mineral deposits as yet undeveloped and unexplored; so that, in so far as the material attractions are concerned, Canada is a country for the strenuous man of the present and future, who is willing to work and struggle not only with nature but with his fellow-man.

The traveller entering Canada from the east, by way of the Gulf of St Lawrence, enters one of the great rivers of the world. Passing the rock and fortress of Quebec, and the district through which the St Lawrence flows, he comes to Montreal, the Canadian metropolis; then on to Toronto, and west to Winnipeg, the centre of the Dominion; and thence to the Rocky Mountains and beyond. In this journey a revelation—I will not say a disillusionment—awaits him.

SETTLER’S FARMYARD, MUSKOKA

The vastness, the grandeur of the scenery, the miles upon miles of country over which he is being rapidly whirled, while the ever-varying panorama materialises and dissolves as he passes, must be a continual source of astonishment and admiration. And though he may have seen the beauty and grandeur of the great lakes, he is scarcely prepared for the scene which awaits him after he passes the wide prairies, through seas of waving grass, and the glorious vision of the Rocky Mountains arises like a vast new dream conjured up by Dante, or touched by the master-hand of that magician, Turner.

It must be admitted that we, as a people, have not been as true as we should have been to the vast and priceless trust which fate and nature have given into our hands, as the possessors of so much natural wealth. We, in common with all inhabitants of new countries, have been sadly wasteful of our forests, which, as a people, we were unfit not only to possess but to control. It would have been well for Canada if, fifty years ago, someone had warned the people of the terrible destruction of timber all over the country, and if we had had statesmen to make laws to restrict this destruction. No man has a perfect right to waste his land or what grows thereon. The law should compel all landowners to provide for future generations. The same ruin has taken place regarding our fisheries, and the lumber industry has been allowed to kill with sawdust all the fish in our streams. But these weaknesses, grave as they are, are those of all young peoples; and we are tardily coming to a sense of our shortcomings in this respect.

We are, however, not without our ideals, and under all the upper current of materialism which dominates our society there is a surely developing discontent with crude methods of legislation, and a determination toward loftier ethical levels of thought and action. This is shown not only in the more earnest pulpit utterance, the higher-class journalistic warnings, and a very few of our literary influences, but also in an awakening toward better and cleaner municipal government and general national responsibility, as is evinced in the Canadian Municipal Union, and in the attempt at better local conditions on the part of some of the churches. We are after all but a younger Britain in this new world, repeating the old race-ideals and race-blunders; and if we succeed in establishing as strong and as elevated a civilisation on this continent as Britain has in the old land, we will have every reason to be thankful.

MOUNTAIN GOATS FEEDING

Our real material and moral welfare, our very future existence, depends, however, largely on the growth and development of our rural population. The great social danger of the near future will be owing to the overgrowth of the material industries. These are rapidly changing the whole order of the social conditions, and deteriorating mankind into but two classes, the merely rich and the poor. This condition threatens, at no distant date, to destroy the whole fabric of society. The only final cure for all this is to get as many of the people as possible on to the land. Every man on his own soil, self-supporting and independent, is the centre of a little social organisation which is self-ruling. Every man removed from the land, and enticed or forced into the city or manufacturing centre, is a pillar torn from the roof-support of the social temple.

The nation of the future, which will rule the world, will be that one which lays most stress on her rural population and her rural wealth; she will be the one in which the great mass of the people till the land. Commerce is all right in its place; but it must be kept in its place. Mining as an industry may be a great asset in the wealth of a country; but it does not make for the best citizenship in either workman or owner. What makes for the highest, healthiest type of manhood and womanhood, is the proper industry for a nation to engage in. My hope for my country is, that she will turn all her energies in the direction of the cultivation of the soil, and that she will become a country of orchards and vineyards and wheat-fields and meadows, and a vast pasture for the herds of the earth. The independent owner and tiller of the soil is the bulwark of the nation, and it is this bulwark that we need in Canada. It is true that in all ages a country is chiefly known through her great cities; but there can never be really great cities unless there is a corresponding rural population.

END OF LAKE LOUISE, AND MOUNT ABERDEEN

THE MARITIME PROVINCES AND THE EARLY DISCOVERERS

The New World is not, like the Old, a network of historic highways; but, recently as its history of discovery dates, its shores and waters are not barren of heroic adventure, incident, and legendary charm.

Who has entered for the first time the noble Gulf of St Lawrence, and sailed inward up that vast river, with its wild and forbidding or elusive and mountainous shore-line, without feeling deeply the part it has played in the history of our race and the world?

Here came the first discoverers, from battle-worn, commerce-burdened Europe; seeking, by a sort of divine instinct, new dreams of human ideal and human effort in a virgin world. Or perchance, as some thought, they imagined they were reaching the farther shores of distant Ind or Cathay.

Whatever their dreams and knowledge, whatever their limitations, they were animated by a great spirit, alike of impulse and faith, which drew them past the superstitious fear and narrow conventions of their day to the truth and actuality which lay beyond. Those great spirits

“Feared no unknown, saw no horizon dark,

Counted no dangers; dreamed all seas their road

To possible futures; struck no craven sail

For sloth or indolent cowardice; steered their keels

O’er crests of heaving ocean, leagues of brine;

While Hope firm kept the tiller; Faith in dreams

Saw coasts of gleaming continents looming large,

Beyond the ultimate of the sea’s far rim.”

Whatever may have been their special human frailty, these early discoverers were of no mean stock, of no empty courage, but were of the best influence which animated their people and their time.

“Souls too great for sloth

And impotent ease, goaded by inward pain

Of some divine, great yearning restlessness;

Which would not sit at home on servile shores,

And take the good their fathers wrought in days

Long ancient timeward; reap what others sowed:

But nobler sought to win a world their own,

Where men might build the future: rear new realms

Of human effort, forgetful of the past,

And all its ill and failure: knowing only

Immortal possibility of man.”

Stripped of all its cruel, superstitious, greedy, and adventurous cloak, this was the inward spirit of early discovery at its best.

Each age is dominated by some great dream which seizes its best mind and energy. Philosophy, art, religion, science, literature, commerce, and war have each had their age. That of Columbus, Galileo, Raleigh and Gilbert, of Cabot and La Salle, was the age of human discovery.

It was not only an adventurous and restless period, but it was of a certainty a heroic one. Let those who doubt this, voyage out on the broad Atlantic, starting from Liverpool or Southampton, in one of the great ocean-liners of to-day—vast in the dock, but how incomparably small in contrast with the vastness of ocean!—and let them imagine the small, high-pooped sailing vessel which essayed this voyage for the first time, adventuring out into the unknown and far from kindly Atlantic; and they will realise the desperate undertaking of our first Canadian discoverers.

South of the noble gateway to the eastern interior of Canada, the famed St Lawrence, there lies a group of provinces of the Dominion, small in comparison with the western areas, but important as the first to be discovered, and by reason of their heroic history from that day to this. These provinces are Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the small island called Prince Edward. These were settled by the Scottish, Acadian French, and United Empire Loyalist stock; and while they are now a small proportion of the Dominion, yet they represent in their people the three dominant elements which have gone to make up the Canada of to-day.

This is a region of much sea-line, of bold, rugged shores, noble mountains, and vast sea-marshes. It is a region teeming with history and legend. Out of its confines came the beautiful story of Evangeline, the romance and tragedy of La Tour and De Monts, and the splendid failure of the Scotsman Alexander.

It has later been the theatre of the more practical, if less romantic, successes of the modern Scot and United Empire Loyalist; and is to-day most favourably known because of its mines, fisheries, harbours, its orchards, and the Canadian statesmen and thinkers which it has produced.

On a neck of land connecting New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and on the south side of this isthmus, are the famed marshes of Tantramar, one of the great sights of Canada, and a noted haunt for sportsmen. Here the Bay of Fundy, where the tides rise higher and fall lower than anywhere else in the world, washes for miles a vast marsh-land, which at low water is an immense gleaming beach, and at high water an inland sea.

ROAD NEAR THE BAY OF FUNDY, AUTUMN

It is, next to the shores of the great inland lakes, one of the most lonesome places in the whole world; and the very sea-wind, on a summer day, is full of a desolation quite Celtic in its suggestion. Here the soul may loiter at high tide, and listen, while far out and away from

“The roar of cities and the haste of men,

Tumultuous Fundy thunders through his haze

A grief more sad than woe of poet’s pen,

And wakes the sea-wolf in his craggy den,

And lifts his mists, and brims his tides afar,

To lave the shining wastes of haunted Tantramar.”

The north-east point of Nova Scotia is the island of Cape Breton, with its Bras d’Or Lake, an arm of the sea, its new Campbelton, Sydney, and the famed Louisburg.

Here, it is said, first came Eric the Red and his fellow-Norsemen, discovering Markland and perchance Vinland or Vineland; and here, perchance, also, the hero of Longfellow’s Skeleton in Armour may have first sighted land.

“Three weeks we westward bore,

And when the storm was o’er,

Cloud-like we saw the shore,

Stretching to leeward.”

Here it was that the great Cabot first came, as the discoverer of the American mainland, and touched at this eastward cape after weeks of drifting and tacking; and fear and doubt on the part of his followers. But genius is self-centred and self-sustaining. It leans only on Deity and its own indomitable spirit of resolution; and, like the fabled heroes of olden story, he was compelled to sail on, led by an impulse stronger than human fear and human doubt.

“Over the hazy distance,

Beyond the sunset’s rim,

For ever and for ever

Those voices called to him.

Westward! westward! westward!

The sea sang in his head,

At morn in the busy harbour,

At nightfall on his bed.

Westward! westward! westward!

Over the line of breakers,

Out of the distance dim,

For ever the foam-white fingers

Beckoning, beckoning him.”

It was the eternal call of the sea to the restless son of old Ocean; and here he came, after a long travail by storm and calm, and was the first man in history to land on these shores.

Here, after him, and later, came the Breton and Basque merchants and adventurers, De Monts and his associates, founding Port Royal and that Acadia so famed in song and story. Legend, however, has it that, centuries before this, Europe had knowledge of these coasts.

Here later adventured Sir William Alexander, a Scottish poet, who was granted by the British monarch a nobility greater than many a kingdom, and who founded a lesser peerage, extant to this day, and known as the baronetage of Nova Scotia. Thus Scotland had her part in, and gave her name to, this romantic and remote region.

The story of the discovery of Nova Scotia, or New Scotland, by the two Cabots is an interesting one. John Cabot, a Venetian merchant settled in England, by means of his adventurous spirit obtained favour with King Henry VII.; and, ambitious of doing for England what Columbus had done for Spain, Henry granted to him and to his sons a patent to sail under the flag of England on an adventure of discovery of new lands.

Cabot, his son Sebastian, and a crew of eighteen men sailed from Bristol and beat west for fifty days, sighting land on St John’s Day, the 24th of June 1497. This land was the northern shore of Cape Breton. Here Cabot erected a large cross with the standards of England and Venice, and called the land Prima Terra Vista. Cabot was thus the pioneer of English discovery and colonisation in Canada, and the first known founder of the Maritime Provinces.

Britain having shown the way, Portugal and France sent out discoverers, and the greatest of these was Cartier, who discovered the St Lawrence and claimed Canada for the French in 1534.

That gifted Celtic-Canadian statesman and poet, D’Arcy M‘Gee, has fittingly told in heroic verse of the departure of Cartier from St Malo:

“In the seaport of St Malo ’twas a smiling morn in May

When the Commodore Jacques Cartier to the westward sailed away.

In the crowded old cathedral all the town were on their knees,

For the safe return of kinsmen from the undiscovered seas

And every autumn blast that swept o’er pinnacle and pier

Filled manly hearts with sorrow and gentle hearts with fear.

. . . . . . .

But the earth is as the future; it hath its hidden side,

And the captain of St Malo was rejoicing in his pride.

In the forests of the north, while his townsmen mourned his loss,

He was rearing on Mount Royal the fleur-de-lis and cross.“

Then the spirited ballad describes his return, and his pictures of the wonders of the new world; as, for instance, when

“He told them of the river whose mighty current gave

Its freshness for a hundred leagues to ocean’s briny wave.”

While this great adventurer is chiefly famous as the discoverer of the St Lawrence and Quebec, he came at first to Acadia, and in 1541 fortified Cape Breton.

FALL OF THE YEAR, NOVA SCOTIA

The next explorer to arrive was Jean François de la Roque, seigneur de Roberval, appointed by the king of France to be lieutenant of Canada and the lands adjacent.

We next come to the period of Queen Elizabeth, and the hero, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a man of great physical stature and prowess, and noted as a scholar and a patriot. He set sail in 1583 with four vessels, carrying two hundred and fifty emigrants, the first emigration expedition from Britain to Canada. Arriving at Newfoundland, he took possession in the name of the virgin queen. But his emigrants proved a sad failure, by reason of their discontent and lawlessness; and it is said that the governor found it necessary to crop the ears of the unruly in order to maintain his authority. There is no doubt that, in all early colonies, the failure was owing to the desperate character of the colonists, who were for the most part restless malcontents who could not be satisfied at home or anywhere else, and who mistook licence for freedom.

Sir Humphrey, having raised a pillar carrying the royal arms of England, sailed in his ship, the Squirrel, a vessel of only ten tons burden—remarkably small in comparison with the Allan liner, the Virginian, of twelve thousand tons burden—and was swamped in a great storm.

The historical account says:—

“When the wind had abated and the vessels were near enough, the Admiral was seen, constantly seated in the stern, with a book in his hand. On the 9th of September he was heard by the people of the Hind to say: ‘We are as near heaven by sea as by land.’ In the following night the lights of the ship suddenly disappeared. Nothing more was seen or heard of the great Admiral.”

Longfellow has the following beautiful picture of his heroic death:—

“Eastward from Campobello

Sir Humphrey Gilbert sailed.

Three days or more, seaward he bore,

Then, alas, the land wind failed.

Alas, the land wind failed,

And ice-cold grew the night,

And never more on sea or shore

Should Sir Humphrey see the light.”

And so ended disastrously the first practical attempt at British colonisation of the new world.

Another picturesque attempt at the colonisation of Acadia was that of Sable Island. Henry IV. of France was a great patron of maritime adventure and enterprise, and he sent the Marquis de la Roche as lieutenant of Acadia, who took out a cargo of convicts and left them on that barren spot where nothing grew. Here they lingered in great misery for seven years, subsisting on seals and other fish, until only twelve remained to return to France, where they were pardoned by the king, who was astonished at their long beards and sealskin garments, and ordered them to be paid a gratuity of fifty crowns each.

Here in turn came Frank and Scot, each setting foot, and each in turn being ousted by his rival. The most famous theatre of this struggle for race dominance was the beautiful and now historical Annapolis Valley. Seen in fine weather, it is one of the fairest regions in all the world. It is now a country of mountain and valley dotted over with beautiful farms and famous orchards. Poutrincourt and his adventurers found it as pleasing in their day, when sailing along the south coast of Fundy, called by them La Baye François, they discovered what is now the Gut of Digby, and, steering in, found the splendid basin surrounded by hills and valleys, and streams of fresh water that ran down to the level wooded lands that rimmed the shore.

Here, in this newer Eden, he founded the famous Port Royal, amid its grassy meadows, its numerous streams, its cascades tumbling from the hills, and its forest-clad mountains.

But this beautiful spot was not long destined to remain French. Soon it was to be the stronghold of an organisation of Scottish baronets headed by the noted Sir William Alexander, who was created Earl of Stirling and Viscount Canada; and long after the place was called Annapolis in honour of Queen Anne.

It is not the province of this work to go into the details of history, but the present result of all this adventure and struggle is shown in a people largely Scottish and United Empire Loyalist, with a few settlements of the original Acadian French still remaining.

PORT HAWKESBURY, ON THE STRAIT OF CANSO, CAPE BRETON

The Nova Scotian is a Canadian, but he is also a type by himself, by reason of his parent stock, his experience, and his peculiar environment. The Acadian people are much as they were in the days of the tragedy of Evangeline. They are a simple, primitive folk of the old-time Breton type, living largely to themselves, and apart from the progress and strenuous effort around them.

The quaint and romantic village of Grand Pré is their most representative locality, and the one chiefly associated with their dispersion by Lawrence. The visitor to their villages and farm-lands will find very little difference in their character and manner of life from that depicted in Longfellow’s beautiful Evangeline.

“In the Acadian land on the shores of the basin of Minas,

Distant, secluded, still, the little village of Grand Pré

Lay in the fruitful valley. Vast meadows stretched to the eastward,

Giving the village its name, and pasture to flocks without number.

Dykes, that the hands of the farmer had raised with labour incessant,

Shut out the turbulent tides; but at stated seasons the floodgates

Opened, and welcomed the sea to wander at will o’er the meadows.”

“Away to the northward,

Blomidon rose, and the forests of old, and aloft on the mountains

Sea-fogs pitched their tents.”

Now, as then, will be found the conditions of this happy, contented, quaintly religious people, living apart in their own manner, away from the strenuous, restless, more masterful people about them.

It is not to be supposed that they have not changed somewhat, where change is eternal in all peoples.

The region first called Acadia, or, according to the Indians of Champlain’s time, “the place of plenty,” abounding in fish, moose, caribou, partridge, and many fur-bearing animals, and afterwards called Nova Scotia, was finally divided into three provinces. During the latter part of the eighteenth century, settlements of Scots from the old world located themselves on different parts of the coast.

These were followed by a great influx of loyalists who came from the south at the time of the American Revolution. The chief settlements were at Halifax and St John; but others were scattered throughout the country.

These new-comers, while they helped to save the country for Britain, brought with them just a touch of the Yankee atmosphere, which permeates the country to this day. Upper Canada, now Ontario, had a similar invasion; but the element from the old country was stronger than that in the Maritime Provinces, so that there is a difference in the characteristics of the two peoples. In Ontario, it cannot be said that the United Empire Loyalist dominated as he did in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

The result has been that the ruling class in the Maritime Provinces, when not Scotch, has been largely U.E. Loyalist; whereas in Ontario this element has not forced itself to the front to the same extent. Such names as Howe, Wilmot, Tupper, and Borden give a slight idea of the many U.E. Loyalist families which have produced men of prominence.

The Maritime Province men as a class are more akin to the New Englander in their characteristics. They are simpler in their lives than the people of the other provinces, and take an unusual part in the public life of the Dominion. They are intellectual and energetic quite to the extent of restlessness. They have all the strong qualities and weaknesses of maritime folk. They know more of the world than do inland people. But they are unsettled and ambitious, and the young men rarely stay at home. The result has been that some of the ablest Nova Scotians dwell in Boston and other American cities.

Maritime Canada has suffered much from this drain of her best blood, but some day the reaction will come and the tide turn the other way. Meanwhile this close intercourse with the land to the south has been not altogether for the good of our people in that part of Canada.

CAPE PORCUPINE, GUT OF CANSO, CAPE BRETON

THE MARITIME PROVINCES—LATER HISTORY AND CHARACTERISTICS

In spite, however, of this constant drain, the Maritime Provinces have produced some of the most distinguished Canadians. In public life to-day we have such able administrators as the Honourable W. S. Fielding, next to Sir Wilfred Laurier the most prominent man in the Canadian Cabinet; the Honourable R. L. Borden, the brilliant leader of the opposition; and the names of Sir Charles Tupper, Sir Leonard Tilley, the Honourable Andrew Blair, the Honourable George E. Foster, Dr Weldon, and a host of other men, prominent in public life, witness the political activities of these provinces. In other walks of life, Archbishop Connolly, the greatest ecclesiastic that English-speaking Catholic Canada has produced, and one of the great men of the early days of Maritime Canadian history; Principal Grant; and Bishop Medley (Anglican), of New Brunswick, stand first in the religious world; though Bishop Inglis (Anglican) and Archbishop O’Brien (Roman) were distinguished men.

In education, Grant and Dawson are prominent names in the Dominion.

Joseph Howe and Thomas Haliburton (“Sam Slick”) were Nova Scotia’s greatest sons. Howe and D’Arcy M‘Gee were the two greatest Canadian orators. Howe was a printer who wrote poetry and was inspired by an ardent desire to liberate his province from the trammels of bureaucracy, and after years of struggle he succeeded. He had the faults common to all great orators and public men who win much popularity; but he never became a mere demagogue. His oratory was irresistible. He could rise to the highest flights, and tell the drollest stories; and his magnetic personality, coupled with his high ideals, made him the idol of his people, though for many years he seemed to fight a losing battle. He was a strong Imperialist, as was Haliburton; but he stood out for a long time against the bringing of Nova Scotia into the federation. He was afraid that his province would be swamped in the union, and to a certain extent he was right.

But the union had to come; and in time Howe himself accepted office under Sir John A. MacDonald at Ottawa. But Howe never felt exactly right about it; and it is said that once MacDonald and Howe were walking together in the streets of Ottawa, down near the Chaudière, when the former exclaimed: “Well, Howe, I have got you here at last.”

“Yes,” answered Howe moodily, “but with the halter about my neck.”

Howe was not a great poet, but he had a fine literary instinct, and his influence in that direction was very strong. He was a delightful lecturer, and an address which he delivered on Shakespeare, at Halifax, on the occasion of the three hundredth anniversary of the great poet’s birth, was a brilliant and scholarly effort, and showed his unusual mind.

The other great Nova Scotian was Thomas Haliburton, who was of Scottish descent, and who became famous under the pen-name of “Sam Slick.” He has been acknowledged as the father of American humour, and was the first of that remarkable school whose ranks contain Artemus Ward and Mark Twain.

Haliburton was not merely a wit; like Howe, he was a far-seeing philosopher, and much that he predicted regarding Canada has come to pass. He foresaw, not only confederation, but also, as Howe did, Imperial federation, and was the first Canadian to win a seat in the British House of Commons.

His satire on the Yankee character of the day was inimitable, and made him noted on both sides of the Atlantic. Dickens never depicted a character more truly and successfully than Haliburton has the hypocritical cheat of his day, in the following terse dialogue:—

“Sam, have you watered the spirits?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Have you sanded the sugar?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then come up to prayers.”

He immortalised the Yankee horse-trader and general pedlar, who, no doubt, in ante-protection days, flooded Maritime Canada with his spurious wares, such as wooden nutmegs and paralytic clocks, and took away good Canadian horses in exchange. But Haliburton struck a specially hard blow at the religious hypocrisy and social vulgarity which were then rampant; and he possessed a human touch and a sense of humour that made his work not only popular, but a strong influence for good, in a way which has only been equalled by Lowell’s Bigelow Papers.

OLD-FASHIONED FARM, NEW BRUNSWICK

The leader in public affairs in New Brunswick who came nearest to Howe in character and ability was Lemuel Wilmot, who was as noted for his persuasive oratory as for his desire for constitutional government. It is to be wondered what such men as Howe and Wilmot would think were they to see the present condition in Canada, where the franchise, which they struggled so nobly to obtain, is bartered, trampled under, or ignored by the people, who seem to value little the gift presented to them by former generations.

There is no doubt that these able and conscientious patriots of the past would recognise, what men of sense and thought are beginning to realise, that the franchise has been given to too many; and that society is getting into the hands of a mob of reckless or conscienceless irresponsibles, who deal in votes as a purchasable commodity. What a contrast there is between the efforts of such great men as those were, and the people of the present, who ruthlessly waste and destroy what those noble Canadians won for us as a lasting heritage of freedom!

Howe and Haliburton were like their own coast and sea-line. They were large and noble; they were men of ideal and action; they towered like Blomidon; they lashed the coasts of human tyranny and helotism as Atlantic smites his rocky shores.

The tendency to-day in this country to live too much in and for the present, receives a constant rebuke in the verse and speeches of Joseph Howe. Many of this generation, who claim to have made Canada, and are inclined to cast a slur on the past, or to forget its deeds, need to imbibe somewhat of the spirit and principles of the following poem from the pen of this great Nova Scotian. It is entitled:—

OUR FATHERS

“Room for the dead! Your living hands may pile

Treasures of art the stately tents within,

Beauty may grace them with her richest smile,

And genius there spontaneous plaudits win:—

But yet amidst the tumult and the din

Of gathering thousands, let me audience crave!

Place claim I for the Dead—’twere mortal sin,

When banners o’er our country’s treasures wave,

Unmarked to leave the wealth safe garnered in the grave.

The fields may furnish forth their lowing kine,

The forest spoils in rich abundance lie,

The mellow fruitage of the clustered vine

Mingle with flowers of every varied dye;

Swart artisans their rival skill may try,

And while the rhetorician wins the ear,

The pencil’s graceful shadows charm the eye;

But yet, do not withhold the grateful tear

For those, and for their works, who are not here.

Not here? O yes! our hearts their presence feel,

Viewless, not voiceless; from the deepest shells

On memory’s shore harmonious echoes steal,

And names which in the days gone by were spells

Are blent with that soft music. If there dwells

The spirit here our country’s fame to spread,

While every breast with joy and triumph swells,

And earth reverberates to our measured tread,

Banner and wreath will own our reverence for the Dead.

Look up: their walls enclose us. Look around:

Who won the verdant meadows from the sea?

Whose sturdy hands the noble highways wound

Through forest dense, o’er mountain, moor, and lea?

Who spanned the streams? tell me whose work they be,

The busy marts where commerce ebbs and flows?

Who quelled the savage? and who spared the tree

That pleasant shelter o’er the pathway throws?

Who made the land they loved to blossom as the rose?

Who, in frail barques, the ocean surge defied,

And trained the race that live upon the wave?

What shore so distant where they have not died?

In every sea they found a watery grave.

Honour for ever to the true and brave,

Who seaward led their sons with spirits high,

Bearing the red-cross flag their fathers gave;

Long as the billows flout the arching sky,

They’ll seaward bear it still—to venture or to die.

The Roman gathered in a stately urn

The dust he honoured—while the sacred fire,

Nourished by vestal hands, was made to burn

From age to age. If fitly you’d aspire,

Honour the Dead; and let the sounding lyre

Recount their virtues in your festal hour;

Gather their ashes—higher still, and higher,

Nourish the patriot flame that history dowers,

And, o’er the old men’s graves, go strew your choicest flowers.”

Canada may be noted in the present for her vast natural scenery and her store of natural products; she may be famed in the future for prosperity, intellectual and material; but she will never produce a gem of humanity or nature more precious than the memory of this great Canadian. The times have changed. We are producing a more concentrated if less inspired quality of verse, and a keener and more expert class of men. But in both our literature and our personality we miss that large humanity, that love of truth and genuine liberty, which inspired our patriots and our poetry of the past.

We have been told that life is growing broader in its outlook and sympathies. But in truth it is becoming narrower and harder; and we are in great danger of being ground down by a tyranny of materialism and greed, which has absorbed our lives. Men seem of late to have lost much of that old spirit of independence and love of righteousness which once dominated our literature and life, and made such men as Howe, Haliburton, and M‘Gee possible. To-day we are told that business methods have superseded the old-time rhetoric, and that the cool head has taken the place of the warm heart. But what has been the result of this reign of business and keen financial enterprise? We read it in every election-trial, and we see it in the general deterioration of the life about us.

BASIN OF MINAS, NOVA SCOTIA

What Canada needs to-day is a return to the conditions which produced such men, who brought high ideals, humanity, and culture into the everyday political life, and appealed to the highest sense of the people rather than to the lowest and meanest.

In this description of Nova Scotia I do not want to appear to lay too much stress, without reason, upon one man. But as Scotland had her Burns, so Nova Scotia had her Howe; and it might be answered of the latter in his own language applied to Burns, in reply to his question why the Scottish poet’s memory had been so universally honoured:—

“It was because, long after he was dead and his faults and follies were forgotten, it was discovered that in this man’s soul there had been genuine inspiration—that he was a patriot, an artist—that by his genius and independent spirit he had given dignity to the pursuits by which the mass of mankind live, and quickened our love of nature by exquisite delineation. It was found that hypocrisy stood rebuked in presence of his broad humour.”

But Howe’s genius lay not alone in his oratory, culture, and humanity. He was a prophetic man, who saw beyond his time, and foresaw not only Imperial federation, but the ultimate union of the British race. This man, the very finest essence of the Nova Scotian, the pride and glory of the province by the sea, was no mere narrow Canadian, no separatist. On the other hand, he saw clearly the ultimate destiny of the Empire and the race. While he loved his native province, no one was a more patriotic Briton than he, who loved and honoured her history, her achievements, and who closed his fine address on Shakespeare with the following picture of Britain’s accomplishment and British conditions:—

“If it be permitted to the Bard of Avon to look down upon the earth this day, he will see his ‘sea-walled garden’ not only secure from intrusion, but every foot of it embellished with all that wealth can accumulate or art display. But he will see more—he will see her ‘happy breed of men’ covering the seas and planting the universe; rearing free communities in every quarter of the globe; creating a literature that every year enriches; and moulding her institutions to the easy government of countless millions, by the light of large experience. He will see more. He will see the three kingdoms, hostile or disjointed at his death, united by mutual interests, and forming together a great centre of power and dominion, bound in mutual harmony and dependence by networks of iron roads and telegraphic communication, and by lines of floating palaces connecting them with every part of the world.”

Nova Scotia proper is connected with the body of North America by a narrow isthmus, and contains nearly ten million acres of land. The surface of the country is undulating in hills, small mountain ranges, and agreeable valleys. Its sea-coast is inhospitable, and presents a bold, rocky shore and a sterile soil covered with birch and fir trees. The most noted cliff is Aspotagoes, a promontory near St Margaret’s Bay. It is a vast bastion over five hundred feet high, and is the first land discerned, approaching Halifax from Europe. Cape Blomidon, which juts on the Bay of Fundy, rises a dark red basaltic rock, and is an imposing and majestic sight.

In Nova Scotia, as in other parts of Canada, the autumn foliage is very brilliant when the leaves change under the quick action of the frost. Much of the province, however, is bleak and barren, owing to the vast amount of rock and the immense sea-coast line exposed to the fierce bitterness of the northern Atlantic.

The city of Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, was founded by the Honourable Edward Cornwallis, who sailed from Britain, and arrived on the 21st of June 1749 with 2576 emigrants. He had thirteen transports, guarded by one warship, the Sphinx. Up the harbour they went, with flags flying and sails unfurled—a wonder to the simple aborigines, who floated about them at a safe distance in their bark canoes.

It was the colony of Massachusetts, then belonging to Britain, which had interested herself in this northern peninsula. A scheme for colonisation was adopted, and the king’s commission was granted to Lord Halifax, Minister of Trade and Plantations, who took a personal interest in the work. The war with France had just closed, and the disbanded soldiers were selected as colonists, while Parliament voted forty thousand pounds. Five thousand emigrants were housed about the harbour during the first winter, and during that year St Paul’s Church and St Matthew’s meeting-house were erected. Fort George is on Citadel Hill, an eminence 256 feet above sea-level, and commands a superb view of the city, harbour, sea, and surrounding country.

YORK REDOUBT, AND HALIFAX HARBOUR

The approach to Halifax by sea is very fine. Here is one of the finest harbours in the world. It is said that a thousand vessels may float there in safety. It is six miles long, and accessible at all times of the year.

Halifax is a fine maritime city, and was long the chief British citadel on the Atlantic, and also a naval station. The ships are now withdrawn, and the fort is manned by Canadian troops.

It is also the terminus of the intercolonial railway, and the winter seaport for Canadian Atlantic steamers. It is also famous for its fish market, which has, it is said, a more varied supply of fresh- and salt-water fish all the year round than any other market in America. Here also fleets are fitted out for the Labrador and Island fishing-banks, so well depicted by Kipling and the Canadian writer Norman Duncan.

Near here, at the head of the harbour, the late Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria, resided, when stationed in British North America. The quaint lodge where he lived, with the grounds about it, are still pointed out as an object of local interest.

From here one can go north-east to Antigonish on the gulf, and from thence, across the narrow strait, to the island of Cape Breton, where the Sydney iron-mines are as likely to make it famous in the future as the ancient fort of Louisburg made it noted in the past.

Going directly west from Antigonish, Stellarton, New Glasgow, and Pictou, in Pictou County, are reached. The two former are noted mining centres, and the latter, Pictou, is famous as being one of the principal Scottish settlements in this province. Here were born and reared many noted Scotch Canadians, prominent among them being that remarkable and distinguished man, Principal Grant, late head of Queen’s University, Kingston, and the man of all men most fitted to have written the biography of Joseph Howe.

Northward and westward from Pictou, the Northumberland Straits separate the mainland from the small island province, Prince Edward Island. This province is smaller in area than Cape Breton Island, and contains only three counties, Princes, Queens, and Kings. It has for its size an immense shore-line; and Charlottetown, its capital, is a quaint old town. Agriculture and fishing are its chief industries, the latter being the best in the Gulf of St Lawrence, the province being especially famous for its oysters.

Returning to Halifax, one can go by rail north to Truro, Amherst, and Moncton; and thence to Quebec province or to St John, New Brunswick.

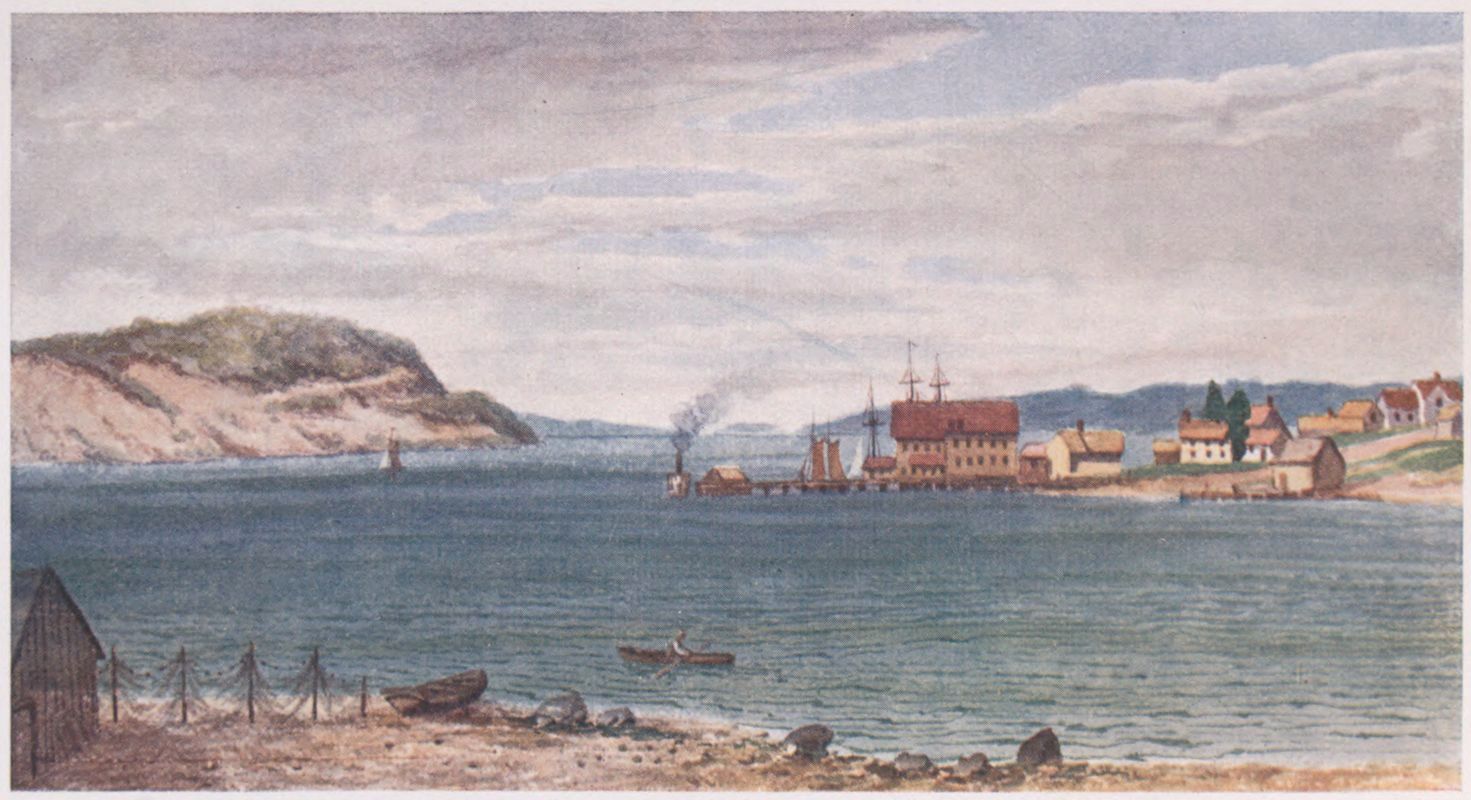

Here, at the mouth of one of the Canadian rivers, St John, the prominent seaport, like Halifax, is situated on a hill overlooking the sea, but, unlike it, is a mercantile port alone. The city faces on the great Bay of Fundy, and is the second leading maritime port for ocean steamers.

Here a fort was built by the La Tours, and here Charles La Tour ruled feudally in the wilderness, and held the trade of New Brunswick and Maine in the hollow of his hand. It was here that, in bastioned security, he defied Charnissay and the French government; and it was here that his heroic wife later made the brave but futile stand, which ended in her death a short time afterwards.

The city of St John was founded by the loyalists who left New England and landed here in 1783. The same year New Brunswick was created into a separate province. This city was formerly a great shipbuilding port, and was several times destroyed by fire.

The valley of the St John was once a great lumber centre, and is now one of the most beautiful farming regions in America. Going by boat or by railway along its western bank, Fredericton, the capital, a flourishing city in a fine agricultural country, is reached. The mouth of the St Croix, which forms the boundary between New Brunswick and the United States, is also a beautiful region. Here are the harbour and town of St Andrews, a delightful summer resort; and by boat can be reached the picturesque and desolate island of Grand Manan, out in the Bay of Fundy.

The people of this district are largely influenced by their cousins over the border; but some of the most strenuous and active men in Canadian public life have come from this province, among them being two prominent finance ministers and other important ministers of the Dominion Cabinet.

STORMY SUNSET, COAST NEAR ST JOHN, NEW BRUNSWICK

Before leaving the Maritime Provinces, it might be suggested that it would be for the benefit not only of the Dominion, but of the Maritime Provinces themselves, if the three provinces were united in one. The vast growth of the west, with its great provinces, and the recent addition to Quebec and Ontario, will make the union of the three eastern provinces a virtual necessity in the near future.

It may not be realised abroad, but it is recognised in this country that a great deal of our political corruption has arisen in the first place in the local legislatures. We are

“A people for high dreamings meant,

But damned by too much government.”

The world is beginning to see that what is called home rule has its drawbacks as well as its good qualities, and that local government has been somewhat overdone on this continent. It has been to a great extent the curse of the United States in the past, and the American Federal Government has just struck its first blow at this overdoing of the local evil, when it points out that California must be amenable to a treaty made at Washington with Japan. The Canadian Government has made a similar move in retaining the control of the lands in the new provinces. Localism has had too much of its own way during the nineteenth century, and has been literally done to the death. It was popular so long as it meant defiance of Downing Street. But now, when it applies to Washington or Ottawa, it is seen to be scarcely so virtuous and admirable an attitude.

The people in the British Islands should take a lesson from us in this matter, and be careful ere they go too far in this direction in granting home rule to Ireland, Scotland, and England. If the matter is studied, apart from mere passion and prejudice, it will be found that petty local governments can prove very often more a curse than a blessing to the localities where they are established.

There is such a thing as having too many governments, which mean often merely so many organised local jealousies, animosities, and self-advantages at the expense of the whole country. And when, in a large territory like Canada or the United States, a small province or state demands all of the rights and privileges that are accorded to a neighbouring community ten times its size in area and population, it is only a vicious system of party government, accustomed to grant all sorts of absurd demands for the sake of power, that does not see the ridiculous situation at once.

The day will come when common sense will prevail, when the United States will reconstruct her people into several large provinces, and do away with the monstrous absurdity of so many petty states and petty legislatures, which are a continual bar to progress, and a feeding-ground for corrupt parish politics. Long since have the most of these states ceased to count for anything save in name. In the great questions of the nation, even in the election of a president, a few prominent cities and states control the Union; and it is a long time since anything smaller than the solid north, the solid south, or the solid west has been heard from.

This is rapidly becoming true also of Canada, and if such a man as Joseph Howe were alive to-day in the Maritime Provinces, he would agitate just such a union as has been suggested. The day has gone by when a small people or a minority community can hold up the vast majority and demand privileges merely because they are ancient in their foundation. The day of little governments has departed, and with the rapid growth and expansion of the west, the present conditions in the east will not long be tolerated.

The Maritime Provinces have done much for Canada, but the road of progress and population seems to be ever westward; and, in this sense, our eastern provinces are already more of the past than the present. What they need is a re-adjustment of their government on practical lines, so as to bring the control and development of their country more up to date. They have great physical resources, mines, fisheries, farm-lands, and harbours, as yet untouched and undeveloped. They have millions of acres that will yet be tilled; and the day will come, when the wave of westward emigration has begun to ebb, when the lands of these provinces will be more appreciated.

Meanwhile, one strong government, with a good immigration and development policy, would do much to bring, what they are sorely in need of, a greater population, to fill those beautiful valleys and shore-lands, which are the historical and picturesque gateway to the vaster Britain of the west.

QUEBEC AND THE LOWER ST LAWRENCE VALLEY

The eastern gateway to Canada is the vast waterway of the St Lawrence. Here came Cartier and Champlain, and that longtime of noble discoverers, adventurers, and ecclesiastics; founding historic Quebec and the famed Mount Royal, which now gives one of his titles to one of the greatest Scotchmen and Canadians of the nineteenth century.

Parkman, the great American historian, has immortalised the history of this famous stream, and has made the early French explorers stand out among the most interesting and heroic figures in all history.

When one reads Parkman, Canada ceases to be a mere northern, desolate region of iron-bound, inhospitable coasts, trackless forests, and lonely lakes and rivers. It becomes at once a romantic and enchanted land, the theatre of incidents and events both heroic and historic, and as beautiful and sublime in its vast background as the glamour which heroism, religion, the charm of race, and love of adventure can throw over the characters and communities which made it their stage of action and ideal.

It is remarkable, and a strong rebuke to those narrow theoretical nationalists who make national patriotism a profession, that the truest and most noted writers who have dealt with our history and legend have been outsiders, and not of our country at all. Genius cannot be limited; imagination knows no boundaries. It is the petty professional writer who boasts that all his subjects for literary purposes shall be limited to his own country. We have in Canada, and have had in the past, a very few such writers and cliques, exploiters of our new nationalism for the advantages which it may bring them. But the best answer to all such is the fact that the three leading American historians are famous because of their interest in outside countries and nationalities. Motley has given to the world his Dutch Republic, Prescott his noted History of Mexico, and Parkman is famous for his beautiful studies of French Canada.

The two most famous Canadian poems, Evangeline and Hiawatha, were written by Longfellow, the American poet. The scene of Hawthorne’s finest novel, The Marble Faun, is laid in Italy. Washington Irving’s Bracebridge Hall deals with rural England. Whittier’s most popular ballad is The Siege of Lucknow. Some of Emerson’s most noted poems deal with mediæval history and the East. On the other hand, the finest American novel is The Virginians, by Thackeray. Charles Reade’s greatest novel, The Cloister and the Hearth, deals with Germany of the days of Erasmus.

This all shows that there can be no limit to genius. No class of men can dictate to the writer as to the choice of his subject. But it will be found that most of our writers have had a special interest in the rich civilisations of the past, as more attractive than the crude, material present. Because of this, French Canada, with its romantic atmosphere, has been the chief theatre for our Canadian literature.

In reality, the history of French Canada is more alien from the Ontario writer, whose parents or grandparents have come from England, Ireland, or Scotland, than is the history of those homes of his ancestors; and it is an affectation to say that it should not be so. The truth is that the greater portion of the people of Canada, up to the present, have known little of each other; and where people have been living, as in Lower and Upper Canada, separated by race, religion, and language, it is absurd to expect that they should have anything in common. It is quite natural that the settler in Canada from Scotland should know much of Scottish history and literature, and nothing whatever of the history of French Canada.

In fact, had it not been for an American, Parkman, and the common school history, the people of Ontario would know practically nothing of early French Canadian history. And much as we may admire the deeds performed, and the characters who walked the stage, it is all as foreign history to us, in so far as we are concerned, as is the history of Peru or the Dutch Republic.

As well ask the inhabitants of Kent to call the early history of Ireland or Scotland theirs, as ask the Ontario man or the Manitoban to become enthusiastic over the early French régime. It would be as absurd as to ask the French Canadian to regard as his own the United Loyalist history, or that of the settlement of St John by the British.

It should be realised by the outsider that Canada is a vast country, including the larger northern part of one of the greatest continents on the globe; that its territory stretches from ocean to ocean; and that it is now but the result of the union of several scattered colonies with a common history dating only since about forty years back. In this way, only, will it be realised that the amalgamation of the Canada of the future is as difficult a matter as was the union of the British peoples in the remote past. Even to-day the French Canadian calls his fellow English Canadians English, and regards himself as the only Canadian; and in some parts of the Maritime Provinces I have heard people talk of going up to Canada.

It may be acknowledged that the union of the Canadas in the ’sixties, like the union of the American States and the separation from Britain, was no simply unanimous and spontaneous matter. There was much opposition and bickering; and in some of the provinces for years there existed a class who never recognised the Federation. In a town in New Brunswick I saw a strange sight—the chimneys of a man’s house were painted black; and I was told that he had done this on the day of Confederation, it being his peculiar way of going into mourning for provincial independence; and he would never until the day of his death acknowledge himself as a Canadian.

When we realise that for more than half of the nineteenth century the whole of Canada meant merely Quebec and the province of Ontario, it cannot be wondered at that the French Canadian, who is separated in language, law, religion, and social habits, and who was the first inhabitant, should yet regard himself as the original and only Canadian.

No person coming to Canada should fail to come by the St Lawrence route. Not only is the scenery of the gulf and river beautiful, but the sight of the French villages on the river banks, with their large churches quaintly topped with tin spires, and their small whitewashed houses, is one not soon forgotten.

The habitant of the present day in the rural districts is much the same as he was a century since. He is happy and contented by nature, and not fond of change or very desirous of progress. Faithful to his church, his language, and his traditions, he tills his land much as his forefathers did, indifferent to modern improvements and the American vortex about him.

But, in spite of this conservative trend of mind in the mass of her people, French Canada has produced a group of statesmen, ecclesiastics, and litterateurs of which any country might be proud. From the very first she has had picturesque figures in her history; and the French Canadian should have good reason to be proud of his province in this respect. In the early days such names as Cartier, Champlain, La Salle, Brebeuf, and Frontenac were famous in history. Since British rule, Lafontaine, Cartier, Papineau, Chapleau, and Laurier stand out, especially the first two and the last, as rivals of any political leaders on either continent. But it is interesting to note that the spirit which has animated these leaders has led them away from the contentment and conservativism already mentioned, and in the direction of British and American institutions and ideals.

ST LAWRENCE, NEAR SILLERY COVE

There is, however, a quality in French Canada which marks her out from the rest of America. It is associated somewhat with her heroic history, with the sad and ideal, if mistaken, spirit of her early clergy. She is no doubt, in many senses, the most poetic people on this continent, and she has managed, in spite of all her weaknesses—and she has had many,—to ennoble and place a glamour upon the land she has occupied as has none other of the American peoples. That French Canada owes much to Parkman is true; but there is a charm, a quaintness, an artistic quality, a real love of life and its happiness, among her people, which seems sadly wanting elsewhere upon this continent.

In visiting Quebec province one notices a thing that is remarkable, and it is the flag flown everywhere, the tricolour of modern France. This seems strange and inconsistent, as of course the official flag is the British, and the old flag under which the French came to Canada was the royal flag of the golden lilies. Added to this that the modern French republic has ever been, and now is, antagonistic to the Roman Church, which is all-powerful and the State Church of Quebec; it is the more surprising that the tricolour should be the favourite flag of the people.

There have been several explanations of this replacement of the old flag by the tricolour. One is that the English brought it into Quebec after the Crimean War, as a tribute to the fact that France and England had fought side by side against Russia. But the true reason is that the strongest influence in Quebec is Nationalism, as is evinced by the jealousy of the people regarding their language. This is a very natural feeling, and it is an evidence that the race-idea is the most lasting one; and those who foolishly hope to destroy all race-ideals will find the spirit of the French Canadian one not to be crushed in that manner. The Quebec people are quite willing that all in Canada should be Canadian in their own way. They may smash their own or anyone else’s race-traditions; but they must not interfere with the Quebec man’s peculiar Canadianism. In other words, they may graft the new Canadianism on the old French Canadian stock; but the old trunk—that is, his ideals and his race-traditions, his loyalty to all that is French—must be left alone. Now, one cannot but admire this attitude on the part of the French Canadian; but it should also teach that the British Canadian on his part has sacred race-traditions, which must not be effaced, and which will be necessary to the highest development of the future Canadian people.

Entering the Gulf of St Lawrence, we reach Anticosti, an island with an interesting history, and now owned by Menier, the French chocolate-king. Passing the south shore, a series of gloomy mountain-ranges, with fishing villages nestled here and there amid sparse farm-lands in bays on the shore-line, we reach Rimouski on the south shore, the place where the European mails are landed. Farther up, as the river narrows, Green Isle or Isle Verte is reached; and opposite, on the north shore, is Tadousac, and the mouth of the great river Saguenay, the waterway to what is called the Lake St John district.

The Saguenay is one of the most remarkable streams on this continent. It is gloomy, forbidding, and lonely in its character; the shores often rise in high crags; and Cape Eternity, whose sheer cliff rises hundreds of feet from the river’s edge, is one of the most majestic and famous rocks in America. The following sonnet gives a description of its gloomy grandeur:—

CAPE ETERNITY

“About thy head, where dawning wakes and dies,

Sublimity, betwixt thine awful rifts,

’Mid mists and gloom and shattered lights, uplifts,

Hiding in height the measure of the skies.

Here pallid Awe for ever lifts her eyes,

Through veiling haze, across thy rugged clefts,

Where, far and faint, the sombre sunlight sifts,

’Mid loneliness and gloom and dread surmise.

Here nature to this ancient silence froze,

When from the deeps thy mighty shoulders rose,

And hid the sun and moon and starry light;

Where based in shadow of thy sunless floods,

And iron bastions vast, for ever broods

Winter, eternal stillness, death and night.”

The Saguenay river has always been held by the inhabitants of the province in a good deal of awe, and, as a stream, it has been associated with a mysterious and sombre fate.

It was up this stream, says legend, that the morose and unhappy Roberval disappeared into its desolate vasts. The tradition adds that, suspecting great mineral wealth in the interior, he sailed up its gloomy waters and vanished completely from the knowledge of men.

Another legend is associated with Tadousac, which is situated at the mouth of the Saguenay. It is the marvellous story of the Père Brosse, and is told in Lemoyne’s Chronicle of the St Lawrence, Père Brosse was the priest stationed at this place, and the story concerns his death, which was accompanied, so the legend states, by several miraculous happenings. The good father, having knowledge of his approaching death, bade his people go for the neighbouring curé, Père Compain, who was on the island of Aux Coudis, and bring him to perform the funeral offices. He prophesied that there would be a storm, but they were not to heed this, for he guaranteed them protection, and that they would find Compain awaiting them. All happened as he had prophesied, and, on their return, the Père Brosse was found at midnight in his church, dead, leaning against the altar; and it is added that the church-bells were tolled without men’s hands on the occasion of his death.