* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Rochester

Date of first publication: 1935

Author: Charles Williams (1886-1945)

Date first posted: Apr. 15, 2017

Date last updated: Apr. 15, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170436

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

|

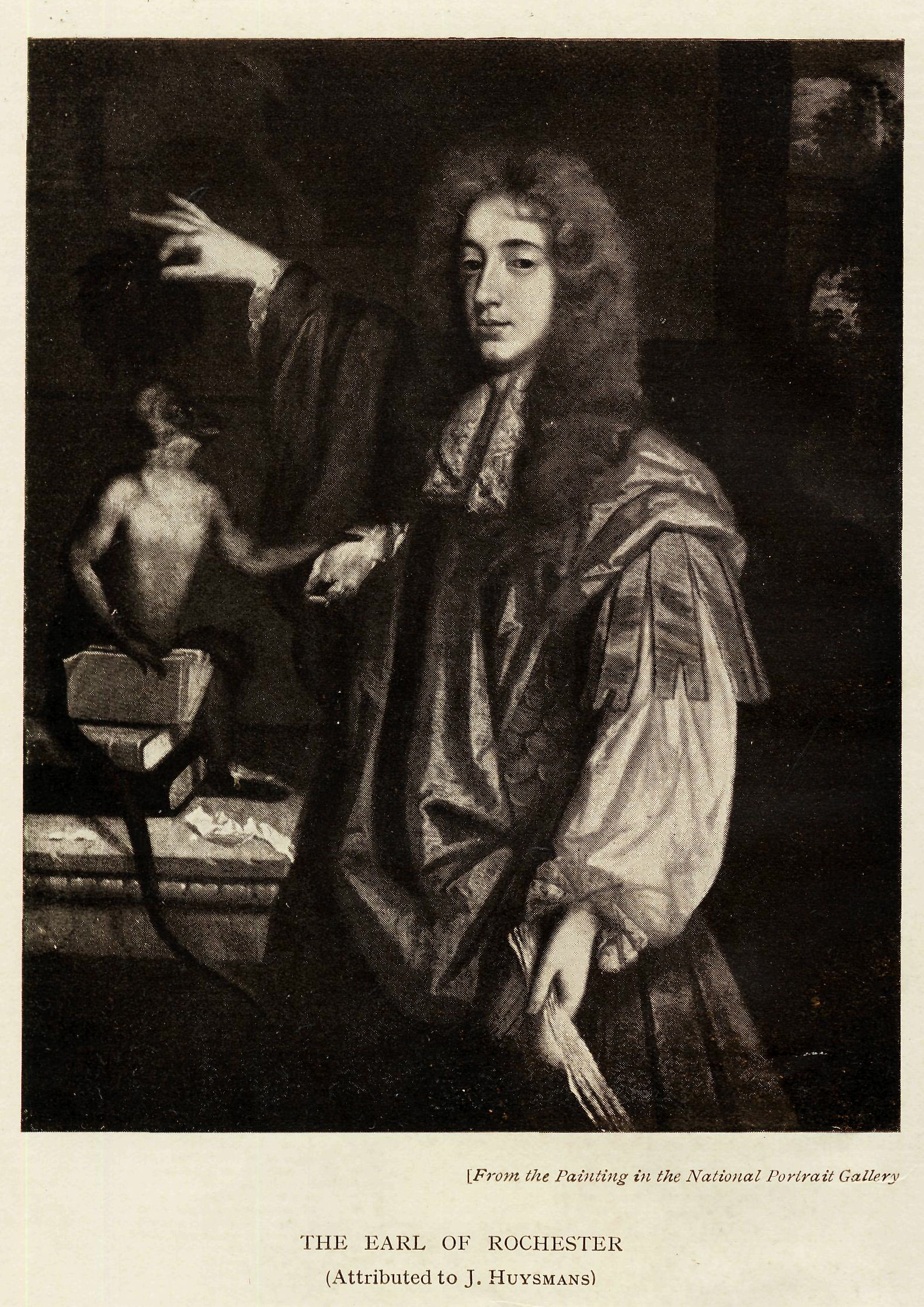

From the Painting in the National Portrait Gallery

THE EARL OF ROCHESTER

(Attributed to J. Huysmans)]

BY

LONDON

ARTHUR BARKER LTD.

21 GARRICK STREET, COVENT GARDEN

First Published 1935

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

MORRISON AND GIBB LTD., LONDON AND EDINBURGH

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I The Romantic Forest

CHAPTER II The Education of a Romantic

CHAPTER III The Engagement with Death

CHAPTER IV The Duel with Miss Hobart

CHAPTER V The Duel with Lord Mulgrave

CHAPTER VI The Actor and the Theatre

CHAPTER VII Interludes in the Country

CHAPTER VIII The Way of Sensation

CHAPTER IX The Way of Argument

CHAPTER X The Way of Conversion

CHAPTER XI The Way of Union

INDEX Index

There are three books on John Wilmot to which any student must be indebted—Mr. John Hayward's edition of the Poems (1926), Mr. Bonamy Dobree's Rochester (No. II. in the Second Series of Hogarth Essays, 1926), and the two volumes of researches by Herr Prinz (John Wilmot and Rochesterians). To these Professor V. de Sola Pinto has added a critical study in his recent book, Rochester; he has been good enough to discuss Rochester with me and to make of our separate tasks a pleasant companionship. Mr. Hayward has shown me many kindnesses; it is indeed a fortunate chance that has enlarged for me through this book the thing that Rochester and Burnet named as life's chief happiness—friendship. Mr. Francis Needham, by permission of the Duke of Portland, allowed me to see the manuscripts of poems by Rochester and Lady Rochester, which are shortly to be published.

It was night when at last the Penderel brothers brought a ladder and the King of England came down from his tree. One of his few friends, a certain Colonel Careless, had been hidden with him all day in the branches; another, the Lord Wilmot, lay at a house some miles off. The remainder of the army, which three days before had been utterly defeated at Worcester, was either prisoner to Cromwell or fugitive through the countryside. Priests' holes were occupied in manor-houses; forgotten paths through the woods were retrodden. The Parliamentary horse searched roads and woods; about all the villages went rumours of the whereabouts of captain and colonel, and of the dark, tall, humorous creature of twenty-one, who stood now at the bottom of the ladder among his peasant saviours, the proclaimed public enemy, Charles Stuart.

The tree and the darkness, the descent and the subsequent flight, are the picturesque properties of a romantic tale. The scattered figures, escaping through the western counties, are the climax of defeat. They disappear along the roads, into London, into scattered manors, into small ships in remote harbours, and every way into obscurity. It is nine years before they, or their sons and inheritors, return. As again they approach, from foreign places, from statelier ships, from restored manors, a gaudier light abolishes the dim landscape of the forest of the flight. The palaces of Whitehall and St. James expand to receive them. Time and the world have changed.

The wood in which, on the evening of that Saturday, September 1651, Charles II. stood, was symbolical of another forest—a thing of the spirit. The King's was not the only English tree which had contained at times a mortal inhabitant. Four years before Worcester, in another part of the country, another young man of twenty-one, named George Fox, also took refuge in woods. He wrote of his own flight: "My troubles continued…. I fasted much and walked abroad in solitary places many days, and often took my Bible, and went and sate in hollow trees and lonesome places till night came on; and frequently, in the night, walked mournfully about by myself: For I was a man of sorrows in the times of the first workings of the Lord in me."

He also was pursued; unlike the King, he did not escape his pursuer. A spirit captured his spirit; for him also the world changed. "Now was I come up in spirit, through the flaming sword, into the paradise of God. All things were new, and all the creation gave another smell unto me than before, beyond what words could utter."

The King escaped from his wood to temporal poverty, first in France, and afterwards in Whitehall; George Fox to spiritual richness in the paradise of God. The one emerged into a state of dubious and difficult royalty, within as without; the other, without as within, found a state of being of utter significance, of wholly desirable passion, and what he called "the hidden unity." The two exits were at opposite ends of that dark spiritual forest, in the maze of which were other wanderers, three of whom should be named.

One is of interest only as an historical coincidence. George Fox, interpreting his paradise into terms of mortal action, came to Derby, and there interrupted with vigorous theological protests a religious address by one of the military leaders of the Army of the Parliament. He was brought before the magistrates; there was high controversy. The magistrates, Fox thought, were still roaming in the old entanglements of human language, opinion, and desire. They asked him if he were "sanctified." "I answered: 'Sanctified! yes,' for I was in the paradise of God. Then they asked me if I had no sin. I answered, 'Sin! Christ, my Saviour, has taken away my sin, and in Him there is no sin.' They asked how we knew that Christ did abide in us. I said, 'By His Spirit, that He has given us.' They temptingly asked if any of us were Christ. I answered, 'Nay, we are nothing, Christ is all.'" After which "for the avowed uttering and broaching of divers blasphemous opinions contrary to a late Act of Parliament," he was committed to prison, where he remained for a year.

In 1651 there came to Derby, marching on the way to Worcester, other regiments of the army; with them a certain soldier from Nottingham, by name Rice Jones. By accident he came into propinquity, and into argument, with the imprisoned Fox. It grieved Fox to discover that Rice Jones was a Gnostic; he altogether denied the objectivity of Christ's sufferings—there were never any such things happened; the history of the Passion was a mystical tale, to be understood mystically. Fox called these interpretations "imaginations and whimsies." The unmoved Rice Jones marched on to Worcester with his company; it is pleasant to think that he, intensely concerned with his subjective transmutation, was one of those who rode under the tree where Charles Stuart, intensely aware of his own objective inconvenience, hid.

Rice Jones belonged to one of the wilder and more ancient tribes of the romantic spiritual forest. A fortnight after he had fought in the battle of Worcester, on Thursday, 18th September, while the King was resting in comparative comfort under the roof of a friend, a small boy, the son of an Edinburgh lawyer, kept his eighth birthday. His name was Gilbert Burnet; under the care of his father, a grave and slightly harsh practitioner of religion, he was already well advanced in the Latin tongue and the knowledge of classical authors. As he grew older, he read law and studied divinity. His divine studies led him, not to the obscure copses of Rice Jones's thought, or to the clear fields, beyond the forest, of Fox, or to the cleared spaces, on the hither side, of the scepticism of the King, but to one of the two great roads that then ran through the forest, the road of Anglican doctrine and the road of Roman doctrine. He became orthodox; he even became a bishop. More astonishingly, and less excusably, he came to believe that Christianity was rational. He had gone into the wilder retreats of the mystics, but had returned.

"The Misticks," he wrote, after reading St. Teresa and other such explorers, "being writ by recluse, melancholy people, … are full of rank enthusiasm."

He was a little surprised to find that his own close study of the Scriptures and religious discipline of life did not lead him with them into "all the extravagancies of Enthusiasme." He attributed his salvation from this danger to his having nothing of the spleen of melancholy in his constitution and to his philosophical studies. Philosophy taught him a certain disdain; it taught him to distinguish (he said) "between a heat in the animal spirits which was mechanicall, and that which lay in the superior powers of the soul."

In allusion to St. Teresa and George Fox, such a distinction is irrelevant enough. There are, however, less efficient travellers in the mystical depths than those two, and at least one of them was tamed by Gilbert Burnet's orthodox intelligence. Lady Henrietta Lindsay, daughter of the Countess of Balcarres, at the age of eighteen, fell into "histericall fits," in which she seemed to converse with God and the angels, and spoke, while the fit lasted, without interruption. It has been remarked that wiser visionaries allow God and the angels a greater share in the conversation than did the Lady Henrietta. One fit lasted ten hours; to the angels time is not so noticeable as to us. Burnet was called in; he advised her mother to send for a physician, and the fits ceased.

Yet Burnet was not without a longing for that stranger way. He practised asceticism; at one time he undervalued those who did not. He thought of abandoning the world, and of going unknown into a remote place to live and die, there to teach the poor. He desired mightily an "internal apprehension of extraordinary impulses," but he never found it. He had, in fact, a great number of romantic emotions, but philosophy and time subdued them. There remained in him only that enthusiasm which is the inevitable accompaniment of Christianity, the irrational creed warring with the scepticism which is at bottom all that philosophy can offer. At that time Descartes was writing in France, cogito, ergo sum, and begging the question with every word.

Another than Descartes had, in that same year 1651—the year of the King's escape, of Fox's release, of Gilbert Burnet's eighth birthday—in one great sentence, set an axe to the trunk of every tree in the wide romantic forest and, as it were, at the same time barred the high roads that ran through it. The young King, when he had been Prince of Wales, had had a mathematical tutor, by name Thomas Hobbes. In 1651 Thomas Hobbes published Leviathan. On the fifth page of that lucid work was the sentence which helped, both for good and evil, to set an age free from romantic vision and romantic entanglement. The sentence was: "Imagination is nothing but decaying sense." A little pallidly perhaps, and not with the full perfection of George Fox's day, its clarity breaks through the dark night of the soul. It freed those who walked in its light from much trouble; it even justified them in not taking trouble. Hobbes removed vision and the intellect of vision, and for it he substituted the senses and the intelligence of the senses; it is why he can never be neglected. It was he who, if he did not prepare the place, at least lit the candles in the palace of the consciousness of Whitehall. In that philosophical air he justified sensation to minds already eager for sensation. There were (he said) no motions in the soul. It is an historical and symbolical fact that Charles Stuart escaped from England, driven by the military ardour and spiritual motions of Rice Jones and his comrades, to the city of Paris, where Leviathan had that year been published.

Among the peers and gentlemen who had followed the King to Worcester was Henry, Lord Wilmot. This lord was of a West Country family, of no very great standing; a man of gusto, enjoying his loyalty as he enjoyed his wine, and as apt to quarrel with his companions over the one as over the other. There is nothing to show that he ever cared much about the kind of tree to which George Fox retreated, but he was a gay and gallant companion of the lesser romanticism. He had accompanied Charles from the field, and after the main body of the King's companions had ridden off in other directions, he rode with him to Whiteladies, where the Penderels were. In their house, while the hasty discussions concerning disguise, flight, and safety went on, Henry Wilmot did his romantic best to assist them by setting to work to cut the King's long hair. It was significant devotion; it seems to have been no less significant that he did it badly, so that one of the woodcutters (perhaps more experienced—professional hairdressers were not in every hamlet) had to be called to finish it. On the Saturday which the King spent in his tree, Wilmot lay in concealment in another house some miles away. On the Monday, the King set out to join him. When, again in the dim evening, they met the loyalist master of the house at the great door, Wilmot proclaimed to him the coming of the King in a fine phrase of rhetoric: "This is your master, my master, the master of us all."

The King, through the weeks that followed, went in disguise. Henry Wilmot, except for a hawk on his wrist, refused disguise. Certainly it was more necessary for Charles, who had the more noticeable figure—"almost two yards high," the Parliamentary proclamations called him. It is romantic that the King should have been disguised, and just as romantic that the Lord Wilmot should not. Sometimes together, sometimes separate, they rode on through those dangerous weeks towards the coast; and after them, in one form or another, rode the spiritual mystic, more deeply romantic than either—Serjeant Obadiah Bind-their-kings-in-chains-and-their-nobles-with-links-of-iron. The future, however—the intellectual future—was to be neither to the noble nor the Serjeant. Wilmot had left behind him, at his estate of Ditchley, in Oxfordshire, his wife and a young son, then four years old, John. When that child grew to manhood he was to find, for most of his life, his nearest kinship in the inverted romanticism of the King. But both Fox and Hobbes were to have their part in John Wilmot; their great names describe different and contending states of his being. It was in the contention between those two states, and in the comment upon them of the third state, which can more properly be attributed to Charles Stuart, that the significance of John Wilmot's life was to lie.

When at last the little ship from Brighthelmstone containing Charles Stuart drew in to Normandy, the Lord Wilmot continued to be romantic in exile, though with little active success. He had, like Burnet, a mighty desire, but his gusto was for more possible things. The enthusiasms of the beggarly Court were for promises and titles. They asked of the King "very improper reversions because he could not grant the possession, and were solicitous for honours, which he had power to grant, because he had no fortunes which he could give to them." Henry Wilmot was solicitous to be an earl. The King, in those midnight wanderings and rests, had committed himself to warm gratitude to his companion. His companion desired the face value of those words to be justified. It is the disadvantage of kings and lovers that they are so held to their phrases. At first Wilmot asked no more than a general promise of an earldom some day—when it was convenient to the King. The King, grateful for the moderation, promised. Time betrayed him; presently, in the vagrant diplomacy of that vagrant Court, it seemed desirable to send an ambassador privately to the Diet of the Empire at Ratisbon. It was thought that the German princes might be willing to restore, to support, or at least to shelter, the King, since his more immediate brothers of France and Spain were by now rivals for the favour of the Lord Protector Cromwell. But there was no money to send an ambassador in formal state. Wilmot, seizing the opportunity, proposed that he should be made an earl and go privately. An English earl would be equal to any princes of the Empire, and he promised great results—reputation, money, men. The romantic desire of a title galloped level with the romantic dream of a Restoration; the Lord Wilmot indulged both emotions and found them satisfying. Charles had fewer hopes, but he yielded. The French Government, hoping to get Charles out of the country, supplied the money. Charles supplied the dignity and commission. Wilmot became Earl of Rochester, and the eight-year-old boy at Ditchley, in the custom of the English nobility, became in turn Lord Wilmot.

Wilmot was not the only messenger. Some years earlier the dramatist and (future) theatre manager, Sir Thomas Killigrew, had gone to Venice on something the same purpose. He had done his best; he had even published a full account of a great Royalist victory. Rather unfortunately, as things turned out, he put the scene of triumph at Worcester; months afterwards came the news of the actual battle, and ensured the underhand dismissal of the ambassador, in spite of the horrid reports of the Puritans which Killigrew had spread. He announced that St. Paul's Cathedral, "comparable with St. Peter's at Rome, remains desolate, and is said to have been sold to the Jews for a synagogue." He spoke of the publication of the Koran, "translated from the Turkish so that people may be imbued with Turkish manners, which have much in common with the actions of the rebels." It is true, no doubt, that Mahommedans, Jews, and Puritans all disliked images, but it seems unlikely that the Puritans fell back on the Koran as an incitement against idolatry. "Casting out Beelzebub by Beelzebub" could have no better example.

At Ratisbon the Earl of Rochester secured something like ten thousand pounds from some of the lesser princes. He spent a good deal on the negotiations; he made arrangements with old German officers; he plunged directly into the business of getting an army. It was, however, one thing to get an army; another, to pay it; a third, to use it. Edward Hyde, afterwards the Chancellor Clarendon, who disliked Rochester, commented gloomily: "So blind men are whose passions are so strong, and their judgments so weak that they can look but upon one thing at once." The Earl looked at least on two, as even Clarendon admitted. Having become Earl and been Ambassador, he looked to being Commander-in-Chief. In 1655 news reached the Court of all kinds of possibilities in England—risings in Kent, in the West, in the North. Rochester, signed commissions in his pocket, crossed to London. He was arrested on the way, and released; again arrested, and released; at last he was there. He sat among his friends, good fellows all, and anyone who was bold for the King and gallant with Henry Wilmot heard details of the risings. He sent off his companions, one to the West, one to the North. He wrote the most cheerful letters to the King, who allowed himself to become a little hopeful, and lay at Middleburgh ready to cross. Presently the Earl himself followed to the North. There, in Yorkshire, he became uneasy; preparations were not sufficiently advanced, prospects not sufficiently good. He and his allies "parted with little goodwill to each other," and the Earl set out on his return to London. "He departed very unwillingly from places where there was good eating and drinking"; he was nearly caught at Aylesbury. But the genius of his capacity for solitary romantic escapes stood by him and persuaded the innkeeper to assist him. He got away in time, lay for a while in London, and escaped at last back to Flanders and Cologne. It was his last adventure; in 1657 he died.

Charles Stuart, his romantic followers having failed him, found the realism of General Monk, of the Chancellor Hyde, and of the mass of the English, achieving at last the incalculable thing. The obscure forest of religious search, intellectual speculation, and romantic adventure receded. First London, then Whitehall, lay clear. Himself teased at once by a sceptical mind and an appetite for sensation, he was able to maintain a perilous superiority over the romantics and the anti-romantics by whom he was, and was to be, surrounded. He was to walk sensitively on the borders of the forest of the spirit with a sardonic smile, not much different to that he gave to the suppers at which Lady Castlemaine soon provided him with the sensations of the flesh. Central to himself and determined not to yield that centre to the keeping of any romantic passion, he was content to allow romantic passion as much freedom as he conveniently could. Once at least in his life it got the better of him, when the evil of a romantic horror surged through London, and abandonment screamed round the gallows and shouted from the Bench in the iniquitous myth of the Popish Plot. Once, at the very end of his life, he submitted to a romantic glory, ordered and mediated through the classic instrument of the Roman Church. But both those moments were far off. Cosmopolitan and sceptical, he landed on the beach at Dover. With him, more by accident than design, and without any philosophical intensity, mediated through the desires of the Court, came the sensationalism of Leviathan. Its author had already composed his own sensations by making peace with Cromwell. The King was thirty. On the beach he embraced General Monk, and spoke to him beautifully as "Father." Before thousands of eyes the Mayor of Dover presented him with a copy of a volume full of the myths of the most extreme experiences of man, the Bible. The King looked at it and received it. "Mr. Mayor," says the King, emotionally handing it to one of the Court, "I love it above all things in the world."

John Wilmot was born on 1st April 1647. Such a birthday has a kind of significance. It fits all of us, and John Wilmot especially, but only because he was fooled by Life rather more ostentatiously than most of us are. His genius assisted; his sensitive apprehensions summed up their thwarted desires in several of the most improper poems in the English language. The author of those poems on the failure of fruition, on "the imperfect enjoyment," on the indignant nymph and the impotent swain, was born in the same year in which George Fox seemed to himself to emerge from the entangled forest of the spirit into the paradise of "the hidden unity" which he found on the farther side.

Henry Wilmot had had no temptations to take refuge in a hollow tree from the celestial pursuit, nor had he ever been concerned with Hobbes's philosophical denial that the soul had motions in herself. He had been concerned with a world of more flagrant emotion. His wife, innocently, was related to the more fashionable world of sensation under the restored Monarchy. She was kindred to Barbara Villiers, afterwards Lady Castlemaine, the lurid and termagant mistress of Charles II.; "the most profane, imperious, and shameless of harlots," Macaulay called her, in a prose as shameless as his subject. Anne Wilmot was very different. She, like her husband Henry, came from the West Country; she, like him also, had been married before—to Sir Henry Lee, of Ditchley, in Oxfordshire. John was thus the son of second marriages on both sides. While Henry Wilmot went off to fight for and ride with his King and that King's heir, his own heir lived quietly at home. While Henry diplomatized in fairy-tales for Charles II., Anne devoted herself to the preservation of the estate and the protection of her son. She nourished them both excellently. She was a lady of a firm mind and not very wide sympathies; allusions in the later letters of her son to his wife suggest difficulties between Lady Wilmot and her daughter-in-law. She was a Puritan and the friend of Puritans, but the word covers a good deal; there is no reason to suppose she was harsh or austere. Her friend and co-guardian of the child, Sir Ralph Verney, was also Puritan by inclination, but he had fought on the King's side. In 1647 the lines of division between parties were changing every day, and the most intense desire of most of England was for a quiet life—with the King in possession, if possible; without, if there were no help for it. Lady Wilmot sat still, kept her soul, guarded her son, and hoarded her revenues.

John's horoscope was cast, and remains to us. "The sun governed the horoscope, and the moon ruled the birth hour." Lady of illusions, she did! "The conjunction of Venus and Mercury in M. coeli, in Sextile of Luna, aptly denotes his inclination to poetry." Perhaps, but in relation to the moon, mythical mistress of deceits, the conjunction of love and speed suggests, even more aptly, other characteristics. Venus indeed, most suitably "visible in full daylight," had adorned the day of Charles's birth; she and Mercury conjoined their effectiveness over many ladies and gentlemen of his court. They were the chief planets to rule over the ways that led from the dark forest of wandering minds to the palace of sensual delights. "The great reception of Sol with Mars and Jupiter posited so near the latter bestowed a large stock of generous and active spirits, which constantly attended on this excellent native's mind, so that no subject came amiss to him." Mars was to draw his active spirits to war with the Navy; Jupiter may have moved them to set up as a quack in Tower Street; it must have been the pride of Sol that so enraged his generous spirits as to allow them ungenerously to know of footmen with cudgels set in ambush for John Dryden.

In the education of her son Anne Wilmot had the assistance of Sir Ralph Verney, and of the Reverend Francis Giffard, her chaplain. Since, after the Revolution, Giffard was one of those who refused to take the oaths of allegiance to William and Mary, it is to be supposed that he too was a Royalist of strong principles. After his retirement he lived at Oxford, and there vented his reminiscences on the antiquary Thomas Hearne; it was then 1711, sixty years after he had educated John. He recounted, a little mysteriously, how he used "to lie with him in the family to prevent any ill accidents." The boy was then under twelve, for at twelve he left home for Oxford. Presumably Mr. Giffard succeeded, for he remembered his sometime charge as "very hopeful," "very virtuous and good-natur'd," "ready to follow good advice," "well-inclined to laudable undertakings." Hearne had heard different reports of John's later manhood. By 1711 John Wilmot had been dead for more than thirty years, but his reputation still burned. He was spoken of as "mad Rochester" and "the mad Earl." But the accounts of his childhood are all alike benign. He went from Mr. Giffard's teaching to the Grammar School at Burford. They found him extremely docile and extremely industrious. In Latin especially he was noted as being of extraordinary proficiency. It was a period when attention was paid to the distinguished young, and part of the attention was to see that they repaid the rest of it with all the diligence they could.

There is, however, no reason to doubt that the young John was both docile and industrious, an exemplary student. He was always apt to learn; the Court later found him as exemplary as had Mr. Giffard. He outwent his teachers and his examples—the Court, Cowley, Gilbert Burnet—all except the King. In such promise he went up, 15th January 1660, to Oxford, a fellow-commoner at Wadham.

It had originally been intended that Mr. Giffard should accompany him—so Mr. Giffard said—"and to have been his governor, but was supplanted." Mr. Giffard reluctantly abandoned Oxford and remained in the country, where the Countess of Rochester engaged earnestly in politics, being active to secure the return of her other son, Henry Lee, and Sir Ralph Verney to the Convention Parliament of 1660. At Wadham the young Earl, under the care of the University authorities, pursued his studies. In May 1660 the first cloud of distraction appeared. Under the Protector's rule, the English weather had not been usually propitious to such clouds; an overpowering sun of godliness threw a drought upon the land. With the return of Charles Stuart a thirsty people rejoiced. The King was up; Puritanism was down. Loyalty and liberty came back, and riot ran to meet them. The King might love the Bible, as he told the Mayor of Dover, beyond all things in the world, but the English in general were very ready to love a number of other things almost as much. They had, for some years, been compelled to be monogamous to the Bible. Even at Oxford a little sensational polygamy was felt to be desirable. There were revels and riots. There were almost, in comparison with the past, orgies; there were certainly delights, and they attracted John Wilmot. "He began to love these disorders too much." Till then he had had no disorders to love. The first chance, and still more the first sense, of outbreak, of a kind of communal outbreak, ran across his quick and vivid mind. He was just thirteen. He had docilely explored Latin and the great classics. At the moment when his own sense of liberty and power was growing in him it was met by a sudden enthusiasm of liberty and power from without. The King's return meant all this, and accidentally it meant something more. John Wilmot was now, by his father's death, Earl of Rochester; he was the son of the King's friend. It meant a good deal more now than it could have done before. He had been taught loyalty, but now he was in possession of lordship. His family and his University had exalted the person of the King; all the nation rejoiced in the person of the King. He was—and at thirteen in the seventeenth century he must have known it—one of those who had access, in the due future, to the Court and the person of the King. Many were looking forward to place and title, but he had a title already, and could have a place.

He produced a poem, or so it was said. It was also said later that one of his tutors, Dr. Whitehall (prophetic name!), a physician, of Merton, had actually produced it, and affixed his pupil's name to it. It seems almost certain that Dr. Whitehall had a hand in it, so advanced is it for thirteen years, even the thirteen years of the seventeenth century. The opening quatrain has in it something of the last mad metaphors of the metaphysical poets. It may be hoped, and perhaps believed, that the future "mad Earl" wrote a good deal of it. His wildness was always akin to theirs, and he admired Cowley, we know. Cowley might have written:

Vertue's triumphant Shrine! who dost engage

At once three Kingdoms in a Pilgrimage;

Which in ecstatick Duty strive to come

Out of themselves, as well as from their home.

So the Earl, or his tutor, addressed Charles. Dryden, on the same occasion, was plunging as wildly into a similar religious metaphor. He assured the King

It is no longer Motion cheats your view,

As you meet it, the Land approacheth you.

The Land returns, and in the white it wears

The marks of Penitence and Sorrow bears.

So useful to poets are the white cliffs of Dover. But the comparison of Charles to a triumphal shrine of virtue had even less exactitude of detail to recommend it. If Rochester wrote it, it was his first poem to the King, and the last in that particular style. His later addresses were quite different. The conclusion of his poem differed from Dryden's. The greater John had written an earlier poem upon the death of the Lord Protector, to which he did not now refer. He contented himself with saying that the world would now have a monarch, "and that Monarch You." (The italics are Dryden's.) But Rochester was able to end by recalling, if not his own past, at least his father's; he alluded (great Sir) to Henry Wilmot's "daring loyalty." Perhaps at the moment Charles preferred Dryden's, if he saw either; there were too many recollections of daring loyalties appearing in hopeful joy about his path.

Dr. Whitehall seems to have been an actual example of the semi-fabulous, less reputable, Church of England clergyman of the time. He had been brought up at Westminster under the great Busby, and had thence become a student of Christ Church. In 1648, at a parliamentary visitation, he was asked whether he would submit to their authority, and answered:

My name's Whitehall, God bless the poet,

If I submit the King shall know it.

Provoked by the royalism and unplacated by the rhyme, the visitors turned him out. In 1650, however, he came back, this time to Merton, as a Fellow. It was commonly reported that he had gained this favour by subservience to the Ingoldsby family, who were his neighbours in the country, and especially to Richard Ingoldsby, the regicide, "before whom he often acted the part of a mimic and buffoon on purpose to make him merry." The riotous heart of Whitehall proceeded to occupy itself with physic and poetry. He remained in favour with the Government, being made a Doctor of Physic in 1657 at the letters of Richard Cromwell, then chancellor of Oxford. He produced a number of Latin poems in honour of Oliver Cromwell, Richard Cromwell, King Charles II., and Lord Clarendon; and certain English poems of quite another type.[1] He produced one poem to his pupil Rochester, sent with a portrait of himself, from which we gather that he had, in a practical way, assisted his pupil's levity as well as his learning:

Tis not in vest, but in that gowne

Your Lordship daggled through this towne

To keep up discipline, and tell us

Next morning where you found good-fellows.

It ends with a jest, more dexterous than decent, and was sent to the Earl five years later, on New Year's Day 1666/7.

Under such instruction, therefore, Rochester resumed his studies, with docility if not with enthusiasm, and with sufficient industry to allow him in the autumn of 1661 to take his M.A.. The ceremony of bestowal of degrees was that year presided over by a great personage—the Chancellor of the University who was also Chancellor of England, the Lord Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon. He was something even more than this, though dangerously and against his will, for his daughter Anne had but lately married the heir-presumptive to the Throne, James, Duke of York. This figure of ancient loyalty, which was now by that marriage almost a figure of semi-royalty, and yet was already beginning to appear to the younger courtiers in London a mere figure of fun, sat in the high seat and ceremonially shook hands with the young Masters, among whom was his own third son Edward, then about seventeen. As the slender figure of the fourteen-year-old Earl, Dominus Rochester, appeared before him, some sudden tenderness moved the old man: a recollection of days of exile when Henry Wilmot and he, antipathetic though they may have been, shared a common poverty in Paris, or an apprehension of the restored world into which the young heir of Wilmot was advancing. He distinguished the boy, it was remarked, by a special grace; he held his hand, drew him near, kissed his left cheek, and dismissed him with special benignity. With the presentation, in the next year, of four silver pint-pots to Wadham, my lord's connexion with the University closed.

In 1662 or thereabouts my lord went abroad. His governor was a certain Dr. Balfour—also, like Dr. Whitehall, a physician. They passed through Paris, France, Italy. He was at Padua during October 1664. Europe was everywhere turning from the darkness of the Wars of Religion to the cooler and clearer age of Louis XIV., the boy who was on the point of assuming the government of France into his own hands. The form of Louis stands at the entrance to one of the high-roads through that aged forest of men's imaginations, the high road of the Roman clarity of dogma upon which so much of the culture of Europe walked—a road barred in England to all but a minority of obstinate devoted souls, and regarded by others, equally devoted, such as John Bunyan in his prison at Bedford, as not much unlike a direct pathway to hell. With such things John Wilmot was not concerned. He gathered up his experiences, his adolescence took on the bright colour of courtliness and the gentle hardihood of Courts; and—more interestingly—he returned, in that courtly grace, to his first love. Compulsion had neighboured his boyhood with learning; he began now to woo her of his own will.

It seems to have been Dr. Balfour's work. When the two started, Rochester had not quite recovered from his too much love of those Restoration disorders. He was an official Master of Arts, and that was all. Dr. Balfour set himself to invigorate that mastery, and, on Rochester's own showing, succeeded. In the midst of the polite world of Europe, study came again to her own. Certainly that world encouraged it; letters were still a habit of thought in the high ranks of society. Even so, the world was full of a number of things. Balfour quickened Wilmot's knowledge of one group. My lord's mind, naturally vivid, became more eager. He was disposed to a habit of intelligence and even of philosophy. He was prepared to come to conclusions.

So acquainted with the world of men—men in their books and men in their behaviour; so prepared for whatever his own English world, at its shining centre, had to offer him of loyalty, of learning, of poetry, of love; delicately metaphysical, sensitively expectant, he returned. There was in him, as in Gilbert Burnet away in Scotland, a formative desire for "an intimate apprehension of extraordinary impulses," natural to youth, but especially strong in this youth. He had (they say) at this time a rare and striking modesty; he was docile to the impulses of the world. So prepared, at seventeen years old, tall and slender, well-bred, capacious of experience, he returned. In the year 1665 he made his first appearance in the galleries of Whitehall.

From that day my lord's life is shown us by a series of momentary flashes rather than in continuous sequence. It is even impossible to be certain of the proper order of all the flashes. Some are dated, some are approximately dated, some are not dated at all. Most of his letters are undated. Nevertheless, the dates we have suggest the possibility of a pattern; even though the pattern must be less justified than in most biographies, it may be as just as most. Picture after picture is flung swiftly before us, until we reach the last more detailed picture of his death. In all there is an energy, an energy which seems to have become almost terrible to the Court in which he moved, an energy of search for something he could not find, an energy of anger and contempt for what, in himself as in others, he did find. He desired significant emotion; they offered him insignificant sensation. He loved it, but felt himself thwarted by it, and they grew afraid of him. Like George Fox among the preachers, like the Fifth Monarchy men in the City, Lord Rochester ravaged his unmeaning contemporaries in a search for meaning. They called him "the mad Earl." His actions provoked the phrase, but his hunger provoked his actions. He desired, like all romantics, a justified passion. In the days of the King's father and grandfather, it would have been more easy to find. Those good, or evil, days were past. A schism was opening in the English imagination: on the one side Fox and Wesley, on the other Pepys and Walpole. The courtiers of heaven and the courtiers of Whitehall were becoming divided, not only in their conduct but in their idealism. The saint and the gentleman and their less intelligent disciples—fanatics and prigs, debauchees and good fellows—were beginning to be at odds. By a trick of Fate Lord Rochester ignorantly found himself on the wrong side. He belonged to the gentlemen, but he was a romantic, and they were not romantic. When romantics cannot find the world they desire, they yearn to create it. The Lord Rochester found, or created, his—on his death-bed.

The details of the Court in which he carried on his search may be postponed until his second arrival at it after two adventures of love and war. On his first appearance he was an immediate success. The King and Lady Castlemaine were gracious. The gentlemen were delightful; the ladies were kind. The Court was always willing to welcome handsome and entertaining postulants of its pleasures. At first John Wilmot was not remarkably different from most of the others, unless indeed it may be taken as a difference that an early and notorious exhibition of action was aimed at marriage rather than simple seduction. Since the lady was an heiress there were reasons for marriage, but there were perhaps others.

In 1665 he was eighteen; it was the year of the Plague, but in May this had hardly begun to appear. There was in London a young woman of good family and, as things went then, good income, Elizabeth Mallet. She was the daughter of John Mallet, a West Country gentleman, and granddaughter of a peer, Lord Hawley. She belonged, therefore, to the outer circle of the Families—those Families who were by now circumscribing the King and hampering the administration of the King's Government. There were a number of suitors. Elizabeth had promised not to marry without the consent of her people—her father, mother, and grandfather. She had, however, also declared that she would "choose for herselfe." The Lord John Butler, the Lord Desmond's son, the Lord Hinchingbrooke, were competing for her. The last was the son of the Earl of Sandwich, Pepys's superior, Admiral of the Narrow Seas, Lieutenant Admiral to the Duke of York, and Master of the Wardrobe. Sandwich pushed his son's suit; there was a kind of understanding. But a greater than Sandwich indicated his pleasure. The King recommended John Wilmot to the attention of Elizabeth.

He had been approached to this end by two personages who, themselves enemies, were united by the requests of the young courtier. Lord Clarendon and Lady Castlemaine had been approached. They both proposed the match to the King. It might have had political advantages. The Lord Rochester was young, he was not under the influence of a father, and there was in his house a tradition of devoted loyalty. Henry Wilmot might not have been much good as the King's servant, no more good than Clarendon had thought him. Sandwich, however, had been definitely Cromwell's man, and though all those unhappy old divisions had been healed, it cannot have seemed an unwise thing to Charles to attach Rochester to himself and a fortune to Rochester. The more strength of men and money the King could have for his privy servants the better. He needed all the counter-weight he could find to the enlarging power of the Families.

In December 1664, Sandwich, saying that he would not go against the King's pleasure, withdrew. But either Elizabeth herself or her guardians were still discontented with Lord Rochester. In view of all the events, it is most likely that it was the guardians. At the beginning of May, "my lord of Rochester is encouraged by the King to make his addresses to Mrs. Mallet." Since the lady was not averse, and since the King was certainly favourable, the young romantic determined to act. At the end of May the Plague had begun to appear, and the Dutch War was in progress. Sandwich was away at sea with the Fleet, commanding the Blue, under the Duke of York. On Friday, 24th May, Elizabeth Mallet came to supper at Whitehall with Frances Stewart, whom gossip asserted to be Lady Castlemaine's chief rival. Supper ended, the ladies parted. Elizabeth entered a coach, in the company and guard of her grandfather Lord Hawley, a man of fifty-seven. It rolled off towards Charing Cross. There, in the twilight, stood another coach, one with six horses. As they came level, sudden voices and noises broke out. The coach was stopped violently; the door was forcibly opened; Elizabeth was invited to descend. Despite Lord Hawley, she was compelled to obey; she was hurried over to the other coach. Two women received her. As soon as she had well entered, the vehicle began to move. She was swept off into the night. Lord Rochester himself, the abduction accomplished, took horse and rode gaily north.

Lord Hawley was more successful in speeding the pursuit than in preventing the seizure. It is to be supposed that he hurried back at once to the palace. Horsemen went out after Rochester, and caught him at Uxbridge. The lady was not so soon discoverable. On the Sunday, 26th May, the tale was about the town. Pepys took it to Lady Sandwich, the wife of his patron. He was able to assure her, to her pleasure, that the King was very angry, and was sending the Earl to the Tower. On the Monday, in fact, warrants flew out. It was the earliest opportunity; on Saturday the news had come too late. A warrant ordered Lord Rochester's conveyance to the Tower; another, his reception there; another, search after the armed men who assisted him, and aid from all men in the still unsuccessful search after Mistress Mallet. Somewhere—perhaps Rochester himself revealed the place; it was of no service to him to defy the King from his Tower prison—she was found and brought back.

Lord Rochester, all agreed, had made his throw and lost. "By consent of all," wrote Pepys, "my lord Hinchingbrooke stands fair, and is invited for her." Lady Sandwich, in considerable nervous excitement, remained in London, against her will. The sickness in the City was spreading, and she was afraid of it. Eleven days later, she was still there. By then news had reached her from sea that the fleets were engaged, and from town that doors were already closed and marked with the red cross of the Plague and the dreadful appeal, Lord, have mercy upon us. Alarmed for her husband and herself, she was compelled to tarry in hope for her son, "my lord Rochester [being] now declaredly out of hopes of Mrs. Mallet."

But within four days after his committal to the Tower, before the end of May, Lord Rochester was petitioning to be let out. He apologized; he implored. His offence, he said charmingly, was due to "inadvertence, ignorance of the law, and passion." He would rather have died ten thousand deaths than incurred His Majesty's displeasure. The King kept him prisoner for almost a fortnight. On 9th June he was released on condition that he surrendered himself to a Secretary of State on the first day of Michaelmas term. Before then he had not only regained but increased his favour. At first, however, he did not remain at Court.

The Duke of York returned with Lord Sandwich and the Fleet, victorious from the battle of Lowestoft; and when, late in July, this time under Sandwich's sole command, the Fleet stood out to sea again, Lord Rochester went with it. The Plague grew, and became sensational, and the great folk fled, and it abated, and they returned. Nell Gwynn appeared for the first time on the stage at Drury Lane in an insignificant part in John Dryden's Indian Emperor, premonitory of the insignificant sensations she was to cause in the King. The Fleet came back, and went out again. More than a year after her abduction, Elizabeth, still unmarried, was discussing her suitors. In February 1666 "a servant of hers" proposed to Sandwich something like an elopement: "to compass the thing without respect of friends, she herself having a respect to my Lord's family, but my Lord will not listen to it but in a way of honour." In August she had Hinchingbrooke in attendance on her at Tunbridge Wells, but they found each other less than agreeable, "she declaring her affections to be settled, and he not being fully pleased with the vanity and liberty of her carriage." By the end of November she was still discussing them. "My lord Herbert," she had said, "would have her; my lord Hinchingbrooke was indifferent to have her; my lord John Butler might not have her; my lord Rochester would have forced her; and Sir (Francis) Popham (who nevertheless is likely to have her) would do any thing to have her." Suddenly she yielded. At least my Lord Rochester had done something; she married him on 29th January 1666/7. A few days afterwards, both Frances Stewart and the Earl and Countess were at the play. The audience in the pit saw them and chattered: "It is a great act of charity, for he hath no estate."

The business of Miss Mallet's estate caused some difficulty. There were negotiations. In the country the Dowager Countess appealed again to Sir Ralph Verney, writing that "the King I thank god is very well satisfyed with it, & they had his consent when they did it—but now we are in some care how too get the estate, they are come too desire to parties with friends, but I want a knowing frind in business, such a won as Sr Raph Varney."

But the possible implication was false. If Elizabeth Mallet married at all for charity, it was for that pure goodwill which is so often felt in the first exchanges of romantic love. Years afterwards, her husband, writing to her, could say that her entire revenue "has hithertoo, and shall (as long as I can gett bread without it) bee wholly imploy'd to the use of yr self and those who depend on you; if I prove an ill Steward att least you never had a better, wch is some kind of satisfaction to Your humble Servant."

[1] He was concerned in an exchange of verse with one Edmund Gayton, "superior beadle of arts and physic," who was likewise turned out by the visitors, but (less fortunate than Whitehall) did not get back until after the Restoration and had to live by his wits in London. It was after the death of Mr. Gayton in 1666 that the great Dr. Fell, at a convocation held to elect his successor in the beadleship, "exhorted the masters in a set speech to have a care whom they should choose, and desired them by all means that they would not elect a poet, or any that do libellos scribere."

Before, however, the experience of marriage opened on Rochester, he had endured a definite defeat of the spirit. He had made, in the metaphysical fury of his adolescence, a demand on the universe which had been refused. Like the Court of King Charles, the court of heaven delayed my lord's imperious request, nor was he allowed to abduct his desire.

He had been in the Tower when the Duke of York brought back the Fleet from his and its victory over the Dutch at the battle of Lowestoft in June 1665. The possible complete destruction of the Dutch Fleet had been prevented by the deliberate lies of the Duke's gentleman-in-waiting, Mr. Brouncker. When, after the battle, the Duke—to whom, as Admiral-in-Chief, the credit was and is due—retired to get some rest, Brouncker went up to the captain of the flagship and told him the Admiral's commands were to shorten sail, and thus check the pursuit of the flying enemy. The captain answered that he had the Admiral's instructions to maintain the pursuit and dare not disobey except on equally explicit instructions from the same source. Brouncker went below, waited a few moments, and went up again with the definite statement that the Duke commanded the ship to shorten sail. It was false, but it was believed. The enemy got away. The Fleet returned to England to refit.

By the end of June it was ready for another expedition. This time it was to be aimed at the Dutch Admiral, De Ruyter, who was returning from the East Indies with treasure ships. But this time the High Admiral was denied the command, since it was thought undesirable that the life of the heir-presumptive should be continually risked in sea-fights. The Fleet was put into the charge of Sandwich, who had joined it on 1st July. The King was on the Royal Charles on that day; a final council was held. The King returned to London, and presently from London, among other charges and instructions, there arrived at the Fleet, as a gentleman volunteer, the Earl of Rochester, bearing a personal letter of recommendation from the King.

He wrote later to his mother: "It was not fitt for mee to see any occasion of service to the King without offering my self, so I desired and obtained leave of my Ld. Sandwich to goe with them." It must be admitted that he had not felt the same impulse of loyalty when the Fleet had originally sailed early in May. Elizabeth Mallet is certainly a reason; he had there an occasion of service to himself, and a romanticism of love instead of war. Elizabeth Mallet, for the time being, was out of reach; the King would not consent to show such extreme placability towards the fond lover as a continued countenancing of his suit would have meant. Neither, however, would Charles encourage Lord Hinchingbrooke. Lady Sandwich had been disappointed. She lay ill at Tonbridge, and the King commended one disappointed lover to the care of another disappointed lover's father. It seems likely that he derived an intellectual sensation of pleasure from the act.

Sandwich had just succeeded, through the good offices of Pepys, in arranging the marriage of his daughter Jemima to Philip Cartaret, son of Sir George Cartaret, Treasurer of the Navy, with unusually good financial results. He received his son's rival with courtesy. "In obedience to your Majesty's commands by my Lord Rochester, I have accommodated him the best I can, and shall serve him as best I can." The young man—he was now eighteen—was sent off to the Royal Katherine, and the Fleet set sail.

It was hoped, by the King, the Duke of York, Sandwich, and a few others, that its business might be easier than seemed probable. Victories on the open sea against the Dutch Fleet were very well, but victories with a minimum risk were still better. Negotiations were in progress with the King of Denmark, who was also King of Norway. If De Ruyter took refuge in a Danish harbour, it was proposed that that King should permit an attack on them there; he was offered half the spoil as inducement, and sufficient secrecy to "cover it from the world." The King was supposed to have agreed. The English ambassador at Copenhagen reported that he "had ordered his Governor to shoot only powder"; presently he added that the Governor was not to shoot at all, only "to storm and seem to be highly offended." Cartaret understood even more, that the King of Denmark had promised "to doe great matters against that Nation." Letters went to Sandwich assuring him that, beyond protest, no action would be taken against the English ships if they attacked the Dutch in a Danish harbour.

By the end of July Sandwich heard that the treasure fleet was in the harbour of Bergen. He detached Sir Thomas Teddiman, with fourteen ships, to attack them. Rochester transferred to one of them, the Revenge, since the great Royal Katherine was not to go; it was supposed there would be no need to venture her. With him went Sandwich's son Sydney Montagu, his cousin Edward Montagu, John Windham, and other gentlemen volunteers—the last two had certainly also been on the Revenge. They, like the Kings of England and Denmark, parted the lion's skin, more gaily than the royal hunters. Three days afterwards, on 3rd August, the young poet wrote an account of the whole business to his mother, with a flourish, "from the coast of Norway, amongst the rocks, aboard the Revenge." There he spoke of the division. "Some for diamonds, some for spices others for rich silkes and I for shirts and gould wch. I had most neede of, but reckoning without our Hoast wee were faine to reckon twice." The jest was literal. The Danish host did not prove as hospitable as had been expected. His churlishness ruined the calculations of the King, the hopes of the Admiral, and the more airy fantasies of the gentlemen volunteers.

The English Fleet reached Bergen on 1st August, and entered the harbour, through the narrow roadstead between the cliffs. The Dutch ships were lying, "incapable of execution." The English took up their position "close to the Dutch ships in the port and under the Castle." Night fell. The three gentlemen on the Revenge—Edward Montagu, John Windham, and John Wilmot—talked together, and their talk was full of presentiments of death. Death certainly was near them. The city they had left but a few weeks before had been filling with it; the perils of the sea on which they sailed threatened it; the battle of the morrow promised it. A darker presentiment than such natural accidents possessed two of them. Edward Montagu said he was sure he should not return to England; he was quite certain he should not. Windham admitted he was half persuaded of a similar fate. Less certain than Montagu, he yet looked forward to death. Lord Rochester heard them; the romanticism of night and sea and battle was around him; and the agnosticism of the future. In a ceremony of solemn oaths he determined to bind death to his will. Montagu, more convinced than the others of his immediate end, would have no part in it; he separated his soul. But Rochester and Windham, under the high Danish castle, the guns yet silent, made an agreement between themselves that if indeed either died, and found himself in any future state, he should appear once more to his friend and declare the truth. Between sky and sea they made their covenant, and confirmed it with "ceremonies of religion"—vows and invocations of God. The dawn came nearer; they went to their duties. The bond of mutual apparition lay close to Rochester's heart.

Edward Montagu's last duty, before the battle began, was to pay a visit to the Danish Governor. All night messengers had been rowing forwards and backwards to the Castle. The Governor had protested against the entrance of so many ships. The English grew slowly convinced that this was not the mere noise with which they had been threatened. Action was being taken, not only on board the Dutch ships but in the Castle. Cannon, powder and shot, and Dutch sailors, were being got ashore and into position. The Dutch ships of the convoy were moved into better places; their broadsides trained on the invaders. The Castle fired a shot as a warning, which broke the leg of an English sailor. The Governor demanded time to communicate with Copenhagen. The English Admiral refused. He sent a last message by Montagu, offering (report said) the Garter. The Governor remained unpersuaded, and preparations for battle went swiftly on. Teddiman called his captains, held a last council, and then, giving them orders not to fire at the Castle, commanded the "fighting colours" to be broken, and let fly his broadside at the Dutch Fleet. The Castle immediately replied. The battle began at dawn; after three hours, before it was yet full morning, the English were compelled to retire.

The smoke was blown by the wind over the English ships. During the struggle something over a hundred men were killed, six captains, and a few of the gentlemen-volunteers. Sidney Montagu, Sandwich's son, fell. On the Revenge the three gentlemen had taken their full part, exposed but unhurt. Towards the end of the battle, Windham, when they were all close together, was seized by a fit of giddiness. He reeled, he almost fell; Montagu caught him. Rochester saw it. In the moment when the two so stood, a single doom was upon them. A Dutch ball struck them both, killing Windham outright and so terribly wounding Montagu that he died within the hour. Did the chance of things attend to men's minds, it might at least, for the mere sake of being exact to their presentiments, have ordered their deaths the opposite way.

In his next day's letter, from "among the rocks," Rochester told his mother of this; of the covenant between spirits he said nothing. But he waited, he expected; by an intolerant romanticism he demanded that death and super-nature should accede to mortal bonds. He expected a vision. No vision came. The grave remained oblivious of his need. He had felt, in their talk, a kind of divination of spirit; "the soul had presages." He had seemed to find a greatness of significant emotion—emotion significant of death and life after death. Days went by; weeks. His emotion remained unjustified. For all the revelation that came, that hour of dark and thrilling engagement might as well not have been. At last he abandoned expectation; there was no hope here of justifying to himself his own capacity of passion. The death of Windham offered him no personal greatness of immediate experience.

Yet the sense of presage remained. Desiring to attach importance to his emotions, he overvalued them. Coincidence existed, but he desired palpable drama. He had a passion for drama, and he desired the unseen world to provide him with a theatre greater than that of the actual world, as that provided a finer than the King's Playhouse in Drury Lane. He was never a poseur, but he was always an actor. It was his misfortune that the Court of Charles Stuart offered him no adequate dramatic parts. He tried to create them even there; he ran from it to create them; anything that was offered him anywhere he was always ready to take. He waited always for his cue, ready to improvise, capable of any gallant and romantic improvisation. The universe neglected his cue. Panting and willing, he waited in the wings, and the right recognizable words never came. Yet he felt them through his wild heart, felt them being spoken, and could not guess where.

At some later date his ardour for supernatural confirmation, for a suitable dramatic resolution of a dramatic crisis, was again excited. It was in the house of his wife's people, the Mallets of Shropshire. The chaplain of the family had a dream that on a certain day he would die. He recounted it to the household, by whom, naturally, he was rallied on his superstition. Their mockery or his own piety rebuked him; half-ashamed, he put it from his mind, and the day approached without his remarking it. On the eve he came into supper. A party of twelve were already gathered; he entered and took his place, the fatal thirteenth. One of the young ladies present noticed the number. She stretched out her arm, pointing at the chaplain, crying out that it was he who would die. He recollected his dream; the accident seemed to confirm it; he sat "in some disorder." A gleam of the supernatural from George Fox's world of portents and miracles flashed across the rational dining-room of John Mallet. The Earl[2] looked at the distracted chaplain; certainly the soul had presages. Mrs. Mallet rebuked her spiritual director, but the thing had too much hold for him to fear his patroness's disdain. He answered that he was sure he should die before morning. They all looked at him, sitting there in perfect health, and tossed the moment's joke aside. "It was not much minded," Rochester said; perhaps none but he and the victim cared. It was Saturday night. On the next day the chaplain was to preach. Presently he withdrew, to work at his sermon in his own room by candle-light. There on the Sunday morning they found him, his candle burnt down, his manuscript spread before him, inexplicably dead.

"These things," my lord said afterwards, "made me inclined to believe the soul was a substance distinct from matter." It was the adequate inclination of his mind; his heart laboured with a riddling desire. "Le cœur," Pascal was writing in France, "a ses raisons que la raison ne connait point." But with the logic of the intellectual heart Rochester was not well acquainted. That needs the imagination which is the companion of spiritual love, as Wordsworth, a poet who was something more than a romantic, has taught us. Behind and before Rochester went the masters of those terrifying syllogisms, the syllogisms which are as much of the blood as of the brain. But another master intervened; "imagination was nothing else but the decay of sense." And Fox, who might have been an interpreter, provincial as he was, was distant, in space and social degree, from my lord. John Wilmot's heart throbbed; "presagefully it beat; presagefully." He could not follow the presages. Something seemed to have been spoken, but not to him.

The visit to the Mallets is undated; it seems probable that it took place after his marriage in 1667. Meanwhile his temporal affairs prospered better than his spiritual. He had returned to the King from his first experience of a double defeat—by the Danes and by the Deity—in September 1665. Lord Sandwich, writing dispatches, referred Charles for particulars to Lord Rochester, "who was present, and showed himself brave, industrious, and of useful parts." At the end of October, Charles bestowed £750 on Lord Rochester, "without account, as the King's free gift." By the next March he was sworn Gentleman of the Bedchamber.

In July he was at sea again, and involved in the battle of 25th July—St. James's Fight, off the mouth of the Thames. The fighting was fiercer than at Bergen. The gentlemen-volunteers lost heavily; one died in Rochester's arms. He had achieved a reputation for courage and a cool head in the Bergen battle. One of the volunteers, Sir Thomas, afterwards Lord Clifford, had spoken highly of his behaviour. He renewed it in his second affair. His immediate commander, Sir Edward Spragge, desired to send a special message to one of the captains with whose action he was dissatisfied. Smoke veiled the signals. It became necessary to lower a boat. Spragge asked for a volunteer; there was a momentary hesitation, in which the Earl offered himself. His offer was accepted. He passed safely through the shot, delivered his message, and safely returned. The action was "much commended by all who saw it."

With that, suddenly, his naval activities ceased. He came back to the Court, being now nineteen, and, so restored to the royal favour, resumed, more discreetly, his pursuit of Miss Mallet. In January 1667 he married her. In March he took up his duties as a Gentleman of the Bedchamber, taking the place of the Duke of Buckingham. He was given, at any rate officially, a troop of horse, and there is some slight reason to think he may have been on duty in June when the Dutch ships were proceeding to the Medway.[3] The warrant for his captaincy in Prince Rupert's Horse is dated 13th June 1667, the day on which the fireships were already in Chatham harbour, and the Duke of Albemarle (formerly General Monk) was hastily organizing the defence. On the previous day the Dutch had entered the river. It is permissible to speculate on a hasty volunteering and at least some hasty willingness to fight. But in general he did no more. He was married; he was in favour; he had tasted the sensations of battle, and now the sensations of the Court were more attractive. Romantic emotions of death had remained unjustified; a realistic sensationalism was a more immediately pleasing thing. There is little to show that he regarded patriotism or the service of the State as a possibly significant emotion. What he wanted, so far as he could, he always took, and he was at liberty to take it now. At least he had shown his courage; it has some bearing on later incidents in his life.

On 21st July 1667 peace was signed at Breda. The King, the Court, and the Earl were free to devote themselves more assiduously to politics, poetry, philosophy, wine, riot, and love.

[2] It is not certain he was there. But he told the story as if he had been.

[3] In 1681, during the King's vengeance on the perpetrators of the Popish Plot, a certain Stephen College was put on trial for high treason. During the trial the following dialogue took place. A witness from Watford, College's birthplace, called to testify to his character, said: "I knew him a soldier for his majesty, in which service he got a fit of sickness which had like to have cost him his life; he lay many months ill, to his great charge." Serjeant (afterwards Judge) Jeffries asked: "Where was it he was in his majesty's service?" and the witness answered: "At Chatham business." The prisoner added: "It was under my lord Rochester." But in 1681 there was another Rochester, Laurence Hyde; it may have been he that was meant.

At some time in those early months at Court, the first social comedy in which Lord Rochester is recorded to have played a part took place. Its exact date is uncertain; it must have been before the end of 1666, when one of the other characters was married and went down to a sedate wedded life in the country. A possible and convenient date would be the early part of 1666, when the Earl was at Court between his two sea-battles, and when he was, for the time being, still out of the royal favour for the favours of Elizabeth Mallet, or the lady had not been persuaded to bestow her own. This comedy then took place between the melodramas of death. It is true that we owe our account of it entirely to Anthony Hamilton, who, when he wrote the Memoirs of the Count de Grammont, regarded himself as an artist rather than as a scholar, and made of facts whatever his taste chose. If we can at all believe it, we must observe Rochester as already—at nineteen—a person of importance, a delight and a terror. He had always an interest in the theatre, and his best part was always himself. It is likely, however, that Hamilton exaggerated—perhaps even invented. But, unless and until we know more, the story cannot be omitted.

The other chief personage in the comedy is a Miss Hobart. Miss Hobart had been one of the Maids of Honour of the Duchess of York, Anne Hyde, daughter of the old Earl of Clarendon. Miss Hobart's shape was good, her wit sufficient, and she had "rather a bold air." More unusually, in that Court, she had a passion for the company of ladies. There had been an intense friendship, and afterwards a coolness, between her and another Maid of Honour, a Miss Bagot. Miss Bagot was the first to withdraw; she let it be understood that she was unable satisfactorily to encounter the warmth of Miss Hobart's affections. Miss Hobart was observed to be solacing herself with the company of a young girl, the niece of the Mother of the Maids of Honour. The Court engaged in agreeable speculation upon Miss Hobart's loves and capacities, and composed verses upon her; the Maids, innocently or scandalously, exhibited reluctance to be intimate with her. Tales came to the ears of the Duchess, who was incredulous, indignant, and embarrassed.

The Mother of the Maids, who had at first been delighted that Miss Hobart should take notice of her niece, became agitated, and consulted the feline grace of Lord Rochester concerning the danger run by the poor girl among Miss Hobart's cushions. Lord Rochester sympathized, and offered his services. Presently the niece, whose name is given as Sarah Cooke, felt the counter-attraction. She swum from the old orbit to the new. Lord Rochester took her under his protection—whatever exactly that meant. Meanwhile the tales persisted. The Duchess removed her favourite from the companionship of the Maids to more immediate attendance on her person. Miss Bagot had also withdrawn; she had married, first, to Lady Castlemaine's annoyance, Charles Berkeley, Earl of Falmouth, and, after his death in battle, Charles Sackville, Earl of Dorset. This depletion of the Maids left two vacancies. Out of a number of candidates the Duchess, in order to fill them, chose Miss Frances Jennings and Miss Anne Temple.

Frances Jennings was the elder sister of a more celebrated lady, Sarah Jennings, whom she afterwards brought to Court, being thus the first instrument of the romantic love between Sarah and John Churchill. Afterwards, when both ladies were Duchesses—Sarah of Marlborough and the favourite of Queen Anne, Frances of Tyrconnel and a fugitive with the Old Pretender—they could not always sustain friendly relations. But as yet Sarah was at St. Albans and no one, and Frances was at Whitehall and very much someone. Exactly what kind of someone she would be she gave her attention to decide. With a just realism she determined "not to dispose of her heart until she gave her hand," and she left both in charge of her head. Until that acquiesced, Frances Jennings determined not to allow any part of her to be at the disposal of peer or prince. The Duke of York made advances; she dropped his notes along the galleries from the pockets into which they had been slipped. She became the admiration and the Duke the amusement of the Court. The King heard of it; ironically sceptical, he thought of testing Miss Jennings in the fire of royalty. But Miss Stewart, though she gave him nothing but smiles, made difficulties about his giving more than smiles elsewhere to Miss Jennings. Charles returned to her, to Lady Castlemaine, and to lesser social spoil. Miss Jennings, a Caroline and sophisticated Una, continued to advance safely through the artificial forest of the links and candles.

Anne Temple was less intelligent, less cool, and (to a degree) less fortunate. She was the daughter of a Warwickshire squire and of the daughter of a Surrey squire; the country had formed her. Almost like a young woman in one of the contemporary theatrical comedies, with fine teeth, fresh complexion, and an attractive smile, she came surprisingly to the Court. Her mouth was prepared to open and her eyes to languish; her heart was ready for vanity and her mind for credulity. She was extremely attractive and extremely silly.

Lord Rochester was nineteen, and had lost his first modesty. He had at the moment nothing to do. He had been engaged recently with a lady, and had received offence, in that connexion, from another of the Maids, a Miss Price. In revenge he had denigrated Miss Price in a copy of verses, by all reports devastatingly intimate, inaccurate, and obscene. But that done, he looked round the Court and observed the new arrivals. It appeared possible to him to derive entertainment from Anne Temple's physical advantages and mental disadvantages. He was becoming used to his power, and he enjoyed acting. He proceeded to act. Miss Temple saw him; she heard that this was the brilliant young lord, the master of satirical verse, of whom all the Court was in fear. He gazed; less wise than Miss Jennings, she gazed back. Presently she discovered that the admiring gaze was fixed, not on her very pretty figure but on her mind. He was impervious, thus he confided in her, to all but intelligential charms. Had it been otherwise, she would undoubtedly have overcome him; as it was, he could enjoy "the most delightful interchange in the world" without any risks of baser excitements. In a passion of intellectual ardour, Miss Temple reciprocated. He produced his latest poems; she listened, commented, was enthralled. It was understood to be almost by accident that these poems so often celebrated Miss Temple's perfections. The subject, they both realized, was immaterial; it was the poetry with which they were concerned.

In fact, one must not too rashly blame the pretty foolishness of Anne Temple. Rochester's poems were quite capable of soaring into an intellectual air. Among those preserved to us is one at least which exhorts Chloris to higher things than pleasure:

Then, Chloris, while I Duty pay,

The Nobler Tribute of my Heart,

Be not You so severe to say

You love me for a frailer part.

Under what name, or if under any of those that remain to us—Chloris, Phyllis, Celia—he admired the polished corners of the Temple, we cannot tell. If he exhorted her to severity, it was poetry; if to union, it was still poetry.

The Duchess beheld the intellectual companionship and deplored it. Her new Maid's head was swimming with new wine. Yet to forbid Miss Temple to entertain Lord Rochester's Muse was as foolish and futile as to forbid her to entertain Lord Rochester. With the one she was wholly intimate; with the other, only partially. The Duchess did not see her way to interfere imperatively either with what was established or with what was perhaps unintended. She consulted and instructed Miss Hobart. Let Miss Hobart break up the conversations, show a friendship for Anne Temple, and intercept consequences which everyone but their victim expected, and perhaps, more than she well knew, even the victim herself. Miss Hobart, remembering the defection of Sarah Cooke, addressed herself, in a double sense, to the charge.

The delighted Court beheld the duel of opposite mysteries of sex. The prize was ignorant of the battle. She had naturally not been able, considering where she was, to avoid some rumour of the side of Lord Rochester's reputation which was not merely terror. She could not escape a suspicion—a not entirely disagreeable suspicion—that he was not quite as impervious to women's charms as he declared. Men, Miss Temple knew, were apt to be moved and thrilled, however pure their intellectual interests. She found Miss Hobart a phœnix of another colour. Miss Hobart could not possibly have designs, which neither, up to date, had Lord Rochester, or so he candidly said. Miss Hobart also said that Anne Temple was clever … and good … and beautiful. Also Miss Hobart had a cupboard of sweets and cordials. Miss Temple adored sweets and cordials.

It was summer. Miss Temple came in one day from riding, her mind running before her to the cupboard. She dismounted; she ran up to her friend's room; she looked in. Miss Hobart welcomed her with a charming freedom. Miss Temple, unwilling to go too far from the cupboard, asked if she might change her habit there. The small effort pokes up absurdly in that high diplomatic conflict of the Hobart and the Wilmot. But it was the sweets that Miss Temple wanted, and she took the obvious way to them. Miss Hobart immediately took the obvious way to what she wanted. She threw aside the dignity of her age and position; she begged to assist her friend. In a delightful harmony the disrobing began.

While it went on, Miss Hobart provided another kind of sweetmeat—more like Lord Rochester's, but in prose. She spoke of the other recent Maid, Frances Jennings—how foolish, how sluttish, how painted, how dirty! how she only washed her face and hands! Miss Hobart, among her duties, superintended the Duchess's bathroom, which was indeed near at hand, with only a withdrawing-room between. The changing finished and the sweetmeats eaten, the two ladies, at Miss Hobart's suggestion, passed into the withdrawing-room. Opposite them, as they entered, was a glass partition dividing it from the baths proper; on the other side of it hung curtains of Chinese taffeta, now closely drawn. By the partition was a couch. The ladies disposed themselves affectionately upon it, and continued to talk; or rather, Miss Hobart continued to talk. Anne Temple, and one other, listened. Within the curtained bathroom, within the bath, indeed—a full bath of cold water—Sarah Cooke quivered and listened.