* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Vol 1, Issue 12

Date of first publication: 1865

Author: John Townsend Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Mar. 15, 2017

Date last updated: Mar. 15, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170325

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. I. | DECEMBER, 1865. | No. XII. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

ver the hills of Palestine

ver the hills of Palestine

The silver stars began to shine;

Night drew her shadows softly round

The slumbering earth, without a sound.

Among the fields and dewy rocks

The shepherds kept their quiet flocks,

And looked along the darkening land

That waited the Divine command.

When lo! through all the opening blue

Far up the deep, dark heavens withdrew,

And angels in a solemn light

Praised God to all the listening night.

Ah! said the lowly shepherds then,

The Seraph sang good-will to men:

O hasten, earth, to meet the morn,

The Prince, the Prince of Peace is born!

Again the sky was deep and dark,

Each star relumed his silver spark,

The dreaming land in silence lay,

And waited for the dawning day.

But in a stable low and rude,

Where white-horned, mild-eyed oxen stood,

The gates of heaven were still displayed,

For Christ was in the manger laid.

Harriet E. Prescott.

“Please tell my Doll a story!” A queer request, certainly; but how could I refuse it, when backed by the pressure of two innocent child-lips, and the pleading sparkle of two large, soft blue eyes, glancing from under a cluster of flaxen curls into my own so eagerly? In fact, I never could, since my grown-up days, refuse the pleadings of the Young Folks. They make me their willing victim. If one of them were to beg me to stand on my head, I verily believe I should attempt the ridiculous feat, although I am a serious old bachelor. But mind, I only mean the young girl-folks.

As for the boys, I leave them to be spoilt by their maiden aunts. So, when Mabel said, between two kisses, “Please tell my Doll a story!” I answered, “Certainly, my dear!” at once. There, however, I paused a moment, for I was in reality quite puzzled to think of a story fit for the ears and intelligence of a bisque doll. Of one thing only I felt sure, and that was that Miss Doll would prove a capital listener, and never once interrupt me by unseasonable questions. Her mistress, however, might make up for the Doll’s reticence in this respect, I feared.

All at once a bright idea occurred to me.

“Well, my dear,” said I, with affected gravity, “if I am to tell your Doll a story, you, of course, need not hear it, and I will therefore whisper it in her ear.”

“O, but then Fanny’s and Edith’s Dolls will not hear it either!” exclaimed Mabel, anxiously.

It was clear that my stratagem would not do. I was in for it, and must yield as gracefully, and perform my task of story-telling as successfully, as possible. But I made one more strategic effort. “Well, then,” said I, “if I am to have three Doll listeners instead of one, of course I cannot whisper. So, my dears, make your Dolls sit round me, and order them to be very quiet and attentive while I am speaking; and then, as soon as you go to your play in the other room, I will begin.”

At this hint, however, there was instant revolt. Three clear, fresh voices cried in chorus: “O, but we want to hear too! we want to hear too!”

I surrendered at discretion, without more ado; and the three Dolls being accommodated with three chairs from the baby-house, each by the side of her little mistress, I took a very slight pinch of snuff by way of stimulus, and set off as follows:—

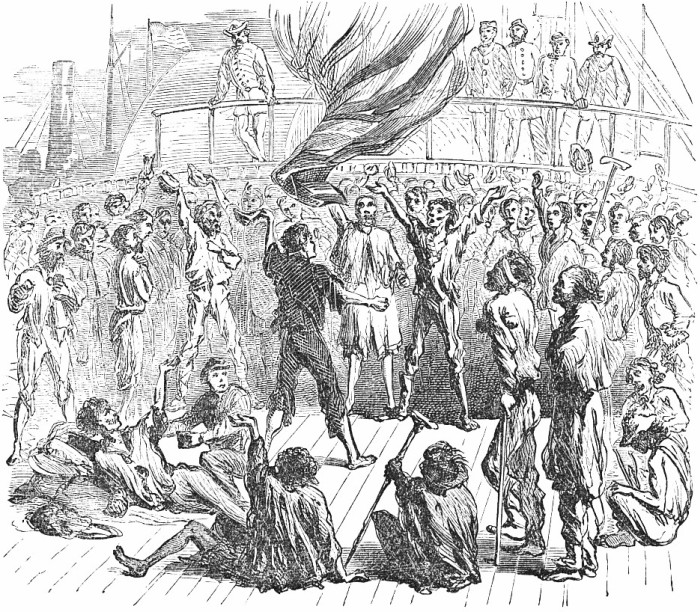

“Ever so long ago, when Miss Mabel’s little feet were as far above the hem of her frock as they are now below it, and when Miss Edith thought ‘Ta-ta’ was Saxon for ‘Good-by,’ and when Miss Fanny took her chief exercise in a jumper,—and this ancient period is far beyond your recollection, young ladies (I speak to the Misses Doll, of course),—ever so long ago, then, a lady of my acquaintance asked her doctor to hint to her husband that a sea-voyage would do her a vast deal of good, provided she could consult a Parisian doctor at the farther end of it. So the obliging doctor dropped a hint of the kind in season, the more willingly that he really did think such a trip would be of service. And the husband took the hint, like a dear, darling fellow as he was, and in due time Mr. Bayward and Mrs. Bayward and Miss Hattie Bayward went on board a great steamer, which foamed out of the harbor, and plunged and tumbled through the ocean waves for eleven days, and foamed into another harbor, and, in short, carried my friends safely to Havre, on the coast of France, from which town they went directly to the great city of Paris.

“I cannot begin to tell you of all the beautiful and wonderful things they saw in that grand city; and, besides, this would not be a real part of my story, which, I may as well inform you at once, is chiefly about my little friend Hattie Bayward, who was a sweet little girl of ten years old, with eyes as blue as Miss Mabel’s, a nose as straight as Miss Fanny’s, and a mouth as cunning as Miss Edith’s when she kisses her old bachelor uncle good-night. Hattie had been very sick in the steamer, and had so many cries that her blue eyes were quite dim, and her cheeks pale, and her temper, I am afraid, a little the worse for wear, for the first few days after her arrival in Paris. So her mother hired a nice, pleasant-faced French nurse, with the queerest of white caps, and the brightest of striped and plaid and spotted neck-handkerchiefs, and the funniest of gestures and grimaces when she talked; and this nurse, whose name was Marie, used to take Hattie out to walk in the gardens of the Tuilleries, and along the Champs Elysées, whenever the day was fine. If you do not know what the Tuilleries and the Champs Elysées are, I must tell you the Tuilleries is the royal palace where the king or emperor lives when he is in Paris, and the Champs Elysées, or Elysian Fields, is the name of a beautiful park, with a broad drive in the centre, and a delightful walk all among groves of trees, and pretty pavilions, and Punch-and-Judy shows, and swings, and merry-go-rounds, and I don’t know how many things beside, that the young folks are fond of.

“Well, one day, as Marie and Hattie were walking along in the Champs Elyseés, they suddenly saw coming swiftly toward them from the grove in front—what do you think?”

I own I put this artful question for the purpose of taking a little breath, and a very small pinch of snuff; and as I paused to do this comfortably,—

“I guess it was the Emperor!” cried Mabel. I shook my head, solemnly.

“I think it was Punch and Judy,” said Edith. Another shake.

“O, I know! I know!” exclaimed the clever Fanny, who had heard her cousin Edwin talk about the sights of Paris, whence he had just returned; “it was the little Prince in his pony-chaise, wasn’t it, Uncle?”

“I am sorry,” said I, with mock severity, “that I cannot tell a story to three little ladies,” bowing to the Dolls, “without having their pleasure spoilt by interruptions from others who are kindly allowed to listen, but certainly have no right to speak. And who might take example,” I added, slightly smiling, “from the very respectful silence of the three little maids”—again nodding to the Dolls—”for whose special entertainment my story is told. Ahem!”

The young folks hung their heads doubtfully for an instant, but Mabel, happening to look up, and catching a twinkle in my eye, cried gayly: “O Uncle, you are funning! I know you are. Fanny! Edie! Uncle is only funning!”

“Well,” said I, “perhaps I am; but as you have been naughty, you must pay a forfeit; so give me a kiss all round, and let us go on with the story, and not keep the company”—looking at the Dolls—“waiting longer.”

“But wasn’t it the Prince?” whispered Fanny, as she paid her forfeit—twice, by mistake, I suppose.

“Not exactly, my dear,” I replied. “That which attracted Hattie’s attention, and caused her to exclaim, in pretty fair French, (for she had by this time learnt to chatter quite nicely with Marie,) ‘Look! Marie! how lovely!’ was—a low, open, miniature carriage or barouche, drawn by six milk-white goats, with bright harness, and pink ribbons fluttering from their ears, and, seated in this fairy-like equipage, a charming little girl of about Hattie’s age, beautifully dressed, and by her side the most elegant, lovely, splendid Doll that Hattie had ever seen,—far more splendid, indeed, than she had ever dreamed there could possibly be in the whole world of Dolls! ‘Hold!’ exclaimed Marie, throwing up her arms, and smiling all over her face; ‘it is my little Adèle!’ And she ran to meet the brilliant little maid, dragging Hattie along with her.

“When Miss Adèle saw Marie she also seemed delighted, and there was a great deal of kissing and hugging and chattering, you may be sure; for Marie had been Adèle’s nurse for three years, and had only left her two years before, because Adèle’s mother, who was a very rich French lady, was going to Italy, and Marie would not leave her dear France, even for Adèle. And here was Adèle back, and she did not know it!

“All this time Hattie’s eyes were fixed on the Doll, as eagerly as the wolf’s were on poor little Red Riding-Hood, and with almost the same feeling, too, for she wished to own that Doll, with all her heart and strength.

“At length Marie introduced Adèle to Hattie, and the French girl was very polite, and offered to give Hattie a ride; and Hattie rode up and down several times in the elegant barouche, and was very much pleased indeed; but still her greatest delight was when Adèle gave her the Doll to hold, and let her examine its dress, and hat, and gloves, and boots, and its necklace, and ear-rings, and breastpin, and parasol,—and above all when she was shown how to make it say, ‘Ma-ma! Pa-pa!’ by pulling two cords hidden under its clothes. Those two hours that Hattie spent with Adèle were like a delightful dream to my little friend. But when she went home, her little heart was swelling with envy and desire, and she was really very sad and unhappy, because her mother told her she could not afford to buy her such a costly Doll as that she described, of Adèle’s, and that it was almost wicked to wish for such a one.

“Hattie went to bed that night very mournfully, and lay tossing a good while before she fell asleep, though she was a little comforted by Marie’s promising her that she should play with Adèle and her Doll again the next day, and as often as she pleased afterwards.

“Sure enough, the next day Marie and Hattie met Adèle and her nurse again, this time in the Tuilleries garden, where they fed the swans in the fountain, and played with the famous Doll, and had a lovely time altogether. And almost every day for the next fortnight the little girls continued to meet in this way, until Hattie, who was a really good and sensible child, ceased to envy Adèle the possession of her Doll, and learned to feel contented without it, and told her mother that she had ‘conquered the bad feeling,’—which pleased Mrs. Bayward very much,—so much, that she secretly resolved—but that was of no consequence, as it happened. Well, one day, about three weeks after their first acquaintance, Hattie and Adèle were playing together by the fountain in the palace garden. It was a sultry day, and all the other children and nurses, as well as the rest of the folks in the garden, had retired under the trees, which are a good way from the fountain. Marie and Adèle’s nurse had both frequently called the children away from the water into the shade; but they had constantly returned to it, for Adèle was teaching her Doll to feed the swans, and had not thrown them all her cake yet. So Marie and her companion had seated themselves for a chat under a tree, and, a couple of soldiers whom they knew coming along, they were so deeply engaged in talk as almost to have forgotten their little charges.

“ ‘Now, Mimi,’ said Adèle, (Mimi was the Doll’s pet name), ‘take this, and throw it well,—dost thou hear?’ She held a piece of cake in the Doll’s little hand, and gave the arm a fling! Alas! she jerked it so violently, that poor Mimi jumped out of her arms, and went headlong into the water. You would think that Adèle ought to have cried out as loud as she could at this accident, my dears; but she did not. On the contrary, she stopped Hattie, who was about to do so, by saying, ‘Be still! Lina will take me home if she sees us, and perhaps strike me besides. I can reach Mimi, see!’—and kneeling quickly on the edge of the basin, she stretched forward until her hand touched the dress of the floating Doll. But the effort she made to catch hold of Mimi’s frock threw poor Adèle so far over the edge that she lost her balance, and down she went, head first, into the clear, cool fountain! She did not even have time to shriek, but only gave a little smothered cry, which did not attract the attention of the people under the trees in the distance.

“Hattie, however, was there; and, like a brave little heroine, she shouted, ‘Help! help!’ as loudly as she could, and, without a moment’s hesitation, leaped into the basin after her unfortunate little friend.

“The water was not very deep, and Hattie seized Adèle stoutly by her dress, and strove to drag her to the edge of the basin. But the little French girl struggled blindly and wildly, and would soon have drowned both herself and her heroic companion, had not help arrived in time to rescue them both from certain death. You may imagine how terribly frightened Mrs. Bayward was when Hattie was brought home in a cab, all dripping wet, and half fainting, with Marie wringing her hands and going on like a crazy woman; for she felt that it was chiefly her fault, and that of the other nurse.

“And you may also fancy the scolding Marie got, and richly deserved, from her mistress. Indeed, but for Hattie’s pleading, her careless nurse would have been sent packing at once. But Hattie took the blame upon herself and Adèle for their disobedience; and this was right, too, since they had refused to mind their nurses’ repeated calls to come away from the fountain.

“A good rubbing, with a hot drink and a couple of hours in bed, put Hattie to rights again, and her mother then heard her account of the adventure. You may be sure she felt proud of her brave little Yankee girl!

“But Adèle’s mother heard the truth, too; and that very evening she called and sent up her card,—‘Madame the Viscountess of Monteau’; and such a scene of gratitude, and embracing Hattie over and over again, and pressing Mrs. Bayward’s hands, and saying the same things over dozens of times, you never saw nor heard of in this plain land, I’m sure!

“Just before Madame de Monteau took her leave,—having made Mrs. Bayward promise to let Hattie come and see Adèle the next day,—my little friend looked at the lady, and ‘How is poor Mimi?’ she asked, anxiously.

“ ‘Alas! my dear little one,’ replied Adèle’s mother, ‘I fear Mimi is hopelessly drowned. At all events, she is disfigured for life. But there are other Mimis!’ added she, smiling mysteriously, as she caught Mrs. Bayward’s eye. And then she went away.

“Hattie went to see Adèle next day, and Adèle’s father called on Mr. Bayward; and so the two families grew quite intimate during the month longer that my friends stayed in Paris. Adèle had a new Doll as lovely as Mimi, and she called it Mees Hattie, after her American playmate. On the day of Mrs. Bayward’s departure from Paris, a servant in livery brought a large box, tightly screwed up, to her lodgings, with a little note from Madame de Monteau, in which she asked that the box might not be opened until her dear friends should reach their home in America. This box was addressed, in large letters, ‘To my dearest Hattie; from her grateful and loving friend, Adèle.’ Mr. Bayward managed to have it stowed among the luggage without letting Hattie see it, and she knew nothing of it until her arrival at home. Then, one bright morning, when several of her little cousins and friends were with her, her father called them all down into the drawing-room, and set the mysterious box, with the screws all taken out, on the centre-table, saying: ‘Here, Hattie, is something for you from your little French friend, Mamselle Adèle. Suppose you let us all see what it is.’

“Hattie blushed crimson with sudden pleasure, as she slowly lifted the lid of the great box, and the moment her eye caught a glimpse of the contents she gave a cry, and sprang up and down several times, in the excess of her joy. ‘Take it out, papa, please! I cannot lift it,’ she eagerly exclaimed.

“Her father put his hands into the box, and lifted out a large glass case, in which stood, upon a pedestal, a magnificently dressed and beautiful Doll, almost as large as Hattie herself! A perfectly splendid Doll, to which ‘Mimi’ and ‘Mees Hattie’ were as mere rag-babies!

“ ‘Oh! Oh! Oh! I am so happy!’ cried dear little Hattie. And she instantly kissed her father, then her mother, and then all her cousins, and everybody in the room, including her old bachelor friend, who has now finished The Doll’s Story.”

“And we will kiss our old bachelor friend, too!” cried Mabel, and Fanny, and Edith, suiting the action to the word.

But the three Dolls never even said as much as “Thankee!”

C. D. Gardette.

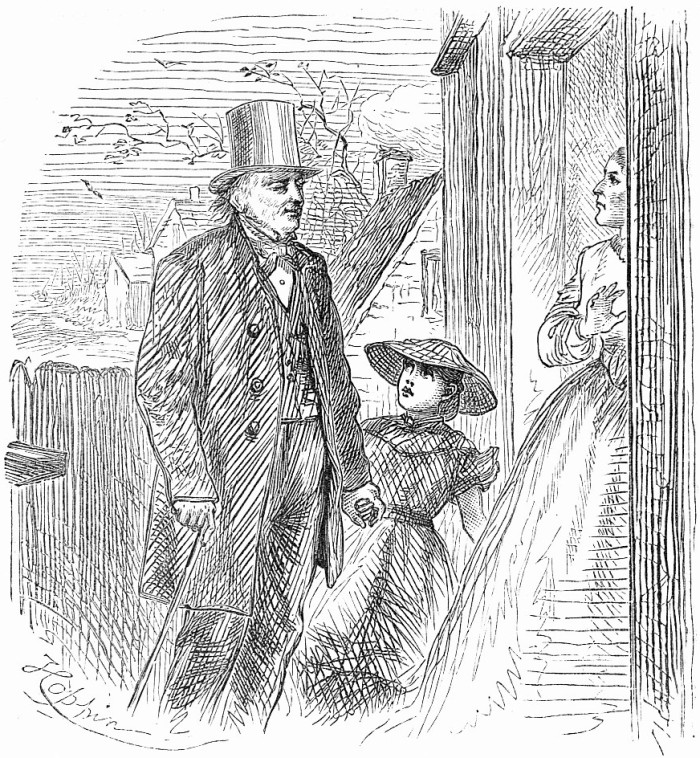

The party soon took their departure. As this was the first time that Uncle Benny had been over Mr. Allen’s farm, he was proportionately surprised at what he had there seen and heard, and felt vexed with himself at having thus long overlooked so useful a school of instruction which stood open almost at his very door. But he treasured up the valuable hints he had received, and was ever ready to set before the Spangler boys the strong moral of the example they had so fortunately witnessed. The incidents of the afternoon formed the staple of their conversation during a slow homeward walk. Tony King had been powerfully impressed by them. They seemed to operate on his young mind as discouragements to hope, rather than as stimulants to perseverance and progress. He had let in the idea that the distance between his friendless condition and the prosperous one of Mr. Allen could never be overcome by any effort he could exert. In this frame of mind he suddenly exclaimed, looking up to Uncle Benny, “How I wish I had some friends to help me on!”

The old man stopped, surprised at this explosion of discontent, and replied by saying, “Tony, you have a dozen friends without appearing to know it.”

“Who are they?” he eagerly inquired.

“Hold up your hands!” replied the old man. “Now count your fingers and thumbs. There! you have ten strong friends that you can’t shake off. There are your two hands besides. What more had Mr. Allen, or the little pedler who sold you that knife? They began with no other friends, no more than you have, and see how they have carved their way up. If you can’t use this dozen of friends to help you on in the world also, it will be your own fault. It will be time enough for you to pray for friends, when you have discovered that those you were born with are not able to provide you with what you may need.”

Before Tony could reply to this home thrust, a little garter-snake, only a few inches long, came running across their path, directly in front of the boys. Bill Spangler, observing it, cried out, “Kill him! Kill him!” and Tony also noticing the delicately striped little creature, as well as that it was hurrying out of the way as quickly as it could, instantly jumped upon it, and with his heavy boot stamped it to death at one blow.

Now, in most men, and certainly in all boys, there seems to be an instinct that must be born with them, which impels them to kill a snake whenever he happens to come within reach of boot or stick. If not a natural instinct, descending to them from our first mother, it must be one of those universal propensities that boys learn from each other with the ready aptitude of youth, and with a sanguinary alacrity. It is another great illustration of the strength of the imitative faculty among our boys. It is of no moment what may be the true character of the poor wriggler that happens to cross their path, whether venomous or harmless: the fact of its being a snake is enough, and if they can so contrive it, it must die.

It was this propensity that caused Bill, the youngest of the three, to shout instantly for the death of the little garter-snake, and impelled Tony to spring forward, with sympathetic promptness, and stamp its life out. There was not a moment’s pause for thought as to whether the creature were not in some way useful to man, nor had either of the boys been taught to remember that, even if a living thing were of no use, there was still room enough in the world for both them and it. Hence, no sooner had the snake come within sight than its fate was sealed.

Uncle Benny did not belong to that class of men who think themselves justified in killing insects or reptiles wantonly, merely because they happen to be disagreeable objects to look upon. The slaughter of the poor snake had been accomplished with so much suddenness that he had no time to interpose a good word in its behalf, or he would have gladly spoken it. The act was therefore a real grief to him, not only from pity for the harmless creature whose body still writhed with muscular activity, even after consciousness of suffering had departed, but because it showed a propensity for inflicting needless pain on the unoffending brute creation, which he had never before seen developed in these boys.

“That was very wrong, boys,” said the old man; “that snake did you no harm, nor could it injure any one. On the contrary, these field snakes of our country are the farmer’s friends. They devour insects, mice, and other enemies to the crops, but never destroy our fruits. They do not poison when they bite. They are not your snakes,—you did not give them life, and you have no right to take it away. There is room enough in this world for all living things that have been created, without a single one of them being in your way. Now get up here.”

Saying this, he mounted himself on a huge rider of Spangler’s worm fence, and, when the boys were all seated beside him, produced a newspaper from his pocket, and, observing that he was going to give them an extract from a lecture of the Rev. Mr. Beecher, proceeded to read the following appropriate sentences:—

“A wanton destruction of insects, simply because they are insects, without question as to their habits, without inquiry as to their mischievousness, for no other reason than that wherever we see an insect we are accustomed to destroy it, is wrong. We have no right to seek their destruction if they be harmless. And yet we rear our children without any conscience, and without any instruction whatever toward these weaker creatures in God’s world. Our only thought of an insect is that it is something to be broomed or trod on. There is a vague idea that naturalists sometimes pin them to the wall, for some reason that they probably know; but that there is any right, or rule, or law that binds us toward God’s minor creatures, scarcely enters into our conception.

“A spider in our dwelling is out of place, and the broom is a sceptre that rightly sweeps him away: but in the pasture, where he belongs, and you do not,—where he is of no inconvenience, and does no mischief,—where his webs are but tables spread for his own food,—where he follows his own instincts in catching insects for his livelihood, as you do yours in destroying everything, almost, that lives, for your livelihood,—why should you destroy him there, in his brief hour of happiness? And yet, wherever you see a spider, ‘Hit him!’ is the law of life.

“Upturn a stone in the field. You shall find a city unawares. Dwelling together in peace are a score of different insects. Worms draw in their nimble heads from the dazzling light. Swift shoot shining black bugs back to their covert. Ants swarm with feverish agility, and bear away their eggs. Now sit quietly down and watch the enginery and economy that are laid open to your view. Trace the canals or highways through which their traffic has been carried. See what strange conditions of life are going on before you. Feel, at last, sympathy for something that is not a reflection of yourself. Learn to be interested without egotism. But no, the first impulse of rational men, educated to despise insects and God’s minor works, is to seek another stone, and, with kindled eye, pound these thoroughfares of harmless insect life until all is utterly destroyed. And if we leave them and go our way, we have a sort of lingering sense that we have fallen somewhat short of our duty. The most universal and the most unreasoning destroyer is man, who symbolizes death better than any other thing.

“I, too, learned this murderous pleasure in my boyhood. Through long years I have tried to train myself out of it; and at last I have unlearned it. I love, in summer, to seek the solitary hillside,—that is less solitary than even the crowded city,—and, waiting till my intrusion has ceased to alarm, watch the wonderful ways of life which a kind God has poured abroad with such profusion. And I am not ashamed to confess that the leaves of that great book of revelation which God opens every morning, and spreads in the valleys, on the hills, and in the forests, is rich with marvellous lessons that I could read nowhere else. And often things have taught me what words had failed to teach. Yea, the words of revelation have themselves been interpreted to my understanding by the things that I have seen in the solitudes of populous nature. I love to feel my relation to every part of animated nature. I try to go back to that simplicity of Paradise in which man walked, to be sure at the head of the animal kingdom, but not bloody, desperate, cruel, crushing whatever was not useful to him. I love to feel that my relationship to God gives me a right to look sympathetically upon all that God nourishes. In his bitterness, Job declared, ‘I have said to the worm, Thou art my mother and my sister.’ We may not say this; but I surely say to all living things in God’s creation, ‘I am your elder brother, and the almoner of God’s bounty to you. Being his son, I too have a right to look with beneficence upon your little lives, even as the greater Father does.’

“A wanton disregard of life and happiness toward the insect kingdom tends to produce carelessness of the happiness of animal life everywhere. I do not mean to say that a man who would needlessly crush a fly would therefore slay a man; but I do mean to say that that moral constitution out of which springs kindness is hindered by that which wantonly destroys happiness anywhere. Men make the beasts of burden, that minister to life and comfort, the objects, frequently, of attention that distresses them, or of neglect that is more cruel. And I hold that a man who wantonly would destroy insect life, or would destroy the comfort of the animal that serves him, is prepared to be inhuman toward the lower forms of human life. The inhumanity of man to animals has become shocking. I scarcely pass through the streets of Brooklyn or New York, that I do not behold monstrous and wanton cruelty. There are things done to animals that should send a man to prison every day of our lives. And it is high time that there should be associations formed here to maintain decency and kindness toward the brute creation, as there have been formed in Paris and London, and almost all civilized countries except our own. Cruelty to animals tends to cruelty to men. The fact is, that all those invasions of life and happiness which are educating men to an indulgence of their passions, to a disregard of God’s work, to a low and base view of creation, to a love of destructiveness, and to a disposition that carries with it cruelty and suffering, and that is hindered from breaking out only by fear and selfishness, lead to a disregard of labor and the laborer. The nature which they beget will catch man in his sharp necessities, and mercilessly coerce him to the benefit of the strong and the spoiling of the weak. And it is the interest of the poor man, and the oppressed man, that there should be a Christianity that shall teach men to regard the whole animated kingdom below themselves as God’s kingdom, and as having rights—minor and lower rights, but rights—before God and before man.”

“You see, boys,” continued Uncle Benny, “what a really good man thinks and says on this subject, and I trust you will remember, hereafter, that all God’s creatures have as perfect a right to live in his world as you have.”

There was a peculiarity of Uncle Benny’s mode of correcting the bad habits of the boys,—he was careful to avoid a continual fault-finding. His idea was that rebukes should always be couched in soft words, but fortified with hard arguments, and that, to make censure most effectual, it should be mixed with a little praise, whenever it was possible to smuggle it in.

Somebody has said that, “when a fault is discovered, it is well to look up a virtue to keep it company.” This was Uncle Benny’s view of things. In fact, he was generally as careful to express approbation of good behavior as disapprobation of that which was bad. He believed that any one could do a casual act of good-nature, but that a continuation of such acts showed good nature to be a part of the temperament, and that even a temper or disposition which was naturally sweet and equable might be soured and made morose and petulant by incessant fault-finding.

Hence he never was guilty of a regular scolding, but preferred persuasion, with an effort to convince the judgment by argument, and illustrations drawn from facts so plain that they could not be denied. His practice was thus found to be so different from the discipline of their father’s kitchen, that they bore any amount of the old man’s pleading and argumentation without ever becoming ruffled in temper or tired of listening. But his frequent readings were probably the most popular part of the many discourses he felt called upon to deliver to them.

When this last one was finished, they all got down from the worm fence and continued their way. It had been an eventful afternoon for the boys. They were continually speaking of the novelties they had seen, and wondered how it happened they had never known of them until now, though living only two miles away, and resolved not only to go again, whenever they had time, but to get Uncle Benny to take them to some other farms in the neighborhood, that they might see what was going on there also. They felt that they had learned much from this single visit, and presumed that visiting in a wider circle would be equally instructive.

Uncle Benny said, in reply to this, that he was glad to see they were thinking so sensibly, and to find that their curiosity had been sharpened. He would gratify it as far as might be within his power. He told them the way to acquire knowledge was to go in search of it, as neither knowledge nor profit came to a man except as the result of some form of effort to obtain it. He explained to them that it was for the purpose of disseminating knowledge among farmers that agricultural fairs were annually held all over the country. They had never attended any, but he would tell them that they were great gatherings of farmers and others who had something to exhibit or to sell. Thousands of people attended these fairs, some for amusement only, but hundreds came to see if any new or improved machine was on exhibition, or a better stock of cows, or sheep, or pigs, or fowls, or a fine horse, or any superior variety of fruit or vegetables. If they saw what pleased them, they were pretty sure to buy it. At any rate, they did not fail to learn something valuable, even if they made no purchase. They saw, gathered up in a small compass, what was going on in the farmer’s world, and this within a single day or two. Thus they accumulated a fund of knowledge which they could not have acquired had they remained at home.

On the other hand, these county fairs were quite as advantageous to the parties who thus brought their machines, or stock, or vegetables to be exhibited. Many of them manufactured the machines to sell, and so brought them where they knew there would be a crowd of farmers in attendance. It was just so with other articles exhibited. There were customers for everything on the ground. Even those who came to make sales were benefited in other ways. They made new and profitable acquaintances. This gave them a knowledge of men which they could not have acquired had they not gone to the fair in search of it. Thus there was an extensive interchange of information and ideas between man and man, for no one could be expected to know everything. Hence such gatherings as these county fairs were highly beneficial to the farming and manufacturing community; and it might be set down as a good rule, that a farmer who felt so little interest in his business as never to attend an agricultural fair would commonly be found far in the background as regarded progress and improvement.

“Couldn’t you take us to a fair, Uncle Benny?” inquired Tony.

“Certainly,” replied the old man, “if we can get permission.”

“And won’t we take Nancy and the pigs?” demanded Bill.

“Yes,” interrupted Tony; “somebody will buy them and give a good price.”

“Sell Nancy?” demanded Bill, with a fire unusual to him. “You sha’n’t do it. I won’t have Nancy sold.”

“Well, never mind Nancy,” responded Tony, “we’ll take the pigs and the pigeons.”

“Not all of them, anyhow,” replied Bill, almost beginning to cry at the mere mention of letting Nancy go, while the dispute went on in so animated a style as to fairly startle the old man.

“Stop, boys,” he interposed. “There is time enough for all this. There is no hurry about the matter. The fair will not be held for several months yet, and you don’t know whether Mr. Spangler will let us go. Wait a little longer, and I will settle this thing for you.”

The mere suggestion of their not being permitted to go to the fair was an effectual check to this unusual effervescence, and the whole party relapsed into silence. But from this they were presently roused by the near approach of a traveller, whom they had noticed for some time in the road before them. No one appeared to recognize him; but when he came within hailing distance of the company he took off an old cap, waved it over his head, and shouted, “Hurrah! Uncle Benny! Back again to Jersey!”

The party were taken by surprise, but when the speaker came close up to them they saw who he was.

“Why, that’s Frank Smith, sure enough! I didn’t know him,” exclaimed Joe Spangler; and then there was a crowding up to him and a general recognition and shaking of hands.

“Why, Frank,” said Uncle Benny, “we’re glad to see you. Did you say you’d come back to Jersey? But what’s the matter? What’s brought you back?”

“Got enough of New York,—sick of the dirty place, and never want to see it again,” he replied. “Put me among the Allens once more, and blame me if you ever catch me quitting the farm as long as I live. I’m pretty near to it now. How nice it looks! Tony, don’t you ever think of going to New York.”

Here was a most unexpected conclusion to their afternoon’s diversion. The boy before them, Frank Smith, was a lad of fifteen, an active, intelligent, ambitious fellow, an orphan nephew of Mr. Allen, who had been taken by his uncle, when only ten years old, to be brought up as a farmer. He had been clothed and educated as his cousins, but for two or three years his mind had been bent on trying his fortune in the great city. No persuasion could wean him from his darling project, and becoming restless and dispirited under what he considered the monotonous routine of the farm, Mr. Allen finally yielded to his importunities, and permitted him, the Christmas previous, to try for himself how much better he could succeed in New York. He fitted him out respectably, paid his fare on the railroad, and gave him a little purse of money with which to keep him clear of actual suffering until some profitable employment should offer. Thus equipped, he plunged into the great city, having learned no trade but that of farming, with only a general idea of what he was to do, and without a solitary acquaintance among the thousands who were already fighting the battle of life within its densely crowded thoroughfares.

He had been gone for months; but in all that time he had written but one or two letters home, and they said nothing that was encouraging, though they contained no complaints. The last one did say, however, that he wouldn’t mind being back on the farm. It was clear, thought Mr. Allen, that he had been disappointed, and was not doing much. But as Frank had been told, when leaving home, that he was welcome to return whenever he had enough of the city, no pressing invitation was sent, in reply, for him to come back. It was thought best to let him sow all his wild oats at once. His pride being strong, he could not bring himself to the mortifying position of admitting, by turning about and coming home, that he had committed a grave mistake, until driven to it by absolute suffering. So he held out until holding out longer became dangerous, and there he stood in the highway, like a prodigal son returning to the parental household.

He went away with new clothes, clean linen, and a robust frame. He was now shabby, dirty, ragged, and his features indicated slender rations of food. It was this changed appearance that prevented the boys from recognizing their old friend until he was close upon them. He had travelled all the way from New York on foot, yet his step grew lighter and more elastic the nearer he came to his old home. Of course there was a world of questions as to how he liked New York, what he had been doing there, whether he made any money, why he came back, and every other conceivable topic of inquiry that could suddenly occur to the minds of three raw country boys.

Frank was in no hurry to leave his friends for home, as it was now in sight, and he felt himself already there. Neither did he seem at all unwilling to give them as much as he then could of his adventures in the city, and so replied to their numerous inquiries as fully as he was able to. He was a frank, open-hearted fellow, without a particle of false pride about him, and so admitted from the beginning that he had made the greatest mistake of his life in insisting upon leaving the farm. He even called himself a great fool for having done so. But after all, he thought it might be a good thing that he had made the trial, as it taught him many things that he never would have believed possible unless he had gone through them for himself, and was a lesson that would be useful to him as long as he lived.

Though in reality he had but little to tell that would interest older folks, yet to the boys his story was particularly attractive. Going into a great city with no friends, but little money, and without a trade, he could find nothing but chance jobs to do. The merchants and shopkeepers refused to employ him, because he was a stranger, with none to recommend him for honesty. When they found he was fresh from a farm, some said at once he was not the boy for them,—they wanted one who knew something. Others advised him to go home as quickly as he could, but not one offered to help him. He occasionally picked up a shilling by working along the wharves, but it was among a low, vicious, and profane set of men and boys, with whom it was very hard for him to be compelled to associate. Then he tried being a newsboy, bought papers at the printing-offices and sold them about the streets and hotels, and other public places. But here he met with so many rebuffs, and was so often caught with a pile of unsold papers on his hands, that he found the business paid him no certain profit. The city boys seemed sharper and quicker, and invariably did better, some of them even saving money, and helping to support their aged or sick parents.

He went through a variety of other experiences that were very trying to a boy of his spirit, but, though exerting himself to the utmost, he made no encouraging headway. One of his greatest trials was being compelled to associate with a low, swearing, drinking class of people, and to live in mean and comfortless boarding-houses because they were cheap. He never had a dollar to spare or to lay up. It required all he could make to keep him alive. As his clothes became worn and ragged, he was not able to obtain better ones. Still, he was too proud to write home what he was undergoing, as he knew he had brought it on himself, and that it was exactly what his uncle had said would be likely to overtake him. Yet he was conscious of gradually becoming reconciled to the low and immoral set around him, so different from those among whom he had been brought up.

One day, when in company with some of his associates, newsboys and bootblacks, Frank saw a gentleman drop his pocket-book on the pavement. He ran instantly and picked it up, and was about following the loser to restore it to him, when his comrades stopped him, telling him he should do no such thing,—that they had a share in it, as they were with him, and he must divide the money with them. The bare idea of stealing had never before crossed Frank’s mind; but now that it was suggested, with the property of another actually in his hands, which he could appropriate without fear of discovery, he felt the temptation to steal it come over his thoughts. But it was only for a moment. The early teachings of a virtuous home were not to be thus suddenly forgotten. Breaking away from his dishonest companions, he ran after the gentleman and restored him the pocket-book, and was soundly abused by the others for doing so.

But Frank was so thoroughly alarmed by feeling that he had thus been tempted to become a thief, and so fearful that, if he continued to associate with thieves, he would soon become one, that he resolved not to stay another day in New York. Even if he had had a hard time there, his integrity was yet sound, his conscience clear, and he meant to keep it so. As he owned nothing but the old clothes in which he stood, it was an easy matter to leave the city; so the next morning he started for home, with a few crackers in one pocket and a huge sausage in the other, but with the light heart of youth, made lighter still by the consciousness that strength had been mercifully given him to overcome a strong temptation. It was a two days’ tramp even for his active limbs, but he went on joyously, and was never in better spirits than when he encountered the Spangler party in the road.

“But wouldn’t you have got rich if you had stayed longer?” inquired Tony. “A great many poor boys in New York have become rich men.”

“I don’t believe it, Tony King,” replied Frank. “Where there’s one who gets rich, there are twenty that go to the dogs,—that get drunk, or lie and steal, or sleep in boxes and hogsheads in the streets, and turn out vagabonds. I thought just as you think, that all the poor boys make money, and wouldn’t believe my uncle when he told me that life in the city was the worst lottery in the world. But I’ve found it just as he said, only enough worse. Now, Tony, you want to go to the city, I know you do: you and I talked it over before I went, and you want to go now. But if you don’t stay where you are, you’re a bigger fool than I was. You’ll never catch me again leaving the farm to cry newspapers and black boots in the streets. I’m made for something better than that.”

With this sensible admonition Frank bade his friends good by, and started off on a half-run for his uncle’s house, as if impatient for the surprise which he knew his sudden appearance would occasion among the family. Uncle Benny was not sorry that his three boys had received the full benefit of Frank’s experience of city life, nor could he regret the tattered dress in which he had presented himself before them, as, if it were possible for eloquence to be found in rags, every one that hung about him became a persuasive witness to the truth of the experience he had related.

Author of “Ten Acres Enough.”

The black-fish in the tanks of the Leopold were all alive and kicking when she came to anchor in Rearport harbor. The schooner had been reported as seen at the port where she had lain for two days, and Mrs. Brindley had been saved from forty-eight hours of anguish. Tom sold the fish to a man who purchased for the New York market, and when they were transferred from the Leopold to the vessel in which they were to depart for New York, people said that Tom Brindley was a smart fellow, without knowing anything about the golden treasures concealed in the cabin of the Pinkey.

The enterprising skipper of the Leopold had bound his crew by a solemn promise not to say a word about the money they had made until after the twentieth of the month. He had made a little plan to astonish the lordly Captain Bellmore by paying off the mortgage and interest, when he came to demand possession of the cottage. He was determined to convince the magnate of Rearport that he was not a good-for-nothing, and he looked forward with the most exciting anticipations to the twentieth day of the month. He did not even tell his mother of his surprising good fortune, but carefully deposited the sovereigns, which, at $4.88 each, formed his worldly wealth, in a closet in his attic chamber, where they would be available when the great day of retribution should arrive.

The twentieth day of the month arrived, and with it the portly form of Captain Bellmore. He was as lordly and magnificent as when he had called before. He tried to look meek and patient under the great wrongs which he had been called upon to endure for the sake of the Brindley family, though he could not help occasionally casting a hard, cold look of intense disgust at the author of his son’s misfortunes. As he looked at Mrs. Brindley, no doubt he felt what a solemn and disagreeable duty he was called upon to perform, for it must be exceedingly trying to the nerves of a rich man to be compelled to turn a widow, with a brood of young children, out of house and home.

The widow had a fountain of tears at her command, upon which it was her habit to make large drafts on occasions like the present. As the most natural thing in the world for her, she began to cry as soon as she saw the great man of Rearport. She hoped her tears would not be in vain, but would bolster up the modest proposition which she intended to make. She had talked a great deal with Tom about the momentous event which had now sadly dawned upon them, and begged him not to be “sassy on no account whatsomever,” for that would spoil all her plans. Tom kept his own counsel, and promised not to be “sassy” if Captain Bellmore treated him decently.

The young pilot sat sideways on the end of the sink when the rich man entered. He looked easy and defiant, and his poor mother’s heart sank within her as she glanced at his self-assured and even impudent look. She was satisfied that the Captain would reject her offers and drive her from the house, all because Tom looked so “sassy.”

“Well, Mrs. Brindley,” began the strong man of Rearport, “I have called to see you as I promised.”

“Yes, Cap’n—thank’e—I’m much obleeged to ye for comin’,” replied Mrs. Brindley, determined, if soft words would accomplish anything, that they should not be wanting.

“I hope you are ready for me,” added the Captain.

We must record our solemn protest against this remark, for it was a downright lie! He did not hope she was ready; on the contrary, he hoped and believed she was not ready; and he was confident that he should be able to take the first step towards bringing Tom “under.” The whole family must go to the poor-house, where Tom would come within his grasp, as chairman of the Board of Overseers.

“I’m not exactly ready, but I can pay you something. I’ll let you have the back interest to-day, and in a few—”

“That won’t do, Mrs. Brindley,” interposed the Captain, decidedly, as he glanced at Tom, who sat swinging his right leg against the side of the sink. “I must have the principal and interest.”

“I did hope you wouldn’t be hard on a poor body,” said she, thrown all aback by the prompt answer of the creditor. “I’ve raked together what money I could, and I did hope you’d let us stay here for a while longer.”

“My duty to myself and my family”—Captain Bellmore glanced at Tom again—“compels me to be firm in this matter. I don’t like to do it, but I don’t see how I can do anything else. The fact of it is, marm, your son there has spoiled all my calculations in your favor.”

“Thomas has behaved better since you was here last. He has worked well, and minds me in everything I say.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” replied the Captain, uttering another abominable falsehood.

“He’s doin’ so well, if you’ve a mind to let us go on a while longer, I think we can pay the rest of the interest in a few weeks.”

“I should be very glad to do anything I can for you, but your boy treated Richard so badly, that I don’t feel called upon to do anything different. I know it comes hard to you.”

“Dreadful hard, Cap’n,” said the widow, as she thought she saw some signs of relenting on the part of the great man.

“I don’t know but that we might fix it,” said the Captain, after a hopeful pause.

“Anything in natur that we can do!” continued Mrs. Brindley, briskly, as her hope began to enlarge.

“If your boy will beg Richard’s pardon for what he did, I’ll try and see what can be done.”

“I’ll do it, Captain, if Dick will beg pardon of Jenny Bass for what he did agin her,” replied Tom, promptly.

“I knew he would!” exclaimed the delighted widow, not clearly comprehending the condition on which the concession was to be made.

“Richard shall do nothing of the kind,” said the rich man, sternly.

“ ’Cause if Jenny will forgive Dick, I’m willin’ Dick should forgive me,” added Tom, with easy good-nature.

“Did you think my son would apologize to that dirty Bass girl?” demanded the Captain, horrified at the suggestion.

“Well, no; I didn’t think he would, no more’n I’d apologize to Dick for serving him just as he deserved.”

“What do you mean by talking to me in that way, you young villain?” roared the hard creditor.

“Well, Cap’n, if I’m a young villain, you’re an old one, and got further into’t than I have.”

“Don’t, Thomas, don’t!” pleaded Mrs. Brindley. “For pity’s sake, don’t!”

“You hear, marm?” gasped Captain Bellmore.

“You needn’t talk to me, Cap’n,” added Tom, shaking his head. “I know you better’n you know yourself, and you needn’t think you’re goin’ to wipe me out like a chalk-mark. I know what’s what as well as you do.”

“What do you mean, you young scoundrel?” stormed the Captain, who never, since the world began, heard of a boy using such language to the rich man of Rearport. “Do you know who I am?”

“I calculate I do; you’re the meanest man in Rearport, I don’t care where you look for t’other.”

“There, marm, you hear that boy!” gasped the creditor. “What can I do for you now?”

“For mercy’s sake, Thomas, don’t be so sassy.”

“He’s sassier’n I am,” answered Tom.

“That’ll do!” said Captain Bellmore, who had no idea how it was possible for a gentleman like himself to be saucy to the good-for-nothing son of a fisherman’s widow. “Now, you young rascal, I’m going away, and I shall turn you out of the house right off.”

“No, you won’t!” replied Tom, easily.

“Won’t I?” hissed the Captain.

“No, you won’t!”

“You shall see, you young rascal! You shall see!”

“I’m willin’ to do what’s fair and right.”

“Pay your father’s note, then!”

“How much is it?”

“How much is it! Four hundred and forty-eight dollars!” replied Captain Bellmore, measuring off the words very slowly, that the full magnitude of the sum might be appreciated. “Pay it, if you want to keep out of the poor-house!”

“I guess I will, Cap’n,” said Tom, sliding down from the end of the sink and walking towards the table in the middle of the kitchen floor.

“You guess you will!” sneered the creditor, who began to think that the boy was crazy.

“I guess I will, Cap’n,” added Tom, as he thrust his hand into his trousers pocket, and drew forth a handful of the sovereigns he had received from the captain of the Imperial, and slapped them down rather emphatically upon the table.

“My stars!” exclaimed Mrs. Brindley. “Where did you git all that money?”

“I can afford to be sassy, can’t I, mother?” said Tom, with a smile, as he drew forth another handful of the glittering coins, whose weight had nearly parted his suspenders.

Captain Bellmore was astonished, astounded, confounded, dumfounded,—amazed, bewildered, overwhelmed. He could not speak for some time; and when he could, he intimated a suspicion that somebody in the neighborhood had been robbed.

“See here, Captain Bellmore, I’m goin’ to pay you all up; and I don’t want none of your words. If you call me any more names, I’ll turn you out of the house,” interposed Tom.

“Where did you get all that money?”

“Well, it’s none of your business, but I don’t mind tellin’ you. I got a steamer off the Gridiron Shoal, and piloted her into deep water just afore the gale come on. That’s where I got the money.”

“That’s how you happened to be clear down to Bangsport?” said Mrs. Brindley.

“That’s just how, mother.”

“Why didn’t you tell a body on’t?”

“ ’Cause I wanted to see things take their nateral course. Now, Cap’n Bellmore, I’m ready to pay up,” said Tom, turning to the amazed and indignant creditor, who had saved his debt, and got cheated out of his revenge.

The Captain performed the problem in exchange which the British currency on the table suggested. He was gloomy and sullen, and made some mistakes in his arithmetic, which Tom corrected, for Si Ryder, who was a pretty good scholar, had figured out the sum for him. The business was closed, much to the disgust of the Captain, but entirely to the satisfaction of the rest of the party, including the small children, who had stood with mouths agape during the entire scene.

Captain Bellmore left. Mrs. Brindley danced around the kitchen like a lunatic when Tom showed her the rest of the gold. Two hours of steady talking explained the past, and foreshadowed the future. It was decided to put the rest of the money out at interest, reserving only a small sum to pay for some necessary repairs on the Leopold, with which Tom intended to follow up the fishing business.

The story of the young pilot flew through the village, and Tom was a lion. Bob Barkley was justified. Even Joe Bass and Si Ryder were second-class lions. The conclusion was unanimously reached that the boys were not good-for-nothings.

Tom Brindley kept his good resolutions. He became the man of the house at home. He worked well at his business, and was successful. When the winter came, the fact that he had not been able of himself to change pounds to dollars induced him to go to school. He studied faithfully, and, though learning was not exactly his forte, he obtained a fair education in time. He is now twenty-two, and is a steady, industrious fisherman; not intellectually brilliant, but bold, dashing, serviceable in any emergency. His mother still lives, and thinks that Tom is a greater man than ever Captain Bellmore was. Tom was married last Thanksgiving to Jenny Bass, and as this catastrophe seems to be a proper stopping-place for our story, we will leave Mr. Brindley to finish working out the fortunes of a good-for-nothing without our assistance.

Oliver Optic.

Roaring Run ravine is a deep hollow between two mountains, through which pours a brook, tumbling helter-skelter over the great gray rocks till it gets out of sight in a dark forest; and at the time of which I am thinking there stood only a few pine-trees off from the edge of the ravine, and an old house, or rather its shell, for the stairways were crumbling in pieces and the plaster dropping from the walls, the windows were out, the fences were gone, the chimneys had tumbled down, the spiders had hung all the mouldy old rooms with their spinning, and the rats scampered impudently about in the halls. In the winter the snow whirled in at the open windows and piled itself in great drifts on the rotting floors, the rain dripped through the broken roof, the wind blew through the crazy building as if it had been a sieve, and it was altogether a shivering, wheezy, shaky, dismal old den, not fit for an eagle’s nest; yet two children, Yolande and Harold, lived there, because they were too poor to live anywhere else, and all day long, and often far on in the night, Yolande spun wool and flax, and Harold, who was a cripple, and could not stir from his bed, lay near the hearth and watched her.

The coldest day in the winter had come. The road and ravine looked as if candied in ice. The north wind whuddered about the windows, and blew pins and needles of frost through the chinks, that made Yolande sting and ache all over, and shook the doors as if trying to burst them open, and yelled down the chimney, “Oho! call that a fire, do you! I could make a better one of icicles”;—for Yolande was her own wood-sawyer, and, being small and weak, could only chop off bits here and there of the great pine trunks with her hatchet; and the fire was smoking in a very miserable way, as if it was out of spirits at having to burn flat on the old hearth, without any firedogs, and when at dark Yolande boiled the meal for their supper, it fell into such a low frame of mind that it very nearly went out altogether. “O, this won’t do!” said Yolande; and looking about her for something to split up, she spied an old chair, with a high back perfectly straight, with queer little knobs and lines and balls all over it, that stood grimly in the corner as if it were thinking, “You would now, would you? Split me up for firewood, indeed!” At the first sound of her hatchet, the spiders, every spider of them, grew stiff with horror in the midst of their webs, saying, “Did you ever! A respectable old chair, that has been of no earthly use to anybody for the last forty years, to be degraded in this way!” And the rats answered darkly from their holes, “She would sooner have frozen to death, if she had proper feeling.” And a lot of beetles held a spirited meeting out in the hall, declaring that this sort of thing must be stopped. But the fire blazed up merrily, and Harold put out his little thin hands from his bed, and said, “Ah! that is nice; and the meal was nice, too,—almost as good as beefsteak; and if my feet were only warm, I think I could go to sleep.”

Yolande took off her only woollen skirt and wrapped it about his feet, and, as he had said, he fell fast asleep. The balls, and the carvings, and the twisted legs, and even the grim back of the chair, crackled, and sent out flashes of flame and heat, and Yolande went to and fro in the dim light, turning the great wheel, and drawing out the long loops of wool, but slowly; because it was hard work to drag about feet that could neither bend nor feel; and because it was getting so numb at her heart, and so heavy at her head; and because the tingling and pricking of her skin and the ache in her fingers were all gone, and she wanted to sleep; and because she was spinning now, not wool, but a woollen blanket for Harold, and a feather-bed for herself,—she slept on the floor,—and flannel skirts, and yarn stockings, and shawls, and pillows, and everything that ever was warm and comfortable; and because the great wheel turned slower and slower, as was quite natural when it was bringing forth such prodigious things; and because the distaff had dropped from her hand, and she was down on the floor beside the wheel—asleep.

The fire, that had burned away almost to ashes, made one last leap up the chimney, and called loudly out to the pines, “You there! stop your creaking, and listen to me. Here is a little girl freezing to death, and I am going out, and can’t stop myself.”

And the pines groaned over it in their solemn way, yet never stirred a leaf to help; but the Wind, and the Snow Goblin clumping along the road just then in his great wooden shoes, and the Roaring Run down in its ravine, heard what the fire said to the pines.

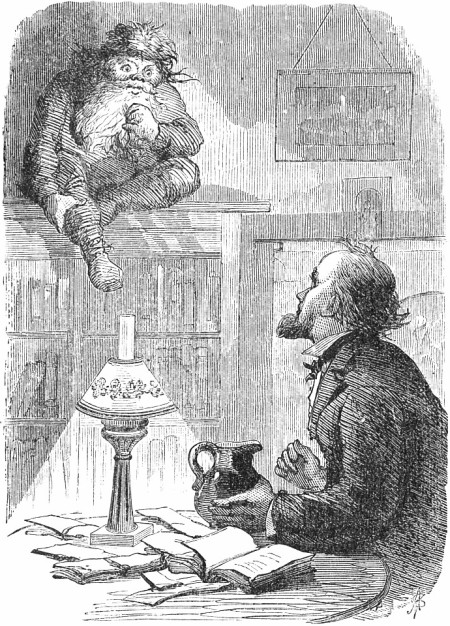

The lawyer’s house stood in the village at the foot of the mountain, and that night the lawyer sat by the fire in his cosey study, warm to the very core with the jolly blaze on his hearth, and an occasional sip from the pitcher of ale that stood beside him. He was studying a very profound book, as lawyers always do in all their spare moments, and was at the fourth paragraph on the sixty-third page. The windows were all closed, the door was shut, the bell didn’t ring, and yet—there—certainly—was—a person in his study; a large, fat, red person, with a bushy beard, and the queerest voice in the world; for one moment he was squeaking like a fife, the next he was growling down in the bass, and a third sent him off in all kinds of little shakes and turns and trills. His legs too were as shaky as his voice. He was turning somersaults, and pirouetting, and sliding, and rushing into corners, and whizzing up and down the chimney, doing everything in the world but sit or stand still, while his breath, as he danced about the room, sent a stream of chills down the lawyer’s warm back, and the thermometer hanging by the door down to zero.

The lawyer stared, and rubbed his eyes, and stared again; and as lawyers, you know, always argue about everything, he said to himself, “This is a dream, because a big red-faced man like that couldn’t come in through the key-hole,—that would be preposterous; and since it is a dream, I had better wake up, because dreams that pop up and down your chimneys, and then put their heads on one side, and wink at you, are not pleasant.” But finding that, no matter how he rubbed his eyes, or opened or shut them, here was the pitcher of ale, and there were the book-shelves, and as fast as either of them stood red-face before the fire, still winking at him, he began to argue again, “If this is not a dream, it must be a man, though it is very odd how he got in here; but since it is a man, what can he want?” But though paragraph number four, on the sixty-third page, was a very deep paragraph no doubt, it was not deep enough to tell the lawyer that; and red-face had just taken a run up the book-shelves, and sat there on the top of them, with his legs dangling, which put the lawyer so entirely out of countenance that he could not ask him; and strangely enough, in the midst of his perplexity, he began to think of the old house at Roaring Run, and the longer he looked at the red-faced man, the more he wondered what had become of the two children there in this bitter weather.

“They are freezing to death, thank you,” said his visitor, precisely as if the lawyer had spoken his thought aloud; “and if you should put the truth over their graves, which you won’t, of course, you would write, ‘Died of the squire, the doctor, and the lawyer, who kept their own folds warm and comfortable, and left these stray lambs out in the cold to perish; because the doctor thought it was the squire’s business, and the squire thought it was your business, and you thought it was the minister’s business, and so nobody made it his business, though you knew that, all the time, they needed to eat, sleep, and be warm, just like people who have houses to do such things in.’ Hurricanes and tornadoes! as surely as my name is the North Wind, I have not frozen anybody to death in the last hundred and fifty years with half the pleasure that I shall freeze you to-night; and I have done a number of such little jobs in my time.”

“This is some madman escaped from the asylum,” thought the lawyer. “I will slip out of the room, and call for help”;—and being very clever, he set about it shrewdly. You see, a stupid man would have bolted for the door outright; but first he yawned, and then he rose from his chair as if to stretch himself, and then he edged out a step or two from behind the table, when “Oho!” said the Wind, “that is your game, is it?” and with a single puff blew him back in his chair, like a feather, and at the same moment the lawyer’s conscience, wherever it came from, popped out, and tied him in it fast.

“You need not think in your heart about the squire and the doctor,” said his conscience; “they will be looked after in their turn, and because they are black, you are none the whiter.”

“Now,” said the lawyer, “I couldn’t have dreamed this, for I don’t remember my conscience from one year to another; and it cannot really be here, because it is up stairs in the pocket of my Sunday coat, where I always keep it. I must be mad, after all,”—and, settling himself back in his chair, he resigned himself to his fate. The Wind blew upon the fire; it went out at the first puff. He blew down the lawyer’s back, he breathed on the lawyer’s legs, he nipped his toes, he pinched his ears, he tweaked his nose, when luckily came in the lawyer’s wife.

“Bless me!” cried she, “the fire all out, and you here fast asleep, and as cold as a stone, I declare!”

The lawyer jumped up in his chair. “Where is the Wind?—I mean the fellow that was freezing me to death—I mean——.” Here he got his eyes wide open, and saw there was no one in the study but his wife. At that he was so delighted that he actually turned a somersault, and cried, “Hurrah!” cutting a very funny figure in his dressing-gown and slippers, I assure you. Then he rang every bell in the house with all his might. All the servants came running.

“Get out the sleigh, and the horses, and a lot of blankets, and brandy, and beef-tea, and wood, and spoons, and forks, and the buffalo robes, and butter, and sugar, and pepper, and salt, and whatever you bring people that have been frozen to death to life with,” said the lawyer, “and be quick. I am going up the mountain, to the old house at the Roaring Run.”

Away flew all the servants, gabbling and getting in each other’s way. Away posted his wife after the doctor, to tell him that her husband had gone mad. The doctor had gone to bed; yet he got up at once, and came with the lawyer’s wife, and a long face, to look after the lawyer’s wits. But by that time the lawyer had straightened them out himself, and so the doctor put the blister that he had brought for the lawyer’s head in his pocket, and, getting into the sleigh, rode with him up the mountain, to see, I suppose, if he could use it on Yolande.

It happened that day that the squire had come for a walk up to the head of the ravine of the Roaring Run, and being a stout man, buttoned up to the chin in a warm overcoat, instead of a poor little half-starved girl in a calico dress, he found climbing and scrambling about in the keen air such famous sport, that the day was almost gone when he turned about to go home. Unluckily, he passed the spot where, about a mile below the falls, the path that led to the village came down to the edge of the brook; and though he went back and searched for it, and climbed up the rocks, and down the rocks, till it was nearly dark, he could not find it. The squire was in a mighty rage, for to follow the Roaring Run down its bed was to walk three times as far, to say nothing of the fact that the stones were as slippery as ice could make them. But while he was grumbling to himself, he spied a boy sitting on a rock, with his hat pulled over his nose, like Sam Hopper; and without stopping to think that people are not apt to sit out on rocks on such nipping nights as that, he called out, “I say, Sam, will you show me the best way home?”

“S’pose I can,” grumbled Sam.

“But will you do it, is the thing,” said the squire.

“P’raps you won’t like my way,” answered Sam. “I allers takes the rough ways. There, now, didn’t I tell you? There you go!”

What do you suppose the squire had done? Only stepped on a bit of thin ice, and tumbled sprawling into the black water, that splashed about him as if it laughed. The stream was deep and strong. It sucked him under and held him fast. It soaked him through in a moment; it made his boots as heavy as lead, and his blood like ice. When he got up, you never saw such a figure! He was dripping from his hat, and his hair, and his nose, and his whiskers, and his coat; he was shivering from his head to his toes; he was spluttering, for the water in his nose and mouth would not let him talk; and he was the very most angry man that ever got a ducking. The boy went on before him chuckling, and, though water of course never giggles, it plashed on the stones in a way that sounded curiously like it. Even the grim old pines, that had seen the whole from the sides of the ravine, followed the squire with a windy guffaw. But let laugh who would, that unlucky man had quite enough to do to mind his own business; for first he slipped down on his back, and then he tumbled on his nose, and a rock gave him a poke in the side, and the skin was off his knee, and there was a hole in his trousers, and a stone bruised his pet corn, and he was quite fagged out of breath, and worst of all, the moon, breaking through a cloud, showed him the waterfall where the Roaring Run pours over the head of the ravine. That wicked Sam had led him back to the place from which he started, two hours ago.

“You young villain!” roared the squire, flourishing his stick in one hand, and making a grasp at Sam with the other; but the boy slipped through his fingers, and, with a whisk and a whirl like a scrap of flying mist, there sat his guide half-way up the waterfall, his big red tongue lolling out of the great mouth that he opened wide to laugh, and his little black eyes twinkling maliciously.

“Good evening, Squire,” said the figure, “and good luck to you in finding your way home; and the next time that you want a guide like me, ask for the Goblin of the Roaring Run.”

How the squire got back to the little path that he had missed in the twilight, he himself never knew; get there he did somehow, however, and lay groaning by the road, till, a wagon coming past, the driver came to his relief; but it was so dark that the squire could see nothing, except that he was a stout man in a white frock, and that the horses, pawing the ground impatiently, were as white as snow. The carter helped him into his wagon and started at a tremendous pace, and no sooner were they off than it began to snow; such snow!—it was so thick that it actually seemed to fly from the man’s white frock, and the horses, as they plunged furiously onwards, looked like driving clouds. The wagon bumped, and bounded, and jumped from one side of the rough road to the other, throwing the squire about like a bag of meal. On one side was a great mountain, on the other a dreadful ravine, going down, down several hundred feet, rough with rocks and pines, and at its bottom, dimly showing, the Roaring Run. The squire looked about him in astonishment, for they were not on the road to the village, but going up the mountain with the speed of an express train. The driver cracked his whip and shouted. The horses seemed to fly. The road narrowed and crumbled away, till the wagon-wheels ran on the very edge of the precipice.

Just then commenced behind them a terrible clattering; for the lawyer and the doctor, coming along in their sleigh at a lively pace, turned up the mountain road just behind a man in a white frock, who drove a pair of white horses that reared and plunged furiously, and threatened to overturn his wagon at every step; and though the lawyer’s horses were quiet beasts enough, some mischief must have been abroad in the air, for from an even trot they fell into a hurried trot, and from a hurried trot they broke into a gallop, and, getting finally the bits between their teeth, burst into a run, and raced like mad after the wagon up the steep road. “Whoa!” shouted the lawyer, and “Whoa!” quavered the doctor; but they might as well have said, “Get up!” The crockery and tins bounced about in the bottom of the sleigh, and kept up a deafening clatter; the bundle of bedding, standing straight up in the back of the sleigh, burst open; a pillow flew out, and then a sheet, and a big “comfortable” tumbled down over the heads of the doctor and the lawyer.

While they were struggling to get out, they came to the narrowest and most dangerous part of the road, where a few months before a pedler had fallen off with his cart, and been dashed in pieces. “Murder!” screeched the lawyer, half suffocated in the “comfortable” that the doctor in his fright was holding down tight about them. “Fire! thieves! help! whoa! I say,” yelled the doctor. The squire, pitching helplessly about in the wagon, heard the shouting and clattering behind, and, looking down, saw the jagged rocks of the ravine, and the wagon toppling over them. He shut his eyes, and seized tight hold of the wagon-side, saying, “O, here we go! Good Lord deliver us!” Instantly the driver faced about and gave the squire three hearty thwacks over the shoulders, with the handle of his whip. The horses reared, the wagon tilted, and the squire rolled out, as if he had been a cheese, at the door of the old house at the Roaring Run. The doctor and the lawyer had by this time their heads out of the un-“comfortable,” and saw something tumble out of the wagon before them; the lawyer’s horses stopped short, the something picked itself up and began rubbing its legs; and getting a little closer, they recognized the squire. So here were the squire, the lawyer, and the doctor, all at the old house of the Roaring Run. The squire, the lawyer, and the doctor, being there, rapped on the door, and hallooed by turns, but the sough of the wind in the pines was their only answer. Then they did the next best thing,—opened the door and walked in. The place was silent, dark, and cold; nothing stirring but the spiders curling themselves up in corners, and the rats and beetles, that eyed the intruders with huge disgust. “Going to build another fire!” said they. “What is this world coming to?”

Yolande had fallen asleep feeling only that curious numbness all over her body which made her so sleepy she could not spin; but she woke aching till she cried for pain; and there was such a fire on the hearth that she thought she was dreaming it, and Harold lay by it smiling at her, and she was lying on a real bed, (she had to pinch it to make sure that she was not dreaming that too,) and around it stood the three grand gentlemen of the village, the squire, the lawyer, and the doctor, smiling also, but she fancied that she saw tears in their eyes at the same time. “And you are to lie down and be quiet now,” said the squire, “and when you are better I shall take you and Harold home to live with me.” And then Yolande was sure that she was dreaming, but, as it was too pleasant a dream to wake up from, she just shut her eyes and went comfortably to sleep.

“And what do you think of all this?” asked the fire of the pines.

“Oh!” creaked they, “we have seen much more wonderful things than that, and it would never have come about at all if we had not groaned.”

Louise E. Chollet.

True to his promise, Father Brighthopes set out one day to pay little Kate Orley’s mother a visit.

On the way he had to pass a bend in the river, where, in a broad, shining sheet, it came sweeping around through the meadows until the willows on its banks grew within half a stone’s throw of the road. Behind the willows he heard boys’ voices, accompanied by a splashing of oars, and saw the ripples of a boat’s wake stretching in oblique lines to the farther shore. But the boat itself he could not see.

He could hear, however, altogether too much. The boys were talking and laughing as they paddled along, evidently quite unconscious of the good old clergyman’s presence so near them; for such language was certainly not intended for his ears! It made his very heart ache with sorrow for those foolish, profane boys,—a sorrow rendered all the more poignant by the fact that he recognized one or two of the voices.

The boat passed on one way, and he walked on the other; the voices were lost in the distance; the ripples died on the shore, and the shining surface was smooth again; but the wounds his spirit had received did not close so readily. He was thinking of those boys, and of what he should say to them at their next meeting, as he drew near Mr. Orley’s house. It was a little yellow house close by the street, with nothing attractive about it but a few lilac-bushes; but they were in full bloom, delighting the eye and filling the air with fragrance.

“So it is with the least refined natures,” thought Father Brighthopes, all the sunshine of his spirit breaking forth again. “However rude and unbeautiful they may be, there is always a lowly lilac-bush, or a honeysuckle climbing the door of their hearts, to adorn their commonplace lives and sweeten the air around them.” For the sympathetic old clergyman had never yet known a person so hardened and depraved that there was not still, lurking somewhere in his nature, an imperishable root of tenderness or goodness, forever putting forth green leaves again as it was trampled upon.

Seeing at a distance, coming from the opposite direction, a little girl whom he thought he recognized, he walked on and met her. It was little Kate, with a basket on her arm, returning from her errands. The lonesome face brightened with pleasure at sight of him.

“Well, how have you been, my little girl?” he said, turning to walk back with her.