* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Life of John Graves Simcoe

Date of first publication: 1926

Author: William Renwick Riddell (1852-1946)

Date first posted: Feb. 20, 2017

Date last updated: Apr. 19, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20170223

This ebook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Mardi Desjardins, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

The Life of

John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe as a Young Man

(From an Oil Painting)

The Life of

John Graves Simcoe

First Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Upper Canada

1792-96

By

The Honourable William Renwick Riddell

LL.D., D.C.L., Etc.

Justice of the Supreme Court of Ontario

Fortunatus et ille deos qui novit indigenas

McCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED

PUBLISHERS TORONTO

Copyright, Canada, 1926

by McClelland & Stewart, Limited, Toronto

Printed in Canada

To the Memory of

JOHN ROSS ROBERTSON

OF TORONTO

A Canadian who loved his country, a Journalist who loved his

profession, a Mason who loved his order, a Man

who loved his fellowmen,

This Life of John Graves Simcoe

Is Dedicated

by his friend for many years

The Author.

This work would not have appeared—at least in its present form—but for the diligent and successful researches of the late John Ross Robertson. My own investigations, pursued for some years, into the early history of Upper Canada, brought us together on many occasions. We found a common object of interest in John Graves Simcoe, our first Lieutenant-Governor. Mr. Robertson frequently urged me to write a life of Simcoe and I as often replied by urging him to do so. On almost the last interview we had, it was agreed that we should undertake the task together, he to write concerning Simcoe out of Canada and I concerning him in Canada. His lamented death prevented that project being carried into execution; but his son, Mr. Irving E. Robertson, has generously placed his collection of correspondence, &c., at my disposal that I might alone write what we had intended to write in association.

For the following pages I am alone responsible. Although the documents collected by Mr. Robertson have been utilized to the full, no use has been made of the chapters he wrote.

Much of the material is found in the Simcoe and Simcoe-Wolford Papers procured by the late Mr. Robertson; much collected by myself from the Canadian Archives and elsewhere, appears now in convenient form in three publications by the Ontario Historical Society—The Correspondence of Lieut.-Governor John Graves Simcoe, edited by Brigadier-General E. A. Cruickshank, LL.D., F.R.S.C. The Canadian Archives and those of Ontario with their many treasures, have been drawn on freely, as have the Parliamentary Library at Ottawa, the Reference Library at Toronto, the Riddell Canadian Library at Osgoode Hall, Toronto, and the Congressional Library at Washington. To those in charge of these institutions my sincere thanks are due and are here given for their unfailing courtesy and attention to what must have seemed at times almost unreasonable demands. Miss M. I. Sivers, who for years was closely in touch with Mr. Robertson and his work, has been of inestimable service in suggestion, criticism and correction.

While it is not to be expected that the following chapters are wholly without error, I have in practically every case given my authority, so that the error, if important enough, may be corrected.

Full credit has been given in the instances in which other accounts of Simcoe’s life have been quoted. I have in all cases gone to the original sources and owe nothing to any previous biographer.

No attempt has been made at fine writing: the facts of Simcoe’s life have been plainly stated and conjecture has been avoided.

The chapter on Simcoe as a Freemason has been added out of respect for Mr. Robertson’s well-known love of the Craft.

I venture to hope that the present work will do something to make Simcoe better known in his public and private career.

William Renwick Riddell.

Osgoode Hall, Toronto,

September 1926.

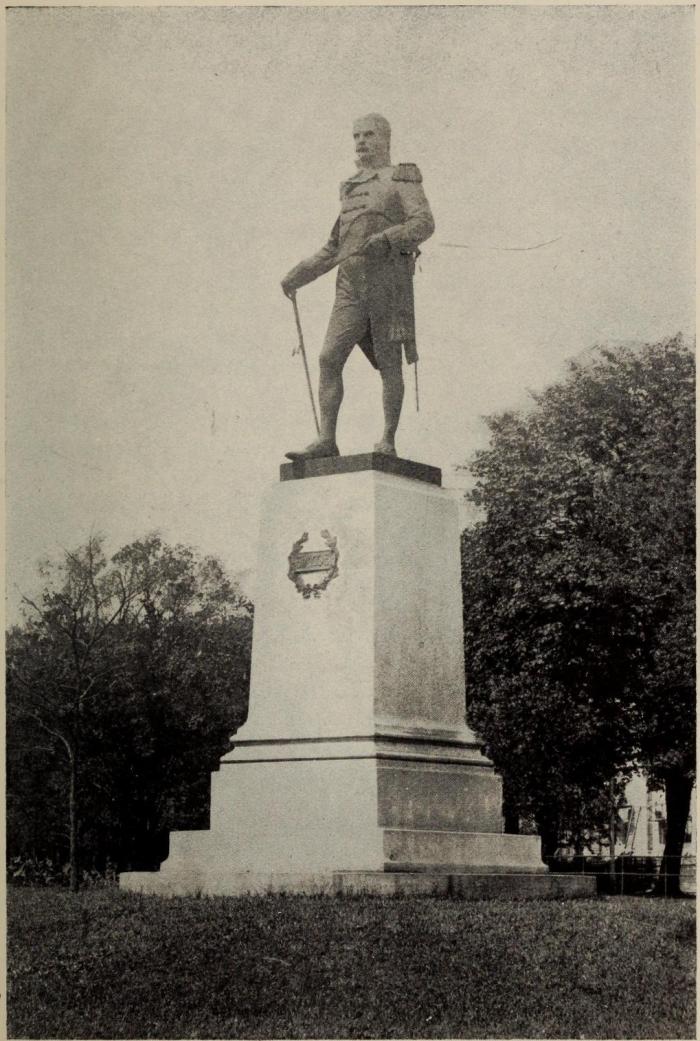

John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe who was to become the first Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Upper Canada, was born, February 25, 1752, at Cotterstock, a hamlet in Northamptonshire[1], about ten miles from Peterborough and a mile and a half from the old town of Oundle.

His father was Captain John Simcoe[2], whose ancestry has given trouble to some biographers; it may now be stated with certainty that he was the only son of the Reverend William Simcoe, Vicar of Woodhorn, Northumberland, who had been Curate of South Shields, Durham.

Born in 1710, John Simcoe was a man of the highest character, well read in the classics and general literature and specially skilled in mathematics. He obtained an appointment as Midshipman in the Royal Navy through the influence of his father in 1730: the name of the ship is unknown.

In 1737, he was appointed Lieutenant and in 1743, Captain. We find him in 1746 in command of H.M.S. Falmouth, employed about Jamaica in the unnecessary war with France which Pelham had declared in 1743; he was ordered by Vice-Admiral Thomas Davers of the Red Squadron, June 20, 1746, to take to England in his ship certain Spanish Privateers who had been captured by British ships in the Caribbean Sea[3]. He was placed in command of the second of the two divisions into which the home-bound fleet was divided, and arrived in due time at the Downs[4]. In the following year, 1747, we find him in command of H.M.S. Prince Edward in King Road, a roadstead in the estuary of the Severn[5]; and in the same year he was granted a coat of arms by the Garter and Clarencieux Kings of Arms—he was then described as of Chelsea, Middlesex.

In 1747, August 8, while still Commander of H.M.S. Prince Edward, he married Catherine Stamford; and after the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, settled in Cotterstock, where four sons were born to them, Pawlett William, John, John Graves and Percy William: the first and second died in infancy and the youngest was drowned in 1764. In 1749, he was involved in litigation arising out of his conduct as officer in the Navy; but he received the commendation of Chief Justice Willes at a trial at Guildhall[6]. He was an intimate friend of Samuel Graves, afterwards (1770) Vice-Admiral, and later (1778) Admiral; and the infant son received his second name in honour of this friend who became his godfather[7]. Simcoe hoped to be sent as Engineer in charge of the Forts and Settlements on the Coast of Africa, but the Committee of Merchants to whom was entrusted the choice selected another; he remained for a time in command of the Prince Edward, stationed at King Road, but in 1755 was looking for a command with little prospect of success; he applied to be permitted in case of war to serve as a volunteer with Sir Edward Hawke, and his request was granted by the Admiralty. But he almost immediately received the command of the St. George at Portsmouth—the Seven Years’ War, which broke out in 1756, demanded the services of all men so well qualified as John Simcoe. It was on board the St. George that the Court Martial for the trial of Admiral Byng was held, Simcoe being a member of the Court[8].

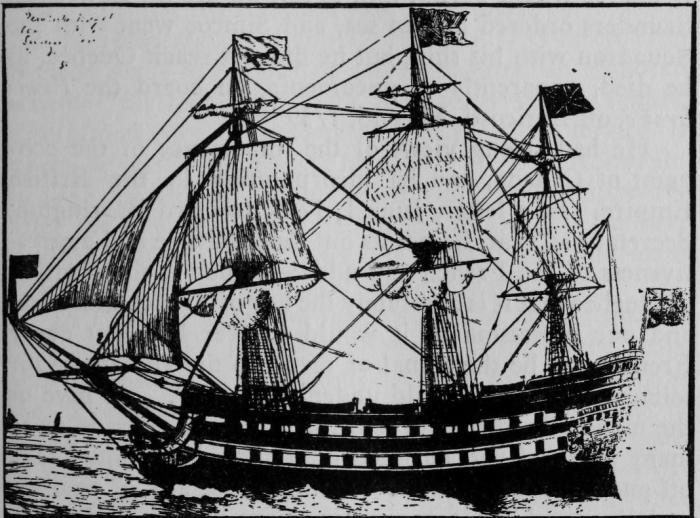

An expedition to North America being in prospect, Simcoe applied for and received the command of the Pembroke, a new 60-gun ship launched in April, 1757; he said that he had the seizure of Quebec so much at heart that he could “almost resolve to go as a volunteer”[9]. He was ordered by the Admiralty, November, 1757, to put himself in command of a number of ships and proceed with them and the Pembroke to join Sir Edward Hawke; he had sealed orders, but the Fleet was to join the Rochefort expedition, which proved unsuccessful.

H.M.S. Pembroke

From a Monument in St. Andrew’s Church, Cotterstock

The following year finds him at Halifax under the command of Admiral Edward Boscawen and later at Louisbourg, in the siege and capture of which he took part[10].

There has been some confusion as to the movements of Simcoe during the winter of 1758-9: it seems now clear that being on the Pembroke he was attached to Rear-Admiral Durell’s Squadron which wintered at Halifax.

This Squadron was intended to cruise off the mouth of the St. Lawrence, to block the entrance and cut off all aid from and intercourse with France. Durell, however, remained at Halifax and gave as an excuse when Wolfe and Saunders arrived, April 30, that he was waiting to hear if the ice would permit him to sail up the St. Lawrence. Saunders ordered him to sea, and Simcoe went with the Squadron with his ship, but he did not reach Quebec, as he died, apparently of pneumonia, on board the Pembroke, off Anticosti, May 15, 1759[11].

He had strong views of the importance of the conquest of Canada, and its incorporation in the British Empire. In a letter, June 1, 1755, to Lord Barrington, Secretary at War, he points out the insolence and aggressiveness of the French and adds:—“Such is the position of Quebec that it is absolutely the key of French America, and our possession of it would forever lock out every Frenchman, be the signal of revolt to the Indians—Our seizure of Canada would undeniably . . . . . . . give us the monopoly of the fur and fishery trades, open to us so many new and vast channels of commerce as would take off our every possible manufacture especially of woollen and linen, whilst it poured in every growth and every material at so cheap a rate as would make us necessarily the mart of foreign exportation and most amply compensate for even the extinction of all our other foreign trade of importation—a circumstance . . . . . . . to be wished as it would reunite and fortify all our colonists and the exclusive possession of that continent will fill each ocean with British shipping without depopulating this Country . . . . . . .” He recommends a plan of campaign and future conduct in considerable detail, and urges again and again the ease and importance of the conquest[12].

Lord Barrington recognized the importance of the project, for we find him writing to Simcoe, “desiring to know what force of ships and troops would be sufficient”[13]. Simcoe’s answer does not seem to have been preserved; but it is known that his son, the Lieutenant-Governor, always considered that it was his father’s plans which were followed in the conquest of Canada, 1759-1760, and that the conquest was undertaken by reason of his representations. Later in the year 1755 or in 1756, Simcoe sends to a Lord of the Admiralty, an elaborate scheme “for forming a body of seamen into a regular disciplined corps to answer all occasions of service in peace or war”—“a marine brigade”[14]. The Admiralty in 1755 revived the Marine force which had disappeared after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748: it has been continuously sustained since the revival and for many years without change from Simcoe’s scheme.

In 1756, he urges the formation of a “well regulated national militia”: he urges the repeal of the Game Laws, and permission to the people to shoot game—saying to the “Freeholder” whom he supposed to object, that “it is better to participate with a good grace your monopoly of wild birds to those whose labour feeds and clothes you and whose bravery . . . . . . . will defend you, your wife, your children, your estate and your real property, civil and religious, than have with a very bad grace your all exposed to be ravished from you by every merciless, rapacious invader . . . . . . . Let the destruction of game be but by fire arms . . . . . . . of the militia and its sale be absolutely prohibited and the contraveners impartially punished and the game will rapidly increase”. He points out that the “Buccaneers, the Negroes and the Indians who carry their guns for subsistence are the best marksmen and most dangerous partisans in the world and only want to be broken to the art of war to be the best regulars. So will the English prove when allowed the exercise of firearms, the prohibition of which by the Game Laws has broken that British spirit, and extinguished that bravery heretofore the terror of the French nation”[15]. A National Militia was indeed organized in 1757 to continue with little change until 1908; but the Game Laws remained practically the same.

In 1757, he urges the possession by British of a fortified harbour on each side of the Isthmus of Panama—the advantage “would be immense and surprising; nothing less . . . . . . . than the entire trade and dominion of the South Sea would be the natural consequence—here would be a vent for all the woollen, linen and silk manufactures of Great Britain . . . . . . . with an advanced price, we could sell every commodity infinitely cheaper than the Spanish Merchant could afford . . . . . . .”[16].

His last extant letters are insistent upon the necessity of conquering France by way of Quebec; he had, when Braddock was appointed in 1755 to carry on the war in America, pointed out to Hugh Percy, Earl (later Duke) of Northumberland “that France could not be advantageously attacked in America but by a direct seizure of Quebec”. This he repeated in 1759 to Northumberland; and also that “a peace on any other terms but the absolute dominion of North America will destroy us . . . . . . a peace which leaves an inch of ground in North America to France will undo Great Britain . . . . . . . We have now in our power by a vigorous attack on Quebec to become masters of all North America at one blow.”

To Admiral Boscawen about the same time he wrote: “The reduction of Quebec will at a blow give us the dominion over North America”; and to Lord Ravensworth: “Another war will ruin Great Britain . . . . . . in a few years if any temporary delusive peace now leaves an inch of Canada in the possession of France. We have it in our power now to ruin her there forever if we take Quebec this next year”[17].

In 1754 he wrote for the guidance of young officers in army and navy an admirable paper, “Maxims of Conduct”, or “Rules for Your Conduct”[18].

Captain John Simcoe was evidently well educated. He had read and could aptly quote Cicero in the original and was familiar with Plutarch (perhaps in Bryan’s Latin version of 1729): his style was clear, his logic convincing, his terminology accurate, his conclusions generally sound and always plausible—his writings were admirable in their vigor and force; if we cannot always agree with him we must at least recognize his candor, persuasiveness, utter loyalty to King and country, and devotion to their interests as he saw them.

It has been thought worth while to give the foregoing particulars of Captain Simcoe to indicate that many of the best traits of the Lieutenant-Governor were inherited. Of his wife, Catherine Stamford, little is known except that she was a model wife and mother.

On the death of her husband, Mrs. Simcoe removed from Cotterstock to Exeter, devoting her life to her two boys until the younger was drowned in the River Exe in 1764, and then to her sole surviving child, John Graves Simcoe. In 1766, her death took place at Newcastle.

Leeside House

The Birthplace of Captain John Simcoe, R.N., Hilton, Durham, England.

Where Governor Simcoe Was Born, Cotterstock, Northampton County, England

[1] Duncan Campbell Scott, in The Makers of Canada; John Graves Simcoe, Toronto, 1905, pp. 15, 17, erroneously places Cotterstock in Northumberland.

[2] David B. Read, Q.C., in The Life and Times of General John Graves Simcoe, Toronto, 1890, erroneously calls his father John Graves Simcoe: this error is repeated in a paper: Lieutenant-General John Graves Simcoe, First Governor of Upper Canada by F. R. Parnell, Niagara Historical Society, No. 36, 1924.

The father of Captain John Simcoe is said by John Hodgson in his History of Northumberland to have been the Reverend William Simcoe, Vicar of Long Horsley in that County; but the investigations made by Mr. J. Ross Robertson or at his instance, make it plain that this is a mistake, and that he was Vicar of Woodhorn, as stated in the text.

The genealogy has been traced back some generations:—(I) William Simcoe, of Spurstow, Bunbury Parish, Chester, was Churchwarden of that Parish in 1664; his eldest son was (II) John Simcoe, born 1624 or 1625. He is described as “a Chandler at the Sugar Loaf in Fetter Lane”, and afterwards of Red Lion Square, Gentleman. At the age of 40 he married, en secondes noces, Anne Dutton, a widow aged 36; Harleian Society, Vol. 34, p. 158. They had issue, inter alia, (III) William, born 1676, who became Curate at South Shields, Durham, and later Vicar of Woodhorn in Northumberland and Chaplain to the Prisoners in Newgate, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. By his first wife, Mary, daughter of John Hutchinson of Leeside House, Township of Hilton and Parish of Staindrop in the County of Durham whom he married January 3, 1609/10, he had issue, inter alia, (IV) John Simcoe who was born at Leeside House, November, 1710.

[3] “Vicenza Lopez and Manuel Bosques, lately Commanders of the Spanish Galley taken by His Majesty’s Ship Wager and José Borrell, late Commander of the schooner Santa Maria taken by His Majesty’s sloop Drake.” Wolf. I, 1, 4, (i. e., Papers obtained by Mr. J. Ross Robertson at Wolford.)

[4] Wolf. I, 1, 5-7.

[5] do. do. do. 14.

[6] do. do. do. 17. A letter to Captain John Simcoe at “Cotterstock near Oundle in Northamptonshire,” dated, Stratford in Essex, December 21, 1749, from Bamber Gascoigne, Lord of the Admiralty, suggested that Simcoe’s costs in the law suit should be paid by the Crown.

[7] Graves was Commander of the North American Fleet which attempted to enforce the Boston Port Act of 1774. In a letter to John Simcoe from Maddox Street, May 9, 1752, Graves presents compliments “to you and Mrs. Simcoe and infant Graves”. Wolf. I, 1, 20.

[8] For the preceding statement, see do. do. do. pp. 21, 28, 30, 44, 46, 53. Although from the Wolf. Papers, it is not made to appear that Simcoe was a member of this Court, do. do. do. 53, 54, it is certain that he was such. On March 1, 1757, it was ordered by the House of Lords that the President (Vice-Admiral Thomas Smith) and other members of the Court Martial including Captain John Simcoe should attend the House to be examined on the second reading of a Bill to permit Members of the Court to disclose some facts relative to the sentence of death pronounced on Byng: 15 Parliamentary History, Col. 809. See also Wolf. I, 1, 60, 61; and Simcoe gave evidence, March 2, 15 Parliamentary History, Col. 816, saying that he had no desire to disclose anything. It will be remembered that Byng was found guilty of wilful negligence at Minorca and was executed—in Voltaire’s bitter jest, pour encourager les autres. Simcoe seems to have had no doubt of the justice of the verdict and sentence.

The proceedings in the House of Commons in the matter will be found in the Report for February, 15 Parliamentary History, Coll. 803-807: the Bill passed and was sent up to the House of Lords, February 28, and failed to pass, do. do. do. Coll. 807-827.

[9] See his correspondence, February, 1757, with Admiral Sir Charles Knowles (who made a mess of things in the expedition against Rochefort and was superseded the same year) and with Temple, Wolf. I, 1, 58, 59.

[10] His master was James Cook, who in later years declared that he had received a great part of his training in navigation and seamanship from Simcoe—Cook had been a common seaman in the Navy only a few years before. We shall meet Cook again. There are still extant documents by Simcoe concerning the siege of Louisbourg. The official Record in the Admiralty gives as the date of Captain Simcoe’s death May 14; but the contemporary entry in the log of the Pembroke is May 15, the latter is probably correct.

[11] In a letter to Lord Ravensworth from the Pembroke, October, 1758, Captain Simcoe says that he had “been in the Gulf of St. Lawrence on a cruise with Charles Hardy attended only with the advantage of proving the ease of attacking Quebec.”

Admiral Durell’s Journal from October, 1758, is now available in the Archives at Ottawa. October 2, 1758, we find “Capt. Simcoe of the Pembroke ordered to discharge into the Garrison of Louisbourg the Party of Men and officers belonging to Bragg’s Regiment.”

On Oct. 17, Simcoe presided at a Naval examination (in Louisbourg harbour still).

On Oct. 25, Durell orders certain things to be accomplished “that we may sail the sooner for Halifax Harbour.”

On Oct. 26, Pembroke and Vanguard are supplied “with 4 months supply of surgeons necessarys.”

Nov. 7, prepared to sail for Halifax: Simcoe is mentioned as being supplied with signals.

On the 12th, they had not yet sailed and “ordered Capt. Simcoe of the Pembroke to receive from the Hospital at this place (Louisbourg), all the recover’d seamen belonging to His Majesty’s Ships that are at Halifax.” Sailed from Louisbourg, Nov. 15; arrived the 20th; 21st, Simcoe arranged a court-martial; 23rd, he presided at an enquiry.

Dec. 4, he is “ordered to issue slop”; Jan. 12, he examined qualifications of a lieutenant; during February, they get their ships ready for sea as soon as possible.

March 8, Simcoe examines conditions of damaged slops on the Elizabeth. March 22, the same on the Crown.

In Admiral Durell’s Journal . . . Princess Amelia, Halifax Harbour under date April 3, 1759, is the entry: “This day ordered the Captains of the Pembroke, Centurion and Squirrel to get their provisions compleated, the two first for four months . . . .” In his Remarks on Board the Princess Amelia from Halifax to the River St. Lawrence, under date May 15, 1759, is the entry “This day died Capt. Simcoe of His Majesty’s Ship Pembroke. I have appointed Capt. John Wheelock of His Majesty’s Ship Squirrel to act as Captain of the said ship until further orders.”

In the Log of the Pembroke, kept by James Cook, Master, of which a copy is in the Canadian Archives, the heading after the appointment of Captain Wheelock contains the names of “Captain Simcoe and Captain Wheelock.” The Pembroke, as is shown by its Log, took an active part in the siege of Quebec.

Wolfe had an unfavorable opinion of Durell. If Wolfe was right, while Durell seems to have had sufficient technical and professional skill, he was dilatory and unenterprising—and that in an undertaking which above all else demanded speed and daring. It may be that Wolfe was not wholly just: Saunders was of a different type. Durell’s Journal furnishes ample proof that they spent the winter in Halifax Harbour as all the entries are marked, “In Halifax Harbour”, and Durell mentions sending ships to cruise about and search for French boats, for English ships off their course and the like. Canadian Archives, “Admirals’ Journals, No. 7”.

Beckles Wilson, The Life and Letters of James Wolfe, London, pp. 421, 423, 424, is in error in supposing that Durell sailed a few days before Saunders left Spithead, February, 1759—Durell did not leave this side of the Atlantic that winter.

Since the above was written an admirable study of Durell’s movements has been contributed to The Royal Society of Canada by Miss E. Arma Smillie, M.A.; it is entitled: The Achievement of Durell in 1759, and is published in the Proceedings and Transactions, R. S. C., 3rd Series, Vol. XIX, Section II, p. 131.

In the memoir attached to the 8vo edition of John Graves Simcoe’s Military Journal, New York, 1844, is found the following statement: “The most striking occurrence of his (i.e., Captain Simcoe’s) life arose . . . . . . it is said from an accident improved in a manner peculiar to genius and extensive professional knowledge. The story is that he was taken prisoner by the French in America and carried up the River St. Lawrence. As his character was little known, he was watched only to prevent his escape, but from his observations in the voyage to Quebec, and the little incidental information he was able to obtain, he constructed a chart of that river and carried up Wolfe to his famous attack upon the Canadian Capital”. This is copied in Henry J. Morgan’s Sketches of Famous Canadians, Quebec, 1862, p. 116, and almost verbatim in David B. Read’s The Life and Times of Gen. John Graves Simcoe, Toronto, 1890, at pp. 9, 10, and less fully in David B. Read’s The Lieutenant-Governors of Upper Canada and Ontario, 1792-1899, Toronto, 1900, at p. 21, also in the paper mentioned in note 2 suprâ. Duncan Campbell Scott in his The Makers of Canada: John Graves Simcoe, p. 16, says: “It is stated that he was enabled to supply Wolfe with a chart of the river and with valuable information collected during an imprisonment at Quebec. No details of this capture and imprisonment are anywhere given and the story begins in shadow and does not close in light.”

It is certain that there is no truth in the story of alleged capture and imprisonment. Dr. Scott says: “The prototype of this tale is that of Major Stobo whose capture, detention in Quebec and subsequent presence with Wolfe before the beleaguered city are authenticated.” Morgan, op. cit., p. 116, says that Simcoe “was killed at Quebec in the execution of his duty in the year 1759 whilst assisting the ever glorious Wolfe in the siege of that City.”—an error repeated in more than one work, amongst them, Kingsford’s History of Canada, Vol. VII, p. 337, and my own La Rochefoucault. This seems to have originally been an incorrect inference from his monument in the Church of St. Andrew’s, Cotterstock.

To the memory of John Simcoe, Esq., late Commander of His Majesty’s Ship Pembroke, who died in the Royal Service upon the important expedition against Quebec in North America in the year 1759, aged 45 years. He spent the greatest part of his life in the service of his King and country, preferring the good of both to all private views. He was an officer esteemed for his great abilities in naval and military matters, of unquestioned bravery and unwearied diligence. He was an indulgent husband, a tender parent and a sincere friend; generous, humane and benevolent to all; so that his loss to the public as well as to his friends cannot be too much regretted. This monument was in honour to his memory, erected by his disconsolate wife, Katharine Simcoe, 1760.

Underneath lie Pawlett William and John, sons of the above John and Katharine Simcoe.

It may here be added that Surveyor-General Major Samuel Holland in a letter to Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe, at York (Toronto) from Quebec, January 11, 1792, says that he met Captain Simcoe a few days after the surrender of Louisbourg on his ship the Pembroke; and “during our stay at Halifax . . . . . under Captain Simcoe’s eye, Mr. Cook and myself compiled materials for a chart of the Gulf and River St. Lawrence, which plan at his decease was dedicated to Sir Charles Saunders, with no alterations than what Mr. Cook and I made coming up the River. Another chart of the River, including Chaleur and Gaspé Bays, mostly taken from plans in Admiral Durell’s possession was compiled and drawn under your father’s inspection and sent by him for immediate publication to Thomas Jeffery, (Jefferys) predecessor to Mr. Faden. These charts were of much use as some copies came out prior to our sailing from Halifax to Quebec in 1759.” The chart was reprinted in 1775 and 1794 with the Title—An Exact Chart of the River St. Laurence, from Fort Frontenac to the Island of Anticosti, showing Soundings, Rocks, Shoals, with views of the Lands. There is a copy in the Riddell Canadian Library at Osgoode Hall, Toronto.

Holland adds:—“Being General Wolfe’s Engineer during the attack of that place, I was present at a conversation on the subject of sailing for Quebec that fall. The General and Captain gave it as their joint opinion it might be reduced the same campaign, but this sage advice was overruled by the contrary opinions of the Admirals who conceived the season too far advanced so that only a few ships went with General Wolfe to Gaspé, &c., to make a diversion at the mouth of the River St. Lawrence. Again, early in the spring following, had Captain Simcoe’s proposition to Admiral Durell been put into execution, proceeding with his own ship, the Pembroke, the Sutherland and some frigates via Cut of Canso for the River St. Lawrence in order to intercept the French supplies, there is not the least doubt that Monsieur Cannon with his whole convoy must have been taken as he only made the river six days before Admiral Durell, as we learn from a French brig taken off Gaspé. . . . . . Had he lived to have got to Quebec, great matter of triumph would have been afforded him on account of his spirited opposition to many captains of the navy who had given it as their opinion that ships of the line could not proceed up the river whereas our whole fleet got up perfectly safe”. Revd. Dr. Henry Scadding’s Surveyor-General Holland, Toronto, 1876, pp. 3, 4.

[12] See this letter in extenso in my edition of La Rochefoucault’s Travels, published by the Ontario Archives for 1916, pp. 137-144; Wolf. I, 1 33-38, has verbal and unimportant differences; but there are in this manuscript some suggestions not in the printed text, e.g., Simcoe says:—“The cession of the neutral lands or whatever France may take in the West Indies or Mediterranean all would be an empty purchase for Canada.

Perhaps the erection of Canada into a kingdom for Prince Edward would for ages answer the purpose as well as be a greater, more rational, and permanent accession of strength to this Kingdom and Royal Family than the wearing of so many crowns by the House of Bourbon in different parts of Europe can possibly be to that family or France.”

It will be remembered that there was considerable discussion during the Seven Years’ War as to whether Canada should be retained and Guadaloupe returned to France on the Peace and that Franklin’s “Canada Pamphlet” turned the scale. See my Papers, Franklin in Canada, Empire Club Papers, 1923, and Benjamin Franklin’s Mission to Canada and the Causes of its Failure, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Dec. 1, 1923, 47 Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, 1923. It is also known that it was intended that the country to be formed by the Provinces at Confederation in 1867 should be known as the “Kingdom of Canada”, and that the name was changed at the instance of Lord Stanley who feared that such name would offend the susceptibilities of the United States. It was not intended in 1867, however, that the Kingdom of Canada should have a separate King as in Simcoe’s suggestion.

Prince Edward was, of course, not the Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria, but Edward Augustus, Duke of York and Albany (1739-1767), second son of Frederick, Prince of Wales, and younger brother of King George III.

A memorandum initialled by John Graves Simcoe and in his handwriting, presented by his daughter to the late Rev. Dr. Henry Scadding, reads as follows:—

“Major Holland told me that my father was applied to, to know whether his body should be preserved to be buried on shore. He replied, ‘Apply your pitch to its proper purposes,—keep your lead to mend the shot holes and commit me to the deep’ ”. Rev. Dr. Henry Scadding’s Surveyor-General Holland, Toronto, 1896, pp. 4-5.

Major Samuel Holland was Surveyor-General of Canada: Holland Landing and Holland River were named after him.

[13] Wolf. I, 1, 25. William Wildman, Viscount Barrington, was Secretary at War, Nov. 14, 1755, to Mar. 18, 1761: he was not Secretary of War or a principal Secretary of State at all but an official of inferior rank. At this time, and from 1539 to 1768, there were two Secretaries of State only; but in 1794, a Secretary of State for War was appointed. There are now five principal Secretaries of State, one being Secretary for War.

Barrington was not a member of the Cabinet; he made it a condition when he accepted the post of Secretary at War in Rockingham’s Administration that he should be permitted to vote against the Ministry, both on the Stamp Act and on the question of General Warrants. John Heneage Jesse: Memoirs of the Life and Reign of King George the Third, London, 1901, Vol. II, p. 21.

The paper as sent to Barrington is without the very appropriate motto from Cicero, De Oratoribus, 2, 40, 169, prefixed to the copy in John Graves Simcoe’s possession and printed in my edition of La Rochefoucault (ut suprâ) “Si barbarorum est, in diem vivere, nostra consilia sempiternum tempus spectare debent,” which was added in a copy sent a little later to one of the Lords of the Admiralty. Wolf. I, 1. 39-41. Captain Simcoe says that the letter to Barrington was “the substance of what I had spoken when Mr. Braddock was first destined to Virginia, whose fate was foretold. I say nothing more about it but leave to time and events to discover the error or solidity of the reasoning”, do. do. do. 44.

[14] do. do. do., 39-41. A copy of the letter to Barrington accompanied the scheme.

[15] do. do. do. 50-55.

[16] do. do. do. 70-72.

[17] Letter to Northumberland, do. do. do. 94, 95. Letter to Boscawen, do. do. do. 96: other letter, do. do. do. 97. In the last named letter he says that he “will write to Mr. Pitt very soon”. In all the letters he presses his claim to a flag.

[18] A memorandum in Wolford MSS., in the handwriting of Eliza Simcoe, a daughter of General Simcoe, reads:—“London, Portland Place, No. 3, Maxims of Conduct by Captain John Simcoe, R.N. The following maxims for the guidance of young officers in the British Naval and Military Service, were written in the year 1754, for the edification of his sons, by Capt. J. Simcoe, R.N., a highly accomplished officer, who, at the age of forty-five, died on service whilst commanding the Pembroke, 64, during Wolfe’s memorable expedition against Quebec.”

This summary draft, however hastily and inaccurately penned, will point out your course and serve as a general beacon in learning and executing your duty if you are well disposed; if you are not, a thousand volumes would be ineffectual. But know it is your indispensable duty to labour to become the great and accomplished officer, which duty your country has a right to expect from all in her service in half pay as full employment; though your views and promotion may be traversed by faction, malice or ignorance, though caprice or bad lessons may defeat your expectations arising from your consciousness of the best intentions and real service, though the wanton favour of the superficial and narrow-minded even the consciousness of demerit and guilt may give to the less worthy, or less able, the posts, which your poor country’s all may depend on, though birth will generally (and ought) where all other things are equal, have the preference,—bear the disappointment or injury with temperance in the day of National distress, which Heaven avert from this Kingdom. The voice of the public will do you justice amidst the obscurity to which you are condemned, call you forth for its own sake and the great accomplished officer shine with double splendour, when the “Will of the Wisps”, if they should exist, will vanish.

Cotterstock, Octr. 20th, 1754. J. Simcoe.

RULES FOR YOUR CONDUCT

1. Let the groundwork of your whole conduct be a just respect for and love of God; know that with such respect, every man must necessarily be brave, and without such due impression every man must as necessarily be a coward.

2. The love of your Country and King, which necessarily flows from the first maxim, must be your ruling principle; let no ill usage taint this principle, to the observance of which you must always and cheerfully be ready, when occasion calls to sacrifice life, fortune and the strongest ties.

3. Cherish carefully that delicate and essential principle Honour, which, if pure will readily dictate what is fittest to be done, and what is to be avoided more than death.

4. Remember always that you are the servant of the Public, that its honour and safety may in a greater or lesser degree, be entrusted to your conduct; you can then never without a violation of your trust, sacrifice either to what busy blind selfishness may repute private good, or suffer the least competition between private and public emolument; the labourer is undoubtedly worthy of his hire if he use the delegated authority and wealth of his master; to labour only for himself he deserves a halter instead of a ribbon; instances have been where Officers have uniformly done their duty in sacrificing private to public regards, and for reward have met with neglect, contempt or injury; others have as uniformly sacrificed public duty to selfish pursuits and in the chase rose to opulence, favour and credit. Let no ill maxims, however general or successful, alure you from, nor ill usage slacken your devout discharge of your duty; you are sure of the noblest and most lasting reward, the testimony of a good conscience.

5. Let your obedience to the commands of Superior Officers be exact, implicit and cheerful; if those commands should at any time be indiscreet, or lead you instantly to sudden death you are in all cases most punctually to execute them, and know the first virtue in an inferior is cheerful obedience and,—hesitation, impiety—your superior alone being answerable for his orders.

6. He who knows not how to obey, can never know how to command; you are therefore not only to obey, promptly and with all your spirit the commands of a Superior, but you are in the course of your service to learn practically the distinct duties of every officer.

7. Be strenuous in learning your duty, be not afraid of labour, nor of the Tar-bucket; but constantly attend, when duty requires you not elsewhere, the boatswain’s people in knotting, splicing and rigging, handing and reefing; perfect yourself in the detail of all business from the stem to the stern, from the keelson to the masthead; and learn all duties from the common seasman’s to that of the highest commission officer. When you come to be an officer you’ll make but an awkward figure, if in ordering the execution of any service you know not how to go about it dexterously yourself; besides such general knowledge in the detail will give you lights and a presence of mind which on occasion may save the Crown’s ship or squadron, with the lives of invaluable subjects.

8. Charles the 12th of Sweden used to say that “he was but half a man who was without numbers”; it is as true a maxim that he is but half a Sea Officer who is not equally a good soldier as Seaman, and you must not therefore, as is too common, think yourself a fine officer, if you can rig and work a ship in the ordinary methods, and in which without the theory of ship working, you’ll probably find yourself outdone by the collier or your own forecastle man; you must strenuously apply to learn the duty of a soldier.

9. It will not in this pursuit be sufficient to learn the battalion exercise; you must learn all the necessary military motions, the breaking and forming any body of men into Platoons, Divisions, Battalions, Brigades, all the various dispositions and combinations, camp duty, field duty, garrison duty, trench duty; in short, you must successfully learn whatever pertains in the Infantry to the office of Sentinel, Corporal, Adjutant, Lieutenant, Captain, &c., upwards to that of the General; thus your knowledge must rise from the small detail to a comprehension of the great parts of the military science till you are able to plan or execute the great operations of War founded on rational and systematical principles.

10. This progress towards the finished officer will be slow and ineffectual if in your course you enter not into the rationale of things; you must by enquiry, reading or reflection learn the reason of every process from the strapping of a block to the orders of battle, in the seaman’s part, and from the posting of a sentinel to the orders of battle, according to the genius of the ground, the disposition, nature and number of the enemy in the soldier’s duty; when reasoning goes not hand in hand with the practice in both services it is but routine, the act of a parrot. You can pretend to, and you’ll be lost in most things which have not occurred to your grovelling experience, unable to remedy as invent in common exigencies; what then would be your figure, or where the lustre of the officer on extraordinary occasions?

11. It will greatly aid you to gain some knowledge in designing and in fortification; the latter will be useful when you attack or defend any fortified place, or are to defend any Port where intrenchment may prolong your defence, and save your honour as man till you are relieved; the first will be serviceable in infinite occasions in the Sea and Land services; the French make it a rule to give the government of their Colonies to their Sea Officers but their officers are well qualified as Soldiers, Seamen and Engineers; we begin to follow their example in those promotions; can we doubt that the maxim would not be as general as rational if our Sea Officers would take pains to inform themselves in those respective duties?

12. Exactitude is a necessary quality, but affect not the Martinet. It is dwelling on the surface without penetrating the essence of things. It is labouring about minutes and things of no consequence, betraying want of understanding and an incapacity of entering into the spirit of the service, or of combining and varying of things according to circumstances; such a one may be dignified with the Staff of a Velt-Marshal or Admiral, but he is at bottom a Corporal or boatswain’s mate.

13. Remember that as a Surprise is most ruinous in its consequences, it is the greatest disgrace an Officer can incur, as it must arise from negligence; be therefore ever alert, vigilant, and careful on your post, nor let inevitable destruction tempt you to desert it without order in any circumstances whatever. By sea or land the same rule holds good in civil and ordinary life; whatever your station be, act in it well and with dignity, considering it as a post entrusted to you by Providence; this just behaviour will in a cottage make you a greater man than a Prince who acts remissly.

14. In your reading avoid everything trivial or which leads not directly to the knowledge of your duty, such as romances, novels, plays or poems; amongst these are to be excepted Homer, Virgil or any Tyrtaeus if you meet with them; a little practical Geometry will be necessary. Above all, read a thousand times over Caesar, Polybius, Arrian, Thucydides and Xenophon. In the latter you’ll find the politest scholar, the best man, the finest gentleman, and excepting the much injured Alexander, the greatest Captain in all ages. If you know not the original languages get the best translations. These will open your understanding, enlarge your ideas, ripen and inform your judgment better than a thousand campaigns under incompetent masters. Do not think that the benefit of reading these great military Masters is confined to the Land service; their lessons by analogy necessarily reach the Sea service, and the Military art; as good sense in the application belongs to both elements and speaks all languages; you will find in these and some other authors a Naval Art of War more profound, intelligent, scientific and therefore more bold than has appeared since their days. No wonder the greatest Sea Captains of antiquity as of modern times were those who were the most accomplished leaders of Armies on shore.

15. The choice of good military authors is very small, but for the honour of the military profession they are sufficient for all purposes and abound with the best precepts as examples, for civil and military life, and I hazard my reputation on this assertion that they are not only the best models for military conduct, but for conduct in every station of the patriot, courtier, statesman, magistrate, and finished gentleman.

16. I must not omit to observe that military duty of two kinds—duty of danger and duty of fatigue; both go or ought to go, unless in critical conjunctures, by rotation. Duty of danger begins with the oldest Officer, suiting the command, who has a right to the post. Honour on extraordinary occasions requests voluntarily the post of danger; if granted, labour to discharge adequately the honour and trust reposed in you; if denied you have done your duty with a good grace, but if you should be appointed to a duty of fatigue which goes by rotation, beginning with the youngest Officer, and if it should be a tour of a junior Officer you must without the least hesitation or discontent execute it cheerfully, nay, it will be for your advantage, for every such duty will be probably a new lesson towards perfecting your knowledge.

17. Inure your body to bear extremes of heat and cold, hunger and thirst, and exercise to agility and strength by suitable toil.

18. Use your Officers and men with humane treatment, set them the examples of temperance, modesty and obedience to the laws of your Country; regard the orderly and deserving; punish inexorably the disobedient and flagitious.

19. Avoid quarrelling. Give offence to none, nor suffer it from any, but you are to intermit it when you are on actual service, with which no consideration is to interfere.

A statement of the Admiralty Records concerning Captain Simcoe, and an account of his services extracted from Charnock’s “Biographia Navalis” are subjoined. These I owe to the courtesy of the Secretary of the Admiralty.

PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE

Public Record Office, 11 Jan., 1924.

Result of a Search in the Admiralty Records:

| Name | John Simcoe |

| Birthplace | v |

| Baptismal Certificate | v |

| First Entry | v |

| Passing Certificate | v |

| Seniority | Lieutenant 7 Aug. 1739; Captain 28 Dec. 1743. |

| Death | 14 May, 1759. |

| Ship | Rank | Date of Entry | Date of Discharge | |||

| New-castle | Lieut. | (3) | 7 Aug. | 1739 | 11 May | 1740 |

| ” | ” | (2) | 12 May | 1740 | 15 Oct. | 1740 |

| Princess Caroline | ” | (3) | 16 Oct. | 1740 | 14 Jan. | 1741 |

| Burford | ” | (3) | 15 Jan. | 1741 | 26 Apl. | 1741 |

| Russell | ” | (4) | 27 Apl. | 1741 | 7 June | 1741 |

| Cumberland | ” | (2) | 8 June | 1741 | 1 May | 1743 |

| ” | ” | (1) | 2 May | 1743 | 18 July | 1743 |

| Thunder Bomb | Master & Commdr | 19 July | 1743 | 27 Dec. | 1743 | |

| Kent | Captain | 28 Dec. | 1743 | 18 Feb. | 1744 | |

| Seahorse | ” | 19 Feb. | 1744 | 28 Jan. | 1745 | |

| Falmouth | ” | 29 Jan. | 1745 | 24 Oct. | 1746 | |

| H.P. x | ” | 25 Oct. | 1746 | 13 Mar. | 1747 | |

| x— | Half Pay | |||||

| Prince Edward | Captain | 14 Mar. | 1747 | 12 Sept. | 1748 | |

| H.P. | ” | 13 Sept. | 1748 | 2 July | 1756 | |

| St. George | ” | 3 July | 1756 | 4 Apl. | 1757 | |

| Pembroke | ” | 5 Apl. | 1757 | 14 May | 1759 | |

Note.—Passing Certificate cannot be found; for his Services before being appointed Lieutenant the name of a ship on which he served previous to 1739 would assist in a further search being made.

From Charnock’s “Biographia Navalis”, Vol. 5, London, 1797.

SIMCOE, JOHN,—The name of this gentleman is omitted in many of the navy lists we have seen. In some of them he is stated to have been promoted to the rank of Captain in the navy, and appointed to the Kent on the 28th December, 1743; but Mr. Hardy states his first commission to have been to the Falmouth, agreeing, however, with the date just given. We find no other mention made, not even of the commands held by this gentleman, till the latter end of the year 1756, when he was captain of one of the ships then lying at Portsmouth and was one of the members of the court-martial convened, in the month of December for the trial of Admiral Byng. Nothing farther occurs relative to him, except that, in 1758, he commanded the Pembroke, one of the fleet ordered in the ensuing year on the expedition against Quebec. He died on board that ship, in the River St. Laurence, on the 14th of May, before any operations had taken place.

(“A Chronological List of the Captains of His Majesty’s Royal Navy”, by Rear Admiral John Hardy, London, 1784.)

John Graves Simcoe was a little over seven when his father died and the family removed to Exeter; he had already received the rudiments of an education and shortly after removal to Exeter he entered the Free Grammar School in that Cathedral City. He was attentive and studious, an apt but not a brilliant scholar; what he learned, he learned thoroughly and retained permanently; at an early age, he read Homer in Pope’s translation, and as a boy, he took part with his companions in a play portraying the scenes of the Iliad. He attained proficiency in the branches of knowledge taught in the school and was among the first, if not the first in his standing; he was also well versed in modern history, not as yet taught in schools, and he eagerly read every tale of war. Active, filled with a spirit of emulation, he was foremost in all games of boyhood—his standing on the playground equalled that in the schoolroom.

No myths have grown up about him, he seems to have been a hardy, active, well-bred English boy of the best type, and he was likeable and ever on good terms with his fellows.

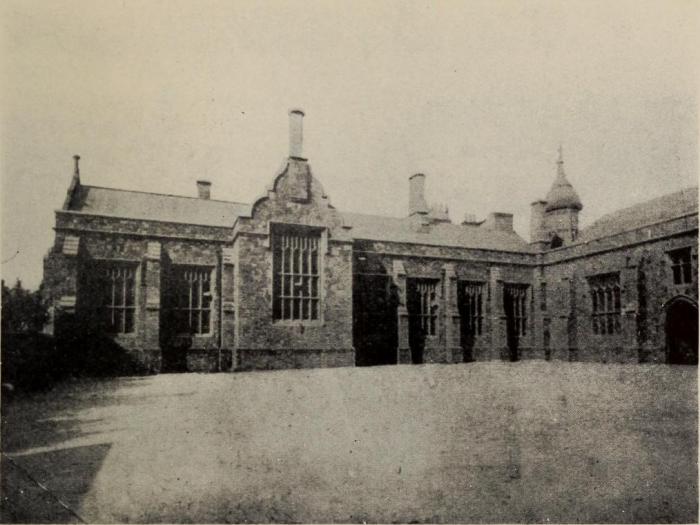

Merton College—The Quad, Oxford, England

In 1766, he was sent to Eton, and three years afterwards he entered at Merton College, Oxford. He took a high place in both Colleges in his studies—there is reason to think, also in sport—but there was nothing phenomenal in either. Extant examples of his English and Latin verses in manuscript indicate diligence, accuracy and ability; and volumes of ancient and modern history with annotations in his own hand sufficiently evidence his devotion to that study.

He does not seem to have taken a degree[1]. The reason is not known, but it has been said that it was due to ill-health[2]. Whatever the reason, he remained at Merton for only one year and returned to Exeter, where he studied military science under a tutor[3], having been promised an Ensign’s commission by friends of his mother.

All was not going well with the Empire; George Grenville’s theory of Colonies that they existed for the advantage of the Mother Country had resulted in 1765 in the Stamp Tax; the American Colonies resisted; and although Grenville lost power almost immediately, Townshend continued Grenville’s policy. America still resisted and the King, George III, urged the use of compulsion. Whatever might otherwise have been the result, when the King succeeded in 1770 in making Lord North Prime Minister, an open war of force was inevitable.

This is not the place to treat at large of the merits of the controversy resulting in the Declaration of Independence and the destruction of the old British Empire[4]. It is, however, certain that men like Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Adams, never contemplated separation from Great Britain until 1775, nor could any wish so to do until that time be discovered among the people of the Thirteen Colonies—that Chatham in 1773 said that the “New Englandmen feel as Old England should feel”[5]—that it was only when a bungling Ministry aided by a conscientious but ill-unbalanced King who had been as badly educated as he was badly advised, insisted on crushing by military and mercenary force all aspirations of a free people to free self government that Independence was declared.

A very large proportion of the Colonists did not recognize the necessity for severing connection with the Mother Country; but they were overborne, and the result we know.

There is nothing to indicate that Simcoe ever saw any merit in the contentions of the Colonies—he says “the late war in America . . . . . . he always considered as forced upon Great Britain, and in which he served from principle . . . . . . Had he supposed it to have been unjust he would have resigned his commission, for no true soldier and servant of his country will ever admit that a British officer can divest himself of the duties of a citizen or in a civil contest is bound to support the cause his conscience rejects”[6].

All his education and the example of his father tended to impress him with certitude that the King and his Ministers were right, and he never wavered in that conviction. In 1770, he entered the Army as an Ensign in the 35th Regiment of Foot[7], in which his intimate friend Edward Drewe served.

He was not sent to America with the first detachment of his regiment but remained in England until May, 1775; he arrived on the last ship of the fleet at Boston on June 19, 1775, two days after the famous battle of Bunker Hill[8]. His god-father, Vice Admiral Samuel Graves[9], was in command of the North American fleet charged with enforcing the Act closing Boston Harbour to commerce; and Simcoe was entrusted by him with certain services, the performance of which brought him into acquaintance with many of the American Loyalists—“from them he soon learned the practicability of raising troops in the country whenever it should be opened to the King’s forces; and the propriety of such a measure appeared to be self-evident. He, therefore, importuned Admiral Graves to ask General Gage that he might enlist such negroes as were in Boston and with them put himself under the direction of Sir James Wallace who was then actively engaged at Rhode Island and to whom that Colony had opposed negroes: adding to the Admiral, who seemed surprised at his request, ‘that he entertained no doubt he should soon exchange them for whites’[10]. General Gage, on the Admiral’s application, informed him that the negroes were not sufficiently numerous to be serviceable and that he had other employment for those who were in Boston.”

Simcoe continued with the 35th Foot in Boston when the City was besieged by the Revolutionary troops[11]; during this siege, he purchased a Captaincy in the Grenadier Company of the 40th Foot[12].

Washington, as Commander-in-Chief of the American Forces, assumed command of the siege of Boston, and, taking advantage of an oversight on the part of General Howe, the British Commander, he, early in March, 1776, seized and fortified Dorchester Heights and placed the besieged Army in a most critical position. On March 17, the Army set sail for Halifax, which was speedily and successfully reached.

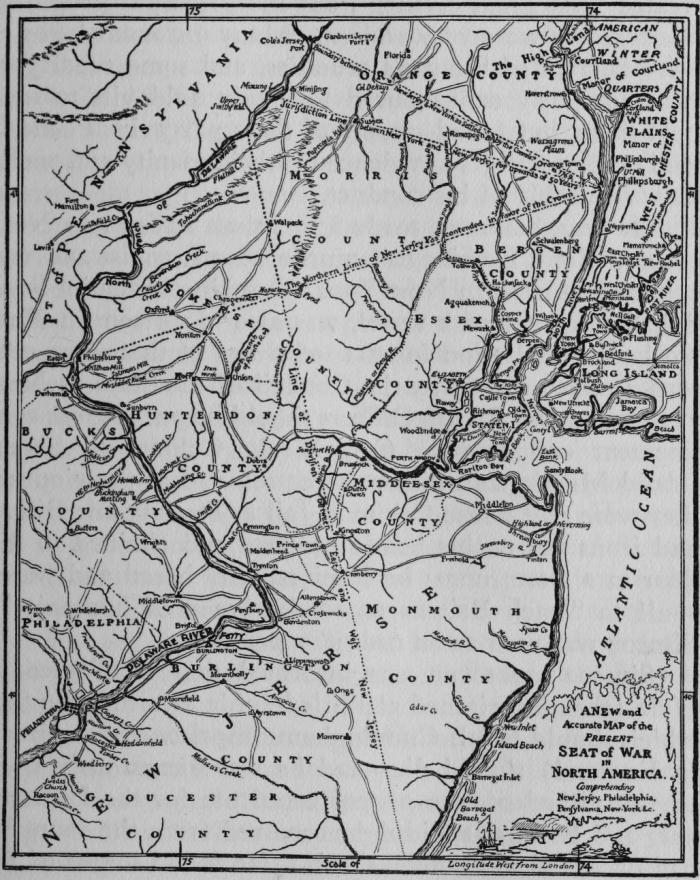

On June 11, 1776, the Army left Halifax for Sandy Hook, where it arrived June 29; then proceeded to Staten Island, where it disembarked July 3; here reinforcements were met, and the 40th was formed in Brigade with the 17th, 46th and 55th under Major Grant—the Grenadier Companies with those of other Corps were formed into Grenadier Battalions.

Considerable operations took place during the summer of 1776; Long Island was reduced, the American Army retiring in boats across the East River to New York and abandoning their fortifications—subsequently New York was captured, the 40th taking an active part in the operations.

The Americans took up another position, and General Howe, to separate them from New England, embarked a portion of the British troops, including the Grenadier Companies of the 40th, in boats, and landed them at Chester, October, 1776. Six days later, Howe re-embarked this detachment and landed at Pell’s Point, near which a sharp engagement took place.

Washington, on evacuating New York, took up a position at White Plains, where Howe was about to attack him in force, October 31, when the Americans retired to the New Castle Heights. Howe then reduced Fort Washington. The Regiment then joined the forces of Lord Cornwallis, who, November 18, crossed the North River, and he pursued the Americans for three weeks through New Jersey, until they crossed the Delaware. The weather becoming cold, the British troops went into winter quarters at Brunswick.

During that winter, Simcoe went to New York expressly to solicit the command of the Queen’s Rangers: “the boat he was in being driven from the place of its destination, he was exceedingly chagrined to find that he had arrived some hours too late, but he desired that Col. Cuyler, Sir William Howe’s Aide-de-camp, would mention his coming thither to him as well as his design”[13].

The American Army, recrossing the Delaware, marched towards Trenton; Cornwallis, recognizing the design, marched out to meet them, leaving the 40th and other regiments behind at Princeton under Lieutenant-Colonel Mawhood, January 3, 1777. Mawhood, in obedience to orders, marched from Princeton for Maidenhead, a village about half way to Trenton; he met American troops almost immediately on the beginning of the march and a sharp engagement, the Battle of Princeton, took place, the 40th being driven back to that place with serious loss[14].

Brunswick was not attacked, but during all the winter and following spring there were continual skirmishes with more or less loss on both sides: Amboy was the headquarters for the 40th, but the Flank Companies, including Simcoe’s, were stationed at Brunswick.

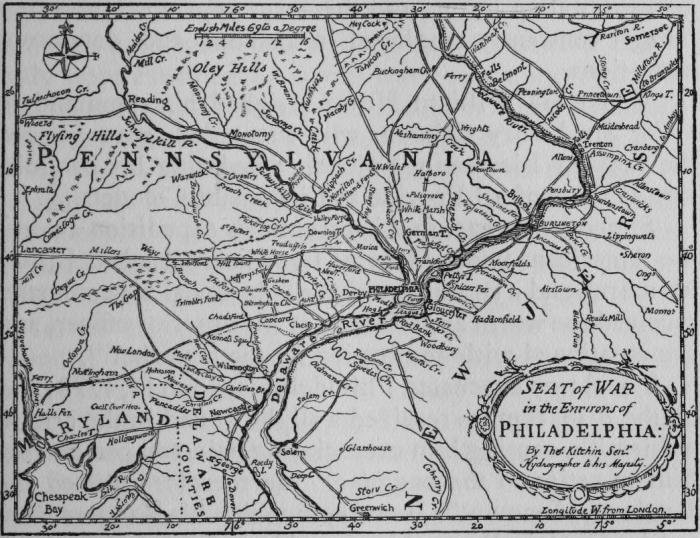

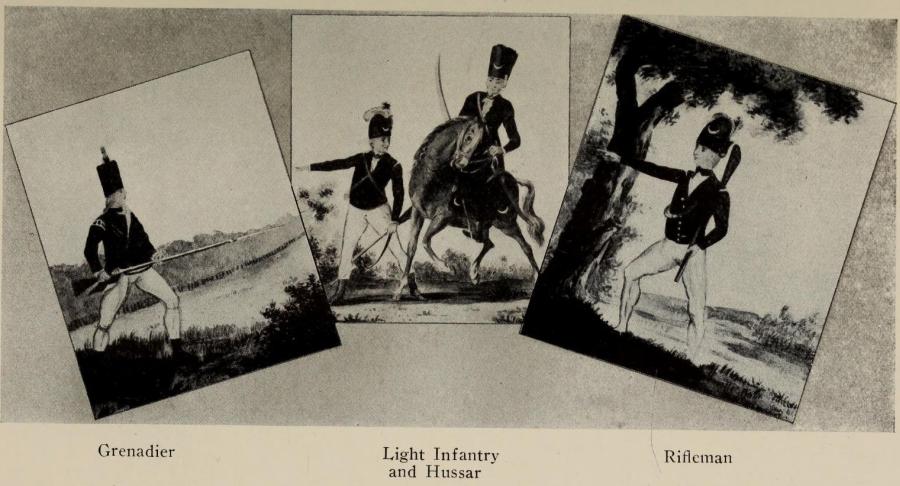

Howe determined to change the seat of war, and, in June, embarked his army for the Chesapeake; arriving, August 24, at Elk Ferry, a few days thereafter he marched on Philadelphia, but Washington, taking prompt advantage of Howe’s dilatoriness, also moved his troops and was able to interpose them at Brandywine. There a sanguinary battle took place, September 11, in which the British had decidedly the advantage. Simcoe, who was with the 1st Battalion Grenadiers, was wounded in this battle; Captain Wemyss, of the 40th, was in command of the Queen’s Rangers, who greatly distinguished themselves during the engagement[15]. Simcoe, by reason of his wound, missed the Battles of Concord and Germantown: on October 15, 1777, his cherished hope was realized, when Howe gave him the command of the Queen’s Rangers, upon which he had long set his heart—he received the Provincial rank of Major, and joined the regiment the following day[16].

[1] Foster’s Alumni Oxonienses, Oxford, 1888, Vol. 2, p. 1297, has the entry:—

“Simcoe, John Graves, S. John, of Cotterstock, Northants arm. Merton Coll. matric., 4 Feb., 1769, aged 16: Major-General in the Army, the first Governor of Upper Canada, etc., M.P. St. Maws, 1790-2, died 26 Oct., 1806”. The Warden of Merton during Simcoe’s residence was the Revd. Dr. Henry Barton, Royal Chaplain. Foster’s Oxford Men and their Colleges, Oxford, 1893, pp. 90, 91. Merton had by this time outlived its earlier supremacy.

[2] John Ross Robertson, The Diary of Mrs. John Graves Simcoe, Toronto, 1911, p. 16. It is known that notwithstanding, and in some degree because of, his profession and active habits, Simcoe suffered from ill-health in later years. I have not been able to obtain any information from the Exeter School or Merton College as to Simcoe. The Warden of Merton says that the College possesses no records of its members other than Wardens and Fellows in the 18th century, and the Head-master of Exeter School at Exeter says there are no registers of that school extant prior to 1817, and it is not even known how and when the former registers were destroyed.

In an admirable work, The Eton College Register, 1753-1790, edited by R. A. Austen Leigh, published at Eton by Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co., 1921, which gives biographical notices as far as possible of every boy attending Eton and appearing on the lists of the College from 1753-1790, appears the following entry:

“Simcoe 1765-68 (tutor Heath) John Graves entered 16 Sept. 1765 (Bagwell) o.s. John S. of Cotterstock, Co. Northampton, Capt. R.N. by Katharine Dau. . . Stamford, b. 25 Feb. 1752; educated at Exeter before going to Eton; Matric. at Oxford from Merton College 4 Feb. 1769. Admitted student Lincoln’s Inn 10 Feb. 1769. Ensign 35th Regiment 27 Apr. 1770; Major-General 1798; Lieut.-Gen. 1801; Commanded the Queen’s Rangers in the American War; M.P. for St. Mawes 1790-92; Governor of Upper Canada 1792-96; m. 30 Dec. 1782 Elizabeth Posthuma, Dau. Col. Gwillim of Old Court, Hereford; appointed Commander-in-General in India 1806, but being taken ill on his way out came home and d. at Exeter 26 Oct. 1806 (Dict. Nat. Biog., Lincoln’s Inn Reg., The World 7 Apr. 1787)”.

The latest entry of Simcoe’s name in the actual school lists of Eton is in “A Bill of Eton College, August, 1768”, in which Simcoe appears among the 5th Form Oppidans.

“Bagwell” means that he entered the Dame’s House of Miss Bagwell who lived at Gulliver’s.

[3] This was the usual course pursued by those intending to join the army who desired to be competent officers—the College of Sandhurst was not incorporated until 1863—we find the Earl of Chatham placing his eldest son under the tutorship of Captain Kennedy for instruction in fortification in the view of entering the Army. See Letters to Thomas Hollis from Chatham, dated, Burton-Pynsent, April 13 and 18, 1773. John Heneage Jesse’s Memoirs of the Life and Reign of King George the Third, London, 1901, Vol. III, pp. 504 sqq., 507.

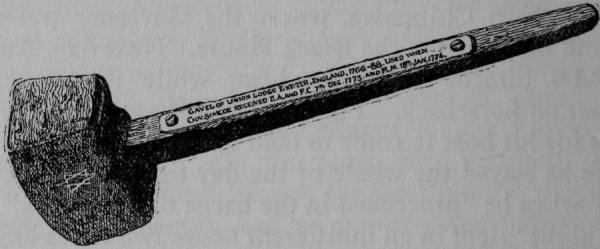

Before Simcoe left for America he was made a Mason: particulars need not here be gone into—it is sufficient now to say that he was proposed at the Union Lodge of Free Masons meeting at the Globe Tavern in Exeter, November 2, 1773, and was admitted to the first two degrees at a meeting of the same lodge at the same place December 7, 1773, and to third at a meeting of the same lodge at the same place Jan. 18, 1774. See Chap. XXIX, post.

[4] To the philosophic student of history this result seems to have been inevitable unless the statesmen in London made a radical and revolutionary change in their conception of the status of Colonies and Colonists; and that was still far in the future. The chief cause of the conflict was the determination of England to control the Colonies, and the determination of the Colonies to govern themselves. “England was an oligarchy; each Colony was inevitably a democracy. The Englishmen who crossed the seas to found new homes were the most resolute and independent of all their countrymen. They wielded real authority in their new communities and however loyal in spirit to the mother land they might seem, they deemed themselves self-governing. In founding such states through her own sons, England had sown profusely the dragon’s teeth of democracy, and yet endeavored to check it by the weakest and clumsiest application of aristocratic government”. Prof. Wrong in 4 The Canadian Historical Review (December 1923), p. 338; cf. passim Egerton’s The Causes and Character of the American Revolution, Oxford, 1923.

[5] Letter Chatham to Hollis from Burton-Pynsent, February 3, 1775, 3 Jesse, p. 502.

[6] A Journal of the Operations of the Queen’s Rangers From the End of the Year 1777 to the Conclusion of the late American War. By Lieutenant-Colonel Simcoe, Exeter. Printed for the Author, 4to, Introduction: Simcoe’s Military Journal . . . . . New York, Bartlett & Welford, 1844, 8vo., p. 13. See Chapter III, Note 13, post.

W. R. Givens in an article, Unpublished Letters of Governor Simcoe, The Canadian Magazine, Vol. 30, (March, 1908), at p. 404, says that the words used by Simcoe in a letter, Exeter, January 2, protesting against “the anarchy and tyranny in which the selfish and disgraceful factions of this country has betrayed” his correspondents Loyalists in America are “a clear evidence it would seem that Mr. (Duncan Campbell) Scott errs in his statement that the Governor (Simcoe) believed the war was forced on Great Britain. Rather, it would seem, the Governor felt that Great Britain forced the war herself”. But Mr. Givens has misunderstood Simcoe’s meaning; he was referring not to the War of Independence, but to the Peace of 1783 which had not sufficiently provided for the Loyalists in Simcoe’s view and in that of most, if not all, of the Loyalists—they are the “deserving and much injured friends”. Mr. Givens is also in error as to the date: it must have been January, 1784, not 1782: the letter of Mr. Arnott sufficiently fixes the date of Simcoe proposing to enter Parliament. See Chapter IV, post. It will be remembered that North had been dismissed only on December 18, 1783, that he had as a colleague Lord Carlisle, mentioned by Simcoe, and that Pitt was not yet firm in the saddle. Simcoe makes clear his view of the proper relation of Colony to the Mother State in a letter of July 26, 1763, referred to more particularly in note 16, Chapter XIII; he considers the American Commissioner, Timothy Pickering, “a violent, low, philosophic, cunning New Englander” as “he held out to our gentry of the same stamp . . . . the doctrine that assimilates States to private families, and deduces from the child growing up into manhood and being capable to take care of himself that it is right and natural for a son to set up for himself and by a just inference that such is the disposition and tendency of all States.”

[7] In a work by Captain R. H. Raymond Smythies, Historical Records of the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) now First Battalion The Prince of Wales Volunteers (South Lancashire Regiment), Devonport, 1894, cr. 8vo., at p. 79, note, it is said that “at the age of nineteen he received an ensign’s commission in the 53rd Regiment”; but the reference given to Simcoe’s Military Journal shows 53 to be a misprint for 35. The Historical Record of the Fifty Third or the Shropshire Regiment of Foot, by Richard Cannon, London, 1849, does not contain Simcoe’s name.

[8] In a letter to his mother, written from Boston shortly after his arrival, Simcoe says:—

“Boston, 22nd June, 1775.

Dear Madam:—We arrived here on the 19th, being the last ship of the fleet. Two days before our arrival the dreadful scene of civil war commenced, for at a distance we saw the flames of Charlestown and steered into the harbour by its direction.

On our arrival we learned that the rebels had taken possession of the heights on the opposite side, from whence the town at that time blockaded by numbers was endangered. To force this was absolutely necessary and it was done in the most glorious manner—an action by the confession of veteran jealousy that exceeds whatever had before happened in America and equalled the legends of romance. It proves to me how very narrow are the limits of experience.

Our light infantry was commanded by Drewe, whose behaviour was such as outdoes all panegyrick by every confession. He was wounded in three places, but fortunately neither to endanger life, limb or disfiguration. This I assure you upon my sacred honour, nor could I write in such case was the friend of my soul in the least danger. Massey was wounded and Bard, to my great regret, killed, having as ever, remarkably distinguished himself. Of our other company, the Grenadiers, they have equalled the misfortunes and gallantry of the others. The able and generous Lym is wounded almost past recovery; B. Campbell is slightly hurt, and by the consequence of this action we are free from any anxiety; we have strongly fortified it, and I suppose shall wait till we have at least 5,000 men from England before we commence operations which then I doubt not will be decisive—Would to God, Lord Chatham, Richmond—who have inflamed to rebellion, would lead on these infatuated wretches to their inevitable destruction. I have much to do—am now going to sup with Mrs. Graves. All well there—nor should I have written but to assure you that we are safe and shall be for some time, and by my sacred honour to confirm Drewe’s letter should it not be satisfactory; perhaps his wound may be his preservation. Into the hands of God we commend our cause, nor do I doubt but this severe check they have received may cause an effectual reconciliation. The reason we lost so many officers is on account of their dress. This is altered as we now dress like soldiers. God bless you. I will write as often as possible. Adieu.

I am ever your affect. son,

J. G. Simcoe.”

To understand this letter fully it must be borne in mind that the Americans had taken possession of the Peninsula of Charlestown on the north shore of the Charles River opposite to Boston; and the left wing of the British Force in advancing at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill (fought chiefly be it said on Breed’s Hill) had to contend with a body of Americans posted in the houses in Charlestown, and in the conflict the town was set on fire and burned to the ground. This was June 17, 1775. See Stedman’s The History of the . . . . . American War, London, 1794, Vol. I, pp. 124-127. This battle has been absurdly enough, claimed as a victory for the Revolutionary Troops.

D. B. Read in his Life and Times of Gen. John Graves Simcoe . . . . says at p. 11, “Simcoe did not embark from England with his regiment, but he landed at Boston on the memorable day of the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, 17th June, 1775”. Dr. Duncan Campbell Scott in his John Graves Simcoe (Makers of Canada Series) says, p. 18: “He . . . . reached Boston only on June 17th, 1775, in time to hear the roar of guns on Bunker Hill and see the town streets filled with wounded and dying”. No authority is given for the statements as to the day of his arrival at Boston, and his own statements to his mother would seem to conclude the question.

[9] Simcoe naturally enough speaks of Admiral Graves as a “most upright and zealous officer”; and probably with truth. Graves had the bad fortune to be sent on a most ungracious duty, that of carrying out the “Boston Port Bill”, (1774), 14 George III, c. 19, which was an Act “to discontinue . . . . the landing and discharging, lading or shipping of goods, wares and merchandise at the Town and within the Harbour of Boston in the Province of Massachusetts Bay in North America” from and after June 1, 1774. This Act was in retaliation for the “Boston Tea Party”. Graves had an inadequate force and he undoubtedly failed, probably not by his own fault; while no charge was laid against him, he was superseded, January, 1776. His advance in rank to Admiral of the Blue and Admiral of the White, however, was not checked. See D. N. B., Vol. XXII, pp. 437-8.

[10] Simcoe’s own words, Journal, p. 14, in the Exeter edn. at second page of Introduction.

The real objection to the enlistment of the negroes was the same as that taken to the enlistment of negro troops by the North in the Civil War and to their use in Africa as well as in Europe, because it was not well to allow them to feel that they might fight against any white man. It was the same feeling that influenced many Englishmen to deprecate the use by Britain of French-Canadians against the revolting North American Colonies: amongst those who so objected was Maseres, a former Attorney-General of Quebec, who said:—“I should be sorry to see the (French) Canadians engaged in this quarrel . . . . if they were to subdue the other Americans, I should not like to see a Popish army flushed with the conquest of the Protestant and English Provinces”, Canadian Archives, Shelburne Papers, Vol. 66, p. 53. James Wallace went out to America in 1774 as Captain of the Rose, a 20 gun Frigate, and at this time was “actively engaged in those desultory operations against the coast towns which were calculated to produce the greatest possible irritation with the least possible advantage.” He was knighted in 1777 and subsequently became an Admiral. See D. N. B., Vol. LIX., pp. 100, 101.

[11] He is said to have acted during this siege as Adjutant of his regiment “but there is no record of his appointment”. Diary, p. 16.

[12] The existing records of the 40th Foot indicate that this occurred during the siege; Captain Smythie’s Historical Records, ut suprâ, gives, p. 46, the Roll of Officers of the 40th at the date of the Battle of Germantown from the Army List for 1777, corrected from official sources to October 1, 1777; amongst the Captains is John Graves Simcoe as of December 27, 1775, vice Joseph Greene, who (p. 39) sold out soon after arrival in America to take the rank of Major in the Regiment of Oliver De Lancy of New York, a leading Loyalist.

The following letter to his mother bears upon the movements mentioned in the Text.

“Boston, March 13th, 1776.

My dear Madam:—

Perhaps this is the last letter I shall write to you from Boston as we have entrained all our heavy stores and baggage, and wait, I believe, only for a farewell word to evacuate it. Gen. Howe has adopted this resolution, I believe, from our being likely to want provisions and not being willing to risk anything to the uncertainty of the sea. His last despatches from England bear date upwards of 5 months past, it is said. The rebels have performed the feat of throwing several shells and more shot in the town from Phipp’s farm opposite Barton’s Point, and from the heights below Roxbury. Two shots only have done any damage, the one breaking the leg of a boy; the other taking off the legs of 6 men of the 22nd Regmt., one of whom has since died. They in one night’s time fortified the Heights of Dorchester Neck with works not unworthy the Roman Republic. Gen’l Howe determined to attack them; Regmts. (of which the 40th was one) fell down the river in ships. They were to have landed opposite the Castle; the Light Infantry and Grenadiers of the Army were to have landed from Boston. The violence of the wind prevented the execution of this design that night, and the General laid it aside and immediately determined to quit the town and, as reported, to go to Halifax.

You have here a minute detail of our proceedings since our friends of the Fort returned. I hope they had a quick and pleasant passage. I purpose writing Mrs. Graves. Should we go to Halifax, which I rather fear than hope, and should I have a fortnight’s secession from duty, I will borrow the dates and write you a kind of journal of this uncommon blockade. We are not to burn the town from motives I think of the best policy. We are paying every attention to preserve it from plunder, and daily discoveries are made of stores, which evidence clearly if any testimony was wanting, how long they have been preparing for hostilities—Had I the description of Drewe I would endeavour to paint my present situation.

It is past two o’clock in the morning. I am Capt’n of our Picquet. In one corner of the room, on one-half of my bed made (luxury indeed!) of clean straw, lies an officer asleep, with his feet towards the fire. He snores, but not in one drone, but in several modulations. My bayonet is stuck in the table, the socket of which serves as a candlestick to a night light. One half of my chair is now burning in the fire, and the other, when I shall have finished this letter, will be applied to the same use, serving rather to light the room than to warm it, there being no want of fuel from a multitude of wooden houses, and coal. Underneath me is Capt. Bradstreets; on the same floor my Company repose, almost drowning the solo of my companion with a most anti-musical concert. Scattered in the room lie many excellent and valuable books, picked up in the street by my Sergeant, where they were thrown in the trunk that contained them, to form part of a barricade. (N. B. If my Sergeant can smuggle them on board I shall not see it as they belong to Percy Morton, whose anti-Christian name bespeaks a rebel. But there is an order for no more baggage to be carried on board.) I have now been 11 days on duty. I should once have felt some inconvenience from it and been sleepy, but I am accustomed to snatch a slumber for an hour or two at a time, so that the perpetual gnaw, as I may call it, that I have been on since the 19th of June last is not the least wearisome to me nor did I ever, I thank God, enjoy a more uninterrupted state of health. Four of us have just supt upon a fowl which was stolen from a young man who had the impertinence to have possession of two at this time, when all our provisions are on board.

I go in the Spy, a remarkable fine sailor. I will now sleep, burning the legs of my chair and applying its rush bottom first as a pillow and in case of necessity as a paper. Adieu.

14th. The wind and other matters unfavourable, so that we are not embarked and possibly may not for some days.

Yesterday’s order was “The troops that are to embark at the Long Wharf to march in two columns, the right column to be composed of 22nd, 65th, 52nd, 23rd, and 44th Regmts. Left column 17th, 45th, 63rd, 35th and 38th Regiments. Brigadier-Gen’ls Robinson and Grant.

The troops to embark at Hancock Wharf to march in one column. The 43rd, 47th, 40th, 10th and 55th—Brigadier Gen’ls Jones and Smith.”

15th. The wind against us. Though the rear guard took the . . . . . . which consists of the light infantry, Grenadiers 4th and 5th Regiments. The Jonathans very quiet.

16th. Rainy weather, probably changing. We are ordered to be in readiness at the . . . . . to-morrow morning. A very great fire in the camp last night. Their barracks appear to have been on fire.

17th. About 7 this morning the whole column embarked, fell down the river, evacuated Charlestown and the lines in sight of the enemy, entrained, none daring to molest us.

18th. At anchor, the wind being not fair—the glass—it is much too long—a glass in a . . . . . case with screws made by Adams in Fleet Street . . . . . strong. If I have time I will write again. If not . . .

Believe me, &c.,

J. G. Simcoe.”

The following letter was almost certainly to Mrs. Graves.

“Kings Road, Boston, March 19th, 1776.