* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Gallant Gentlemen

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: E. Keble Chatterton (1878-1944)

Date first posted: Feb. 16, 2017

Date last updated: Feb. 16, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170217

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| BOOKS ON THE SEA |

| BY |

| E. KEBLE CHATTERTON |

| SAILING SHIPS AND THEIR STORY |

| SHIPS AND WAYS OF OTHER DAYS |

| FORE AND AFT: THE STORY OF THE FORE AND AFT RIG |

| THE STORY OF THE BRITISH NAVY |

| KING’S CUTTERS AND SMUGGLERS |

| STEAMSHIPS AND THEIR STORY |

| THE ROMANCE OF THE SHIP |

| THE ROMANCE OF PIRACY |

| THE OLD EAST INDIAMEN |

| Q-SHIPS AND THEIR STORY |

| THE ROMANCE OF SEA ROVERS |

| THE MERCANTILE MARINE |

| THE AUXILIARY PATROL |

| WHALERS AND WHALING |

| CHATS ON NAVAL PRINTS |

| THE SHIP UNDER SAIL |

| BATTLES BY SEA |

| SHIP MODELS |

| STEAMSHIP MODELS |

| SEAMEN ALL |

| WINDJAMMERS AND SHELLBACKS |

| THE BROTHERHOOD OF THE SEA |

| CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH |

| OLD SHIP PRINTS |

| VENTURES AND VOYAGES |

| OLD SEA PAINTINGS |

| ON THE HIGH SEAS |

| ENGLISH SEAMEN AND THE COLONISATION OF AMERICA |

| THE SEA RAIDERS |

| THE BIG BLOCKADE |

| GALLANT GENTLEMEN |

| THE KÖNIGSBERG ADVENTURE |

| CRUISES |

| DOWN CHANNEL IN THE VIVETTE |

| THROUGH HOLLAND IN THE VIVETTE |

| THE YATCHSMAN’S PILOT |

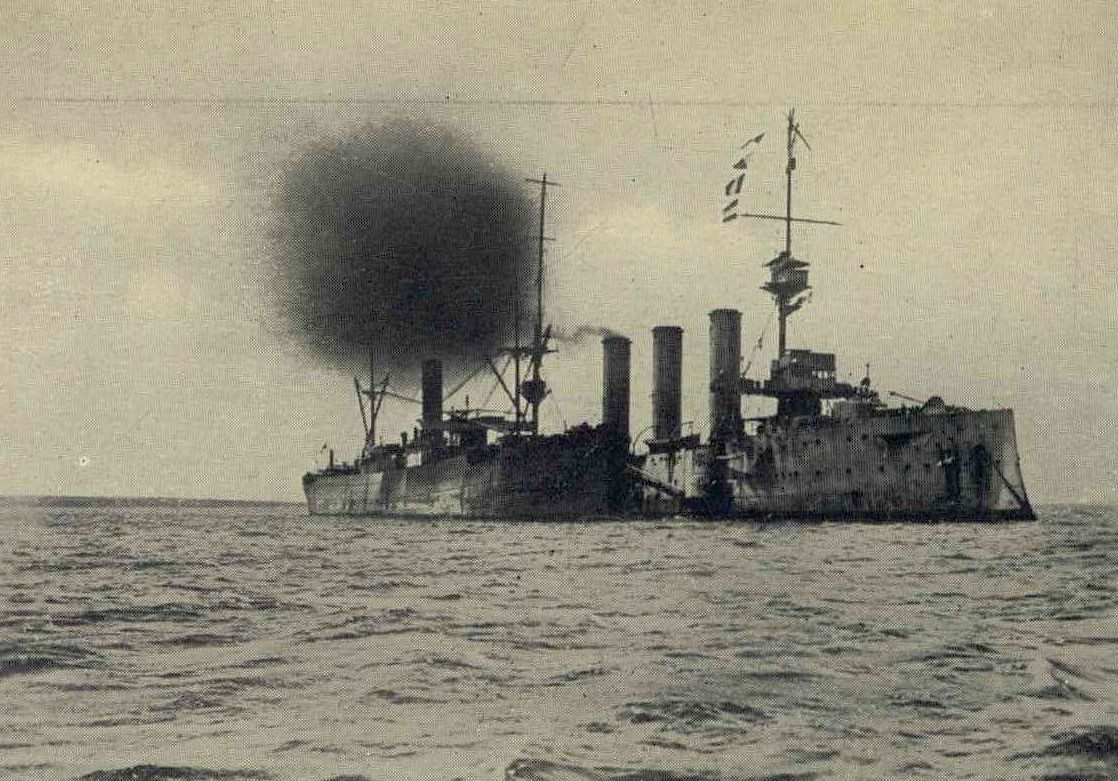

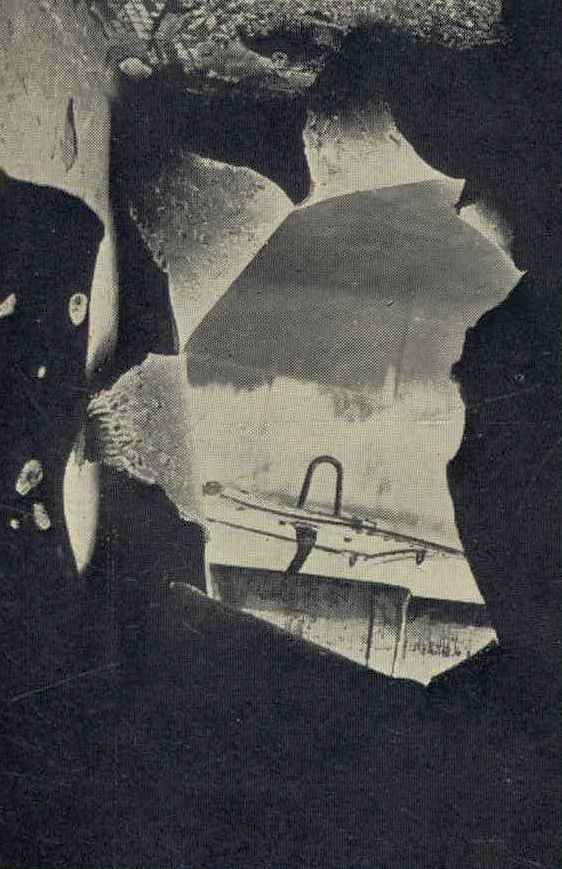

AFTER THE FALKLANDS BATTLE

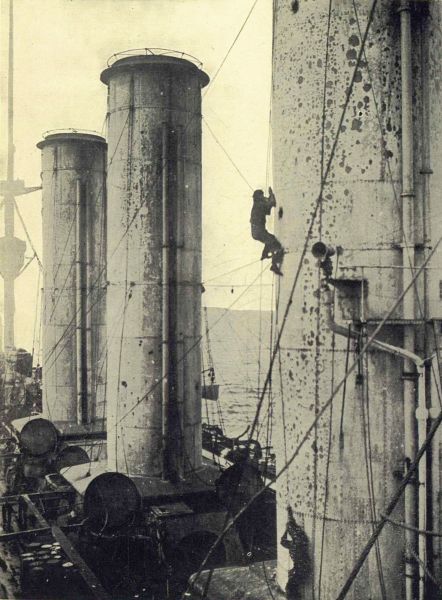

Showing the condition of H.M.S. Kent’s funnels after

hard steaming and hard fighting against the Nürnberg.

(See Chapter V.)

GALLANT

GENTLEMEN

By

E. KEBLE CHATTERTON

AUTHOR OF

“THE SEA-RAIDERS,” “THE BIG BLOCKADE,”

“THE KÖNIGSBERG ADVENTURE,” ETC.

WITH 31 ILLUSTRATIONS

AND 5 MAPS

FIFTH IMPRESSION

HURST & BLACKETT, LTD.

LONDON

First Published September 1931

Printed In Great Britain at

The Mayflower Press, Plymouth. William Brendon & Son, Ltd.

1933

For the sources of authentic history such items as private diaries, personal narratives, letters, and actual conversations with those who played the principal parts in their great events, are not merely of permanent value but the most reliable of all material.

The following pages of naval history, dealing with outstanding features of recent occurrence, may seem at times to be fiction and incredible: yet they are plain, uncoloured truth derived almost exclusively from the four sources just indicated. Here, indeed, are faithful records with the thrill left in. The background is the sea and modern ships, the chief characters are still happily alive, their memories keen and fresh. The result is that we have a personal illumination of unforgettable incidents, and no amount of self-effacement can prevent the revelation of a veritable galaxy of gallantry. These battles of brains and bravery, the narrow escapes from death, the exciting adventures, are remarkable for their test of grit, good judgment, coolness, courage; but they are so full of curious twists and surprises, that it would have been a pity not to have collected the stories before death has closed eloquent lips, or time’s rude hand has destroyed priceless documents already yellowing with age.

Here, for example, we get at the reason why the Goeben and Breslau escaped; the cause of the Coronel disaster: the thrilling chase and sinking of Nürnberg at the Falklands are given by the principal eye-witness, whose mind directed the very operations. Similarly, the first-hand narrations of the smaller ships’ duels, which occasionally read (as one distinguished Admiral expressed it), “like fairy tales,” are more full of dash and action than any imaginative writer would dare to place in a novel. Had we waited a little longer, it might have been too late. There is so much humanity, so much that is a lesson for posterity, contained in these chapters that it seemed highly to be desired there should be even a reopening of closed doors for the admittance of new evidence and a flooding light.

I have to acknowledge the valuable and courteous assistance in regard to information and permission to use illustrations obtained from the following, to whom I would offer my fullest gratitude: Admiral F. W. Kennedy, C.B., Admiral John Luce, C.B., Vice-Admiral J. D. Allen, C.B., Captain F. E. K. Strong, D.S.O., R.N., Lieutenant-Commander G. C. Steele, V.C., R.N., Lieutenant-Commander F. Capponi, R.I.N. (the Italian Naval Attaché in London), the Imperial War Museum (particularly for many of the photographs), and Messrs. John I. Thornycroft & Co., Ltd.

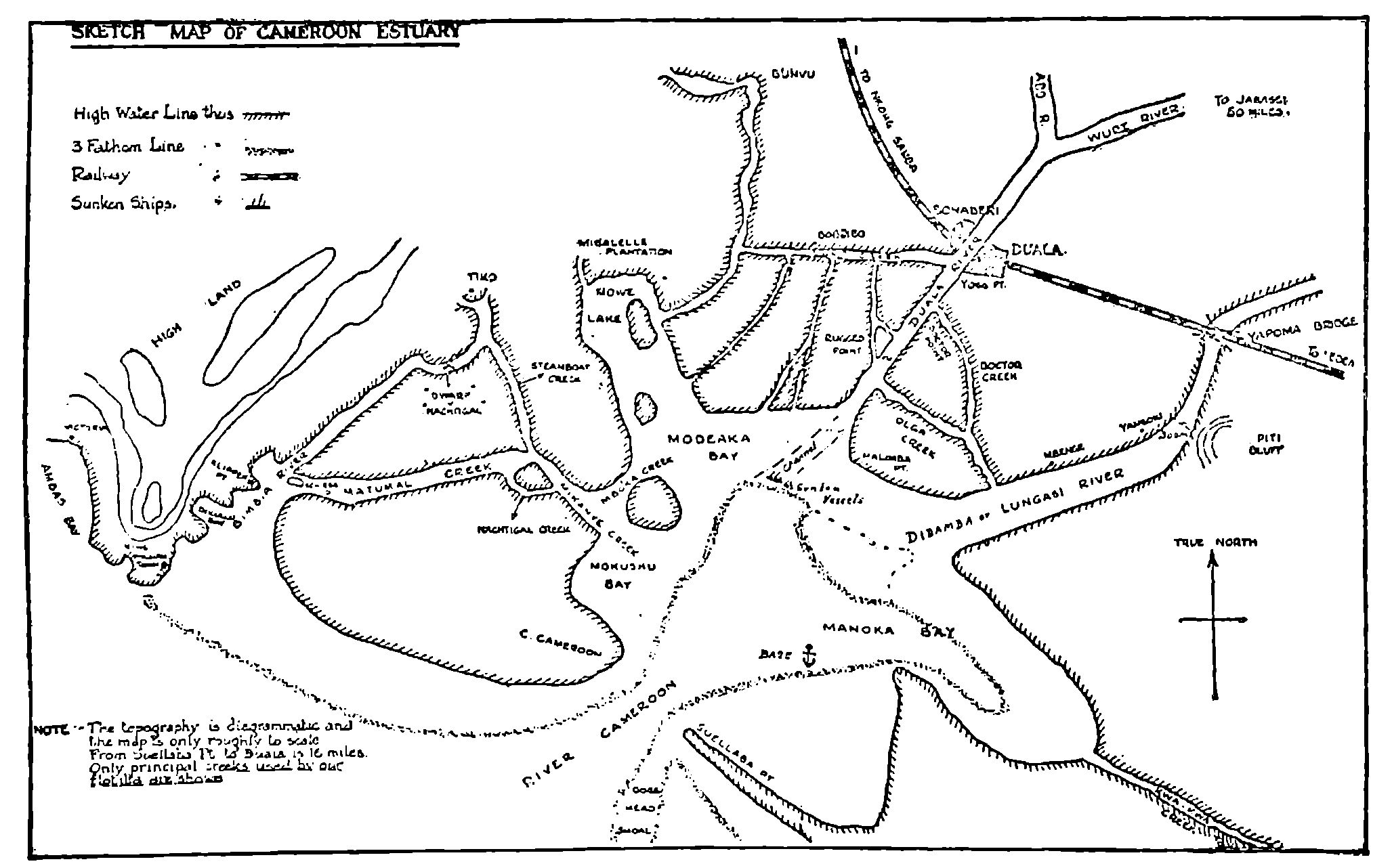

The map of the Cameroon estuary is reproduced by kind permission from The Great War in West Africa, by Brigadier-General E. Howard Gorges, C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O.

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | 5 | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | Why the “Goeben” got away | 11 |

| II. | The Dummy Fleet | 43 |

| III. | Cruisers at Coronel | 66 |

| IV. | The Approach to Battle | 85 |

| V. | Duel to Death | 102 |

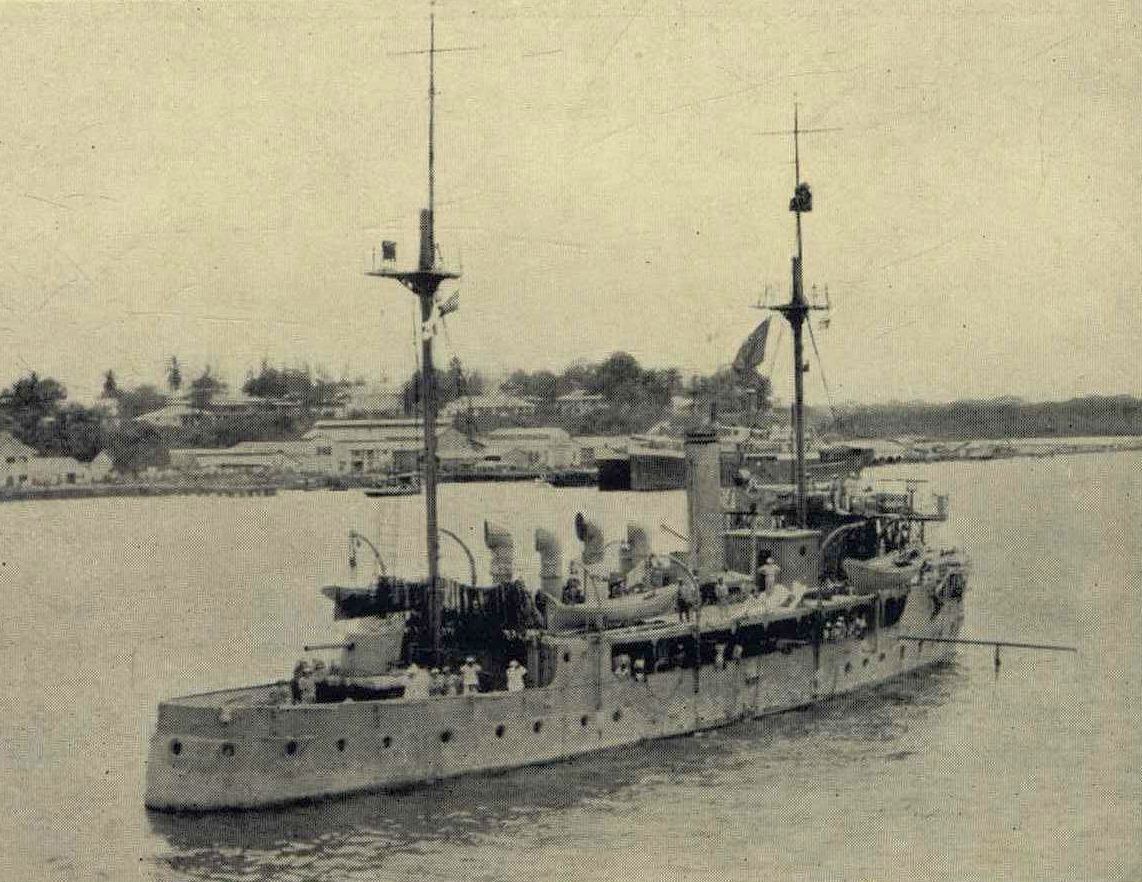

| VI. | The Adventures of “Dwarf” | 128 |

| VII. | The Decoy Steamer | 146 |

| VIII. | The Gallant “Baralong” | 161 |

| IX. | The Dive to Death | 179 |

| X. | The Gate Crashers | 192 |

| XI. | Boom Jumping | 208 |

| XII. | The Incredible Adventure | 224 |

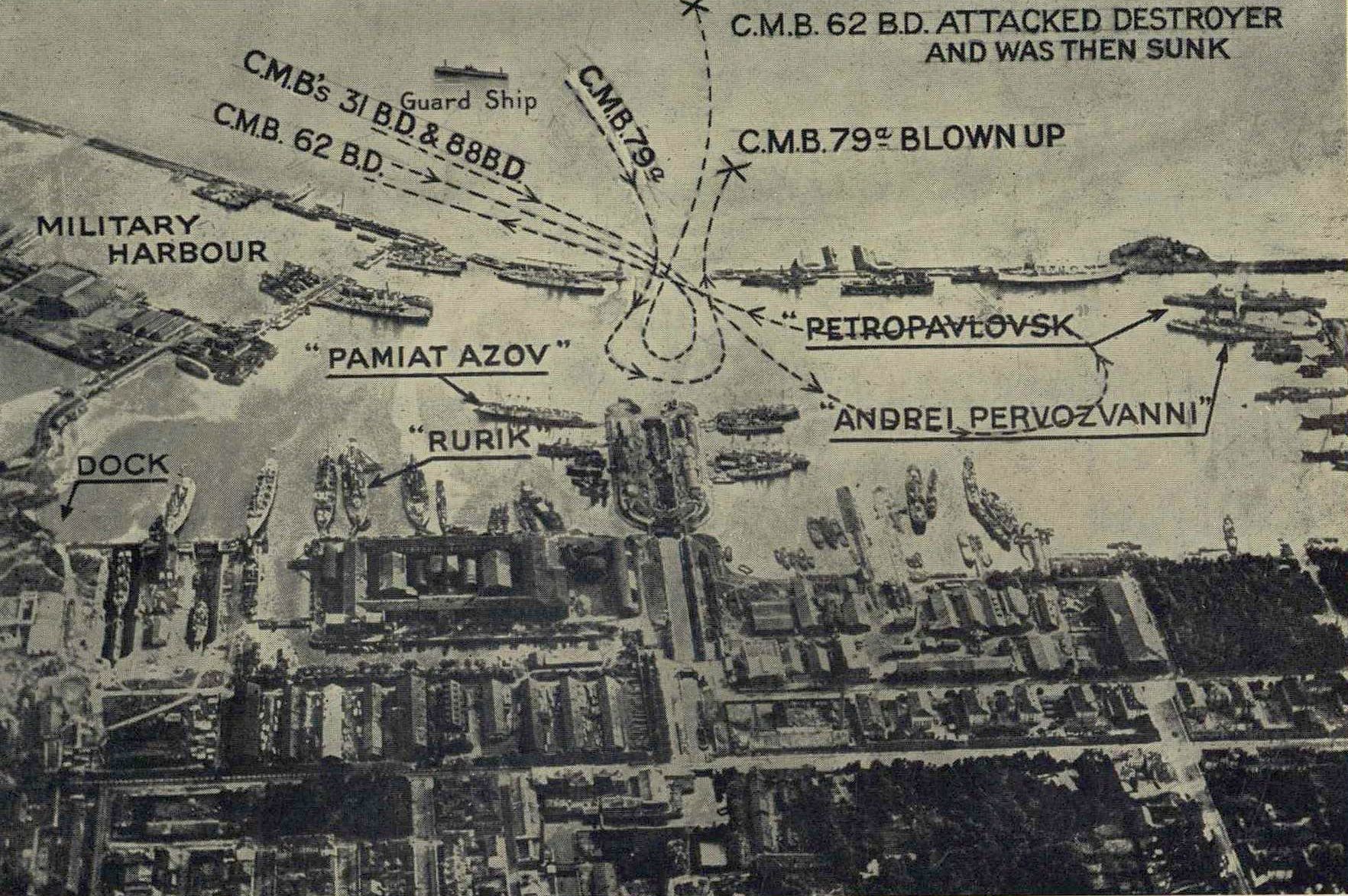

| XIII. | Dashing into Kronstadt | 246 |

| XIV. | Plain Piracy | 266 |

| Index | 289 |

GALLANT GENTLEMEN

IN the world’s history of the last few hundred years, few minutes have been so decisive as that period which passed away between 9.40 and 10.10 on the morning of August 4, 1914.

Now that we are able to look back on events from a sufficient distance, and to sift the facts which have poured in from all sides, it is permissible to draw the following conclusions. No one at the time could have been so far-sighted and prophetic as to have suspected that within this half-hour it was determined that Russia should become isolated from the influence of Western Europe and driven into Bolshevism; that Germany should be allowed to drag Turkey into the impending war, and thus be the direct cause not merely of the wasteful Dardanelles campaign, but of the costly hostilities in Mesopotamia. The spread of unrest and revolution through Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Spain, upsetting thrones on its way, extending even through Egypt to India, and not omitting to have some influence in Great Britain, France, and the United States, is all traceable to a sea event in the Mediterranean on that summer’s morning.

But this is a volume of exciting and gripping gallantries, not an inquiry into political consequences: yet the influence of sea power on history is largely expressed by the great dramas when ships and men have been at death-grips. There have been, however, some occasions when the mind, rather than force, has been on the verge of winning a great victory, only to be thwarted at the last by some curious defect in the controlling system, some failure in the details of its working. Strategy, whether on the sea or land, in sport or commerce, is the art of seizing situations and bespeaking positions or opportunities, so that all is favourable for putting a plan into execution. Checkmating in itself is a mental delight, and the most brilliant victory is that when the enemy sees himself already beaten by his rival’s superior forethought before ever a shot need be fired.

The memorable contest in which the Goeben and Breslau were the principal figures is pretty well unique because it lasted for eight days; the opposing parties were at no time very far distant from each other, yet never was there a serious engagement, and only the briefest action. Nevertheless this week, with its vacillations on both sides, definitely gave to the story of nations a permanent twist. It is illuminative to witness the shortcomings of politicians both British and German, the mistaken and narrow ideas of the higher command through lack of historical study, the ignoring of the main objective whilst being hypnotised by the importance of an inferior consideration, the lack of cohesion in the various departments, an inability to view the problem as a whole rather than a series of parts; but, finally, a defective organisation in regard to communications.

How was it that two German ships, the battle-cruiser Goeben and the small cruiser Breslau, went west and east up and down the Mediterranean as they pleased, and finally got away safely up the Ægean into the Bosphorus in spite of a British Fleet comprising three battle-cruisers, four armoured cruisers, four light cruisers, as well as destroyers and submarines; and a French Fleet which included twelve battleships, six armoured cruisers, four older ships, destroyers and submarines? If this immense force in one sea could not sink two enemy units, there must obviously be something wrong in the policy, strategy, communication of orders, or some unsuspected item. It cannot wholly be a question of luck.

Now during the last decade this break-through has been considered from more than one angle, and a vast controversy has arisen. Recently, however, we have been given the official German version; but I have had placed at my disposal the story as seen from the bridge of the senior British battle-cruiser Indomitable, and thus, by supplementing these with other authentic accounts, it is possible at last to get through the fog into a clear understanding of what actually happened, and why. Even after monographs have been published, interesting and valuable data still keep accruing, which make the mosaic as nearly perfect as we can hand on to posterity.

Apart from the dramatic poet Emil Ludwig (who published Die Fahrten der Goeben und der Breslau in 1916), and one of Goeben’s junior officers Leutnant zur Zee Kraus (who published Die Fahrten der Goeben im Mittelmer in 1917), and one of Breslau’s officers Ober-Leutnant zur Zee Donitz (who published Die Fahrten der Breslau in 1917), we have the narrative by Admiral Souchon himself, as seen from the Goeben’s bridge, written in Unsere Marine im Weltkrieg 1914-1918 under the general editorship of Admiral Eberhard von Mantey. Published in 1927, this personal account together with the official Der Krieg Zur See provides a very fair appreciation: but it is the viewpoint from the Indomitable which will especially and particularly aid us in witnessing the British aspect.

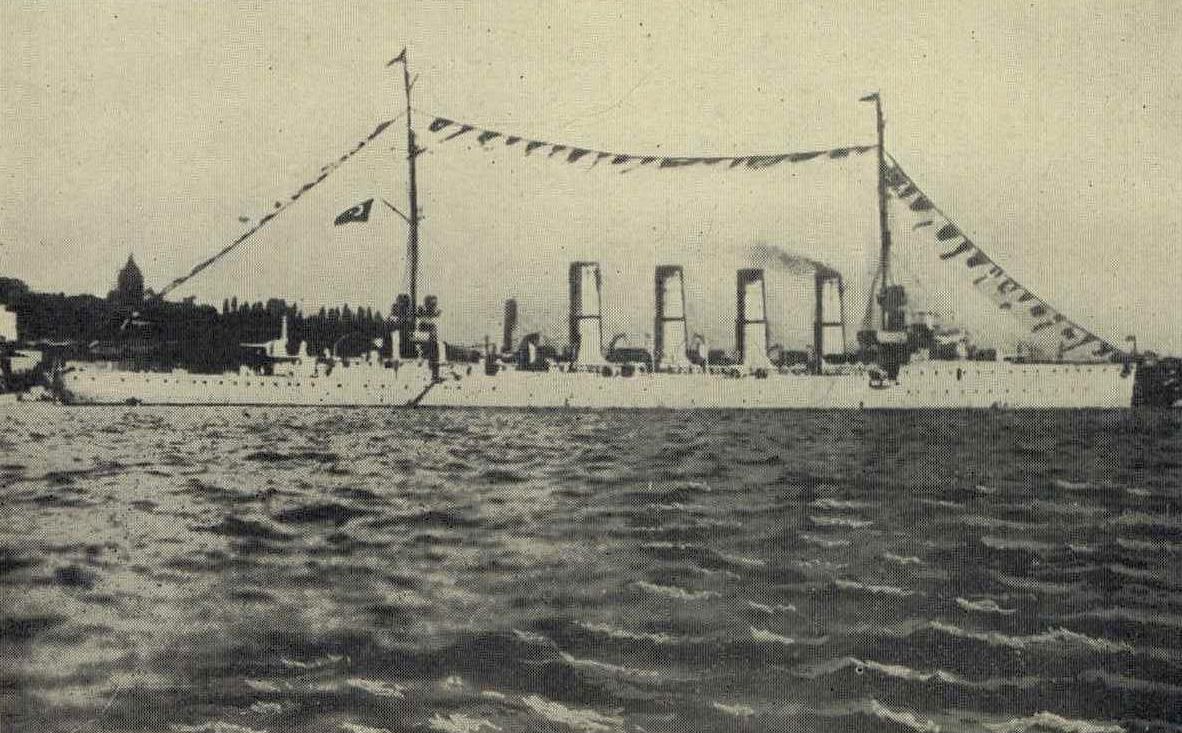

As to the rival Commanders-in-Chief, we have to think of Vice-Admiral Souchon as one who was every inch a naval officer but also something of a statesman: one who would have made an astute Minister for Foreign Affairs. His fine strong face, clear cut, clean shaven, with a firm mouth, cleft chin and distinctive nose, suggested the senior officer accustomed to handling big occasions with confidence. He had been in command of the Mediterranean Division for nearly a year, and at Constantinople he was a considerable personality among the Turks. I have been told on the best authority that on one occasion when lying off that capital a few months before the war he gave a dinner party at which British naval officers were present; at the end of the evening he asked the Captain of a certain British cruiser to remain behind and then told the latter that he was in the Bosphorus with the hope of selling the Goeben to the Turks as she was drawing 1½ feet more than her designed draught, and consequently with a loss of 3½ knots in speed.

Whether this was dust in our eyes, or a statement of fact, it was not forgotten when hostilities were opening: but it is true that in June 1914, the Goeben was steaming very unsatisfactorily, that 14 knots was her best continuous speed and 20 knots possible for only short bursts. So she was retubed, after the murder of the Archduke Ferdinand at the end of June suggested complications, and here we perceive the far-sightedness in looking weeks ahead to a likely logical political conclusion. She could now do her 24 knots.[1] On July 31 she had come down from Pola to Brindisi where she was joined by the Breslau, whence they proceeded to Messina, arriving there on August 2.

As recently as March 1914 Admiral Souchon and Admiral Hans (Commander-in-Chief of the Austrian Navy) had agreed that in the event of the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria, Italy) being at war with the Dual Alliance of France and Russia, Admiral Souchon should at once attack the transport of the French Army from Algeria, and that Messina was to be the Triple Alliance Navies’ rendezvous. This then explains why the Sicilian port from the very outset became of prominent value, even though Italy was for a time a doubtful ally but eventually came over to the opposite side, and Austria delayed showing her intentions for a few days. When on August 2 Admiral Souchon had coaled at Messina and received news that war with France was imminent, he waited not for orders but left that night at 17 knots, then steered west in order to arrive off the Algerian coast during the early morning and harass the French by shelling transports and transport gear. On the way he heard about 6 p.m. on August 3 that war had broken out with France, and twelve hours later the Goeben was off Philippeville bombarding the harbour works, whilst the Breslau had shelled Bona harbour works, and did certainly delay the transports for three days from leaving Algeria for southern France. Thus, by reasonable anticipation, Souchon had wasted no time in dealing a notable blow.

Now at 2.35 a.m., August 4, that is to say before reaching the Algerian coast, Souchon received a wireless message from Nauen, Germany, that the Goeben and Breslau were to proceed immediately to Turkey, a Turco-German Alliance having just been concluded. That meant steaming 1500 miles eastward, but Goeben still had boiler defects and needed more coal, so Souchon decided to call first at Messina again. We will therefore leave her for an interval steaming from the north African coast towards Sicily.

At Malta Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne, Bt., G.C.V.O., K.C.B., was in command of the British naval forces, an officer who had been a great personal friend of Queen Alexandra, an admiral who (like the name of his flagship Inflexible[2]) was rigid in character, most firm in his decisions. This battle-cruiser, like her sisters Indomitable and Indefatigable, was of 17,250 tons, armed with eight 12-inch and sixteen 4-inch guns, as compared with the Goeben’s 22,600 tons, ten 11-inch, twelve 6-inch guns and nominal 29 knots. The German thus had an individual superiority to either of these ships in size, speed, range, and weight of shell. Only a Lion or Queen Mary would have been her match.

On July 24 the Indomitable went into Malta for a much needed annual refit that was now four months overdue. She had not been in dockyard hands since March 1913. But before this overhaul had barely begun, the political horizon looked ugly, bunkers had to be refilled, magazines replenished, and machinery brought back from the dockyard workshops. On Sunday morning, August 2, Admiral Milne sent for Captain F. W. Kennedy, the Indomitable’s commanding officer; at 2 p.m. he was ordered to raise steam for full speed, recall everybody to the ship; and at 9 p.m. she left Malta with Indefatigable temporarily under the orders of Rear-Admiral Troubridge, who had with him the three armoured cruisers Defence, Duke of Edinburgh, Warrior, and the light cruiser Gloucester, preceded by two divisions of destroyers. At 3.15 on the afternoon of August 3 the Indomitable and Indefatigable were detached in order to search for Souchon between Cape Bon (Tunis) and Cape Spartivento (South Sardinia); for, whilst we were not at war, the enemy was carefully to be shadowed.

The question suggested itself: how would it be possible for ships of several knots inferior speed to shadow the Goeben;[3] and was there any truth in the yarn about her drawing 1½ feet in excess and therefore being unable to do her 29 knots? Only time could answer those questions. But it was known that she had been at Brindisi on August 1, yet at 7 a.m. on August 3 the light cruiser Chatham, which had been sent to investigate the Messina Straits, reported that the enemy was not there. Then whither had they gone?

It may be well here to mention that the dominating official British idea responsible for the subsequent strategy was based on the firm belief that the Goeben and Breslau would operate not in the far eastern Mediterranean, but would either attack the French Transport line, Algiers-Marseilles, some 860 miles in length, and escape through the Gibraltar Straits; or, possibly, run back up the Adriatic to unite with the Austrians. It is to be noted that our authorities did not contemplate Admiral Souchon making Constantinople his genuine objective. The British Admiralty’s primary concern was the safe transit of the French Algerian Army Corps to Marseilles, and on July 30 Admiral Milne was ordered that “your first task should be to aid the French” in this.

But the weakness here lay, paradoxically, in rigidity. These orders were several days pre-war, the political situation was still fluctuating, the intentions of Italy and of Austria were still unknown, and the French Commander-in-Chief, Admiral de Lapeyrère, was altering the transport plan, postponing departures, and organising convoys. Moreover he did not (as we shall presently note) require British aid, but even offered to help us. Thus the three battle-cruisers of Admiral Milne were kept west of Sicily in accordance with the hide-bound plan, and this left an insufficiently barred gate through which Admiral Souchon would be free to break on his way to Constantinople. But the fault was not exclusively that the strategy remained inelastic and never kept up to date: the communication system between the French and British Admirals was seriously deficient. It was impracticable for the one to know what the other was doing as the situation changed. It was regrettable that on August 3, the eve of war, the day when the Goeben and Breslau were on their westward course to bombard Algeria, Admiral Milne was unable by wireless to get in touch with the French Admiral, and had to send a letter by the light cruiser Dublin which should have been employed on a more important duty.

In a highly disciplined organisation such as the Royal Navy, where a Commander-in-Chief of unswerving habit imparts Admiralty orders that have not kept pace with the developments; and the Foreign Office intelligence system has been unable to keep the Admiralty informed that a secret treaty had been signed on August 2 between Turkey and Germany; the whole value of obedience becomes jeopardised, and the perfect machine may revolve in the wrong direction. Whatever individual captains might infer privately from their own observations and being on the spot, it was useless and painful to see the whole weight of authority inclined west instead of east. But if only the secret treaty had been known in time, it would surely have made crystal clear the reason why Admiral Souchon was on August 4 steering east. And there was ample time to make such a concentration in the Ægean that he could never have reached the Dardanelles. It seems curious, too, that no provision had been made on the assumption that the enemy might go through the Suez Canal to assist their sisters in the East, or to go raiding as Emden and the East Asiatic squadron operated. Was it to be expected Souchon would tarry in the western Mediterranean, longer than a spectacular act of frightfulness, when the numerical strength of Britain and France was so preponderating? It is true that, unless Admiral Troubridge’s armoured cruisers could have chosen the range, Goeben could have knocked them out one after the other like ninepins; yet our light cruisers were all more powerful than, though not so fast as, Breslau. And, when the Admiralty on the afternoon of July 29 flashed out the “Warning Telegram,” would it not have been well to have stationed any vessel with wireless off Messina and Cape Matapan to keep the Commander-in-Chief, Malta, informed? But, again, our strategy was defensive rather than to seek out the enemy and sink him wherever he might be found.

Just before 9 p.m. on the night of August 3 the Indomitable and Indefatigable were raising steam for 22 knots, showing no lights, bound for Gibraltar Straits to prevent Goeben leaving the Mediterranean for the Atlantic; and so continued till after breakfast the next morning, ninety extra hands being sent below to assist the stokers. But at 9 a.m. came an extraordinary piece of information that the Germans early this morning had bombarded Dover. It seemed incredible. The respective Captains of Indomitable and Indefatigable suspected that “Dover” should read “Bona,” and twenty minutes later it was learnt that this supposition was correct.

So here was news indeed, and that whilst the two British battle-cruisers were still on their westerly course down the Mediterranean, the enemy a few hours ago were only a hundred miles ahead! It was reckoned that if Souchon was really bound for the Atlantic he would either have to ease down, or else coal at sea soon after reaching the longitude of Gibraltar. The immediate question aboard Indomitable was, therefore, whether to continue at 22 knots, or push on to Gibraltar Straits at full speed, the visibility at this time being about nine miles.

But then happened one of those great dramatic surprises; and the decisive minutes mentioned at the beginning of this chapter commenced.

“In a very few moments,” Captain (now Admiral) F. W. Kennedy, C.B., has been good enough to write, “the question of the Germans’ whereabouts was settled: for at 9.35 a.m. g.m.t., the Breslau appeared 2 points on our starboard bow. We were at the moment steering N.84½W., and she appeared to be steering N.E. by E. at a very high rate, having a large bow wave. One hardly had time to order ‘Look out for Goeben,’ when she was seen on our port bow, steering a bit more to her starboard; then Breslau probably about E. by N., also going fast. Almost as soon as she saw us, she altered course as if to cross ahead of us to the Breslau, but I altered to starboard, whereupon she apparently resumed her original course. We had sounded off ‘Action Stations’ directly Breslau was sighted, and I ordered sundry officers to go to their stations, the Commander and Lieutenant (N) amongst them. I also ordered that the guns should be kept trained to their securing positions; and, carefully, the Goeben was watched. Had she an Admiral’s flag? Were her guns trained on us? She at first was somewhere about 17,000 or 19,000 yards off. No sign of the Admiral’s flag, so no salute had to be fired, and she kept her guns fore and aft. We passed each other on about opposite courses, Breslau on our starboard side and Goeben to port of us. Speed of the Germans somewhere about 20 knots.”

Now just at this stage there arose quite a delicate point. It must be recollected that Britain and Germany were not yet at war with each other; that the Cabinet meeting in London had not yet given its fateful verdict; that not till after two this afternoon did the Admiralty inform all ships the ultimatum to Germany would expire at midnight, and no hostile act was to be committed before that time. Nevertheless both parties knew that in a very few hours the two pairs of ships would be at enmity. “Be prepared for hostile actions on the part of English forces,” was the wireless message which the German Admiralty had sent twenty-eight hours previously. Under these circumstances Admiral Souchon was ready to open fire when the ships passed each other; but, in order that nothing should be visible externally, the guns were left in their securing positions.

“Directly we had sighted the Goeben,” says Captain Kennedy, “the question ‘Has she an Admiral’s flag flying or not?’ was thoroughly investigated from the bridge; for had there been one, I of course had to salute it, by Regulations and Customs of the Sea. I had well considered the question, and I believed that the salute was very likely to be the cause of the German replying by shot and shell: for this I was fully prepared. But there was no such luck: for there was not a flag up.”

Now, precisely the same thought was passing through Admiral Souchon’s brain, who took the view that in any case the British would not be punctilious at such a moment. Nevertheless, it has been suggested in Germany that the Indomitable should have paid the customary respect to a flagship, and when I called Admiral Kennedy’s attention to this interesting episode, he gave a definite answer which should surely settle the matter for all time. “Perhaps,” he remarked, “you will believe me when I say that every sort of telescope, binoculars, as well as range-finders, etc., were on the Goeben—but not a sign of a flag was seen by anyone on board Indomitable or Indefatigable.”

Now supposing Captain Kennedy had anticipated orders and opened fire? The ships passed each other (according to the German official history) at about 9850 yards. If the Indomitable and Indefatigable were ever to have their chance, it was then and then only. During a few moments he had the opportunity, though not the authority, to send Admiral Souchon’s battle-cruiser if not to the bottom at least to incapacity. Looking back on the long chapters of events—the Dardanelles disasters, the Russian collapse, the thousands of lives and millions of pounds destined to be lost—it would have been better for the world that in this moment all four ships should have foundered as gallant victims. If ever there was a temptation, which would afterwards be rightly acclaimed as justly yielded to, it was at this mighty minute.

The position where the enemy had been sighted was Lat. 37.44 N., Long. 7.56 E.; or about fifty miles north and slightly east of Bona; for, after having bombarded the coast, Admiral Souchon had steered west (intentionally to deceive) till out of sight, and then turned north-east. It may be wondered that, since the width of the Mediterranean between the southern extremity of Sardinia and the northern coast of Africa is about a hundred miles, the rival forces did not miss each other; but the Captain of Indomitable, whilst obeying his Admiral’s orders, was employing his private judgment, and that judgment was still animated by the belief (pondered over for days) that the Goeben’s ultimate goal was not the western Mediterranean.[4]

Captain Kennedy at once wirelessed information of the meeting to Admiral Milne, then proceeded to shadow her at full speed; at 10 a.m. was turning round to port to get in astern of Goeben and Breslau who were opening out to the north; and the ding-dong chase had begun, but by 11.30 a.m. the Breslau was already out of sight from Indomitable and Indefatigable, though the Goeben was being held. The hazy weather, however, got worse and would occasionally obliterate the enemy. “The Germans, at times, from now on altered their speed very considerably,” Captain Kennedy noted. “I had to ease down to 8 knots on one occasion to keep my distance.” This at the time was rather puzzling. Why should a shadowed ship slow down? We now know from German sources that Goeben’s boilers were still giving her considerable trouble, yet Souchon was doing his best to maintain the belief that she was the fastest ship in the Mediterranean. Speed was being increased at a cost of boiler tubes and men. As in the Indomitable, so in the Goeben, seamen ratings had to be employed trimming coal. It was a severe strain in the Goeben; one man next morning was found dead in a bunker, tubes kept bursting, the speed would suddenly drop. Moreover, like the Indomitable, the Goeben badly needed a scrub; it was ten months since the latter’s bottom was cleaned.

Thus, whilst there were spurts when the German flagship’s engines were making revolutions for 24 knots, she was so foul that the average speed over the ground from 8 a.m. till noon was only 17 knots, but for the next eight hours it was 22.5 knots. The Indomitable, with her foul bottom and unfinished refit, was not able to exceed this. Ample distance had to be kept from the enemy, for even 6500 yards meant that the British were well within German torpedo range. Suspicion was roused when Breslau at 1.20 p.m. closed her Admiral, and the two ships began zigzagging. Captain Kennedy, thinking the enemy might be dropping mines, accordingly kept his ships clear of the Germans’ wake.

Now about 2.30 p.m. the light cruiser Dublin was sighted. After her visit to Bizerta, she had been ordered to proceed immediately at full speed in support of Captain Kennedy, and the Dublin with her additional knots was valuable in being able to get ahead. In fact at 6 p.m. she had an opportunity of engaging the Breslau, which had now parted company from the Goeben, having been detached by Admiral Souchon with instructions to hurry into Messina and there make arrangements for 1500 tons of coal to be ready for the Goeben. The position at this time was that the Indomitable was steaming as fast as she could, doing 22 knots, steering N.85 E., Indefatigable about a mile away on her port beam, the Dublin about six or eight miles away fine on the Indomitable’s starboard bow, whilst the German smoke could be seen in the far distance ahead. By 7 p.m., the Goeben with at least half a knot’s superiority over Indomitable, was just becoming to the latter invisible; so the Dublin had the duty of continuing to shadow, but at 9 p.m. the weather thickened and she lost contact with the enemy.

There now followed a period of anxiety for all Captains, friend or foe. What exactly was Italy going to do? Which side of the war would she enter? As the Germans approached Sicilian waters and tried to communicate by wireless, our battle-cruisers of course were doing their best to jamb messages to the shore stations. When the Germans off the north end of Messina Straits sighted Italian torpedo-boats ahead, there were “some minutes of extreme anxiety” on the part of our late enemies, says the German official history. Similarly, says Captain Kennedy, “I did not want to get near any Italian coast, as I still believed it possible the Italians would join in with Germany, and if I continued on too near Italian torpedo-boat destroyer stations—some were at Palermo and some at sundry other places—the Goeben might give my position away to them, and they be able to attack us easily.”

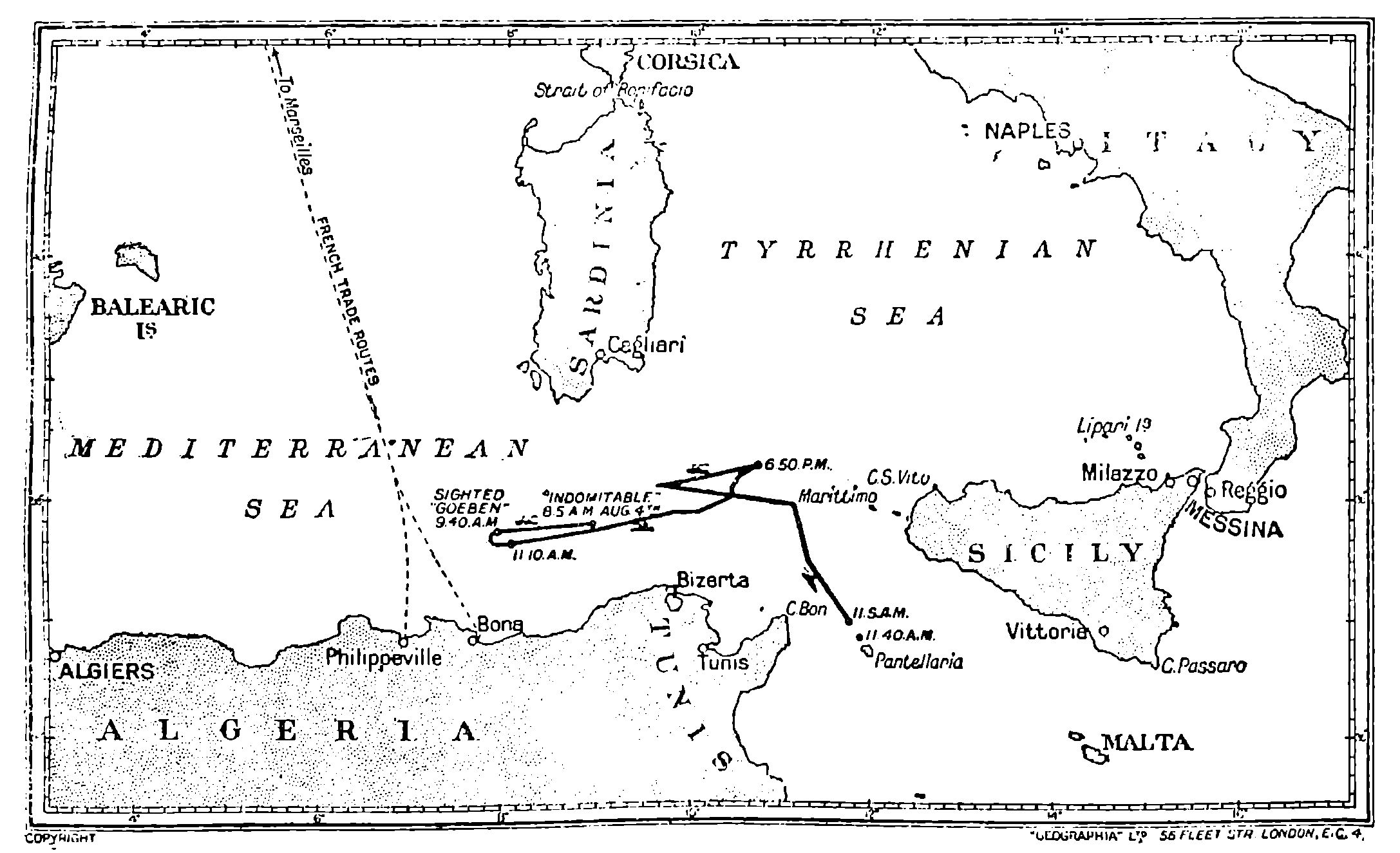

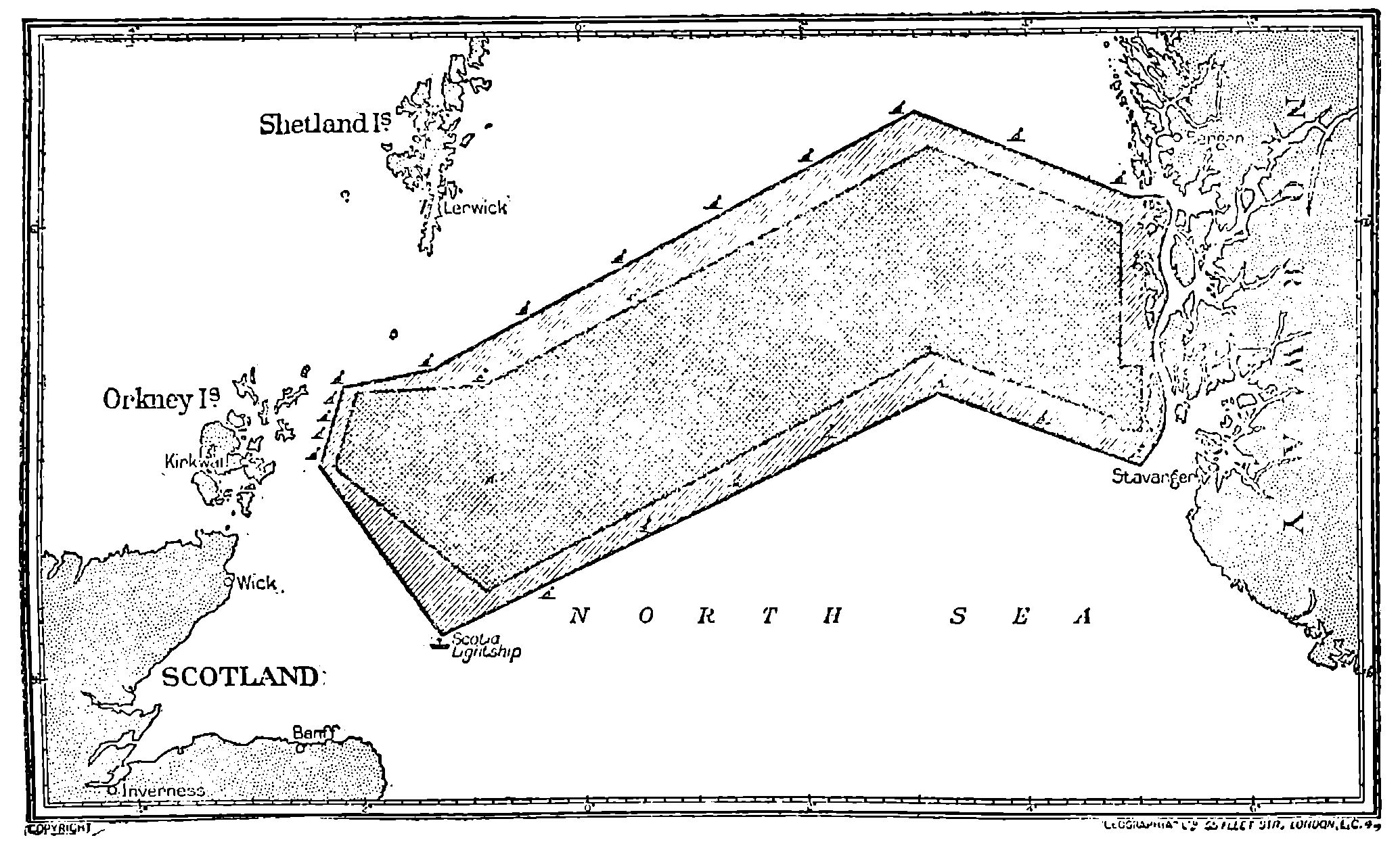

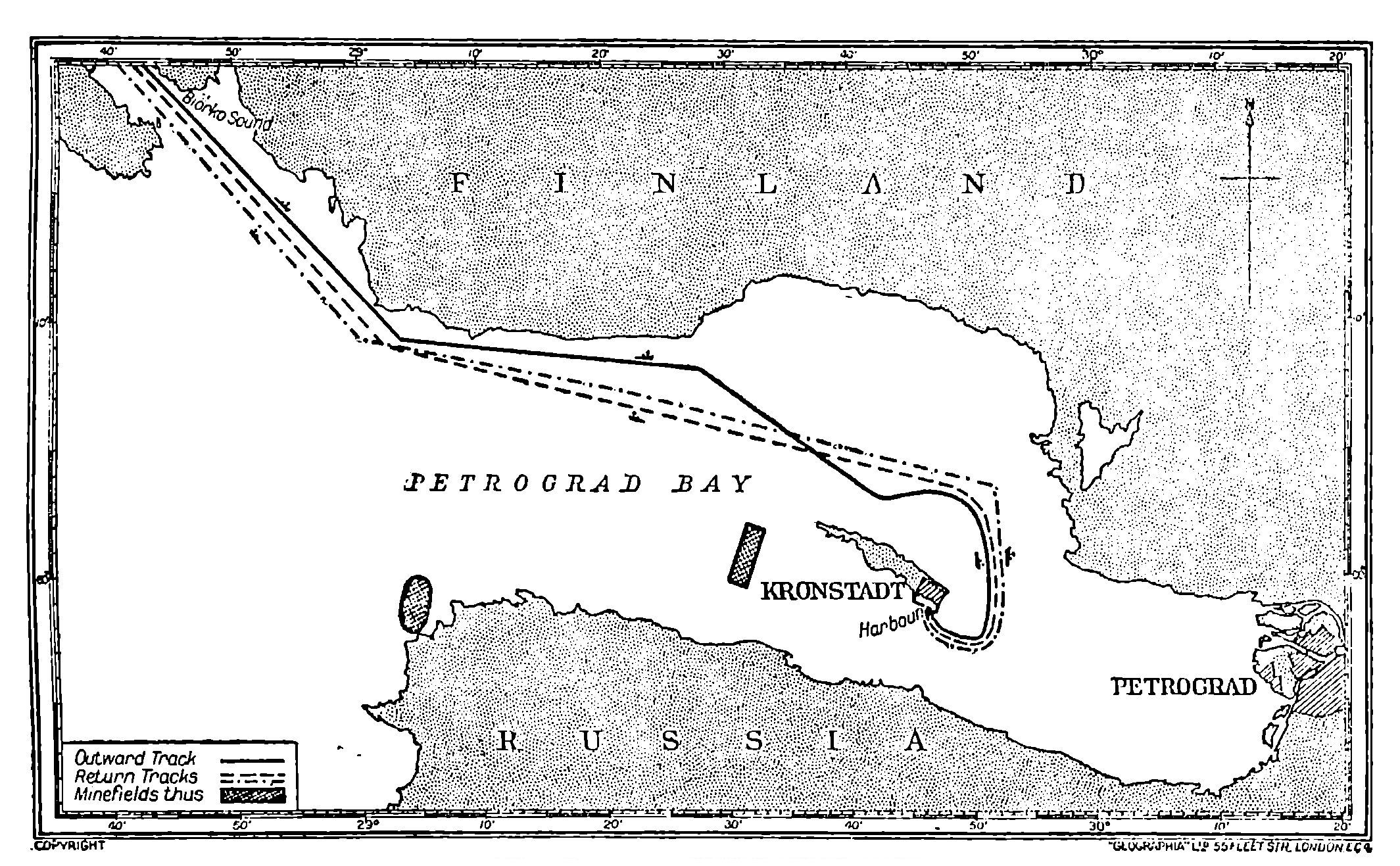

THE DAY OF DECISION

This shows the track of the British battle-cruiser Indomitable from 8.5 a.m. of August 4, 1914, to 11.40 a.m. of the following day. At 9.40 a.m. of August 4 she sighted the Goeben in Lat. 37.44 N., Long. 7.56 E., and at 10 a.m. was turning to port in pursuit of the enemy. At 6.50 p.m. the Indomitable was ordered to steam west. Next day, just before noon, she rejoined Sir Berkeley Milne off Pantellaria. The French Transport line will be seen well to the westward.

So he decided to patrol north and south that night clear of Italian waters and then sweep east at daylight along the north Sicilian coast, “for I strongly suspected that they would communicate with Vittoria[5] by wireless, and possibly coal off the coast of Sicily.” But just before 7 p.m., to his great surprise and disappointment, Captain Kennedy was ordered to steam west with Indefatigable at slow speed: so the two battle-cruisers now turned their backs on the enemy and jogged along at 7 knots. Admiral Milne was still impressed with the belief that the Goeben might turn westward, and the Dublin had informed Sir Berkeley that a German collier was waiting at Palma in Majorca, this news having been obtained on visiting the French Admiral at Bizerta. The British Commander-in-Chief was therefore still more inclined to think the enemy was not going to tarry off Sicily. Nevertheless, it was a curious situation that the chasers, only five hours before the ultimatum should take effect, were now going away from the chased. Next morning, the first actual morning of war, the battle-cruisers were ordered to concentrate with all despatch on Admiral Milne in the Inflexible, and this rejoining was effected before midday (August 5) off the island of Pantellaria.

Let us now go back to see Messina, in whose roadstead the Breslau let go anchor at five on the morning of this August 5, and just before eight o’clock was followed in by the Goeben with five Italian torpedo-boats ahead and astern. The Germans were badly in need of coal after all this hard steaming west and east, yet here was a neutral port and the period of hospitality limited. In order to appreciate the Teutonic thoroughness, we shall not forget that as early as July 10 the Goeben had begun preparing for war in feverish haste at Pola, the Kaiser having given his Navy and Army a month’s start of his enemies. On July 29 she had gone up to Trieste to coal, but did not complete: she was afraid lest war would burst on her whilst still well in the Adriatic, and that was why she steamed south to Brindisi, where Admiral Souchon came aboard.

On July 31 the officers were given special instruction in Prize Law, identity disks were served out, and preparations made for jettisoning all superfluous woodwork. When on August 2 the ships coaled at Messina, it was in spite of Italian protestations; but the German Ambassador in Rome had overcome the problem, and here three days later the same two ships, after bombarding French colonial ports, were back once more with the same greed for coal. Now the lie has been spread in Germany that this coal on August 5 was obtained from a British collier named Wilster through the influence of whiskey and bribery. It may therefore be well to state the true facts.

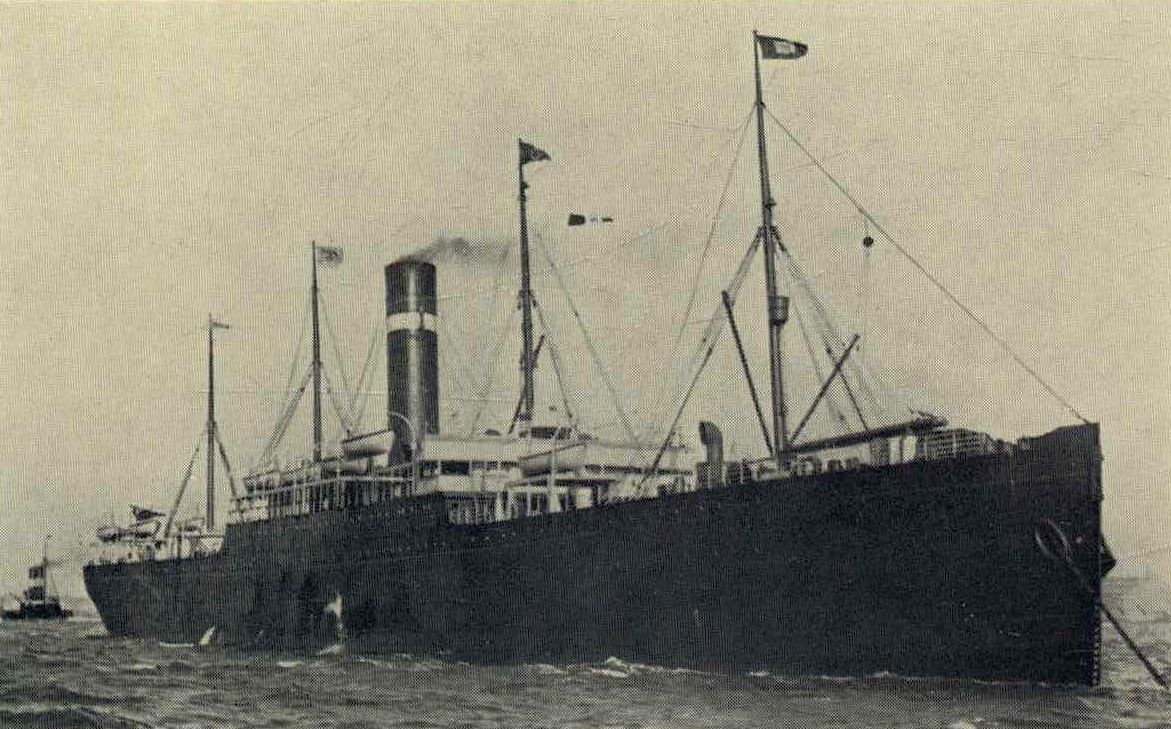

The S.S. Wilster, whose master was P. A. Eggers of Sunderland, left Penarth some days before the war bound with a cargo of Welsh coal consigned to the Hugo Stinnes Coal Company at Messina. The collier arrived off the entrance at sunset on August 4 and was met by a tug who ordered Captain Eggers to anchor in the roadstead, and come ashore next morning for instructions. Next day at 8 a.m. he was in his boat coming off when he saw the Goeben arrive and anchor near his ship, and it was only now Captain Eggers learned that war had broken out. He duly received from the consignees the order to bring his ship into harbour and moor alongside a coal hulk.

When he stepped out of his boat and was again aboard his ship, the Chief Officer informed him that a German naval officer during Captain Eggers’ absence had called and left a message instructing Eggers to bring the Wilster alongside one of the two German cruisers. This the British skipper refused to do, and brought his ship into harbour. He was still busy mooring, when a small boat arrived alongside, and a young German naval officer leapt aboard, mounted the bridge, requested Eggers to unmoor again, and take the Wilster alongside a German cruiser. According to a letter which Captain Eggers contributed to the press in February 1920, the young visitor attempted to push some money into the master mariner’s hand saying, “That is for you, Captain.” But the bribe was indignantly thrust aside, the young man was informed that Captain Eggers had nothing to do with the cruisers, and that the cargo was consigned to the Hugo Stinnes Coal Company.

Eggers then went ashore and called at the office, where he found the manager together with several senior German naval officers. The manager requested the Wilster’s master to go into the roadstead and coal the cruisers, but Eggers declined. The latter next interviewed the British Consul, who stated that England and Germany had been at war since midnight, and no coal was to reach the Goeben and Breslau. “On return to the coal office,” says Captain Eggers, “the German officers were still there, and I opened my mind and told them straight what I thought of their action.” The result was that our enemies did not get this British coal.

But we know that 1580 tons were put aboard the Goeben by 11.30 a.m. next day (August 6) and that just after midnight of August 5-6 the Breslau took in 495 tons. Whence were these supplies obtained? Eggers writes as follows:

“The coals procured at Messina by these ships came from the German East Africa liner General, which ship had arrived at Messina a few days previous; she was outward bound, and had worked night and day discharging her general cargo to get at coals which were stowed in the bottom of her holds, and I understood she had several thousand tons of coal on board; they also commandeered the bunker coals of one of the North German Lloyd boats, which had taken refuge in Messina.”

According to the German official history, the Goeben received her coal from the General, the Hansa liner Kettenturm, and the Hamburg-Amerika liner Umbria, as well as from lighters belonging to the Hugo Stinnes Coal Company’s depot; the Breslau coaled from the Umbria, the Hamburg-Amerika liner Barcelona, as well as the Hugo Stinnes lighters. But the statement is added that some of the Stinnes coal had first to be discharged into lighters from the “English steamer Wilster, and then to be brought alongside”; that in spite of the British Consul’s efforts, the Stinnes agent succeeded in placing the coal at the disposal of Admiral Souchon.

Of course the British Consul telegraphed news of the Germans’ arrival at Messina, but the Dublin had been sent back to Malta to coal, and thence was despatched with two destroyers to join Rear-Admiral Troubridge at the approaches to the Adriatic. According to Admiral Milne’s own monograph,[6] Sir Berkeley on August 4 received the report that the General had landed her passengers at Messina and was remaining. On the 5th he knew that the Goeben and Breslau were within the Messina Straits. Now the distance from Malta to the southern exit of these Straits is less than 150 miles. Lying at Malta were three small British submarines, viz. B 9, B 10, and B 11. What a glorious opportunity these might have seized, if they had been towed till nearly up to six miles from the Italian coastline, and there left to await Admiral Souchon’s emergence! It is true that the light cruiser Gloucester was watching this very spot, yet the Goeben was capable of blowing her out of the water; the ratio being ten 11-inch and twelve 6-inch guns as opposed to two 6-inch and ten 4-inch. Moreover the Breslau with her twelve 4.1-inch guns intensified the formidability. But torpedoes in the narrow waters off this defile would have had almost ideal conditions.[7]

It is established that the French were far from nervous lest the enemy should come west, for late on August 6 the former offered to lend Admiral Milne four cruisers. On this date the British Commander-in-Chief was cruising off the north-west side of Sicily with the Inflexible, Indefatigable and Weymouth, still expecting the enemy would come west and not east. And then, soon after 5 p.m. of this August 6, came that memorable wireless signal from the Gloucester that Goeben was coming out of the Straits followed by Breslau a mile astern and steering east. The fact that Admiral Milne did not now go in support of Gloucester, but went back to Malta for 900 tons of coal—her maximum stowage room being 2500 tons—has been much criticised. It is admittedly easy enough to be wise after the event, but, having made the error of assuming the enemy might come west by northern Messina entrance instead of east by the southern exit, there would have been a chance to make up for this by remaining at sea and at least injuring the Goeben before she reached the Dardanelles, and possibly of sinking the Breslau.

The Inflexible was back at Malta by noon of the 7th, and did not leave till half an hour after the following midnight, when the Indomitable, Indefatigable and Weymouth went with her, this time at last eastward bound. Thus over thirty hours had passed before any force at all commensurate with Goeben’s warlike strength was sent in pursuit of Admiral Souchon. And of course it was too late, though (as fate fashioned the Dardanelles affair) by the narrowest margin.

At Messina the Germans had a tough time coaling intensively amid the windless heat of a Sicilian summer’s day. Souchon, too, had his troubles and anxieties, so that it must have been a relief when he once more put to sea. The Italians were strictly neutral, and nothing but sheer strength of personality on the part of the German naval officers got over the difficulties in respect of coaling and provisions. Souchon appealed to the Austrian Admiral Hans to come down from Pola and escort him, but that flag-officer was not prepared to help: nor was Austria yet in the war.

Another anxiety was that no sooner had the German Admiral issued his sailing orders for the break-through to the Dardanelles than a telegram from the German Admiralty came announcing that for political reasons it was at the present impossible to arrive off Constantinople. So, just as the ancient seamen used to dread the Scylla and Charybdis of Messina’s Straits, so this modern seaman found himself threatened in a twofold manner: if he remained in Messina he would become interned, and if he went outside his enemies were awaiting him.

But he knew the Turks and their politics better than they knew themselves; he knew that the Turks would be influenced and mesmerised into practical alliance if they saw the big Goeben arrive. Souchon was very much a persona grata at Constantinople, and we must regard him as a gallant gentleman for his independent decision, in spite of everything, to reach the Dardanelles—British cruisers and Turkish politics notwithstanding. At present he was in a most lonely and perilous situation, but with unwavering moral pluck, and in spite of his defective boilers, he resolved to make the original attempt.

The Goeben left Messina at 5 p.m. on August 6, speed 17 knots, followed twenty minutes later by the Breslau. The General (as Captain Eggers witnessed) had painted out her name, and her funnel black. She departed at 7 p.m., having been ordered to make for the island of Santorin, which lies at the southern end of the Ægean some seventy miles north of Crete. The Goeben had barely got under way before she was sighted by the Gloucester (Captain W. A. Howard Kelly) an hour later. In accord with Admiral Souchon’s original intention, the Goeben made a feint to suggest that he was bound up the Adriatic, but by 10.30 p.m. she had reached her farthest north and thence in a south-easterly direction steamed towards Cape Matapan, the southern extremity of Greece, which for thousands of years had seen warships of all sorts row, sail, or steam, past her headland.

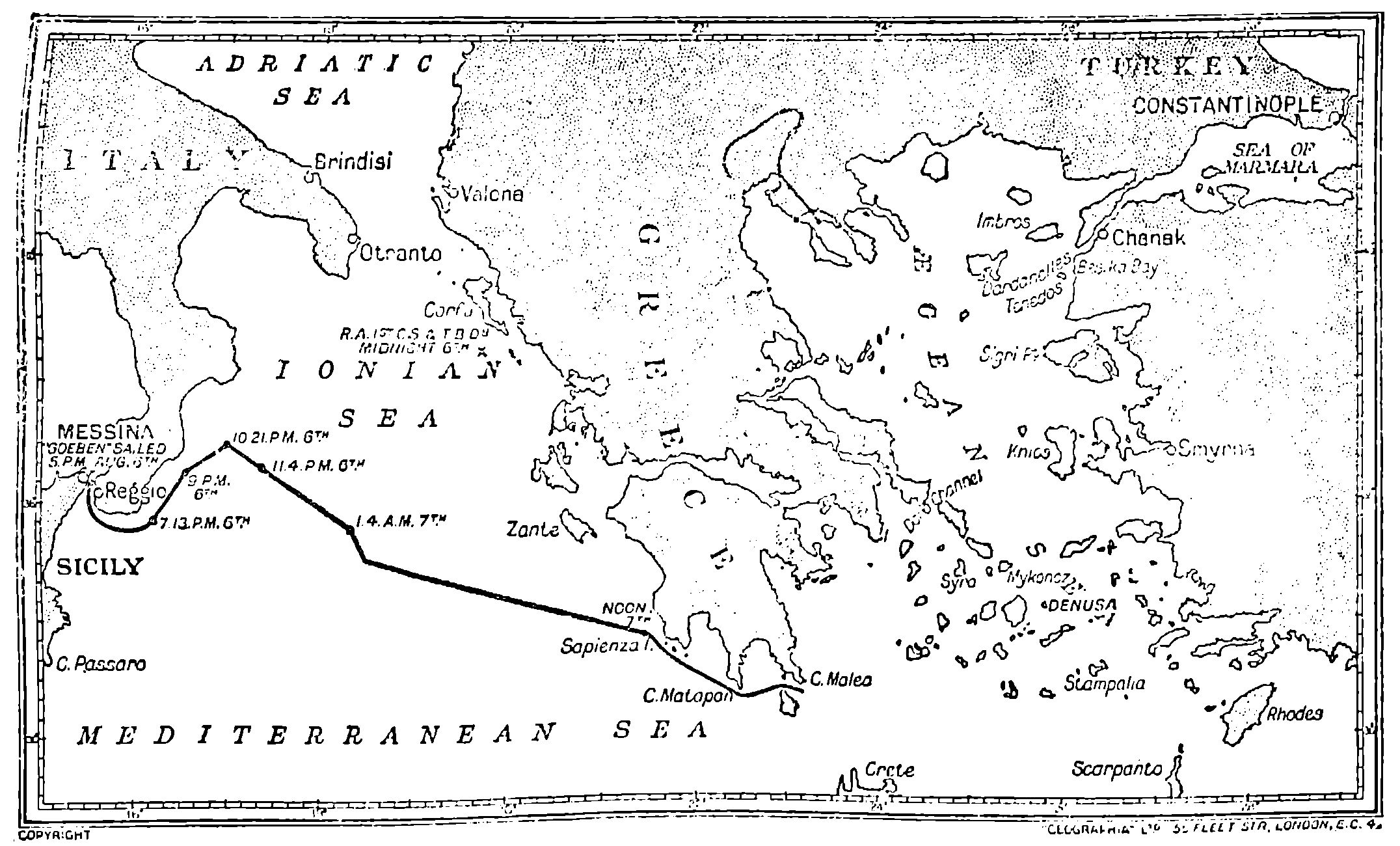

THE GREAT ESCAPE

This indicates the track of the Goeben from the time she left Messina on August 6 till she passed Cape Malea next day. The Island of Denusa, where the Goeben and Breslau coaled, will be seen to N.E. of Cape Malea. The position of Rear-Admiral Troubridge’s squadron is shown by a × below Corfu.

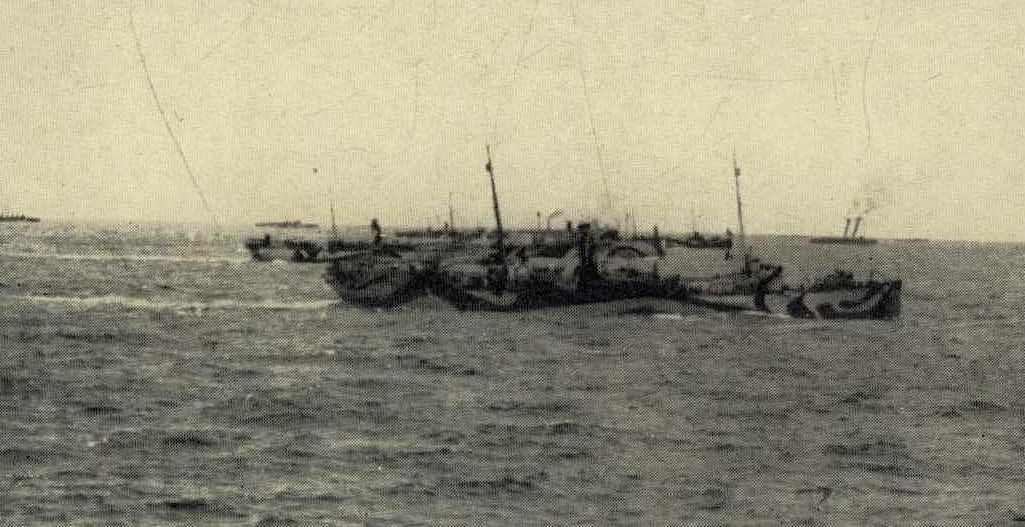

The night of August 6-7 was calm, clear and moonlit. Although these three British and German cruisers were to be in sight of each other most of the way to Cape Matapan, and the Germans did their best to shake off Gloucester’s unwelcome company, yet it led to no serious engagement. But why? The answer is that—as regards the Germans—(1) the 6-inch guns of Gloucester were regarded as superior armament to that of Breslau; (2) Admiral Souchon’s main objective was not to destroy, but to hurry towards the Dardanelles where he could do far more harm to the Allies’ cause by influencing Turkey, so driving a wedge between Russia and the Franco-British forces. On the other hand the Gloucester performed the true office of a light cruiser, which is to be the eyes and ears, the intelligence-gatherer, for the main fleet. Captain Kelly withheld his fire, “rightly considering it” (as Admiral Milne has written) “to be his first duty to follow the Goeben.”

Rear-Admiral Troubridge, with his four armoured cruisers Defence, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh, Black Prince, and destroyers was on the east side of the Otranto Straits ready in case the enemy had come up the Adriatic; but, having learned they had gone south-east, came down to intercept them, though later abandoned this intention, feeling that his primary duty was to remain on his allotted station. About 1 a.m. the light cruiser Dublin, with two destroyers bound from Malta to join Admiral Troubridge, sighted the Breslau, but turned away as she was seeking Goeben whom she hoped to torpedo. She failed to find the German battle-cruiser, so continued on her course to join Admiral Troubridge. Thus to Gloucester was left the solitary task of shadowing the enemy through the night.

Indeed, the one bright spot of this first week’s Mediterranean campaign from our side was the gallant skill with which Captain Howard Kelly (whose brother happened to be the Captain in Dublin) stuck to the enemy and harassed him by making one or the other unit keep turning back to shoo the Gloucester away. Solely with these tactics in mind did the British light cruiser at 1.35 p.m. (August 7) open fire on the Breslau at about 12,000 to 14,000 yards. This had the desired effect of causing the Goeben to turn back and open fire. It is admitted that the firing on both sides was good, but it was all over in fifteen minutes.

The chase then continued as before during three more hours, by which time Cape Matapan had been reached, but the Gloucester getting short of coal turned back in accordance with Admiral Milne’s orders and at 4.40 p.m. laid a course to join Admiral Troubridge. We now know that it was Souchon’s intention to reach the mountainous, wooded island of Cerigo (to the east of Cape Matapan) first, remain at the back of it hidden, let the Breslau lure the Gloucester on in action, and then Goeben would have come forth with a heavy fist.

Captain (now Admiral) Kelly received high commendation from the Admiralty, and decorations followed. His pertinacity won the admiration of the Germans and is still recognised universally as a model achievement in cruiser duties. Not till 4 a.m. of August 10 did Admiral Milne’s squadron round Cape Malea, which is just beyond Cerigo. The last phase of the great German escape therefore begins in the southern Ægean, and again it is full of difficulties for both contestants. So far the German Admiral had succeeded perfectly: by that good luck which so frequently accompanies courageous determination he had for the second time passed through the British net. But now his will, somehow or other, must compel the Turks to admit him through the Dardanelles into the Bosphorus, and he must hide until that insistence could metaphorically open the door. Meanwhile, after rapid and extravagant steaming from Messina, he needed coal.

There are two features of German overseas operations (as have been emphasised in a previous study[8]) which stand out in a remarkable manner. One is the excellent pre-war arrangement by which the Germany Navy abroad was nearly always able to find colliers waiting at the right time and place; the other is the manner by which they utilised to the full every geographical facility, and especially with regard to lonely islands. The S.S. General we have seen suddenly to change herself from passenger liner to auxiliary, and to be found rich with hidden coal at a critical date. Souchon kept in wireless touch and was able to send her on up the Ægean to Smyrna, where she arrived on August 9 without molestation, and was able thence to send the Admiral’s telegram by land-wire through to Constantinople. This was cleverly worded, and its purport was to obtain permission to pass through to the Bosphorus on the grounds that Russia must be attacked in the Black Sea. Knowing the hatred of Turkey for the Russians, this was an astute effort.

Souchon had concealed himself at the secluded Ægean island of Denusa,[9] so that he was now conveniently linked up with his objective via the General. To Denusa was directed a German collier from the Piræus disguised as a Greek coaster, and at the very time on the early morning of August 10 when Admiral Milne’s squadron was rounding Cape Malea, both the Goeben and Breslau were being coaled, but about two hours later resumed their voyage to the Dardanelles. For a telegram had come from Constantinople through the General giving the requisite Turkish permission. That evening the two German warships were inside the Dardanelles and being piloted by a Turkish torpedo-boat. Next morning the General arrived also. Admiral Souchon has referred to the period between his arrival in the Dardanelles and the end of October, when hostilities against Turkey began, as the most difficult in all the war from his personal standpoint. It was one thing to have had the secret treaty of August 2 signed: it needed the arrival of Goeben, Breslau, and Souchon’s personality to make Turkey positively hostile to the Allies and thus to render the Dardanelles impassable. Germany was not less surprised than we that the two cruisers reached Constantinople: indeed the Chancellor, Bethmann-Hollweg, could imagine only two alternatives. Either Great Britain intentionally withheld her hand, so as to prevent any decision which might prolong the war; or else there had been “a gigantic mistake of the British Admiralty.”

But, none the less, Admiral Souchon was in real peril all the while he was in the Ægean. At the time when Admiral Milne rounded Cape Malea, the Germans were only a matter of seven hours’ steaming to the north-eastward. To have taken them by surprise would have been impossible by day in any case: for the enemy had at once erected a signal station on the hill (as another of Germany’s commanding officers once did on Easter Island in the Pacific) to give due warning. Both the Goeben and Breslau had steam ready to proceed at half an hour’s notice. But, as we have seen, the departure from Denusa practically coincided with the entry of Admiral Milne into the Ægean off Cape Malea.

Having begun searching that many-island sea, a most difficult area for finding a lurking enemy, the Inflexible at 9.30 a.m., August 10 (relates the British Admiral), did intercept “wireless signals of the note and code used by the Goeben . . . but the direction could not be ascertained,” and early next morning the General’s wireless also was heard. Only at 10.30 a.m. (August 11), was the news to reach the Inflexible that quite definitely the two cruisers had slipped into the Dardanelles, and at 3 p.m. it was learned that the General was already at Constantinople.

The whole of this eight-day episode will ever be a subject for interesting discussion, and, whilst it accentuates the need for clarity, perfect co-operation, vision, adaptability, and aggressiveness rather than the attitude of waiting on the defensive; yet conversely there are permanent lessons to be remembered from the brave determination of both Captain Howard Kelly and Admiral Souchon, in their respective situations, that needed bold initiative yet prudent decision.

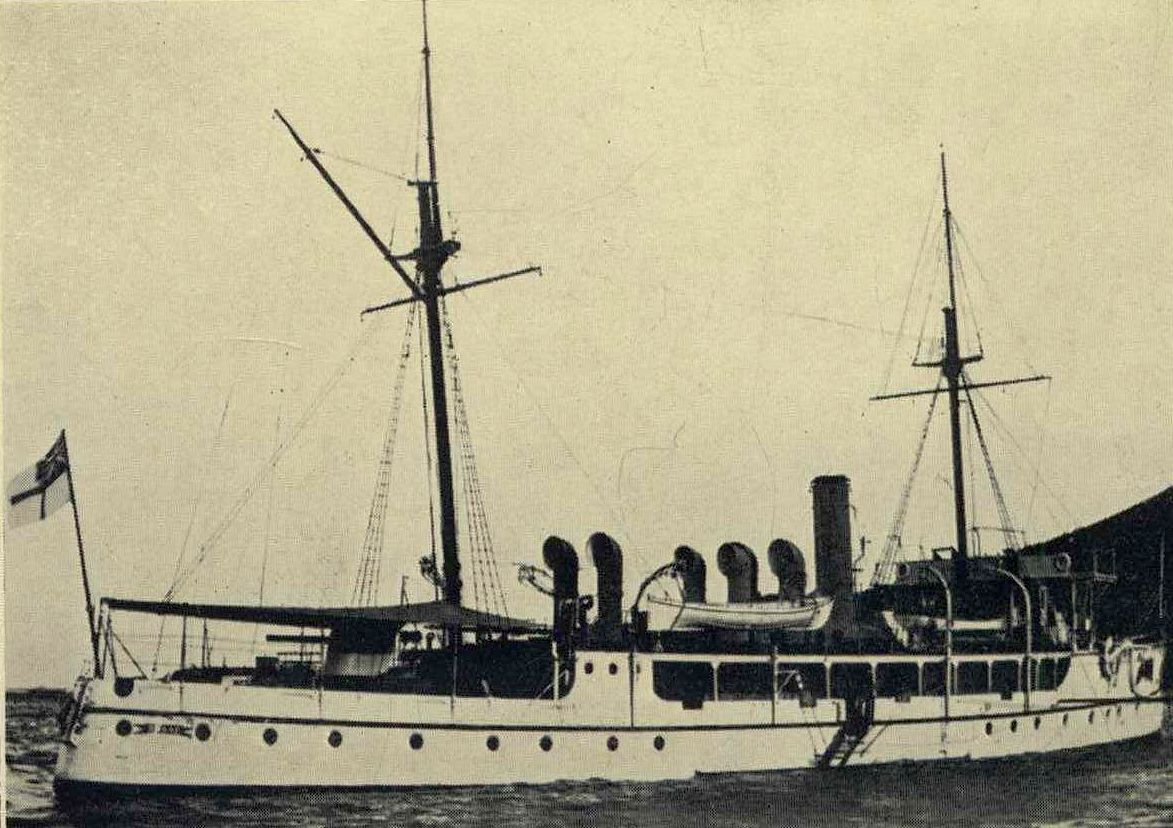

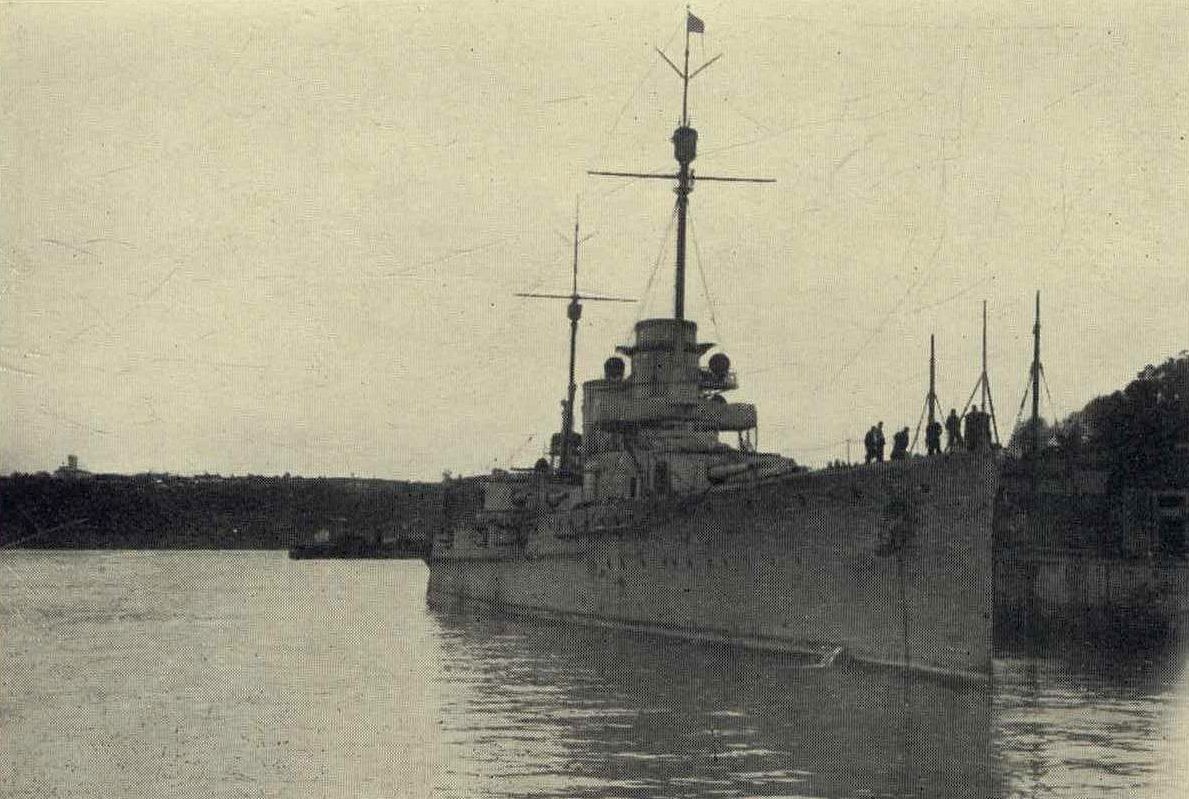

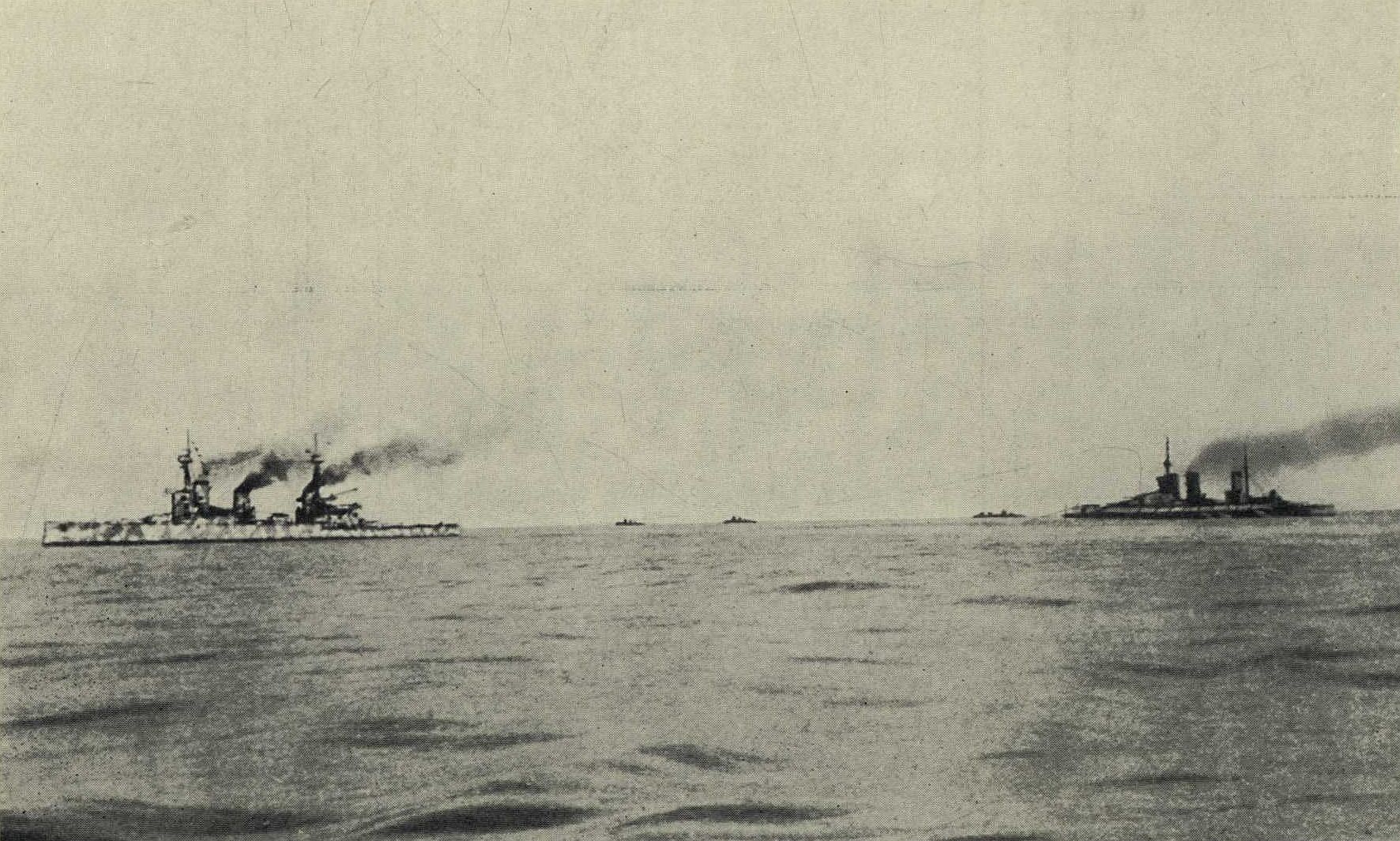

In the accompanying photograph Indomitable is shown as she appeared in November 1914, with her topmasts still up, and the hull painted in a speckled manner for the deception of enemy submarines; for this was still the time when every commanding officer used his own private ingenuity, and fake bow-waves would even be seen. There were many months to follow before standard dazzle designs were invented. When before the end of 1914 this fine battle-cruiser was required for North Sea work and recalled from the Mediterranean, her sisters of the Grand Fleet found difficulty in recognising her. “I had her painted that fashion,” Admiral Kennedy tells me, “before we came home from Malta. I had meant to have the design bolder, but let it go, so to speak.”

And so in December she reached the North Sea.

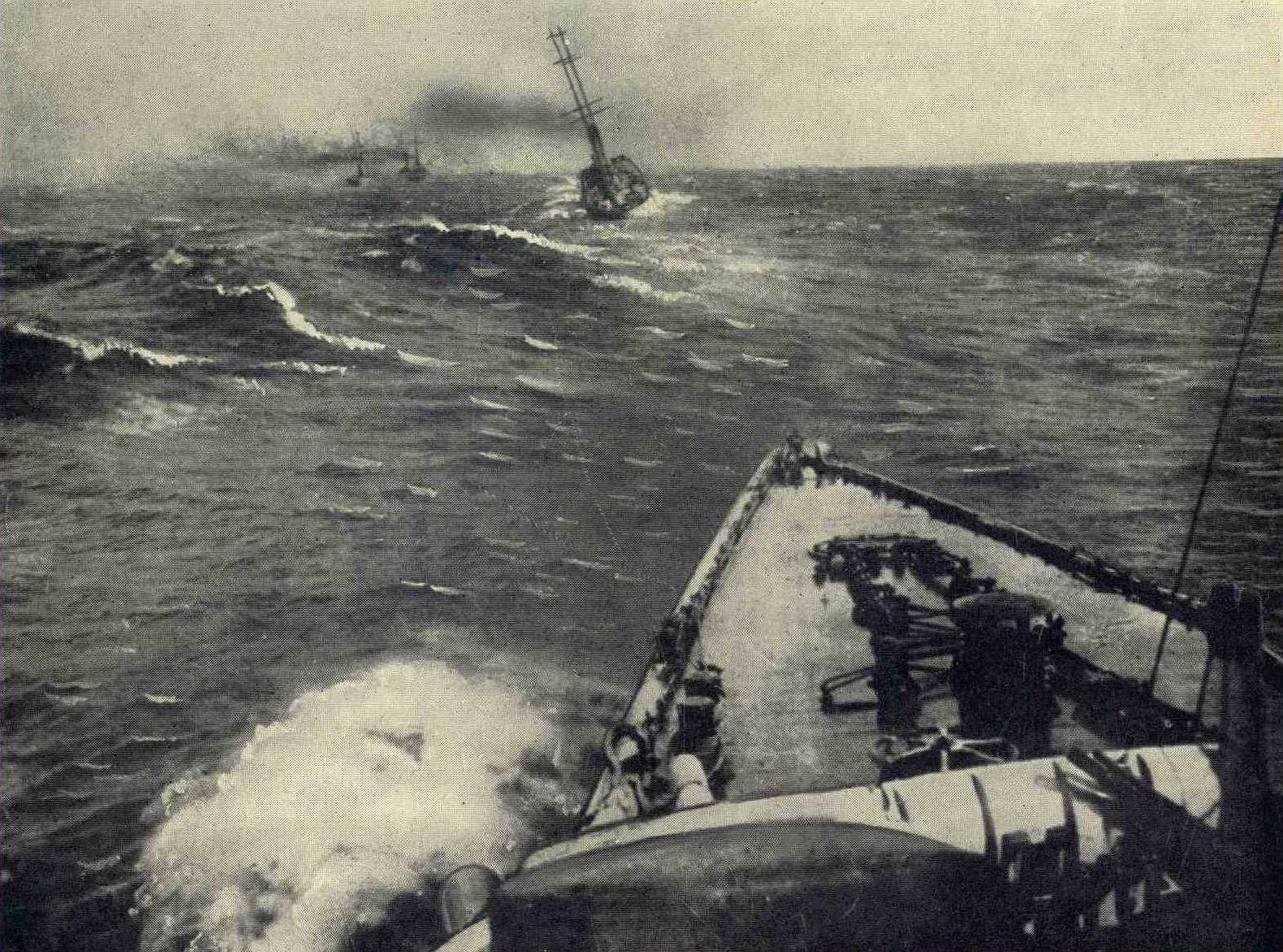

“We were wirelessed about the 23rd to rendezvous somewhere E.N.E. of the Forth—about midway between Scotland and Norway. Drove through a gale up the west coast of Scotland, through Pentland Firth, and down into the North Sea. About 1.30 a.m. on Christmas Day we met a British destroyer flotilla coming north. They were 60 miles out of their reckoning! Sighted the Lion (Admiral Beatty’s flagship of the battle-cruiser squadron) next day. Typical North Sea weather—drifting haze and mist. Made our private signals. Ordered signalmen to tell any other ships seen with her. Lion knew we were to meet her, but the others did not. So (the battle-cruiser) New Zealand, seeing a funny-coloured ship with topmasts still up (I kept them up as long as possible to get the best wireless range, but struck them before going under Forth Bridge) was amazed. ‘There’s an enemy—open fire on her at once!’ ordered the New Zealand’s captain.

“Luckily her Commander overheard the Captain and saw us. ‘For Heaven’s sake, sir, don’t,’ he begged. ‘That’s one of the Invincible class.’ So we were saved by pure luck. We kept to our speckled-hen colour for a good few months till it was suggested that we should all be the same colour. Next time we went to sea, Admiral Beatty had a careful and critical inspection of us in North Sea light, to judge which was the best colour—ours or the usual grey. At times, as the various ships passed in and out of mist and rain, sunlight, and so on, sometimes we were least seen, sometimes more seen than the other ships. Roughly speaking, the difference was so small that we painted Indomitable grey again. But I believe we were the first ship to be camouflaged.”

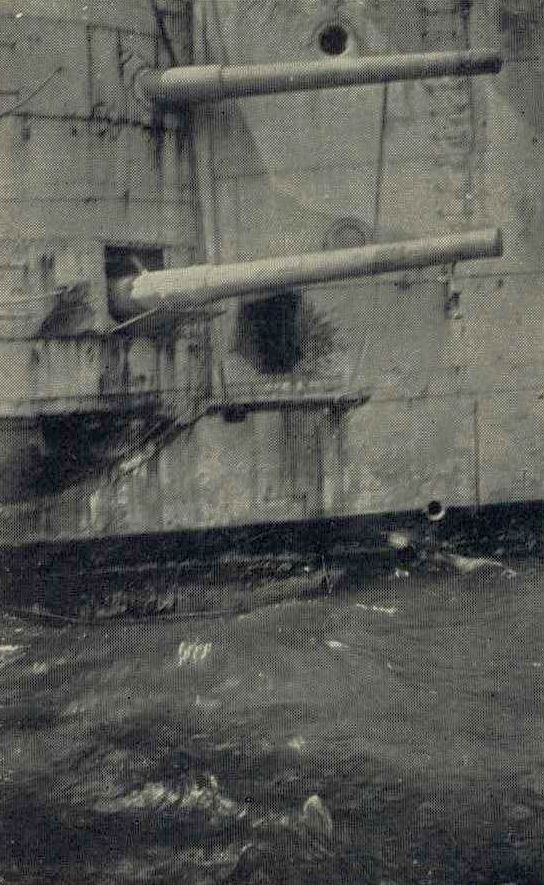

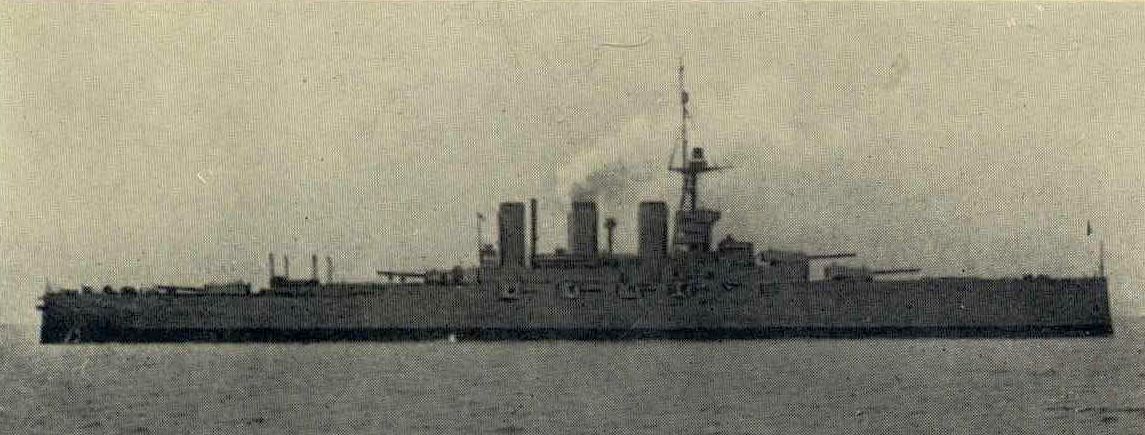

It was not long afterwards that the Indomitable was to play her part in the Battle of the Dogger Bank, and eventually it fell to her lot that she must take the Lion in tow after the latter had been injured by the enemy. The reader will find a unique photograph of this towage in the next illustration; unique, because such a subject often used to be depicted in the old engravings of the Anglo-French wars, when one sailing ship would tow another home, but hitherto there has never been seen an illustration of a modern flagship being thus brought into port after action. It is just such occurrences as these which a contemporary historian might not consider worth while relating: yet posterity cannot fail to be interested by learning how in the steam age enormous men-of-war had to be handled.

“The Lion at the time,” relates Admiral Kennedy, “was down by the bow and heeling over a bit, too. Steaming towards her base—the Forth—slowly. We got ahead of her, and sent a grass-line to her. As she was just tautening it, she signalled to us: ‘Must stop engines.’ And did so. She promptly swung away to starboard and parted the grass line. We had to take up a new position—not handy to do so in a 565-foot ship! Then got a 6½-steel wire to her. Wanted really to get another one also, but time being a factor, trusted to the one 6½. Meanwhile Admiral Beatty was wirelessing us to hustle (as if we were sitting down to a ‘second cup of tea, please’); and the Admiralty, with their large-visioned Winston, wirelessed us that all the German destroyers, etc., were leaving their ports to attack us. Cheery! Wasn’t it?

“But we were splendidly guarded by Commodore Tyrwhitt with his craft and our Forth ones, too. Then the Admiralty sent us another wireless saying, ‘Cancel former signal.’ When we had secured the 6½-inch hawser, we steamed as slow as possible with one engine only, at first; and, as we got way on Lion, increased very gingerly to 13 knots, or rather revolutions which would have given us that speed, had we not got Lion astern. That gave us a bit over 8 knots. We made May Island, and turned up the Forth during the first watch—pitch-dark—saw the Britannia (one of the Fifth Battle Squadron) ashore on Inchkeith, and passed through the boom defence gates. We went on for the open part under the Forth Bridge. It was very badly lighted. Only had a fixed light on it. I had always wished for a flashing light. However, when we got to where we thought we were about 3½ cables from it, and estimated it should be right ahead, we saw a fixed light well on our port bow.”

Anyone who had experience during the war of this bridge will realise the difficulties of towing a big ship through the darkness and not being able to see the iron girders from which the anti-submarine steel net used to be lowered or raised. Nor was it possible for the Indomitable to calculate how much her speed would be diminished by the shoaling of the water acting on the two ships. The tide under the bridge flows strongly, and altogether to-night’s bit of seamanship was a most exacting business at the end of an anxious day when submarines had been expected at all moments. Finally Captain Kennedy decided to anchor short of the bridge for a few hours.

“I anchored and went to bed. Done to a turn! So were some of the others. That must have been about 2.30 or 2.45 a.m. Fog still holding. We had slipped the Lion, of course, in anchoring the two ships. She slipped the wire, too, and it was (I believe) never found—too deep into the mud. Pity of it! Good stuff.” About midday, fog having cleared, the Indomitable again took the Lion in tow, took her up the Forth and turned her round, bringing her right up to her buoy. When one considers that the tide was now flooding, that the Lion had no steam at all—not even for the steering but had to use a hand-wheel—that she was down by the bows and extremely awkward; when we recollect, further, the narrowness of the space above the Forth Bridge, and that the Indomitable was now being assisted by only the weakest tugs (‘the size of the Portsmouth-Gosport ferry-boats sort,’ Admiral Kennedy likens them); we can well claim that this was a most able bit of seamanship which will stand comparison with any of those sailing ship achievements so proudly perpetuated by the eighteenth century artists.

“The whole credit of the tow lies with my Navigator (and still good friend) Commander Morgan Tindal,” insists Admiral Kennedy. But such modesty and unselfish acknowledgment are only part of the great story.

The Lion’s officers were under no delusion as to what they owed for this patient persistence, and presented Indomitable with their gratitude symbolised by a silver trophy “Winged Victory,” which now adorns Admiral Kennedy’s dining-room table.

DURING the War the expression “Special Service” was a convenient but comprehensive synonym which might mean nothing, or a great deal; but in naval matters it was a useful hint to signify something of the hush-hush type. Special service ships might be decoys, or they might be detached units for keeping an eye on particular localities where the ocean cables ran the risk of being cut by a U-boat; or, again, those steam yachts were said to be on special service when they cruised off the Iberian peninsula gathering secret intelligence regarding enemy activities.

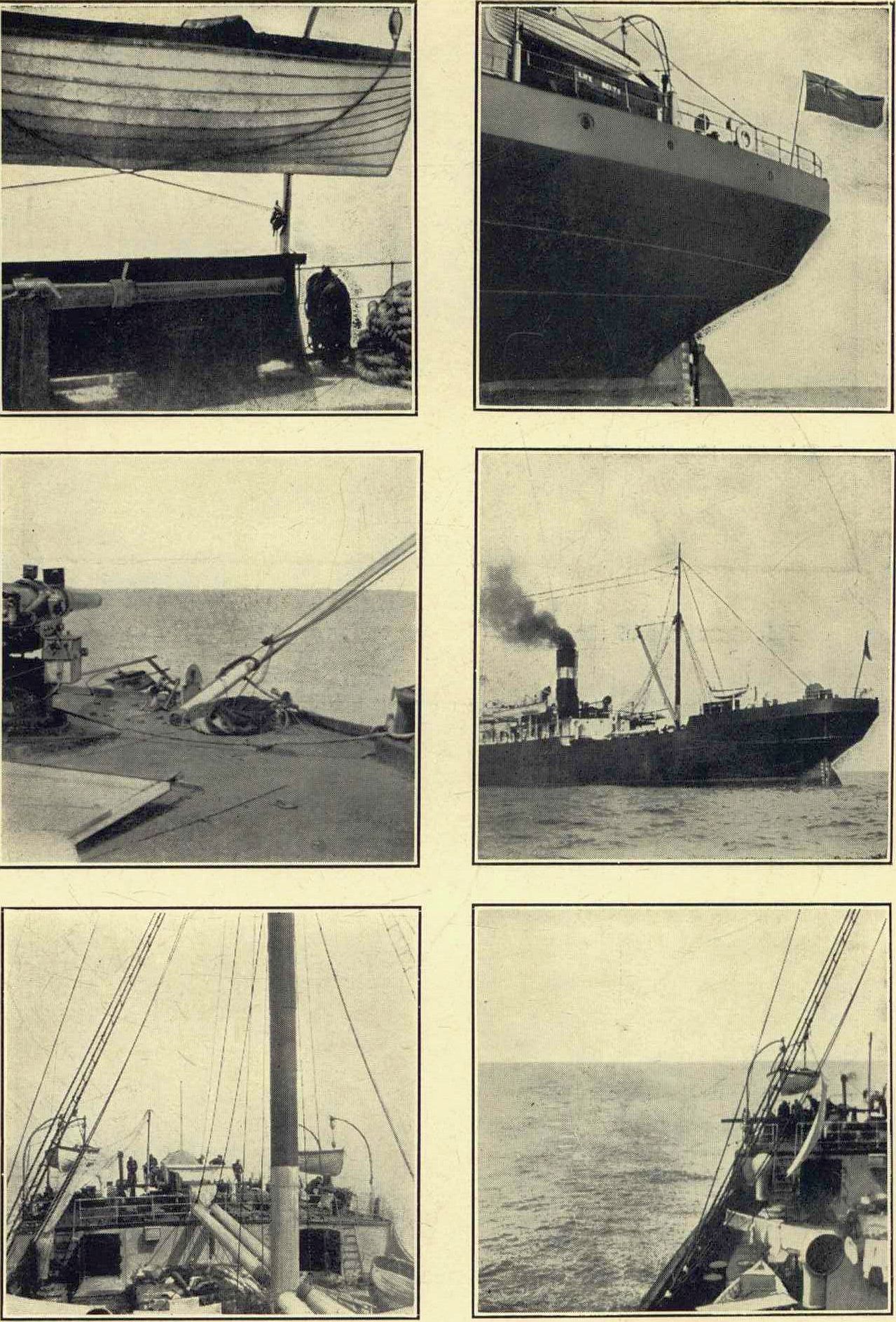

But whilst there were all sorts of units working individually, sent out on particular missions, there was only one Special Service Squadron; and so little has been written on this subject, except by casual mention, that it is well to give for the first time a complete account from many sources of an experiment which was thoroughly original, extremely interesting, and not without humour. Elsewhere the reader is made familiar with the plan that was developed for disguising commissioned ships of war to resemble innocent merchantmen, the intention being for the purpose of enticing enemy submarines, and the said vessels always worked independently.

The Special Service Squadron was the exact opposite of what eventually became constituted as Q-ships. The basic idea was to disguise genuine merchant steamers so that in every visible detail they appeared to be battleships or battle-cruisers; and to employ them not singly but together. Nor was the prime object to deceive U-boats (though this was not excluded), but generally to mystify by their presence and confuse the German intelligence system. What, it may be inquired, was the direct reason for putting this broad notion into execution at a given date?

For answer we have to throw our minds back into those dark days of late October 1914, when Admiral Jellicoe had taken his Grand Fleet right away the other side of Scotland and down to Lough Swilly in north Ireland until there was a base more inviolate from submarine attack than Scapa Flow at present afforded. It will be remembered that on October 27 one of these battleships (H.M.S. Audacious) after emerging from Lough Swilly had struck a German mine and foundered, but that before the final act of this disaster there had arrived on the scene the big White Star liner Olympic whose Master (Captain H. J. Haddock) did his best to tow the battleship as long as she seemed inclined to remain afloat. The Olympic then steamed into Lough Swilly, where she was kept several days, no communication being allowed with the shore, and every effort was made to preserve secrecy. Admiral Jellicoe telegraphed the Admiralty suggesting that the loss of the Audacious should not be revealed. The whole military outlook at that period was, in fact, so grave that it was considered vital that neither the strength nor the geographical position of the Grand Fleet should become known in Germany.

Now when it is alleged of a person that he was seen on a particular occasion in a certain locality, he has a perfect reply if he can plead an alibi. In the sphere of fictional literature we know the countless possibilities when a man has a double. And on the very day after the Audacious went to the bottom, the Admiralty took the novel determination to bring into being a squadron (afterwards increased to a fleet) which could show itself at sea to all beholders, and would pass for all practical purposes as part of the Grand Fleet. German spies ashore, or travelling in liners, or scouting U-boats, would be very welcome to report that they had noticed battleships and battle-cruisers in a certain locality steaming on an observed course. In other words the aim was to provide an alibi for the Grand Fleet, and to give them the chance of mistaken identity.

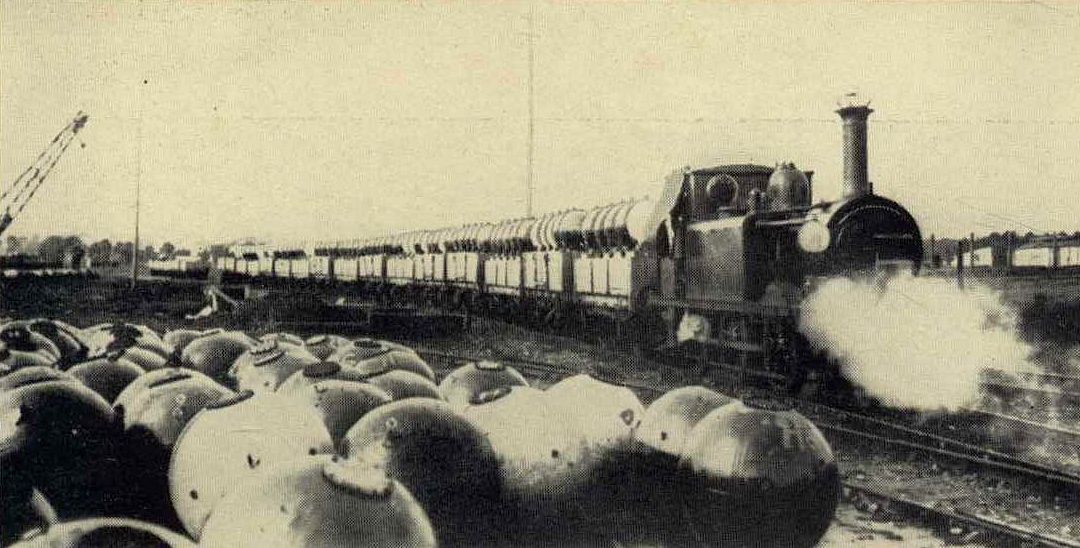

Thus was born the plan to produce in the minimum time a force that was first designated the “Tenth Battle Squadron,” afterwards changed to the “Special Service Squadron” (lest there should be any possibility of the term being confounded with the “Tenth Cruiser Squadron” that were engaged in carrying out the Northern Patrol); but unofficially the ships were hereafter always referred to as the “Dummy Dreadnoughts,” and the title was so fitting, so easy to the tongue, that it was generally accepted. Before the month of October was out, arrangements had been made to take over a number of good sized steamships from well-known lines and to have them fitted out by Messrs. Harland & Wolff at Belfast. All this necessitated a vast rush of work, consultations with Lord Pirrie, the Belfast Harbour Commissioners, Admiralty draughtsmen, and so forth. Special arrangements had to be made for preventing leakage of this secret endeavour, but of course the news did reach Germany within a few weeks.

The problem of converting so bold an idea into fact required enormous effort, but the essential scheme was started when the draughtsmen prepared the tracing of a selected steamer on the same scale as the tracing of a battleship’s design. By placing one over the other, it was possible to determine how the transformation would work out. The next stage was to let 2000 of Harland & Wolff’s men get busy on so many of the steamers as had arrived in the Lough. Ten ships were obtained readily, and so promptly were the conversions begun that within a week the first seven liners were rapidly changing their external characteristics.

It may be said at once that the faking was conceived with extreme cleverness. Structures of wood and canvas were ingeniously designed to reproduce in detail such striking features as guns, turrets, funnels, boats, tripod masts, bridges. Between the modern battleship and liner there is such fundamental difference in architecture, that the vast undertaking was far more awkward than one at first realises. For instance, a liner possesses much greater free board than a man-of-war, but this was overcome by giving the merchantmen ballast to bring them down into the water. Then there was the problem of the stern. In the Merchant Service this end is usually a counter: in the Navy it is like what is known as a canoe-stern, or more accurately what is called a cruiser-stern. So the designers got over the difficulty by filling in the under part below the counter. Similarly, the steamers’ bows had to be modified to bring them into line with naval practice.

Another item was how to make both funnels have reality. Smoke could exhaust itself through one, but what about the other? It would never do if this always seemed inactive. So a small fireplace was fitted to burn fireballs, and clouds of smoke could be emitted freely. As to the anchors, apart from the liner’s own customary gear for practical use, wooden anchors were secured to the bows Navy fashion, or else painted on. Internally there was no similarity to the pretended original battleship. Inasmuch as mines were causing such losses, it was decided that neither officer nor man was to berth forward, but only stores were placed in that part of the ship, so that if her forefoot caused mines to explode, the loss of life ought not to be great. The men were accommodated aft, whilst officers were amidships.

In the carrying out of this imitation theory, time was of principal importance. Ordinarily the work should have taken months: actually only the fewest weeks were permitted. It could not therefore be expected that the disguise was without blemish, and the most which might be expected was to produce an effect that possessed accuracy only at a distance of several miles. No fraternity is more critical than seafarers; every ship sighted on the ocean is mentally analysed and placed in her proper category. But it was hoped that with the kind of climate habitual to the British Isles these ships when descried in silhouette would pass for the real thing.

With one exception, the ten chosen steamers were of ancient or middle age. Thus the Ellerman liner City of Oxford was built as far back as 1882, the White Diamond S.S. Michigan dated from 1887, the Royal Mail Steam Packet Oruba from 1889. The Perthshire had been launched in 1893, the Montcalm four years later; and four of the Canadian Pacific Railway liners, Mount Royal (built 1898), Montezuma (built 1899), together with the twin ships Ruthenia and Tyrolia (both built in 1900), comprised nine which had to be bought in the usual way. But the tenth was the North German Lloyd Kronprinzessin Cecilie, which was a handsome American liner only nine years old and confiscated as a prize at the beginning of hostilities. The necessary figures of the respective tonnage will be found set forth on another page, but it will suffice for the present to add that the German (8684 gross tons) was the biggest of the ten, and the City of Oxford (4019 gross tons) was the smallest. These measurements, by the way, represent them as peace-time merchantmen: their displacements when fitted out as dummy men-of-war and well ballasted, had no regard to these figures.

The above ten were altered to resemble battleships of the St. Vincent, Orion, Iron Duke and King George V classes. So expeditiously were the City of Oxford and Michigan transformed into St. Vincents that within five weeks from the initial decision they steamed away from Belfast, Ruthenia (alias King George V) and Montezuma (otherwise Iron Duke) leaving five days before Christmas. But within another five weeks all the rest had departed with the exception of the Kronprinzessin Cecilie. It was a smart bit of co-operation to have brought about a dummy squadron inside three months. At the end of November (1914) it was further decided to take up four more steamers which were to represent the battle-cruisers Queen Mary, Tiger, Indomitable, and the Invincible. For this end there were adopted respectively the White Star Cevic, Merion, the Manipur (Messrs. T. & J. Brocklebank), and the Patrician (Messrs T. & J. Harrison), and once more only three months were required.

Three administrative minds at the Admiralty concerned themselves in launching this ingenious proposition: Lord Fisher, Admiral Sir Percy Scott, and Mr. Winston Churchill. But all three had individually the same officer in mind to go afloat in charge of this remarkable squadron. It was to be that same Captain Haddock who had been in command of the Olympic. No better choice in all the Merchant Service could be found. Not merely was he eminently suited by his long Atlantic service in the biggest liners, but he had for years been known to, and admired by, both Lord Fisher and Sir Percy Scott. The notable effort of towing Audacious a few days previously by the 43,000-ton Olympic was an achievement in daring seamanship which Admiral Jellicoe has described as “most magnificent.” There could be no doubt that Captain Haddock must be appointed the squadron’s Commodore, a rank which instantly was reminiscent of that fine engagement when little more than a century previously Commodore Nathaniel Dance on his way back from China in command of East Indian merchantmen had met and defeated a squadron of French warships commanded by a Rear-Admiral.

“When I came back to the Admiralty as First Sea Lord on October 31, 1914,” wrote Lord Fisher,[10] “I at once got hold of Haddock, made him into a Commodore, and he commanded the first fleet of dummy wooden ‘Dreadnoughts’ and battle-cruisers the world had ever looked on, and they agitated the Atlantic.” The bluff old First Sea Lord had first met the great Master Mariner in 1910 when the latter was commanding the famous Atlantic flyer Oceanic, and did not hesitate to regard Captain Haddock as the “Nelson of the Merchant Service.” “If this should meet the eye of Haddock,” added Lord Fisher, “I want to tell him that had I remained [at the Admiralty], he would have been Sir Herbert Haddock, K.C.B., or I’d have died in the attempt.” Greater expressions of praise could not have been forcibly framed by one whose frequent phrase was “sack the lot!”

But Sir Percy Scott also claimed[11] to have been responsible for this choice. In his reminiscences he related that on being sent for by the First Lord (Mr. Churchill) on November 3, 1914, and being ordered to take supervision of converting and fitting out the dummy fleet, he found “the question of equipping this squadron with officers and men was a difficult one, but I had the good fortune to meet Captain Haddock, C.B., who had given up command of the Olympic. He had been with me in H.M.S. Edinburgh in 1886. I took Captain Haddock to the Admiralty, and suggested that they should make him into a Commodore, and place him in command of the squadron, with full power to ship the necessary officers and men.” It was Scott who suggested the title “S. C. Squadron,” which could be used to mean either the “Special Coastal Squadron,” or even the “Scare Crow Squadron!” According to this authority the cost to the nation of this experiment—that is to say the purchasing and alteration of thirteen ships, with the alteration of the fourteenth—amounted to £1,000,000.

Captain Haddock, then, was readily given command of these comic ships on November 6, 1914, and the rank of Commodore (First Class), R.N.R. The plan was to have in each vessel a Commander, R.N.R., and two Lieutenants, R.N.R. The remuneration was based on the usual Mercantile Marine pay plus 15 per cent. Even from the first so experienced an officer was invaluable in arranging preliminary details connected with personnel, and inspection of the ships.

It was on December 7 that Scapa Flow was interested, if amused, by the arrival of two St. Vincent class battleships from Belfast. These were Nos. 1 and 2, being hitherto the City of Oxford and the Michigan. Others followed, and the remoteness of Scapa Flow seemed specially suitable, as it would keep the squadron away from spies and public notice. But the ships’ original names were removed and (apart from the individual numbering) they were reported in all seriousness as King George V, Centurion, Dreadnought, and so on. Within a week of Christmas, however, the plain blunt fact emerged that here was another of those instances where theory and practice can never agree.

In the realm of literary ingenuity the employment of a “double” has on various occasions been the basis for a rattling good story. It is common experience that nearly everyone of us has his counterpart, and that nature seems to use the same pattern for very different personalities. Thus the reader of mystery novels is quite willing to accept the convincing situations into which the hero is led. Now the novelist, to be frank, would have to admit that he won over the reader simply because the latter was too lazy, or too lacking in imaginative penetration to bother excessively. It is only when the double-identity theme comes to be vitalised by the stage or cinema that the whole idea collapses because it is inherently weak. Less than twenty years ago the whole literary world was thrilled by a novel of this class, and when it appeared first as a serial story in a popular magazine, the suspense and uncertainty were so worked up that at least one man on his death-bed, fearful that he would pass out before knowing the sequel, sent a letter to the author begging to be informed as to the final chapter. Now in course of time this immensely successful story was produced by the late Sir George Alexander at the St. James’s Theatre, where it became an immediate failure simply because the double-identity idea, whilst powerful in the imagination, will not work out in such details as voice, mannerism, and other decisive items. But, until the two characters were seen in the flesh by the reader-spectator, this consideration had not been appreciated.

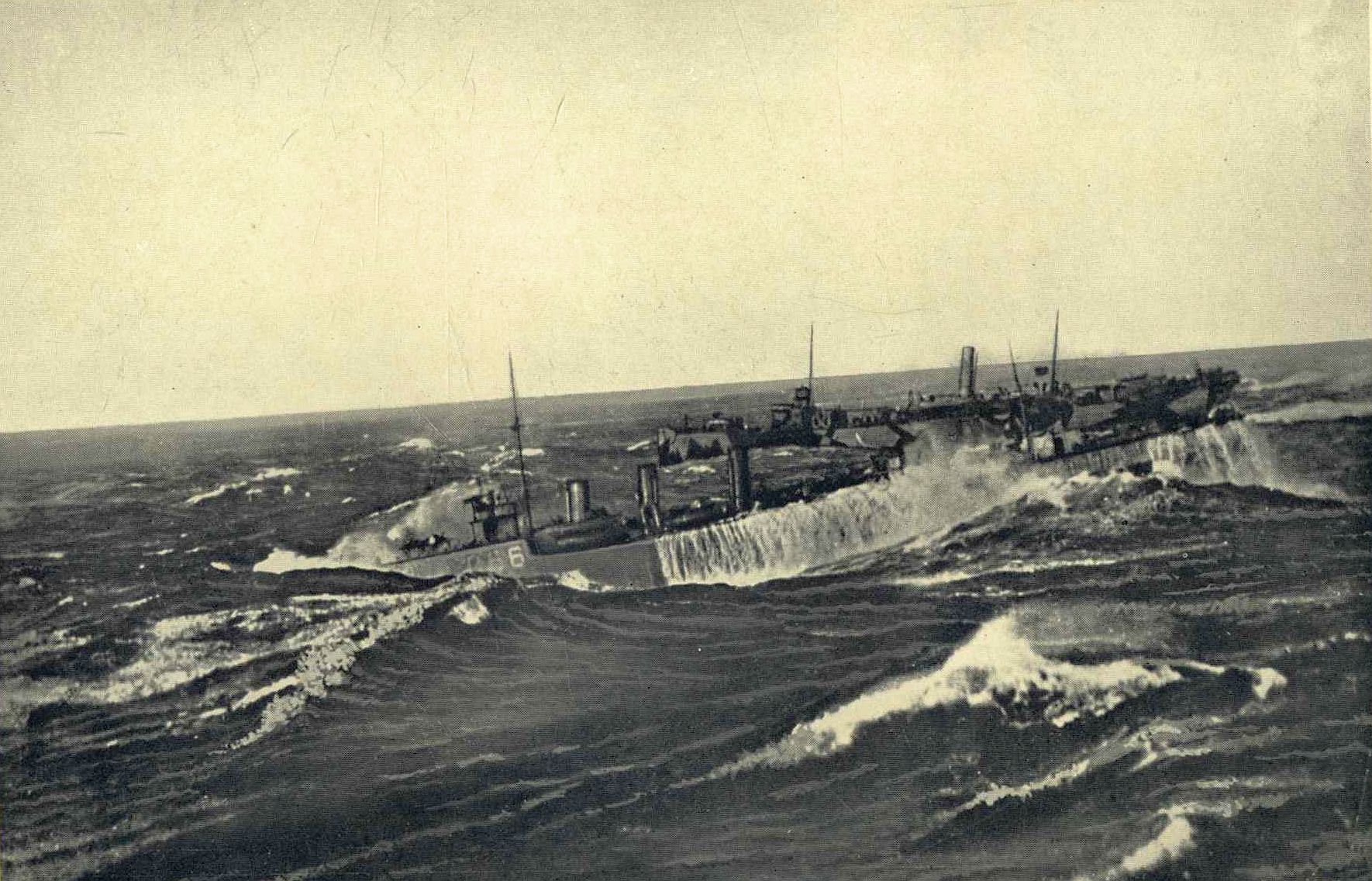

Precisely the same thing happened with these dummy battleships. The essential idea was perfect, but the impossibility of winning conviction could not be ascertained until the experiment was fully tried out. In order to succeed beyond question, every minute part of the composite whole must be 100 per cent infallible. And this is just where the Special Service Squadron flopped badly: it was neither one thing nor the other, but a proper misfit. The tactical utility of a battle squadron rests on its homogeneity, so that it can be employed as one mighty machine. In this imitation from Belfast the only homogeneity consisted of an attempt to deceive. By the time ballast and alterations had been put aboard there were only two ships which were identical in size: some were more than double the displacement of the others. In fact the tonnage now varied from 7430 to as much as 16,500. So, too, whilst the individual speeds were as high as 15 knots but as low as 10, it obviously meant that the squadron’s speed must be less than that of the slowest member. In practice it was found that 7 knots was the best rate at which this collection of dummies could steam when proceeding together to represent part of the Grand Fleet.

Apart altogether, therefore, from imperfect disguise, the faked battleships were condemned as soon as they were tested. A 7-knot squadron could certainly not be used in operations with the Grand Fleet of three times that speed. “The ships,” remarked Admiral Jellicoe, “could not under these conditions accompany the Fleet to sea, and it was very difficult to find a use for them in home waters.”[12] So, quite early, the thought of using these improvised vessels as bait for the shy High Sea Fleet was found impracticable, though had it been attempted there might have ensued a remarkable ending to a grim joke. I wish to stress here the fact that every officer and man serving in that dummy fleet was potentially a hero: they were by willingness, if not in act, ready victims for the Allies’ cause. They knew that if once they were sighted by the enemy, it was all over, yet it might have the most desired opportunity for the Grand Fleet to step in and deal a smashing defeat. For this end these gallant Mercantile Mariners were fully prepared to sell their lives, and to this day they have never been conceded by the public that esteem which was most justly due. It makes no difference that officers and men were not called upon to immolate themselves in some such affair as a Dogger Bank action.

Had they been (as they fully expected) sent down the North Sea, to meet the enemy, they would for a few minutes, during the first misty recognition, have created a thrill: but a 7-knot speed would have enabled neither a protracted advance nor a rapid retreat. And the Germans would not have been puzzled for long by any camouflage. The first salvo would see wooden turrets and toy guns floating in the water or burning like a haystack. And then the joke would be transferred: within a few minutes not one of those converted steamers would be afloat nor one man alive.

So, it was ultimately settled, that instead of the dummy squadron being allowed to remain at Scapa as an unwanted embarrassment and occupying sheltered berths which were needed for better ships, they should be sent to Loch Ewe on the west of Scotland where loneliness and therefore secrecy could still be preserved. Here, during January, as the units one after another were commissioned and sent from Belfast, the collection grew, and Commodore Haddock worked them up to carry out fleet movements. “This,” wrote Admiral Jellicoe, “he did most successfully, so that had the ships possessed the requisite speed, use might have been made of them as a squadron for various decoy purposes. But under the conditions existing, this was impossible.”