* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Narrative of a Voyage to Hudson's Bay in His Majesty's Ship Rosamond

Date of first publication: 1817

Author: Edward Chappell, 1792-1861

Date first posted: Jan. 25, 2017

Date last updated: Jan. 25, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170130

This eBook was produced by: Andrew Sly, Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

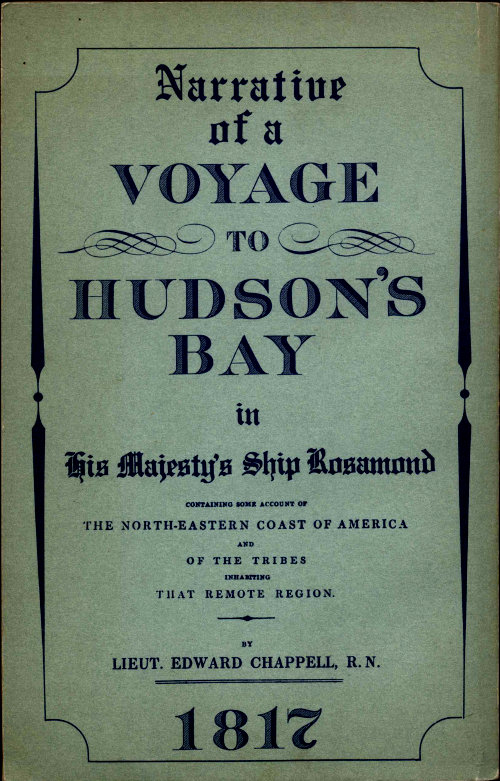

MAP

of the

GREAT NELSON RIVER,

from the

Great Lake Winnepeg to the Gull Lake.

Shewing the different

Portages, Falls, and Rapids;

BY MR. WILLIAM HILLIER

Master in the Royal Navy

N.B. The figures denote the number of feet in each fall of the River.

High-Resolution Map

BY

LIEUT. EDWARD CHAPPELL, R. N.

Ὑμεῖς δ’, ὦ Μοῦσαι, σχολιὰς ἐνέποιτε χελεύθους.

DIONYSII PERIEGESIS. v. 63. Ozon. 1697.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. MAWMAN, LUDGATE STREET:

By H. Watts, Crown Court, Temple Bar.

1817.

COLES CANADIANA COLLECTION

Facsimile edition reprinted

by COLES PUBLISHING COMPANY, Toronto

© Copyright 1970.

Originally printed in 1817

for J. Mawman,

Ludgate Street, London, England

TO THE

LORD VISCOUNT PALMERSTONE

BARON TEMPLE

SECRETARY OF WAR

MEMBER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

&c. &c. &c.

THE FOLLOWING

NARRATIVE

WITH HIS LORDSHIP’S PERMISSION

IS DEDICATED

AS A MEMORIAL OF GRATITUDE

AND A TRIBUTE OF RESPECT

BY HIS LORDSHIP’S

OBLIGED AND FAITHFUL SERVANT

EDWARD CHAPPELL.

Towards the close of the year 1814, a young naval officer, Lieutenant Chappell, of his Majesty’s ship Rosamond, who had recently returned, for the second time, from an expedition to the North-eastern coast of America, brought to Cambridge a collection of the dresses, weapons, &c. of the Indians inhabiting Hudson’s Bay[1]; requesting that I would present these curiosities to the Public Library of the University. This Collection so much resembled another which the Russian Commodore Billings brought to Petersburg from the North-western shores of the same continent, and part of which iv Professor Pallas had given to me in the Crimea, that, being desirous to learn whether the same customs and language might not be observed over the whole of North America, between the parallels 50° and 70° of north latitude, I proposed to Lieutenant Chappell a series of questions concerning the natives of the North-eastern coast; desiring to have an answer to each of them, in writing, founded upon his own personal observations. In consequence of this application, I was entrusted with a perusal of the following Journal. It was written by himself, during his last expedition: and having since prevailed upon him to make it public, it is a duty incumbent upon me to vouch for its authenticity, and to make known some particulars respecting its author, which may perhaps give an additional interest to his Narrative. The Letters, indeed, which have accompanied his communications with regard to his late voyage, v are strongly tinged with the “infandum jubes renovare dolorem;” because, to the ardent spirit of a British seaman, no service can be more depressing than that which, during war, banishes him from the career of glory, to a station where no proof of skill or of intrepidity, no enterprise of fatigue or of danger, is ever attended with honour or reward[2]. Lieutenant Chappell was twice ordered upon this station; after exploits in the navy, which, at a very early period of his life, obtained for him the rank he now holds.

In 1805, he assisted in cutting out the Spanish privateer-schooner, Isabella La Demos, from under the batteries of a small vi bay in South America[3]. In 1806, after witnessing the battle of St. Domingo, he was with the boats which burned the Imperiale of 120 guns, and the Diomede of eighty guns. In the latter end of the same year, his ship, the King’s Fisher, having towed Lord Cochrane’s frigate from under the batteries of L’Isle d’Aix, near Rochfort, assisted in the capture of Le President of forty-four guns. In 1808, he was at the capture of the Danish islands, St. Thomas and St. Croix, in the West Indies. In 1808, or 1809, he was in the Intrepid of sixty-four guns, when she engaged two French frigates, and was very severely handled. Afterwards, he was at the capture of the Saints, and of vii the Island of Martinico, when he was employed on the shore, in fighting the breaching batteries. In 1810, he commanded a gun-boat during the siege of Cadiz. The conduct of the gun-boats upon this occasion requires no comment: it was then that he received a severe wound in the thigh, and was made Lieutenant. In 1812, he assisted in landing the Expedition, under General Maitland, in Murcia. In 1813, he was employed in protecting the fisheries upon the coast of Labrador. In 1814, he made the voyage to Hudson’s Bay, whereof the following pages contain his unaltered Narrative. In 1815, being First Lieutenant of his Majesty’s ship Leven, he was employed in assisting the Chiefs of La Vendee, and in reinstating the Prince Tremouille in the Captain-generalship of the Department de Cotes d’Or.

Such have been the services of this viii meritorious officer, now only twenty-five years of age; but, owing to the termination of the war, dismissed, with many other of his gallant comrades, from the active duties in which they were engaged. These circumstances, as it must be obvious, are by no means querulously introduced: nor is the following Narrative made public with the slightest intention of reproaching the Admiralty with the hard lot to which one of its naval heroes was exposed, in being twice employed in such a service:—it is a lot that must fall somewhere; and the present Publication will shew, that the person upon whom it devolved is able to give a satisfactory account of the manner in which this part of his duty was performed.

EDWARD DANIEL CLARKE.

University Library, Cambridge,

April 7, 1817.

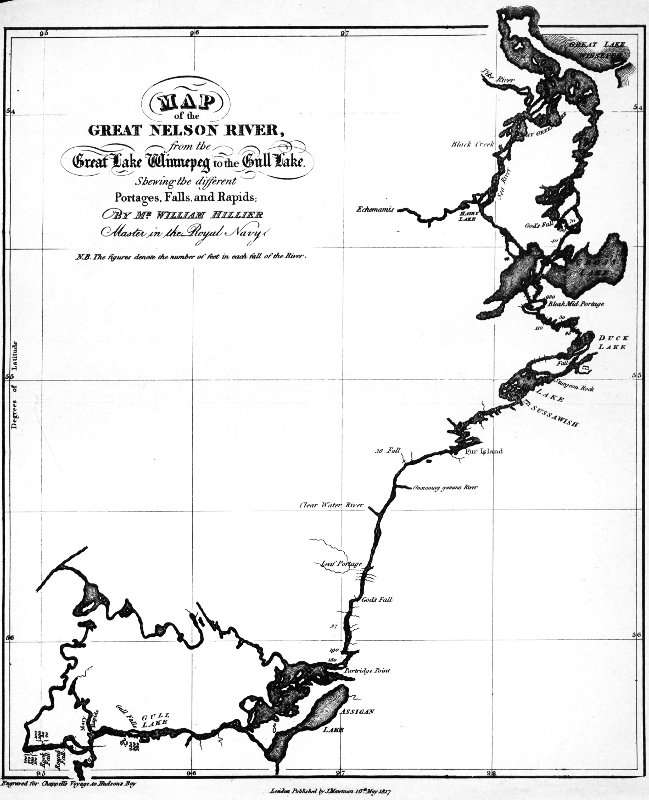

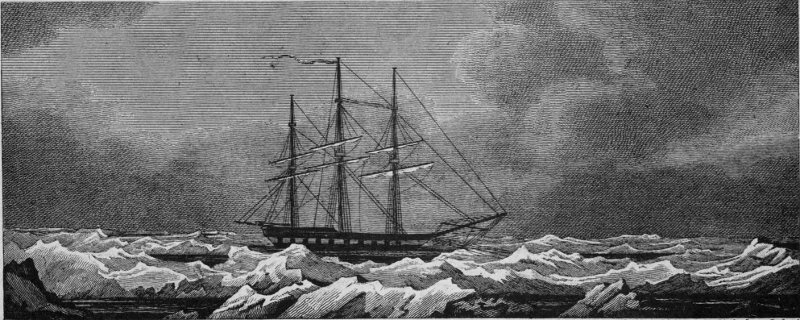

VIEW of the ROSAMOND, passing to windward of an ICEBERG.

On the 14th day of May, 1814, Captain Campbell received orders to repair, without delay, to Hoseley Bay, on the coast of Suffolk; and there to wait for his final directions from the Admiralty.

The Rosamond, at this time, had been lying about a fortnight at Spithead, perfectly ready for sea; and it was conjectured that America would have been the place of her destination: of course, 2 many among us were big with the hopes of fame, and many with the expectation of fortune. When the above-mentioned orders arrived, however, all chance of our proceeding to the seat of war appeared at an end: yet we consoled ourselves with the reflection, that we should doubtless be employed on the coast of Norway; as the whole of that kingdom had been declared in a state of blockade, in consequence of the Norwegians refusing to accede to the Treaty of Keil, by which their country was to be annexed for ever to the dominion of Sweden. Accordingly, we sailed from Spithead.

May 15th.—We had light winds all this day. As we passed out of Spithead, through St. Helen’s, we observed His Majesty’s ship Adamant, and an East-India ship, going in. About nine in the evening: we passed close to the Owers Light.

May 16th.—In the forenoon, fine calm weather, we came to an anchor in sight of Brighton, to wait the change of tide: saw His Majesty’s ship Hope at anchor in the Roads. In the afternoon, got under weigh: observed His Majesty’s brig Tigress standing down Channel. Towards nightfall, we weathered the promontory of Beachy Head, and passed in view of Hastings, where the famous battle was fought between King Harold and William the Conqueror.

May 17th.—At two in the morning, anchored in sight of Dungeness Light-house. At seven A.M. weighed, with a foul wind, and beat towards the South Foreland. Came in sight of the coast of France: observed a large pillar, or monument, on the hills above Boulogne, said to have been erected by Buonaparte. In the afternoon, anchored off the town of Folkestone. 4 Towards evening, weighed again; and, after night-fall, anchored in Dover Roads.

May 18th.—In the morning we had a fine view of Dover Castle, the majestic South Foreland, &c. Got under weigh, and stood across the Channel;—observed many vessels passing between France and England. Saw the spires of Calais. Beat up at the back of the Goodwin Sands;—observed a three-decked ship in the Downs, hoisting the flag of his Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence, under a general salute of cannon from all the shipping. Towards evening, anchored in sight of Margate; but after night-fall, got under weigh again.

May 19th.—In the morning, anchored again, near a shoal called the Galloper. In the forenoon, weighed. Towards evening, passed Orford-Ness Light-houses, and 5 anchored in Hoseley Bay. An officer was immediately sent on shore, to bring on board the final orders. The boat was nearly overturned in landing, in consequence of the heavy surf on all parts of this coast: however, the officer returned about midnight, and delivered the orders to the Captain. Nothing could exceed the consternation and astonishment of every person on board, to find we were directed to proceed, almost immediately, for Hudson’s Bay!—Had we been ordered to the North Pole, there could not have been more long faces among us. Down fell, at once, all the aërial castles which we had been so long building; and nothing remained, but the dismal prospect of a tedious voyage, amidst icy seas, and shores covered with eternal snows.

May 20th.—A boat was this day despatched to Harwich, from which place we 6 were about ten miles distant, to get on board what few naval stores were wanted to complete us for the voyage. Harwich is a small town, with narrow streets, not paved: there are some pleasant walks in the environs. The harbour is a good one, with sufficient depth of water for a frigate. The place is well fortified towards the sea, and has a small naval arsenal. A guard-ship is generally stationed at this port, during war.

May 21st.—In the morning, His Majesty’s ship Unicorn passed us, under an immense press of sail, with a Royal standard flying at her mast-head, which we saluted with twenty-one guns.

May 22d.—Towards the evening of this day, our Captain received orders to proceed to the Nore, in order to procure pilots to conduct the ship safe to the Orkneys. We had 7 also another motive in visiting the Nore at this time, which I may, perhaps, be excused relating, although it have no immediate connexion with the voyage that we were about to undertake. Previous to our sailing from Spithead, a shipwright belonging to the dock-yard had been accidentally killed, by our having fired a signal-gun without taking out the shot. Unfortunately, the poor man’s wife, at the moment of his death, was pregnant of her tenth child. A subscription was instantly opened for her, on board our ship, and £.60 was the next day paid into her hands. I have since been informed, that the different ships at Spithead followed our example, as did also the workmen of the Dock-yard; and a handsome sum was collected in the whole. No blame could be attributed to any person; but, to prevent the possibility of such an imputation, it was thought necessary that the gunner should be tried by a court-martial; 8 and it was to assemble this court, that we were now ordered to proceed to the Nore[4].

May 23d.—In the morning, we weighed, with a strong breeze in our favour; and at noon anchored at the Great Nore;—observed a Russian Vice-admiral, with a squadron belonging to that nation, at anchor there also. We remained at this place, waiting the arrival of the Hudson’s-Bay traders, until the 30th; when the two ships arrived; accompanied by a brig belonging to the Moravian Missionary Society, bound for the coast of Labrador, whither she was to proceed under our protection, or at least as far as our courses lay together. It is a rule with the Hudson’s-Bay Company, to make their ships always break ground 9 on the 29th of May; although, sometimes, they do not leave the river Thames before June. The same day on which the Hudson’s-Bay ships arrived at the Nore, we were joined by a new Captain (Stopford); our former one (Campbell) not wishing, for many reasons, to go the voyage. His loss was most sincerely regretted by all of us: however, our new Commander proved himself, during the whole time we sailed together, to be one of the most exemplary captains in His Majesty’s navy. We continued getting our stores on board until—

June 4th.—Early this day, we weighed anchor. Being the birth-day of our venerable King, all the English and Russian ships of war were dressed with flags, and made a very gay appearance.

June 5th.—We anchored twice this day, to wait the change of tide: at first, off the 10 Gunfleet Sand; and towards evening we brought up, off Harwich.

June 6th.—In the morning, weighed, and beat up into Hoseley Bay;—found lying there His Majesty’s ship Bristol. Towards evening, sent the purser on shore, to procure fresh beef.

June 7th.—The boat returned in the morning, with the purser in sad distress; eight men having deserted from the boat, from an antipathy to the voyage.

June 8th.—A party of soldiers, and an officer, were sent to look for the deserters; but in the evening they returned, unsuccessful.

June 9th.—In the afternoon, weighed with our convoy, and beat towards Yarmouth. In the evening, anchored off Aldborough.

June 10th.—In the morning, we again weighed. At noon, anchored at Yarmouth; and sent a boat on shore, to procure beef and vegetables for the ship’s company; as this was the last place we touched at, in England. Yarmouth is a large straggling place; consisting of one or two good streets, and many narrow lanes; with open spaces here and there, like squares. The church has a most beautiful spire. The town does not contain any magnificent buildings: here is, however, a very fine market-place; and an agreeable promenade, under the shade of two rows of trees, running along the quay on the banks of the river Wensum, on the N. W. side of the town. All the soil around the town is barren; which accounts for the waste of room in the buildings, as land is of little or no value. I know not any place in Great Britain which has finer bathing conveniences. In the evening, we again weighed; and at night-fall 12 passed by Haseborough and Cromer Light-houses.

June 11th.—In the morning, we saw the Spurn Light-house; and towards noon, we passed by Flamborough Head, in Yorkshire. Towards evening, we had a fine view of Scarborough.

June 12th.—A beautiful day, running with a fair wind and smooth sea. In the evening, saw the blue tops of the Cheviot Hills.

June 13th.—A fine fair breeze. Towards noon, passed the Buchan Ness, and had a good view of Peterhead. Towards evening the wind increased to a gale;—hove-to, until morning.

June 14th.—In the morning, passed the Pentland Frith, in which the tide is like a whirlpool; and, after having run by Long-Hope 13 Harbour, we anchored at Stromness, in the Island of Pomona, the principal of the Orkneys; immediately opposite to which is the Isle of Hoy, having on it a remarkable high mountain, in shape very like the Rock of Gibraltar. Immediately on our arrival, the two Hudson’s-Bay ships fired seven guns each, to give notice to the inhabitants of their arrival. The visits of the North-west men, as the Hudson’s-Bay ships are denominated, creates a sort of annual mart, or fair, in the Orkneys; as it is from hence that they derive all the necessary supplies of poultry, beef, vegetables, and even men, to fit them for so long a voyage:—consequently, the Orkney people listen with anxiety for this salute of cannon, which announces the arrival of the N. W. ships; as almost every person in the island is, in some way or other, interested in their coming.

June 15th.—We were employed in watering the ship; and found it difficult to procure a sufficient quantity, owing to a great drought which had lately prevailed.

The town of Stromness is an irregular assemblage of dirty huts, with here and there a decent house. There is scarcely any thing deserving the name of a street in the place, although it is said to contain a population of two thousand souls. A few years ago it did not contain above one third of that number. The harbour is small, but very secure: it is defended from the sea by an island called The Holmes; and there is a good summer roadstead outside the island, called the Back of the Holmes. Firewood cannot be procured in the Orkneys, where there are no trees; but Newcastle coal is always remarkably cheap. About six miles from Stromness is a large lake, 15 called Stonehouse Loch, in consequence of some high flat stones which stand by the side of it, something similar in appearance to Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain: they bear no inscription, and seem to have been set on their ends in the same state as when taken from the quarry[5]:—the view given of them in Barrie’s Description of the Orkney Islands is perfectly correct. The quantities of grouse, partridge, plover, snipe, &c. in the Orkneys, is astonishing: neither foxes nor hares are to be found; but rabbits are very numerous. There are some spots of good land in the valleys; but in such a bad state of cultivation, from idleness and want of manure, that at least five weeds are produced to one blade of corn. Wheat is not grown in any of the 16 islands; the produce consisting, principally, in barley and oats. But the chief export of the Orkneys is kelp, ashes obtained by the burning of sea-weed[6], with which all the shores abound: this proves a most valuable acquisition to those gentlemen whose estates border on the sea; as it sells, on an average, at £.11 a ton; and is collected, at low water, without much difficulty. The kelp estates produce triennial harvests; and when this commodity is gathered, it is sent either to Newcastle, to Dumbarton, or to Leith; great quantities being required for the use of the glass-houses established in those towns. The number of tame geese reared in these islands is really surprising: they wander about the barren hills in flocks, like sheep; and the owners give 17 themselves little or no trouble about them, until they are wanted for sale, or for their own consumption.

June 16th.—I accompanied some of the officers on a shooting party. This circumstance is merely mentioned to introduce a description of the farm-houses; as we visited many of them during our excursion. The delineation of one will answer for all: and surely there never was a scene better fitted for the pencil of a Morland! In one corner stood a calf; in another, a sheep and its lambkin; in the next, walled in with loose stones, a piece of sail-cloth served as a bed for the family; and the fourth corner, as also the sides and roof of the building, were garnished with decayed farming implements. The centre of the habitation was occupied by a turf fire, before which some oaten cakes were roasting; and, in the middle of the roof, a large 18 square hole was cut, to allow the smoke to escape. By the side of the fire, in a large and remarkably high rush chair, sat an old woman, with a spinning-wheel before her, endeavouring to still the cries of a very dirty infant that lay in her lap. There was also another apartment to the hut, for the accommodation of the cows, of which they had a considerable number. The two rooms were not even divided by a door from each other, and the bare earth was the only flooring of either.

During this day we were still employed in getting water on board, although it is rather difficult to be procured.

June 17th.—Our carpenters were busily employed in affixing ring-bolts to the rudder; from which strong iron chains were brought in at the quarter ports of the ship, in order to secure the rudder against 19 the shocks of the drift ice; as we were well aware that we should have to force our way through large quantities of it, in passing Hudson’s Straits: and we afterwards found this to have been a most necessary precaution. We likewise borrowed from the Hudson’s-Bay ships the necessary store of ice-anchors, ice-axes, and ice-poles; neither of those articles having been supplied by the Admiralty, probably from not knowing that they would be requisite.

June 18th.—During the whole of the time that we remained at Orkney after this day, we were busily employed in getting all kinds of necessaries on board.

June 29th.—We sailed from Orkney, at 8 A.M. with the two Hudson’s-Bay ships, and the Moravian Missionary brig, in company. Towards evening it blew a fresh breeze, 20 and the wind veered round against us. At sunset we had a distant view of the Caithness Hills and the Isle of Shetland.

June 30th.—There being a very heavy sea, with rain at times, during this day, we did not perceive any alteration in the climate. The wind still proving foul, we continued to stand to the northward. In the evening, after some very violent squalls and heavy showers of rain, the wind suddenly veered to the N. W. and reduced us to close-reefed topsails, blowing very hard. During the night we stood to the S. W.

July 1st.—In the early part of the day the gale abated by degrees, and towards evening we had fine sunny weather. Wind still in the N. W. quarter; consequently we have made way to the S. W. since yesterday, about 67 miles. Latitude at noon this day, 59°. 10′. N.

July 2d.—In the morning, we saw the Lewis Islands; and the wind chopping round to S. W. we tacked, and stood off shore to the N. W. At noon, as the wind continued to blow steady in the S. S. W., we steered W. N. W. Many Solan geese flying about: these are nearly the size of a tame goose, but the neck much shorter, and the wings longer, tipped with black; all the rest of their plumage being perfectly white. At night-fall, the weather misty, but not cold.

On taking our last departure from the land this morning, it is necessary to observe, that, in my narrative of the voyage, I shall merely state, on each day, the course and distance run by the ship in the preceding day, without making a dull account of latitude, longitude, bearings and distances, allowances for lee-way, currents, &c. &c.; as all this farrago of nautical calculation, however necessary it may be to 22 mariners, cannot fail to tire out the patience of a general reader; and the object of this publication, is not so much to point out the track of the Rosamond, in her voyage to Hudson’s Bay, as to describe the manners and customs of the different tribes inhabiting the shores of that immense gulf.

July 3d.—Course run, W. by N. 66 miles. Thick, foggy weather. During the morning we frequently lost sight of our convoy, but saw them again on its clearing up. Light winds from the S. W. Ship standing to the north. Observed great quantities of a peculiar kind of sea-weed, in the shape of stars. Numberless sea-birds round the ship, particularly Solan geese.

July 4th.—Course run, W. by S. ½ S. 79 miles. In the middle of the night we had a fair wind, which held during the day, accompanied by a thick fog; ship going generally about 23 five miles an hour. Perhaps it is deserving notice, that, since our departure from Orkney, we never had a night so dark as not to be able to read and write.

July 5th.—Course run, W. by N. ¼ N. 101 miles. During the night, lost our fair wind, and got a westerly breeze, with sunny weather. Towards noon, the wind again veered to the S. W. This day we obtained an observation of the sun, for the first time since our leaving Orkney, and found ourselves in latitude 59°. 8′. N. We saw neither Solan geese nor sea-weed.

July 6th.—Course run, W. by S. ½ S. 90 miles. A fair wind all day, variable from N. E. to S. E., ship steering W. N. W. at about four miles an hour. Noticed the air to be getting much colder, probably occasioned by the 24 wind shifting to the N. E. The sea-birds and weed appeared now to have taken their final leave of us; which certainly agrees with the great Cook’s opinion, that when met with in vast numbers, they are a certain indication of the proximity of land. In the evening, we saw a large finner or two. Ship going about seven miles an hour.

July 7th.—Course run, W. ¾ S. 121 miles. In the middle of the night, we lost our fair wind. Early in the morning, saw a strange vessel to windward, and made all sail after her: continued in pursuit the whole day, with light winds, varying from North to East. Every person on board was highly elated with the thoughts of a prize. All notion of the strange vessel’s being a friend was scouted; and it was carried nem. con. that she could be no other than a rich American from Archangel, homeward bound.

July 8th.—Course, W. by N. ¼ N. 79 miles. At one A.M. spoke the vessel that we were in pursuit of. She was a light brig from Copenhagen, bound to Davis’ Straits, where the Danes have some settlements. Early in the morning we rejoined our convoy, and shortly afterwards perceived another brig to windward: we immediately made all sail in pursuit of her, but soon relinquished the chase, as we were apprehensive it might lead us too far from our convoy. Wind about N. by W. Ship standing to the westward. No birds to be seen, excepting one or two solitary sea-gulls, which are to be met with at any distance from the land.

July 9th.—Course run, S. W. ¾ W. 107 miles. A gloomy day. Wind blowing fresh from the North. Towards evening, the wind abated; and it fell calm, which continued through the night.

July 10th.—Course run, S. W. by W. ¾ W. 36 miles. At 2 A.M. the ship was so surrounded by myriads of porpoises, that it appeared as if they had some intention of taking us by storm. It is an opinion of the sailors, that those fish generally precede a smart gale, and make towards the point whence the wind will arise. These swarms were proceeding in a North-east direction. During the fore-part of the day we had light variable winds from the southward; and at noon were taken aback, with a stiff gale from the N. N. W.: it continued to blow hard in squalls.

July 11th.—Course run, S. W. 32 miles. During this day, the wind blew a pleasant breeze from the N. W. At 10 A.M. we put about ship, and stood to the North. It is worthy of remark, that the sky had been so continually overcast, since we quitted 27 the Orkneys, that we had been only able to procure the meridian altitude of the sun twice. Thus we had been twelve days already on our voyage, with only two good observations. It ought also to be mentioned, that we found ourselves much retarded by the bad sailing of the North-west ships; but the Moravian brig sailed very well.

July 12th.—Course run, N. W. by W. 62 miles. It blew strong all night; but we had a fine day; and towards noon, the wind shifted round, and blew fair at South. We got a peep at the sun this day, and found we were in latitude 57°. 15′. N.

July 13th.—Course run, W. ½ N. 76 miles. In the morning, the wind changed to N. by E. and blew a moderate breeze. After night-fall we had a faint appearance of the Aurora Borealis, in the shape of a 28 rainbow, which rendered it peculiarly interesting.

July 14th.—Course run, S. W. by S. 71 miles. At 9 A.M. we tacked about; and the wind coming fair, we steered N. W. by N. Our ship this forenoon was completely surrounded by innumerable flights of sea-gulls. I should imagine that they had been attracted hither by some unusual assemblage of fish, as they were all busily employed in attacks on the finny tribe.

July 15th.—Course run, W. by N. 106 miles. This morning we were going five miles an hour, with a fair breeze and thick weather. It is to be observed, that, with a wind from the South-east or East, we have always had a fog; and I have also noticed this to be the case as far to the southward as the Banks of Newfoundland; although I am utterly incapable to account for it satisfactorily.

Since our departure from Stromness, the variation of the compass had been gradually increasing. We this day allowed for a difference of four points westerly, between the magnetic and the true needle; whereas at Orkney there is only a difference of two points and a half, or 28 degrees. Thus it continued increasing until we arrived within about 300 miles of the settlements in Hudson’s Bay; when it decreases much more suddenly; falling away, in that short distance, to half a point, or five degrees, West—this being the ascertained variation at York Factory. I should think that no subject could exhibit to an inquisitive mind a more astonishing matter of inquiry, than the singular phenomenon which I have just noticed. Can any thing be more surprising, than that the variation should increase but eighteen degrees, in a run of upwards of 2000 miles to the westward; and that it should then begin to turn; and, in the short run of 30 300 miles on the same course, that it should suddenly decrease 41 degrees? An officer belonging to one of the Hudson’s-Bay ships attempted to account for this astonishing attraction of the needle, by supposing the contiguity of metallic mountains; but he could state no facts in support of his hypothesis: and, although the interior of the N. W. part of America has doubtless been explored, and is even actually colonized, owing to the enterprising spirit of a Selkirk, yet I cannot learn that any metallic mountains have been discovered, with a sufficient profusion of ore to cause such an aberration in the compass, and at so great a distance[7].

Our latitude this day was 56°. 35′. N.; longitude 38°. W. Towards noon, our fair 31 breeze died away, and we had light winds from the westward: in the evening, we exercised the men with the great guns, in firing at a cask in the water.

July 16th.—Course run, N. W. ¼ N. 35 miles. Light winds and vexatious calms all this day. We now considered ourselves to be distant from the entrance of Hudson’s Straits about 840 miles. I know not what reason could have induced the first discoverers of the northern regions to give such intimidating names to all the most conspicuous capes, promontories, bays, creeks, &c.; unless they were originally bestowed with a view of preventing others from visiting those countries; and at the same time to enhance the public opinion of their own courage:—for instance, we passed, in our voyage to Hudson’s Bay, Capes Resolution, Comfort, Farewell, Discord, and Desolation; also, Icy 32 and Bear Coves, and the Islands of God’s Mercies.

The ship was now continually surrounded by a species of sea-gull, which, on the water, looked very much like wild-ducks. Those birds appear to be spread in great multitudes quite across the mouth of Davis’ Straits, from Cape Farewell in Greenland to the coast of Labrador.

July 17th.—Course run, W. by N. ¼ N. 20 miles. The light variable winds still continued through this day.

Towards evening we were highly entertained with a combat between a whale and two or three of that species of fish called Finners. The fury with which they engage is surprising. The whale, slowly lifting up 33 his enormous tail, lets it suddenly fall on his opponents with a most tremendous crash; thereby throwing up foam to an amazing height. Although the Finners have incomparably the advantage in agility, yet in size and strength they fall but little short of the smaller whales. The Finners derive their name from an immense fin, which they use with great effect in their attacks on the whale. Sometimes they lift up this enormous fin, and let it fall upon their antagonist, in the manner of a thresher’s flail; at other times, they run their whole body perpendicularly out of the water, exhibiting a beautiful view of their snow-white bellies. In this position they have the singular power of turning round; and thus they contrive to fall sideways on the whale, with a shock that may be heard at a considerable distance.

The sea was this day covered with an 34 oily appearance; and some old Greenland fishermen, who were on board the ship, gave a marvellous account of its being occasioned by the sperm of the whale.

July 18th.—Course run W. ¾ N. 65 miles. Early in the morning we had a fine breeze from the N. E. Latitude at noon, by an observation of the sun, 57°. 24′. N.; longitude, by our account, 41°. 17′. W. According to some charts, we considered ourselves this day to be in the longitude of Cape Farewell in Greenland. Nothing can exceed the uncertainty that prevails, in almost every chart and book of navigation, respecting the longitude of the Cape in question. In proof of this, I shall quote an extract from the accompanying Memoir to Mr. Purdy’s Chart of the Atlantic:—“Both the Requisite Tables, and Connaissance de Tems, state the latitude of Cape Farewell at 59°. 38′. N., and longitude, per 35 chronometer, at 42°. 42′. W.; but the Danish charts place the Cape two degrees more to the West. We know not which is right, or if either; and have, doubtingly, placed it in 43°. 40′. W. as a mean between the two. This is a point on which further information is particularly required. The old books and charts place it from 44°. 30′. to 44°. 45′. W.”

Nothing can be a more serious inconvenience to mariners than this uncertainty respecting the latitude and longitude of places; and it is scarcely to be credited, that so little pains have been taken to ascertain the longitude of Greenland’s southernmost extremity.

We experienced sharp cold this day, and ascribed it to the winds having blown over the mountains of Greenland, on their way towards us. As the next three days 36 furnished no remarks worthy an insertion in this narrative, I shall barely notice the course and distance run by the ship on each day; and the reader may thus pass on to the 22d.

July 19th.—Course run S. W. by W. ¾ W. 60 miles.

July 20th.—Course run W. by N. ¼ N. 68 miles.

July 21st.—Course run W. 67 miles.

July 22d.—Course run N. W. ½ N. 47 miles. As an indication of our drawing near to some land, we this morning picked up a broken tree, about eighteen feet long, of the yellow pine species. Although we could not have been less than three hundred miles from the nearest land, it certainly had not been long in the water. After 37 night-fall, we were gratified with a most brilliant display of the Aurora Borealis.

July 23d.—Course run, N. N. W. ¾ W. 23 miles. Early in the morning we saw five Greenland ships, returning to England from the whale-fishery; and shortly afterwards we perceived two ships of war, in the N. W. quarter. At noon we spoke with His Majesty’s ships the Victorious and Horatio. They had been to Davis’ Straits, for the purpose of protecting the whale-fishery; and the former vessel exhibited a melancholy proof of the ill effects likely to result from the extreme state of ignorance in which our best navigators are placed, relative to the exact situation of the Northern lands. The Victorious had struck on a rock, in latitude 66°. 21′. N., longitude 53°. 47′. W.; entirely owing to the coast of Greenland having been laid down four degrees wrong in the 38 Admiralty Charts. The consequences likely to result from the loss of a seventy-four-gun ship, in such a situation, may be easily imagined; allowing every man to have been safely conveyed on board the Horatio. The frigate must herself have been short of provisions at the moment; and in what possible way could the captain have provided for the subsistence of nearly six hundred people in addition to his own ship’s company, in a part of the world where he could not have formed the most distant hope of receiving a supply?—Fortunately, they were not destined to experience the horrors of so dreadful a situation; the Victorious was got off the rock again, without much difficulty: yet that her danger had been imminent cannot be doubted, as she was obliged to get a topsail under her bottom; and at the time when we met with her, there were some apprehensions that she might not reach England in safety; the 39 leak being so bad, that the crew were compelled to labour incessantly at the pumps. The Horatio of course remained with her until she reached a British port.

After all that has been said respecting the erroneous state of even the Admiralty Charts for the Northern Seas, yet I do not imagine that the smallest imputation of neglect can be charged to Government upon that account. It has never yet been thought an object of sufficient national importance, to warrant an expenditure of the public money towards defraying the great expense that must necessarily be incurred in surveying thoroughly those frozen coasts which border upon Davis’ and Hudson’s Straits. The Greenland mariners are notorious for paying so little regard to the situation of the places they visit, that they are incapable of giving any correct information: and the officers of the Hudson’s-Bay 40 ships have a motive in concealing the knowledge which they actually possess: this I shall notice more fully hereafter.

July 24th.—Course run, N. W. ½ W. 34 miles. This morning some slight indication appeared of a lasting fair wind. The fine mild weather that had prevailed for the last fortnight was far from affording satisfaction to the commanders of the Hudson’s-Bay ships; as they prognosticated much more difficulty in getting through Hudson’s Straits, the natural consequence of so much calm weather. It would have pleased them better to have encountered a few gales of wind, even if they had proved foul; as it requires strong winds to carry the drift ice out of the Straits, which is very likely otherwise to choke the passage. Entering Hudson’s Straits, it is a necessary precaution to keep close in with the northern shore; 41 as the currents out of Hudson’s and Davis’ Straits meet on the south side of the entrance, and carry the ice with great velocity to the southward, along the coast of Labrador. We had seen, lately, a number of the kind of birds called, by the sailors, Boatswains: they are so numerous to the southward of the Tropic of Cancer, that they are called Tropic Birds. I cannot say whether they are accustomed to seat themselves upon the water or not; because our visitors flew at a great height over the ship, and we could plainly hear their melancholy screams by night as well as by day. Some amongst them have long feathers, like spikes, projecting from their tails; whilst others in the same flock, and evidently of the same species, are without them: perhaps these remarkable feathers may serve as distinguishing marks between the sexes. At noon this day we were in latitude 58°. 35′. N. longitude 49°. 10′. W. In the afternoon, 42 the Moravian Missionary brig asked, and obtained permission, to part company: she then quitted us, and steered more away to the westward. During the stay of our ship at the Orkneys, I had visited the brig in question, and had there met with an old German Missionary; from whom I learned, that the difficulty of first getting on terms of intimacy with the Esquimaux was almost insurmountable. This Missionary had himself been one of the first who succeeded in so dangerous an object, which could only be accomplished by placing an entire confidence in this wild race of people: he therefore remained alone with them, conforming to their loathsome habits, and mildly endeavouring to gain an ascendancy over their minds. It was a considerable time before he dared to attack those established customs which, to him, appeared most exceptionable. Habit had sanctioned polygamy amongst them; although the nature 43 of their climate, and the difficulty of procuring sustenance, had confined that privilege almost exclusively to their Chiefs. Passion was allowed to be pleaded successfully, in extenuation of murder. It was, therefore, with a trembling, but a resigned heart, that the Missionary first ventured to point out those practices as offences against the Great Spirit. “The Almighty,” said the good Moravian, “assisted my humble efforts, and my endeavours were crowned with success.” I shall also quote his own words as to the result:—“On the bleak and rocky coast of Labrador, a temple is now erected to the worship of God, in which the wild Esquimaux raises his voice in songs of praise to the Most High. Thirty years of my life have been dedicated to this employment; and I am now on my return, to finish my days amongst the flock which has been so manifestly entrusted to my care.”

The Missionary shewed me a Testament, Creed, and Lord’s Prayer, in the Esquimaux tongue: but it will be easily imagined that many deficiencies must have arisen in the first instance; consequently, whenever the Esquimaux were at a loss for words to express any new idea, or the name of any article that they had not before seen, the Missionary supplied them with a corresponding German expression; as the German language, of all others, is most easily pronounced by an Esquimaux.

An English frigate had been on a cruize in Davis’ Straits; and returning thence, along the coast of Labrador, she put into a little bay, for the purpose of procuring a supply of wood and water. The affrighted Esquimaux flew to their beloved Missionary, and pointed out the strange vessel as the cause of their fear: they were, however, soon pacified, and returned quietly to their 45 occupations. Nothing, then, could equal the astonishment of the officers, on landing; when, instead of a wild race of savages, prepared to oppose them, they found a small village, inhabited by an inoffensive people, peaceably employed in their daily duties; and the little children going quietly to school, with books under their arms. Their surprise, however, must have been greatly increased, when they were given to understand, that all this had been accomplished by one man, zealously actuated by a wish of serving his God, in the services he had rendered to these poor Indians[8].

July 25th.—Course run, W. by N. 35 miles. Light variable winds from the southward. We were this morning visited by an officer from one of the Hudson’s-Bay ships; an intelligent man, who had thirty times performed the same voyage. It was his opinion, that the sharp cold, which we had experienced on the 18th of this month, must have been occasioned by the vicinity of ice; and we should doubtless have met with it on that day, had we not fortunately tacked about in time to avoid it. Our latitude at noon, this day, was 58°. 46′. N., and longitude 50°. 16′. W. Towards nightfall, the wind freshened to a fine steady breeze from S. S. W.; and we could plainly discern a bright appearance in the sky, towards the North; this was believed by every person on board to be a certain indication of ice in that direction.

July 26th.—Course run W. by N. 128 miles.—A fine fair breeze all this day; the ship going about seven miles an hour. In the forenoon, we took on board the chief-mate of the Prince of Wales, (one of the Hudson’s-Bay ships,) to act as pilot, or rather to instruct us in the management of our ship, amongst the ice in the Straits. He immediately advised us to raise our anchors, lest the shocks of the heavier masses of ice should break the stocks: we also rove smaller braces to all the yards, that we might be able to manœuvre the ship with the greater facility. At noon, we were in latitude, by account, 50°. 11′. N., and longitude 54°. 20′. W. We now kept our course more to the northward, to prevent the possibility of our falling in with the ice to the southward; as there are always large quantities drifting out of Hudson’s Straits, along the coast of Labrador. Ships do well, therefore, to keep to the northward, until they reach the latitude of Cape 48 Resolution; and when that is attained, they may haul in N. W. and keep close in to the North shore; thus making a semicircle round the ice: but they should be particularly cautious not to keep too much to the North, until they reach the longitude of 54° W. and are consequently quite clear of the coast of Greenland.

July 27th.—Course run N. W. by W. 182 miles. As we were now getting well to the northward, the air began to feel quite frigid; and the wind drawing round to the East, we hauled up North. Latitude, at noon, was 60°. 54′. N. Longitude, 59°. 19′. Our distance from Cape Resolution we computed to be about 171 miles. In the afternoon we saw the first iceberg, which was an immense mountain of solid ice, in the shape of an English barn[9].

Towards evening, we passed another iceberg. It had a complete chain of floating fragments on the lee-side of it, through which we butted our way. We continued to run in for the land, all night, with a fair wind, although it was a very thick fog, and there were numberless icebergs in all directions; indeed, it appeared to me almost miraculous, how we escaped being dashed upon some of them.

July 28th.—The thick fog still continued, until 9 A.M. when it suddenly cleared up, and we saw the island of Cape Resolution, bearing E. N. E. about eighteen miles distant. We had been long wishing to get into the Straits; and now that object was accomplished, we as sincerely wished ourselves back again into the ocean. The prospect on every side was of the most gloomy nature: the black and craggy mountains on shore were only visible towards their bases; 50 their summits being covered with eternal snows, and the aspect of the countless icebergs, on all sides of us, truly terrific. The strong southerly current continually setting out from all the Northern seas has been hypothetically explained, by supposing that Nature thus supplies the deficiency of water occasioned by the evaporation caused by the heat of the sun between the Tropics. It is not my intention to discuss this philosophical question: suffice it to say, that I can bear testimony to the existence of such a current in all the Northern seas, and along the Coast of Labrador and Newfoundland, facing the Atlantic; and the effect caused by the continual flowing of the waters towards the South, is attended with the most beneficial effects; as the Northern seas are consequently cleared of the vast accumulation of ice, which would otherwise infallibly block them up, and render all navigation 51 impracticable. We had taken care to get into the latitude of Lake Resolution, before we bore away to make the land; and although, in running in for the Cape, we still continued to steer a point to the northward of our true course, yet, after all, the southerly current proved so strong, as to set us to the southward of our land-fall: and on our making the Cape, it was eighteen miles to the northward of us.

During the remainder of the day, we were endeavouring, with light winds from the N. E. to get in with the north shore; and towards evening we saw much field ice towards the south. As the setting sun had a different appearance to what it generally exhibits in England, perhaps it may be thought worthy of notice. Although it glittered to the eye, and threw a golden tint on the water, yet it produced no rays, and might be viewed, for any length of time, 52 without paining the sight by its refulgence. So far was it from bestowing warmth, that the air appeared more intensely cold than it had been during the whole of the preceding day. The clouds, in parallel lines immediately above the descending luminary, exhibited, in the most beautiful manner, all the varieties of the rainbow; the dusky red and deep blue being the most predominant colours. If to all this we add the dazzling reflection which glittered from the snow-capp’d summits of the rugged mountains, and the shining fantastic forms of the floating icebergs in the Straits, the prospect will easily be imagined to have excited in our minds those feelings, which induce the mariner, as well as the poet,

“To look, through Nature, up to Nature’s God!”

At midnight we passed an immense iceberg, which roared like a thunder storm; occasioned, perhaps, by some cavity in its 53 side, through which the sea was bursting. It was nearly a calm; and the surface of the sea was quite smooth at the moment, attended with that gentle undulating swell which is always prevalent in deep waters.

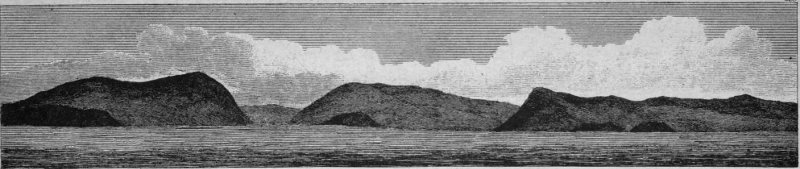

July 29th.—In the morning we were obliged to tack about, in order to avoid a large assemblage of drifting masses, termed by the old seamen a patch of ice: the seals were leaping about in all directions, and some few sea-calves were seen. The thermometer in the Captain’s cabin, with a rousing fire, stood at 43°. At noon we were plying to windward off Savage Island, which is the next land to the west of Cape Resolution Island, on the north shore. Savage Isle, lying very low, has not so much snow upon it, in general, as the other parts of the coast hereabouts. The next land to the westward of it is called Terra Nivea; owing to its having some 54 mountains, about thirty miles from the sea, entirely covered with snow. During the remaining part of this day we continued our course up the Straits, but with the weather almost calm.

July 30th.—We were entirely surrounded this day with a patch of broken ice, and it extended as far as the eye could reach. The sun shining bright over the calm surface of the sea, called forcibly to my mind a description I had once read of the Ruins of Palmyra, in the Syrian Desert; the scattered fragments of ice bearing a strong resemblance to the ruins of temples, statues, columns, &c. spread in confusion over a vast plain.

Cape Saddle Back north 7 or 8 miles: with two remarkable Icebergs off the low Point.

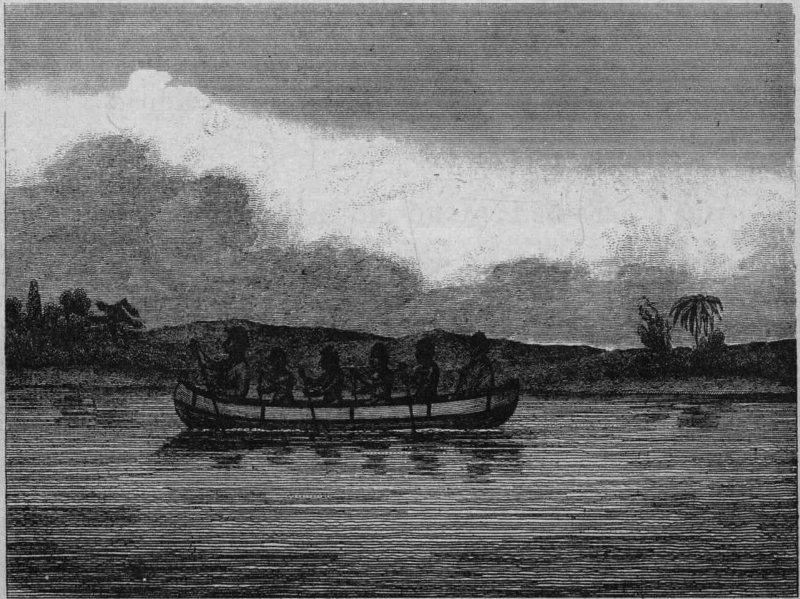

Male Esquimaux in his Canoe.

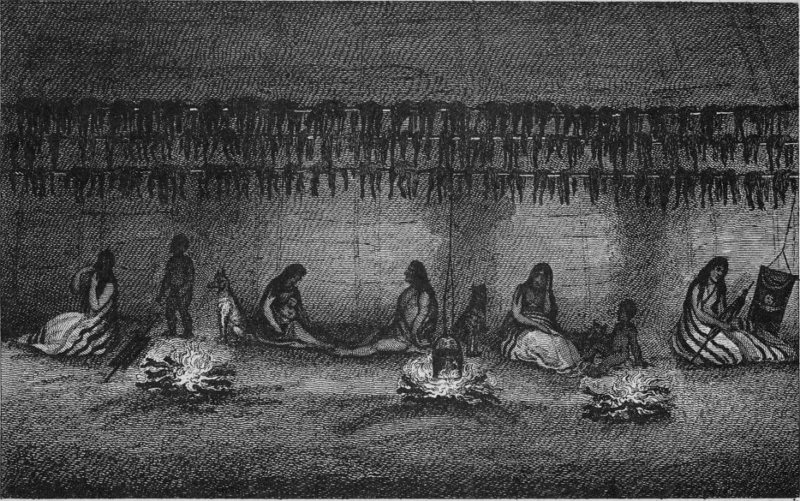

July 31st.—Early in the morning of this day we reached a remarkable cape, called Saddle Back, from the resemblance that it bears to a saddle: and as we were immediately visited by the Esquimaux, I must, for a time, quit the ship and her proceedings, to describe the appearance, manners, and customs of this singular race, who inhabit the shores of Hudson’s and Davis’ Straits, the northern part of Hudson’s Bay, and both sides of the vast peninsula of Labrador. Upon the first intelligence of the approach of the natives, I immediately jumped out of bed, and ran upon deck; where, on my arrival, the most discordant shouts and cries assailed my ears. Alongside the ship were paddling a large assemblage of canoes, of the most curious construction: these were built of a wooden frame-work of the lightest materials, covered with oiled sealskin, with the hair scraped off; the skin being sewed over the frame with the most astonishing exactness, and as tight as parchment upon the head of a drum. But the most surprising peculiarity of the canoes was, their being twenty-two feet long, and only 56 two feet wide. There was but one opening in the centre, sufficiently large to admit the entrance of a man; and out of this hole projected the body of the Esquimaux, visible only from the ribs upwards. The paddle is held in the hand, by the middle; and it has a blade at each end, curiously veneered, at the edges, with slips of a sea-unicorn’s horn. On the top of the canoe were fastened strips of sea-horses’ hide, to confine the lance and harpoon; and behind the Esquimaux were large lumps of whale blubber, for the purposes of barter. These canoes are only capable of containing one person, for any useful purpose; the slightest inclination of the body, on either side, will inevitably overturn them; yet in these frail barks will the Esquimaux smile at the roughest sea; and in smooth water they can, with ease, travel seven miles an hour[10].

Whilst I was still busily employed in making my remarks on the canoes of the male Indians, a large open boat arrived, containing about twenty women, besides many children. This last boat was steered by a very old man, with a paddle: he was the only male adult amongst them. The women pulled with oars, having a very broad wash at the extremity; and they cheerfully kept time to the tune of a song, in which they all joined. The boat was built of the same materials as the canoes; that is to say, a frame-work covered with oiled seal-skins; but differed, in being shaped more after the European boats; also, in having a square sail made of seal-skins, with the hair taken off; and owing to this difference, the Hudson’s-Bay traders have distinguished these boats by the name of Lug Boats; although they never attempt to use the sail, except with a fair wind. It is difficult to give an adequate 58 idea of the delight expressed by these poor creatures, on reaching the ships: they jumped, shouted, danced, and sang, to express their joy. And here it should be observed, that the arrival of the ships is considered by the Esquimaux as a sort of annual fair; their little manufactures of dresses, spears, &c. are reserved for the expected jubilee; and when, after long watching, they at last catch a glimpse of the approaching vessels, their exultation knows no bounds.

The male Esquimaux have rather a prepossessing physiognomy, but with very high cheek-bones, broad foreheads, and small eyes, rather farther apart than those of an European: the corners of their eyelids are drawn together so close, that none of the white is to be seen; their mouths are wide, and their teeth white and regular: the complexion is a dusky yellow, but some of the 59 young women have a little colour bursting through this dark tint: the noses of the men are rather flattened, but those of the women are sometimes even prominent. The males are, generally speaking, between five feet five inches and five feet eight inches high; bony, and broad shouldered; but do not appear to possess much muscular strength. The flesh of all the Esquimaux feels soft and flabby, which may be attributed to the nature of their food. But the most surprising peculiarity of this people is the smallness of their hands and feet; which is not occasioned, as in China, by compression, nor by any other artificial means, as their boots and gloves are made large, and of soft seals’-skin. To their continual employment in canoes on the water, and to the sitting posture they are thus obliged to preserve, perhaps their diminutive feet might be ascribed: but when we reflect on the laborious life they must necessarily 60 lead, and yet find that their hands are equally small with their feet, it will naturally lead us to the conclusion, that the same intense cold which restricts vegetation to the forms of creeping shrubs has also its effect upon the growth of mankind, preventing the extremities from attaining their due proportion.

The chin, cheek-bones, and forehead, among the women, are tattooed; and this operation is performed among the Esquimaux by pricking through the skin with some sharp instrument, and rubbing ashes into the wound: as the marks are not deep, their appearance is not disagreeable. I imagine that the tattooing does not take place until the female arrives at the age of puberty, because the youngest girls were without any such marks. None of the men undergo the operation; but they have a few straggling hairs on the chin and upper lip, while the 61 women carefully remove them from every part of the body, excepting the head, where they have a lock on each temple, neatly braided, and bound with a thong of hide. On the back of the head, the hair is turned up, much after the fashion of the English ladies. I hope the latter will not be offended at the comparison.

After having gone so far in a description of their persons, perhaps their diet ought not to be overlooked; because it has been before noticed, that the relaxed state of their flesh, and the sallow hue of their complexions, may in a great measure be ascribed to the nature of their food. As they seem to devour every thing raw, it has been conjectured that they are unacquainted with the use of fire; but this is not true. I observed, near one of their huts, a circle of loose stones, containing the ashes of a recently extinguished fire, and a stone 62 kettle standing upon it[11]: also, in a hut, I saw a pan of vegetables, resembling spinach, which had been boiled into the consistency of paste[12]. Yet, after all, it is no less certain that an Esquimaux prefers all flesh raw. In proof of this it may be mentioned, that the Commander of the Eddystone, a Hudson’s-Bay ship, having shot a sea-gull, an Indian made signs that he wished for the bird: immediately on receiving it, he sucked away the blood that flowed from its mouth; then, hastily plucking off the feathers, he instantly dispatched the body, entrails, &c. with the most surprising voracity. The knowledge which the Esquimaux possess of the use of fire, is observable in the ingenuity with which they transform iron nails, hoops, &c. into heads for their arrows, 63 spears, and harpoons. May not their fondness for raw flesh have arisen from the scarcity of fuel? There was not a bit of wood to be found on that part of the coast where I landed.

We made many attempts to induce the natives to partake of our food. At breakfast, we placed an Esquimaux at table, and offered him every species of food that the ship could afford. He tasted every thing; but, with a broad laugh, he was sure to eject whatsoever he tasted, over our plates and upon the table-cloth. The only thing they could be induced to swallow was a piece of hog’s lard; and of this they all partook with avidity. Above all, they appeared to have the greatest aversion from sugar and salt.

In their dealings, they manifested a strange mixture of honesty and fraud. At one moment I observed an Esquimaux 64 striving, with all his might, to convey into a sailor’s hands the article for which he had already received his equivalent; and, in ten minutes afterwards, I detected the same man in an endeavour to cut the hinder buttons from my own coat. They value metals more than any other article of barter, and iron most of all. As a specimen of the relative articles of traffic, I shall briefly insert the prices which I paid for some little curiosities[13]; viz.

| A seal’s-skin hooded frock, quite new, for a | knife. |

| A seal’s-skin pair of breeches | needle. |

| Seal’s-skin boots | saw. |

| A pair of wooden spectacles, or rather shades, used by the Esquimaux to defend their eyes against the dazzling reflection of the sun from the ice | one bullet. |

| A pair of white feather gloves | two buttons. |

| A fishing lance or spear | file. |

They have a strange custom of licking with their tongue every thing that comes into their possession, either by barter or otherwise; and they evidently do not consider an article as their property until it has undergone this operation. By way of experiment, I gave to a young girl half a dozen iron nails: she immediately jumped, and shouted, to express her gratitude; and then licking each nail separately, she put them into her boot, that being the depository of all riches among the female Esquimaux, who are entirely unacquainted with the use of pockets. I could easily perceive that each man had a wife; but polygamy did not appear to exist amongst them; perhaps more on account of their poverty, and the difficulty of supporting a plurality of wives, than from any idea they may entertain of the impropriety of the practice itself. Several of the natives brought their wives on board the ship, and, in return for a tin spoon or pot, 66 compelled them, nothing loath, to receive our salutations. Nay, one man plainly intimated, that if I wished to hold any private conversation with his lady, he should have no objection to her visiting my cabin, provided I rewarded him with an axe. Many of the women had very pleasing features; but they were so disfigured with dirt, and their persons smelt so strongly of the seal oil, that it required a stout heart to salute even the prettiest of them.

On board the ship, they were exceedingly curious in viewing every thing: but however astonished or delighted they might appear in the first sight of any novelty, yet ten minutes was the utmost limit of their admiration. The pigs, cats, and fowls, attracted their attention in so remarkable a manner, as to indicate a certainty of their not having seen any such animals before. A sailor threw them all into the most violent 67 fit of jumping and shouting, by walking upon his hands along the deck. But nothing seemed to fix their attention so much as Captain Stopford’s amputated arm[14]: they satisfied themselves, by feeling the stump, that the arm was actually deficient, and then appeared to wonder how it could have been lost: but when I made signs to them that it had been severed by a saw, to the credit of their feelings, I must state, that commiseration was depicted on every countenance. We did not perceive an instance, either of man, woman, or child, amongst them, who was in any way crippled or deformed.

After breakfast, it was proposed that we should go on shore, and a party accordingly made: we were all well armed, as a precaution against treachery; because this people have been particularly accused of a disposition that way,—whether with or without reason, it is impossible for me positively to say. An Esquimaux, who had bartered his very last covering away for some bauble, went with us, as a sort of pilot. On our way to the shore, we met two of the large women’s boats; each steered, as usual, by an old man. They expressed great joy at meeting with us, by singing, shouting, and clapping their hands; and instead of proceeding on toward the ships, they turned their boats, and followed us to the shore. The coast appears to be completely fringed with small rocky islands, and these no doubt form a shelter to many good harbours; but the shores of Hudson’s Straits have never been thoroughly examined, although a small 69 vessel might accomplish the task in two summers, with ease: indeed, a voyage for this purpose would, if well conducted, turn out advantageously, in a mercantile point of view; for although the Hudson’s-Bay Company’s ships do not procure much oil or whalebone from the Esquimaux, it is because they have but little intercourse with this people, and perhaps with only one particular tribe: yet it might be very profitable to any merchant to send a small strong brig into Hudson’s Straits, early in the month of June, so as to reach Cape Saddle-Back before the Company’s ships arrive. The Hudson’s-Bay Company would not wish to interrupt so laudable an attempt towards opening a free intercourse with the wild Esquimaux in those seas; because the profits they derive from the traffic in question are comparatively trifling, when put in competition with the other more important objects of their annual voyage. A vessel intended for this employ should 70 not remain later than the beginning of October in the Straits; and she ought to be well provided with saws, iron lances, harpoons, files, open knives, kettles, spoons, hatchets, and a few beads and looking-glasses. By coasting along both sides of the Straits, and as far to the southward of Cape Diggs or Cape Smith, she might doubtless gather thirty or forty tons of good oil, besides whalebone and a few skins. But the Master of a vessel, during such an expedition, should be particularly cautious in not trusting a boat on shore, unless well armed; and by no means ought he to admit more than two or three Esquimaux at the same time into his vessel, however friendly they might appear to be.

But to return to our party, whom I left pulling in for the shore, under the guidance of the naked Esquimaux, who continued pointing for us to proceed still farther to 71 the west, where some natives, from the bottom of a creek, waved their hands for us to approach. A sort of expostulation took place between these people and our conductor, by which it seemed, that the former did not wish us to proceed any farther to the west. We therefore landed, but walked about some time without observing any habitations; although, from the deers’ bones and ashes which lay scattered about the hills, it was evident that a party had not long quitted the spot. From appearances upon the hills, we had reason to suppose that rabbits must be abundant; and we were gradually receding from the sea shore in search of them, when our guide stopped short, and would not be prevailed upon, by any entreaties, to accompany us farther. We could not guess the cause of this extra-ordinary conduct; but not wishing to give any offence to the natives, we turned about, and descended again to our boats. On our 72 way to the beach, we were joined by some young girls, to whom we had been, perhaps, rather pointedly attentive on board the ships: they continued to pester us with the continual whine of this people, repeating incessantly the word “Pillitay! pillitay! pillitay!” signifying “Give us something:” and having now stripped us of every thing, by their solicitations, they only seemed to have acquired an incitement to make new demands. It is generally the case with all barbarous nations, that the receiving of a gift appears to them to confer a right to levy fresh contributions: therefore, in all dealings with savages, it is adviseable to teach them that something will be expected in return for every present bestowed; and the equivalent should be strenuously insisted upon, let it be of ever so trifling a nature. A departure from this rule may, indeed, be necessary in the first opening of a communication with a strange 73 people; but, even then, the presents ought only to be bestowed on the principal chieftains, priests, and women.

As we were upon the point of re-embarking, one of our party offered to a young girl, who stood on the beach, a pinch of snuff; shewing her, at the same time, how it was to be used. She imitated her instructor with great exactness, giving a hearty sniff; but it was attended with rather a violent effect; a torrent of blood instantly gushing from her nose. Entertaining some apprehensions lest the natives should imagine that we had been guilty of a premeditated injury to the poor girl, we all made a point of taking snuff before her: this had the desired effect, in convincing them that no serious evil was to be apprehended; and the young woman went, at my request, to wash her nose in a neighbouring pool. Unfortunately, the cold water produced a contrary effect to what was 74 intended; the blood again streaming from her nose: yet so far was this mild creature from being offended, that she smilingly held forth her hand to me, with the old exclamation of “Pillitay! (Give).” I cut two brass buttons from my coat, and gave them to her; and with this atonement she was quite satisfied. The fact is, as we afterwards discovered, that bleeding at the nose is a most common incident among the Esquimaux; and it is certain to follow the least exertion. Possibly this may also be occasioned by the quantities of raw flesh they devour daily.

Perhaps some readers may deem an incident like the foregoing of too trifling a description to merit a recital; but the manners, dispositions, and customs of a wild people may be better judged of from a simple relation of the most trivial circumstances, than from any inferences which the narrator himself 75 might presume to draw from them: therefore I would run the chance of being thought jejune, or even tedious, rather than incur the greater risk of misleading others by my own weak conclusions.

Embarking again, we pulled along shore, towards the west, among barren rocky islands, until we at last got sight of some huts on an eminence at the bottom of a creek; and putting ashore, we examined them minutely. They are more properly tents than huts, because they are erected much after the fashion of a marquee: a triangle supports the tent at one end, and two poles, fastened at the top, at the other: over all is thrown a covering of seals’-skins sewed together, the hair being scraped off: they are 76 equally impervious to air or water, and the light is much the same as in the interior of an European linen tent. At the lower end of their dwellings is a flap of seal’s-skin, left loose, to answer the purpose of a door; and when this is thrown back, a person must stoop low to enter. If a whole family happen to be absent from their home at the same time, the only security for their property, during the time they are away, consists in a few loose stones piled against the flap of seal-skin which covers the entrance to the tent: and although they be not rigidly honest towards strangers, yet the Esquimaux appear to have a great respect for each other’s property. At the top of their huts is a piece of wood, in an horizontal position, for the purpose of supporting slips of the sea-horse’s hide to dry in the sun; and of this hide they form a sort of rope, possessing uncommon strength, and useful to them in a variety of ways.

With respect to the interior of their habitations, it is a general custom to appropriate the lower end or entrance of the tent to answer the purpose of a larder, where all their delicacies are displayed; such as, deer’s flesh, oil, and whale blubber. The upper end of the tent, under the triangle, was thickly carpeted with skins of different animals, particularly the deer, and it is set apart for their resting and sleeping place. I noticed, that whenever I entered a tent, which had not been previously visited by any of our party, the owner of it ran forward, with great precipitation, to conceal something under the skins at the farther end of the tent. Curiosity prompted me to inquire into this mysterious conduct; and, on removing the skins, I discovered his bow and arrows, in a sort of seal-skin quiver. The owner stood quite tranquil during my search, and he did not appear angry when the arms were produced; but 78 when I offered him a knife, with the usual expression, “Chymo (barter),” he smiled, as I thought, rather suspiciously; and taking the quiver gently out of my hand, he replaced it under the skins; at the same time, offering me an unfinished bow, without a string, in exchange for the knife. As often as I continued to point to the quiver, and make signs that I wished to purchase the set complete, he seemed to feel confused, and endeavoured instantly to draw off my attention from the subject. I tried at each tent, with no better success; and it struck me, from appearances, that the Esquimaux have some superstitious veneration for their bows and arrows: but their hiding them may be intended as a compliment to their visitors, or an assurance of their security whilst under that roof. None of the canoes that visited us, during our stay in Hudson’s Straits, had either bow or arrows on board; consequently, 79 they are only used by the Esquimaux in their wars, and not for the purpose of killing birds or fishes. After having said this respecting their singular attachment to their weapons, perhaps it will be expected that those articles are curiously manufactured and ornamented: but the bow is merely made of two pieces of plain wood, firmly corded together, and rarely strengthened at the back with thongs of the sea-horse’s hide; the string is formed of two slips of hide or dried gut; the arrows are headed, either with iron, sea-horse’s teeth, sea-unicorn’s horn, or, in some few instances, with stone[15]; and the whole fabrication of the bow and arrows does not surpass the workmanship of an English school-boy.

In one of their tents, I saw a female far advanced in pregnancy; she was sitting upon the ground, closely wrapt in skins as high as her hips; and during the whole of my stay, she never attempted to rise. It may now be proper to relate an anecdote of a very interesting nature; which I received upon such indisputable authority, that it will not admit of a doubt, as to its veracity.

The land to the northward of Churchill Factory, in Hudson’s Bay, is inhabited by Esquimaux, who, contrary to the general customs of this people, employ themselves in hunting. They carry their furs annually to Churchill Factory, for the purpose of traffic. In one of their periodical visits, a young woman was seen amongst them, having a sickly infant in her arms, respecting whose health she appeared to be particularly solicitous; and 81 as some of the domesticated Indian women in the factory, belonging to the nation of Cree Indians, partly understood the Esquimaux tongue, the young woman explained to them, that, as the infant was her first-born child, if it should unfortunately die, her husband would undoubtedly put her to death. The infant expired shortly after this explanation took place; and some Europeans visiting the Esquimaux encampment a day or two afterwards, made inquiries respecting the unhappy mother; when the Indians silently pointed to the spot where the poor victim was interred!

This circumstance has given rise to an assertion, that if a first-born child die before it reaches a particular age, the mother is certain of being immolated, for a supposed want of attention to her infant. I had no means of ascertaining this singular custom myself; but I have before observed, that there did not appear either 82 sickly or deformed child or adult amongst them.

Their fire-places, as before stated, are outside the tents; and they have no need of any in the interior, as the seal-skins that cover them are like parchment oiled, and will not admit the wind, nor give egress to the breath; therefore their habitations are not only warm, but at mid-day, when I visited them, they were oppressively hot. With respect to their winter residence, I can say little or nothing. Most people suppose that they live in caves, by lamp-light; but the Abbé Raynal, who mentions the Esquimaux in his History of the East and West Indies, is of a different opinion. As the Abbé is both correct and incorrect, in many points of which I had a good opportunity to judge, perhaps it may not be amiss to give an extract from the part of his work relating to the Esquimaux Indians.

“This sterility of Nature extends itself to every thing. The human race are few in number, and scarce any of its individuals above four feet high. Their heads bear the same enormous proportion to their bodies as those of children: the smallness of their feet makes them awkward and tottering in their gait: small hands, and a round mouth, which in Europe are reckoned a beauty, seem almost a deformity in these people; because we see nothing here but the effects of a weak organization, and of a cold that contracts and restrains the springs of growth, and is fatal to the progress of animal as well as vegetable life. Besides all this, their men, although they have neither hair nor beard, have the appearance of being old, even in their youth: this is partly occasioned by the formation of their lower lip, which is thick, fleshy, and projecting beyond the upper. Such are the Esquimaux, who inhabit not only 84 the coast of Labrador, from whence they have taken their name, but also all that tract of land which extends from the point of Bellisle to the most northern part of America.

“The inhabitants of Hudson’s-Bay have, like the Greenlanders, a flat face, with short, but not flattened noses; the pupil of their eyes yellow, and the iris black. Their women have marks of deformity peculiar to their sex; amongst others, very long and flabby breasts. This deformity, which is not natural, arises from their custom of giving suck to their children until they are five or six years old. They frequently carry their children on their shoulders, who pull their mothers’ breasts with their hands, and almost suspend themselves by them.

“It is not true, that there are races of Esquimaux entirely black, as has been 85 supposed, and afterwards pretended to be accounted for; neither do they live under ground. How should they dig into a soil, which the cold renders harder than stone? How is it possible they should live in caverns, where they would be infallibly drowned by the first melting of the snows? What, however, is certain, and almost equally surprising, is, that these people spend the winter under huts, run up in haste, and made of flints joined together by cements of ice, where they live without any other fire, but that of a lamp hung up in the middle of the shed, for the purpose of dressing their game, and the fish they feed upon. The heat of their blood and of their breath, added to the vapour arising from this small flame, is sufficient to make their huts as hot as stoves.

“The Esquimaux dwell constantly near 86 the sea, from whence they are supplied with all their provisions. Both their constitutions and complexions partake of the quality of their food. The flesh of the seal, which is their food, and the oil of the whale, which is their drink, give them an olive complexion, a strong smell of fish, an oily and tenacious sweat, and sometimes a sort of scaly leprosy. This last is probably the reason why the mothers have the same custom as the bears of licking their young ones.

“This nation, weak and degraded by nature, is, notwithstanding, most intrepid on a sea that is constantly dangerous. In boats, made and sewed together like so many borachio’s, but at the same time so well closed that it is impossible for the water to penetrate them, they follow the shoals of herrings through the whole 87 of their polar emigrations, and attack the whales and seals at the peril of their lives.

“One stroke of a whale’s tail is sufficient to drown a hundred of these assailants; and the seal is armed with teeth, to devour those he cannot drown: but the hunger of the Esquimaux is superior to the rage of these monsters. They have an inordinate thirst for the oil of the whale, which is necessary to preserve the heat in their stomachs, and defend them from the severity of the cold. Indeed, men, whales, birds, and all the quadrupeds and fishes of the North, are supplied by nature with a degree of fat, which prevents the muscles from freezing, and the blood from coagulating. Every thing in these Arctic regions is either oily or gummy, and even the trees are resinous.