* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Voices from the Dust

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: John Jeffery Farnol (1878-1952)

Date first posted: Jan. 18, 2017

Date last updated: Jan. 18, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170122

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

“To-day, my Lord, I go back to my cows”

VOICES FROM THE DUST

Being Romances of Old London

and of

THAT

which Never Dies

The GOOD lives on eternally

Only the baser thing can die

BY

JEFFERY FARNOL

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

H. R. MILLAR

TORONTO: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF

CANADA LIMITED, AT ST. MARTIN’S HOUSE

1932

COPYRIGHT

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY R. & R. CLARK, LIMITED, EDINBURGH

| TO | |

| MY OLD FRIEND | |

| HARRY PRESTON | |

| THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED | |

| WITH | |

| AFFECTIONATE REGARDS | |

| SUSSEX, 1932 | JEFFERY FARNOL |

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Few are there of all the hurrying thousands passing daily who ever trouble to glance at this Stone of London Town in its dark and dusty corner, this relic of long-forgotten peoples and illimitable years, whose origin is lost in the dust of speeding centuries. Whence came it? What was it? Who shall say? The fetish, mayhap, of paleolithic man: a stone of sacrifice: a pagan altar? But we know it, lastly, as the measuring-stone for a Roman province.

To-day it lies, dim and grim, behind its rusting iron bars, waiting, as it has always done, for the end of Time,—history concrete for such as possess the eye of imagination, and which having no tongue may yet speak to such few as may hear.

As thus:

It is a day of early summer, and the genial sun sparkles on bright mail and crested helmet, it twinkles on broad spearhead and gleams upon spade and mattock where men labour upon a road that, piercing thicket, swamp, and dense-tangled forest, shall join this hard-won province of Britain with the glory of imperial Rome.

And these soldier-labourers, being also Romans, do not scamp the business, for see now!

They drive two parallel furrows the proposed width of the road: they scoop out the earth between, they pack and ram this excavation with fine earth,—and this is the pavimentum. Upon this they now lay small squared stones precisely arranged and mortared,—and this is the statumen. Upon this again they spread lime, chalk, and broken tiles pounded hard,—and this is the nucleus. Lastly and with extreme care they set large flat stones cut square or polygon-shaped,—and this is the summa crusta.

What wonder that such roads have been enduring marvels ever since?

Now, as these Roman legionaries bend to their travail or march upon their wards, come two men, young officers by their mien and look, for, though their bright armour is very plain, their helmets bear lofty crests.

“Barbarians, I tell thee, Metellus,” cried the younger with a gesture of youthful scorn. “Yet must we go ever on watch and ward, day and night—Why? Why?”

“Thou’rt new to Britain, Honorius, but shalt see for thyself anon!” answered Metellus, smiling grimly. “When hast fronted the wild rush of their war-chariots, seen their murderous scythe-blades dripping blood, ’twill suffice thee, Honorius, thou’lt know!”

“Nay, I’ve heard o’ them, man.”

“And shalt doubtless see, anon.”

“A barbarian rabblement!” snorted the young Honorius.

“Yet Britons!” nodded his comrade, “and I ne’er saw Briton yet that loved not fight. Ay, barbarians are they . . . and yet——” Metellus glanced away to the distant, thick-wooded heights, and the dreamy eyes beneath his glittering helmet seemed suddenly at odds with his hawk-nose and grim mouth.

“Thou hast lived among them, Metellus, I hear.”

“Three months among the Regni, to exchange hostages. I have their speech and——” Metellus stiffened suddenly, his eye grew keen as from the camp away down the road a trumpet blared instant hoarse alarm.

“What is it?” cried Honorius, clapping hand to sword.

“Battle!” answered Metellus, and turned to order his company, where now, in place of spade and mattock, shield and pilum glittered and swayed. For, suddenly, from those wooded heights came a vague stir, a hum that swelled to clamour, to wild and fierce uproar: and forth of those gloomy woods leapt horses and chariots sweeping down with ever-increasing speed, hoofs thundering, and wheels rumbling—rattling wheels whose creaking hubs bore long, curved blades flashing evilly. So down roared these chariots of death, driven by men who laughed and shouted amain, brandishing spears, axes, or long bronze swords.

But upon the road all was silent where these veteran ranks of Rome, shoulder to shoulder, back to back, shields before and spears advanced, stood grim and silent to stem the wild fury of that thunderous onset.

A still and breathless moment, and then upon the road was raving pandemonium, dust and blood and death. For here are the chariots! Their drivers hurl javelins, they thrust with spear or smite with sword, they leap upon their horses’ backs, they step upon the pole that they may strike and kill the better. The Roman front sways, totters, is riven asunder, and the blood-spattered chariots are through and away. And now, down upon these broken ranks the British horsemen charge. But a trumpet shrills, the men of Rome close up, stand firm, and British horse and rider go down before the levelled spears or recoil before this iron discipline. So stood the Romans, silent, grim, and orderly as before; only now outstretched upon the road were men who wailed dismally or lay very mute and still, with litter of chariots shattered or overturned, and dead or dying horses.

Then Metellus, knowing the attack was sped, wiped and sheathed his sword and looked about for his young comrade Honorius, and presently espied him beneath a broken chariot, his youthful body hatefully mangled. Stooping, he touched his pallid cheek. The dying youth opened dimming eyes and sighed.

“Metellus, thou wert . . . right. These Britons are surely men. As for me . . . ah, well! . . . it is . . . for Rome. . . .”

Thus, then, they fought and laboured upon the road, these men of Rome, in heat and cold, wetting it with their sweat, splashing it with their blood, and dying now and then—but the road went on. For Rome’s mighty fist, having grasped, held fast awhile: before invincible pilum, short sword, and rigid discipline the proud tribes, Regni, Silures, and Bibroci, gave back, slowly, sullenly, and vanished amid their impenetrable country of marsh and forest, beaten yet unconquered, and biding their time.

Thus, upon a summer’s eve, young Bran, son of Cadwallan, King of the Regni, tightened the strings of his bronze war-helm and, leaning upon his sword, peered down through quivering leaves and above dense-tangled thickets to where in the vale below broad and white and straight as arrow ran the great new road.

“Plague seize ’em!” he growled fiercely. “They should be in sight ere now. What shall keep ’em, think ye?” And, from the denser wood behind, came a harsh yet jovial voice in answer, the voice of Tryggan, his foster-father, old in war and accounted wise in counsel:

“Patience, fosterling! They were ordered for Anderida, we know, and, being Romans, come they will.”

“Romans—ha, curse them!” muttered young Bran, lifting his knotted fist. “And in especial do I curse Metellus the centurion!”

“Thy hate for him waxeth ever, Bran?”

“Hourly, since first he plagued my sight. Thrice have we met in battle, and yet he lives. And my cousin Fraya looks on him over-kindly—and he a Roman!”

“Why, he is a comely youngling, Bran.”

“Yet a Roman! And therefore to be hated. So pray I the God o’ the Grove, yea, the Spirit o’ the running water, I meet him in fight this day! Think you my father shall be ready?”

“Yea, verily! Trust Cadwallan. Yonder he lies across the valley with all his powers, yet not so much as a blink of helm or spear! And moreover——Stay! What’s there? Now watch, eyes all—hearken!”

Leaves a-flutter in the gentle wind, a bird carolling joyously against the blue, a stealthy rustling sound amid the underbrush hard by, where armed men crept . . . and then above all this, faint and far, a throb of rhythmic sound drawing nearer, louder, until it grew to the rattle and thud of slung shield and spear, with the short, quick tramp of marching Roman infantry. Young Bran smiled fiercely and, tossing back his long fair hair, glanced down at the eager faces of his crouching followers and drew his sword.

“Be ready, men of the Regni!” he muttered. “This hour shall your thirsty swords drink deep. Where I go, follow and kill!”

“No mercy, then, princeling?” murmured grey-headed Tryggan.

“Mercy?” snarled Bran. “Ha, meseemeth you also look too kindly on these accursed Romans! Kill, I charge ye, kill all! Yet stay! Spare only Metellus, for he is mine; him will I give to the priests for our Sacred Fire. So—pass the word! And watch for my signal.”

Far off upon the road there presently appeared a small company of soldiers, crested helmet and spearhead blinking redly in the sunset glow, a serried company, their files trim and orderly, their short, quick stride bringing them rapidly nearer, until these many hidden eyes might descry grim faces and sturdy limbs and one who marched before accoutred like his fellows, except that his helmet bore a loftier crest. Nearer they swung, rank on rank, veterans all by their showing—lean, sinewy fellows with eyes bright as their armour.

“Come!” roared Bran and leaped, long sword aloft—and up from bracken and sheltering thicket sprang his fierce company and followed hot-foot where he led.

From the road a trumpet sounded, shields flashed and spearheads glittered as the Romans wheeled to meet the charge.

Though surrounded and beset on all sides the Roman columns held fast; British long-swords whirled and fell, but the serried Roman spears swayed and thrust, and the short, two-edged swords bit deep, and thrice, for all their desperate courage, the Britons were flung back.

“Metellus!” roared Bran, raging amid the fray. “Ha, Metellus, I’m for you. Come!”

“So ho, Bran!” answered the hated voice of Metellus, rising loud and clear above the din. “Come, then, and taste again of Roman steel.” But between them was a rocking close-locked press, and so they raged for each other in vain.

Then was an added tumult as down from the opposite steep charged Cadwallan with all his following. And presently, hemmed in thus at every point, the Roman ranks swayed, staggered, broke at last and were smitten and trampled into the bloody dust.

Breathless, half-blind with sweat, young Bran beheld a lofty crest that reeled and drooped beneath a hail of blows, and, roaring, he leapt and bestrode Metellus the centurion as he fell.

“Off!” he gasped, beating back his fellows. “ ’Tis the accursed Metellus! Off, I say! He is mine!”

So the fierce British warriors drew sullenly away and stood gazing at conquered and conqueror in a dark and scowling ring.

Coming weakly to an elbow, Metellus peered up at Bran from beneath his battered helmet and, blowing blood from his lips, laughed faintly.

“What, Bran, dost live yet? Then here and now I die. . . . Strike, Briton!”

“Not so!” answered Bran, stooping to glare into that bloody face. “Dog of a Roman, my hate is all too large to slay thee gently so. Thine shall be a death less kindly.”

Then was sudden shout, the ring of warriors parted, and so came Cadwallan the king, trampling and spurning the Roman dead beneath his gold-studded sandals.

“Well sped, my son!” he cried in his great booming voice. “A right noble fray, boy! What have ye there under foot? Why, by the Sacred Oak, ’tis the proud Metellus! How now, Oh noble Roman? What’s the word, Sir Daintiness?”

“Death, Majesty!” answered Metellus, dabbing at the gash above his brow. “Death beyond all doubting.”

“Death indeed since Roman you be.”

“Ay, good my father!” nodded Bran. “But, noble sire, I crave as boon the manner of his dying.”

“Why, verily, boy, so death it be. Yet, for thy deeds this day boon shouldst have, were it—even his life.”

“Life?” cried Bran, spurning his foe with passionate foot. “Nay, father and king, he shall to the Stone of Sacrifice, the Sacred Fire shall lick him, sire, ay, devour him before my eyes.”

“The Fire?” repeated Cadwallan, thumbing his great chin, and glancing askance at his fierce son. “The Fire, boy? ’Tis an evil death and . . . Well, so be it! Take up the prisoner.”

“Ay, lift him, bear him tenderly!” cried young Bran. “Cut withies for a litter that he travel soft. Ha, dog of a Roman, I hate ye so perfectly I’ll cherish ye with loving care lest Death snatch ye from me too soon!”

“Barbarian!” retorted Metellus faintly. “Oh Bran, I despise thee so vastly I had rather die than suffer thy fellowship!”

Julius Octavius Metellus, centurion of the Seventh, his hurts duly tended, full fed, close prisoned yet well cared for that he might prove hearty and strong to endure the full anguish of his dying, stood looking through the bars of his cell with eyes eager and expectant, yet saw no more than this: a green garth shady with trees, and in the midst an oak, mighty with age, whose gnarled branches shaded a stone something wider and longer than a man; a stone rough-hewn and blotched, here and there, with stains other than those of weather.

Philosophic in adversity and something of a poet, he composed verses of love and life and death, but, being also young, more especially of love and death; and so passed the long hours.

Daily he looked forth of his prison-bars, and always with the same wistful expectancy, only to behold the aged tree and grimly stone, particularly the stone, so that he came to know it very well, its every evil blotch—at which times his Muse led him deathwards.

At last, upon an evening when cow-bells tinkled drowsily from lush meads, he saw her. Tall and proud and gracious as he had dreamed her, radiant in young beauty from red-bronze hair to slim, buskined foot, her slender middle clasped by a jewelled girdle that clung about her loveliness as if it too had sense enough to love her. Against her rounded bosom she bore a sheaf of new-gathered flowers; coming to that stone beneath the oak she there disposed her flowers, hiding those ugly blotches ’neath their beauty and at this moment she turned and gazed up at the prisoner and, seeing the adoration of his eyes, she reached out her hand, her red lips parted in a tender smile—but even then came the distant note of a hunting-horn, the baying of hounds, and with a lingering, eloquent look she sped away, leaving that grimly stone a thing of beauty and in the prisoner’s heart a song of joy.

This night came sturdy, jovial Tryggan, something stealthily, and, closing the massive door behind him, set broad back thereto and nodded. Said he:

“Metellus, thou’rt a Roman and therefore ’tis certain, something of a dog. Yet, being dog of war, I dare to think thee something also of a man, and so it is that one I love would not have thee die awhile, deeming thee fit for kinder things, mayhap.”

“Oh man,” said Metellus, rising to greet him, “Oh Tryggan, what’s your meaning?”

“Our princess! The maid Fraya.”

Now at this Metellus bowed his head, his eyes very bright.

“Fraya!” he whispered. “By all the great gods——”

“Stint thine oaths, Roman, and hearken! She deeming thee worthy sweeter thing than death—and such a death!—I needs must think the like——”

“Ah, generous Tryggan——”

“Nay, Roman, she plagues me, she plagues me unceasing; moreover she is . . . dear to me! So to-night when the moon tops the oak grove yonder, be waking! I command the guard this night—woe’s me.” So saying, Tryggan sighed, nodded, and was gone.

And now Metellus, philosophical no longer, paced his cell with impatient foot, dreaming breathlessly of what was to be, and each time he scanned the climbing moon the name “Fraya” was on his lip. Up, up, in serene, white majesty rose the full-orbed moon, yet slower surely than ever in all the memory of man; up and up in ever-brightening glory until it topped the oaks at last. The great door swung heavily open; a soft voice breathed:

“Metellus . . . Oh Julius!”

“Fraya—dear love!” he whispered, and then she was in his arms, trembling to the passion of his kisses.

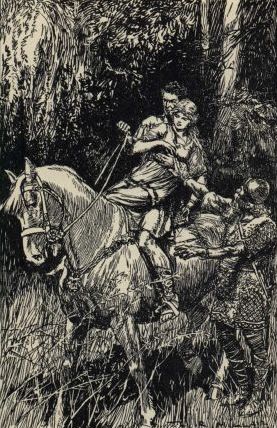

“Haste! Oh, haste!” she panted. “Give me thy hand. Now—hush thee!” Thus sped they side by side, and never a sound until they were out beneath the moon, running hand in hand; so she guided him until, within a place of shadow, they came on Tryggan holding a tall white horse.

“Up, Roman!” he whispered fiercely. “Up and away! I see a light where none should be, so here’s danger for us all in tarrying. Away, Fraya!”

“Then will I go with thee, Julius,” she whispered.

“No!” quoth Tryggan. “ ’Twas not so agreed. Away, girl! Nay, little one, he but rides to his death; ay, so—and his death shall be thine——”

“Then shall it be sweetly welcome! Julius, take me, for——”

The stilly night was riven by a sudden wild shout and growing hubbub as the fugitive sprang to saddle.

“Oh!” cried Fraya. “Oh beloved Julius, leave me not to perish alone!”

“Never think it!” he answered, and stooping, caught and swung her up before him.

“Princess,” groaned Tryggan in despair, “thou’rt betrayed. The Roman rides to death, and thou——”

“Spur!” cried Fraya, as came a rush of feet, and, turning, Metellus had brief vision of Bran’s hated face, and then the great horse leapt, reared, and was away.

Fast they rode across an open mead, through rustling wood, by forest glades, plunging deep and ever deeper into the leafy wilderness; yet here, dark though it was, Fraya’s white hand directed their going. Even so needs must he stoop oft-times to kiss her eyes, her cheek, her silky hair, murmuring words of adoration and vows of deathless love, until, what with the wonder of their young passion and the glamour of this midsummer night, they clean forgot their peril.

“Wilt love me always?” she pleaded. “Wilt honour me though I am a Briton?”

“To the end of my life, ay, and beyond!” he vowed. “Oh my Fraya, to the end of Time itself!”

“When didst love me first, Metellus?”

“When first I saw thee.”

“ ’Twas when thou didst come in the matter of hostages,” she murmured happily. “Oh, I mind it well—thy bright armour, thy dear, kind eyes! It seems long since.”

“And yet, my Fraya, I do surely think I loved thee in my boyish dreams, long ere I came to Britain, long ere these bodily eyes beheld thy beauty and loveliness.”

“Ah, marvellous strange!” she murmured. “ ’Twas even so I dreamed of thee, thy dear, dark head, these proud, gentle eyes, thy gait—all these were nothing strange to me.”

“So, Fraya, dear, mine Heart, mayhap we have met and loved ere this . . . in some other world, some other age. Who knoweth—who shall say?”

“Hearken!” she cried suddenly, clasping him in the protecting passion of her arms. “Dost hear?”

“Nothing, my Heart.”

“Ay, but I did! Ah—’tis there again!” she cried, as, faint with distance, rose the shrill clamour of a horn. “ ’Tis Bran!” she gasped. “ ’Tis Bran, I know his moot. Now ride amain. Oh Metellus, speed, for death surely follows hard!”

“Fear not, loved soul, they are yet afar.”

“Nay, but Bran knoweth these woodlands, every glade and clearing. . . .”

And now, by reason of her terrors, Fraya misguided him, and going astray, they blundered amid mazy thickets and floundered into perilous slough and, or ever they won free, their pursuers were in full cry.

“Julius, beloved,” she murmured, after some while of furious going, “they are close on us! I fear me ’tis the end. We have found again this great wonder of our love but to lose it awhile.”

“Ha, they ride but three!” cried Metellus, glancing back. “Oh, for a sword! Yet if indeed I must lose thee, Beloved, willingly I’ll die also. Yet would I smite Bran from life first!”

“Ah, Metellus, ’tis a deadly thing, this hate betwixt ye twain!”

“And most strange, my Fraya, for as I seemed born loving thee, so with life came hate for him.”

“Yet hate is vain and empty thing, Metellus; ’tis waste of life.”

“ ’Tis death!” he answered twixt shut teeth. “To him or me.”

“To both!” she sighed. “To both, full oft, till Death at last shall lesson ye, and your hate be changed to love and amity. I see, I know! Life floweth ever like Time itself! . . . And now, ah, my Julius, kiss me farewell awhile, for here must we die . . . yet not for long, since Life is stronger than Death.”

“Why, how meanest thou, my Heart?”

“See! Yonder is chasm no horse may leap, so let us here await Death. Let us go out into the dark together until together we find Life again.”

But Metellus, rising in his stirrups, surveyed that dreadful gulf; then, clasping Fraya to his heart, he set his teeth and, with voice and hand and goading heel, urged the great white horse faster . . . faster yet . . . then, shouting suddenly, he plied hand and heel anew, lifting the mighty stallion with cunning wrist. . . . A rush of wind! A jarring shock! A wild scramble of desperate hoofs, and the brave horse, winning to level ground, gasped and fell. Half-dazed, Metellus staggered to his feet uttering a glad cry to see Fraya already upon her knees.

“Safe!” he gasped, lifting her in eager arms. “The Gods are with us, Beloved!”

But, speaking no word, she pointed, and, glancing thitherward, he saw Bran rein up his rearing steed upon the opposite brink of the chasm, saw him whirl up his long arm . . . and in that moment Fraya flung herself upon Metellus, clasped him in the shelter of her arms, with words of passionate love ending in an awful, sobbing groan; and looking down he saw her transfixed by the javelin, beheld his hands bedabbled with her innocent blood.

“Die, then, traitorous wanton!” roared Bran and, wheeling his horse, galloped away.

“Ah, Metellus,” she gasped, “Oh Julius! our time of love . . . is not . . . yet. Nay, grieve not, I . . . shall wait for thee . . . shall wait to . . . love thee again . . . at better time. But now . . . kiss me farewell awhile . . . a little . . . little . . . while——”

And so Metellus kissed her and, with her mouth on his, she died.

After some while he gathered bracken-fern and therewith made a bed, and very reverently laid her there, wetting her pale face with his tears.

“Thy bridal couch, Beloved!” he whispered. “And so . . . until we meet again . . . fare thee well!”

And thus he left her with the day-spring bright upon her young loveliness.

The circling years rolled, and, despite battle, raid, and deadly ambushment, the great road crept on.

And the proprætor Julius, Octavius Metellus, scarred veteran of the ceaseless wars, minor poet, great soldier, and famous engineer, grey-headed, haggard of face and sterner than of yore, stood in the midst of Augusta, the proud walled city, his officers grouped attentive about him, for he was busied upon many concerns and amongst them the laying out of divers new streets and fortifications.

“Here,” said he, striking heel to ground, “here, as I reckon it, is the very heart of our city as she is and shall be. So here, sirs, will we set up a stone that shall be a notable mark for the measuring of our city to her walls and beyond. So many miles from this stone east or west, north or south, reaching on even unto the very gates of that Rome I shall ne’er see more. Here, then, shall stand yon stone to remain henceforth—ay, long after we are forgot. See to it, sirs, and——”

A trumpet brayed suddenly, armour rang, feet tramped and were still.

“Ah, what’s here? You, Vitellius, go see. Nay, here comes one shall tell us.”

A tall centurion strode up, grimed with battle and dusty from sandal to plume.

“Why, it is Spartacus of the Seventh, I think?”

“The same, sir, with prisoners new taken out o’ the south.”

“Let them approach.”

So came they, a miserable company, battered, bloody, drooping in their bonds, reeling in their gait; one only of whom bore his head proudly aloft, a very tall man he, fair-haired, with fierce blue eyes, who, beholding the grey-headed, lean-faced proprætor, started and glared, his look aflame with sudden, passionate hate.

“Dog of a Roman!” he cried, uplifting chained fists. “I am Bran, King of the Regni, prisoner,—yet unconquered still, scorning Rome and all her works and hating thee, Metellus, in this my death-hour—hating thee in life present and to be! So, thus I spit on and defy thee, Roman dog!”

“Slayer of women!” said Metellus, his haggard brow unruffled, his voice serene. “Truly Death hath found thee. Strike me off his kingly head!”

“Here, sir?” enquired one.

“Indeed! Our stone yonder shall serve, for I must see him die.”

“Watch then, dog!” laughed Bran, turning towards the great stone that lay hard by, a stone something wider and longer than a man. “We Britons die as we live, unfearing. Well, Death taketh us all somewhen, Roman, me to-day, thee hereafter. But somewhere, at some time, we shall live again to hate and fight anew—and next time I’ll watch thee die! So look to it thou Roman dog!”

Then Bran, unclasping from brawny throat his golden torque, cast it aside, glanced up to heaven and round about, laughed defiantly, and falling on his knees before the stone, bowed his unconquered head to the stroke. . . .

And presently they set up the great stone, wet with the blood of the last British King, planting it deep, for the useful purposes of survey: a mark for unborn generations to wonder at, a mark that, broken and battered, stands to-day for each and all to see—the imperishable London Stone.

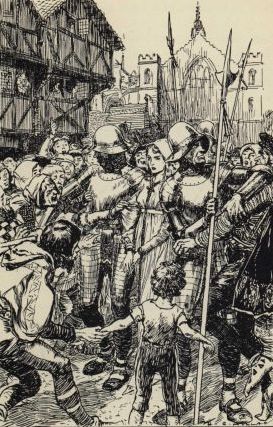

“The Roman rides to death”

Since that pale, pious man—feeble king yet potent saint—called Edward the Confessor was laid in grave within his new great minster on Thorney Isle, the place has been deemed holy, a sanctuary for the hunted wretch, a place for prayer and the miraculous cure of ills, bodily and mental.

Had these grey walls the faculty of speech, what tales they might recount, what unrecorded stories of life and death, of joy and grief, what long-forgotten tragedies! Yet surely none more tremendous than that of those dim days when Saxon England fell.

The roar and tumult of Senlac’s bloody slopes, those cries of victory and death, have long since passed away. The shame of slavery, the long years of bitter oppression have gone, thank God, and are forgotten. Proud Norman and hardy Saxon, uniting, have left descendants as proud, as courageous, yet greater than either, still marching in the van of the nations. To-day Saxon Harold is only a name, Norman William but a memory, yet how real were they, those virile ancestors of ours, and how very much alive upon that dim, far-distant October morning when: . . .

Young Godric of Brandon Holm leaned across the Saxon breastwork, that inner shield-wall and last defence manned by the chosen valour of England, where flew King Harold’s golden banner, the begemmed Dragon Standard of Wessex.

A goodly man was this youthful thegn of Brandon, and very warlike in his gleaming helmet and ringed mail, as he stood shading fierce blue eyes from the early sun of this fateful morning to stare away across gentle, grassy slopes, over valley and misty swamp, to that opposite range of hills where, beneath waving gonfanon, pennon, and fluttering banderol, rank upon rank in three great companies, was marshalled the eager host of William, Duke of Normandy.

Long stood young Godric gazing on that dark array, heedless of the unceasing stir about him where, mustered beneath the standard, stood the lithesmen of London, while far to left and right, above the rampart of shields, mail glittered, broadsword and axe-head gleamed as these men of Saxon England, King Harold’s own housecarls, his kin and chosen jarls and thegns, strengthened their defences and made them ready against the coming onset.

A great hand clapped down on Godric’s mailed shoulder, and starting round he beheld the smiling, ruddy face of Wiglaf Ericson, the mighty thegn of Bourne, a cheery giant, grey eyes twinkling beneath bright helm, long sword on thigh, and ponderous war-axe slung about his brawny neck.

“What, Godric!” quoth he. “D’ye peak, lad, d’ye pine?”

“Tush, man!” answered Godric, scowling. “Amid yon teeming thousands I seek me a pennon, the blue saltire of de Broc, my sworn and hated foe.”

“They be all thy foes, lad.”

“But, in especial, one!”

“Ha, dost mean Gilles de Broc, him thou dost name my rival and the cause o’ thy sweet sister Githa’s sighs?”

“Himself!”

“Then short rede to him this day, say I!” quoth the gigantic Wiglaf, his good-humoured visage darkening.

“Ay, verily!” nodded Godric fiercely. “Yonder he should ride ’neath the Pope-blessed banner of Duke William, being sib to him.”

“See!” cried Wiglaf, pointing. “The robber-rogues muster well, down yonder; and yet for all their brave showing they be more o’ monks than fighting-men,—shaven polls, d’ye see, and never a beard among ’em.”

“What fools say thus, Wiglaf?”

“Grimbald. He and his spies are in but now from viewing their array.”

“Then, sir, I say these same shavelings be stout knights all and lusty men-at-arms as we shall prove ere sundown. These be the pick and very flower of all Normandy, as I do know.”

“Ay, sooth, thou wert at the Norman’s court with our Harold ere we made him king. Ha, knights and men-at-arms, say you? Why, very well, say I,—for by the great rood at Thorney Minster, I’d liefer crack crown o’ lusty knight than monkish mazzard, ay, would I! Here shall be goodly fight—ha?”

“Never doubt it!” answered Godric, scowling at the Normans’ wide-flung battle-line. “And half our veteran levies beyond Humber! Verily Harold had been wiser to bide behind the walls of our London till England rallied to him. As ’tis, our force, the half of it, is but of rustics ill-armed, boors, serfs and the like——”

“Yet, being Saxons, lad, they should fight well and lustily.”

“And these Norman thieves out-man us three to one!”

“Well, by the Bones, the more honour to us, then!” cried Wiglaf, his golden beard bristling. “As for me, I’ve old Brainbiter here shall even the odds somewhat!” and he patted his great, broad-bladed battle-axe. “Ay, by the Blood, he wrought right well at Stamford fight and shall this day be good for ten, a score, ay, half a hundred o’ the dogs, an the gentle saints prove kind. Howbeit, an Wiglaf die he shall take a full tale o’ Normans for company.”

“Well, as for me, Wiglaf, content I’ll be with the life of single one——”

“Ha, by the Holy Nails! One, say ye? But a poor, scurvy one, lad?”

“But that one—mine enemy! To see him die ’neath mine axe! To feel him agonize upon my sword—ho, this shall suffice me!”

“Art a lusty hater, Godric, but to-day——”

“Hate?” cried the young jarl. “ ’Tis my life——”

“ ’Tis death, and the soul’s destruction!” said a voice, and to them came a grey friar, a small, lean man who limped.

“Away, shaveling!” cried Godric savagely. “Preach not to me. Hence, I say!” The friar drew a pace nearer:

“My son,” said he, gently, “needs must I preach to thee and all men the words of One that said ‘Love thine enemy.’ For by love only cometh salvation, and he that forgives his enemy findeth a friend.”

“Off!” cried young Godric. “Prate no more. I tell thee hate is the very soul of me!”

“So shall thy soul be changed, my son. For thou, great lord, like the humble serf, art very son of God, and He shall chasten thee.”

The gentle voice was lost in sudden shout swelling to a lusty Saxon cheer while sword, brown-bill, and broad axe flashed in welcome as up rode Harold the King with his brothers Gurth and Leofwine and, dismounting beneath the bejewelled banner, strode forward, a very comely, well-shaped man, light-treading despite weighty helm and bright-ringed hauberk.

“What, Godric—and thou, good Wiglaf! Greeting, noble lords!” quoth he, and gave a hand to each. But now were others, of high and low degree, eager to look upon their chosen king, to touch his hand and sue a word from him. So there beneath the banner Harold spake them, loud and clear:

“Ye men of mine, stout friends and comrades all, here stand we in arms this day for homes, for wives, and this, our land. Yonder crouch the Norman wolves to raven and destroy. Thus upon our swords doth rest the fate of all to us most dear. So, for the safety of our homes, the honour of our women, the glory of our race, let us smite, good comrades all, whiles life be ours. And now farewell, sirs. To your posts, and God defend us!”

And presently, as he stood, his quick, blue eyes glancing hither and yon, spake the mighty Gurth, and he sore troubled, for Gurth loved him beyond all men:

“Harold, good brother and king, the oath thou didst swear to Duke William upon most holy relics doth grieve us—us that love thee, and, in especial, myself——”

“Nay, Gurth, here was trick most base and vile!”

“Yet, lord—’twas an oath, and the relics very holy. Wherefore now, lest such great sacrilege bode ill for thee this day, go hence and leave us, that swore no oath, to fight——”

“Not so, Gurth, my brother. Ne’er will I stand by whiles others fight and . . . Ha, there sound their clarions!” cried Harold, and out flashed his sword. “Now smite we all for God and our right!”

And so with hoarse blare of trumpets, with thunderous Norman shouts of “Dex aide” and Saxon roar of “Harold and Holy Rood,” began this ever-memorable battle of Senlac that was to change the destiny of England and shake the very world.

All day long, from early morn to set of sun, the battle roared unceasing. Up and down, to and fro, surged this desperate conflict, until the trampled slope was churned to bloody mire thick-strewn with dead and wounded. Hour after hour headlong valour of attack was met by defence as unflinching and courageous until, before the battered shield-wall, the Norman dead lay piled, horse and man, in ghastly heaps.

Yet on came the invaders, nothing daunted, to smite and be smitten, launching their fiercest attacks where flew the Dragon banner, for here fought Harold the King with all his chosen, thegn and churl and serf with the bold citizens of London; here young Leofwine plied deadly spear, here smote the mighty Gurth, while, hard by, Wiglaf’s terrible axe rose and fell; and here, too, fierce Godric thrust with tireless arm, seeking ever the hated face of his enemy. So here was blood and death and shock of crashing blows until the sun went down. But the Saxon rampart, grimly stained and direly battered, showed still unbroken above the ever-growing heaps of Norman dead.

“Splendour of God!” cried Duke William, as his shattered columns recoiled at last before the resistless sweep of Saxon sword, brown-bill, and shearing axe. “Stand, sirs, stand! Behind ye is the sea, dishonour and death: before ye is life and a marvellous rich booty. On, sirs, on!”

But, wearied with the long and desperate affray, breathless, shaken and awed by those ghastly piles of dead, his mighty following stood sullenly at bay. Then to him rode his half-brother Ode, the fighting Bishop of Bayeux and held him a while in counsel.

“Oho, archers—archers!” roared William, and galloping among their scattered ranks, he snatched the nearest bow and setting arrow on string, shot it high in air to drop within the Saxon barriers.

“Launch me your shafts so!” he commanded.

Now the gigantic Wiglaf, ghastly with slaughter, leaned upon the long shaft of Brainbiter, whose great, dimmed blade showed notches here and there, and panted:

“Aho, Godric, what shall mean this respite, think ye?”

“Some cursed Norman trick!” gasped young Godric, staring at the blood oozing slowly through his riven mail.

“God send our Saxon hotheads be not lured from their defences!” quoth Harold the King, glancing right and left along their battered line.

“Ha, by the pyx, I’m dry!” mourned Wiglaf.

And then . . . down upon them rained the deadly arrow-shower, and, as men reeled and died, up, up against them once more, fierce and relentless, thundered the attack.

And now at the shield-barrier was close and bitter fray; and now it was also that, amid the reeling press, Godric at last beheld his enemy’s hated hawk-face, and cried aloud:

“Ho, Gilles—Gilles de Broc!” And Sir Gilles, seeing, would have turned aside, but his snorting war-horse bore him near, and thus fought they, sword to sword, till the raving battle tore them asunder; and when Godric, leaping upon the barrier, would have followed, Wiglaf’s mighty hand plucked him back.

And ever down upon them, from the darkening sky, rained the deadly arrows, and one most fateful of all! For, uttering a hoarse gasp of agony, King Harold dropped his bloody sword and reeled back and back till Godric, staying him with out-flung arm, saw him pierced through brow and eye with a quivering arrow. So stood the King a while, groaning in his anguish; then, plucking forth the shaft, stretched out hands that groped piteously.

“A sword!” he gasped. “A sword——!”

But, even then, the wall of shields was riven at last, the battle roared upon them, and Harold the King was down.

And so came dusk, lit by the glimmer of clashing steel, dreadful with cries of pain and thunder of trampling hoofs where horsemen leapt the shattered barriers, crushing alike the living and the dead. Yet still, amid that din and wild confusion, the Saxons, thegn and churl and men of London, fought back to back around the banner of their dying king.

“Godric . . . ho, lad—art there?”

“Ay, but here’s our end. Good-night to thee, bold Wiglaf. . . .”

“Verily, friend, here dieth . . . Saxon England. So . . . by the Blood . . . here dieth Saxon Wiglaf!”

So saying, the death-smitten giant whirled aloft his mighty axe and, roaring like a Berserk, leapt into the close-locked fray and was gone.

And now it was that bold Leofwine fell, and heroic Gurth, slaying, was slain.

Thus came night.

Now Godric, lying half-smothered beneath the dead, heard strange, small cries, and sudden, thin whimperings, for the roar of conflict had ceased at last. He beheld a flickering light, felt hands, strong yet kindly, lift him, and saw dimly a hawk-face, streaked with blood and sweat, beneath a dinted helmet.

“Ah . . . Gilles!” he gasped. “I yearned amain to slay thee, but . . . the fortune’s thine. So now, here’s my throat!”

“Nay, Godric, our fighting shall be done with henceforth, I pray.”

“Thou’rt a cursed Norman——”

“And thou a valiant Saxon. So let there be amity betwixt us and all kindliness . . . for Githa’s sweet sake.”

“Thou’rt hated foe!”

“And would be trusty friend.”

“So? Then . . . give me—death!”

“Take life.”

“Ah, God of Battles,” groaned Godric, “let me die a free man still!”

Then, with bloody head pillowed on his enemy’s mailed breast, young Godric, thegn of Brandon Holm, closed his eyes.

The noble Minster of Thorney, that we call Westminster Abbey, was new in those days and famous for its great rood or cross. And hither daily at sunset came Githa, Lady of Brandon Holm, to kneel before this cross and supplicate the divine mercy on her England, her brother Godric, and one beside, whose name she never uttered.

“Let England stand secure, Oh, God; defend her from shame of conquest and Norman thrall; Oh God, let our England stand! Spare Thou my brother in the conflict and temper Thou his fierce soul. And now I pray Thee for—him, Oh God, for him that is our enemy, yet him I needs must love. Oh, be Thou merciful to him . . . let him not die.”

Now, as she prayed thus passionately, rose a sudden wild uproar, the clamour of many voices, a rushing of feet that, coming rapidly nearer, filled this holy place with unseemly riot, fearful cries of men, the shrieks and wailing of women and children:

“Death! Death! The Normans!”

The Lady Githa rose up, tall, very pale yet very stately, and turned to meet these poor fugitives who fled hither for sanctuary from the terrors without; and many among them knew and hailed her piteously:

“ ’Tis the Lady of Brandon! Oh lady, save us! There is death in the city! Fire——”

Now amid this rabblement she espied a squat, red-headed fellow, one of her own serfs, and him she beckoned with slender, imperious hand:

“What, then, Cnut?” she demanded clear and loud despite quivering lips. “What’s here? Speak!”

“The Normans!” he cried. “The Normans be on us, Lady. . . . They kill and burn! There be villages aflame beyond bridge. Dead folk i’ the streets! Women—ay, and children! Hell’s loose!”

“Ay, ’tis the end of the world!” cried another voice. “ ’Tis death——”

A sudden shrill and dreadful screaming, a trampling of armed feet, a glitter of steel; the whimpering fugitives were hurled aside, and soldiers appeared, grim, mail-clad figures dusty with travel and fouled with recent slaughter, at sight of whom the Lady Githa shrank appalled, until being beneath the great Rood she paused there, pale, trembling, yet resolute. But now, at the sight of her rich attire and proud young beauty, there was a roar of hoarse cupidity. Brutal hands clutched her, evil faces leered upon her trembling loveliness, but even as her captors plucked at and strove with her, down upon them whanged the flat of a sword, and a shrill though commanding voice cried:

“Off, dogs—off! Here’s meat for your betters!”

At the well-known voice the men leapt aside, and Githa beheld one whose thin lips curled in a slow smile as his narrow eyes drank in the lure of her revealing dishevelment.

“Aha! Dian!” he murmured. “Venus herself! As goddess I’ll worship thee, and woman o’ my delight. So—come to thy master!” And, thus murmuring, he seized her, swift and sudden, in clutch so shaming her womanhood that, forgetting pride, she screamed and, in her extremity, cried the name she had not spoken in her prayers:

“Gilles de Broc! Oh Gilles!”

And as if in answer to her prayer, there was the furious ring of horse-hoofs, the throng of fugitives and gaping soldiery was burst asunder, and into that holy sanctuary galloped a mailed knight, a slender man, hawk-faced, dark-eyed, fierce and quick with hot youth.

“Ha, Fitzurse!” he cried. “Thrice damned, accursed Fulk!” Even as he spoke, out flashed his sword and he was afoot. And there, before the shrine of Saxon kingly saint, the Norman long-swords flashed and smote and thrust, while Githa, gasping prayers, sank to her knees.

So mailed feet stamped and steel rang, till there came a shrill cry; and then Githa felt a powerful arm about her, and in her ears was a breathless, dearly-remembered voice:

“Lady Githa! Oh lady beloved! None shall harm thee . . . nought touch thee . . . fear no more. Thine am I to thy dear service. Thy will shall be my will ever. Come now. Come you home!”

So saying he raised her with a reverent gentleness, and, setting her upon his tall steed, went beside her through the silenced company, forth into the sunset.

“Ah, Messire Gilles,” she sighed, “surely the merciful God sent thee!”

“Ay, truly!” he answered, glancing up to meet the tender gratitude of her long, blue eyes. “Though indeed at such dread time I deemed thou wouldst seek sanctuary.”

“And . . . Harold the King——?”

“Alas, noble Godwinson lieth dead. Yet a right kingly dying.”

“Then woe to my loved England! Now are we Saxons thrall to the Norman.”

“Yet, lady . . . ah, Githa, yet is one Norman thrall to thee—here to-day in England as he was a year agone in Normandy.”

“And . . . Godric, my brother, know you if he live?”

“Ay, truly, though sore stricken. He waits you now safe in Brandon Holm.”

Thus he led her to where certain of his following waited, and with men-at-arms before them and behind he brought her safe through the turbulence and terror of London town.

Thus came they betimes to Brandon Holm, that goodly manor, above which now fluttered the blue saltire of de Broc, beholding which Githa sighed, though very gently.

“So now is Brandon and all else thine by right of conquest.”

“Yet will I hold it but for thee, my Lady Githa. ’Twas for this I sued it of Duke William.”

“Thou art then my master, Messire Gilles, by right of sword,” she murmured, sighing again.

“Yea,” he answered, sighing also, “yet master only to thy surer defence.”

Side by side they rode across wide garth where, instead of yellow-haired churl and serf, were dark-eyed esquires and men-at-arms. Nevertheless, both within and without the great house, all was quiet and orderly.

“Thou art truly a gentle conqueror, Messire Gilles!” said she, her sweet voice shaken by the very fervour of her gratitude; and because of this and the light within her eyes his cheek flushed and his sinewy hand fumbled with the bridle-rein.

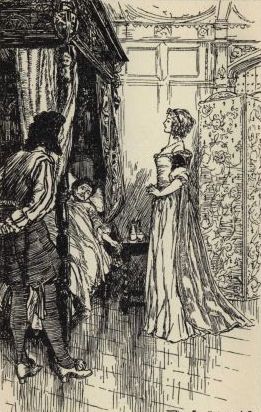

Dismounting at the wide doorway, he lifted her to earth and led her within the great solar where stood her bower-women to welcome her. Pale-cheeked were they and wide of eye, yet all unharmed. So, having kissed them, as was her wont, she dismissed them with words of gentle comfort.

And now, being alone with Sir Gilles, she made him gracious reverence, saying:

“Welcome to thy manor of Brandon Holm, my lord.”

Now at this he glanced from her to tapestried wall, to mighty roof-beams, to herb-strewn floor and, fidgeting with belt and sword-hilt, answered her a little wildly:

“Nay . . . nay, verily, by God’s light, I—Ah, Githa, in Normandy a year agone I loved thee yet dared not to speak my love, for thou wert so proud and high, with mighty lords to woo thee. And now . . . to-day I . . . I cannot, for thou art—I——” He heard her laugh and, thinking she mocked, turned away; but then he heard her sob, beheld her eyes bright with tears and, being young, stood amazed.

“Sir Gilles,” said she, “oh messire, to-day by cruel battle all that was mine is thine—yea, all save the very heart of me, for that . . . ah, Gilles, that was thine a year agone in Normandy.”

Then she was upon his breast, and if his mailed arms hurt her a little, she but loved him the more.

“And now, loved lord,” sighed she, striving in his embrace, “let us to Godric with this our new, great happiness. Come, mayhap joy so marvellous as ours shall lessen his grief and win him to quick health. Pray God it may be so!”

But when together they stood beside young Jarl Godric’s bed he looked from one to the other with great fierce eyes that burned in the pallor of his face, while from bloodless lips came the harsh whisper:

“Ha, is it so, proud sister? Thy body our victor’s spoil? Art then his booty . . . his serf, his leman thrall?”

“Not so, Godric, by God’s light!” cried Sir Gilles solemnly. “Githa shall ever be my loved and honoured wife!” But Godric closed his eyes and, scowling, turned him to the wall.

Next morning, when they came to tend the sick man, his bed was empty; Godric, the unconquered Saxon thegn, with his wounds, his fierce heart and implacable soul, was gone.

And some while after, within the stately Minster of Thorney and beneath the keen eyes of William the new-crowned King of England, Sir Gilles de Broc and the Lady Githa were wed.

And so, upon the wide demesnes of Brandon, at least, peace rested and a great happiness.

Years came and went, and beneath King William’s heavy foot the soul of Saxon England writhed, defiant still, and still unconquered. Mighty castles, mightily built, scowled upon rebellion; yet the doughty Hereward and his valiant comrades maintained awhile desperate war in and around the swamps of Ely.

Nevertheless, with William’s iron rule came laws, evil and good; out of chaos grew order; in town and city was peace, and with peace a growing plenty. The fires of many insurrections were quenched in blood, and in blood died brave Hereward at last, and, his heroic followers slain and scattered, King William and his hard-fighting barons took breath awhile.

Only in the wild wood Saxon steel yet flickered, Saxon bows still twanged, where roamed and fought wild companies of broken, landless men outlawed from hearth and home, to be chased and killed like wild beasts—wolves-heads all. And no man of all these desperate outlaws so powerful, so fierce and merciless as him they called “The Boar.”

Now upon a fair June morning when birds carolled and wild flowers bloomed, Gilles de Broc, Earl Marshal of South Sex and lord of Brandon Keep, set forth with a small though veteran company of knights, esquires, and men-at-arms.

Beside the famous earl, on a goodly palfrey, rode his little son, bright-eyed and eager in his small helm and ring mail and very full of breathless question, for this was the first time he had travelled so far.

By the great forest road they went, at easy pace, intending that night to bide at Brockenhurst. Few travellers they met, for the times were still somewhat troublous, and within the forest nothing stirred save sullen charcoal-burners or the flitting antlers of timid deer.

It was afternoon when they came where the road led up between steepy banks crowned with brush. Of a sudden, out from these boskages to right and left, arrows whirred; horses, deep-smitten, reared and fell, men gasped and died, and all was wild confusion. Then forth of the green sprang men, wild and terrible, to slay and plunder; and Earl Gilles, pinned beneath his dead horse, opened swooning eyes to see his small son beside him, blue eyes wide in little, pale face, but sword grasped in resolute hand.

“My lord,” he cried, “oh, father, art hurt?”

“Nay, son, ’tis but my foot. Yet I cannot budge, so get thee down, boy! Down, I say, behind yon bush!”

“But, messire, dear, my father, I have a sword to fend thee——”

“Down, I say! For now must——” A horn shrilled from the bank above and, glancing up, they beheld a very tall, grim man in rusty mail who, pointing down at them with his sword, beckoned to divers of his wild fellows.

“Bring these to me!” he commanded, and vanished amid the thickets.

So, having disarmed and freed the Earl from his dead steed, they pinioned him with thongs and his little son also, who, seeing his proud father murmured not, himself endured as silently, though his blue eyes yearned after his little new sword.

By devious ways amid dense, tangled underwoods and beneath mighty forest trees, the prisoners were marched until, deep amid the wild, they reached a small clearing where burned a fire beside which sat the tall, grim man, bugle-horn about his neck, long-sword across mailed thighs.

“So, Norman thieves,” quoth he, scowling at them beneath battered helmet, “slayers of Saxon women, murderers of Saxon children, Saxon am I and men do call me ‘The Boar.’ Well, boars have tusks to rend withal,—so will I rend ye twain—Norman wolf and cub! And first the cub, for short rede is good rede! Bring hither the cub, Wulfstan!” and slowly he drew his sword.

“Hold, sir Saxon!” said the Earl, his bold eye dauntless as ever, but brow haggard with sharp anxiety. “Rend me, an ye will, but this my son is young, a child innocent of war——”

“Good!” cried the outlaw. “Thus shall he die ere he learn. Bring me the Norman cub, Wulfstan!”

So they urged forward the little captive, who, looking into those merciless eyes, beholding the bright, sharp sword, quailed somewhat and bowed his head; but, seeing thus his own knightly mail, so bright and very new, he stood suddenly upright and stared into the fierce visage so near his own, flinching no more—only he breathed short and quick.

But now the Earl, shivering in his bonds, his lean hawk-face wet and agonized, spake in a voice that cracked strangely:

“Sir Outlaw, take my life, here and now, but set my son to ransom. Give him safe return to my castle of Brandon, and thy guerdon shall——”

“Ha—Brandon? Thy castle of Brandon? Then who art thou, Norman?”

“I am Gilles de Broc, Earl of Brandon, and——”

“Aha,—and this—this thy son will be son also of——?”

“Githa, my loved Countess.”

Slowly, slowly the outlaw reached forth his great hands. He drew the child nearer, staring upon him in strange fashion; then lifting off the small helmet, he pushed back the close-fitting camail, discovering a silky shock of curling yellow hair.

“Boy,” said he, sharply, “how art named?”

“Godric, messire.”

Bowing grim head upon clenched fist, the outlaw stared at the fire awhile, then:

“Why art so named, boy?” he questioned, his face still averted.

“Sir Outlaw,” answered young Godric, staring fearfully on that sharp sword, yet speaking boldly as he might, “it was in memory of mine Uncle Godric that was a valiant and noble Saxon.”

Then this outlaw, whom men called “The Boar,” rose up, his harsh face marvellously transfigured, his sword falling to lie all unheeded, and, looking at the Earl, above that small golden head, he spake in a voice as changed as his look:

“Ha, Gilles—Gilles de Broc, though Norman thou art, this thy son is true and proper Saxon. These bold blue eyes, that quail not at death, this yellow poll,—ha, by Holy Rood, thy boy is Saxon as I or . . . my sister Githa!”

The proud Earl uttered a choking cry; his eyes swam, though his voice was glad and joyous:

“Godric!” he cried. “Is it forsooth thou? Oh, brother, here is not death then . . .?”

“The lad is Saxon!” quoth Godric. “And Saxon slays not Saxon. But thou art Norman . . . yet lord to Saxon lady, and so——” He motioned to his wild men, and the Earl was freed of his bonds by quick and eager hands.

“Godric,” said Gilles the Earl, reaching forth his hand, “there is a place of honour for thee in Brandon that hath waited thee these many years, with loving welcome from thy noble sister! And in this England of ours a man’s work for thee to do. How say’st thou,—brother?”

“That I am outlaw with these my fellows—outlaws each and every.”

“There shall be pardon for them!” cried the Earl, looking round upon the wild company. “Pardon full and free to one and all—pardon and bounty! And this swear I upon my knightly word, for King William, though Norman and mayhap something harsh, is a just man. So Godric, my brother, come thou back to hearth and home; our England needs the like of thee.”

“Boy,” said big Godric, setting a large finger beneath little Godric’s chin that he might look down into those steadfast blue eyes, “thou small Saxon,—little kinsman and namesake, how sayst thou?”

“Come, messire, for I’ve ever lacked of uncles,” said the boy eagerly. “And now, Sir Uncle, an it please thee, I’ll have my sword again.”

Then Godric the Outlaw laughed and, catching the son within mighty arms, gave the father his hand.

“So be it!” he cried, fronting his eager followers. “Inlaws all are we henceforth! And yet, Gilles,” said he as their hands clasped and wrung each other, “and yet—thou art a Norman!”

“Ay, brother,” quoth the Earl, “Norman am I; yet there shall come a day, mayhap, in this fair England when there shall be neither Saxon nor Norman but a people greater, mightier,—who knows?”

“Ay, who knows?” said Godric, laying a gentle hand upon small Godric’s golden crown. “And yet, my brother, ’spite all thy Norman blood,—here stands a Saxon!”

“Wiglaf’s mighty hand plucked him back”

From time immemorial our old River has run upon its course, singing among sedge and bending willow, lapping against bank and wall and pier, laughing and chuckling to itself in sunshine and shadow,—but singing ever its song of sighful death and life’s joyous renewal, since ever Life was.

Small and insignificant beside other rivers of this planet, our Thames is yet greater than them all in experience of life and death. A silent road of age-old traffic, a crystal highway of pleasure, a defence against foes, it has helped the growth of mighty city and mightier empire.

Old Thames has watched the British village of Ligun Don or Lynne Dun wax to the proud walled city of Rome’s Londinium Augusta; it has echoed the rhythmic clash of Cæsar’s iron legions, the battle-roar of sturdy Norseman, Saxon, and fierce Dane; flood and fire and death in all shapes it has known while empires crashed to ruin, dynasties rose and fell, and the wondrous city grew and grew—mighty beyond the dreams of its long-forgotten founders.

Now where lives the Englishman, more especially the Londoner, who loves not his old River, the whole two hundred and twelve odd miles of it? For in it and on it and round about it his sturdy forefathers lived and loved, fought, suffered, and died; deep, deep within its silent bosom and in its banks to right and left lie their hallowed bones. Thus, in some sort, old Father Thames is indeed part of us, close linked and knit to our very destiny.

From its rise beyond Cheltenham to its wide outflow it is in itself a symbol of human life; pure at its source as the very Spirit of God, it laughs upon its young way between flowery banks, it grows sombre in the shade of village and town, becomes dark and foul in the great city’s mighty shadow, but, flowing on darker, sadder, leaps at last to lose itself in the sweet, clean immensity of ocean. . . .

“And so is it, Gregory,” quoth young Miles, gazing dreamful upon the murmurous water at his feet, “so is it I do love our Thames, for verily I do feel as I had known it in other days, dim days, Greg, ere London’s Tower was, or London so great.”

“Why, small wonder thou shouldst love it, lad, for, sithee now, ’twas yonder atwixt them two trees,” answered old Gregory Hooe, the river-man, pointing with a hand gnarled and sinewy from the oar, “ay, atwixt them two trees as the old River brought ’ee to me, of a buxom summer’s eve, three-an’-twenty year agone, thanks to the good Saint Cuthbert; for a rare blessing hast been to me, Miles, lad.”

“On a summer’s eve the like o’ this?” enquired Miles, leaning his lithe, tall shapeliness upon the long oar he held.

“Ay, lad. ’Twas the old River gave ’ee to me, the saints bless it! Floated ’ee to me in small wicker ark; and a bonny atomy ye were, all lapped i’ fine linen and the jewel slung about the little neck o’ thee!”

“This,” murmured Miles, drawing from the breast of his leathern jerkin a gold medallion set with onyx stone curiously enwrought.

“Ay, lad,—the Pelican in Piety, crowned. The which be a strange symbol and rare, as do make me guess thou wast begot o’ noble blood. Belike some potent lord, a duke mayhap, went to the fathering o’ thee, Miles, or even . . .”

Miles laughed and, thrusting the medallion from sight, clapped a large hand gently upon the old man’s sturdy shoulder.

“Sire me not so, Gregory. Thyself hast fathered me so kindly well, none other would I so love were he the King’s Majesty——”

“Hast said it, lad!” cried old Gregory. “As thou’rt taller and stronger than most men, so is our lord King Edward, our Longshanks. Ay, and thou hast the same small droop o’ the left eyebrow, even as he, the same proud cock o’ chin——”

“Nay, now,” quoth Miles, black brows a-twitch, yet closing the old man’s lips with gentle finger and thumb, “peace, father Greg. No lust have I to Royal bastardy, not I. Thou’rt my father, sir—a boatman I, and therewithal content.”

“God love thee, Miles, now!” said old Gregory, smiling up at his comely young giant. “Love and father thee will I even as this goodly River hath fostered me. Ha, look, son, ’tis a noble stream, our Father Thames; ’tis bread to us, riches, our very life. And heartily do I love it since it gave me thee. So is it twice thy father, ay, and mother too, since verily it bore thee, three-and-twenty year agone. Wherefore God bless our Father Thames again, say I.”

“Amen!” quoth Miles, and, doffing his leather cap, bowed his comely head in smiling reverence to the murmurous, sun-kissed River.

“And now, Father Greg, yonder come Tom and Dickon with their lads to the evening ferogage. So, by thy leave, I’ll up stream to a pool that holdeth noble trout; a crafty fellow hath thrice escaped me.”

“So—good sport, lad. But what o’ supper?”

“ ’Tis ’i the shallop here,” and he laid his hand on a small boat, a craft somewhat battered with long-usage but painted a soft and tender blue: now blue is the colour of happiness and good fortune.

With a heave of mighty shoulder he launched the shallop, leapt nimbly aboard, and waved a sun-browned hand; then, shipping oars, pulled away up stream.

And as he rowed with long, powerful strokes his dark dreamful eyes gazed where, vague with distance and pink with sunset, rose the massy walls and embattled turrets of London’s mighty Tower, and beyond this the lordly palaces, the spires and steeples of the famous city until a bend in the River hid them all.

And, after some while, he came where sighing willows leant to kiss the murmurous waters, and here he turned to make the shallop fast; but in this moment his keen eyes espied a shadow in the tide, and, knowing what this must be, with powerful thrust of oar he sent the light shallop leaping thitherward, and bending dexterously over heeling gunwale he grasped floating tresses . . . then his arm was fast about a woman’s body, and winning ashore he laid her gently upon the grass.

An oval face, death pale, ’mid clinging braids of bronze-gold hair, a noble shape, yet all tender, youthful, rounded loveliness. Miles looked and looked and caught his breath for very wonder of her strange loveliness, while with reverent hands he ordered her draperies and, with water-wise skill, strove to woo her back to life.

Yet very still she lay and breathless all, as on the very brink of death; then, suddenly, even as he wrought despairing, her eyes opened on him, eyes that, meeting his, from look of dread grew wondrous tender and radiant with quick gladness. The shapely mouth curved in smile of joyous welcome, and from these pale and quivering lips came a voice sweetly low yet clear:

“Oh Metellus! Loved Julius! Forth of the shadows back to thee come I, since Love is mightier than Death! . . . Oh beloved Julius!” Then a hand was upon his brow, a hand slim and wet and cold. . . . And now, looking into these eyes of dark bewitchment, Miles himself grew sudden cold as death . . . grew warm again with eager life, yet full of great awe; then, trembling with a joy such as he had never known, he clasped her fast in sudden yearning arms.

“Fraya!” he whispered, “Oh Fraya, beloved! Now be glory to all the Gods!” But when he would have kissed her she stirred in his embrace and, uttering a small moan, looked up at him in cold amaze and spake, shivering and petulant:

“Oh alas! These cruel waters will not drown me! I am not dead, then?”

His powerful arms grew lax and, laying her upon the sward, he shivered violently, looked wildly up and around and clasped his head in shaking hands; then quoth he:

“Ah, woman . . . maiden . . . but now thou didst speak me strange words in another voice . . . thou didst look at me with other eyes——”

“Nay,” said she, knitting black and prideful brows at him, “I spake not thee!”

“Then here was some enchantment!” whispered Miles, and crossed himself devoutly.

“Oh and alas!” she wailed, “and the River would not drown me.”

“Nay, God and His saints forfend!” said Miles, shaking his head in deep perplexity. “Kind Father Thames shall ne’er slay such loveliness, I ween.”

“Think ye so?” sighed she. “Then cast me in again to prove thy words; for Father Thames shall kill me an we do but give him time. Then shall I be quit of fear and grateful therefore. So, messire, toss me in again, I do command thee—forthright!” Miles stared, then smiled and shook his head; whereat she frowned again with look high and arrogant, albeit she shivered somewhat:

“How?” she demanded, with the prideful arrogance of lofty birth. “Wilt defy me?”

“Even so!” he answered, and reaching a large boat-cloak from his shallop wrapped it close about her despite feeble resistance.

“Ha . . . messire,” she gasped. “Thou’rt presumptuous!”

“Yet no knight, lady!”

“Then who’rt thou to meddle—that darest give me life when I . . . do yearn for death? Who’rt thou to order my fate thus?”

“A water-man, lady, a man o’ the River.”

“Bold knave, so is thy presumption the greater!”

“Ay, so,” nodded Miles; “but now thy so white teeth do begin a-chattering, thy tender body to quake and shiver. Wherefore incontinent I’ll bear thee to thy home——”

“Never, thou river-man; here will I hide and shiver me to death——”

“Then will I carry thee to my good father.”

“Then will I cast me again i’ the cold Thames!” quoth she, proudly resolute, despite chattering teeth and shaking limbs; wherefore Miles took himself by his smooth-shaven chin, viewing her defiant loveliness as one at loss. Then, stooping, he gathered her in his arms and strode in among the trees and underwoods that grew very thickly thereabouts.

“Ah, th-thou . . . w-water-man,” she demanded, chattering, yet looking up at him with eyes no whit afraid, “th-thou large m-man o’ the R-river, what wilt d-do now to m-me?”

“Comfort thee!” he answered; and so after some while brought her where, deep hid in mazy boskages, was a little cave that opened in a grassy, bush-girt steep within a leafy dell aglow with sunset.

Here, setting her down, he gathered sticks, dried leaf and fern, struck flint and steel and set a fire going that soon leapt and crackled so merrily that she smiled and reached slim shaking hands to its genial warmth.

“River-man, how art named?” she questioned suddenly.

“Miles, lady.”

“Why, ’tis an apt name, for thou’rt mighty and long!” said she, and sat warming herself and looking up at him with a certain arrogant serenity so that his cheek flushed and he stooped to tend the fire.

“Soon,” said he, very conscious of her half-disdainful scrutiny, “soon this small cave shall be warm and thou quite dry. In the meanwhile, if ye be an-hungered, lady——”

“Nay,” said she, recoiling. “Food for me hath lost all savour; cates the most delectable I do abhor! Oh, methinks I shall eat never again!”

“Then, by fair leave, I will, lady, for I have not supped!” And away he strode, but very quickly was back again, a goodly bundle under his arm.

“What hast thou there, Master Miles?” she questioned, something plaintively.

“Cold neat’s tongue, lady, with cheese, a crusty loaf, and ale,” he answered cheerily, setting forth these viands on the grass between them.

“Hast e’er a sup of wine for a poor clammed soul?”

“Alas, no, lady! Here in leather pottle is but ale.”

“Ale?” quoth she, shuddering; “ ’tis rank drink, fit only for poor lusty knaves.”

“And water-men, lady.”

“So will I adventure me to taste o’ thine ale, Master Miles.”

“Nay—out on’t; here is no cup, lady!”

“Then needs must thou learn me to drink from thy pottle!” she sighed. So, coming beside her on his knees, he steadied the leathern jack while she assuaged her thirst.

“Oh, ’tis a harsh and mannish drink!” said she, making a wry face. “Now eat, Sir River-man Miles, eat and heed not me!” and, bowing her lovely head, she gazed upon the jovial fire, shuddering cosily to its voluptuous warmth.

Now after Miles had eaten awhile he spake, keeping his gaze also upon the crackling fire:

“Thou art, I guess, a noble lady of lofty rank and proud degree.”

“I am merest woeful poor maid and desolate.”

“Poor maid, and why would ye die?”

“Die?” she murmured, glancing askance at the goodly viands on the grass beside her.

“Wherefore would ye drown?”

“Drown?” she repeated, her blue eyes still intent. “Drown. Ay me . . . yea, forsooth, ’twere better to drown than wed him I do hate. Better lie dead than in his loathed arms!”

“Verily! Yet why wed one ye hate?”

“Because ’tis I am commanded thereto by—ah, ’tis the will of—my most harsh warden.”

“Nay, but ye are of proud, courageous seeming. Defy him.”

“Alack, he is such as none may e’er defy!”

“Then wherefore not fly his cruel governance and go free?”

“Free?” she cried, tossing shapely arms in a wild yearning gesture. “Oh, sweet heaven, that I might in very truth! Freedom have I never known, nor ever may—except, mayhap, in death!”

“Thou poor, sweet soul!” murmured Miles, and she, reading in his honest eyes the frank sincerity of his pity, bowed her stately head with a small sob. Then she said:

“So it was I sought to die. Yet am I nothing brave, for whiles I stood, shill-I, shall-I, upon the River’s marge, my foot slipped, and in soused I. And being i’ the water and it so cold I yearned to live, and swam amain until my robes dragged me down. And then as kindly Death came on me and I no more afeard, e’en then thy rude hand plucked me back to life and—dread o’ the to-morrow.”

“So now,” quoth Miles, “now would I pluck thee from all fear and every sorrow an I might!” After this there was silence some while, she looking, wistful, on the fire again and he on her until at last she, sighing, spake:

“Sigh not for me, thou Miles o’ the River. Eat, Sir Water-man, eat, nor grieve for poor woeful me.”

“Nay,” he answered, “mine hunger is of a sudden strangely fled.”

“Why, then,” said she, in soft, small voice, “wilt spare me one little bite?” Up started Miles and, upon a manchet of white bread, proffered her a slice of the neat’s tongue; the which she, plaintive sighing, took and ate with small, nibbling bites yet lusty appetite.

“Eat thou also!” she commanded. And so, sitting friendly side by side, they shared the supper between them whiles evening crept down, a tender, fragrant, star-gemmed dusk with promise of a radiant moon.

“And,” sighed Miles, their supper ended, “must thou soon to wedlock indeed? With one thou hatest?”

“Indeed! Alas!” sighed she.

“Now this,” said he, frowning, “this, methinks, shall work thee shame—ay, and misery abiding!”

“This,” she murmured, looking on him sadly, “this is wherefore I sought to die.”

“But why not seek life, and perchance . . . happiness?”

“As how, good friend?” she questioned eagerly, leaning towards him. “Oh, prithee teach me!”

“Dost love . . . no man?”

“No man in all the world.”

“Why, then,” said Miles, staring hard at the fire, “if thou’rt truly in plight so woeful, wed a man thou dost neither hate nor . . . love . . . as yet.”

“What manner o’ man?” she questioned softly.

“A man o’ Thames—e’en I, lady.”

“But thou—thou lovest me not.”

“Hum!” quoth Miles.

“Nor I thee.”

“ ’Tis not expected . . . yet mayhap ’twould come—in time . . . who knoweth?”

“Ay, who knoweth!” she sighed, viewing the noble shape of him, dreamy eyed. “Ay, forsooth it might,” she nodded, “an thou couldst first learn to love me——”

“This I promise!” said Miles fervently.

“An wouldst be patient and tender as thou’rt strong?”

“This also I vow thee.”

“Then might I wed thee, Miles. And yet, alack, ’twere but a vain and idle dream! Thy wife or no, hide where we would, they’d snatch me from thy very arms——”

“Ha, not so, by God!” cried Miles, dark head up-flung, dark eyes fierce and bright ’neath scowling brows. “None should touch thee whiles I lived!”

“So should I be thy death!” she mourned.

“So would I die right cheerily in such just cause. Moreover, ay, by Holy Cross, I should not die alone!” Now as he scowled thus, face grim in the fire-glow, mighty fist aloft, she of a sudden rose to her knees, staring on him with a look of fearful wonderment.

“Miles!” she gasped, “Oh Miles . . .!”

“How; what is’t?”

“Now,” cried she, leaning near, “in thy face, thy mien, the very shape of thee, thou’rt like to him I most do fear! Ah, surely thou art nobly born?”

“In sooth,” he nodded, smiling, “borne was I of yon noble Thames and——”

“Hail, son of Thames and fair greeting!” said a deep rich voice. “Ye twain that were, and are, and shall be—greeting!” Into the fire-glow stepped a man; tall was he and very old, for his long hair and beard gleamed silvery white, yet the eye beneath drawn hood seemed bright with fiery youth. Thus stood he, looking down on them with aspect so stately and commanding, though kindly withal, that Miles stood up, cap in hand:

“Sir Ancient,” said he, “who art thou and what wouldst thou here?”

“Leolyn the Harper, I, tall youth, that some do name John the Rhymer, for, like the ancient River yonder, I sing to such as have ears to hear withal.”

“Ay, surely I’ve heard thee,” said the lady, dark brows knit haughtily, proud head aloft. “But now no mind have I to——”

“Truly thou hast heard me sing, lady, but with ears fast shut up like thy proud heart. Yet this night, peradventure, thou shalt hear and know the great truth whereof yon River singeth, my lady Duchess.”

“How—Duchess?” cried Miles in a voice like one sore smitten.

“Indeed, good youth, the Duchess Heloise she—late betrothed to Hugo, lord of Brandon Tower. Ay, yonder sitteth this most high, right noble lady, Duchess of Rouvère, Countess of Framlinghame, Lady of Remy Beckton, and divers many other towers, manors, and demesnes both here and beyond sea—herself, though sounding so many, yet one and indivisible—and moreover ward unto our potent liege lord King Edward the First, whom God preserve!”

“The King’s ward!” gasped Miles.

“Yea—yea!” cried Heloise passionately. “All this am I, and all this would I flee, e’en were it to a fisherman’s mean hut or . . . a River-man’s strong arms!”

“Ah, lady, lady!” stammered Miles, shaking his despondent head. “Here in troth . . . here were bitter folly!”

“Oh,—thou!” cried Heloise, turning fiercely upon the Harper. “Out on thee for knavish, idle chatterbox! Alas, alas, Miles, a prisoner I, throned solitary upon Pomp’s dismal, very peak, a fettered victim to a mighty King’s vile polity, to be given into whatsoe’er man’s arms he will! Ah, Death were sweeter! . . . Oh Miles! . . . Ah, thou meddling Rhymer, I would have told him—after!” Now looking into the yearning passion of her eyes, beholding the surge and tumult of her bosom and all her eager, vital youth, Leolyn smiled and from his cloak took a small harp:

“Proud lady,” said he gently, “most sweet maiden, methinks great Love with tender wing hath touched thy cold heart, so are thine ears open at last. List now and I will sing ye the song old Thames hath sung since ever he ran, which is a song of the three Great Mysteries that are yet matters very simple to such as have ears. Hearken now, sweet children both, and be ye comforted and bold for Life and Love.”

Then Leolyn, standing over against them beyond the fire, unslung his harp, struck divers running chords, and sang in a voice soft and deep and wonder-sweet:

“Pomp and rank, estate and power,

These may pass within the hour,

Fade and languish as a flower

And wither in a day.

But Life and Love and Time, these be

Eternal all—the Deathless Three,

The veritable Trinity,

These ne’er shall pass away.

What though this fleshly body die?

The deathless Soul shall upward fly

Back—where the Fount of Life doth lie

Lost in immensity.

Thus if cold Death a while benight us,

True Love shall like good angel light us

Back into Life—and reunite us

Through all eternity.

For Life, like mighty river flowing,

Ever coming, ever going,

Like God and Time is past our knowing—

The great and Deathless Three.”

Now while they yet sat thralled by such sweet singing, Leolyn drew from his scrip a handful of dried herbs and cast them upon the fire:

“Behold!” said he. “Look, children, and know!”

Even as he spoke, up rose a column of vapour that rolled about them, thick and dense and of a marvellous sweet savour,—a smoke that wreathed awhile and thinned away.

Then of a sudden the Duchess Heloise uttered a sweet, glad cry and reached forth eager arms to him that gazed on her with eyes of adoration, a slim man of a noble bearing, sheathed in the glittering battle harness of Imperial Rome.

“Metellus! Oh Julius!” she cried.

“Fraya . . . beloved . . . at last!” he answered; and so they kissed; but lo—the arms about her now were dight in ringed mail, a young hawk-face smiled down on her ’neath gleaming helmet:

“Gilles!” she murmured. “Dear my lord!”

“Githa!” said he. “Sweet my wife!” and kissed her; and then again was wondrous change: a great fellow in triple chain mail, a tender-smiling, mighty man with ruddy hair:

“Oh Gyles!” she whispered.

“My loved Melissa!” he smiled, kissing her; and so again was transformation. . . .

“Ah, . . . thou!” she sighed. “My man o’ the dear River! Take me . . . hold me, Miles!”

“God knoweth that will I!” quoth Miles, and caught her fast and kissed her amain until at last she chid him, saying:

“Nay, now, mine Heart,—no more, with yon Rhymer to see us!” So, unwilling, Miles released her, and then she clung to him again with a despairing cry, for behold, Leolyn the Rhymer was gone, but there, his mail gleaming in the firelight, his fierce eyes brighter yet, stood Hugo, lord of Brandon Tower, and divers of his foresters behind.

But now the young Duchess turned and fronted this fierce lord, with head erect and eyes unquailing, like the great lady she was.

“Well, messire?” she demanded haughtily. “What meaneth this so mannerless intrusion?”

Lord Hugo fell back a step:

“How?” he gasped. “How then, lady—thou that art accounted so cold . . . so disdainful of wedlock with thy peer canst yet prove overly kind to yon base fellow? Ha—now black shame on thee!”