* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Rogues and Adventuresses

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Charles Kingston

Date first posted: Nov. 12, 2016

Date last updated: Nov. 12, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20161111

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

ROGUES AND ADVENTURESSES

| BY THE SAME AUTHOR |

| Remarkable Rogues |

| The Romance of Monte Carlo |

| The Marriage Market |

| The Judges and the Judged |

| THE BODLEY HEAD |

ELISABETH HOWARD, COMTESSE DE BEAUREGARD

(The Historic Barmaid)

ROGUES

AND

ADVENTURESSES

BY

CHARLES KINGSTON

LONDON: JOHN LANE BODLEY HEAD LIMITED.

First published in 1928.

Printed in Great Britain at the Athenæum Printing Works, Redhill.

| chapter | page | |

| I. | Lacenaire—Poet and Murderer | 1 |

| II. | Cora Pearl | 25 |

| III. | The Converted Murderer | 42 |

| IV. | The Historic Barmaid | 70 |

| V. | Priest and Murderer | 86 |

| VI. | Sophie Dawes | 110 |

| VII. | The Cultured Criminal | 128 |

| VIII. | Dr. Webster of Boston | 154 |

| IX. | A Collector of Husbands | 178 |

| X. | Inspector Montgomery’s Crime | 194 |

| XI. | Grace Dalrymple Elliott | 217 |

Rogues and Adventuresses

If Infamy has its immortals the name of Lacenaire can never die, and, as the most remarkable if not the greatest of French criminals was made the subject of a character study by Victor Hugo in “Les Miserables,” he must share in the immortality of the immortal Frenchman. Yet it is not easy to see why this scoundrel should have attracted the attention he did, or why for a period all France should have regarded him as of far greater importance than a revolution. But Lacenaire succeeded in hypnotizing his country and he achieved this by the pose of philosopher in the condemned cell. Inspired by a vanity which had been his special vice from childhood, he laughed in the face of death because he was philosopher enough to realize that it is always better to laugh than to cry, and by thus making a virtue of necessity he became a personality as he strutted towards the guillotine, inspired and encouraged by the knowledge that the world was watching him. He had at last captured the popular imagination, having, like so many other poets, obtained a reputation on hearsay—for editors had declined his contributions because his very inferior productions had yet to be rendered marketable by their author turning murderer. When he did, the news that there was a professional criminal who was an author, poet and philosopher, gave France a new thrill, even in an age when thrills were plentiful. The man in the café declared that Lacenaire was unique and that there never had been a criminal like him, and as there is no place in the world where sentiment is so cheap as in France, there were many who wished that the poet and philosopher could have been saved from the guillotine. But the bare truth is that Lacenaire was a criminal and little else. He was a common thief, a clumsy forger and a cowardly and bloodthirsty murderer. He had not a spark of chivalry in his composition and his sense of honour was as deficient as his sense of humour. In fact, a born criminal, one foredoomed from his earliest years to a disgraceful life and an ignominious death.

It is not difficult to trace the growth of the criminal germ in Pierre François Gaillard, better known by the name of Lacenaire, which he conferred on himself. His father was a fairly prosperous iron merchant who resided near Lyons, and Lacenaire was sent to a good class school. The boy, shallow and a boaster, early evinced that effeminacy which is always accompanied by cunning, cowardice and craft. Unwilling to join in the usual sports of boyhood, he led a more or less isolated existence, suffering tortures at the hands of bullies until his nimble brain devised schemes for their discomfiture. Thus he acquired his first lessons in the art of meeting physical force with craft, and so the child grew to believe that nothing mattered except the end, and that the means, however dishonest, which achieved that end were fully justified. The brooding, moody child grew into a sly and effeminate young man, sufficiently educated to be able to deceive himself with cant phrases and a bogus philosophy. He would have preferred to live in vicious idleness, but his father’s affairs were not prospering, and Lacenaire was sent off to Paris to study for the law. His evil tendencies had already exhibited themselves, but his parents hoped that they were merely the passing indiscretions of youth, and with astonishing optimism they let loose in Paris this pale-faced, delicate-looking man with the deep, penetrating eyes and long, thin hands, which he had once referred to in a moment of philosophic candour as having been made for strangling.

In Paris Lacenaire was fortunate to make many acquaintances, who would have developed into powerful and loyal friends had his temperament permitted, but his vanity, spite and boastfulness alienated them, and when he ended a series of quarrels by shooting the nephew of Benjamin Constant in a duel, practically every door in Paris was closed against him. Those who were acquainted with the facts of the case never wavered in their belief that Lacenaire murdered his opponent, and the fact that the successful duellist never attempted to bring any of his calumniators into court was practically an admission of guilt.

However, the duel was to bring to fruition all those vicious and criminal imaginings which had been growing in the mind of Lacenaire since boyhood. Finding himself in the position of a pariah he determined to make war on the society which thus openly despised him, but the eagerness with which he turned professional criminal was an indication that sooner or later he would have taken to crime for a living.

Shortly after the unfortunate duel his father failed, and Lacenaire, deprived of an allowance, at once sank into a lower stratum of society than his ostracism by his former friends entailed. At one step he became a member of a class which does not know the dividing line between poverty and crime, and it was not long before he attained a leading position in the underworld by reason of his debonair manners and swaggering air of superiority. Criminals who could scarcely read regarded with awe this good-looking young man who boasted of a luxurious childhood and affected a profound knowledge of literature and politics. Gossip reported that once he had been received at the houses of ministers and that he had been acquainted with royalty itself. Determined to make use of the boasting young fool, they flattered and toadied to him, and Lacenaire immediately took up the pose of philosopher and poet, and boasted of the wonderful powers he possessed and of the fortune he would lead them to if only they obeyed him.

However, it became absolutely necessary that Lacenaire should obtain some sort of regular employment, and as an ex-law student there was only one occupation open to him, that of lawyer’s clerk. The family influence was still strong enough to secure him a post, but Lacenaire was anxious that his fellow clerks and their friends should understand that he was no ordinary employé. To impress this upon them he gave a dinner at a café to celebrate what he called his entry into the ranks of the workers.

The guests were chiefly lawyers’ clerks, amongst them being a youngster of the name of Claude. He had never seen his host before, and, having been warned that he was about to be entertained by an aristocratic-looking man who was much too good for work of any sort, he was surprised to see at the head of the table an over-dressed person whose obvious effeminacy could not conceal the fact that his thin body possessed a supple strength which was in keeping with the vicious luminosity of dark, deep-set eyes.

The dinner was an uproarious success, and Lacenaire was gratified by the deference paid to him by those he patronizingly called his “colleagues.” In his concluding speech he thanked them with the air of an emperor, and he was really eloquent as he described how within a few hours he would lay aside the character of idler and dilettante and take his place amongst those who had to fight the battle of life in the ranks. They applauded that sentiment, for they had drunk his wine, and the man who pays for the dinner has no critics.

In the early hours of the morning the café disgorged a flushed and excited troop of young men, and it so befell that Claude, the youthful clerk, walked away arm in arm with the head clerk in the office where Lacenaire was due to begin work at nine o’clock.

“What do you think of him?” asked the older man, who had been fascinated by the silky personality of his latest clerk.

“He has the eyes of a wild beast,” was the unexpected answer, “and for all his gentleness and politeness I would not trust him anywhere.”

The critic’s words were drowned in a roar of derisive laughter, but they were recalled by the head clerk a few hours later, when on entering the office he found that the safe had been broken open and the contents stolen, while there was no sign of Lacenaire. That was no legal proof that the latter was the thief, but it required no great intelligence to connect him with the affair, for on the occasions of his visits when negotiating for employment he had done all in his power to ingratiate himself with the head clerk, who now recollected that the charming young man more than once brought the conversation round to the safe, and had led him into discussing how it was opened and what it usually contained.

Six months later Lacenaire was actually under arrest, but on another charge, for the criminal who later on boasted that he was a Napoleon of the underworld began with a mean and petty theft in a café. The fact, however, that he had been a law student and was well related was sufficient to lift the affair out of the commonplace, and his trial and conviction created something of a sensation in the comparatively limited circle in which he had been known, for a few years were to elapse before the thief turned murderer and achieved international infamy.

Other experiences of prison followed, and if Lacenaire was usually unsuccessful he was perfecting his pose of super-criminal so that when he launched out he might be able to give some distinction to the character. Vanity was his chief prop in times when failure proved that he was a conspirator of no originality or courage, and the adulation of the ignorant was the only comfort he had when striving to make the most of his little stock of knowledge.

A memorable incident now happened which was to have remarkable and sensational consequences.

He was in Poissy jail when he met a journalist, a political prisoner, and the result of the meeting was that Lacenaire wrote an article for the journalist’s paper on penal methods. It was a creditable production in the circumstances, but in no way remarkable, and only vanity could have discovered in it proof of that genius which henceforth Lacenaire claimed for himself. He talked of devoting himself to literature and started to write a play, but the time was approaching when the unsuccessful thief determined to try his hand at the most serious of all crimes. Literature was abandoned, and the criminal dilettante of the underworld resolved to make a bold bid for recognition as its king by putting his courage and his craft to a supreme test.

When, before his death, he was asked why he had not utilized for money-making purposes the literary gifts of which he boasted, he replied: “I had to choose between writing a play and murder, and I chose murder because it was easier.”

Had he been truthful, however, he would have admitted that even had he possessed the necessary talent he would have disdained honest work because his vanity had become so intense that he could not believe he could fail to outwit society.

Had Lacenaire’s intelligence or courage equalled his vanity he would not at this stage of his career have taken a partner, but in the case of a man who needed no incentive to self-flattery, blunders were bound to be frequent. It may have been that when he joined forces with Pierre Victor Avril he required a servant rather than an equal, but the underlying reason was that he had not the necessary physical or mental courage to commit murder alone. Avril, a companion picked up in jail, called himself a joiner, but having worked at that trade on occasions so rare the description was apt to bring a smile to the lips of anyone who heard it. However, he was a bloodthirsty ruffian, who, if only by means of contrast, flattered the senior member of the firm, who was now thirty-four, and in spite of all his vicissitudes was looking his best. One who met him at the time described him as possessing the lofty forehead of the thinker and features which were refined and compelling. Able to make the most of his small stock of learning, he could give a varnish to the most revolting of acts and inspire even in men like Avril a sort of vicious admiration.

Lacenaire’s imprisonment at Poissy, in 1829, appears to have influenced almost every act of his life up to the final catastrophe in January, 1836. We have seen that it was in Poissy he found his only employment as a journalist, and it was there he came upon his future partner. And where he found Avril he also found a victim, although it was not until 1834—five years later—that he recalled Chardon, the miser of infamous habits, who now lived in a garret in the Rue St. Martin with his mother, a helpless invalid. Chardon was a vile product of a festering city, despised even by the worst of criminals, one who went through life in a sort of slime, a typical inhabitant of the underworld of the underworld. With an insolent hypocrisy which was almost pathetic in its ineffectiveness he claimed membership of a religious brotherhood, but it was neither his vileness nor his hypocrisy that attracted Lacenaire’s attention. In the neighbourhood of the Rue St. Martin it was believed that Chardon had accumulated a fortune which he kept in specie in his garret, and it was that fortune that tempted Lacenaire. Of course, as a philosopher, he had to give his crime a higher motive than greed, and he, therefore, called it revenge for an insult alleged to have been received from Chardon at Poissy, but it was the prospect of laying his hands on gold that caused Lacenaire to take Avril to a café near the residence of the Chardons on the morning of February 14th, 1834, to discuss and plan a double murder.

Lacenaire despised Avril because he was one of the common people, but secretly he admired a man who had once very nearly killed a warder in a fit of temper. His own exploits had not hitherto risen higher than robbing a till, and thus he regarded Avril with a respect he would not reveal, because it was not part of the Lacenaire philosophy to show respect to anyone of inferior birth.

There is little doubt that Lacenaire would have preferred to work on his own, but he had not the courage to face even the debilitated and nervous Chardon, and it is significant that when the two men went from the wineshop to the house of the Chardons it was Avril who entered first on the invitation of Chardon.

“Come in, gentlemen, and sit down,” said the doomed wretch, who recognized two former friends in misfortune and therefore did not distrust them.

They were to be his last words in this world, for as he was bowing to them the philosopher and his hired assassin sprang upon him and while Avril’s fingers closed round his throat Lacenaire stabbed him again and again in the back until he sank without life to the floor. There Avril finished him off with a hatchet while his partner crept into the next room and murdered the helpless old woman.

Undeterred by the ghostly presence of the corpse, the two men searched for the many thousands of francs they believed to be concealed in the room, but all they secured for their trouble was five hundred francs and a statuette, which proved of no value.

The two murderers behaved with a coolness which seems to suggest that they felt that the murder of Chardon would be regarded by the public as an act of justice, and that in any event the police would not be in a hurry to avenge his death. Whatever the reason, however, they ran quite unnecessary risks, actually lunching together in a restaurant close by, although their clothes were bloodstained. But Lacenaire, at any rate, had enjoyed the thrill of his first big crime. He felt he was no longer a mere talker; at last he had done something in his own opinion to justify his continual boastings; and he had, in fact, achieved some of his perverted ambitions.

From the café they went to a Turkish bath and, having got rid of the blood-stains, separated, Lacenaire to spend the remainder of the day and most of the night reading Rousseau; Avril to spend his share of the profits in a carousal which lasted until dawn, although he and Lacenaire had already planned their second murder and had agreed to resume work the next day.

They were determined, however, that their next murder should be a much more profitable one, and as it was two days before the double crime in the Rue St. Martin was discovered, they were feeling particularly pleased with themselves and supremely confident when disguised as law students—Avril must have been a very comical travesty of one—they engaged a room in Rue Montorgueil. Lacenaire was now Mahossier, which name he chalked on the door of his new lodgings, but it was unnecessary to rechristen his partner, who was to remain in the background until some unfortunate bank-messenger with a large sum on him was lured into the room which, Lacenaire grimly remarked, would not take long to convert into a mortuary.

Avril was inclined to grumble at the small profits of the first murder, but Lacenaire, who was philosophical enough to accept the inevitable and who never wasted his regrets on what-might-have-beens, affected to be delighted.

“We have done something more than make money, my dear comrade,” he said. “We have achieved the perfect crime. Think of it! We walk into the house in daylight and kill two vermin and we walk out again and no one suspects us. That is an achievement, and if you were an artist you would be proud of it.”

The reasoning was too much for the turgid brain of the ex-joiner, whose dissatisfaction changed to dismay only when two days after the murders in the Rue St. Martin the Paris police discovered the bodies. Had it not been for the unnecessary assassination of the old woman the police might not have done more than make a perfunctory attempt to solve the mystery, but they were roused by the brutality of criminals who had suffocated the old lady, and Avril, an easy prey to terror, unable to discover in Rousseau an opiate for a guilty conscience, spent most of his hours in cafés and drank himself into a delirium of forgetfulness. Had he been able to keep his head all might have been well, but forgetting Lacenaire’s maxim that a murderer should not demean himself by indulging in petty crimes, he reverted to his usual profession of thieving, blundered, and was arrested.

When the news reached Lacenaire at 66 Rue Montorgueil, it drove him into a paroxysm of rage. But as Avril knew all his secrets and was almost indispensable to him he made an effort to rescue him from the police, failing because they would not allow the ex-convict out on such security as Lacenaire could offer. Thus it became necessary for the latter to find a fresh partner, and he began a tour of the cafés and wine-shops in search of one.

It was not an easy task. Paris was plentifully supplied with criminals of all sorts and conditions, but philosophers who are murderers are rare and Lacenaire was particular. He required an assistant whom he could dominate and influence, some one better than a mere brute who would be impervious to arguments however epigrammatic or poetical. He was not, of course, satisfied when after some disappointments he was obliged to accept the cooperation of a burly ex-soldier whose family name was François, but who was known in the circle he honoured with his presence as Red Whiskers. François’ position in the criminal underworld of Paris may be gauged by the fact that everybody knew his criminal tariff, which was brief enough to be memorized easily. For five francs he was willing to break into any house in France; for ten he would undertake a commission to disable anyone, and for twenty francs he guaranteed murder. In fact, a choice specimen of the primitive ruffian.

A favourite café of Lacenaire’s was the scene of the first meeting of the philosopher and the ex-soldier, and the partnership might have been sealed there and then by much red wine had it not been that François, unable to understand his new acquaintance’s flowery language, decided that he was either a lunatic or a police spy.

“I must have proof that you are straight,” he said, after listening to a philosophic oration on the grandeur of crime, not a word of which he had understood. “You can talk, my friend, but so can the police when they have a mind to.”

“You despise me because you think I am a mere amateur,” exclaimed Lacenaire resentfully, “but I have graduated in your university and taken higher honours than yourself, my good François. Have you heard of the murders in the Rue St. Martin? Well, I killed the Chardons.”

The disclosure removed the ex-soldier’s doubts, and there was admiration in his eyes as he held out the hand which grasped Lacenaire’s.

“I am with you,” he cried, and they drank to each other like comrades.

“Then come with me to 66 Rue Montorgueil,” said Lacenaire, who was always anxious to get to work when money was short. “I have arranged to trap a bank-messenger there, and there ought to be ten thousand francs for each of us if we succeed.”

The plans of the philosopher and murderer lacked nothing by way of completeness that day in December, 1834. He had foreseen everything and had prepared carefully every step of his crime. He had begun with a visit to a bank and the presentation of a bill drawn on a certain M. Mahossier, payable on December 31st at 66 Rue Montorgueil. This meant that on that date a bank-messenger would call and present the bill for payment, and as he would previously have been to other houses and collected money Lacenaire had every reason to expect that his third victim would yield him many thousands of francs.

On the morning of December 31st Lacenaire’s programme was complete. Dressed in his best clothes he reclined on a sofa reading his favourite Rousseau. Behind the sofa was a sack half filled with straw which he intended to hold the body of the murdered bank-messenger, and in a corner of the room was a large trunk which was to be utilized to convey the corpse to a deserted villa in a distant suburb where it was to be destroyed in a furnace. In fact, Lacenaire planned to be the first of the “trunk-murderers,” and it was only an accident that deprived him of that “distinction.”

The stage was now fully set for the third murder, and Lacenaire, who had become so natural a poseur that he could see nothing fantastic in an attempt to impress François with a display of philosophic calm, was apparently engrossed in his book when there was a knock at the door, the signal for action, although the intended victim could not be expected to know that.

François promptly threw open the door to admit a youth of eighteen, slim and delicate, of the name of Genevay. They saw that he carried a small black bag, which their imagination filled with wealth, and that only a fragile life stood between them and the money for which they craved. Lacenaire lost not a second in coming to grips, and as the youth bent over the bag which he had placed on the table the philosopher stabbed him in the back with the sharpened file which had already proved itself a reliable and trustworthy weapon in the Rue St. Martin.

But this time he was not dealing with a prematurely aged man whose strength had long since been sapped by vice. Genevay may not have been a Hercules, but he had the lungs of youth, and the first sharp pain set him yelling for help. It was such a lusty yell that François, whose appearance seemed to suggest that he knew no such thing as nerves, lost his head, and forgetting everything except the danger of publicity, dashed from the room and fled headlong down the stairs. To infect Lacenaire with his terror was an easy matter, and before Genevay’s wound was being attended to by a doctor his assailants were far off and well under cover.

The failure of the plot on which he had counted so much demoralized Lacenaire, and, hunger and privation proving too much for his flimsy armour of philosophy, he became a petty thief, which was, perhaps, more in keeping with his real character. But he was not to be successful even in his pettiness, and shortly after François was arrested for theft Lacenaire joined him in the same jail on a similar charge. This meant that the police had safely caged the two assassins of the Rue St. Martin and the two would-be assassins of the Rue Montorgueil, for it will be remembered that Avril was already in jail. But they were ignorant of the fact that they had the murderers of the Chardons under lock and key, and had it not been for the hostility aroused by Lacenaire’s contemptuous attitude towards his fellow prisoners the mystery might never have been solved. However, François, with that eagerness to betray which is characteristic of the average criminal, decided to save his own skin by sacrificing Lacenaire, and when the ruffian made his confession Lacenaire’s active career was as good as finished.

But Lacenaire had a confession to make too, for he was not to be outdone by a mere vulgarian who had proved himself so unworthy of his society, and when the philosopher started to confess he left nothing to the imagination of the police, not sparing either himself or his late comrade in crime, Avril. Mingling detail with epigram, he betrayed his friend with an enthusiasm which revealed fully the blood lust of the man whose only terror was lest he should die alone.

“I shall see Avril and François die first,” he boasted to the police, “and then I will lay my head under the knife with relief. After all, death is merely an operation, the success of which depends on what use one has made of one’s life.”

Lacenaire slept soundly through the night in his dismal cell and awoke the next morning to find himself famous. Paris, for once satiated with revolutions and politics, succumbed to the claim of the murderer, out of whom rumour manufactured many sensations. It was whispered in the boulevards that he was a great poet and a brilliant essayist, and that all his misfortunes were due to the fact that he had been repudiated by his father, who was said to have been a royal prince. All this was pure imagination, of course; but when the gossip filtered through to the prison, Lacenaire felt that he had achieved something at last. He was a third-rate poet and a tenth-rate murderer, but he had captured the imagination of the crowd, and it was something to be a hero in cynical Paris, even if the last act was to feature the guillotine. When he heard that those verses of his which had been rejected contemptuously by every editor in Paris were now being printed and circulated by the hundred thousand, his vanity was comical in its gravity, and he immediately set about composing fresh poems, writing freely and unfettered because he knew that as a dying man he owed no allegiance either to king or to convention.

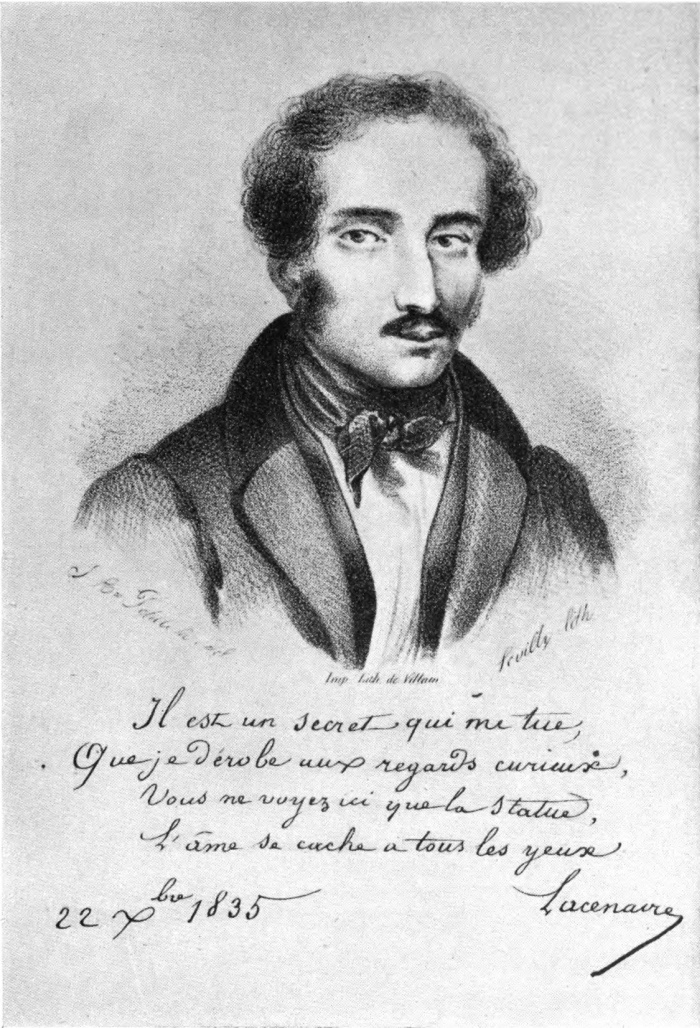

LACENAIRE (PIERRE FRANÇOIS GAILLARD)

His jailers, proud of a publicity in which they shared, humoured him without weakening the bars of his cage. But they were showmen now rather than jailers, and they acted as supers at the receptions in the prison attended by all sorts and conditions of Parisians in honour of the hero of the hour. What with his receptions, his literary work, and the necessity for providing each day with at least one epigram for quotation and repetition in the cafés, Lacenaire’s weeks of imprisonment before his trial passed quickly enough. Fully aware that society was going to cut off his head, not because he had murdered an infamous man and his helpless mother, but because he had attacked property in the person of the bank-messenger, Genevay, he did not commit the blunder of indulging in self-pity. His vanity saved him from that, and it was the only practical good he ever got out of a vice which had changed the morose child into a criminal.

The trial of the three prisoners, who were charged with murder, swindling and forgery, began on November 12th, 1835, and lasted nearly four days. A crowded court gratified the principal prisoner, who was anxious to prove himself equal to an occasion which promised to provide him with plenty of opportunities for histrionic display. He entered the court proudly conscious that although there were three on trial the public had already forgotten Avril and François. He knew it was Lacenaire they wished to see, and he did not disappoint them. Almost every day while in prison he had rehearsed his behaviour in court, and he was so word and action perfect that he was hardly ever at a disadvantage even with the dignified judge. His candour was as amazing as his coolness. Nothing disturbed or perturbed him, and he replied to the questions of the President of the Court with a frankness which would have gained sympathy for him had his recital not consisted of one horror after another.

“I have known Chardon since 1830,” he said, in a quiet, conversational tone, “but visited him only once; Avril went several times. We learned that he was to receive money from the Queen, and it was said to be an advance of 10,000 francs. I did not learn this from either of my fellow-prisoners, but from a person whom I will not name. I went to engage Frechard in the murder, who, however, declined. I cannot say whether the idea of the murder originated with me, or with Avril. I was armed with an awl, but Avril had no weapon. According to an agreement between us, Avril seized Chardon by the throat, while I stabbed him with the awl, and as Chardon struggled hard Avril seized the hammer-hatchet which was hanging behind the door, and finished the business.

“While Avril was thus engaged, I went into the room beyond, where I found Madame Chardon in bed, and killed her with the awl. Avril took no part in this second murder, as he did not enter the room till I was pressing the mattress upon the body. I was wounded in the hand by the awl, in consequence of it having only a cork for the handle, and the end of it was forced through by the violence of the blows. We carried off some plate, a sum of 500 f., and some clothes, besides an ivory figure of the Virgin, which we fancied was of value, but afterwards threw into the river, as we were offered only 3 f. for it. Avril sold Chardon’s cloak for 20 f., at the Temple, which sum he retained for himself. After the murder we went to bathe at the Bains Turcs, and, having cleaned away all the spots of blood, Avril went and sold the plate, while I waited for him at the Estaminet of the Epi Scie, on the Boulevard du Temple, where we dined, and afterwards went to the Théâtre des Variétés. When I went into Chardon’s, I heard the clock of St. Nicholas’s Church strike one, and it was about a quarter after when we left the house. In fact, the crime was perpetrated in the middle of the day. On the following day, I hired a lodging in the Rue Montorgueil, in the name of Mahossier, a law student, where I lived six days with Avril.

“I did not become acquainted with François till the 30th of December. I hired the apartment solely for the purpose of robbing a collecting clerk, to accomplish which I should have stopped at nothing. I previously made several attempts of this nature, particularly one in the Rue de la Chanverrerie, which, however, failed on account of the clerk being followed by a porter. The first time we inveigled persons of this description was merely to ascertain how far enterprises of that nature were likely to succeed. François, on the 29th of December, went to the house of a young man with whom I was acquainted, and declared that he was in a desperate state, having no resources; that he was proscribed, that, if arrested, he would be condemned for life, having been before convicted, and that he would kill a man for 20 f. The young man hinted that he knew of a business worth more than that, which he would undertake himself, were he not ill, and offered to put François in his place. François accepted, and was on the following day brought to me by the young man, whom I will not name. François and I went together to the apartment in the Rue Montorgueil, on the door of which I had written the name of Mahossier.

“On Genevay’s entering, I requested him to go into the farther room, where I seized him by the shoulder while François put his hand on the man’s mouth, but as he shouted murder, François ran away, and I after him. François, believing that if I was taken he himself might escape, pulled the door after him, but I succeeded in opening it, and ran out, crying ‘Stop the murderer,’ and several persons passed who showed me the way François had taken. On the following day, François, myself, and the person who introduced us to each other, went to Issy, to rob a relation of François, but not being able to succeed returned to Paris, where I took a lodging in the house of Pageot, under the name of Baton, and François under that of Fusillier. We slept together. Pageot knew who and what we were. It was I and François who robbed Mr. Richmond, in the Boulevard Montmartre, of a clock, which I sold to a dealer in old clothes. A plan was laid between myself and Avril for robbing a collecting clerk of M. Rothschild, but as he never came to the appointment, we were obliged to content ourselves with robbing the room we had been lent for the purpose of a pair of curtains.”

It was then Avril’s turn, and he was brought into court to give his version. It consisted of an attack on Lacenaire, an attack in which François later on joined, the two ruffians, who had the best of reasons for knowing the treachery of their leader, reviling him until they had to be threatened by the president. At one period the trial resolved itself into a warfare of verbal abuse by three ruffians animated by a desire for what they called revenge, and there was nearly a riot as a consequence. Lacenaire, ever cool and collected, more than once assured the court that he did not wish to escape the death penalty and that all he wished was to see Avril and François condemned with him.

Like all great trials it had its amusing moments. Thus when Avril wished to call a witness of the name of Robetti, who was then undergoing imprisonment, the president remarked that a person condemned to infamous punishment could not be admitted to give testimony.

“Monsieur President,” exclaimed Avril indignantly, “Robetti is only condemned to three years, and no punishment under five years is infamous.”

On another occasion when the president was closely questioning Lacenaire concerning his numerous swindles the prisoner yawned several times. He resented these reminders of crimes which reduced him to the lowest level of petty villainy, for the philosopher who is a thief is not taken seriously, and Lacenaire wished to inspire terror and not derision, but he endured the unwelcome examination for half an hour before he was moved to protest.

“Monsieur,” he said, with a cynical smile, “you’re forgetting your sense of proportion. Your questions produce upon me the effect of a surgeon who amuses himself with trimming a man’s corns when he is about to cut off his leg.”

The trial also had its dull moments, but they were not the fault of Lacenaire, who proved himself a first-rate actor, for there can be little doubt that the show of contempt for death was merely a mask, and that the luminous eyes and smiling lips concealed a writhing soul. But he made almost every witness contribute to his desire for further publicity, extracting from one a tribute to his courage and from another a reference to his poems which served to double their circulation. He treated the dock as though it were a drawing-room, and his attitude towards the judge and jury was that of an old friend who could not quite hide a consciousness of social superiority. The abuse of Avril and François left him unmoved; he brushed them from him as though they were flies, and he succeeded in infecting the audience with a little of his own contempt for them. When called upon to speak in his own defence he was brief and to the point.

“Gentlemen,” he said, without any sign of emotion, “one of the advocates has told you that I desire to live. No, gentlemen, life has no attraction for me. I am no stoic. Give me money and fortune and the enjoyment of life, and I will accept them at your hand, but the life of the hulks would be insupportable. I ask no favour. Deal with me as you think fit.”

There were other speeches, but no one took any interest in them, for it was Lacenaire’s trial, and the fate of Avril and François, two obscure vulgarians, was so unimportant as to savour of an anti-climax. In the opinion of the majority of those present the verdict was a foregone conclusion, but there were some who thought that the frankness and courage of the criminal whom Paris had put on a pedestal might hypnotize the jury into saving his life by coupling “guilty” with “extenuating circumstances.”

The jury, however, were relentless, and only in the case of François did they find “extenuating circumstances.” Lacenaire bowed like a courtier, and Avril heightened the effect of his leader’s philosophical acceptance of his fate by an outburst which disgusted the crowded court.

“I hope they’ll give me time enough to finish my memoirs,” said Lacenaire, on his way back to the prison of the Conciergerie. “It is a document the world will prize.”

There were nearly seven weeks of life left to him, and until the night he was told by the governor that his execution had been fixed for the morrow he enjoyed every moment. The precious memoirs—the usual conglomeration of calculated lies rendered almost credible by their vividness—pleased him mightily, for he foresaw the time when his crimes might be forgotten and his literary work remembered. He would have been crazy with joy could he have been told that many of the greatest writers of his country, from Victor Hugo downwards, were to immortalize him in their books. As it was, he had to be content with the brief fame of the rapidly passing days and comfort himself with speculations as to the future.

Two nights before his execution Lacenaire composed a lengthy poem which took the form of a prisoner’s invocation to God. Judged by ordinary standards it may be described as conventional and uninspired, but in view of the circumstances surrounding it it may be said to possess unusual qualities. Many famous books have been written in prison, but not by those condemned to die, and the poets of our prisons have been, as a rule, comically illiterate. Lacenaire’s poem therefore deserves attention, and I will quote its last eight lines by way of a sample:

Dieu que j’invoque, écoute ma prière!

Darde en mon âme un rayon de ta foi,

Car je rougis de n’être que matière,

Et cependant je doute malgré moi—

Pardonne-moi, si dans ta créature

Mon œil superbe a méconnu ta main.

Dieu—le néant—notre âme—la nature,

C’est un secret;—je le saurai demain.

La Conciergerie, 8 Janvier, 1836.

It was his intention to deliver a lengthy harangue to the vast crowd he expected at his execution and also to recite his poem, but when he arrived in the tumbril the sparsity of the crowd revealed to him that the authorities had taken special precautions to discourage a large attendance. Paris had been kept in ignorance of the date of the execution of the popular criminal and so was represented at the end by a few hundred persons, chiefly gathered from the houses within sight of the guillotine. They formed a crowd which was not at all to the liking of the philosopher whose philosophy did not include toleration of those he regarded as the lower classes. Yet it was not contempt which at the last moment, when he came face to face with the guillotine, stifled the words on his lips, nor was it anger which sent the blood from his cheeks. He had mocked at death in his prison; he had scorned life in his poems; but there was the head of Avril in the basket, and no philosophy could keep at bay the terror inspired by those staring, lifeless eyes.

Once he tried to speak to one of the officials, but only half a dozen words were heard, and he was almost unconscious with terror when the knife put an end to a life of thirty-five years which had known little that was not evil since childhood.

The magnificent salon of what was probably the finest private residence in Paris was crowded with distinguished men and women. They had accepted the invitation of their hostess chiefly from motives which were not complimentary to one who had the reputation of being a heartless adventuress and had in the course of a few years risen from poverty to wealth by trading on the weaknesses of men. Some were there because they wanted to inspect the mansion which was rumoured to have cost two million francs to furnish; others desired a close view of one of the most beautiful women of her time, and the majority had been tempted by the certainty of a banquet, followed by a concert provided by some of the most celebrated singers in the world.

The dinner was a brilliant success, and now the guests, rendered amiable and generous-minded by food and wine, applauded vociferously the singers and in the intervals chattered so animatedly that the noise was almost deafening.

It was during one of these intervals that the owner of the mansion walked over to the piano, where a middle-aged woman who once had been a star in London operatic circles was preparing to sing. When she noticed the approach of her patroness she uttered an exclamation of delight.

“I have acquired a new song especially for Madame,” she said.

“Indeed!” said the beautiful woman with the auburn hair and the rosy, plump cheeks. “May I inquire the title of it?”

“It is a song composed by one of your countrymen,” said the singer. “I thought it would please you to hear it because it would bring back memories of your childhood.” With a quick movement she separated the song from a sheaf and handed it to her.

When the younger woman saw the title-page she started, and her expression hardened.

“I do not wish you to sing this song,” she said hurriedly. “I have heard it so often that I am tired of it.”

The singer bowed, but before she could speak her patroness left her, for the giver of the feast was Cora Pearl, and the reason why she did not wish to hear “Kathleen Mavourneen” would have been obvious to the vocalist had she known that the world-famous song had been composed by Cora’s father. Crouch had fashioned the melody in the year of her birth and she had been brought up with it and, in fact, educated on the profits of its sale. “Kathleen Mavourneen” always reminded her vividly of the days when she was innocent, “joyful and free from blame.” But she had rebelled against the dullness of their old home in Devonshire, yet now, although a millionairess and able to spend two thousand pounds a week in her pursuit of pleasure, she would have given everything to be back again in that humble home in one of the fairest of English counties.

When Cora was fifteen so many persons praised her unusual beauty that, distressed by her parents’ impecuniosity, she longed to be able to turn it to monetary advantage. She had been well educated, and two years in a convent in France had enabled her to acquire the language of that country, but she knew that her intellectual abilities would not command much in the market, and young as she was, she realized that the stage was the only career open to her. She might not be a born actress, but her beauty would be a compensation, and after a considerable amount of secret planning she began to pay a series of visits to the theatre unknown to her father and mother. Everywhere she was repulsed, and she was returning home one night to the lodgings in London where the Crouch family were living, when she was accosted by a well-dressed and handsome man of middle age who had no difficulty in luring her into conversation. Cora Crouch believed she had a knowledge of the world greater than her years, but she did not read any sinister meaning into the polite phrases of the stranger, and, accepting an invitation to dine with him, found herself twenty-four hours later betrayed and deserted.

In the circumstances she was afraid to return home, and she decided to start life on her own account with a capital of five pounds, the small total of the money left behind by the stranger whose name she never knew. It was now very necessary that she should obtain employment, and it seemed to her that her luck had changed for the better when a theatrical speculator of the name of Brinkwell engaged her to sing and dance in a low-class café he was running in the West End. Unfortunately Brinkwell’s position was desperate when Cora, who adopted the name of Pearl for stage purposes, began her career, and when he disclosed the true state of affairs to her and offered to take her to Paris and find an engagement for her there, she had to consent.

Cora’s chief reason for leaving England was to place herself beyond the reach of her family. She was some years under twenty-one and therefore liable to be compelled by the law to return to her parents, and she knew she had gone too far to even be at her ease again in their presence. Hitherto she had been unlucky, but rather than confess failure and eat humble pie she was ready to venture into a city where she had not a friend and rely solely on her beauty to gain for her position and wealth.

As soon as convenient she got rid of Brinkwell and began to haunt the cafés where singers were required. Starvation wages were paid, but occasionally she was invited to dinner by some of the patrons, and as from the beginning she felt quite at home in Paris she did not mind so much the poverty and the loneliness it entailed. She was confident that in a city where beauty, especially when allied with youth, was deeply appreciated, she must make good eventually.

Life was an adventure and she an adventuress, and it was in keeping with her temperament and ambitions that she should have passed from poverty to wealth in the course of a few hours. One night she was singing with no very great success a simple French ballad when a young man sitting alone at a table near the improvised stage asked her to drink with him. She did not know who he was, and his appearance did not suggest that he was one of the rich young fools so common in the French capital, but she was attracted by his ingenuous countenance and she accepted.

When he began making love to her she laughed at him, and when he talked of laying at her feet the finest jewels in Paris she laughed louder than ever. The café was frequented by youthful poets and artists, most of them sons of small shopkeepers who were posing as geniuses until recalled to serve behind the parental counters. Cora was perfectly willing that her newly-made friend should spend what little means he possessed on her, but she did not intend to waste much time over him.

“Allow me to offer you supper,” he said, when they had finished their wine.

Cora accepted with a nod. For her the day was beginning, and she did not wish to return to her squalid room until she had reduced herself to such a state of exhaustion as to be unable to notice its hideousness.

“I will take you to a restaurant where they rob you,” he said, rising, and they passed out into the night arm in arm.

She was surprised when the shabby vehicle stopped in front of the most expensive and most fashionable restaurant in Paris, but she was positively startled when she observed with what deference her escort was received by the staff. The manager almost doubled himself in his efforts to be deferential, and the girl listened in wonderment as the chef, especially summoned from the kitchen, sketched out a menu which was a combination of taste and extravagance.

“You must be a prince,” she said, staring at him.

“At present I have the honour to be your host and that’s all I desire,” he answered.

But before they parted that night Cora Pearl was in ecstasies because she knew that she had captivated a cousin of the Emperor, who was so madly in love with her that he was willing to place at her disposal his entire fortune.

“If I can’t make you queen of France, I will make you queen of Paris,” he promised her, when he bought for her a house in the Rue de Chaillot which had proved too expensive for a merchant prince to maintain.

It was furnished regardless of cost, and a platoon of servants waited on Cora in liveries almost as gorgeous as that of royalty itself.

“I love flowers,” she said pensively. A week previously she had been overjoyed because her earnings had reached twenty francs.

“Then you shall never be without them,” the prince promised. “Summer and winter alike you shall have the rarest exotics.”

By keeping his promise he ran up a monthly bill which was never less than five hundred pounds, and often exceeded seven hundred. But this was only one of the many almost insane extravagances of the capricious coquette, who was intoxicated by the power suddenly conferred on her of spending without limit or hindrance.

Beauty is evanescent, however, a fact of which Cora Pearl was well aware, and, though her vanity was almost a mania, she could confess to herself that the time would come when those who knew her would smile incredulously when told that she once had been considered the loveliest woman in Paris. She therefore determined to have created for her an enduring proof of her beauty, and her admirer being willing to go to any expense she commissioned Gallois, France’s leading sculptor, to model her in marble. He asked for a fee of three hundred thousand francs—then worth £12,000—and the statue that resulted from his efforts is still said to rival the famous Venus de Milo.

What with the statue and a bath quarried out of pink marble at the cost of a quarter of a million francs, it is not surprising that in less than a year Cora should have spent £200,000. She had all the parvenu’s passion for meaningless display, and she behaved as though money ruled everything and everybody, and could procure everything she desired. When the prince departed in a panic, his place was taken by a young man of the name of Duval, whose father had made nearly a million sterling out of hotels and restaurants. Duval first became acquainted with Cora in her luxurious palace, and older and wiser men than himself had their senses taken captive by a woman who knew how to show off to the best advantage all the gifts nature had bestowed on her.

“Will you let me prove my devotion?” he said rapturously, when she showed signs of yielding to his entreaties. “Command me to die and I will die.”

“I want you to live and pay my bills,” she said, with almost brutal candour. “My desk is almost suffocated with accounts.”

He spent the rest of the day calling at various shops, and in addition to the eight thousand pounds which he distributed amongst the tradesmen of Paris who had trusted Cora Pearl, he placed to her credit the sum of one hundred thousand pounds.

“That ought to last a long time,” he said, when he told her of his generosity the following morning.

“We shall see,” she remarked, with a peculiar smile.

That evening she gave a banquet which cost six thousand pounds. The flowers alone involved an expenditure of twelve hundred pounds, and the entertainment was the talk of Paris for weeks afterwards, which was exactly what Cora wished.

With Duval’s wealth behind her she attained a foremost social position, although her enemies worked overtime saying spiteful things about her. Paris, however, has always been noted for its willingness to be entertained, and the entrée to its best society has ever been open to anyone with sufficient originality and ready money to guarantee escape from ennui. It was especially so in the days when Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie were at the meridian of their splendour and Paris was the gayest city in Europe. The virtuous grande dame might sneer at Cora, but she seldom refused an invitation from the woman who was known to give the finest dinners in Paris.

Cora took herself very seriously, for clever though she was, she failed to understand that she was really buying her friends, and that as soon as her financial resources gave out she would be friendless. She actually believed that it was her personality and her beauty that attracted, and that she was creating for herself an impregnable social position. But now and then she was reminded that Paris really regarded her as an eccentricity, a sort of social freak, a passing show to which no admission was charged. Once she was lunching in a restaurant when Daniloff, a journalist who specialized in recording the languid activities of the aristocracy, passed her table with a swagger which denoted calculated insolence. Although he and Cora were acquaintances, if not actually friends, he did not take his hat off. When she understood the purport of his challenging attitude she rose to her feet and in a loud voice ordered him to remove his hat.

“I regret I must refuse,” he replied, with a grin.

He had scarcely spoken when Cora seized a cane belonging to a gentleman near her and knocked the hat off Daniloff’s head.

The laugh was against the journalist, but he soon had his revenge. Cora, amongst other things, was childishly proud of her pearls, which were said to have cost Duval twenty thousand pounds. Now there were rumours in Paris that the necklace was an imitation one, and in her anxiety to kill this libel on her most treasured possession, Cora wore the pearls whenever she appeared in public. She was displaying them at the restaurant in which the hat incident had occurred when Daniloff walked straight up to her and began fingering the pearls.

The famous beauty was accompanied by one of the most noted duellists in France, but the journalist coolly unclasped the necklace and subjected it to a closer scrutiny. While he was doing this Cora’s host was pouring flattery in her ears, extolling her as the most wonderful and the most beautiful woman since Helen of Troy.

“Would you exchange these pearls for his fine words?” asked Daniloff disdainfully, his demeanour one of biting contempt.

Cora affected to misunderstand his attitude and she answered him lightly.

“Of course not.” Her face was radiant because by now all the diners were watching them and she was proud of the notoriety.

“Why not?” said the journalist, raising his voice so that all might hear him. “Both are equally false.”

With a cry of rage she sprang to her feet and snatched the necklace from him. In her fury she broke the string and the pearls scattered about the floor in a dozen different directions.

There were plenty of volunteers to recover them for her, but when they were counted seven were missing.

“Some of your friends must be dining here to-night, my dear Daniloff,” said Cora, with a cold precision which was more cutting than the most brutal sarcasm.

The journalist was indiscreet enough to rise to the bait.

“How do you know that?” he demanded, hoping no doubt that she would provide him with an opening for a smashing retort.

“Because seven of my pearls have been stolen,” she said, laughing derisively, “and we all know to what shrifts you poor journalists go in order to keep a roof over your garrets.”

Daniloff had no retort ready and wisely sought refuge in silence, but the story was all over Paris next day, and Cora was content to have lost her valuable pearls in view of the advertisement the incident gave her. But the same week she performed an act of generosity which astonished Paris.

Amongst her admirers was a youthful count who, fortunately for himself, tired of her blandishments and fell in love with the daughter of a general. As he and the girl moved in the highest circles, their engagement was a matter of public interest, and the count, terrified lest Cora should, in her spite and jealousy, cause a breach between himself and his fiancée, took the precaution of going to a lawyer and drawing up a deed of gift entitling the adventuress to the sum of a quarter of a million francs the day he was married.

Armed with the document he was as usual graciously received. She was always polite to men of means, and even if she was aware that the count had almost beggared himself in her service, she was all smiles and flattery when he entered her drawing-room. In fact, she was so effusive—it was only acting, but he did not know that—that he endured torture for half an hour before he blurted out the date of his forthcoming marriage. Cora’s eyes glinted and her lips tightened.

“But I have prepared a wedding present for you,” he hastened to tell her, producing the document. “Instead of having to give me a present you will be paid a quarter of a million francs on the day of my marriage.”

With a languid expression she held out her hand and he placed the deed in it.

“Thank you,” she said, without any feeling in her tone. “I think I have met your friend once or twice.”

When he had gone Cora tore the paper into fragments, which she placed in an envelope and addressed to the girl who was to be the wife of the man who had once sworn eternal devotion to herself. She was not in the least degree upset by his desertion—secretly she was rather glad to be rid of him because she knew that his finances were in a chaotic condition—but, womanlike, she was inclined to resent the transference of his allegiance to another.

When the daughter of the general received the mutilated deed of gift—she had been acquainted with her lover’s decision to placate Cora Pearl—she was touched by what she considered a very generous action. The payment of a quarter of a million francs to the adventuress would have entailed an economy resembling penury during the first few years of their married life, and the refusal of the money meant therefore a great deal to the young couple. Inspired by gratitude she actually called on Cora and thanked her in person.

“Oh, don’t praise me beyond my deserts,” said the adventuress calmly. “I did it in order to be talked about.”

The next morning practically every newspaper in Paris contained a reference to Cora Pearl’s generosity, and when she drove out in the afternoon she made almost a royal progress. In every café she was discussed, and stories concerning her wonderful beauty and the number of famous men she had subdued by it circulated all over the city. An enterprising theatrical manager promptly offered the heroine of the hour an engagement at a fabulous salary, and Cora agreed to appear as Cupid in an opera composed by a minor musician. Her acting was poor and the opera was worse, but everybody wanted to see Cora Pearl, and for a fortnight the theatre was crowded, although three times the usual charge was demanded for admission.

At the end of the second week when leaving the theatre escorted by cheering students she noticed Duval, pale-faced and shabby, regarding her with a mute look of appeal from the gutter. She had not seen him for nearly a month, a very long period in the memory of a fickle woman, and she had no desire to be accosted by him at the very moment she was being treated like a queen. It mattered nothing to her that the magnificent carriage into which she stepped had been paid for by Duval, and that the pair of thoroughbred horses which drew her to her home had been bought for a fabulous sum by him. Duval’s fountain of money had ceased to flow, and therefore she had no further use for him.

She sighed with relief when the carriage was closed and the coachman flicked the horses, but when she reached the mansion which Duval’s purse had maintained for over a year she found him on her doorstep.

“May I come in, Cora?” he asked humbly.

“No, my friend, it is too late,” she replied, without a smile.

“You don’t want me?” he gasped. His expression was haggard and if she had had a heart it must have been touched; but, although he had ruined himself for her, she had no pity for him now.

Without a word she passed in, and at eleven o’clock in the morning, while she was sipping her coffee in bed, her maid startled her with the news that Duval had committed suicide on her doorstep.

Cora was terrified, but not at all sorry for the young man. She was only afraid of the effect it would have on her reputation and on her recently-gained triumphs, especially her popularity with the mob. It was scarcely any relief to her when later she heard that Duval had only injured himself and that the doctors hoped to save his life. They succeeded after a hard struggle, but so far as Cora was concerned the mischief had been done.

On the Monday night she drove to the theatre, trembling and apprehensive. Her agitation was not without reason, for the moment she appeared on the stage the whole house hissed her, the more militant throwing inodorous vegetables at her. The curtain was rung down and she fled, and for days remained behind locked doors in her mansion, hoping that the fury of the crowd would abate and she would be able to resume her theatrical engagement. But her treatment of Duval had been too cruel and callous to be forgotten easily by the Parisians, and when an English duke wrote to Cora inviting her to come to London she accepted. It was a bitter humiliation for her to have to engage a suite of rooms at the Grosvenor Hotel under an assumed name, but a candid friend in Paris advised her that in view of the Duval scandal no hotel manager in London would admit her. She affected to disbelieve him, but on the night of her arrival in London she realized to the full how prejudiced the public were against her. Scarcely had her half ton of luggage been deposited in the hall, when the manager came forward and as politely as possible informed her that as she was the notorious Cora Pearl he must refuse to accommodate her. Cora stormed and raved, but he was not to be moved, and she had to rent a house in Mayfair, paying a rental of two hundred pounds a week for a five weeks’ tenancy.

In spite, however, of her recent misfortunes she enjoyed a series of triumphs in London. With the assistance of her ducal friend she gave receptions which were attended by scores of noblemen and a few unconventional women of rank. It was said at the time that a member of the English royal family constantly dined with her and that the servants had instructions to announce him as “Mr. Robinson.” Cora was delighted with her success, and it was with the utmost reluctance that she set out on a Continental tour, compelled by a rapidly diminishing banking-account as much as by a hint from a very exalted personage that London would be better without her.

A round of visits to the chief casinos of Europe occupied her for nearly eighteen months, and at Baden-Baden, where she was refused admission until she entered the gambling-rooms on the arm of a cousin of the Kaiser, she created a panic by providing her male hangers-on with squibs which they discharged at intervals and sent the gamblers scurrying out of the building in terror.

For this freak she was expelled by the police the next morning, but she went on her way rejoicing to Monte Carlo, and if she lost consistently she was never without an infatuated admirer to recoup her. Cora was not at heart a gambler, but she required something to occupy her mind until it was safe for her to return to Paris, and when at last she could enter the French capital without being assailed by a mob she was happy again.

Some years of the wildest extravagances and pleasure now followed. Her beauty remained to fascinate men and she made a gold mine out of it. Her mansion became a perfect treasure house and was one of the sights of Paris. She continued to give dinners and receptions which were rivalled by none, and, although other beauties had their moments of triumph, it seemed as though Cora Pearl was never to know dethronement.

And then, when she was only twenty-eight, the war of 1870 suddenly changed everything. It certainly effected revolution in the character of the pleasure-loving woman, for it transformed her into a very human and lovable personality. Simultaneously with the proclamation of war she sold the treasures of her mansion and converted the building into a hospital. She worked sixteen hours a day as a nurse, and during the siege of Paris she was ever to be found at the most dangerous and exposed places tending the wounded. She often closed the eyes of the dead amid the fire of the enemy, and she walked calmly through streets from which everybody else had fled. Naturally the soldiers worshipped her, and her beauty and cheerfulness in the most adverse circumstances acted as a tonic in moments of terror and panic.

When the Germans finally triumphed, Cora, in spite of her sacrifices, had sufficient jewellery left to maintain her in comfort had she been inclined to exercise wise economy, but she forgot that the overthrow of the Second Empire and the establishment of a republic would mean that the class which had hitherto paid for her triumph would be no longer in a position to bring costly gifts to her shrine.

With the proceeds of her jewels and a few lucky deals in pictures and objects of art she was able to hold her own for nearly ten years. But it was a hard struggle and worry and discontent killed her vivacity and took the roses from her cheeks. That was the reason why at forty she found herself in a cheap boarding-house in Paris and quite incapable of attracting even the most susceptible of men because her loveliness had gone and with it her old optimism.

Year after year she sank lower in the social scale, neglected and forgotten, and when in the winter of 1886 she died of cancer not a single newspaper recorded an event which twenty years previously would have startled the world. She had aged so much that the owner of the lodging-house where she expired put her age down as sixty when making his return to the public official whose duty it is to bury paupers. The cheapest of coffins was ordered for her and a local undertaker was told to bury her in a large common grave. He was about to “rattle her bones over the stones” when an aristocratic-looking man with iron-grey hair and impressive features and demeanour entered his shop.

“What will the best funeral possible for Madame Cora Pearl cost?” he asked, producing a bulging pocket-book.

The undertaker named a sum which he fully expected to be cut in half. To his amazement the stranger handed him notes for double the amount.

“The lady must have the finest funeral,” he said quietly, “and I rely on you to carry out my wishes. An agent of mine will be present and I warn you that you must fulfil your part of the bargain.”

He disappeared and was never seen or heard of again by the undertaker, but Cora Pearl would have been proud of her own funeral, because it was conducted on the same extravagant lines she adopted in her lifetime. Her unknown friend must have guessed that a splendid tomb was the only fit resting-place for one who had sacrificed everything for a temporary splendour and a transient and deceitful happiness.

The Gallery of Hypocrites is so overcrowded that the figure of James Cook, the Leicester murderer, is almost unnoticed. At first sight he seems out of place in it, and yet I am not sure that the oily little tradesman, with clasped hands and with the whites of his eyes showing towards the stars, is not greater than the kings and emperors, statesmen and prelates, littérateurs and philanthropists who out-glisten him. And if the test be supremacy in the not too easy art of hypocrisy in the condemned cell he is king of them all, a repelling, nauseating king, but all the same a veritable monarch.

No historian has ventured yet to enclose in a boundary of dates that elusive and illusive period to which dealers in clichés are fond of referring to as “the good old times.” Only recently has it been proclaimed that by permitting the “writing-up” of “popular murderers” by the press we are violating the good taste of that visionary epoch when perfection was attained so easily as to leave nothing for criticism. But whatever that period was it was not the early part of the nineteenth century when James Cook, of Leicester, committed a diabolical crime which might have been completely forgotten by now had it not been for the orgy of canting and ranting hypocrisy with which his alleged conversion was surrounded. Murderers of to-day may weary us because of the garrulity of their daily biographers, but it is no longer possible to bestow on an occupant of the condemned cell the halo of a saint and the crown of a martyr. Public opinion would not tolerate it for a moment even if we had a repetition of the phenomenon of a girl of good family brushing aside the prison chaplain and in an ecstasy of fanaticism hero-worshipping a loathsome murderer. Charles Dickens created two supreme hypocrites, Silas Pecksniff and Uriah Heep, and when he wanted material for the latter he embodied something of James Cook in his character.

However, before I develop this feature of a once famous case I will give a brief account of the crime. In the early part of the summer of 1832 Cook was a bookbinder with a workshop in Wellington Street, Leicester, a small, detached building which was overlooked on every side. He was twenty-two, and he had the reputation of being rather a good young man; in fact, he had been such an industrious apprentice that his master had left him his business. That he was quiet and inoffensive we can believe, and had he been as dependable as a master as he had been when an employé he might have attained a certain degree of prosperity. But Cook had grown tired of discipline before he became a man in the eyes of the law, and therefore he did not discipline himself, working only when the mood seized him, which was infrequently and usually at night. Business grew scarce and debts inevitably accumulated, and the end—bankruptcy—was in sight the morning he received a letter from Mr. John Paas, of High Holbom, London, informing him that the writer would call in person in the course of the week for settlement of his account. Mr. Paas was a brass ornament manufacturer who had supplied Cook with tools to the value of eight pounds, and the debtor knew that failure to settle would destroy his credit at one stroke. The young bookbinder, however, quickly reconciled himself to the thought of losing his business. It did not require much intelligence to arrive at a conclusion that he had no chance of rehabilitating himself. Quite apart from a disinclination for work of any kind he had lost the greater part of his connection, and whatever else happened it was certain that he would have to begin all over again and at a place remote from his native town.

He began to contemplate the possibility of emigrating to America where fortunes were to be made so easily, for your failure is fully persuaded that he has not failed because of his lack of merit but solely because of misfortune. But Cook was practically penniless and in debt, and emigration required capital. Once, however, the heavy, slow brain of the stoutish young man of medium height began to deal with the financial problem it gave birth to evil schemes, and when the letter from Mr. Paas arrived immediately found fresh inspiration in it. Cook rapidly conjured up a picture of Mr. Paas and his doings in Leicester. The London tradesman would have at least a dozen accounts to collect, and if it so happened that he was induced to call last at the workshop in Wellington Street, he would have a goodly sum in his pockets—perhaps a hundred pounds in coin and notes—for everybody in Leicester with whom the London manufacturer did business paid him in cash. What easier task than to kill Mr. Paas, destroy his body in a furnace, and before the mystery of his disappearance was solved—if ever it was solved—emigrate to America, make a fortune, and at the same time rebuild his reputation for respectability.

No sooner was the desperate and dangerous plot conceived than its author accepted it as certain of success. He was not gifted with any great intelligence—the weakness of his expression was a severe handicap to features otherwise pleasing—and he conceded society less. He knew it would be necessary to prepare for his crime by hoodwinking his neighbours in Wellington Street, but all he did was, on the evening before he was due to receive Mr. Paas, to light an unusually large fire in his workshop and leave it blazing away after he had locked up the premises. To his joy the bait took, the occupant of the house close by remonstrating with him for risking a conflagration which might have destroyed the street.

“The furnace is perfectly safe,” Cook answered glibly. “I banked it up myself. I am very busy just now and I may have to work late to-morrow night.”

Having thus prepared the way he was quietly confident when on the evening of May 30th, 1832, the boy he employed ushered Mr. Paas into the workshop. His visitor was a tall, well-built man of fifty, red-faced and amiable-looking, and he towered over the young bookbinder, who welcomed him with the intimation that he had the money ready to settle his debt. The boy was present during this preliminary conversation, but he heard no more, for Cook sent him away on an unnecessary and futile errand and told him to report the next day.

Within five minutes of the boy’s departure Mr. Paas was a corpse, Cook creeping behind him and striking him on the back of the head as the older man was bending over the table affixing his initials to a receipt. The furnace was waiting, and the murderer, having removed all the money from the unfortunate man’s pockets—it amounted to nearly sixty pounds—and taken his gold watch, rings and other articles of jewellery, proceeded to do his clumsy best to destroy every vestige of his crime. Of course he was not successful, and where an anatomical expert like Dr. Webster failed it was hardly necessary to record that in his efforts to destroy evidence Cook merely created proofs of his guilt. But he worked as he had never worked before, and only when he was completely exhausted did he take a rest. Then, fearful that his continued absence might bring one of his relations to the workshop—his father actually did call and knock, but receiving no answer went away—he went home at nine o’clock, but at one o’clock in the morning after four restless hours he declared that he must return to the workshop because he had an important commission to finish. That was Thursday, and he kept the furnace in full blast all day. Pedestrians saw the reflection of the flames through the covered window, and those who knew Cook marvelled that he should be so industrious. His more nervous neighbours talked of remonstrating with him again, but they did not interfere until late that evening. Meanwhile, Cook, in need of food and rest, went across to the “Flying Horse,” and having obtained both, flourished a handful of gold and silver in front of the landlord as he paid him. Then he sought recreation and diversion in a game of skittles. At eleven o’clock he was in bed at home when he was startled by a sudden ingress of excited men who told him that the landlord of the “Flying Horse” had broken open the door of the workshop, having been alarmed by the fire, and that he was wanted there because something suspicious had been found.

The murderer was fuddled by drink, but he regained his wits during the short walk, and although it must have been a terrible moment for him he displayed no terror when conducted into the room where he had murdered Mr. Paas and was confronted by a police constable.

The Leicester Dogberry of those days was known by the name of Measures, and from all accounts he must have been a very juicy specimen of the stage policeman. It was the settled opinion of Mr. Measures that crime could not be detected without the aid of beer, and he was further convinced that the peace of Leicester would be destroyed if he failed to inspect his favourite public houses at least three times a day. He was in the half-way stage of one very lengthy inspection when he was dragged to the workshop in Wellington Street, and now he had just sufficient sobriety to be able to stand on his own legs as he was being shown the smouldering flesh before he was presented to the suspect. Mr. Dogberry Measures shook his head gravely and murmured that there was reason for suspicion, and when Cook protested that the cause of all the pother and bother was merely horseflesh the semi-inebriated sleuth shook his head again and decided that the only thing to do was to postpone the investigation until he was sober and the flesh could be examined by a doctor.

“I must have security for your presence at the investigation to-morrow,” he said thickly. Cook promptly produced his father, who said he would go bail for him. That satisfied Dogberry, and Cook, having entered his father’s cottage by the front door, gathered together a few necessary articles and went out by the back, unwilling to distress Measures by the pathos of a long farewell.