* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

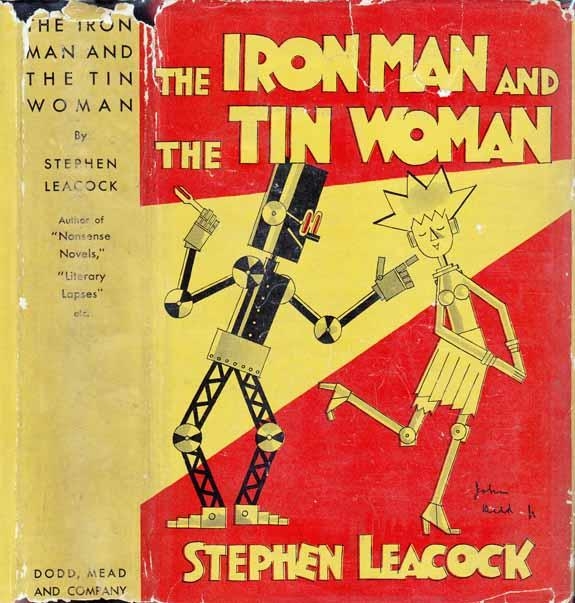

Title: The Iron Man & The Tin Woman

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Stephen Leacock (1869-1944)

Date first posted: Oct. 19, 2016

Date last updated: Oct. 19, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20161016

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE IRON MAN &

THE TIN WOMAN

| THE WORKS OF |

| STEPHEN LEACOCK |

| LITERARY LAPSES |

| NONSENSE NOVELS |

| SUNSHINE SKETCHES |

| BEHIND THE BEYOND |

| MY DISCOVERY OF ENGLAND |

| ARCADIAN ADVENTURES WITH THE IDLE RICH |

| MOONBEAMS FROM THE LARGER LUNACY |

| ESSAYS AND LITERARY STUDIES |

| FURTHER FOOLISHNESS |

| FRENZIED FICTION |

| WINSOME WINNIE |

| OVER THE FOOTLIGHTS |

| THE HOHENZOLLERNS IN AMERICA, AND OTHER IMPOSSIBILITIES |

| THE UNSOLVED RIDDLE OF SOCIAL JUSTICE |

| COLLEGE DAYS |

| THE GARDEN OF FOLLY |

| WINNOWED WISDOM |

| SHORT CIRCUITS |

| THE IRON MAN AND THE TIN WOMAN |

THE IRON MAN &

THE TIN WOMAN

With Other Such Futurities

A BOOK OF LITTLE SKETCHES OF

TO-DAY AND TO-MORROW

BY STEPHEN LEACOCK

TORONTO: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF

CANADA LIMITED, AT ST. MARTIN’S HOUSE

1929

Copyright, 1929,

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

printed in the U. S. A. by

Quinn & Boden Company, Inc.

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

RAHWAY, NEW JERSEY

“Pardon me,” said the Iron Man to the Tin Woman, “I hope I don’t intrude.”

He spoke in the low deep tones of a phonograph. His well-oiled cylinders were working to perfection, and his voice was full and mellow. The revolutions of his epiglottis, running direct from its battery with a thermostatic control to register emotion, was steady and unchanged.

“Not at all,” said the Tin Woman, “pray come into the drawing-room.”

She was working at a higher revolution, but speaking evenly and clearly.

The Iron Man inclined himself fifteen degrees forward from his third section, recovered himself by his automatic internal plumb line, turned seventy-five degrees sideways and took four steps and a quarter, as dictated by his optometric control, to a chair where he turned one complete revolution and a quarter and sat down.

But, stop! It is necessary to interrupt the story a moment so as to explain to the reader what it is about.

Everybody has been struck by the invention of the Iron Man, the queer mechanical being recently fabricated in Germany and exhibited there and in the United States. He is called a Robot, but he might just as well be called a Macpherson.

The pictures of the Iron Man show him with a head like a stovepipe, and a body like a Quebec heater. He is cased in nickel, jointed in steel, and one kick from his pointed iron foot would scatter a whole football team.

In other words, he has us all beaten at the start.

The Iron Man talks with a phonograph drum, sees with high-power convex mirrors, and gets his energy from electricity stored inside of him at 2,000 volts.

The Iron Man, it seems, is able to walk. He can walk across the floor of a room, step up on a platform, bow and take his seat. In this one act he displaces all public chairmen, chancellors of universities, and heads of conferences.

He is able, if you put a speech into his stomach, to reel it off his chest without a single fault or error. In this he outclasses at once all public speakers, platform orators and after-dinner entertainers. He can not only make a speech, but while making it he can move up and down, saw his arms around in the air, and gyrate with his head. In other words, the Iron Man can act, and after this there is no more need for living actors to keep alive.

Consequently, the Iron Man will rapidly take over from us a large part of the activity of the world. Anybody of sufficient means will soon have an Iron Man made as a counterpart of himself. When he has anything to do peculiarly difficult or arduous or needing great nerve, he will let the Iron Man do it. For myself, I intend to have an Iron Man do all my golf for me, which will reopen at once the whole question of the local championship. That, however, is only a personal matter. The point is that each and all of us will very soon be making use of an Iron Man.

Equally is it evident that some one will now invent a Tin Woman. She will be made of softer metal outside, but just as hard inside, with eyes that revolve further sideways and a phonograph drum of double capacity to go two words to one from the Iron Man.

So these are the two beings that are going to replace us individually in the world, to do our work and leave us to play. The timid human race will shrink behind its metal substitute. And even such a thing as a proposal of marriage, arduous, nerve-racking, and disturbing—will be gladly handed over to the deputy.

With which, let us continue the story.

The Tin Woman moved sideways eighteen degrees as guided by the reflected rays from the Iron Man’s concave eye-pieces and adjusted herself at half a right angle, with her base on a sofa.

There was a pause. Both waited until the situation grew warm enough to raise their temperatures to the speaking point.

“I have come——” began the Iron Man in a low voice. Then there was a click in his throat and he paused. He was not yet warmed up.

The Tin Woman, under the impact of his phonograph, altered the angle of her neck.

“Yes——” she murmured. Her phonograph seemed to revolve, but almost without sound.

“I have come,” said the Iron Man again, this time in a firm strong voice, while the hum of his self-starter seemed to give him an air of confidence, “to ask you a question.”

The ophthalmic plates of the Tin Woman, delicate as gold leaf, had been so adjusted that the sound-unit of the word “question” would start something in her.

“It is so sudden——” she murmured.

The Iron Man made an upright move on his seat so that his body-cylinder was perpendicular to his disc.

“I want you to marry me,” he said. He had to say it. These were the last of the words that had been put into him. He had no more.

But it was enough.

The mistress of the Tin Woman, whom she here represented, had had her adjusted so that as soon as the word “marry” hit her, it would set her going.

“——Oh, John——” she gasped. She rose up on her spring legs and fell forward with her tin bodycase flat on the floor.

The Iron Man stooped his body to eighty-five degrees, picked her up with his magnetic clutch, and then placed his facial cylinder close against hers so that his magnetic lamps looked right into her.

He put one steel arm around her central feedpipe and for a moment put her under a pressure of two thousand volts.

But he spoke no word. He couldn’t. He had used up all his perforated strip of words.

He stood the Tin Woman up against the wall, revolved twice on his feet to get oriented, and then clumped off out of the house.

The proposal was over.

And a few minutes later the Man—the real man, if he can be called so—was telephoning to the Real Woman.

“Darling, I am so pleased. My Iron Man has just come home and as soon as I opened him I knew your answer——”

“I’m so happy, too,” she said, “I could hardly wait to unlock Lizzie. I nearly took a can-opener to her, and when I heard your voice, I nearly died with happiness.”

“And we won’t wait, will we?” continued the man. “Let’s have John and Lizzie go through the Church Service part of it right away——”

“Just as soon as I can get Lizzie a new tin skirt, from the hardware store,” said the woman.

And a week after, Iron John and Tin Lizzie were married by a Brass Clergyman and a Cast Iron Sexton, while a Metal Choir sang their cylinders loose with joy.

In the old days, of say twenty years ago, when a man got sick he went to a doctor. The doctor looked at him, examined him, told him what was wrong with him, and gave him some medicine and told him to go to bed. The patient went to bed, took the medicine, and either got better or didn’t.

All of this was very primitive, and it is very gratifying to feel that we have got quite beyond it.

Now, of course, a consulting doctor first makes a diagnosis. The patient is then handed on to a “heart-man” for a heart test, and to a nerve man for a nerve test. Then if he has to be operated on, he is put to sleep by an anesthetist, and operated on by an operating surgeon, and waked up by a resurrectionist.

All that is excellent—couldn’t be better.

But just suppose that the other professions began to imitate it! And just suppose that the half professions that live in the reflection of the bigger ones start in on the same line!

We shall then witness little episodes in the routine of our lives such as that which follows:

“Mr. Follicle will see you now,” said the young lady attendant.

The patient entered the inner sanctum of Dr. Follicle, generally recognized as one of the greatest capillary experts in the profession. He carried after his name the degrees of Cap. D. from Harvard, Doc. Chev. from Paris, and was an Honorary Shampoo of half a dozen societies.

The expert ran his eye quickly over the face of the incoming patient. His trained gaze at once recognized a certain roughness in the skin, as if of a partial growth of hair just coming through the surface, which told the whole tale. He asked, however, a few questions as to personal history, parentage, profession, habits, whether sedentary or active, and so on, and then with a magnifying glass made a searching examination of the patient’s face.

He shook his head.

“I think,” he said, “there is no doubt about your trouble. You need a shave.”

The patient’s face fell a little at the abrupt, firm announcement. He knew well that it was the expert’s duty to state it to him flatly and fairly. He himself in his inner heart had known it before he had come in. But he had hoped against hope: perhaps he didn’t need it after all; perhaps he could wait; later on, perhaps, he would accept it. Thus he had argued to himself, refusing, as we all refuse, to face the cruel and inevitable fact.

“Could it be postponed for a day or so more?” he asked. “I have a good many things to do at the office.”

“My dear sir,” said the expert firmly, “I have told you emphatically that you need a shave. You may postpone it if you wish, but if you do I refuse to be responsible.”

The patient sighed.

“All right,” he said, “if I must, I must. After all, the sooner it’s done, the sooner it’s over. Go right ahead and shave me.”

The great expert smiled. “My dear sir,” he said, “I don’t shave you myself. I am only a consulting hairologist. I make my diagnosis, and I pass you on to expert hands.”

He pushed a bell.

“Miss Smith,” he said to the entering secretary, “please fill out a card for this gentleman for the Shaving Room. If Dr. Scrape is operating, get him to make the removal of the facial hair. Dr. Clicker will then run the clippers over his neck. Perhaps he had better go right to the Soaping Room from here; have him sent down fully soaped to Dr. Scrape.”

The young lady stepped close to the expert and said something in a lower tone, which the patient was not intended to hear.

“That’s unfortunate,” murmured the specialist. “It seems that we have no soapist available for at least an hour or so. Both our experts are busy—an emergency case that came in this morning, involving the complete removal of a full beard. Still, perhaps Dr. Scrape can arrange something for you. And now,” he continued, looking over some notes in front of him, “for the work around the ears, have you any preference for any one in particular? I mean any professional man of your own acquaintance whom you would like to call in?”

“Why, no,” said the patient, “can’t Dr. What’s-his-name do that, too?”

“He could,” said the consultant, “but only at a certain risk, which I hesitate to advise. Snipping the hair about and around the ears is recognized as a very delicate line of work, which is better confided to a specialist. In the old days in this line of work there were often some very distressing blunders and accidents due purely to lack of technique—severance of part of the ear, for example.”

“All right,” said the patient, “I’ll have a specialist.”

“Very good,” said the Hairologist, “now as to a shampoo—I think we had better wait till after the main work is over and then we will take special advice according to your condition. I am inclined to think that your constitution would stand an immediate shampoo. But I shouldn’t care to advise it without a heart test. Very often a premature shampoo in cold weather will set up a nasal trouble of a very distressing character. We had better wait and see how we come along.”

“All right,” said the patient.

“And now,” added the expert, more genially, “at the end of all of it, shall we say—a shine?”

“Oh, yes, certainly.”

“A shine, very good, and a brush-up? To include the hat? Yes, excellent. Miss Smith, will you conduct this gentleman to the Soaping Room?”

The patient hummed and hawed a little. “What about the fee?” he asked.

The consultant waved the question aside with dignity. “Pray do not trouble about that,” he said, “all that will be attended to in its place.”

And when the patient had passed through all the successive stages of the high-class expert work indicated, from the first soap to the last touch of powder, he came, at the end, with a sigh of relief, to the special shoe-shining seat and the familiar colored boy on his knees waiting to begin. Here, at last, he thought, is something that hasn’t changed.

“Which foot?” asked the boy.

“How’s that?” asked the man. “Oh, it doesn’t matter—here, take the right.”

“You’ll have to go to the other chair,” said the boy, rising up from his knees. “I’m left-handed. I only do the left foot.”

“My goodness!” said Edward to Angelina as they turned from the crowded street into the little shaded park. “That was a close shave!”

“What?” asked the girl. “I didn’t see.”

“Didn’t you? Why, it was the Inspector of Shoes. I was in such a tearing hurry this morning to get out and join you that I had no time to black my shoes properly. He passed us as close as that! Lucky shave, wasn’t it?”

“Hush,” whispered Angelina, “don’t speak just for a minute. I’m sure that man is watching us; don’t walk so close to me. I have an idea that he must be one of the new Preventive Officers against Premature Courtship.”

“Oh! That’s all right,” laughed Edward, “I have a license.”

“A license!” the girl exclaimed, putting her arm through his. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Well, to tell the truth,” explained Edward, “I only got it properly signed and visa’d yesterday. You see it had been reported that I went to your family’s house three evenings running and so I got a notice from the Visitors’ Department to ask whether I had a proper license. I had of course my general Suitable Acquaintance Tag, and I had paid my Callers’ Tax already, but it had been reported to the department that I’d been three evenings running to a house where there was an unmarried girl, and so of course they sent me a Summons.”

“Dear me!” sighed Angelina, “I suppose it’s wicked to say it, but sometimes it seems terrible to live in this age when everything is so regulated. Did you read that awfully clever novel that came out last week called ‘Wicked Days’ that told all about our great-grandfathers’ time when people used to just do almost as they liked?”

“No, the book was suppressed, you know, immediately. But I heard something of it.”

“It must have been awfully queer. Anybody could go round anywhere and visit any house they liked and actually, just think of it!—go and eat meals in other people’s houses and even in public restaurants without a Sanitary Inspector’s Certificate or anything!”

Edward shook his head. “Sounds a bit dangerous,” he said. “I’m not sure that I’d like it. Suppose, for instance, that somebody had a cold in the head, you might catch it. Or suppose you found yourself eating in a restaurant perhaps only six feet away from a person infected with an inferiority complex, it might get communicated to you.” He shivered.

“Let’s sit down,” said Angelina suddenly. “I want to go on talking, but I don’t feel like walking up and down all the time. Here’s a bench. I wonder if we are allowed to sit on it.”

“I’ve got a Sitting License for two in my pocket,” said Edward, “but I’m hanged if I know whether it’s been stamped.”

He took a little bit of government paper out of his pocket and they both scrutinized it.

“I’m afraid it’s not been stamped, dear,” said Angelina.

“Hush, hush,” said Edward apprehensively, “don’t say anything like that. Surely you know about the new Use-of-Endearing-Terms-in-Public-Places Act! For goodness’ sake, be careful!”

He shivered with renewed apprehension.

“Oh, hang it all, anyway,” said Angelina. “There’s a caretaker; ask him.”

“I can’t,” said Edward. “Don’t you see he’s got a Silence placard on him?”

“Then ask that policeman.”

“Ask the policeman! And get run into court for disturbing the police in the course of their duty! No, thank you!”

“Oh, Edward,” interrupted the girl, “of course we can sit down. Don’t you remember this is Wednesday morning and under the new decisions of the court people may sit in the parks at any time from 10 a.m. to 12 noon on Wednesdays.”

“Oh, come,” said Edward. “Hoorah! let’s sit down. Isn’t it fine to be free like this!”

They both sat on the bench under the trees. Angelina gave a sigh of relief.

“We were talking,” she said, “about how restricted everything is nowadays and I must say I don’t like it. I wonder how it all began.”

“I read a lot of the history of it,” said Edward, “when I was at college. This present Age of Restriction seems to have begun bit by bit; first one thing got regulated and then another. The more people got of it, the more they seemed to want.”

“How stupid!” said Angelina. She reached out and took his hand and then hurriedly dropped it. “Gracious!” she exclaimed, “I nearly forgot again.”

“It’s all right to take my hand. My new license covers it. Here, hold it if you like. You have to hold it palm up and only use one of yours and maintain a mean personal distance of three feet. But if you stick to that, it’s all right.”

Angelina took his hand again. “Go on with what you were saying,” she said, “about this Age of Restriction.”

“It began, I understand,” said the young man, “with the world war and after that it all came along with a rush. Everybody wanted Rules and Regulations for everybody else and everybody got what they wanted.”

“It’s all such a nuisance,” sighed Angelina. But—you were talking about your new license.”

“Yes. I got it made out and signed and counter-signed and visa’d, and it entitles me to the Privilege of Unlimited Courtship. It’s good till the 15th of next month.”

He spoke earnestly, turning towards her and moving to the very verge of the three-foot limit.

Angelina lowered her eyes.

“It entitles me among other things,” the young man went on ardently, “to propose marriage to you—provided, of course, that I comply with the Preliminary Regulations of Proposal of Marriage.”

The girl was still silent.

“I had first to notify the police that I meant to do it. That I have done. I have their consent.”

“I’m so glad,” murmured Angelina.

“Then I had to go before a Stipendiary Magistrate and make oath that I considered your mother fit to live with and that I would comply with the Family Sunday-Dinner Law. It all sounds complicated, but really, Angelina, it was quite simple. The Magistrate was awfully nice about it and passed me on to the Mental Board in less than half an hour.—They decided I did not have Infantile Paralysis, like so many poor chaps whom you see being wheeled out in perambulators every day. Ever so many young men are like that now.”

“I wonder why!” said Angelina reflectively. “They never were in the old days.”

“No,” said Edward, “but they were worse. They were Disobedient Adults. But listen, Angelina, I have the full right to speak to you now and I want to ask you whether (provided your personal certificates are all in order) you will marry me——”

Angelina had raised her eyes and was about to speak when a policeman stepped up to where they sat.

“Sorry, sir,” he said, “I’ll have to ask you and the lady to step across to the police station.” He took out his watch as he spoke.—“It is five minutes after twelve and you’ll have to answer to a charge of Unduly Restraining a Public Bench.”

Edward began to cry.

“Good Heavens!” Angelina exclaimed. “Do fetch a doctor. I’m afraid he’s got an attack of Infantile Paralysis. . . .”

“No, no,” sobbed Edward, “it’s not that. But it means that my proposal was made under illegal circumstances and it’s invalid and I’ll have to get a new license and try somebody else.”

“Fetch a perambulator,” said the girl. “He’s got it!”

Isn’t it just wonderful the way the invention of Radio has connected up the farthest parts of the earth? I was noticing the other day the reports in the newspapers of the messages sent back and forth between some celebrated explorer—I forget his name—who is flying around in African jungles, and the mayor of Chicago. I think it was Chicago; at any rate, it was the mayor of some great city. And the messages seemed to go back and forth as easily as if the two men had been side by side. I felt lost in wonder to think of the marvelousness and importance of it.

First of all, the explorer sent out by radio: “Greetings from Africa. I am flying over a field.”

And the mayor answered back: “Greetings from Africa received. Please accept greetings from all here. I am sitting in my office at my desk.”

Then back came the return message: “Accept cordial congratulations from Africa on sitting in your office. All here glad to know that all there are sitting there. Are flying low.”

And in return to that came the instantaneous reply: “Cordial congratulations on flying low. All here glad to know that you are there. Accept best wishes for being there. . . .”

Hardly had this information been conveyed across the atmospheric wilderness when the explorer, it seems, was able to get into contact with the mayor of San Francisco and radioed to him:

“Accept greetings from African regions to San Francisco. We are moving at about 75 miles an hour, warm sunshine.”

Back flashed the message: “Greetings received. Please accept greetings from San Francisco and congratulations on warm sunshine. We had a touch of rain last night.”

But it seems that these messages, important though they were, were only a few samples of the tremendously vital world information being carried back and forth by radio.

That very night, it appears, the President of Mexico “got” the city council of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, and sent out the vital words:

“Greetings from Mexico City. I am sitting in my chair.”

And the answer came back by the very next ether wave:

“City Council Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, acknowledges greetings President Mexico. We are eating breakfast. Most of us are taking kippered herring.”

Prominent citizens of both places agreed that the interchange of these messages would do a tremendous lot in fomenting good relations between Saskatoon and Central America. As a matter of fact, the first message had hardly got through when the city clerk of Saskatoon received a radio call from the President of Honduras, which said:

“Please send us a message, too. We have a machine of our own, nearly all paid for. Honduras sends cordial congratulations to Saskatoon on being in Saskatchewan.”

The new international courtesy that governs these things prompted an immediate reply:

“City of Saskatoon and Province of Saskatchewan acknowledge cordial congratulations Republic of Honduras. We are having a hard winter.”

The answer, “Congratulations on hard winter,” got through within the same day.

I am told that there is no doubt that the interchange of this last set of messages will do a tremendous lot for trade between Saskatchewan and Honduras. The president has already got through a message, “If you want any logwood, teak, or first-class cordwood, let us have your order.”

As a matter of fact, these messages of greeting that are reported every day or so prove on inquiry to be only a very small part of the messages of the kind that are sent back and forth from one great world-center to the other, conveying thoughts of absolutely vital importance for the welfare of the world.

Through the kindness of one of the operating companies, I am able to reproduce brief abstracts of one or two of these, thus:

“From Habibullah Khan, Acting Khan of the Khannery of Kabul, Afghanistan, to Secretary of Junior League Convention of North America, Toronto, Canada. Ameer Afghanistan and entire army congratulate Junior League on election of Miss Posie Rosebud as associate vice-president. All here join in cordial greeting to all girls in your league and any other. In placing orders for muslin or native bead work, don’t forget our salesmen. We have had a warm winter.”

To this message the League was able to send back a direct, unrelayed radiogram straight to the city of Kabul—City Hall office, top floor, Ameer’s private room, where it was decoded and disintegrated into Afghani in four minutes, twenty-two seconds.

“Junior League President, officials and members send greetings Habibullah Khan, or any Acting Khan, or Half Khan. Congratulations Afghanistan on Khan and Khan on Afghanistan. Convey congratulations army. Don’t forget Toronto for winter sports.”

I am not just sure whether the next message is a genuine one. It was tucked away among a heap of them, and in appearance it looked like the others. Whether it is genuine or not, at any rate it represents the wide desire of congratulating everybody on everything that is making the fortune of the radio apparatus.

“Sultan of Borneo congratulates William Jones of Alleghany County, Ohio, on reported prize at County Fair for cabbage two feet in diameter. All here send greetings entire population Ohio.”

Sometimes—so the operators inform me—rather pathetic cases are found of people who would wish to get into radio touch but have no correspondent. The operators receive messages such as: “Arab Sheik, Southern Sahara, with second-hand radio set formerly belonging to Pilgrim, would like get into touch small American Republic or Large American Corporation owning radio machine view to interchange congratulations. Large business territory; good opportunity ivory or gin.”

Or this message, which lay near the other in the basket:

“Sultan of Somaliland; plain congratulation in any European language; no extra charge for atmospheric reports.”

Looking over messages of this sort the other day, I couldn’t help reflecting on what a pity it is that the world didn’t have the radio messages in the days of the great explorations and discoveries. How much more vivid the pages of our history would have been! I suppose most readers are aware that there is a scientific legend to the effect that radio was invented and actually used centuries ago by the great Italian scientist and painter, Leonardo da Vinci. Later on, so it was claimed, he deliberately broke the machine and the secret of the process was lost and not again discovered till the present day.

If this story is so, it lends an air of truth and genuineness to a message that I found inscribed, along with its appropriate answer, on an ancient parchment. The documents, which were dated “October, 1492,” had at least all the appearance of age. The message read:

“Cordial greetings from Christopher Columbus to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. Have just discovered Japan.”

And the answer:

“King and Queen both here at breakfast in Escurial Palace, second piece of toast. Cordial greetings to everybody you discover. Your achievement greatest impetus onion trade.”

And yet, after all, perhaps Leonardo da Vinci knew what he was doing when he broke the machine.

Around the World in a Sight-Seeing Air Bus in 1950

The Man at the Gangway. . . . All aboard, please, all aboard! Five Dollars for the Entire Trip! All aboard! Vacant seats still in the forward saloon, sir, yes, sir. Yes, ma’am, lunch is served on board. All in! All aboard! (Clang! Clang! The gates shut, the doors slide, the bell rings, the whistle blows. Whiz!! The air bus is off. . . .)

Voice of the Rubber Neck Announcer. . . . Now, then, ladies and gentlemen, we are about to cross the Atlantic Ocean. During the next half hour you will enjoy the unique sensation of being entirely out of sight of land. Looking now from either the side or rear windows of this saloon, and directing your gaze downwards, you will perceive the actual waters of the Atlantic, 3,000 feet below us. Looking closely, you will observe a ruffled or mottled appearance of the water. This is the waves. At the present time what used to be called a storm or gale is moving over the Atlantic. In the romantic days of our grandfathers the passage of the Atlantic demanded an entire week. . . .

Voice of the Attendant (interrupting as he passes through the car). . . . First Call for Lunch! Lunch served while passing over Europe. First Call for Lunch!

Announcer (continuing). . . . The celebrated Christopher Columbus, who was the first Italian to cross the Atlantic, is said to have taken more than a fortnight to make the transit. Looking below now, we can just catch a distant glimpse of the Azores Islands, lying like gems of gold in a sapphire sea.

Vociferous Boy (passing through the alley way of the air saloon). . . . Cigars! Cigarettes, candies, chewing gum!

Announcer. . . . We are now circling across the famous Bay of Biscay and rapidly approaching the coast of Cornwall, the Land’s End of England.

Saloon Waiter in White. . . . Second call for lunch! Lunch ready in the dining saloon! Second call for lunch.

The Announcer. . . . If you look now from the left windows of the saloon you will see the coast of Cornwall. We are now passing over the South of England; the seaport just left behind is Plymouth; two minutes away is Portsmouth.—London? No, lady, not for three minutes yet.

Vociferous Boy. . . . Cigars, cigarettes, candies, chewing gum!

Announcer. . . . Look below you, ladies and gentlemen, and you will now see the city of London. Our speed is now slackened down to five miles a minute and we descend to an elevation of one thousand feet, so as to afford all passengers a full view of Westminster Abbey, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the other sights of London. . . . There you see St. Paul’s! Notice the roaring sound we make in going past it. That other noise on the right side is Westminster Abbey. That whizzing sound below us is the Bank of England——

Lady Passenger (to her Husband). . . . Well, I’m certainly glad to have seen Westminster Abbey. I don’t think anybody’s education is complete without seeing it. Didn’t you feel a kind of thrill when you heard it go by?

Polite Passenger Across the Aisle. . . . Is this your first trip around the world, ma’am?

The Lady. . . . Yes, it’s our first. I’ve just been dying to go for a long time, but of course my husband is always so busy that it’s hard for him to get the time. You see it takes a whole day.

Polite Passenger. . . . They say the new line of air boats are to do it in half a day. That will make a big difference. And yet I think I like this slower line better. After all, there’s nothing like taking things easy.

Announcer. . . . Coast of Germany! . . . Berlin! . . . Poland! Warsaw!

Vociferous Boy. . . . Cigars, cigarettes, candies, chewing gum!

Husband. . . . So that was Germany, eh? Much flatter than I thought. And Poland looks a good deal yellower than I had supposed. Nothing like foreign travel for clearing up your ideas. I don’t think you can understand foreign nations in any real sense without actually seeing them.

Saloon Attendant. . . . Last call for Lunch!

Announcer. . . . Here you see the wide plains of Russia, a vast expanse that it takes us twenty minutes to cross. The city that went past four seconds ago is Jefferson City, formerly called Leningrad and before that Petrograd and in early history, St. Petersburg.

Restless Child Among the Passengers. Mother, may I run up and down the aisle?

No, dear.

May I go and climb up the ladder to the top deck?

No, dear, you might fall off.

May I go and see where they cook?

No, dear.

Well, mother, what can I do?

The Courteous Traveler. . . . It gets a little monotonous for the children, doesn’t it, this part of the voyage?

The Lady. . . . Yes, indeed. Where are we?

The Courteous Gentleman. . . . Over Central Asia and of course just here there’s nothing to see—just the Ural Mountains, and Turkestan, and Samarkand, and the Desert of Gobi.

The Announcer. . . . In passing over the Desert of Gobi, to mitigate the tedium of the trip, we now turn on the radio and allow the passengers to listen to the latest world news coming over the waves.

The Radio (in its Deep Guttural Tones, Without Hurry). . . . New York, ten-thirty a.m. International Oil, 40; International Air, 62; International Fire, 81——

The Husband of the Lady. . . . Gee! International Fire up to 81!

The Radio (continuing). . . . St. Louis nothing, New York nothing: Boston one, Chicago nothing . . .

The Courteous Gentleman. . . . It’s pleasant, isn’t it, to keep in touch like this with the news of the world? It prevents the trip getting monotonous.

The Radio. . . . Bandits rob Chicago bank. . . . Bandits kidnap teller in Denver. . . . Bandits explode bomb in Detroit. . . . Bandits steal babies from Maternity Hospital . . . Bandits . . .

The Gentleman. . . . Yes, it’s nice to feel that the comfortable old world is still close all around us.

Announcer. . . . China! . . . Looking below you can see, if you look quickly, a Chinese rebellion. . . . The army of General Ping Pong will be seen in four seconds on the right. . . . The army of General Ham is attacking it. . . . By the courtesy of the company, our ship will drop bombs at the expense of the company on either General Ping or General Ham . . .

The Restless Child. . . . Oh, ma! Can I see the bombs dropped?

Yes, darling, look close and you’ll see.

The Gentleman with the Lady. How do they arrange about the bombing?

The Courteous Traveler. Oh, it’s done by the International Friendship Committee, but, of course, the company has to bear the expense. . . . Ah! I think that one hit General Ping Pong’s munitions dump!

Vociferous Boy. . . . Cigars! Cigarettes, candies, chewing gum!

Announcer. China. . . . City of Pekin. . . . The Yellow Sea. . . . Japan. . . . Tokio. . . .

The Radio. . . . Philadelphia nothing, Cleveland nothing!

The Saloon Attendant. . . . Tea served in the forward compartment—afternoon tea.

Announcer. . . . The Pacific Ocean! . . . Kamskatska! . . . The Aleutian Isles. . . . Alaska. . . . You are now again in sight of the United States!

All the Passengers. Hooray! Hooray!

The Gentleman with the Lady. . . . Feels good, don’t it, to get back again in sight of the old flag!

The Announcer. . . . The Rocky Mountains. . . . British Columbia. . . . Western Canada.

All the British Passengers. . . . Hooray! Hooray!

Vociferous Boy. . . . Cigars, cigarettes!

Radio. . . . Boston nothing.

Attendant. . . . Last Call!

Radio. . . . Oil eighty. . . . St. Louis nothing. . . . Bandits . . . murder.

Announcer. . . . Reëntering the United States. . . . All hand bags ready, please. . . . Kindly get ready for customs officers, immigration officers, prohibition officers, revenue officers. All persons who haven’t paid income tax will be thrown out. . . . Persons not on the quota kindly jump off into the air. Gangway, please. All out!

All the Passengers (in a babel of talk). . . . Well, good-by! Good-by! It’s been a great trip. . . . It certainly has. . . . And remember, if ever you come to Cincinnati. . . . I certainly will, and if you ever come to Toronto. . . . Well, good-by! Good-by!

Everybody has noticed the great change that has come over athletics within the last generation. To be in athletics, it is no longer necessary to play the game. You merely look at it. For the matter of that, you don’t really need to be there: you can hear athletics over the radio. In fact, nowadays, or at any rate to-morrow, you can see it all, with the television teleptoscope. Or, if you like, you can wait and see the whole contest in the high-class movies for sixty cents; or you can wait till next year and see it in the low-class movies for a nickel.

An athlete in the days of John L. Sullivan meant a powerful-looking brute of a man with a chest like a drum and muscles all over him. An athlete now means a pigeon-chested moron with radio plugs in his ears.

In old-fashioned football, thirty people used to play in the game and about thirty-three looked on. Nowadays, two elevens play the game and thirty thousand watch it. Even twenty-two is far too big a percentage of players. They block the vision of the athletes. Hockey is better. There half a dozen play on each side and thirty thousand look on. Prize fighting is a higher form still. Two play and two hundred thousand “athletes” participate.

And there’s more than that. Athletic teams don’t need to be connected with the places they come from—women seem to invade all sports equally—mechanical devices replace human skill——

Or stop! There is no need for me to write it all out in that way. That’s as prosy as a college essay.

Let me present the subject in the form of a few selections to show what will be the nature and fashion of the Athletic Page of any popular newspaper about a generation hence.

harvard-oxford conflict

(Extract from the Sporting Press of 1950)

Definite arrangements have just been concluded for the Harvard-Oxford football game of this autumn. The contest is now scheduled to take place in the oasis of Swot in south center of the desert of Sahara. The clarity of the desert sunlight, it is expected, will immensely favor the dissemination of the game by the Television-Teleptoscope, while the clear, still air will enable every faintest sound of the great battle to be carried all over the globe.

Front seats for the game in London, New York, Paris, Monte Carlo, Palm Beach, and other great athletic centers are already selling at prices ranging from ten to a hundred dollars.

Meantime the actual scene of the game itself will not be without a certain interest. It is calculated that the players, spare men, umpires, radio broadcasters, and television experts will probably number over a hundred people, a record attendance at any actual ground. No less than five airplanes will be needed to carry the players and the apparatus.

The athletic line-up is not yet complete, but it is officially announced that the center forward for Harvard will be, as last year, Youssouf-Ben-Ali of Ethiopia, with Yin Foo of Foochow and Billy Gillespie of Toronto on the wings. For Oxford the brilliant young Scottish captain from Dundee, Einstein Gorfinkel, will have as his front line stalwart Rum Rum Gee of Allahabad, Hassan Bay of Mecca, and Al Plunket of Orillia, Ontario.

A special feature of interest this year is found in the fact that one of the Harvard players was actually in attendance two years ago at Harvard University where he was janitor of a dormitory. At the same time two of the Oxford team, the brothers Hefty, are bona fide Oxford men, having been butchers in the town for many years past.

The sharp rise in the shares of the Sahara Syndicate consequent upon the definite announcement of this the greatest feature of manly sport, has led to a revival of the rumor that a German syndicate is making an offer for Oxford and Harvard.

derby day in 1950

An Exciting Finish

(Special Correspondence from Epsom Downs)

The advantage enjoyed by the present clock-work Derby over the now almost forgotten horse-race, in which living horses were used, was never better illustrated than in the exciting finish of the contest to-day.

Our older readers will perhaps recall the Derby as it was a generation ago and the way in which the introduction of machinery has gradually improved it up to its present standard. It appears that the first step was taken in introducing the Pari-Mutuel machine, which mechanically made betting odds.

The introduction of the stuffed bookmaker with clock work under his red waistcoat marked a further advance. The invention of the mechanical judge with high-power, 100 lens eyes, similar to those of the fly, and a running spool of registering tape in place of a brain brought for the first time a decision of absolute certainty.

The clock-work horse, operating on a moving platform geared at 200 miles an hour, enabled the whole race to be focussed into a small space, without straggling it out over miles of open country, as in our grandfathers’ time. The jockey, still remembered in old prints as a monkey-like figure in a little half jacket, naturally gave place to a power-house operator working with radio.

The cardboard stadium was filled (for photographic purposes) with some 10,000 (mechanical) spectators and gave an admirable setting to the event, recalling the days when thousands of people literally attended the Derby in person.

The great interest of this race lay in its exciting finish. When the photographic plates of the races were developed, it was found that Clicko, the English horse, had beaten the front leg of the American machine by the one hundredth part of a second. The announcement of this over the radio created an intense silence. Seismographic records show that ten million people held their breath at once. When they let it go it started a tidal wave that was felt as far as Japan.

passing of a great athlete

We chronicle with regret the death of Mr. Eddie Feinfinkel, the famous Scottish hammer-thrower. Mr. Feinfinkel died at his residence last evening after an illness—a general debility—extending over about forty years. It is said that he had put more money into hammer-throwing than any man of his generation.

In the earlier part of his career the late Mr. Feinfinkel obtained a world-wide celebrity as a toreador by organizing the Pan-American Bull-Raising Corporation of Montana. It was his intensive work at his desk in raising bulls that first undermined the great sportsman’s health.

Mr. Feinfinkel afterwards threw himself with enthusiasm into aerial work as a director of the Pan-American Transit Company, in which capacity he sent no less than one hundred experts across the Atlantic, with a loss of less than ten.

It was while recuperating in Scotland that the great athlo-magnate first conceived the idea of hammer-throwing, and engaged a corps d’élite of sixty Scotch gillies to throw hammers for him. Mr. Feinfinkel, whose interest and energy were tireless, often kept up the hammer-throwing for eight or nine hours at a stretch.

The loss of Mr. Feinfinkel will be greatly felt also in mechanical crap-shooting, automatic dice-throwing, and in all forms of nickel-in-the-slot athletics, of which the late magnate was a generous supporter. His funeral (mechanical) will be broadcast next Friday.

world’s baseball series

The world’s baseball series was held last night at the office of the Anglo-American-Pan-Geographic-Tele-Radio Company, New York. It has not yet been decided which club will be declared the winner, as the money is not all in yet.

minor items of current sport

Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race.—Advices from London bring the news that Oxford stands as the first favorite for the approaching annual boat race, the betting being at three to one. The Oxford women, it appears, are heavier than the Cambridge crew, some of whom are scarcely more than girls. Great interest, however, is still shown along the towing path, a number of the university professors turning out each day as spectators, wearing for the most part the new French chemisettes with ruffled insertions, so popular this season.

Among others, our correspondent noted Professor Smith, the biologist, in a dainty Cambridge blue creation under a picture hat, and the Vice Chancellor in a pretty frock of carnation, shot, or half shot, with something deeper underneath. The professor’s skirts are reported as slightly longer than last week.

revival of walking

The efforts of Old Time Sports Society are apparently being crowned with success, at least in one direction. Walking as a form of athletic sport is becoming extremely popular. Joseph Longfoot, the great East Anglian amateur, established the endurance record yesterday in a contest in which he walked four and a half miles without stopping. He was brought back in his helicopter not much the worse for his titanic effort.

Advertisement. Great Spring sale of sporting goods:—lorgnettes, field glasses, cushions, hot-water bottles, flasks, drinking cups, cigar cases, vanity boxes, men’s powder puffs.—Everything for the sportsman.

Lately there has been much concern with what is called “The Criminal Face.” It appears that there is a certain type and shape of head and features that always goes with the commission of crime. If you have it, there is no escape. You might as well go right away and ask to board in the penitentiary.

Experts can explain to you this criminal face, feature by feature and line by line. But the real trouble with the expert is that he always knows beforehand that the face he is analyzing is that of a man who has committed a crime. That colors his conclusions. What if we were to put before him, as a criminal, the face of a philanthropist? What then?

Thus we take the picture of a certain face and we know that it is in reality the face of a kindly old professor. Indeed, we have recently, let us say, seen it described on the occasion of a presentation of his portrait to the city in the following terms:

portrait of a sage

“The face of this distinguished scholar is known and loved by thousands who have listened to his inspired and inspiring words. It is a broad face, a kindly face, the face of a man with a wide heart, whose broad lineaments seem to indicate a corresponding breadth of sympathy. But there is a firmness, too, in the wide mouth, and character in the large but firmly chiseled nostril. The brow slopes nobly from the projecting frontal bones, the head is wide, of a width that tells of the capacious brain within. The ear is large, noble, and mobile, and the scant and snow-white hair remains as the mark of honor of a life spent in the service of mankind.”

But put the same portrait before the graphofacial expert, or facial graphologist, and tell him that it is a picture of a criminal recently sent to jail for life plus ten years, and ask him where he can see the tendency to crime, and this is the analysis you will receive of the countenance of the venerable scholar:

dangerous criminal

“The photograph is that of a male about sixty years of age, with marked criminal tendencies. Note the flat face, indicating complete absence of thinking power. There is something almost simian or ape-like in the width of the mouth, while the low, sloped forehead is but little higher in development than that of the most degraded savages. Such brain as this man could have would be sunk so low towards his neck as to be of little use to him. The premature loss of practically the entire capillary growth of the scalp, with the utter loss of pigment in the remaining part, indicates a life evil and irregular to the last degree.”

Or suppose, in the same way, that a facial graphologist looked at a picture of a great war hero, he would say:

“What a stern, soldierly face, the face of a man accustomed to command, keen, penetrating, and able at the same time to be ruthless, but always to be just.”

But show him the same picture and tell him that it was taken from the criminal records of the New York police, and he may say:

“We see here the true type of the hardened criminal—the small brain, the wide-set eye, and the dull look that indicates moral irresponsibility, etc., etc.”

But the trouble is that the world is coming to attach more and more importance, too much importance, to experts. When the facial graphologist gets a little further, we shall find our courts of law following in his wake. The face itself will become a crime and our police court morning records will contain little items after this fashion:

a menace to society

“Albert Jones, who later on gave in his name as coming from Chicago, undertook to take his face down town yesterday afternoon with the apparent intention of parading it on Main Street. Police Constable Simmons noticed Jones’s face moving through the air and at once arrested him.

“On being taken to headquarters and submitted to expert examination, it was found that his face was criminal in a high degree. The stunted lobes of his ears, for which he received six months in jail, are only one among varied evidences of guilt. He was given from twelve to fifteen months for various parts of his brain that were absent.

“The lack of eyelashes drew a caustic condemnation from the court, which warned Jones that a face like his is more than society is prepared to tolerate.”

Or things may go even a little further than this, and we may find the “facial criminal” filling a still larger field, thus:

criminal outbreak

“Telegraphic advices inform us that the city of Minneapolis and the surrounding suburbs are in the throes of a crime wave of unprecedented magnitude. The situation was precipitated by the arrival of a large excursion party of holiday visitors from the Doukhobor Settlement in Manitoba. It was noticed as soon as their faces emerged from the excursion train that they represented a mass of criminal possibility of dangerous volume. It was computed that not one in ten had had a hair cut once in ten months.

“The brachiocephalic index of nearly every one of them was of a kind to alarm the police force, while the facial angle of those who had the hardihood to show it justified immediate arrest. The entire excursion party were put on summary trial under the new Criminal Faces Statute and were ordered deported into Canada.

“Immediate difficulty arose, however, when the Canadian official refused all permit for reëntry into the Dominion, on the ground that men with faces like theirs are debarred from entry into a British country. The Canadian claim is that the men’s faces were all right when they left Manitoba, but took on their present criminal character when they got out at Minneapolis. For the time being, the entire party will be placed in a detention home.”

Ah, yes, and that last word “home” suggests to me another development that is bound to come when the criminality of the face is fully recognized. People will see that the proper thing to do for the criminal face is not to punish it, but to try to reform it. The idea will be replaced by the idea of redemption. A criminal face will be put into a home, where it will be surrounded with kindly and pleasant influences, where it may hear over the radio moral talks and sermons such as will cause the lobes of its ears to lengthen and will gradually lift up the lid of its brain to a normal height.

The situation will be marked by the appearance of such items as the following:

successful redemption

“John Henry Thomas, aged 70, was released to-day from the Central Criminal Face Reformatory, having been placed on parole by the authorities. The old man had spent the greater part of his life in the Reformatory, having been arrested at the age of twenty on a variety of charges, involving not only the lobes of his ears and the cubic capacity of his cerebellum, but the structure of his spinal ridge itself. His tendency towards homicide was too marked to permit him to remain at large.

“The old gentleman, in stepping out again into the sunlight after his long incarceration, expressed his appreciation of all that had been done for him. Not only had the lobes of his ears gradually assumed a harmless and even benevolent shape, but his cerebellum, formerly too small, was now larger than he could use and practically empty. All tendency to crime was declared vanished. The old gentleman did, indeed, in leaving, attempt to bite the warden’s ear, but this was not attributed to any remaining criminal tendency. It was rather thought to be an evidence of a new playfulness engendered by his long opportunity for improvement.

“It is understood that Thomas intends to devote the remainder of his days to work as a facial graphologist.”

In other words, my dear readers, my advice is—never mind your face. What if you do look like a criminal of the most dangerous type? You may not be really fitted for it at all.

The Rapid Approach of Our Final End

Professor Smithson of the Smithsonian Institution in a statement handed out to the press has declared that it is now only too evident that the rotation of the globe is distinctly slowing up.

This terrible news was almost immediately corroborated over the cable by the Astronomer Royal at Greenwich and by the Director of the Cavendish Physical Laboratory at Cambridge. Further confirmation followed from the Lick Observatory, from the Cape of Good Hope, and from the Chinese Watch Tower at Peking. It appeared that even the Bolshevik observer at Nijni-Novgorod, although only paid by the piece, had noticed the same thing.

Personally, I shall not easily forget the sudden sense of alarm with which the news filled me. Without being a scientist, I know, as does everybody else, that the globe turns on its axis once in every twenty-four hours. I have even gone so far occasionally as to speak of this as the diurnal motion of the earth. Without this diurnal motion there would be no alternation of day and night. If the world stops turning, then, at any given place, it will be either daytime all the time or always night. Either ourselves or the Hindoos will have to stay in the dark. Personally, I would rather wish it on the Hindoos if it has to be. There are more of them for company.

But this, of course, is not the whole extent of the disaster calmly threatened by the astronomers. If the earth stops turning, there will be no seasons, no tides, no winds, no weather. The pulse of life itself will slacken and stop. The human race—including me as well as the Hindoos—will be overwhelmed in extinction.

Like many other people, when I read that news at breakfast time, I wondered if it was worth while to start off to my day’s work. Why not sit quietly at home, and brace one’s feet against the study table and wait for the shock? If the world had to stop, it would surely be unwise to work all morning and find that the stoppage came in the noon hour.

It was only after reflection that I decided to read the news dispatches a little more carefully so as to get an idea of how long it would be before the end came. The general phrases used—a “distinct slackening,” a “definite loss of momentum,” etc., etc.—sounded pretty ominous. There was no doubt that the astronomers were all agreed about the main fact of the case, namely, that “within a measurable time” the globe will cease to turn. But the next question was to see how long they gave us to exist.

I found on closer examination that the rate of slackening is estimated by comparing the successive sidereal days as measured by a parallax. This is a scheme of which I never should have thought myself, but which looks good. The results obtained from it show that the earth’s motion is slackening by the millionth part of a second every day.

When I read that I felt cheered up. After all, there was quite a little time yet. If it takes us a million days to lose a second, that makes—let me see—a loss of one second in about 3,000 years. I guess we can stand that. After all, what’s a second! It seems that old Tut-ankh-Amen and his court went spinning round a millionth part of a second quicker than I do. All right. Let them buzz! I can jog along after them.

And at that rate the final end of the globe, when the Hindoos freeze in the dark and I frizzle in the sun, is still quite a long way off. If it takes 3,000 years to lose one second of our 24-hour spin, it will take 180,000 years to lose a minute of it, and 10,800,000 years to lose an hour of it, and we won’t lose it all till twenty-four times as long as that; in other words, the end will be due in Anno Domini 259,201,929.

Come, let us cheer up and face our fate like men. We have a quarter of a billion years in which to get all set for what is coming.

And even at that, I notice in looking over the figures above that I have made a slight mistake: what they said was not the millionth part of a second, but the billionth. That lengthens out our time here quite considerably.

Indeed, on the whole, I am inclined to agree with the reassuring statement that one of the astronomers appended to his report, that there was no immediate occasion for alarm. No, I think not.

Scarcely had I recovered from the alarm suggested by the reports of the world coming to a stop, when I noticed a new astronomical alarm sent out from Greenwich and reluctantly corroborated by Washington.

It seems that the continents are sliding apart and that we are drifting out into the ocean. England appears to be drifting westward towards the magnetic pole, and the upper part of the American Continent is moving nearer to Asia.

The consequences of this are certainly alarming at first sight. If Great Britain disappears—Ireland first—into the northern ice, and San Francisco lands up against Yokohama like a chip floating in a horse-trough, where are we? Of what use all our years of effort?

But here the reassurance again follows, partial though it is and somewhat short of what one would wish. The rate of motion is calculated to be such that we are six inches further away across the Atlantic than we were a hundred years ago. Ship ahoy! We can still call to them. Anybody who cares to divide six thousand miles by six inches can tell to a nicety just when the Asiatics will come scrambling over the bulwarks.

In short, I should like to be allowed to pass a word of advice to the astronomers and geologists. Don’t announce these things ahead in this alarming way. Wait till they happen and then feature them up large when they’re worth while.

I understand that there are lots of other geological and astronomical disasters coming. It seems that the coast line of both New England and England itself is falling into the sea. A whole barrow load of dirt that was left near Shoreham by William the Conqueror has fallen in. Old Winchelsea and St. Michaels have rolled under the water. Passamaquoddy Bay is engulfing New Brunswick. Never mind. Let us eat, drink, and be merry. We don’t need to board on Passamaquoddy Bay.

The sun, it seems, is burning out. A few more billion years and its last flicker will fade. Many of the stars are dead already and others dying. The moon is gone—a waste of dead rocks in a glare of reflected light. Even empty space is shrinking and puckering into curves like a withering orange.

Courage! Forget it! Let us go right on like a band of brothers while it lasts.

Another Splendid Volume Added to the Growing List of Memoirs

Note: The reading public of to-day adores memoirs. The publishers report that volumes of memoirs still continue to be among the best sellers. Readers apparently will take an intense interest in anything, provided it is put before them as something that somebody remembers. I understand that among the forthcoming volumes are to be “The Memoirs of a Boy Scout,” “Memoirs of a Girl Guide,” “Memoirs of a Bootlegger,” and many other fascinating volumes.

In anticipation of these, I venture to present here in brief outline some very striking selections from a work that will probably break all records as soon as published in full, “The Memoirs of an Iceman.”

My people came from Iceland. At least I have always heard my father say that his grandfather York Larfitorf had come from Iceland. His great uncle was one of the Henry Fjords of Norway. I understand that my grandfather settled first in Labrador, but, finding it too warm there, he moved to New England and thence to New York.

My father, however, was by nature a cold man and seldom spoke of his past.

My earliest recollections as a child go back to the Spanish-American War, which I suppose few people now alive can recall. It was fought between the United States and Spain. My father, who had a keen grasp of international politics though only a workingman, told us that he thought that the United States would win. I can distinctly recall the outbreak of the war and how my father came home after his work and laid his ice on the table and said there was going to be a war. My mother took the ice and put it away for breakfast, but said nothing.

My memory, which is still excellent, although I am nearly thirty-five, brings back to me distinctly the New York of those early days. My readers will realize that it was before the days of the motor cars, and that before the days of the motor cars there were no motors.

I distinctly recall that when I got my first regular job in an ice-house I had to walk from Brooklyn to Yonkers every day to my work. But we thought nothing of it in those days.

Life was very much simpler and quieter in those days, as there were only four million people in New York then, while such places as Jersey City and Newark were mere suburbs with less than half a million people in them. The highest buildings in the little metropolis of those days were only thirty stories high, though we already called them “skyscrapers.”

Looking back now on this, I am compelled to smile at it, which I suppose few people could do. I remember how, when the first thirty-story building was built, my father—who though a workingman was a man of great natural shrewdness—said he’d hate to fall off the top of it.

Work began with me early in life and has been more or less continuous, which is a matter I do not regret, as I consider that it is largely owing to an active life of work that at thirty-five I still have all or nearly all my faculties and my mind is at least as bright as it ever was.

My father’s influence secured me a position shoveling sawdust in an ice house, where my own industry gradually raised me to the top. As it is possible that some of my readers do not understand the technique of an ice-house, I may explain that our work in shoveling sawdust was of a highly specialized character demanding not only bodily strength, but skill, courage, and morality.

In the winter when the ice was put in, it was our duty to shovel the sawdust on top of each layer of ice, so that for every layer of ice there was above it a layer of sawdust.

Perhaps I can make my meaning clearer if I explain that the ice and the sawdust were laid in alternate layers; a good way to understand what I mean is to grasp the idea that the ice was covered with the sawdust and that the sawdust was over the ice. I am afraid that I cannot state it more simply than that, and the reader must either get it or miss it.

This was our work in the winter. In summer our task was reversed so that we shoveled the sawdust off and shoveled the ice out again, which lent a very pleasing variety to our work and prevented it from being monotonous. We thus rose and fell each winter and summer.

I recall very clearly the memory of some of my friends and fellow workers, such as John Smith, William Jones, Jim Thompson, and Joe Miller. I mention their names here not because the reader would know them, but because they are just as good as any other names and they help to fill up the memoirs.

I can very distinctly remember the presidential election of 1908. Excitement ran high, as it was felt that one or the other of the candidates was practically certain to win. My father took no part in it. He always claimed that a man delivering ice ought to keep away from the heat of political partisanship. He himself said that he would just as soon hand the ice to a Democrat as to a Republican.

With only a slight effort of memory I can bring back the recollection of the beginning of the great war. At the time I was only twenty years old, but even at that age my mind was nearly as developed as it is now, and I understood that if war began there would certainly be fighting.

My father, who followed closely all that was in the papers, was greatly excited over the war and was convinced that Belgium could easily beat France, though it turned out that he was mistaken. He himself was able to keep in touch with the war situation, as he was engaged in loading ice on the meat-ships that left almost daily for Europe. Added to this, his own European descent gave him a sort of inherited insight into European politics and he felt sure that in the end Norway and Sweden would come out ahead.

All this seems many years ago, and those days have drifted so far into the past that few can remember them. The war came to an end at last and was succeeded by Prohibition, and Aerial Navigation and other things. On these I must not touch, as I am now getting within living memory. Indeed, it was shortly after the war that my failing strength at the shovel necessitated my retirement from active shoveling.

The partial collapse of my mind, which happened at the same time, led me to undertake, on the advice of my medical attendant, the writing of these memoirs. It was his opinion that my mental powers had reached a state of decline, which would guarantee their success. My publishers assure me that this prediction has been amply justified.

Note: The publication of the “Memoirs of an Iceman,” printed above, proved to be a mere fanning of the flame of public demand. It was found necessary to follow it up immediately with the “Memoirs of a Night Watchman,” as here related.

I have the honor to belong to a very old family connected for generations with the night. I have heard my father, who was a furnace man, say that his ancestors were highwaymen, and he would speak of the blessing that coal heating had brought to the world in opening up night occupations for men of adventurous character.

While I was still but a little boy, my father would take me with him on his rounds. I would sit and watch him stoke up the furnace in the homes of the rich, and after he had brought it to a glow, Father would fetch some eggs from the ice-box upstairs and fry them in the furnace; while we ate them, Father would talk to me about the night and why it was superior to the day.

As our clientele was a rich one, I became accustomed early in life to move in luxurious basements with cement floors and spacious coal rooms, which has given me ever since an ease of bearing and a quiet step that no doubt helped the success of my career. We fed well everywhere, for my father believed in a generous and varied diet; on the other hand, he drank but little—a pint or so of champagne, perhaps, or if the night were cold, possibly a touch of old French brandy. For me he would open, perhaps, a pint of claret, but we drank it always in the cellar.

My father was very old-fashioned and strict in his ideas, and made no use of the drawing-room nor even of the dining-room, except, perhaps, on some special occasion. In one or two houses, where the billiard room was in the basement, Father and I would knock up a hundred points after his work was over. But in all such matters he was strict; only in very, very cold weather, for example, have I seen him make use of a sealskin coat for his work at the furnace.

As a rule, we had the night to ourselves; there was no one moving in the houses. And after the furnace was well stoked up and burning nicely, Father would sit on a trestle in the cellar and talk to me of the principles of ventilation and of the question of clinkers and back-drafts, so that I learned a great deal in being with him.

We usually arrived home a little before daybreak, bringing home breakfast for my mother and my younger brother. Father would generally bring home a satchel of coal with him, and would give some also to any of our neighbors who lived in the same basement as we did; for, after all, as my father said, the coal cost only the trouble of carrying it. We generally got to bed right after breakfast, as we kept early hours.

On Sunday, Father and I went to church, or rather to several churches, where Father tended fires in the basements, from which we could hear the organ. My father had no religious prejudices, and told me that he would just as soon fire one church as another. But he was rather bitter, for so mild a man, against Quakers and others that refuse to have heat in their places of worship. My father regarded them as misguided.

Meantime, I attended night school regularly, as Father laid great stress on education. He would have wished me to go from night school to a night college, and if possible to take a degree. Father said he had known several college graduates in furnace work, and considered them fully equal to first-class men. He always spoke of Oxford with great respect, and recalled that when he was a young man in marine boiler work on night shift, they looked on Oxford men as better suited for that than anything else.

But I was young enough and ardent enough to view education with impatience. I wanted to get forward in life, and dreamed already of being a night orderly in a hospital or a night guard in a penitentiary. Father had some influential friends in the penitentiary, and he said that when they came out he would see what they could do. But the chance never came my way. We also talked of banking, and Father said that if you could once get a footing in a bank at night, there was no telling what it might lead to. He had a friend who was very high up in one of the banks; in fact he worked on the principal vault itself, but nothing came of that idea either. Sometimes, too, we talked of the sea, and of course Father, as I said, had been a sailor himself (in the stokehold), and my imagination was fired as that of any boy is with the romance of the sea. I loved to picture myself in the stokehold of some great ship, sifting ashes and raking out clinkers.

Among such day dreams, or rather night dreams, I grew gradually toward manhood. Meantime, I had tried out a few desultory occupations, but found none to my liking. For a while I held a post as night porter in a family hotel, my hours being from 1 a.m. to 7. But it was too disturbed. I found that I had hardly settled down to my morning newspaper, next morning’s, for an hour or so, when there might be a ring of a bell, or a casual arrival that necessitated my presence.

The surroundings were not congenial, for though the lounge room was fairly comfortable, the library was poorly selected and unsatisfactory. I worked also as night clerk in a fire station, which I found congenial and quiet, but in the second month of my work there was an outbreak of a fire in a neighboring part of the city and I left. Chance fate, however, decided where deliberate intention failed.

I returned home one day to find that my father had given up his job to accept a more or less permanent position in the county penitentiary. His removal there was not wholly of his own choice, but his duties were entirely congenial, as he found himself in charge of five night furnaces where his companions were men of education and culture, several of them college graduates. Indeed, his circumstances were such that at the expiration of his original contract, which I believe had been for three years—a matter of insistence on the part of the authorities—Father was invited to stay on as a salaried member of the staff. The change involved very little disadvantage, except that he lost his uniform and had to supply his own clothes.

Meantime, as a compensation for Father’s removal from his family—a matter on which his contract insisted—influential friends obtained for me the post of night watchman in a large downtown office building.

This position I have now held for fifty years, during which time I have every reason to believe that my career in and through the building has been a complete success. My hours are from midnight, when the last of the day staff leave, until 6 a.m., when the first of them come back. During this time it is my duty to visit all the doors of the offices and try the locks of the rooms, though, thus far, I have never been able to get into them. It is also necessary to punch a time clock on each floor of the building every half-hour. It is a crowded life, and in a way I shall not be sorry when some day the time for retirement comes.

I have found by experience that it is scarcely possible to do any serious reading, as it is interrupted every hour by duties. After the first twenty years I read less and less, and after the first thirty years I got into the way of contenting myself with reading the telephone book and the calendar. The necessity of keeping posted all the time as to which day of the month it is prevents intellectual stagnation.

Nor is it, as my reader might imagine, a life without incident. Every ten years or so something happens. I recall distinctly how, about twenty years ago, the burglar alarm rang, but I heard it in ample time to leave the building. On another occasion there was a great fire a few blocks away, which prevented all thought of sleep.

But yet I have begun to find that in the long run the position has a certain monotony, a kind of dullness about it. This feeling did not dawn on me at first, and often I forget it for five years, but it comes back. I ask myself, is this after all quite the work and quite the life for an active man? I asked myself this six years ago, and very soon I intend to ask it of myself again.

I am well aware that at my age, seventy, the time has hardly come to think of retiring. There is a man engaged in the next building on the street (I was talking to him only two years ago) who is nearly ten years older than I am. But without retiring from work altogether, I often think I may give up my present job and strike out into something more strenuous.

But no doubt many people think that.

Note: No apology is needed for the publication of the manuscript here presented as the Confessions of a Super-Extra-Criminal. The eager and unsatiated demand of the public for revelations of the underworld is a guarantee of the absorbing interest with which the story will be received. Needless to say, the name assigned to the writer is a purely fictitious one. His real name we are not at liberty to mention, inasmuch as the mere whisper of his whereabouts will lead to his immediate execution in four different countries. If the government of Mexico, either government, could get hold of him, he would be garroted at once, while his condemnation to the guillotine in France only awaits his own consent. More than that, there are a number of his fellow criminals of the past who would knife him at sight, and others who wouldn’t even wait to see him. Our readers will understand this when they read what he writes. We may add that we have done nothing to edit or improve the style of this confession. We couldn’t. It is written in that straight-out, right-here-and-now, let-me-say-at-once form of composition that carries conviction with it—either present or past.

I want to say right here and now at the very start that there was no reason why I should have grown up to be a garage man. It was entirely my own fault. I had a good home and every opportunity to keep straight, and I had, too, gentlemen, the best of mothers.

“Ed,” Mother would often say to me, “keep straight,” and if I had listened to her, gentlemen, I wouldn’t have been through all that I went through, gentlemen.

But perhaps there was something wild in my blood that disinclined me to ordinary steady industry. My father had a regular job with a municipal garbage wagon where they trusted him with everything, and he would have taken me into it with him so that I would have grown up in that. However, nothing would do me but loafing around with a loose crowd of boys and talking about this man or that who’d made a clean-up as a plumber or garage man or a dry cleaning explosives expert, and never got caught.

We used to see them around the pool rooms nights. There was Dick Dynamite, or Dynamite Dick, as we used to call him, who was a nitro-glycerine man and worked in dry-cleaning shops blowing the buttons off vests; and there was Blow Torch Peter, who was one of the most daring men in the plumbing game, and Short Circuit Charlie, who had tied up the electricity in a downtown office for four hours single-handed with nothing but a pair of pliers and a screwdriver; and there was Water-Power William, a big hulking-looking fellow with a face as innocent as they make them, who had frozen up the water taps in one of the big hotels. All these men went about openly dressed in mechanics’ clothes, but it was mighty hard to prove anything against them. Every one knew, for instance, that Blow Torch Peter was a plumber, but they couldn’t prove it on him. It was known, too, that Dynamite Dick worked in dry cleaning, especially as he was reckless in his work and each explosion was bigger than the last, so that sometimes he’d blow off a thousand buttons in one day, but they could prove nothing.

And, of course, if any of these men got pinched, they always had enough money to hire one of the judges of the supreme court to defend them and got off pretty light.