* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Softfoot of Silver Creek

Date of first publication: 1926

Author: Robert Leighton (1859-1934)

Date first posted: Sep. 1, 2016

Date last updated: Sep. 1, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160901

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

SOFTFOOT OF

SILVER CREEK

BY

ROBERT LEIGHTON

Author of “Woolly of the Wild,” “Sea Scout and

Savage,” “The White Man’s Trail,” etc.

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED

LONDON AND MELBOURNE

1926

Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd., Frome and London

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | A Playmate’s Peril | 7 |

| II | The Shooting Contest | 14 |

| III | The Gift of Courage | 18 |

| IV | The Buffalo Hunt | 22 |

| V | The White Man’s Medicine | 28 |

| VI | The Marked Arrows | 34 |

| VII | Red Squaw Cañon | 39 |

| VIII | Ghost Pine Gulch | 47 |

| IX | Kiddie of Birkenshaw’s | 51 |

| X | In the Toils | 60 |

| XI | The Cry from the Cliffs | 67 |

| XII | On the Track | 74 |

| XIII | The Bridge of Perilous Adventure | 80 |

| XIV | Signal Fires | 87 |

| XV | A Gift for the Crees | 92 |

| XVI | Softfoot’s Lone Scout | 100 |

| XVII | Softfoot Meets a Friend | 107 |

| XVIII | Little Cayuse | 112 |

| XIX | Paleface and Redskin | 117 |

| XX | The Prairie Fire | 125 |

| XXI | Softfoot, Softheart | 131 |

| XXII | On the Laramie Trail | 138 |

| XXIII | War to the Knife | 143 |

| XXIV | Message by Bone | 150 |

| XXV | Gathering Fires | 157 |

| XXVI | Softfoot’s Warning | 163 |

| XXVII | The Disaster of Long Trail Ridge | 169 |

| XXVIII | After the Battle | 175 |

| XXIX | Koshinee | 181 |

| XXX | Softfoot’s Resolution | 188 |

| XXXI | Redskin Recreation | 191 |

| XXXII | The Eavesdropper | 196 |

| XXXIII | On the War-Path | 202 |

| XXXIV | The Dawn of Battle | 210 |

| XXXV | “All that was Left of Them” | 215 |

| XXXVI | Blue Eye’s Sanctuary | 220 |

| XXXVII | Something to be Proud of | 228 |

| XXXVIII | Fore-warned, Fore-armed | 234 |

| XXXIX | The Battle of Silver Creek | 241 |

| XL | “Greater Love hath no Man” | 246 |

Softfoot of Silver Creek

SOFTFOOT heard the girl’s stealthy approach through the long grass behind him. Above the laughing voice of the near waterfall, above the prolonged roar of the far-off buffalo herds that crowded the prairie, and above the oily rasping of his knife on the sharpening stone on his knee, his keen hearing knew the sound of her light tread as she crept out from among the pine trees into the sunlit clearing on the bluff.

He did not turn, but only dropped the stone, swept back the straying thick locks of his long, black hair, and then, with his thumb, meditatively tested the razor edge of his blade. Sitting very still, he lifted his dreamy eyes to glance forward across the glistening creek and the billowing prairie to the dark sky beyond the purple mountain peaks that were spanned by a magnificent rainbow.

A moving shadow crossed the brown tan of his fringed leggings; a ripe crimson berry dropped upon his bare arm, and on the turf at his side he saw a very small moccasin of pure white doeskin, encrusted with blue and white beads and edged with ermine.

“Wenonah has wandered far from the lodges to gather her berries,” he said, “and she has no blanket to shelter her if there is rain.”

“Softfoot did not look round,” the girl laughed. “How did he know that Wenonah was near?”

“He did not need to look round,” Softfoot explained. “He heard her walking in the forest. The birds told him that Wenonah was gathering odahmin berries.”

“Softfoot hears all things,” Wenonah responded. “I think he can hear the grass growing. He can hear the white clouds sailing across the sky.”

She propped her heavy parfleche of berries against a mossy boulder and seated herself at her playmate’s side.

“Oh, nushka—look, look!” she cried, now seeing the rainbow. “The sky god has brought out his bow! He is going on the buffalo trail. I like his bow. It is a very strong and beautiful bow—stronger than yours, Softfoot, and even more beautiful.”

“It is beautiful,” Softfoot agreed, gazing at the arched splendour. “Yes, it is beautiful.”

“Tell me, Softfoot, where does the rainbow find all his many colours?” Wenonah asked. “I want very much to know.”

Softfoot thrust his knife into the case at his belt.

“It is that when the wild flowers of the prairie die, they all go up there to live again in the rainbow,” he told her simply.

“If the sky god is not quick, the petzekee will all be gone,” said Wenonah, turning her eyes to the prairie.

On both sides of Silver Creek the plains were black with the moving shaggy monsters, all drifting westward. Great bulls were cropping the grass on the outskirts of the herd; yellow calves ran about their mothers or impatiently butted at them. The young cows and bulls were scattered all over the plain, steadily grazing, always moving in the same direction, sometimes in long, continuous lines, racing quickly down the slopes and climbing laboriously where the ground was steep. In crossing the river they swam in single file, like threaded black beads.

“They will not all be gone,” said Softfoot. “They are countless as the flowers of the prairie. For many days the herds have been crossing to their new feeding-grounds, as you see them now, moving, moving along and eating up the grass as they go. They are as a river that never stops running.”

“Why do not the Pawnees ride out and kill them?” asked Wenonah. “Every day they could kill more and more.”

“Our village is already red with meat,” Softfoot reminded her. “Our women have more buffalo robes than they can clean and dress—more beef and fat than they can make into pemmican. Why should more be killed when our buffalo runners are tired of killing?”

“Our medicine men should make the young braves and boys ride out on the buffalo hunt,” urged Wenonah. “Softfoot has never killed a buffalo.”

“No.” Softfoot shook his head sadly and drew a deep breath.

“I think the petzekee is a very stupid animal,” reflected Wenonah. “It should be easy to kill one. If I were a buffalo, I should not be so stupid as those that are crowded under the cut-bank there. Why does their medicine not tell them that it is too steep for them to climb? Why do they not swim to another place?”

She was watching a vast, writhing, bellowing mass of the hairy giants of the prairie. They had crossed the creek to a steep red wall of cliff which blocked their way. Instead of swimming back into the stream to find a good landing, they pressed all together in a panic bunch, to be trampled or gored to death by their companions, or to sink under their own weight into the silt. Many fell back and were drowned. Carcases could be seen floating down the current towards the cataract of Rising Mist.

“The fishes will eat them,” cried Wenonah. “But I am sorry that so many good buffalo robes should be spoilt.”

“We could do nothing with them,” said Softfoot.

“The Pawnees could sell them to the paleface people,” Wenonah argued. “They buy many robes and buffalo tongues.”

Softfoot shook his head.

“The paleface people would buy them, yes,” he acknowledged. “But what does the paleface give to the Indian in return for the buffalo robes and dried tongues and pemmican? We have our bows and arrows for the hunting. We do not need the white man’s guns, which only cause war. We can make our own clothing, build our own wigwams, and be happy. We have good drink from the streams. We do not need the firewater of the paleface. Why should we kill the buffalo to get things that we do not want—that only do us harm? Our fathers lived in peace; they were happy before the white man came into the land of the redskin. Eagle Speaker has said so, and he is wise.”

Wenonah displayed her two moccasined feet.

“It is from the paleface that we get our beautiful beads, our silk thread, our steel needles,” she stated. “Your knife, Softfoot, was made by the paleface. You would be proud to own a white man’s gun. And do not the Pawnees get from him the tea, the sugar, the pain-killer, and all the pretty and useful things that our braves bring home from Fort Benton in exchange for their furs and pemmican? In all our lodges, we have cooking pots that were made in the land of the paleface. We have too many buffaloes. Our braves should all have guns to kill them.”

As she spoke she bent forward, reached forth her left hand very quickly and seized a large, lustrous blue dragonfly that had alighted upon a flower beside her. She held the insect a prisoner, while with the fingers of her other hand she caught at one of the filmy wings, watching the creature’s struggle to get free.

“Stop,” cried Softfoot. “You are hurting the poor kwone-she. Let it fly away!”

Wenonah swiftly tore the wing from its socket and flung the injured insect into Softfoot’s face. The dragonfly fell into the grass and tried to take flight with awkward, lop-sided jumps.

“You make me very cross,” declared Softfoot angrily. “You are cruel, Wenonah. The beautiful kwone-she was happy drinking honey from the flower. It was doing no harm.”

“Ho, ho, ho!” laughed Wenonah, rising to her feet. “You call me cruel for hurting a useless fly? It is because Softfoot thinks it cruel that he will not go out on the buffalo trail? Poor buffalo! It would hurt so very much to be killed!”

Softfoot had risen also. The girl’s ridicule pained him. But he smiled.

“When Softfoot is no longer a boy he will go to the buffalo hunt,” he told her. “But the animals are his brothers. He loves them. He does not want to take life.”

“No,” retorted Wenonah, standing confronting him with her back towards the boulder, “that is why he is not as the other Pawnee boys, who set their traps and bring home many beaver tails, many ermine furs and fox skins. Softfoot is afraid to kill. When my father, the big chief Three Stars, gave him a good bow and a sheaf of arrows and told him to go hunting in the forest, he came back to the wigwams with empty hands. He had killed nothing.”

Softfoot glanced aside searchingly. He had heard something which seemed to fill him with alarm, coming from the rear of the boulder.

“He did not want to kill the pretty squirrels,” Wenonah went on, “or the rabbits at play among the leaves; the beavers at work in the pools, or the fawns with their soft eyes. He talked to them. He called them all his brothers. Pah! He is as his father before him. He is a coward! And a coward can never be a true Indian. I will tell the Pawnee warriors and squaws that Softfoot is a coward.”

She looked at him with contempt. She did not hear the ominous rattling sound at her feet, like the rustling of dry leaves in the rank grass. Softfoot leapt forward and flung the girl aside out of danger. He had seen the long brown rattlesnake sliding out from beneath the boulder, giving its harsh warning and coiling as it raised its head ready to strike at Wenonah’s bare hand as she stooped to pick up her parfleche of berries. And now as Wenonah turned to rebuke him for so roughly pushing her aside, she saw him draw his knife.

He had crouched, resting both his hands on his thighs. His moccasined feet were not two paces away from the venomous reptile’s brown, uplifted head; and again the crackling noise sounded.

The Indian boy’s knife flashed in the sun. His left hand darted forward and seized the snake in a tight grip of the thin neck behind the repulsive head. He held it pressed against the mossy surface of the boulder, and with one quick, determined slash of his blade he severed the head from the body that coiled itself, like the lash of a whip, around his bare left arm.

The severed head dropped at his feet. He drew back from it, flung the coiled snake from his arm, and then went down on his knees and with his knife dug a hole in the ground into which he thrust the still gaping head, burying it deep and stamping it down with his heel.

When he turned round from his work to pick up the parfleche of berries, Wenonah stood watching him with astonished eyes. But Wenonah was not alone. Beside her was the tall, majestic figure of Three Stars, wearing his red blanket and his medicine bonnet of many eagle plumes, ermine tails, and scalp locks.

Softfoot had known that the chief had come out from his lodge to watch the buffalo herds from the vantage-point of the high bluff; but he was not aware that Three Stars had dismounted and was walking back through the forest. Believing now that the chief must have heard Wenonah’s accusation of cowardice, he bent his head in shame as he moved to go away.

“Softfoot will carry the berries to Wenonah’s teepee,” he said in passing.

But the chief detained him.

“No!” he commanded, signing to his daughter to take the parfleche. “Wenonah will carry her own berries.” He waited, thinking deeply. Then to Softfoot he said: “Three Stars heard Wenonah call Softfoot a coward. He heard the kenabeek’s rattle in the grass. But because he did not kill the kenabeek and save his daughter from its bite, he must lose one of his feathers.”

He drew a wing of his flowing headdress over his arm and with dexterous fingers plucked out one of the white eagle plumes which he smoothed and straightened on the palm of his hand.

“The feather is for Softfoot,” he announced, holding it by the quill, where it was looped with a thong of doeskin bound with red silk threads. “Softfoot will wear it, for my medicine tells me he is not a coward. A coward flies in fear from the deadly rattlesnake; but Softfoot has slain one with his naked hands. He was not afraid.”

Softfoot obeyed the chief’s sign and went nearer to him, and, watched by Wenonah, Three Stars fastened the badge of honour in the front of the boy’s beaded head-band.

MISHE-MOKWA—Great Bear—was the name of the head war-chief who ruled over the tribe of Pawnees encamped under the shadows of the Porcupine Range. His village consisted of two hundred lodges, ranged in a wide circle on the open plain between Silver Creek and Grey Wolf Forest. Each teepee could accommodate a household of eighteen persons. It was a big village. There was need for much buffalo flesh to feed so great a population.

Softfoot had said that the village was red with meat, and that the squaws had more buffalo robes than they could possibly clean and dress. To him, as to most of the young Pawnees who had watched the great loads of meat and hides being brought in by the endless train of pack-horses and dogs after each day’s hunt, it seemed that it would be waste to kill any more.

There were hundreds and hundreds of buffalo tongues hanging up to dry on the scaffolds. Around the wigwams were great red stacks of choice tenderloins, ribs, and back fat, to be preserved and pounded into pemmican. The rolled-up hides, packed shoulder high, stretched in wide, level walls like a stockade round the circle of lodges. There was blood everywhere; on the horses, along the trails, on the clothing and on the hands and arms and faces of the men and women who worked at cutting up a store of meat that seemed too abundant ever to be exhausted.

But Great Bear and his mystery men knew well that the buffalo herds would soon have wandered upon distant trails beyond the Big Horn Mountains. They thought of the coming winter. They were not yet satisfied, and were already planning another hunt.

Softfoot saw the medicine chiefs seated in council round their mosquito smudge in front of Mishe-mokwa’s lodge, as he ran across the grassy plain to where the boys and girls were at play. He ran, because he had lingered at the kennel in the rear of his home teepee to give food to the wolf cubs, the kit fox, and the baby owl which he kept as pets, and he was late. He carried his bow and a quiver of new, carefully chosen arrows. For he was pitted against Weasel Moccasin in a final competition of skill in quick shooting, for on that day various contests were to be decided.

All the Pawnee boys of his own age in Great Bear’s village had dropped out of the contest, and he and Weasel Moccasin remained to decide possession of the prize—an eagle plume, to be worn for all time as a badge of skill.

As Softfoot approached the eager crowd, Weasel Moccasin saw the conspicuous white feather fluttering from his head-band, and he frowned.

“Look!” he exclaimed. “Softfoot is wearing the feather! He has not yet earned it; nor have I failed to earn it. Why should this be allowed? I will make him put it away!”

When Softfoot came abreast of him, he flung out his hand to snatch at the feather. But Softfoot’s strong left arm came like a bar of iron in the way. Weasel Moccasin staggered back, and Wenonah stepped in front of him, while the youths clamoured to know where the plume had come from.

“It is but the tail feather of a wa-wa goose that he has been chasing,” declared Red Crow, making a grab at Softfoot’s head. But Wenonah thrust him aside and turned to face the discontented throng.

“Are you all blind that you do not see it is a true eagle plume that Softfoot is wearing?” she cried. “If you would know how he earned it, go and talk to the chief Three Stars. Very soon there will be a second feather by its side. My medicine tells me that Softfoot will win in this arrow game.”

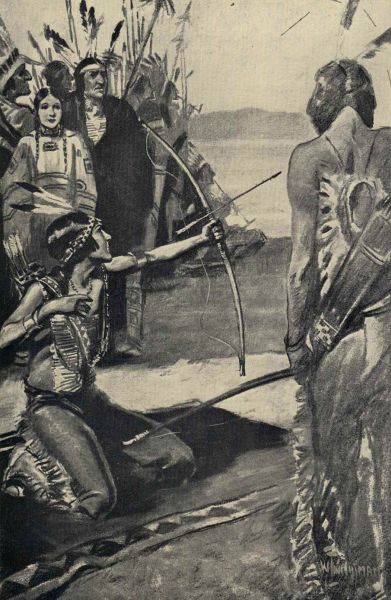

Weasel Moccasin had thrown off his buckskins and taken up his bow. There was a sheaf of arrows strapped across his naked brown back. The arrowheads were above the level of his right shoulder, within quick reach of his hand. The contest between him and Softfoot was to prove which of them could shoot the greater number of arrows from the bowstring while the first was still in the air.

Two important warriors—Long Hair and Talks-with-the-Buffalo—stood near, to act as umpires. There was great excitement among the onlookers, who were watching the two boys with appraising eyes, judging them by the movements of their clean-muscled bodies and hard-knit limbs. It was such a match as the Indians delighted to watch.

Weasel Moccasin was to shoot first. He took his stand with his left foot well forward, his right leg slightly bent at the knee, and his lithe brown body swaying back as he gripped his bow and held his right hand poised above his muscular shoulder ready to pull out an arrow.

When Long Hair gave the signal, he nipped the first arrow from his quiver, fixed it on the bowstring and, aiming straight upward, gave a firm strong pull that drew the arrow point almost to his hand. The released shaft flashed upward into the blue air and the string trembled still when a second arrow took its place. With sure and unfaltering regularity the boy’s deft fingers went to and fro between the string and the quiver; and the arrows followed in quick succession. The first one had not turned in its vertical flight when two were mounting behind it.

As the first curved over for the fall, a fourth left the bow, and as the former sped downward, a fifth was drawn, and the bow again twanged. There were now five arrows in the air; but as Weasel Moccasin reached for a sixth, the first one plunged its point into the turf. A great shout burst from the watching crowd.

It was then Softfoot’s turn. Instead of standing, he went down on one knee, bunching himself together, and some of the warriors clapped their hands. His first arrow soared as high, but not so directly upward as his opponent’s. He gave it a curving flight which would take it farther away in its descent. His second and third flew on the same course; his fourth and fifth went straight upward, and his sixth was barely notched on the bowstring when the first alighted. The competitors were equal, although Softfoot gained on points. But there was a second turn for each. This time Weasel Moccasin imitated Softfoot by kneeling, and he finished, just as Softfoot had done, with his sixth arrow in the grip, but the bow not drawn.

It seemed impossible that so many as six arrows could be in flight all at the same time. But in his second round Softfoot gave extra impetus to his leading arrow, and with such effect that he succeeded in getting his sixth away an instant before the first one touched the ground. He was therefore acclaimed the victor and the winner of the coveted feather.

The excitement had not subsided when Mishe-mokwa and his mounted medicine chiefs rode across the plain to make the awards in the various games of skill.

Great Bear announced that he had decided to hold a buffalo hunt on the following morning and that the six boys who had been foremost in the shooting match were to join with their elders and ride out to take part in the surround, choosing their own buffalo ponies and taking marked arrows.

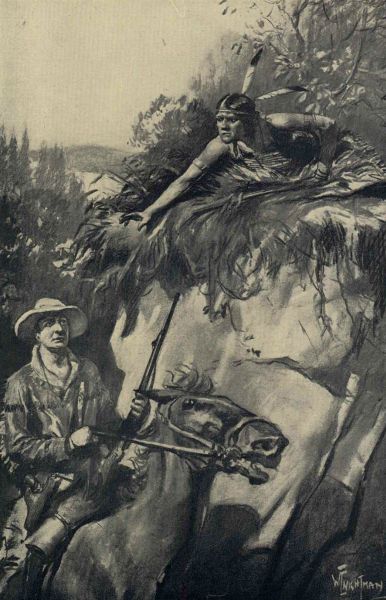

“It was then Softfoot’s turn. Instead of standing, he went down on one knee, bunching himself together.”

AT sundown, when Softfoot strode towards his smoke-grimed teepee on the north side of the village, Morning Bird, his mother, stood by the open door-flap cleaning her hands with a bunch of clover grass. She had been on her knees the whole day scraping buffalo robes, and she was very weary. But she smiled in approval at sight of the two eagle plumes in Softfoot’s ruffled hair.

“Softfoot’s medicine has been good to him,” she said, following him into the twilight of the lodge. “He has made a beginning. Morning Bird is happy in her son’s success.”

He hung up his bow and quiver against one of the poles and seated himself on a roll of blankets away from the smoke and warmth of the newly kindled fire. Morning Bird brought him a large steak of cooked buffalo meat sprinkled over with dried bull-berries.

“Eat,” she said, “and we will talk.”

“It would be better if you would sleep,” he advised her.

She stood facing him.

“Softfoot is no longer a child,” she began. “It is time he should do more than waste his days in the games of children. He must try to be a man. He has skill in the arrow game, in the stick-and-wheel game. He can ride, he can swim, and run. He knows the secrets of the woods. But all this is of no value to the Pawnees. It is like the beads we sew on our moccasins to please the eye. The beads do not keep our feet warm or give us food. The warriors and braves are saying that Softfoot will never be a man fit to go on the war-path, because he is afraid to kill.”

“It is true,” Softfoot admitted. “It is true that he does not want to take life. He is a coward, like his father.”

Morning Bird’s dark eyes flashed.

“Fast Buffalo Horse was not a coward,” she denied.

“But the Pawnees say that I am the son of a coward who was afraid to go on the war-trail,” Softfoot rejoined.

“Fast Buffalo Horse did not refuse to fight the Sioux or the Crees, who are our enemies,” Morning Bird declared. “He was a great war-chief who took many scalps in many battles. But he would not go on the war-path when there was no quarrel. He was wise; he was not afraid when he would not fight the Mandans, who were our friends. If the Pawnees had listened to him there would have been peace. Our tribe had plenty of buffalo meat. They were rich in robes and horses. They only wanted to take more and more scalps to hang on their crowded lodge poles.”

“A scalp war is not a true war,” Softfoot agreed. “Eagle Speaker has said that the Mandans were weak. They could not defend themselves. They were poor. The buffalo had deserted them.”

“They owned nothing that the Pawnees wanted,” pursued Morning Bird. “They were not our enemies. They had smoked tobacco with the Pawnees.”

“If Fast Buffalo Horse were a coward because he loved peace,” reflected Softfoot, “then I, too, am a coward. I do not want to take life when there is no quarrel. I would kill the rattlesnake, the koshinee wolf, the lynx, and the mountain lion, but I would not kill the sing-bird that fills the forest with music, or the butterfly that drinks honey from the flowers.”

“Yet there is need to kill,” argued his mother. “If you are to be a brave, a warrior, you must go on the war-path against the enemies of your people. You must not be afraid to do battle in a just cause, or to kill when there is need for food and clothing. If the Pawnee boys were all like you, we should have no beaver tails to eat, no buffalo meat; no warm soft fox skins to wear or buffalo robes to cover our wigwams.”

Softfoot stood up. He was nearly as tall as Morning Bird.

“To-morrow I go on the buffalo hunt with the men,” he told her proudly. “Mishe-mokwa has said so.”

Morning Bird clapped her hand to her mouth in astonishment. She walked to and fro in the wide space of the wigwam.

“Softfoot will be afraid,” she declared, after a long silence. “He will ride away from the buffalo bulls. The Pawnees will laugh at him. They will call him a coward.” Then she halted in front of him. “You cannot refuse to go on this hunt,” she said very seriously. “You must pray to the Great Spirit to give you strength and courage. You must burn sweet-grass and sweet-pine to purify yourself, comb your hair, and paint your face with vermilion. Morning Bird will now go out to the corral and rope the best petzekee pony. She will talk to the pony and tell him to be swift and not fall.”

“It will be Snow-white,” he told her. “Snow-white is the best buffalo pony of all that ever were foaled.”

The sounds of dancing and beating drums on the plain outside died down into a profound silence as the shadows deepened into darkness. Softfoot slept heavily on his couch of bear skins near the closed entrance of the teepee. But even in his sleep his mind dwelt upon the coming buffalo hunt and its hidden dangers. In the middle of the night he awoke to find a thin beam of moonlight streaming in upon him through a gap in the door-flap of deerskin.

He raised himself on an elbow and drew the flap aside. From where he lay he could see the indigo peaks of the Big Horn Mountains against the moonlit sky, and, nearer, the dark prairie was cut by the glistening sheen of Silver Creek. From far away there came to him the long-drawn plaintive howl of a wolf and the subdued bellow of a buffalo. He shivered under the cold of the night air.

“The warriors say that I am afraid,” he meditated. “But I will not be afraid. Eagle Speaker’s gift will give me courage. I will carry it with me always. It will shield me from harm. It will give me strength and bravery. I shall kill many buffaloes. I will go on the war-path. Eagle Speaker knows the secret of this medicine gift. He told Softfoot to trust in its power to make him brave. It came to me in my sleep that I must do this thing.”

He rose very silently from his bear skins, and in the black darkness crept with cautious tread across the earthen floor to the place where he had hung his sacred bundle. Very reverently he took the bundle down and thrust his hand into its wrappings of soft doeskin until his fingers closed upon the thing he sought.

“It is very strange that it should have such power,” he whispered in superstitious awe. “What can be its secret?”

ALMOST before the stars grew dim and the eastern sky was beginning to show light above the pine trees, Fire Steel, the camp crier, was out on the plain beating his drum to awaken the Pawnees and tell them to make ready for the buffalo hunt.

From the surrounding lodges, men and youths swarmed out, like bees from their hives, and ran through the woodland glades down to the creek for their morning swim; and many squaws carried or dragged their children, to bathe them in the quiet pools below the willows.

Softfoot was one of the first to return from the creek. He had dived from a high rock above the rapids and allowed himself to be carried by the icy current over the curving ledge of smooth, green water to plunge like an arrow down into the turbulent, swirling cauldron of foam and spray at the foot of the cascade.

There in the whirling pool among the startled salmon he had splashed and rolled for some joyous minutes before climbing out to shake himself and throw his sheet of tanned elkskin over his wet shoulders and run home through the dim forest trail, where even the birds were not awakened by the soft pad of his moccasined feet.

Suddenly he stopped and turned back a few paces. In the moist ground at the side of a narrow stream he had seen the impression of hoofs. They were not the hoofs of an Indian pony, for they showed the clear marks of forged iron shoes, such as were not used by the Pawnees. They pointed in the direction of Great Bear’s village.

“Why should a paleface be riding through Grey Wolf Forest?” he asked himself as he ran on. “He is not a stranger. He knows his way to our lodges.”

When he reached the camp, blue wisps of fire-smoke were rising into the cool air from the smoke-vents of the teepees. There was busy movement everywhere. The whole village was awake while yet the grass was wet with dew and the sun’s light had not touched the mountain-tops.

Moving forms, clad in bright colours, passed to and fro. Tied near each wigwam there were two or three horses; dogs were barking and people were singing under the painted skin-covers of their lodges.

Everybody was glad that there was to be yet another buffalo hunt. The pack-horses and draught dogs had been kept in camp, close to the teepees. The travois frames were emptied ready to carry in new loads; nothing had been stowed away since the harvest of the last chase had been brought in from the prairie; but the women were sharpening their knives to cut up the expected meat, and they were coiling their ropes of shaganappy with which to pack the red loads and the heavy hides.

The men were looking over their weapons of the chase to see that the bowstrings were right, the arrows straight and strong, with the points not blunted; while those who had guns were cleaning them and providing themselves with powder, bullets and percussion caps.

The boys who were now to make their first hunt were excited. They had imitated their experienced elders in going through the various ceremonies of preparation, praying for good luck, purifying themselves by breathing the scented fumes of burning sweet-grass, combing their long hair and painting their faces.

Morning Bird was very anxious that her son should look his best on so important an occasion. She combed and braided his hair and painted the parting with vermilion. With practised art she had mixed many colours from the juices of herbs and berries, yellow and blue clay and charcoal, and she painted his face and body with great care in lines and curves and rings.

For the hunt he wore no clothing but a breech-clout and his moccasins, and armlets and a necklace of bears’ claws, porcupine quills and brilliant beads.

“What is this?” Morning Bird asked, taking in her fingers a small bag of delicate white ermine skin that hung from his necklace.

“It is my sacred medicine,” he answered her, covering it with his hand. “It came to me in my sleep. You must not see it.”

Enclosed in the ermine skin was the thing that he had taken from his mystery bundle during the night—the thing which was to give him strength and bravery and shield him from harm.

Morning Bird did not question him further but accompanied him out of the lodge to where his buffalo pony, Snow-white, waited. It was not shod and had never been saddled or bridled. He led it away by its long trail-rope of rawhide, one end of which was knotted about the animal’s lower jaw, while the other end dragged loose along the ground, where it might be seized if the rider should be thrown and not too much hurt to snatch at it.

“Ha!” cried Weasel Moccasin as he joined the group of favoured boys who were now for the first time to do the serious work of men in the buffalo surround. “My medicine tells me that to-day I shall have great luck. Softfoot shall not get the better of me this time. I shall pick out the finest bulls in the herd and bring many of them to the ground.”

“It may be that none of us will get near enough to kill,” said Softfoot, caressing his pony’s muzzle. “Mishe-mokwa has said that we are not to put ourselves in danger; but only to watch the men, and learn from them how to manage our ponies. It is bad hunting if our ponies are hurt.”

“That is true,” nodded Red Crow, “and I for one will keep out of danger. I will pick out a swift cow or a bull calf and drive it well away from the herd, so that I may not be too close to the ferocious bulls.”

Before they mounted they were told to lay their quivers on the ground. Heavy Head, a veteran buffalo runner, was to examine their arrows and see that they were well feathered, well pointed and duly marked.

Weasel Moccasin and Softfoot had placed their quivers side by side on the grass when Little Antelope, one of the younger boys, saw the chief coming out of his council lodge, attended by many warriors and mystery men. With the chief walked a tall, bearded stranger, dressed in buckskins and wearing a wide, felt hat.

“It is a white man!” exclaimed Little Antelope in surprise. “Come, let us go and look at him! Never before have I seen a paleface. See, he has a gun! He is showing it to Mishe-mokwa. He is perhaps coming on the buffalo hunt.”

“His gun is broken,” said Softfoot, who knew nothing of the mechanism of a breech-loading rifle. “And he is putting the bullets in at the wrong end!”

“Where does he come from—this white man?” questioned Red Crow. “I think he is an enemy.”

“He rode into our camp when the Pawnees were still asleep,” explained Softfoot. “He is alone. He would not come alone if he were an enemy. That is his horse—Long Hair is leading it. It is a beautiful horse—taller than any of ours. I want to see how he mounts. Aye! look! look!”

The stranger had raised a spurred foot to his stirrup and was quickly seated in his saddle with the bridle in his hand and his gun in the crook of his arm. To the Indian boys he looked very tall and splendid with his broad shoulders and upright figure. Even from a distance they could see that his eyes were not so dark as the eyes of the Pawnees, and, with quick recognition of this peculiarity, Softfoot said:

“Let us name him Blue Eye, for his eyes are like the moonlit sky.”

Great Bear, Three Stars, Talks-with-the-Buffalo, and other warriors, had also mounted. They all carried muzzle-loading guns, and wore their bright-coloured blankets and medicine bonnets. The chief and Blue Eye rode side by side, talking like friends. The others formed in Indian file, following across the plain, each leading a second pony that would be used in the hunt. The six boys ran back, snatched up their bows and quivers, and leapt excitedly to their ponies’ backs, taking places where they could find them in the long procession of riders.

As they rode out from the wide circle of lodges to enter the prairie trail, they turned and waved their hands to the watching crowds of women and children. Then they strung their bows to be ready for action. It was not until afterwards, when he was in the midst of the buffaloes, that Softfoot discovered that the arrows in his quiver were not his own, that they bore Weasel Moccasin’s marks. They had been changed. But by whom? And why?

The warriors rode slowly through the woodland, and when they came into the open some turned to the eastward and others to the west, forming two separate companies along the ridge of the hill to encircle the hunting-ground.

By this time the sun was rising, flooding the prairie with yellow light. The grass sparkled with dew, and thin shreds of grey mist drifted and melted. The sweet, wild whistle of the meadow lark rang out from the knolls, and the skylark and the white-winged blackbird filled the air with their rich notes. Now and then a jack-rabbit or a kit fox was startled from its bed in the grama grass, or a family of antelopes, alarmed by the horsemen, would race to the safety of the hill-tops.

Through the rising mist the brown, hairy shapes of many buffaloes could be seen scattered over the level land like cattle in a pasture. The great shaggy bulls were cropping the grass on the outskirts of the herd, as if guarding the cows and calves that were still at rest, unconscious of the dark line that was slowly creeping round them.

Neither bulls nor cows took any notice of the prowling scavenger wolves that were the usual attendants upon every buffalo herd, following them in their migrations to pick off the weak or injured stragglers or to feast upon the stripped carcases discarded by the Indians. But as the tightening ring of horsemen began to close in, the alert sentinel bulls lifted their shaggy heads, sniffed with suspicion at the tainted air, caught sight of the mysterious enemy and sounded the alarm in a long-drawn bellow.

The younger bulls and the cows with their yellow calves began to rush about in aimless panic, gathering at first in detached groups and then crowding together in a compact mass until the veteran bulls took leadership and started them off in a headlong stampede with heads lowered and tails lifted high. Their roaring was like the roll of thunder. The earth trembled under the heavy tread of their hoofs.

The Pawnees rode round and round in their unbroken circle. Three Stars, who was the captain of the hunt, saw that he could not successfully deal with so large a herd, and he allowed many to escape before he gave the signal which released all restraint.

Yelling their wild hunting cries, the Indians dashed forward to the assault, each intent upon being the first to come within striking range of their huge victims. It was a desperately dangerous game. No hunting has ever been so perilous and exciting; for the buffalo is a terrible antagonist, swift of foot, resistless in attack, vicious in defence, and backed by a strength which could only be avoided by that cunning which has always given man the mastery over the brute.

SOFTFOOT remembered the chief’s caution to the boys against running into danger. His medicine told him not to be reckless, and he held back, watching for his chance.

The Pawnee bowmen were exceedingly clever in opening their attack. As their weapons were silent, they could kill one after another of the buffaloes without causing a general alarm. Their plan was to head off the stampeding herd and keep it compact and well surrounded.

Long Hair had singled out the leading bull, the king of the herd. He galloped nearer and nearer and came abreast of the onward plunging monster. Then he drew his bow, aiming at the exposed side behind the shoulder. When the buffalo stumbled and rolled over, the two or three bulls closely following stopped and sniffed at it stupidly, until one of them in its turn assumed the post of leader and the stampede was continued.

Long Hair and his companions now gave chase and crossed in front of the leading bulls, turning them back upon the crowded mass while the hunters rode round and round. But the great animals, already mad with fear, did not long remain close together. Soon all was confusion, horses and buffaloes racing side by side, turning up the dust with their clattering hoofs and sending forth a deafening noise of bellowing and coughing to mingle with the shrill whoops and yells of the Indians. Above the rough brown backs and woolly humps of the buffaloes, the naked shoulders and flashing arms of the men showed red and glistening as they drew their arrows to the head and drove them into the flesh.

It was not easy for Softfoot to understand how the Pawnees, riding in the thick of the furiously battling giants, could escape injury from the tossing horns and the enormously powerful frames of the angry animals they were attacking. But the ponies were watchful, nimble, sure-footed, and quick to avoid the frontal charges of the angry beasts, while at the same time dodging the badger-holes in the ground that offered traps for unwary feet.

“Why do we wait?” cried Weasel Moccasin, impatient to join in the fray.

He was riding a borrowed piebald pony that had not been too willing to obey the guidance of a strange rider. But now that the conflict was at its height, the piebald suddenly changed its demeanour. It reared up under the restraint of the taut trail-rope, pranced sideways with arched neck and twitching ears, and then, getting the rawhide bit firmly in its teeth, sprang out into the fray, plunging among the buffaloes as madly as any others of the trained runners.

Softfoot saw Weasel Moccasin being carried helplessly into the turbulent sea of shaggy-backed, gleaming-eyed monsters. He shouted to him to turn back. Instead of pulling the pony round, Weasel Moccasin began to belabour it with his quirt, which made matters worse. The pony careered onward, forcing its way into the writhing throng. Then its rider dropped his trail-rope and began to work desperately with his bow and arrows, wounding a buffalo each time, but disabling none. He was too reckless to take aim, and his silent shafts only made the bewildered animals more furious.

“It is now time for my medicine to help me,” muttered Softfoot, touching the ermine bag that hung from his necklace. “Weasel Moccasin is in great danger. I must help him or he will be killed!”

He urged Snow-white forward into the confused conflict, entering by the narrow gap that his companion had made. As he started he fixed an arrow on his bowstring, and it was then that he discovered that the arrows were not his own; but he continued shooting, always aiming at a vital part, always pulling his bow strongly.

A young bull ran into his path and stopped, barring his way. Softfoot passed his bow over his right arm, and gripped the pony between his knees. She lifted him with a splendid leap, clearing the bull and alighting easily on the farther side. He saw Weasel Moccasin close in advance of him now, hard-pressed by many hairy giants whose humps were much higher than his pony’s ears.

A monstrous long-horned bull stood at bay in front of him. Its big, bloodshot eyes glared threateningly; there was foam about its jaws and the breath came noisily from its fiery, trembling nostrils. The swelling muscles about its immense shoulders were tensed ready for a desperate forward rush at the piebald pony. There was no escape for Weasel Moccasin.

“Jump!” cried Softfoot. “Jump!”

At this moment of peril some of the warriors had opened fire with their guns. There was a sudden startled movement among the buffaloes. The great bull swerved to get at the piebald’s flank. Its own broad palpitating side was exposed for an instant. In that instant Softfoot pulled his bowstring and shot an arrow deep into the brown expanse behind the animal’s shoulder.

“Jump!” he called again.

But even though fatally wounded, the bull had already made a fierce battering charge at the piebald, flinging the pony with its rider high into the air, and then staggering backward.

Weasel Moccasin turned a somersault and dropped with a dull thud upon the buffalo just as the mighty animal was rolling over. He fell on his back, partly on the bull’s soft flank and partly on its deep, woolly mane. But his head struck against the hard bone of its bent elbow, and he was stunned. He did not move.

Softfoot believed that he was not seriously hurt. He forced his way up to him, leant over, and seizing one of his hands, drew him upward until he got an arm round him and could hoist him securely across Snow-white’s withers and hold him there as he glanced anxiously round for a means of escape.

But the danger was not yet over. The warriors were pressing the buffaloes closer behind him, firing at them. Softfoot was crushed helplessly in the frantic, jostling crowd, and his hands were not free to use his bow.

He had difficulty in keeping his seat. Had he been thrown, he would quickly have been trampled to death. Snow-white was but a feeble animal to battle her way out from such a dense, grinding crush. Yet she kept her feet and avoided the tossing heads and menacing horns.

The pressure seemed to be getting worse. Softfoot was beginning to lose hope when suddenly the cows in front of him scattered in many directions, driven from side to side by a rider who dashed into their midst, firing shot after shot with such astonishing speed that even in his situation of peril Softfoot wondered how the man could have time to reload his gun after each discharge.

He looked forward over the sea of tossing humps and saw the man riding directly towards him through an open lane in the wildly scattering herd. He was not a Pawnee; nor was his tall, rangy mount an Indian buffalo pony. Softfoot quickly recognized him as the paleface stranger whom he had named Blue Eye.

With prodding spur and coaxing words, Blue Eye forced his great horse forward into the tight throng. He had slung his rifle over the pommel of his stock saddle and was firing now with his revolver, taking quick, sure aim at each buffalo that came in his way. His trained mount swerved or leapt to avoid the stumbling, panic-stricken cows and madly careering bulls. And at last he reached Softfoot’s side.

“Is your friend badly hurt?” he inquired, speaking in the Pawnee tongue. “I see his pony is done for. I saw what happened. I watched you riding after him. Wait! Let me help you.”

He dismounted and lifted Weasel Moccasin to get him astride in a comfortable position with his back resting against Softfoot’s chest. Then he turned and looked down at the injured pony, which he saw was very far gone. Blue Eye mercifully fired a bullet into the white star on its forehead.

“A good prairie pony lost by bad management,” he said. “You are both too young to be allowed out on a buffalo hunt,” he added, and seizing Snow-white’s halter rope, he mounted his own animal and slowly led the way out to open ground. Here, clear of the buffaloes, he again dismounted and gave Weasel Moccasin a drink from his water bottle.

“He is not dead,” said Softfoot. “But I think his head is very sore.”

“Likely,” nodded Blue Eye, speaking now in the white man’s tongue, which Softfoot did not understand. “Concussion of the brain, I guess. But you stopped that big bull from trampling him. If he’d jumped, he wouldn’t have been hurt.”

As he got again into his saddle, he glanced at the two feathers in Softfoot’s head-band. They told him that the boy had won distinction in his tribe, while the injured boy, as he noticed, wore no such badges.

“What made him ride into the middle of the stampeding herd?” he asked. “He ought to have known better.”

“It was his pony’s fault,” Softfoot explained. “We were told to keep out of danger. But his pony carried him in. He could not stop her. He could not turn her back.”

“Then why in thunder did you follow him?” questioned Blue Eye. “Did you want to get killed? What made you go after him as you did? Weren’t you afraid?”

“I was afraid,” admitted Softfoot. “I was like the grass in the wind. But I wanted to do the thing I was afraid of doing. That is why I followed Weasel Moccasin. He was in danger.”

The blue eyes of the bearded frontiersman were fixed upon Softfoot with something of admiration in their expression. They noted the Pawnee boy’s regular features under the paint that was already smeared with prairie dust and perspiration. They noted the well-developed muscles of his arms and thighs, and the healthy smoothness of his bronzed skin. They noted also that the boy’s hand went more than once to the little white bag hanging from his necklace.

“You wanted to do the thing you were afraid of doing?” Blue Eye repeated thoughtfully to himself. “Why, that’s just about as good a definition of courage as ever I’ve heard.” Aloud, he said: “What is your name, kid? I want to remember you by it.”

“It is Softfoot,” he was told.

“Is that your medicine that you’re so careful of?” The white man smiled when Softfoot again drew his necklet away from Weasel Moccasin’s head.

“It is my medicine,” answered Softfoot. “And you too, Blue Eye—you also are wearing a sacred medicine.”

The frontiersman’s flannel shirt was open at the throat. Round his sun-tanned neck was a fine chain of gold and glistening beads.

The thought of the necklace so accidentally revealed brought a curious flash to the white man’s blue eyes.

THE Pawnee women and children were out on the prairie with their pack-horses and travois dogs. There was not a live bison to be seen on the wide expanse of sandy hillocks and far-stretching levels of grass and blossoming flowers. The stampeding herd had disappeared beyond the hills to more peaceful grazing grounds.

But the plain was dotted over with carcases which the Indian men were flaying; and round each was a group of industrious squaws, girls and boys, busy at the work of securing the hides and cutting up the meat.

Three Stars and his attendant warriors had ridden the round of the kill superintending the gathering of the marked arrows that would show which of the hunters, whether man or boy, had been most successful in the chase. If more than one arrow was found in any particular bull or cow, the medicine chief’s word decided which of them had been fatal.

When the arrows had been collected and laid out for their various owners to claim according to the totem mark on the smooth shaft, those that had been used by the six tenderfoot boys were kept apart, so that he who had done better than his companions should be decorated with an eagle’s plume. Every one in Great Bear’s circle of lodges was interested in the prowess of the youths of the tribe.

Softfoot, now wearing his fringed buckskins, and followed by his tame wolf-cub, strode towards the warriors to claim his arrows. He halted on the outskirts of the crowd.

“It is strange,” Three Stars was saying, “but I have counted seven great buffaloes that were killed by the well-aimed arrows of Weasel Moccasin before he was hurt. Each one of them was buried deep in the heart. Mosquito Child killed an old stub-horned bull. Little Antelope brought down two cows. Red Crow killed two good bull calves. Prairie Owl fell and broke his bow. These have done well. But not one bison have I found killed by Softfoot’s arrows.”

Softfoot had hold of his wolf-cub’s ear, and his fingers tightened their hold in his astonishment at this verdict.

“Yet Softfoot was in the hunt,” pursued Three Stars. “He came home with an empty quiver. All his arrows left his bowstring; but not one of them struck a vital part. Many of them fell out of the wounds that gave hurt, but did not kill. That is not good hunting. My medicine tells me that Softfoot has failed as a buffalo hunter. His arm is weak. Let him spend his days among the wigwams, making moccasins, cutting wood, carrying water, milking the cows, and playing as a child among children.”

Softfoot made a step forward, but drew back and stood silently listening.

“Yet it was Softfoot who won in the arrow game,” Long Hair reminded the chief. “He had six arrows in the air. Weasel Moccasin lost his pony in the chase. It was gored by a savage bull.”

“Softfoot carried Weasel Moccasin out from the surround,” added Talks-with-the-Buffalo.

“No,” Three Stars assured him. “It was our paleface friend over there who brought them out, or they would both have been killed under the stampeding hoofs. Softfoot did nothing to gain praise. The buffalo hunt is not for him.”

“Listen!” urged Big Elk. “The great bull that tossed Weasel Moccasin and his pony was killed with an arrow—not by the white man’s bullet. Weasel Moccasin could not have shot that arrow after his head was hurt. A bull with an arrow in its heart could not have tossed a pony and its rider high in the air.”

Three Stars shook his head in dissent.

“The great bull was killed by Weasel Moccasin, whose marked arrow I myself found buried in its heart,” he said decisively. “My spirit is heavy because Softfoot has failed. But in this matter we must be just. The marked arrows have told their own story.”

His daughter Wenonah caught a fold of the chief’s blanket. She had seen Softfoot join the throng with his vicious-looking wolf-dog.

“Let Softfoot talk,” she interposed. “His tongue is not forked, even if his arm is weak. He will speak the truth. Let him talk.”

Three Stars frowned as he looked down at the girl’s shabby overall that was smeared with wet blood and buffalo fat. All the morning she had been occupied in hanging up great slabs of freshly cut meat on the drying scaffolds. Her hands were red with buffalo blood. She drew apart from the warriors now and went towards the black-bearded frontiersman who stood near with an elbow resting on his saddle. He removed his pipe from his mouth and smiled at her as she paused to look at the shining cartridges in his belt and at the guns in their holsters on his hips.

“Is this boy Softfoot a good Indian?” he asked her idly.

“The Pawnees are all good Indians,” she answered him proudly.

“I see he wears two feathers,” Blue Eye nodded. “How did he gain them?”

“One for his skill in the arrow game,” Wenonah told him, “and one because he caught a kenabeek in his hand and cut off its head when it would have bitten me.”

“Then he is brave,” nodded Blue Eye, “and you naturally stick up for him since he saved you from that rattlesnake?”

Wenonah shook her head in doubt.

“He was weak in the buffalo hunt,” she said. “I think he was afraid. The Pawnees say that his father, Fast Buffalo Horse, was a coward, and that Softfoot is like his father. But Softfoot is a good Indian. He is very wise.”

The blue-eyed frontiersman looked at her curiously.

“Fast Buffalo Horse was a very great warrior,” he declared. “He was one of the bravest men, red or white, that I have ever known. I am glad that Softfoot is his son. Yes, I am sure he is a good Indian.”

He knocked the ash from his pipe on the heel of his spurred boot, and was preparing to mount when he heard the medicine chief again speaking.

“Softfoot knows his own arrows by their marks,” said Three Stars. “Let him take them away.”

Softfoot, still followed by his wolf-cub, stepped forward and looked upon the separate bundles of arrows that lay on the grass. He was perplexed, but at length he collected and counted those that had been used in the chase by Weasel Moccasin.

“These are mine,” he announced, gathering them under his arm. Then he glanced at others bearing Weasel Moccasin’s own mark. He knew that these others were the arrows that he had himself taken one by one from his quiver and used in the buffalo hunt. He saw that the credit of having killed as many as seven buffaloes was now going to Weasel Moccasin, instead of to himself. Had Weasel Moccasin been present here he would have demanded an explanation. But Weasel Moccasin was now lying unconscious in his teepee. Softfoot made no protest, but quietly carried his inglorious arrows away.

The man whom he had called Blue Eye followed him, leading his horse by its bridle rein.

“I heard what the warriors were saying about you, Softfoot,” he began as he overtook him. “Why do you not tell them that it was you who killed the great bull—who brought six others to the ground?”

Softfoot looked very straight into the man’s blue eyes.

“It is because I did not kill them with my own arrows,” he explained. “It is because while he is not here to listen to me I will not say that I think it was Weasel Moccasin who changed our arrows before we started. When he is well and can remember why he changed them, he will tell the truth.”

“Come with me and we will talk to Mishe-mokwa about this thing,” Blue Eye advised. “Mishe-mokwa will straighten it out.”

“No,” Softfoot protested. “I do not want the warriors to know that Weasel Moccasin did badly. Weasel Moccasin is my friend. I will not speak a word against my friend.”

Blue Eye smiled and held out his hand. He was leaving Great Bear’s camp.

“Softfoot,” he said in his own tongue, “I admire your loyalty. I’ve had proof of your pluck. When I want the help of a good scout whose honour I can trust, whose bravery I can depend on, I guess I just know where to find him.”

Softfoot watched him mounting to his saddle, saw him ride away in the direction of the lodges, and wondered, with a curious, expectant yearning, when and in what circumstances he might possibly meet him again. For his medicine told him that he and Blue Eye were destined to tread the same trail.

SOFTFOOT had gone through many of the contests and exercises imposed by custom upon the Indian boy in order to test his ability and prove his physical fitness to endure hardship and live by his unaided wits.

He was naturally healthy, pure-blooded and perfect in constitution. His inborn senses were sharp; but his faculties of eyesight, hearing, smell, touch, and memory were made additionally acute by practice in the scoutcraft and woodcraft which were the essential parts of the redskin’s education.

He was hardly more than an infant when he learnt to ride, to swim, to wrestle, and to follow a trail; and as he grew in strength he gained skill in the use of his limbs in foot-races, jumping contests, riding, scouting, and games in which the lariat and the bow and arrow were necessary implements.

He had no knowledge of the great world of civilization. He was a savage, living in savage surroundings. His books were the picture-writings on the skin-covers of the tribal wigwams; his limited language was helped by the use of signs. He could communicate with a stranger without uttering a word.

Living an outdoor life close to nature, he had no need for what we call scholarship. But he was not ignorant. His wits were sharpened by conflict with the wits of the beasts and birds. Constantly watching the animals in their native haunts and trying to learn how they would act in particular circumstances, he knew their habits better than he knew anything else, and so became an expert naturalist.

It was his work in following on the trail of the wild creatures he pursued that made him so astonishingly alert as a tracker, so clever in taking cover and hiding his own tracks, so quick in noticing signs and finding his way unerringly through the uncharted forest and across the pathless prairie.

When Softfoot was still a young boy, he was guilty of an act of disobedience. It was in the season of leaf-falling. He was told by Morning Bird to go out on the prairie with the squaws and their pack-horses to gather buffalo chips for fuel; but he escaped from the task and wandered into the forest glades to play with a family of kit foxes. Disobedience was as grave an offence as telling a lie. His punishment was severe, but it was not an unusual one, and Softfoot only regarded it as a glorious opportunity for the enjoyment of his full liberty.

He was taken out at night to the prairie and there stripped of all clothing—stripped of everything but his knife—and told to go away and fend for himself, alone and unhelped, until someone should come and find him. Naked, and with no weapon but his knife, he was abandoned to his own resources, forbidden to return to the lodges!

Two or three weeks passed. Morning Bird, becoming very anxious lest some misfortune had happened to him, had a search party of young scouts sent out to look for him beyond the prairie. The scouts were not surprised when they discovered Softfoot living in a comfortable wicky-up teepee on one of the distant reaches of Silver Creek. He was wearing rough doeskin breeches and moccasins, eating cooked food, while he pointed the shafts of his newly made arrows in front of his camp-fire.

No one had been near him in the interval. He had done everything for himself, having nothing to start with but his knife, his knowledge of woodcraft, and his resourceful skill as a scout who was compelled by necessity to depend upon his own ingenuity for food and shelter.

Every able-bodied Pawnee boy in Great Bear’s village was expected to be capable of doing as much. They were encouraged to go out into the wilds on scouting expeditions which often lasted many days, during which the young redskins exercised their skill in tracking one another over the mountains, across wide stretches of rolling prairie or through mysterious forest and gloomy cañon where actual dangers lurked. And always they hunted their own food and built their own shelter.

It had been planned before the occasion of the buffalo hunt that Softfoot and three of his companions should make a camping trip down Silver Creek. Weasel Moccasin was to have been their leader. But he was now disabled by his accident. No bones had been broken; but he had lost remembrance of everything. His brain was a blank.

“He will be very sorry,” said Softfoot. “But he would not wish us to lose our scouting game. We will go without him. Little Antelope will come.”

“Why not Wenonah?” suggested Prairie Owl, who was her younger brother. “Wenonah is a good scout. She knows the secrets of Silver Creek. She can use the canoe paddle as well as she can ride a wild pony.”

“She could cook our meat,” added Mosquito Child. “She could mend our moccasins.”

“Wenonah goes out with the other Pawnee women to gather berries and camas roots for the winter,” Softfoot objected. “Little Antelope will come. I have spoken.”

During the warm days of yellow-grass, the boys had built for themselves a stout birch-bark canoe, and Softfoot had painted a big red eye on either side of its tall prow, so that it might find its way through the unfamiliar creeks and keep guard against mischievous water-sprites.

It was a good canoe. Everything about it had been ready before the coming of the buffalo, and now that the herd had disappeared and the camp was crowded with meat and robes, there was no need for any beaver trapping or antelope hunting for the supply of food.

They launched the canoe below the cataract of Rising Mist and loaded it with a small teepee and its poles, some dried buffalo meat and pemmican, their traps and snares, and cooking pots. Each boy took his bow and a good supply of hunting arrows, his knife, tomahawk and blanket; and each had his own fire-stick. Softfoot had wanted to take his wolf-cub, but he decided to leave it for Morning Bird to care for with his other pets.

They did not intend to go beyond the wilds of the Great Bear Reservation, which was their only world, but to pitch their camp in some sheltered woodland glade beside Silver Creek, where they would get fishing, trapping, and hunting to their heart’s content while living a simple, healthy life and pretending that they were an independent tribe of Indians.

Such a pitch was found in the evening of their first day’s absence. They erected their skin-covered wigwam on the high, grassy ground above the laughing water, in the midst of giant pines and grey-boled cottonwood trees.

They gathered soft balsam branches for their beds and kindled a fire of fir-cones and sweet-smelling spruce-wood, over which they cooked their buffalo meat. Softfoot was the responsible chief, and he kept strict order according to the usages and customs of their tribe. He raised his totem pole, made a wakam pit for refuse, and issued laws for keeping the camp clean and wholesome, each of his braves having special duties.

Their outfit contained nothing that was unnecessary. Even their store of food was limited. They were to hunt their own food. But there was a rich abundance. Ripe meenahga and odahmin berries grew in plenty near their lodge. In a hollow fir tree they found a hive of bees with great combs of honey; and the water of the creek was pure and cool for drink. They had everything they needed, everything they could desire. They were happy, and they sang songs, and danced around their fire.

Before nightfall they laid their snares and traps and kindled their mosquito smudge, and as the shadows deepened, they crept into their teepee and were lulled to sleep by the chirping of insects and the loud, clear notes of the whip-poor-will.

After their bathe in the morning, while Softfoot was cooking a salmon caught in the creek, his companions having gone round the line of traps, Little Antelope came running back to the lodge.

“We have caught nothing!” he announced in dismay. “Our traps are empty!”

“Ugh! You did not set them well,” said Softfoot. “Or perhaps it is that the animals get so much food that your bait does not tempt them. The forest is crowded with animals. Their tracks and runways are everywhere. I heard many animals moving and talking in the night.”

“Our traps have been sprung,” said Little Antelope. “But the animals and bait have been stolen. Prairie Owl thinks that some Indian has stolen them.”

“My medicine tells me that we are alone in this forest,” said Softfoot, turning the heavy fish with the tongs he had made of a supple cane of willow. “Let the Pawnees come into camp and eat of this good fish. To-night they will bait only one trap, and set no snares. Softfoot will discover the thief.”

When night came, after a long day’s prowling in the woodland, he bade his braves go to sleep. But he sat with his arm about his knees thinking deeply, watching and waiting until the moon’s light pierced the dark trees.

Then leaving the wigwam he went out alone with his bow and a sheaf of arrows, and crept with silent tread into the solemn loneliness of the moonlit groves until he came near to the baited trap. He did not touch it, lest his hand should leave its betraying man-scent. But he sniffed the air and knew that the tempting bait of buffalo meat had not been disturbed.

He drew back into the deep gloom a bow-shot’s distance from the trap. There he crouched with his bow and an arrow in his left hand, watching, listening, smelling. From afar he heard the short, sharp bark of a fox, the high-keyed howl of a prowling coyote, the pained squeak of some captured creature of the wild. Above his head a night-hawk flew past on noiseless wing. Many a tragedy was being enacted in that primeval forest. Softfoot realized as never before that, like his own human kind, the wild animals must kill to live.

For hours he crouched, never stirring, never making a sound, always patiently watching the trap. Once he saw a black fox stealing across the dividing space. It paused only an instant beside the trap, and as it turned into a shaft of moonlight, Softfoot saw that it carried a sage-hen in its jaws. Soon afterwards a young lynx passed like a stealthy shadow. He saw it lift its tufted ears and stalk softly to the trap. Then as the trap was sprung there was a screech, a spitting snarl, and the violent scratching of clawed feet.

Softfoot waited. He knew that the raider of the traps was not a lynx. A porcupine darted past with bristling quills. A chipmunk peeped out of its burrow under a tree-root.

After another long wait there came a quite different animal—a furry, bear-shaped beast with a short, hairy tail. Softfoot knew now that his first surmise was correct. This was the gluttonous raider of the traps. He saw it now tugging at the lynx and at the same time gnawing and eating. He fixed his arrow, took aim and pulled his bowstring. The arrow flashed silently through a gleam of moonlight. There was a harsh cry, half scream, half roar, a mad kicking and grunting, and then all was still.

Gripping his bow and arrows in one hand and his knife in the other, Softfoot strode forward. But he had no need to use his knife. The marauder was quite dead when he hoisted its heavy weight over his shoulder.

Little Antelope drew back the skin-flap of the teepee and saw Softfoot throw down his heavy burden.

“What is it, that animal?” he asked.

“It is a wolverine,” Softfoot told him. “It is the thief who robbed our traps. While he lived we could never have caught anything.”

For a week or more thereafter they set their traps and snares every evening, and in the mornings they had always a big catch. They soon had too much food, and their bale of pelts grew high.

“After one more sleep,” said Softfoot one evening, “we will take Little Antelope to see the Red Squaw. He has never seen her.”

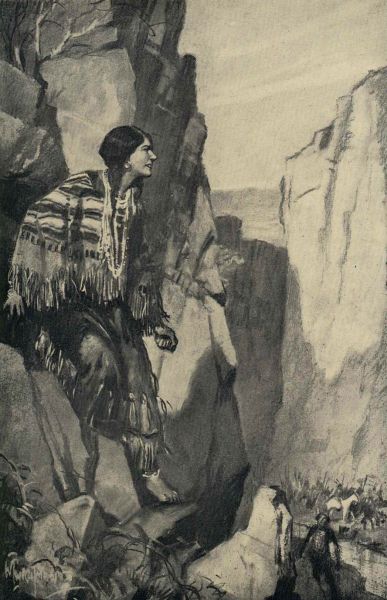

They packed their peltry in the teepee and closed the flap so that no prowling animals should intrude. Taking only some berries and a small parfleche of pemmican, they launched their canoe and paddled down the swift current of the creek. By midday they were at the mouth of Red Squaw Cañon, where the creek narrowed into a deep, gloomy gorge.

“We can climb the mountain and look down into the cañon,” said Softfoot.

“Why not go through in the canoe?” questioned Prairie Owl.

“We cannot come back against the rapids,” said Softfoot. “We should lose our canoe. We should have to go back to the lodges on foot. And it is not safe, without men to help us to get past the Red Squaw Rock.”

“Is Softfoot afraid?” asked Mosquito Child.

Softfoot fingered his medicine bag and shook his head. Whereupon they decided to make the adventure.

They trimmed the canoe for the encounter, Softfoot taking the steering paddle. The strong current raced through the gorge, like a giant tongue licking its way between steep walls of red rock that rose thousands of feet high on either side.

There was only a narrow ribbon of blue sky far above, and its light was not strong enough to break the deep gloom. Very soon the glassy, smooth water became ruffled, splashing into ominous waves and sending up a mist of spray. The canoe swayed menacingly.

“Turn back!” cried Little Antelope. “I am afraid.”

“Do not look up,” said Mosquito Child. “Count the beads on your moccasins.”

Rearing and plunging like a maddened horse, the canoe swept suddenly round a projecting bend. In advance of it the quickened current boiled and swirled in angry, seething foam, and like a warning sentinel in midstream stood the Red Squaw Rock. Softfoot was bending over, grimly determined, clutching his paddle, with all his thoughts and energies fixed upon getting past that peril. Everything depended upon his skill.

Little Antelope raised his terrified eyes and saw what was in front of them.

“Turn back!” he cried. “Softfoot, turn back!”

And the echoing cañon flung out his desperate appeal, repeating it many times.

“Turn back! Softfoot, turn back, turn back!”

“TURN back, Softfoot! Turn back, turn back!”

The echo was repeated in weird reverberation from the sheer rock walls of the cañon; at first loud and clear, and then dying down to a whisper.

It came to Softfoot’s ears like the voice of some mysterious spirit of the sinister desolation, warning him of his great danger. He heard it above the deep-throated roar of the angry current that was sweeping him and his three companions helplessly onward to calamity.

There was no chance to turn back, no chance for even a moment’s pause in which to rest his aching wrists and the tensely strained muscles of his arms and body. He could only trust to the protection of his “medicine” and hold grimly to his steering paddle, forcing the frail canoe to right or to left as it went on its mad career into the dark gorge.

“I want to do this thing, because I am afraid to do it,” he told himself. “My medicine will help me. We shall come to no harm.”

The stream was narrowing. The air grew dark and chill. On each side of him, so close that it seemed that he could almost touch them with his paddle, were black, moist walls towering up to dizzy heights.

The rushing water seemed to leap and bound like a living monster, its middle arching two or three feet higher than its sides. It surged on in great billows, green, hillocky, and terribly swift, dividing into two separate streams where, close in advance of the canoe, it was flung to either side by the intervening obstacle of Red Squaw Rock. And the canoe raced forward buoyantly, held aloft on the water’s convex surface while the black, mossy walls swept past half hidden in a mist of flying spray.

Little Antelope lay trembling in the bilge, closing his eyes and waiting for the final crash that meant inevitable destruction.

“I am afraid!” he wailed piteously. “Afraid!” And the cañon repeated the word: “Afraid, afraid!” while the surging waters laughed mockingly.

Crouched on his bare knees behind Softfoot, Mosquito Child caught at the stout shaft of the steering paddle, adding the strength of his two hands to keep the canoe under control. They were now plunging headlong onward as if drawn by some magnetic force into the gnarled face of the Red Squaw.

If the side of the bark canoe should but graze against that rock, the whole frail fabric would be torn to splinters, and no swimmer could live in the turbulent swirl of angry waves that circled round.

The muscles of Softfoot’s back and arms stood out in heaving convolutions as he held the paddle blade desperately against the fierce pressure of the stream. Prairie Owl gripped the gunwale and swayed his weight from side to side to preserve the balance so that they might not be swamped.

At the critical moment the paddle was lifted. The prow swerved obediently. Then the canoe was caught with a violent jerk that swept it into the right-hand current, and it was carried like a floating arrow through the narrow channel of curving green water, past the pinnacle, but again to plunge into a swirling eddy of leaping foam, where the divided streams were rejoined beyond the rock.

“My medicine is good,” murmured Softfoot. It was his Indian way of expressing his fervent thanks to Providence that the peril was safely past.

Mosquito Child relinquished his hold of the paddle and devoted himself to keeping the canoe steady, while Softfoot continued to ward it off from the cliffs by keeping in midstream.

Once more they were whirled off in the main current with its fearsome dips and rises and its downward-sloping rapids. The steep enclosing walls of the cañon, dripping with moisture, scarred into dimly fantastic shapes, still shut out the sky and filled the deep gorge with the gloom of eternal twilight.

For two or more miles this gloom continued. Then gradually the rocky walls grew wider apart and enough light penetrated the depths to show the green fronds of ferns and the red fringes of moss.

The waters ceased to roar and to lash the canoe with spray; and the leaping torrent subsided into a ripple of frothy waves. Suddenly the light grew strong again.

“We are through!” cried Prairie Owl. “Sit up, Little Antelope, and look!”

Little Antelope scrambled to his knees and saw that the canoe was no longer in Red Squaw Cañon, but sweeping smoothly through an open green valley brilliant with sunlit prairie flowers.

All four of the Pawnee boys now seized their paddles.

“Stop!” commanded Softfoot when they had drifted some distance. “We cannot go back to our teepee in the woods by way of the cañon. Our canoe is of no use. We must get out of it. We must walk. It is a long trail. We will make camp and rest for awhile. There is a small creek in the pine wood beyond the next hill where there is good ground and good hunting. Men call it Ghost Pine Creek.”

He paused, crouching, with his dripping paddle across his naked brown thighs. He was sniffing the warm air like a wild creature of the prairie scenting a possible enemy from afar; his sensitive nostrils were twitching. He held up a finger, enjoining silence. Then again he sniffed.

“Softfoot smells the good scent of the roses among the sage grass,” said Prairie Owl. “He hears the whisper of the wind in the pine trees.”

Softfoot dipped his paddle, but his gaze was fixed upon the fringe of fir trees on the ridge of the nearest hill.

“No Indians but our own Pawnees would make camp on the Mishe-mokwa Reserve,” he said to his companions. “Yet there is a camp-fire burning in Ghost Pine Valley. I smell the wood smoke. I hear the tread of feet, the voices of men. They are perhaps our enemies. Put away your paddle, Mosquito Child. Be ready with your bow and arrows. And you, too, Little Antelope. Go softly. We will land on the farther bank, where these strangers cannot reach us. We shall see them as we pass the mouth of the creek.”

Prairie Owl and he plied their paddles swiftly but cautiously, making no sound, while the other two crouched with only their heads and shoulders above the level of the gunwale, each with an arrow fixed on his bowstring.

The canoe glided smoothly in the current, moving like a shadow under the farther cliff. It passed beyond the wooded hill, which now sloped down into a grassy vale, broken by rough boulders and rocky bluffs, and intersected by the bed of a narrow watercourse.

On the higher ground two or three hobbled horses and some mules could be seen grazing. Softfoot quickly made out the shapes of white canvas tents under the sheltering trees, where camp-fires were sending up a thin blue mist of smoke. Near them was a covered prairie wagon such as he had never before seen. Its wheels were strange to him. Among the boulders in the watercourse he saw the figures of men wearing wide hats, red shirts, and heavy boots that reached high above their knees. He thought of his friend, Blue Eye.

“They are paleface men,” declared Little Antelope. “Why are they here? What are they doing?”

“DO not be afraid,” said Softfoot. “The paleface people are our best friends.”

“But one of them has a gun,” urged Little Antelope, raising himself on his knees. “He has seen us! Paddle quickly! He is going to shoot at us. See! He is under the birch trees on the high bluff!”

Softfoot could see the man, standing hardly a bow-shot’s distance away, taking aim at the canoe with his rifle. He seemed to have been posted on the bluff on sentry duty. Little Antelope lifted his bow and gripped the arrow on its string.

“Wait!” commanded Softfoot. “Take care!”

But even as he spoke there was a puff of powder-smoke from the gun. A bullet hummed like a bee over his head and struck the red cliff beyond him.