* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 5, Issue 12

Date of first publication: 1869

Author: John Townsend Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: May 15, 2016

Date last updated: May 15, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160516

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

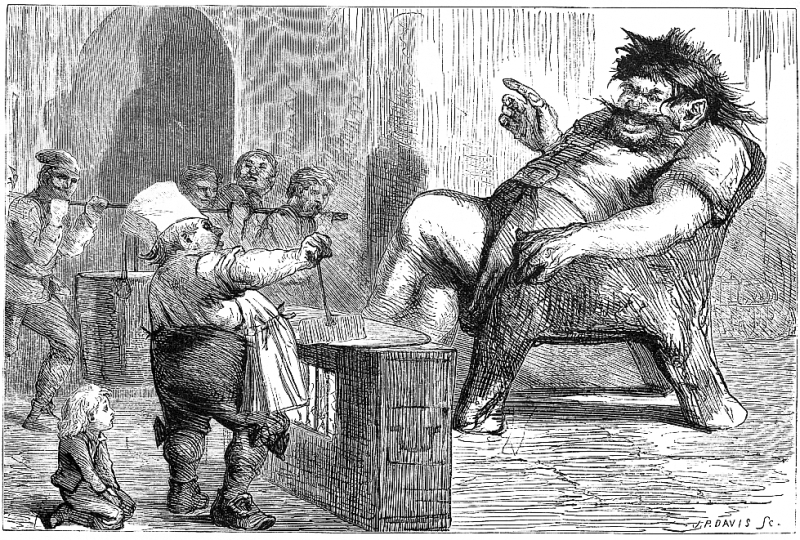

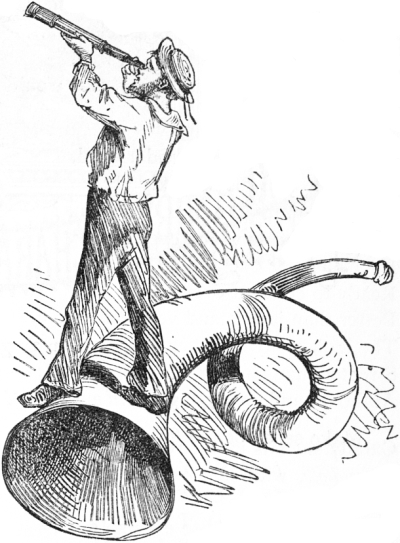

THE GIANT’S SUPPER.

Drawn by S. Eytinge, Jr.] [See the Story “Hot Buckwheat Cakes.”

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. V. | December, 1869. | No. XII. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by Fields, Osgood, & Co., in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

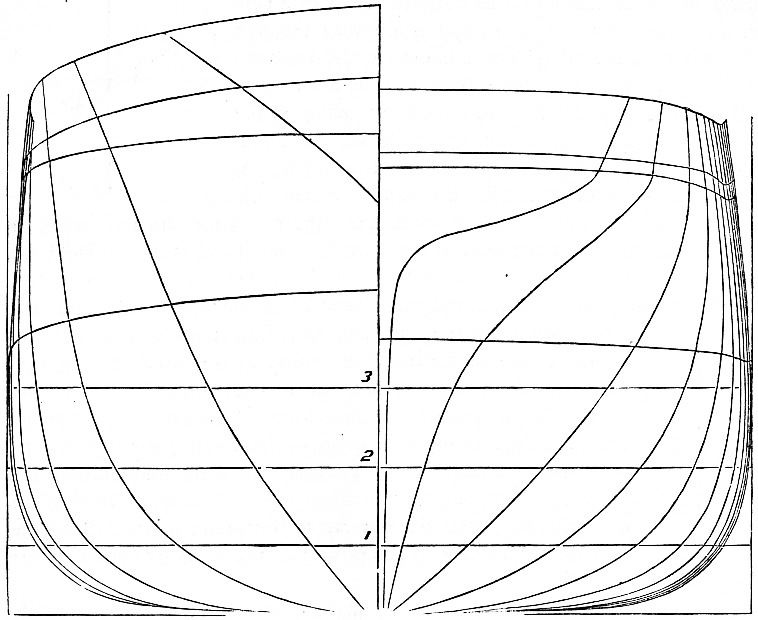

HOW A SHIP IS MODELLED AND LAUNCHED.

A DECEMBER CHARADE.—(FAREWELL.)

A letter with a great black seal!

I knew then what had happened as well as I know it now. But which was it, father or mother? I do not like to look back to the agony and suspense of that moment.

My father had died at New Orleans during one of his weekly visits to the city. The letter bearing these tidings had reached Rivermouth the evening of my flight,—had passed me on the road by the down train.

I must turn back for a moment to that eventful evening. When I failed to make my appearance at supper, the Captain began to suspect that I had really started on my wild tour southward,—a conjecture which Sailor Ben’s absence helped to confirm. I had evidently got off by the train and Sailor Ben had followed me.

There was no telegraphic communication between Boston and Rivermouth in those days; so my grandfather could do nothing but await the result. Even if there had been another mail to Boston, he could not have availed himself of it, not knowing how to address a message to the fugitives. The post-office was naturally the last place either I or the Admiral would think of visiting.

My grandfather, however, was too full of trouble to allow this to add to his distress. He knew that the faithful old sailor would not let me come to any harm, and, even if I had managed for the time being to elude him, was sure to bring me back sooner or later.

Our return, therefore, by the first train on the following day did not surprise him.

I was greatly puzzled, as I have said, by the gentle manner of his reception; but when we were alone together in the sitting-room, and he began slowly to unfold the letter, I understood it all. I caught a sight of my mother’s handwriting in the superscription, and there was nothing left to tell me.

My grandfather held the letter a few seconds irresolutely, and then commenced reading it aloud; but he could get no further than the date.

“I can’t read it, Tom,” said the old gentleman, breaking down. “I thought I could.”

He handed it to me. I took the letter mechanically, and hurried away with it to my little room, where I had passed so many happy hours.

The week that followed the receipt of this letter is nearly a blank in my memory. I remember that the days appeared endless; that at times I could not realize the misfortune that had befallen us, and my heart upbraided me for not feeling a deeper grief; that a full sense of my loss would now and then sweep over me like an inspiration, and I would steal away to my chamber or wander forlornly about the gardens. I remember this, but little more.

As the days went by my first grief subsided, and in its place grew up a want which I have experienced at every step in life from boyhood to manhood. Often, even now, after all these years, when I see a lad of twelve or fourteen walking by his father’s side, and glancing merrily up at his face, I turn and look after them, and am conscious that I have missed companionship most sweet and sacred.

I shall not dwell on this portion of my story, which, like the old year, is drawing to an end. There were many tranquil, pleasant hours in store for me at that period, and I prefer to turn to them.

One evening the Captain came smiling into the sitting-room with an open letter in his hand. My mother had arrived at New York, and would be with us the next day. For the first time in weeks—years, it seemed to me—something of the old cheerfulness mingled with our conversation round the evening lamp. I was to go to Boston with the Captain to meet her and bring her home. I need not describe that meeting. With my mother’s hand in mine once more, all the long years we had been parted appeared like a dream. Very dear to me was the sight of that slender, pale woman passing from room to room, and lending a patient grace and beauty to the saddened life of the old house.

Everything was changed with us now. There were consultations with lawyers, and signing of papers, and correspondence; for my father’s affairs had been left in great confusion. And when these were settled, the evenings were not long enough for us to hear all my mother had to tell of the scenes she had passed through in the ill-fated city.

Then there were old times to talk over, full of reminiscences of Aunt Chloe and little Black Sam. Little Black Sam, by the by, had been taken by his master from my father’s service ten months previously, and put on a sugar-plantation near Baton Rouge. Not relishing the change, Sam had run away, and by some mysterious agency got into Canada, from which place he had sent back several indecorous messages to his late owner. Aunt Chloe was still in New Orleans, employed as nurse in one of the cholera hospital wards, and the Desmoulins, near neighbors of ours, had purchased the pretty stone house among the orange-trees.

How all these simple details interested me will be readily understood by any boy who has been long absent from home.

I was sorry when it became necessary to discuss questions more nearly affecting myself. I had been removed from school temporarily, but it was decided, after much consideration, that I should not return, the decision being left, in a manner, in my own hands.

The Captain wished to carry out his son’s intention and send me to college, for which I was nearly fitted; but our means did not admit of this. The Captain, too, could ill afford to bear the expense, for his losses by the failure of the New Orleans business had been heavy. Yet he insisted on the plan, not seeing clearly what other disposal to make of me.

In the midst of our discussions a letter came from my Uncle Snow, a merchant in New York, generously offering me a place in his counting-house. The case resolved itself into this: If I went to college, I should have to be dependent on Captain Nutter for several years, and at the end of the collegiate course would have no settled profession. If I accepted my uncle’s offer, I might hope to work my way to independence without loss of time. It was hard to give up the long-cherished dream of being a Harvard boy; but I gave it up.

The decision once made, it was Uncle Snow’s wish that I should enter his counting-house immediately. The cause of my good uncle’s haste was this,—he was afraid that I would turn out to be a poet before he could make a merchant of me. His fears were based upon the fact that I had published in the Rivermouth Barnacle some verses addressed in a familiar manner “To the Moon.” Now, the idea of a boy, with his living to get, placing himself in communication with the Moon, struck the mercantile mind as monstrous. It was not only a bad investment, it was lunacy.

We adopted Uncle Snow’s views so far as to accede to his proposition forthwith. My mother, I neglected to say, was also to reside in New York.

I shall not draw a picture of Pepper Whitcomb’s disgust when the news was imparted to him, nor attempt to paint Sailor Ben’s distress at the prospect of losing his little messmate.

In the excitement of preparing for the journey I didn’t feel any very deep regret myself. But when the moment came for leaving, and I saw my small trunk lashed up behind the carriage, then the pleasantness of the old life and a vague dread of the new came over me, and a mist filled my eyes, shutting out the group of schoolfellows, including all the members of the Centipede Club, who had come down to the house to see me off.

As the carriage swept round the corner, I leaned out of the window to take a last look at Sailor Ben’s cottage, and there was the Admiral’s flag flying at half-mast!

So I left Rivermouth, little dreaming that I was not to see the old place again for many and many a year.

With the close of my school-days at Rivermouth this modest chronicle ends.

The new life upon which I entered, the new friends and foes I encountered on the road, and what I did and what I did not, are matters that do not come within the scope of these pages. But before I write Finis to the record as it stands, before I leave it,—feeling as if I were once more going away from my boyhood,—I have a word or two to say concerning a few of the personages who have figured in the story, if you will allow me to call Gypsy a personage.

I am sure that the reader who has followed me thus far will be willing to hear what became of her, and Sailor Ben and Miss Abigail and the Captain.

First about Gypsy. A month after my departure from Rivermouth the Captain informed me by letter that he had parted with the little mare, according to agreement. She had been sold to the ring-master of a travelling circus (I had stipulated on this disposal of her), and was about to set out on her travels. She did not disappoint my glowing anticipations, but became quite a celebrity in her way,—by dancing the polka to slow music on a pine-board ball-room constructed for the purpose.

I chanced once, a long while afterwards, to be in a country town where her troup was giving exhibitions; I even read the gaudily illumined showbill, setting forth the accomplishments of

—but failed to recognize my dear little Mustang girl behind those high-sounding titles, and so, alas! did not attend the performance.

I hope all the praises she received and all the spangled trappings she wore did not spoil her; but I am afraid they did, for she was always over much given to the vanities of this world!

Miss Abigail regulated the domestic destinies of my grandfather’s household until the day of her death, which Dr. Theophilus Tredick solemnly averred was hastened by the inveterate habit she had contracted of swallowing unknown quantities of hot-drops whenever she fancied herself out of sorts. Eighty-seven empty phials were found in a bonnet-box on a shelf in her bedroom closet.

The old house became very lonely when the family got reduced to Captain Nutter and Kitty; and when Kitty passed away, my grandfather divided his time between Rivermouth and New York.

Sailor Ben did not long survive his little Irish lass, as he always fondly called her. At his demise, which took place about six years since, he left his property in trust to the managers of a “Home for Aged Mariners.” In his will, which was a very whimsical document,—written by himself, and worded with much shrewdness, too,—he warned the Trustees that when he got “aloft” he intended to keep his “weather eye” on them, and should send “a speritual shot across their bows” and bring them to, if they didn’t treat the Aged Mariners handsomely.

He also expressed a wish to have his body stitched up in a shotted hammock and dropped into the harbor; but as he did not strenuously insist on this, and as it was not in accordance with my grandfather’s preconceived notions of Christian burial, the Admiral was laid to rest beside Kitty, in the Old South Burying Ground, with an anchor that would have delighted him neatly carved on his headstone.

I am sorry the fire has gone out in the old ship’s stove in that sky-blue cottage at the head of the wharf; I am sorry they have taken down the flag-staff and painted over the funny port-holes; for I loved the old cabin as it was. They might have let it alone!

For several months after leaving Rivermouth I carried on a voluminous correspondence with Pepper Whitcomb; but it gradually dwindled down to a single letter a month, and then to none at all. But while he remained at the Temple Grammar School he kept me advised of the current gossip of the town and the doings of the Centipedes.

As one by one the boys left the academy,—Adams, Harris, Marden, Blake, and Langdon,—to seek their fortunes elsewhere, there was less to interest me in the old seaport; and when Pepper himself went to Philadelphia to read law, I had no one to give me an inkling of what was going on.

There wasn’t much to go on, to be sure. Great events no longer considered it worth their while to honor so quiet a place. One Fourth of July the Temple Grammar School burnt down,—set fire, it was supposed, by an eccentric squib that was seen to bolt into an upper window,—and Mr. Grimshaw retired from public life, married, “and lived happily ever after,” as the story-books say.

The Widow Conway, I am able to state, did not succeed in enslaving Mr. Meeks, the apothecary, who united himself clandestinely to one of Miss Dorothy Gibbs’s young ladies, and lost the patronage of Primrose Hall in consequence.

Young Conway went into the grocery business with his ancient chum, Rogers,—Rogers & Conway! I read the sign only last summer when I was down in Rivermouth, and had half a mind to pop into the shop and shake hands with him, and ask him if he wanted to fight. I contented myself, however, with flattening my nose against his dingy shop-window, and beheld Conway, in red whiskers and blue overalls, weighing out sugar for a customer,—giving him short weight, I’ll bet anything!

I have reserved my pleasantest word for the last. It is touching the Captain. The Captain is still hale and rosy, and if he doesn’t relate his exploit in the War of 1812 as spiritedly as he used to, he makes up by relating it more frequently and telling it differently every time! He passes his winters in New York and his summers in the Nutter House, which threatens to prove a hard nut for the destructive gentleman with the scythe and the hour-glass, for the seaward gable has not yielded a clapboard to the east-wind these twenty years. The Captain has now become the Oldest Inhabitant in Rivermouth, and so I don’t laugh at the Oldest Inhabitant any more, but pray in my heart that he may occupy the post of honor for half a century to come!

So ends the Story of a Bad Boy,—but not such a very bad boy, as I told you to begin with.

Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

Some boys and girls are born so that they enjoy society, and all the forms of society, from the beginning. The passion they have for it takes them right through all the formalities and stiffness of morning calls, evening parties, visits on strangers, and the like, and they have no difficulty about the duties involved in these things. I do not write for them, and there is no need, at all, of their reading this paper.

There are other boys and girls who look with half horror and half disgust at all such machinery of society. They have been well brought up, in intelligent, civilized, happy homes. They have their own varied and regular occupations, and it breaks these all up, when they have to go to the birthday party at the Glascocks’, or to spend the evening with the young lady from Vincennes who is visiting Mrs. Schemerhorn.

When they have grown older, it happens, very likely, that such boys and girls have to leave home, and establish themselves at one or another new home, where more is expected of them in a social way. Here is Stephen, who has gone through the High School, and has now gone over to New Altona to be the second teller in the Third National Bank there. Stephen’s father was in college with Mr. Brannan, who was quite a leading man in New Altona. Madam Chenevard is a sister of Mrs. Schuyler, with whom Stephen’s mother worked five years on the Sanitary Commission. All the bank officers are kind to Stephen, and ask him to come to their houses, and he, who is one of these young folks whom I have been describing, who knows how to be happy at home, but does not know if he is entertaining or in any way agreeable in other people’s homes, really finds that the greatest hardship of his new life consists in the hospitalities with which all these kind people welcome him.

Here is a part of a letter from Stephen to me,—he writes pretty much everything to me: “. . . . Mrs. Judge Tolman has invited me to another of her evening parties. Everybody says they are very pleasant, and I can see that they are to people who are not sticks and oafs. But I am a stick and an oaf. I do not like society, and I never did. So I shall decline Mrs. Tolman’s invitation; for I have determined to go to no more parties here, but to devote my evenings to reading.”

Now this is not snobbery or goodyism on Stephen’s part. He is not writing a make-believe letter, to deceive me as to the way in which he is spending his time. He really had rather occupy his evening in reading than in going to Mrs. Tolman’s party,—or to Mrs. Anybody’s party,—and, at the present moment, he really thinks he never shall go to any parties again. Just so two little girls part from each other on the sidewalk, saying, “I never will speak to you again as long as I live.” Only Stephen is in no sort angry with Mrs. Tolman or Mrs. Brannan or Mrs. Chenevard. He only thinks that their way is one way, and his way is another.

It is for boys and girls like Stephen, who think they are “sticks and oafs,” and that they cannot go into society, that this paper is written.

You need not get up from your seats and come and stand in a line for me to talk to you,—tallest at the right, shortest at the left, as if you were at dancing-school, facing M. Labbassé. I can talk to you just as well where you are sitting; and, as Obed Clapp said to me once, I know very well what you are going to say, before you say it. Dear children, I have had it said to me fourscore and ten times by forty-six boys and forty-four girls who were just as dull and just as bright as you are,—as like you, indeed, as two pins.

There is Dunster,—Horace Dunster,—at this moment the favorite talker in Washington, as indeed he is in the House of Representatives. Ask, the next time you are at Washington, how many dinner-parties are put off till a day can be found at which Dunster can be present. Now I remember very well, how, a year or two after Dunster graduated, he and Messer, who is now Lieutenant-Governor of Labrador, and some one whom I will not name, were sitting on the shore of the Cattaraugus Lake, rubbing themselves dry after their swim. And Dunster said he was not going to any more parties. Mrs. Judge Park had asked him, because she loved his sister, but she did not care for him a straw, and he did not know the Cattaraugus people, and he was afraid of the girls, who knew a great deal more than he did, and so he was “no good” to anybody, and he would not go any longer. He would stay at home and read Plato in the original. Messer wondered at all this; he enjoyed Mrs. Judge Park’s parties, and Mrs. Dr. Holland’s teas, and he could not see why as bright a fellow as Dunster should not enjoy them. “But I tell you,” said Dunster, “that I do not enjoy them; and, what is more, I tell you that these people do not want me to come. They ask me because they liked my sister, as I said, or my father, or my mother.”

Then some one else, who was there, whom I do not name, who was at least two years older than these young men, and so was qualified to advise them, addressed them thus:—

“You talk like children. Listen. It is of no consequence whether you like to go to these places or do not like to go. None of us were sent to Cattaraugus to do what we like to do. We were sent here to do what we can to make this place cheerful, spirited, and alive,—a part of the kingdom of heaven. Now if everybody in Cattaraugus sulked off to read Plato, or to read “The Three Guardsmen,” Cattaraugus would go to the dogs very fast, in its general sulkiness. There must be intimate social order, and this is the method provided. Therefore, first, we must all of us go to these parties, whether we want to or not; because we are in the world, not to do what we like to do, but what the world needs.

“Second,” said this unknown some one, “nothing is more snobbish than this talk about Mrs. Park’s wanting us or not wanting us. It simply shows that we are thinking of ourselves a good deal more than she is. What Mrs. Park wants is as many men at her party as she has women. She has made her list so as to balance them. As the result of that list, she has said she wanted me. Therefore I am going. Perhaps she does want me. If she does, I shall oblige her. Perhaps she does not want me. If she does not, I shall punish her, if I go, for telling what is not true; and I shall go cheered and buoyed up by that reflection. Any way I go, not because I want to or do not want to, but because I am asked; and in a world of mutual relationships it is one of the things that I must do.”

No one replied to this address, but they all three put on their dress-coats and went. Dunster went to every party in Cattaraugus that winter, and, as I have said, has since shown himself a most brilliant and successful leader of society.

The truth is to be found in this little sermon. Take society as you find it in the place where you live. Do not set yourself up, at seventeen years old, as being so much more virtuous or grand or learned than the young people round you, or the old people round you, that you cannot associate with them on the accustomed terms of the place. Then you are free from the first difficulty of young people who have trouble in society; for you will not be “stuck up,” to use a very happy phrase of your own age. When anybody, in good faith, asks you to a party, and you have no pre-engagement or other duty, do not ask whether these people are above you or below you, whether they know more or know less than you do, least of all ask why they invited you,—but simply go. It is not of much importance whether, on that particular occasion, you have what you call a good time or do not have it. But it is of importance that you shall not think yourself a person of more consequence in the community than others, and that you shall easily and kindly adapt yourself to the social life of the people among whom you are.

This is substantially what I have written to Stephen about what he is to do at New Altona.

Now, as for enjoying yourself when you have come to the party,—for I wish you to understand that, though I have compelled you to go, I am not in the least cross about it,—but I want you to have what you yourselves call a very good time when you come there. O dear, I can remember perfectly the first formal evening party at which I had “a good time.” Before that I had always hated to go to parties, and since that I have always liked to go. I am sorry to say I cannot tell you at whose house it was. That is ungrateful in me. But I could tell you just how the pillars looked between which the sliding doors ran, for I was standing by one of them when my eyes were opened, as the Orientals say, and I received great light. I had been asked to this party, as I supposed and as I still suppose, by some people who wanted my brother and sister to come, and thought it would not be kind to ask them without asking me. I did not know five people in the room. It was in a college town where there were five gentlemen for every lady, so that I could get nobody to dance with me of the people I did know. So it was that I stood sadly by this pillar, and said to myself, “You were a fool to come here where nobody wants you, and where you did not want to come; and you look like a fool standing by this pillar with nobody to dance with and nobody to talk to.” At this moment, and as if to enlighten the cloud in which I was, the revelation flashed upon me, which has ever since set me all right in such matters. Expressed in words, it would be stated thus: “You are a much greater fool if you suppose that anybody in this room knows or cares where you are standing or where you are not standing. They are attending to their affairs and you had best attend to yours, quite indifferent as to what they think of you.” In this reflection I took immense comfort, and it has carried me through every form of social encounter from that day to this day. I don’t remember in the least what I did, whether I looked at the portfolios of pictures,—which for some reason young people think a very poky thing to do, but which I like to do,—whether I buttoned some fellow-student who was less at ease than I, or whether I talked to some nice old lady who had seen with her own eyes half the history of the world which is worth knowing. I only know that, after I found out that nobody else at the party was looking at me or was caring for me, I began to enjoy it as thoroughly as I enjoyed staying at home.

Not long after I read this in Sartor Resartus, which was a great comfort to me: “What Act of Parliament was there that you should be happy? Make up your mind that you deserve to be hanged, as is most likely, and you will take it as a favor that you are hanged in silk and not in hemp.” Of which the application in this particular case is this: that if Mrs. Park or Mrs. Tolman are kind enough to open their beautiful houses for me, to fill them with beautiful flowers, to provide a band of music, to have ready their books of prints and their foreign photographs, to light up the walks in the garden and the greenhouse, and to provide a delicious supper for my entertainment, and then ask, I will say, only one person whom I want to see, is it not very ungracious, very selfish, and very snobbish for me to refuse to take what is, because of something which is not,—because Ellen is not there or George is not? What Act of Parliament is there that I should have everything in my own way?

As it is with most things, then, the rule for going into society is not to have any rule at all. Go unconsciously; or, as St. Paul puts it, “Do not think of yourself more highly than you ought to think.” Everything but conceit can be forgiven to a young person in society. St. Paul, by the way, high-toned gentleman as he was, is a very thorough guide in such affairs, as he is in most others. If you will get the marrow out of those little scraps at the end of his letters, you will not need any hand-books of etiquette.

As I read this over, to send it to the editor, I recollect that, in one of the nicest sets of girls I ever knew, they called the thirteenth chapter of the First Epistle to the Corinthians the “society chapter.” Read it over, and see how well it fits, the next time Maud has been disagreeable, or you have been provoked yourself in the “German.”

“The gentleman is quiet,” says Mr. Emerson, whose essay on society you will read with profit, “the lady is serene.” Bearing this in mind, you will not really expect, when you go to the dance at Mrs. Pollexfen’s, that while you were standing in the library explaining to Mr. Sumner what he does not understand about the Alabama Claims, watching at the same time with jealous eye the fair form of Sybil as she is waltzing in that hated Clifford’s arms,—you will not, I say, really expect that her light dress will be wafted into the gaslight over her head, she be surrounded with a lambent flame, Clifford basely abandon her, while she cries, “O Ferdinand, Ferdinand!”—nor that you, leaving Mr. Sumner, seizing Mrs. General Grant’s camel’s hair shawl, rushing down the ball-room, will wrap it around Sybil’s uninjured form, and receive then and there the thanks of her father and mother, and their pressing request for your immediate union in marriage. Such things do not happen outside the Saturday newspapers, and it is a great deal better that they do not. “The gentleman is quiet, and the lady is serene.” In my own private judgment, the best thing you can do at any party is the particular thing which your host or hostess expected you to do when she made the party. If it is a whist party, you had better play whist, if you can. If it is a dancing party, you had better dance, if you can. If it is a music party, you had better play or sing, if you can. If it is a croquet party, join in the croquet, if you can. When at Mrs. Thorndike’s grand party, Mrs. Colonel Goffe, at seventy-seven, told old Rufus Putnam, who was five years her senior, that her dancing days were over, he said to her, “Well, it seems to be the amusement provided for the occasion.” I think there is a good deal in that. At all events, do not separate yourself from the rest as if you were too old or too young, too wise or too foolish, or hadn’t been enough introduced, or were in any sort of different clay from the rest of the pottery.

And now I will not undertake any specific directions for behavior. You know I hate them all. I will only repeat to you the advice which my best friend gave me after the first evening call I ever made. The call was on a gentleman whom both I and my adviser greatly loved. I knew he would be pleased to hear that I had made the visit, and, with some pride, I told him, being, as I calculate, thirteen years five months and nineteen days old. He was pleased, very much pleased, and he said so. “I am glad you made the call, it was a proper attention to Mr. Palfrey, who is one of your true friends and mine. And now that you begin to make calls, let me give you one piece of advice. Make them short. The people who see you may be very glad to see you. But it is certain they were occupied with something when you came, and it is certain, therefore, that you have interrupted them.”

I was a little dashed in the enthusiasm with which I had told of my first visit. But the advice has been worth I cannot tell how much to me,—years of life, and hundreds of friends.

Pelham’s rule for a visit is, “Stay till you have made an agreeable impression, and then leave immediately.” A plausible rule, but dangerous. What if one should not make an agreeable impression after all? Did not Belch stay till near three in the morning? And when he went, because I had dropped asleep, did I not think him more disagreeable than ever?

For all I can say, or anybody else can say, it will be the manner of some people to give up meeting other people socially. I am very sorry for them, but I cannot help it. All I can say is that they will be sorry before they are done. I wish they would read Æsop’s fable about the old man and his sons and the bundle of rods. I wish they would find out definitely why God gave them tongues and lips and ears. I wish they would take to heart the folly of this constant struggle in which they live, against the whole law of the being of a gregarious animal like man. What is it that Westerly writes me, whose note comes to me from the mail just as I finish this paper? “I do not look for much advance in the world until we can get people out of their own self.” And what do you hear me quoting to you all the time,—which you can never deny,—but that “The human race is the individual of which men and women are so many different members.” You may kick against this law, but it is true.

It is the truth around which, like a crystal round its nucleus, all modern civilization has taken order.

Edward E. Hale.

EVE.

They say to-night is Christmas Eve, and, high as I could reach,

I’ve hung my stockings on the wall, and left a kiss on each.

I left a kiss on each for Him who’ll fill my stockings quite:

He never came before, but O, I’m sure He will to-night.

And to-morrow’ll be the day our blessed Christ was born,

Who came on earth to pity me, whom many others scorn.

And why it is they treat me so indeed I cannot tell,

But while I love Him next to you, then all seems wise and well.

I long have looked for Christmas, Mother,—waited all the year;

And very strange it is indeed to feel its dawn so near;

But to-morrow’ll be the day I so have prayed to see,

And I long to sleep and wake, and find what it will bring to me.

The snow is in the street, and through the window all the day

I’ve watched the little children pass: they seemed so glad and gay!

And gayly did they talk about the gifts they would receive;—

O, all the world is glad to-night, for this is Christmas Eve!

And, Mother, on the cold, cold floor I’ve put my little shoe,—

The other’s torn across the toe, and things might there slip through;—

I’ve set my little shoe, Mother, and it for you shall be,

For I know that He’ll remember you while He remembers me.

So lay me in my bed, Mother, and hear my prayers aright.

He never came before, but O, I’m sure He will to-night.

MIDNIGHT.

Mother, is it the morning yet? I dreamed that it was here;

I thought the sun shone through the pane, so blessed and so clear.

I dreamed my little stockings there were full as they could hold.

But it’s hardly morning yet, Mother,—it is so dark and cold.

I dreamed the bells rang from the church where the happy people go,

And they rang good-will to all men in a language that I know.

I thought I took from off the wall my little stockings there,

And on the floor I emptied them,—such sights there never were!

A doll was in there, meant for me, just like those little girls

Who always turn away from me; and O, it had such curls!

I kissed it on its painted cheek; my own are not so sweet,

Though people used to stop to pat and praise them in the street.

And, mother, there were many things that would have pleased you too;

For He who had remembered me had not forgotten you.

But I only dreamed ’twas morning, and yet ’tis far away,

Though well I know that He will come before the early day.

So I will put my dream aside, though I know my dream was true,

And sleep, and dream my dream again, and rise at morn with you.

CHRISTMAS MORN.

The Mother.

All night have I waked with weeping till the bells are ringing wild,

All night have I waked with my sorrow, and lain in my tears, like a child.

For over against the wall as empty as they can be,

The limp little stockings hang, and my heart is breaking in me!

Your vision was false as the world, O darling dreamer and dear!

And how can I bear you to wake, and find no Christmas here?

Better you and I were asleep in the slumber whence none may start.

And O, those empty stockings! I could fill them out of my heart!

No Christmas for you or for me, darling; your kisses were all in vain;

I have given your kisses back to you over and over again;

I have folded you to my breast with a moaning no one hears:

Your heart is happy in dreams, though your hair is damp with my tears.

I am out of heart and hope; I am almost out of my mind;

The world is cruel and cold, and only Christ is kind:

And much must be borne and forborne; but the heaviest burden of all

That ever hath lain on my life are those little light things on the wall.

Hush, Bells, you’ll waken my dreamer! O children so full of cheer!

Be a little less glad going by; there hath been no Christmas here.

Go tenderly over the stones, O light feet tripping a tune!

The slighted thing sleeps in my arms,—she’ll waken too soon, too soon!

A. W. Bellaw.

At eight o’clock, one fine October morning, little Eddie lay fast asleep, “all curled up in a very small heap” under the fleecy blankets that covered everything that went to compose that young gentleman except the crowning curl of his kinky pate, which he called his “top.” The sun fairly blazed in at the windows,—no unwelcome guest, either; for there were no fires yet up stairs, and it was just cool enough to make one jump into daytime clothes and hurry down to the crackling chimney below.

Mamma passed through the room with a pretty wool shawl over her shoulders and a tiny bit of three-cornered lace on her “top,” which was not half so shining or curly as her little boy’s.

“Come, Eddie,” said the cheery voice, “not awake yet! Come! we have buckwheat cakes for breakfast, you know. I must send Rose up to dress you, directly.”

“O yes, mamma, do!” said the young master, rubbing his eyes and brushing back with impatient fingers the tangled curls; “and, O mamma, can I have butter on ’em and syrup too?”

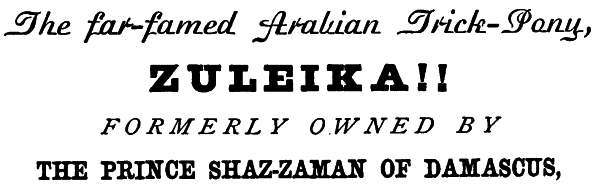

His mother laughed as she kissed his eager face: “I don’t know about that, sir; but if you are very good while Rose dresses you, and if you don’t cry when your hair is curled, it is just possible.” Mamma tripped down stairs, and the click-clack of the hoop-petticoat on the last step had scarcely died away, when a colored girl about fourteen years of age entered the bed-chamber.

“Now, Mas’ Ed,” vociferated the hand-maiden, as her charge dived into the blankets, intent upon a struggle and a frolic, “yer ma says you is to git up dreckly and lemme dress yuh. Breakfus’ is only a-waitin’ jes’ fur yer Pa. Let’s see now which one o’ yuh’ll be down fust. Up-sy, daisy! There’s a man!” and with a jump and a bump, Mas’ Ed is down on the floor in a very confused tumble of night-clothes.

“Now fur de shoes an’ stockin’s, to keep dese yer little toes warm,—sech a knot! Now, Mas’ Ed, how did yuh git dis yer string in sech a fix? Yer mus’ ha got up in yer sleep; I never lef yer shoe dat ar way in all my born days.”

“Rose, stop jerking so. I’ll tell mamma,” said Eddie, with dignity. “You know well enough that isn’t the way to get knots out of anything!” and the young philosopher looked severe, as a philosopher should.

By this time the balmorals were laced, and now came the process of washing: Rose poured water from the little pink china pitcher into the little pink china basin on the wash-stand, which, like the bedstead, bureau, and chairs, was a sort of grown-up toy, just high enough for Eddie to use in perfect comfort.

“Rose,” said Eddie, after heroically enduring the bathing, not to say scrubbing, of face and neck and hands,—the water being a little biting,—“if you will be very careful and won’t pull my hair this morning, guess what I’ll give you!”

“O, I dunno,” said Rose; “but what makes my precious think I’se a-gwine to hurt him? Goodness knows I wouldn’t pull a single har of his head for no ’mount o’ money!” Eddie was not moved by this forcible appeal; perhaps past experiences spoke more eloquently on the other side; at any rate he renewed his proposal:—

“I’ll give you that beautiful wooden horse of mine with three legs and no tail!”

“Now, Eddie,” said Rose, trying hard not to laugh, “you is jest a-foolin’ me! Does yuh really mean it, ‘honor bright’?”

“Honor bright,” replied Eddie, with all the solemnity of a severe business transaction. This conversation by no means interrupted the toilet; now the little white drawers were to be buttoned, next the pretty chintz shirt to put on, and then, last of all, the Zouave trousers and little cut-away jacket.

At this point Mas’ Ed, with a towel pinned closely about his throat, was placed upon a pinnacle of pain,—to wit, a high chair, whereon he suffered three times a day the curling of his long flaxen hair. Except that it might serve as a salutary discipline for future trials of patience, it were hard to say what good purpose so much torture served. But then the hair was “so lovely,” and whenever cutting was proposed, what a chorus of ahs and ohs, indignant, appealing, or almost tearful, from grandma and aunts and cousins and from the pretty young mother herself! No, it could not be thought of for another year at least.

Well, the curling was a trial to both parties immediately concerned. Such a tangle of golden threads, all kinked up as if the fairies had been playing at hide-and-seek all night long through its soft meshes. This fanciful idea suggested itself to Rose, who, with all the aptness of her race for amusing children, wove on the instant a wonderful story that held captive Master Eddie’s impatient little limbs, and wrapped his imagination in such complete forgetfulness of the outside world, that it was only at the very sharpest twinges that he even winced.

“And the Princess Witeasmilk,” said Rose, with slow and pompous mystery, “the Princess Witeasmilk was never seed in her father’s palish after dat night; an’ jes’ as true as I’m a-standin’ yer she ’loped an’ wus married to dat very Fairy Prince she seed by de moonlight a-dancin’ onto de end of her l-o-n-g y-e-l-l-o-w c-u-r-l!” And with this startling finale came the brush and twist of Eddie’s last “long yellow curl,” and off he ran with a shout of happy emancipation.

“Laws-a-massy!” said Rose, stooping down to look at her glass beads in the little mirror of the little bureau, “de chile’s done gone forgot to say his prars; an’ I don’t wonder, wen I filled his head full o’ sech nonsense. I jes reckon de good Lord’ll take ker of him fur one day, anyhow.” So quieting her conscience, she threw open the windows and proceeded to air the sheets, blankets, and pillows of the pretty little pink bed, doing all to the high-pitched tune of “Captain Jinks.” This musical performance was not without its effect upon a smart-looking colored boy on the door-steps opposite, who turned from polishing his brasses to bestow an admiring recognition upon the singer, who returned it with interest.

In the mean time, Eddie in his high chair, with careful pinafore tied around his neck, is in the full enjoyment of the first “cakes” of the season,—his not over-judicious mother having granted his petition for “syrup and butter too,” on his share of the delicately browned circumferences, so dear to the palates of his countrymen, and so expensive to their dyspeptic digestions.

With his own silver fork—aunty’s Christmas gift—mouthful after mouthful goes plump into the rosebud of his pretty face, down into the little fat stomach, which more and more resembles a drum with the parchment drawn very tight indeed.

“My dear,” says mamma, at last, as papa, rejoicing in his boy’s good appetite, cuts up on his plate the top smoker, fresh from the new half-dozen just brought in by turbaned Dinah, who “wonders whar dat good-fur-nuthin’ Rose is now?” “My dear, don’t you think Eddie is rather over-eating? Buckwheat cakes, you know, are not considered exactly the diet for young children. Eddie, isn’t your forehead hard yet? Dear me, yes! Come, mamma’s pet, I wouldn’t eat any more.” As mamma helped herself in the act of giving this advice to her son, he very naturally decided in behalf of his appetite, notwithstanding that his forehead was very hard indeed,—a “sign” he had been taught to consider infallible ever since the days of his nursery pap. His decision was, moreover, biased by his father’s answer:—

“O, let the child eat as long as he enjoys his food. Nothing makes children so puny and delicate as the modern notion of dieting. Now, when I was a boy, I ate everything and anything; look at me!”

This young gentleman owned himself conquered at last. With but little of the vivacity which brightened the breakfast-room as he entered with good-morning kisses, he slid down from his high-chair, and moved off slowly, ponderously, half yawning, as if life were already a bore,—he the merry Puck of the house!

He threw himself down on the hearth-rug and pulled the kitten’s tail; she was lazy and would not play. Poor kitty! perhaps she had drank too much milk. Mamma went through the parlors into her little green-room to water her flower-pots and give the birds their breakfast,—happy birds! that could not eat too many buckwheat cakes! Eddie arose with some difficulty and went into the kitchen, for this was not a tabooed place to our little master, as it is to the commonwealth of young gentlemen whose cooks are Bridgets and not Dinahs. To him, the pet of the linsey petticoats, it was a resort full of entertainment, as varied as its multiplied pursuits, and of cheerful, sympathetic companionship. Rose was baking cakes for the “second table.” How delightful to watch her, as she first rubbed the sissing griddle with the lump of suet on the end of a kitchen fork, and then poured the batter which surprised (as the French cook calls it) the hot surface into an ejaculatory s-s-p-a-t-t! This in a few minutes becomes a cake, or half of one, for it must be turned, and with the “turning,” interest warms into excitement: If Rose shouldn’t hit just the right distance from the next neighbor cake! There, miss, I told you so! that one did fall half over the other! “O Rose, let me try just once! I know I could!” But Rose was hard-hearted.

“Now, Mas’ Ed, you’se too fresh; I’ll jes’ go tell yer ma to call you in de house, ef you don’t quit a-pesterin’.”

“No, you won’t, miss,” speaks up Aunt Dinah, setting down her bowl of coffee, with dignity, “I should jes’ like to know w’y de chile can’t bake de cake ef he wants to. Come hyah, honey, an’ turn one fur Aunt Dinah; course he shill. You, Rose, gim me de turner dis minit! A putty one you is to git along wid children! You isn’t wuth yer salt,—not dat I ’proves ov allers givin’ ’em der own way nuther?”

So a little cake was poured on the griddle, and Eddie held the turner; Dinah held his wrist, and they turned it between them. Then another was poured, to let him do it “by his own sef”; and then another, because he did that one “so nice.”

Finally, being reanimated by the novelty of the performance, he must eat the three he had cooked, which accordingly he did,—Aunt Dinah sagely remarking at the time:—

“ ’Pears to me dat wite folks never does ’low der children to eat as much as dey wants. Here’s dis bressed chile dat allers comes out hyah hungry, and jes’ frum de very table!”

The day wore on with less noise from Master Eddie than usual,—that is, less noise of a lively sort, for of fretting, and occasionally worse, there was no lack. I am not sure that at the curling torture preparatory to dinner he did not assault his faithful Rose, with more or less intent to hurt, refusing to hearken to her tale of the Wonderful Genie with Seven Mouths. At dinner, as his appetite was not craving, he was tempted with certain delicacies usually denied him, and especially with a rich dessert. After this repast Eddie’s temper was by no means improved; a cold, hard, leaden lump lay where a pleasant, comfortable dinner ought to have been; there was no enjoyment for him in any game or toy; even his new rocking-horse, that would take him all the way to Banbury Cross on springs, was a delusion and a bore.

Like the little girl in funny Punch, his “world was hollow,” and everything “stuffed with sawdust,” or worse, with buckwheat cakes! He was cross to everybody; he didn’t even love his “pretty mamma,” as he called her; and what the matter was the poor little fellow did not know. His cheeks were very rosy and his eyes very bright; his grandma, who came in during the afternoon, said he looked feverish, but his mother pronounced him perfectly well: “If you think he is ill, you ought to have been here at breakfast-time!”

It was getting too cool for the customary issuing forth of the children of the neighborhood on the “front pavement,” but within his little coat Eddie promenaded “round the square” several times with Rose, who on these occasions, in spite of Aunt Dinah’s protest, was indescribably vigilant and devoted,—the perfection of a born nurse. But at last the horrid day was at an end; he waited only for papa’s good-night kiss, before he went off with flushed cheeks and feverish eyes to bed. Rose undressed him by a little wood-fire kindled on the hearth; she held him on her lap while he toasted his soft pink feet, and when he was very plainly on the express-train for Shut-Eye Town, she put him in a private car and tucked him in! Mamma ran up after tea to see that her darling was all snug; he was a trifle restless only, so with a kiss and the same silly gibberish that all the mothers of all the young folks indulge in on like occasions, she left him to rejoin her husband in the parlor.

Some hours after, the inside of that little curly head was the scene of many strange performances: it wasn’t like a head at all, but rather like the stage of a theatre, full of the fantastic brilliancy of a Christmas pantomime. Part of the time Eddie was looker-on, part of the time player, and often both at once; and to do all this inside of his own little head was, to say the least, peculiarly perplexing. This hodge-podge of funny things continued, it seemed to Eddie, for years and years. He got so tired of the monkeys and the elephants and the butterflies, and of being first one and then the other; of hanging on to trees by his tail, and squirting water from his trunk, and sucking honey out of pasteboard flowers. He was so tired of the little men made of gingerbread dough, who rode furiously up and down on “horse-cakes,” grinning at him and asking him to take a bite. Then there was a supper-table, loaded down with everything nice to eat, but when they—monkeys, elephants, and all—were about to sit down to the feast, every blessed thing—beef, mutton, chickens, cakes, pies, and the rest—just turned upside down on the table and walked off with the dishes on their backs!

One of the elderly and irritable elephants became enraged at this strange proceeding and accused Eddie—who was then a monkey, scrambling for nuts—of having spoiled all their fun by his greediness; and thereupon he seized him with his trunk and threw him wildly up and down in the air,—up as high as the moon it seemed to the terrified monkey. He tried to scream for help, but in vain; nothing but a faint gasp came with his best trying.

“Mamma!” he at last managed to whisper.

“What is it, my pet?” answered his mother from the next room, who slept, as only mothers can, with one eye open; and in a moment was at his bedside.

“What’s the matter, Eddie? Want a drink?”

“O mamma, I had such an awful dream! I was riding on an elephant like the one I saw at the ’nagerie, and I am so thirsty.”

“Here’s some water, dear; now lie down and go fast asleep again.”

Eddie was not slow to obey; but still his little head was full of curious thoughts, that walked about like living things, and talked to him and made faces; at last they grew less fantastic, and took the shape of a story such as Rose had told him.

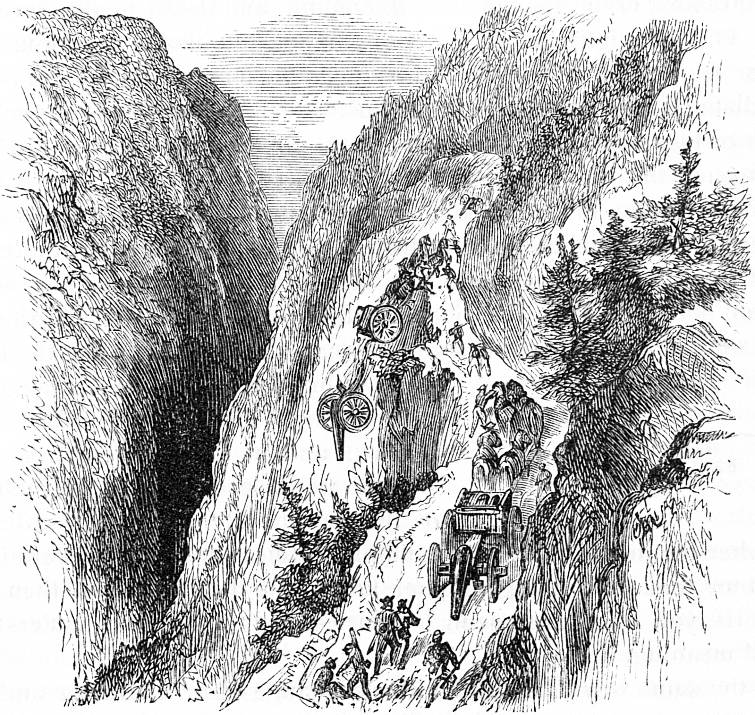

He was now neither monkey nor butterfly, but just “his own sef,” and he was walking alone along a narrow country road, not in the least like any place he had ever seen. There were rocks and mountains on one side ever, ever so high; no houses in sight, no cows nor trees nor chickens nor green grass, such as he sees in the country where he goes in the summer-time.

It was very lonesome and the way was long, and his feet so tired and cold; where was he going, and, above all, when should he get there? He would have cried, only he had never cried in a dream and he didn’t know how. All at once the road came to an end, or at least it came to a mountain, which is very nearly the same thing.

“I must never turn back,” thought brave little Eddie, “let what will come; up this mountain I am bound to go!”

So he began to climb, and as he climbed he made a discovery. The mountain was not rock, not stones, not dirt; it was not a mountain at all, but an enormous pile, reaching to the very clouds, of buckwheat cakes! Of every size and in every shade of brownness, thick and thin, turned and unturned; only all perfectly round and laid one upon the other with the utmost regularity. Although very hungry, Eddie did not dare touch one for fear the whole mass would tumble into the sea below. He was also thirsty, and seeing a stream flowing down the mountain-side, he was about to stoop and drink, when lo! it was not water, but batter,—batter for cakes! So he was forced to go on, weary and hungry and thirsty. His little feet ached, for climbing up a “natural staircase” of that sort was no easy performance; he would gladly have lain down; but such a bed! it was not to be thought of. Just as hope was at its lowest ebb in that little dyspeptic breast of his, a castle rose to view. (Rose’s stories always had a castle.) The sight was welcome, though it looked dark and gloomy enough standing there in its sulky loneliness. Poor Eddie’s heart sank within him, but there was no help for it; he must ask for a night’s shelter, or perish with cold and hunger. He was spared the pains of asking, however, for a servant of the castle had seen him from a window in the turret, and made haste to make him welcome.

“Will your master ’low me to come in,” said Eddie, with his best manners, nevertheless much terrified at the frightful goblin-like countenance of the man.

“O yes,” answered he, “nothing my master likes better than little boys,—little boys that are tender and juicy,—(I mean gentle and well-behaved.) So come in, my little man; your hard day’s journey is at an end.”

These words, apparently kind, were said with a leer of double meaning, so cold and cruel that Eddie fairly trembled in his balmorals.

“But,” the man continued, “you haven’t asked who my master is; did you ever hear of the Giant Griddle-Magog in the story of Jack the Giant-Killer?”

“O yes,” said Eddie, his heart in his mouth.

“Well, my dear, that Jack was an impudent boaster; he never killed the Giant Griddle-Magog, for he lives in this very castle, and he does not eat hasty-pudding any more, but cakes,—buckwheat cakes! B-u-c-k-w-h-e-a-t C-a-k-e-s. Do you hear, little hop o’ my thumb? B-u-c-k-w-h-e-a-t C-a-k-e-s!” And here he went off into such a frenzy of impish laughter that Eddie almost swooned on the spot.

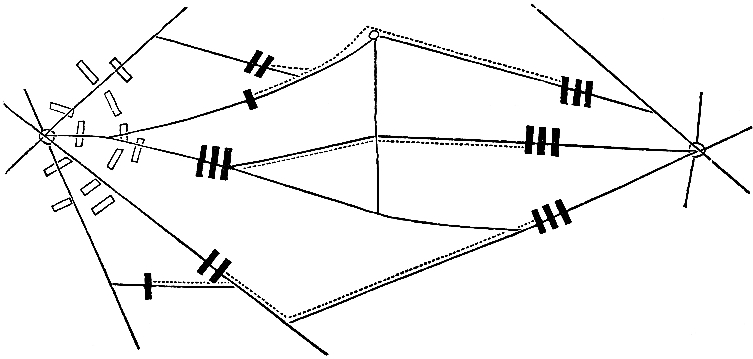

In the castle all was a hurly-burly of odd sights and strange noises, bangings and moanings as of the wind, rumblings and indistinct talking, with now and then a word or a mocking laugh coming up, as it were, to the surface. The fire smouldered in the huge chimney; ugly bats flew headlong in the dim recesses of the vast hall, and the hunting dogs growled and snapped in their dreams, as they rested from the fatigues of the chase. Altogether it was a terrifying place for a little spoiled child to find himself in, and Eddie could not help thinking how much nicer it was to hear a fairy story than to be in one. Suddenly a door swung back with a clang, and in came half a dozen burly men, who kicked the hounds yelping from the hearth, and threw logs upon the dying embers. Then they drew forth the rude tables to make ready for supper.

“The master is hungry,” roared one to the cook, “are the cakes stirred up yet?”

“All ready,” answered the cook, “but the boy was not so good as he might have been.”

“The boy,” thought Eddie, “what has a boy, good or bad, to do with cakes, except to eat as many as he wants?” But he was too busy watching the proceedings to give further consideration to the matter.

“What’s this?” exclaimed one of the men, coming up to him. “Odds bodkins! what a wee chap, to be sure! Trot out, little one, let’s see thy paces!” At this address, in a threatening tone, Eddie turned as pale as death.

“O, let him be,” said the other, who had brought him into the castle, “it is not his turn yet. He came in for a night’s lodging.” At this a horrible wink went the rounds of the party, who all joined in a mocking, giggling chorus.

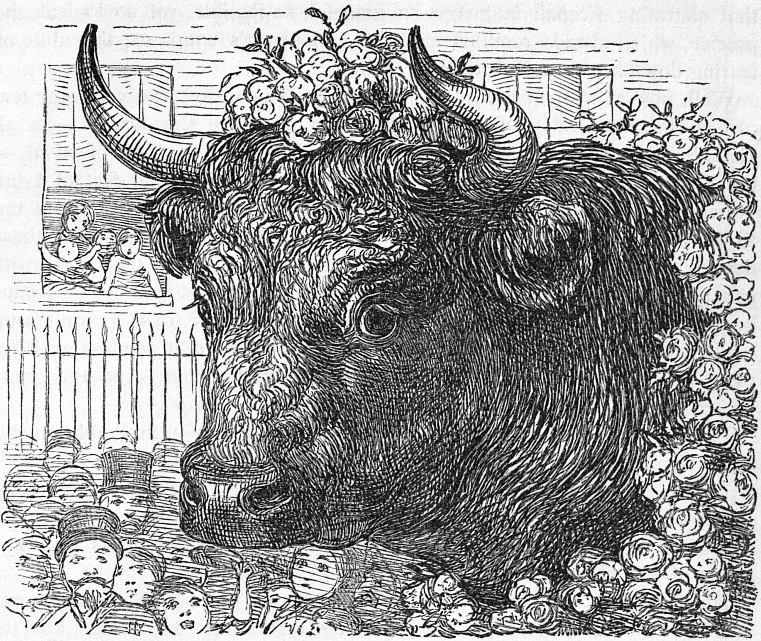

Presently, when the lighted torches flared about the hall, and the fire leaped madly up the wide chimney, a blare of trumpets announced the approach of the terrible Giant Griddle-Magog! With heavy strides and ponderous puffs this awful personage stalked into the hall and threw himself down upon the seat of honor at the head of the table. Everybody who has read Jack and the Beanstalk knows how a Giant looks; so what use in describing him? Eddie now knew that the half had never been told him of the ferocity and hideousness of such a monster.

“Let the cook come in!” thundered Griddle-Magog. The six men rushed all together to the door, and all six roared, “Let the cook come in!” Forthwith a fat, chunky fellow, humpbacked and with little round eyes glistening like beads, a fiery red head surmounted with a tall white paper hat, and body stoutly girdled with a white apron, came waddling in, preserving as best he could the dignity of carriage befitting his high position in the Giant’s household.

“What is it my lord’s pleasure to be pleased to order for his lordship’s supper?” asked the cook, bowing as low as his fatness permitted, and clapping on again his paper hat, as one would put an extinguisher over a candle flame.

“What indeed?” said the Giant in a tone of ironical rage; “one would think I had the fancies of a sick girl. Sirrahs,” he roared to the six servants, “what do I eat for supper? What do I always eat for supper?”

“Buckwheat cakes, your highness,” said the six servants in a breath.

“Bring the apparatus!” said the cook, majestically, and immediately the servants went out and presently came back, bearing between them a huge furnace of red-hot coals, a brazen griddle, and a spouted caldron full of batter that seemed to flounder about as if it were actually alive.

The cook rolled up his sleeves and began operations. The brazen griddle, six feet square at least, commenced to siss over the red-hot coals; it was well rubbed with a piece of beef-suet as large as a water-pail, and the caldron was raised by the six servants ready to pour out the batter at the given signal.

“Stop there!” thundered the Giant. “Is he young and tender?”

“I humbly hope so,” answered the cook with a profound obeisance. “Your lordship must be the judge, since who would dare touch your lordship’s morsel?”

“Be ready,” said the cook to the servants, “One! Two! Three! Pour!” And S-P-A-T-T-T! down came the batter till the enormous griddle was almost covered.

“How will they ever turn it?” thought little Eddie in his dim corner, and, in the excitement forgetting his fears, he drew near to watch the seething mass.

Horrors upon horrors! not a huge round cake, as he supposed, but a boy, kicking and frizzling and frying upon the brazen griddle!

“Turn him,” said the cook, with awful brevity.

The six servants, each with a long-handled implement, something like a spade, rushed one at the head, one at each foot, one at each arm, and one at the small of the batter back. Then, as before, “One! Two! Three! Turn!” and over he went, as nicely browned as one would wish to see.

In a few minutes the buckwheat cake was on the Giant’s trencher, but at the first mouthful fury possessed him. “Fire and fagots!” roared the monster, while the cook and the six servants quaked with fear, “am I to be made a fool of within my own castle walls? See that you get ready a supper worth my eating, or I’ll make a stew of your own miserable heads!”

“Your lordship, be pleased to consider—” began the trembling cook.

“Hold your tongue!” shouted the Giant. “I give you thirty minutes, while I smoke a pipe, to make ready. Young, juicy, tender, mind you, or off with your head!”

The cook smote his fat breast in despair; he even took off his paper cap and pulled his hair; but it hurt, and he suddenly desisted from that expression of his emotions.

The six servants, roused by the painful exigency of the occasion, had an idea,—that is, they each had one sixth of an idea, which they threw into the common mental fund.

They whispered into the ear of the frantic cook, who didn’t wait to neatly finish off his fine frenzy, but at once made for the corner where little Eddie stood breathless.

“He’ll just do!” exclaimed the cook, “and my life is safe for one more night. Come along, my fine lad! Kicking won’t mend your matters,—into the batter-pot you go!”

But for all that, Eddie kept on kicking, and from kicking he came to screaming; and scream he did, long and loud, till he found himself free from the cook and in the arms of his mother. This angel of sudden mercy leaned over him: “O my darling, what is the matter? James, come here, be quick; Eddie is very ill; you must go for the doctor immediately!”

“O mamma,” said Eddie, between his sobs, “such a frightful place I was in! and they were just going to fry me when you came! O dear! O dear!”

“Never mind, pet, you are all safe now!” (Aside to her husband.) “O James, look at the child’s eyes! He certainly has brain-fever, his head is like fire! Do be quick for the doctor, and call Rose.”

The next morning, when all anxiety was over, and the boy relieved by prompt treatment, Rose was suddenly overcome; she threw herself down at the foot of Eddie’s bed, and, between crying and choking off, confessed to his mother:—

“O Miss Sophie, all dis yer was my fault; it was all on ’count o’ my forgettin’ to make him say his prars yes’day mornin’. I didn’t call him back when he runned down stairs to breakfus’, an’ I had de imperence to say to mysef, ‘De good Lord’ll take care ov him fur one day anyhow’; and now all dis yer trouble jes’ come on ’count ov my wickedness, and, O dear! ef dat ar darlin’ chile had a-died, I never could ha’ forgived mysef, de longest day I lived; O my! O my!”

“Now, Rose,” said her mistress, by no means displeased by this affectionate burst, “just stop crying and hush your nonsense; the prayers and the good Lord had nothing to do with the matter. We nearly killed poor little Eddie with buckwheat cakes, and I hope it will be a lesson for all of us for the rest of the season.”

The next time that Eddie took his seat at the breakfast-table, a little pale and quite subdued, he looked longingly at the hot cakes that Aunt Dinah fetched in smoking from the griddle.

“Mamma,” he said, brightening with the idea deeply impressed by his Rose, “they won’t make me sick now, for I said my prayers this morning.”

His mother laughed: “My little boy, you don’t know what the good bishop said to the lady who had a great many little boys.”

“No, ma’am,” answered Eddie.

“Neither do I,” said his papa.

“Well,” he said, “that for certain things it is necessary to fast as well as pray.”

“What does that mean, mamma?”

“O, it means that you mustn’t eat any more buckwheat cakes, prayers or no prayers. What, tears! Does my little boy want to be fried, after all, by that horrid cook? I might not get there just in time another night, you know.”

H. L. Palmer.

The little village of Grünenthal lies in a deep valley through which a noisy stream comes roaring and leaping as if hurrying to escape from that gloomy forest on the mountain.

The stream bore no resemblance to those calm, peaceful English rivers that glide tranquilly on their way seaward, never speaking in a louder tone than a soft whispering ripple; not so this boisterous northern brook. The whole course of a river depends upon the start it gets in life. This one, for instance, did not begin by oozing quietly from the ground; it had no green fields for its cradle; its birthplace was high up on the wild mountain. Two huge rocks had once crashed together, and from between them sprung this stream. Other little rivulets are cheered along by grasses and flowers waving over them: this one had no such friends; indeed, if the bluebells did venture to spring up around, in their attempts to be sociable, they were soon driven off by his rough play. So his only companions all down the mountain were the cold gray rocks, and the mosses that cling to them through everything, and will not be driven away even when the rude stream drenches them with spray. They are stanch friends.

Above, the forest-trees tossed their bare arms, and moaned and sighed all winter long; and even when they had put on their green summer robes the little birds were shy of going near the stream; and when the village children, on holiday excursions, climbed the mountain and wandered through the wood in search of wild-flowers, it was always with the promise of keeping away from the stream.

It was so lonely and wild all through its course, and in the spring-time played such mischief with the fields and gardens in the valley, that the ignorant village people insisted it was not so much the inundations they dreaded, as the evil spirits who hovered round, and the water-kelpies lurking beneath its surface, who would surely lure any children to death who should go within reach of their charms. So it was feared and shunned by all the villagers.

More than half-way up the mountain, just on the skirts of the forest, and not so far distant from the stream but that if one paused to listen he might always hear it on its rushing way, there stood a very small, neat cottage. It was protected on the north from the too rough winter winds by jutting rocks; a bend in the road hid it from the village.

Perhaps there is nothing more aggravating to village curiosity than a solitary house whose owner holds himself aloof; a house occupied by mysterious people, if it is actually in the village, is a constant gratification; for the most secluded appear at times, and give material for gossip. But situated as this cottage was, so distant and retired, none but a professional Paul Pry could watch it. All that the villagers knew was that some years before the cottage, having long stood vacant, was repaired; and one night about sunset a lady was seen with a baby in her arms walking up the mountain road. Moreover, one of the village gossips, anxious for further discoveries, followed her at a distance, saw her enter the little cottage and close the door. Unfortunately, the lady’s veil was dropped, so that her face could not be seen.

Ever since, she had lived there alone, receiving no friends, nor visiting any; seldom seen in the village except on Sundays, when she regularly attended mass in the village chapel, bringing the child with her, and always wearing a veil as at first. She gave liberally to the poor, and the little boy was more richly dressed than the neighbors’ children, so the most groundless stories were started of her enormous wealth; many felt sure she was a princess in disguise. Finally, after racking their brains to account for the lady’s simple, quiet life, they wisely concluded to go back to their own affairs, and wait for further disclosures.

Let us, too, take a look at the cottage. Outside the December winds are whistling, and the snow whirling down as if the whole winter were not before it; already enough has fallen to bury the path leading to the door, as well as the leafless stems of bushes growing under the windows; almost every moment trees in the forest are heard snapping and are overthrown by the storm.

Within, the scene is less dreary. A bright wood-fire is crackling merrily. The room, though neat, is scantily furnished. If the village gossips could look in, they would be at a loss to find signs of wealth; indeed, the only indication of it is a richly illuminated book lying upon the table.

The lady who has excited so much curiosity is sitting before the fire, very different in appearance from the common people of the village; her features are delicate; the soft, dark hair, and deep black eyes heighten the paleness of her face; she would look haughty except for those sad lines round her mouth. The little boy sitting in her lap has thrown one arm around her neck, which he affectionately draws closer every few moments, at the same time covering her face with kisses. He is a rosy little fellow, with long light curls falling on his shoulders, resembling his mother only about the eyes.

The short winter day has already closed, and the only light in the room comes from the blazing pine-knots.

After one of his most loving embraces, the little boy breaks silence: “Mamma, will to-morrow night be Christmas eve?”

The lady nods assent.

“And, mamma dear, I have been a very good boy; will you take me to the village, as you did last Christmas eve, and let me go to the doors and sing a carol; and then perhaps the good people will call me in again to look at their lighted Christmas-trees. Do you remember how one little girl asked me if I was the Christ-child?—say, mamma.” And he gave her another hug to gain her attention, for she had all the time been looking fixedly at the fire, without seeming to notice his appeal. The last embrace recalled her; she put him down and walked to the window. After looking out a few minutes, she replied,—

“I fear the snow will be too deep after this storm”; and added to herself, half aloud, “How noisy the kelpies are to-night!”

Apparently not wishing to draw the child’s attention to that subject, she took up the illuminated book, resumed her seat, and said,—

“Come, Carl, let me see how well you can sing the carol, and then I will show you these pictures!”

Much pleased with the suggestion, he stationed himself beside her, and began singing in a sweet, childish voice one of those touching Christmas ballads so common throughout Germany. As his voice rose and fell, it seemed to drown the fury of the storm; and as he ended, a ray of light struck the floor, from the moon just struggling through the clouds.

When Carl opened his eyes the following morning, he found that the sun had got the start of him. All traces of the storm had disappeared, except that branches torn off by the wind lay scattered upon the ground; all the roughnesses of the valley and mountain were hidden under the sparkling weight that rested upon it.

Those who live on the mountains must be early risers. Accordingly Carl was out of bed and dressed at about the time children in the valley would wake: then having despatched his bread-and-milk, and added to his mother’s prayer for protection from the malice of all evil spirits a request that the Christ-child would forgive his sins, and visit him and all good children, he begged his mother’s permission to go to the forest and play in the snow.

He ran off gayly, singing snatches of the songs she had taught him. Now he moulded the snow into little birds, and again fashioned it into a beautiful figure, like his mother’s description of the Christ-child; he clapped his hands with delight to see how it shone in the morning sunlight.

So he wandered on, forgetting all but the charming sights around him. On a sudden he came to the stream; how innocent it looked! It sparkled in every drop as it leaped from rock to rock: glittering icicles hung all around in every fantastic shape.

Carl was charmed; it did not seem the same river that he had seen before, so dark and swollen. Heedless of all his mother’s cautions, he climbed nearer and nearer. The falling spray froze and dropped just below him in a sparkling star;—he scrambles to reach it over the slippery rocks; in taking it, one foot dips beneath the water.

That instant a thousand cold, watery hands seize him and bear him under, struggling and sobbing. Stupefied with fear, they hurry him on against the tide, beneath fallen trees and through gloomy caverns, which he is too unconscious to see; up, up, till they reach the source of the stream, an ice palace, and there yield him to their princess.

This tiny, cruel princess was a niece of the good old elf Santa Claus; but she did not in the least resemble him, either in appearance or disposition.

How such a sensible old fellow, and one who requires such model conduct in children, should ever have indulged and spoiled this niece is a mystery! She had not the most senseless whim ungratified; and though he himself was so rough, and dwelt in such a rude underground retreat, he allowed this little lady to live in the most extravagant style, and had caused his workmen to build the most exquisite palace for her gratification.

It was certainly a remarkable specimen of architecture. Ice-covered branches supported the curious crystal arches of the halls; the stone pavement was covered with frost-work in forms of the most delicate leaf-tracery. The walls were built of the clearest, coldest ice. Crystal cascades adorned some of the apartments. The pictures and most of the ornamental work were executed by a distant cousin of the princess,—a famous artist, known to mortals as Mr. John Frost.

Santa Claus not only bore the original expense of the building; he was also obliged to keep workmen constantly busy repairing damages caused by the heat of the sun.

Within the palace all was cold and glittering; the little princess always appeared in a snowy robe, and her only ornaments were the purest crystals.

It is hard to tell how she employed her time, day after day; she had nothing to do but to amuse herself, which is, to be sure, the most difficult task that can be set any one. Almost every night she gave a great ball; and through the day she wandered about her palace, trying to think of some new pleasure.

She finally decided that she would be happy if some mortal child could be stolen and brought to her; so she had offered a prize to any one of her subjects who should gratify her desire.

She had waited in vain until now, for her province only embraced a narrow strip of land all down the stream; and all the children shunned it till this time, when poor Carl had ventured too near, enticed by the sparkling waters. That was the reason that the kelpies had been so eager to seize him.

The child lay on the palace floor half dead, and all the curious little people walked around to look at him. When they had rubbed him, and dried his clothes out in the sun, he revived, and saw the tiny princess, with her icicle sceptre, standing there and looking at him.

“Sing,” she said, imperiously. The treatment he had received was not likely to make him feel like singing; still, all bewildered, and wondering if he were looking at one of the Christmas-trees in the village, he began to sing a little carol. When he reached the name of the Christ-child, the little princess grew very angry, and shook her head at him.

Then Carl remembered how he had fallen into the water, and what his mother had told him about the wicked elves.

Sobbing and crying for his mother, he tried to run from the hall, but a guard of little people held him back.

When the princess saw that nothing would content him so long as he thought of home, she commanded some of her wise subjects by their magic arts to rob him of his memory. Desirous to obey her, they stole away one by one every remembrance of home and his mother.

He grew with the years in body, but not in mind; that had been dwarfed by their evil arts. The princess made him sing to her all the songs he knew, again and again, but never would listen to the Christmas hymns. After a time she permitted him to stray outside the palace, sure that he would not seek to return home.

There is no need to tell of his mother’s anxious waiting for Carl’s return that Christmas eve; of her frantic search for him through the forest and over the mountain, until she traced his footprints in the snow to the edge of the stream; or of the wonder of the village people who now saw her come and go alone.

She sold every costly possession, except the illuminated book, and gave the money to the poor; she seemed to take comfort only in wandering through the forest where Carl had played.

Once, after many years had passed and her step was growing feeble, she had climbed the mountain higher than ever before, when she came upon a man sitting on a stone, his lap filled with wild-flowers, which he was pulling to pieces and scattering on the ground. His long soft hair reached half down his back, and his beard swept the ground; his face was turned from her; and she thought, “It is the crazy old man whom the village children fear.” Suddenly he began to sing in a low voice Carl’s Christmas carol. Unable to restrain herself, while the tears rolled down her cheeks, she joined in the song as she had been used to do; he looked up, startled, and cried, “Mamma!”

The little cottage looked cheerful again, as the mother sat before the fire, with the childish old man, her son, sitting at her feet, his head resting on her lap.

“Mamma, do you think the Christ-child will come this year? He never came before, and I have tried to be a good boy!” But almost before he had finished speaking, he had forgotten his question, and lay gazing vacantly into the fire, while his mother gently smoothed back the hair from his forehead.

That night, just before the dawn, the old man saw the beautiful Christ-child enter, and heard the sweet voice that had haunted his dreams calling him; he answered, “Thou hast come at last; but I must not leave my mamma again; we will take her with us.” And the Christ-child heard his prayer.

When the priest had watched in vain for the strange lady the following Sunday, he made bold to climb the mountain and knock at the cottage door. No answer came, and when he lifted the latch no sound of welcome greeted him. He trembled nervously, fearing that the evil mountain spirits had been at work; but his apprehensions were calmed when he saw the illuminated book lying on the table, open at the story of the Christ-child.

After a time the cottage was torn down, the ground sprinkled with holy water, and on the spot a little shrine was placed where all who are climbing the mountain may stop and ask protection; where the children of the village always hush their mirth, and offer a prayer as they go and come from their rambles.

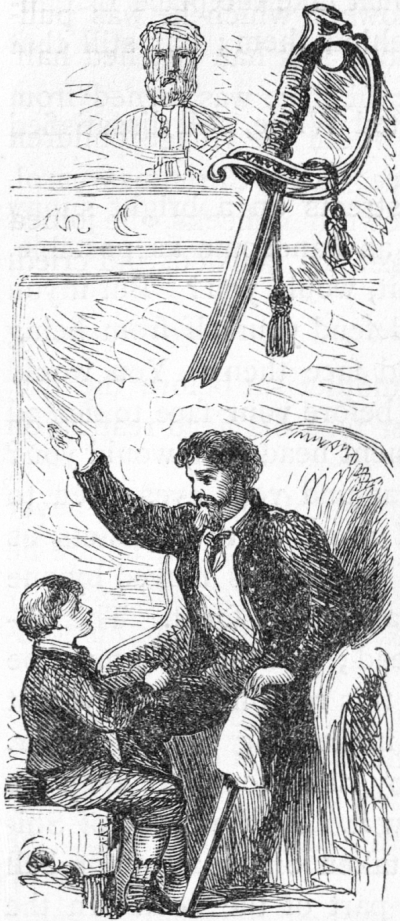

“Papa, why don’t the generals in the army get killed in battle?”

It was Willie Blake, whom you have possibly met before, who asked this curious question. He was rather fond of asking odd questions, as you may remember; and this one rather surprised his father, to whom it was addressed. As he asked it Willie looked up from the book which he had been reading and caught his father’s surprised look.

“Why, Willie,” replied his father, “what do you mean? There were a great many generals killed in our army. Don’t you remember there was General Lyon and General Kearney and General McPherson and—”