* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

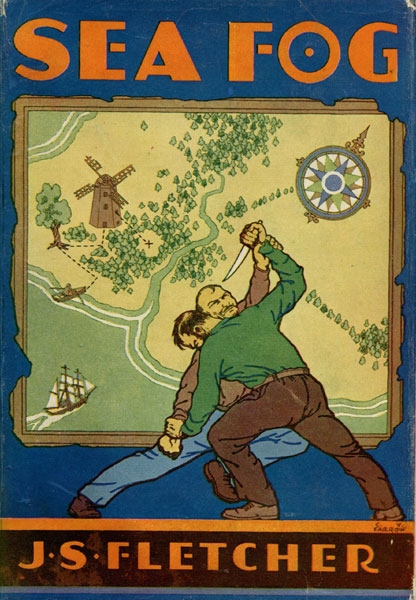

Title: Sea Fog

Date of first publication: 1925

Author: J. S. (Joseph Smith) Fletcher (1863-1935)

Date first posted: Feb. 24, 2016

Date last updated: Feb. 24, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160230

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

SEA FOG

WHAT THIS STORY IS ABOUT

Tom Crowe, sheltering for the night in a disused windmill on a Sussex down overlooking the sea, witnesses a brutal murder, which he is powerless to prevent. A series of extraordinary and baffling mysteries follow, all springing from a dark and tragic crime committed forty years before.

Trawlerson, a mysterious seaman seeking for treasure; Chissick, an ex-convict; Preece, a village policeman; Halkin, the subtle and sly; are all mixed up in the plot. And Parkapple of the C.I.D., a man of fame and skill, handles the case. A story of sensations and thrills.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

| THE MARKENMORE MYSTERY | 2s. 6d. net. |

| THE MAZAROFF MURDER | 2s. 6d. net. |

| THE CHARING CROSS MYSTERY | 2s. 6d. net. |

| THE MILLION DOLLAR DIAMOND | 3s. 6d. net. |

| THE MYSTERIOUS CHINAMAN | 2s. 6d. net. |

| THE SAFETY-PIN | 7s. 6d. net. |

| FALSE SCENT | 7s. 6d. net. |

SEA FOG

BY

J. S. FLETCHER

HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED

3 YORK STREET ST. JAMES’S

LONDON S.W.1 MCMXXV

Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd., Frome and London

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

Sea Fog

I’ll say at once that Mr. Andrew Macpherson, the Scotch grocer of Horsham, from whose shop I walked out to a glorious and unexpected wildness of liberty and adventure the morning on which this story properly begins, was a man in a thousand, for it was he who, at his own suggestion, threw wide the door of what I had come to consider a prison-house, and cheered me on my way with a word and a smile, instead of helping me across its threshold with a hearty kick.

Most other men would have considered me deserving of that kick; five out of six might have given it. For Mr. Macpherson had been a fine friend to me; he took me to his hearth when I was left a defenceless orphan lad of ten years old; he gave me a good schooling; he tried to teach me his own business. I picked up the schooling readily enough, but not the grocery trade; the buying and selling of that stuff made no appeal to my nature. And on the particular morning I speak of, Mr. Macpherson himself reluctantly arrived at the same conclusion. I forget what I had been doing; maybe I had mixed green with black in undue proportions, or sent the parcels to the wrong places; but anyway, the good man looked at me with a sorrowful shake of his head, and let out a heavy sigh.

“Man Tom,” said he, “I’m thinking ye’ll never do any good at the grocery! It’s a peety, but ye’ve no intellectual inclination to it!”

“I’ve been thinking that a long time myself, Mr. Macpherson,” I answered him. “It’s not my line; I don’t like it. And I’d have said so before, but for the fear of hurting your feelings.”

“Aweel!” he said, with another sigh. “Ye’re eighteen years of age, my lad, and I’m not the sort to stand in any young fellow’s way. What is it ye want to do, Tom?”

“Mr. Macpherson,” said I boldly, “I don’t want to be fastened up in a shop! There’s times when I can’t breathe! I want space!”

“Ye’ll be for going out and seeing the world?” he suggested. “Aye!—it’s in yer blood, my man! And where would you be for setting your face, now?”

“Anywhere there’s ships and sailors, and the sight and smell of the sea, Mr. Macpherson,” I told him. “Portsmouth—Southampton—Plymouth—any place the like of them! I want adventure!”

There was more said between us, much more; all kindly and sympathetic on his part. And the end of it was that within an hour I was in my best clothes, a bag in my hand, and ten pounds in my pockets, standing in the street—free! There was Macpherson’s blessing in my ear, and the grip of his big hand was warm on mine, but I never as much as looked back at the shop. That life was over.

It was a beautiful May morning. There was the sharp zest of the new springtide in the air and the smell of flowers in the streets; above the old roofs and chimneys there was a wondrous blue sky, and for one who had just emerged from the gloom of an ill-lighted shop the blaze of the sun was like an illumination from heaven. It was the sunlight more than anything that made me suddenly change my direction. I had taken my first steps of liberty towards the railway, intending to travel in that fashion to Portsmouth. But the sun, and the spring air, and the smell of growing things, reminded me that I owned an unusually strong pair of legs—why ride in a stinking railway carriage when I could foot it, at my own pace, across the hills and downs of Sussex?

I turned sharp in Carfax, and instead of going north, went away across the stream by the old church, and, choosing footpaths rather than highways, made boldly for the open country to the south.

Already I had a very definite notion of what I was going to do. I would strike for Portsmouth, by way of the South Downs, taking my time and looking about me. If I found nothing that appealed to me at Portsmouth, I would go on to Southampton by way of the coast. I was well prepared for a journey of that sort. Eight of the sovereigns with which Mr. Macpherson had presented me (for this was in the days when we were as familiar with gold as we now are with paper) were safely stowed away in a leather belt worn under my shirt; another was hidden in a waistcoat pocket; the tenth, changed into silver in the shop as I left it, lay in my trousers. And I had not lived with and been brought up by Mr. Andrew Macpherson all these years for nothing!—it was my intention to look well at and think long over every sixpence of my silver before parting with it. I had no fear of travelling expenses; Macpherson himself had shoved into my bag enough eatables to last me all that day and most of the next, and I was one of those lads who have no taste for cheap cigarettes or for drink. I reckoned as I walked along that I should have made small inroad on my silver by the time I reached Portsmouth; as for breaking into the gold in my belt, I took that to be a necessity which I meant never to acknowledge. It was my ambition, or, rather, my firm resolve, to present myself in a year or two to Mr. Macpherson once more, in the proud position of being able to show him that his one-time mouse had been metamorphosed into a man.

I went along all that day, my bag slung over my shoulders, through the Sussex villages, taking my time, rejoicing in my liberty, breathing the good air that increased in savour and quality the nearer I drew to the downs and to what I knew lay beyond their swelling outlines—the bright waters of the English Channel. But I was not to see those waters that day. By the end of the afternoon I had come to Petworth, at a distance of fifteen miles from Horsham, and, stout as my legs were, I was beginning, as they say, to know that I had feet at the end of them. That place, Petworth, had its charm, and, chancing on a little shop kept by a widow-woman whereat you could get a cup of tea, I turned in, and, finding the owner a motherly and come-at-able person, bargained with her for my supper and my bed and my breakfast next morning, all for two shillings.

It was still but the middle of the evening when I had eaten my supper, and the light being good, I went out to see the place, and it was while I hung around the old church, wondering at its queerness, and, as I thought, its ugliness, all the stranger because of the picturesqueness and charm of its surroundings, that a man came up and asked me, without preface, if I was well acquainted with that quarter of the country.

Having acquired a good deal of caution during my tutelage under Andrew Macpherson, I took a precise observation of this man before replying to him. He was a middle-aged man by appearance; a good fifty, no doubt, and already grizzled in hair and beard; a man, I fancied, who had lived much under strong winds and fierce suns. What with his brown skin and his blue cloth, and a rolling gait that he showed as he made up to me, I set him down as a seafarer. That inclined me to him, and I spoke, though, to be sure, it was but one word.

“No!”

“Stranger, then—like me?” he asked.

I nodded. Mr. Macpherson had taught me never to waste tongue-power when a gesture would serve the purpose. But the man persisted.

“Just so!” said he. “And which way are you from, now—did you come in here from north or south or east or west, young fellow?” Then, seeing my distaste, he went on hurriedly: “No offence, my lad, and no foolish curiosity!—I’ve a reason for asking. The fact is, I’m searching for something, and, d’ye see, you may ha’ seen it, in which case——”

“What are you looking for?” I asked abruptly.

Before answering, he drew out a brass tobacco-box, on the lid of which I noticed a curious design, and, taking a plug of tobacco from it, cut himself a quid with a clasp-knife, and stowed it away in his left cheek. It was not until he had put box and knife away again that he answered my question.

“To be sure!” said he. “That’s nat’ral! You couldn’t tell me anything if I didn’t tell you something. Very well!”—here he paused and looked about him, suspiciously, as if there might be listeners amongst the old tombs and yew-trees around us—“very well, I’ll tell you! A mill!”

I dare say I looked at him as if I suspected his sanity, for he shook his head.

“Queer, no doubt, young fellow,” he said hastily. “Queer you think it, and maybe queer it is! But—a mill! Not one of these here new-fangled mills, all steam and machinery; nor yet a water-mill. A windmill, d’ye see?—that’s my object!”

“There are a good many windmills in Sussex,” I remarked. “I’ve seen a fair lot myself, here and there.”

“That’s the devil of it!” said he eagerly. “It’s which of ’em is which! However, this here is like that game the children play, when one hides some little thing, a thimble or what not, and t’others seek for it, and him what’s hid it tells ’em if they’re hot or cold, according as they get nearer or farther. I reckon I’m getting hotter, for you say you’ve seen many mills hereabouts—windmills! Now, have you ever seen, do you know of, a windmill, very old, unused, what stands, all by itself, on top of a lonely down?”

“No!” said I.

He let out a heavy sigh, as if very seriously disappointed; but in the next moment his face became brighter again, and the old, eager look came back.

“Just so—exactly—you haven’t!” he said. “But, to be sure, you admit you’re a stranger, and what you mean is that you know such mills in your parts, and there ain’t such a mill as that I’m a-describing of. Now, without offence, what might your part be?”

“Horsham!” I answered.

He shook his head with a gesture of satisfaction.

“Ah!” he remarked. “Horsham? That’s all right!—wherever else it was, it wasn’t Horsham! Horsham isn’t in the down country—no! I’m thankful, truly, to hear you say you come from Horsham. I was afraid you was from the southward.”

“What do you want to find this mill for?” I made bold to ask.

He had very small eyes, this man, and they seemed to grow smaller when I asked him this question. Once more he shook his head, but this time in different fashion.

“Ah!” he replied. “And you may ask! But for a good reason, young fellow. ’Tis a sort o’ landmark, d’ye see? A—well, a thing to steer by!” He took off his cap and scratched the top of his head with his stubbly fingers. “Ah!” he went on, “I ha’ used the sea a deal in my time, and I ha’ known hours when I’d ha’ given much to see a sail, or a light, or a star in the night-sky; but I’d give as much now to see that there mill as we’ve talked about, and I’m getting uncertain as to where it lies, for blame me if I can hear tell of it!”

“Are you sure it’s in Sussex?” I asked.

But even as I spoke the man was off, and, whether he heard me or not, he never looked round. I watched him curiously as he made his way out of the churchyard, and I fancied that he talked to himself. At that I came to the conclusion that he was probably a little mad, and had got his deserted windmill on the brain, and the affair being none of my business, I put it out of mind and attended to my own, which was to go back to the little shop and to bed, where I slept so soundly that it was nearly eight o’clock next morning before I woke, and by that time I had forgotten windmill and man.

But I had the man brought up again before noon; to be exact, I saw him again. By noon, wandering across-country in the same fashion as before, but, the day being very hot, not making such progress as at first, I had come to the very foot of the downs, which now rose up in front like a great green rampart. My precise location at this hour was the village called Graffham, right beneath the vast woods that stretch from Heyshott to Lavington. There I sat down on the roadside in the middle of the village, under the shade of a tree, to eat my lunch of bread-and-cheese, and while I was eating I saw, coming along the road which I had already traversed, the man of Petworth churchyard. He had his hands in his pockets and his head down, and once more he was talking to himself.

There was an inn nearly opposite to where I sat; the man caught sight of it, and straight-way turned into its open door. He was in there half an hour; when he came out again, a couple of rustics came with him, evidently to direct him. They pointed him to the south-west, and when he left them he went in that direction, taking a narrow lane, and presently I saw him no more. I had no doubt that he had now heard of his windmill, or of a windmill, and was making for it. He passed within twenty yards of me as he left the village, but he never saw me, and I had no mind to hail him, and when he turned his corner the only thought I had of him, if I had one at all, was that he and I had now definitely parted. For while he was making for the south-west, and so keeping to the land, I was intent on a due south course, that being a straight one for the sea.

I made up through the overhanging woods after my rest, and over the crest of Graffham Down, and again into the woods on the other side of the tableland. These woods were thick, deep, far-stretching. I got lost in them, and I spent most of the afternoon in endeavouring to right myself. When at last I got out of them, it was only to entangle myself in others still farther ahead. Evening had come on, and twilight was gathering, when, after much casting about (for I had somehow lost any real path), I emerged on an open space of moorland. And the first thing I then saw was the open sea, shining faintly far ahead of me, miles away, but clearly discernible in the glimmering light. The second, outlined against the shimmer of sea and sky, was a black, gaunt shape, suggestive of vague mystery, perched in strange isolation on the bowlike surface of an arching down.

This, whatever it was, was still a long way from where I stood. But as it was in my direct line to the sea, I made for it. I dipped down into a valley and lost sight of it. I climbed the other side of the valley and saw it again. But then came more deep woodland, and by the time I had traversed that the twilight was rapidly merging into darkness. I got out of the wood at last; there was the thing right above me, clearly outlined against the sky. I thought as I climbed the hill-side towards it that it was a tower, but as I drew nearer and nearer I knew it for what it was—an ancient windmill. And I knew, too, that I had found what the stranger-man was looking for; this was his mill, the thing he wanted. But he wasn’t there; nobody was there. It seemed to me just then that beyond the mill and myself there was nothing in the world.

It would have been strange if this impression of utter solitude had not forced itself upon me, for—at that time of advanced evening and under those circumstances—my situation was one of entire loneliness. There were the deep and silent woods through which I had passed; here was the bleak plateau on which I stood. At first I saw nothing near by, nor in the distance, to indicate life, and the silence was profound. But as I gazed about me this way and that I became aware of two or three twinkling lights at perhaps a mile’s distance, deep down in the low country which lay between me and the coast; they, of course, suggested the presence of some village or solitary farmstead. And after a while, as I stood looking seaward, I saw a trail of flame coming along rapidly from west to east, not far away from where I judged the coast to be; that I knew for a railway train, speeding along the line that ran parallel with the coast itself. So there was life near at hand. Yet, none there; that place was the loneliest, and most curiously suggestive of loneliness, that I had ever been in. But even then, as I realised this, there came companionship; a nightjar went by, uttering its strange note, and as that died away amongst the neighbouring woods a nightingale suddenly burst into song in some coppice down the hill-side.

While I had stood near the mill, staring about me, a full moon had been steadily rising, and had now got to a fair height in the south-east sky. I went closer and looked at the mill. It was a great, massive structure, and so high that I saw at once that it must form a landmark for miles around, and probably far out to sea; I saw, too, that it had evidently not been in use for many a long year. There were gaps in its masonry, the doorway gaped wider than it should have done; the remnants of the long, raking sails hung desolate. A shaft of moonlight lay within the wide gap of the door, and I went inside and looked about me in the gloom, and saw then that the interior was still pretty much as it had been in working days; there was machinery there, rusty and useless, no doubt, but still in place, and there was a wooden stairway that led to upper regions. I saw, too, that somebody had turned the place to account as a shelter; there was a quantity of dried bracken stored on the ground floor, together with other things which I knew to be used by shepherds in charge of flocks. Here, perhaps, the shepherds kept house while their charges browsed the hill-sides; it was a convenient place for that. And it suddenly struck me that it would make quite a good lodging for me for that night, and save me the necessity of exploring the village or hamlet in which I had seen the lights. I might not find anything there, and the next likely place might be a long way off. Here, at any rate, I was certain of shelter, and I had still enough food in my bag to serve for supper.

It was just as I had made up my mind to stay where I was that I heard footsteps. They were still some little distance away—perhaps fifty yards—but the turf was hard and dry and crisp on the top of that hill, and I heard their slow, regular fall quite plainly, and I sprang to the door and cautiously looked out. There, plainly seen in the moonlight, was the figure of a man coming towards the mill. He came from something of the direction in which I myself had come, but rather more, a point or two, from the north-west, and that fact immediately suggested to me that this was the stranger-man of Petworth churchyard, who, after I had seen him at Graffham, had wandered round until he hit on what he was seeking. Certainly the figure resembled his. . . .

I had to think with uncommon rapidity during the next few seconds. Did I want to meet this man again, and especially in that old mill? I knew nothing of him; I was not sure that I liked what I had seen of him. He had said that he would give much to find that mill; perhaps he would resent finding me in occupancy of it. Again, I had formed the idea that he was, or might be, somewhat cracked; if so, and he happened to carry a revolver or pistol on him, which was quite likely, he might take it into his head to rid me of his presence in unpleasant fashion.

The end of that brief spell of thinking was that while the man was still twenty or thirty yards away from the door, I sped up the stair, as noiselessly as possible. There was an open trap-door at the top; I passed through it into a wooden-floored chamber the interior of which I could make out quite well, there being a great gap in the outer wall there on the side from which the moon shone. And, standing well back in the shadow, I kept as quiet as a mouse and looked down through the trap, watching for the man to enter. There was some delay in that; evidently, having reached the place he wanted, he paused a few minutes to take a look at it and its surroundings; indeed, I heard him pacing about outside for awhile. But at last he came in through the ruinous doorway, and the moonlight falling full on his face, I saw at once that he was not the man with whom I had exchanged talk at Petworth.

Within another minute, whatever ground I might have had for uncertainty on this point was swept clean away. The man had no sooner entered the ground floor of the mill than he lighted a small but powerful lantern, and in turning it about here and there as if to examine his surroundings, he twice gave me a full view of his face; his figure I could see well enough in the moonlight. That was somewhat similar to the figure of the first man; both were solid, thick-set, shortish of height. But while the man of Petworth churchyard was bearded, the man of the mill was clean-shaven, save for a goatee beard which I took to be violently red in colour. He had the face of a rat, or a weasel, or a fox, or perhaps a mixture of all three; anyhow, he was an evil-looking customer, and I wished myself anywhere else than where I was, and cursed my own stupid foolishness for running up that stair.

Another moment and I cursed myself more than ever. For it became, nay, at once was evident that, like me, the man had made up his mind to make the old mill his quarters for the night. He set down his lantern on a ledge of the machinery that stood in the centre of the floor, and, unstringing a sort of knapsack from his shoulders, produced from it a parcel of food and a big bottle filled to the neck with some colourless liquid which looked like water, and was, of course, gin, with perhaps an admixture of water. Very fortunately for me, who stood in a somewhat cramped position at the trap-door, some idea occurred to him before he began his supper, and he hurried outside—I suppose to assure himself that there was nobody about. The instant he had vanished I sprang to some sacking, a pile of which I had noticed on coming into the loft, and hastily made a couch for myself, close to an opening in the floor through which a couple of great chains passed from above to below; thenceforward I was able to look down on my undesirable fellow-tenant from immediately above his head. And at the same time I made up my mind that if he put his head through the trap-door I would give it a crack with my oak staff—a present from Andrew Macpherson—which would make him see even more stars than the thousands which were already challenging the moonlight.

He came back after prowling around outside for awhile, and, settling himself comfortably on the piled-up bracken, he proceeded to eat and drink. He had cold meat and buttered bread, in generous slices, in his parcel, and he made great play with both by means of as ugly a knife as ever I saw, and one which he used with great dexterity. Also, he every now and then took a generous draught from his innocent-looking bottle; altogether, he struck me as being a man of good appetite. Not a wolfing man, though; he ate and drank leisurely enough, and left meat and bread in his parcel, carefully wrapping it up again and restoring it to his knapsack. Then followed exactly what I expected to see: he produced pipe, tobacco, and matches, and proceeded to smoke. I gathered from this that he anticipated complete freedom from any interruption of his tenancy, and that he considered himself as much alone as Robinson Crusoe on his island before he chanced on the footsteps.

I was by that time anxious about two things, and two things only—the first, that this goatee-bearded fellow wouldn’t take it into his ugly head to climb the stair with his lantern; the second, that he would finish his pipe and bottle and go to sleep, so that I also might. But he showed no sign of falling in with my wishes. For awhile he sat with folded arms, smoking, and—I presumed—thinking. Now that he had eaten his fill, the bottle did not seem to have any great attraction for him. But after some time, his roving eye chancing to fall on it, he drew it to him, took out the cork, and treated himself to a hearty swig, afterwards measuring the remaining quantity with an appraising glance, as if he were either reflecting on the amount he had drunk, or were thinking that it would be well to leave the rest for his next morning’s refreshment. I hoped he would knock the ashes out of his pipe then, and compose himself to sleep; instead, after putting the bottle away from him, he turned his lantern so that its full flare fell on the level surface of the machinery which he had used as a table, and, putting his hand into some inner pocket of his clothes, drew out a square packet of whity-brown paper.

I had been inquisitive about this man from the first moment of his appearance, but the sight of that packet roused feelings of curiosity to which my first speculations became as nothing. There was mystery in that, and I watched for all I was worth while its owner proceeded to unwrap it. There were many wrappings: first, the whity-brown paper aforesaid, with the appearance of which I was familiar enough, having wrapped up some thousands of small parcels in its like; then, a sheet of a better sort of paper; then, a piece of what undoubtedly was canvas; finally, a square of oiled silk. Out of the oiled silk he carefully took a folded paper, and, spreading it out very gingerly, laid it on the flat surface at his side, immediately in the glare of his lantern. I saw then that what he had before him was undoubtedly a map.

But it was not a map of the sort with which I had been familiar at school—an affair of careful engraving and colouring. It was what I then called a map; what it really was, I suppose, was a rough plan, or chart. From my overhead perch, I could not, of course, make it out; all I could see was a certain very conspicuous black dot in the very middle of the paper (which was about eight or nine inches square), some lines and marks, and, in one place, a cross, as conspicuous as the dot. These I saw, but there was more that I could not see, or, rather, could not make out—lettering, I felt certain.

The man remained poring over this chart for some little time; eventually he restored it to its wrappings as carefully as he had taken it from them, and put the packet back in its secret receptacle, which, I think, was in the lining of his waistcoat. That done, he knocked out the ashes of his tobacco, taking heed to see that no spark remained alive on the floor of the mill, and, having taken another pull at his bottle, he extinguished his light and curled himself up in the dry bracken. I could see him in the moonlight, all bundled together, his head on his arm, and before five minutes had gone I heard him snoring contentedly.

I did not go to sleep just then, but I went to sleep after a time. Until I dropped off, my brain was actively busy in wondering about what I had just seen, and in speculating on various matters connected with the man of Petworth churchyard and the man who now slept in the basement of the mill. Was there any connection between the two? What did the man of Petworth churchyard want with the mill? Why had this goatee-bearded, hatchet-faced chap come there? What was his much-treasured map about? What would he do if he found me there? Should I wake him if I stole down the stair and fled? I thought of fleeing for a time, but I was curious, and more than curious—I wanted to know what it was all about. The morning would bring light in more ways than one; I would wait till morning. And I went to sleep on my sacks and slept like a top—until I sprang into instant, keen-witted wakefulness at the sound of a scream.

I think my first notion was that this was the cry of some animal, trapped close by, or seized by another. But on the instant it came again, and I knew it then for the cry, desperate, terrorised, of a man in deadly fear and peril. I had sprung to my elbow at the first sound: at the second I looked sharply through the opening of the chains into the ground floor beneath me. The man of the map had gone; there, plainly outlined in the bracken, was the place where he had slept, but he and his bottle and his knapsack had vanished. And at that I jumped for the gap in the outer wall and looked out on a morning thick with milk-white mist. A great sea fog had rolled up from the coast and enveloped the plain and the hills, and from where I stood all the land was wrapped in its curling vapours. At first I saw nothing; then, a stifled cry coming again, I looked to my right, and there, some twenty yards away on the plateau, their figures strangely magnified and distorted in the mist, I saw two men struggling.

Two men!—but it was impossible for me to tell which of the two was my man, though I knew he was there. It seemed to me that one of the two had the other by the throat, and was endeavouring to force him to the ground. I could hear their pantings and groanings as they swayed this way and that. They were like two wrestlers, straining every muscle and sinew to throw each other, and for a time neither seemed to gain any advantage. They drew farther and farther away from me in their struggles; sometimes a curling of the mist wrapped them altogether; sometimes, as a strong shaft of sunlight hit their bending and twisting bodies, I saw them more plainly. It was in one of these sharp gleams of the sun that one suddenly mastered the other and forced him groaning to the ground, and in the same gleam that I saw the flash of something that shone and brightened as it caught the sun. There was a deep, horrible sound after that, and the next instant the man who had fallen was lying still, and the other was vanishing in the morning mist.

I suppose I stood there at the gap in the wall for several minutes, staring—just staring. But my brain was busy. Who was the second man? Was he the man whom I had seen at Petworth and again at Graffham? Had he come to the mill in the night, or in the early morning, found the other man there, and quarrelled with or attacked him? And which of the two men was it that was lying there, so awfully motionless? And would the man who had run away come back? Was he, perhaps, only a few yards away, hidden in the sea fog?

I waited awhile in the profound silence—then, unable to bear it any longer, and grasping my oak staff firmly in my right hand, I crept down the stair and out of the mill, and across the dew-besprinkled turf to the fallen man. It was he of the goatee beard, and he lay there with his arms thrown wide and his eyes glazed, and red blood was still running from the gash in his throat.

I took to my heels on making this discovery, running down the hill-side, through the mist, in the direction of where, from my remembrance of the lights of the previous evening, I supposed the village, hamlet, or farmstead to lie. I don’t think I stayed a second by the dead man; certainly—a matter that became of serious moment to me before long—I never made any examination of him or his clothing. He was dead!—dead as man can be—and my instinct was to run, possibly to get away from the sight of him, a truly horrible object, possibly to find somebody to whom I could tell what I had seen. The thing is that I ran harder than I had ever run before in my life. And as I ran, going in great bounds down the slopes, I heard, not very far below me, a clock strike six.

I ran, suddenly, out of the mist, upon level ground to find, in front of me, the house and outbuildings of an old farmstead, ringed about with tall trees. It was a fine old place, and at any other moment I should have paused to admire its quaint architecture, and the effect of the morning sun, now dispersing the sea fog, on its red-brick walls mellowed in tint by age, and here and there half covered by a wealth of ivy. But I was looking for human life—and in another moment, rounding a corner of the outbuildings, I saw it. There was an orchard there, at the foot of an old-world garden, and over its low wall a man and woman were talking; she on one side, he on the other. I took a hurried glance at both as I made for them. They were not young people. She, who had a basket balanced on top of the wall, from which she was throwing corn to the fowls on the stretch of grass beneath, was a tall, buxom, handsome woman of something near forty; the man, a big, loose-limbed, athletic-looking fellow, with the unmistakable air and bearing of the soldier about his bronzed face, keen eyes, and grizzled moustache, was still older. But even if these two were of middle age, or approaching it, I remember that I saw, in that quick inspection of them, that they were lovers.

The man was on my side of the orchard wall, and I hurried straight to him, and he heard me coming, and turned sharply, and I saw his eyes widen at the sight of me.

“Hullo!” he exclaimed. “What’s this? What’s the matter, my lad?——”

I realised then that my breath was spent by that headlong rush down the hill. But I managed to choke out a few words.

“There’s a man been murdered!” I gasped. “Up there—the hill-top. Knifed! I saw it! The—the other man’s run away.”

The woman made an inarticulate sound of surprise and horror; the man gave me a good searching look.

“When was this, my lad?” he asked. “How did you come to see it?”

I told them as briefly as I could; they listened intently, staring at me. The man turned to the woman.

“Send one of your men down to the Sergeant,” he said. “Tell him to come up to the old mill at once and bring help with him.” He turned to me as she hurried away towards the house. “I’ll go back there with you,” he went on. “What’s your name, my lad, and how did you come to be on the hill-top?”

“My name’s Crowe,” said I. “Tom Crowe. I’ve been in the employ of Mr. Andrew Macpherson, grocer, of Horsham——”

“Aye!” he interrupted. “I know Andrew Macpherson—I’ve served on a jury with him once or twice at Quarter Sessions. Well?”

“The grocery trade didn’t suit me,” I continued. “Mr. Macpherson and I agreed it would be more in my line to try a sea-life. So I set off for Portsmouth or Southampton, day before yesterday. The first night I lodged at Petworth; last night I came to this old mill, above here, at dusk, and I decided to sleep in it. Then this man came. I’ve told you the rest.”

“You didn’t hear the second man come?” he enquired.

“I heard nothing after I went to sleep until I heard the scream,” said I. “When I looked out, they were fighting—struggling together.”

“And you didn’t get any clear view of the second man?” he asked.

“I didn’t—the mist was too thick,” I replied. “And he was off, clean lost in it, as soon as he’d struck the other man down. He seemed to be a man of about the same size; a thick-set man.”

He made no further remark just then, and we went steadily up the hill-side until we came to where the dead man lay. The fog had cleared a great deal by that time; the plateau around the old mill was quite free of it, though it still lingered amongst the fringes of the woods on the northern side. And beyond the dead man there was nothing to be seen; he lay still enough, and, as far as I could see, just as I had left him. The man I had fetched stood gazing thoughtfully at him for awhile, but he made no offer to lay hands on the body.

“A seafaring man, this, by the looks of him,” he said at last. “And in a new rig-out, eh? New clothes, new boots, fresh linen—I suppose there’ll be some clue on him, but we’ll wait till the policeman comes up. Show me where you saw him sleeping.”

I took him inside the mill, and pointed out everything relative to the doings of last night. He looked curiously at the place where the man had slept in the bracken, and presently picked up a crumpled newspaper which lay near, whereon there were grease-marks. I remembered then that this had been thrown away by the dead man when he unpacked the meat and bread from his knapsack.

“Evening News of last night,” said my companion, pointing to the date. “That looks as if he’d come to these parts by train. Some strange mystery in it, my lad——”

Just then we heard voices, and, hurrying out of the mill, saw men coming up the hill-side. Two, obviously, were farm-labourers, agog with excitement; the third was a burly, round-faced man, half dressed, but with the unmistakable cut of the drilled and trained policeman about him. He was already stooping over the body when we joined him and his wondering companions.

“Strange affair this, Captain!” he remarked, with a salute to the man who had come up with me. “Pretty savage thrust that’s been!” Then he turned and gave me a look that seemed to take me all in. “This the lad who gave the information? Just so!—Um!” He bent down again to the body and began examining the clothing. His fingers, deft enough, went from pocket to pocket. “There’s nothing on him!” he announced, glancing up at us. “That is—this is all!”

He threw out on the turf a handful of loose silver and copper, a handkerchief, and the knife with which I had seen the dead man cut up his bread and meat. And at that I let out a sharp exclamation.

“Then he’s been robbed!” I said. “He’d more than that! He’d a packet, inside that waistcoat—an inner pocket. Look!”

He unbuttoned the waistcoat still more; he had already had his fingers inside it at his first examination, and he found the pocket I spoke of, but there was nothing in it. Gingerly, he drew off the man’s knapsack, which lay crushed half under his shoulders and side; there was nothing in it but some remaining bread and meat and the bottle, of which one-third the contents still remained. And at that the sergeant got up, brushed his knees, and gave me another searching look.

“A packet, eh, young fellow?” he said. “And how do you know that?”

“Because I saw it, last night,” said I. “He took a map out of it!”

“A map, eh? And of what?” he asked. “This part?”

I had realised for some minutes that my best plan was to tell this representative of the law the whole story of my adventures since my walking out of Andrew Macpherson’s doorway. For I saw that he was regarding me with a sort of suspicion, and being conscious of my own innocence, and of the fact that I had ten pounds on my person, I resented it. “I’d better tell you everything that I know,” said I. “I’ve already told this gentleman a good deal, and he knows a man who’ll answer for me—I’m no tramp, if that’s what you’re thinking, and I could have afforded to stay at the best hotel in Portsmouth last night if I’d liked!—I only slept in that mill because——”

“It’s just because you did sleep there that you’re a valuable witness!” interrupted the sergeant, with a smile at my companion. “And you’ll have to tell what you know at the inquest, my lad! If you like to tell us now, by way of rehearsal——”

“I’ll tell you everything from the start,” I broke in. “And gladly, for it’s my belief I know the man who did this! If you’ll follow me——”

I begun at the beginning—not omitting to mention my possession of the ten pounds—and told them every detail of my adventures since leaving Horsham to the moment in which I saw the murderer run away. Once, at an early stage of my story, the sergeant interrupted me to send off the two labourers for a horse and cart; thenceforward he listened with keen attention, especially when I arrived at the episode of the packet. And in the end he once more examined the dead man’s clothing, more thoroughly than before, eventually rising to his feet with a decisive shake of his head.

“There’s no packet on him now!” said he. “You’re sure he put it back in his pocket after looking it over last night?”

“Dead sure!” I answered. “He wrapped the whole thing up carefully, and put it inside his waistcoat.”

The man whom I had brought up the hill looked at the sergeant.

“The fellow who knifed him must have stolen it,” he suggested. “Probably that was what he was after.”

The sergeant jerked his thumb at me.

“But he says that the murderer made off in the mist, the very instant he’d knifed this chap!” he remarked. “The very instant!”

“He did!” I asserted. “That very instant! He’d no sooner knifed him—I saw the flash of the knife!—than he was off and clean gone—down there. I’ll swear that he never even touched him after he’d used his knife on him.”

The sergeant stood with his hands clasped in front of him, calmly regarding the dead man, for some minutes, evidently musing.

“You ran off as soon as this happened, you say, and came across this gentleman, Captain Trace, at the foot of the hill?” he asked. “How long was it before you got back up here?”

But I was not competent to answer that; my brain was still confused with the events of that first awakening.

“I heard the clock strike six just before I reached the house down there——” I began. Then I stopped, and Captain Trace finished for me.

“We were up here within twenty minutes, Preece,” he said. “And, of course, within twenty minutes——”

“You’re thinking just what I’m thinking, Captain,” said Preece. “Time for the murderer to come back and rob his victim, eh? Maybe! But if the murderer had no reason to think that there was anybody about, why didn’t he seize the packet at once?”

“Well, I wasn’t thinking that,” replied Captain Trace. “What I am thinking, now that I’ve heard more, is that within twenty minutes there was plenty of time for a third person to rob this dead man. Eh?”

Sergeant Preece started, rubbing his chin.

“Third person?” he said. “I don’t follow you, Captain!”

“No?” replied Trace. “Look at this man, now! That’s a very good, rather expensive suit of the best blue cloth; his boots are good; everything about him shows that he wasn’t wanting money. What’s the exact amount you found there in his trousers pockets?—nine shillings and fivepence-halfpenny, in silver and copper. I think he’d have more than that on him, Sergeant! And I think he’d have a good watch and chain.”

“He had a watch and chain!” I exclaimed, suddenly remembering. “I saw them on him last night.”

“Gone, now!” continued Trace significantly. “I think this man was robbed after his death, during the twenty minutes in which his body was left alone. Probably he’d money—notes, perhaps—in that inside waistcoat pocket, as well as his map.”

Preece made no remark about this theory, though I could see he was thinking about it. He pulled out a note-book and pencil and turned to me.

“That man you met at Petworth, and saw again at Graffham?” he said. “Just give me an accurate description of him. Make it close, now!—don’t forget anything.”

I gave him a faithful, even circumstantial, description, and by the time he had got it all down the two labourers were coming back with the horse and cart and another man. I watched them winding round the hill-side as I furnished Preece with the final details.

“All right!” he said, putting his note-book away. “Now, you’ll be wanted at the inquest. Where were you going—Portsmouth? You’d better stay here, in the village down yonder, until to-morrow—I’ll try and get the inquest opened to-morrow afternoon. You’ve money on you, so——”

“I’ll take him home with me,” said Trace. He turned to me with a friendly look. “Come along with me, my lad,” he went on. “I know Andrew Macpherson, as I told you, and I dare say I can help you to what you want in the seafaring way. Come to my place if you want him, Sergeant—or me, either!”

“I shall want both,” remarked Preece dryly. “First and second witnesses!”

We left him superintending the removal of the murdered man’s body to the village inn, where, said Trace, it would have to lie in an outhouse until the coroner and his jury could sit on it, and went down the hill by the way we had climbed it. But instead of going forward to the old farmstead where I had found him talking with the handsome woman, my guide turned aside through a path that led through apple-orchards to the centre of the village, stopping at last before a cottage on which, it was evident, a good deal of money and taste had been laid out.

“Half in ruins, this, when I found it!” he remarked, with a smile, as he opened the gate and motioned me to enter. “I did it up. How’s it strike you?”

I said that I admired it greatly, especially the garden, which was already beginning to be bright and gay with flowers.

“Aye, it’s not half bad!” he answered. “Well, come in, my lad, and we’ll have some breakfast. Murder is a beastly thing, and vile to see—but it won’t have spoiled your appetite!”

I was certainly at the age in which it takes a great deal to interfere with a healthy and growing lad’s appetite, and though I had been more than a little upset by the events of the morning, I was fully prepared to do justice to the breakfast which was presently set before my host and myself by a motherly-looking woman, his housekeeper, in a bright little parlour overlooking the garden. He was a tactful man, this Captain Trace; he not only made me feel at home with him, but kept off the affair in which I had just so unwillingly figured; instead of talking about that, he talked of Andrew Macpherson and my leaving him, and pretty soon he came to a direct question.

“So you want to go to sea, Tom Crowe?” he asked. “Made up your mind, eh?”

“I don’t want an indoor life,” said I. “There were times when I felt I’d burst, there in the grocery shop. Mr. Macpherson, he said it was in my blood.”

“Very like,” he agreed. “You’re not the sort to spend your time weighing pounds of sugar. Well, there is the sea. And there’s the Army. Ever thought of that, Tom?”

“A soldier!” I exclaimed. “No!”

“That was my line,” said he. “I was at a bit of a loose end when I was your age. My father had put me to the engineering—paid a pretty stiff premium, too, with me. But when my time was through—no work! Not a job to hand anywhere. And I wasn’t one for waiting, or idling. I took the Queen’s shilling—meaning to get on. Well, I did get on. Lance-corporal in nine, full corporal in twelve months; sergeant in two years. Then the Boer War came, and I got my chance—got my commission, you know. And in due time I got my company. Pretty good innings, eh?” he continued, laughing. “Raw recruit at twenty; captain at thirty. I might have been a general, or perhaps a field-marshal—who knows?—if I’d stopped in!”

“Why didn’t you?” I made bold to ask him.

He laughed again and made a wry face.

“Why, to tell you the truth, my lad, I got very badly wounded in the last stage of the Boer War, after I’d got my commission,” he answered. “And I’ve never really got over it. I carried on all right in peace-time, but the effects were there, and are there. And I had a bit of money left me, and so I thought well to give up soldiering and take to a quiet life—here.”

He said nothing then, and it was not until some time afterwards that I found out that when he got his wounds he also got the Victoria Cross.

“It’s very nice here, too,” I remarked, feeling it polite to compliment him on his situation.

“Yes, I took a lot of trouble to make it so,” he said. “It was a ramshackle old spot when I bought it. And I’ve got some fine prize fowls, and I keep bees, and I have a bit of a boat, a small yacht, as some folk would call it, down at Bosham—oh yes, it’s very pleasant, Tom, very pleasant!”

But as he said this he sighed, as if there was something behind the pleasantness; also, he became silent, eating his eggs and bacon with his eyes on his plate.

“Mr. Macpherson says my father was a sailor,” said I. “He was in the Royal Navy.”

“Ah!” he answered, looking up. “That accounts for your wish for the sea, no doubt. But if you want adventure, my lad, I think you’ll not get it there—nowadays. Travel, perhaps; but the good old days are gone. A fine, big sailing ship, now, trading to the far-off places——”

He checked himself at the sound of voices and footsteps outside, and both of us turning to the open window, we saw, coming in at the garden gate, two men, at sight of whom Captain Trace made a gesture suggestive of good-tempered annoyance.

“Tom!” he said. “Here are the two biggest gossips and tittle-tattlers in these parts—and that’s saying a good deal! They’re after you, my lad!—Preece has no doubt told them what’s occurred, and they want to see and question the eyewitness. Keep close!—don’t tell them anything—I’ll settle them. One of them, the big man,” he went on in a whisper, “is a sort of retired gentleman, name of Fewster; the other, the little man, Chissick, is a builder and contractor—and they’re both the sort who like news, and love to retail it. Say nothing!”

The callers were in the little hall by that time, and presently the housekeeper opened the parlour door and showed them in. I saw at once that they were of the species that scorns ceremony, and as each gave a careless nod to my host and dropped into the easiest chairs they could find, I took a good look at them. Fewster was a big, heavily built man of a solemn cast of countenance, and small, ferrety eyes; the sort of man who carries a stout stick, crosses his fat hands on it, and rests a double chin on his hands. Chissick was a rosy-faced fellow, alert, sly in expression, with a trick of looking quickly about him that reminded me of a perky cock-robin. And both men, after a mere glance of greeting to the man whose privacy they had so summarily invaded, fixed their eyes on me.

“Morning, Captain!” said Chissick cheerily. “Strange doings in the parish this morning! That’ll be the young man, I suppose?”

Captain Trace rose from the table as if he knew exactly what to do in these circumstances. Without replying to Chissick’s question, he went straight to a sideboard and to a spirit-case that stood in its centre, and, mixing two glasses of whisky-and-soda, silently handed one to each of his guests. Each man made some remark about the hour being early, but each took the glass.

“Best respects, Trace,” muttered Fewster. “As Chissick says, that’ll be the young man that we’ve heard of from Preece?”

“That’s certainly the young man you’ve heard of from Preece,” agreed Trace. “You seem curious about him!”

“Good ground for curiosity, I think, when there’s murder, genuine bloody murder, done at your very doors!” observed Chissick. “Now, what did you really see, young fellow? Haven’t you got a single clue?”

I gave Chissick a quiet, steady look; then, just to let Trace see that I was no fool, I spoke before he could.

“I mustn’t say!” said I. “The matter’s in the hands of the police. It’s sub judice!”

The man’s eyebrows went up as Trace laughed, and he looked from me to my host, and from him to Fewster, and back at me, viewing me from head to foot.

“Latin, eh?” he exclaimed. “Oh—oh! And how does a young fellow that talks Latin as natural as all that come to be sleeping out in an old mill—what?”

“That’s sub judice too, Chissick,” said Trace. “Come!—this boy can’t tell you anything. You know there’s got to be an inquest to-morrow—he’ll have to tell his tale then. You’ll hear it, all in good time—you’re sure to be on the jury.”

I was pretty quick of observation, for a youngster, and I saw that our visitors were somewhat taken aback by this: in each man’s face there was an expression that seemed to go deeper than mere curiosity; it appeared to me that both were anxious—with an unusual sort of anxiety, too.

“I don’t know about that—about waiting, Captain,” remarked Fewster, after a pause. “Here’s murder been done—at our doors!—and this young fellow seems, according to what I’m told, to be the only person that can say anything about it. As—as what I may call citizens, and if that isn’t the right term, ratepayers——”

“That’s the term,” interrupted Chissick. “Ratepayers! Two biggest ratepayers in the parish, for that matter!”

“As ratepayers,” continued Fewster, with an approving nod at his fellow-caller, “as ratepayers, and the most considerable ratepayers, I contend that we’ve a right to what I may call immediate information! And what I want to know from that young man is—can he recognise and identify the murderer?”

“Just so!” murmured Chissick. “Good! Couldn’t have been better put! Can he?”

Trace drank off his coffee and, pushing the cup aside, rose to his feet.

“He’s not going to tell you!” he answered. “That, too, ’ll have to wait till the inquest. It’s all sub judice, gentlemen—good term that! We’re precluded from speaking—till the law bids us speak. We’ll speak hard enough then!”

The two visitors looked at each other, and then at me and Trace, sourly.

“Not going to say anything, then?” asked Chissick. “Me and Mr. Fewster’s the two most important people in the place, Captain!”

“I dare say!” agreed Trace good-humouredly. “But—this lad’s mouth is sealed, till the coroner opens it. And his mouth’s just now in my charge—and I’ll keep it sealed!”

Fewster took his double chin off his hands, and his hands off his stick, and rose slowly.

“In my opinion,” he said gruffly, “in my opinion, Captain, that young fellow ’ud do better if he were assisting the police people to find the murderer! There’s railway stations at hand—three of ’em—and they ought to be watched! Murder is a very serious thing, and it isn’t pleasant for law-abiding people to know that a murderer is at large! And with a knife too!”

Trace picked up his cap and glanced at the door.

“I quite agree with you, gentlemen,” he said. “But you’ve come to the wrong shop! Try Preece. He’s the representative of the law! Go and put your views before him. Sorry—but I’ve got to go out.”

Whether the two men took this as polite hint or plain dismissal, I don’t know; they went away down the village street, talking in confidential whispers. When they were outside the gate I looked at Trace.

“What did they really want?” I asked him.

“Can’t tell you, my lad!” he answered. “Except that they wanted to turn you inside out, to ascertain for themselves how much you knew and didn’t know. But why?—ah, that’s what I don’t know! Deep fellows, both of ’em—crafty. Last men in this village to tell anything to. But come along with me—I’m going to see an old friend of mine before whom you can talk as freely as you like; he’s confined to a wheeled chair nowadays, and can’t get out, and a bit of talk’s a godsend to him—what’s more, he’s a wise man and keeps counsel.”

We went out through the garden and up the street towards the foot of the hill down which I had run that morning. At the gate of the farmstead where I had found him in my hurried rush for help, Trace turned in.

“This is Mr. Hentidge’s farm,” he said as we crossed the garden. “He’s a very, very old man, over eighty years of age, Tom. Lost the use of his legs, and has to be wheeled about; spends his time by the fire in winter and sitting out in the sun in summer. But wonderful in his faculties—clever as ever! Lost nothing but locomotive power, eh? Marvellous old chap! That was his daughter you saw me talking to this morning. Equally marvellous woman! Manages—everything!”

I saw at once that Trace was very much at home in the Hentidge farmstead. Without any ceremony of knocking at the door, he led me into the house and through a great stone-walled hall into a living-room that was half parlour, half kitchen. The woman I had seen that morning was shelling garden peas at a table in the wide window-place; near her, a newspaper in his hands, and in a big wheeled chair, sat an old man, who, I saw at once, had in his time been a man of unusual height and breadth, and still gave one the impression of uncommon vitality. He was reading his paper without spectacles, and the eyes he turned on me as Trace drew me forward were as brilliant as they were black. The woman, too, turned her eyes on me, and I saw that they were like her father’s, brilliantly dark and large; I saw, too, that she was even handsomer than I had thought her in the early morning light. She paused in her task as we entered, and, going over to the wheeled chair, whispered something to its occupant. The old man nodded, still looking at me.

“Just so, just so, my girl!” he said. “I understand! So that’s the young man, is it, Trace? Sit you down, young fellow.”

Trace pulled a couple of chairs close to Mr. Hentidge, and motioned me to take one of them.

“This is the chap, Mr. Hentidge,” he answered. “He’s told me all about himself, and I’ll vouch for him—I know his late master at Horsham. Now, Tom,” he went on, “you can tell Mr. Hentidge all about it, without fear—it’ll not go outside these walls. And Mr. Hentidge can, maybe, throw a bit of light on things—he knows that old mill and its surroundings better than anybody in the place. Begin at the very start of things, my lad.”

I told them the story as I had already told it to Trace and the police-sergeant. I had a good audience. The old man never took his eyes off my face. His daughter, leaning over the back of his chair, watched me from start to finish; she had an unusually mobile face, and it flushed or paled according to the quality of my story. I think, big and fine woman though she was, that she was marvelling how a boy of eighteen should have seen this horror and remain so very matter-of-fact about it. When I came to the actual murder she drew in her breath sharply. But the old man listened unmoved, taking in every point and nodding his head now and then. And when I made an end he immediately asked me a sharp question:

“You never saw the man’s face, boy—the man that made off?”

“No, sir,” said I. “The mist was too thick.”

“And he went off—which way, now?—which way from the mill?”

“Due east, sir—towards where the sun had risen.”

He nodded at that as if it was exactly the answer that he had expected to get.

“Aye!” he murmured, as if to himself. “He would—if he knew these parts. The woods are thick on that side. But——”

He relapsed into what was evidently a mood of deep reflection, which continued so long that at last his daughter, with a look at Trace, laid her hand on his shoulder.

“What are you thinking about, father?” she asked.

Mr. Hentidge started and looked up, first at her, then at us.

“I was thinking back, my girl!” he said, with a smile. “Many a long year ago, there was a man came into these parts, a seafaring man——”

What more he was about to tell us I did not learn at that time. My chair faced the window, and just then, chancing to look that way, I saw a man going slowly past on the road outside, and in him recognised my interrogator of Petworth churchyard.

I broke in upon whatever it was that old Hentidge was going to tell us and startled him and the other two, by leaping to the window with outstretched hand.

“That’s him—that’s him!” I shouted, forgetful of the grammar lessons I had learnt at Horsham School. “There!”

Trace leapt after me, staring.

“Who—who?” he exclaimed. “What’s the lad mean?”

“That man there, just going by!” I said. “That’s the man I talked to at Petworth, and saw at Graffham—you know!”

“Come on, then,” he responded. “Let’s be after him. If he’s here——”

He raced out of the house and I followed sharp on his heels. At the edge of the garden we caught sight of the man again. He was going slowly towards the hill-side, his hands in his pockets, his head dropping forward, just as I had seen him twice before. I vaulted the low wall and bawled loudly. He turned on the instant, stared at me for a moment, and then began to retrace his steps slowly. From the very leisureliness of his movements, I knew that this man was innocent of the murder of that morning; no guilty man would have taken his time as he did. He recognised me as we drew near each other, and he grinned in a sort of sheepish fashion. I scarcely knew what to say to him, but he relieved my uncertainty by speaking first.

“You, eh?” he said. “Here, too? Well, I reckon I’ve found it, at last. Up yonder—unless I’m sore mistaken.”

“The mill?” said I.

“What else?” he retorted. “As I say—if not sore mistaken. But”—here he turned, pointing to the mouth of a lane which opened on the village street just beneath Hentidge’s farmstead—“I’ve been taking a view of that mill for the last mile or two as I come along there, and in my opinion yon is the very mill I’m seeking, and that I told you about. Leastways, as far as I could observe the lie of the land where it stands. I was going up there when you called me back.”

Trace had come up by that time and was looking curiously at the man. The man returned the look, equally curious.

“You came along that lane—just now?” asked Trace suddenly.

“I did, master—if you want to know. A long cast by it, too—miles!” answered the man. “And—why?”

“From—where?” enquired Trace.

“Seems like this was a catechism class,” remarked the man, smiling. “But, Lord!—I don’t mind saying. Chichester!”

“You’ve only just come into this village, then?” continued Trace.

“Five minutes ago, master.”

“Spoken to anybody?”

“Ain’t seen a soul to speak to, till I see you two!” said the man with a grin. “And once more I says—why? Why this here catechising?”

Trace gave me a look, and I saw that he wanted me to do the next speaking. I gave the man a glance that was meant to be full of significance.

“Look here!” I said. “You know all you told me about your wanting to find that mill? Very well!—there was a man murdered up there this morning!”

We were both watching him narrowly, and we saw at once that this curt announcement hit him full and hard, and that deep in his mind there was something struck him about my news which was secret to himself. His eyes grew wide; his mouth opened; he remained open-mouthed for a full minute, staring at me. When at last he spoke, his speech came haltingly.

“A—man—murdered—this morning?” he said incredulously. “What man?”

“That’s what we don’t know,” remarked Trace. “A strange man—unknown. Look here!” he went on after a pause, during which the man continued to stare at us. “Why did you want to find this old mill?”

The man looked Trace up and down, very slowly.

“My business, master!” he answered.

“Very good—so it is, no doubt,” said Trace. “But you told this lad you were very keen about finding it. Do you know of anybody else who was equally keen?”

At this point the man did precisely what I had seen him do in Petworth churchyard: he pulled out his queer tobacco-box and helped himself to a liberal quid of the plug which he kept there.

“There may ha’ been,” he answered, as he closed his clasp-knife with a snap. “I won’t say other than that there may ha’ been. But ’tis odd—if so be as this is the mill I want—that another man should chance on it about the same time as I do, and then meet his death there! Murdered, you say?—and unknown?”

We nodded, silent; we were still watching him keenly, and I think Trace had the same wonder in his mind that I had. But the man was now cool as granite under our inspection.

“Who done it?” he enquired suddenly. “Where there’s a murder, there’s a murderer! Who was it, in this here case?”

“That’s unknown too,” replied Trace. He turned towards the village. “Look here!” he said. “You’d better come and see the murdered man! His body’s at the inn, awaiting the inquest. The policeman lives just down here—he’ll show you.”

The man showed no particular emotion one way or the other. He immediately turned to go with us.

“No objection,” he said. “A dead man or two makes no great difference to me. Seen a fair lot in my time!—under various circumstances. White ’uns and black ’uns!” he added, with a strong emphasis on the conjunction. “And yeller ’uns too, for that matter. This man—I reckon he’s white, eh?”

“Of course!” replied Trace.

“Of course, says you?” he remarked. “Aye well!—but in my train of thought I was thinking he might—just might, you observe?—ha’ been a nigger. There was a nigger, now I come to think on it—but let’s see this policeman and the body!”

I waited outside Preece’s cottage with the man while Trace fetched the sergeant out. Trace was some little time inside; when he and Preece emerged from the door, Preece had evidently been primed with the surface facts, and he immediately tackled the man with leading questions.

“You’re the man that this young fellow had talk with in Petworth churchyard the other night?” asked Preece. “About the locality of a mill?”

“We had talk—yes,” asserted the man. “A mill it was!”

“And you were at Graffham yesterday noon, eh?” continued Preece, “This young fellow saw you there; saw two men evidently pointing the way to you. Where did you go?—from Graffham?”

“Went all wrong!—along of what those men told me,” answered the man readily. “I went through Heyshott to Cocking, and then south to Lavant and Chichester. Them two at Graffham, they gave me certain information, but it was all no good.”

“Where were you at six o’clock this morning?” demanded Preece.

I saw at once what he was after, and I turned quickly on the man for his answer. It came just as quickly.

“In bed at Chichester!” he replied. “Temperance Hotel, in South Street. Didn’t get up till seven. Breakfast eight—then walked out here. And what’s all this here further catechism about, may I enquire? You can see what I am!” He paused and made a gesture of his hands, as if to invite Preece to look him well over. “Man o’ substance!—retired. Nice place o’ my own I have, at Fareham, with a mast in the front garden and a bit o’ glass at the back. My name’s Trawlerson—Mr. Hosea Trawlerson, Pernambuco Cottage, Fareham: them’s my directions. When at home, of course.”

I could see that this readily imparted information had its effect on the police-sergeant. His somewhat peremptory manner changed, and I thought he gave a sigh of relief, as if what Trawlerson had just told him shifted some burden off his shoulders. He nodded towards the village inn.

“Come this way, Mr. Trawlerson,” he said. “You’ve heard what’s happened here this morning? Well, you’re searching for a mill—a windmill—I understand you think it’s our mill, up there. Just so! Now, a strange man comes there last night and gets murdered close by, by some person unknown, at six o’clock this morning. Can you think—have you any idea—who the man can be?”

“At the moment, no!” replied Trawlerson. “Knocked me all of a heap to hear what this young fellow told me just now. Without doubt, what they call a coincidence. Queer altogether! Still, if I think back, and see this here dead man—you see,” he continued, after breaking off suddenly and then going on again in a burst of confidence, “you see, me having used the sea all my life till I retired, recent, I ha’ known a many things! Many things—queer things! Many men—still queerer! All sorts o’ things, some of ’em fitting one into another, and a many that wouldn’t fit nohow. Lots o’ faces too—white, black, brown, yeller. Now, if I see a face and can give it a name——”

We were close to the inn by that, and Preece led us to an outhouse and produced a key from his pocket.

“Let’s see if you can give this face a name, then,” he said. “If you can——”

He opened the door, and we all took off our caps and walked in, on tiptoe. The place was a saddle-room, tidy and quiet. What we had come to see lay, still enough, on a table in the centre, with a white sheet over it. Preece slowly raised the head of the sheet, and beckoned Trawlerson to approach.

“Now!” he whispered.

Carrying his hat under his arm, and still tiptoeing, Trawlerson went up and looked earnestly at the dead man. The next instant he started back.

“Good Lord!” he whispered. “It’s Kest! Kest! Now, what the——”

Suddenly checking himself, he drew away; the next instant he was outside the door, in the sunlight, beckoning us to follow.

“Come out!” he commanded, clawing impatiently at us. “Come out! Well, of all the—here!” he went on as Preece came last, locking the door. “This here is an inn, ain’t it? Of course! Now, is there a quiet, peaceful corner in it where——”

Preece was quick to see what he wanted, and motioning Trace and me to follow, he led the way into the inn, and, after a word with the landlord, conducted us into a small room at the back of the bar. We had that place to ourselves, but Trawlerson would not say a word until he had refreshed himself with rum: phlegmatic as he had always been up to that point, it was very evident that his recognition of the dead man had shaken his imperturbability. And there was something approaching very real and serious anxiety in the first question he put to Preece as soon as he set down his tumbler, one-half the contents of which he had tossed off with eagerness as soon as the landlord put it before him.

“This here man?” he asked, jerking his thumb towards the outhouse. “Kest! What had he on him? Who found what he had?”

“I searched the body,” replied Preece. “Precious little, Mr. Trawlerson. No letters, no papers. A handkerchief. A knife. Nine shillings and fivepence-halfpenny in silver and copper. That was all. But,” he added, eyeing his questioner closely, “he had had more than that on him. This young man saw things on him last night which weren’t there when I examined the clothing. There was a watch and chain. And—there was a map.”

The effect of that last word on Trawlerson was marked. He jumped in his seat; the veins swelled in his forehead; he glared at Preece, and I saw his fist bunch itself into an ugly knot of twisting muscle.

“A map!” he exclaimed. “What sort of a map? D’ye mean—but here, I’m all at sea! This young man saw—what did he see? Let him tell! I want to be knowing! Kest here!—knifed—a map?—it’s—it’s——” He swallowed another mouthful of his drink, and waved the glass at me before setting it down. “Let’s be hearing!” he commanded. “Tell it plain—plain!”

I looked to the police-sergeant for his approval, and as he nodded, I proceeded to tell my story for the third time that morning. As I went on, Trawlerson’s face grew blacker and blacker; it became thunderous when I came to describe the map. But when I corroborated the policeman in his statement that the map had disappeared by the time the body was examined, his temper gave way, and he broke out on me for a damned young fool for leaving the man. I should have stayed by him, he vociferated, till the sea fog cleared and help came.

“Fool yourself, Mr. Trawlerson!” I threw back at him. “Who are you to be calling names? You were——”

“No words, no words!” interrupted Preece hastily. “The lad did his best, Mr. Trawlerson. But this map——”

Trawlerson, who had thrust his hands into his pockets, stretched his legs under the table, and drooped his head forward on his chest in an attitude of sulkiness, turned on the policeman with a scowl.

“What are you and your like doing to find the man as done this?” he demanded. “Kest, he’s been followed! For that map, of course. Either the man as scragged him got it before he done it, or he came back when this lad was gone, and got it. In either case——”

“We’re doing all we can, in the time,” said Preece. “You’ll find no slackness on our part, Mr. Trawlerson! But this map——”

Instead of answering, Trawlerson slapped his hand on the bell, and, the landlord appearing, motioned him to replenish his glass.

“I ain’t going to say a word more!” he announced, turning sharply on Preece. “Not one syllable! There’ll be a crowner’s ’quest on this here body, and I shall be there——”

“You’ll have to be!” interrupted Preece. “I don’t know any other who can identify him.”

Trawlerson gave him a dark look. His behaviour had changed, and was becoming mysterious.

“I shall be there for something else than that!” he said grimly. “In this house it’ll be, and in this house I stops till the crowner comes! And till then my mouth’s shut!”

We left Trawlerson making his arrangements with the landlord and landlady for a bed that night, and went out into the street. By that time I was beginning to feel the reaction of the recent doings, and I should have been thankful to go back to Trace’s cottage and lie hidden away from everybody. But Preece had been busy on telegraph and telephone, and the village was being invaded by police officials from Chichester, and by pressmen from the neighbouring towns. All these people wanted to get hold of me, and Trace had his work set in his self-constituted part of guardian. The pressmen we could elude or choke off, but the police were different, and I had to submit to examination and cross-examination until I almost wished that I was back in Andrew Macpherson’s shop. And once or twice I felt that there was an element of suspicion in the manner of some of these matter-of-fact, hard-faced men: it seemed to be against me that I had chosen to sleep out all night, and once or twice I felt the blood rush about my ears as one or other of them questioned me strictly about myself and my past. I got sick of that, and grew restive, too.

“If you’re having any doubts about me,” I suddenly flared up as a man who, they told me, was a very great personage in the police, was turning me inside and out with his questions, “you’d better ask Mr. Andrew Macpherson, of Horsham, about me! He’ll pretty soon tell you that my word’s as good as his own! He knows me——”

“You needn’t bother yourself, my lad!” said my questioner, with a dry smile “We’ve sent for Mr. Macpherson already. And don’t you get huffy!—this is a case of murder, and a bad one, and we don’t leave any stone unturned in such cases. You tell your tale all right—but we don’t know you, you know.”

They let me go home with Captain Trace after that, but I think there was a secret understanding between them and him about his having charge of me, and for the rest of that day—or, at any rate, until Mr. Macpherson arrived during the late afternoon—I never looked out of Trace’s parlour window without seeing a policeman near at hand; the village seemed to swarm with policemen. But Andrew Macpherson came, and he talked to the bigwigs in his forcible way, and thenceforward the police treated me with the respect due to a credible and trustworthy witness. Still, whenever they returned to their questioning of me, I had to give them keen disappointment—from start to finish I told them flatly that it was an absolute impossibility for me to identify the man I had seen struggling with Kest in the sea fog. I had a vague, general, not-much-to-be-trusted impression of his figure, but not the slightest of his face.

Trace, on the strength of their previous meetings at Quarter Sessions, greeted Macpherson as an old acquaintance, and took him home to his cottage. Andrew favoured me with one of his sly smiles.

“Aweel, Tom!” he said as he sat him down. “Ye were longing for adventure and the like o’ that, and, my certie, ye seem to ha’ lost no time in falling head and shoulders into one, my man!”

“None of my seeking, Mr. Macpherson!” said I. “I didn’t set out to find that sort o’ thing—I’d ha’ been thankful to escape it. But how can anybody tell what’s going to happen to ’em, Mr. Macpherson?”

“And I could dispute that wi’ you, my laddie!” said he. “It’s a fine point, but whether it belongs to the domain o’ logic, or to that o’ theology, or yet again to that o’ metapheesics, I’m no very sure. There’s such a thing as prevention by anticipation, ye ken, and for my part I’d no advise young fellows wi’ good siller in their pouches to sleep otherwhere than in a Christian-like bed. If ye’d no had them Robinson Crusoe notions in your head-piece, and had sought other quarters than yon old mill—but losh, man! what’s the use o’ talking about bygones?—the thing’s done! And beyond a bit smattering o’ the facts, Tom, I’m no very well acquaint wi’ the story—out with it, my man, and I’ll maybe form an opeenion.”

I had to tell it all over again as we three sat round Trace’s tea-table. At the end Andrew began to sniff.

“I’m no liking what I hear o’ that man Trawlerson!” he remarked, when I, supplemented in the final chapter by Trace, had come to a conclusion. “The sound of him is no to my taste! What for is a man that’s retired from his business, and by his own account has a nice bit of property and a mast in his front garden and a glass-house at his rear, going stravaging about the country, seeking an old windmill? There’s more in it than meets the eye!”

“I wish they’d riddle Trawlerson with questions as they’ve riddled me all day!” I exclaimed. “He’s a far more suspicious character than I am!”

They both replied to that pious aspiration that Trawlerson would be questioned, strictly enough, when he got before the coroner and his jurymen. I supposed that would be so, but I was not so confident that they would get much satisfaction from Trawlerson’s answers. Trawlerson, in my opinion, was the sort of man who finds small difficulty in twisting himself out of tight places.