* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Vol 1, Issue 3

Date of first publication: 1865

Author: John Townsend Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Feb. 10, 2016

Date last updated: Feb. 10, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160214

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. I. | MARCH, 1865. | No. III. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience. Additional Transcriber's Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.]

icely, called Garnet at the foot of the stairs.

icely, called Garnet at the foot of the stairs.

“Yes, I’m coming,” responded Cicely from the depths of her pretty little chamber.

“It’s time to go.”

“Yes, I’m coming,” repeated the gentle voice.

Garnet supported himself on his elbow and right foot, attempted to scale the stairs on his heels and head, and made other interesting experiments; but finding that Cicely did not come, he climbed up outside of the balusters, over the gallery railing, and bounced into her room. She was standing before the glass, surveying her little self with great complacency.

“Now, how long will you be prinking there, and me waiting down stairs?” cried Garnet. “I never did see anything like the time it takes girls to dress.”

“O, I’m quite ready this minute,” answered Cicely, hastily catching up her bonnet.

“But mehercule!” shouted Garnet, who was devoting himself to the study of Latin with great vigor. “What do you call this?”—and he clutched Cicely’s hair with no very gentle grasp.

“O, don’t touch it! you will have it all down!” cried she hurriedly; “that is a waterfall.”

“A waterfall! A waterfall! Let it fall quick then. It makes you look for all the world like our skew-tailed chickens. I never saw such an animal.”

“O Garnet, now I thought it looked so pretty!” said Cicely; and her bright face was so clouded that even Garnet was rather sorry he had spoken so decidedly.

But then certainly it was a case that called for decision. Poor Cicely had spent at least half an hour before the glass, and tired her little arms till they ached; and the result was a knob of hair hanging on one side of her head, and bobbing hither and thither with every motion. Garnet’s comparison was not entirely out of place. “But what could make you think of tricking up such a fright?” he asked.

“Why, Garnet, there’s a new girl going to be there from Boston. She’s going to live with Miss Attredge. And Olive said—” Cicely hesitated.

“Well, what did Olive say?”

“Why, Olive said—she said that—Olive said the girl would have everything so nice because she came from Boston, and Olive said they wore silk dresses and waterfalls in Boston, and Olive is going to wear her blue merino and a waterfall, and I made mine,—Olive told me how,—and now you say it is not pretty.”

“Olive’s a born simpleton,” said Sir Oracle Garnet. “You take that bobbing bag off your head. I don’t believe they wear them in Boston, and if they do, you sha’n’t. I suppose you’d tie yourself up in a meal-bag if they did in Boston.”

“But, Garnet, what shall I do?”

“Do! curl your hair just as you always do, and brush it in a civilized manner.”

“Oh! then I shall not look fine at all. Olive said we should show Mary Ravis that we were not just country-girls. We know what the fashions are. Mary Ravis will think we are just country-girls.”

“And I should like to know what you are?”

“Well, I know, but—” Cicely hesitated, and faltered, and rather reluctantly began to pull down the comical little contrivance which she dignified with the name of waterfall, and to brush out the long ringlets as she was commanded. And to be sure, she did look like a different girl; still there was many a misgiving in her heart as to the figure she should make in the eyes of the little city lady.

Garnet had no share at all in her misgivings. He had a very favorable opinion of his sister, and especially of himself. “Hold up your head, Cicely,” was his admonition, “as you never could with that ten-pound weight hanging on to it, and don’t call the king your uncle!”—though what that had to do with holding up her head, Cicely could never quite make out.

By the time they reached Miss Attredge’s house, where the party was to be, most of the children had assembled. They all went to the same school, and were well acquainted with each other,—all except the little city girl, who sat in a corner, and seemed quite as much in awe of them as they were of her. But Cicely took note that she had no silk dress, nor even a waterfall. On the contrary, her hair was short, and her dress a very pretty plaid, but not at all beyond the standard of the dresses in Applethorpe. She was, too, very quiet,—a pale, silent girl,—that was all Cicely saw.

“What do you think of her?” whispered Olive to Cicely.

“We mustn’t whisper about her,” replied Cicely, who had hardly had more than a glimpse of her. But they pulled Cicely into the dining-room, and would tell her that she was “real proud. She just sits there, and won’t do anything.”

“Yes,” said Olive, “and not so much to be proud of either. Nothing but a plaid dress, and not a speck of trimming, nor a net, nor a bow, nor anything,”—and Olive thought very pleasantly of her own French blue merino with its elaborate embroidery.

“Oh! I don’t think it’s proud,” said Erne Mayland. “We are all strangers to her, and she doesn’t feel at home.”

“Nonsense,” cried Olive, “we have been here half an hour, and asked her to play, and Miss Attredge wanted her to play, and she won’t do a thing.”

“But I don’t think it is nice at all to be here talking about her,” said Cicely.

“No, nor I neither,” declared Erne. “Come, let’s go into the parlor.”

“I shall not go into the parlor to court Miss City-fied anymore,” answered Olive. “It’s too bad she should come here to spoil all our good time.”

But Erne and Cicely went into the parlor. Miss Attredge was just gathering them into a circle to play “Hunt the Slipper.” Cicely was about to take her place with the rest, when she noticed that the little stranger still sat apart, looking rather lonely and homesick. So she approached, her and asked, rather timidly, “Won’t you play?”

“I don’t know how,” answered Mary.

“But I will tell you all about it.”

“I would rather not.”

“Then I won’t play, either,” said Cicely, cheerfully. “I’ll show you Miss Attredge’s photographs. No, I won’t; I’ll show you her snakes and birds. Miss Attredge always lets me touch them”;—and Cicely took from the lowest shelf of the bookcase a book so heavy she could hardly lift it; but the kindness in her heart put strength in her arms, and she tugged it along to a chair.

It was not in the nature of any girl ever so shy to resist the temptation of looking at pictures so beautiful and so dreadful as those that Cicely pointed out. The birds were wondrously brilliant, and the snakes coiled themselves in folds so fearful that Mary quite forgot her forlorn little self, and the two children were soon kneeling before the chair and pressing their eager heads close together in breathless excitement. When the others had grown tired of “Hunt the Slipper,” they too gathered around the chair, and the two heads were quite overtopped by a crowd of heads, and the two voices lost in a dozen voices chattering and exclaiming and explaining. The girls pretended to be very much afraid of the snakes, and shook and shivered. The boys pretended to have a great regard for snakes, and stroked their necks with brown, battered hands.

“Oh!” cried Olive, who had joined them; “but this is a paper snake, Mr. Nathan. If it was crawling on the grass, you would be careful how you touched it.”

“Pooh!” cried Nathan, “I’d just as soon touch it as touch your kitten. They’re twice as handsome.”

“Indeed they are,” said Garnet. “Sweet little pets! dear little darlings!” and he made believe caress the snakes, but made rather awkward work of it, as boys generally do when they undertake to mimic girls. “Why, the other day, last summer, we caught a snake and tied him round the bedpost, and kept him there all night.”

“Now, Garnet Moreford, you don’t expect us to believe that!”

“Yes, he did, the dreadful creature!” cried Cicely. “Barney went into his room in the morning, and there ’twas; and she screamed and ’most fainted, and Garnet laughed, and it was dreadful.”

“Pooh! that’s nothing,” said Nathan. “I caught a little snake once, and wove him into my button-holes, and wore him all the forenoon. It’s girls for being afraid of harmless pretty little things.”

“Girls are no more afraid than boys,” replied Olive, stoutly, always ready to stand up for her sex. “I found a nest of field-mice last summer, and took them up and brought them into the house in my apron. But a snake isn’t harmless. Snakes poison you.”

“Ho!” cried Nathan, “calling it courage not to be afraid of a mouse! Why, there was a mouse in the closet last Sunday, and he ran and hid under a crust of bread, and stuck his tail right up straight in the air, just like a handle, and I took hold of it as dainty, and carried him out-doors.”

“And let him go?” asked Mary Ravis, eagerly, her fears of strangers quite vanished in the excitement of the horrible stories they were telling.

“Yes, I let him go. But Tabby had a word to say on that subject, and he didn’t go very far.”

“Well, I know what you are afraid of, Nat,” said Olive, decidedly,—“a setting hen. For I was at your house when your mother wanted you to take one off the nest, and you did not dare. You said she pecked you so furiously you couldn’t!”

“O, pshaw!” laughed Nathan, good-humoredly, and giving himself a whirl, as if to shake off this disagreeable home-thrust, “what are you talking about? Mary Ravis will think we are a set of savages, telling her all sorts of scaring things. You never saw a snake, now did you, Miss Mary? She thinks butter grows on trees in brown burrs, and we get honey by milking bees in a ten-quart pail.”

Mary would have been very much frightened, half an hour before, at being thus addressed before them all; but she had lost her first shyness, and Nathan’s banter was so good-natured that she did not feel at all embarrassed, but laughed as heartily as the rest, while a little fresh color stole into her pale cheeks and a good deal of sunshine lighted up her brown eyes.

“No,” said Garnet, kindly, “I warrant you this sly little puss knows a great deal more than any of us. Why, what do you think? She carries the Falls of Niagara in her pocket, or something.”

“O, what a story!” laughed Mary.

“Why, Cicely, didn’t you tell me so this morning?” asked Garnet, gravely.

“Why, no,” answered Cicely, opening her astonished eyes, and pursing her rosy lips into the most decided denial. “I never said such a thing.”

“Now Cissy, Cissy, young woman, what trouble have you led me into? Didn’t you say the young lady from the city was going to bring a waterfall here, and didn’t you want me to go and get the mill-dam to fasten on the back of your neck by way of offset?”

And then, being forced in self-defence, Cicely told the story of her waterfall, and they all laughed very merrily, somewhat to Olive’s discomfiture. And then came other plays, games of forfeits, in which Mary readily joined. All manner of odd sentences they pronounced upon each other. Nathan in particular found no mercy at the hands of his girl-judges. He was condemned to wriggle across the room like a snake, to jump up in a chair like a squirrel, to bark like a dog, all of which he did so readily and so well, that he made them great entertainment.

“O, I never did see such a nice party in all my life!” whispered Mary confidentially to Cicely. “You all do such funny things!”

“O Mary!” said Cicely modestly, “you can do a great many beautiful things that we can’t, I do suppose?”

“No, I don’t do many things at all,” said Mary. “I can dance, that is all; but I can’t tell stories, and I can’t play plays, and I can’t think of forfeits, and I never did any funny things.”

“Can you dance? Oh! I do like to see dancing.”

“Do you? and I like to dance. Mr. Piccini says I dance very nicely, and O, I can dance the Shawl Dance, and the Highland Fling; would you like to see me?” she asked simply.

“O, of all things! and so would all the girls.”

“Well,” said Mary, “if Miss Attredge will play, I will. But do you think they would care to see me?”

“I know they would! O Garnet! Olive! O all of you! Mary Ravis will dance the Highland Fling and everything Miss Attredge will you play boys all come and sit down!” Cicely was too eager to be particular about her punctuation; but they understood her well enough, much better, indeed, than they understood the Highland Fling, which most of them had never heard of. But they were delighted with the sound of it.

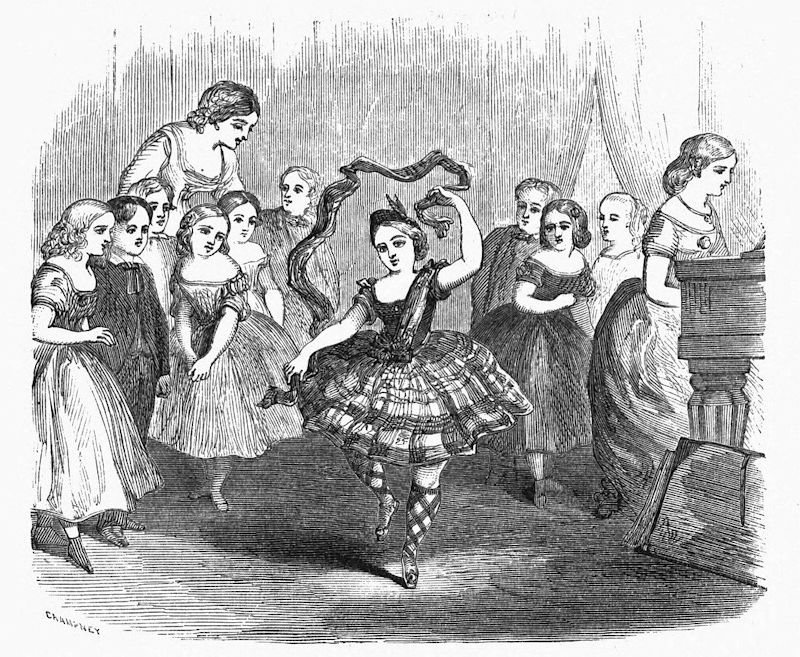

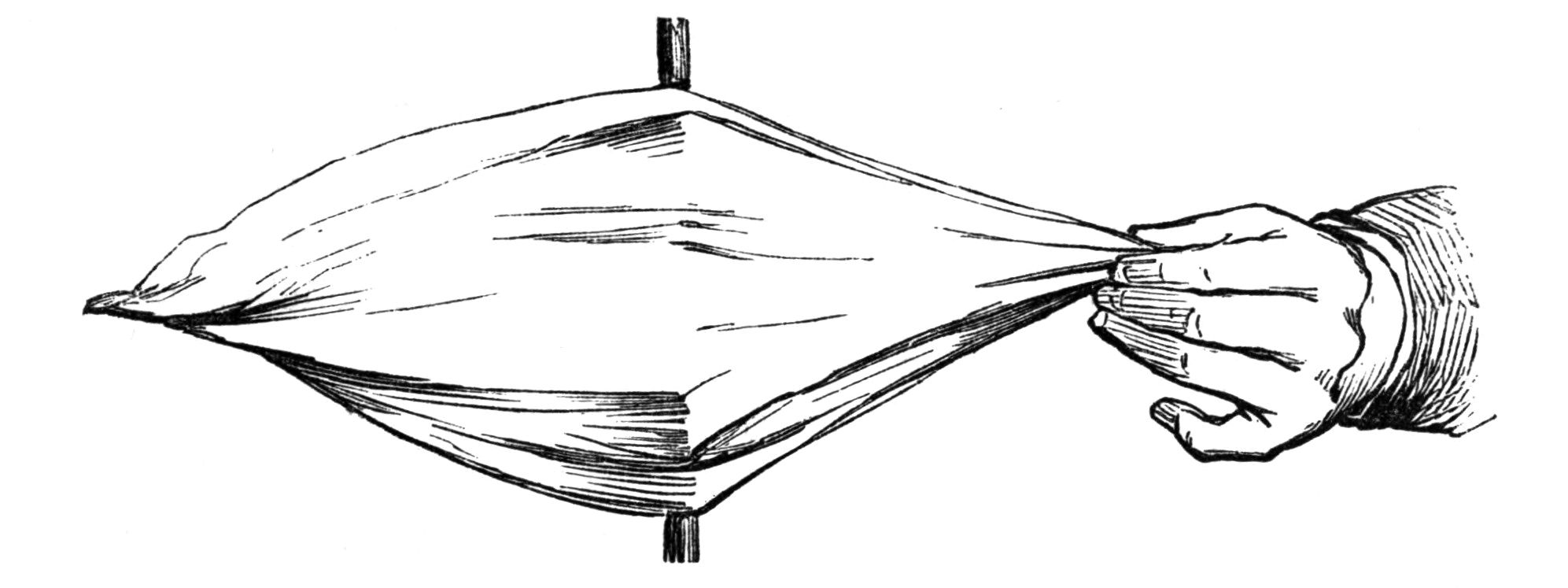

So Mary went up stairs and put on her costume,—a marvellous little black velvet bodice adorned with gold lace, a bright plaid frock, delicately embroidered slippers, a cap and feather for her little shorn head, and a long scarlet scarf in her hands. The company gathered at the lower end of the parlor, and Mary, smiling and happy at the upper end, began the dance. Never were such doings seen in Applethorpe as went on between Mary and her scarf. In and out, back and forth, she wove it and flung it, and wreathed herself in it. She skipped up and down the room like a zephyr, she whirled about on the tips of her dainty slippers, she charged down upon the admiring crowd, and withdrew again, swift and graceful as a bird, for at least twenty minutes I should think, and then she made the sauciest little courtesy, and danced out of the room. Never were admirers more enthusiastic, and when she reappeared in her usual dress once more, they quite overwhelmed her with their delight.

“And to think,” said Olive frankly, “that I thought you were proud because you wouldn’t play; and here you have done the beautifullest thing for us I ever saw.”

“O, proud!” laughed Mary, “it’s all I can do. It would be a pity if I couldn’t do something.”

“But then we were so cross, I wonder you did it at all.”

“You are not cross, I am sure,” cried Mary eagerly.

“Yes I am cross,” persisted Olive; “I am always cross if people don’t do just as I want to have them right away. Cicely Moreford is the good one, and Erne Mayland, and all those midgets. For my part, I don’t see how people can be so horribly good and patient all the time,”—and Olive put on such an air of despairing humility that they could not help laughing at her.

So it happened that the “good time” which the little city girl was going to spoil, turned out to be not only not spoiled, but made a great deal better by her presence,—and all because one or two little girls went to work the right way, instead of standing scornfully aside and letting everything go the wrong way. But the impression that seemed to linger longest on Cicely’s mind was, “And she was just like us. Why, she didn’t even have a waterfall!”

Gail Hamilton.

OR, THE WORLD BEWITCHED.

(Concluded from the February No.)

Having thought it all over, Andy resolved to make a new start, and not be deceived by anything again. Finding his coat very wet, he concluded to wring it out, and hang it somewhere to dry. He saw a log and a large wood-pile near by; and he was going boldly to spread his coat on them in a good sunny place, when he happened to think that these also might be cheats, and that it would be wise to test them before going too near.

He took up a pebble, and threw it. He hit the end of the log, which immediately changed into a head with a hat on it; and the log jumped up, and strode fiercely towards him, on two as good legs as ever he saw.

“What are you stoning me for?” cried the log, with a terrible look.

“O Mr. Log! I didn’t mean to! I didn’t know it would hurt you!” said Andy, clasping his hands.

“I’ll teach you to throw stones and call names!” growled the log,—no, not the log, but the teamster, whom Andy had mistaken for a log as he lay on the roadside by his wagon. And he gave two or three extra stripes to the boy’s trousers with his long whiplash. “I didn’t mean to! I didn’t know it would hurt you!” he said, mockingly, as he went back to his team; while Andy rubbed his legs, and shrieked.

Now, when wagon and driver were gone, and the lad saw that there was neither log nor wood-pile anywhere by the road, he became more and more alarmed about himself. Everything was a lie, then; and, the best he could do, he could not help being deceived and injured. Bitterly he regretted using old Mother Quirk so ill; and he said to himself that he would never tell another lie in his life, if he could now only get safely home, and find things what they appeared to be.

Being very tired, he looked about for a stick to walk with. He thought, too, something of the kind would be useful to feel with, and test the truth of things. Soon he saw a very pretty stick lying in the sun. It was not quite straight; but it had as handsome little wavy curves as if it had been carved. It was beautifully tapered; and as he came quite near it, he saw that it was painted with the most wonderful colors,—glossy black, bright green spots, and silver rings. It appeared to be a cane, which probably some very rich man had lost. Its carved handle was of gold, set round with precious stones, in the midst of which were two very, bright, glittering diamonds.

“Such a cane is worth picking up!” said Andy, highly pleased. “I hope the owner won’t come to claim it.” And he stooped down to take hold of the stick. But he had scarcely touched it, when it began to move and squirm, and coil up under his hand. He sprang back just in time to save his parents the grief of a funeral; for what he had mistaken for a cane was a living serpent of the most venomous kind; and it raised its angry crest, darted out its forked tongue, and struck at him with its hooked fangs, making his blood curdle and his flesh creep, as he ran screaming away.

Andy reached a wall—or what seemed a wall—and scrambled upon it, putting one leg over it, and looking back; when the stones began to sway and swell under him; and the whole wall rose up with such a tremendous lurch, that he was nearly thrown head foremost to the ground. And he now perceived that, instead of climbing a wall, he had mounted a horse that lay dozing in the field. Before he could get off, the horse began to walk away. In vain Andy cried “Whoa!” and gently pulled his mane. The horse seemed to understand “Whoa!” to mean “Go along!” and he began to trot. Pulling his mane had the effect of pricking him with a goad; and he commenced to prance. Then Andy gently patted him; but he might as well have struck him with a whip. The animal began to gallop! And when Andy, to avoid being flung off, clung to him with his feet, it was as if there had been sharp spurs in his heels, and the animal began to run!

Across the fields; faster and faster and faster; wildly snorting; measuring the ground with fearfully long leaps, and making it thunder under his hoofs; clearing fences and ditches, and heaps of brush and logs, as if he had wings; away—away—away!—through thickets, through brier-lots, through gardens, and orchards, and farm-yards; with Andy hugging his neck in terror extreme, thrusting into his ribs the heels that seemed to have spurs on them; the wild steed scudded and plunged.

Andy clung as long as he could. The terrible bounces almost hurled him off; the wind almost blew him off; the thickets, and briers, and boughs of trees almost scratched him off. Everywhere along his track people came out to stare, and to stop the horse. Men hallooed and shook their hats; boys screamed and shook their bats; women “shooed” and shook their aprons; all contributing to frighten him the more.

And now Andy felt his breath partly jolted out of him, and partly sucked out by the wind. And for a moment he scarcely knew anything, except that he was losing his hold, slipping, sliding,—a hairy surface passing rudely from under him,—and the ground suddenly flying up, with a stunning flap and slap, into his face.

In a little while a young lad, considerably resembling Andy, might have been seen sitting on the grass of a field, rubbing his shoulder, with a jarred and joyless expression of countenance, which seemed hesitating between fright and tears,—between numbness and deadness of despair, and a returning sense of pain and grief. He saw a gay-looking horse frisking and kicking up along by the fence; felt in vain for his hat, but found a shock of wild hair instead; saw his torn trousers, wet not with water only, but also with blood from his scratched legs; arose slowly and sufferingly to his feet; looked imploringly about him; and began to snivel.

Not knowing what to do, he sat down again, and wept miserably, until he heard a sound of wheels, and a voice say, “Get up, Jerry!”

“That’s our wagon—and father and mother!” exclaimed Andy, in great joy, springing up as quickly as his sore limbs would permit him. “Father! father!” and he ran towards the road.

The vehicle rattled on. His father either did not hear or did not heed him. He could not make his mother look up, scream as loud as he would. Jerry trotted soberly on, as before. Only Brin the dog pricked up his ears, gave a surly bark, leaped the fence, and approached him shyly, bristling and growling.

“Brin! Brin! here, Brin!” said Andy, alarmed at the dog’s extraordinary behavior.

“Gr-r-r-r-!” said Brin, with a snarl and a snap.

“O father! father!” shrieked Andy.

“Whoa!” said Mr. Mountford, stopping Jerry, and turning to look. “Come here, Brin!” And he whistled.

Brin, having paused to take a sagacious snuff of Andy, without appearing to recognize him, ran back to the road, the boy following him.

“What’s the trouble?” said Mrs. Mountford. “What a strange-looking dog that is!”—fixing her eyes on Andy. “It looks to me like a mad dog, and I’m afraid Brin will get bit. Come here, Brin!”

Brin ran obediently under the wagon; and Andy, flinging up his arms, rushed towards his parents.

“O, it’s me! it’s me! Father! mother! it’s me!”

“Get out, you whelp!” exclaimed Mr. Mountford, striking at him with his whip.

“Oh! oh!” shrieked Andy, hit in the face by his own father’s lash!

“Ki-hi, then!” And Mr. Mountford drove on.

Andy still followed, running as fast as he could, wildly weeping and calling.

“What a hateful dog that is!” said Mrs. Mountford. “Give me the whip!” And as soon as Andy got near enough, she beat him mercilessly over the bare head.

Then Andy, exhausted, out of breath, his heart broken, fell down despairingly, with his face in the dust, while the vehicle passed over the hill out of sight. There he lay, sobbing in his misery, and moistening with a little trickling stream of tears the sand by the bridge of his nose, when an old woman came hobbling that way on a crutch.

“What’s this?” said she. Her back was curved like a bow; but she bent it still more, stooping over to look at Andy.

The boy raised his head, brushed the adhering dirt from his nose, lifted his eyes, and recognized good old Mother Quirk. But he could not speak.

“I declare!” said she, “one would think it was Andy Mountford, if anybody ever saw Andy Mountford in such a plight as this!”

That encouraged the wretched boy to open his mouth, spit out the dirt that obstructed his speech, and in grievous accents pour forth the story of his woes.

“But how do I know this is true?” said Mother Quirk, putting up a pinch of snuff under her hooked nose.

“It is true, every word; as true as I am Andy!” wept the boy.

“But how do I know you are Andy? Folks and things lie so, in this world!” said Mother Quirk. “But never mind; I suppose it is fine sport; and if it is really you, Andy, I suppose I may as well leave you to enjoy it!”

She adjusted her crutch, and was hobbling away, when Andy, on his knees, called after her, making the most solemn promises of truthfulness in the future, if she would help him home.

“How do I know what to believe?” said the old woman, piercing him with her black, sparkling eyes. “You may be a reptile. I’ve known more than one that pretended to be human, and honest, and grateful, turn out a reptile at last. Everything is so deceitful, we never know what to depend upon.”

She was passing on again; but Andy ran after her, and caught her gown, still pleading and weeping.

“Bless my heart! Is it really Andy?” said she, leaning on her crutch. “I’ve a good mind to trust you, and try you once!”

“Do, do! good Mother Quirk!”

“Well, come along; my house is close by; and there comes my black cat to meet me!”

Andy was overjoyed, and clung to her as if he was afraid she too would turn out a delusion,—a lie,—and work him some new mischief.

They passed a field, in which the old woman picked up a hat, which she placed on his head, and a handkerchief, which she told him to put into his pocket. “If you are Andy, they belong to you,” she said, with a shrewd look out of her coal-black eyes.

They reached her cottage, where she washed him, combed his hair, took a few stitches in his clothes, and stroked his hurts with hands dipped in some exquisitely soothing ointment. Then they set out to return to his father’s house.

She accompanied him as far as the well, where she gave him a sudden box on the ear, which set him whirling. The next he knew, he was getting up from the grass, like one awaking from a dream. He thought he had a glimpse of a crutch and a dark green gown vanishing behind the wood-shed, but could not be certain. He looked in vain upon his person for any evidence of rents and bruises, bee-stings or drenching. He was as good as new, to all appearance; and one who did not know the subtle power of old Mother Quirk would have said that he had merely fallen asleep on the door-yard turf, and had a dream.

“Andy!” cried a voice.

That was a reality, if anything was. His folks had returned, and it was his father calling him. “Andy! come and open the gate!”

He hastened to swing the old gate around on its hinges, while Brin ran up eagerly to caress him and leap upon his legs, and Jerry walked slowly through, drawing the family one-horse wagon.

“Have you been a good boy, Andy?” asked his mother, dismounting at the horse-block.

“Yes, ma’am. I mean,” he added, fearing that was an untruth,—“I don’t know,—I guess not very!”

“What! you haven’t been doing any mischief, have you?” cried his father.

Andy remembered the stories he had made up about the hawk killing the chicken, and the Beals boy throwing a stone through the pantry window. But he also remembered his terrible adventure in a world of lies,—mishaps and horrors which were somehow dreadfully real to him, whether he had actually experienced them, or dreamed them, or been insane and imagined them. So he falteringly said, “I—I—killed the top-knot with my bow-and-arrow!”

There indeed lay the top-knot, stark dead by the curb. His parents looked at it regretfully; and his father said, “I am sorry! sorry! that nice chicken! But you didn’t mean to, did you?”

“I didn’t think I should hit it!” said Andy, hanging his head with contrition.

“Well, if it was an accident, let it pass,” said his mother. “It isn’t so bad as if you had told a lie about it. I’d rather have every chicken killed, than have my son tell a lie!” And she caressed him fondly.

“You haven’t done anything else, I hope?” said Mr. Mountford.

“I—I—shot at the cat, and sent my arrow through the window!” Andy confessed.

“Haven’t I told you not to shoot your arrow towards the house?” cried his father, sternly. But, at a glance from Mrs. Mountford, he added, relentingly, “but as you have been so truthful as to own up to it, I’ll forgive you this time. Nothing pleases me so much as to have my son tell the truth; for the worst thing is lying.”

That was what Mother Quirk had said, and it reminded Andy of the false alarm which had brought her to the house. That was the hardest thing for him to confess! And it was the hardest thing for his parents to forgive.

“Poor old Mrs. Quirk, with her lame leg!” his mother reproachfully said. “How could you, Andy?”

“I didn’t think,—I didn’t know how bad it was!” he replied.

“What did she say to you? What did the poor woman do?”

“She scolded me, and boxed my ears, and made me crazy, I guess,—for such awful things have happened to me! I never can tell what I have been through—or dreamed I went through—till she brought me back! But I’ve made up my mind I never will tell another lie, or act a lie again, if you will forgive me this once!”

“I forgive you! we forgive you! my dear, dear boy!” exclaimed Mrs. Mountford, folding him in her arms, while Mr. Mountford smiled upon him, well pleased, and stroked his hair.

J. T. Trowbridge.

MERRY TIMES.

When the long northeast storms set in, and the misty clouds hung over the valley, and went hurrying away to the west, brushing the tops of the trees; when the rain, hour after hour, and day after day, fell aslant upon the roof of the little old house; when the wind swept around the eaves, and dashed in wild gusts against the windows, and moaned and wailed in the forests,—then it was that Paul sometimes felt his spirits droop, for the circumstances of life were all against him. He was poor. His dear, kind mother was sick. She had worked day and night to keep that terrible wolf from the door, which is always prowling around the houses of poor people. But the wolf had come, and was looking in at the windows. There was a debt due Mr. Funk for rice, sugar, biscuit, tea, and other things which Doctor Arnica said his mother must have. There was the doctor’s bill. The flour-barrel was getting low, and the meal-bag was almost empty. Paul saw the wolf every night as he lay in his bed, and he wished he could kill it.

When his mother was taken sick, he left school and became her nurse. It was hard for him to lay down his books, for he loved them, but it was pleasant to wait upon her. The neighbors were kind. Azalia Adams often came tripping in with something nice,—a tumbler of jelly, or a plate of toast, which her mother had prepared; and she had such cheerful words, and spoke so pleasantly, and moved round the room so softly, putting everything in order, that the room was lighter, even on the darkest days, for her presence.

When, after weeks of confinement to her bed, Paul’s mother was strong enough to sit in her easy-chair, Paul went out to fight the wolf. He worked for Mr. Middlekauf, in his cornfield. He helped Mr. Chrome paint wagons. He surveyed land, and ran lines for the farmers, earning a little here and a little there. As fast as he obtained a dollar, it went to pay the debts. As the seasons passed away,—spring, summer, and autumn,—Paul could see that the wolf grew smaller day by day. He denied himself everything, except plain food. He was tall, stout, hearty, and rugged. The winds gave him health; his hands were hard, but his heart was tender. When through his day’s work, though his bones ached and his eyes were drowsy, he seldom went to sleep without first studying awhile, and closing with a chapter from the Bible, for he remembered what his grandfather often said,—that a chapter from the Bible was a good thing to sleep on.

The cool and bracing breezes of November, the nourishing food which Paul obtained, brought the color once more to his mother’s cheeks; and when at length she was able to be about the house, they had a jubilee,—a glad day of thanksgiving,—for, in addition to this blessing of health, Paul had killed the wolf, and the debts were all paid.

As the winter came on, the subject of employing Mr. Rhythm to teach a singing-school was discussed. Mr. Quaver, a tall, slim man, with a long, red nose, had led the choir for many years. He had a loud voice, and twisted his words so badly, that his singing was like the blare of a trumpet. On Sundays, after Rev. Mr. Surplice read the hymn, the people were accustomed to hear a loud Hawk! from Mr. Quaver, as he tossed his tobacco-quid into a spittoon, and an Ahem! from Miss Gamut. She was the leading first treble, a small lady with a sharp, shrill voice. Then Mr. Fiddleman sounded the key on the bass-viol, do-mi-sol-do, helping the trebles and tenors climb the stairs of the scale; then he hopped down again, and rounded off with a thundering swell at the bottom, to let them know he was safely down, and ready to go ahead. Mr. Quaver led, and the choir followed like sheep, all in their own way and fashion.

The people had listened to this style of music till they were tired of it. They wanted a change, and decided to engage Mr. Rhythm, a nice young man, to teach a singing-school for the young folks. “We have a hundred boys and girls here in the village, who ought to learn to sing, so that they can sit in the singing-seats, and praise God,” said Judge Adams.

But Mr. Quaver opposed the project. “The young folks want a frolic, sir,” he said; “yes, sir, a frolic, a high time. Rhythm will be teaching them new-fangled notions. You know, Judge, that I hate flummididdles; I go for the good old things, sir. The old tunes which have stood the wear and tear of time, and the good old style of singing, sir.”

Mr. Quaver did not say all he thought, for he could see that, if the singing-school was kept, he would be in danger of losing his position as chorister. But, notwithstanding his opposition, Mr. Rhythm was engaged to teach the school. Paul determined to attend. He loved music.

“You haven’t any coat fit to wear,” said his mother. “I have altered over your grandfather’s pants and vest for you, but I cannot alter his coat. You will have to stay at home, I guess.”

“I can’t do that, mother, for Mr. Rhythm is one of the best teachers that ever was, and I don’t want to miss the chance. I’ll wear grandpa’s coat just as it is.”

“The school will laugh at you.”

“Well, let them laugh, I sha’n’t stay at home for that. I guess I can stand it,” said Paul, resolutely.

The evening fixed upon for the school to commence arrived. All the young folks in the town were there. Those who lived out of the village—the farmers’ sons and daughters—came in red, yellow, and green wagons. The girls wore close-fitting hoods with pink linings, which they called “kiss-me-if-ye-dares.” Their cheeks were all aglow with the excitement of the occasion. When they saw Mr. Rhythm, how pleasant and smiling he was,—when they heard his voice, so sweet and melodious,—when they saw how sprily he walked, as if he meant to accomplish what he had undertaken,—they said to one another, “How different he is from Mr. Quaver!”

Paul was late on the first evening, for when he put on his grandfather’s coat, his mother looked at it a long while to see if there was not some way by which she could make it look better. Once she took the shears and was going to cut off the tail, but Paul stopped her. “I don’t want it curtailed, mother.”

“It makes you look like a little old man, Paul; I wouldn’t go.”

“If I had better clothes, I should wear them, mother; but as I haven’t, I shall wear these. I hope to earn money enough some time to get a better coat; but grandpa wore this, and I am not ashamed to wear what he wore,” he replied, more resolute than ever. Perhaps, if he could have seen how he looked, he would not have been quite so determined, for the sleeves hung like bags on his arms, and the tail almost touched the floor.

Mr. Rhythm had just rapped the scholars to their seats when Paul entered. There was a tittering, a giggle, then a roar of laughter. Mr. Rhythm looked round to see what was the matter, and smiled. For a moment Paul’s courage failed him. It was not so easy to be laughed at as he had imagined. He was all but ready to turn about and leave the room. “No I won’t, I’ll face it out,” he said to himself, walked deliberately to a seat, and looked bravely round, as if asking, “What are you laughing at?”

There was something in his manner which instantly won Mr. Rhythm’s respect, and which made him ashamed of himself for having laughed. “Silence! No more laughing,” he said; but, notwithstanding the command, there was a constant tittering among the girls. Mr. Rhythm began by saying, “We will sing Old Hundred. I want you all to sing, whether you can sing right or not.” He snapped his tuning-fork, and began. The school followed, each one singing,—putting in sharps, flats, naturals, notes, bars, and rests, just as they pleased. “Very well. Good volume of sound. Only I don’t think Old Hundred ever was sung so before, or ever will be again,” said the master, smiling.

Michael Murphy was confident that he sang gloriously, though he never varied his tone up or down. He was ciphering in fractions at school, and what most puzzled him were the figures in the bars. He wondered if 6/4 was a vulgar fraction, and if so, he thought it would be better to express it as a mixed number, 1½.

During the evening, Mr. Rhythm, noticing that Michael sang without any variation of tone, said, “Now, Master Murphy, please sing la with me”;—and Michael sang bravely, not frightened in the least.

“Very well. Now please sing it a little higher.”

“La,” sang Michael on the same pitch, but louder.

“Not louder, but higher.”

“La!” responded Michael, still louder, but with the pitch unchanged.

There was tittering among the girls.

“Not so, but thus,”—and Mr. Rhythm gave an example, first low, then high. “Now once more.”

“LA!” bellowed Michael on the same pitch.

Daphne Dare giggled aloud, and the laughter, like a train of powder, ran through the girls’ seats over to the boys’ side of the house, where it exploded in a loud haw! haw! Michael laughed with the others, but he did not know what for.

Recess came. “Halloo, Grandpa! How are you, Old Pensioner? Your coat puckers under the arms, and there is a wrinkle in the back,” said Philip Funk to Paul. His sister Fanny pointed her finger at him; and Paul heard her whisper to one of the girls, “Did you ever see such a monkey?”

It nettled him, and so, losing his temper, he said to Philip, “Mind your business.”

“Just hear Grandaddy Parker, the old gentleman in the bob-tailed coat,” said Philip.

“You are a puppy,” said Paul. But he was vexed with himself for having said it. If he had held his tongue, and kept his temper, and braved the sneers of Philip in silence, he might have won a victory; for he remembered a Sunday-school lesson upon the text, “He that ruleth his spirit is greater than he that taketh a city.” As it was, he had suffered a defeat, and went home that night disgusted with himself.

Pleasant were those singing-school evenings. Under Mr. Rhythm’s instructions the young people made rapid progress. Then what fine times they had at recess, eating nuts, apples, and confectionery, picking out the love-rhymes from the sugar-cockles!

“I cannot tell the love

I feel for you, my dove,”

was Philip’s gift to Azalia. Paul had no money to purchase sweet things at the store; his presents were nuts which he had gathered in the autumn. In the kindness of his heart he gave a double-handful to Philip’s sister, Fanny; but she turned up her nose, and let them drop upon the floor.

Society in New Hope was mixed. Judge Adams, Colonel Dare, and Mr. Funk were rich men. Colonel Dare was said to be worth a hundred thousand dollars. No one knew what Mr. Funk was worth; but he had a store, and a distillery, which kept smoking day and night and Sunday, without cessation, grinding up corn, and distilling it into whiskey. There was always a great black smoke rising from the distillery-chimney. The fires were always roaring, and the great vats steaming. Colonel Dare made his money by buying and selling land, wool, corn, and cattle. Judge Adams was an able lawyer, known far and near as honest, upright, and learned. He had had a great practice; but though the Judge and Colonel were so wealthy, and lived in fine houses, they did not feel that they were better than their neighbors, so that there was no aristocracy in the place, but the rich and the poor were alike respected and esteemed.

The New Year was at hand, and Daphne Dare was to give a party. She was Colonel Dare’s only child,—a laughing, blue-eyed, sensible girl, who attended the village school, and was in the same class with Paul.

“Whom shall I invite to my party, father?” she asked.

“Just whom you please, my dear,” said the Colonel.

“I don’t know what to do about inviting Paul Parker. Fanny Funk says she don’t want to associate with a fellow who is so poor that he wears his grandfather’s old clothes,” said Daphne.

“Poverty is not a crime, my daughter. I was poor once,—poor as Paul is. Money is not virtue, my dear. It is a good thing to have; but persons are not necessarily bad because they are poor, neither are they good because they are rich,” said the Colonel.

“Should you invite him, father, if you were in my place?”

“I do not wish to say, my child, for I want you to decide the matter yourself.”

“Azalia says that she would invite him; but Fanny says that if I invite him, she shall not come.”

“Aha!” The Colonel opened his eyes wide. “Well, my dear, you are not to be influenced wholly by what Azalia says, and you are to pay no attention to what Fanny threatens. You make the party. You have a perfect right to invite whom you please; and if Fanny don’t choose to come, she has the privilege of staying away. I think, however, that she will not be likely to stay at home even if you give Paul an invitation. Be guided by your own sense of right, my darling. That is the best guide.”

“I wish you’d give Paul a coat, father. You can afford to, can’t you?”

“Yes; but he can’t afford to receive it.” Daphne looked at her father in amazement. “He can’t afford to receive such a gift from me, because it is better for him to fight the battle of life without any help from me or anybody else at present. A good man offered to help me when I was a poor boy; but I thanked him, and said, ‘No, sir.’ I had made up my mind to cut my own way, and I guess Paul has made up his mind to do the same thing,” said the Colonel.

“I shall invite him. I’ll let Fanny know that I have a mind of my own,” said Daphne, with determination in her voice.

Her father kissed her, but kept his thoughts to himself. He appeared to be pleased, and Daphne thought that he approved her decision.

The day before New Year Paul received a neatly folded note, addressed to Mr. Paul Parker. How funny it looked! It was the first time in his life that he had seen “Mr.” prefixed to his name. He opened it, and read that Miss Daphne Dare would receive her friends on New Year’s eve at seven o’clock. A great many thoughts passed through his mind. How could he go and wear his grandfather’s coat? At school he was on an equal footing with all; but to be one of a party in a richly furnished parlor, where Philip, Fanny, and Azalia, and other boys and girls whose fathers had money, could turn their backs on him and snub him, was very different. It was very kind in Daphne to invite him, and ought he not to accept her invitation? Would she not think it a slight if he did not go? What excuse could he offer if he stayed away? None, except that he had no nice clothes. But she knew that, yet she had invited him. She was a true-hearted girl, and would not have asked him if she had not wanted him. Thus he turned the matter over, and decided to go.

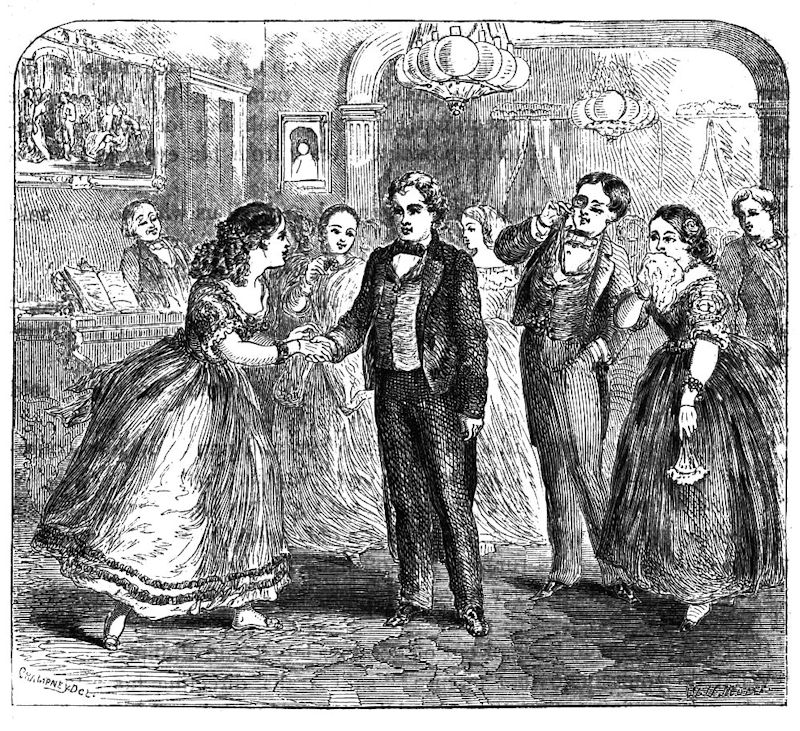

But when the time came, Paul was in no haste to be there. Two or three times his heart failed him, while on his way; but looking across the square, and seeing Colonel Dare’s house all aglare,—lights in the parlors and chambers, he pushed on resolutely, determined to be manly, notwithstanding his poverty. He reached the house, rang the bell, and was welcomed by Daphne in the hall.

“Good evening, Paul. You are very late. I was afraid you were not coming. All the others are here,” she said, her face beaming with happiness, joy, and excitement. She was elegantly dressed, for she was her father’s pet, and he bought everything for her which he thought would make her happy.

“Better late than never, isn’t it?” said Paul, not knowing what else to say.

Although the party had been assembled nearly an hour, there had been no games. The girls were huddled in groups on one side of the room, and the boys on the other, all shy, timid, and waiting for somebody to break the ice. Azalia was playing the piano, while Philip stood by her side. He was dressed in a new suit of broadcloth, and wore an eye-glass. Fanny was present, though she had threatened not to attend if Paul was invited. She had altered her mind. She thought it would be better to attend and make the place too hot for Paul; she would get up such a laugh upon him that he would be glad to take his hat and sneak away, and never show himself in respectable society again. Philip was in the secret, and so were a dozen others who looked up to Philip and Fanny. Daphne entered the parlor, followed by Paul. There was a sudden tittering, snickering, and laughing; Paul stopped and bowed, then stood erect.

“I declare, if there isn’t old Grandaddy,” said Philip, squinting through his eye-glass.

“O my! how funny!” said a girl from Fairview.

“Ridiculous! It is a shame!” said Fanny, turning up her nose.

“Who is he?” the Fairview girl asked.

“A poor fellow who lives on charity,—so poor that he wears his grandfather’s old clothes. We don’t associate with him,” was Fanny’s reply.

Paul heard it. His cheek flushed, but he stood there, determined to brave it out. Azalia heard and saw it all. She stopped playing in the middle of a measure, ran from her seat with her cheeks all aflame, and walked towards Paul, extending her hand and welcoming him. “I am glad you have come, Paul. We want you to wake us up. We have been half asleep.”

The laughter ceased instantly, for Azalia was a queen among them. Beautiful in form and feature, her chestnut hair falling in luxuriant curls upon her shoulders, her dark hazel eyes flashing indignantly, her cheeks like blush-roses, every feature of her countenance lighted up by the excitement of the moment, her bearing subdued the conspiracy at once, hushing the derisive laughter, and compelling respect, not only for herself, but for Paul. It required an effort on his part to keep back the tears from his eyes, so grateful was he for her kindness.

“Yes, Paul, we want you to be our general, and tell us what to do,” said Daphne.

“Very well, let us have Copenhagen to begin with,” he said.

The ice was broken. Daphne brought in her mother’s clothes-line, the chairs were taken from the room, and in five minutes the parlor was humming like a beehive.

“I don’t see what you can find to like in that disagreeable creature,” said Philip to Azalia.

“He is a good scholar, and kind to his mother, and you know how courageous he was when he killed that terrible dog,” was her reply.

“I think he is an impudent puppy. What right has he to thrust himself into good company, wearing his grandfather’s old clothes?” Philip responded, dangling his eye-glass and running his soft hand through his hair.

“Paul is poor; but I never have heard anything against his character,” said Azalia.

“Poor folks ought to be kept out of good society,” said Philip.

“What do you say to that picture?” said Azalia, directing his attention towards a magnificent picture of Franklin crowned with laurel by the ladies of the court of France, which hung on the wall. “Benjamin Franklin was a poor boy, and dipped candles for a living; but he became a great man.”

“Dipped candles! Why, I never heard of that before,” said Philip, looking at the engraving through his eye-glass.

“I don’t think it is any disgrace to Paul to be poor. I am glad that Daphne invited him,” said Azalia, so resolutely that Philip remained silent. He was shallow-brained and ignorant, and thought it not best to hazard an exposure of his ignorance by pursuing the conversation.

After Copenhagen they had Fox and Geese, and Blind-man’s-buff. They guessed riddles and conundrums, had magic writing, questions and answers, and made the parlor, the sitting-room, the spacious halls, and the wide stairway ring with their merry laughter. How pleasant the hours! Time flew on swiftest wings. They had a nice supper,—sandwiches, tongue, ham, cakes, custards, floating-islands, apples, and nuts. After supper they had stories, serious and laughable, about ghosts and witches, till the clock in the dining-room held up both of its hands and pointed to the figure twelve, as if in amazement at their late staying. “Twelve o’clock! Why, how short the evening has been!” said they, when they found how late it was. They had forgotten all about Paul’s coat, for he had been the life of the party, suggesting something new when the games lagged. He was so gentlemanly, and laughed so heartily and pleasantly, and was so wide awake, and managed everything so well, that, notwithstanding the conspiracy to put him down, he had won the good-will of all the party.

During the evening Colonel Dare and Mrs. Dare entered the room. The Colonel shook hands with Paul, and said, “I am very happy to see you here to-night, Paul.” It was spoken so heartily and pleasantly that Paul knew the Colonel meant it.

The young gentlemen were to wait upon the young ladies home. Their hearts went pit-a-pat. They thought over whom to ask and what to say. They walked nervously about the hall, pulling on their gloves, while the girls were putting on their cloaks and hoods up stairs. They also were in a fever of expectation and excitement, whispering mysteriously, their hearts going like trip-hammers.

Daphne stood by the door to bid her guests good night. “I am very glad that you came to-night, Paul,” she said, pressing his hand in gratitude, “I don’t know what we should have done without you.”

“I have passed a very pleasant evening,” he replied.

Azalia came tripping down the stairs. “Shall I see you home, Azalia?” Paul asked.

“Miss Adams, shall I have the delightful pleasure of being permitted to escort you to your residence?” said Philip, with his most gallant air, at the same time pushing by Paul with a contemptuous look.

“Thank you both for your courtesy,” said Azalia, “but I think I shall accept Paul’s offer”;—and putting her slender arm through his sturdy one, she passed out of the doorway, leaving Philip to console himself at his deserved discomfiture as best he could.

Paul was a proud and happy youth as he went out into the street with Azalia under his charge, among the lively groups busy with their comments upon the enjoyments of the party and their good-nights as they separated on their homeward ways. The night was frosty and cold, but it was clear and pleasant. The full moon was high in the heavens, the air was still, and there were no sounds to break the peaceful silence of the winter night, except the water dashing over the dam by the mill, the footsteps of the departing guests upon the frozen ground, and the echoing of their voices. Now that he was with Azalia alone, he wanted to tell her how grateful he was for all she had done for him; but he could only say, “I thank you, Azalia, for your kindness to me to-night.”

“O, don’t mention it, Paul; I am glad if I have helped you. Good night.”

How light-hearted he was! He went home, and climbed the creaking stairway, to his chamber. The moon looked in upon him, and smiled. He could not sleep, so happy was he. How sweet those parting words! The water babbled them to the rocks, and beyond the river in the grand old forest, where the breezes were blowing, there was a pleasant murmuring of voices, as if the elms and oaks were having a party, and all were saying, “We are glad if we have helped you.”

Carleton.

From his dream Mihal was waked by a loud hiss, and, starting to his feet, he saw that the moon shone like day on a goose with brilliant crimson wings, followed by six snow-white goslings, just disappearing in the forest. He did not wait to rub his eyes, but darted away on the track of the birds as fast as he could go, still keeping the nearest one in sight. Nothing could tire his patience or wear out his courage; the crooked roots of the old beech-trees seemed to crawl and twist purposely before his eager little feet, and more than once the low brambles of the forest scratched his face sharply as he fell forward among them. But Mihal had a stout heart; he scrambled up as he best might, and pursued the goslings with fresh ardor over hill and valley, far beyond the pine forest, and skirting its borders, till at length he found himself at dawn near the same hill where he had entered the dwarfs’ cave, and as he followed the goslings up the hill-side, slippery with dry grass, he fell at length by the bubbling fountain. Tears of fatigue and discouragement came into his eyes; but as he raised his head slowly from the ground, lo! there on the edge of the spring sat the goose and her brood, wellnigh as tired as he. Mihal stretched his hand forward slowly and softly, till he grasped the snowy down of the gosling that sat nearest him, and twisted a finger about its neck; the goose and goslings sailed away, flapping their wings heavily, and Mihal tied his treasure tightly and safely with a little leathern thong, wondering where he should bestow it, when he heard a voice at his ear, and, turning, saw the grizzled head of the Dwarf-king, set, as it might be, under a round stone in the hill-side, with his little glittering eyes fixed on the child’s prize. In fact the king was looking out of his chamber window, only that happened to be under a stone, and as Mihal saw the outside alone, nor could guess at the inside, he was naturally a little startled, though he laughed and held up the gosling in triumph. The dwarf nodded at Mihal, and asked him in to breakfast, for he was mightily in good-humor that morning because his miners had found a carbuncle as big as a goose-egg the day before, and brought news of a streak of pure gold right across the nearest mountain; moreover, he offered to keep the goslings for him, give him a good meal whenever he came to bring one, and told him always to wait for them by the forest cross, as they flew by there every night after moon-rise. So the boy dropped an acorn into the fountain, and the little old woman came to the door and let him in. He saw his bird safely caged, ate an excellent breakfast, and then trudged home to find his brothers and sisters still asleep; so he stole in to his own corner and slept too, till noon, for his mother wisely thought he had better sleep than eat.

The next night, after much the same adventures, he caught another gosling on the bough of a fir-tree far beyond the pine-forest, and carried it for many a mile before he reached the Dwarf-king’s hill; and then, after his warm breakfast, the day was so far gone he did not care to go home, but made a nest of dry leaves under a great tree, and took a long nap in the sunshine. Nor did he leave the forest till night, for with an oaten cake and a bit of smoked boar’s flesh that remained from his breakfast, and the sweet water of the spring, he supped like a lord. But by sunset he hastened home to find his mother watching without the hut, her hand shading her eyes from the level rays, and her mother-heart sore lest some evil had befallen her little lad. Mihal feigned to eat his crust with the others, but put it slyly into Zitza’s hand, told the others stories till they slept, and then made his way through the woods and the midnight, as well as he might, to his place of waiting. Very dark and rustling was the old forest that night, full of sighs and whispers and moaning winds; the boy’s heart shivered, and his flesh crept, for he was cold and weary, and as he sat down beside the stone cross the shadows closed and pressed upon him till he could scarce breathe, and a chill sweat stood all over him. How in this black darkness was he to see the birds he came to pursue?

Suddenly a whir of wings freshened the heavy air, the glittering white of the goslings’ plumage shone even in that deep gloom, and from the red wings of the goose herself a tender, rosy light spread and glowed like a wandering sunset-cloud. Mihal remembered no more cold, or darkness, or fear, but started to his feet and pursued his chase as manfully as ever. This time they took a new track, deep into the heart of the forest, and sorely was Mihal’s patience tried to follow them. Sometimes, just as the last one seemed to be within reach, his eager hands would close over a feather fallen from its wings, or a lock of wool caught from some lost sheep, instead of the bird he grasped at, and in the uncertain light that struggled through the thick boughs it was not always easy to see even the nearest gosling; but as day began to dawn, this strange hunt and child hunter came out of the forest into a gray and dismal marsh, through which ran slowly a muddy stream, winding through tussocks of coarse grass. On its brink the birds lighted to drink, and Mihal stole carefully up behind them, sure at last of success. They stood quite still, eagerly drinking, all unaware of the enemy behind them, while he, careless of the dwarf’s directions, and anxious for the prey, determined this time to catch two instead of one, and stretching out his left hand toward the nearest, grasped with his right at another; but, poor child! so sure of the nearest was he, that, in trying first to seize the other, he fell full length in the soft black mud of the marsh, and the goslings, taking wing, were out of sight before Mihal, his face plastered with mire, could pick himself up from the side of the stream and see whither they went.

When he found they were really gone, he sat down on a stone and began to cry bitterly. Cold and hungry, tired out, disappointed, conscious withal that his fault lay beneath his failing, he was near to despair, and knew not how to look for comfort, when in the midst of his distress he heard a short, sharp laugh close at his side, and, looking up, perceived the Dwarf-king right before him, holding a square mirror, over which peered his keen, twinkling eyes and grizzled head circled with the ring of gold.

“Look here, child!” said he, tapping the frame of the mirror. Mihal looked, and beheld therein his own piteous figure perched upon a rugged stone, his old baize jacket more torn and soiled than ever, his coarse hat of oaten straw bruised and askew over one ear, his face daubed with mud, through which the tears made little paths till he was well striped in black and white. A funny sight he was to see, and while he kept looking at this quaint vision he forgot to cry, began to smile, and at last laughed outright; for surely it was a sight to make any stone saint in Prague Cathedral shake his hard sides with rocky laughter.

“There,” quoth the Dwarf-king, “a laugh is as good as a loaf; the toad-marsh needs no salting of tears; take heart, little lad, take heart! Wash thy face and gather grace,—‘There is always life for a living one!’”

Mihal rid his features of their stripes, tucked away the tangled curls of his hair, and turned again to the mirror with a smile that showed his small white teeth, glittered in his sloe-black eyes, and printed many a dimple deep in his rosy cheeks and chin; the thousand tiny bells on the mirror frame tinkled for joy, and the dwarf pulled out of his snake-skin pouch some savory meat and cakes, with which the child refreshed himself heartily and well. But Mihal was not spared a good rating after all the food had vanished.

“Thou art a pretty one,” said the dwarf, “to keep counsel and follow fortune; but he that breaks his arms must needs hold by his teeth, and he that hath two must also have seven, though it be seven years seeking. Four nights must pass before yonder spell-ridden bird may again see the pine-tree and the Fountain of Silence, and the bird that is frighted is swift of flight thereafter. Still, I counsel thee to go forward.”

Mihal hung his head, and made a reverence to the dwarf, while with his eyes he looked his gratitude, and also his fresh resolve. The little king showed him a short way homeward, and suddenly disappeared just as a slant ray from the new-risen sun touched the spot where he stood; for these hill people love not sunshine,—it does not jingle or feel heavy, and it mocks them with its yellow brightness. Mihal made his way home, and for four nights tossed wearily upon the straw under his sheepskin blanket. In vain the waning moon shone through the crevices of the hut, in vain the mild night-airs from the pine-trees breathed their mystic fragrance abroad. He would not now despise the dwarf’s wisdom, he would wait if he might not watch or pursue. At last the fifth night came, and long before the late moonrise Mihal leaned against the forest cross. High overhead, the stars marched through the purple heaven in glittering state and splendor, and meteors spun their threads of fiery light from planet to planet, as bent on some celestial errand; but soon clouds gathered above the lonely earth, storm-rack fleeted through the vaults of air, gusts of wind bent the forest, that sighed and groaned before the gale; afar off the howl of a wolf added another discord to the tempest-chorus, and the wild yell of the witch-owl, or the scream of a benighted eagle driven by the powers of air from his eyrie, smote Mihal’s heart with terror, and filled his soul with dread. A sob of fright burst from his lips, but a voice of good cheer beside him said, “Patience!” and as the word fell on his ear he heard the rush of the goose’s wings, a dull red light gleamed in the north and spread along the clouds, and once more his chase began.

Long, long, and dreary it was this time; sometimes he thought the birds would never light, to rest or drink; on and on they flew, while on and on he followed, though his head whirled, and his heart beat as if it would break. At last the line of the goose’s flight led past a thick cedar whose boughs swept the ground, and the last gosling, swerving a little from the line, flew headlong into the thickest branches, and before it could flutter itself free was safe clutched in Mihal’s two hands. Speedily he made his way to the Dwarf-king with his treasure, had his sore and bleeding feet anointed and bound up carefully, was well warmed and fed, and freely praised by the little master for his good-will and courage.

It would take long, and too long, to tell how slowly Mihal caught the other three; what mountain ridges rose up in his path and daunted his bravery for a time; what trackless forests, what desert heaths, what solitary lakes on whose margin the heron stalked and the gull screamed, what mighty rolling rivers, were traversed and passed in his nightly chases; but he that keeps his eyes open and his mouth shut comes at last to bed and table, though it be never so long first; and when Mihal grasped the sixth gosling on the shore of a dark inland sea, sombre with the shadow of overhanging cliffs, the red-winged goose herself, loath to leave the last of her brood, lighted upon his shoulder, and he carried her home in triumph.

Once there, he built for her a large and light cage of little pine-boughs, and strewed its floor with sweet leaves of fir and birch, where the beautiful bird contented herself, and erelong laid therein snowy eggs like any other goose. These Mihal carefully stored, and when he had a goodly number sent them to the land-steward of a great lord who had a castle in that country. Now this mightily pleased the land-steward, who above all things liked fried goose-eggs for his supper,—so much that he sent for Mihal to come and live with him, and also bestowed food upon the eight children, and five roods of good land upon Otto Koenig.

Mihal lived with him till he became as his son, and, after years enough had passed to make the boy a man, the land-steward made him under-bailiff on the great lord his master’s estate, and built him there a nice wooden house with two windows and a door that would shut. Here Mihal lived for some time with only the red-winged goose and Zitza for company, but Zitza needs must marry and go away, so Mihal asked the land-steward’s pretty daughter to marry him. Hanne had much ado to say “No,” as modest maidens should, even if they say “Yes” after, as she did; so the banns were read, and they were wedded, like all good people, with priest and mass-book.

The Dwarf-king was seen no more; long ago had he eaten a goose-pie of marvellous flavor, made from the six goslings, that Mihal dressed and the jackdaw woman compounded into the pastry with spices abundant, and crispy crust; and maybe it was in return for this that on Mihal’s wedding-day a red apron curiously wrought with gold and silk threads fell down the chimney right into Hanne’s lap. Mihal at least believed it was the Dwarf-king’s present, for the like of it had never been seen in all Bohemia, and whenever the little wife put it on, all house-matters went smoothly and right.

And there never was but one thing that troubled Hanne about her man, in all their long life; but alas! if ever she made a pudding before she cleaned the pot, if ever she poured in the cream before she scalded the churn, if ever she went to mass before the children were washed and fed, or rated a beggar from the door and bought the Virgin in the castle chapel a costly offering, Mihal would shake his head and say, “Hanne! Hanne! thou shouldst catch the nearest one first!” Nor could either tears or kisses persuade him to tell her what this strange speech meant. So everybody must allow she was an ill-used woman, as all women are—when they think so!

And this is all, about The Red-Winged Goose.

Rose Terry.

Out of the deeps of heaven

A bird has flown to my door,

As twice in the ripening summers

Its mates have flown before!

Why it has flown to my dwelling,

Nor it nor I may know;

And only the silent angels

Can tell when it shall go!

That it will not straightway vanish,

But fold its wings with me,

And sing in the greenest branches

Till the axe is laid to the tree,

Is the prayer of my love and terror,

For my soul is sore distrest,

Lest I wake some dreadful morning,

And find but its empty nest!

R. H. Stoddard.

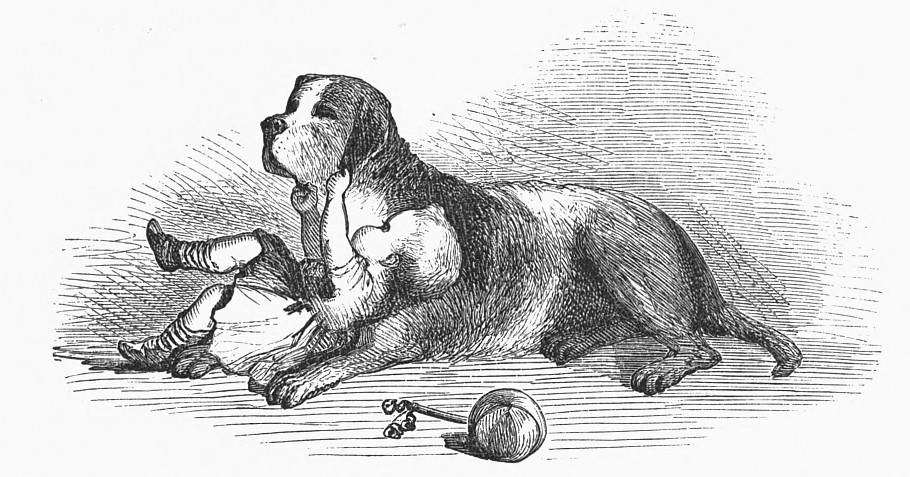

We who live in Cunopolis are a dog-loving family. We have a warm side towards everything that goes upon four paws, and the consequence has been that, taking things first and last, we have been always kept in confusion and under the paw, so to speak, of some honest four-footed tyrant, who would go beyond his privilege and overrun the whole house. Years ago this begun, when our household consisted of a papa, a mamma, and three or four noisy boys and girls, and a kind Miss Anna who acted as a second mamma to the whole. There was also one more of our number, the youngest, dear little bright-eyed Charley, who was king over us all, and rode in a wicker wagon for a chariot, and had a nice little nurse devoted to him; and it was through him that our first dog came.

One day Charley’s nurse took him quite a way to a neighbor’s house, to spend the afternoon; and, he being well amused, they stayed till after nightfall. The kind old lady of the mansion was concerned that the little prince in his little coach, with his little maid, had to travel so far in the twilight shadows, and so she called a big dog named Carlo, and gave the establishment into his charge.

Carlo was a great, tawny-yellow mastiff, as big as a calf, with great, clear, honest eyes, and stiff, wiry hair; and the good lady called him to the side of the little wagon, and said, “Now, Carlo, you must take good care of Charley, and you mustn’t let anything hurt him.”

Carlo wagged his tail in promise of protection, and away he trotted, home with the wicker wagon; and when he arrived, he was received with so much applause by four little folks, who dearly loved the very sight of a dog, he was so stroked and petted and caressed, that he concluded that he liked the place better than the home he came from, where were only very grave elderly people. He tarried all night, and slept at the foot of the boys’ bed, who could hardly go to sleep for the things they found to say to him, and who were awake ever so early in the morning, stroking his rough, tawny back, and hugging him.

At his own home Carlo had a kennel all to himself, where he was expected to live quite alone, and do duty by watching and guarding the place. Nobody petted him, or stroked his rough hide, or said “Poor dog!” to him, and so it appears he had a feeling that he was not appreciated, and liked our warm-hearted little folks, who told him stories, gave him half of their own supper, and took him to bed with them sociably. Carlo was a dog that had a mind of his own, though he couldn’t say much about it, and in his dog fashion proclaimed his likes and dislikes quite as strongly as if he could speak. When the time came for taking him home, he growled and showed his teeth dangerously at the man who was sent for him, and it was necessary to drag him back by force, and tie him into his kennel. However, he soon settled that matter by gnawing the rope in two and padding down again and appearing among his little friends, quite to their delight. Two or three times was he taken back and tied or chained; but he howled so dismally, and snapped at people in such a misanthropic manner, that finally the kind old lady thought it better to have no dog at all than a dog soured by blighted affection. So she loosed his rope, and said, “There, Carlo, go and stay where you like”; and so Carlo came to us, and a joy and delight was he to all in the house. He loved one and all; but he declared himself as more than all the slave and property of our little Prince Charley. He would lie on the floor as still as a door-mat, and let him pull his hair, and roll over him, and examine his eyes with his little fat fingers; and Carlo submitted to all these personal freedoms with as good an understanding as papa himself. When Charley slept, Carlo stretched himself along under the crib; rising now and then, and standing with his broad breast on a level with the slats of the crib, he would look down upon him with an air of grave protection. He also took a great fancy to papa, and would sometimes pat with tiptoe care into his study, and sit quietly down by him when he was busy over his Greek or Latin books, waiting for a word or two of praise or encouragement. If none came, he would lay his rough horny paw on his knee, and look in his face with such an honest, imploring expression, that the Professor was forced to break off to say, “Why, Carlo, you poor, good, honest fellow,—did he want to be talked to?—so he did. Well, he shall be talked to;—he’s a nice good dog”;—and during all these praises Carlo’s transports and the thumps of his rough tail are not to be described.

He had great, honest yellowish-brown eyes,—not remarkable for their beauty, but which used to look as if he longed to speak, and he seemed to have a yearning for praise and love and caresses that even all our attentions could scarcely satisfy. His master would say to him sometimes, “Carlo, you poor, good, homely dog,—how loving you are!”

Carlo was a full-blooded mastiff,—and his beauty, if he had any, consisted in his having all the good points of his race. He was a dog of blood, come of real old mastiff lineage; his stiff, wiry hair, his big, rough paws, and great brawny chest, were all made for strength rather than beauty; but for all that he was a dog of tender sentiments. Yet, if any one intruded on his rights and dignities, Carlo showed that he had hot blood in him; his lips would go back, and show a glistening row of ivories, that one would not like to encounter, and if any trenched on his privileges, he would give a deep warning growl,—as much as to say, “I am your slave for love,—but you must treat me well, or I shall be dangerous.” A blow he would not bear from any one: the fire would flash from his great yellow eyes, and he would snap like a rifle;—yet he would let his own Prince Charley pound on his ribs with both baby fists, and pull his tail till he yelped, without even a show of resistance.

At last came a time when the merry voice of little Charley was heard no more, and his little feet no more pattered through the halls; he lay pale and silent in his little crib, with his dear life ebbing away, and no one knew how to stop its going. Poor old Carlo lay under the crib when they would let him, sometimes rising up to look in with an earnest, sorrowful face; and sometimes he would stretch himself out in the entry before the door of little Charley’s room, watching with his great open eyes lest the thief should come in the night to steal away our treasure.

But one morning when the children woke, one little soul had gone in the night,—gone upward to the angels; and then the cold, pale, little form that used to be the life of the house was laid away tenderly in the yard of a neighboring church.

Poor old Carlo would pit-pat silently about the house in those days of grief, looking first into one face and then another, but no one could tell him where his gay little master had gone. The other children had hid the baby-wagon away in the lumber-room lest their mamma should see it; and so passed a week or two, and Carlo saw no trace of Charley about the house. But then a lady in the neighborhood, who had a sick baby, sent to borrow the wicker wagon, and it was taken from its hiding-place to go to her. Carlo came to the door just as it was being drawn out of the gate into the street. Immediately he sprung, cleared the fence with a great bound, and ran after it. He overtook it, and poked his head between the curtains,—there was no one there. Immediately he turned away, and padded dejectedly home. What words could have spoken plainer of love and memory than this one action?

Carlo lived with us a year after this, when a time came for the whole family hive to be taken up and moved away from the flowery banks of the Ohio, to the piny shores of Maine. All our household goods were being uprooted, disordered, packed, and sold; and the question daily arose, “What shall we do with Carlo?” There was hard begging on the part of the boys that he might go with them, and one even volunteered to travel all the way in baggage cars to keep Carlo company. But papa said no, and so it was decided to send Carlo up the river to the home of a very genial lady who had visited in our family, and who appreciated his parts, and offered him a home in hers.

The matter was anxiously talked over one day in the family circle while Carlo lay under the table, and it was agreed that papa and Willie should take him to the steamboat landing the next morning. But the next morning, Mr. Carlo was nowhere to be found. In vain was he called, from garret to cellar; nor was it till papa and Willie had gone to the city that he came out of his hiding-place. For two or three days it was impossible to catch him, but after a while his suspicions were laid, and we learned not to speak out our plans in his presence, and so the transfer at last was prosperously effected.

We heard from him once in his new home, as being a highly appreciated member of society, and adorning his new situation with all sorts of dog virtues, while we wended our ways to the coast of Maine. But our hearts were sore for want of him; the family circle seemed incomplete, until a new favorite appeared to take his place, of which I shall tell you next month.

Harriet Beecher Stowe.

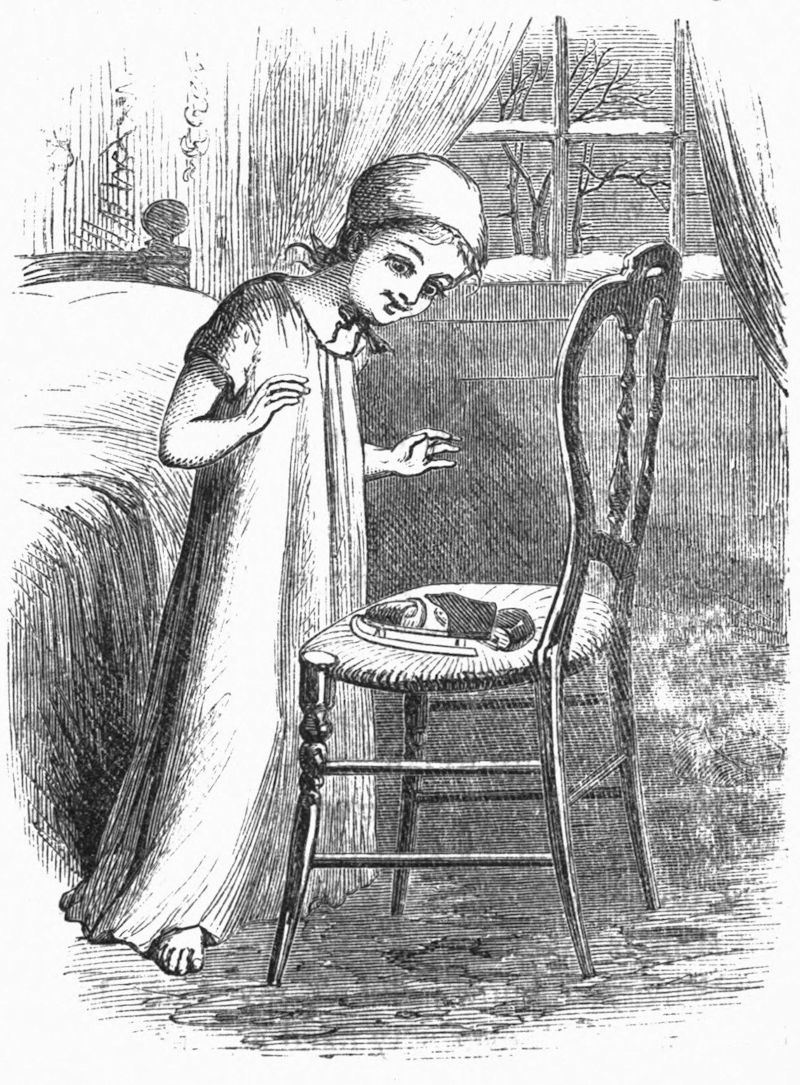

Little Sarah always begged Nurse Day to loop up one of her window-curtains when she went to bed, that she might go to sleep watching the stars twinkle, and in the morning see the great sun rise, and after he had risen, see if his goldy locks were all on end, as her own often were, when she had forgotten to put on her cambric cap the previous night. So one morning she awoke, not quite as early as usual, and found her room full of light, which seemed to dance about some bright object on a chair by her bedside, but which she was at first too sleepy to investigate; for a moment she lay quite still, thinking that perhaps it was some fairy’s wand which caused such a glitter, and that presently a real live fairy, with beautiful gold wings, would perch on her thumb and offer to grant her three wishes, like other obliging fairies she had read about. And the very first wish that came into her head was for a pair of skates; and having got fairly awake at last, behold! what was this same bright something by her bedside, but a handsome new pair of skates,—indeed, so bright that she could see her own face in them!

“O my! how nice! A real pair of skates!” and she was out of bed in the twinkling of an eye, and vainly trying to strap them upon her tiny bare feet; but finding herself unskilful, she pattered across the room, opened the door, and called, “Nurse Day, please come and dress little Sarah, she’s broad awake,—come quick!”

“Here I am, honey!” said Nurse, as she came bustling in. “And what’s the hurry? Hungry?”

“Hungry!” repeated Sarah, indignantly; “I’ve got something better to hurry me. Has papa gone to his office?”

“Yes indeed.”

“Then I am glad, for I can go right out on the Park and learn to skate before he comes home. See, Nurse, my beautiful skates! And won’t he be surprised when he comes home round by the Park, and sees me skating just like Mrs. Mason?”

“I should think so,” said Nurse Day; “but you’re not going to wear your cap out, honey?”

“O yes,” she answered, “I shall wear my skating-cap, that you crocheted for me!”