* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol. XXXVII No. 1 (July 1850)

Date of first publication: 1850

Author: George R. Graham (editor)

Date first posted: Feb. 1, 2016

Date last updated: Feb. 1, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160201

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

1850.

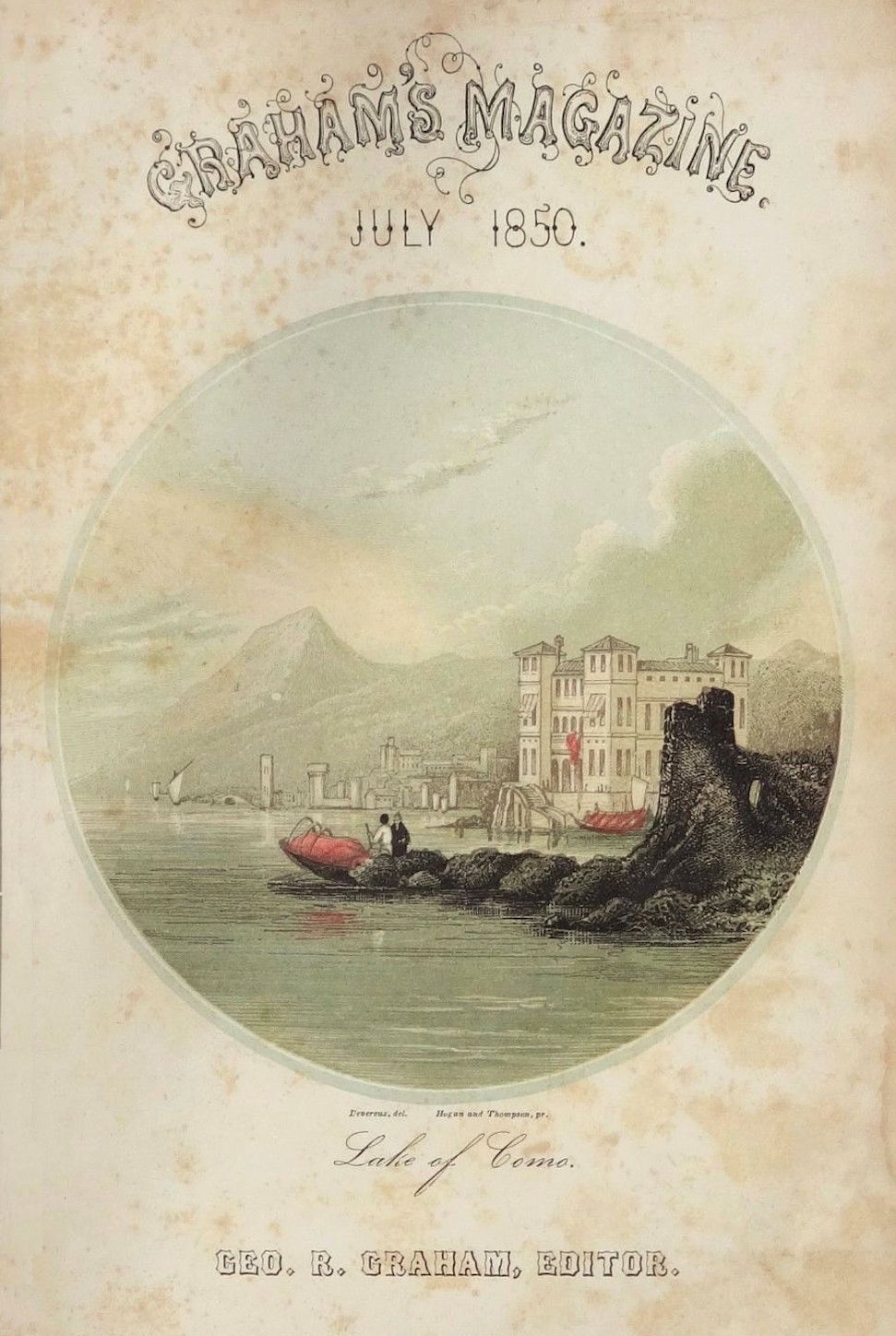

Devereux, del. Hogan and Thompson, pr.

Lake of Como.

GEO. R. GRAHAM, EDITOR.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXVII. July, 1850. No. 1.

Table of Contents

Fiction, Literature and Articles

Poetry, Music, and Fashion

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

CONTENTS

OF THE

THIRTY-SEVENTH VOLUME.

JUNE, 1850, TO JANUARY, 1851.

| A Romance of True Love. By Caroline H. Butler, | 100 | |

| A Visit to Staten Island. By Mrs. Lydia H. Sigourney, | 149 | |

| Bridget Kerevan. By Enna Duval, | 116 | |

| Bay Snipe Shooting. By Frank Forester, | 126 | |

| Blanche of Bourbon. By Walter Brooke, | 348 | |

| Coquet versus Coquette. By Caroline H. Butler, | 177 | |

| Chateaubriand and His Career. By Fayette Robinson, | 356 | |

| Doctrine of Form. By E. | 170 | |

| Edda Murray. By Enna Duval, | 238 | |

| Early English Poets. By James W. Wall, | 250 | |

| Enchanted Beauty. By E. | 265 | |

| For’ard and Aft. By S. A Godman, | 8 | |

| Familiar Quotations from Unfamiliar Sources. By A Student, | 312 | |

| George R. Graham. By C. J. Peterson, | 43 | |

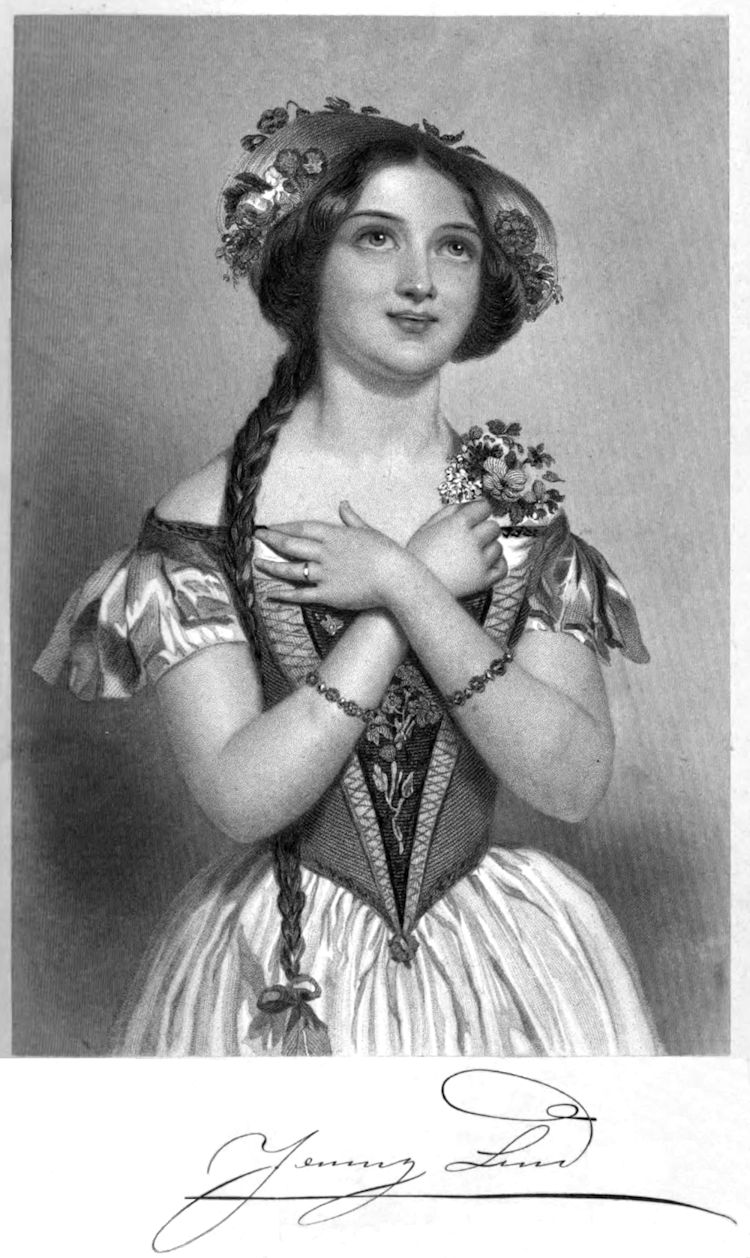

| Jenny Lind. By Henry T. Tuckerman, | 15 | |

| Lucy Leighton. By Caroline H. Butler, | 37 | |

| Music and Musical Composers. By R. J. De Cordova, | 73 | |

| Mandan Indians, | 195 | |

| Music. By Henry Giles, | 223 | |

| Minnie De La Croix. By Angele De V. Hull, | 294, 339 | |

| Nettles on the Grave. By R. Penn Smith, | 311 | |

| Of and Concerning the Moon. By Calvin W. Philleo, | 329 | |

| Pedro de Padilh. By J. M. Legare, | 92, 144, 231, | |

| 305, 372 | ||

| Quail and Quail Shooting. By Henry Wm. Herbert, | 317 | |

| Rail and Rail Shooting. By H. W. Herbert, | 190 | |

| Ruffed Grouse Shooting. By H. W. Herbert, | 382 | |

| Stories from the Old Dramatists. By Enna Duval, | 31 | |

| Shakspeare. By Henry C. Moorhead, | 137 | |

| The Vital and the Mechanical. By P. | 1 | |

| The Bride of the Battle. By Wm. Gilmore Simms, | 23, 84, 163 | |

| The Genius of Burns. By Henry Giles, | 45 | |

| The Gambler’s Daughter. By Henry C. Moorhead, | 53 | |

| The Shark. By L. A. Wilmer, | 64 | |

| The Chase. By Charles J. Peterson, | 79 | |

| The Fine Arts, | 132 | |

| The Genius of Byron. By Rev. J. N. Danforth, | 185 | |

| The Fine Arts, | 193 | |

| The Slave of the Pacha. From Santaine, | 201 | |

| Thomas Johnson. By Thomas Wyatt, A. M. | 245 | |

| Teal and Teal Shooting. By H. W. Herbert, | 256 | |

| The Fine Arts, | 259 | |

| The Vision of Mariotdale. By H. Hastings Weld, | 273 | |

| Tamaque. By Henry C. Moorhead, | 277 | |

| The Sunflower. By Major Richardson, | 285 | |

| Two Crayon Sketches. By Enna Duval, | 314 | |

| Thistle-Down. By Caroline Chesebro’, | 361 | |

| The Comus of Milton. By Rev. J. N. Danforth, | 367 | |

| Woodcock and Woodcock Shooting. By H. W. Herbert, | 61 | |

| Wordsworth. By P. | 106 | |

| What Katy Did. By Caroline Chesebro’, | 121 | |

| Woodlawn. By F. E. F. | 152 | |

| “What Can Woman Do?” By Alice B. Neal, | 158 |

POETRY.

REVIEWS.

| The Life and Correspondence of R. Southey. | ||

| Edited by his son, Rev. C. C. Southey, | 65 | |

| Historic View of the Languages and Literature | ||

| of the Sclavic Nations. By Talvi, | 66 | |

| Indiana. By George Sand, | 67 | |

| Latter-Day Pamphlets. By Thomas Carlyle, | 133 | |

| Webster’s Dictionary, | 133 | |

| Eldorado. By Bayard Taylor, | 134 | |

| In Memoriam, | 198 | |

| Chronicles and Characters of the Stock Exchange. | ||

| By John Francis, | 199 | |

| Evangeline. By Henry W. Longfellow, | 199 | |

| Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy. | ||

| By Rev. Sidney Smith, A. M. | 261 | |

| Confessions of an English Opium Eater. By | ||

| Thomas De Quincy, | 262 | |

| Life and Letters of Thomas Campbell. | ||

| Edited by William Beattie, M. D. | 263 | |

| The Prelude. By William Wordsworth, | 322 | |

| Christian Thought on Life. By Henry Giles, | 323 | |

| Specimens of Newspaper Literature. By J. T. Buckingham, | 324 | |

| Songs of Labor and Other Poems. By J. G. Whittier, | 324 | |

| Memoirs of the Life of Anne Boleyn. By Miss Benger, | 326 | |

| Lynch’s Dead Sea Expedition, | 326 | |

| Astræa. By Oliver Wendall Holmes, | 385 | |

| Five Years of a Hunter’s Life in the Far Interior | ||

| of South Africa. By R. G. Cumming, | 387 |

MUSIC.

| Jenny Lind’s American Polka, | 68 | |

| Chant of the Nereides, | 130 | |

| Barcarole, | 196 | |

| Ah, Do Not Speak so Coldly, | 254 | |

| Come Touch the Harp, My Gentle One, | 388 |

ENGRAVINGS.

| Portrait of Jenny Lind, engraved by Mote, London. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Portrait of the Editor, engraved by Armstrong. | ||

| Lake of Como, executed in colors by Devereux. | ||

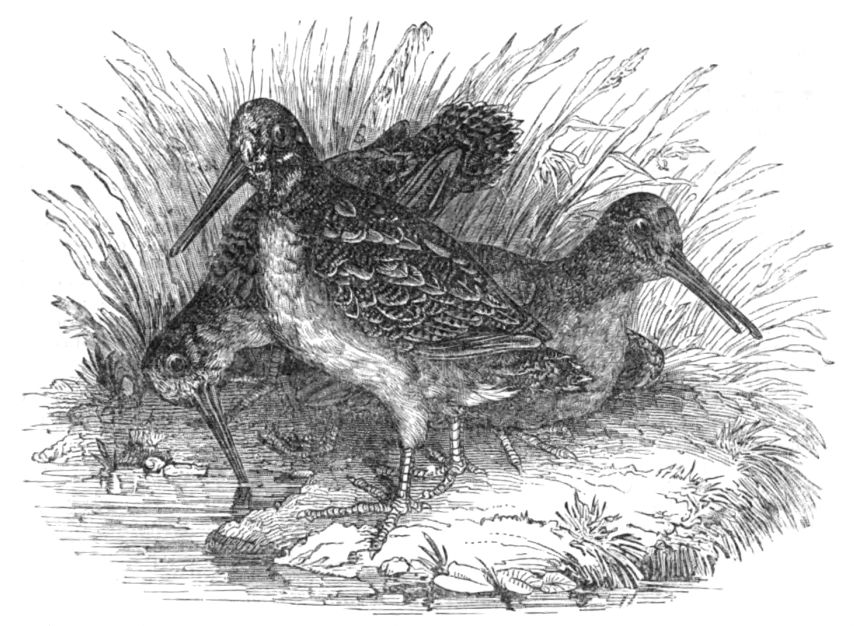

| Woodcock Shooting, engraved by Brightly. | ||

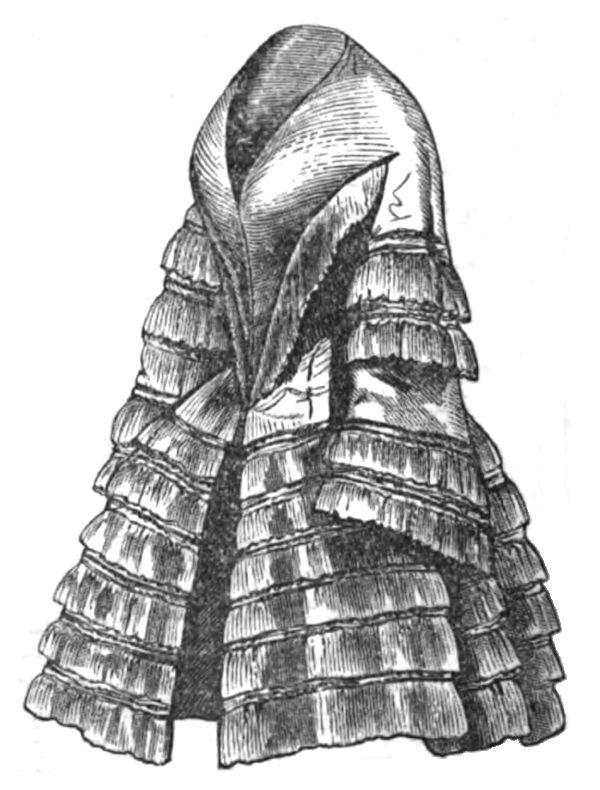

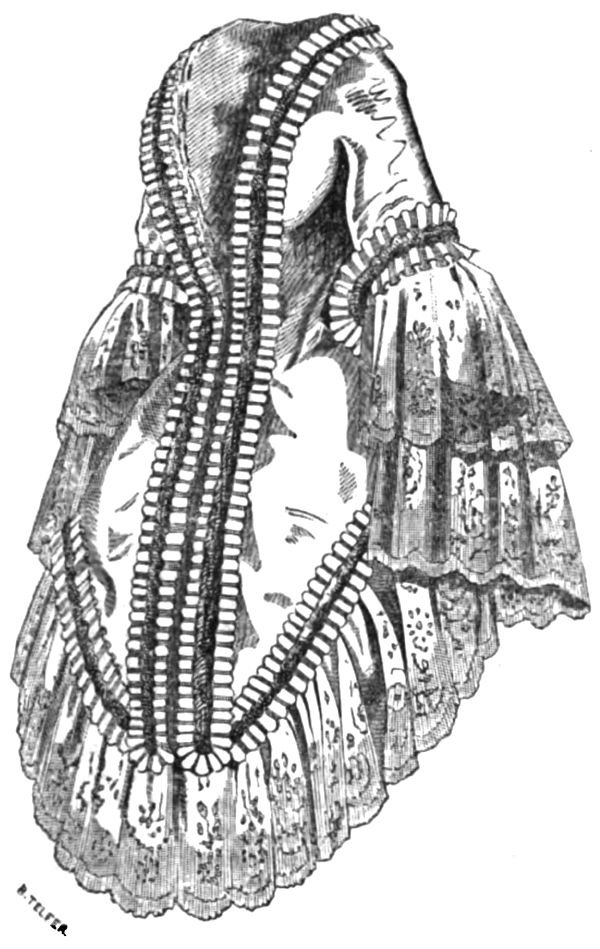

| Designs for Mantelets, engraved by Brightly, Thomas, | ||

| and Talfer. | ||

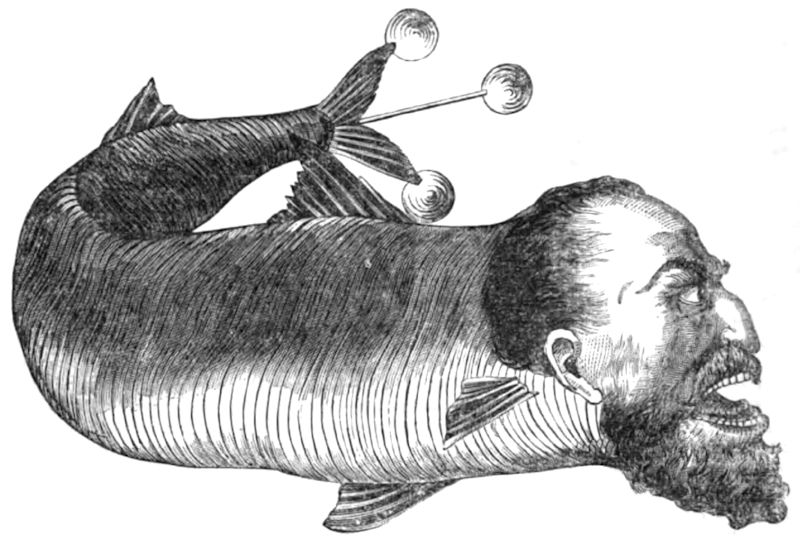

| The Shark, engraved by Brightly. | ||

| The Origin of Music, engraved by Tucker. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| The Sisters, engraved by Thomas B. Welch. | ||

| He Comes Not, engraved by Holl. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Dance of the Mandan Indians, engraved by Rawdon, | ||

| Wright & Hatch. | ||

| Rail Shooting, engraved by Brightly. | ||

| The Slave of the Pacha, engraved by J. Brown. | ||

| The Way to Church, engraved by T. McGoffin. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Portrait of Thomas Johnson, engraved by Brightly. | ||

| Teal Shooting, engraved by Brightly. | ||

| The Highland Chase, engraved by T. B. Welch. | ||

| The Angel’s Whisper, engraved by T. Illman & Son. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| American Quail, engraved by Brightly. | ||

| Catskill Mountain House, engraved by Smillie. | ||

| The Home of Milton, engraved by W. E. Tucker. | ||

| Mariner’s Beacon, engraved by H. Smith. | ||

| Paris Fashions, engraved by David. | ||

| Ruffed Grouse, engraved by Brightly. |

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXVII. PHILADELPHIA, JULY, 1850. No. 1.

It may be universally affirmed that every thing having shape either grows or is put together, is a living organism or a contrived machine; and the radical distinction between minds in all the modes of their operation, and between things in all the forms of their manifestation, is expressed in the antithesis of vitality and mechanism. To suggest, in a manner necessarily imperfect and rambling, some of the important consequences involved in this distinction, is the object of the present essay.

And first, in regard to minds, it may be asked, to what faculties and operations of the intelligence do you apply the term vital, as distinguished from other faculties and operations indicated as mechanical? The answer to this question may be spiritually true without being metaphysically exact, and we shall hazard a brief one. The soul of man in its essential nature is a vital unit and person, capable of growth through an assimilation of external objects; and its faculties and acquirements are all related to its primitive personality, as the leaves, branches, and trunk of a tree to its root. In the tree there are sometimes dead branches and withered leaves, which constitute a part of the tree’s external form without participating in the tree’s internal life. The same thing occurs in the human mind. Faculties, originally springing from the soul’s vital principle, become disconnected from it, lose all the sap and juice of life, and dwindle from vital into mechanical powers. The customary vocabulary of metaphysics evinces the extent of this decay in its division of the mind into parts, each part with a separate name and performing a different office. It is plain that no organism, vegetable, animal, or human, admits of such a classification of parts, for the fundamental principle of organisms is unity in variety, each part implying the whole, growing out of a common centre and source, and dying the moment it is separated. When, therefore, we say that the mind has faculties which are not vitally related to each other, that the whole mind is not present in every act, that there are processes of thought in which a particular faculty operates on its own account, we assert the existence of death in the mind; what is worse, the assertion is true; and, what is still worse, this mental death often passes for wisdom and common sense, and mental life is stigmatized as fanaticism.

Now, this antithesis of life and death, vitality and mechanism, the conception of the spirit of things, and the perception of the forms of things, is a distinction available in every department of human thought and action, and divides minds into two distinct classes, the living and the lifeless. The test of the live mind is, that it communicates life. The only sign here of possession is communication; and life it cannot possess unless life it communicates. Spiritual life implies a combination of force and insight, an indissoluble union of will and intelligence, in which will sees and intelligence acts. A mental operation, in the true meaning of the phrase, is a vital movement of the mind; and although this movement is called a conception or an act according as it refers to meditation or practice, it cannot in either case be a conception without being an act, or an act without being a conception. Conception, in the last analysis, is as truly an act of the mind as volition; both are expressions of one undivided unit and person; and the only limit of conception, the limit which prevented Kepler from conceiving the law of gravitation, and Ben Jonson from conceiving the character of Falstaff, is a limitation of will, of personality, of individual power, of that innate force which is always the condition and the companion of insight. All the vital movements of the mind are acts whether the product be a book or a battle; and that is a singular philosophy of the will which calls Condé’s charge at Rocroi an act, and withholds the name from Shakspeare’s conception of Othello.

As this spiritual force is ever the characteristic of vital thought, such thought is both light and heat, kindles as well as informs, and acts potently on other minds by imparting life as well as knowledge. There are many books which contain more information than Paradise Lost, but Paradise Lost stimulates, dilates and enriches our minds by communicating to them the very substance of thought, while the other books may leave us as poor and weak as they found us, with the addition only of some names and forms of things which we did not know before. The great difference, therefore, between a vital and mechanical mind is this, that from one you obtain the realities of things, and from the other the mere appearances; one influences, the other only informs; one increases our power, the other does little more than increase our words. The action of a live mind upon other minds is chiefly an influence, and the true significance of influence is that it pierces through all the formal frippery of opinion and speculation lying on the surface of consciousness, and touches the tingling and throbbing nerve at its centre and soul; rousing the mind’s dormant activity, breathing into it a new motive and fresh vigor, and making it strong as well as wise. As regards the common affairs of the world, this influence is as the blast of an archangel’s trumpet, waking us from the death of sloth and custom. In the fire of our newly kindled energies the mean and petty interests in which our thoughts are ensnared wither and consume; and, discerning vitalities where before we only perceived semblances, a strangeness comes over the trite, a new meaning gleams through old appearances, and the forms of common objects are transfigured, as viewed in the vivid vision of that rapturous life. Then, and only then, do we realize how awful and how bright is the consciousness of a living soul; then immortality becomes a faith, and death a delusion; then magnanimous resolves in the heart send generous blood mantling in the cheek, and virtue, knowledge, genius, heroism, appear possibilities to the lazy coward who, an hour before, whined about his destiny in the hopeless imbecility of weakness. Although this still and deep ecstasy, this feeling of power and awe, is to most minds only a transient elevation, it is still a revelation of the vital within them, which should at least keep alive a sublime discontent with the sluggish apathy of their common existence. “Show me,” says Burke, “a contented slave and I will show you a degraded man,”—a sentence right from the hot heart of an illustrious man, whose own mind glowed with life and energy to the verge of the tomb, and who never knew the slavery of that sleep of mental death, which withers and dries up the very fountains of life in the soul.

The usual phrases by which criticism discriminates vital from mechanical minds, are impassioned imagination and logical understanding. This vocabulary, though open to objections, as not going to the root of the matter, is still available for our purpose. It draws a definite line between genius and talent. The man of impassioned imagination is vital in every part. The primitive spiritual energy at the centre of his personality permeates, as with warm life-blood, the whole of his being, vivifying, connecting, fusing into unity, all his faculties, so that his thought comes from him as an act, and is endowed with a penetrating and animating as well as enlightening power. The thoughts of Plato, Dante, Bacon, Shakspeare, Newton, Milton, Burke, not to mention others, are actors in the world—communicating life, forming character, revealing truth, generating energy in recipient minds. These men possess understanding as far as that term expresses an operation of the mind, but understanding with them is in living connection with imagination and emotion; they never use it as an exclusive power in themselves, they never address it as an exclusive power in others. To understand a thing in its external qualities and internal spirit, requires the joint operation of all the faculties; and no fact is ever thoroughly understood by the understanding, for it is the person that understands not the faculty, and the person understands only by the exercise of his whole force and insight. The man of understanding, so called, simply perceives the forms of things and their relations; the man of impassioned imagination perceiving forms and divining spirit, conceives the life of things and their relations. The antithesis runs through the whole realm of thought and fact. The man of understanding, when he rises out of sensations, simply reaches abstractions; and in the abstract there is no life. Ideas and principles belong as much to the concrete, to substantial existence, as the facts of sensation; the law of gravitation is a reality no less than the planet Jupiter; but to the man of mechanical understanding, ideas subside into mere opinions, and principles into generalities; and as by the very process of his thinking he disconnects, and deadens by disconnection, the powers by which he thinks, he cannot exercise, conceive or communicate life, cannot invent, discover, create, combine. This is evident from the nature of the mind, and it is proved by history. In art, religion, science, philosophy, politics, the minds that organize are organic minds, not mechanical understandings.

The principle we have indicated, applies to all matters of human concern, the simplest as well as the most complicated. Let us first take a familiar instance from ordinary life. In the common intercourse of society we are all painfully conscious of the dominion of the mechanical, prescribing manner, proscribing nature. In the Siberian atmosphere of most social assemblies the soul congeals. The tendency to isolation of mind from mind, and heart from heart, is most apparent in the contrivances by which society brings its members bodily together—the formal politeness excluding the courtesy it mimics. Hypocrisy, artifice, non-expression of the reality in persons—these are apt to be the characteristics of that dreary solitude which passes under the exquisitely ironical appellation of “good society.” The universal destiny of men and women who engage in this game of fashion as the business of life, is frivolity or ennui. They either fritter to pieces or are bored to death. Nothing so completely wastes away the vitality of the mind, and converts a person into a puppet, as this substitution of the verb “to appear,” for the verb “to be.” Whatever is graceful in manner, carriage and conversation, is natural; but the art of politeness, as commonly practiced, is employed to deaden rather than develop nature, from its ambition to reduce the finer instincts to mechanical forms. In the very term of gentleman there is something exceedingly winning and beautiful, expressing as it does a fine union of intelligence and courtesy; but in genteel society the word too often means nothing more than foppish emptiness, and Sir Philip Sidney gives way to Beau Nash.

Even here, however, the moment a person with a genius for society appears, it is curious to see how quickly the different elements are fused together, by a few flashes of genuine social inspiration. Convention is at once abolished, each heart finds a tongue, giggling turns into merriment, conversation occurs and prattle ceases, and a party is really organized. A little sincerity of this sort in social intercourse would infinitely beautify life.

In one of the most important matters connected with the welfare of men, that of practical ethics, we have another example of the despotism of the mechanical and disregard of the vital, in human life. A true writer on morals should understand two things, morality and immorality; but a mechanical mind can do neither. He neither communicates the life of moral ideas, nor discerns the life of vicious ideas, but simply has opinions on morals, and opinions on vice. The consequence is that most of the “do-me-good” books are lifeless as regards effect—are contemptuously abandoned by men to children, and by children are learned only to be violated. At last it becomes the sign of green juvenility to quote an abstract truism against a concrete vice, and no person in active life considers himself at all bound to accommodate his conduct to axioms. Indeed, common writers on ethics have become unenviably notorious for expending the full force of their feebleness in statements of generalities, which are universally assented to, and almost as universally disregarded. Complacently perched on the chill summits of abstract principles, these gentlemen appear to experience a grim satisfaction in sending down into the warm and living concrete a storm of axiomatic snow and sleet. Having no practical grasp of things, they emphasize duties without possessing any clear insight of practices, and accordingly their indignant blast of truism whistles shrilly over the heads of the sinners it should lay prostrate. Wanting the power to pass into the substance and soul of existing objects and living men, they content themselves with applying external rules to external appearances, glory in the gift of invective as divorced from the secret of interpretation, and being thus shrews rather than seers, they do that worst of injuries to the cause of morality which results from denouncing the devil without understanding his deviltry. In the republic of delusion and democracy of transgression there are certain errors deserving the name of “popular,” errors which mislead three quarters of the human race; and the analysis and exhibition of these should be a leading object of practical morality. Thoroughly to comprehend one of these impish emissaries of Satan, and clearly to demonstrate that the rainbow bubbles he sports in the sun are begotten by froth on emptiness, might not be so grand a thing as to strut about in the worn-out frippery of moral commonplaces, but it would expose one fatal fallacy which assists in misguiding public sentiment, distorting human character, and impelling reasonable men into those expeditions after the unreal, which are every day wrecked on the rocks of nonsense or crime. But to do this requires a vital mind, and in matters of morals society is very well content not to be pricked and probed in conscience by the sharp benevolence of truth. The mechanical moralists disturb no robber or murderer, no cheat or miser, no spendthrift or profligate, no man who wishes to get what he is pleased to call a living by preying on his neighbors. They neither expose nor reform wickedness, but simply toss words at it, for a consideration. Yet from such moral machines it is supposed that, in the course of education, ingenuous youth can get moral life; and real surprise is often expressed by parents, when their children return from academies or colleges, that the only vital knowledge, in form and in essence, that the dear boys have mastered, relates to sin and the devil.

If the mechanical moralists are to be judged by their effects—by their capacity to do the thing they attempt—and thus judged, have terrible sins of omission resting on their work, what shall we say of the mechanical theologians?—There is against each of three liberal professions a time-honored jest, adopted by “gentle dullness,” all over the world, and from its universality almost worthy of a place in Dugald Stewart’s “fundamental principles of human belief.” The point of these venerable facetiæ consists in associating law with chicane, medicine with homicide, and preaching with Dr. Young’s “tired nature’s sweet restorer, balmy sleep.” A joke which seems to be thus endorsed by the human race carries with it some authority, and it would be presumptuous to touch never so gently the subject of theology, without a preliminary remark on this question of dullness. Sin is sarcastic, sin is impassioned, sin is sentimental, sin is fascinating, sin swaggers in rhetoric’s most gorgeous trappings and revels in fancy’s most enticing images, and why should piety alone have the reputation of being feeble and dull? The charge itself, while it closes to the general reader Jeremy Taylor’s wilderness of sweets equally with Dr. Owen’s “continent of mud,” is not without its benumbing effect upon the preacher, for bodies of men commonly understand the art of adapting their conduct to the public impression of their character, and are not apt to provide stimulants when readers only expect soporifics. The truth is that sermons are never dull as sermons, but because the sermonizer is weak in soul. No man with a vision of the interior beauty and power of spiritual truths, no man whom those truths kindle and animate, no man who is truly alive in heart and brain, and speaks of what he has vitally conceived, can ever be dull in the expression of what is the very substance and doctrine of life. The difficulty is that clergymen are apt to fall into mechanical habits of thinking; then ideas gradually fade into opinions; truths dwindle into truisms; a fine dust is subtly insinuated into the vitalities of their being; the holy passion with which their thoughts once gushed out subsides, and “good common sense” succeeds to rapture; and thus many an inspiring teacher, originally a conductor of heaven’s lightning, and exulting in the consciousness of the immortal life beating and burning within him, has lapsed into a theological drudge, dull in his sermons because dull in his conceptions, neither alive himself nor imparting life to others. This decay often occurs in conscientious and religious men, who sufficiently bewail the torpor of soul which compels them to substitute phrases for realities, and to whom this mental death, as they feel it stealing over them, is at once a spell and a torment. The clergyman, who does not keep his mind bright and keen by constant communion with religious ideas, is sure to die of utter weariness of existence. He has once caught a view of the promised land from the Pisgah height of contemplation—wo unto him if it “fades into the light of common day.”

But leaving such perilous topics as ethics and divinity to wiser heads, and passing on to the subjects of philosophy and science, it may be asked—does not the mechanical understanding hold undisputed sway in these? Has impassioned imagination any thing to do with metaphysics, mathematics, natural philosophy, with the observation and the reasoning of the philosopher who deals with facts and laws? The answer to this question is an emphatic yes. That roused, energetic and energizing state of mind which we have designated as impassioned imagination, is as much the characteristic of Newton as of Homer. The facts, direction and object are different, but the faculty is the same. A man of science without a scientific imagination, vital and creative like the poetical imagination, belongs to the second or third class of scientific men, the Hayleys and Haynes Baileys of science. Men of mechanical understandings never discover laws and principles, but simply repeat and apply the discoveries of their betters. Nothing but the fresh and vigorous inspiration which comes from the grasp of ideas, could carry such men as Kepler and Newton through the prodigious mass of drudgery, through which ran the path which led to their objects; for genius alone is really victorious over drudgery, and refuses to submit to the weariness and deferred hope which attend upon vast designs. Indeed, in following the processes of scientific reasoning, whether inductive or deductive, we are always conscious of an element of beauty in the impression left on the mind, an element which we never experience in following the steps of the merely formal logician. Take the discussion, for instance, between Butler and Clarke on the à priori argument for the existence of God, and no reader who attends to the progress of the reasoning can fail to feel the same inner sense touched which is more palpably addressed by the poet. All the great thinkers, indeed, in all the branches of speculative and physical science, are vital thinkers, and their thoughts are never abstract generalities, but always concrete conceptions, endowed with the power to work on other minds, and to generate new thought. Bacon, the greatest name in the philosophy of science, was so jealous of the benumbing and deadening effect of all formal and mechanical arrangement of scientific truth, that he repeatedly opposes all systematization of science, and in his Natural Philosophy followed his own precepts. In the Advancement of Learning he says: “As young men, when they knit and shape perfectly do seldom grow to a further stature, so knowledge, while it is in aphorisms and observations, it is in growth; but when it is once comprehended in exact methods, it may perchance be further polished and illustrated, and accommodated for use and practice; but it increases no more in bulk and substance.” And again he remarks: “The worst and most absurd sort of triflers are those who have pent the whole art in strict methods and narrow systems, which men commonly cry up for their regularity and style.” In illustration of this we may adduce Whewell’s celebrated works, The History and Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences. Here are great learning, logical arrangement, a complete superficial comprehension of the whole subject; but life is wanting. Most of the great discoveries and inventions with which such a book would naturally deal have been made since the publication of Bacon’s Novum Organon; but more mental nutriment and inspiration, more to advance the cause of science, can be found in one page of the Novum Organon than in Whewell’s whole five volumes. Such is the difference between a vital and mechanical mind in the history and philosophy of science; and the difference is more observable still when we come to consider the deep and constant enthusiasm, the persisting, penetrating genius of the practical discoverer, as contrasted with the cold and uncreative memory-monger and reasoning machine, who too often passes himself off as the real savant. The only great man of science who has detailed his processes in connection with his emotions is Kepler, and everybody has heard of the “sacred fury” with which he assaulted the fortresses in which nature long concealed her laws. His page flames with images and exclamations. His operations to conquer the mystery in the motions of the planet Mars are military. His object is as, he says, “to triumph over Mars, and to prepare for him, as one altogether vanquished, tabular prisons and equated eccentric fetters.” When “the enemy left at home a despised captive, had burst all the chains of the equations, and broken forth of the prisons of the tables,” and it was “buzzed here and there that the victory is vain,” the war rages “anew as violently as before,” and he “suddenly brings into the field a new reserve of physical reasonings on the rout and dispersion of the veterans.” A poet can thus vitalize mathematics, and “create a soul under the ribs” of physical death.

In politics and government, the most practical objects of human interest, the men who organize institutions and wisely conduct affairs, are men of vital minds; while the whole brood of ignorant and scampish politicians, whose vulgar tact is but a caricature of insight, and who are as great proficients in ruining nations as statesmen are in advancing them, are men of mechanical minds. In politics, perhaps, more practical injury has resulted from the dominion of formal dunces, than in any other department of human affairs—politics being the great field of action for all speculators in public nonsense, for all men whose incompetency to handle things would be quickly discovered in any other profession. But a great statesman, no less than a great poet, discerns the life of things in virtue of having himself a live mind, and, not content with observing men and events, divines events in their principles, and thus reads the future. When he proposes a scheme of legislation, all its results exist in his mind as possibilities, and if an effect is produced not calculated in the conception, he is so far to be accounted a blunderer, not a statesman. Perhaps of all the statesmen that ever lived, Edmund Burke had this power of reading events in principles in the greatest perfection; and certainly there are few English poets who can be said to equal him in impassioned imagination. This imagination was not, as is commonly asserted, a companion and illustrator of his understanding, appending pretty images to strong arguments, but it included understanding in itself, and was both impetus and insight to his grandly comprehensive and grandly energetic mind. Fox, Pitt, and all the politicians of his time, were, in comparison with him, men of mechanical intellects, constantly misconceiving events; mere experimenters, surprised at results which they should have predicted. There is something mortifying in the reflection that, in free countries, the people have not yet arrived at the truth, that great criminality as well as great impudence are involved in the exercise of political power without political capacity. A politician in high station, without insight and foresight, and thus blind in both eyes, is an impostor of the worst kind, and should be dealt with as such.

In art and literature the doctrine of vital powers lies at the base of all criticism which is not mere gibberish. It is now commonly understood that the creative precedes the critical; that critical laws were originally generalized from poetic works; and that a poem is to be judged by the living law or central idea by which it is organized, which law or idea is as the acorn to the oak, and determines the form of the poem. The power and reach of the poet’s mind is measured by his conception of organic ideas, of ideas which, when once grasped, are principles whence poems necessarily grow, and are eventually realized in works. The universality of Shakspeare is but a power of vital conception, not limited to one or two ideas, but ranging victoriously over the world of ideas. These celestial seeds, once planted in a poetic nature, germinate and grow into forms of individual being, whose loveliness and power shame our actual men and actual society by a revelation of the real and the permanent. Chaucer, Shakspeare, Spenser, Milton, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, in virtue of their power to realize and localize the ideal, give us “poor humans” a kind of spiritual world on earth.

The schoolmasters of letters, those gentlemen who frame laws of taste, and manufacture cultivated men, commonly display a notable oversight instead of insight of the distinction between vital and mechanical minds, between authors who impart power and authors who impart information. They judge the value of a book by its external form instead of internal substance, and altogether overlook the only important office of reading and study, which plainly is the acceleration of our faculties through an increase of mind. Mind is increased by receiving the mental life of a book, and assimilating it with our own nature, not by hoarding up information in the memory. Books thus read enrich and enlarge the mind, stimulating, inflaming, concentrating its activity; and though without this reception of external life a man may be odd, he cannot be original. The greatest genius is he who consumes the most knowledge, and converts it into mind. But a mechanical intellect merely attaches the husks of things to his memory, and eats nothing. It is for this reason that heavy heads, laden with unfertilizing opinions and dead facts which never pass down into the vitalities of their being, are such terrific bores. Considering literature not as food but as luggage, they cram their brains to starve their intelligence—and wo to the youth whom they pretend to instruct and inform! A true teacher should penetrate to whatever is vital in his pupil, and develop that by the light and heat of his own intelligence—like the inspiring master described by Barry Cornwall’s enthusiast:—

He was like the sun, giving me light;

Pouring into the caves of my young brain

Knowledge from his bright fountains.

A man who reads live books keeps himself alive, has a constant sense of what life means and what mind is. In reading Milton, a power is communicated to us, which, for the time, gives us the feeling of a capacity for doing any thing, from writing a Hamlet to whipping Tom Hyer. “My ——, sir,” said the artist who had been devouring Chapman’s Homer, “when I went into the street, after reading that book, men seemed to be ten feet high.” This exaltation of intelligence is simply a movement of our consciousness from the mechanical to the vital state, and to those whose common existence is in commonplaces such an exaltation occasions a shock of surprise akin to fear.

In an art very closely connected with one of the highest forms of literature, the art of acting, we have another illustration of the fundamental antithesis, in processes and in results, between vitality and mechanism. Few, even among noted performers, have minds to conceive the characters they play; and it consequently is a rare thing to see a character really embodied and ensouled on the stage. The usual method is to give it piece by piece, and part by part, and the impression left on the audience is not the idea of a person, but an aggregation of personal peculiarities. Mr. Macready, for instance, has voice, action, understanding, grace of manner, felicity in points: but each is mechanical. His mind is hard and unfusible, never melts and runs into the mould of the individuality he personates, never imparts to the audience the peculiar life and meaning embodied by his author. His energy is not vital but nervous; his mode of arriving at character is rather logical than imaginative. He studies the text of Hamlet, infers with great precision of argument the character from the text, and plays the inference. Booth, on the contrary, who of all living actors has the most force and refinement of imagination, conceives Hamlet as a person, preserves the unity of the person through all the variety in which it is manifested, and seems really to pass out of himself into the character. Macready leaves the impression of variety, but of a variety not drawn out of one fertile and comprehensive individuality: Booth gives the individuality with such power that we can easily conceive of even a greater variety in its expression without danger to its unity. The impression which Macready’s Hamlet leaves on the mind is an impression of Mr. Macready’s brilliant and versatile acting; the impression which Booth stamps on the imagination is the profound melancholy of Hamlet, underlying all his brilliancy and versatility. A man can witness Booth’s personation of Macbeth, Hamlet, Lear and Othello, with great delight, and with great accession of knowledge, after reading the deep Shakspearian criticism of Goethe, Schlegel and Coleridge: but every one feels it would be unjust to bring Macready to the test of such exacting principles.

In these desultory remarks on a variety of suggested topics, we have attempted to illustrate the radical distinction between vitality and mechanism, impassioned imagination and logical understanding, the communication of mental life and the imparting of lifeless information, as that distinction applies to all things which occupy human attention and stimulate human effort. We have indicated, in a gossiping way, the dangerous ease with which the mechanical supersedes the vital in those departments of knowledge and affairs which originated in the mind’s creative and organizing energy; in society, in governments, in laws, literature and institutions, in ethical, mental and physical science; and have tried to show that such an usurpation of torpor over activity dulls and deadens the soul, makes existence a weakness and weariness, and mocks our eyes with nothing but the show and semblance of power. A man of mechanical understanding can but exist his four-score years and ten, and a dreary time he has of it at that, bored and boring all his few and tiresome years; but a live mind has the power of wonderfully condensing time, and lives a hundred common years in one. From the phenomena presented by men of genius we can affirm the soul’s immortality, because they give some evidence of the joy, the ecstasy, involved in the idea of life; but to a mechanical being, endowed with a spark of vitality sufficient only to sting him with rebuking possibilities, an endless existence would be but an endless ennui. The ground for hope is, that man, using as he may all the resource of stupid cunning, cannot kill the germ of life which lies buried in him; hatred and pride, the sins of the heart, may eat into it, and his “pernicious soul” seem, like Iago’s, to “rot half a grain a day;” mechanism, the sin of the head, may withdraw itself into “good common sense,” and contentedly despise the joyous power of vital action; but still the immortal principle constituting the Person survives—patient, watchful, persistent, unconquerable, refusing to capitulate, refusing to die.

P.

———

BY ALFRED B. STREET.

———

I.—CELINE.

Those deep, delicious, heavy-lidded eyes

Oh, I could bask forever in their light!

What raptures, sweet, heart-thrilling raptures, rise

Whene’er I pierce their depths with eager sight!

The profile pure and soft—the bright full face—

The cupid mouth with rows of flashing pearls—

The waist so dainty—step of gliding grace—

White brow—curved hair, more beautiful than curls,

All make her sweetest, loveliest of girls.

Her breath is balmier than May’s downiest breeze;

Rosier than rose-buds are her moist, plump lips;

Than the pure nectar there, no purer sips

The clinging bee—all beauty’s harmonies

Are in her sweetly blent—all hearts her graces seize.

II.—THE LESSONS OF NATURE.

Nature in outward seeming takes the hue

Of our chance mood; if sad, her tones and looks

Are full of grief; if glad, her winds and brooks

Are full of merriment. But piercing through

Her outward garb, her sadness whispers “Peace—

Peace to thee, mourner! day succeeds to night,

Sunshine to storm!” Her brightest mirth says “Cease

This thoughtless rapture! flowers must suffer blight,

Change is my law of order.” Then a voice

Swells from her deep and solemn heart, “Rejoice

With purer joy, ye mirthful! and be glad

With a sustaining, steadfast faith, ye sad!

In this swift, changeful life, whate’er befall

(Blest truth) a watchful God of love is over all!”

———

BY JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL.

———

When Persia’s sceptre trembled in a hand

Wilted by harem-heats, and all the land

Was hovered over by those vulture ills

That snuff decaying empire from afar,

Then, with a nature balanced as a star,

Dara arose, a shepherd of the hills.

He, who had governed fleecy subjects well,

Made his own village, by the self-same spell,

Secure and peaceful as a guarded fold,

Till, gathering strength by slow and wise degrees,

Under his sway, to neighbor villages

Order returned, and faith and justice old.

Now when it fortuned that a king more wise

Endued the realm with brain and hands and eyes,

He sought on every side men brave and just,

And, having heard the mountain-shepherd’s praise,

How he renewed the mould of elder days,

To Dara gave a satrapy in trust.

So Dara shepherded a province wide,

Nor in his viceroy’s sceptre took more pride

Than in his crook before; but Envy finds

More soil in cities than on mountains bare,

And the frank sun of spirits clear and rare

Breeds poisonous fogs in low and marish minds.

Soon it was whispered at the royal ear

That, though wise Dara’s province, year by year,

Like a great spunge, drew wealth and plenty up,

Yet, when he squeezed it at the king’s behest,

Some golden drops, more rich than all the rest,

Went to the filling of his private cup.

For proof, they said that wheresoe’er he went

A chest, beneath whose weight the camel bent,

Went guarded, and no other eye had seen

What was therein, save only Dara’s own,

Yet, when ’twas opened, all his tent was known

To glow and lighten with heapt jewels’ sheen.

The king set forth for Dara’s province straight,

Where, as was fit, outside his city’s gate

The viceroy met him with a stately train;

And there, with archers circled, close at hand,

A camel with the chest was seen to stand;

The king grew red, for thus the guilt was plain.

“Open me now,” he cried, “you treasure-chest!”

’Twas done, and only a worn shepherd’s vest

Was found within; some blushed and hung the head,

Not Dara; open as the sky’s blue roof

He stood, and “O, my lord, behold the proof

That I was worthy of my trust!” he said.

“For ruling men, lo! all the charm I had;

My soul, in those coarse vestments ever clad,

Still to the unstained past kept true and leal,

Still on these plains could breathe her mountain air,

And Fortune’s heaviest gifts serenely bear,

Which bend men from the truth, and make them reel.

“To govern wisely I had shown small skill

Were I not lord of simple Dara still;

That sceptre kept, I cannot lose my way!”

Strange dew in royal eyes grew round and bright,

And thrilled the trembling lids; before ’twas night

Two added provinces blessed Dara’s sway.

———

BY JAMES T. FIELDS.

———

In a green sheltered nook, where a mountain

Stood guarding the peace-haunted ground,

Lived a maiden whose smile was the sunlight

That gladdened the hill-sides around.

Her voice seemed a musical echo,

Whose notes wandered down from above,

And wherever she walked in her beauty

Sprang blossoms of joy and of love.

As she stood at her door in the morning,

The hunter below, riding by,

Cried out to his comrades, “we’re early!

For look, there’s a star in the sky!”

At the chapel, when good men were praying

That angels of God would appear,

Every heart turned to her, lowly kneeling,

And felt that an angel was near.

Thus radiant and pure in her presence,

A blessing she moved, day by day,

Till a proud lord beheld her, and loved her,

And lured her forever away.

He bore this bright bird of the mountain,

Watched over and shielded the best,

From the home of her youth and her kindred,

Away to his own haughty nest.

And lo! the grim idols in waiting

Beset her for worship, and won;

And the light of her beautiful childhood

Went down like the swift-fading sun.

And sudden as rises the black cloud,

When tempests the thunder-gods start,

Strange wishes encircled her bosom,

And Pride swept the halls of her heart.

And once, when o’ermastered by anger,

Her golden-haired boy sought her side,

In her fury she smote down her first born,

And he fell like a lily and died.

There were tears, burning tears, to recall him,

And anguish that scorches the brain,

But the harp-strings of life never answered

The touch that would tune them again!

She sleeps in a dark mausoleum,

And ages have rolled o’er her head,

But her name is remembered in Tyrol

As when she was laid with the dead.

And to-day, as the traveler sits weary,

And drinks from the rude fountain-bowl,

They tell the sad story, and whisper

The warning that speaks to your soul.

OR THE CAPTAIN’S SON AND THE SAILOR BOY.

A SEA STORY.

———

BY S. A. GODMAN.

———

Fortune, the great commandress of the world,

Hath divers ways to enrich her followers:

To some, she honor gives without deserving;

To other some, deserving without honor;

Some wit—some wealth—and some wit without wealth;

Some, wealth without wit—some, nor wit nor wealth.

Chapman.

“Rouse up, rouse up, my hearty! Bear a hand and be lively for that little devil-skin abaft, has been hailing for you this five minutes.”

Thus spoke, with a rough voice, but in a kind tone, a tall and powerfully built sailor, as he descended the forecastle-ladder, to a boy of some ten years of age, who, lying stretched upon his back on a mess-chest, was fast asleep. Loud as were the tones of the speaker, they made no impression upon the boy. Wrapped in the deep, sweet slumber of childhood, his body fatigued, his conscience clear, and his mind at ease, he was enjoying one of those refreshing rests that are only permitted to the young and contented—the sleep that manhood longs after but seldom experiences.

A beautiful picture would that forecastle and its inmates have made, could they have been transferred to canvas. The boy, a noble one, as he reposed with closed eye-lids and upturned face, over which bright smiles were flitting—the reflection of pleasant, hopeful dreams—seemed an embodiment of intelligence and innocence; notwithstanding the coarse canvas trowsers and striped cotton-shirt which formed his only attire. The man, with his muscular and strongly-knit figure, his bronzed cheeks, huge whiskers, brightly gleaming eyes and determined expression of countenance, was the personification of bodily strength, physical perfection and perfect self-reliance. The one looked as if he were a spirit from a higher sphere, who had by chance become an inmate of that dark, confined, triangular-shaped and murky apartment; and appeared all out of place amidst its mess-chests, bedding, and other nautical dunnage, and its atmosphere reeking with the odors of bilge-water, tar, and lamp-smoke. The other was in keeping with the surrounding objects; his bright red flannel shirt, his horny hands, his very attitude showed him one to ease and comfort unaccustomed, whose only home was a forecastle, his abiding-place the heaving ocean.

Wearied with awaiting the result of his verbal summons, the seaman reached down to awaken his companion with a shake; and as he did, a beam of affection so softened the expression of his countenance, and lent so much tenderness to his eye, that with all his roughness and uncouthness, the weather-beaten tar became really handsome; for, than love, there is no more certain beautifier. Though undisturbed by noise, no sooner was the sailor-boy touched, than, true to the instinct of his calling, he sprung from his resting-place, as wide awake, and with his faculties as much about him, as if he had always been to sleep a stranger—and exclaimed,

“Is it eight bells already, Frank? I thought I had just closed my peepers.”

“Just closed your peepers, my little lark! I began to think your eye-lids were battened down, it seemed such a hard pull for you to heave them up. You haven’t had much of a snooze though, for it’s only four bells; but that young scaramouch astern wants you to take him in tow. So you had better up-anchor and make sail, Tom, for the cabin, or the she-commodore will be sending the boatswain after you with the colt.”[1]

Scarcely waiting to hear the completion of the sentence, the lad hurried up the ladder to the deck, and in a few seconds was at the door of the cabin. Standing just inside the entrance, a drizzling rain preventing him from coming further, stood the youth to whom Frank had referred, by the not very flattering appellations of devil-skin and scaramouch. There was but little difference in the age of the two boys. Not the slightest resemblance or similarity, however, existed between them in any other respect.

The sailor-boy was large for his years—with a figure that gave promise of symmetry, grace, and an early maturity; his head was in keeping with his body—admirably developed, well balanced, and covered with a profusion of rich, dark brown hair; his forehead, broad and intellectual, lent additional beauty to his full, deep-blue eyes; and with his ruddy cheeks, giving evidence of vigorous health, he was just such a boy as a prince might desire his only son and heir to be.

The captain’s son was slight and rather under-sized, with a sickly look, produced apparently more by improper indulgences than natural infirmity; sparkling black eyes, black hair, and regular features, added to a well-shaped head and fine brow, would have rendered him good-looking in spite of his sallow complexion, had it not been for a peevish, discontented and rather malignant expression, that was habitual to him.

The physique of the lads did not differ more than their dress. The one was clothed in a suit of the most costly broadcloth, elegantly made, with boots upon his feet, and a gold chain around his neck to support the gold watch in his pocket. The other, bare-footed, bare-necked, jacketless, was under no obligations to the tailor for adding to the gentility of his appearance. Yet any person, even a blind man, could he have heard their voices, would at once have acknowledged that the roughest clad bore indellibly impressed upon him the insignia of nature’s nobility.

No sooner did the captain’s son see the boy of the forecastle, than he addressed him in a tone and style that harmonized with the sneering expression of his face:

“So, you good-for-nothing, lazy fellow, you’ve made me stand here bawling for you this half hour. What’s the reason you did not come when I first called?”

“Why, Master Charles, I would not have kept you waiting if I had known you wanted me; but I was asleep in the forecastle, sir. Frank Adams woke me up—and I’ve come as quick as I could.”

“Asleep this time in the afternoon! Why don’t you sleep at night? I never sleep in the afternoons. But you had better not make me stand and wait so long for you another time, or I’ll tell my mamma, and she’ll get father to whip you.”

At this threat a bright flush overspread the face and neck of the sailor-boy, and for an instant his eye assumed a fierce expression that was unusual to it; but suppressing his feelings, he replied in his accustomed tone,

“I was up all night, Master Charles, helping to reef top-sails, and lending a hand to get up the new fore-sail in place of the old one that was blown out of the bolt-ropes in the mid-watch. This morning I could not sleep, for you know I was playing with you until mess-time.”

“Well, Tom, come into the cabin and let’s play, and I wont say any thing about it this time,” said Charles, as he walked in, followed by his companion.

What a difference there was between the apartment in which the lads now were, and the one which Tom had left but a few moments before. It was the difference between wealth and poverty.

The vessel, on board of which our scene is laid, was a new and magnificently-finished barque of seven hundred and fifty tons, named the Josephine. The craft had been built to order, and was owned and commanded by Lewis Barney Andrews—a gentleman of education and extensive fortune, who had been for many years an officer in the United States navy. Getting married, however, and his wife’s objecting to the long cruises he was obliged to take in the service, whilst she was compelled to remain at home, he effected a compromise between his better half’s desire that he should relinquish his profession, and his own disinclination to give up going to sea entirely, by resigning his commission in the navy, and purchasing a ship for himself. The Josephine belonged to Baltimore—of which city Captain A. was a native, and was bound to the East Indies. She was freighted with a valuable cargo, which also belonged to the captain, and had on board besides the captain, his wife, son and servant-girl, a crew consisting of two mates, and a boatswain, fourteen seamen, a cook, steward, and one boy.

Her cabin—a poop one—was fitted up in the most luxurious style. Every thing that the skill of the upholsterer and the art of the painter, aided by the taste and experience of the captain, could do to make it elegant, beautiful and comfortable, had been done. Extending nearly to the main-mast the distance from the cabin-door to the transom was full fifty feet. This space was divided into two apartments of unequal size, one of twenty, the other thirty feet, by a sliding bulkhead of highly polished rosewood and superbly-stained glass.

The after-cabin was fitted up as a sleeping-room, with two mahogany bedsteads and all the appurtenances found in the chambers of the wealthy on shore. The forward-cabin was used as a sitting and eating-room. On the floor was a carpet, of whose fabric the looms of Persia might be proud—so rich, so thick, so magnificent was it, and deep-cushioned ottomans, lounges and rocking-chairs were scattered along the sides and were placed in the corners of the apartment.

Not far from the door, reclining on a lounge, with a book in her hand, was the wife of the captain, and the mother of Master Charles. She was a handsome woman, but one who had ever permitted her fancies and her feelings to be the guides of her actions. Consequently her heart, which by nature was a kind one, was often severely wrung by the pangs of remorse, caused by the recollection of deeds committed from impulse, which her pride would not permit her to apologize or atone for, even after she was convinced of her error.

As the two boys entered the cabin she looked at them, but without making any remark, continued the perusal of her book, whilst they proceeded to the after-cabin, and getting behind the bulkhead were out of her sight. For some fifteen minutes the stillness of the cabin was undisturbed; but then, the mother’s attention was attracted by the loud, angry tones of her son’s voice, abusing apparently his play-fellow. Hardly had she commenced listening, to ascertain what was the matter, ere the sound of a blow, followed by a shriek, and the fall of something heavy upon the floor, reached her ear. Alarmed, she rushed into the after-cabin, and there, upon the floor, his face covered with blood, she saw the idol of her heart, the one absorbing object of her affection, her only son, and standing over him, with flashing eyes, swelling chest, and clenched fists, the sailor-boy.

So strong was the struggle between the emotions of love and revenge—a desire to assist her child, a disposition to punish his antagonist—that the mother for a moment stood as if paralyzed. Love, however, assumed the mastery; and raising her son and pressing him to her bosom, she asked in most tender tones, “Where he was hurt?”

“I ain’t hurt, only my nose is bleeding because Tom knocked me down, just for nothing at all,” blubbered out Charles.

The mother’s anxiety for her son relieved, the tiger in her disposition resumed the sway; letting go of Charles, she caught hold of Tom, and shaking him violently, demanded, in shrill, fierce tones, how he, the outcast, dared to strike her child!

Unabashed and unterrified, the sailor-boy looked in the angry woman’s face without replying.

“Why don’t you answer me, you cub! you wretch! you little pirate!—speak! speak! or I’ll shake you to death!” continued the lady, incensed more than ever by the boy’s silence.

“I struck him because he called my mother a hussy, if you will make me tell you,” replied Tom, in a quiet voice, though his eye was bright with anger and insulted pride.

“Your mother a hussy! Well, what else was she? But you shall be taught how to strike your master for speaking the truth to you, you good for nothing vagabond. Run and call your father,” she continued, turning to Charles, “and I’ll have this impertinent little rascal whipped until he can’t stand.”

In a moment Captain Andrews entered; and being as much incensed as his wife, that a sailor-boy, a thing he had always looked upon as little better than a block or rope’s end, had had the audacity to strike his son, he was furious. Taking hold of Tom with a rough grasp, he pushed him out on deck, and called for the boatswain. That functionary, however, was slow in making his appearance; and again, in louder and more angry tones, the captain called for him. Still he came not; and, spite of his passion, the captain could but gather from the lowering expressions of the sailors’ countenances, that he was at the commencement of an emeute.

|

Colt.—A rope with a knot on the end. Used as an instrument of punishment in place of the cat-o’-nine-tails. |

——

The deepest ice that ever froze

Can only o’er the surface close;

The living stream lies quick below,

And flows, and cannot cease to flow.

Byron.

Accustomed to have his commands always promptly obeyed, the wrath of Captain Andrews waxed high and furious at the dilatoriness of the boatswain. Without any other exciting cause, this apparent insubordination on the part of one of his officers, was enough to arouse all the evil passions of his heart. Educated under the strict discipline of the United States service, he had been taught that the first and most important duty of a seaman was obedience. “Obey orders, if you break owners,” was the doctrine he inculcated; and to be thus, as it were, bearded on his own quarter-deck, by one of his own men, was something entirely new, and most insulting to his pride. Three times had he called for the boatswain without receiving any reply, or causing that functionary to appear.

When the captain first came out of the cabin, his only thought was to punish the sailor-boy for striking his son; but his anger now took another course, and his desire to visit the boatswain’s contumacy with a heavy penalty was so great, that he forgot entirely the object for which he had first wished him. Relinquishing his hold on Tom’s shoulder, the captain hailed his first officer in a quick, stern voice,

“Mr. Hart, bring aft Mr. Wilson, the boatswain.”

“Ay, ay, sir,” responded the mate, as he started toward the forecastle-scuttle to hunt up the delinquent. “Hillo, below there!” he hailed, when he reached the scuttle, “You’re wanted on deck, Mr. Wilson!”

“Who wants me?” was the reply that resounded, seemingly, from one of the bunks close up the ship’s eyes.

“Captain Andrews is waiting for you on the quarter-deck; and if you are not fond of tornadoes, you had better be in a hurry,” answered the mate.

Notwithstanding the chief dickey’s hint, the boatswain seemed to entertain no apprehensions about the reception he would meet at the hands of the enraged skipper; for several minutes elapsed before he made himself visible on deck.

As soon as the captain saw the boatswain, his anger increased, and he became deadly pale from excess of passion. Waiting until Wilson came within a few feet of him, he addressed him in that low, husky voice, that more than any other proves the depth of a person’s feeling, with,

“Why have you so long delayed obeying my summons, Mr. Wilson?”

“I was asleep in the forecastle, sir, and came as soon as I heard Mr. Hart call,” replied Wilson.

But the tone in which he spoke, the look of his eye, the expression of his countenance, would at once have convinced a less observant person than Captain Andrews, that the excuse offered was one vamped up for the occasion, and not the real cause of the man’s delay.

“Asleep, sir! Attend now to the duty I wish you to perform—and be awake, sir, about it! And you may, perhaps, get off easier for your own dereliction afterward—for your conduct shall not remain unpunished,” answered the captain.

“Captain Andrews, boy and man, I have been going to sea now these twenty-five years, and no one ever charged Bob Wilson with not knowing or not doing his duty before, sir!” rejoined the boatswain, evidently laboring under as much mental excitement as the captain.

“None of your impertinence, sir! Not a word more, or I will learn you a lesson of duty you ought to have been taught when a boy. Where’s your cat,[2] sir?” continued the captain.

“In the razor-bag,”[3] replied the boatswain.

“Curse you!” ejaculated the captain, almost beside himself at this reply, yet striving to maintain his self-possession; “one more insolent word, and I will have you triced up. Strip that boy and make a spread-eagle of him; then get your cat and give him forty.”

During this conversation between the captain and the boatswain, the crew had been quietly gathering on the lee-side of the quarter-deck, until at this juncture every seaman in the ship, except the man at the wheel, was within twenty feet of the excited speakers. Not a word had been spoken amongst them; but it was evident from the determination imprinted upon their countenances, from their attitudes, and from the extraordinary interest they took in the scene then transpiring, that there was something more in the boatswain’s insubordination than appeared on the surface; and whatever it was, the crew were all under the influence of the same motive.

Mr. Wilson, the boatswain of the Josephine, was a first-rate and thorough-bred seaman. No part of his duty was unfamiliar to him; and never did he shrink from performing any portion of it on account of danger or fatigue. Like many other simple-minded, honest-hearted sons of Neptune, he troubled himself but little about abstruse questions on morals; but he abhorred a liar, despised a thief, and perfectly detested a tyrant. And though he could bear a goodly quantity of tyrannical treatment himself, without heeding it, it made his blood boil, and his hand clench, to see a helpless object maltreated.

Ever since the Josephine had left port, there had been growing amongst the crew a disposition to prevent their favorite, Tom, the sailor-boy, from being imposed upon and punished, as he had been, for no other reason than the willfulness of the captain’s son, and the caprice of the captain’s wife. Not a man on board liked the spoiled child of the cabin. No fancy, either, had they for his mother; because, right or wrong, she always took her son’s part, and oftentimes brought the sailors into trouble. The last time Tom had been punished a grand consultation had been held in the forecastle, at which the boatswain presided; and he, with the rest of the crew, had solemnly pledged themselves not to let their little messmate be whipped again unless, in their opinion, he deserved it.

This was the reason why the boatswain, one of the best men in the ship, had skulked when he heard the captain’s call: he had seen him come out of the cabin with Tom, and rightly anticipated the duty he was expected to perform. Such great control does the habit of obedience exercise over seamen, that although he was resolved to die before he would suffer Tom to be whipped for nothing, much less inflict the punishment himself, the boatswain felt a great disinclination to have an open rupture with his commanding officer. The peremptory order last issued by the captain, however, brought affairs to a crisis there was no avoiding; he either had to fly in the face of quarter-deck authority, or break his pledge to his messmates and his conscience. This, Wilson could not think of doing; and looking his captain straight in the face, in a quiet tone, and with a civil manner, he thus addressed his superior:

“It does not become me, Captain Andrews, so be as how, for to go, for to teach my betters—and—and—” here the worthy boatswain broke down, in what he designed should be a speech, intended to convince the captain of his error; but feeling unable to continue, he ended abruptly, changing his voice and manner, with “Blast my eyes! if you want the boy whipped, you can do it yourself.”

Hardly had the words escaped the speaker’s lips, before the captain, snatching up an iron belaying-pin, rushed at the boatswain, intending to knock him down; but Wilson nimbly leaped aside, and the captain’s foot catching in a rope, he came down sprawling on the deck. Instantly regaining his feet, he rushed toward the cabin, wild with rage, for the purpose of obtaining his pistols. Several minutes elapsed before he returned on deck; when he did he was much more calm, although in each hand he held a cocked pistol.

The quarter deck he found bare; the crew, with little Tom in their midst, having retired to the forecastle, where they were engaged in earnest conversation. The second mate was at the wheel, the seaman who had been at the helm having joined his comrades, so that the only disposable force at the captain’s command was the chief mate, the steward and himself, the cook being fastened up in his galley by the seamen. On the forecastle were fifteen men. The odds were great; but Captain Andrews did not pause to calculate chances—his only thought was to punish the mutinous conduct of his crew, never thinking of the possibility of failure.

Giving one of his pistols to Mr. Hart, and telling the steward to take a capstan bar, the captain and his two assistants boldly advanced to compel fifteen sailors to return to their duty.

|

An instrument used for punishment. |

|

The technical name of the bag in which the cats are kept. |

——

They were met, as the rock meets the wave,

And dashes its fury to air;

They were met, as the foe should be met by the brave,

With hearts for the conflict, but not for despair.

Whilst the captain, mate and steward, were making their brief preparation for a most hazardous undertaking, the men of the Josephine, with that promptness and resolution so common amongst seamen when they think at all, had determined upon the course they would adopt in the impending struggle.

Although the numerical discrepancy between the two parties seemed so great, the actual difference in their relative strength was not so considerable as it appeared. The sailors, it is true, had the physical force—they were five to one; but the captain’s small band felt more confidence from the moral influence that they knew was on their side, than if their numbers had been trebled, without it.

Habit ever exercises a controlling influence, unless overcome by some powerful exciting principle, and men never fly in the face of authority to which they have always been accustomed to yield implicit obedience, but from one of two causes—either a hasty impulse, conceived in a moment, and abandoned by actors frightened at their own audacity; or, a sense of wrong and injustice so keen and poignant, as to make death preferable to further submission.

Aware of custom’s nearly invincible power, having often seen seamen rebel, and then at the first warning gladly skulk back to their duty, the captain unhesitatingly advanced up the weather-gangway to the break of the forecastle, and confronted his mutinous crew. The men, who were huddled around the end of the windlass, some sitting, others standing, talking together in low tones, only showed they were aware of the captain’s presence by suddenly ceasing their conversation—but not a man of them moved.

Captain Andrews, though quick tempered, was a man of judgment and experience; and he saw by the calmness and quietness of his men, that their insubordination was the result of premeditation—a thing he had not before thought—and he became aware of the difficulties of his position. He could not, for his life, think of yielding; to give up to a sailor would, in his estimation, be the deepest degradation. And moral influence was all he could rely upon with which to compel obedience—feeling that if an actual strife commenced, it could but result in his discomfiture. His tone, therefore, was low and determined, as with cocked pistol in hand he addressed his crew:

“Men, do you know that you are, every one of you, guilty of mutiny? Do you know that the punishment for mutiny on the high seas is death? Do you know this? Have you thought of it?” Here the captain paused for an instant, as if waiting for a reply; and a voice from the group around the windlass answered—

“We have!”

Rather surprised at the boldness of the reply, but still retaining his presence of mind, the captain continued:

“What is it then that has induced you to brave this penalty? Have you been maltreated? Do you not have plenty of provisions? Your regular watches below? Step out, one of you, and state your grievances. You know I am not a tyrant, and I wish from you nothing more than you promised in the shipping articles!”

At this call, the eyes of the men were all turned toward Wilson, the boatswain, who, seeing it was expected from him, stepped out to act as spokesman. Respectfully touching his tarpaulin, he waited for the captain to question him. Observing this, the captain said,

“Well, Wilson, your messmates have put you forth as their speaker; and it strikes me that you are the ringleader of this misguided movement. I am certain you have sense enough to understand the risk you are running, and desire you to inform me what great wrong it is that you complain of. For assuredly you must feel grievously imposed upon, to make you all so far forget what is due to yourselves as seamen, to me as your captain, and to the laws of your country!”

“I ain’t much of a yarn-spinner, Captain Andrews, and I can turn in the plies of a splice smoother and more ship-shape than the ends of a speech; and it may be as how I’ll ruffle your temper more nor it is now, by what I have to say—” commenced the boatswain.

“Never mind my temper, sir,” interrupted the captain, “proceed!”

“We all get plenty of grub, Captain Andrews, and that of the best,” continued Wilson; his equanimity not in the least disturbed by the skipper’s interruption. “We have our regular watches, and don’t complain of our work, for we shipped as seamen, and can all do seamen’s duty. But sailors have feelings, Captain Andrews, though they are not often treated as if they had; and it hurts us worse to see those worked double-tides who can’t take their own part, than if we were mistreated ourselves; and to come to the short of it, all this row’s about little Tom, there, and nothing else.”

“Is he not treated just as well as the rest of you? Has he not the same quarters, and the same rations, that the men are content with? Who works him double-tides?” answered the captain, his anger evidently increasing at the mention of Tom’s name; and the effort to restrain himself, being almost too great for the choleric officer to compass.

“You can’t beat to wind’ard against a head-sea, Captain Andrews, without a ship’s pitching, no more than you can reef a to’s-sail without going aloft.” Wilson went on without change in manner, though his voice became more concise and firm in its tone. “And I can’t tell you, like some of them shore chaps, what you don’t want to hear, without heaving you aback. We ain’t got any thing agin you, if you was let alone; all we wants is for you to give your own orders, and to keep Mrs. Andrews from bedeviling Tom. The boy’s as good a boy as ever furled a royal, and never skulks below when he’s wanted on deck; but he stands his regular watches, and then, when he ought to sleep, he’s everlastingly kept in the cabin, and whipped and knocked about for the amusement of young master, and that’s just the whole of it. We’ve stood it long enough, and wont return to duty until you promise—”

“Silence, sir!” roared the captain, perfectly furious, and unable longer to remain quiet. “Not another word! I’ve listened to insolence too long by half, already! Now, sir, I have a word to say to you, and mind you heed it. Walk aft to the quarter-deck!”

The boatswain, though he heard the order plainly, and understood it clearly, paid no attention to it.

“Do you hear me, sir?” asked the captain. “I give you whilst I count ten, to start. I do not wish to shoot you, Wilson; but if you do not move before I count ten, I’ll drive this ball through you—as I hope to reach port, I will!”

Raising his pistol until it covered the boatswain’s breast, the captain commenced counting in a clear and audible tone. Intense excitement was depicted on the faces of the men; and some anxiety was shown by the quick glances cast by the chief mate and steward, first at the captain, and then at the crew. Wilson, with his eyes fixed in the captain’s face, and his arms loosely folded across his breast, stood perfectly quiet, as if he were an indifferent spectator.

“Eight! Nine!” said the captain, “there is but one left, Wilson; with it I fire if you do not start.”

The boatswain remained motionless. “Te—” escaped the commander’s lips; and as it did, the sharp edge of Wilson’s heavy tarpaulin hat struck him a severe blow in the face. This was so entirely unexpected, that the captain involuntarily threw back his head, and by the same motion, without intending it, threw up his arm and clenched his hand enough to fire off the pistol held in it; the ball from which went through the flying-jib, full twenty feet above Wilson’s head.

The charm that had held the men in check, was broken by the first movement toward action, and they made a rush toward the captain and his two supporters. Bravely, though, they stood their ground; and Frank Adams, the sailor introduced with Tom in the forecastle, received the ball from the mate’s pistol in the fleshy part of his shoulder, as he was about to strike that worthy with a handspike. Gallantly assisted by the steward, the captain and mate made as much resistance as three men could against fifteen. The odds were, however, too great; spite of their bravery, the three were soon overpowered and the contest was nearly ended, when a temporary change was made in favor of the weaker party by the appearance in the fray of the second mate. He, during the whole colloquy, had been at the wheel, forgotten by both parties. His sudden arrival, therefore, as with lusty blows he laid about him, astonished the seamen, who gave back for an instant, and allowed their opponents to regain their feet. They did not allow them much time, however, to profit by this respite, for in a few seconds, understanding the source from whence assistance had come, they renewed the attack with increased vigor, and soon again obtained the mastery. But it was no easy matter to confine the three officers and the steward, who resisted with their every power, particularly as the men were anxious to do them no more bodily injury than they were compelled to, in effecting their purpose.

So absorbed were all hands in the strife in which they were engaged, that not one of them noticed the fact that what had been the weather-side of the barque at the commencement of the affray, was now the lee; nor did any of the men—all seamen as they were—observe that the vessel was heeling over tremendously, her lee-scuppers nearly level with the water. A report, loud as a cannon, high in the air, first startled the combatants; then, with a rushing sound, three large, heavy bodies, fell from aloft, one of which striking the deck near the combatants, threatened all with instant destruction, whilst the other two fell with a loud splash into the sea to leeward.