* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: A Bird’s-Eye View of Picturesque India

Date of first publication: 1898

Author: Sir Richard Temple

Date first posted: September 1, 2015

Date last updated: September 1, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20150901

This ebook was produced by: David Jones, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

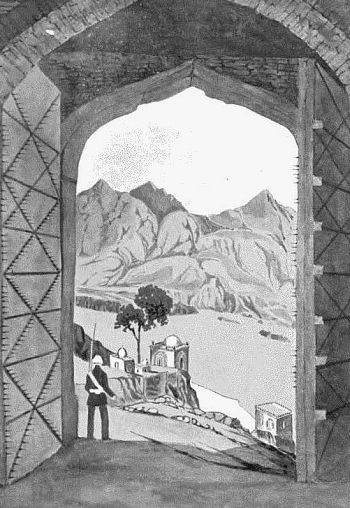

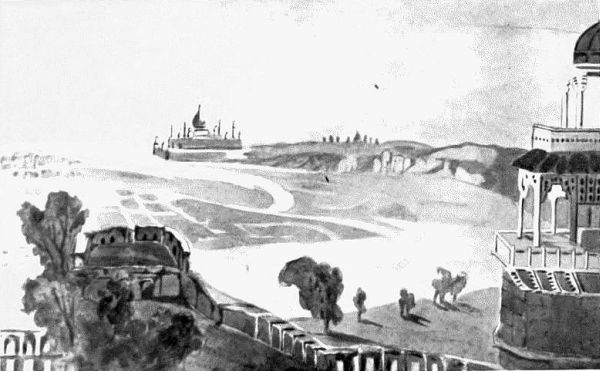

RIVER INDUS AT ATTOK

A BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF

PICTURESQUE INDIA

BY

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

Sir RICHARD TEMPLE, Bart., G.C.S.I.,

D.C.L. (Oxon.), LL.D. (Cantab.), F.R.S.

SOMETIME FINANCE MINISTER OF INDIA,

LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR OF BENGAL, GOVERNOR OF BOMBAY

WITH THIRTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1898

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

The greater part of this work was originally written in the shape of articles for the Syndicate of Northern Newspapers at Kendal. These articles accordingly appeared in many newspapers during the early months of this year 1898, under the general title of “Picturesque India.” It has now been determined to republish them together in a book, with some important additions and improvements, each article making a Chapter of the work in its new form. The scheme was, and still is, to present “a Bird’s-eye View of Picturesque India,” which is the title adopted for the book. Such a purview naturally embraced the principal features in the India of to-day, the land, the people, and the government. But, to render this more complete than it would otherwise have been, three new Chapters have been added—namely, “III. A Summer’s Sojourn in the Himalaya”; “XI. Historic Remains and Ruins”; “XII. Episodes in History and their Localities.” Thus the work at first consisted of nine Chapters; it now consists of twelve; and to these nine Chapters some improvements have been added. Further, a new feature has been introduced, the introduction of which was not possible in the original work—namely, that of illustration in black and white. For such illustration I happen to possess abundant materials, having been all my life a diligent sketcher in water-colour, and of later years in oil also. From my portfolios, containing literally hundreds of pictures, there have been selected thirty subjects specially suited to illustrate the text of the several Chapters. These pictures have been reproduced by a photographic process, so that they exactly represent at least the outlines and the shades of the pictures.

Although the necessary limitations of such a book as this, on so enormous a subject as India, must be evident, still, it may be well to remind the general reader of what is, and what is not, to be expected from a work like this. Though not, as I hope, unlearned, yet it does not presume to address itself to the world of Oriental learning. Though not uninformed as to the method and the results of our rule in India, it does not undertake to supply information regarding the legislation, the administration, the land tenures, the trade and industry of a vast and varied Empire. Though it gives here and there the sum total of figures which, from their magnitude, deserve recollection and can easily be remembered, it presents no statistics properly so called. Though describing the ideas, the temper, and spirit of the Natives, it does not attempt any account of their customs, inasmuch as such an account would have to enter into the lives of the various classes in many nationalities. Though touching lightly on the historic eras and epochs which have preceded, or led up to, the present British era, it hardly essays even a synopsis of the antiquities and the mediæval history of the Indian continent and peninsula. Though routes and places are freely mentioned, yet the work is not at all a handbook in the technical sense of the term.

The real object of the work, then, is in this wise. There is a growing sense among British people regarding the absolute importance of the Indian Empire to the well-being of the British Isles. Consequently there must be an increasing number of persons who wish to acquire some knowledge which, though not profound nor adequate, is far from being superficial and is not wholly insufficient—who have an idea that the country must be picturesque, and desire to have some more definite notion as to what the beauties are. More especially the number increases of travellers who are unable, indeed, to undertake extensive travel, but who will make a comprehensive tour of six months, or at the most of a year. The benefit and pleasure to be derived from such tours are manifest to all thoughtful and cultured people. The enlightenment too is remarkable, provided always that the traveller be not tempted to pronounce offhand on questions which can hardly be determined except by long service or residence in the country. Such travellers would need at the outset some general explanation regarding the whole Empire, which would be in some degree sufficient, should they have no time for enlarged reading, and would help them to pursue any particular subject whenever they might require some study of details in other books. It is for persons of both these important classes that this work is intended.

For the names of places I have adhered to the old spelling in all cases where the word has been used for history in an English form—and most of the names in this book belong to that class. In other cases the more scientific spelling known as Hunterian has been adopted.

The book begins with an Introduction, Chapter I., setting forth the condition of India in the year 1897–8. That year happened to be one of misfortunes, for most of which a termination has been vouchsafed by Providence. The reader, so to speak, breaks ground in India itself by Chapter II. “A Winter’s Tour in India,” and by Chapter III. “A Summer’s Sojourn in the Himalaya.” These projects of comprehensive travel are followed by Chapter IV. on “The Forests and Wild Sports of India,” which things may or may not be connected with travel according to the disposition of the traveller. The Land having thus been touched upon, a brief description is given of the People, with their nationalities and religions, of the Native Princes with their Courts and camps, in Chapters V., VI., and VII. The Land and the People having thus been noticed, it is time to refer to the governance and administration of the country. As a preliminary to this, some account is presented of “The Frontiers of India,” in Chapter VIII., especially those on the north-west and the south-east. On this there follow Chapter IX. with the title “How India is Governed”; and Chapter X. “Progress of India under British Rule.” These ten chapters, then, comprise the essential substance of the work according to its original design. But perhaps a traveller or a student, who had proceeded so far and noticed so much as is assumed to have been the case, would desire to understand the broad outlines of the history and the antiquities, of all which he will have observed many traces, but which are too vast and complex for him to study with any minuteness. Therefore Chapters XI. and XII. have been added, on “Historic Remains and Ruins,” and on “Episodes in History and their Localities.”

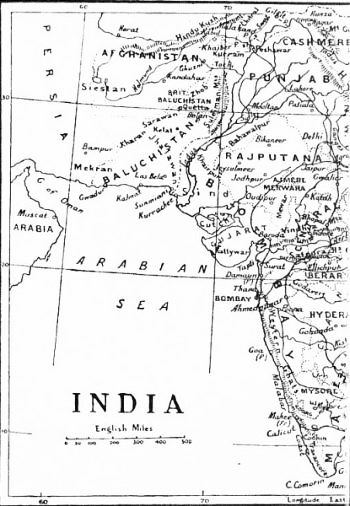

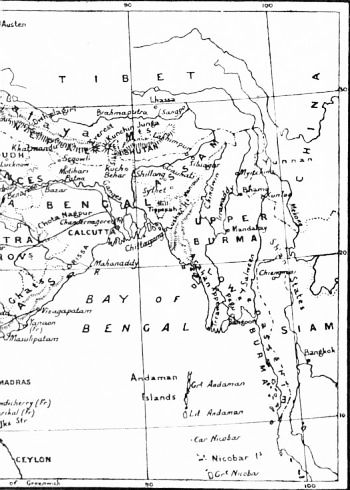

Although no statistics are embodied in the Chapters, still some readers might like to refresh their memory by an easy reference to leading facts, therefore in an Appendix are presented three tables: first, that of the principal figures relating to India; the second, that of the dates of the principal epochs in her history; third, that of the Governors-General and Viceroys. A compact map of India, kindly lent by the proprietors of “Whitaker’s Almanack,” is prefixed to the work.

Most of the facts mentioned in this work are the results of British heroism and endurance, yet there is no space for attempting any record of the heroes themselves, military, civil, political.

The aim throughout has been to render the exposition easy and popular. The subject, though interesting, is alien to British thoughts; though demanding a comprehensive treatment, it is yet, in many respects, highly technical. The difficulties are great in rendering it, on the one hand, easily intelligible to the ordinary English reader; and yet, on the other hand, technically accurate. I have tried to overcome these difficulties so far as may be possible. Moreover, many of the things as here set forth are, after all, matters of judgment and opinion, sometimes also of controversy. Many a page in this book contains allusions which might give rise to objections that could not be met without an explanation for which there is no space. So also, again, many a general consideration verges on details which might, from some points of view, be deemed essential, but for which, again, space could not be found; and consequently some sense of unavoidable incompleteness might arise. For all that is stated, however, there is my own cognisance, practice, study, and observation. He who shall master all that is written in this very limited work will know the substance of much that is best worth knowing, so far, at least, as my own knowledge goes after long experience.

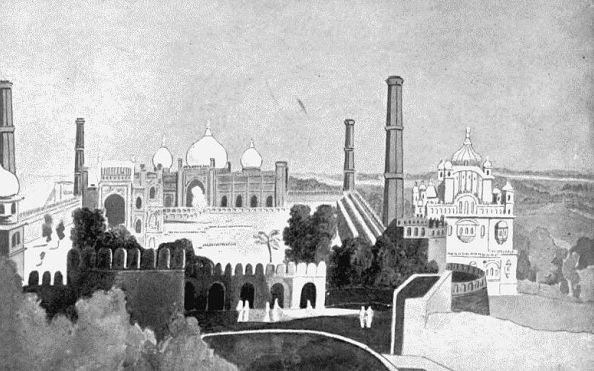

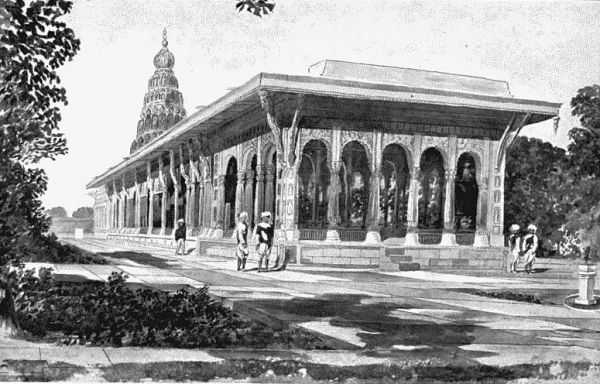

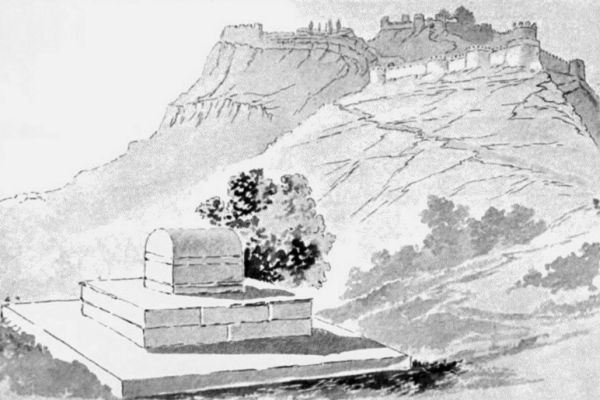

It may be well here to give some descriptive list of the illustrations. The number being limited to thirty-two, they have been distributed so as best to suit the tenour of each Chapter. The first Chapter, being introductory, has no illustration. The second Chapter, “A Winter’s Tour in India,” is illustrated (1) by a distant prospect of the promontories, the islands, and the harbour of Bombay; (2) by a view of the famous Taj Mehal, the gem of all India, as seen in the middle distance from the fortress of Agra—indeed, from the balcony where the dying Emperor Shah Jehan was placed to direct his last looks at the matchless mausoleum which he had erected; by views from (3) the citadel of Lahore, with the Mogul mosque and the tomb of Ranjit Sing, the Lion King of the Sikh nationality; and of the (4—used as Frontispiece to this volume) crossing of the Indus at Attok in the days before the great river was spanned by a railway viaduct, and as it must have looked when Alexander the Great crossed it; and (5) by a picture of the beautiful Eden Gardens on the bank of the Hooghly near Calcutta; next (6) by a picture of the carved teakwood vestibule of the temple at Nagpore, in the centre of India, being one of the few surviving examples of the woodwork for which the Mahrattas were once celebrated; and lastly, (7) by an outline of the rock of Trichinopoly, around which were waged some of the contests between the English and the French for the possession of Southern India.

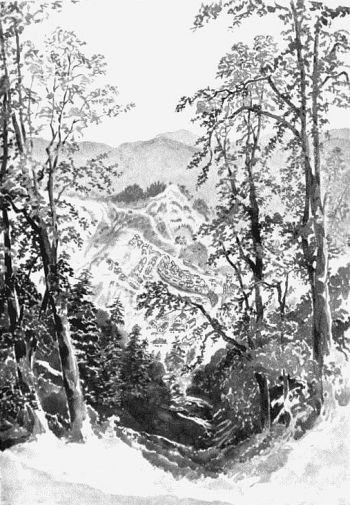

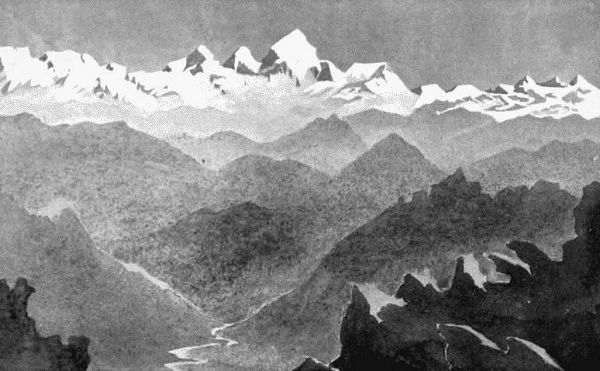

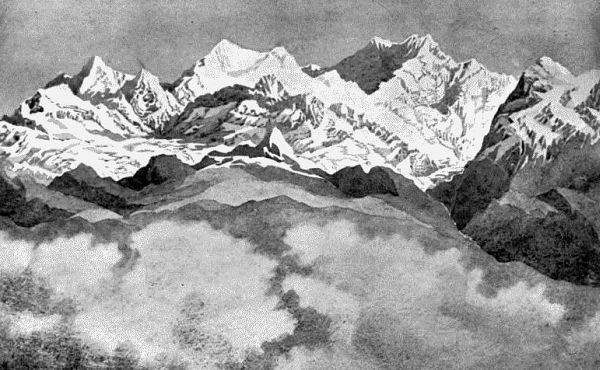

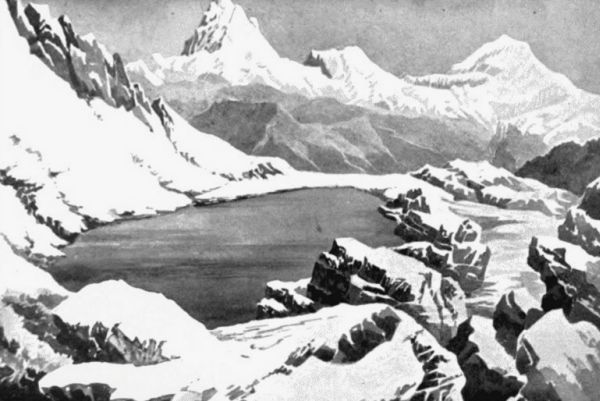

The third Chapter, “A Summer’s Sojourn in the Himalaya,” is illustrated by views of the (8) Sirinagar Lake in Cashmere, a sheet of water celebrated in song and story; of the town (9) and station of Simla, the summer retreat of the Viceroy and his Council, on the mountain ridge, seeming almost like a city suspended in mid-air, as seen from amidst the foliage of the Jacko Forest; of Mount Everest (10) as seen from the mountainous frontier of Nepaul; of Kinchinjanga (11) from the British hill-station of Darjeeling, these two being the loftiest summits yet discovered in the world.

The fourth Chapter, “The Forest and Wild Sports,” is illustrated by views of a tropical forest (12) near the western coast, south of Bombay, with a tarn; and of graceful bamboos (13) hanging over a stream; both places being just the spots whither the tiger comes to slake his thirst.

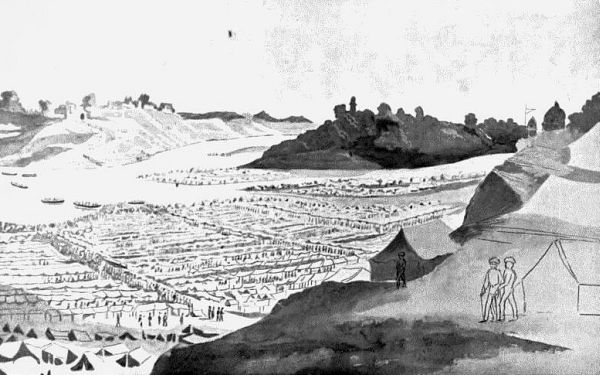

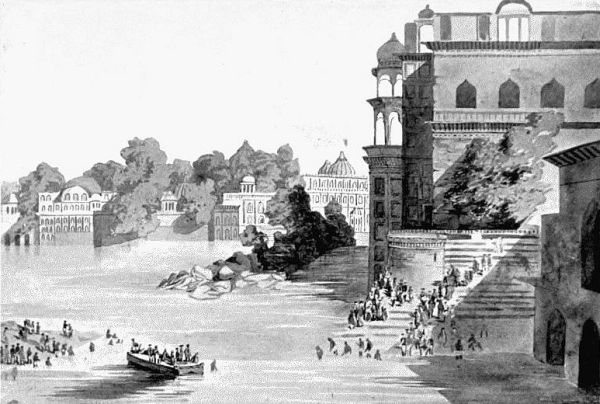

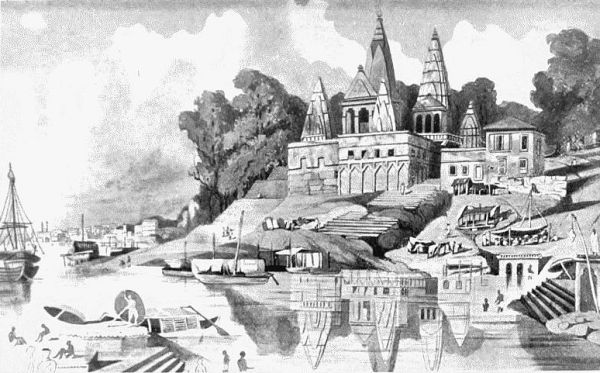

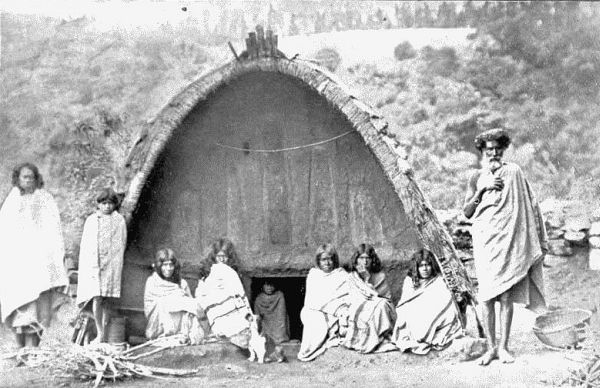

The fifth Chapter, “The Nationalities and Religions of India,” is illustrated by sketches (14) of a native fair held in tents at a religious festival on the banks of the sacred river Nerbudda, convenient for bathing with all the ceremonies of caste; of a gala company (15) on the stone steps of a sacred tank at Goverdhan, near Mathra, the scene of Hindu religious legends; (16) of the river Ganges, just below Benares, the chief city of the Hindu faith; (17) of a dwelling of the Aborigines in the Nilgherry Hills.

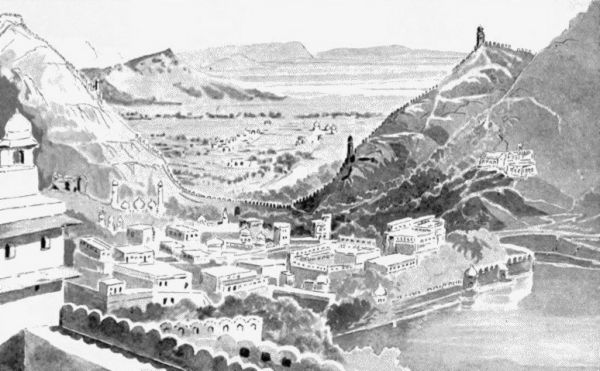

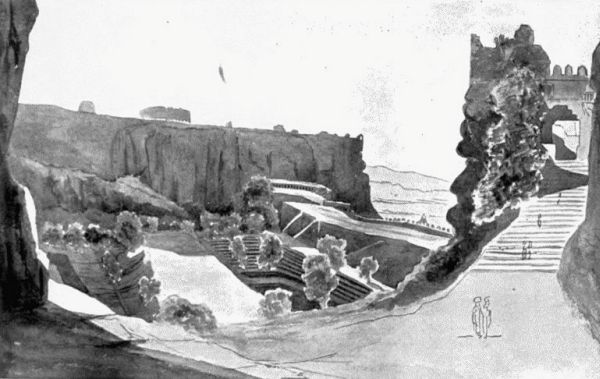

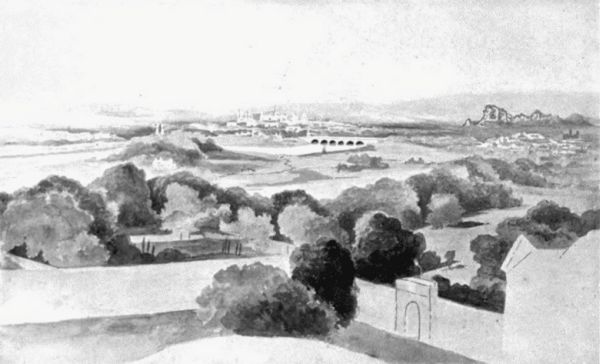

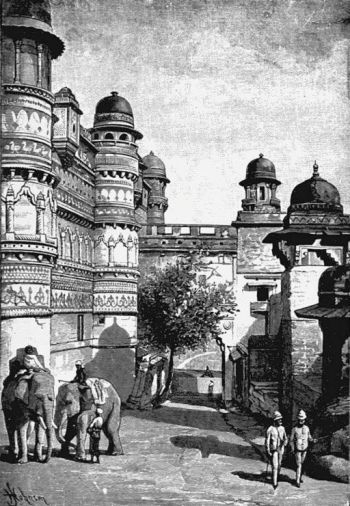

The sixth Chapter, on “The Native States,” is illustrated by views of (18) Ambair, near Jyepore, the principal State of Rajputana; of Gwalior (19), a leading Mahratta State; of Hyderabad (20), under a Moslem ruler, held to be the premier native State of India.

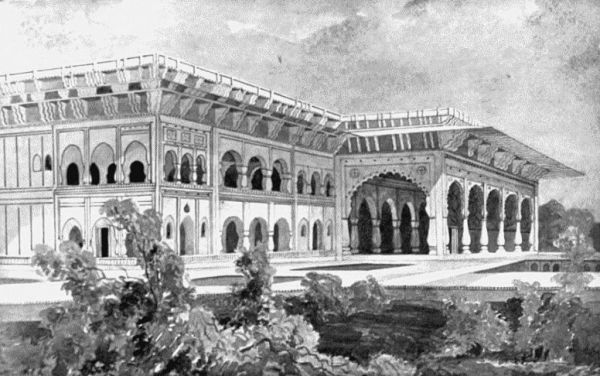

The seventh Chapter, on “The Courts and Camps of the Native Princes,” is not one that readily admits of illustration according to the method that has been adopted. Still, a sketch has been introduced of the summer-house (21) at Deeg, a native State near Bhurtpore, not far from the border of Northern India, perhaps the most perfectly graceful structure of its kind to be found in the Indian Empire; and (22) the Gateway of a Native Palace.

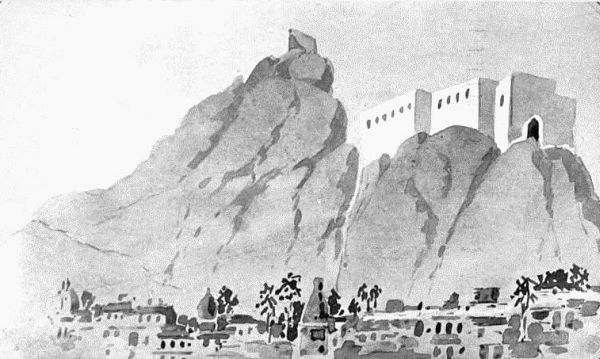

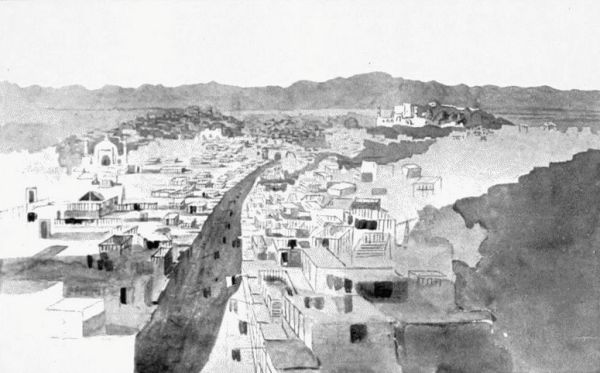

The eighth Chapter, on “The Frontiers of India,” has four characteristic views: of the Sikkim-Tibet border (23) in the cold and snowy north; (24) of the Peshawar city, with the Khyber Pass in the background—which was the head and front of the recent frontier campaign—the pools (25) of the stream that runs through the Bolan Pass—leading from the Indus Valley towards Southern Afghanistan; the last two being for the north-west and west, and then of the river Irawady (26) in Burma for the east.

The next two Chapters, the ninth entitled “How India is Governed,” the tenth relating to the “Progress of India under British Rule,” do not admit of illustration in this manner.

The eleventh Chapter, on “Ruins and Historical Remains,” has two illustrations: one relating to the interior of the redstone temple (27) at Bindraban, near Mathra, not far from Agra, being quite the finest interior in any style of architecture throughout India; the other to the great tower at Booddh Gya (28) in Behar, being the stateliest monument remaining to recall the Booddhist era.

The twelfth Chapter, on “Episodes in History and their Localities,” is illustrated by a sketch (29) of the Pertabgurh rock-fortress, at the base of which the Mahratta Sivaji assassinated the Moslem envoy, and so set in movement the insurrection of a Hindu nationality against the Moslem Empire; and (30) by a picture of the temple-crowned rock in the midst of the lake at Poona, whence the last of the Peshwas watched his forces being beaten by the British troops, an event which terminated the Mahratta Empire and left it to be succeeded by that of the British.

To the above illustrations have been added (31) one of the Sacred Bull of Tanjore, a granitic monolith, remarkable because the nearest formations of granite are hundreds of miles away; and (32) one of the grey stone temple near Islamabad in Cashmere.

There is yet one more topic to be mentioned at the conclusion of this Preface. After the book had been composed, but before it was completed, certain events occurred, some of which already are affecting India indirectly and may affect her in the future more and more, but of which a notice could not be conveniently included in the body of the work. I allude to the recent development of the British sphere of influence and of commerce in China. Now, without following the ramifications of this immense subject in many directions, all persons connected with India will have observed that one outcome of this affair will be the inclusion of the whole Yangtse River basin in that sphere, at least as far as the rapids and the mountain range which separate the mid-valley of the Yangtse from its upper valley in Czechuen and Yunan. Within the borders of Yunan the river Yangtse is called by British geographers the River of the Golden Sand, and under that name it approaches the Yunan plateau near Talifoo. This plateau overhangs the valleys of the Mekhong; and the Salwin (as will be seen in Chapter VIII. of this book) touches the Shan States of Burma, belonging to the Empire of India.

Now, from Mandalay, the capital of Ava or Upper Burma, a British railway has been undertaken towards the Chinese frontier in Yunan. Capital has been provided and the project has received the State sanction, for the first part at least. The surveys and other preliminary operations have been or are being conducted as far as the ferry of Kowlong on the Salwin River, which just here is the boundary between the British and the Chinese Empires. Under the circumstances which have arisen in consequence of recent events, it is to be hoped, indeed expected, that the British Government will press on this railway to speedy completion right up to the Salwin. Naturally the line will not stop there, but must eventually be carried on to the Mekhong River and across its basin to the base of the Yunan plateau. This extension will require the sanction of the Chinese Government. The further enterprise, at the time of the project being initiated, was a matter for negotiations of which the success was more or less doubtful. But in the alteration, indeed the radical improvement, of our relations with China, there should be no longer a doubt as to the success of any arrangements of this nature. Again, this line, with the application of the needful energy and resources, might possibly reach the base of the Yunan plateau in the course of three or four years. But it would not stop there: it must ascend the plateau, which has an altitude of a few thousand feet, by inclines practicable for engineering. Once on the plateau, it would proceed to Talifoo, an important commercial point in the Yunan province. That station would then be within measurable distance of the River of the Golden Sand, which is really the Upper Yangtse. It were premature now to estimate the progress onwards in future years through the Czechuen province towards the mid-valley of the Yangtse, which would be the goal of the long enterprise.

Thus British communications are pressing slowly but, as we hope, surely, on the great Yangtse valley from Shanghai on the east to Mandalay on the west. From Mandalay there is now a railway to Rangoon near the sea. So the main British line of the future, apparently marked out by destiny, is from the Bay of Bengal at Rangoon to the Pacific Ocean near Shanghai, a distance of about three thousand miles right athwart the south-eastern part of the Asiatic continent from sea to sea—one of the finest lines for the march of Empire to be found in all Asia.

WEST INDIA

From ‘Whitaker’s Almanack’

[by permission]

EAST INDIA

From ‘Whitaker’s Almanack’

[by permission]

I propose to give some account of India in her romantic and picturesque aspects. In no year since the beginning of British rule has she been more prominently before English eyes than in 1897. The Diamond Jubilee of the Queen Empress brought many of the native representatives to England. Though not native Sovereigns of the first rank, many of them were native Princes, others were nobles; and many were soldiers, no doubt carefully chosen by the Government of India for their martial bearing, their war-record, their social status, in addition to military rank. Certainly they represented India handsomely and gracefully. They gave to Englishmen a favourable idea of the inherent manliness and of the true gentility pertaining to the best classes of native society. They doubtless inspired many of our countrymen with a desire to know more, and if possible to see something of the land whence these people came. They suggested by their presence the thought that the birthplace of such picturesque figures must in itself be replete with pictorial effect.

But this ideal mind-picture of India in 1897 has had—like realistic and material pictures—its deep shades as well as its high lights. For few years have seen such long and ever lengthening shadows been cast right across India from end to end as the year just passed, namely, 1897. These sorrows sprang upon her just at the zenith of her strength, her prosperity, and her splendour. This was indeed providentially fortunate, inasmuch as the burden fell upon her at a time when she was fairly able to bear it. The year opened with one of the severest and most widespread famines ever known, extending over various provinces in Northern and Western India, and in several districts elsewhere. India has always been the land of famine, arising from atmospheric causes of a far-reaching character quite beyond human control. For now nearly two generations the British Government has striven to prevent famine by constructing works of irrigation, the finest known in any age or country. But prevention by these means is found to be impracticable though the possible area is contracted. Still during the same era Government has devoted its energies and resources to averting or mitigating the consequences of drought and dearth. On this dread occasion the Indian people faced the calamity with all the old endurance for which, indeed, they have been proverbial. The Government combated the sufferings with all the old resourcefulness and administrative capacity for which it has been famous. The sympathies of England were aroused, and the subscriptions for relief of famine exceeded half a million sterling, the largest sum, or one of the largest sums, ever raised for a charity of this description. These efforts in the British Isles, and in India itself under British auspices, were beginning to prove successful, and were blessed by such improvement in the season as gave hope of a speedy recovery, when a new trouble was added in the shape of plague and pestilence.

During the spring the plague appeared sporadically in Western India, and then became for a while endemic in Bombay, decimating the inhabitants in some quarters of the great city, and causing such an exodus of the busy population as to paralyse for a while the industry of this queen of Asiatic commerce. This was on the coast at the foot of the Western Ghaut Mountains. Then the plague crossed the mountains and appeared at Poona, a great civil and military station, and the capital of the Bombay Deccan. Meanwhile the Government of Bombay had been doing its utmost to check the evil, by internal sanitation in dwellings, by disinfecting processes, by isolation of distressed localities, and so forth. This benevolent work, designed solely to save the lives and to promote the health of the people, was introduced at first in Bombay and soon extended to Poona.

Then at Poona certain persons pretended that this good work was vexatious and oppressive. On this particular ground the people were urged by seditious publications to rebel. Two meritorious English officers were actually murdered on this very pretence, and the murderers were not at the time discovered.

Soon it became evident that the treason went further and deeper. Newspaper articles were published invoking the memory of the national hero Sivaji, who more than two centuries ago raised the standard of Hindu revolt against the Great Mogul. With an eloquence peculiarly appealing to the Hindu mind, the people of to-day were urged to treat the British in the same way. At least to the British understanding this was the substance and tenor of the admonition. All this was done not at all by ordinary natives but by men who had been at our schools and colleges and had studied at our University in Bombay. At first sight it was most discouraging to see such an outcome of Western civilisation. There had been mutterings of the storm for some time in the native press. After long-suffering patience, which had perhaps been too far protracted, the Government acted with its wonted energy. Criminal prosecutions were instituted; several natives of social consequence were brought to the bar and received judicial sentence. These proceedings checked the publication of seditious and treasonable matter. Hardly any overt act of rebellion occurred. But nobody supposed that the inflammable material had been removed, although the rising flame had been stamped out. Indeed those who, like myself, are thoroughly acquainted with that locality and with the people concerned, know well that in and about Poona there resides in some bosoms an inextinguishable hatred against British rule,—implacable notwithstanding humane legislation, just laws and honest administration.

Thus in the summer, just when England was ringing with the Jubilee cheers, when the colonies and dependencies from every clime were swelling the chorus of congratulation, when the inhabitants of the British Isles were giving munificent proofs of sympathy with their Asiatic fellow-subjects, when the Indian Government was signalising itself by immense efforts for the sake of suffering humanity, treasonable symptoms of the worst kind manifested themselves in Western India. Never was mischief of this sort more ill-timed. The people of England were perhaps too much absorbed in the Imperial triumphs of the moment to pay close attention to the matter. But they thought it dangerous, and wondered why this time of all other times should be chosen for such manifestations. This wonderment of theirs is shared indeed by those who are most experienced in these affairs. The truth probably is that in that particular quarter the discontent is abiding, and only awaits any chance event that may seem to promise an opportunity. It was thought by the evil disposed that such an opportunity might be afforded by the dissatisfaction, real or supposed, of the people, at the measures taken for the prevention of the plague. Never was benevolent effort more unjustly misunderstood.

But the apprehension of people in England regarding these events soon became quickened. For rioting, not amounting to rebellion, but still most grave, broke out very soon in Calcutta. A dispute arose about a building and some land claimed for a mosque, regarding which a judicial decree had been issued. The affair was small, but the mob became great, and the rioting spread largely before the authorities were able, by the employment of troops, to put it down. After these events, first on the west, then on the east side of India, rumour came in with its hundred tongues. Insolence of demeanour before Europeans, ominous expressions casually dropped, were commonly reported; and no doubt many Europeans, who ought to be well-informed, did think that an unaccountable spirit of unrest was in the air. As this became known in England some genuine alarm was felt by many Englishmen. It was graphically depicted in an eminent London weekly journal by an illustration of the tiger. I often heard them ask whether there was not going to be another Mutiny, alluding of course to 1857. This would presuppose or imply some sinister signs in the native army. But in truth in 1897 there was not the slightest trace of this. On the contrary, the native army was sorely tried during this very year, and evinced the most gallant loyalty.

Then another physical calamity supervened. Earthquake shook parts of Calcutta, and appeared with still greater force in the valley of the Brahmaputra, underneath the eastern Himalayas, threatening the tea-producing regions. The station of Shillong in Assam was nearly destroyed. India is indeed a buoyant country; still this recurrence of calamity must have caused some gloom to settle down on the public mind.

Immediately, however, a new excitement arose in a widely different and distant part of the country. Far away on the North-West frontier, near Peshawar, and round about the celebrated Khyber Pass that leads towards Caubul, there was an uprising of the independent tribes that occupy a long though narrow belt of mountains between the Indus valley and Afghanistan. It was found that fanatical Moslem priests had been stirring up all these wild and intractable tribesmen to resist, and if possible drive back, what were considered the British encroachments on their territories. Whether this fanaticism had anything to do with current events in Europe relating to the Sultan of Turkey had never been ascertained exactly. At any rate the movement grew and grew, not only in extent, but in vigour and organisation, till it became the biggest affair of its kind ever known on that famous frontier during the half-century of British connection with it, say, since 1849. Uprisings of this kind—attacks really upon British outposts or upon British villages near the base of the mountain-line—have during the half-century been chronic, that is, ever-recurring from time to time, and are expected to be so. The region has long been known favourably in military circles as a capital school for soldiers, both European and native. We have always acknowledged and respected the independence of these tribes within their own borders—that is, their mountains. Practically, they have never been quite satisfied with that, and would like to lord it over the fertile tracts near the foot of the hills—tracts which never were their territories, but which belonged to the Punjab kingdom before us, and to us since 1849. Doubtless we have protected our own ground, and punished invasions of it more effectively than our predecessors ever did. Hence the several frontier expeditions, some twenty-five or thirty in number within the fifty years, always of a punitive character, of which the world has heard from time to time. These have always been short, sharp, and successful, without ever attaining any considerable dimensions. They have generally been settled with our native troops only, and with the employment of Europeans in small numbers or not at all. But this uprising in 1897 was a far larger and more formidable affair, requiring a whole army corps, with a goodly proportion of European troops. Indeed, according to some calculations, the forces employed, including those in the front and those in reserve, amounted to two army corps. It really constituted something like a new departure in frontier history. It was not concluded within the year 1897; but early in the next year, 1898, the conclusion was held to have been attained by the submission of the last of the insurgent tribes. Hereafter this grave case will need thorough examination as regards the past, the present, and the future. Suffice to say that the conflict—though ushered in by fanaticism—raged mainly in reference to the occupation and guardianship of certain passes, notably among them the Khyber Pass, leading from the Indus valley into Afghanistan, which the Government of India claim the right of guarding in the interests of the Empire. At first it was thought that the occupation of Chitral might have been at the bottom of the affair, but this is now found not to be the case. The Chitral tribes have been either friendly or quiescent. The insurgents belong to other tribes with different objects in view. Still the wonder remains as to how these tribes, heretofore separate in their conduct and in their objects, should on this occasion have combined in such large numbers for one or two common objects. Inquiry has probably yet to be completed as to what these objects were. At present I believe they relate mainly to the passes. I will not now pursue this subject, save to remark that nothing could be better than the behaviour of the native troops of the British army throughout these arduous operations. In this work, too, some of the troops of the native Princes of the Empire have had an honourable share.

India always has been a land of peril, of calamity, and of emergency, despite all her splendid advantages. In British history she has gone through two awful years, 1857 and 1858, the like of which we, the witnesses, in part or in whole, hope never to see again. Still for a time of peace, of general prosperity, of political success, the year 1897 has been an annus mirabilis. Famine, plague, earthquake, treasonable sedition, rioting, frontier warfare—occurred one after the other, all within a few months. So to speak, the curtain has fallen on one scene only to rise on another. But in the following year, 1898, a large part, though not the whole, of these clouds passed away from the political sky. The seasonable rains not only relieved famine, but even ensured plenty. Quiet was restored on the North-West frontier. The plague-stricken population of Bombay did indeed resume their industries with renewed health. But in the spring of 1898 there was a recrudescence of the plague, and soon the pestilence appeared in Calcutta, in Kurrachee, and other places. The consequences of this devastation are still severely felt.

With all these extraordinary occurrences India failed to share fully in the Jubilee joyousness which reigned in all other parts of the British Empire. Still, in the following year, 1898, she retrieved much of her passing misfortunes, and she still stands socially erect.

Besides these actual dangers or misfortunes there was one threatened danger from which India has been preserved by the firmness of the Government in India and in England. For some time past, by closing its mints to coinage of silver, the Government of India has sustained the exchange rate of the rupee at a certain standard which is compatible with the safety of the Indian finances and of other great interests connected therewith. Certain proposals came from the United States of America, which were, indeed, designed for improving the value of silver, but which involved the reopening of the Indian mints to coinage. By the rejection of these proposals India was saved from financial peril at a time of exceptional suffering and trouble. But the anxiety was renewed in the following year, 1898, and the whole subject is under inquiry by the Government in England.

I have deemed it necessary to recount these circumstances of 1897, as largely alleviated in 1898, before describing India as she is in all her beauty. They could not, indeed, be properly passed over in silence; if they were, then my survey might be deemed optimistic. A description of India to be true must be bright and cheerful, but the interest is enhanced by remembering that behind the brightness and cheerfulness there ever lurks danger and possible disaster. Still, the dangers are always overcome and the disasters retrieved. On the other hand, any gloomy or pessimistic description of India is sure to be wrong. If my picture shall be rightly painted the lights and the shadows must be duly apportioned, though, as in other bright pictures, the lights will be dominant.

When entering on the field of Indian picturesqueness I feel like one who looks on some vast collection of beautiful objects, say the National Gallery or Kew Gardens, and knows not where to begin his survey. But in order to make my summary—for it cannot be more—both practical and popular, I shall conduct the reader in imagination through the Grand Tour of India—thus touching on most of the finest points in the country.

Such a tour is being made more and more frequently year after year by increasing numbers of English ladies and gentlemen. The ladies generally return with their spirits enlivened, and the range of their imagination much widened. The gentlemen come back full of ideas derived from knowledge which is real so far as it goes, provided that they do not think too much of the knowledge they have thus acquired, and suppose themselves to know more than could possibly be known on a very short acquaintance. They benefit immensely by the journey in mental strength and in the grasp of Imperial affairs. It is satisfactory, too, that they always seem to be deeply impressed by the organisation of British rule in the country.

The tour I am about to sketch must be made in the winter, the climate renders this obligatory. The winter in India is finer even than that of the Riviera, or of Southern Italy. The spring and summer are so hot as to be prohibitory, and the autumn is unhealthy. Therefore the tourist must leave England by the first weekly overland mail of October, so as to break ground at Bombay by November 1. Then he may well remain in India till the first homeward mail in April. Thus he would have five months, November, December, January, February, March, for his tour, which, if really well directed, is one of the most magnificent that can be taken on earth. I shall suggest the line or lines that can best be followed, premising that I have myself been to all the places which will be recommended, and that with many of them I have had long and intimate acquaintance.

I shall, however, have to touch but very lightly on each place, passing always quickly, as on a rapid tour, the country being a flowery mead, where the traveller, like a gay butterfly, flits from flower to flower.

At Bombay, the western capital, the tourist would have no time to stop and examine the various institutions, unless, indeed, there might be some particular, say, educational, institution in which he took an interest, and which could be looked at in two or three hours. But he should make sure of seeing from some point on Malabar Hill, say Malabar Point, the Governor’s Marine Villa, the long and magnificent series of public buildings, one of the finest sights of its kind in the world. The buildings are in themselves grand, but other cities may have structures as grand, though probably separate. Bombay, however, has all her structures in one long line of array, as if on parade before the spectator. And all this is right over the blue bay, with the Western Ghaut Mountains in the distant background. This constitutes a noble introduction for the traveller to picturesque India.

Then we pass through the vast harbour of Bombay, with a comparatively narrow mouth, guarded by fortifications, surrounded by hills, and studded with islands—again with a mountain background. This harbour is in the very first rank of the harbours of the world, taking an equal place with Sydney, with San Francisco, with Rio de Janeiro. The immediate purpose is, however, to visit the island of Elephanta in the inner part of the harbour and see the Cave temples, rock-hewn chambers, with massive figures and antique devices, offering a wondrous spectacle to a new-comer from the Western world.

Then the traveller should determine on broad considerations the route he is going to take from one end to the other of the Indian continent. There are, of course, several alternatives, but the one which I shall adopt is as follows. First, let us proceed through Goojerat to Ahmedabad—with a possible diversion to the cluster of native States in Kattywar—and back to Bombay; a trip of only two or three days. The traveller would thus see the most fertile coast region in India, with some wonderful railway bridges over deltaic rivers, and some strange specimens of Moslem architecture, unique of its kind. It would be well to make this excursion, which is easily made now, but for the making of which no opportunity will recur.

Returning to Bombay, the traveller should start at once for the distant Panjab, by way of Central India and Rajputana. The railway would carry him to the foot of the Western Ghaut Mountains, not far from the new waterworks, with a dam, probably the most massive in the world; then up the mountain sides to Nassik and onwards near Asirgurh, the imposing hill fortress dominating this part of the main line between Bombay and Calcutta. Descending into the valley of the Nerbudda, and, crossing that river, he would ascend the Vindhya Mountains and reach, near Indore, the great cluster of native States which is called Central India. There is nothing to detain him at or near Indore, unless he should be able to spare two days or so to visit the fine ruins of Mandu, once a city with a stately court and camp, but now, since some centuries, a typical instance of absolute desolation. From Indore he might, if possible, diverge to Oodeypore, the noblest of all the Rajput States, which is signalised by the architecture of its palaces overlooking lakes. Thence he would proceed to Jeypore, the wealthiest of the Rajput States. The laying out of the modern capital is a good instance of native skill. But even more interesting is the old and half deserted capital at Ambair, full of good specimens of ancient Rajput architecture in the Hindu style, both as regards palaces and fortifications. Then he may pass by Gwalior, belonging to Sindhia, the first among the Mahratta States, and a striking instance of those natural fortresses formed by rock masses rising abruptly out of the plains, in which India abounds. Then he would cross the river Jamna and enter Hindostan.

The plain of Hindostan—the upper basin of the Jamna and the Ganges—is the most important part of India, the scene of Hindu sacred legends, the Imperial seat of the Great Mogul. The traveller soon arrives at Agra, to contemplate the red sandstone palace-fortress of Akber the Great, the first of the Great Moguls, with its “pearl-mosque,” resplendent in white marble against the azure sky. He stands in the balcony whence the dying Emperor Shah Jehan took a last look at the distant Taj Mehal, the peerless mausoleum which he had erected for his dead Empress. A short drive takes the tourist to the Taj Mehal, the shrine which has immortalised a Mogul Empress, the finest instance of architecture in marble ever known, superb in its swelling dome, in the proportions of its structure, in the climatic conditions which have preserved the loveliness of its material almost unimpaired, and by common consent the queen of beauty among all structures in the world. Thence he soon journeys to Delhi, the opening scene of the tragedy of the mutinies in 1857. Again he sees a red sandstone palace-fortress overlooking the Jamna, and close by the Jama Mosque, in the magnitude of its style and its material, red sandstone picked out with marble, the finest mosque ever erected in the many regions over which the faith of Islam has spread. He drives over the remains of dead cities, and realises that there have been several Delhis close by, and before the present Delhi. After reverently contemplating the ridge before Delhi, the scene of British heroism and endurance during the memorable siege of 1857, during the Mutinies, he sets his face straight for the river Satlej and enters the Panjab.

On his way to Lahore he may stop a few hours at Umritsur to see the gilded temple in the midst of a lake—the headquarters of the Sikh religion. At Lahore, the capital of the Panjab, he would pause briefly to notice the city walls and the mosques, again remarkable for their material, among which may be reckoned the colours of the earth-enamel, matchlessly beautiful, the product of an art now lost. He will observe the comparatively modern tomb of Ranjit Sing, the Lion of the Panjab, the founder of a kingdom which made the Sikhs a nation.

Thence he would hurry northwards, crossing by mighty railway viaducts the Chenab and the Jhelum, and recalling the marches of Alexander the Great, till he reached the Indus at Attok, the most celebrated of the river crossings in India. This has always been an Imperial point in the history of many Asiatic dynasties, and he will find the swift river rockbound between lofty sides, in its weird picturesqueness worthy of its historic renown. Soon the railway carries him to Peshawur, which, though full of prestige and celebrity, has few objects of interest. But a short ride will take him near to the mouth of the Khyber Pass, close enough for a glance into the gloomy portals between India and Afghanistan.

By this time he will probably feel the difference between the sharp bracing climate with frosty nights, and the mild moist atmosphere as felt when he landed in India. The whole of this vast distance he will have accomplished by railway within a very few weeks. During his passage through the Panjab he may, at lucky moments in favouring weather, have caught glimpses of the snowy range of the Himalayas.

He must now quickly retrace his steps towards Hindostan, not, however, returning to Delhi, but bearing to the north and nearing the Himalayas near Deyrah Dhoon. If he should have leisure to diverge, for two days or so, to Hardwar, to visit the engineering works at the head of the Ganges Canal—the finest works of their kind in the world, seen, too, with a mountainous background—he would do well. But he may not have time. So he would hasten on through the Gangetic valley, to Cawnpore, not itself remarkable for anything save the pathetic monument over the well where the British victims of the mutinies found the rudest of tombs. He would there consider whether he has time to diverge for two days or so to Lucknow, a place illustrious in British annals, but not externally remarkable, inasmuch as its Moslem architecture is second-rate, and will appear to be utterly inferior after the superb examples he has been seeing at Agra, Delhi, and Lahore. At all events he must proceed past Allahabad, at the confluence of the Ganges and the Jamna, and the largest junction station in India, to Benares. A day or two days he must give to Benares, the capital city of the Hindu faith. Passing gently down the stream of the Ganges in a boat he sees the finest river frontage in India—a long series of palaces and conical temples with flights of stone steps down the steep bank to the river, crowded with persons pressing onwards to dip in the sacred water. If he desires to study Christian Missions, now is the time and here is the place for this purpose.

He must now make a straight run by railway to Calcutta, not pausing much at the Imperial capital with its many institutions. Still he will notice Dalhousie Square, a small lake surrounded by public buildings—the finest square in India—the long lines of structures, public and private, facing the great green plain, the Eden Gardens on the Hooghly bank alongside the ocean-going ships, the broad river filled with shipping like the Pool of the Thames. He has now reached the limit of his grand tour, and will henceforward be on his way home.

From Calcutta he should make a straight cut across the country to Nagpore, in the very heart of India, by the railway which has in recent years been constructed. Heretofore his railway journeys will have taken him across mountain ranges and along never ending plains, verdant with the young rising crops of the cool season. But now he will, from his carriage windows, obtain some idea of the forests and jungles of India. From Nagpore—the capital of the Central Provinces, at which place there is little save Mahratta structures of some beauty and interest to detain him—he should proceed through Berar to the Bombay Deccan en route to Poona. If he could spare two days or so to visit the rock-hewn temples, commonly called the caves of Ajunta, he would do well, especially as he would hardly have time to visit the sister caves of Ellora. These gloomy chambers in the heart of the black rock formations, with statues and images of the grandest designs, are of unique interest. Poona is replete with historic associations as the old headquarters of the Mahratta Confederation, whose empire in India was superseded by that of the British. It is also fraught with grave political considerations at the present time. But it has few sights to offer, except the lake with the temple-crowned rock in the midst.

Here again the traveller would do well if he could spare four days or so in order to diverge to Mahabuleshwar, the summer residence of the Bombay Presidency. The scenery is wondrous, with the vast face of the mountain range and the mighty walls of laminated rock right over the coast region with the Indian Ocean on the western horizon. Prominent in the view is the square tower-like hill of Pertabgarh, where two centuries and a half ago Sivaji, the Mahratta, by assassinating the Moslem envoy, raised the standard of Hindu revolt against the Muhammadan Empire.

Returning to Poona the traveller may proceed to Hyderabad, the Nizam’s capital. The sights at Hyderabad, gateways, mosques, and the like, are fine, but hardly in the first rank, and in the Nizam’s Palace there is nothing to see. Still, he would gather some idea of the pomp and state, the court and camp, the political and social atmosphere of the largest among all the native States of India. He might devote one day to Golconda, called the City of Tombs, because it contains the mausoleum of an entire Moslem dynasty.

From Hyderabad he should proceed to Madras. There is not much, save the public structures and the new harbour, to detain him in this, the capital of Southern India. But he will proceed, passing by Vellore and Arcot, memorable for those contests of the last century which decided the question whether the Empire of India should go to the French or to the English. So he will reach the foot of the Nilgherry Mountains, the summer resort of the Madras Presidency, and ascend to the plateau of Octacamund. From these heights he will survey an ocean of lower hills, rising and diminishing just like billows, with the Nilgherry—literally blue peak—towering aloft, and the shimmer of the Indian Ocean on the horizon.

Descending to the plain, which has now become the Southern Peninsula, he will visit the Rock of Trichinopoly, famous in the record of British heroism, and the noble temples of Tanjore. He would have a glimpse, too, of the magnificent system of irrigation in that region. Still journeying southwards he reaches Madura, containing unsurpassed examples of Hindu sacred architecture. He might possibly make a diversion to Travancore, with luxuriant vegetation, but probably there would not be time for this. Further to the south he would visit the Christian Protestant missions in Tinnevelly, the field where Christianity has most widely spread among the natives, and has most firmly taken root. Thence he would soon reach the southern extremity of India, and crossing over to Ceylon would embark at Colombo by some mail steamer bound for England.

I must allow that by this programme of travel, the Marble Rocks at Jubbulpore, which constitute one of the natural gems of India, would be omitted. The only remedy would be to visit them by an excursion from Nagpore, for which, however, there might not be time. The great irrigation works on the east coast have not been included. But time might be found for visiting them from Madras, if the traveller should feel a special interest in the subject.

If this programme, this itinerary, this projected tour, were accomplished in the five months, it would constitute a grand record of travel. I believe that it could be done, provided that the traveller were not tempted to linger anywhere unduly. But comprehensive as its scope may be, it unavoidably omits Sind and Burma, and also the river-kingdom of Eastern Bengal with Assam.

Finally it does not touch the grand region of the Himalayas, of which I shall treat in the next chapter.

DISTANT VIEW OF BOMBAY HARBOUR

TAJ MEHAL, FROM AGRA FORTRESS

LAHORE CITADEL

EDEN GARDENS, CALCUTTA

TEMPLE AT NAGPORE

TRICHINOPOLY ROCK

The last preceding chapter on the winter’s tour on the continent of India did not include the Himalaya. The name Himalaya is Sanskrit, meaning “the abode of snow.” On such a tour some glimpses of the Himalaya may occasionally be had. But a visit to the Himalaya cannot be combined with a tour on the Indian continent, because it must not be made in the winter. During that season the region is under snow, and to attempt a visit then would be like visiting the higher Alpine districts in January! Nevertheless the Himalaya, though not geographically belonging to the Indian continent, is technically a part of India—has been in all the ages looked up to with sacred awe by the Hindus as the celestial abode, and is the most grandly picturesque part of the whole British Empire. Therefore the English traveller should by all means visit it, if he can. But in that case he must make up his mind to a year’s stay in India—leaving England in October of one year and returning towards the end of the following year. When thinking of a journey to India English travellers often say that they would above all places like to see Cashmere. Yes, certainly it is one of the places best worth seeing in the world, but this cannot be included in the winter’s tour. As it is inside the Himalaya, a visit to it would involve a whole year in India as already explained.

At all events the Himalaya cannot be excluded from the survey of Picturesque India. But differing as it does from the continent of India proper in most though not all respects, it had better be treated separately. For this purpose I will suppose that the traveller had decided to visit the Himalaya together with India and is prepared to give the year’s time that would be required. In that case it would be best for him to take in reverse, so to speak, the grand tour sketched in the last article. Or better still let him proceed to Colombo, arriving there very early in November—instead of Bombay—and thence cross to Southern India, taking Tinnevelly, Madura, Trichinopoly, and the Nilgherries, to Madras. Thence he will proceed by Hyderabad and Poona to Bombay. After a brief stay in Bombay he would proceed straight to Calcutta through Berar and Nagpore. From Calcutta he would work his way up the Gangetic valley by Benares, Agra and Delhi to the Panjab—then through the Panjab by Lahore to Peshawar. By this time the tour will have occupied the winter, and the spring will be advancing. Returning from Peshawar and recrossing the Indus at Attock, he would stop for a moment at Rawalpindi not far off at the base of the Himalaya—say about the end of March. The various localities above mentioned have been already touched upon in the preceding chapter.

From Rawalpindi he may begin his tour in the Himalaya, remembering that the places to be seen in one summer are many and that there will be very little time for marching amidst the mountains or for pursuing sport. If any time be given to sport it must be deducted from the tour. If the traveller becomes for a while a sportsman he will indeed see some parts of the Himalaya extremely well, but he will fail to make any round of the Himalaya as a whole.

Let us suppose then that he breaks ground at Rawalpindi, not far from the Indus, in the very beginning of April, and rides up to Murri, the principal summer resort for the European society of the Panjab. The season will not have begun and the place will be comparatively empty; but he will have his first introduction to Himalayan scenery, at an altitude of 6000 to 8000 feet above sea level. He will see more of forests than of rocks, but will be struck by the true Himalaya, or abode of snow, a line of snowy peaks looking as if massed together like one long white wall against the sky, and trending towards Cashmere, his immediate goal. From Murri he marches a short way into the mountains, and then makes a sharp and steep descent to the valley of the Jhelum. He follows the course of this river upstream for a few daily marches to the Bara-Moolla Pass. Emerging from this pass he finds himself in an upland plateau surrounded by mountains, with an extensive vista looking eastwards, and, lo, this is the Vale of Cashmere, of which the main artery is the river Jhelum. The wondering delight of every traveller on first beholding Cashmere is proverbial. The valley may be and often is approached by other routes besides that of the Bara-Moolla. But this latter is the only one by which it can be entered so early in the season as the beginning of April. The fair region is essentially a valley of lakes; so he first sees the largest of these lakes, and then, following the course of the Jhelum, pushes on to Sirinagar, the capital, built, like Venice, on canals, and having a lake of consummate beauty, on the margin of which the Great Moguls built their summer palaces. These are the sweet spots of which the poet Moore had dreamt when he sung his “Lalla Rookh.” Here the traveller should ascend the hill, Takht-i-Suleman (Solomon’s Throne), which juts out from the main range, standing a thousand feet or more above the valley. The panorama seen from this lofty standpoint is never forgotten. The whole of Cashmere, encircled by snowy ranges, is spread out below the eye. Such a complete environment of snow-clad summits, along all the four quarters of the compass, is rarely or never to be seen elsewhere. The traveller will pursue his journey, in a prettily furnished barge on the Jhelum towed upstream, to Islamabad, where he will land in order to visit the famous Hindu ruins. Thence he will cross to the eastern end of the valley to the lovely fountain of Vernag, welling up from the base of the mountains and being the reputed source of the Jhelum.

The season will by this time be sufficiently advanced for him to leave the valley from this end by what is called the Bunnihal route across the Chenab river to Jammu.

From this Bunnihal route some distant views of the central snowy ranges will be obtained—several lines of snow at varying distances. Then the traveller begins to realise the breadth of the Himalaya. He is close, indeed, to snowy mountains, but they are only the lesser ranges—the outworks, as it were, of the central range. He descends to the river Chenab, which rolls along as a young giant through the mountains. He reascends to some lofty plateaux and descends again to Jammu, the capital of the kingdom—that is, of the native State of Jammu-Cashmere. This place is finely situated near a three-peaked hill, called by the natives the Triple-headed Goddess. Here is an opportunity of studying a Himalayan native Prince with his picturesque surroundings.

The traveller must now revert to the plains of the Punjab, skirting as near as he can the base of the mountains, and crossing the fine irrigation works of the Bari Doab canal, till he reaches Kot Kangra, a rock citadel and one of the most characteristic of the Himalayan hill-fortresses. Then he ascends the mountains, and reaches the valley of Dharmsala, a marvellous expanse of rice culture conducted with countless irrigation channels from the hill-streams around. This perfect garden is surrounded by forest-clad hills, above which rise the snowy peaks. Such a spectacle is almost unique, even in the Himalayas. The traveller must now again revert to the plains of the Panjab until he reaches the river Sutlej. There he takes the railway train to Umballa at the foot of the Simla hills.

Ascending the mountains by the Simla road, he soon reaches Kussowlee, some 6000 feet above sea-level. He looks back over the vast plain of the Sutlej basin which he has just quitted and which commands a wondrous prospect. The apparently limitless expanse of land looks like the ocean, the distant horizon melting into the sky. The curves of the winding Sutlej and its affluents form a fitting contrast to the horizontal lines of the landscape. This view of the plains, from a mountain rising aloft immediately over them, is most remarkable. Before quitting the Himalaya we shall find more views of this nature. They are certainly the most striking landscape scenes in India, and must be in the first rank among the views of this kind in the world.

Near Kussowlee is Dugshai, and both stations are occupied by European troops. The traveller will notice that these stations, in combination with Umballa, form a reserve of European strength for North-Western India.

By this time the month of May will be advancing and the season for Simla begun. The Viceroy and his Government, with some of the official classes, will have arrived and the world of Anglo-Indian fashion will have assembled. The traveller then may well halt here for awhile and contemplate this summer resort of the Government of India and its surroundings, including the army headquarters. Owing to the extension of railway facilities, the families of officers, military and civil, can easily betake themselves to the mountains, which are cool, while the plains have by this time become burning hot. Consequently Simla has now become bright with ladies, and the social gatherings on the green swards, underneath the rocks, overshadowed by the fir, the pine, the cedar, are of daily occurrence. The rich bloom of the rhododendrons lends gorgeousness to the scene. The place is like a gay Swiss city isolated on the mountain top—with dark ilex forests around it, blue hills beyond, the horizon being ever whitened by the snowy range. The town almost seeming to be suspended between heaven and earth! There are but few wheeled conveyances; when guests are bidden to balls and parties, the ladies go in Sedan chairs with gaily clad bearers and the gentlemen ride on hill ponies. But in this paradise, tempting the mind to banish care and forget affairs of State, the most arduous business is daily even hourly conducted. Red liveried messengers are running to and fro all the day and half the night. Tons of weight of letters and despatches come and go daily. Here are gathered up the threads of an Empire. Hence issue the orders affecting perhaps one-sixth of the human race. The traveller may pause for a time to observe in close juxtaposition all that is loveliest on the face of Nature and all that is most strenuous in the life of man. He should take a really good look at Simla in all its peculiarities, being well assured that there is no other place like it in the world.

Before the rains begin in the middle of June he should make at least one short excursion from Simla into the interior, and for this purpose must be prepared for some hard marching. The best of these is that to the summit of the Chôre Mountain, about 12,000 or 13,000 feet above sea-level. He should be awake and seated outside his little tent before dawn to watch the sun rising behind the snowy range and gradually gilding the famous peaks—like three gables and a cathedral tower—whose glaciers supply the sources of the sacred rivers, the Ganges and the Jamna. He may reflect on the millions of devout Hindu eyes which are turned towards these distant peaks from the plains far below with superstitious awe or with affectionate reverence.

When the rains of June shall have cooled the weather in the plains the traveller must descend from Simla to Umballa, and take the railway to a point near the base of the mountains of Naini Tal, the summer resort for the North-Western Provinces, and, as the name Tal implies, the leading feature is a lovely lake embosomed in the mountains. If the weather should permit he might make an excursion to the uplands of Almora, whence a magnificent array of snowy peaks is visible.

Thus the rainy reason passes and he must again seek the plains, which are now traversed by swollen rivers in full flood. He will travel by rail along the Behar lowlands to Northern Bengal, and so ascend the eastern Himalaya to Darjeeling, the queen of Himalayan beauty. He would thus reach it in the early autumn, when the veil and curtain of cloud masses and rolling vapours have been uplifted to display the peerless snows in all the gilding of Oriental sunshine. Looking upwards to the snows of Kinchinjunga and downwards to the valley depths, he takes in 26,000 feet of altitude (nearly double the height of Mont Blanc) in one sweep of the eye. Nowhere in the Himalayas will he find the foreground so rich as here—owing to the longitude as well as the latitude the vegetation is semi-tropical—the airy fairy tree-fern, and the flowering magnolia are in the front, while the everlasting snows are piercing the sky. If possible he should take two excursions, one to a neighbouring range, where he would find the largest rhododendrons yet known to botany, and in the distance Mount Everest, which, with Kinchinjanga, forms the loftiest pair of mountains yet discovered in the world, between 28,000 and 29,000 feet above sea level. His other excursion would be to the chain of beautiful lakes, from 13,000 to 14,000 feet above sea level, on the frontier of Sikkim, forming the boundary between India and Tibet.

He would then descend to the deltaic region of Bengal, as autumn is advancing apace, re-visit Calcutta, and take steamer to England.

But if he can give another fortnight, he might well pay a flying visit to Burma, see the Rangoon gilded pagoda shooting up like a flame of fire into the air, the banks of the Irawady, the teak wood-carving and the gilded finials of Prome forming one vast pyramid, the gigantic images of Booddha with his transcendental and sublime dignity, the panorama of Moulmein with three rivers flowing (two from the hills of Siam) into the bay of Martaban.

Or he might re-cross India by the Nagpore route to Bombay, thence proceed by sea to Kurrachi and the Lower Indus to Sukkur. Then he might by rail proceed to the British frontier adjoining South Afghanistan, visiting the Bolan Pass, and returning to Kurrachi, from which port he would embark for England.

The grand tour of the Indian Continent and the Himalayas, as sketched above, might take something over a year; but it is hard to imagine a more pleasant and profitable manner of spending twelve to fifteen months.

SIRINAGAR LAKE, CASHMERE

HILL STATION OF SIMLA

MOUNT EVEREST

MOUNT KINCHINJANGA

If the visitor to India desires sport he must give up his time to it, and be content with seeing what he can of the country while going to or returning from his hunting grounds. This, too, holds good whether his sojourn be in the winter or the summer, for the sports worth pursuing are very wild. Consequently, distances are great and access is difficult. So without weeks and weeks of time nothing can be done in this way.

In the Himalayan region the forest grounds are too steep and rocky to be occupied by man; and the forests, with their denizens, continue very much as they have always been. But the shrinkage of the forests in India proper, owing to the invasion of the plough, the retreat of wild animals before the advance of man, the consequent diminution of the wild sports, are matters of common fame. Even then, however, several mountain ranges in Central, Eastern and Western India defy agricultural invaders. The Government, too, have during this generation awaked to a sense of the value of their forests, and have brought a vast area, greater than that of the British Isles, under forest conservancy, constituting thereby a marked addition to the resources of the State. This, together with a further area still in private hands, makes up an enormous field for the sportsman. Such an area still abounds in animals, some flesh-eating and ferocious, others timid and feeding on herbage, the latter being the natural food of the other. Others, again, although living on fruit and vegetables, can be very fierce if attacked. Others, again, live on fish, and can under some circumstances be dangerous.

The forests in the Himalaya consist of cone-bearing trees, of cedar, pine, fir, such also as juniper, yew, cypress, all in magnificent abundance, of some trees well known in Europe like the oak, the ilex, the birch and the plane, of trees highly ornamental, such as the rhododendron, the magnolia, and the tree-fern. The forest in India proper consists of deciduous trees, many of which, though valuable and useful in every way, are not known in Europe. Some, however, are known, like the teak, the tamarind, the ebony and the bamboo. Where the bamboos grow in quantities together they form one of the most exquisitely beautiful portions of the vegetable kingdom. Flowery shrubs, almost as large as trees, are commonly found. Some trees, through insect life, afford fine red dyes. The tall grasses, too, rise with their hairy heads waving in the breeze. The aspect of the forest is never gloomy; though umbrageous enough, it is yet cheerful under the Indian sun, and almost invariably gladdens the heart of the beholder. The undergrowth, though sometimes dense, is seldom rank or noxious, except, of course, in the deltaic regions. Every one likes marching in the forest districts in most seasons, save in the autumn, when the malaria rises and when the sylvan beauty becomes treacherous. To him who listens at night or in any calm noon-day hour, the infinitude of sounds, loud or low, soft or shrill, is marvellous, when nought is visible of the creatures, feathered or four-footed, big or minute, who are living in the arms, the bosom, the lap of the jungle, as their voices betray their presence.

In regard to birds, there is not much of that game in the forest. Such sport is best to be found in the marshy lakes near the great rivers, and in the highly cultivated fields. The quail-shooting in the young corn-fields of Western India is not surpassed in any country. Over many a marsh and lake the sky is at times partially darkened by the circling flights of aquatic fowl.

The deer and antelope of many species, with their pointed or bending horns and their branching antlers, are pursued, with fatigue certainly, but without danger, just as they are stalked in the British Isles. So is the bison, though under certain circumstances at close quarters his horns may be dangerous. It is, however, the spice of danger that lends interest to the wild sports. The danger may arise from the nature of the localities; it generally arises from the character of the animals.

In the higher Himalaya the pursuit of the wild goat and the wild sheep is the most arduous. The sportsman at the best has but the scantiest reward for immense exertions, with all risks from precipice, crevice and glacier, in more than Alpine altitudes. If he fails in sport he still sees mountain scenery of the most exalted character better than any one else can see it, and he communes with Nature in her most sublime mood. In the lower Himalayas, including the submontane zone called the Terai, the game is much the same as that of India proper, but with somewhat greater risk in respect of malaria.

In India the lion is rare, and when found is of no account. The king of Indian beasts is the tiger, and of all the varieties of the race the Bengal tiger has the highest repute, probably because he is the best fed, being able to prey upon cattle. Often he lurks in sub-Himalayan jungles near the river Brahmaputra. Being, like most wild beasts, a capital swimmer, he will often swim across a broad river to some small wooded island as a hiding-place or a storehouse for the bodies of the cattle he has killed. He can be surrounded here without a chance of escape, and then he will show fearful fight at the very closest quarters. The sportsman, too, must attack him without the help of elephants. This is a very fine opportunity of tiger-shooting; but the sportsmen should be first-rate hands, otherwise disaster will occur.

The tiger elsewhere, who must spend an active night in stalking the fleet and wary antelope, has a precarious livelihood, and is leaner. He is a coward before man, and will fly from a human pursuer as long as there is any chance of safety in flight. When marching in the forest one first hears the deep roar of the tiger an instinctive fear arises. But in reality all is safe; he will not come near. He would never attack a man unless he were a man-eater, and if he were, then no roar or sound would issue from him; he would steal up noiselessly like death and the grave. A tap from his velvet paw on the head of the unsuspecting man would stun the victim; some blood would be sucked from the throat, the body would be lifted up by the powerful mouth, and carried to a lair where the ghastly meal might be completed later on. The man-eater is usually one who has failed in the ordinary business of a tiger. The regular tiger is a born sportsman. Consummate in the art of stealthily pursuing his game, he is equally skilful in eluding pursuit when he is himself pursued. Still he must have his lairs, and, above all, his drinking places in the dry heat, the solitary tarn, the attenuated streamlet. The pairs of human eyes that peer about in watchfulness are at length too much for even his sagacity, and the elephants with the marksmen are upon him. He receives bullet after bullet in his body without flinching and yet goes on. Finally he feels that he can carry no more bullets or that his strength is failing—as the bullets may be causing internal hæmorrhage—or that there is some barrier-like rock, or that enemies are hemming him in. Then he resolves to retreat no further. Now are seen the amazing flexibility and elasticity of his muscular system; with his mighty bound, his bright tawny side and dark stripes, he looks like a vision as he sweeps through the air. Then, too, it is that he puts all his force into that terrible spring with which his fame has long been celebrated—right for the nearest elephant. Confident in the rifle of his rider, the noble elephant gathers up his trunk and presents his broad forehead to the tiger, like a British square receiving cavalry. If the tiger is stopped by the bullet—well. If not, then in an instant the tiger, with teeth and jaw and claws of all four feet, fastens himself on the broad flank of the elephant. I shall not follow up the crisis which ensues, and which may end in disaster or may be averted in many possible ways.

The worst of all dangers is that which often arises when the stricken tiger lies low, apparently wounded unto death. The temptation is for the hunter to approach too near and thus to come within reach. Then the dying tiger summons up his last energies to wreak revenge on his destroyer. More wounds have been inflicted on sportsmen, more gallant lives have been lost, in this stage of tiger-hunting than in any other.

For all that, the tiger is not the most dangerous animal of the jungle. The palm in that grim respect must be awarded to the panther, a sort of leopard, grey with black spots, extremely light in body, relatively to the long muscular limbs, consequently having an agility unequalled by any creature whatever. He is pursued in much the same way as the tiger, but is more courageous and readier to resist. The spring of the tiger is that of blind fury and despair directed at the nearest object without any thought. But the panther has cunning thought in his spring, and he means vengeance on his assailant. Two sportsmen might be perched up on big branches of trees by moonlight, watching a panther come to drink. Both may fire and hit. Instantly the panther will climb up one tree with amazing quickness and punish the sportsman. He will then with equal velocity ascend the other tree and deal with the man up there. Lives of men have been lost in some such way as this. In no other case is such ferocity directed with a cunning almost amounting to reason.

The bear is the most stupid animal in the forest. But the character of the she-bear with whelps is different. Maternal instinct gives her for a while an aggressive fierceness to which bearish nature is usually a stranger. But when pushed to close conflict and smarting under agony of gunshot wounds, the bear will round on his enemy. He will grapple with the muzzle of the rifle, or if he can reach the man’s body then his gnawing bite is dreadful. Sometimes near a jungle path the bear lies quiet in the dusk though the wayfarer is approaching. In what may be figured as vacuity of mind, he lets the wayfarer stumble over him. Then he rises in surprise and with his long nails strikes at the man’s head. I have seen a man’s face scratched away—all features gone—with one stroke of the claw. The proper precaution at dusk is to sing or shout as one walks along; if there be any bear on the path he will, on hearing this, move off.

The queen sport of India is wild boar-spearing, commonly called pig-sticking. This is on horseback, and the boar often takes the hunt and the field over such a stiff country with so many blind ravines that accidents are reduced to a certainty. The Bengal boar, feeding on sugarcane illicitly consumed, is well fed and short tempered. After galloping for a bit at full speed his breath fails him, and he resolves to stop and fight. Elsewhere the boar, being less fed and in better running condition, goes further, and in some places he will give the field a long run just as a fox does in England. In all cases the mode of fighting is the same. The boar is wounded by spear after spear as the well-mounted riders come up with him. Then he suddenly stops and “squats,” as the phrase goes. That is to say he turns round, sits on his hindquarters and faces the horsemen with his mighty snout armed with the protruding tusks. The next step on either side may depend on various circumstances demanding all the qualities of the best sportsman; but anyhow there is a crisis. If the boar charges, he may be stopped by the horseman’s spear. If that fails, then the horse is probably lost, being ripped up by one twist or turn of the tusk. If the horseman, on rolling over, is caught by the boar, then he may be killed in the same way. But that is not likely, because the boar after ripping up the horse rushes on madly without waiting to deal with the horseman.

The killing of elephants as a high kind of sport is carried on in other countries more completely than in India. The object in India is to capture these valuable animals for service, rather than to kill them. In the central part of India I have known these fine creatures caught in this wise. A gigantic V is formed in the forest by rough palisades growing in strength and massiveness near the pointed end. The herd is driven by beaters into the broad end of the V, which operation is not difficult, as the breadth may be a mile or more. The herd moving before the beaters finds itself more and more confined at every step till the point of the V is reached, and its movements are fully circumscribed. Then comes the tussle for capture or escape, and the struggles can be imagined with which the huge beasts strive to effect their freedom, but in vain, as the ropes and the lassoes are too strong.

Though venomous snakes often destroy natives in the jungle, they rarely trouble Europeans. The hooded cobra, however, in South-Western India does appear menacingly at times. I do not remember any casualty occurring, but I have myself been more than once threatened by him.