* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks, Volume 2, Number 2

Date of first publication: 1866

Author: J. T. Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom

Date first posted: May 6, 2015

Date last updated: May 6, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20150516

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Paulina Chin & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. II. | FEBRUARY, 1866. | No. II. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

THE TALE OF TWO KNIGHTS WHO FOUGHT THE GIANT SHAM. II.

MAN went through the village one day driving a

load of posts. By and by he stopped and threw one

of them down by the roadside. A good lady saw

him from her window, and said to herself, “Why,

here is a kind-hearted man indeed! He is lightening

his load because he thinks it too heavy for his

horses.” Presently he threw off another post. “The

kindest-hearted man I ever saw!” soliloquized the

lady; but the small boys following him saw that he

kept lightening his load till it was quite gone, and

a line of white posts lay along the roadside as far

as they could see. “Mitter Anner, what all them

thticks for?” said inquisitive young Archie; but,

without waiting for a reply, he hurried off to new

wonders. Three other men came up with shovel

and scoop, and various tools, and they scooped out

deep holes, and set up the posts in them, and

marched on. One of these holes they left unfilled

over night, and when they were gone I went out

and looked down into the deep round cavity, and

there at the bottom sat merry, mischievous little

Puck, and winked up at me with his saucy bright

eyes.

MAN went through the village one day driving a

load of posts. By and by he stopped and threw one

of them down by the roadside. A good lady saw

him from her window, and said to herself, “Why,

here is a kind-hearted man indeed! He is lightening

his load because he thinks it too heavy for his

horses.” Presently he threw off another post. “The

kindest-hearted man I ever saw!” soliloquized the

lady; but the small boys following him saw that he

kept lightening his load till it was quite gone, and

a line of white posts lay along the roadside as far

as they could see. “Mitter Anner, what all them

thticks for?” said inquisitive young Archie; but,

without waiting for a reply, he hurried off to new

wonders. Three other men came up with shovel

and scoop, and various tools, and they scooped out

deep holes, and set up the posts in them, and

marched on. One of these holes they left unfilled

over night, and when they were gone I went out

and looked down into the deep round cavity, and

there at the bottom sat merry, mischievous little

Puck, and winked up at me with his saucy bright

eyes.

And who is Puck? O, a funny hobgoblin that promised three hundred years ago to put a girdle round about the earth in forty minutes, and who seems sometimes seriously to be setting himself to the task, and again, in sport, bringing it all to naught. Dr. Franklin and Professor Morse, and Monsieur DeSauty and Mr. Field, have put their shoulders vigorously to the wheel; but I fancy Puck is at the bottom of it all,—sweet Puck, who labors in the mill and thrashes out more corn at night than ten men do by day, yet, when the mood takes him, bobs about like a crab in the gossip’s bowl, or turns into a three-foot stool, and slips away when the “wisest aunt” goes to sit down on it.

Is the telegraph Puck’s work? Let us see, then, what it has done. The telegraph? Electricity? O yes! You know all about it. Not you, nor I, nor the wisest man living. As yet we have only felt out cautiously in the dark, and laid our hands upon the mane of this wonderful wild creature, this mysterious electric force, taming him down now and then to a feat of swiftness or of strength; but what his nature and his service are, how to gain the complete mastery over him, and what giant’s work he stands ready to do for us when once we shall have subdued and subsidized him,—ah! my little friends, this is your work, the bequest of the past generations. Therefore, young philosophers in posse, (that is, in pinafores,) study assiduously your a-b-abs, your three times two, and your τύπτω τύπτεις τύπτει, that you may be ready for great things when the fulness of time is come.

Permit me to remind you of what you perhaps already know, that the word telegraph is composed from two Greek words,—tele, afar, and grapho, to write; consequently anything which writes or signals from afar off may be called a telegraph. In the old times fires were used for this purpose. Kindled on the hill-tops, and flashing from hill to hill, their light by night and their smoke by day would speedily give warning across a whole country. It was thus that the Indians, dragging their old times down into our later days, heralded to their comrades the tidings of Fremont’s approach. The ancient Romans went so far as to spell out words by using different kinds of fires for letters. You may recollect that the colored lanterns used on railroads and steamers have each its significance.

Then people began to get acquainted with this strange servant of theirs,—ever present yet ever unseen,—this electric force. Long before Christ came, they had learned his signs and felt his power; but for thousands of years he eluded them, and they got little control over him. It was only after long study and many trials that they found a way to send him of errands over long distances. Dr. Franklin made a road of wire, laid it under the Schuylkill River, and ordered him to set fire to some alcohol on the other side. Then that learned man cast longing eyes into the heavens, and little Puck mounted a kite, sailed up into the thunder-clouds, stole a pocketful of lightning, and brought it down to the Doctor with a smart rap over the knuckles for his pains; but little heeded the Doctor, so he could prove that the electricity of the earth was own brother to the lightning of the skies. From that time Wise Men of the East and West labored incessantly to tame down the fierce, fearful creature into a meek domestic drudge, and got many a kick for their pains, but curbed him ever more and more; and all the while Puck helped and hindered to the top of his bent, and made sport alike of work and play. When the wise men succeeded in communicating signals from room to room, they thought they had accomplished much. Then they arranged lines and spaces on strips of tinfoil, and, having exploded a charge of gunpowder, or caused to fall some solid body, to let you know something was going to happen, they flashed out the electric light, and the form of the figure shone confessed. The first telegraph actually established was by Professor Steinheil of Munich, in 1836. It was twelve miles long. It rang bells for signals, and then traced dots and lines upon a strip of paper, moving slowly and regularly under the instrument. These dots and lines represented letters, and the operator would translate them into the words intended; as,—

— - - - - - - - - - boy.

But mischievous Puck found here a fair field for his pranks, and played all manner of tricks with these signs, turning sober sense into—sometimes very serious—nonsense; as when the merchant telegraphed to have a certain bill of exchange “protected,” Puck altered it into “protested,”—which is a pretty solemn and very different thing among merchants. At length, to thwart the tricksy hobgoblin, operators gave up their signs, and trusted to their ears alone to tell them whether the marks were intended for dot or dash.

But presently down came a man from Vermont,—the green and beautiful State where they have no Democrats and the jails are empty,—Royal House by name, and of most royal house indeed, and Puck feared in his impish soul that it was all over with him. For this Royal House set up a crank and a wheel and a key-board, and placed strips of blackened ribbon above the white paper strips, and when a message is to be sent, you give the signal, strike the key-board as you would play a piano, and for every stroke up jumps a little type, a hundred or a thousand miles away, presses the blackened ribbon against the white paper, and leaves there its image,—a plain Roman letter! Click, click, click,—there is your message all ready, in good honest type, printed by the lightning’s own hand, to be known and read of all men. Puck looked on in dismay when the first printed message was sent over the wires, in 1847, from Cincinnati to Jeffersonville, one hundred and fifty miles, and feared his occupation was gone. Quite machineried out of the way, what could little Puck do? There was no room between fingers and key-board to crowd in a spice of mischief, and when the man at the receiving-station heard the click which told him a message was coming, he had only to set his type-wheel, put the machine in motion, signal back that he was ready, and go to reading his newspaper,—leaving the lightning’s swift fingers to do all the rest; and the lightning would make short work with Puck, as that elf very well knows. So he is forced to content himself with stealing a march upon the operators, and giving them a saucy slap now and then.

But though within the telegraph rooms Puck is somewhat checkmated now-a-days, he finds ample room and verge enough out-doors to frolic in. After he has assiduously helped to set the telegraph posts and stretch the wire, he labors just as assiduously to bring them both to grief. Did you never see him sitting astride a post in a storm, grinning maliciously as he succeeded in twisting off the wire or pulling it apart with both hands, his fat cheeks all red and puffed out with the effort? In the old country they sometimes hide the wires in lead or earthen pipes, and stow them underground, out of Puck’s sight; but he prowls around till he finds their hiding-place, and it shall go hard but he will tap them somewhere and let off the precious electricity, or give them a thrust with his foot and sink them into uselessness. Then the poor workmen have to crawl around a great while longer to find where the trouble is, and Puck lurks under a plantain-leaf and flings up his heels in agonies of delight. In fact, the telegraph companies are so sure of his funny spite that they employ men regularly to follow him up. Where he has broken a wire, they mend it by soldering the ends together; and they have become so expert, that, by putting one end of the broken wire above the tongue, and the other end beneath it, some of them can find out what is the message that is passing through it. During the last war, when news sometimes made fortunes, certain men, more curious than honorable, are said to have fastened a small wire to the main one, and to have coaxed away from it electricity enough to whisper, faintly but intelligibly, its secret errand. But we will not believe any one would be mean enough to do that. It would be like opening and reading another person’s letter.

In 1852 Dr. Channing, Mr. Farmer, and Puck laid their heads together, and set electricity to ringing the fire-bells of Boston. And ring they did, so loud, so clear, so true, that they told all the firemen not only that there was a fire, but just in what place it was, so that there need be no time lost in running hither and thither. These bells were once rung from Portland through the telegraph wire, “just for fun,” and they were all ready to be rung from London through the great Atlantic cable, when it suddenly ceased working. Only think, little friends, of standing in London and ringing the Old South bell in Boston!—being called to dinner, say, by the Queen of England, God bless her! the true-hearted woman, who was our friend when friends were few.

The great Atlantic cable,—ah! Puck has made wild work there. When after infinite trouble it had been safely bestowed on shipboard and taken out to mid-ocean, did not he raise such a storm about their ears as came near sending ship, sailors, and all to the bottom? And after helping Mr. Field to get it well a-going, after setting the Queen at one end and the President at the other for a social chit-chat across the world, after persuading New York to burn her City Hall by way of fire-works in celebration of the event, and driving us all crazy with delight, he must needs turn about and belabor the poor cable till its breath grew shorter and shorter, its voice came fainter and fainter, and it died and gave no sign.

So it slumbered in its ocean bed for four years undisturbed, and then Mr. Field prepared another cable, still stronger and better than the first, and they placed it on board the Great Eastern,—the unhappy, blundering giant, who felt now that at last his hour was come,—and sailed out to sea, uncoiling as they sailed. And the astonished sea heaved and surged around the slender wire, but took it softly to its great, cold heart,—the strange, wee thing, the flashing, throbbing, living soul that was henceforth to voice the harmony of the world, the brotherhood of man. O Puck, Puck! two continents were agaze. Could you not cease your mad pranks for one little space? Not Puck! The more eager we grew, the wilder and madder waxed he. The nearer we came to our goal, the more intent he to push it from us. He stabbed the precious wire with wicked darts. He climbed into the tank where it lay, and kinked it into knots, and tangled and rasped and strained and grated it,—and—and Mr. Field went down into the cabin, and with white lips,—white from feeling, not faint-heartedness,—and with a voice that trembled, but only as a brave man’s may, he told them it was all over. The cable was broken and gone down into the deep sea. O, I think even little Puck must have been sorry then!

Whether Puck will ever give us the girdle he promised, I do not know. I think we shall one day, perhaps not yours nor mine, get it in spite of him. But this is certain: fail the cable if it must, there is a strong heart that has never failed. And better than a hundred cables is the heroic soul which braves every storm, and bides every strain, and holds, through all, its unchanging purpose and its unfaltering course. We have not yet our ocean telegraph, but we have our Mr. Field.

Gail Hamilton.

YOU have seen the little chalets, or models of Swiss cottages, perhaps, which some of your friends have brought home with them from Europe. They have staircases running down the outside, and plenty of cosey nooks where children can perch, like birds on the tiny houses we sometimes build for them, and can glance like them over the world, singing perhaps as gladly in the sunshine.

Several of these Swiss cottages are built near together on a certain mountain-side. One of them, at a little distance from the others, directly fronts another peak of the Alps, whose snow-crowned summit, bare in the sunshine, with spots of verdure lower down, where its rays fall more kindly, looks like the hoary-headed grandfather of the Alpine chain, whose broad green scarf of pasture-land is twined round him even to his feet.

Pieretto Lamer was born in this cottage, and for ten years had lived in it. He slept in a room whose pointed window just took in a view of the Alpine peak, and for five years this room had been shared with his little brother Carl. They used to lie awake here on moonlight nights and watch, with a kind of wonder and fear, the great mountain, so still and grand. Pieretto could only think of God when he looked at it; for it was above the earth, powerful and yet beautiful, and it sent down its pure water, and clasped its protecting forest arms around the dwellers on it, as God’s love enfolds all who live on earth. So he said his prayers to it every night, and could never quite forget its presence.

Carl was a noisy, rough little fellow. He liked to look at the mountain, and tell Pieretto and his mother how he meant to have his chalet built upon it when he grew to be a man; then he would pasture sheep, his wife would make cheese, and he would go off whole days, scaling the mountain passes, and come home, his hat trimmed with Alpine roses, to surprise them all with the chamois he had shot. His gentle mother, who was sick a great deal, only smiled sadly at Carl and his plans; but his old grandfather would frequently tell him about little boys who had grown up to do a great deal to make their friends happy, encouraging all his dreams, and even adding to them some which Carl was obliged to declare could never take place.

Pieretto never said what he should do when he became a man; perhaps his boy-life was too busy for him to think much of what was beyond it; perhaps he noticed that his mother looked sad when Carl talked of his mountain life; for the little boys’ father had been such a bold mountaineer as Carl longed to be, and had been killed in one of the perilous passes, leaving his wife and old father to support themselves and the two boys.

The sun shining in Pieretto’s eyes early in the morning always waked him; then he would dress quietly, that Carl might sleep longer and not disturb his mother in the next room, and creep softly down stairs to feed the goat and pigs his grandfather owned. There were many things he found to do in the mornings, but in the afternoon, if his mother was well, he went out with Carl to play, or carried him down to the base of the mountain, where Pastor Josephen Meagher lived in the chalet next the church.

On one of these play afternoons in winter, Carl, being tired of the games of running and jumping with which Pieretto had so many times amused him, sat down on the lower step of the staircase, saying discontentedly, “If I only had playthings now like Louis and Adelia Meagher, I’d rather stay indoors than out this freezing afternoon. Why doesn’t the Christ-child bring as nice things to us as to them, Pierro?”

“Didn’t you have a chalet on the Christmas-tree last year?” asked Pieretto good-naturedly. “I don’t want any nicer playthings than I find out of doors. I guess the Christ-child himself had no others, for you know they tell us in Sunday school that his father and mother were poor.”

“But God was his Father!” cried Carl, with great round eyes of surprise.

“Yes, and God is our Father; so all the playthings he makes belong to us.”

“God make playthings! I’m sure I don’t know what you mean, Pierro, and I think you’re saying real wicked things!” said Carl.

“Wicked things? no indeed. Who makes the stones we build our castles of, and the little rivers we sail our ships on?” asked Pieretto. “And besides, there’s a real ice palace up in the glen, prettier than any toy Louis has.”

“O, is there really, Pierro? Show it to me, Pierro!” cried Carl, jumping up and catching hold of Pieretto’s hand.

“A run up the mountain will do you good, after sitting so still in the cold,” returned Pieretto gravely. “So come on.”

Both boys were too much excited, Carl with curiosity, and Pieretto with the pride and pleasure of gratifying it, to continue their talk. So they ran, stopped a moment for breath, then ran on again, that they might, as Pieretto said, reach the ice palace two hours before sunset.

They reached the glen, which was almost enclosed by fir-trees, and where the snow and ice began to form, and tossed itself in wilder and wilder shapes, until on the summit it seemed at a distance like a part of the soft, fleecy clouds which so often hung in the air around it.

There in the glen were the tiny rivers and waterfalls which amused the boys so much in summer. Now they were still and cold,—as different from themselves when Carl had last seen them, as the bright, playful child differs from the little body still and cold when God has taken the spirit to himself.

Carl must have thought so too, for he exclaimed as soon as he saw them, “O, they are dead, Pierro! all our beautiful rivers and waterfalls are dead.”

“No more dead than you when you are asleep, and can’t talk,” laughed Pieretto. “Winter is night for the flowers and brooks; but I know how to wake them up and show you the fairies of the ice palace.”

Pieretto’s eye sparkled with conscious power, and his cheek was unusually flushed, while Carl jumped about crying, “Do, Pierro, O please do!”

“Well, throw yourself down here on the ice-palace. Do you see its spires and turrets, and all the queer shapes we find on our window-panes cold mornings?”

“Yes, I see,” whispered Carl.

“Jack! Jacko!” cried Pieretto, putting his mouth close to the ice.

His warm breath melted the doorway, and Carl stooped down to look in. There was a room looking as if made of glass, but really a crystal palace of pure shining ice, with icicles hanging from its roof, and delicate tracery of frost-work frescoing its walls. This room was filled with fairies about as large as your thumb, pure and white as snow-flakes, and dancing about as those fall in a snow-storm; others, of a more dazzling transparency and a more elfish look, were spirits of the hail-shower. Only one, the largest of all, had a touch of color about his face, which seemed to be made of a juniper-berry and covered with a white frost. He had two shining black eyes, and was clothed in ermine, with sparkling diamond ornaments of frozen water-drops. He was a jolly little frost-king, and had a tiny icicle in one hand, which he held as a sceptre, or used, as we shall see, as a brush or pencil.

The fairies danced more slowly, and began to droop even while Pieretto and Carl were looking at them; and Jack Frost seeing it, and feeling badly himself, turned to see what was the cause. When he caught sight of Pieretto and Carl at the doorway, he exclaimed, “No wonder you feel so faint, my little elves; the hot air is pouring in upon us from a fiery furnace outside. Look here, my giant friends,” he added, turning to the boys, “if you want to see how we live, you mustn’t hold your mouths open with astonishment. Your warm breath is as unpleasant to us as this would be to you.” With that the mischievous king jumped quite unexpectedly on Carl’s nose, and gave it such a nip that it ached with the cold. “Don’t cry,” said the king in a cheery voice, the laughs falling from him like water-drops from a cascade. “I only wanted to let you see what I could do, but I am ready to be as polite as you wish. After sundown I will show you how I pass the nights; it is too hot for me to venture out now. My children here will go soon,—one more dance first”;—and seizing castanets of ice, he played a tinkling melody, to which the fairies flew round again.

Then the boys noticed that, though the faces of the fairies were white, their dresses were often of the most brilliant colors,—rose and violet and blue; they shaded all colors of the rainbow, and as they whirled in and out amid the mazes of the dance, they formed figures like those of the kaleidoscope.

“You see that sheet of ice before you?” said Jack Frost. The boys looked, and noticed as he spoke the various colors of the different parts of it. “Well, when you want to see any of these fairies,” continued King John, as his subjects respectfully called him, “just breathe gently over the roofs of their tiny houses. There in a corner, amid firs and sprays of delicate fern, shrouded in ice, lives Violet Water; and by the rock is the Waterfall Fairy, whom you play with in summer without knowing her. One day last autumn the Brook Fairy, who is a sturdy fellow, and goes babbling over all the stones out to the sea, asked her to marry him. Sumachs and other shrubs blushed at the very idea, but they peeped over the mossy brink to see her fall into his arms for all that. Didn’t we have a gay wedding? Come, children,” he called to the fairies, “be away for the night. We’ll have many a merry meeting before spring, and then be off to the higher mountain. Be sure and hold those purple-belled Alpine flowers down tight, or some of these warm noons they’ll pop their heads up out of the snow, and then you’ll find your ice-palace won’t stand long.”

Then the fairies—Violet Water and Waterfall, Icy Blue and Rosedrop, with many, many more—knelt in a circle around their king, who kissed them rather coldly, as was his nature. Then they sprang up, and, forming a procession, turned to go through a long avenue, which led beneath its ice roof down the mountain, singing as they went to the clink of their tiny icicles,—

“You boys should be the friends always

Of the snow-elves and icy fays.

We build the shining roof of glass,

O’er which your clumsy feet may pass.

And when you skate, snow-ball, or slide,

Upon the field or mountain-side,

The fun you have you surely owe

To icy fays and elves of snow.

We hold the flowers to the earth,

For the warm sun which gave them birth

Would be our death; but we too show

The azure and the roseate glow.

Their colors, stolen by our Frost-King,

On human beings he may fling,—

Give the cold hands a touch of blue,

Or pinch your cheeks to redder hue.

But when the spring-time comes again,

And the bright sunshine floods the plain,

Then fays of ice and snowy elves

To higher Alps betake themselves.”

At these last words the fairies, with a merry glance and bow, shot suddenly farther into the silver aisle, and Carl clapped his hands with delight when he saw its diamond ceiling, through which at night the cold gleam of the stars sent flashes of light. It had columns of shining ice, and on these, in place of gas-fixtures, were opals, whose mild and changing color gave a strange beauty to the scene. The Alpine blossoms too, which they chained down by threads of ice fine as spun glass, showed their bright colors here, and Alpine roses blushed a tender bride-like pink beneath their snowy veils.

The boys would have gazed here for hours; but the king began to work busily, building a solid wall against the opening; then, stooping down, he clasped some skates of ice upon his feet, and, bidding them follow, glided swiftly over the frozen stream, which fell almost down to the pasture-land where their mother’s chalet stood. As he skated, he stopped occasionally to touch the shrubs along the brink—juniper and bilberry and rhododendron, still fresh in sheltered spots—with his ice-pencil, robbing them of every faint trace of green living color,—they turned brown and withered at each touch.

It was still an hour before sunset, but the light was dim among the giant shadows of the Alps, for dark gray clouds covered the sky. It was very cold too, or Jack Frost would not have ventured away from his ice palace so early. He stopped at the chalet with his young friends, who watched him, especially Carl, with amazement, as, climbing like a squirrel up to the sitting-room window, he pulled a seat of ice from beneath his fir mantle, and, fastening it on the sash, began to draw one of those pictures you see on the pane every cold morning. There were mountains, and pine forests, and deep ravines, such as he was familiar with in his Alpine home. He would perhaps have pencilled every window in the house, but a sudden gleam of sunlight fell on him, and, slipping from his seat to the ground like a tiny avalanche, he complained of feeling tired, and lay down to rest.

You can’t tell how funny he looked with his pointed icicle hat and white fur coat! So the boys thought, and ran into the house to call their mother and grandfather to see him; but when they came back, the sun was out more warmly still, and on the spot where he had lain, it shone upon a small pool of water, which never dried up, but became the source of a mountain rivulet, running down to the parsonage, and making the boys think, when the grass bordered it in summer, of their tiny friend, who had dropped his silver belt, and vanished up the mountain at the approach of sunshine.

“Our Frost-King is gone,” cried Carl. “O Pierro, I do believe he was nothing but an icicle after all!” he added, discontentedly.

“Well, well, don’t feel so badly my boy,” said Pastor Meagher, who had come to take tea at the cottage, and stood beside them now. “I have brought a knife for Pieretto, and mean to teach him how to carve the Swiss chalets. You can have some toys then, and he can sell many besides to travellers who pass this way.”

Pieretto looked up and smiled joyfully at his mother; then turned to thank the Pastor; and never, after he learned the art of carving, did his mother or grandfather want any comfort for sickness or old age.

Mary L. Smith.

FROM the bottom of my heart, my dear young readers, I wish you all the pleasures of this holiday season; and in the hope of adding something to your amusement I offer you this Lesson, for the first part of which I will choose—

This trick, which bears the name of its inventor, is as follows. A large glass vessel, shaped like a mammoth goblet, is brought forward and handed to the audience for examination. It is then filled with bran from a box on the stage, by placing it in the box, which hides it for the moment from view. It is then covered with a brass cap, which reaches only to the leg or stand of it, so that the audience may see that the bran does not pass through the leg. A small box, perfectly empty, is now shown, which is next closed, and at the word of command the bran changes its place; for on removing the cap, the goblet is found empty, while the box, which but a moment before contained nothing, is filled with bran.

Have a round pasteboard box made, shaped like the upper part of a goblet, and of such size as will admit of its just slipping inside the goblet you use for the trick. On each side of the top of this box, just at the edge, have two stout wires fastened, which must be bent so as to come over the edge of the goblet when the box is inside it. Now cover the outside of the box with strong glue or paste; and before it dries sprinkle it over with bran, taking care to leave no part uncovered.

When about to show the trick, secretly place the pasteboard box in the box containing the bran. Now fill your goblet; hold it up high, and pour the bran back into the box; repeat this several times, and at last, when pretending to fill it, slip the pasteboard box, mouth downward, into the goblet; cover the bottom of the box with some loose bran, and bring the goblet forward. Shake off some of the loose bran, and your audience will suppose the goblet to be full. On the inside of the brass cap are two grooves, extending the whole length of the cap and terminating each in a hole, just large enough to admit the wires which are fastened to the top of the pasteboard box. When the cap is placed over the goblet, care is taken that those wires fit in the grooves; the cap is now pushed down, and when it fairly covers the goblet the wires will be at the end of the grooves and push through the holes. All that is to be done now is to raise the cap, and the pasteboard box comes out with it, leaving the goblet empty.

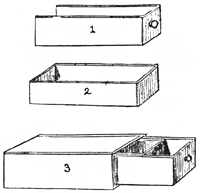

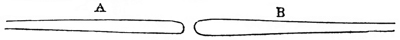

The box, which is shown empty, and afterwards found filled with bran, it is very difficult clearly to describe. As it is absolutely necessary, however, for the proper performance of conjuring tricks, to have a box which can be empty or full at pleasure, and as this one is the most simple known and a great favorite in “the profession,” I will try to explain it. It is called “the drawer-box,” from its shape, which is that of a drawer, and is made of three parts. No. 1 consists of a box having two sides, a bottom, and one end, the other end being wanting. No. 2, which is just enough smaller than No. 1 to fit into it, has two sides, a bottom, and two ends; and No. 3, which is the cover of the drawer, and large enough to admit of No. 1 sliding into it, is composed of two sides, a top and bottom, and one end. Now if No. 2 is laid in No. 1 they will look like one box, the end of No. 1, which is wanting, not being missed, because one end of No. 2 fills its place. When about to use the box fill No. 2 with bran, place it inside No. 1, and put both in No. 3. Now if you pull out No. 1 only (No. 2 being held inside No. 3 by a pin which runs through the bottom of No. 3 into the end of No. 2), the box will appear to be empty. Push back No. 1 in its place, withdraw the pin from the bottom of No. 3, pull out Nos. 1 and 2 together, and the box is full. Although this description may not appear very clear, yet I think any joiner could make a good working-box by following these directions; the annexed drawings, however, may tend to make it plainer.

I have described how this trick is done merely to satisfy the curiosity of some of my readers; but as I am averse to their spending money for apparatus which would be useless except just for the purpose it was made to serve, I will now explain a simple and inexpensive method of performing almost the same trick, in a manner better suited for private exhibitions than the preceding, and which is equally brilliant.

Take an ordinary goblet, and then with some thin pasteboard—brown bonnet-board is best—make a lining for the glass; that is, cut the pasteboard to such a shape and size that it will just go completely round the inside of the goblet, and then sew the edges together. There is now a cylinder formed; at the top of this cylinder sew a cover or top; next cover the outside and top of this with paste, and before it dries sprinkle bran all over it. Now cut two pieces of cloth each in the shape of an isosceles triangle; sew them together at the edges, leaving the smallest side of the triangles open, thus forming a bag; along the edges that are open sew two pieces of steel spring, or a couple of pieces of thin whalebone. If now you place in the bag as much bran as will go in the goblet, and hold it mouth down, the bran will not fall out, because the whalebones prevent the bag opening; but if you press on each end of the two whalebones, the bag will open and the bran run out.

To perform the trick then, put in your bag just enough bran to fill the goblet, and fasten it (the bag) inside the breast of your coat, by means of a pin, bent so as to form a hook. The audience having examined your goblet and satisfied themselves that it is without preparation, you proceed to fill it from a large box holding bran, and in which is concealed the lining. Proceed in every way as described in the trick with the large goblet.

After having slipped the lining in, cover the goblet with a large silk handkerchief, and give it to some one to hold. Now borrow a second handkerchief, and show it to be empty; hold it in front of your breast whilst you are showing it, and then passing one hand between it and your person, take out the bran-bag from under your coat and put it inside the handkerchief. Now approach the person who holds the glass, bid the bran “Begone!” raise the handkerchief, and with it the lining of the glass, and there is the empty goblet; pick up the handkerchief in which the bran-bag is, and, holding it over the goblet, open the mouth of the bag by pressing the end of the springs, and the bran running out will appear to come from what your audience suppose is an empty handkerchief.

The lining of the goblet may more easily be lifted out if you have a thread attached to each side of the lining, and made long enough to hang over the sides of the goblet; when you take hold of the handkerchief to pull it off, you seize these threads, and so lift out the lining.

There is a very old trick, which used formerly to appear on programmes as “The Fairy-Necklace,” that has lately come out in a new shape, and probably but few of those who saw it under its old form recognize it in—

The first I heard of this trick in its present form was at a show-shop in the rather disreputable precincts of Chatham Street, New York; since then, however, an air of respectability has been added to it by its exhibition in Broadway.

Two ropes, each about three yards in length, are given to the audience to examine; and having been found perfect, the performer passes them through the sleeves of a coat, in such a way as to suspend it; to make it still more secure, a knot is tied in the ropes, the ends of which are then given to two persons to hold. The performer then places his hand inside the coat, and, requesting those who are holding the ends of the rope to pull, the coat is left in his hands, having in the most mysterious manner worked off the ropes.

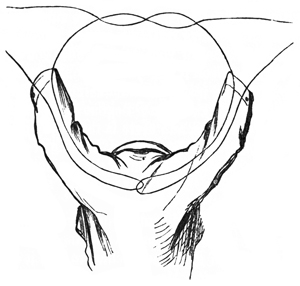

The whole secret of this trick rests in the arrangement of the ropes, which are of themselves perfect. After they have been examined, the performer proceeds to measure them; and, while working over them, doubles each rope in two,—that is, he brings the two ends of each together; he then slips a small rubber band over the centre of one, and then places the middle of the other alongside it and under the elastic, in this way tying the two together, as shown in this illustration.

He now passes the ends marked A, which are the two ends of the same rope, through one sleeve of the coat, and the ends B through the other; these ends he gives to two persons to hold. If now he takes off the elastic band, and the holders of the ropes pull, of course the coat falls off. The only difficulty about the matter in this arrangement is, that each person would have the two ends of one rope, instead of having an end of each in his hands; to remedy this, the performer, under pretence of making the trick more difficult, takes an end from each of them, before pulling off the coat, and, tying a simple single bow in it, thus returns to them different ends. To make it still clearer, I append another illustration, showing the position of the ropes with the coat on.

Some few years ago one of the “Spiritual” brethren exhibited in New York a violin, which played of itself, untouched by human hands, when placed in a box out of sight of, and at a little distance from, the audience. It seems rather strange that the “spirits” invariably keep out of sight, and that all the so-called “manifestations” require either a dark room, a closet, or a veil of some kind. The violin of course was played by “spirit hands,”—at least so the exhibitor claimed. Unfortunately, however, for the “medium,” his place was visited one night by a party of “roughs,”—a class peculiar to New York, I believe,—and they, being rather sceptical on some questions,—“spiritual manifestations” amongst others,—determined to investigate the subject. The result of this was, that they succeeded in discovering the “spirit” in the person of a German violinist, who, being stationed in a room directly beneath that in which the exhibition took place, furnished by means of a second violin the music which seemed to come from the instrument in the box.

The following little trick, although similar in effect to the above, depends neither upon the “spirits” nor any other confederacy for its accomplishment, but is purely a sleight-of-hand, I was about to say; but as it is not strictly that, I will proceed to explain it, without further digression, and my readers will then see for themselves what it is.

A jews-harp is placed at the mouth, and played for a while by the finger in the ordinary way. Gradually, however, the performer moves his finger away, and, beating time with it, the instrument, strange to say, continues to play in the most marvellous manner. To preclude all possibility of there being a thread in any way connecting the finger and the tongue of the harp, the audience are requested to notice that the performer can pass his “magic wand” about in every direction.

In order to perform this trick, get a jews-harp with a very flexible tongue, and cover the tip of it with a bit of sealing-wax. When you wish to play upon the instrument, place it so that the tongue of it is inside your mouth. Now, if you place the tip of your tongue against the tip of the tongue of the harp, and, pushing both out together, suddenly pull your tongue back, you will find that the jews-harp will twang in the same way as if you had pulled it out with your finger. By a little practice, you will soon be able to “play tunes” as readily in this way as in the old-fashioned method.

Of course, when you begin to show the trick, you put the forefinger of the right hand to the mouth, and move it as if playing in the usual way, and by this little ruse you persuade the audience that the tongue of the instrument is outside the mouth.

There is no telling the advantage one possesses who understands this trick; it is far superior, for parties camping out, to the old-fashioned method of producing fire by rubbing two sticks together; for although I have often read and heard of this, I never yet saw it done, although I have often seen it tried. By the method I am about to describe, however, all that is necessary is to fill the mouth with raw cotton, and then, taking a fan in the hand, proceed to blow up the fire. If you have gone to work properly, your efforts will soon be rewarded by a stream of smoke, which will be seen curling from your mouth,—

“Blue cloudlets circling to the dome,

Imprisoned skies escaping to their home.”

This will be soon followed by sharp, bright sparks, succeeded at last by a bright flame. Many suppose this to be an optical illusion, but it is nothing of the sort; it is a genuine live flame, and is produced in this way.

Get from some German chemist a piece of Amadou, or German tinder. This is a brown, velvety-looking substance, and you may purchase enough for a dime to last a lifetime. Tear off a small piece of this—say about as large as your thumb-nail—and light one edge of it; wrap this piece in some loose cotton, and lay it along with more cotton in your hand. You are now ready to perform the trick. When you come before the audience take the cotton which conceals the lighted tinder, and place it in your mouth,—there is no danger of its burning you,—then put some more loose cotton on top of it, and begin to breathe outward. This will light up the tinder, and the smoke will come; continue to breathe outward, or rather blow, and the sparks will next appear, and soon the flame. There will be a slight sensation of warmth now felt, but if you immediately put more cotton in your mouth it will subdue the flame. So you keep on blowing, and putting in fresh cotton, taking advantage at times, when your hand is at your mouth, of the opportunity for letting some of the half-chewed burnt cotton slip out. To finish the trick, get some narrow ribbon of different colors, about ten or twelve yards in all, and roll it up closely, so as to make a wad that will go in the mouth easily; wrap this in some cotton, which you keep under your thumb, taking care that you do not get it mixed with the rest. When you have blown out enough smoke and flame, pick up the cotton which covers the ribbons, and, clapping it in your mouth, drop that which is already there into your hand; give it a good hard blow, so as to disengage the end of the ribbon, which you then take hold of with your fingers, and proceed to draw forth yard upon yard of ribbon, to the amazement of the spectators.

P. H. C.

THEY are the ghosts of flowers,

The blossoms of fairer hours,

I see on the window pane!

They died in woodland and heather,

But lo! in this wintry weather,

Their petals unfold again.

O rare and wonderful flowers

That bloom in these crystal bowers!

How their splendors glance and gleam!

How they glow where the silver sedge

Fringes the rivulet’s edge,

And flush in the morning’s beam!

Arbutus and Eglantine;

The bell of the Columbine,

Poised on its stately stem;

Aster and Fleur-de-lis;

Wind-kissed Anemone,

And the Star of Bethlehem!

These, and a numberless train,

I trace on the frosty pane;—

Are they pictures of the brain?

Ah no! they are exquisite flowers,

The phantoms of sunnier hours,

That blossom in beauty again.

Albert Laighton.

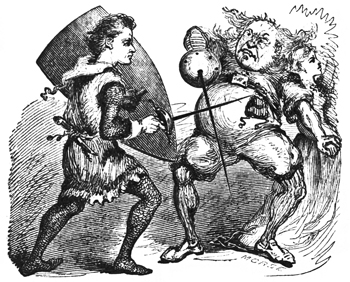

NOW the giant Sham was an evil genius of great power, who, by his unholy spells, brought worshippers and parasites to his castle from all quarters of the land. Most of these were weak-minded people, who preferred being servants to Sham to making their living in any more honorable way. They swaggered tremendously in the false jewels and tinsel trinkets so lavishly bestowed upon them by Sham, who did a large business in hiring out feathers for them to stick in their caps. And a sorrowful show these poor creatures made with their draggled and borrowed plumes! It was to attack this giant, in his castle, that the two knights had ridden forth on this fine summer morning, attended by their faithful squires. Brave warriors! thus to beard in his very den a monster who had thousands of dangerous fools at his back!

On, on, they wound their way through the crooked lanes that led to the rock, turning often their observant eyes, as they went, upon the strange groups that thronged and hustled each other on their way thither. “Look!” cried Sir William, “here come the Four Georges, I declare! Make way for the royal dolls!” And, as he spoke, four shadowy kings went by, all in a row, with jewelled sceptres and crowns, their footsteps sounding hollowly upon the crust as they walked. Stately ghosts they seemed to be while yet distant; but as they came nearer and nearer, much about them looked like mere tinsel and paste. At a sign from Sir William, Stylus whipped off the heads of these royal shadows, one by one, as they passed, and, lo! they were nothing but pasteboard, light and hollow, and easily put off and on. And yet these kings had reigned from generation to generation, bepraised by flatterers, and performing the functions proper to the kings of earth, and hardly one of their subjects but thought they were of real stuff. Indeed, one of these Georges—the Fourth he was called—passed himself off as a phœnix of kings and a model for all gentlemen to follow. “Royal old mummy,” said Sir William, addressing this fat personage, “I don’t like to see you dressed up in the livery of the giant Sham. It doesn’t become you at all. The first gentleman in all the land, as you please to call yourself, needn’t make himself up to look like a stuffed peacock. It isn’t necessary, and it is very aggravating to the well-regulated mind. Come, then, strip off your borrowed livery, and stand forth to the world for what you are.” But when Stylus began to strip the clothes off the royal old mummy, the padding and pasteboard of which that personage was made all gave way, and came tumbling to the ground, and behold! in the place where the heart should have been there was nothing but a great iron of the kind called a tailor’s goose, which Stylus hung as a trophy to the housings of Sir William’s horse. And now that was all that was left of the four kings, who faded away out of sight. But the two knights went toiling, toiling up the steep ravines, for still the word with them was “Onward, march!”

And while they are wending their way, let us take a peep at the giant Sham, as he receives his followers in his castle on the top of the hollow rock. There on his hollow throne he sits, a shapeless, unwieldy mass, and of aspect so stupid, indeed, that it is absolutely wonderful how he could ever have been set up for an idol in the high places of the land. To his feet there come, in throngs, the people who have been crowding up the crooked by-ways and thorny lanes that lead to the castle, and they kneel to him, and worship him, and are glad when they can touch the hem of his garment, and go off into fits of delight if they only get a chance to kiss the latchets of his shoes. There is a sound of outlandish music in the great galleries, and the people clap their hands at it, and cry, “Bravo!” a hundred times, though they do not in the least like it or understand what it means; and there is great bowing and scraping among the promenaders in the halls of Sham, men and women shaking hands with one another with all their might, and hating one another with all their hearts. The guards that sentinel the corridors of Sham are warriors most formidable to look upon,—grim, gigantic, and armed to the teeth; but look at them as you draw closer, and you will see that they are stuffed scarecrows only, with the straws bursting out at the seams of their garments. Likewise of the great dogs that lie across the thresholds of the doors,—nothing but skin and straw; and the noble steeds that stand out in the court-yard there,—all straw and skin, with false manes and tails, made of hair that never belonged to them, but might once have been the property of good, honest quadrupeds, that did their work as such. Yet the foolish people go to and fro through the hollow-sounding galleries, and up the winding stairs, all smiling and bowing and despising each other as they go. Here they crowd round a great picture that hangs upon the wall. It is black with age, dirty, and seamed with cracks, and they clap their hands before it, and make telescopes with their hands to look at it through, because they are sure it must be a fine picture,—“it is so old.” And many of the young men—ay, and some who are not so very young either—gather round a glass case, under which there sits imprisoned a splendidly dressed young girl. The carpet at her feet is strewe with bags of gold. And yet how unhappy she looks, as she sits there like a caged bird! She is a great heiress, poor child! and is kept on exhibition at the castle of Sham. It is a way they have in the society that crowds to the shrine of the lord of that castle. They put up their heiress on show, previous to her sale by auction, and it is to the highest bidder that she goes at last. He may be a fool, ugly, decrepit, and old, to whom the poor little heiress is awarded; but he must have the gold to measure against her gold, coin for coin.

And now, ere we quit the castle of Sham, gaze with me awhile from one of its cobwebbed windows, and you shall see a sight most wonderful to behold. It is a procession of the chief retainers and dependents of the giant Sham. At the head of it there is a crowned king, after whom come lords and ladies, struggling with each other to kiss the hem of his robe. After the lords and ladies come others who are not quite so grand, and who, far out of reach of the royal hem, content themselves with kissing that of the noble kissers who are before them. Lower still in the line are personages of lesser importance, all kissing the hems of those in front, and so on in an endless succession of humiliation and flattery to the end,—the lesser making of the greater an idol for imitation and worship. Look well upon this curious show, and think how ridiculous you would appear were you foolish enough to make one at such a silly game.

But we must return to the two knights, whom we have left steadily pursuing their way to the castle of Sham,—for their cry is ever, “Onward, march!” They had come so close to the castle walls now, that the sounds of the revelry going on within fell harshly upon their ears. Stragglers in masks came reeling down the road, bloated and flushed from the recent debauch, addressing one of whom, Sir William asked of news from the castle.

“Great merry-makings within there, Sir Knight,” replied the reveller. “The myrmidons of the mighty Sham have captured a beautiful princess, called by men the Lady Truth. She lies imprisoned within yon black walls, with golden fetters upon her ankles and wrists, and loud is the joy in the halls of Sham because of the heavy ransom they expect to get for her.”

A glance of meaning passed between the two knights. “What!” exclaimed Sir William, “a ransom for our own dear princess, the Lady Truth? Here is the only ransom the old rascal of the rock shall get from me!”—and, drawing his sword, he flourished it three times in the air, the reflection from its blade flashing like lightning upon the dark walls of the castle.

“Now for the spell given to me by Satira the Sorceress!” said Sir John,—“the magic talisman, the master-key before which the locks of deceit give way and crumble to dust”;—and, drawing from his bosom a small casket, he took from it a gem that threw out sparks on every side as the sunlight flashed upon it. “With this we can throw open the castle gates,” added he, “and then for our trusty swords, and three cheers for the right!”

“Blow again upon your bugle-horns,” said Sir William to the two squires; and not soft and low this time, but loud and strong, went the bellowing of the horns, as the dwarfs blew from them a warning to the warders of the castle that strangers were at the gate.

The notes had not ceased to reverberate among the rocks and buttresses when a wicket in the gate flew open, and a strange-looking figure emerged from it. This personage was clad in a livery of sky-blue plush, studded with buttons that looked like pewter plates. White cotton stockings covered the protruding calves of his legs, and the buckles upon his shoes were of great size and splendor. His cheeks were bloated and pimply, and his hair shone with pomatum, of which the perfume was very strong. High living had made him insolent,—for, though he was only chief footman to the giant Sham, he threw into his deportment an air of languor and haughtiness observed by him among the great lords, the affectation of which made the vulgar creature look very ridiculous indeed.

Turning up his nose at the two knights, he said, mincingly: “Business persons, I see. Folks coming on business to my lord must send up their references”;—and he held out a gilt salver as he spoke.

“Pampered varlet!” shouted Sir William, “there is my reference!”—and, kicking the pinchbeck tray out of the fellow’s hand, he sent it spinning away in the air like a leaf in a gale of wind. Then, seizing him neck and crop, he strove to hurl him from the rock into the abyss beneath; but lo! the thing was all a puppet and a deceit, and the clothes of which it was made up went fluttering down the rocks, catching upon the thorns as they went, here a coat and there a wig, but the rest was all emptiness and air.

The wicket had closed after the puppet footman of the castle with a secret spring, but Sir John again opened his casket, and, at a touch from the magic jewel contained in it, the great portals flew open, and the two knights dismounted from their horses and entered the court-yard, sword in hand, where an extraordinary scene presented itself to their view. Huddled upon the ground, in every variety of attitude, lay the revellers of the halls of Sham, overcome by the drowsy slumber that succeeds debauch. Masks of the most grotesque hideousness were strewn everywhere around, mingled with the fragments of crystal drinking-vessels, while here and there lay the golden goblet and the emptied wine-glass, silent witnesses to the carousal that was over. In the midst of all towered the hideous form of the giant Sham, seated upon a painted throne, with his head bowed down upon his breast in a drunken sleep. But the figure that chiefly arrested the gaze of the two knights was that of a beautiful woman, bound hand and foot with golden fetters, and linked with heavy chains to the foot of the monster’s throne. This was the Lady Truth. She raised her hands with a gesture of surprise, and a flush of joy suffused her pale features as she recognized the two knights; for she knew them well, and was sure now that her deliverance from the bondage of the odious giant was at hand.

“Fear not, lady,” said Sir John, approaching her with a courtly bow, “I have here a talisman before which the bolts and fetters of the tyrants are but gossamer threads”;—and, so saying, he touched her fetters with the radiant gem, and straightway they fell from her limbs, and, kneeling before her deliverer, she clasped her hands with emotion, thanking him in words of the simplest eloquence,—for were they not the words of Truth?

At this moment the giant, disturbed by the voices around him, awoke with a start that shook the castle walls and set all the bells a-ringing. When he saw himself confronted by two armed knights, and that his fair captive had been rescued from her bondage, his already hideous countenance assumed an expression of fury that was awful to look upon. He shook himself like a lion, and tried to roar like one, but the effort ended only in a squeak like that of a mouse. The only effect that this had on the two knights was to make them burst out laughing at him. Sir William, indeed, applied some epithets to him that were more forcible than flattering, and Sir John held his shield so that the monstrous old rascal could see his ugly image in it; and this, as you may well guess, did not tend to allay his fury in the least. Determined to come to a conclusion with his unwieldy foe, Sir William now made a signal to Stylus and Plumbago, who, creeping stealthily round by the back of the throne, stuck pins into the calves of old Sham’s clumsy legs. Goaded into fury by the taunts and treatment to which he was thus subjected, the huge monster now threw himself suddenly forward, like some great rock detached from a mountain’s brow. He meant to fall upon his assailants and crush them to death; but Sir John stepped nimbly aside, while Sir William throwing himself into an easy attitude, received the giant upon the point of his sword, which went through him to the hilt,—and that was the end of the giant Sham.

And did he bleed, do you suppose now, and die as warriors die on the gory battle-field? Not a bit of it, my little friends. When the sword pierced him he vanished into thin air, just as a soap-bubble will do if you prick it with a pin. Like his guards, and his footmen, and his horses, and his dogs, he was all a deception and a cheat. There was nothing of him; and to nothing he went when touched by the magic weapon of the brave knight. Nothing to nothing,—thin air to thin air,—that was the end of the giant Sham. But I regret to say that his race is not yet utterly extinct. May I not hope that you will all take vows upon yourselves to abolish and exterminate and annihilate them wherever they are to be met?

The setting sun was now gilding the spires of the distant town, as the two knights retraced their way thither, bearing between them the Lady Truth, mounted upon a beautiful milk-white steed, which came to her, fully caparisoned, at a touch from the magic talisman of Sir John, which had the power of producing horses, or anything else, at the will of the holder—if he only knew how to hold it aright. And when they had gone some distance over the plain, they turned to look at the castle of Sham, and lo! there it was crumbling away to nothing, with the rock upon which it stood, and all the noxious things that dwelt in and around it. Down, down, like a castle of cards, it tottered, until it disappeared entirely from the sight, and there was no more left of it than of its late proprietor, the abominable tyrant Sham. And round the spot where it disappeared there now surged to and fro a mighty crowd of people, who had heard of the defeat of the giant by the two knights, and came rushing from all parts of the land to see how he looked when he was dead. But the sight would not have been a very agreeable one, as you may imagine, and it is quite as well, perhaps, that these good people were spared the horrors of it.

There was great joy in the town when the two knights entered it that lovely summer evening, with the sweet princess saved by them from the discomfited tyrant of the castle. The bells of all the steeples were set ringing merrily. Bonfires were lighted in the public squares, and feasts were prepared for the poor as well as for the rich, because the hearts of the people were glad, and from the fulness of them came the open hand. In the great market-place, on the very spot where Sir John had hung his shield in the morning, a splendid trophy was erected, composed of the armor and weapons of the two knights, who were now to rest from their labors. At nightfall the young men and maidens assembled in the market-place, to dance round this trophy, and celebrate the extinction of the bad giant, Sham. And, as they danced and sung, behold! a halo of pale, tender light descended upon the two knights, who, enveloped in its mild splendor, arose slowly into the air and faded gradually away from the view of men, attended by their faithful squires, who followed them to the last. Upon earth they shall appear no more, for their work is done: but ever and anon their voices shall be heard in the stillness of the night, and their “Onward, march!” shall reverberate far and wide so long as the world exists.

And this is the true story of the two brave and gentle knights, Sir William Makepeace Thackeray and Sir John Leech.

Charles Dawson Shanly.

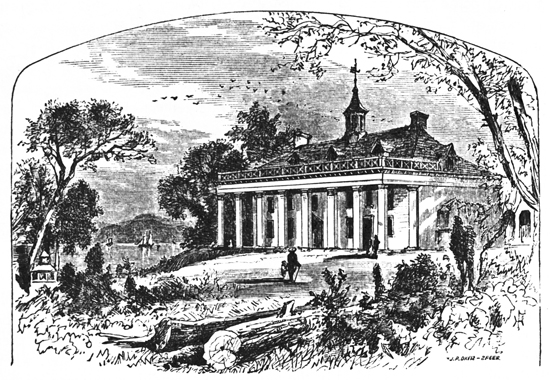

ON a day of exceeding sultriness (it was the 4th of September), I left the dusty, stifled streets of Washington and went on board the excursion steamer Wawaset, bound for Mount Vernon.

Ten o’clock, the hour of starting, had nearly arrived. No breath of air was stirring. The sun beat down with torrid fervor upon the boat’s awnings, which seemed scarce a protection against it, and upon the glassy water, which reflected it with equal intensity from below. Then suddenly the bell rang, the boat swung out in the river, the strong paddles rushed, and almost instantly a magical change took place. A delightful breeze appeared to have sprung up, increasing as the steamer’s speed increased. I sat upon a stool by the wheel-house, drinking in all the deliciousness of that cooling motion through the air, and watching compassionately the schooners with heavy and languid sails lying becalmed in the channel,—indolent fellows drifting with the tide, and dependent on influences from without to push them,—while our steamer, with flashing wake, flag gayly flying, and decks swept by wholesome, animating winds, resembled one of your energetic, original men, cutting the sluggish current, and overcoming the sultriness and stagnation of life by a refreshing activity.

Our course was southward, leaving far on our right the Arlington estate embowered in foliage, on the Virginia shore, and on our left the Navy Yard and Arsenal, and the Insane Asylum standing like a stern castle half hidden by trees on the high banks back from the river. As we departed from the wharves, a view of the city opened behind us, with its two prominent objects;—the unfinished Washington Monument, resembling in the distance a tall, square, pallid sail; and the many-pillared, beautiful Capitol, rising amid masses of foliage, with that marvellous bubble, its white and airy dome, soaring superbly in the sun.

Before us, straight in our course, was Alexandria, quaint old city, with its scanty fringe of straight, slender spars, and its few anchored ships suspended in a glassy atmosphere, as it seemed, where the river reflected the sky. We ran in to the wharf, and took on board a number of passengers; then steamed on again, down the wide Potomac, until, around a bend, high on a wooded shore, a dim red roof and a portico of slender white pillars appeared, visible through the trees. It was Mount Vernon, the home of Washington. The shores here, on both the Maryland and Virginia sides, are picturesquely hilly and green with groves. The river between flows considerably more than a mile wide,—a handsome sheet, reflecting the woods and the shining summer clouds sailing in the azure over them, although broad belts of river-grass, growing between the channel and the banks, like strips of inundated prairie, detract from its beauty.

As we drew near, the helmsman tolled the boat’s bell slowly. “Before the war,” said he, “no boat ever passed Mount Vernon without tolling its bell, if it had one. The war kind o’ broke into that custom, as it did into most everything else; but it is coming up again now.”

We did not make directly for the landing, but kept on down the channel, until we had left Mount Vernon half a mile away on our right. Then suddenly the steamer changed her course, steering into the tract of river-grass, which waved and tossed heavily as the ripple from the bows shook it from its drowsy languor. The tide rises here some four feet. It was low tide then, and the circuit we had made was necessary to avoid grounding on the bar. We were entering shallow water. We touched, and drew hard for a few minutes over the yielding sand. The close grass seemed almost as serious an impediment as the bar itself. Down among its dark heaving masses we had occasional glimpses of the bottom, and saw hundreds of fishes darting away, and sometimes leaping sheer from the surface, in terror of the great, gliding, paddling monster, that was invading in that strange fashion their peaceful domain.

Drawing a well-defined line half a mile long through that submerged prairie, we reached the old wooden pier built out into it from the Mount Vernon shore. I did not land immediately, but remained on deck, watching the long line of pilgrims going up from the boat along the climbing path, and disappearing in the woods. There were perhaps a hundred and fifty in the procession, men and women and children, some carrying baskets, with intent to enjoy a nice little picnic under the old Washington trees. It was a pleasing sight, rendered interesting by the historical associations of the place, but slightly dashed with the ludicrous, it must be owned, by a solemn tipsy wight, bringing up the rear, singing, or rather bawling, the good old tune of Greenville, with maudlin nasal twang, and beating time with profound gravity and a big stick.

As the singer, as well as his time, was tediously slow, I passed him on the way, ascended the long slope through the grove, and found my procession halted under the trees on the edge of it. Facing them, with an old decayed orchard behind it, was a broad, low brick structure, with an arched entrance and an iron-grated gate. Two marble shafts flanked the approach to it on the right and left. Passing these, I paused, and read on a marble slab over the Gothic gateway the words:—

“Within this enclosure rest the remains of General

George Washington.”

The throng of pilgrims, awed into silence, were beginning to draw back a little from the tomb. I approached, and leaning against the iron bars, looked through into the still, damp chamber. Within, a little to the right of the centre of the vault, stands a massive and richly sculptured marble sarcophagus, bearing the name of “Washington.” By its side, of equal dimensions but of simpler style, is another, bearing the inscription, “Martha, the Consort of Washington.”

It is a retired spot, half enclosed by the trees of the grove on the south side,—cedars, sycamores, and black walnuts, heavily hung with vines, sheltering the entrance from the midday sun. Woodpeckers flitted and screamed from trunk to trunk of the ancient orchard beyond. Eager chickens were catching grasshoppers under the honey-locusts along by the old wooden fence. And, humming harmlessly in and out over the heads of the pilgrims, I noticed a colony of wasps, whose mud-built nests stuccoed profusely the yellowish ceiling of the vault.

Here rest the ashes of the great chieftain, and of Martha, his wife. I did not like the word “consort.” It is too fine a term for a tombstone. There is something lofty and romantic about it; but “wife” is simple, tender, near to the heart, steeped in the divine atmosphere of home,—

“A something not too bright and good

For human nature’s daily food.”

She was the wife of Washington,—a true, deep-hearted woman, the blessing and comfort, not of the Commander-in-Chief, not of the First President, but of the man. And Washington, the man, was not the cold, majestic, sculptured figure which has been placed on the pedestal of history. There was nothing marble about him but the artistic and spotless finish of his public career. Majestic he truly was, as simple greatness must be; and cold he seemed to many; nor was it fitting that the sacred chambers of that august nature should be thrown open to the vulgar gaze of the multitude. The world saw him through a veil of reserve, as habitual to him as the sceptre of self-control. Yet beneath that veil throbbed a fiery spirit, which on a few rare occasions is known to have flamed forth into terrible wrath. Anecdotes recording those instances of volcanic eruption from the core of this serene and lofty character are refreshing and precious to us, as showing that the ice and snow were only on the summit, while beneath burned those fountains of glowing life which are reservoirs of power to the virtue and will that know how to control them.

Quitting the tomb, I walked along by the old board fence which bounds the corner of the orchard, and turned up the locust-shaded avenue leading to the mansion. On one side was a wooden shed, on the other an old-fashioned brick barn. Passing these, you seem to be entering a little village. The outhouses are numerous. I noticed the wash-house, the meat-house, and the kitchen, the butler’s house and the gardener’s house,—neat white buildings, ranged around the end of the lawn, among which the mansion stands the principal figure.

Looking in at the wash-house, I saw a pretty-looking colored girl industriously scrubbing over a tub. She told me that she was twenty years old, that her husband worked on the place, and that a bright little fellow four years old, running around the door, handsome as polished bronze, was her son. She formerly belonged to John A. Washington, who made haste to carry her off to Richmond, with the money the Ladies’ Mount Vernon Association had paid him, on the breaking out of the war. She was born on the place, but she had never worked for John A. Washington. “He kept me hired out; for I s’pose he could make more by me that way,” she said. She laughed pleasantly as she spoke, and rubbed away at the wet clothes in the tub.

I looked at her, so intelligent and cheerful, a woman and a mother, though so young; and wondered at the man who could pretend to own such a creature, hire her out to other masters, and live upon her wages! I have heard people scoff at John A. Washington for selling the inherited bones of the great,—for surely the two hundred thousand dollars paid by the Ladies’ Association for the Mount Vernon estate was not the price merely of that old mansion, those outhouses, since repaired, and two hundred acres of land,—but I do not scoff at him for that. Why should not one who dealt in living human flesh and blood also traffic a little in the ashes of the dead?

“After the war was over, the Ladies’ Association sent for me from Richmond, and I work for them now,” said the girl, merrily scrubbing.

“What wages do you get?”

“I gits seven dollars a month; and that’s a good deal better’n no wages at all!”—laughing again with pleasure. “The sweat I drop into this yer tub is my own; but befo’e it belonged to John A. Washington.” As I did not understand her at first, she added: “You know the Bible says every one must live by the sweat of his own eyebrow. But John A. Washington, he lived by the sweat of my eyebrow. I alluz had a willin’ mind to work, and I have now; but I don’t work as I used to, for then it was work to-day and work to-morrow, and no stop.”

Beside the kitchen was a well-house, where I stopped and drank a delicious draught out of an “old oaken bucket,” or rather a new one, which came up brimming from its cold depths. This well was dug “in Gen’l Washington’s time,” the cook told me; and as I drank, and looked down, down, into the dark shaft at the faintly glimmering water,—for the well was deep,—I thought how often the old General had probably come up thither from the field, taken off his hat in the shade, and solaced his thirst with a drink from the dripping bucket.

Passing between the kitchen and the butler’s house, you come upon a small plateau, a level green lawn, nearly surrounded by a circle of large shade-trees. The shape of this pleasant esplanade is oblong; at the farther end, away on the left, is the ancient entrance to the grounds; close by, on the right, at the end nearest the river, is the mansion.

Among the shade-trees, of which there is a great variety, I noticed a fine sugar-maple, said to be the only individual of the species in all that region. It was planted by General Washington, “who wished to see what trees would grow in that climate,” the gardener told me. It has for neighbors, among many others, a tulip-tree, a Kentucky coffee-tree, and a magnolia set out by Washington’s own hand. I looked at the last with peculiar interest, thinking it a type of our country, the perennial roots of which were about the same time laid carefully in the bosom of the eternal Mother, covered and nursed and watered by the same illustrious hands;—a little tree then, feeble, and by no means sure to live; but now I looked up thrilling with pride at the glory of its spreading branches, its storm-defying tops, and its mighty trunk, which not even the axe of treason could sever.

I approached the mansion. It was needless to lift the great brass knocker, for the door was open. The house was full of guests, thronging the rooms and examining the relics, among which were conspicuous these:—hanging in a little brass-framed glass case in the hall, the key of the Bastile, presented to Washington by Lafayette; in the dining-hall, a very old-fashioned harpsichord, that had entirely lost its voice, but which is still cherished as a wedding-gift from Washington to his adopted daughter; in the same room, holsters and a part of the Commander-in-Chiefs camp-equipage, very dilapidated; and, in a square bedroom up stairs, the bedstead on which Washington slept, and on which he died. There is no sight more touching than this bedstead, surrounded by its holy associations, to be seen at Mount Vernon.

From the house I went out on the side opposite that on which I had entered, and found myself standing under the portico we had seen when coming down the river. A noble portico, lofty as the eaves of the house, and extending the whole length of the mansion,—fifteen feet in width and ninety-six in length, says the guide-book. The square pillars supporting it are not so slender, either; but it was their height which made them appear so when we first saw them miles off up the Potomac.

What a portico for a statesman to walk under!—so lofty, so spacious, and affording such views of the river and its shores, and the sky over all! Once more I saw the venerable figure of him, the first in war and the first in peace, pacing to and fro on those pavements of flat stone, solitary, rapt in thought, glancing ever and anon up the Potomac towards the site of the now great capital bearing his name, contemplating the revolution accomplished, and dreaming of his country’s future. There was one great danger he feared,—the separation of the States. But well for him, O, well for the great-hearted and wise chieftain, that the appalling blackness of the storm destined so soon to deluge the land with blood for rain-drops was hidden from his eyes, or appeared far in the dim horizon no bigger than a man’s hand!

Saved from the sordid hands of a degenerate posterity, saved from the desolation of unsparing civil war, Mount Vernon still remains to us, with its antique mansion and its delightful shades. I took all the more pleasure in the place, remembering how dear it was to its illustrious owner. There is no trait in Washington’s character with which I sympathize so strongly as with his love for his home. True, that home was surrounded with all the comforts and elegances which fortune and taste could command. But had Mount Vernon been as humble as it was beautiful, Washington would have loved it scarcely less. It was dear to him, not as a fine estate, but as the home of his heart. A simply great and truly wise man, free from foolish vanity and ambition, he served his country with a willing spirit and an eye single to her glory; yet he knew well that happiness does not subsist upon worldly honors nor dwell in high places, but that her favorite haunt is by the pure waters of domestic tranquillity.

There came up a sudden thunder-shower while we were at the house. The dreadful peals rolled and rattled from wing to wing of the black cloud that overshadowed the river, and the rain fell in torrents. Umbrellas were scarce, and, I am sorry to say, the portico leaked badly. But the storm passed as suddenly as it came; the rifted clouds floated away with sun-lit edges glittering like silver fire, and all the wet leafage of the trees twinkled and laughed in the fresh golden light. I did not return to the boat with the crowd, by the way we came, but descended the steep banks through the drenched woods, in front of the mansion, to the low sandy shore of the Potomac, thence walking along the water’s edge, under the dripping boughs, to the steamer;—and so took my leave of Mount Vernon.

J. T. Trowbridge.

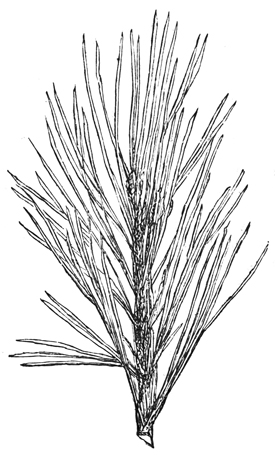

T is midwinter. The trees and shrubs stand

with leafless, bare, smooth branches. The

little plants long ago cowered into the earth,

or gladly sheltered themselves under the dead

leaves, to welcome the white snow coverlet

that tucks them into their beds. Yes, it is

midwinter. But it is January. Already the

sun “has turned,” as people say. Not so.

It is we ourselves that have turned towards

the sun. Our round earth, that has been

giving the sun the cold shoulder, is now coming

back to it again, and rejoices in longer

days and a renewing sunlight.

T is midwinter. The trees and shrubs stand

with leafless, bare, smooth branches. The

little plants long ago cowered into the earth,

or gladly sheltered themselves under the dead

leaves, to welcome the white snow coverlet

that tucks them into their beds. Yes, it is

midwinter. But it is January. Already the

sun “has turned,” as people say. Not so.

It is we ourselves that have turned towards

the sun. Our round earth, that has been

giving the sun the cold shoulder, is now coming

back to it again, and rejoices in longer