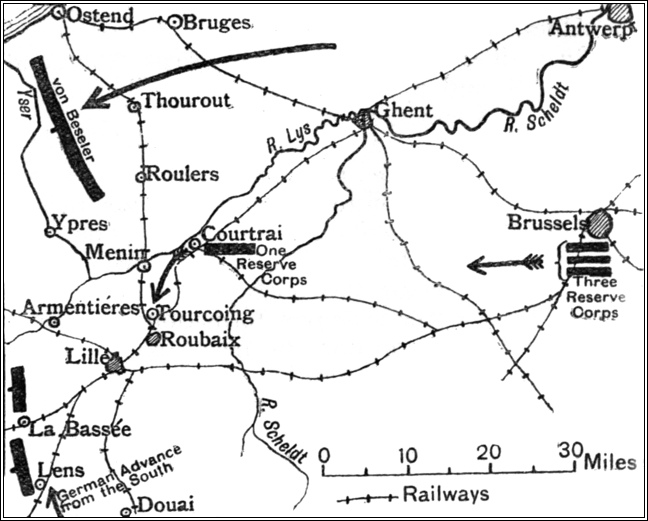

Sketch map showing the three projects of the Allies for the Flanders operations.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Nelson’s History of the War, Volume IV.

Date of first publication: 1915

Author: John Buchan

Date first posted: May 4, 2015

Date last updated: May 4, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20150510

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Paul Dring, Ron Tolkien & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| NELSON’S HISTORY OF THE WAR. By John Buchan. |

| XXV. | The Beginning of the West Flanders | ||

| Campaign | 9 | ||

| XXVI. | The Battles of the Yser, La Bassée, | ||

| and Arras | 51 | ||

| XXVII. | The Battle of Ypres | 81 | |

| XXVIII. | The First Assault on Warsaw | 122 | |

| XXIX. | The Second Russian Advance to | ||

| Cracow | 143 | ||

| XXX. | The Second Assault on Warsaw | 157 | |

| XXXI. | The War in Eastern Waters | 174 | |

| XXXII. | The South African Rebellion | 190 | |

| XXXIII. | The War at Sea—The Battles of | ||

| Coronel and the Falkland | |||

| Islands | 209 | ||

| APPENDICES. | |||

| I. | Sir John French’s Fourth Dispatch: | ||

| The Campaign in | |||

| West Flanders | 229 | ||

| II. | The Work of the Third Cavalry | ||

| Division | 261 | ||

| III. | The Battle of the Falkland | ||

| Islands: Admiral Sturdee’s | |||

| Dispatch | 272 |

| Sketch Map showing the three Projects of the Allies | |

| for the Flanders Operations | 14 |

| De Castelnau’s Operations in the Valleys of the Oise | |

| and Somme | 18 |

| The Arras and Lens District | 20 |

| Smith-Dorrien’s Operations (Second Corps) | 25 |

| Operations of the Third Corps (Pulteney) up to Oct. 19 | 30 |

| The Retreat from Antwerp | 34 |

| Advance of the four German New Corps | 38 |

| The Allied Line from the Somme to the Sea, about | |

| Oct. 20 | 43 |

| Bird’s-eye View of the Country from Albert to the Sea | 44, 45 |

| Communications of the Nieuport-Ypres-La Bassée-Arras | |

| Front with the Channel Coast about Calais and | |

| Boulogne | 52 |

| The Fighting on the Allied Left. (a) Result if the | |

| Enemy had broken through by the Coast Route | 54 |

| The Fighting on the Allied Left. (b) Result if the | |

| Enemy had broken through about Arras | 56 |

| The Yser Front, Nieuport to Dixmude | 59 |

| The Inundations on the Yser Front | 65 |

| The Fighting about La Bassée | 70 |

| The Arras and Lens District | 78 |

| Neighbourhood of Ypres | 83 |

| [8]Position of the Line at Ypres on Oct. 21 | 87 |

| Position at Ypres on the Morning of Oct. 23 | 91 |

| The Front at Ypres on Oct. 27 | 95 |

| The Fighting between Gheluvelt and Le Gheir, Oct. 29 | 98 |

| Position on Oct. 30 | 101 |

| Fighting at Gheluvelt on Oct. 31 | 105 |

| The Line of the Front after the Fight at Messines, Nov. 1 | 107 |

| The Fight at Klein Zillebeke, Nov. 6 | 110 |

| Von Hindenburg’s First Advance on Warsaw | 128 |

| Defences of Warsaw | 133 |

| The Battles on the Vistula, Oct. 1914 | 137 |

| Furthest Westward Advance of the Russians (Nov. 1914) | 141 |

| Russian piercing Strategy before Nov. 13 | 146 |

| The Russian Position near Cracow at the beginning of | |

| December | 150 |

| The Austrian Movement against Dmitrieff | 152 |

| Position of the Russians in Galicia at Christmas | 155 |

| The “Pocket” in the Russian Line | 163 |

| Russian Position at Christmas from the Bzura to the | |

| Upper Vistula | 169 |

| Germany’s Pacific Possessions | 176 |

| The Route of the Emden | 181 |

| Tsing-tau and its Environs | 184 |

| Map illustrating the Wanderings of De Wet and Beyers | 202 |

| Battle of Coronel, Nov. 1 | 215 |

| Battle of the Falkland Islands, Dec. 8 | 219 |

| Battle of the Falkland Islands, Dec. 8 | 221 |

| Battle of the Falkland Islands, Dec. 8 | 223 |

Marlborough’s Campaign in West Flanders—The Allies’ Plan in the First Days of October—The Three Strategical Alternatives—The German Purpose—Meeting of Foch and French—De Castelnau’s Fighting on the Oise and Somme—Importance of Arras—Maud’huy’s Stand at Arras—Movements of Smith-Dorrien at La Bassée—Arrival of the Indian Division—Movements of Pulteney and Allenby—Attempt to clear Right Bank of Lys—Retreat of the 7th Division from Belgium—Sir John French’s Order to seize Menin—Arrival of Haig’s First Corps—Haig’s Instructions—Belgians take up Position on the Yser—Position of Allied Line on 20th October from Albert to the Sea—Allied and German Numbers—Description of Terrain.

In this war the historian, in whatever part of the arena he moves, is accompanied by mighty shades. In the East, in the woody swamps of Masurenland and the wide levels of Poland, he has Kutusov to attend him, and Barclay de Tolly and Bagration, and the inscrutable face of Napoleon. In the West, looming like clouds through the years, he sees the shapes of Cæsar and Attila and Theodoric and Charlemagne, and, as the centuries pass, [10]a motley host of great captains—Charles of Burgundy, Joan the Maid, Bedford, Talbot and King Harry, Guise and Navarre, Turenne and Condé, the Roi Soleil, Villars, Marlborough and Saxe. Then come the shaggy leaders of the Revolution, and Napoleon again with his twenty marshals, and the pursuing Teutons, Bluecher and Schwarzenberg, and Wellington, holding himself a little aloof from his ill-assorted colleagues. And last, in the clothes almost of our own day, we have the sturdy, bristling figure of Bismarck and the unearthly pallor of Moltke. Of all these we have already trodden the battlefields, and now we return to the campaigning ground of one who ranks only after Cæsar and Napoleon. The cold, beautiful eyes of John Churchill had two centuries ago scanned the meadows of West Flanders, and Marlborough’s subtle brain had faced the very problem which was now to meet the Allied generals.

After the crushing defeat of Blenheim, the French Marshal, anxious for the safety of Paris, took to a war of earthworks and entrenchments. He could not save Flanders, but he managed to check the invader in Northern France. But after Oudenarde not all Vauban’s fortifications could keep Lille from the Allies, and Villars prepared the great line of trenches from the Scarpe to the Lys, which had for their centre the high ground about La Bassée. What followed is familiar to every student of the history of the British army. Marlborough feinted against the lines, turned eastward, took Tournai, and won the Battle of Malplaquet. Villars replied with a new line of trenches, and, though the Allies took Bethune and Douai, La Bassée itself proved [11]impregnable, and the war of entrenchments moved toward that stalemate which ended three years later with the Peace of Utrecht.[1]

Had Marlborough had a free hand, the turning movement, in which Malplaquet was an incident, might well have brought his armies to the gates of Paris. Villars’ qualified success showed the enormous strength of entrenchments in that corner of France which marches with West Flanders. When the Allied generals in the first days of October 1914 considered the situation, the campaign of Marlborough must have occurred to their minds. It was true that the situation was reversed, for it was the entrenching of the invader that they wished to forestall, and they moved from the south, not, as Marlborough had done, from the north. At that time they believed that they had the initiative in their hands, and their aim was to turn the German right, and free Flanders of the invaders. For this purpose—as well as for defence, should their offensive fail—it was necessary to gain the two crucial positions of La Bassée and Lille. The first gave the strongest defence in all the district, and the second was even more vital than in Marlborough’s day, for it controlled the junction of six railway lines and a great network of roads, and contained large engineering works and motor factories, as well as the construction shops of the Chemin de Fer du Nord. With Lille as a position in the Allied lines the invasion from the east would be in a doubtful case. The city, which had been defended by General Percin at the beginning of the German sweep from the Sambre, had fallen easily; but since then [12]it and the surrounding country had reverted to the French, and was held at the moment by a division of Territorials. It is reasonable to assume that the occupation of Lille in force was one of the chief tasks entrusted to General Maud’huy when, at the end of September, his new army aligned itself on General de Castelnau’s left.

In telling the story of the West Flanders campaign, the hardest and most intricate which the Allies had yet fought, it is necessary to proceed slowly and with circumspection. No rapid summary will enable the reader to understand the nature of the task which confronted the Allied forces. It is a self-contained campaign, and concerns only three out of the eleven Allied armies—the 8th French Army under d’Urbal, the British army, and the 10th French Army of Maud’huy.[2] Its story is of three successive strategical plans which miscarried, then of three weeks of a desperate defensive which broke the enemy’s attack, then of a period of stalemate and the beginning of a counter-offensive. Its main interest is, therefore, tactical, and the material for a full tactical [13]history is still lacking. We know enough, however, to recount the chief heads in the great story. The record naturally divides itself into three parts—the movements which culminated in the positions reached by all three armies on or about the 20th of October; the attacks upon the Allied line on the Yser, at La Bassée, and at Arras; and the main attack delivered at the same time upon the forces holding the salient of Ypres. With the failure of the assault upon Ypres the West Flanders campaign entered upon its second phase.

Sketch map showing the three projects of the Allies for the Flanders operations.

In the first days of October the Allied plan, based on the assumption that Antwerp could be saved, was so to extend their left as to hold the line of the Scheldt from Antwerp to Tournai, continuing south-west by Douai to Arras, and with this as a base to move against the German communications through Mons and Valenciennes. For this purpose the Naval Division was sent to Antwerp, and Sir Henry Rawlinson, with the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division, landed at Ostend and Zeebrugge. By 6th October it was seen that Antwerp must fall, and this plan was replaced by a second. The Belgian army, covered by Sir Henry Rawlinson’s British force, would retire by Bruges and Ghent to the line of the Yser to protect the Allied left, and meet, along with the new French reinforcements, any coast attack by the German troops released after the fall of Antwerp. Lille and La Bassée must be held by the Allies, and the British, pivoting on the latter place, would swing south-eastward, isolate von Beseler’s army, and threaten the north-western communications of the vast German front, which now ran from some [15]where near Tournai southward to the Aisne heights, and then eastward to the Argonne. In the last resort, if the Allies were forestalled in La Bassée and Lille, the strategy of Marlborough might be used, and, instead of a frontal attack, an enveloping movement could be attempted from the line of the Lys against the right flank of the main German armies. For this purpose the town of Menin on the Lys, south-east of Ypres, was essential as a pivot, and we shall see how the loss of this point ruined the last of the three strategical schemes. Clearly the whole of the Allied plan was contingent on the German right not being farther north than, say, Roubaix. General Joffre knew that it was rapidly extending, and it was the business of his whole northern movement to overlap it. Time was, therefore, of the essence of his problem.

The strategy was well conceived. If it succeeded, the Allies might be in the position to strike a decisive blow. If it failed, then the situation would be no worse. It is true that the extension of the lines to the sea would prevent any attack upon the German communications, which would now be sheltered behind a ring-fence of arms. But, on the other hand, it would prevent any German enveloping movement, and pin down the enemy to a slow war of positions, and, since time was all on the side of the Allies, he would be driven to a stalemate, which would militate disastrously against his ultimate success.

The Germans, it is now plain, were well informed from the start as to the Allied movement, and clearly divined General Joffre’s intentions. By the end of September they had begun the transference of first [16]-line corps from the southern part of their front. They had excellent railways behind them for this purpose, and, since they held the interior lines, most of their corps had a shorter distance to travel than those of the Allies. But in the case of the Bavarians around Metz the change took some time, and so it fell out that the more northerly parts of the line were not manned till the Allies were almost in position. Against this drawback, however, the Germans had one great advantage. They had a fairly fresh army released from Antwerp, which could occupy the coast end, and they had through North Belgium a straight line from Northern Germany for the dispatch of newly-formed corps. They had quantities of cavalry, which had been of no use in the Aisne battle, to harass the left flank of the Allied turning movement, and to occupy points of vantage till their infantry came up. But it was an anxious moment for the German Staff. For them, not less than for the Allies, it was a race to the salt water. To the Allies’ scheme they sought to oppose a counter-offensive which should give them Calais and the Channel ports, and the Seine valley for an advance to Paris. To succeed they must be first through the sally-port between La Bassée and the sea. If the British forestalled them, von Beseler would be cut off, and the German front would be bent round into a square, with the Allies operating against three sides of it. The forty miles between Lille and Nieuport became suddenly the Thermopylæ of the war.

On 8th October General Foch, who had been appointed to a general command over all the Allied troops north of Noyon, was at Doullens, a town [17]some twenty miles north of Amiens. There he was visited by Sir John French, who arranged with him a plan of operations. In all likelihood the Germans would attack the points of junction of the Allied armies—always the weak spots in a front, and it was necessary to determine these points with great care. The road between Bethune and Lille was fixed as the dividing line between the British command and Maud’huy’s army. If an advance were possible it would be eastward, when the British right and the French left would be directed upon Lille. To the north it was arranged that the British Second Corps should take its place on Maud’huy’s left, with the cavalry protecting its left till the Third Corps came into line. The cavalry would perform the same task for the Third Corps till the First Corps arrived in position. Nothing was decided about the future of Sir Henry Rawlinson’s 7th Division and General Byng’s 3rd Cavalry Division, which were covering the Belgian retreat from Antwerp, and might be expected in a week from the direction of Courtrai.

De Castelnau’s operations in the valleys of the Oise and Somme.

(The black line shows approximately his front at the end of September.)

In considering the movement into line we must begin with de Castelnau’s 7th Army, which, as we have seen, formed up on Maunoury’s left on theSept. 21. 20th of September. At first its success was rapid. Von Kluck’s right wing, reinforced by the troops released after the fall of Maubeuge, formed the only opposition. On the 21st it took Noyon, on the Oise, and was pushing its way by Lassigny to Roye through the flats which extend from the Oise to the Somme. But, four days later, the Germans had brought up by rail reinforcements from von Buelow’s command, and a three days’ [18]battle was fought between Noyon and the Somme. De Castelnau was pushed back from Noyon and Lassigny, and held a line from Ribecourt, on the [19]Oise, through Roye, behind Chaulnes, to a point east of Albert on the plateau north of the Somme. His left was extended by at least two Territorial divisions under General Brugère. Any French advance in the direction of St. Quentin and La Fère was obviously fraught with danger for the western German communications, and the last week of September and the first week of October saw repeated assaults upon de Castelnau’s centre at Roye, and upon the left wing on the Albert plateau. The line sagged in places, but in the main the French held their ground; but they did not advance, for by this time they had against them von Buelow himself and the left wing of his transferred army. In those days both sides suffered heavily, and the Germans seem to rate the Battle of Albert as one of the most desperate in the war. At Quesnoy and at Lihons, on the Amiens road, German attacks were repulsed with great slaughter; but all efforts of the French general to swing his left towards Peronne were frustrated.

On the last day of September de Castelnau received a welcome reinforcement in Maud’huy’s 10th Army, which now came into position beyond the Territorials on his left. The right of the new force rested on the little river Ancre, north of Albert, and extended along the plateau to Arras at its northern end, with its left at Lens, on the railway from Arras to Bethune. Maud’huy had a considerable force of cavalry, which scoured the country to the north towards the Lys and the Yser, and several Territorial divisions under his command moved eastward, and occupied Lille and Douai on the German right. These Territorials were obviously in a position of great danger should the Ger [20]mans push on their outflanking movement, and it is clear that at this date—the beginning of October—the Allied generals were convinced that they would be the first to overlap. Maud’huy’s instructions seem to have been to move eastwards towards Valenciennes, and to keep the country clear towards Lille.

The map shows the scene of fighting about Arras, the importance of the place as a great centre of road and railway communications, and its connection with the ground held by the British right between Bethune and La Bassée.

A glance at the map shows the strategic importance of Arras, the centre of Maud’huy’s front. [21]It lies below the northern end of the plateau which extends from the Somme valley to the great plain of the Scheldt. The slopes on three sides of it provide strong defensive positions, and a network of railways connects it with every part of Northern France. The beautiful old city is famous in history. There the treaty of peace was signed after Agincourt, there Vauban raised his famous ramparts, there Robespierre first saw the light. The Germans had entered it on 15th September, but had retired on the approach of Maud’huy’s vanguard. The French general lost no time in taking the offensive. He entered Arras on the 30th of September, and next day had pushed well eastward on the road to Douai, whence his Territorials had been evicted.

During the first three days of October Maud’huy was heavily engaged in the flats east of Arras, between the river Scarpe and the town of Lens. The Germans, who had now got the Bavarian army from Metz on their right wing, were attempting to outflank him on the north, and roll him back to the line of the Somme, in which case Amiens and the Seine valley and the Channel ports would be at their mercy, for the British army was still engaged in changing ground. The German plan seems to have been to send out a force of cavalry, with infantry supports in motor buses, in a wide sweep to the north-west towards the line Bethune-Cassel—the force which, a few days later,Oct. 4-6. was to give much trouble to the British Second and Third Corps as they advanced to their positions—and to concentrate the bulk of their troops in an attack upon Maud’huy’s centre and left. On [22]4th October Maud’huy was compelled to retire on Arras, and to take up ground on the slopes behind it. Two days later the Germans bombarded the city, and continued to drop shells into it intermittently for the following three days. Much damage was done, and part of the beautiful old Town Hall was ruined, but the invaders did not succeed in entering the streets. They crossed the Vauban ramparts, but were driven out by French reinforcements.

On 8th October the French 10th Army was in an awkward place. The Germans held Douai and Lens, and were shelling Lille, from which at any moment the Territorials might be driven. Every day the enemy was increasing in numbers by divisions transferred from the front in Champagne and in the Vosges. The plain of West Flanders was swarming with German cavalry, and about this time they were reported as far west as Hazebrouck, Bailleul, and Cassel, the last place only twenty miles from Dunkirk. Maud’huy’sOct. 19. task was to cling to his position at Arras till some relief came from the Allied operations on his left. That, generally speaking, was the work of both him and de Castelnau for the succeeding ten days up to the 19th of October. There were awkward sags in the French line at Roye, at Albert, and at Arras, but much was done during those days to straighten them out. The attackers were driven back from Arras, and some slight advance was made to the eastward. So stood the position on 19th October, the day when the Allied line was at last completed to the sea. A few days later began the desperate assault on Arras, [23]which was one of the four main attempts to break our West Flanders front.

Maud’huy’s experience supplies an answer to the conundrum—why, since the possession of Lille was of the first importance, was it not held from the first with some force stronger than a Territorial division? The explanation is that Maud’huy was far too sorely pressed to do more than retain his position. Had his offensive succeeded, had he driven the enemy from Douai towards Valenciennes, then Lille would have been occupied by his left wing, and would have formed part of his front. But, as we have seen, he was forced back to Arras, and saved himself only on its western hills. Lille, though we did not know it at the time, was soon to be a point behind the German lines.

We must now turn to the task of the British army, which during the first three weeks of October was coming into line north of Maud’huy. The extreme left of the French 10th Army was at the time in the villages north-west of Lens, and theOct. 11. Lille-Bethune highway had been fixed as its northern limit. Its cavalry was engaged in watching this flank against the dangerous German enveloping movement. On the 11th of October General Smith-Dorrien, with the British Second Corps, had marched from Abbeville to the line of the canal between Aire and Bethune. On his right was the French cavalry connecting him with Maud’huy, and on his left General Hubert Gough’s 2nd Cavalry Division, which was busily engaged driving German cavalry out of the Forest of Nieppe, which lay to the north of the canal. Sir John French’s plan at this time for the Second [24]Corps was a rapid dash upon La Bassée and Lille. Smith-Dorrien was directed to bring up his left to Merville, and on the 12th move east against the line Laventie-Lorgies, to threaten the flank of the Germans in La Bassée, and compel them to fall back lest they should be cut off between the British and Maud’huy.

On the 12th the movement began in thick fog, the 5th Division on the right, and the 3rd crossing the canal to deploy on its left. Smith-Dorrien, however, found that the enemy were in great strength, four cavalry divisions and several Jaeger battalions holding the road to Lille. Moreover, the Germans held the high ground south of La Bassée, where Villars had once constructed the trenches that defied Marlborough. The Second Corps, struggling all day through difficult country where good gun positions were rare, made some progress, but not much. His experience convinced General Smith-Dorrien that an ordinary frontal attack was impossible, and he resolved to try to isolate La Bassée. To quote Sir John French, his object was to wheel to his right, pivoting on Givenchy, and to get astride the La Bassée-Lille road in the neighbourhood of Fournes, so as to threaten the right flank and rear of the enemy’s position on the high ground south of La Bassée.

Smith-Dorrien’s Operations (2nd Corps).

On the 13th the wheel commenced, but it met with a strong resistance. The 5th Division had the hardest fight, and the Dorsets in Gleichen’s Brigade lost their commanding officer, Major Roper, and had 400 casualties, 130 of them being killed. The battalion, which had advanced from Festubert against the Estaires [25]-La Bassée road, maintained its position all day atOct. 14. Pont Fixe. The Bedfords, in the same brigade, were driven out of Givenchy by heavy shell fire. On that day the 14th German Corps had entered Lille, driving out the French Territorials, after a merciless three days’ bombardment. The work of the British Second Corps now resolved itself into a struggle for La Bassée. On the 14th the 3rd Division lost its commander, Major-General Hubert Hamilton, who was killed by the explosion of a shell—a serious loss to the army, for he was one of the most skilful and beloved of the younger generals.[3]

Next day the 3rd Division avenged its leader’s death by a brilliant advance, crossing the dykes by means of planks, and driving the Germans from village after village, till they had pushed them off the Estaires-La Bassée road. On the 16th the 3rd division was close upon Aubers; the following day its 9th Brigade, under General Shaw, took the village, and late that evening the 1st Lincolns and the 4th Royal Fusiliers of the same brigade had carried Herlies at the point of the bayonet.

This was the end of the movement of the Second Corps. Hitherto they had been opposed chiefly by German cavalry, and had made progress, but nowOct. 19. they were against the wall of the main German line. On the 18th counter-attacks began, which Smith-Dorrien succeeded in repulsing; and on the 19th the 2nd Royal Irish, under Major Daniell, in Doran’s 8th Brigade of the 3rd Division, stormed and carried the village of Le Pilly. Next day the German supports from Lille arrived, and the gallant battalion was cut off after heavy losses.

We leave the Second Corps at this point, awaiting the counter-attack, of which they had now had their first taste. About this time supports appeared for General Smith-Dorrien, which merit a brief digression. On 19th and 20th October there arrived somewhere west of Bethune the Lahore Division of the Indian army. The Indian Expeditionary Force consisted of two infantry divisions—the 3rd, or Lahore, under the command of Lieutenant-General H. B. Watkis, and the 7th, or Meerut, under Lieutenant-General C. A. Anderson.[4] The force was under Lieutenant-General Sir James Willcocks, the general then commanding the Northern Army in India, who had originally won fame in West African fighting. On a hot autumn morning the first troops had landed in Marseilles, and been received by the French with the enthusiasm due to their martial appearance and splendid dignity. Then for days the smell of wood smoke rose from the dusty hills behind Borély, strange flocks of goats thronged the streets—the first step in the Indian commissariat—and grave, bearded Sikh orderlies [28]slipped through the southern crowds. From Marseilles the Indian division went to camp at Orleans, and that city, which has seen so much, saw a new pageant in her ancient streets. In the park of a neighbouring country house the Rajput Lancers were quartered, and in countless little things—new cooking smells, new phrases, new colours—the East invaded the West. Much had to be done before the troops were ready for the field, for an equipment adapted for an Indian year is no match for the rigours of a Flemish winter. The troops were chafing to be in action, for the honour of their country and their race was in their keeping in this far Western land, where the sahibs had fallen out. On 10th October Sir James Willcocks issued to his command an address which was admirably fitted to the temper of his men:—

“Soldiers of the Indian Army Corps,—

“We have all read with pride the gracious message of His Majesty the King-Emperor to his troops from India.

“On the eve of going into the field to join our British comrades, who have covered themselves with glory in this great war, it is our firm resolve to prove ourselves worthy of the honour which has been conferred on us as representatives of the Army of India.

“In a few days we shall be fighting as has never been our good fortune to fight before and against enemies who have a long history.

“But is their history as long as yours? You are the descendants of men who have been mighty rulers and great warriors for many centuries. You will never forget this. You will recall the glories of your race. Hindu and Mahomedan will be fighting side by side with British soldiers and our gallant French Allies. You will be helping to make history. You will be the first Indian soldiers of the King-Emperor who will have the honour of showing in Europe that the sons of India [29]have lost none of their ancient martial instincts and are worthy of the confidence reposed in them.

“In battle you will remember that your religions enjoin on you that to give your life doing your duty is your highest reward.

“The eyes of your co-religionists and your fellow-countrymen are on you. From the Himalayan Mountains, the banks of the Ganges and Indus, and the plains of Hindustan, they are eagerly waiting for the news of how their brethren conduct themselves when they meet the foe. From mosques and temples their prayers are ascending to the God of all, and you will answer their hopes by the proofs of your valour.

“You will fight for your King-Emperor and your faith, so that history will record the doings of India’s sons and your children will proudly tell of the deeds of their fathers.

“ James Willcocks,

“Lieut.-General, Commanding Indian Army Corps.”

The Third Corps, under General Pulteney, destined for the position on the left of the Second Corps, had completed its detrainment at St. Omer on the night of the 11th. It marched to Hazebrouck, where it remained during the 12th, and next day moved generally eastward towards the line Armentières-Wytschaete, with its advance guard—the 19th Infantry Brigade and a Brigade of Field Artillery—on the line through the village of Strazeele. Pulteney’s aim was to get east of Armentières astride the Lys, and join up the Ypres and La Bassée sections of the front. It was an impossible length of line for one corps to hold, so he had cavalry operating on both sides of him, Allenby to the north, and Conneau’s French Cavalry Corps to the south.

Operations of the 3rd Corps (Pulteney) up to Oct. 19th.

The Germans were found in strength at Méteren, west of Bailleul, the usual advanced force of cavalry [30]and infantry supports hurried forward in motor buses. It was a day of heavy rain and a thick steamy fog, the fields were water-logged, air-craft were useless, and the country-side was too much enclosed for cavalry. Haldane’s 10th Brigade of the 4th Division was acting as advance-guard, and had the privilege of a bayonet charge against the enemy, in which the 2nd Seaforths distinguished themselves. The Germans in Méteren had no artillery, and but for the bad light would have suffered heavily from our guns. We carried the position, drove out the enemy, and entrenched ourselves some timeOct. 14. towards midnight, preparatory to a full-dress attack upon Bailleul, in which we believed that the Ger [31]mans were in force. Our reconnaissances, however, on the morning of the 14th showed that the enemy had retired, and that day Pulteney occupied the line Bailleul-St.-Jans-Cappelle.

Next day the Third Corps was ordered to take the line of the Lys from Armentières to Sailly, where, five days before, Conneau’s cavalry had met with a stubborn resistance. Armentières is about eight miles from Bailleul, along a straight road. The weather was still dark with fog, and there were many small bodies of the enemy about, but no position was held in force. Pulteney by the evening of the 15th was on the Lys, withOct. 17. the 6th Division on his right at Sailly, and the 4th Division on the left at Nieppe, a point on the Armentières-Bailleul road. Next day he entered Armentières, and on the 17th he had pushed beyond it, with his right at Bois Grenier, three miles south of the Lys, and his left at the hamlet of Le Gheir, a mile north of it. It was now ascertained that the Germans were holding in some strength a line running from Radinghem in the south, through Perenchies to Frelinghien on the Lys, while the right bank of the river below Frelinghien was held as far as Wervicq.

On the 18th an effort was made to clear the right bank of the Lys with the aid of Allenby’s cavalry corps. The strength of the Germans was still doubtful, and Pulteney had some ground for assuming that it was only the mixed cavalry and infantry he had been so far pressing back. As a matter of fact, the Third Corps were now approaching the main German position, [32]as the Second Corps about the same time were finding it at Aubers and Herlies. That day revealed two facts—that the infantry could do nothing in the direction of Lille, and that the cavalry, in spite of some brilliant work by the 9th Lancers, would not win the right bank of the Lys. We found ourselves firmly held at all points from Le Gheir to Radinghem, and our position on the night of the 18th and on the 19th represents the farthest line held by this section of our front. This—the British right centre—was destined to have one of the most awkward places in all the coming battle. It was not itself the object of any great massed attack, as on the Yser, at Ypres, and at La Bassée, but it suffered from being on the fringes of the two latter zones, and, as we shall see, was gravely endangered in the German enveloping movements.

One link was necessary to connect the Third Corps with the infantry farther north. This was provided by the 1st and 2nd Cavalry Divisions,[5] now organized as a corps under General Allenby. The 2nd Division from the 11th of October busied itself with clearing the country of invading bands in the neighbourhood of Cassel and Hazebrouck.Oct. 15-19. On the 14th it joined the 1st Division, and the corps took up positions on the high ground above Berthen on the road between Bailleul and Poperinge. On the 15th and 16th it reconnoitred the Lys, and, till the 19th, endeavoured to secure a footing on the right bank below Armentières. On the night of the 19th Allenby’s [33]position was generally east of Messines, on a line drawn from Le Gheir to Hollebeke.

We pass now to the doings of the Antwerp garrison and the British covering troops. On 6th October the 7th Division began to disembark at Zeebrugge and Ostend, and early on 8th October the former point saw the landing of the 3rd Cavalry Division, after a voyage not free from sensation. The force formed the nucleus of the Fourth Corps,[6] and was commanded by Major-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, who had a long record of Indian, Egyptian, and South African service. The 7th Division was under the command of Major-General Capper, and consisted of the 20th Brigade (Brigadier-General Ruggles-Brise)—1st Grenadiers, 2nd Scots Guards, 2nd Border Regiment, 2nd Gordon Highlanders; the 21st Brigade (Brigadier-General Watts)—2nd Bedfords, 2nd Yorkshires, 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers, and 2nd Wiltshires; and the 22nd Brigade (Brigadier-General Lawford)—2nd Queen’s, 2nd Warwicks, 1st Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 1st South Staffords.[7] The Northumberland Hussars—the first Yeomanry to see foreign service—acted as divisional cavalry. The 3rd Cavalry Division was commanded by Major-General the Hon. Julian Byng, a brilliant cavalry soldier, who had been one of the most successful column-leaders in the South African War, and had since commanded the [35]forces in Egypt. It contained two Brigades: the 6th (Brigadier-General Makins)—10th Hussars, 1st Dragoons (Royals), and a little later the 3rd Dragoon Guards; the 7th (Brigadier-General Kavanagh)—1st and 2nd Life Guards, and the Royal Horse Guards (the Blues).

The Retreat from Antwerp.

On the 6th of October Sir Henry Rawlinson visited Antwerp, where he saw for himself the state of that fortress. Next day his headquarters were at Bruges, and a force of French Marines under Admiral Ronarc’h was brought to Ghent as aOct. 9-12. support. On the 8th the retirement from Antwerp was in full operation, and the Fourth Corps headquarters were removed to Ostend, while the 7th Division was at Ghent. Next day Antwerp had fallen, and the covering of the Belgian retreat began. The cavalry went first, to clear the country, and were at Thourout on the 10th and at Roulers on the 12th, where they took up the line from Oostnieuwkerke to Iseghem to cover the Ghent railway, which was threatened by roving German horse to the west and south. On that day the 7th Division and the French Marines left Ghent, forming a rearguard for the Belgians. Next day the Germans entered that town, and the following day passed through Bruges. Two days later the 3rd Reserve Corps occupied Ostend. This was part of von Beseler’s army of Antwerp, which should probably be rated at two army corps and a cavalry division.

The 7th Division, much assisted by its armoured motor cars, arrived at Roulers on the 13th, and the 3rd Cavalry Division reconnoitred all the country towards Ypres and Menin, [36]riding in one day over fifty miles. The only hostile activity they could learn of was in the south-west, where large enemy forces were reputed to be moving eastwards towards Wervicq and Menin from the direction of Bailleul. This was the force of cavalry and infantry supports with which, as we have seen, the Third Corps had had dealings. The 3rd Cavalry Division was now in touch with Allenby’s cavalry corps in the neighbourhood of Kemmel, on the road between Ypres and Armentières. ByOct. 16. 17. this time the Belgian army, very weary and broken, was in the Forest of Houthulst, north-east of Ypres, and had begun to extend along the line of the Yser by Dixmude to Nieuport. On the 16th the 7th Division was holding a position east of Ypres, with the 3rd Cavalry Division as advance guard on a line which ran roughly from Bixschoote to Poelcapelle. North lay the Belgians, with French Territorial supports, and to the west of Ypres two French Territorial divisions—the 87th and 89th—under the command of General Bidon. The line of the 7th Division ran from Zandvoorde through Gheluvelt to Zonnebeke.

At that time Sir John French was still uncertain about the forces opposed to him. He knew of von Beseler’s army on the coast route, and was naturally anxious as to the stand which the wearied Belgians, aided by French Territorials and cavalry, could make against it on the Yser. He also had news of a German reserve corps and a Landwehr division which had been giving trouble to Allenby’s cavalry on the Lys. The far more formidable movement, of which the 7th Division was begin [37]ning to get news, was still unknown to him, and if he had heard the rumours of it, he had not been able to get verification. At that time he still believed that the extreme right of the main German force was in the neighbourhood of Tourcoing, and that von Beseler’s was an isolated flanking force. He did not know that von Beseler was no more the outer rim of a huge serried line wheeling against the Allies from the north-east.

On 11th October four reserve corps—the 22nd, 23rd, 26th, and 27th—left Germany. Their composition was mainly southern—from Wurtemberg and Bavaria—though troops from Hanover were included. One corps was rushed through by rail to Courtrai, and was, indeed, not formed till the men arrived there. The other three were concentrated in Brussels, and, without losing an hour, began their eighty-mile march westward. These corps were new formations, composed largely of Landsturm and the new volunteers, and including every type, from boys of sixteen to stout gentlemen in middle life. They were to show themselves as desperate in attack as the most seasoned veterans. By the 18th they were on the line Roulers-Menin.

On the 16th the Belgians were driven out of the Forest of Houthulst, and fell back behind the Hazebrouck-Dixmude railway. Their retreat uncoveredOct. 17. the left of the British 3rd Cavalry Division, and on the following day four French cavalry divisions, under General de Mitry, cleared the forest of Germans, and re-established the line. On that night, the 17th, Sir John French decided that the moment had come to put into effect [38]the third of his strategical alternatives. If La Bassée and Lille had proved too strong for the Second Corps, then Marlborough’s famous strategy might be employed against the German right. With Menin as a pivot, commanding an important railway and the line of the Lys, a flanking movement might be instituted against Courtrai and the line of the Scheldt. Accordingly he instructed Sir Henry Rawlinson to advance next morning, seize Menin, and await the support of the First Corps, which was due in two days.

Advance of the Four German New Corps.

Sir Henry Rawlinson had an impossible task. He had to operate on a very wide front at least twenty miles long, and he could look for no sup [39]ports till Sir Douglas Haig arrived. Moreover, he knew of the four new German corps, which wereOct. 19. still hardly credited at headquarters, and on the morning of the 18th the French cavalry near Roulers captured some cyclists belonging to one of them. On the morning of the 19th he moved out towards Menin, with the right of the 7th Division protected as far as possible by Allenby’s cavalry north of the Lys, while the 3rd Cavalry Division was on its left, and de Mitry’s French cavalry to the north of them.

The cavalry to the left presently came in touch with large enemy forces advancing from Roulers. The British brigades were skilfully handled, and the 6th Brigade took Ledeghem and Rolleghem-capelle. But owing to the continued German pressure, the 7th Brigade on the left had to fall back, and in the afternoon the 6th Brigade also followed, retiring to billets in the villages of Poelcapelle and Zonnebeke, while the French cavalry held Passchendaele, a mile in advance. The progress of the infantry was summarily stopped by the advance of enormous masses from the direction of Courtrai. The nearest the 7th Division got to Menin was the line Ledeghem-Kezelberg, about three miles from the town. It had to fall back at once to avoid utter disaster, and entrenched itself on a line of eight miles, just east of the Gheluvelt cross-roads, a name soon to be famous in the annals of the war. The great struggle for Ypres was on the eve of beginning.

On that day, 19th October, the First Corps, under Sir Douglas Haig, detrained at St. Omer, and marched to Hazebrouck. That evening Sir Douglas [40]Haig was instructed to move through Ypres to Thourout, with the intention of advancing on Bruges and Ghent. That such instructions should have been given shows that the British headquarters were still very imperfectly informed about the real strength of the enemy, which the 7th Division were then learning from bitter experience. Two alternatives presented themselves to the mind of Sir John French. His force was holding far too long a line for its numbers and strength, and the natural use of the new corps would have been to strengthen some part of the front, such as that before La Bassée. On the other hand, a much-battered Belgian army with a small complement of French Territorials and cavalry had sole charge of the twenty-mile line from Ypres to the sea. If the Germans chose to attack north of Ypres they would find a weakly held passage. Accordingly Sir Douglas Haig was directed to move north of Ypres, and Sir John French, after instructing him about Thourout and Bruges, bade him use his discretion should an unforeseen situation arise after he had passed Ypres. The unforeseen situation was not long in appearing. The First Corps never approached Thourout, but were detained in front of Ypres, where they formed the left wing of the great struggle.

By the 19th—to continue our course to the sea—the Belgians had fallen back nearly to the line of the Yser from Dixmude to Nieuport. The Yser is a canalized stream, which, rising near St. Omer, enters at Nieuport the canal system which lies behind the sand-dunes on the edge of the cultivated land, and connects with the salt water by [41]several sea canals. The Belgians were, in Sir John French’s words, “in the last stages of exhaustion,” since for ten weeks they had scarcely been out of action, but their spirit was unconquered, and the gaps in their line—they cannot have been more than 40,000—were filled up by French Territorials from Dunkirk, and French Marines under Admiral Ronarc’h, while the British and French fleets were waiting to give them support from the sea. But the front was still dangerously weak, and on 18th October General Joffre placed at the disposal of General Foch the reinforcements which presently became the 8th French Army. It was commanded by General Victor d’Urbal, a man of fifty-six, who, like Maud’huy, had been a brigadier at the beginning of the war. This new army, which not only took over the existing troops on the Yser, but acted as a reinforcement to the British left, contained two famous first-line corps, the 16th, under General Paul Grossetti, who had won a reputation for cool heroism in an army which contained many heroes, and the 9th, under General Dubois, which had been the spearhead of Foch’s onslaught at the Marne, and was to win eternal glory for its deeds at Ypres.

The 20th of October saw the whole Allied line from Albert to the sea in the position in which it had to meet the desperate effort of the Germans to regain the initiative and the offensive. The port was closed, but it might yet be opened. Maud’huy’s 10th Army lay on a line from east of Albert, through Arras, west of Lens, to just west of the château of Vermelles, south of the Bethune-La Bassée railway. Smith-Dorrien’s Second Corps ran from Givenchy, west [42]of La Bassée, through Herlies and Aubers to Laventie. Then came Conneau’s corps of French cavalry, which had done good work on our right at the Marne, and then Pulteney’s Third Corps, which was astride the Lys east of Armentières. North of it came Allenby’s cavalry corps, with the 1st Division south of Messines, and the 2nd Division between Messines and Zandvoorde. Then, forming the point of the Ypres salient, came the 7th Division east of the Gheluvelt cross-roads, with, on its left, between Zonnebeke and Poelcapelle, Byng’s 3rd Cavalry Division. North-west of them, between Zonnebeke and Bixschoote, Haig’s First Corps was coming into position. North, again, lay de Mitry’s French cavalry, till the Belgian lines were reached at Dixmude. These on the 20th were still mostly on the east side of the Yser, but they held the passages for a retreat to the west bank. French marines and Territorials, soon to be absorbed in d’Urbal’s 8th Army, strengthened the Belgian front to the sea, where the guns of the Allied warships were waiting for the enemy.

The Allied Line from the Somme to the Sea, about October 20th.

This line of battle, little short of a hundred miles, was held on the Allied side by inadequate forces. Maud’huy may have had three corps, but he had no more; the British were three and a half corps strong—seven divisions of infantry; the Belgians were in effectives little more than a corps—say a weak corps and a half. That is eight corps, and if we add two corps for d’Urbal’s regulars, and two corps for Territorials, and allow for cavalry and marines, we shall get a strength of about half a million. The British force, where we know the figures with more exactness, had an average strength of only 1.6 [44]rifles per yard of front, and it may be questioned if the rest of the Allied line had a higher average than three. The German numbers can only be conjectured. The commands, as we have already seen, had been redistributed, and von Buelow was against Maud’huy’s left and the British right, the Bavarian Crown Prince against the British centre and left, and the Duke of Wurtemberg against the Belgians and d’Urbal. It is impossible at present to disentangle and identify the different German corps which appeared and disappeared in the opposing lines. Most were new formations, but the nucleus of the armies was still the veterans who had crossed the Sambre and Meuse in August. We can trace, for example, with von Buelow most of the Prussian Guard Corps, the 2nd, 4th, and 9th Cavalry Divisions, and the 3rd (Berlin) Corps, which had belonged to his old command, as well as the 7th (Westphalian) Corps of von Kluck. In the Bavarian command we can trace the 19th (Saxon) Corps, which had struck so stout a blow on the Meuse. The total German force from Nieuport to Albert may probably be put in the neighbourhood of one and a half million[8], and its constituents were constantly being altered by the passage of fresh formations from Germany and the transference of corps and divisions from more stagnant battlefields farther south. This force was so arranged in the actual fighting that at the points of attack the superiority over the Allies was not three but five to one.

Bird’s-eye View of the Country from Albert to the Sea.

A word must be said on the character of the terrain of the impending battles. From the peat [45]-bogs and endless cornfields of the Santerre, where de Castelnau was engaged, the plateau of Albert rises between the Somme and the Scarpe. It is the ordinary Picardy upland—-hedgeless roads, unfenced fields, lines of stiff trees, and here and there the shallow glen of a stream. At the northern end Arras lies in its crook of hills, a beautiful and gracious little city on the edge of the ugliest land on earth. The hills sweep north-westward to the coast of the Channel, ending in Cape Grisnez, and bound the valleys of the Scarpe, Scheldt, Lys, and Yser, forming in reality the western containing wall of the great plain of Europe, of which the eastern is the Urals. This plain of the Scheldt and its tributaries is everywhere of an intolerable flatness. A few inconsiderable swells break its monotony, such as the Cat’s Hill, north of Bailleul, and the undulations south of Ypres and at La Bassée, and there is, of course, the noble solitary height of Cassel. But in general it is flat as a tennis lawn, seamed with sluggish rivers, and criss-crossed by endless railways and canals.

Ten miles north of Arras, at the town of Lens, the Black Country of France begins. From there to Lille and Armentières is the mining region of the Pas de Calais. Every road is lined with houses; factory chimneys and the headgear of collieries rise everywhere; and the whole district is like a piece of Lancashire or West Yorkshire, where towns merge into each other without rural intervals. The Lys flows, black and foul, through a land of industrial débris. North of the Lys towards Ypres we enter a country-side of market gardens, where every inch is closely tilled, and the land is laid out [46]like a chessboard. There are patches of wood, some fairly large, like the Forest of Houthulst, between Ypres and Roulers, but these are no barrier to military movements. Everywhere there are good roads, one-half paved after the Flemish fashion, and the only obstacles to the passage of armies are the innumerable canals. As we move toward the Yser we pass from Essex to the Lincolnshire Fens. The fields are lined and crossed with ditches, and the soil seems a compromise between land and water. Then comes the great barrier of the sand-dunes, which line the coast from Calais eastwards, and through which the waterways of the interior debouch by a number of sea canals. Beyond the dunes are the restless and shallow waters of the North Sea.

On such a line the Allies on the 20th of October awaited the attack of the enemy, as they had done two months before on the Sambre and the Meuse. Now, as then, they were outnumbered; now, as then, they did not know the enemy’s strength; now, as then, their initial strategy had failed. The fall of Antwerp had destroyed the hope of holding the line of the Scheldt; the German occupation of La Bassée and Lille had spoiled the turning movement against the German right; the failure at Menin and the swift advance of the new German corps had put Marlborough’s device out of the question. Once more, as at Mons and Charleroi, we were waiting on the defensive. But our position on 20th October had two advantages over that of 21st August. Our flanks were secured, and we had now taken the measure of our enemy.

Marlborough’s campaigns in West Flanders cover so much of the ground of the present war that a brief note may be permitted. The aim of the Allies in 1708 was to strike at France through the Artois, and for this purpose the control of the navigation of the Scheldt and Lys was essential. It was the object of Vendôme’s army, which marched north in the summer of 1708, to recapture Bruges and Ghent, which were the keys of the lower waterways. It succeeded in this task, but was decisively defeated by Marlborough on 11th July at Oudenarde on the Scheldt, after one of the most wonderful forced marches in history. Marlborough himself now desired to march straight into France, detaching troops to mask Lille, and co-operating with General Erle’s projected descent upon Normandy—a proceeding which would have automatically led to the evacuation by the French of Ghent and Bruges. This bold stroke the caution of the Dutch deputies forbade, and the Allies sat down before the fortress of Lille, bringing their siege train by road from Brussels, since the Scheldt and the Lys were closed to them. Vendôme and Berwick united their armies, and marched from Tournai to Lille, where, however, they did not dare to offer battle, and Marlborough was prevented by his Dutch colleagues from forcing it on them. The French now attempted to hold the line of the Scarpe and Scheldt to Ghent, and cut off all convoys from Brussels; but Marlborough held [48]Ostend, and Webb’s victory of Wynendale enabled the convoys to get through.

Lille, gallantly defended by old Marshal Boufflers, fell on 9th December, and Bruges and Ghent quickly followed. The way to Paris was now dangerously open, and Villars, who took command of the French armies when the campaign opened in the spring of 1709, resolved at all costs to cover Arras, which he rightly regarded as the gate of the capital. He drew up lines of entrenchments from the Scarpe to the Lys, passing through La Bassée. Marlborough, lying to the south of Lille, made apparent preparations for assault in force, and induced Villars to summon the garrison of Tournai to his aid. Meantime the duke had sent his artillery to Menin, and on the 26th of June marched swiftly eastward to Tournai, which fell to him on the 23rd of July. While the siege was going on, Marlborough led his main army back before the La Bassée lines. His object was to turn those lines by striking eastward, and entering France by way of the rivers Trouille and Sambre, and he wished to mislead Villars as to his purpose. On the last day of August, Orkney with twenty squadrons was sent to St. Ghislain to the west of Mons, and the Prince of Hesse-Cassel and Cadogan followed in the midst of torrential rains. Villars, fearing for the fortress of Mons, hastened after them, and on 7th September had arrived before the stretch of forest which screens Mons on the west, and is pierced by two openings—at the village of Jemappes in the north and at Malplaquet in the south. Mons was by this time invested by the Allies, and to cover its siege Marlborough fought the Battle of Malplaquet on 11th [49]September. In that battle—“one of the bloodiest,” says Mr. Fortescue, “ever fought by mortal men”—the Allies had 20,000 casualties as against the French 12,000; and though it was a victory, and Mons fell a month later, the season was too far advanced, and the Allies had suffered too heavily, to allow of an invasion of France. But with Mons and Tournai in their hands, they controlled the Lys and Scheldt, and protected their conquests in Flanders.

In the campaign of 1710 Marlborough’s thoughts again turned westward, and on 26th June he captured Douai. But he found Arras and the road to France protected by a vast line of trenches, which Villars had constructed to be, as he said, the “ne plus ultra of Marlborough.” The duke had to content himself with taking Bethune, Aire, and St. Venant, which gave him the complete control of the Lys. He was in a difficult position for bold action, for his political enemies were lying in wait for the slightest hint of failure to work his ruin. During the winter the work of entrenching went on, and in the spring of 1711 the French lines ran from the coast, up the river Canche by Montreuil and Hesdin, down the Gy to Montenancourt, whence the flooded Scarpe carried them to Biache; thence by canal to the river Sensée; thence to Bouchain, on the Scheldt, and down that river to Valenciennes. The story of how Marlborough outwitted Villars and planted himself beyond the Scheldt at Oisy, between Villars and France, and within easy reach of Arras and Cambrai, deserves to be studied in detail, for it is one of the most wonderful in the whole history of tactics. Thereafter the jealousy and treachery of Marlborough’s enemies achieved [50]their purpose, and the great duke’s campaigns in Flanders were at an end.

Marlborough’s objective was, of course, the opposite of that of the Allies in 1914. They were moving from the south-west, while he moved from the north-east, and the lines of Villars were meant to hinder attack from the east, whereas the Germans at La Bassée were entrenched against an attack from the south and west. But all the line of Northern France from the Scarpe to the Sambre was Villars’ front of defence, as it was the German flank defence about 10th October, when the race to the sea was in progress. If the Allies had been able to push through the gap between Roulers and the Lys and turn the German right, they would have followed the identical strategy of the movement which led to Malplaquet, with this difference, that their object would have been not an invasion of Paris, but the turning of the flank of an entrenched invader.

The Various Routes to Calais—German Strategy Incomprehensible—The Banks of the Yser—German Attack on Nieuport—British Warships in Action—Germans Cross the Yser—The Struggle for Ramscapelle—The Great Inundations—Germans capture Dixmude—Failure of Yser Attack—Attack on La Bassée Position, 22nd October to 2nd November—Loss of Neuve Chapelle—Arrival of Indian Corps—Charge of 2nd Gurkhas—Fighting Value of Indian Troops—Difficulties of the Weather—The Attacks on Arras, 20th-26th October—Maud’huy’s Position.

The Allied battle line in the north, which came to completion about the 19th of October, stretched, as we have seen, from Albert to the sea, a distance as the crow flies of more than eighty miles. If the reader will consult the map on page 52, he will see that two points in this front would give the enemy a special advantage in attack. The first is Arras, which is a centre on which lines converge from West Flanders and North-Eastern France, and from which lines run down the Ancre valley to Amiens and the basin of the Seine, to Boulogne by Doullens and by St. Pol, and northward to Lens and Bethune. The second is La Bassée, which gives a straight line by Bethune and St. Omer to Calais and Boulogne. If the Germans sought possession of the Channel ports, then their [52]natural road was by one or the other. A third possible route lay along the seashore by Nieuport, where the great coast road runs behind the shelter of the dunes. If the aim of the enemy was the speedy capture of Dunkirk, Calais, and Boulogne, a successful breach in the Allied front at Arras or La Bassée would enable them to realize it. Possible, but far less valuable for the same purpose, was the road which followed the sea. It was the shortest route to Calais, but it had no railway to accompany it, and it led through some of the most difficult country which a great army could encounter.

Communications of the Nieuport-Ypres-La Bassée-Arras front with the Channel coast about Calais and Boulogne.

In war the shortest way to an end is often the longest. By this time the German Staff, under the [53]inspiration of von Falkenhayn, had decided that at all costs the Channel ports must be won. Their reason seems to have been twofold. They thought that the capture of Calais and Boulogne would gravely alarm public opinion in Britain, and interfere with the sending of the new levies, which, in spite of their official scepticism, they fully believed in and seriously dreaded. In the second place, with the coast in their possession, they hoped to mount big guns which would command half the width of the narrows of the Channel, to lay under their cover a mine-field, and to prepare a base for a future invasion of England. It was argued that such a measure would complicate the task of the British fleet, which would be compelled to watch two hostile bases—the Heligoland Bight and the French Channel coast—and that in such a division of tasks the chance might come for a naval battle in which the numerical superiority would not lie with Britain. Many other motives, no doubt, lay behind the plan, but these constitute the strategical reasons. Now, with this purpose, the best road was clearly not the shortest. If the Allied front could be pierced at La Bassée, or, still better, at Arras, and a gate were forced for the passage of the German legions, then two of the Allied armies would be cut off and penned between the enemy and the sea. In this way the chief purpose of all campaigns would be effected, and a large part of an opponent’s strength would be finally destroyed. Further, a magnificent line of communications to the coast would be opened up—communications which could not be cut, for all the Channel littoral and hinterland east to Antwerp would be in German hands. If, on the other hand, [54]a way were won along the shore by Nieuport, all that would happen would be that the Allies’ left would fall back to the line of heights which ends in Cape Grisnez, and their front, instead of running due north from Albert, would bend to the north-west in an easy angle. Further, the coast road would be a poor line of communications at the best, and most open to attack by a movement from Ypres or La Bassée.

The Fighting on the Allied Left.

(a) Result if the Enemy had broken through by the Coast Route.

Besides these three points where a road might be won, the Allied lines revealed another special [55]feature. East of Ypres, on the 19th of October, it bent forward in a bold salient, the legacy bequeathed by an offensive which had failed. If this could be maintained, it obviously provided a base for flank attacks upon any force advancing across the Yser and through La Bassée. It was, therefore, the aim of the Germans to flatten out the salient as soon as possible. The importance of Arras, La Bassée, Ypres, and Nieuport must be kept constantly in mind if we would understand the complicated campaign which follows. The first two were the points where a successful piercing movement would have results of the highest strategic value, not only opening up the road to the Channel, but putting the whole Allied left wing in deadly jeopardy. The third was a salient which, if left alone, would endanger any German advance. The fourth, if gained, would give a short, if difficult, route to Calais, and would turn the Allies’ flank, though not in a fashion to put it in serious danger.

The Fighting on the Allied Left.

(b) Result if the Enemy had broken through about Arras.

It is a sound rule in war that strength should not be dissipated. You may attack the enemy’s front at different points, as Napoleon did at Waterloo, but at each point you should attack in full strength. With this in our minds it is hard to discover an explanation for the course which the Germans actually followed. For they attacked almost simultaneously at all four points, and for three desperate weeks persisted in the attack. Why, it is impossible at present to say. Had the movement against Arras succeeded all would have been won, and the salient at Ypres would have only meant the more certain destruction of the British army. Had the attack upon La Bassée been successfully carried [56]through, the same result would have been attained; though, since the success was won farther from the Allied centre, a smaller section of the Allied force would have been isolated. Had even the worst of the three roads been chosen for a concentrated action and the coast route cleared for the passage of the German armies, then the Allied flank must have fallen back from Ypres and La Bassée. But it is hard to understand why a, b, c, d should have been attacked with equal violence when either a or b would have given possession of the others. It is [57]never wise to underrate the intelligence of the enemy, and all that we can say at present is that the German strategy is inexplicable. They may have been so confident of their numerical superiority that they believed they had the strength to spare to carry all four positions. But economy of effort is in itself a doctrine of wise strategy, and on this assumption here was a reckless squandering of strength.

In this chapter it is proposed to deal with the three assaults—on the Yser, at La Bassée, and at Arras—leaving the supreme effort against Ypres for separate consideration. But let it be clearly understood that all four attacks were contemporaneous, and directed against a single battle front. The fighting on the Yser merged, towards the south, in the fighting north of Ypres; the struggle for Ypres was closely connected with the battle which raged from La Bassée to the Lys; and the stand of the Second Corps at La Bassée was influenced in many ways by the fate of Maud’huy’s left wing north of Lens. If this fact is realized, it seems clearer and more convenient to deal separately with each attack, since each had its own special objective.

The sketch on page 59 will explain the nature of the country along the canal which is usually dignified by the name of the Yser, the little river which feeds it from the south-west. Between Nieuport, the port on the coast a mile from the ocean, and the little town of Dixmude, where the Yser turns sharply to the south-west, is a distance of ten miles. On the left bank, at an average distance of a mile and a half from the Yser, runs a single-line railway from Dixmude to Nieuport, through the villages of Per [58]vyse and Ramscapelle. No railway crosses the canal between Dixmude and Nieuport, but it is spanned by several bridges. The most important is at Nieuport, where the main coast road runs along the harder soil of the dunes. A second lies about midway in the reach, where a road comes east from Pervyse just below the point where the canal loops itself in a pocket. At Dixmude itself, which lies on the eastern bank, a road and a line run to Furnes and Dunkirk. A number of small creeks of brackish water enter the Yser on both sides, and all around are low, marshy meadows, a little below the level of the sea. One or two patches of drier and higher land are found along the edge of the canal, but nowhere, till we reach the dunes on the actual coast, are there any slopes which can be said to give gun positions or a commanding situation. The whole country is blind and sodden, as ill fitted for the passage of troops and heavy guns as the creeks and salt marshes of the Essex coast.

The Yser Front, Nieuport to Dixmude.

On the 16th of October, as we have seen, the right wing of the retreating Belgian army had reached the Forest of Houthulst, north-east of Ypres, and had been driven out of it by the German movement from Roulers. They now drew in that wing, and by the following day were aligned on the east bank of the Yser, with French cavalry and Territorials connecting them with the British army to the south. De Moranville can scarcely have had more than 40,000 in his command, and to a man they were battle-weary. But the presence of their king, and the consciousness that they were waging no longer a solitary war, but were aligned with their Allies, spurred them to a great [60]effort. The Yser was the natural line for them to hold, for, more than French or British, they were accustomed to war among devious water-courses. The German force against them was part of von Beseler’s army from Antwerp—not less than 60,000 men—and the Wurtembergers were moving rapidly from the south to join them. The Belgians had by the 17th no other supports for their line than two divisions of French Territorials on their right, and in Dixmude a brigade of French Marines, for d’Urbal’s 8th Army was still in process of formation. The disposition was as follows: the 2nd Belgian Division was in Nieuport, with the 1st on its right, and the 3rd continuing the line to Dixmude. The 5th Division was in reserve on the right centre. Ronarc’h’s Brigade of Breton Marines consisted of two regiments, each with three battalions, a total of about 7,000 men.

By the evening of the 17th von Beseler, to whom the first coast attack had been entrusted, had moved west from Middelkerke and Westende, and was in position just east of Nieuport. In the previous two days there had been an intermittent bombardment, and on the 17th the 1st and 4th Belgian Divisions had been driven across the Yser, but had regained the right bank during the night. Early on the morning of the 18th he attacked with the object of seizing the Nieuport bridge. The Belgians were drawn up east of the Yser, holding in strength the three main bridges. The sudden and violent assault of a superior force upon the left wing of a much-enduring army would in all likelihood have succeeded, and if at this date de Moranville had been [61]pushed well back from the Yser towards Furnes, von Beseler would have been in Dunkirk in two days and in Calais the day after. But at this most critical moment help arrived from an unexpected quarter. Suddenly the German right resting on the sand-dunes found itself enfiladed. Shells fell in their trenches from the direction of the sea, and, looking towards the Channel, they saw the ominous grey shapes of British warships. Two and a half centuries before, when Turenne met the Spaniards at the Battle of the Dunes, he had been greatly aided by Cromwell’s fleet, which shelled the enemy’s wing. History repeated itself almost in the same spot, and once more the French front fought in alliance with the British navy.

Germany had never dreamed of any serious danger from the sea. She believed from the charts that off that shelving shore, with its yeasty coastal waters, there was no room for even a small gunboat to get within range, and she did not imagine that Britain would venture her ships in such perilous seas. Every student of naval history knows the dangers of the “banks of Zeeland,” and at this very place, between Nieuport and Ostend, the San Felipe, from the Spanish Armada, had been wrecked. But at the outbreak of war three strange vessels lay at Barrow, built to the order of the Brazilian Government. Broad in the beam, and shallow of draught, they had been intended as patrol ships for the river Amazon. In August the Admiralty, with fortunate prescience, purchased these strange craft, which appeared in the Navy List as the Humber, the Severn, and the Mersey. They were heavily armoured, and carried each two 6-inch guns mounted [62]forward in an armoured barbette, and two 4.7 howitzers aft, while four 3-pounder guns were carried amidships. Their draught was only 4 feet 7 inches, so that they could move in shoal water where an ordinary warship would run aground. With the first news of the German advance along the coast the Admiralty saw the value of their purchase. On the evening of 17th October the three monitors[9] left Dover under the command of Rear-Admiral the Hon. Horace Hood, and sailed for the Flemish coast. The German attack on the 18th had hardly started when Hood began his bombardment. Von Beseler brought his heavy guns into action, but they were completely outranged, and several batteries were destroyed. For ten days this strange warfare continued. Admiral Hood’s flotilla was presently joined by other craft, chiefly old ships of little value, for the Admiralty did not dare to risk the newer ships in so novel a type of battle. The old cruiser Brilliant was present, the gunboat Rinaldo, several destroyers, including the Falcon, and on the 27th there arrived the Venerable—the name of Duncan’s flagship at the Texel—a 15,000-ton battleship, mounting four 12-inch and twelve 6-inch guns, which came into action from [63]outside the shoals. French warships acted with the British, and the bombardment extended east to Ostend. The Germans were unable to retaliate. Their big guns did not reach us, and their submarines could not manœuvre in the shallow water, and the torpedoes which they fired, being set at a much greater depth than the monitors’ draught, passed harmlessly beneath their hulls. Our naval guns swept the country for some six miles inland, and the German right was pushed away from the coast. Nieuport was saved, and the German attack on the Yser was possible only beyond the range of the leviathans from the sea.

But the Germans still clung to the coast route, and the Duke of Wurtemberg had now taken command, bringing with him the pick of the Wurtemberg regiments. The Allies, too, had received reinforcements, for General Grossetti had brought up from Rheims the 42nd Division of the 16th Corps of the first line, and was holding the centre opposite Pervyse. The critical period of the attack had beenOct. 23. the days between the 17th and the 22nd, and the British warships had averted that peril. But out of the range of the fleet the German infantry struggled desperately for the passage. On Friday, the 23rd, a body of Germans succeeded in crossing at St. Georges, and forcing their way to Ramscapelle on the railway. There, however, the Belgians drove them back, and that day they gainedOct. 24. no footing on the western bank. On that night, too, no less than fourteen attacks were made upon Dixmude, and were driven back by Admiral Ronarc’h and his marines. Next day another great effort was made at Schoorbakke by the bridge which carries [64]the Pervyse road, and also at a point in the loop of the canal immediately to the south.Oct. 25. About 5,000 men seem to have crossed, and at midnight they held the positions they had gained. On Sunday, the 25th, there was a crossing in greater force, and for a moment it looked as if the line of the Yser had been lost.

But in that country it is one thing to gain a position on the west bank and quite another to be able to advance from it through the miry fields, intersected with countless sluggish rivulets. As the Germans tried to deploy from each bridge-head they were met with stubborn resistance from the Belgian and French entrenched among the dykes. For three days our ragged battalions fought a desperate action in the meadows. Every yard was contested, and the German progress was slow and costly. But even in country where the defence has a natural advantage numbers are bound to tell, andOct. 28. the steady stream of German reinforcements was pressing back the French and Belgians. By the 28th they had retired almost to the Dixmude-Nieuport railway, which runs on an embankment above the level of the fields. The Emperor was with the Duke of Wurtemberg, and under his eye the German attack grew hourly in impetus. Another day, and the Allied left might have been broken.

In this moment of crisis the Belgians played their last card. Once more they sought aid from the water, and, after the fashion of their ancestors, broke down the dykes. The last week had been heavy with rains, and the canalized Yser was brimming [65]to its bank. Under cover of the British naval guns the Belgian left had been hard at work near Nieuport. They had dammed the lower reaches of the canal, and on the 28th achieved their purpose. The Yser lipped over its brim, and spread in great lagoons over the flat meadows. The German forces on the west bank found themselves floundering in a foot of water, while their guns were water-logged and deep in mud. On the few dry patches they kept their ground, but all the intervening land was impossible. The Belgians had fallen back to a position behind the Dixmude-Nieuport railway.

The Inundation on the Yser Front.

Duke Albrecht did not at once give up the [66]attempt. The floods were bad enough, but they were still not impassable. It was clear that the Belgians had larger schemes of inundation, and it became the German aim to win to the railway before these could be put into execution. The obvious point of vantage was the village of Ramscapelle, and the Emperor himself called for volunteersOct. 30. to carry that point. The honour fell to two Wurtemberg brigades, for the soldiers of the duchy have ever been among the best of German fighting men. On the 30th of October, moving from the bridge-heads at St. Georges and Schoorbakke, the Wurtembergers advanced to the attack. They waded through the sloppy fields covered with several inches of water, and by means ofOct. 31. “table-tops”—broad planks carried on the men’s backs—crossed the deeper dykes. So furiously was the attack pressed home that they won to the railway line and seized Ramscapelle. But on the 31st the African infantry of the French 42nd Division and the 2nd and 3rd Belgian Divisions counter-attacked, and after a stubborn battle drove out the Germans from the village, and hurled them back into the lagoons. The Wurtembergers retired from the ruins, and found a position in the meadows where the flood was comparatively shallow.