* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

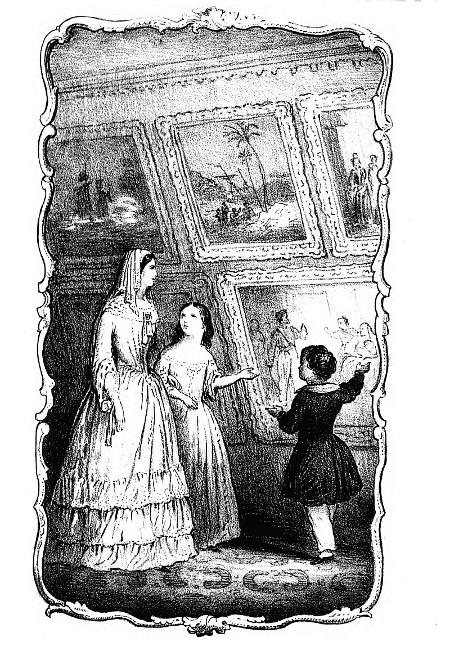

Title: The Orphan Captive, or Christian Endurance

Date of first publication: 1948

Author: Jane Margaret Strickland (1800-1888)

Date first posted: Apr. 22, 2015

Date last updated: Apr. 22, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20150440

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Dianne Nolan & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

PREFACE.

The misfortunes and trials of Mademoiselle de Bourke are not imaginary. At the early age of fourteen, this interesting and high-born young lady was captured, with her mother, the Countess de Bourke, and her brother, by an Algerine rover, within sight of Spain; the Count de Bourke, her father, being then Ambassador from the French Court to that of Madrid.

A second disaster befel this unfortunate family, still more calamitous than the first. They were shipwrecked near Algiers. The Countess, her son, and all her suite, but her daughter, the steward, and her waiting woman, were unfortunately drowned; these individuals and four Turks being the only persons that survived the storm which they encountered. The three Christians were seized by the Caybalot, or revolted Moors, and carried away to the mountains of Cuoco, where they suffered the most cruel slavery, till redeemed by the Fathers of the Redemption, about three years afterwards, being the first Christian captives so liberated by that benevolent order.

In arranging this narrative, the author has closely followed the facts as detailed in "Accounts of Shipwrecks and Disasters at Sea," the old and valuable book from which she has derived them, and to which, with some few exceptions, she has faithfully adhered. She hopes the juvenile reading public will derive both pleasure and profit from the perusal of the trials to which one of their own age was subjected, and which she sustained so well.

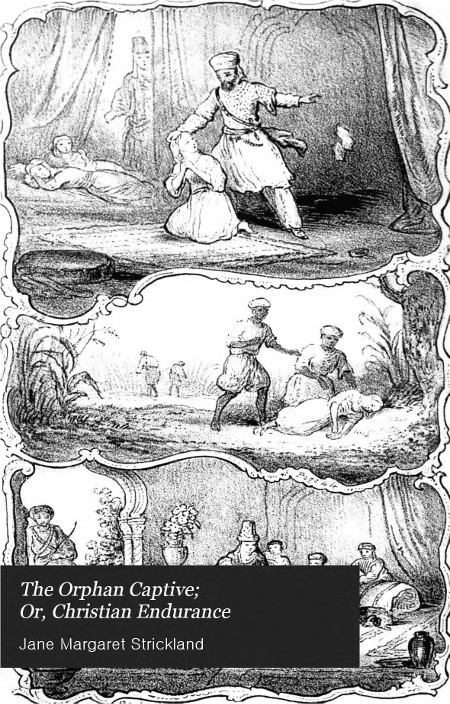

"Grandmamma," cried Adolphe de T----, as he ran hastily to meet the venerable Countess, as she entered the picture gallery, leaning on her granddaughter's arm, "Grandmamma, I have found Adeline's portrait," directing her attention while he spoke to the painting in which he had discovered a likeness to his lovely young sister.

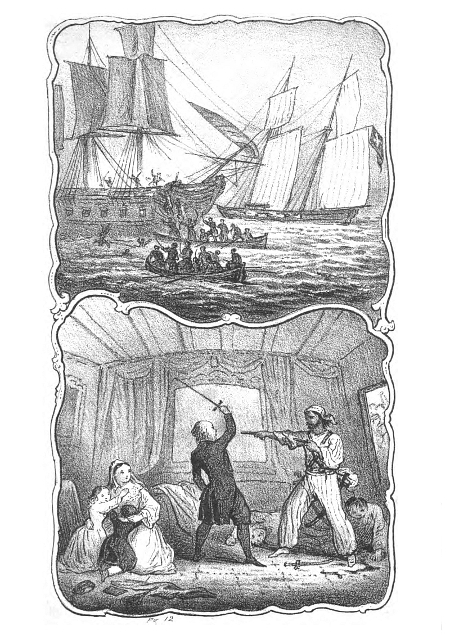

The subject of the painting was the capture of a lady and her family by an Algerine rover, whose commander had just taken possession of the cabin of the Genoese Tartan, and appeared to be addressing some encouraging words, to calm the fears of the unfortunate mother and her affrighted children. The young female, who did indeed bear a strange resemblance to Adeline de T----, was clinging to the maternal bosom, and half covering her eyes to shut out the sight of the sea robber, who had intruded himself into the cabin, at whose entrance more than one faithful servant had perished in guarding their mistress. The boy, resembling Adolphe in features and expression, exhibited something between natural courage and the timidity of his age. One arm was advanced in a bold and even threatening manner, while the other hand grasped his mother's garments with all the instinctive terror of infancy. The painter had happily depicted the dignity of a noble mind struggling with adversity, in the countenance of the lady whose maternal feelings were evidently subdued by the exertion of Christian fortitude. Between the captive family and their conqueror stood a faithful servant, apparently interposing his person to guard them from any insult that might be offered to them on the part of the Corsair. Two female attendants, who were lying fainting on the floor, completed the mournful group.

There was something so inexpressibly touching in the picture, that Adolphe and his sister could not refrain from tears while they looked at it. The Countess wiped her aged eyes,--Adeline felt that she trembled. It was no common emotion that could thus affect her venerable progenitor.

"Adeline," again said Adolphe, but his tone was low, and only intended, this time, for his sister's ear, for he, too, had remarked his grandmother's agitation, but was too delicate to notice it, or even to wish to excite it again.

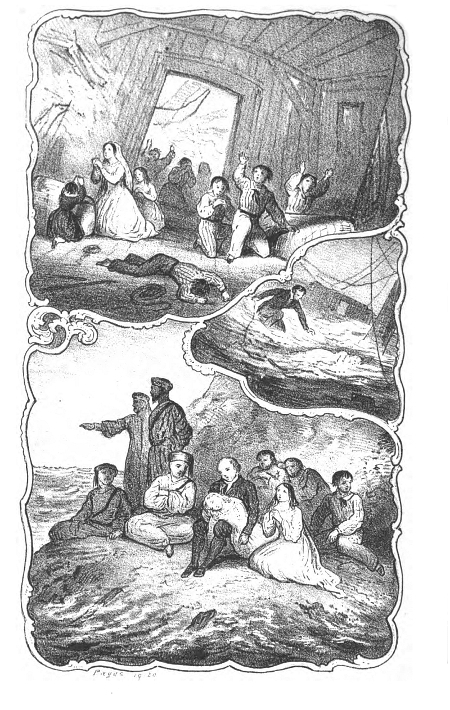

Adeline followed the direction of her brother's eyes, and still saw her own resemblance in a fainting female form, supported by the faithful attendant of the former scene. The first act of the drama was ended, but the second seemed more dreary, more terrible still. A barren rock, surrounded by boiling waves, a sinking ship, a group of miserable half-naked seamen, denoted the nature of the new calamity that had befallen the young creature whose misfortunes the whole series of paintings were intended to represent. It was a face and form of no common beauty that drooped over the servant's arm, the long golden ringlets hung dripping and dishevelled upon her shoulders and bosom, which they partially veiled. Even in her swoon, her mental agony seemed unforgotten. Was she an orphan? had shipwreck, still more cruel than captivity, left her to struggle with her hard fate alone?

The Countess perceived the anxious curiosity of her young relatives; she did not, however, explain, at that moment, the subjects of the paintings. Still holding Adeline by the arm, she advanced to the end of the gallery; she drew aside the curtain, and then quitting her granddaughter, walked to a distant window.

A rocky beach was here represented, a sea covered with wrecks, a savage turbaned groupe regarding a dead female, whose arms still enfolded a beautiful boy.

"Deep in her bosom lay his head,

With half-shut violet eye;

He had known little of her dread,

Nought of her agony."

The daughter, reserved for bitterer trials, was carried in the faithful servant's arms, whose hands passed firmly over her eyes, prevented them from seeing the extent of her misfortunes.

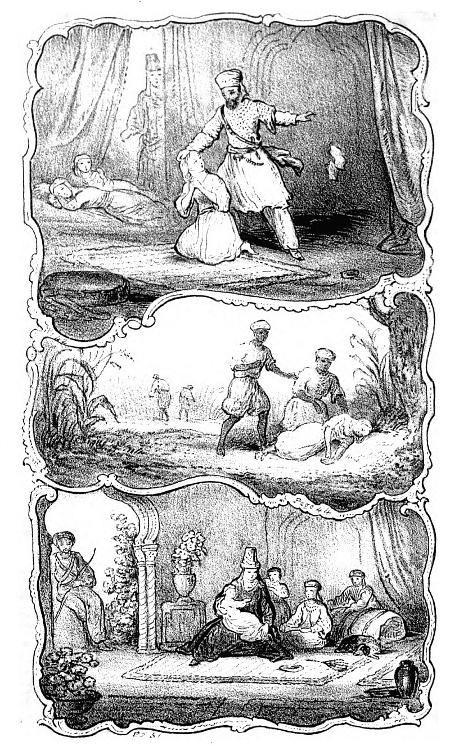

There was yet another picture, which represented the interior of a chapel. Before the altar, the same young female was kneeling, with hands clasped and eyes upraised to Heaven. She was surrounded by a crowd of people, Turks, Jews, Armenians, Europeans, and priests, but seemed unconscious of every thing but her great deliverance. The fashion of her garments were oriental, but her attitude, her raptured devotion, showed that the redeemed captive was a Christian still.

"These paintings, my dear children, represent only too faithfully the history of my early life," said the Countess, advancing to meet her grandchildren. "I was young and fair as Adeline, when these adventures befel me; but the arm of the Lord succoured me. He brought me out of the land of bondage, and restored me to my father and country again."

"I think I have heard nurse say that you had been a slave in Africa; but, dearest grandmamma, she never told me the particulars," replied Adeline.

"She did not know them, my dear child, and you have been brought up at a distance from me. However, if you wish to hear this disastrous narrative, I will endeavour to recall even the minutest incident. I am now in extreme old age, but the leading events of my captivity are as fresh in my memory as if they only happened yesterday."

"Then you will tell us the whole story," cried Adolphe. "Ah, now I know why your pictures are like Adeline; how I long to hear all about your captivity, dear mamma."

The Countess led her young descendants into her boudoir, whose windows overlooked the sunny fields and vine-clad hills of her own beautiful Provence, and seating herself beside them, contemplated them with the affectionate smile of a doting grandmother, commenced her history in these words--

"My father was, as you already know, of Irish descent, but ennobled, by the French monarch, for his military and diplomatic services. The Count de Bourke, for such was his title, had been some years Ambassador at the Court of Madrid; but my mother and her family, consisting of myself and a young brother, lived with my grandmother, Madame le Marquise de Varenne, at her chateau, not far from Aix. The troubled state of the Peninsula, and the delicacy of my health, had hitherto prevented mamma from joining her lord; but when I was near thirteen, I grew healthy, and all obstacles being happily removed, she determined on joining the count, who was anxiously expecting her arrival at Madrid.

"A Genoese Tartan, handsomely fitted-up by government, was appointed to convey us to Spain. We embarked at Marseilles, whither my dear grandmother, Madame Varenne, and my uncle, the Marquis, accompanied us. Taking leave of these dear relations was the first sorrow I had ever known. I had not seen my father since the birth of my brother, and the kind Marquis had always supplied his place to me. Madame Varenne was the kindest and most indulgent of all grandmammas, and the tears I then shed in her arms were the only bitter ones that had ever fallen from my eyes. We embarked with a fair wind, the waves danced and glittered in the sun, reflecting the deep blue of the clear cloudless heavens above them. The bustle on deck, the novelty of the scene around us, made my brother and myself forget our childish grief. Mamma smiled too, through the soft tears that stood in her beautiful eyes, for she was hastening to meet the husband of her choice, and to present his children to him. Her sweet face resembled, at that moment, an April sky; even at this distance of time, I recall her to my mind, lovely and amiable as she then appeared. Yes, best of mothers! your image is still bright and fresh in my memory as ever, as we stood, hand in hand, gazing upon the receding shores of France!

"We suffered no inconvenience on the voyage as yet, all was fair and prosperous. The magnificence of the state cabin, the homage paid us as the children of the Ambassador, quite turned our young heads; and when the cry of 'land, land,' met our ears, we ran upon deck quite wild with joy. Here we were joined by mamma, and as we could see the coast of Spain with the naked eye, and even inhaled the perfumed breezes from the shore, we all naturally concluded our voyage was nearly at an end. At this moment a second cry chilled our hearts with terror. 'A Corsair a-head! a Corsair a-head, bearing down upon us!'

"I clung to mamma; Adolphe was less alarmed; though little more than six years old, he was a bold little fellow. 'Come, leave off crying, Victorine, we will fight the ship. Marèchal Berwick gave me a sword, I will run and fetch it to defend you.' Mamma gently detained the brave child, and wiping the tears from my eyes, bade us 'be assured that, within sight of shore, no Algerine rovers dared attack us.' Jaques M----, the steward, told us the same thing, and I became more calm.

"The appearance of two armed Turkish rowboats destroyed our fancied security, they rapidly approached the vessel, leaving us no other alternative than death or slavery. I withdrew with mamma and my brother into the state cabin. Ah, how gladly would we now have exchanged all its magnificence for the poorest hut in Spain or our own beloved Provence!

"The contest was short, the navigators of our unfortunate vessel threw themselves flat upon the deck, to avoid the broadside poured in by the enemy. The domestics, mostly grown old in the service of my grandfather, vigorously, though vainly, defended their lady and her family. Never shall I forget the noise, the cries of triumph, or of execration, carried on in various dialects, the terrific sound of the fire-arms, the groans of the wounded and dying, which then stunned our affrighted ears. My mother, always pious, passed these dreadful moments in prayer; I repeated the words she uttered, without having any distinct idea of their meaning, so bewildered were my faculties with terror. A momentary silence ensued, and then a wild barbarous shout announced our captivity. Another instant and the combat was renewed at the door of the cabin, which was burst open with violence, and the bodies of two of our defenders rolled in, the steward rushing in at the same moment with the captain of the Algerine rover, with matchless fidelity stood between his lady and the infuriated barbarian, resolved to defend her and her children to the last drop of his blood.

"This scene, my dear children, is the subject of the first picture of the series you have just been contemplating. Jaques M----, was the faithful steward represented in the painting, my preserver and guardian in my painful captivity.

"In the wreck of all her hopes, in the midst of this slaughter, my dear mother evinced a courage that was not of this world, the fruits, indeed, of her late communion with God in prayer. While with a look she tried to soothe my fears, she drew back my brother's advanced arm, and then, turning to the barbarian chief, she signed to the steward to deliver up his sword, and by her gestures seemed to demand that respectful treatment her high rank required. Whether the richness of her dress, her beauty, or the dignity of her behaviour, influenced this barbarian, I know not; but certainly he gave us very civil treatment, laying his sabre at our feet, which, but a moment before, was uplifted to take the steward's life, and by salaming very low, gave promise of behaving more courteously than we could expect from one of his creed and nation.

"My mother, who spoke Italian fluently, now remembered that it was probably understood by our captor, as she had heard, it was frequently used as a means of communication in the Levant. She addressed him in that language, and found he could converse in it with readiness. He used, to be sure, many words my mother could not understand, intermingling with it a barbarous patois, called Lingua França; but the steward, who had been up the Straits in his youth, comprehended him without difficulty, and interpreted these phrases to his mistress.

"Mamma discovered to the Corsair her name and rank, and demanded to be sent on shore. She pleaded the rights of nations, and assured him that her quality of French Ambassadress must render her capture as dangerous as it was unlawful. She then offered him a large ransom, on condition that he landed her on the coast of Spain or France, and concluded, by showing her passport, which ought to have secured her from any attack of this kind.

"In reply, the infidel told her he was the Dey's servant, and dared not act against his master's authority, but must instantly convey her and her family to Algiers.

"My mother changed colour, her spirits sank, she began to weep. The barbarian was touched by her tears, he assured her that she had nothing to fear; he even gave her the chance of remaining on board the Tartan, or of accompanying him to his own vessel. He advised the former, and mamma followed his advice by staying where she was. The unfortunate Tartan was then manned by Turks, and her course altered for Algiers.

"It was a great consolation for mamma that the steward remained with her, for Jaques M---- was one of the best men in the world, uniting a clear sound head to an excellent heart. He consoled her, by stating 'the probability of a re-capture before the Tartan reached Algiers; and the probability, even if they were not so fortunate, that the Dey would not dare to detain an Ambassadress from a powerful Christian court, to another equally potent.'

"We were within a few hours' sail of Algiers when a furious gale sprang up, which divided us from the Corsair. We were soon, either from the ignorance of our navigators, or the violence of the storm, driven out of our course; and, to use the expressive words of the holy apostle, 'were in jeopardy.' Whether a presentiment of approaching death, or the dread of separation, weighed most heavily upon my mother's mind, at this period, I cannot determine, but she began to give much maternal counsel, mingled with many tears. 'Victorine,' said she, 'I have hoped all along that some unexpected deliverance would arise; but now I feel an assurance in my own mind that either death or long captivity awaits me. We may be separated, and you deprived of a mother's guardianship, be thrown among infidels, who will mock your Saviour, and endeavour to seduce you from the Christian faith. You are young and thoughtless; you have, perhaps, never seriously reflected upon these great truths you have known from your cradle. Now is the time to lay them to heart. Keep them, my darling girl; and though slavery, persecution, and even death await thee, thou wilt be happy hereafter; but forsake Him who died for thee, and shame here and future retribution will be thy portion. Yes, Victorine, the portion of the apostate is everlasting woe. God will, I trust, preserve thy honour; but thou art too young and fair for the barbarous land, whither thou art carried a slave. Still, dear Victorine, I feel assured that thou wilt not forget thy Saviour; but this child is yet in infancy, and when I reflect upon what he may become, I confess I would rather hold him dead in my arms than see him a renegade slave.'

"I could not speak; the idea of being separated from my mother had never entered my mind; the thought agonized me, I threw myself upon her bosom, and burst into a flood of tears. My brother caught up her last words.

"'Am I really a slave, mamma?' asked he, 'and will these wicked Turks carry me away from you, and put chains on me? Why, what will papa do to them when he finds it out? What will he say when he hears what has become of us? And will they take me and Victorine from you?'

"This innocent prattle overpowered my mother, she caught us both in her arms, and shed over us those tears affectionate parents only pour over their offspring, 'My children, oh! my children,' she murmured, 'what will become of you and your father; oh! who shall tell him of our fate!' These complaints were the first and last I ever heard her utter. 'Thy will, O Lord, not mine, be done,' was the prayer that rose instantly to her lips, so completely did faith enable her to gain the victory over the infirmities and tender weaknesses of human nature. This agony of maternal solitude quickly subsided; calmer, holier feelings succeeded. She submitted herself wholly to the decrees of God.

"Towards the evening of the third day, the furious gale rose to such a tremendous height; that no hope remained that the ship could weather the tempest. Our captors chewed opium, and resigned themselves to their fate. They struck off the irons from the limbs of their prisoners, and intrusted the navigation of the labouring vessel to them once more. We were moved into the stern cabin, for what reason I could never determine.

"I was so much distressed by sea sickness, that I was obliged to keep my bed; my brother was no less affected than myself. My mother, I see her yet, as, with the warning voice of an angel, she cried to her terrified household, 'Watch and pray; for ye know not the day nor the hour when the Son of Man cometh.' As she knelt down, the terrified females clinging to her garments, the men prostrate in the humblest attitudes of devotion, she prayed aloud in the behalf of those present, with a fervency that seemed almost like inspiration. All appeared to feel that they were about to enter another world, upon whose portals they were kneeling. A cry so wild, so despairing, here broke in upon us, and then a shock, a violent, tremendous shock, followed,--the ship had struck upon the rocks. Springing from my cot, and seizing my brother, we rushed to mamma, who folded us tightly to her bosom; her arms were wound around us, I heard her say, 'Even so come, Lord Jesus!' Those words were her last. The ship parted in two, and the whole stern sunk; the water poured in, and divided me from my beloved parent for ever."

Madame de T---- here became much agitated, and it was some minutes before she could resume her narrative; nor were her young auditors less affected than herself. Indeed, how could it be otherwise? the tale was true, and their venerable ancestor the victim of these almost unprecedented calamities.

"Even at this distance of time, my children," continued the Countess, "I cannot recall the remembrance of that fatal night, without extreme pain. The rushing in of the strangling waters deprived me of sensation; of what immediately followed, I have no recollection. It seems that a gentleman attached to our suite was on that part of the vessel which was thrown high upon the rock. He distinguished something floating near him, and supposing, by the white garments, that it was a female, endeavoured to save me. He succeeded, though not without emperilling his own life. Poor gentleman! he lost it a few minutes after, in trying to swim ashore.

"This is the history of my wonderful preservation, which I learned, some hours after, from the faithful Jaques, who, fortunately for me, was one of the seven survivors on the rock. When I recovered consciousness, I found myself in the steward's arms, my only raiment my night-dress, my slippers still on my feet, my head uncovered, and my long ringlets hanging over his arm, wet and dishevelled, as represented in the painting. Cold, hungry, wet, half naked, and sick with grief, I passed that dreadful night in successive fainting fits. It was only at intervals I had my recollection, and then I wished to die. I murmured, I fretted against that awful Providence who had appointed me to these trials.

"The steward chid this rebellious spirit; he reminded me of my sainted mother's patience, of her faithful acquiescence to the decrees of the Almighty. I wept till I could weep no longer, but I dared not now repine. My mother's example spake to me, even from the grave.

"The long-wished-for, yet dreaded morning, came, bringing with it fresh misfortunes. We were within sight of Algiers, one of the finest cities in the world for appearance, as we viewed it from the water. The shipwrecked Turks made signals of distress, and awaited the expected aid from the shore, with far different feelings than the unhappy Christians, who looked forward to nothing but chains. The party on the rock consisted of four Turks, one of whom was the commander of the corsair, and three natives of France, the steward, myself, and Fanchette, my own maid. Several boats approached us from the shore, the foremost of which seized all the prisoners; the others began to plunder the wreck, but all left the Turks to shift as they could.

"The wild, savage-looking people into whose hands I had fallen, called themselves Cabayles, or revolted Moors; they resided in the lofty mountains of Cuoco, under the government of their own Sheik; and, safe amidst those wild crags and cliffs, resolutely maintained their own independence, in defiance of the Dey, and the whole power of Algiers. The Sheik, or chief, of these wild hordes, exercised the authority of a barbaric king over them. That is, he led them to battle, and provided for the exigencies of the horde or tribe; but over their savage actions he had no control. The high priest, or Marabout, as he was called, was their lawgiver, but he was obliged to wink at the infringement of his laws; and as they implicitly followed his superstitious tenets, he did not care how much ill-will they showed to each other, or attempt to ameliorate their cruelty to their miserable captives.

"As soon as we reached the shore, the person who appeared to be the leader of the party, took me from the steward, and pulled off one of my slippers, in token that I was now his slave. Jaques made signs to him to treat me kindly; and gathering up a double-handful of pebbles from the beach, repeatedly pointing to me, intending to convey to my master some idea of the great ransom he might obtain for me. My captor nodded in return, and seeing that I required food, gave me some bread, some dates, and a bottle of water. He then restored me my shoe, and we commenced our march towards the mountains.

"For some time, our route lay along the sea-beach, which was strewn with the mournful memorials of the wreck. In an agony of grief, I examined the lifeless features of the dead, expecting to behold the dear loved remains of my mother and brother. Many a well-known familiar face met my view, but not those I sought for. My preserver lay cold and lifeless there; and how sorely did I long to throw myself down beside him, and give up the life he had prolonged, which seemed, at this bitter moment, an intolerable burden. On my uncovered head the burning rays of the noon-day sun shone with unmitigated fierceness; my feet were blistered, my spirit was overwhelmed, fearfulness and trembling came upon me. The steward saw the fatigue and anguish I endured; he took me up in his arms; he comforted, he consoled me; he spoke of my father, and bade me try to live for him. The good man wept over me; he was suffering hunger, thirst, and toil; but in tender sympathy for me, he evidently forgot his own misery. Excellent man, how do I love and venerate thee! how dear is thy memory to me still! My eyes, long dimmed with weeping, could then scarcely distinguish even near objects; well was it for me, that they did not behold the cruel sight that must have met them, but for the precaution my kind friend took.

"At a distance from the other victims of the last fatal night, lay my beloved mother and brother. Her arms were wound round him, his head was nestled in her bosom; death had not divided them; the flower and the bud were frozen together, in the icy clasp of death. The separation she had dreaded, had not taken place,--the lamb of Christ's fold was gathered unto the Great Shepherd, together with his Christian parent. A shriek from Fanchette, a yell of eagerness and triumph from the savage Moors, raised my feeble energies; I tried to raise my head to discover the cause of these outcries; but the steward passed his hands firmly over my eyes, and saved me from the horror of that sight. How could I have seen the rings torn from those lovely hands, that beautiful face rudely examined, those insensible remains insulted and defaced, and lived or retained my reason! Happy spirit! what were these outrages to thee? Thyself and thy child were then with God, singing the song of the redeemed, and rejoicing in His light, with whom is no variableness, neither shadow of turning."

The countess was again dreadfully agitated; for a few moments her feelings appeared to overpower her; but she soon collected herself, and resumed her narrative.

"I did not learn these particulars till some days afterwards, when they were told me by Fanchette, who disguised nothing from me, but told her tale with a frightful minuteness that harrowed me to the soul. It was only in the first days of my journey, that I bitterly lamented the death of my sainted parent and cherub brother. Alas! the barbarous usage I endured in slavery, soon made me remember, with gratitude, that they were spared the miseries I underwent.

"We at length turned our backs upon the sea, and began to ascend the rugged heights that led to the mountains, whither our master intended us to sojourn for a time. His own home lay at a large town, called Bujeyer, where he finally intended to sell us, if he could not obtain a sufficient ransom for our persons. The sheik to whose care he meant to intrust us, was a covetous, uncivilized barbarian, who no sooner saw us, than he picked a quarrel with my master, and laying hold upon me, insisted that the booty he had got from the wreck, was more than his share, and that the prisoners should be for him. The enraged Moor swore that I was a Spaniard of high rank, and that, rather than give me up, he would cut off my head. He drew his sabre, and catching me by my long hair, would certainly have put his threat into execution, if the faithful steward had not seized his arm, and made signs that by so doing he would lose my ransom. The incensed Moor dropped the weapon, and finding that the party of the sheik was far more numerous than that he commanded, collected his goods and followers, and took the way to his native city, leaving us in hands far more barbarous and uncivilized than his own.

"For six days we pursued our toilsome way, till the steward told me we were near our future home. Home! the slave has no home; but this sad truth I had yet to learn from the bitter teaching of experience. Worn with incessant toil, I pined for rest, and almost participated in the joy that lighted up the savage countenances of the sheik and his followers.

"With the name of woman, every thing tender and endearing was combined. They had children, and could feel for one thus early deprived of a mother's care, a mother's love; I did not know that a debasing slavery and intolerant religion deprived the female savage of every softer feeling, leaving her little of her sex but a fierce kind of maternity. Yes, dear Adeline, it is to the Christian religion we owe all our attractive qualities, all our privileges; wherever the gospel is not preached, woman is an abject slave, often as wicked as she is helpless. But to resume my tale: Fanchette, no less sanguine than myself, comforted me with the prospect of obtaining rest and refreshment. Poor girl, she paid me the same attention now I was a fellow slave with herself, as formerly when I had a right to command her services. The steward's information was quite correct, (he had it from an Italian renegade slave belonging to the sheik,) and towards evening we entered the hamlet, where our new master's family dwelt.

"The whole population, headed by his wife and children, came out to meet him with songs of joy and triumph, and to mock the Christian captives he had brought with him. The women, from whom I had hoped to find some compassion, loaded us with insults and abuse; they set their great dogs upon us, and laughed at the agony of terror Fanchette and I were in when these monstrous beasts fastened upon us, and made us feel their fangs. The name of Christian seemed to extinguish every spark of pity in their flinty bosoms. They pointed to their large fires, with gestures that showed them to be desirous of putting us to a cruel death. Indeed, these women seemed to hold the female sex in contempt, for they confined their malice to Fanchette and me, contenting themselves with spitting in the steward's face, calling him hard names, and throwing him some bones to pick, thus reducing him to the level of their dogs. They pinched, and harrassed us so cruelly, that we were ready to die with fatigue and terror.

"The steward, who saw my great distress, pointed it out to our new master, who put a stop to the cruel sport, by commanding the principal instigator, his own wife, Gulbeyaz, to conduct me to her residence, and to give me something to eat.

"This haughty woman, who was handsome, and rather majestic in her person, gathered her garments tightly round her, as fearing some contamination from my touch, and made signs to me to follow her to her dwelling. She pointed to a mat in a remote corner, in which I sat down, and taking some raw parsnips from a basket, flung me the green tops, laughing heartily at my evident disappointment. Fatmè, her daughter, a pretty girl, of my own age, joined in her mother's cruel mockery. Heart-sick and weary, I closed my eyes, and fell asleep.

"Early the following morning, I was awakened by feeling my long hair pulled, and found myself assailed by five of my mistress's impish progeny, who pinched and scratched me unmercifully. Enraged at this usage, I shook the children rudely off, and sent them roaring to their mother, who flew upon me like an enfuriated tigress, and left me fainting from the effect of her blows.

"When I recovered my recollection, the sheik and his family were taking their morning repast; Fanchette and the steward were sitting eating some black bread, at a humble distance, casting from time to time looks of tender compassion upon me. The sheik ordered Fatmè to give me a little milk and water, and a barley cake: she was forced to obey his commands, but she rudely spit in my face, to show how averse she was to offer me the common offices of humanity.

"My scanty meal ended, Gulbeyaz sent me, with two of her slaves, to draw water from a neighbouring well. And now, my dear children, I displayed a want of sense, in trying to evade the duties of my new situation. I had been delicately brought up, and had never even dressed myself, washed my own hands, or indeed performed those little offices for myself which even young ladies of quality should be accustomed to do. You, Adeline, at my request, have been educated more usefully, and are quite independent of your waiting woman; but my helpless hands were now called upon to perform servile work for others, which had disdained the lightest toil for my own advantage. I refused the task allotted to me with passionate indignation; I hoped to provoke my captors to destroy me, so much did I long to escape, by death, from the life of bitter bondage that awaited me. Fanchette seemed determined to assert her dignity as lady's maid, with as much obstinacy as her young mistress did that of a nobleman's and ambassador's daughter. The consequences may be easily guessed, we were beaten, starved, and at night turned out of the hut, exposed to the noxious dews, and fierce attacks of the muskitoes."

"Why did you not try to escape, dear grandma?" asked Adolphe.

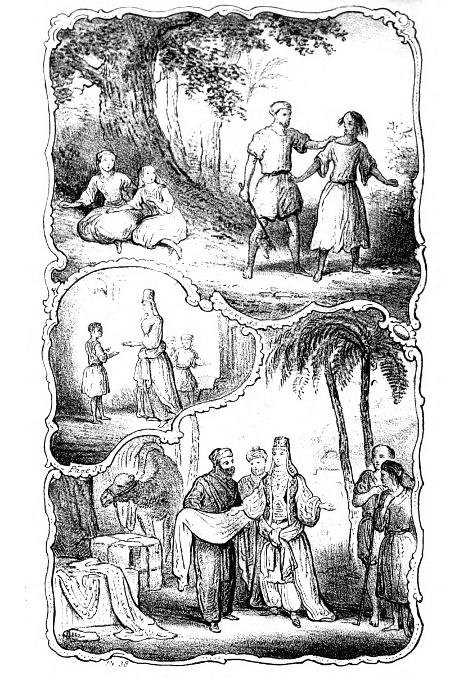

"Alas! whither could we flee, my child?" replied the Countess; "and indeed, if we were so inclined, dogs followed us wherever we went, ready to seize us in their fangs, if we strayed beyond the limits of the hamlet. At first, we wandered about in great affliction, wringing our hands, and speaking of the lamented dead, and of that dear France we dared not hope to see again. While indulging our grief, we came suddenly upon the steward, who was at prayer, under a tree. Our sobs disturbed his devotion, he arose from his knees, and came to meet us. The brilliant moon shone full upon his countenance, a holy calmness seemed to rest upon his brow; his whitened hair, blanched in the service of my family, denoted a green old age; his strength was still as unbroken, his head as cool, his heart as warm as in early youth. As he advanced towards us, he reminded me of the saints and martyrs of primitive times. He bowed respectfully to me, and addressed me thus,--'Mademoiselle De Bourke, my dear young lady, it is for you I have been praying: how is it that I find you here, and in such trouble?'

"I sobbed while I related the cause. He shook his head, and turning to Fanchette, sharply reproved her: 'this poor child does not see the consequences of her rashness, and she knows not the use of her delicate hands; but you who were taken from the sheepfold and the vineyard to wait upon her, only return to labours to which you have been accustomed. Poor Victorine, poor child, you must subdue this rebellious spirit,' continued he; 'you must endeavour to perform the tasks imposed upon you in this house of bondage, for in so doing you will fulfil the will of your Heavenly Father; He has appointed you to these trials, and He can help you as He did Joseph in Egypt; He can be with you, as He was with him. Dry up your tears, my child, and pray with me for submission to the Divine will; to-morrow, set about your labours diligently, as performing them, not unto man, but unto God.'

"I motioned to Fanchette to kneel down by me, my heart was too full to speak. The old man prayed in the fulness and deep sincerity of his heart for me, and with me. He spake of a Saviour's love; and besought Him to deliver us, as He had all His servants, who called upon Him in the hour of their extremity.

"Young as I was, and self-willed as I was, the prayers and exhortations of this good man sunk deep into my heart. His example encouraged me; I began to think of that Heavenly rest, which was yet in store for the slave; I promised to follow his advice; I called him my father, in truth, he behaved like a father to me.

"Seeing how matted and dishevelled my hair hung about me, (for I had lost all my clothes and necessaries in the shipwreck,) he gave me his pocket-comb, and with the assistance of Fanchette and his knife, reduced my refractory ringlets into something like order. He comforted me by assuring me that if it were possible to acquaint the French consul, at Algiers, with my situation, I should not remain long in this doleful captivity; adding that, among the followers of the sheik, there was an Italian renegade, who had promised to convey a letter to the consul, the first opportunity that might occur. The good man then took an ink-horn from his pocket, and his account book, which articles he had been permitted to retain, because his captors knew not their use, and advised me to add a few lines to a letter he had already written on a blank leaf he had torn from it.

"My dear grandchildren will wonder how I acquitted myself of this task at midnight, but I was aided by the light of a brilliant moon, whose beams shone with unclouded splendour, almost blinding me with their brightness. Indeed, the words of the Psalmist are beautifully applicable when remembered in a climate like that in which I was then a sojourner: 'The sun shall not smite thee by day, or the moon by night,'[1] as any person sleeping with their faces uncovered in the open air exposed to the moonbeams, run the risk of blindness. Sitting under a tree, and resting the book on my knee, in lieu of a desk, I corroborated the steward's statement, and implored Monsieur Dusault to inform my father of my present condition, if he would not venture to redeem me himself."

|

Sir Robert Kerr Porter quotes this verse of the 121st Psalm, in speaking of the effect of moonlight, in Egypt,--See his Travels. |

"My task executed, a spark of hope sprang up in my heart, and after committing myself to the care of Heaven, I rested my head against the bosom of Fanchette, and slept for some hours sweetly and profoundly. A strange incident, as unexpected as it was frightful, nearly consigned me to that deeper slumber which the coming of the Lord alone can break. A fanatical wicked old woman, tormented by the evil workings of her own conscience, imagined that the murder of a Christian would atone for some of the enormities of her former life, and, haunted by the recollection of some ancient crime, wandered about at some seasons like a fury, armed with a hatchet. Among the Mahometans, the insane are held in great reverence, and all their sayings are considered as oricular; for which reason, this creature (who, I believe, was mad from wickedness) was suffered to be at large. While roaming abroad, she perceived me lying on the bosom of Fanchette; and, catching me by my long curls, was about to strike off my head, when my cries brought the steward to my assistance, who shook the vile old woman violently, seized her hatchet, and drove her away.

"Thus through his courage, promptitude, and fidelity, was I a second time preserved from decapitation. I could not help weeping while I directed Fanchette to cut off my hair close to my head, with the steward's knife, for how proud had my dear mother been of these fine golden ringlets, which she loved to dress herself! and how often had my dear lost Adolphe sportively threaded them, and even kissed them with infantine affection. Now, to retain them, was to risk my life, since they had afforded a secure hold to two assassins within a few days. Yet I childishly wept when I saw them lying on the ground, and felt as if I could no longer identify myself without them.

"I promised the steward that I would endeavour to perform the tasks allotted to me, for hope again waved her golden pinions round my head. The consul would receive my letter, and I should be free. The assembling of the sheik's household was destined to renew my grief. The sight of my close-cropped head enraged the barbarian, who struck me several hard blows; for the females, among the Moors, account their long hair as their greatest ornament, and the loss of mine would greatly diminish my value, were he inclined to sell me. The women mocked me, and the children hooted me, Gulbeyaz contented herself with holding up a bright tin mirror, which she wore suspended to her girdle, with an air of quiet malice, which vexed me more than the taunts and laughter of the rest.

"I had been considered one of the loveliest girls in France, and was by no means unconscious of my personal charms. The sight of my own reflection in Gulbeyaz's mirror, was sufficient to cure me of vanity for ever. It was no longer Victorine De Bourke I saw, but a young creature as black as a gipsey, with naked feet and legs, a man's waistcoat fastened round her waist, no hat, and bright golden hair clipped, or rather notched round her face, and large blue eyes staring out of a famished, affrighted countenance. Yet so rediculous was my appearance, that I actually laughed; perhaps the remembrance of what I was, and what I had been, excited this unnatural resibility; but there was no pleasure in my mirth. I forgot to tell you that my upper garment was furnished by the steward; it was fastened with a hemp cord, because the sheik had taken a fancy to the buttons.

"Gulbeyaz was so charmed with my mortification, that she gave me some bread and milk for breakfast, and sent me, with Fanchette and a male slave, to draw water, I conscientiously endeavoured to keep my word, so solemnly pledged to Jacques; but the fatigue was dreadful, and my face and hands were terribly blistered by the sun; I had no bonnet, and now doubly regretted my long hair, which had hitherto defended my neck and face from the heat. Faint and exhausted, I sunk down by the side of a palm tree, that grew near the fountain. Here the steward found me, and taking his handkerchief off his neck, tied it round my head: he gave me some berries which he had found, that were edible, told me that the renegado had dispatched our letter to the consul, congratulating me on the prospect of speedy deliverance, and bidding me be of good comfort, Surely, my dear children, this man was like a second father to me.

"In the evening, we were employed in milking the goats. Fanchette, who could milk, undertook to teach me. We secretly drank some of the milk, when Gulbeyaz's back was towards us, and felt all the better for our repast. As the kids had only that day been taken off two of her best milch goats, our mistress did not suspect us, but thought the creatures held up their milk from affection to their young. Fanchette, who was a farmer's daughter, was, however, too well versed in rural affairs for this to happen with her. We began to recruit our strength a little, for if we had not lived upon our wits, we should have been literally starved. The worst part of slavery is the dishonesty and immorality it occasions. Necessity made me steal, but I had too much fear of God before my eyes to lie, Fanchette was less scrupulous. Ours was a hard lot while together, but, alas! mine was soon rendered more bitter by a separation from these faithful servants, who had held by me in my evil days as in my happier ones.

"The arrival of a strange merchant, with coffee, spices, shawls, silks, opium, and pipes deprived me of these worthy creatures. Gulbeyaz took a fancy to a superb shawl, and, with the permission of the sheik, exchanged Fanchette and the steward for this piece of finery. We had been, now, two months in these mountains, and had acquired a smattering of the barbarous Moresco these people spoke, and but too soon understood the nature of this cruel bargain. For the two individuals principally concerned, any change was for the better. The merchant looked mild, and intelligent, and more like a civilized being than any thing I had yet seen in Africa. But, for me, their departure was a calamity bitterer than death. I forgot all differences between our rank, while I hung weeping round their necks, in an agony of despair. The steward wept over me, and blessed me; he gave me his ink-horn and account book, (which I put in my bosom,) charging me to keep sending letters to the French consul, till I received an answer; telling me to confide in the Italian renegade, who would keep sending them to Algiers by persons travelling thither. He exhorted me to be patient and tractable, and to endeavour to gain the friendship of the wild people with whom I was a slave. 'I have not been ill-treated, my dear child, because I have lent my shoulder to the wheel, and, forgetting my former condition, looked before me, instead of behind.--This, dear and beloved daughter of my sainted mistress, you must do, if you wish for kind treatment. Even in this wilderness of woe, God will be with you, as He was with Joseph in all his afflictions. Cleave fast to your Saviour, without wavering; and, following His example and commands, 'pray for them that persecute you, and bless them that curse you, and despitefully use you;' so shall you become a child of God, and inheritor of that kingdom where there is no slavery, no tears, no separation from those we love.'

"To these words I made no reply but these words, 'I shall be left alone--alone, with savage Pagans,' wringing my hands, and clinging fast to those humble but faithful friends, whom I believed I should never behold more.

"The steward solemnly blessed me, and again entreated me to be comforted, but my choking grief prevented me from hearing his last words, or taking a last look at him and poor Fanchette.

"Suddenly, a strange ringing sounded in my ears: a mist came over my sight. I lost all sensation, even that of sorrow; and when I recovered consciousness, they were gone, and I was alone.

"I cannot describe my feelings. I mechanically obeyed those about me, ate the coarse food they gave me, without appetite, drank without thirst, and moved about without any aim, excepting the impulse given me by those who were in authority over me. I ceased to pray. I was sinking into a state of apathy, almost of idiotcy, when I was accosted one day by the renegade, through whose means I had hoped to regain my liberty. He told me that he feared the letter he had entrusted to a fellow slave had miscarried, and advised me to write another. The sound of my own language, for he spoke to me in very broken French, roused me from the stupor of despair into which I had sunk. I wept, I acknowledged my ingratitude in forgetting that God, who still cared for me, and thanking my fellow slave, resolved to write to the consul that very day. No opportunity occurred till the family of the sheik were buried in repose. I usually slept on a mat near Fatmè's bed, and the rest of the sheik's progeny occupied the same apartment; a thin partition divided us from that occupied by my master and the ever-watchful Gulbeyaz, attentive to the least murmur uttered by her young.

"At midnight, I crept from my mat, and taking out my writing materials, aided by the light of the moon, commenced my task. The narrative of my misfortunes took some considerable time to indite. I had not been used to letter writing, and actually took more pains to make my hand look neat, than the necessities of the case required, so that it took me several nightly vigils to complete my task. At length, I happily concluded it, and having actually folded and superscribed it, was putting it into my bosom, when I was seized from behind, and turning round, beheld the sheik, who shook me violently, snatched it from me, and, worse than all, took away my writing materials. Then, taking me up in his arms, flung me violently on my mat, and retired grumbling to his own bed.

"This barbarous chief was very far from guessing the true use of the implements of which he had deprived me. Ignorant of the art of writing, he thought that the black marks I had made on the paper was a charm, to do him or his family an injury; and, carefully laying the letter and materials by, determined to wash out the writing very carefully, and make me drink it, to avert the mischief he imagined I wished to do him. This he accordingly did the following day, to my great distaste and mortification.

"He, however, gave me an opportunity of writing another letter, by desiring me to write a charm to wear round his neck, to prevent the assaults of the devil, of whom he was, with very good reason, much afraid. I took as much time about this charm as I possibly could, taking care to write two letters to the consul at the same time, one of which, I entrusted to the care of Murad, (as Marco Monti, the renegade, was called,) concealing the other in my bosom, in case the first should miscarry.

"My master was so much pleased with his charm, that he gave me a suit of coarse blue cotton, and promised me a turban, in case I should behave myself. I could scarcely refrain from laughing when I beheld the sheik suspend the writing round his neck, it being literally nothing more than a rough copy of the narrative of my own misfortunes, such as I had just given into Murad's hands.

"The sheik was so pleased with my performance, that I began to fare better for the authority with which superstition had invested me, when the return of Aladin, the eldest son of my master, was the occasion of fresh disasters to me, and more dreadful trials. This young savage, who had just attained to manhood, had already signalized himself by his great courage. He inherited a good deal of his mother's haughty character as well as her fierce beauty; and being lately returned from a military expedition against another wild tribe, was much extolled and humoured by his parents and people.

"Unfortunately for me, this youth took a liking to me, now fast stepping into early womanhood, and a still greater fancy for the handkerchief I wore round my head, which he insisted upon having. No other head covering was given me in its place; and though I reminded the sheik of his promise of a turban, or a veil, he refused to supply my loss, or to force his son to restore what he had so unjustly taken away, which was the pretty India handkerchief given me by the faithful steward. In France, the loss of a bonnet, or cap, is a great inconvenience; but in Africa, a dreadful deprivation. I was obliged to assist the male slaves, that day; in harvesting the maize crop; and, suddenly, was struck to the earth with a coup de soleil, fainted, and was carried home in a burning fever. The ignorant and inhuman sheik, as soon as he saw me, instead of considering my illness as the result of working bareheaded in the sun, imputed it to my having swallowed the water with which he had obliterated my former letter, which, you may remember, he took for a charm to bring some calamity upon his house, which had now, as he thought, returned upon my own head, by his prudent management. He imparted his suspicions to Gulbeyaz and his household; and the consequences of this absurd conjecture was, that I was left to shift for myself, or perish with hunger. By his direction, I was laid under a large tree, to live or die, as the event might chance to fall out, unpitied, uncared for, unsoothed.

"Yes, my dear grandchildren, such was the bitter lot of a daughter of wealth, power, and luxury,--one, who had never known want, sorrow, or toil, till the period of her bitter slavery. I passed through two dreadful nights; my lips were parched, each breath appeared to scorch me as I drew it in. I tried to pray, but the agony of thirst I suffered choked my utterance. I endeavoured to raise my thoughts to my Saviour, and for a few moments felt cheered by the prospect that He 'had opened the kingdom of Heaven to all true believers.' My fast-increasing pains confused these consoling reflections. I saw streams of water I could not reach, and juicy grapes whose clusters vanished before they reached my lips. I saw--and this was no illusion,--the mountain vultures descend from the lofty crags, and wheel nearer and nearer to me, without the power to scare them away. I already felt their wings fan my cheek, when an angel, as I thought, came and drove them away, nor performed for me this good office alone, for she held a cup of milk to my parched lips, and bade me drink, and live."

"An angel, dear grandmamma!" cried Adeline and Adolphe at once, in a tone of wonder, their tearful eyes expanding with amazement and awe. "God sent his angel, and delivered you, as He has delivered some of His saints[2] in their extremity."

|

The reader must here remember, that the speakers were Roman Catholics, who believe in the continuance of miracles in their church. |

"The Lord did not work, my children, a visible miracle to preserve me, but He wrought a change in the heart of Fatmè, by means of the still small voice of conscience, whose whispers would not let her sleep. Indeed, my dear children," continued the venerable lady, "the impulse to do good and to resist evil, is as much the work of the Holy Spirit in the human mind, and as wonderfully tends to bless and deliver us, as those stupendous miracles that brought water from the stony rock for the gasping Israelite multitude, or swept a path for them through the trackless deep. Pious people call these unexpected deliverances, that, in the course of every person's life, sometimes occur, providences. The thoughtless, and ungrateful, and impious, call them lucky chances.

"By the providence of a merciful God, Fatmè could not sleep that night, and her thoughts, during her vigils, reverted to me. She wondered if I yet lived; and, without feeling, then, any pity, felt an ardent curiosity to know the fact, and stole out to the place where I lay gasping for breath and tormented with agonizing pain. While she looked upon me, she was cut to the heart, for God inclined her to show me pity. She ran and milked one of the goats into a calabash, and held it to my lips. I received it as, what it was, a gift from Heaven, but my wandering and confused ideas led me to imagine that my preserver was an inhabitant of the skies. It seems she stayed with me all that night, bathing my face and hands with water, nor ceased her humane cares till the dawning of the day. These particulars I learned from her own lips afterwards, for it was some time before I recognized my benefactress in my foe, the hitherto haughty cruel daughter of the sheik.

"Her feelings during my helpless weakness resembled these with which a mother regards her sick child. She continually stole to me, to bring me grapes, or dates, or limes, and the first glimpse I had of returning consciousness, revealed the features of Fatmè in those of my supposed guardian angel.

"The interest this young female now took in my fate, occasioned an alteration in the conduct of her parents; they now sent for me home, but I entreated to remain where I was, as the open air was far more agreeable to me than the close atmosphere of their crowded dwelling.

"While yet an invalid, with the shadow of death hovering about me, and suffering under the deep nervous depression that generally attends a long-protracted recovery, my thoughts frequently reverted to my lost mother, to my native Christian country, and to the fixed eternal state, into which I appeared, even then, entering. I had fully completed my fourteenth year, and had lost for ever the thoughtlessness and gaiety of childhood.

"Necessity had done the work of time: I was prematurely wise, because prematurely experienced. I carefully recalled to mind the religious instructions I had received from my dear mother and the ministers of religion, and how I pined for good books and godly Christian company. The first I found in that best, holiest book, which, though injudiciously restricted, in general, by the canons of our church, was life and health, and joy to me. In creeping, rather than walking from my sheltering tree, I stumbled in the high grass, over something which proved to be a book; on opening its damp, half obliterated pages, I found it to be an old copy of the Geneva Bible. In an extasy of joy, I pressed it to my bosom. It bore a French name and ancient date on the title page. Probably, it had been the property of some slave, condemned to perish here, and had comprised his hope in life and death; his only treasure, as well as his only earthly possession. I began to read, to mark, to learn, to pray with great fervency. The day-spring from on high visited me.

"No longer disquieted about my present situation, I began to wish to be with God, from real love to Him rather than, as hitherto, to escape the troubles of this life. Separated from my dear relatives, from my faithful servants, I could yet pray for them. And oh, my children, what a blessed privilege is that of prayer, 'that brings Heaven down to us, and raises us to Heaven.' The time of my convalescence, was, perhaps, the really happiest time of my life, because at no other period did I feel or enjoy such close communion with God in prayer.

"After my recovery, I grew considerably taller; all the blackness I had acquired in the sun, wore off; my hair, once more, fell on my face and shoulders, in profuse ringlets of nature's curling; and Aladin, that self-willed, obstinate youth, began to talk of asking me for a wife, of his father. The sheik was undecided whether to sell me to some rich man, to wait for my friends' seeking me out and ransoming me, or to give me to his heir, now marriageable.

"In the mean while, having received no answer to my second letter, I dispatched my third, still hoping to prove a happier fortune than to be the wife of a future sheik.

"My master, though still undecided how to dispose of me to the best advantage, determined to make me keep the personal advantages I unfortunately possessed. He made me wear a black horse-hair veil, with only a single aperture, large enough to admit one of my eyes, whenever I went abroad, and would suffer me to perform no outdoor work. Milking the goats, amusing the children, and nursing a lovely female infant Gulbeyaz had just brought him, was all the employment now expected from me. My dress consisted of blue cotton trowsers; a caftan, or robe; and vest of the same stuff; a turban, or more properly speaking, a high Syrian cap, with a muslin veil wound round it, exactly resembling those curious head-dresses worn in Europe from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, and which you know are still retained in Normandy by the peasantry, and are called cauchoise,--red leather slippers, without any stockings, completed my attire.

"The children grew fond of me, and shared with me, unasked, their bread and milk; even the dogs became tame and familiar. Fatmè was my faithful friend, Gulbeyaz mingled some kindness with her severe manners, the slaves were respectful, and Aladin more determined to make me his wife than ever.

"More than a twelvemonth had elapsed since my captivity: my condition was certainly much ameliorated. I began to speak the Moorish language fluently, and, but for my daily studies in the scriptures, should probably soon have lost my mother tongue.

"The great influence I had acquired over the mind of Fatmè, and the affection of her brothers and sisters, led me to try whether I could not render them more humane and gentle in their manners. My remonstrances, when they used harsh words or blows to the slaves, or fought with other children of their own age, began to take effect; and as they became kinder to those about them, they were less troublesome to their own parents. Even Gulbeyaz acknowledged that they improved under my care. I began to teach Fatmè my own language. It is true, I had but one book, but that was the best, and, perhaps, even the easiest from which I could teach her. The parables, which I translated to her and the children, delighted them as stories, and I tried to make them comprehend the moral they inculcated. The customs of these wild tribes made these beautiful lessons appear easier to their comprehension than even to Europeans of the same tender age, because more in keeping with their usual habits. It is said that the more we prize religion ourselves, the greater will be our desire of promulgating its blessings to others.

"The sincere Christian is always a philanthropist, and the same love that brought Jesus Christ from heaven, still actuates His humblest follower to diffuse the knowledge of the Gospel to whoever will give it a hearing. This spirit of Christian benevolence made the apostles travel into distant countries, made them face a thousand perils, to give light to those that sat in darkness and the shadow of death, and, finally, attest the truth of their doctrine with their blood. I could not see Fatmè daily invoke the false prophet, without feeling my young heart stirred within me. I spoke, and my servile condition, although it could not quench my zeal, moderated and kept it in the due bounds of prudence. The Lord inclined Fatmè to listen, and even in this desert wilderness I enjoyed the company of a Christian friend.

"I now began to think that it was the intention of Providence that I should remain in Africa; yet the prospect of being the wife of Aladin, was by no means a cheering one. His fierce bigotry turned away with scorn from the pure doctrines of the Holy Jesus; and had he known that Fatmè had imbibed them from me, he would have sacrificed us both upon the spot. I could entertain no hope of winning to my own faith a spouse of such a temper. As it was, his vehement love scarcely saved me from his furious zeal for the honour of Mahomet. I shall never forget how cruelly he grasped my arm, when he finally told me to name the Nazarine no more, leaving a black circle round my wrist, as a constant memorial for months of his prohibition.

"I told Fatmè of the circumstance, and entreated her to procure the writing materials of which her father had deprived me, that I might make a last attempt to gain my liberty. She wept at the idea of losing me, yet granted my request. I found, to my great mortification, that the ink was nearly dried up, and that the book from which I had hitherto obtained my paper, was entirely marred by mice. I tore a blank leaf from the Bible, and wrote, with difficulty, my last appeal to the French consul. The exhausted state of my writing materials gave me no hope of ever inditing another. I fastened it with one of my own long ringlets, and resolved to wait for a favourable answer. I neither doubted Monti's fidelity nor good-nature, yet he had hitherto been completely unsuccessful.

"While pondering over this matter, the renegade accosted me upon the very subject next my heart. I remembered that I had never made him or his colleague any promise, and now, resolving to ensure the safe deliverance of my epistle, I promised, in my father's name, freedom, and a handsome sum as their reward in case of my ransom. Monti's eyes brightened, and he took my letter, saying, with tears in his eyes, 'Ah, signora, it is not the hope of liberty alone that makes me desirous of serving you; it is because you have kept the Christian faith undefiled in the midst of persecution and contempt. Oh, that I had been thus constant, and then the sorrows of my eventful life would not be imbittered by remorse. Mine is a strange history. Listen to it with an indulgent ear, and pity while you condemn Marco Monti, the renegade.'

"I expressed a desire to know his story, and he related it to me, as near as I can recollect, in these words:

" 'Ten long years have elapsed in woful slavery in this heathen land, yet the recollection of my native Italy is as dear as ever to my heart. I think of my mother and brethren till a mist comes over my eyes, and my senses are bewildered and wandering. A thick cloud hangs over my soul; I try to pray, but then my outward apostacy seems to forbid me to address that awful Being whose creed I have renounced. They call me here 'Monti, the Renegade.' Alas! what an infamous designation for one whose brow was signed in baptism with the blessed symbol of redemption! It was not thus they named me in my own sunny clime.

" 'I frighten you, Signora; but mine is a dreadful story, and I want nerve to tell it out; yet I must make the effort, for the secret weighs upon my mind, like lead. I was born on the estate of Conte Bernardo Manfredonia, younger brother to the Duca of that noble house, and my eyes first opened on the blue waters of the Venetian gulf. My parents, though not affluent, were in good circumstances, for my father commanded a galley belonging to the Conte, and my mother was nurse to that nobleman's only son. I was some years older than my foster brother, who was a child of great beauty and still greater promise. Leoni Manfredonia was indeed a bold, frank, generous creature, the darling of his father's vassals, who delighted to witness his infant daring, and loved his sunny temper.

" 'The Conte himself was an austere man, much feared, but little beloved. His young son engrossed all his affection, he had neither friendship nor liking for any other living thing. On the death of the Duca, the guardianship of his nephew devolved upon him; and the weekly constitution, and, perhaps, feeble character of the little Duca, inspired him with hopes of succeeding to the territories and titles of Manfredonia. As it was, he ruled, or rather reigned, in the castle, in the name of the young Amadeo; and some thought that the boy would find it no easy matter to get his inheritance out of his uncle's hands.

" 'Nothing could be more unlike our master's son than the Duca, and yet the love Leoni Manfredonia bore him was strong as death; and as the Duca was regarded with coldness and aversion by his uncle, and treated with little respect by the very menials who ate his bread, his heart clave to his generous cousin. Leoni, indeed, was the column that sheltered and protected his feeble branches. I, who had the honour to serve my foster brother, can testify to the truth of his affection.

" 'The born vassals of the young Duca took no interest in their young lord. Leoni was their favourite, and many openly expressed their hopes that the handsome high-spirited son of Conte Bernardo Manfredonia might become their head. The object of these rash wishes was the only person who did not share the general feeling. It was sweet to him to extricate his cousin from those difficulties and dangers into which he had rashly plunged himself. There could be no rivalry between them, for timid as Amadeo was, he always followed the lead of our young hero. He had, among many other fears, a great dread of the water, and his very first attempt at swimming had liked to have proved fatal to him. It was his heir who resolutely supported his exhausted frame, and, at the risk of his own life, brought him safe to shore.

" 'This brave feat pleased his father little, but the sickly constitution of his nephew received so severe a shock, that his ambitious hopes were more confirmed after this accident than before. If his nephew became imbecile, he could put him aside, and assume at once the title. I do not believe, at that time, that he had any intention of shedding his blood. The long indisposition of Amadeo left him lame and seemingly childish, for his age, and he spoke rarely, even to his cousin, before witnesses. Now, whether during his sickness some words had escaped from his attendants to arouse his suspicions, or that he had an instinctive fear of his uncle, I cannot say, but a trifling circumstance unveiled the ill-will the Conte bore to his innocent nephew.

" 'The boys occupied the same chamber, and as nothing is kept secret in the palazzi of the great, their discourse, on the eve of a great masquerade to be given by the Conte, was overheard by my mother, who you remember, Signora, was nurse to Leoni.

" 'What character do you mean to take?' asked the Duca.

" 'I have not made up my mind; I want to surprise everybody.'

" 'Suppose you play the Duca Manfredonia to-morrow night.'

" 'That would just do,--I shall then advance with a majestic air towards the company, and bid them welcome to my castle of Manfredonia.'

" 'You would like, then, to be Duca, always?'

" 'No, only for one night. Well, it is settled then, that you are to be Leoni; and I, Amadeo.'

" 'You forgot that I am lame.'

" 'We will both limp,--both wear the same kind of dress and mask; and as we are the same height, the trick will pass off well. There will be two Ducas, and nobody will guess which is the right one.'

" 'Now, though this was said by Leoni Manfredonia in the innocence of his heart, his cousin suddenly became silent, and, after a long pause, said--

" 'There can be only one Duca of Manfredonia at a time. I wish you were that one, only then you must be a poor lame feeble boy that nobody loves or cares for.'

" 'Do I not love and care for thee, Carissimo?'

" 'Your father does not--he wishes me dead, I know; but you, Leoni are kind, and once saved my life.'

" 'I won't play the Duca, then. What ails thee, my Amadeo? thou art full of gloomy fancies. It was you who first proposed the character, and I thought you were in earnest, Duca.'

" 'And so I am, Leoni. We will play the Duca together, but I hope your father will not be angry.'

" 'Angry with me? oh, no, that would be strange. He loves me as his life; he never brought me home a step-mother.'

" 'We are both motherless; but you are happier than I am, for I remember mine and all her love.'

" 'My nurse has been a mother to me, I have known no other; and Lorenzo and Marco are like brothers to me; but thou art none,--thou art more my friend; and am I not mother and father and all and every thing to thee, Manfredonia?'

" 'Yes, yes, Leoni.'

" 'The Duca's voice faltered, and my mother heard him sob and weep. She related this discourse at home, and much we praised our noble foster brother. It was quite evident to us all that the young Duca feared his uncle. His stupidity was feigned to blind his guardian's eyes.

" 'The day of the masquerade was a proud one to Count Bernardo Manfredonia, who welcomed his guests with as much ceremony as if the castle were his own, and its lawful master indeed sleeping with his fathers.

" 'As my mother waited on the company, and Lorenzo and I wore the Conte's liveries, we had the sight for nothing, and a brave one it was. It was as good as a buffo to see the bearing of Leoni Manfredonia as he advanced to receive the visitors, in his assumed character. The Conte's brow darkened, but only for a moment. The boy spoke in his own clear joyous voice, and the stern father knew its tones, and gazed on him till his eyes filled with tears of tenderness and pride, and no wonder, for Leoni behaved like a young prince; and when he did unmask, and was recognized by many of the company, there arose a general murmur of regret that he was not the person whose honours he had assumed. As if ashamed of receiving these flattering compliments, the youth suddenly withdrew himself from that gay scene, nor would he re-enter the saloon till accompanied by the Duca, whom he led forward and presented by name to the most distinguished guests. Amadeo was timid and retiring by nature, and he did not shine by his cousin's side, nor did Leoni appear less amiable when stripped of his imaginary title. Some, doubtless, accused him of sinister motives, and fancied this trick was a contrivance between him and his father.

" 'Nothing, indeed, could have injured his cousin's interests more than the part he had played; yet it was done in singleness of heart, with no other view than amusement. The Conte was delighted, and vowed, in his own mind, to make his son heir of the titles and territories of Manfredonia, by fraud or force, without delay.

" 'He spoke of his nephew with pity, lamenting his deficiency of understanding in pathetic terms; and so well was he seconded by some of his great connections at court, that several eminent persons came to Manfredonia, to examine into the reputed lunacy of its young lord. As the object of their visit was kept secret from the menials, I should never have guessed it, if my foster-brother had not disclosed it to me, himself.

" 'He had been hunting, some leagues off, with his father, and returned fatigued and evidently out of spirits. Trouble was written on his open brow, in lines too legible to be concealed. I hastened to meet him, but he took no notice of me. I had never seen him so disturbed before. After some minutes passed in respectful silence, I ventured to remind him that his usual hour for dressing had already passed. He started, and motioned me to follow him to his apartment.

" 'Marco Monti, I think, nay, I am certain that I can trust you,' said he, as he threw himself into a seat. I assured him of my fidelity. 'I place, this day, the honour of the house of Manfredonia in your keeping; but we have been nurtured at the same breast--I feel that you will not betray me.' There was a pause,--the noble young heart shrank from disclosing to a menial a parent's meditated crime. He at length, said, but with effort,--'Marco, my father means to defraud my cousin of his dukedom. These expected guests are sent expressly from the Neapolitan court, to ascertain if Amadeo be indeed as he has been reported by his uncle; and he,--yes, my father, wishes me to become a party in this iniquitous design.'

" 'I looked at my young lord, but he had covered his face with his hands, I saw his father's conduct had cut him to the heart.

" 'Marco, among these prejudiced judges, is the cardinal Ossuna, a good man, who will not sanction an oppressive measure against an orphan. I fear my cousin's timidity may give some countenance to the charge preferred against him. I would warn him, but how can I tell him that my father is about to rob him of his heritage? Spare my shame, Monti, and make this black design known to him, without delay.' I promised, and was about to obey him, when he motioned me to stay, and drawing a paper from his bosom, said, 'My faithful Marco, it is my father's intention that I pronounce a Latin oration, to welcome his eminence, the Cardinal, to Manfredonia. Now, I mean to falter in the very commencement of this task. My cousin must prompt me; in fact, I will manage so that he goes through the whole speech; and, if he seconds my plan, his dukedom is secured to him for life.'

" 'I expressed some doubts lest the young Duca's memory and voice should fail him in this arduous trial.

" 'They must not, Monti.--Here is the oration; tell him to get it by heart, and trust in God to bring him through this peril. Marco, bid him remember that He is good, though men are very wicked. Assure him of my love, and tell him that I am too closely watched to talk with him in person. Ah! Marco, my heart foreboded ill when we were no longer suffered to occupy the same apartment. Yet, surely, my father will not touch my cousin's life: I know not why, dear Marco, but I fear.'

" 'There was, indeed, cause enough for Leoni's apprehensions. Conte Bernardo Manfredonia had never been known to change his purpose. His revenge, though slow, was sure. If foiled in his present design, I knew he would not hesitate to take off the innocent object of his hate. I did not express my thoughts to my dear young lord, for his mind was already overburdened. I departed to execute my delicate commission.

" 'To my great surprise, I found the Duca quite aware of his situation, and prepared to meet it. That fatal masquerade had more than confirmed his suspicions, he had heard that which was never meant to meet the ear of the nominal lord of the castle.

" 'I have but three friends in this hard world,' said he,--'God, my noble cousin, and yourself. The first is sufficient to destroy the wicked machinations of my uncle. Tell my dear Leoni, that I will follow his wise counsel. I am timid, but One is with me, whose strength can support my weakness. He has appointed me to this trial, and He will enable me to meet it. Bid Leoni pray for me.'

" 'I perceived by this discourse that the young Duca had shaken off, for ever, childish things. I remembered that the good Padre Stephano had often told us, That adversity was man's best teacher. I now felt little fear for the success of my lord's plan. Methought the priest himself could not have spoken better.

" 'On the morrow, the Conte, the young Duca, and my dear master, met his eminence the Cardinal, and his company, at the foot of the grand staircase. Leoni Manfredonia then put himself into a graceful attitude, and commenced the Latin oration, wherewith he was to welcome his illustrious guest to the castle. After he had pronounced a few sentences, he suddenly faltered, and turned a look of entreaty upon the Duca, who supplied him with the needful word. Leoni again resumed his task, and again stopped short. His eminence, and his illustrious company, were in pain for him; his excellency the Conte was incensed at his tutor, yet felt like a father for the mortification of his son. He prompted him, but Leoni would not understand the hint. He suddenly turned to the guests, saying, with a smile 'Most illustrious signors, I am, as you perceive, slow of study, this morning, but the Duca Manfredonia is able to repeat the whole oration, and, will doubtless, be proud to bid you welcome to his castle.' Then gayly putting his cousin forward, he retreated a few steps, and assumed an air of deep and earnest attention.

" 'The Duca raised his eyes to the Cardinal's face, and the benign expression of that holy man's features assured him he had found a friend. He pronounced the oration in a low sweet voice. Nor did he once falter, from beginning to end.

" 'He was long, and loudly applauded, and when his eminence paid him a handsome compliment in the same language, the triumph of the virtuous young kinsmen was complete. A single lowering look expressed the rage and bitter disappointment of the crafty Conte. No one perceived it but myself, but it told me that his innocent nephew was doomed to be his victim.

" 'It was a proud day for Leoni Manfredonia; his generous spirit rejoiced in the success of his stratagem. His integrity was secure, the young Duca safe, and his father saved from the commission of a deadly crime. He did not fear his anger, he knew that every feeling of that stern heart was centred in him. And well, indeed, would it have been for him, if the Conte had loved his son less, and honour more.