* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Struggle for Imperial Unity

Date of first publication: 1909

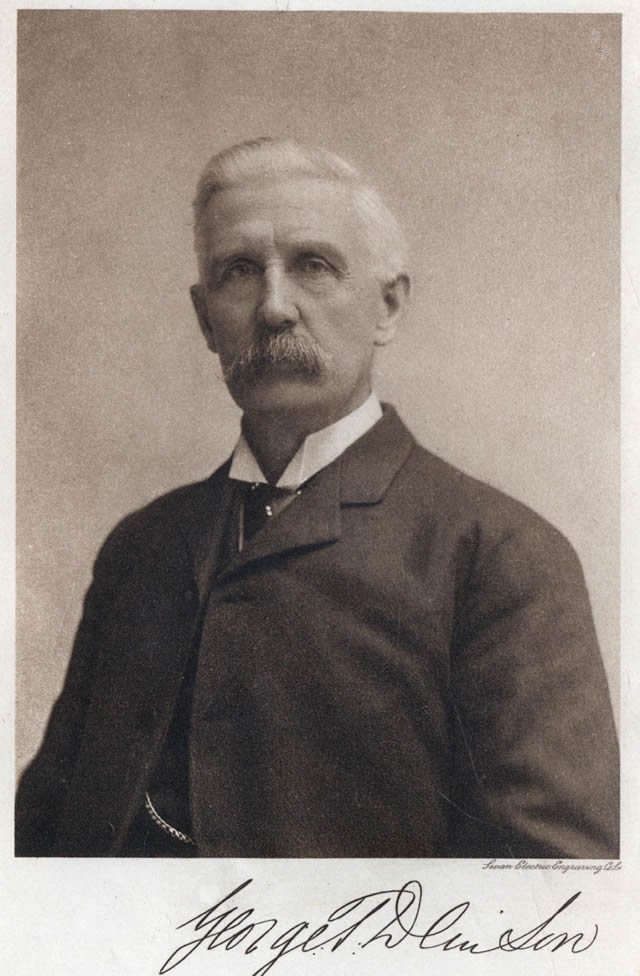

Author: Colonel George T. Denison (1839-1925)

Date first posted: Aug. 26, 2014

Date last updated: Aug. 26, 2014

Faded Page eBook #20140893

This eBook was produced by: David T. Jones, Al Haines, Ron Tolkien & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Some fifteen years ago the late Dr. James Bain, Librarian of the Toronto Public Library, urged me to write my reminiscences. He knew that, as one of the founders of the Canada First party, as Chairman of the Organising Committee of the Imperial Federation League in Canada, then President of it, and after its reorganisation, under the name of the British Empire League in Canada, still President, I had much private information, in connection with the struggle for Imperial Unity, that would be of interest to the public. He was therefore continually urging me to put down my recollections in order that they should be preserved.

I put the matter off until the year 1899, when I was retired from the command of my regiment on reaching the age limit. I then wrote my military recollections under the title Soldiering in Canada. This was so well received by the Press and by the public that, being still urged to prepare my political reminiscences, I began some years ago to write them, [vi]and soon had them finished. In the early part of 1908 Dr. Bain read the manuscript, and then asked me not to delay, as I had intended, but to publish at once. Shortly before his death last spring, he again expressed this wish. I have consulted several of my friends, and in view of their advice now publish this book.

I have not attempted to write a history of the Imperial Unity movement, but only my personal recollections of the work which I have been doing in connection with it for so many years. I still feel, as I did when I was writing my military recollections, that I should follow the view laid down by the critic who said that reminiscences should be written just in the style in which a man would relate them to an old friend while smoking a pipe in front of a fire. I have tried to write the following pages in that spirit, and if the personal pronoun appears too often, it will be because, being recollections of work done, it can hardly be avoided.

GEORGE T. DENISON.

Heydon Villa, Toronto,

January, 1909.

The idea of a great United British Empire seems to have originated on the North American Continent. When Canada was conquered and the power of France disappeared from North America, Great Britain then possessed the thirteen States or Colonies, as well as the Provinces of Quebec and Nova Scotia.

The thirteen colonies had increased in population and wealth, and the British statesmen burdened with the heavy expenses of the French wars, which had been waged mainly for the protection of the American States, felt it only just that these Colonies should contribute something towards defraying the cost incurred in defending them. This raised the whole question of taxation without representation, and for ten years the discussion was waged vigorously between the Mother Country and the Colonists.

A large number of the Colonists felt the justice of the claim of the Mother Country for some assistance, but foresaw the danger of violent and arbitrary action [2]in enforcing taxation without the taxed having any voice in the matter. These men, the Loyalists, were afterwards known by the name United Empire Loyalists, because they advocated and struggled for the organisation of a consolidated Empire banded together for the common interest. Thomas Hutchinson, the last loyalist Governor of Massachusetts, and one of the ablest of the loyalist leaders, believed in the magnificent dream of a great Empire, to be realised by the process of natural and legal development, in full peace and amity with the Motherland, in short, by evolution.

Joseph Galloway, who shared with Thomas Hutchinson the supreme place among the American statesmen opposed to the Revolution, worked incessantly in the cause of a United Empire, and has been characterised as “The giant corypheus of the pamphleteers.” He was a member of the first continental Congress and introduced into that body, on the 28th September, 1774, his famous “Plan of a proposed union between Great Britain and the Colonies.”

In introducing this plan Galloway made some most interesting remarks, which bear their lesson through all the years to the present day. He said:

I am as much a friend of liberty as exists. We want the aid and assistance and protection of the arm of our Mother Country. Protection and allegiance are reciprocal duties. Can we lay claim to the money and protection of Great Britain upon any principles of honour and conscience? Can we wish to become aliens to the Mother State? We must come upon terms with Great Britain. Is it not necessary that the trade of the Empire should be regulated by some power or other? Can the Empire hold together without it? No. Who shall regulate it?

Galloway’s scheme was very nearly adopted. In the final trial it was lost by a vote of only six colonies to five. This rejection led Galloway to decline an election to the second Congress, and to appeal to the higher tribunal of public opinion. The Loyalists followed this lead, and the struggle went on for seven years, between those who fought for separation and independence and those who fought for the unity of the Empire.

The Revolution succeeded through the mismanagement of the British forces by the general in command, followed by the intervention of three great European nations, who were able to secure temporary command of the sea.

The United Empire Loyalists were driven out of the old colonies, and many found new homes in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada; some also went to England and the West Indies, carrying with them the cherished ideas of maintaining their allegiance to their Sovereign, of preserving their heritage as British subjects, and still endeavouring to realise the dream of a United British Empire.

For this cause they had made great sacrifices, and, despoiled of all their possessions, had been driven into exile, in what was then a wilderness. Men do not make such extraordinary sacrifices except under the influence of some overpowering sentiment, and in their case the moving sentiment was the Unity of the Empire. The greater the hardships they encountered, the greater the privations and sufferings they endured for the cause, the dearer it grew to their hearts, for men value those things most that have been obtained at the highest cost.

In the war of 1812-’14 the intense spirit of loyalty in the old exiles and their sons caused the Canadian [4]Provinces to be retained under the British flag, and when afterwards, in 1837, rebellion broke out, fomented by strangers and new settlers, the United Empire Loyalist element put it down with a promptitude and vigour that forms one of the brightest pages in our history. In Nova Scotia the agitation for responsible government was headed by Joseph Howe, a son of one of the exiled Loyalists. Suggestions of rebellion to him were impossible of consideration, and he held his province true to the Empire, and succeeded by peaceful and loyal measures in securing all he wanted.

Then Great Britain repealed her corn laws instead of amending them, and introduced free trade instead of rearranging and reducing her tariff. She deprived Canada of a small advantage which her products up to that time enjoyed in the British markets, and which was rapidly assisting in the development of what was then a poor and weak colony. This act was a severe blow to Canada, because it meant that Great Britain had embarked on the unwise and dangerous policy of treating foreign and even hostile countries as favourably as her own peoples and her own possessions.

This caused a great deal of dissatisfaction in some quarters, and in the year 1849 some hundreds of the leading business men in Montreal signed a manifesto advocating annexation to the United States. This aroused strong opposition among the United Empire Loyalist element in Upper Canada; the feeling soon manifested itself in a way which proved that no pecuniary losses could shake the deep-seated loyalty of the Canadian people. The annexation movement withered at once.

Seeing how severely the action of the Mother Country had borne upon Canada, Lord Elgin, then [5]Governor-General of Canada, was instructed to endeavour to arrange for a reciprocity treaty with the United States, or in other words to ask a foreign country to give Canada trade advantages which would recompense her for what Great Britain had taken away from her. The United States Government, either influenced by the blandishments of Lord Elgin, or by a politic desire of turning Canada’s trade in their own direction, and making her dependent for her business and the prosperity of her people upon a treaty which the United States would have the power of terminating in twelve years, consented to make the treaty.

It was concluded in 1854, and for twelve years during a most critical period, when railways and railway systems were beginning to be established, the great bulk of the trade of Canada was diverted to the United States, the lines of transportation naturally developed mainly from north to south, and the foreign handling of our products was left very much to the United States. The Crimean war broke out in 1854 and lasted till 1856, raising the price of farm produce two-fold, and adding largely to the prosperity of the Canadian people. The large railway expenditure during the same period also aided to produce an era of inflation, while during the last five years of the existence of the treaty the Civil War in the United States created an extraordinary demand, at war prices, for almost everything the Canadian people had to sell. The result was that, from reasons quite disconnected from the reciprocity treaty, during a great part of its existence the Canadian people enjoyed a most remarkable development and prosperity.

The United States Government, although the treaty is said to have been of more real value to them than [6]to Canada, at the earliest possible moment gave the two years’ notice to abrogate it, and they did so evidently in the hope that the financial distress and loss that its discontinuance would bring upon the people of Canada would create at once a demand for annexation. In a sense they were right; talk in favour of annexation was soon heard from a few, but the old sentiment of loyalty to the Empire was too strong, and the people turned to the idea of the confederation of the Provinces and the opening up of trade with the West Indies and other countries. The Confederation of Canada was the result, and the Dominion was established on the 1st of July, 1867.

My object in writing the following pages is to describe more particularly from my own recollection, and my own knowledge of the facts, the movement in favour of the Unity of the Empire which has been going on during the last forty years.

The extraordinary change that has taken place in Canada, in every way, in the last fifty years cannot be appreciated except by those who are old enough to remember the condition of affairs about the middle of last century. The ideas, sentiments, aspirations, and hopes of the people have since then been revolutionised. At that time the North American Provinces were poor, sparsely settled, scattered communities, with no large towns, no wealthy classes, without a literature, with scarcely any manufactures, and with a population almost entirely composed of struggling farmers and the few traders depending upon them. The population was less than 3,500,000. The total exports and imports in 1868 were $131,027,532. The small Provincial Governments found their duties confined to narrow local limits. All the important questions were entirely in the hands of the Home Government. The defence was paid for by them. British troops occupied all the important points, and foreign affairs were left without question entirely in the hands of the British statesmen. The Provinces had no power whatever in diplomacy, and were interested only in a few disputes with the United States in reference to boundary difficulties, which were [8]generally settled without consultation with the Colonial Governments, and with very little thought for the interests or the future needs of the little British communities scattered about in North America.

The settlements were comparatively so recent that men called themselves either English, Irish, or Scotch, according to the nationality of their parents or grandparents. The national societies, St. George’s, St. Andrew’s and St. Patrick’s, may have helped to continue this feeling, so that in reference to the various Provinces there was not, and could not be, any national spirit. Another cause that led to the absence of national spirit or self-confidence was that Great Britain not only held the power of peace and war in her own hands, but, as a consequence, took upon herself the responsibility for the defence of the Provinces. British troops, as has been said, garrisoned all the important points, and all the expenses were borne by the Imperial Government. Canada had no militia except upon paper, no arms, no uniforms, no military stores or equipment of any kind. She depended solely upon the Mother Country; even the Post Office System was a branch of the English Post Office Service. One can readily imagine the lack of local national spirit. Of course the loyalty to the Mother Country and the Sovereign and the Empire was always strong, but it was not closely allied to the spirit of nationality as attached to the soil.

When the Crimean war broke out, the British troops were required for it, and Canada was called upon to raise a militia force for her own needs. This she did. Ten thousand men were organised, armed, uniformed, and equipped at her expense. They were called the Active Militia, and were drilled ten days in each year. [9]The assumption of responsibility had an effect upon the country, and when the Trent difficulty arose the force was increased by the spontaneous action of the people to about thirty-eight thousand men. Four years later the Fenian raids took place upon our frontier, and were repulsed, largely by the efforts of the Canadian Militia. All this appealed to the imagination of our youth, and as confederation was proclaimed the following year the ground was fallow for sowing seeds of a national spirit.

The effect of confederation on the Canadians was very remarkable. The small Provinces were all merged into a great Dominion. The Provincial idea was gone. Canada was now a country with immense resources and great possibilities. The idea of expansion had seized upon the people, and at once steps were taken looking to the absorption of the Hudson’s Bay Territory and union with British Columbia.

With this came visions of a great and powerful country stretching from ocean to ocean, and destined to be one of the dominant powers of the world.

It was at the period when these conditions existed that business took me to Ottawa from the 15th April until the 20th May, 1868. Wm. A. Foster of Toronto, a barrister, afterwards a leading Queen’s Counsel, was there at the same time, and through our friend, Henry J. Morgan, we were introduced to Charles Mair, of Lanark, Ontario, and Robert J. Haliburton, of Halifax, eldest son of the celebrated author of “Sam Slick.” We were five young men of about twenty-eight years of age, except Haliburton, who was four or five years older. We very soon became warm friends, and spent most of our evenings together in Morgan’s quarters. We must have been congenial spirits, for our friendship has been close and firm all our lives. Foster and Haliburton have passed away, but their work lives.

| The seed they sowed has sprung at last, And grows and blossoms through the land.[1] |

Those meetings were the origin of the “Canada First” party. Nothing could show more clearly the hold that confederation had taken of the imagination of young Canadians than the fact that, night after [11]night, five young men should give up their time and their thoughts to discussing the higher interests of their country, and it ended in our making a solemn pledge to each other that we would do all we could to advance the interests of our native land; that we would put our country first, before all personal, or political, or party considerations; that we would change our party affiliations as often as the true interests of Canada required it. Some years afterwards we adopted, as I will explain, the name “Canada First,” meaning that the true interest of Canada was to be first in our minds on every occasion. Forty years have elapsed and I feel that every one of the five held true to the promise we then made to each other.

One point that we discussed constantly was the necessity, now that we had a great country, of encouraging in every possible way the growth of a strong national spirit. Ontario knew little of Nova Scotia or New Brunswick and they knew little of us. The name Canadian was at first bitterly objected to by the Nova Scotians, while the New Brunswickers were indifferent. This was natural, for old Canada had been an almost unknown Province to the men who lived by the sea, and whose trade relations had been mainly with the United States, the West Indies, and foreign countries.

It was apparent that until there should grow, not only a feeling of unity, but also a national pride and devotion to Canada as a Dominion, no real progress could be made towards building up a strong and powerful community. We therefore considered it to be our first duty to work in that direction and do everything possible to encourage national sentiment. History had taught us that every nation that had [12]become great, and had exercised an important influence upon the world, had invariably been noted for a strong patriotic spirit, and we believed in the sentiment of putting the country above all other considerations—the same feeling that existed in Rome

| When none was for a party When all were for the State. |

This idea we were to preach in season and out of season whenever opportunity offered. The next point that attracted our attention was the necessity of securing for the new Dominion the Hudson’s Bay Territory and the adhesion of British Columbia. At this time the Maritime Provinces were not keenly interested in either of these projects, while the province of Quebec was secretly opposed to the acquisition of the Territory, fearing that it would cost money to acquire and govern it, but principally because many of the French Canadians dreaded the growing strength in the Dominion of English speaking people, and the consequent relative diminution of their proportionate influence on the administration of affairs. The Hudson’s Bay Company were also dissatisfied at the prospect of the loss of the great monopoly they had enjoyed for nearly two hundred years. They continued the policy they had early adopted, of doing all possible to create the belief that the territory was a barren, inhospitable, frozen region, unfit for habitation, and only suitable to form a great preserve for fur-bearing animals. This general belief as to the uselessness of the country, and its remoteness and inaccessibility, which prevented any full information being gained as to its real capabilities, also had the effect of making many people doubtful as to its value and careless as to its acquisition. As [13]an illustration of the ignorance and false impressions of the value of the country, it is interesting to recall that when, in 1857, an agitation was set on foot looking to the absorption of the North-West Territories, very strong opposition came from a large portion of the Canadian Press. Some wrote simply in the interests of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Some wrote what they really believed to be true. Now that Manitoba No. 1 hard wheat has a fame all over the world, as the best and most valuable wheat that is grown, it is interesting to read the opinion of the Montreal Transcript in 1857 that the climate of the North-West “is altogether unfavourable to the growth of grain” and that the summer is so short as to make it difficult to “mature even a small potato or a cabbage.”

The Government, under the far-seeing leadership of Sir John Macdonald, were negotiating in 1868 for the purchase of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s rights, and they sent Sir George Cartier and the Hon. Wm. Macdougall to England to carry on the negotiations. Mr. Macdougall was a man of great force of character, an able debater and a keen Canadian. We knew he would do all that man could do to secure the territory for Canada, and as far as the arrangements in the old country were concerned he was successful.

In anticipation of the incorporation of the territory in the Dominion, and partly to assist the Red River Settlement by giving employment to the people, the Canadian Government sent up some officials and began building a road from Fort Garry, now Winnipeg, to the north-west angle of the Lake of the Woods. This was in the autumn of 1868. Mr. Macdougall appointed Charles Mair to the position of paymaster of this party, and at once we saw the opportunity of doing some [14]good work towards helping on the acquisition of the territory. We felt that the country was misunderstood, and it was arranged, through the Hon. George Brown, the proprietor and editor of the Toronto Globe, who had for many years been strongly in favour of securing the North-West, that Mair was to write letters to the Globe on every available opportunity, giving a true account of the capabilities of the territory as to the soil, products, climate, and suitability for settlement.

Mair soon formed a most favourable opinion, and became convinced that a populous agricultural community could be maintained, and that in time to come a large and productive addition would be made to the farming resources of Canada. He pictured the country in glowing terms, and practically preached that a crusade of Ontario men should move out and open up and cultivate its magnificent prairies. His letters attracted a great deal of attention, and were copied very extensively in the Press of Upper Canada and the Maritime Provinces. They were filled with the Canadian national spirit, and had a great effect in awakening the minds of the people to the importance of the acquisition of the country. Reports of his letters got back to Fort Garry, and caused much hostile feeling in the minds of the Hudson’s Bay officials, and the French half-breeds and their clergy. The feeling on one occasion almost led to actual violence.

Six years before this, in 1862, John C. Schultz (afterwards Sir John Schultz, K.C.M.G., Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba) had arrived in Fort Garry. He was then a young doctor only twenty-two years of age. He at once engaged in the practice of his profession, as well as in the business of buying and selling furs, and trading with the Indians and inhabitants. He was [15]born at Amherstburg, and had grown up and been educated in the country where Brock and Tecumseh had performed their greatest exploit in defence of Canada. He was a loyal and patriotic Canadian. He had been persecuted by Hudson’s Bay officials. Once he was put in prison by them, but was soon taken out by a mob of the inhabitants. Mair soon became attached to Schultz. They were about the same age, and possessed in common a keen love for the land of their birth. Mair told him of the work of our little party, and he expressed his sympathy and desire to assist. In March, 1869, Schultz came down to Montreal on business, and when passing through Toronto brought me a letter of introduction from Mair, who had written to me once or twice before, speaking in the highest terms of Schultz, and predicting (truthfully) that in the future he would be the leading man in the North-West, and he advised that he should be enrolled in our little organisation. Haliburton happened to be in Toronto at the time and I introduced Schultz to him and to W. A. Foster, and we warmly welcomed him into our ranks. He was the sixth member. Soon afterwards we began quietly making recruits, considering very carefully each name as suggested.

Schultz went back to Fort Garry. The negotiations for the acquisition of the Hudson’s Bay Territory were brought to a successful termination, and it was arranged that it should be taken over on the 1st December, 1869. Mr. Macdougall was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Territory, and with a small staff of officials he started for Fort Garry.

During this time Haliburton had been lecturing in Ontario and Quebec on the question of “interprovincial trade,” showing that it should be strongly [16]encouraged, and would be a most efficient means for creating a feeling of unity among the various provinces. He also delivered a very able lecture on “The Men of the North,” showing their power and influence on history, and pointing out that the Canadians would be the “Northmen of the New World,” and in this way he endeavoured to arouse the pride of Canadians in their country, and to create a feeling of confidence in its future. This was all in the line of our common desire to foster a national spirit, which formerly, in the Canadian sense, had not existed.

During this year, 1869, when the negotiations in England had been agreed upon, the Canadian Government had sent out a surveying expedition under Lieut.-Colonel Dennis. This officer had taken a prominent part in the affair of the Fenian Raid at Fort Erie three years before, with no advantage to the country and considerable discredit to himself. His party began surveying the land where a hardy population of half-breeds had their farms and homes, and where they had been settled for generations. Naturally great alarm and indignation were aroused. The road that was being built from Winnipeg to the Lake of the Woods also added considerably to their anxiety.

The Hudson’s Bay officials were mainly covertly hostile. The French priests also viewed an irruption of strangers with strong aversion, and everything tended to incite an uprising against the establishment of the new Government. When Lieut.-Governor Macdougall arrived at Pembina and crossed the boundary line, he was stopped by an armed force of French half breeds, and turned back out of the country. He waited till the 1st December, when his commission was to have come into force, and then appointed Lieut.-Colonel Dennis as Lieutenant and Conservator of [18]the Peace, and sent him to Fort Garry to endeavour to organise a sufficient force among the loyal population to put down the rebellion, and re-establish the Queen’s authority.

When Lieut.-Colonel Dennis reached Fort Garry, he went straight to Dr. Schultz’ house where Mair was staying at the time, and showed them his commission. Schultz, who was an able man of great courage and strength of character, as well as sound judgment, said at once that the commission was all that was wanted, and that he would organise a force of the surveyors, Canadian roadmen, etc., who were principally Ontario men, and that they could easily seize the Fort that night by surprise, as there were only a few of the insurgents in it, and those not anticipating the slightest difficulty. This was the wisest and best course, for had the Fort been seized, it would have dominated the settlement and established a rallying point for the loyal, who formed fifty per cent. of the population.

Colonel Dennis would not agree to this. On the contrary he advised Dr. Schultz to organise all the men he could at the Fort Garry Settlement, while he himself would go down to the Stone Fort, and raise the loyal Scotch half breeds of the lower Settlements. This decision at once shut off all possibility of success. Riel, the rebel leader, had ample opportunity not only to fill Fort Garry with French half breeds, but it enabled him to cut off and besiege Dr. Schultz and the Canadians who had gathered at his house for protection.

When matters had got to this point Colonel Dennis lost heart, abandoned his levies at the Stone Fort in the night, leaving an order for them to disperse and return to their homes. He escaped to the United [19]States by making a wide détour. Schultz and his party had to surrender and were put into prison. Mair, Dr. Lynch, and Thomas Scott were among these prisoners.

When the news of these doings came to Ontario there was a good deal of dissatisfaction, but the distance was so great, and the news so scanty, and so lacking in details, that the public generally were not at first much interested. The Canada First group were of course keenly aroused by the imprisonment and dangerous position of Mair and Schultz, and at that time matters looked very serious to those of us who were so keenly anxious for the acquisition of the Hudson’s Bay Territory. Lieut.-Governor Macdougall had been driven out, his deputy had disappeared after his futile and ill-managed attempt to put down the insurrection, Mair and Schultz and the loyal men were in prison, Riel had established his government firmly, and had a large armed force and the possession of the most important stronghold in the country. An unbroken wilderness of hundreds of miles separated the district from Canada, and made a military expedition a difficult and tedious operation. These difficulties, however, we knew were not the most dangerous. There were many influences working against the true interests of Canada, and it is hard for the present generation to appreciate the gravity of the situation.

In the first place the people of Ontario were indifferent, they did not at first seem to feel or understand the great importance of the question, and this indifference was the greatest source of anxiety to us in the councils of our party. By this time Foster and I had gained a number of recruits. Dr. Canniff, J. D. Edgar, Richard Grahame, Hugh Scott, Thomas [20]Walmsley, George Kingsmill, Joseph E. McDougall, and George M. Rae had all joined the executive committee, and we had a number of other adherents ready and willing to assist. Foster and I were constantly conferring and discussing the difficulties, and meetings of the committee were often called to decide upon the best action to adopt.

Governor Macdougall had returned humiliated and baffled, blaming the Hon. Joseph Howe for having fed the dissatisfaction at Fort Garry. This charge has not been supported by any evidence, and such evidence as there is conveys a very different impression.

Governor McTavish of the Hudson’s Bay Company was believed to be in collusion with Riel, and willing to thwart the aims of Canada. Mr. Macdougall states in his pamphlet of Letters to Joseph Howe, that in September 1868 every member of the Government, except Mr. Tilley and himself, was either indifferent or hostile to the acquisition of the Territories. He also charges the French Catholic priests as being very hostile to Canada, and says that from the moment he was met with armed resistance, until his return to Canada, the policy of the Government was consistent in one direction, namely, to abandon the country.

Dr. George Bryce in his Remarkable History of the Hudson’s Bay Company points out the serious condition of affairs at this time. The Company’s Governor, McTavish, was ill, the government by the Company moribund, and the action of the Canadian authorities in sending up an irritating expedition of surveyors and roadmakers was most impolitic. The influence of mercantile interests in St. Paul was also keenly against Canada, and a number of settlers from the United States helped to foment trouble and [21]encourage a change of allegiance. Dr. Bryce states that there was a large sum of money “available in St. Paul for the purpose of securing a hold by the Americans on the fertile plains of Rupert’s Land.” Dr. Bryce sums up the dangers as follows: “Can a more terrible combination be imagined than this? A decrepit Government with the executive officer sick; a rebellious and chronically dissatisfied Metis element; a government at Ottawa far removed by distance, committing with unvarying regularity blunder after blunder; a greedy and foreign cabal planning to seize the country; and a secret Jesuitical plot to keep the Governor from action and to incite the fiery Metis to revolt.”

The Canada First organisation was at this time a strictly secret one, its strength, its aims, even its existence being unknown outside of the ranks of the members. The committee were fully aware of all these difficulties, and felt that the people generally were not impressed with the importance of the issues and were ignorant of the facts. The idea had been quietly circulated through the Government organs that the troubles had been caused mainly through the indiscreet and aggressive spirit shown by the Canadians at Fort Garry, and much aggravated through the ill-advised and hasty conduct of Lieut.-Governor Macdougall.

The result was that there was little or no sympathy with any of those who had been cast into prison, except among the ranks of the little Canada First group, who understood the question better, and had been directly affected through the imprisonment of two of their leading members.

The news came down in the early spring of 1870 that Schultz and Mair had escaped, and soon afterwards [22]came the information that Thomas Scott, a loyal Ontario man, an Orangeman, had been cruelly put to death by the Rebel Government. Up to this time it had been found difficult to excite any interest in Ontario in the fact that a number of Canadians had been thrown into prison. Foster and I, who had been consulting almost daily, were much depressed at the apathy of the public, but when we heard that Schultz and Mair, as well as Dr. Lynch, were all on the way to Ontario, and that Scott had been murdered, it was seen at once that there was an opportunity, by giving a public reception to the loyal refugees, to draw attention to the matter, and by denouncing the murder of Scott, to arouse the indignation of the people, and foment a public opinion that would force the Government to send up an armed expedition to restore order.

George Kingsmill, the editor of the Toronto Daily Telegraph, at that time was one of our committee, and on Foster’s suggestion the paper was printed in mourning with “turned rules” as a mark of respect to the memory of the murdered Scott, and Foster, who had already contributed able articles to the Westminster Review in April and October 1865, began a series of articles which were published by Kingsmill as editorials, which at once attracted attention. It was like putting a match to tinder. Foster was accustomed to discuss these articles with me, and to read them to me in manuscript, and I was delighted with the vigour and intense national spirit which breathed in them all. He met the arguments of the official Press with vehement appeals to the patriotism of his fellow countrymen. The Government organs were endeavouring to quiet public opinion, and [23]suggestions were freely made that the loyal Canadians who had taken up arms on behalf of the Queen’s authority in obedience to Governor Macdougall’s proclamation had been indiscreet, and had brought upon themselves the imprisonment and hardships they had suffered.

Mair and Schultz had escaped from prison about the same time. Schultz went to the Lower Red River which was settled by loyal English-speaking half breeds, and Mair to Portage la Prairie, where there was also a loyal settlement. They each began to organise an armed force to attack Fort Garry and release their comrades, who were still in prison there. They made a junction at Headingly, and had scaling ladders and other preparations for attacking Fort Garry. Schultz brought up about six hundred men, and Mair with the Portage la Prairie contingent, under command of Major Charles Boulton, had about sixty men. Riel became alarmed, opened a parley with the loyalists, and agreed to deliver up the prisoners, and pledge himself to leave the loyalist settlements alone if he was not attacked. The prisoners were released and Mair went back to Portage la Prairie, and Schultz to the Selkirk settlement. Almost immediately Schultz left for Canada with Joseph Monkman, by way of Rainy River to Duluth, while Mair, accompanied by J. J. Setter, started on the long march on snow shoes with dog sleighs over four hundred miles of the then uninhabited waste of Minnesota to St. Paul. This was in the winter, and the journey in both cases was made on snow shoes and with dog sleighs. Mair arrived in St. Paul a few days before Schultz.

We heard of their arrival at St. Paul by telegraph, and our committee called a meeting to consider the [24]question of a reception to the refugees. This meeting was not called by advertisement, so much did we dread the indifference of the public and the danger of our efforts being a failure. It was decided that we should invite a number to come privately, being careful to choose only those whom we considered would be sympathetic. This private meeting took place on the 2nd April, 1870. I was delayed, and did not arrive at the meeting until two or three speeches had been made. The late John Macnab, the County Attorney, was speaking when I came in; to my astonishment he was averse to taking any action whatever until further information had been obtained. His argument was that very little information had been received from Fort Garry, and that it would be wiser to wait until the refugees had gone to Ottawa, and had laid their case before the Government, and the Government had expressed their views on the matter, that these men might have been indiscreet, &c. Not knowing that previous speakers had spoken on the same line I sat listening to this, getting more angry every minute. When he sat down I was thoroughly aroused. I knew such a policy as that meant handing over the loyal men to the mercies of a hostile element. I jumped up at once, and in vehement tones denounced the speaker. I said that these refugees had risked their lives in obedience to a proclamation in the Queen’s name, calling upon them to take up arms on her behalf; that there were only a few Ontario men, seventy in number, in that remote and inaccessible region, surrounded by half savages, besieged until supplies gave out. When abandoned by the officer who had appealed to them to take up arms, they were obliged to surrender, and suffered for long months in prison. I said these Cana[25]dians did this for Canada, and were we at home to be critical as to their method of proving their devotion to our country? I went on to say that they had escaped and were coming to their own province to tell of their wrongs, to ask assistance to relieve the intolerable condition of their comrades in the Red River Settlement, and I asked, Is there any Ontario man who will not hold out a hand of welcome to these men? Any man who hesitates is no true Canadian. I repudiate him as a countryman of mine. Are we to talk about indiscretion when men have risked their lives? We have too little of that indiscretion nowadays and should hail it with enthusiasm. I soon had the whole meeting with me.

When I sat down James D. Edgar, afterwards Sir J. D. Edgar, moved that we should ask the Mayor to call a public meeting. This was at once agreed to, and a requisition made out and signed, and the Mayor was waited upon, and asked to call a meeting for the 6th. This was agreed to, Mr. Macnab coming to me and saying I was right, and that he would do all he could to help, which he loyally did.

From the 2nd until the 6th we were busily engaged in asking our friends to attend the meeting. The Mayor and Corporation were requested to make the refugees the guests of the City during their stay in Toronto, and quarters were taken for them at the Queen’s Hotel. Foster’s articles in the Telegraph were beginning to have their influence, and when Schultz, Lynch, Monkman, and Dreever arrived at the station on the evening of the 6th April, a crowd of about one thousand people met them and escorted them to the Queen’s. The meeting was to be held in the St. Lawrence Hall that evening, but when we arrived there with the party, we found the hall crowded [26]and nearly ten thousand people outside. The meeting was therefore adjourned to the Market Square, and the speakers stood on the roof of the porch of the old City Hall.

The resolutions carried covered three points. Firstly, a welcome to the refugees, and an endorsation of their action in fearlessly, and at the sacrifice of their liberty and property, resisting the usurpation of power by the murderer Riel; secondly, advocating the adoption of decisive measures to suppress the revolt, and to afford speedy protection to the loyal subjects in the North-West, and thirdly, declaring that “It would be a gross injustice to the loyal inhabitants of Red River, humiliating to our national honour, and contrary to all British traditions for our Government to receive, negotiate, or treat with the emissaries of those who have robbed, imprisoned, and murdered loyal Canadians, whose only fault was zeal for British institutions, whose only crime was devotion to the old flag.” This last resolution, which was carried with great enthusiasm, was moved by Capt. James Bennett and seconded by myself.

Foster and I had long conferences with Schultz, Mair, and Lynch that evening and next day, and it was decided that I should go to Ottawa with the party, to assist them in furthering their views before the Government. In the meantime Dr. Canniff and other members of the party had sent word to friends at Cobourg, Belleville, Prescott, etc., to organise demonstrations of welcome to the loyalists at the different points.

A large number of our friends and sympathisers gathered at the Union Station to see the party off to Ottawa, and received them with loud cheers. Mr. [27]Andrew Fleming then moved, seconded by Mr. T. H. O’Neil, the following resolution, written by Foster, which was unanimously carried:

That we, the citizens of Toronto, in parting with our Red River guests, beg to reiterate our full recognition of their devotion to, and sufferings in, the cause of Canada, to emphatically endorse their manly conduct through troubles sufficient to try the stoutest heart, and to assure the loyal people of Canada that no minion of the murderer Riel, no representative of a conspiracy which concentrates in itself everything a Briton detests, shall be allowed to pass this platform (should he get so far) to lay insulting proposals at the foot of a throne which knows how to protect its subjects, and has the means and never lacks for will to do it.

At Cobourg, where the train stopped for twenty minutes, we were met by the municipal authorities of the town, and a great crowd of citizens, who received the party with warm enthusiasm, and with the heartiest expressions of approval. This occurred about one o’clock in the morning. The same thing was repeated at Belleville about three or four a.m., and it was considered advisable for Mr. Mair and Mr. Setter to stay over there to address a great public meeting to be held the next day. At Prescott, also, the warmest welcome was given by the citizens. Public feeling was aroused, and we then knew that we would have Ontario at our backs.

On our arrival in Ottawa we found that the Government were not at all friendly to the loyal men, and were not desirous of doing anything that we had been advocating. The first urgent matter was the expected arrival of Richot and Scott, the rebel emissaries, who were on the way down from St. Paul. I went to see [28]Sir John A. Macdonald at the earliest moment. I had been one of his supporters, and had worked hard for him and the party for the previous eight or nine years—in fact since I had been old enough to take an active part in politics; and he knew me well. I asked him at once if he intended to receive Richot and Scott, in view of the fact that since Sir John had invited Riel to send down representatives, Thomas Scott had been murdered. To my astonishment he said he would have to receive them. I urged him vehemently not to do so, to send someone to meet them and to advise them to return. I told him he had a copy of their Bill of Rights and knew exactly what they wanted, and I said he could make a most liberal settlement of the difficulties and give them everything that was reasonable, and so weaken Riel by taking away the grievances that gave him his strength. That then a relief expedition could be sent up, and the leading rebels finding their followers leaving them, would decamp, and the trouble would be over. I pointed out to him that the meetings being held all over Ontario should strengthen his hands, and those of the British section of the Cabinet, and that the French Canadians should be satisfied if full justice was done to the half-breeds, and should not humiliate our national honour. Sir John did not seem able to answer my arguments, and only repeated that he could not help himself, and that the British Government were favourable to their reception. I think Sir Stafford Northcote was at the time in Ottawa representing the Home Government, or the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Finding that Sir John was determined to receive them I said, “Well, Sir John, I have always supported you, but from the day that you receive Richot and Scott, [29]you must look upon me as a strong and vigorous opponent.” He patted me on the shoulder and said, “Oh, no, you will not oppose me, you must never do that.” I replied, “I am very sorry, Sir John. I never thought for a moment that you would humiliate us. I thought when I helped to get up that great meeting in Toronto, and carefully arranged that no hostile resolutions should be brought up against you, that I was doing the best possible work for you; but I seconded a very strong resolution and made a very decided speech before ten thousand of my fellow citizens, and now I am committed, and will have to take my stand.” Feeling much disheartened I left him, and worked against him, and did not support him again, until many years afterwards, when the leaders of the party I had been attached to foolishly began to coquette with commercial union, and some even with veiled treason, while Sir John came out boldly for the Empire, and on the side of loyalty, under the well-known cry, “A British subject I was born, a British subject I will die.”

After reporting to Schultz and Lynch we considered carefully the situation, and as Lynch had been especially requested by his fellow prisoners in Fort Garry to represent their views in Ontario, it was decided that he, on behalf of the loyal element of Fort Garry, should put their case before his Excellency the Governor-General himself, and ask for redress and protection. After careful discussion, I drafted a formal protest, which Lynch wrote out and signed, and we went together to the Government House and delivered it there to one of his Excellency’s staff. Copies of this were given to the Press, and attracted considerable attention. This protest was as follows:

Russell’s Hotel, Ottawa

12th April, 1870.

May it Please Your Excellency,

Representing the loyal inhabitants of Red River both natives and Canadians, and having heard with feelings of profound regret that your Excellency’s Government have it in consideration to receive and hear the so-called delegates from Red River, I beg most humbly to approach Your Excellency in order to lay before Your Excellency a statement of the circumstances under which these men were appointed in order that they may not be received or recognised as the true representatives of the people of Red River.

These so-called delegates, Father Richot and Mr. Scott, were both among the first organisers and promoters of the outbreak, and have been supporters and associates of Mr. Riel and his faction from that time to the present.

When the delegates were appointed at the convention the undersigned, as well as some fifty others of the loyal people, were in prison on account of having obeyed the Queen’s proclamation issued by Governor Macdougall. Riel had possession of the Fort, and most of the arms, and a reign of terror existed throughout the whole settlement.

When the question came up in the convention, Riel took upon himself to nominate Father Richot and Mr. Scott, and the convention, unable to resist, overawed by an armed force, tacitly acquiesced.

Some time after their nomination a rising took place to release the prisoners, and seven hundred men gathered in opposition to Riel’s government, and, having obtained the release of their prisoners, and declared that they would not recognise Riel’s authority, they separated.

In the name and on behalf of the loyal people of Red River, comprising about two-thirds of the whole population, I most humbly but firmly enter the strongest [31]protest against the reception of Father Richot and Mr. Scott, as representing the inhabitants of Red River, as they are simply the delegates of an armed minority.

I have also the honour to request that Your Excellency will be pleased to direct that, in the event of an audience being granted to these so-called delegates, that I may be confronted with them and given an opportunity of refuting any false representations, and of expressing at the same time the views and wishes of the loyal portion of the inhabitants.

I have also the honour of informing Your Excellency that Thomas Scott, one of our loyal subjects, has been cruelly murdered by Mr. Riel and his associates, and that these so-called delegates were present at the time of the murder, and are now here as the representatives before Your Excellency of the council which confirmed the sentence.

I have also the honour to inform Your Excellency, that should Your Excellency deem it advisable, I am prepared to provide the most ample evidence to confirm the accuracy and truth of all the statements I have here made.

I have the honour to be

Your Excellency’s most humble and obedient servant,

James Lynch.

I believe this was cabled by his Excellency to the Home Government. In the meantime Foster and our friends in Toronto were active in the endeavour to prevent the reception of Richot and Scott. A brother of the murdered Scott happened to be in Toronto, and on his application a warrant was issued by Alexander Macnabb, the Police Magistrate of Toronto, for the arrest of the two delegates, on the charge of aiding and abetting in the murder. This warrant was sent to the Chief of Police of Ottawa, with a request to have it [32]executed, and the prisoners sent to Toronto. Foster wrote to me and asked me to see the Chief of Police and press the matter. When I saw the Chief he denied having received it. I took him with me to the Post Office, and we asked for the letter containing it. The officials denied having it. I said at once that there was some underhand work, and that we would give the information to the Press, and that it would arouse great indignation. I was requested to be patient until further search could be made. It was soon found, and I went before the Ottawa Police Magistrate, and proved the warrant, as I knew Mr. Macnabb’s signature. Then the men were arrested. We discovered afterwards that the warrant had been taken immediately on its arrival to Sir John A. Macdonald, and by him handed to John Hillyard Cameron, Q.C., then a member of the House of Commons, and a very prominent barrister, in order that he should devise some method of meeting it. This was the cause of the Chief of Police denying that he had received it. Mr. Scott, the complainant, came down to Ottawa, and as we feared Mr. McNabb had no jurisdiction in the case, a new information was sworn out in Ottawa before the Police Magistrate of that City.

Richot and Scott were discharged on the Toronto warrant, and then arrested on the new warrant. The case was adjourned for some days, but it was impossible to get any definite evidence, as the loyal refugees had been in prison, and knew nothing of what had happened except from the popular report. Richot and Scott were therefore discharged, and were received by the Government, and many concessions granted to the rebels.

During the spring of 1870 there had been an agitation in favour of sending an expedition of troops to the Red River Settlement, to restore the Queen’s authority, to protect the loyal people still there, and to give security to the exiles who desired to return to their homes. The Canada First group had taken an active part in this agitation, and had urged strongly that Colonel Wolseley (now Field-Marshal Viscount Wolseley) should be sent in command. We knew that under his directions the expedition would be successfully conducted, and that not only would he have no sympathy with the enemy, but that he would not be a party to any dishonest methods or underhand plotting. He had commanded the camp of cadets at La Prairie in 1865, and had gained the confidence of them all; afterwards at the camp at Thorold in August and September, 1866, he had nearly all the Ontario battalions of militia pass under his command, so that there was no man in Canada who stood out more prominently in the eyes of the people.

Popular opinion fixed upon Colonel Wolseley with unanimity for the command, and the Government, although very anxious to send Colonel Robertson Ross, Adjutant-General, could not stem the tide, particularly [34]as the Mother Country was sending a third of the expedition and paying a share of the cost, and General Lindsay, who commanded the Imperial forces in Canada, was fully aware of Colonel Wolseley’s high qualifications and fitness for the position.

The expedition was soon organised under Colonel Wolseley’s skilful leadership, and he started for Port Arthur from Toronto on the 21st May, 1870. The Hon. George Brown had asked me to go up with the expedition as correspondent for the Globe, and Colonel Wolseley had urged me strongly to accept the offer and go with him. I should have liked immensely to have taken part in the expedition, but we were doubtful of the good faith of the Government, on account of the great influence of Sir George Cartier and the French Canadian party, and the decided feeling which they had shown in favour of the rebels. We feared very much that there would be intrigues to betray or delay the expedition. I was confident that Colonel Wolseley’s real difficulty would be in his rear, and not in front of him, and therefore I was determined to remain at home to guard the rear.

From Port Arthur, the first stage of the journey was to Lake Shebandowan, some forty odd miles. This was the most difficult part of the work. The Government Road was not finished as had been expected, and Colonel Wolseley was delayed from the end of May until the 16th July, before he was able to despatch any of the troops from McNeill’s Bay on Lake Shebandowan.

It will be seen that the expedition was delayed nearly two months in getting over the first fifty miles of the six hundred and fifty by water which lay between Prince Arthur’s Landing and Fort Garry. [35]This was caused by the fact that the first fifty miles was uphill all the way, while the remainder of the journey was mainly downhill. Sir John A. Macdonald was taken with a very severe and dangerous illness, so that during this important period the control of affairs passed into the hands of Sir George Cartier and the French Canadian party. This caused great anxiety in Ontario, for we could not tell what might happen. Our committee were very watchful, and from rumours we heard, we thought it well to be prepared, and on the 13th July, Foster, Grahame and I prepared a requisition to the Mayor to call a public meeting, to protest against any amnesty being granted to the rebels; and getting it well signed by a number of the foremost men in the city, we held it over, to be ready to have the meeting called on the first sign of treachery.

About the 18th July, 1870, Haliburton was at Niagara Falls and by chance saw Lord Lisgar, the Governor-General, and in conversation with him he learned that Sir George Cartier, Bishop Taché, and Mr. Archibald (who had been chosen as Lieutenant-Governor of the new province) were to meet him there in a few days. Haliburton suspected some plot and telegraphed warning Dr. Schultz at London, Ontario, who sent word to me, and on the 19th we had a meeting of our committee, and arranged at once for the public meeting to be held on the 22nd. In the Government organ, the Leader, of the 19th July was a despatch from Ottawa dated the 18th in the following words:

Bishop Taché will arrive here this evening from Montreal. The Privy Council held a special meeting on Saturday.

It is stated on good authority that Sir George Cartier will proceed with Lieutenant-Governor Archibald to Niagara Falls next Wednesday to induce His Excellency to go to the North-West via Pembina with Lieutenant-Governor Archibald and Bishop Taché. On their arrival, Riel is to deliver up the Government to them, and the expeditionary troops will be withdrawn.

On the next day the same paper had an article which, appearing in the official organ of the Government, was most significant. It concluded in the following words:

So far as the expedition is concerned we have no knowledge that there is any intention to recall it, but we would not be in the least surprised if the physical difficulties to be encountered should of itself make its withdrawal a necessity. How much better than incurring any expense in this way would it be for Sir John Young (Lord Lisgar) to pay a visit to the new Province, there to assume the reins of the Government on behalf of the Queen, see it passed over properly to Mr. Archibald, who is so much respected there, and then establish a local force, instead of endeavouring to forward foot and artillery through the almost impassable swamps of the long stretch of country lying between Fort William and Fort Garry. Should the Government entertain such an idea as this and successfully carry it out, the time would be short indeed within which the public would learn to be grateful for the adoption of so wise a policy.

This gave us the opportunity to take decisive action. We had already been dreading some such plot which, if successful, would have been disastrous to our hopes of opening up the North-West. If the expedition had been withdrawn, what security would the loyalist leaders have had as to their safety, after the murder of Scott, [37]and the recognition and endorsation of the murderers? It was essential that the expedition should go on. On the first suspicion of difficulty, I had written to Colonel Wolseley and warned him of the danger, and urged him to push on, and not encourage any messages from the rear. Letters were written to officers on the expedition to impede and delay any messengers who might be sent up, and in case the troops were ordered home, the idea was conveyed to the Ontario men to let the regulars go back, but for them to take their boats and provisions and go on at all hazards.

Hearing on the 19th that Cartier and Taché were coming through Toronto the next night on their way to Niagara, our committee planned a hostile demonstration and were arranging to burn Cartier’s effigy at the station. Something of this leaked out and Lieutenant-Colonel Durie, District Adjutant-General commanding in Toronto, attempted to arrange for a guard of honour to meet Cartier, who was Minister of Militia, in order to protect him. Lt.-Colonel Boxall, of the 10th Royals, who was spoken to on the subject, said he had an engagement for that evening near the station, of a nature that would make it impossible for him to appear in uniform. The information was brought to me. I was at that time out of the force, but I went to Lt.-Colonel Durie, who was the Deputy-Adjutant-General, and told him I had heard of the guard of honour business, and asked him if he thought he could intimidate us and I told him if we heard any more of it, we would take possession of the armoury that night, and that we would have ten men to his one, and if anyone in Toronto wanted to fight it out, we were ready to fight it out on the streets. He told me I was threatening revolution. I said, “Yes, I [38]know I am, and we can make it one. A half continent is at stake, and it is a stake worth fighting for.”

Lt.-Colonel Durie telegraphed to Sir George Cartier not to come to Toronto by railway, and he and Bishop Taché got off the train at Kingston. Taché went to the Falls by way of the States. Cartier took the steamer for Toronto, arrived at the wharf in the morning, transferred to the Niagara boat, and crossed to the Falls. This secrecy was all we wanted.

About the same time another formal protest was prepared and Dr. Lynch presented it to his Excellency the Governor-General:—

To His Excellency Sir John Young, Bart., K.C.B., &c., &c.,

Governor-General, &c., &c.

May it Please Your Excellency

I have on several occasions had the honour of addressing Your Excellency on behalf of the loyal portion of the inhabitants of the Red River Settlement, and having heard that there is a possibility of the Government favouring the granting of an amnesty for all offences to the rebels of Red River, including Louis Riel, O’Donohue, Lepine and others of their leaders, I feel it to be my duty on behalf of the loyal people of the territory to protest most strongly against an act that would be unjust to them, and at the same time to place on record the reasons which we consider render such clemency not only unfair and cruel, but also injudicious, impolitic, and dangerous.

I therefore beg most humbly and respectfully to lay before Your Excellency, on behalf of those whom I represent, the reasons which lead us to protest against the leaders of the rebellion being included in an amnesty and for which we claim that they should be excluded from its effects.

(1) A general amnesty would be a serious reflection on the loyal people of the Red River Settlement who throughout this whole affair have shown a true spirit [39]of loyalty and devotion to their Sovereign and to British institutions. Months before Mr. Macdougall left Canada it was announced that he had been appointed Governor. He had resigned his seat in the Cabinet, and had addressed his constituents prior to his departure. The people of the Settlement had read these announcements, and on the publication of his proclamation in the Queen’s name with the royal arms at its head, they had every reason to consider that the Queen herself called for their services. Those services were cheerfully given, they were enrolled in the Queen’s name to put down a rising that was a rebellion—that was trampling under foot all law and order, and preventing British subjects from entering or passing through British territory. For this they were imprisoned for months; for this they were robbed of all they possessed; and for this, the crime of obeying the call of his Sovereign, one true-hearted loyal Canadian was cruelly and foully murdered. An amnesty to the perpetrators of these outrages by our Government we hold to be a serious reflection on the conduct of the loyal inhabitants and a condemnation of their loyalty.

(2) It is an encouragement of rebellion. Riel was guilty of treason. When he refused permission to Mr. Macdougall, a British subject, to enter a British territory, and drove him away by force of arms, he set law at defiance and committed an open act of rebellion. He also knew that Mr. Macdougall had been nominated Governor, knew that he had resigned his seat in the Cabinet, knew he had bid farewell to his constituents; yet he drove him out by force of arms, and when the Queen’s proclamation was issued—for all he knew by the Queen’s authority—he tore it up, scattered the type used in printing it, defied it, and imprisoned, robbed and murdered those whose only crime in his eyes was that they had obeyed it. It may be said that Riel knew that Mr. Macdougall had no authority to issue a proclamation in the Queen’s name; a statement of this kind would lead to the inference that it was the [40]result of secret information and of a conspiracy among some in high positions. This had sometimes been suspected by many, but hitherto has never been believed. An amnesty to Riel and other leaders would be an endorsation of their acts of treason, robbery, and murder, and therefore an encouragement to rebellion.

(3) An amnesty is injudicious, impolitic and dangerous, if it includes the leaders. Some of those who have been robbed and imprisoned, who have seen their comrade and fellow prisoner led out and butchered in cold blood, seeing the law powerless to protect the innocent and punish the guilty, might in that wild spirit of justice, called vengeance, take the life of Riel or some other of the leaders. Should this unfortunately happen the attempt by means of law to punish the avenger would be attended with serious difficulty, and would not receive the support of the loyal people of the Territory, of the Canadian emigrants who will be pouring in, or of the people of the older Provinces. Trouble would arise and further disturbance break out in the Settlement. It would be argued with much force that Riel had murdered a loyal man for no crime but his loyalty and that he was pardoned, and that when a loyal man taking the law into his own hands executed a rebel and a murderer in vengeance for a murder, he would be still more entitled to a pardon, and the result would be that the law could not be carried out. When the enforcement of the law would be an outrage to the sense of justice of the community, the law would be treated with contempt. A full amnesty will produce this result, and bitter feuds and a legacy of internal dissension entailed upon that country for years to come.

(4) It will destroy all confidence in the administration of law and maintenance of order. There could be no feeling of security for life, liberty, or property in a country where treason, murder, robbery and other crimes had been openly perpetrated, and afterwards [41]condoned and pardoned sweepingly by the higher authorities.

(5) The proceedings of the insurgent leaders, previous to the attempt of Mr. Macdougall to enter the Territory, as well as afterwards, led many to suspect that Riel and his associates were in collusion with certain persons holding high official positions. Although suspected, it could not be believed. An amnesty granted now, including everyone, would confirm these suspicions, preclude the possibility of dissipating them, and leave a lasting distrust in the honour and good faith of the Canadian Government.

In respectfully submitting these arguments for Your Excellency’s most favourable consideration, I wish Your Excellency to understand that it is not the object of this protest to stand in the way of an amnesty to the great mass of the rebels, but to provide against the pardon of the ringleaders, those designing men who have inaugurated and kept alive the difficulties and disturbances in the Red River Settlement, and who have led on their innocent dupes from one step to another in the commission of crime by false statements and by appealing to their prejudices and passions.

I have the honour to be,

Your Excellency’s most obe’t humble Serv’t,

James Lynch.

Queen’s Hotel, Toronto,

29th June.

This was also given to the Press and widely published.

The meeting for which, as has been said, a requisition had been prepared, was called for the 22nd July, and in addition to the formal posters issued by the acting Mayor on our requisition, Foster and I had prepared a series of inflammatory placards in big type on large sheets, which were posted on the fences and bill boards all over the city. There were a large number of these [42]placards; some of them read, “Is Manitoba to be reached through British Territory? Then let our volunteers find a road or make one.” “Shall French rebels rule our Dominion?” “Orangemen! is Brother Scott forgotten already?” “Shall our Queen’s Representative go a thousand miles through a foreign country, to demean himself to a thief and a murderer?” “Will the volunteers accept defeat at the hands of the Minister of Militia?” “Men of Ontario! Shall Scott’s blood cry in vain for vengeance?”

The public meeting was most enthusiastic, and St. Lawrence Hall was crowded to its utmost limit. The Hon. Wm. Macdougall moved the first resolution in a vigorous and eloquent speech; it was as follows:

Resolved, that the proposal to recall at the request of the Rebel Government the military expedition, now on its way to Fort Garry to establish law and order, would be an act of supreme folly, an abdication of authority, destructive of all confidence in the protection afforded to loyal subjects by a constitutional Government—a death-blow to our national honour, and calls for a prompt and indignant condemnation by the people of this Dominion.

Mr. Macdougall in supporting this said that:

There were many of our own countrymen there who had been ill-treated and robbed of their property, and whose lives had been endangered. Were we to leave these persons—Whites and Indians—without support? Was this the way that our Government was to maintain its respect? How could we expect in that or any other part of the Dominion, that men would expose themselves to loss of property, imperil their lives, or incur any hazard whatever, to support a Government that makes peace with those assailing its authority, and deserts those who have defended it.

Ex-Mayor F. H. Medcalf seconded this resolution which was unanimously carried.

The second resolution called for the prompt punishment of the rebels. It was moved by James D. Edgar (afterwards Sir James D. Edgar, K.C.M.G.) and seconded by Capt. James Bennett, both members of the Canada First group.

The third resolution read:

Resolved, in view of the proposed amnesty to Riel and withdrawal of the expedition, this meeting declares: That the Dominion must and shall have the North-West Territory in fact as well as in name, and if our Government, through weakness or treachery, cannot or will not protect our citizens in it, and recalls our Volunteers, it will then become the duty of the people of Ontario to organise a scheme of armed emigration in order that those Canadians who have been driven from their homes may be reinstated, and that, with the many who desire to settle in new fields, they may have a sure guarantee against the repetition of such outrages as have disgraced our country in the past; that the majesty of the law may be vindicated against all criminals, no matter by whom instigated or by whom protected; and that we may never again see the flag of our ancestors trampled in the dust or a foreign emblem flaunting itself in any part of our broad Dominion.

In moving this resolution, I said, as reported in the Toronto Telegraph:

The indignation meeting held three months since has shown the Government the sentiments of Ontario. The expedition has been sent because of these grand and patriotic outbreaks of indignation. Bishop Taché had offered to place the Governor-General in possession of British territory. Was our Governor-General to [44]receive possession of the North-West Territory from him? No! there were young men from Ontario under that splendid officer Colonel Wolseley who would place the Queen’s Representative in power in that country in spite of Bishop Taché and without his assistance (loud cheers). We will have that territory in spite of traitors in the Cabinet, and in spite of a rebel Minister of Militia (applause). He had said there were traitors in the Cabinet. Cartier was a traitor in 1837. He was often called a loyal man, but we could buy all their loyalty at the same price of putting our necks under their heels and petting them continually. Why when he was offered only a C.B. his rebel spirit showed out again; he whined, and protested, and threatened and talked of the slight to a million Frenchmen, and the Government yielded to the threat, gave him a baronetcy, patted him on the back, and now he is loyal again for a spell (laughter and cheers).

I also pointed out how, if the expedition were recalled, we could, by grants from municipalities, &c., and by public subscription, easily organise a body of armed emigrants who could soon put down the rebels. This resolution was seconded by Mr. Andrew Fleming and carried with enthusiasm.

Mr. Kenneth McKenzie, Q.C., afterwards Judge of the County Court, moved, and W. A. Foster seconded, the last resolution:

Resolved that it is the duty of our Government to recognise the importance of the obligation cast upon us as a people; to strive in the infancy of our confederation to build up by every possible means a national sentiment such as will give a common end and aim to our actions; to make Canadians feel that they have a country which can avenge those of her sons who suffer and die for her, and to let our fellow Britons know that a Canadian shall not without protest be branded [45]before the world as the only subject whose allegiance brings with it no protection, whose patriotism wins no praise.

The result of this meeting, with the comments of the Ontario Press, had their influence, and Sir George Cartier was obliged to change his policy. The Governor-General, it was said, took the ground that the expedition was composed partly of Imperial troops, and was under the command of an Imperial officer, and could not be withdrawn without the consent of the Home Government. Sir George Cartier then planned another scheme by which he hoped to condone the crime which Riel had committed, and protect him and his accomplices from the punishment they deserved.

This plan, of course, we knew nothing of at the time, but it was arranged that Mr. Archibald was to follow the Red River expedition over the route they had taken, for the purpose apparently of going to Fort Garry along with the troops. It was also planned that, when Mr. Archibald arrived opposite the north-west angle of the Lake of the Woods, he was to turn aside, and land at the point where the Snow Road (so called after Mr. Snow, the engineer in charge of the work) was to strike the lake, and proceed by land to Fort Garry. Riel was to send men and horses to meet Mr. Archibald at that point, and he was to be brought into Fort Garry under the auspices of the Rebel Government, and take over the control from them before the expedition could arrive.

This is all clearly shown by two letters from Bishop Taché to Riel, which were found among Riel’s papers in Fort Garry after his hurried flight. They are as follows:

Letter No. 1.— Bishop Taché to President Riel.

Monsieur L. Riel, President,

I had an interview yesterday with the Governor-General at Niagara: he told me the Council could not revoke its settled decision to send Mr. Archibald by way of the British Possessions, and for the best of reasons, which he explained to me, and which I shall communicate to you later. We cannot therefore arrive together, as I had expected. I shall not be alone, because I shall have with me people who come to aid us. Mr. Archibald regrets he cannot come by way of Pembina; he wishes, notwithstanding, to arrive among us, and before the troops. Therefore he will be glad to have a road found for him either by the Point des Chenes or the Lac de Roseaux. I pray you to make enquiry in this respect, in order to obtain the result that we have proposed. It is necessary that he should arrive among and through our people. I am well content with this Mr. Archibald. I have observed that he is really the man that is needed by us. Already he seems to understand the situation and the condition of our dear Red River, and he seems to love our people. Have faith then that the good God has blessed us, notwithstanding our unworthiness. Be not uneasy; time and faith will bring us all we desire, and more, which it is impossible to mention, notwithstanding the expectations of certain Ontarians. We have some sincere, devoted and powerful friends.

I think of leaving Montreal on the 8th of August, in which case it is probable I shall arrive towards the 22nd of the same month.

The letter which I brought has been sent to England, as well as those which I have written myself, and which I have read to you.

The people of Toronto wished to make a demonstration against me, and, in spite of the exaggerated statements of the newspapers, they have never dared to give the number of the persons present (?). Some [47]persons here at Hamilton wished to speak, but the newspapers discouraged their zealous efforts.

I am here by chance, and remain, as this is Sunday. Salute for me Mr. O. [O’Donohue?] and others at the Fort. Pray much for me. I do not forget you.

Your Bishop, who signs himself your best friend,

A. G. de St. Boniface.

Letter No. 2.— Bishop Taché to President Riel.

Bourville, 5th August.

M. Le Président,

I well know how important it is for you to have positive news—I have something good and cheering to tell you. I had already something wherewith to console us when the papers published news dear and precious to all our friends, and they are many. I shall leave on Monday, and with the companions whom I mentioned to Rev. P. Lestang. Governor Archibald leaves at the same time, but by another road. He will arrive before the troops, and I have promised him a good reception if he comes by the Snow Road. Governor McTavish’s house will suit him, and we will try to get it for him. Mother salutes you affectionately, as also my uncle. Mlle. Masson and a crowd of others send kind remembrances to your good mother and sisters. Forget not Mr. O. and others at the Fort. We have to congratulate you on the happy result. The Globe and others are furious at it. Let them howl leisurely—they excite but the pity and contempt of some of their friends. Excuse me—it is late, and I am fatigued, and to-morrow I have to do a hard day’s work.

Yours devotedly,

A. G. de St. Boniface.

These letters prove the plot and the object of it. There was also a most compromising letter from Sir [48]George Cartier, which was taken away while Colonel Wolseley was a few minutes out of his room, attending to some urgent business. The suspicion was that it was taken by John H. McTavish, of the Hudson’s Bay Company.