* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Reminiscences of a Raconteur

Date of first publication: 1921

Author: George H. Ham (1847-1926)

Date first posted: Aug. 13, 2014

Date last updated: Aug. 13, 2014

Faded Page eBook #20140822

This ebook was produced by: David T. Jones, Al Haines. Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

GEORGE H. HAM.

(From a recent photograph)

REMINISCENCES

OF A

RACONTEUR

Between the ’40s and the ’20s

BY

GEORGE H. HAM

Author of “The New West” and “The Flitting of the Gods”

TORONTO

THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY

LIMITED

Copyright, Canada, 1921

THE MUSSON BOOK CO., LIMITED

PUBLISHERS TORONTO

MUSSON

ALL CANADIAN PRODUCTION

To

RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD SHAUGHNESSY, K.C.V.O.,

of Montreal, Canada, and of Ashford, County

Limerick, Ireland,

This book is respectfully dedicated

in grateful remembrance of many

kindnesses in the vanishing past.

CONTENTS

| I. | Seventy Years Ago—My Early Days in Kingston and Whitby—Boyhood Friends—Unspared Rods—Better Spellers Then than Now—A Cub Reporter—Other Jobs I Didn’t Fill—Failure to Become a Merchant Prince—Put Off a First Train |

| II. | A Momentous Election—Meeting Archie McKellar—Go on the Turf—A Sailor Bold—A Close Shave—Stories of Pets—An Exaggerated Report—Following Horace Greeley’s Advice—And Grow Up with the Country |

| III. | Winnipeg a City of Live Wires—Three Outstanding Figures—Rivalry Between Donald A. and Dr. Schultz— Early Political Leaders—When Winnipeg was Putting on its First Pants—Pioneer Hotels—The Trials of a Reporter—Not Exactly an Angelic City—The First Iron Horse—Opening of the Pembina Branch—Profanity by Proxy—The Republic of Manitoba—The Plot to Secede |

| IV. | The Big Winnipeg Boom—Winnipeg the Wicked—A Few Celebrated Cases—Some Prominent Old-Timers—The Inside Story of a Telegraph Deal—When Trouble Arose and Other Incidents |

| V. | The Boys are Marching—The Trent Affair—The Fenian Raid—The Riel Rebellion—A Dangerous Mission—Lost on the Trail—The First and Last Naval Engagement on the Saskatchewan—Rescue of the Maclean Family—A Church Parade in the Wilderness—Indian Signals |

| VI. | Governors-General I Have Met—Dufferins and the Icelanders—The Marquis of Lorne and Wee Jock McGregor—Unpleasantness at Rat Portage—Kindness of Princess Louise—Lord Landsdowne at the Opening of the Galt Railway “My” Excellent Newspaper Report—Talking to Aberdeen—Minto, the Great Horseman—Earl Grey a Great Social Entertainer—The Grand Old Duke and Princess Pat—The Duke of Devonshire |

| VII. | The Hudson’s Bay Company—A Tribute to its Officers—Intrepid Scotch Voyageurs—Daily Papers a Year Old—Royal Hospitality of the Factors—Lord Strathcona’s Foundation for His Immense Fortune—The First Cat in the Rockies—Indian Humor and Imagery |

| VIII. | Around the Banqueting Board—My First Speech—At the Ottawa Press Gallery Dinners—A Race With Hon. Frank Oliver—A Homelike Family Gathering—A Scotch Banquet—Banquets in Winnipeg—Bouquets and Brickbats—The Mayor of New York and the Queen of Belgium |

| IX. | In the Land of Mystery—Planchette and Ouija—Necromancers and Hypnotists and Fortune Tellers—Adventures in the Occult—A Spirit Medium—Mental Telepathy—Fortune Telling by Tea Cups and Cards—Living in a Haunted House |

| X. | Mark Twain, the Great Humorist—A Delightful Speaker—A Chicago Cub Reporter’s Experience—The Celebrated Cronin Case—W. T. Stead and Hinky Dink—When the Former Wrote “If Christ Came to Chicago” |

| XI. | The Canadian Women’s Press Club—How It Originated—With “Kit” of the Toronto Mail at St. Louis and Elsewhere—The Lamented “Francoise” Barry—Successful Triennial Gatherings—The Girls Visit Different Paris of Canada—Threatened Invasion of the Pacific Coast |

| XII. | When Toronto Was Young—The Local Newspapers—The Markham Gang—Some Chief Magistrates of the City—Ned Farrer, the Great Journalist—Theatrical Recollections—Old-Time Bonifaces—And Old-Time Friends.—Toronto’s Pride |

| XIII. | Scarlet and Gold—The Rough Riders of the Plains—The Fourth Semi-Military Force in the World—Its Wonderful Work in the Park—Why the Scarlet Tunic Was Chosen—Some Curious Indian Names—Primitive Western Justice |

| XIV. | In the Hospital—Averting a Shock—A Substantial Breakfast—A Gloomy Afternoon—Down in Washington—The Gridiron Dinners—A Spanish-American War Panic—A Few Stories—Canadian Club |

| XV. | Christmas and Its Cheer—Will Sell Anything for Gin But Children’s Christmas Stockings—Santa Claus No Myth—Dreary Christmas—Mr. Perkins’ Cutter—A Lively Christmas Gathering—Tiny Tim’s Blessing |

| XVI. | The Miracle Man of Montreal—Brother Andre Whose Great Work Has Done Great Good—A Youth With a Strange Power—Authentic Accounts of Some of the Miracles—All Faiths Benefited by Him |

| XVII. | Political Life in Canada—Its Tragedies and Its Pleasantries—The Great Outstanding Figures of the Past—The Social Side of Parliament—Mixed Metaphors and People Who Were Not Good Mixers—A Second Warwick—The Wrong Hat—And Other Incidents |

| XVIII. | The Great Northern Giant—The Early Days of the C.P.R. and its Big Promoters—Where the Aristocracy of Brains Ruled—A Huge Undertaking and a Broad Policy—A Conspicuously Canadian Enterprise—Something About the Men Who Ruled—My Fidus Achates—Captains Courageous—The Active Men of To-Day—And Interesting Facts About the C.P.R. |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

George H. Ham (From a recent photograph)

Some Early Photographs of George H. Ham

The New and the Old C.P.R. Stations in Winnipeg

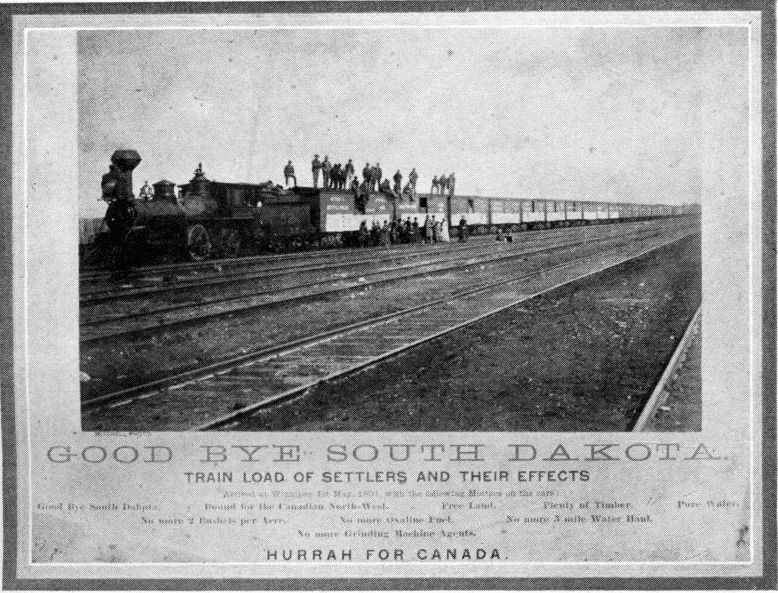

How Our Early Settlers Arrived in Winnipeg

The Duke and Duchess of Connaught with Princess Patricia

The Duke and Duchess of Devonshire and Daughters the Ladies Cavendish

Lord Minto at His Lodge, Kootenay

Some Early Trading Posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company

Waterfront, Toronto, Eighty Years Ago

Fish-Market, Toronto, Eighty Years Ago

Seventy Years Ago—My Early Days in Kingston and

Whitby—Boyhood Friends—Unspared Rods—Better

Spellers Then than Now—A Cub

Reporter—Other Jobs I Didn’t Fill—Failure

to Become a Merchant

Prince—Put Off a First Train

It has been said by facetious friends that I have several birthplaces. However that may be, Trenton, Ontario, is the first place where I saw light, on August 23rd, 1847, and on the spot where I was born has been erected a touching memorial in the shape of a fine hotel, which was an intimation, if we believe in fate or predestination, that my life should be largely spent in such places of public resort. After events confirmed this idea. Hotels have been largely my abiding place, from London, England, to San Francisco, and from the city of Mexico and Merida in Yucatan as far north as Edmonton.

My father was a country doctor, but, tiring of being called up at all hours of the night to attend a distant kid with the stomach-ache, or a gum-boil, wearied and disgusted with driving over rough roads in all sorts of weather to visit non-paying patients, he gave up the practice of medicine, studied law, passed the necessary examinations, and in 1849 moved to Kingston and was associated with Mr. (afterwards Sir) John A. Macdonald. Two years later he was appointed a sort of Pooh-bah at Whitby, Ontario, when the county of Ontario was separated from the county of York, as part and parcel of the then Home District. When questioned about my early life, it was usual for inquisitive friends to ask: “How long were you in Kingston?” And my truthful answer—“Just two years”—invariably evoked a smile and the satirical remark that that was about the usual sentence.

My first recollections in babyhood were of my arm being vaccinated before I was three years old, and to mollify any recalcitrancy—I didn’t know what that word meant then—a generous portion of fruit cake thickly covered with icing was diplomatically given me. I immediately shoved out my other arm for another dose of vaccine with the cake accompaniment, but it didn’t work. Another recollection is my going out with my sister Alice to see a military parade. We took along the family’s little kitten carefully wrapped in my sister’s new pelisse. At the corner of Princess and Bagot streets, the martial music of the band frightened pussy and with a leap she disappeared under an adjoining building, pelisse and all. That’s seventy-odd years ago, but every time I visit Kingston, even to this day, I watch around Bagot street to see if the cat’s come back. Which she hasn’t; nor has the pelisse. Curious to relate, the C.P.R. office now occupies the site of my boyhood home.

Whitby was first called Windsor, and I have a map drawn in 1841, on which that name appears. It was changed shortly after. School days at Whitby, at the primitive district Henry Street school, were just about the same as those of any other school boy; and the pleasurable monotony was only broken by such events as the school-house catching fire, or the teacher being ill, which granted us a few real honest-to-goodness holidays. Some of us deeply regretted that the darned old place hadn’t burned down altogether, as the holidays would then have been prolonged indefinitely. Snowballing matches between the Grammar and District schools kept the boys busy, during favorable winter weather, and it was only when the snow disappeared that one school did not invade the precincts of the other, sometimes with disastrous effects. These affairs were not Sunday school picnics, and no quarter was ever asked or given. One of the Grammar army got plugged in the ear in a severe combat by a snowball in which was enclosed a good-sized stone, and when he was keeled over, there was no first aid to the wounded, but a savage reprisal. Cricket was also a favorite game, but it was not aggressive enough. Football and shinny—especially on the ice, where the Town and the Bay met every Saturday for a whole day’s conflict—afforded more and better opportunities for personal encounters and were more popular games. The goals were a mile apart, and I never knew of a game being scored by either side. Golf, croquet and similar sports were unknown, but would have been scorned as too insipid. But we played One-old-cat and Two-old-cat—predecessors of baseball. Prisoner’s base gave fine opportunities for running and wrestling, and had many devotees. Don’t think that the boys were any rougher than the boys in any other school, but in the glorious old days rough and tumble was usually preferred to more sedate and lady-like games.

There were some pretty bright boys who graduated from those schools and made a name for themselves in the world. John Dryden became Minister of Agriculture for Ontario; Johnny Bengough, who was always handy with his pencil, evolved into a great cartoonist and published Grip in Toronto; Hamar Greenwood, who had a great gift of the gab, went to England, was knighted, and appointed Chief Secretary of State for Ireland; Jack Wetherall went to New York and achieved position and wealth as an advertising manager for Lydia Pinkham, whose female pills are peerless and unparalleled (so he says); Dick Blow became mayor of the town; Jim Bob Mason—his name wasn’t Jim Bob, but that’s what we called him—went to the States where his son, Walt Mason, I am informed, is making a fortune writing popular prose poems. D. F. Burke (we called him Dan) went to Port Arthur, and when he died a few years ago left two widows and a big estate, thus distancing most all his old comrades in worldly good fortune. Dan got a charter for the Port Arthur & Hay Lake Railway, and used to be chaffed over its construction equipment, which jealous-minded people like ex-Mayor George Graham of Fort William and myself said consisted of a mule and a bale of hay, and that when the mule had eaten all the hay, both the charter and the mule expired. George Dickson was one of the prize pupils and afterwards became principal of Upper Canada College, and Billy Ballard won equal distinction in educational work at Hamilton. George Bruce was a model pupil, entered the ministry, and afterwards when I heard him preach in a Presbyterian church, I felt like giving him three cheers. Danforth Roche was a stolid scholar in the school, but when he struck out for himself, he had the biggest departmental store north of Toronto, at Newmarket, and was one of the most enterprising and extensive advertisers in the Province. Joe White is town clerk at Whitby, and a mighty good one. Abe Logan went to the Western States and accumulated a fortune. Frank Warren, who recently passed away, stayed at home, entered the medical profession, and became mayor of the town. Frank Freeman, who belonged to the Freeman Family Band, consisting of father, two sisters and himself—real artists—is still a musician, and I came across him leading the orchestra at Tom Taggart’s big hotel at French Lick Springs, Indiana, a couple of years ago. Fred Lynde went to Madoc in Hastings County, and was successful in the mercantile business. George D. Perry is manager of the Great Northwestern Telegraph Co., and his brother Peter a successful educationalist in Fergus, Ontario. George Ray went to Manitoba and became reeve of a municipality. Bob Perry became a C.P.R. representative at Bracebridge, Ontario, and his brother Jack is a well-to-do resident of Vancouver. Jimmy Lawlor is in the Government service at Ottawa, and Tommy Bengough is one of the best official stenographers in the employment of the same city. The Laing boys became lost to sight. Andrew Jeffrey, Harry Watson and Bill McPherson followed the crowd that went to Toronto, and the sister of the latter name married well, Jessie McPherson becoming the wife of Dr. Burgess, superintendent of the hospital for the insane at Verdun, just outside of Montreal. Jimmy Wallace went to Chicago and entering the audit department of one of the big railway companies forged to the front, and Billy Wolfenden, who unknown to his parents used to steal away at night to learn telegraphy and railway work at the Grand Trunk offices, went west suddenly and finally became General Passenger Agent for the Père Marquette road. When the U. S. Administration took over all the railroads a few years ago, he was appointed to a similar position for his region. John A. McGillivray became a member of Parliament and chief secretary for the Order of Foresters. “Adam at Laing’s” was the only name that Adam Borrowman was known by for years, Laing’s being the largest general store in the town. Now he is more than comfortably fixed near Chicago. The Laurie boys went to Manitoba, started business and farming at Morris and prospered. John H. Gerrie went West, and is now managing editor of the San Francisco Bulletin. Harry McAllan went to Toronto, and then to Montreal, where he is in business.

Later on, Georgie Campbell and her sister, Flo, became brilliant and very popular stars on the American stage as May and Flo Irwin. Many is the time I dandled May on my knee. The last time I saw her, she had become “fair, fat and forty,” and I fear my old rheumatic limbs would now prevent me from repeating the pleasing operation. There are many others that I cannot recall, scattered all over the inhabited globe. Some have gone to the Great Beyond, and of those living the bright eyes by this time have grown dim and the various shades of hair have turned gray, but in my heart of hearts, I believe that if we could only turn back the universe and regain us our youth, there would be general rejoicing amongst us could we gather together.

The law was proposed to be my profession—after graduating from Toronto University—but as there were very few who were learned in legal lore and had achieved high distinction and greatly accumulated wealth in the immediate vicinity, I baulked, and went into newspaper-work in the old Chronicle office at Whitby.

One reason for this was my previous experience. When I was a mere kid and visiting grandfather’s old home at South Fredericksburg, opposite the upper gap of the Bay of Quinte, that venerable ancestor of mine confided in me that he wished to make his will without the knowledge of the rest of the family and suggested that I should draw up the document. In school-boy hand the will was drawn up, and while it suited grandfather all right enough, I wasn’t so cocksure it was in the right form and phraseology. So I commandeered a horse the next day and stole off to Napanee, eighteen miles away, and called upon Mr. Wilkinson, afterwards Judge Wilkinson, whom I had met at my father’s house in Whitby. He pronounced the will to be perfectly legal, and, having all of $2.00 in my pocket, I rather ostentatiously asked him his fee.

“Nothing, he smilingly replied. “Nothing at all—we never charge the profession anything—never.”

And thus I was able to get an elaborate twenty-five cent dinner at the hotel. So when the question of my future came up, I thought if it was so blamed easy to be a lawyer, I wanted something harder.

There were stricter teachers in the late fifties and early sixties than there are to-day and the “ruler” was more frequently and generously applied. I got my full share. One day I was unmercifully punished, and for a wonder, I didn’t deserve it. In my wrathful indignation, I told the teacher, a Mr. Dundas, a fine, scholarly Scotchman of the best old type, that I was only a boy, but that when I grew up I was going to kill him. That threat didn’t go with him, and he again vigorously applied the ruler to different parts of my aching anatomy. I dared not go home and tell of this, or I would have run the chance of another whipping—for there were no curled darlings then who could successfully work upon the mistaken sympathies of indulgent but foolish parents. When I had grown up and returned on a visit to Whitby, I met my good old stern teacher and reminded him of my threat. He had not forgotten it. But I told him I wished he would, for he had not thrashed me half as much as I deserved, generally speaking. I put my arms around him, and the tears that flowed down his furrowed cheeks told me I was forgiven. We had veal pot-pie for dinner that night.

I didn’t succeed as well in another episode, when a pupil at the Grammar School, the principal of which was the lamented Mr. William McCabe, afterwards manager of the North American Life Assurance Company in Toronto. We used to call it “playing hookey” in those days when a pupil absented himself from school to loaf around the swimming hole at Lynde’s creek and ecstatically swim and fish the whole day. A note from one’s parents was always a good excuse and my beloved mother, in the kindness of her heart, never failed to provide me with one. But Mr. McCabe got a little leery of these numerous maternal excuses, and insisted I should get a note from my father, which placed me in an uncomfortable fix. It was either expulsion or a paternal note. I explained to father as plausibly as I could and got the note—which was, it struck me, altogether too freely given. Fortunately I could read it by placing it against the light, and it briefly but unmistakably read:

“William McCabe, Esq.—

Please lick the bearer, (sgd.) John V. Ham.”

I had rather an uncomfortable quarter of an hour wending my way to school, when a short distance from that place of learning, I saw a brother scholar, Paddy Hyland, coming up another street. Before he caught up to me, I was limping like a lame duck. Poor Paddy, in the goodness of his great Irish heart, sympathetically asked me what was my trouble, and without a qualm of conscience, I tersely but mendaciously told him:

“Sprained my ankle.”

“Poor old fellow,” said Paddy, and he carefully and gently helped me along to school. “Can I do anything for you?” he asked in great distress at my supposed misfortune.

“You can, Paddy. Just take this note to Mr. McCabe.”

On reaching school I sank into my seat at the rear of the room. Paddy promptly presented the note, and I eagerly awaited the outcome of the interview. Mr. McCabe had a keen sense of humor, and I saw a smile come over his face as he read the note. Then he called to me:

“Here, you, come up here.”

I hobbled up. He tried to look sternly at me and said:

“It’s all right this time, but don’t you try it on me again.”

My sprained ankle miraculously improved immediately.

Any old-timer will tell that the scholars of half-a-century ago could, generally speaking, spell words in the English language better than those of to-day. It is my experience anyway, after trying out a hundred or more applicants for positions as stenographers when the result was that over fifty per cent. couldn’t spell any better than the once-famous Josh Billings, the American humorist. The reason why? The old-fashioned “spelling down” that occupied a large portion of Friday afternoon exercises has been abolished. That reminds me that in other schools—one at Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, some years ago, one exercise was for the teacher to call a letter of the alphabet, and the pupils pointed to would respond by naming a city whose initial letter was the one mentioned; thus “A” would be Almonte or Albany; “B” Battleford or Buffalo or Bowmanville; “C” Calgary; and so it went down the list until “F” was called, and a young hopeful who afterwards became an M.P., shouted “Filadelphia”. That closed the afternoon’s exercises.

As we grew up, we youngsters loafed around the street corners or gathered at some store or other convenient meeting place in the evening as boys in other towns did. Later on I spent my nights in the library of the Mechanics’ Institute when, with good old Hugh Fraser and J. E. Farewell, now county attorney, and a full-fledged colonel, we discussed all sorts of social problems and political matters until the cocks began to crow. Then we trudged home in the early dawn, each one perfectly content that he had mastered the others in the discussion, or at any rate had settled many disturbing questions finally and for good, though I am afraid many of them are alive still. My nightly association with these two old friends, both some years my senior and with a few other friends, was of great advantage to me in after life. For one thing, it taught me to be tolerant of other persons’ opinions, that there are always two sides to a question, and that there is nobody alive who can be cocksure of everything like the chap who was absolutely positive that there was only one word in the English language commencing with “su” that was pronounced “shu” and that was “sugar”, but wasn’t so confoundedly certain when quietly asked if he was “sure” of his assertion.

My first assignment on the Chronicle happened this way: While working on the case I had taught myself a hybrid sort of shorthand, which any competent stenographer nowadays would look upon as a Chinese puzzle. Mr. W. H. Higgins, a clever and experienced newspaper man of more than local reputation, composed the sole editorial and reportorial staff, and one day there were two gatherings—a special meeting of the County Council at Whitby and a Conservative convention at Brooklin, six miles north—and only one Mr. Higgins. My opportunity came. In despair at not getting a more suitable representative, he unwillingly sent me to Brooklin. Well, say, when I turned in my report early Monday morning, the boss was astounded. No wonder, I wrote and rewrote that blessed report during all Saturday night, and the greater part of Sunday and it wasn’t till near dawn on Monday that it was finished. And after all it only filled three columns. Any experienced reporter would have written it within three or four hours. I was paid $5.00 for the report, and it wasn’t so much the money I cared for as the encouraging words Mr. Higgins gave me. Thereafter I reported the town council, and brought in news items—frequently written and rewritten and then written again—and some not only written but absolutely rotten—and my salary was increased to eight dollars a week, but I kept on the case at the same time.

Failing in health—although apparently robust and strong—inducements of future wealth lured me to Walkerton, way up in Bruce County, where an old friend of the family, Mr. Ed. Kilmer, kept a general store. I was to be a partner, after a little experience behind the counter. That partnership never materialized. I used to practise on tying up parcels of tea and coffee and sugar, and, somehow or other, I would invariably put my thumb clumsily through the paper, and have to start all over again. I could sell axes and bar iron all right enough, but everyone wasn’t buying those articles. One day a lady had me take down the greater part of the dress goods on the shelves and always wanted something else than what was in stock. My patience was exhausted, so I went to Mr. Kilmer, and suggested he should attend to the lady, mentioning incidentally that I honestly believed baled hay was really what she needed—and forthwith resigned. As a complete failure as a clerk in a general store, I always prided myself that I was a huge success. But I left town the next day, and never became a merchant prince.

To indulge in outdoor life, the townships of Darlington and East and West Whitby were traversed by me as sub-agent for a farmers’ insurance company. There was not much difficulty in securing renewals of policies, but it was uphill work to get new business. The general excuse for refusal to insure was that Mr. Farmer had been insured before and had never made anything out of it. My throat used to get dry as a tin horn in trying to explain that the company couldn’t exactly guarantee a “blaze”, but the insurance policy was to protect the insure in case of fire. Perhaps, glibness of tongue was not one of my long suits, and the work did not appeal to me. Consequently I sent in my resignation and returned to more congenial work.

In the fall of 1856, the town schools had a holiday, because on that day the first railway passenger train was to arrive at Whitby. The pupils were assembled up town at the High School, then called the Grammar School. The Public School pupils led the procession, preceded by the town band, and the Grammar School formed the rear of the column, under command of Mr. William McCabe, who was then the only teacher in the Grammar School. Arriving at the station, we were lined up alongside the track. About 3 p.m. a train with three passenger cars arrived from Toronto, filled with invited guests. The locomotive was decorated with flags, and on the front and sides was a piece of bunting on which was painted the words “Fortuna Sequitur.” We were ordered to make a note of these words and produce a translation thereof on the following day. We generally agreed that “Let or may fortune follow” was about the meaning of these Latin words. The train moved on to Oshawa where John Beverley Robinson and others delivered addresses.

On the return of the train from Oshawa, a number of school boys boarded the car during the stoppage at Whitby, and then occurred the first and only time I was ever put off a train. I was bound to make the trip to Toronto as I had never experienced a ride on a railway train. The conductor put my brother, four years my senior, and myself off the rear end of the car. We ran to the front end, only to be again ejected. This was a little discouraging, I will candidly admit, but we made another bolt for the front entrance, and when the irate conductor threateningly ordered us off, some of the compassionate passengers told him to give the boys a show, which he grudgingly did; and to Toronto we went. In the other cars, the invited guests protested against the invasion of the Whitby youths, but they, too, notwithstanding the threats and warnings of the conductor, stuck to the train. Neither my brother nor myself had a cent, but that didn’t worry us at all, and when we arrived in Toronto, it was after dusk. No one knew when the train would leave for Whitby, and so we had to sit in that car, hungry as bears, until good old Hugh Fraser of Whitby loomed up about ten o’clock with some crackers and cheese, after which we didn’t care a continental what old time the train would leave. Crackers and cheese are very invigorating. The other fellows pooled all the money they had and Jack Wall (afterwards Dr. John Wall of Oshawa), who had been attending college in Toronto, rustled some more crackers and cheese, which seemed to be the sole and only article of food on the menu that night. The clock struck 4 a.m. as we reached home, completely tired out but happy as clams. I was the first boy at school next morning and was the hero of the day. Rides on railways then were big events of the mightiest importance. Don’t care so much for them now. I remember that the G. T. R. car was No. 2, and a third of a century later I again rode in the same old car, then on the Caraquet Railway in New Brunswick. But as I had a pass the conductor did not dare throw me off once—let alone twice.

A hot battle was waged between Gordon Brown, of the Globe, and a member of the Grand Trunk engineering staff, as to the road and its equipment and as to its time-table for the excursion train. No one was hurt, although threats were made, and it is alleged that the Grand Trunk engineer sent a challenge to the editor of the Globe, which he did not accept or pay any attention to, except by publishing it in the Globe.

A Momentous Election—Meeting Archie McKellar—Go

on the Turf—A Sailor Bold—A Close

Shave—Stories of Pets—An Exaggerated

Report—Following Horace Greeley’s

Advice—And Grow Up with the

Country.

A momentous election was that in South Ontario in 1867—the first one held after the Confederation of Canada had been consummated.

Hon. George Brown, of the Globe, the leader of the Reform party, was standing. The riding had always been staunchly Reform and had returned Oliver Mowat and other Reformers by sweeping majorities. In an election two years previously Hon. T. N. Gibbs, of Oshawa, the Independent Liberal candidate, had joined hands with Sir John Macdonald, whose coalition with Hon. George Brown had not been long-lived, and won. This election was to be a test one, and upon its result depended whether the new Canada should be under Liberal-Conservative or Reform rule. There was open voting in those days, and two days’ polling, it being generally conceded that the candidate who headed the poll on the first day would be the winner. Meetings were held nightly throughout the riding, and the greatest excitement prevailed during the campaign. I was too young to have a vote then, but I had a good deal to say. There were others. Canvassing of votes was kept up continuously and large sums of money were expended. It was necessary in a good many cases to pay men to vote for their own party. On the night of the first day’s polling, I was with Jimmy Cook, then of Robertson & Cook, of the Toronto Telegraph, who was a practical telegrapher. The returns, as Mr. Brown figured them out, gave him a majority of 11, with one poll to hear from. Complete returns, as Jimmy Cook got them, gave Brown a majority of one. But while that was practically an even break, the Reformers were in great glee, and while they were celebrating the Liberal-Conservatives got down to work and arranged for relays of teams to bring the distant voters the next day to the polls. At three o’clock next afternoon the Union Jack went up in front of Jake Bryan’s Tory Hotel—there were Grit and Tory hotels then—and at the close of the poll Gibbs had a majority of 69.

Mr. Brown started for his Toronto home on the following afternoon train, and while at the Whitby station walked up and down the platform with a friend. A man named Jago, an employee of the railway, who had had a serious personal difference with the defeated candidate, was in the waiting room, and on Mr. Brown passing the door, he would stick his head out and tauntingly shout:

“You got licked, Mr. Brown, you got licked.”

Brown kept walking and Jago kept on taunting him upon his defeat. This at last so exasperated the Honorable George, that he made a dash for Jago and grabbed him by the lapels of the coat. But just then the train came in, friends interfered, the conductor shouted, “All aboard” and Mr. Brown was hurried to his coach. It was, of course, reported all over the country that Brown had assaulted the man and grievously injured him, which wasn’t true.

The country gave Sir John Macdonald a majority of only 20; many of us wondered what would have been the result if Mr. Brown had carried South Ontario.

SOME EARLY PHOTOGRAPHS OF GEORGE H. HAM.

There was a provincial election on the same day when Dr. McGill, the Reform candidate, who afterwards was one of the Nine Martyrs, pilloried by the Globe, won by the handsome majority of 308. At the election in 1871, Abram Farewell, as a straight Reformer, defeated Dr. McGill by 98 votes, and in 1875, N. W. Brown, a local manufacturer, and a straight Conservative, beat Farewell by 33 votes, and four years later, John Dryden, Reformer, defeated Mr. Brown by 382 votes. South Ontario certainly was not wedded to any particular set of political gods in those days—nor is it now.

It was in one of these campaigns that a nice looking gentleman of middle age called the Gazette office and politely asked to see the exchanges. I had no idea of his identity, and we soon entered into an interesting conversation. He asked me my honest opinion of the leading politicians and I with the supreme wisdom and unsuppressible ardor of youth, fell for it. I was a red hot Tory and what he didn’t learn of the Grits from me wasn’t worth knowing. I particularly denounced Archie McKellar, who I termed the black sheep of the political crew at Toronto, and vehemently proceeded to inform him of all that gentleman’s political crimes and misdeeds. He encouraged me to go on with my abusive fulminations, and he went away smiling and told me it was the most pleasant hour he had spent in a long time. I was present at the public meeting that afternoon in my capacity as reporter—for in those days, the editor was generally the whole staff—and was sickeningly astounded when to repeated calls for “Archie McKellar”, my pleasant visitor of the morning arose amidst the loud plaudits of his political supporters. I—say, let’s draw the curtain for a few minutes. After the meeting I met Mr. McKellar and apologized for my seeming rudeness, but he only laughed pleasantly at my discomfiture, and told me how he had thoroughly enjoyed our morning seance and that he really didn’t fully realize before how wicked he was until I picturesquely and vividly depicted his deep, dark, criminal, political career. We became fast friends, and I soon learned that Archie was not nearly as black as he had been painted, as perhaps none of us are—nor as angelic.

Whitby in the early days was also a great horse-racing centre. There was a mile track up near Lynde’s Creek, which attracted large numbers of sports from all parts of the country—but the number of non-paying spectators, who drove into town and hitched their wagons just outside the fence, was also very large. Nat Ray, and the Ray boys of Whitby, were the leading local sports, and Quimby and Forbes, of Woodstock, were the pool sellers, and such men as Joe Grand, Bob Davies, and Dr. Andrew Smith, Toronto; John White, M.P. for Halton; Roddy Pringle of Cobourg; W. A. Bookless of Guelph, and Gus Thomas of Toronto, were regular attendants. Purses of $400 downwards, big sums in those days, were offered. Black Tom, Charlie Stewart, Lulu, Storm, Jack the Barber, were amongst the horses that ran. Black Tom—Nat Ray’s horse—could trot in 2.40, which was then a good record. Storm—oh, well Storm—it was an appropriately named horse. It was raffled and Jack Stanton—Jack was starter for years at the Ontario Jockey Club in Toronto, and was as good a sport as ever lived—and a couple of other fellows and I had the good or bad fortune to win it. Storm was contrary as a petulant maid, and when we had no money on her would win hands down, and when we bet our last nickel—good-bye to our money. I lost all my little money on Storm, and willingly gave Jack Stanton my share in the contrary horse. If I remember aright, he came out about even. Jack always smoked a certain grade of cigars, which then sold at five cents, and thought they were the best in the land. In after years, when I had recuperated financially, I would bring him up some special Havanas, which cost twenty-five cents, and give him one, just to see him light it, and, while I wasn’t looking, throw it away in disgust, and light one of his own ropes, which he really enjoyed. How I delighted in Jack telling me that the cigar was a fine one, he presuming that I would think he meant the twenty-five-cent cigar, and I knowing he was referring to his nickel nicotine.

Then the sports in town for the races played poker at night at the office of Nat Ray’s livery stable. The first night I played, and in the first hand, I had a pair of deuces, and so green was I that when Charlie Boyle made a raise of $5.00 I senselessly stayed, drew three cards and with the luck of a greenhorn pulled in the two other deuces. Charlie filled his two pair, and had a full house. He bet $5.00 and I, thinking I had two pair, and not knowing their value raised him $5.00. Finally he called and threw down his ace full. I said I had two pair and when I showed the two pair—of deuces—there was a general hilarity; Charlie said he had never in his life ran up against a greenhorn who didn’t beat him. I didn’t know that my two-pair were fours. I cleaned up $65.00 that night and thought, as all greenies do, that I knew all about poker. I learned differently in the following nights.

In 1870, the Queen’s Plate was the great event of the meeting. That was when Charlie Gates’ Jack Bell won. There was a big field, and Charlie’s horse was in it—one of the rank outsiders. Terror was a prime favorite. Charlie always liked the younger generation, and when I asked him what horse to bet on, he said any one but Jack Bell. Such is the perversity of youth that I immediately placed my money on Jack. The favorite led for the first mile, but in the next quarter was passed by Jack on the Green and another horse and Jack Bell closed upon the leaders, and coming down the home stretch forged ahead and won by nearly a length. Terror was fifth, and I was again a capitalist. All the winnings were usually made by such amateurs as myself, and it wasn’t because of our good judgment or experience, but just on luck. That was one of the memorable races of the early days, and is not forgotten to this day by a lot of old-timers.

In a vain but fairly honest endeavor to ascertain exactly what particular line of industry would be most suitable to ensure my future comfort and welfare, I embarked as an A. B. sailor before the mast. My father-in-law was the owner of a small fleet of schooners which plied on Lakes Ontario and Erie. My first voyage on the Pioneer was very successful. I didn’t get seasick, fall overboard, or start a mutiny, could furl or unfurl the mizzen mast sails, handle a tiller in a—well—in a way, and would gleefully have carolled a “Life on the Ocean Wave”, or warbled “Sailing”, which was so popular amongst the boys in ’85, if it had been composed then, and I couldn’t get the tune of the other one. A sailor’s life was a long drawn out sweet dream when we had far away breezes; at other times when the boisterous winds blew furiously, it was a nightmare. The Pioneer was sunk somewhere off Port Hope, but all hands were easily rescued. Then Capt. Allen and Mary, the cook, who was the captain’s wife and myself were transferred to the Marysburg, a larger schooner, which used to labor creakingly along as if there wasn’t any oil procurable to quiet her noisy timbers. One day in the early ’70’s we tried to make Cleveland harbor, when a hurricane came up, and we scampered across the lake and thought we had found shelter behind Long Point. Lake Erie is very shallow, and I can readily testify that we could see its very muddy bottom when the waves rolled sky-high. No fires could be lighted and we rationed on stale cold food for a while. Reaching the haven, the kitchen fire was started, and preparations made for a much needed square meal. But before that could be prepared, the anchor let go, the vessel lurched, I grabbed the cook-stove, and Mary doused the fire with a couple of pails of water. It was no snug harbor for the Marysburg which lurched furiously to starboard and very unlady-like started out for the open lake. Then there was a regular go-as-you-please. The Marysburg pitched and heaved. I only heaved. I would have given a million dollars if I could only have been put ashore in a swamp without any compass—but I didn’t happen to have anywhere near that sum about me. Sailors, who are proverbially high rollers in the spending line when ashore, seldom have that much money on board ship. But the Marysburg and I were high-rollers all the same just then, and took every watery hurdle. If it hadn’t been for the nauseating mal-de-mer, I honestly believe I would have thoroughly enjoyed the excitement. As it was I merely listlessly looked upon the wild scenes as an unconcerned spectator; I knew if I were drowned I never would be hanged. But the storm spent its fury, and once out of troubled waters, down came the main mast, and the big anchor got up all by itself and jumped overboard. I threw up my hat—about the last thing I did throw up. Then I learned something about the law of averages—a vessel has to sustain a certain amount of damages to obtain any insurance. When the vessel arrived at Port Colborne, the claim for damages went through like a shot.

When we were eating our first real meal in the cabin, the Captain quietly remarked that if I, who had recovered from my temporary disability, could handle the tiller or the sails in the same way I handled my knife and fork, I would soon be amongst the greatest mariners of the age, and would soon be a distinguished officer in Her Majesty’s navy. Shiver my timbers, how I might have won the war and fame and a tin-pot title and a pension!

That reminds me that when Port Dalhousie was reached I went to a barber shop for a shave. My face had been nicely lathered, when I noticed the barber making furious flourishes through the air with his razor. Naturally I asked him what he was doing, and he told me he was cutting their heads off. Then he gave another slash at the, to me, invisible objects with heads on, and still another and another. It dawned upon me that he was seeing things that can only be seen by a man with the D.T.’s. “Hold on,” I said, as I rubbed the lather off my face with a towel, “Let me help you”, and arising from the chair I said confidentially to him, “Say, old man, don’t you think we could do the job better if we had a little drink?” This appealed to him favorably and we started out for a nearby saloon, where he ordered brandy and soda and poured out a stiff ’un while I tried to drink a glass of lager, and skipped out and never stopped running until I laid down exhausted in the fo’castle of the Marysburg. That was the closest shave I ever had.

We generally have had pet animals in the family, and amongst them were a French-Canadian chestnut stallion, eleven and a quarter hands high, and Major, Fido, Bismarck and Toby, of the canine family, and old Tom of the feline tribe. Pascoe, the pony, was a beauty, and I guess he must have been a Protestant, for one Twelfth of July, when an Orange parade was passing with bands playing, he ran amongst a group of onlookers on the lawn in front of the house and seizing Miss Annie Carroll, a young lady visiting my mother, by the shoulders with his teeth, threw her down and tried to trample on her. Fortunately we interfered in time and prevented her from being hurt. Annie was the only Roman Catholic in the crowd—and, unless Pascoe had had strong religious convictions, it was difficult to understand why he should have deliberately picked on the only Roman in the party.

Fido was a little black and tan with a religious turn of mind, and he knew when Sunday came around. He accompanied the family to St. John’s Church, over a mile away, and always heralded our coming with loud sharp barks, which never ceased until all of us, including Fido, were seated in the pew. This got to be a nuisance, and Fido was confined in the barn the following Sunday morning. When we tried to find Fido the next Sunday morning, to tie him in the barn, his dogship could not be found—until we reached St. John’s, where he, with his infernal loud bark, was waiting at the church door, and joined us as usual in the morning devotions.

Bismarck was named after the ex-Chancellor of Germany, because he looked like him, and was a good watch-dog. I had been away from home for five years, and, returning one evening, was met at the gate by Biz, who growled at me. We stood facing each other for several minutes, Biz evidently determined that I should not go further, and I awaiting developments. Finally I called out, “Why, Biz”. While he had forgotten me, he instantly recognized my voice and jumped joyfully at me, wagged the stump of his short tail vigorously and gave every demonstration of joy. Poor Major, who had reached an advanced age, and for whom food was specially cooked by mother, went out one evening, ate some ground glass mixed with lard which some fiends had placed on the streets, came home and, lying with head on the doorstep, passed away with a wistful look in his great brown eyes, which brought tears to ours. Toby, who joined my family in recent years and is still with us, is a French fox terrier, and can do anything requiring intelligence except talk. Toby is very fond of my grandson George, whose especial pet she is. She had never seen a German helmet to our knowledge, but one day when George put one on she ferociously flew at him in a towering rage. He went out of the room and returned with a German forage cap on his head, and again the dog made a quick, vicious dash at him, and he had to hide the offending headgear before she could be quieted. There was intelligence for you, but not so much as she displayed when, as George wrote me at Atlanta: “Toby is getting along fine. She bit the Chinaman to-day, when he brought the laundry bill.”

I might as well candidly admit two things, and the admission is made with not too much vaunting pride. The first is that I once had great aspirations of being a poet, and while I had not the nerve to imagine I would reach the top-notcher class with Shakespeare, Byron, Tennyson, Bobby Burns, Campbell and other noted writers, I had fond hopes of at least having my effusions printed (at my own expense) in some magazine or other as a starter, until Fame would overtake me, and then—. But Fame couldn’t even catch up to me, let alone overtake me, although some of my effusions were highly spoken of by friends who had borrowed or wanted to borrow money from me. Here is one, which I did not dash off—just like that—but labored several years at it, and forget now whether it is finished or not. It was my intention to make it an epic; as I read it now, it looks most like an epicac. But here it is:

I wonder if in the early dawn,

When upon God’s great creating plan

He builded sky and sea and land

And moulded clay into living man,

Why used He earth in this grand work

Instead of carving hardened stone?

Was it because He knew that man

Could not—would not—live alone?

Then using the very softest dust

He made Man plastic—so his coming mate

Could always mould him as she wished,

Which she has done since Eve He did create.

That reminds me of Bill Smith coming into the Gazette office at Whitby one day a good many years ago, and telling me he was composing an elegy on his little dead brother, and wanted to know if I would print it for him. I told him we were a little short of space, but if it didn’t occupy more than three or four columns I would do my level best. In a couple of weeks, in marched William, and very grandiloquently laid his masterpiece before me. It wasn’t as long as he had been writing it. In fact it read:

“That little brave,

That little slave,

They laid him in the cold, cold grave.”

—William Smith.

One beautiful thing about it was that, like the speech of one of Joe Martin’s Cabinet ministers, out in British Columbia, it was of his own composure. The circulation of the Gazette increased largely that week, for William came in and absent-mindedly took away a couple of dozen copies to send to sympathizing friends and relatives.

The other admission is that false reports about a person are never true. For instance, sixteen years ago the Charlottetown, P.E.I., Guardian unblushingly reported my death, and while the reading of the obituary notice was not uninteresting, it was not altogether self-satisfying. It reads as follows:

“With sincere regret many thousands of people will learn of the death of George H. Ham of the Canadian Pacific Railway, Montreal. Very few men had so extensive an acquaintance or so many friends. He was full of good-will for everybody. During his illness letters and telegrams poured in from every quarter expressing most sincere desires for his recovery, but it had been otherwise ordered. He leaves a memory fragrant with the kindnesses that thousands have received at his hands.”

Of course, I didn’t demand a retraction, but when Mr. J. B. McCready, the editor, was seen during my visit to Charlottetown, a year or two later, he was willing to make one. Finally Mac and I agreed that it would not be advisable to spoil a good news item, just because it wasn’t altogether correct. So we let it go at that, although I have always maintained it wasn’t true.

But to this day, the paragraph, neatly framed in becoming black, lies before me on my office desk, and when anything goes wrong, and I feel down in the mouth, I pick it up and read it and say to myself: “Oh, well, things could easily be worse; this might have been true.” Which is some consolation.

After a brief newspaper experience in Guelph, Uxbridge, and as correspondent of the Toronto press, I started out in May, 1875, for some western point not then definitely determined on. Prince Arthur’s Landing offered no particular attraction for a rambling reporter in those days, so I headed for Winnipeg, and reached there—after experiencing the first steamboat collision in the Red River—with four dollars in pocket, ten of which I owed. Being a practical printer, I was offered a position on the Free Press, after besieging the office for a week. Then I rose to the dignity of city editor, and in less than four years published a paper of my own—the Tribune—which was afterwards amalgamated with the Times, of which I became managing editor. Then ill-health caused my retirement, and a beneficent Government made me registrar of deeds for the county of Selkirk. The introduction of the Torrens system, which required the registrar to be a barrister of ten years’ standing, knocked me out of the position, although I produced any number of witnesses that I had a longer standing than that at the bar (now abolished) and so I returned to newspaper work. After sixteen years of constant work in the bustling city, I was sent for by Mr. (Sir William) Van Horne, who kindly added my name to the pay-roll of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company.

Now, in 1921, having passed the allotted three score and ten of the Scriptures and the regulated three score and five of the C.P.R., I plug away at my desk or on the trains just as cheerfully and as hopefully as I did in my younger days—crossing the continent at least twice or more times every year and sometimes visiting nearly every state in the Union, with an occasional odd trip once in an age to the Old Country, Cuba, Mexico, Bahama Islands or Newfoundland. The rest of my time is spent at home.

Winnipeg a City of Live Wires—Three Outstanding

Figures—Rivalry Between Donald A. and Dr.

Schultz—Early Political Leaders—When Winnipeg

was Putting on its First Pants—Pioneer

Hotels—The Trials of a Reporter—Not Exactly

an Angelic City—The First Iron

Horse—Opening of the Pembina Branch—Profanity

by Proxy—The Republic

of Manitoba—The Plot to Secede.

Winnipeg is a live wire city. That does not have to be proven. Almost any one of its progressive business men will admit that, if cornered, but it is doubtful if in its couple of hundred thousand or so of people it holds as many distinguished “live wires” as did the muddy, generally disreputable village that in, say, 1873, with a thousand or perhaps fifteen hundred people, straggled along Main Street from Portage Avenue to Brown’s Bridge, near the present site of the City Hall, and sprawled between Main Street and the river. It was without sidewalk or pavements; it had neither waterworks, sewerage nor street lights. The nearest railroad was at Moorhead on the Red River, 222 miles away. Its connection with the outer world was one, or possibly two, steamers on the Red River in the summer, and by weekly stage in winter. It boasted telegraph connection with the United States and Eastern Canada by way of St. Paul, during the intervals when the line was working. Although essentially Canadian it was practically cut off from direct connection with Canada. The Dawson route to Port Arthur could be travelled with great labor, pains and cost; but did not admit of the transportation of supplies. All freight came by Northern Pacific Railway to Moorhead; then by steamer, flat boat or freight team to Winnipeg.

But the Winnipeg of that day was recognized to be then, as it is now, the gateway to the Canadian Prairie West where lay the hope of Canada’s future greatness. The transfer of governmental authority over Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada had taken place in 1869; Canadian authority had been established by the first Red River expedition of 1870; a transcontinental railway was to be built at an early date that would displace the primitive conditions then existing. The doors of vast opportunity lay wide open and Canada’s adventurous sons flocked to Winnipeg to have a part in the great expansion—the building of a newer and greater Canadian West. They were big men, come together with big purpose. Their ideas were big, and they fought for the realization of them. They struggled for place and power and advantage, not with regard to the little, isolated village which was the field of their activities and endeavors; but always with an eye to the city that now is and to the great plains as they now are.

They saw what was coming; they were there to bring it. Yet those who lived to see their visions realized, as they are to-day, are few and far between. The boom of 1881 seemed to promise that realization, while the pioneers of the early ’70’s were still to the fore. But the promise of the boom was not fulfilled—then. It was only a mirage, and when it passed it left the majority of the pioneers blown off the map financially and otherwise. And few ever “came back”. Since the boom of 1882, the soul of Winnipeg has never been what it was before. The later Winnipeg may be a better city. It was a short life from ’71 to ’82, but while it lasted, it was life with a “tang” to it—a “tang” born of conditions that cannot be repeated and therefore cannot be reproduced.

Who were those live wires of the ’70’s? I shall just mention a few whose reputations have been established before the world by after events. No one will deny the outstanding ability and commanding position in national, imperial and even world affairs, achieved by the late Lord Strathcona. In Winnipeg in those early ’70’s he was chief commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company, resident in Winnipeg, and took an active part in all that concerned the business or politics of the country.

“Jim” Hill flatboated down the Red River from Abercrombie and Moorhead to Winnipeg in ’70, ’71 and ’72. In ’73 he was the chief member of the firm of Hill, Griggs & Co., owning and operating the small steamer Selkirk on the Red River in opposition to the “Kittson Line” (really the H.B.C.) steamer International. Alex. Griggs was captain of the Selkirk, and Hill rustled business and was general manager. How small that day of small things was may be judged by the fact that these two stern wheel steamboats on the Red River transported all supplies of all kinds used in the trade of the vast Northwest; and at that the International was laid up in the fall for lack of business. Of course they had to meet the competition of flat boats. In any case Hill was squeezed out of the transportation business on the Red River. The Selkirk passed into the service of the “Kittson Line” and Hill entirely withdrew his interest in the development of the Canadian West. Some years afterwards he joined forces with his late opposition on the Red River in organizing and pushing what became the Great Northern railway system of to-day.

Amongst the men of the ’70’s, or indeed before the ’70’s, was James H. Ashdown, one of the many who entered in the business race, and one of the few who has realized to the full the success for which he hoped and planned. Mr. Ashdown was in Winnipeg before the transfer to Canada—no doubt in expectation of the event. As a Canadian he opposed the ambitions of Louis Riel and was imprisoned by Riel during his short reign. A careful but enterprising business man, the boom of 1882, that destroyed so many of his business colleagues and competitors, left him unshaken. His business has steadily expanded since that time. To-day Mr. Ashdown belongs to his business. In the ’70’s he was a fighting force for progress. In the struggle for competition and lower freight rates on the Red River he took a leading part, and was the means of establishing the “Merchants Line”, consisting of the Minnesota and the Manitoba. The Manitoba was sunk on her first trip by a collision with the “Kittson Line” International. While that seemed to put the “Merchants Line” out of business, the course of the subsequent damage litigation was such that a favorable arrangement towards Winnipeg merchants was made by the “Kittson Line”; and this bridged over the river freight conditions until the arrival of the railways. In later days when financial difficulties seemed likely to overcome the big city, Mr. Ashdown became mayor and admittedly put the city on its feet. No one to-day will deny Mr. Ashdown the attribute of being a live wire.

Another old-timer of the early ’70’s to establish his title to rank with the best of them under modern conditions was “Sandy” Macdonald. Mr. Macdonald was a resident of Winnipeg in the ’70’s but did not go into business for himself until after the boom. However, he soon made up for lost time. During the slow moving decades that followed the boom, Mr. Macdonald expanded his wholesale grocery business until it spread all over the west from Winnipeg to the Coast. Some years ago he sold out to a then recently organized company for several millions. But his activities did not cease. With a new organization he is doing as much and as widespread a business as ever, following his own original lines as to cash sales and co-operative employment. Mr. Macdonald is essentially a progressive along all lines and has served the modern city both as alderman and mayor.

THE NEW AND THE OLD C.P.R. STATIONS IN WINNIPEG.

But a city must have other interests than commerce and transportation if it is to be a real city. Education is of paramount importance. Now that there is a Manitoba University and a number of colleges given to higher education along all accepted modern lines, representing an expenditure of millions, it is in order to recall that the first Manitoba college was established through the single-minded purpose and almost single-handed efforts of Rev. Dr. Bryce, of the Presbyterian Church, who still occupies a high place amongst the educationists of the West. Manitoba College was begun, like almost all else in those early ’70’s, on faith in the future and a determination to be ready for it when it came. The chief trade of the city was in buffalo robes from the plains; production from the farms, limited as it was at best, had been paralyzed for several successive seasons by the grasshopper plague. The immigrants, who were arriving, needed almost everything more than they did education. And yet Dr. Bryce, having the future in mind, worked on. It is a long road from the Manitoba College of 1873 to the University and College of 1921. But Dr. Bryce has been pushing the cause through every change and has the satisfaction of seeing to-day the realization of the hopes with which he entered on the work.

Lord Strathcona and “Jim” Hill have passed from the scene of their efforts and triumphs. Messrs. Ashdown and Macdonald and Rev. Dr. Bryce are still here to answer for themselves. It is not to be supposed that these names exhaust the list of outstanding figures who held the stage in those early years. They are merely mentioned as examples that prove beyond argument the live wire character of the early population.

An instance of the rivalry of those early giants was that between Donald A. Smith and Dr. Schultz. Mr. Smith was commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company, by far the most powerful commercial organization in the west, which also controlled the only inlet and outlet of trade or travel by its “Kittson Line” of steamers on the Red River. He was active in civic, provincial and federal politics and was considered by the new Canadian influx to be anti-Canadian and non-progressive. Dr. Schultz was a Canadian physician from Windsor, Ontario, who had come to the Red River settlement and established himself in medical practice before the transfer of 1869. He had championed the Canadian cause both before and during the Riel rebellion, and escaped Riel’s vengeance by leaving the country in the middle of winter; but his property was confiscated by the rebels. When he returned in the wake of the first expedition he was of course in strong favor with the constantly increasing Canadian element of the population. At the same time in his practice as a physician he acquired the confidence of many of the native Red River settlers, so that he was in a strong position to contest the claims of Mr. Smith’s political support. He had some aptitude for trade as well as for medicine, politics and real estate, and there is no doubt that his vision of the future was as far reaching and on much the same lines as that of Mr. Smith, who was the first representative from Manitoba in the Canadian Parliament.

Both were men of boundless energy and ambition. They were in opposition to each other on all points and at all times. While Dr. Schultz helped to ultimately defeat Mr. Smith for parliament, the latter finally carried away the prize of railway construction and control that had been the great dream of Dr. Schultz. Although the doctor was finally distanced in the race by his great rival he nevertheless achieved a large measure of distinction. He sat in the Commons and afterwards in the Senate. He was made a knight and for years was lieutenant-governor of Manitoba. Had his health not broken down, his death following, there is no saying how far he might ultimately have gone. These facts are mentioned not to revive ancient animosities but to prove that the men who achieved success did not do so because they had the field to themselves. They had to fight every inch of the way; then as much as now or possibly then more than now.

Generally speaking, the politicians of Manitoba in the ’70’s were of higher calibre than is generally found in new countries. Head and shoulders above all was Hon. John Norquay, a native, who became Premier after the retirement of Hon. A. R. Davis, a very shrewd politician. Mr. Norquay, who personally resembled Sir James Carroll, the Maori-Irishman or Irish-Maorian of New Zealand, was a high minded statesman, eloquent beyond ordinary and his honesty and motives were never questioned, except by the cheap agitating politicians. His sudden death was a loss to Canada, for had he lived he would have left his mark at Ottawa. Hon. Thomas Greenway was his sturdy opponent and they were great bosom friends. There were others like John Winram, William and Robert Bathgate, the former starting the first gas company in the city, Col. McMillan, H. M. Howell, Tom Scott, W. F. McCreary, A. W. Ross, Hugh Sutherland, Gilbert McMicken, Stewart Mulvey, Kenneth Mackenzie, Hon. Joseph Royal, C. P. Brown, D. M. Walker, Tom Daly, Hon. A. A. C. Lariviere, D. B. Woodworth, Isaac Campbell, W. F. Luxton, Joseph Ryan, Dr. O’Donnell, E. P. Leacock, Charlie Mickle, Fred Wade, John Macbeth, Alex. M. Sutherland, E. H. G. Hay, with whom at later date were associated Hon. Joseph Martin, Clifford Sifton, Dr. Harrison, Dr. Wilson, Sir R. P. Roblin, Sir James Aiken, Somerset Aiken, L. M. Jones, J. D. Cameron, Joshua Callaway and Charlie Sharpe, Amos Rowe, Tom Kelly, the big contractor, Hugh John Macdonald, T. W. Taylor, W. B. Scarth, Hon. Robt. Rogers, J. H. D. Munson, Geo. Wallace, now M.P.; Sir Stewart and Willie Tupper, J. P. Curran and Tommy Metcalfe, who now ornament the bench; Heber Archibald was also a prominent figure, and many others, all of whom played their part in the development of the country.

When I struck Winnipeg, the embryo city was just putting on its first pants. The route from eastern Canada was made in summer by the Great Lakes to Duluth or by rail through Minnesota to Fargo or Moorhead—just across the river from each other—the one being in Minnesota and the other in Dakota; and then by boat to the future western metropolis. I went up the Great Lakes to Thunder Bay, walked across the ice and rowed up the Kaministiquia River to Fort William on May 24th, 1875. Then I drove over to Port Arthur, where at Julius Sommer’s tavern, I sat down to a table covered with a checkered red and white table cloth for the first time in my life. The food was good enough—what there was of it—and plenty of it such as it was. After a short stay, I took the steamer for Duluth and the Northern Pacific to Moorhead. My seat-mate on the train from Duluth to Moorhead was Billy Bell—now Col. William G. Bell, a prominent citizen of Winnipeg. There were no sleeping cars then. At Aitken, Minnesota, a lumbering centre, one of those wild-eyed lumber-jacks with his red shirt sleeves rolled up and his trousers stuck in his top boots, leaped on the car, and, furiously brandishing a revolver, swaggered down the aisle.

“Who am I?” was his constant cry to the half-scared occupants of the coach. “Say, who am I? blankety, blankety, blank my blankety blank eyes, who am I?”

As he approached our seat, his voice became if possible a little louder and the revolver was flourished a little more frantically. It peeved me. So I grabbed Billy by the arm, and looking the disturber in the eye, sharply remarked:

“Billy, tell the gentleman who he is!”

That’s all there is to the story, for the bully subsided and vamoosed by the rear door amidst the sighs of relief and hearty laughter of the passengers.

The boat trip from Moorhead to Winnipeg occupied a couple of days and nights. There was keen competition between the old Kittson Line and the Merchants Line. I was a passenger on the International, which left first for the north. The Manitoba passed us some distance down the river, reached Winnipeg, and on its return south-bound trip was at Lemay’s Point, about five miles from Winnipeg, during the night. In rounding the bend, the International, doubtless not unintentionally, made a straight run for her, struck her under the guards, and she partially sank. I was unceremoniously thrown out of my berth, and rushed to the cabin, which was the scene of wild confusion and uproar. One scared fellow-passenger loudly shouted that the boat was sinking, and just then the mate came along, and, hitting him a wallop on the ear, which knocked him down, said: “You’re a dom liar. It’s the other boat that’s sinking.”

Winnipeg warmly welcomed the new-comer, and made him feel at home. The old Davis House on Main Street had been the only hotel in town, but, as population increased, Ed. Roberts’ Grand Central and the International were its rivals, and afterwards the Queen’s—the palace hotel of the Northwest, as it was ostentatiously advertised—was built, and with it the Merchants.

Later came the Revere, Leland, Winnipeg, Golden, Grand Union, Imperial, Johnny Haverty’s C. P. R. Hotel at the south end of the city, Duncan Sinclair’s Exchange, Scotty Mclntyre’s, Taff’s, Pat O’Connor’s St. Nicholas, George Velie’s Gault House, Denny Lennon’s, Billy O’Connor’s, John Baird’s, Johnny Gurns’, Bob Arthur’s, the Potter House, the Brouse House, Montgomery Brothers’ Winnipeg, John Poyntz’, the Clarendon and many more to fill in the immediate wants, until the Manitoba, an offspring of the Northern Pacific was erected, only to be shortly after destroyed by fire. Now the city has the Royal Alexandra and Fort Garry, which rank amongst the finest hotels on the continent, and a host of smaller but very comfortable places. Winnipeg during and ever since the boom has never lacked splendid restaurants. Clougher’s, Bob Cronn’s, Jim Naismith’s and the Woodbine were the leading ones, but that old veteran, Donald McCaskill, had a mania for opening and closing eating places with astounding regularity. Chad’s place at Silver Heights was a pleasant and well-run resort, but one can’t play ball all winter and so other games were played in some of which what are called chips were substituted to the satisfaction of all concerned, except perhaps the losers.

All of this reminds me that one of the north-end hotels was called the California, and its proprietor was Old Man Wheeler. When in the late ’70’s it was determined to form a Conservative Association, the California was chosen as the place for the gathering of the faithful in that locality. Hon. D. M. Walker, afterwards appointed to a judgeship, and myself were in charge of the meeting. We arrived early to see that all necessary arrangements had been completed. Sitting in an upper room the Judge asked me if I knew what Wheeler’s politics were and I said I didn’t, but would ascertain. So I stamped on the floor, which was the usual signal that someone was wanted. Old Man Wheeler quickly appeared on the scene, and the Judge asked:

“Wheeler, what are your politics?”

“Oh, I don’t mind,” he replied, “I’ll take a little Scotch.”

The meeting was a huge success, after such an auspicious opening. The Judge said it could not help but be.

While Winnipeg in the ’70’s was in a sort of Happy Valley, with times fairly good and pretty nearly everybody knowing everybody else or knowing about them, the reporter’s position was not, at all times, a very pleasant one, for on wintry days, when the mercury fell to forty degrees below zero, and the telegraph wires were down, and there were no mails and nothing startling doing locally, it was difficult to fill the Free Press, then a comparatively small paper, with interesting live matter. A half-dozen or so drunks at the police court only furnished a few lines, nobody would commit murder or suicide, or even elope to accommodate the press, and the city council only met once a week; but we contrived to issue a sheet every day that was not altogether uninteresting. Of course, when anything of consequence did happen, the most was made of it. A. W. Burrows (Dad) was a great source of news, and many an item he gave me. He was in the real estate business, and a hustler but lived long before his time in Winnipeg.

The city council was an attraction to many citizens and spirited encounters were frequent and popular with the assembled crowd. At one meeting Ald. Frank Cornish called Ald. Alloway a puppy, and, when asked by the mayor to apologize, did so by saying that when he came to think of it, his brother alderman was not a puppy, but a full-grown dog. This did not meet with the approval of his worship, whereupon Ald. Cornish very humbly and penitently apologized to the entire canine race. Ald. Wright and Ald. Banning had a regular set-to at another meeting, in which both got the worst of it. “Them was the days.” It was said of Mr. Cornish that when he was mayor of Winnipeg—he was the first—he hauled himself up before himself on a charge of being, well, let’s say not too sober, and fined himself $5.00 and costs. The attendants at the police court loudly applauded this Spartan act, until they heard the mayor say to himself:

“Cornish, is this your first offence?” and culprit Cornish blandly informed Mayor Cornish that it was. Then his worship addressing himself to himself, said:

“Well, if it’s your first offence, Cornish, I’ll remit your fine.” And the laughter was resumed.

It would be a mistake to imagine, that the Winnipeg of the early ’70’s was a city of angels. It is a regrettable fact that some, if not many, of its leading citizens may fairly be described as otherwise.

A difficulty in dealing with the more human and therefore more interesting features of the progress of any community is that the events of a half century ago cannot be fairly read in the light of to-day. Custom is law in a large measure. What was allowable or even commendable under the custom prevailing in one age may be neither allowable nor commendable under the custom of half-a-century later. The reading public do not make allowances. They are apt to judge the facts related of the past by the standards of the present; they do not recognize the absolute truth of the phrase, “Other times, other manners.”

Therefore many legitimately interesting episodes of the old days must go unrecorded rather than that the men of enterprise, energy, foresight and patriotism who put Winnipeg on the map in the years from ’71 to ’82 should be misunderstood.

The men who, so to speak, put the “Win” in Winnipeg deserve the best that those who are the heirs of their efforts and successes, or even failures, can say or think of them. The occasion was great, and they were men of the occasion.

The arrival of the first locomotive in Winnipeg was a red-letter day for the whole Canadian West. It was on October 9, 1877. Brought down the Red River on a barge, with six flat cars and a caboose, towed by the old Kittson Line stern-wheeler, Selkirk, her voyage down stream was one continuous triumphal progress from Pembina at the International boundary to Winnipeg.

The Free Press of that day, on whose staff I was city editor, telegraph editor, news editor, reporter, proof reader and exchange editor, gave the following account from its Pembina correspondent of the eventful affair:

“The steamer Selkirk arrived at Pembina yesterday (Sunday), with three barges, having on board a locomotive and tender, a caboose and six platform cars, in charge of Mr. Joseph Whitehead, contractor on the C.P.R. As this is the pioneer locomotive making its way down the Red River Valley, the steamer was hailed by the settlers with the wildest excitement and greatest enthusiasm, especially as Mr. Whitehead had steam up on his engine, and notified the inhabitants that the iron horse was coming by the most frantic shrieks and snortings. On passing Fort Pembina the flotilla was saluted by the guns of the (U.S.) artillery, and upon arrival at Pembina it was met by Captain McNaught, commanding at Fort Pembina, and his officers, Hon. J. Frankenfield, N. E. Nelson, and his associates in the U. S. customs, and the population en masse. The flotilla was handsomely decorated with flags and bunting, proud of the high distinction of carrying the first locomotive destined to create a new era for travel and traffic in the great northwest.”

The Free Press said in part on October 9th:

“At an early hour this morning, wild, unearthly shrieks from the river announced the coming of the steamer Selkirk, with the first locomotive ever brought into Manitoba; and about 9 o’clock the boat steamed past the Assiniboine. A large crowd of people collected upon the river banks, and, as the steamer swept past the city, mill whistles blew furiously, and bells rang out to welcome the iron horse. By this time the concourse had assembled at No. 6 warehouse (at foot of Lombard street) where the boat landed, and in the crowd were to be noticed people of many different nationalities represented in the prairie provinces.

“The Selkirk was handsomely decorated for the occasion with Union Jacks, Stars and Stripes, banners with the familiar ‘C.P.R.’ and her own bunting; and with the barge conveying the locomotive and cars ahead of her, also gaily decorated with flags and evergreens and a barge laden with railway ties on each side presented a novel spectacle. The whistles of the locomotive and the boat continued shrieking, the mill whistles joined in the chorus, the bells clanged—a young lady, Miss Racine, pulling manfully at the ropes—and the continuous noise and din proclaimed loudly that the iron horse had arrived at last. Shortly after landing three cheers were given for Mr. Joseph Whitehead, and in a few minutes a crowd swarmed on board and examined the engine most minutely. The caboose and flat cars, which also came in for their share of attention, each bearing the name ‘Canadian Pacific’ in white letters. After remaining a couple of hours, during which she was visited by many hundreds, the Selkirk steamed to a point below Point Douglas ferry, where a track had been laid to the water’s edge, on which it was intended to run the engine this afternoon.

“It is a somewhat singular coincidence as mentioned by Mr. Rowan (C.P.R. engineer in charge then) on a recent public occasion, that Mr. Whitehead, who now introduces the first locomotive into this young country, should have operated as fireman to the engine which drew the first train that ran on the very first railway in England—the historic line built in Yorkshire between Stockton-on-Tees and Darlington. Surely the event of to-day is not one whit less important to Canadians in Manitoba than was that in which Mr. Whitehead figured so many years ago to Englishmen, in Yorkshire. It is no wonder that the settlers on the banks of the Red River went almost wild with excitement in witnessing the arrival of the ‘iron-horse.’ ”