* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Cabinet Portrait Gallery of British Worthies Vol 11 of 12

Date of first publication: 1846

Author: C. Cox

Date first posted: April 25, 2014

Date last updated: April 25, 2014

Faded Page eBook #20140448

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Donna M. Ritchey & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

[Pg 5]William Penn was born in London, October 14, 1644. He was the son of a naval officer of the same name, who served with distinction both in the Protectorate and after the Restoration, and who was much esteemed by Charles II. and the Duke of York. At the age of fifteen, he was entered as a gentleman-commoner at Christchurch, Oxford. He had not been long in residence, when he received, from the preaching of Thomas Loe, his first bias towards the doctrines of the Quakers; and in conjunction with some fellow-students he began to withdraw from attendance on the Established[Pg 6] Church, and to hold private prayer meetings. For this conduct Penn and his friends were fined by the college for nonconformity; and the former was soon involved in more serious censure by his ill-governed zeal, in consequence of an order from the king, that the ancient custom of wearing surplices should be revived. This seemed to Penn an infringement of the simplicity of Christian worship: whereupon he with some friends tore the surplices from the backs of those students who appeared in them. For this act of violence, totally inconsistent, it is to be observed, with the principles of toleration which regulated his conduct in after-life, he and they were very justly expelled.

Admiral Penn, who like most sailors possessed a quick temper and high notions of discipline and obedience, was little pleased with this event, and still less satisfied with his son's grave demeanour, and avoidance of the manners and ceremonies of polite life. Arguments failing, he had recourse to blows, and as a last resource, he turned his son out of doors; but soon relented so far as to equip him, in 1662, for a journey to France, in hope that the gaiety of that country would expel his new-fashioned and, as he regarded them, fanatical notions. Paris, however, soon became wearisome to William Penn, and he spent a considerable time at Saumur, for the sake of the instruction and company of Moses Amyrault, an eminent Protestant divine. Here he confirmed and improved his religious impressions, and at the same time acquired, from the insensible influence of those who surrounded him, an increased polish and courtliness of demeanour, which greatly gratified the admiral on his return home in 1664.

Admiral Penn went to sea in 1664, and remained two years on service. During this time the external effects of his son's residence in France had worn away, and he had returned to those grave habits, and that rule of associating only with religious people, which had before given his father so much displeasure. To try the effect of absence and change of associates, Admiral Penn sent William to manage his estates in Ireland, a duty which the latter performed with satisfaction both to himself[Pg 7] and his employer. But it chanced that, on a visit to Cork, he again attended the preaching of Thomas Loe, by whose exhortations he was deeply impressed. From this time he began to frequent the Quakers' meetings; and in September, 1667, he was imprisoned, with others, under the persecuting laws which then disgraced our statute-book. Upon application to the higher authorities he was soon released.

Upon receiving tidings that William had connected himself with the Quakers, the admiral immediately summoned him to England; and he soon became certified of the fact, among other peculiarities, by his son's pertinacious adherence to the Quakers' notions concerning what they called Hat Worship. This led him to a violent remonstrance. William Penn behaved with due respect; but in the main point, that of forsaking his associates and rule of conduct, he yielded nothing. The father confined his demands at last to the simple point, that his son should sit uncovered in the presence of himself, the king, and the Duke of York. Still William Penn felt bound to make not even this concession; and on this refusal the admiral again turned him out of doors.

Soon after, in 1668, he began to preach, and in the same year he published his first work, 'Truth Exalted,' &c. We cannot here notice his very numerous works, of which the titles run, for the most part, to an extraordinary length: but 'The Sandy Foundation Shaken,' published in the same year, claims notice, as having led to his first public persecution. In it he was induced, not to deny the doctrine of the Trinity, which in a certain sense he admitted, but to object to the language in which it is expounded by the English Church; and for this offence he was imprisoned for some time in the Tower. During this confinement, he composed 'No Cross, No Crown,' one of his principal and most popular works, of which the leading doctrine, admirably exemplified in his own life, was, that the way to future happiness and glory lies, in this world, not through a course of misery and needless mortification, but still through[Pg 8] labour, watchfulness, and self-denial, and continual striving against corrupt passions and inordinate indulgence. This is enforced by copious examples from profane as well as sacred history; and the work gives evidence of an extent of learning very creditable to its author, considering his youth, and the circumstances under which it was composed. He was detained in prison for seven months, and treated with much severity. In 1669 he had the satisfaction of being reconciled to his father.

William Penn was one of the first sufferers by the passing of the Conventicle Act, in 1670. He was imprisoned in Newgate, and tried for preaching to a seditious and riotous assembly in Gracechurch Street; and this trial is remarkable and celebrated in our criminal jurisprudence, for the firmness with which he defended himself, and still more for the admirable courage and constancy with which the jury maintained the verdict of acquittal which they pronounced. He showed on this, and on all other occasions, that he well understood and appreciated the free principles of our constitution, and that he was resolved not to surrender one iota of that liberty of conscience which he claimed for others, as well as for himself. "I am far from thinking it fit," he said, in addressing the House of Commons, "because I exclaim against the injustice of whipping Quakers for Papists, that Papists should be whipped for their consciences. No, for though the hand pretended to be lifted up against them hath lighted heavily upon us, and we complain, yet we do not mean that any should take a fresh aim at them, or that they should come in our room, for we must give the liberty we ask, and would have none suffer for a truly sober and conscientious dissent on any hand." His views of religious toleration and civil liberty he has well and clearly explained in the treatise entitled 'England's present Interest,' &c. published in 1674, in which it formed part of his argument that the liberties of Englishmen were anterior to the settlement of the English church, and could not be affected by discrepancies in their religious belief. He maintained that to live honestly, to do no injury to[Pg 9] another, and to give every man his due, was enough to entitle every native to English privileges. It was this, and not his religion, which gave him the great claim to the protection of the government under which he lived. Near three hundred years before Austin set his foot on English ground the inhabitants had a good constitution. This came not in with him. Neither did it come in with Luther; nor was it to go out with Calvin. We were a free people by the creation of God, by the redemption of Christ, and by the careful provision of our never-to-be-forgotten, honourable ancestors: so that our claim to these English privileges, rising higher than Protestantism, could never justly be invalidated on account of nonconformity to any tenet or fashion it might prescribe.

In the same year died Sir William Penn, in perfect harmony with his son, towards whom he now felt the most cordial regard and esteem, and to whom he bequeathed an estate computed at 1500l. a-year, a large sum in that age. Towards the end of the year he was again imprisoned in Newgate for six months, the statutable penalty for refusing to take the oath of allegiance which was maliciously tendered to him by a magistrate. This appears to have been the last absolute persecution for religion's sake which he endured. Religion in England has generally met with more toleration in proportion as it has been backed by the worldly importance of its professors: and though his poor brethren continued to suffer imprisonment in the stocks, fines, and whipping, as the penalty of their peaceable meetings for Divine worship, the wealthy proprietor, though he travelled largely, both in England and abroad, and laboured both in writing and in preaching, as the missionary of his sect, both escaped injury and acquired reputation and esteem by his self-devotion. To the favour of the king and the Duke of York he had a hereditary claim, which appears always to have been cheerfully acknowledged; and an instance of the rising consideration in which he was held appears in his being admitted to plead, before a Committee of the House of Commons, the request of[Pg 10] the Quakers that their solemn affirmation should be admitted in the place of an oath. An enactment to this effect passed the Commons in 1678, but was lost, in consequence of a prorogation, before it had passed the Lords. It was on this occasion that he made that appeal in behalf of general toleration, of which a part is quoted in the preceding page.

Penn married in 1672, and took up his abode at Rickmansworth, in Hertfordshire. In 1677 we find him removed to Worminghurst, in Sussex, which long continued to be his place of residence. His first engagement in the plantation of America was in 1676: in consequence of being chosen arbitrator in a dispute between two Quakers, who had become jointly concerned in the colony of New Jersey. Though nowise concerned, by interest or proprietorship (until 1681, when he purchased a share in the eastern district in New Jersey), he took great pains in this business; he arranged terms, upon which colonists were invited to settle; and he drew up the outline of a simple constitution, reserving to them the right of making all laws by their representatives, of security from imprisonment or fine except by the consent of twelve men of the neighbourhood, and perfect freedom in the exercise of their religion: "regulations," he said, "by an adherence to which they could never be brought into bondage but by their own consent." In these transactions he had the opportunity of contemplating the glorious results which might be hoped from a colony founded with no interested views, but on the principles of universal peace, toleration, and liberty: and he felt an earnest desire to be the instrument in so great a work, more especially as it held out a prospect of deliverance to his persecuted Quaker brethren in England, by giving them a free and happy asylum in a foreign land. Circumstances favoured his wish. The Crown was indebted to him 16,000l. for money advanced by the late Admiral for the naval service. It was not unusual to grant not only the property, but the right of government, in large districts in the uncleared part of America, as in the case of New York and New Jersey[Pg 11] respectively to the Duke of York and Lord Baltimore: and though it was hopeless to extract money from Charles, yet he was ready enough, in acquittal of this debt, to bestow on Penn, whom he loved, a tract of land from which he himself could never expect any pecuniary return. Accordingly, Penn received, in 1681, a grant by charter of that extensive province named Pennsylvania by Charles himself, in honour of the Admiral: by which charter he was invested with the property in the soil, with the power of ruling and governing the same; of enacting laws, with the advice and approbation of the freemen of the territory assembled for the raising of money for public uses; of appointing judges and administering justice. He immediately drew up and published 'Some Account of Pennsylvania,' &c.; and then 'Certain Conditions or Concessions,' &c. to be agreed on between himself and those who wished to purchase land in the province. These having been accepted by many persons, he proceeded to frame the rough sketch of a constitution, on which he proposed to base the charter of the province. The price fixed on land was forty shillings, with the annual quit-rent of one shilling, for one hundred acres: and it was provided that no one should, in word or deed, affront or wrong any Indian without incurring the same penalty as if the offence had been committed against a fellow planter; that strict precautions should be taken against fraud in the quality of goods sold to them; and that all differences between the two nations should be adjudged by twelve men, six of each. And he declares his intention "to leave myself and my successors no power of doing mischief; that the will of one man may not hinder the good of a whole country."

This constitution, as originally organised by Penn, consisted, says Mr. Clarkson, "of a Governor, a Council, and an Assembly; the two last of which were to be chosen by, and therefore to be the Representatives of, the people. The Governor was to be perpetual President, but he was to have but a treble vote. It was the office of the Council to prepare and propose bills; to see that[Pg 12] the laws were executed; to take care of the peace and safety of the province; to settle the situation of ports, cities, market-towns, roads, and other public places; to inspect the public treasury; to erect courts of justice; to institute schools for the virtuous education of youth; and to reward the authors of useful discovery. Not less than two-thirds of these were necessary to make a quorum, and the consent of not less than two-thirds of such quorum in all matters of moment. The Assembly were to have no deliberative power, but when bills were brought to them from the Governor and Council, were to pass or reject them by a plain Yes or No. They were to present Sheriffs and Justices of the Peace to the Governor; a double number, for his choice of half. They were to be chosen annually, and to be chosen by secret ballot." This groundwork was modified by Penn himself at later periods, and especially by removing that restriction which forbade the Assembly to debate, or to originate bills: and it was this, substantially, which Burke, in his 'Account of the European settlements in America,' describes as "that noble charter of privileges, by which he made them as free as any people in the world, and which has since drawn such vast numbers of so many different persuasions and such various countries to put themselves under the protection of his laws. He made the most perfect freedom, both religious and civil, the basis of his establishment; and this has done more towards the settling of the province, and towards the settling of it in a strong and permanent manner, than the wisest regulations could have done on any other plan."

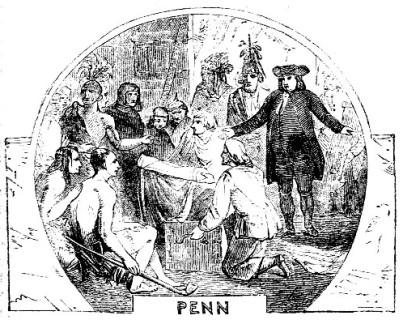

In 1682 a number of settlers, principally Quakers, having been already sent out, Penn himself embarked for Pennsylvania, leaving his wife and children in England. On occasion of this parting, he addressed to them a long and affectionate letter, which presents a very beautiful picture of his domestic character, and affords a curious insight into the minute regularity of his daily habits. He landed on the banks of the Delaware in October, and forthwith summoned an assembly of the freemen of the province, by whom the frame of government, as it had[Pg 13] been promulgated in England, was accepted. Penn's principles did not suffer him to consider his title to the land as valid, without the consent of the natural owners of the soil. He had instructed persons to negotiate a treaty of sale with the Indian nations before his own departure from England; and one of his first acts was to hold that memorable Assembly, to which the history of the world offers none alike, at which this bargain was ratified, and a strict league of amity established. We do not find specified the exact date of this meeting, which took place under an enormous elm-tree, near the site of Philadelphia, and of which a few particulars only have been preserved by the uncertain record of tradition. Well and faithfully was that treaty of friendship kept by the wild denizens of the woods: "a friendship," says Proud, the historian of Pennsylvania, "which for the space of more than seventy years was never interrupted, or so long as the Quakers retained power in the government."

Penn remained in America until the middle of 1684. During this time much was done towards bringing the colony into prosperity and order. Twenty townships were established, containing upwards of 7000 Europeans; magistrates were appointed; representatives, as prescribed by the constitution, were chosen, and the necessary public business transacted. In 1683 Penn undertook a journey of discovery into the interior; and he has given an interesting account of the country in its wild state, in a letter written home to the Society of Free Traders to Pennsylvania. He held frequent conferences with the Indians, and contracted treaties of friendship with nineteen distinct tribes. His reasons for returning to England appear to have been twofold; partly the desire to settle a dispute between himself and Lord Baltimore, concerning the boundary of their provinces, but chiefly the hope of being able, by his personal influence, to lighten the sufferings and ameliorate the treatment of the Quakers in England. He reached England in October, 1684. Charles II. died in February, 1685. But this was rather favourable to Penn's credit at court; for, besides[Pg 14] that James appears to have felt a sincere regard for him, he required for his own church that toleration which Penn wished to see extended to all alike. This credit at court led to the renewal of an old and assuredly most groundless report, that Penn was at heart a Papist—nay, that he was in priest's orders, and a Jesuit: a report which gave him much uneasiness, and which he took much pains in public and in private to contradict. The same credit, and the natural and laudable affection and gratitude towards the Stuart family which he never dissembled, caused much trouble to him after the Revolution. He was continually suspected of plotting to restore the exiled dynasty; was four times arrested, and as often discharged in the total absence of all evidence against him. During the years 1691, 1692, and part of 1693, he remained in London, living, to avoid offence, in great seclusion: in the latter year he was heard in his own defence before the king and council, and informed that he need apprehend no molestation or injury.

The affairs of Pennsylvania fell into some confusion during Penn's long absence. Even in the peaceable sect of Quakers there were ambitious, bustling, and selfish men; and Penn was not satisfied with the conduct either of the Representative Assembly, or of those to whom he had delegated his own powers. He changed the latter two or three times, without effecting the restoration of harmony: and these troubles gave a pretext for depriving him of his powers as governor, in 1693. The real cause was probably the suspicion entertained of his treasonable correspondence with James II. But he was reinstated in August, 1694, by a royal order, in which it was complimentarily expressed that the disorders complained of were produced entirely by his absence. Anxious as he was to return, he did not find an opportunity till 1699: the interval was chiefly employed in religious travel through England and Ireland, and in the labour of controversial writing, from which he seldom had a long respite. His course as a philanthropist on his return to America is honourably marked by an endeavour to ameliorate the condition of Negro slaves. The society of[Pg 15] Quakers in Pennsylvania had already come to a resolution, that the buying, selling, and holding men in slavery was inconsistent with the tenets of the Christian religion: and following up this honourable declaration, Penn had no difficulty in obtaining for them free admission into the regular meetings for religious worship, and in procuring that other meetings should be holden for their particular benefit. The Quakers therefore merit our respect as the earliest, as well as some of the most zealous emancipators. Mr. Clarkson says, "When Penn procured the insertion of this resolution in the Monthly Meeting book of Philadelphia, he sealed as assuredly and effectually the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and the Emancipation of the Negroes within his own province, as when he procured the insertion of the minute relating to the Indians in the same book he sealed the civilization of the latter; for, from the time the subject became incorporated into the discipline of the Quakers, they never lost sight of it. Several of them began to refuse to purchase Negroes at all; and others to emancipate those which they had in their possession, and this of their own accord, and purely from the motives of religion; till at length it became a law of the society that no member could be concerned, directly or indirectly, either in buying and selling, or in holding them in bondage; and this law was carried so completely into effect, that in the year 1780, dispersed as the society was over a vast tract of country, there was not a single Negro as a slave in the possession of an acknowledged Quaker. This example, soon after it had begun, was followed by others of other religious denominations."

In labouring to secure kind treatment, to raise the character, and to promote the welfare of the Indians, Penn was active and constant, during this visit to America as before. The legislative measures which took place while he remained, and the bickerings between the Assembly and himself, we pass over, as belonging rather to a history of Pennsylvania than to the biography of its founder. For the same reason we omit the charges preferred against him by Dr. Franklin. The union in one[Pg 16] person of the rights belonging both to a governor and a proprietor, no doubt is open to objection; but this cannot be urged as a fault upon Penn; and we believe that it would be difficult to name any person who has used power and privilege with more disinterested views. That he was indifferent to his powers, or his emoluments, is not to be supposed, and ought not to have been expected. He spent large sums, he bestowed much pains upon the colony: and he felt and stated it to be a great grievance, that, whereas a provision was voted to the royal governor during the period of his own suspension, not so much as a table was kept for himself; and that, instead of contributing towards his expenses, even the trivial quit-rents which he had reserved remained unpaid: nay, it was sought by the Assembly, against all justice, to divert them from him, towards the support of the government. It is to be recollected that Franklin wrote for a political object, to overthrow the privileges which Penn's heirs enjoyed.

The Governor returned to England in 1701, to oppose a scheme agitated in Parliament for abolishing the proprietary governments, and placing the colonies immediately under royal control: the bill, however, was dropped before he arrived. He enjoyed Anne's favour, as he had that of her father and uncle, and resided much in the neighbourhood of the court, at Kensington and Knightsbridge. In his religious labours he continued constant, as heretofore. He was much harassed by a law-suit, the result of too much confidence in a dishonest steward: which being decided against him, he was obliged for a time to reside within the Rules of the Fleet Prison. This, and the expenses in which he had been involved by Pennsylvania, reduced him to distress, and in 1709 he mortgaged the province for 6,600l. In 1712 he agreed to sell his rights to the government for 12,000l., but was rendered unable to complete the transaction by three apoplectic fits, which followed each other in quick succession. He survived however in a tranquil and happy state, though with his bodily and mental vigour much broken, until July 30th, 1718, on[Pg 17] which day he died at his seat at Rushcomb, in Berkshire, where he had resided for some years.

His first wife died in 1693. He married a second time in 1696; and left a family of children by both wives, to whom he bequeathed his landed property in Europe and America. His rights of government he left in trust to the Earls of Oxford and Powlett, to be disposed of; but no sale being ever made, the government, with the title of Proprietaries, devolved on the surviving sons of the second family.

Penn's numerous works were collected, and a life prefixed to them, in 1726. Select editions of them have been since published. Mr. Clarkson's 'Life,' Proud's 'History of Pennsylvania,' and Franklin's 'Historical Review, &c. of Pennsylvania,' for a view of the exceptions which have been taken to Penn's character as a statesman, may be advantageously consulted.

[Pg 18]Joseph Addison was the eldest son of the Reverend Lancelot Addison, and was born at the parsonage of Milston in Wiltshire, of which his father was then rector, on the 1st of May, 1672. It is asserted by Thomas Tyers, in his 'Historical Essay on Mr. Addison,' that he was at first supposed to have been born dead; and it appears that even after he revived he was thought so little likely to live, that they had him baptized the same day. He was put to school, first at the neighbouring town of Amesbury, then at Salisbury, then, as Dr. Johnson was informed, at Lichfield, though probably only for a short time, on his father being made dean of Lichfield, and removing thither with his family in 1683; and thence he was sent to the Charter-house (not however upon the foundation) either in that or the following year. At the Charter-house he made his first acquaintance with Steele, whose name their long friendship[Pg 19] and the literary labours in which they were associated have for ever united with his.

In 1689 he was entered of Queen's College, Oxford (the same to which his father had belonged); but two years after he was elected a demy (or scholar) of Magdalen College, on the recommendation of Dr. Lancaster, afterwards provost of Queen's, who had been struck by some of Addison's Latin verses which he accidentally met with. To a date not long subsequent to this belong some both of his Latin and of his English poems that have been preserved, though they were not all published till many years afterwards. His first printed performance was a short address to Dryden, in English verse, which is dated Magd. Coll. Oxon, June 2, 1693, and which Dryden inserted in the 3rd vol. of his 'Miscellany Poems,' published in that year (p. 245 of the fourth edition, 1716). The 4th vol. of the 'Miscellany Poems' contains (pp. 6-17) 'A Translation of all Virgil's Fourth Georgic, except the story of Aristæus, by Mr. J. Addison, of Magd. Coll. Oxon.;' (pp. 20-22). 'A Song for St. Cecilia's Day, at Oxford, by Mr. J. Addison;' and (pp. 288-292). 'An Account (in verse) of the greatest English Poets,' by the same, dated April 3, 1694, and addressed to Mr. H. S., whom the writer styles his "dearest Harry," and who is no other than Sacheverell, the afterwards famous high-church parson. A verse translation by Sacheverell, of a portion of the first Georgic, dedicated to Dryden, is given in the same volume of the 'Miscellany Poems' (p. 148), in which Addison's first printed verses appeared. Spence (Anecdotes, edited by Singer, p.50) reports Pope to have stated that the letter to Sacheverell was not printed till after Addison's death; and this account has been commonly repeated. Pope is said to have added, "I dare say he would not have suffered it to be printed had he been living; for he himself used to speak of it as a poor thing. He wrote it when he was very young; and, as such, gave the characters of some of our best poets in it only by hearsay. Thus, his character of Chaucer is diametrically opposite to the truth;[Pg 20] he blames him for want of humour. The character he gives of Spenser is false too; and I have heard him say that he never read Spenser till fifteen years after he wrote it." It was not likely that the poem should have thus become the subject of conversation between Pope and Addison if it had not been printed, and if Addison, as is intimated, would gladly have concealed its existence. In other respects also the account here attributed to Pope is incorrect. Chaucer is not blamed for want of humour; he is expressly called a "merry bard;" and it is only affirmed that his wit has become obscure and his jests ineffective from the rust that has grown over his language. Spenser certainly is treated as a mere barbarian, and without the most distant suspicion of any of his real qualities. The most ambitious passage is that relating to Milton, beginning—

"But Milton next, with high and haughty stalks,

Unfettered in majestic numbers walks:"

a part of which has often been quoted. It is worth notice as evincing

that the Paradise Lost was generally appreciated (for it has all the air

of expressing a common or universal opinion) long before the appearance

of the critical papers in the 'Spectator,' which many people suppose

first Æneis) that it had been given him by a worthy friend who desired to

have his name concealed; and the prose arguments throughout the

translation, similarly acknowledged, were likewise furnished by Addison.

Although he did not name Addison in reference to these contributions,

Dryden in his 'Postscript to the Reader,' printed at the end of his

translation, pays a compliment to "the most ingenious Mr. Addison of

Oxford," after whose bees, he says, his own later swarm is scarcely

worth the hiving, alluding to the version of the fourth Georgic. About

this time also were written some, at least, of the[Pg 21] Latin poems which

were first printed, under Addison's own care, in the second volume of

the 'Musarum Anglicanarum Analecta,' published in 1699:—the 'Barometri

Descriptio;' 'Πυγμαιογερανομαχία, sive Prælium inter Pygmæos et Grues

commissum;' 'Sphæristerium' ('The Bowling Green'); 'Machinæ

Gesticulantes' ('The Puppet Show'); and two or three other shorter

pieces. That on the peace of Ryswick, entitled 'Pax Gulielmi Auspiciis

Europæ reddita,' also contained in that collection, had, we believe,

been printed before in 1697.

Addison took his degree of M.A. 14th February, 1693; and at this time it was his intention to enter the church, as he intimates in the conclusion of his letter to Sacheverell. There has been some dispute about the motives which changed this purpose; his friend and literary executor, Tickell (Preface to his collected works), represents him as having been actuated by a "remarkable seriousness and modesty," which made him think the duties of the priesthood too weighty for him. Steele, however (Preface to the second edition of The Drummer), insists that the true reason was the interference of Lord Halifax (then Mr. Charles Montague), who held out more inviting prospects to him in another direction. Appealing to Congreve, to whom the preface is addressed, Steele says, "As you were the inducement of his becoming acquainted with my Lord Halifax, I doubt not but you remember the warm instances that noble lord made to the head of the college, not to insist upon Mr. Addison's going into orders." Soon after this introduction to Montague, he addressed, in 1695, a poem to Lord Keeper Somers on one of King William's campaigns, which was followed in 1697 by the Latin verses on the peace of Ryswick, already mentioned; but it was not till after two years more of expectation, or, at least, of getting nothing, that he at last obtained through Somers a pension from the crown of 300l. a-year, to enable him to travel. He first took up his residence for above a year at Blois, probably, as Johnson suggests, to learn the French language. Spence (Anecdotes, p. 184) gives the following[Pg 22] account as received from the Abbé Philippeaux, who remembered him there: "He would rise as early as between two or three in the height of summer, and lie abed till between eleven and twelve in the depth of winter. He was untalkative whilst here, and often thoughtful; sometimes so lost in thought that I have come into his room and staid five minutes there before he has known any thing of it. He had his masters generally at supper with him, kept very little company beside, and had no amour whilst there that I know of; and I think I should have known it if he had had any." It must have been before his going abroad, we may here observe, that Addison acquired his habit of indulgence in wine, if what Spence was told by Dennis (Anecdotes, p. 45) be true, that although Dryden was generally an extremely sober man, for the last ten years of his life, during which he was much acquainted with Addison, he drank with him more than he ever used to do, "probably so far as to hasten his end." But this account would carry us back to Addison's nineteenth year, which seems an early date for either his hard drinking, or so great an intimacy with Dryden.

Addison remained abroad, principally in Italy, till the death of King William, in the spring of 1702, deprived him both of his pension and of an appointment which he expected to receive as secretary to Prince Eugene. Swift, in some lines quoted by Tyers, affirms that he was compelled by his pecuniary difficulties to become the tutor of a travelling squire; and the meanness of his appearance when he returned to England is said to have given visible testimony of his poverty. While abroad, he wrote, in 1701, his "Letter from Italy" to Montague, which has generally been regarded as the happiest of his poetical productions. During his residence in Italy, also, he is said to have written his 'Dialogues on Medals,' which, however, were not published till after his death. Signor Ficoroni told Spence (Anecdotes, p. 93) that he did not go any depth in that study: "All the knowledge he had of that kind," said Ficoroni, "I believe he had from me, and I did not give him above[Pg 23] twenty lessons upon that subject." Here, too, according to Tickell, he wrote the first four acts of his Cato; and Tonson told Spence (Anecdotes, p. 46) that he actually saw them when he met Addison accidentally, on his return, at Rotterdam. But Dr. Young, in a note which Spence has appended to this statement, assures us that, to his knowledge, all the five acts were written at Oxford, and sent from thence to Dryden. If so, it would have been interesting to know what Dryden thought of the play, of which, when the author brought it to Pope, as just finished, many years after, that poet gave it as his opinion that he had better not act it, and that he would get reputation enough by only printing it, thinking the lines well written, but the piece not theatrical enough (Spence, p. 196). Notwithstanding Young's confident assertion, it seems certain that the fifth act was either not written at all till long after the time of which he speaks, or was, at least, entirely re-written at a much later date.

Very soon after his return from Italy, Addison published his 'Travels,' inscribing the volume to Lord Somers. It was at first received somewhat coldly; but Tickell states that the price rose to five times its original amount before the second edition appeared. His friends, however, being now out of power, nothing was done for Addison for some time, and how he managed to subsist we are not informed. The first thing we hear of him is his engagement by Godolphin, on the recommendation of Lord Halifax, to celebrate the victory of Blenheim, gained in August, 1704, which produced his poem entitled 'The Campaign,' published in the end of that or beginning of the following year. This performance brought him a great accession of fame; and it also opened to him a career of prosperity which was never interrupted. While the poem was still unfinished, being advanced only to the celebrated simile of the angel, which occurs a little past the middle, it was read or communicated to Godolphin, who was so pleased with it that he immediately appointed the author to the place of one of the excise commissioners of appeal, just become[Pg 24] vacant by the death of Locke. Locke died on the 28th of October, and it appears that the new commission in which Addison's name was inserted was made out on the 16th of November. (Beatson's Political Index, ii. 375.) This post, it may be presumed, was very nearly or altogether a sinecure; Addison, whose duties were perhaps done for him by the other four commissioners, continued to hold it till he lost all his appointments on the change of ministry in 1710. In 1705 he is said by Niceron, in 'Mémoires des Hommes illustres' (xxxi. 71), to have attended Halifax to Hanover; but the fact, though it has been generally admitted, would seem to be more than doubtful if it rest only on that authority. In the following year, 1706, according to Tickell, he was selected to be under-secretary to Sir Charles Hedges, secretary of state; and when Hedges was, in December of that year, succeeded by the Earl of Sunderland, Addison continued to serve under the new secretary. The 'Biographia Britannica,' however, is mistaken in representing Hedges as having been newly appointed to office when Addison became under-secretary: he had been secretary of state since May, 1702. In 1707 Addison published, anonymously, a pamphlet in support of the government, entitled 'The Present State of the War,' which, although he is not known to have acknowledged it during his life, is printed in Tickell's edition of his collected works. This year, also, he wrote and published his opera of 'Rosamond,' by way of an attempt to supersede or cope with the Italian opera by a similar combination of music and recitative in the vernacular tongue; but, although the poetry has since been greatly admired, the piece was unsuccessful when brought out upon the stage, principally, it is said, owing to the indifferent style in which the songs were set to music. It has since been reset by Arnold. Besides his primary or more professed object of rivalling the Italian opera, Addison took an opportunity, in this production, of paying his court to the master of the ministry, the Duke of Marlborough, whose praises it celebrated in a very flattering strain, and to whose wife, the celebrated[Pg 25] Duchess Sarah, the author inscribed it on its publication. About the same time, the 'Biographia Britannica' states, he assisted Steele in his comedy of the 'Tender Husband;' but that drama was published two years before 'Rosamond.' Addison wrote the prologue spoken when it was acted at Drury Lane; and when it was soon after published, Steele dedicated it to his friend, in an address in which he acknowledges that he had been indebted to him for several of the most successful scenes. In the beginning of the year 1709, when the Earl (afterwards Marquis) of Wharton, father of the more notorious duke, who some years later became, for a short time, the patron of Young, went over as Lord Lieutenant to Ireland, he took Addison with him as his secretary; and the latter was, at the same time, appointed to the sinecure office of keeper of the records in Birmingham Tower, with a salary augmented to 300l. a year. He was in Dublin when the 'Tatler' was commenced in London by Steele, on the 12th of April; and Addison is said to have detected his friend by a remark on Virgil in one of the papers, which he recollected having communicated to him: it may be found in No. 6, published the 23rd of April, 1709. Addison soon after became a contributor; his first paper formed part of No. 20, which appeared on the 26th of May, and he soon took a larger share in the work than any other writer, except Steele. In his preface to the first collected edition, Steele acknowledged his obligations with his characteristic generosity and warmth of expression: "I have only one gentleman, who will be nameless, to thank for any frequent assistance to me, which, indeed, it would have been barbarous in him to have denied to one with whom he has lived in an intimacy from childhood, considering the great ease with which he is able to despatch the most entertaining pieces of this nature. This good office he performed with such force of genius, humour, wit, and learning, that I fared like a distressed prince who calls in a powerful neighbour to his aid: I was undone by my auxiliary; when I had once called him in, I could not subsist without dependence on him." Yet Addison's contributions to the 'Tatler'[Pg 26] scarcely amount to a fourth part of Steele's. We may here complete the account of the literary partnership of the two friends in the other periodical papers to which the success of this first undertaking in that line gave birth. The 'Tatler,' published thrice a week, was dropped with the 271st number, published the 2nd of January, 1711; the first number of the 'Spectator' appeared on the 1st of March following, and it was continued at the rate of a paper every day, except Sundays, till the 6th of December, 1712, when it was concluded with No. 555. The quantity of Addison's contributions to this first series of the 'Spectator' probably rather exceeds that of Steele's, and does not amount to much less than half of the work. To the first volume of the 'Guardian,' extending also at the rate of six papers a week, from the 12th of March, 1713, to the 15th of June in the same year, he contributed one paper only; but of the ninety-two papers composing the second and concluding volume, about fifty are assigned to Addison. The 'Guardian' terminated with No. 175, published the 1st of October, 1713; and then the 'Spectator' was revived on the 18th of June, 1714, and carried on, as a thrice-a-week paper, till the 20th of December. Of the eighty papers composing the second series of the 'Spectator' (to which Steele did not contribute), Addison is understood to have written twenty-four, all published before the 1st of October; he is not supposed to have had any concern with the work for the remaining three months of its existence.

A change in the political world had left him abundant leisure for literature during the greater part of the time that these publications were going on. The ministerial revolution which took place in the summer of 1710, although it was not completed till the dismissal of Godolphin in the beginning of August, appears to have jerked Addison out of office at the first shock: a new board of commissioners of appeal was appointed on the 25th of May, from which he was left out, and we may conjecture that he lost his Irish secretaryship and his place of keeper of the records about the same time. From this date he remained without any public employment for more than[Pg 27] four years; which interval, however, offers a few matters requiring notice besides his connexion with the 'Tatler,' 'Spectator,' and 'Guardian.' In September and October, 1710, he took his revenge on the new Tory ministry in a series of anonymous papers, five in all, published under the title of 'The Whig Examiner,' which are, of all the effusions of his wit and humour, perhaps the most exuberant and the most caustic. In 1711 he purchased an estate at Bilton, in Warwickshire, for 10,000l.: it is difficult to understand where he got the money, or any part of it, although he is said to have been assisted by his brother Gulston, who was governor of Madras. Gulston had obtained the appointment, according to Oldmixon, through his brother's interest; and this writer adds that when he died Addison got six or seven thousand pounds by the sale of his effects. "The first printed account of Addison's," says Tyers, alluding perhaps to the article in the 'General Biographical Dictionary,' "supposes that the death of his brother in the East Indies put him into plentiful circumstances". Early in 1712 his acquaintance with Pope commenced; he had already lived on intimate terms with Pope's friend Swift, while in Ireland, notwithstanding the opposition of their politics; and Pope and he were probably now brought together by Steele. In April, 1713, occurred one of the most memorable events in Addison's history—the performance and publication of his tragedy of 'Cato.' The 'Biographia Britannica,' Johnson, and most of the accounts state that it had a run of thirty-five successive nights; but, according to Baker's 'Biographia Dramatica' (Reed's edition), the number of times it was acted during its first run was only eighteen. Be this as it may, there is no doubt about its having been received with immense applause; to which it is equally undoubted that the political feeling of the moment contributed no inconsiderable share. "The Whigs," as Johnson puts it, "applauded every line in which liberty was mentioned, as a satire on the Tories; and the Tories echoed every clap to show that the satire was unfelt." This year, too, Addison wrote another political pamphlet, 'The late Trial and Conviction of Count Tariff,' an[Pg 28] attack upon the French commercial treaty, which, although published without his name, has been authenticated as his by being included in the complete edition of his works published by his executor after his death.

After the death of Queen Anne, in August, 1714, he was appointed secretary to the lords of the regency; and when King George came over it is said that there was some thought of making him secretary of state, if he could have been prevailed upon to accept the post. This is distinctly asserted by Tyers, and some particulars are given confirmatory of the story in his 'Historical Essay,' pp. 53-55. He was, in fact, reappointed in the first instance to his former office of secretary to the lord lieutenant of Ireland, now the Earl of Sunderland, under whom he had already served in another department; and when this arrangement was broken up by the almost immediate removal of Sunderland, Addison was made one of the lords of trade early in 1715. It was in the month of June of that year that the memorable incident occurred of the publication by Tickell of a translation of the first book of the Iliad, suspected to have been written by Addison, at the same moment at which the first volume of Pope's translation came out; a proceeding which turned a coldness that had for some time subsisted between Addison and Pope into a complete separation, and is understood to have prompted the well-known lines in which the character of Addison is sketched with so much severity by Pope, now inserted in the Prologue to the Satires, which was not published till after Addison's death, although this particular passage was certainly written and also handed about some years before that event. The most minute and elaborate investigation of the circumstances of this curious affair is contained in a long note on the article 'Addison' in Kippis's edition of the 'Biographia Britannica,' which is known to have been drawn up by Sir William Blackstone. (See also Spence's 'Anecdotes,' pp. 146-149.) In this same year (1715), too, was published, and likewise brought out on the stage, though with no success, the comedy of 'The[Pg 29] Drummer, or the Haunted House,' which Addison gave to Steele, and which the latter reprinted in 1722, with a preface addressed to Congreve, stating his conviction of its being by Addison, after it had been omitted in Tickell's collection. No doubt is now entertained that Addison is really the author of this piece: indeed, we have direct evidence of his having acknowledged it as his; Theobald, in a note upon the first act of Beaumont and Fletcher's 'Scornful Lady,' speaking of the character of Savil, states that Addison told him he had sketched out his character of Vellum in 'The Drummer' purely from that model. These speculations on the public discernment, however, did not occupy all his leisure. On the 23rd of September in this year, soon after the breaking out of the rebellion, he commenced a political periodical paper, in defence of the established government, under the title of 'The Freeholder,' which he kept up with great spirit, at the rate of two numbers a week, till the 29th of June in the next year. On the 2nd of August, 1716, he married Charlotte, Countess Dowager of Warwick and Holland (who had been a widow for fifteen years), after a long suit, which Johnson quotes Spence's MS. as representing to have commenced in Addison's acting as tutor to her son, the young earl; although it does not appear at what time of his life he could well have been employed in that capacity, unless, indeed, we are to adopt the notion of Tyers, who seems to think that the earl may have been the person to whom Swift speaks of Addison having acted as travelling tutor before his return from Italy in 1702. In the printed edition of Spence's 'Anecdotes,' all that we find (p. 48) is an assertion of Tonson, the bookseller, that he had thoughts of getting the lady "from his first being recommended into the family." The marriage made him nominal master of the mansion now called Holland House, but is understood to have added nothing to his happiness; the countess, it seems, holding it to be her right, or her duty, to make up for her condescension in giving him her hand by never[Pg 30] forgetting the difference of their rank in her after-behaviour.

On the 16th of April, 1717, after the breaking-up of the administration of Walpole and Townshend, Addison was elevated to a place in the new cabinet as one of the principal secretaries of state, Sunderland being the other. Pope told Spence ('Anecdotes,' p. 47) that Addison accepted this appointment "to oblige the Countess of Warwick, and to qualify himself to be owned for her husband." It was, in his opinion, "the worst step Addison ever took"—even his marriage itself is not stated to have been mentioned as an exception. Tyers gives a passage from a letter written about the time by Lady M.W. Montague to Pope, in which she says, "I know that the post was almost offered to him before. Such a post as that, and such a wife as the countess, do not seem to be in prudence eligible for a man that is asthmatic; and we may see the day when he will be heartily glad to resign them both." Addison was first returned to parliament for Lostwithiel, at the general election in 1708; but, after sitting from 18th November, 1708, to 20th December, 1709, he was declared to have been not duly elected; he was then returned for Malmesbury, on a vacancy occurring for that place, in March, 1710, within a month of the close of the same parliament; and he continued to represent Malmesbury till his death, having been re-elected in 1710, 1714, 1715, 1716 (on his being made a lord of trade), and 1717 (on being made secretary of state and a privy councillor). It was the Marquis of Wharton, Young told Spence, who first got him a seat in the House of Commons (Anecdotes, p. 350). But he never spoke in the House (although there are traditions of his having once made the attempt); and, with all his readiness as a writer in his proper line, he is said to have proved almost equally inefficient in the ordinary business of his office. The consequence was, that, after bearing up under these discouraging circumstances for not quite a twelvemonth, he resigned his secretaryship on the plea of ill health, and retired on a pension of[Pg 31] 1500l. (Tyers says 1700l.) a year. His friend Craggs was appointed his "successor on the 14th of March, 1718. In thus relinquishing, however, somewhat ingloriously, the race of political ambition, he did not cease to take an interest in the politics of the day. In the early part of the following year he engaged in a public controversy with his old friend Steele on the subject of the government bill for the limitation of the peerage, in defence of which, and in reply to Steele's paper called 'The Plebeian,' he published two pamphlets, under the title of 'The Old Whig,' Nos. 1 and 2. They were published anonymously, and were not reprinted by Tickell; but no doubt has ever been entertained of their having been written by Addison: Steele himself, in his rejoinder at the time, plainly intimated that he took them to be his; and the contemptuous style in which 'The Old Whig' spoke of his antagonist as "little Dickey," is understood to have broken off the friendly intercourse which had subsisted between them from boyhood. An unfinished treatise on the 'Evidences of the Christian Religion,' which was printed in Tickell's edition of his works, was another fruit of Addison's leisure after he retired from office; composed, according to Pope, when, having broken down, or sunk in character, as a politician, he thought of returning to the profession for which he was originally designed, and had an eye to the lawn (Spence's Anecdotes, p. 192). But his health soon completely gave way; he was attacked by a shortness of breath, which was followed by a dropsy; and he expired at Holland House on the 17th of June, 1719. Tyers mentions that Tacitus Gordon (that is, Gordon the translator of Tacitus) used to say that he killed himself drinking the Widow Trueby's water (for a eulogy upon the virtues of which the reader may consult the 'Spectator,' No. 329). By the Countess of Warwick (Charlotte, only daughter of Sir Thomas Middleton, of Chirk Castle, Denbighshire, and a grand-daughter of Sir Orlando Bridgman, keeper of the great seal in the reign of Charles II., who survived him several years) Addison left a daughter, who died unmarried in 1797. Tyers[Pg 32] (p. 56) quotes Oldmixon as stating, in his 'History of England,' that to this daughter and to Lady Warwick he left his fortune, amounting to about 12,000l.; and he further mentions (p. 63) that Mr. Symonds, professor of Modern History at Cambridge, had told him that Miss Addison was then (in 1783) in the enjoyment of an income of more than 1200l. a year. The accounts we have of this lady differ somewhat. "She inherited her father's memory," says the notice of her death in the 'Annual Register' (xxxix. 12), "but none of the discriminating powers of his understanding: with the retentive powers of Jedediah Buxton, she was a perfect imbecile. She could go on in any part of her father's works, or repeat the whole, but was incapable of speaking or writing an intelligible sentence." In the 'Beauties of England,' however (Warwickshire, p. 81), it is said, "She is mentioned with love and veneration by the neighbouring peasantry; and several articles in her will creditably evince her charitable disposition." She left her estate to a younger son of Lord Bradford, to whom she was related through her mother. Addison's library, which had remained entire throughout her lifetime, was sold by Messrs. Leigh and Sotheby, in May, 1799, in 856 lots, for 456l. 2s. 9d.

Anecdotes of Addison's private life, and traits of his habits and character, have been handed down in great abundance by Spence and others; so that, although there is little or nothing avowedly autobiographical in his own writings, we have, perhaps, as complete a picture of the man as of any other individual of that age of celebrated wits. He was, undoubtedly, accounted one of the principal figures of his time; and even now there is scarcely any other name of that day with which the world is more generally familiar. That he occupied so much of the eye of the world in his own day, he owed in part to the eminence of his social position; and there were also some points both in his moral and intellectual nature that were especially fitted to establish him in the favour of the most numerous class of the reading public. Neither his writings nor his conduct offered anything to startle[Pg 33] or discompose commonly received notions. The conventional proprieties, which make so large a part of the general morality, were in no danger of being rudely disturbed by anything he was likely either to write or to do. Some of the social habits attributed to him would seem to betray a greater cordiality or robustness of original nature than he commonly showed; but even his love of wine is not recorded to have ever been suffered to carry him beyond a safe limit; he went to the length he did in that indulgence, because, perhaps from the coldness of his constitution, he could stand more hard drinking than the generality of other men without losing his caution and regard to appearances. The strongest testimony has been borne by those who knew him intimately to the charms of his conversation when he felt himself free from all restraint. "He was," says Steele, "above all men in that talent called humour, and enjoyed it in such perfection that I have often reflected, after a night spent with him apart from all the world, that I had had the pleasure of conversing with an intimate acquaintance of Terence and Catullus, who had all their wit and nature, heightened with humour more exquisite and delightful than any other man ever possessed." (Preface to The Drummer. Lady Mary Wortley Montague told Spence that "Addison was the best company in the world." Anecdotes, p. 232.) Dr. Young's account was, that though he was rather mute in society on some occasions, "when he began to be company, he was full of vivacity, and went on in a noble stream of thought and language, so as to chain the attention of every one to him" (p. 335). "Addison," said Pope, "was perfect good company with intimates; and had something more charming in his conversation than I ever knew in any other man" (p. 50). But this was only when there was no one by of whom he was afraid. "With any mixture of strangers," Pope added "and sometimes only with one, he seemed to preserve his dignity much, with a stiff sort of silence." Young admitted that he "was not free with his superiors." Johnson quotes Lord Chesterfield as somewhere affirming that "Addison was the most[Pg 34] timorous and awkward man that he ever knew." Coarser minds, again, from the formality and stiffness of manner in which he wrapped himself up from their inspection, were led to set him down for a mere piece of hypocrisy and cant. Mandeville, the author of the 'Fable of the Bees,' after an evening's conversation with him, characterized him as a "parson in a tye-wig;" and Tonson, who hated parsons in any kind of wigs as much as Mandeville, and who, besides, had quarrelled with Addison, and did not like him, used to say of him after he had quitted his secretaryship, "One day or other you'll see that man a bishop! I'm sure he looks that way; and, indeed, I ever thought him a priest in his heart." (Spence, p. 200.) It must be acknowledged that this caution and cowardice spoiled Addison's character in some points of great importance; he was not a man on whom his friends could rely; and the way in which he lost or offended more than one of them was not to his credit. In his conduct both to Pope and to Steele, there was something underhand and treacherous—something of the "willing to wound, but yet afraid to strike," which the former has imputed to him. To Gay, again, he seems to have behaved ill without having been either detected or suspected at the time. A fortnight before his death he sent Lord Warwick for Gay, who had not gone to see him for a great while; and when they met, Addison told him "that he had desired this visit to beg his pardon; that he had injured him greatly; but that if he lived he should find that he would make it up to him." (Spence, p. 150.) Here again we see the conscientiousness of the man struggling with, and in the end, very nobly mastering, his more ignoble propensities; for it would be a great mistake to conclude from these instances of deceit and littleness, that the regard he professed for virtue was not both real and deeply felt. In part the restraint he put upon his outward behaviour may be attributed to his dread of public opinion, and his desire to stand well with the very numerous class whose judgment is principally swayed by such decorum and propriety of mere demeanour: in part he seems to have[Pg 35] done violence in this way to higher qualities which were in his nature, and to have checked the growth both of principles and powers which might have made his whole humanity a finer and higher thing than it really was; but there can be no doubt whatever, for all that, that he was a sincere and zealous friend both to morality and religion. He had his weaknesses, like all men; and in some respects, he even led a somewhat free life, when he was out of the public eye; but "of his virtue," as Johnson has observed, "it is a sufficient testimony that the resentment of party has transmitted no charge of any crime." The pious composure in which he died, as evinced by the anecdote of his parting interview with the young nobleman, his step-son,—first told by Dr. Young in his 'Conjectures on Original Composition,' published in 1759, though previously alluded to by Tickell, in his Elegy on Addison—is known to most readers. Dr. Young's words are:—"After a long and manly, but vain struggle with his distemper, he dismissed his physicians, and with them all hopes of life. But with his hopes of life he dismissed not his concern for the living, but sent for a youth nearly related, and finely accomplished, but not above being the better for good impressions from a dying friend. He came; but, life now glimmering in the socket, the dying friend was silent: after a decent and proper pause, the youth said, 'Dear Sir, you sent for me; I believe and hope that you have some commands: I shall hold them most sacred.' May distant ages not only hear but feel the reply. Forcibly grasping the youth's hand, he softly said, 'See in what peace a Christian can die.' He spoke with difficulty, and soon expired." Lord Warwick did not long survive his step-father: he died at the age of twenty-three, in August, 1721. Tyers says that "he was esteemed a man of great parts."

Addison's writings present something of the same struggle of opposite principles or tendencies which we find in his character as a man, resulting likewise in the same general effect, of the absence of everything offensive combined with some qualities of high, but none[Pg 36] perhaps of the highest, excellence. Notwithstanding all the hesitation and embarrassment he is said to have shown on some occasions in the performance of his official duties, so that a common clerk would have to be called in to draw up a despatch which could not wait for his more scrupulous selection of phraseology, he usually wrote easily and rapidly. "When he had taken his resolution," Steele has told us, "or made his plan for what he designed to write, he would walk about a room and dictate it into language with as much freedom and ease as any one could write it down, and attend to the coherence and grammar of what he dictated." (Preface to The Drummer.) Pope told Spence, however, that, though he wrote very fluently, "he was sometimes very slow and scrupulous in correcting." "He would show his verses," said Pope, "to several friends, and would alter almost everything that any of them hinted at as wrong. He seemed to be too diffident of himself, and too much concerned about his character as a poet; or, as he worded it, 'too solicitous for that kind of praise, which, God knows, is but a very little matter after all.'" (Anecdotes, p. 49.) By this way of expressing himself, he probably meant to mortify Pope, as well as to make amends, by a piece of moral profession, for his too anxious pursuit of an object which he had neither the self-control to relinquish, nor the heart to enjoy. To Pope he seemed to value himself more upon his poetry than his prose. (Spence, p. 257.) Except, however, in some of his Latin poems, he has scarcely given any example in verse of that easy humour and lively description in which he certainly most excelled. As a writer of serious and elevated poetry, he must be ranked, even without reference to the claims of the school to which he belongs, as standing only a little way above ordinary writers. His 'Cato,' his most ambitious effort, has some stately rhetoric in the principal scenes; but scarcely anything either of true poetic fire, or of the dramatic spirit. Even of strength and beauty of imagination, he has shown much more in his prose than in his poetry; so much, indeed, in one or two instances, as to seem to prove that what he most wanted[Pg 37] to make him a much greater poet was only more self-confidence and daring. There is far more poetry in his prose 'Vision of Mirza' and his 'Roger de Coverley,' than in all the verse he ever wrote. But his most remarkable and peculiar quality, and that in which he most overflowed, was undoubtedly his light, graceful, delicate humour; never, indeed, rising to anything very subtle or aerial; seldom pouring itself out in any rush of mere derisive mirth; not dazzling us with its sparkles of wit and fancy; but with its quiet, even, smiling stream refreshing and illuminating all things, and awakening a pleasurable sense of the ludicrous probably in a larger number and greater variety of minds than any other writer ever succeeded in touching with that emotion. It is the only humour, perhaps, that is perfectly to the satisfaction of the great multitude of reading men and women, who find Swift and Sterne revolting, and Shakspere unintelligible, but to whom Addison enlivens the picture of their familiar daily life, or the general aspect of human society and human nature, with a bright transparent varnish, the effect of which has nothing in it to startle the most simple understanding. A great change of manners, however, and a considerable change of taste, are fast diminishing the once universal popularity of the 'Tatler' and 'Spectator;' and they will probably very soon be little read. Addison's prose has been praised by Johnson as "the model of the middle style;" and, while it is eminently easy, unaffected, and perspicuous, it has a fair degree of purity, and often considerable melody and grace of expression. But, with all its merits, it has scarcely character enough to maintain itself as a model; and it may be apprehended that it is a rare thing now for any one "to give his days and nights to the volumes of Addison," as Johnson recommends, whatever description of English style he wishes to attain. (From the Biographical Dictionary of the Society of Useful Knowledge.)

[Pg 38]John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, the restorer of the tarnished lustre of British arms, the ablest general and one of the most consummate statesmen of his times, was born at Ashe in Devonshire, on the 24th of June, 1650, just five days before Oliver Cromwell marched into Scotland, to open that memorable campaign which was terminated by his great victory at Dunbar. As devoted royalists, the Churchills were at this time under a cloud.

Our hero was the second son of Sir Winston Churchill, a gentleman of ancient family (said to have been settled in the West of England ever since the Norman conquest) whose fortunes had suffered severely during the civil wars, through his steady adherence to Charles I. Sir Winston's wife, and the mother of his numerous family, was Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Drake of Ashe, who came of the same good old Devonshire stock as Sir Francis Drake, that illustrious warrior and circumnavigator[Pg 39] of the Elizabethan age. It should appear that during their season of eclipse, the Churchills were almost entirely dependent on the more fortunate Drakes, who had sided with the Parliamentarians. During his childhood and boyhood John Churchill was familiarised with straits and privations, and with many of the unpleasantnesses attendant on poverty. This may have strengthened his character, and have quickened his reflection and mental resources; but it may also have implanted in his nature that love of money with which he was very generally reproached in after life. One day, in his old age, when he was wealthy as well as famous, as he was looking over some papers in his scrutoire with General Lord Cadogan, he opened one of the little drawers, took out a green purse, turned some broad pieces out of it, and, after viewing them for some time with a satisfaction that appeared very visibly in his face, he said, "Cadogan, observe these pieces well; they deserve to be observed! There are just forty of them: 'tis the very first sum I ever got in my life, and I have kept them always unbroken from that time to this day." "This," adds Pope, who told the anecdote, "shows how early and how strong this passion must have been upon him." But it may also show that Marlborough's first forty pieces had been obtained with vast difficulty. On the restoration in 1660 his father was among the vast crowd of suffering royalists who put in their claims of compensation or reward to an extravagant and heartless prince. Sir Winston Churchill was far more successful than the majority of these impatient supplicants, and than many men who had not suffered less, and who had done far more than he for the royal cause. He was rewarded with a place at the Board of Green Cloth, and sundry small offices under the crown for himself, and with the more questionable benefit of appointments for his children in the profligate court of Charles II. Arabella Churchill, his daughter, became, in the first place, maid of honour to the Duchess of York (Anne Hyde), and next, mistress to her husband the Duke, afterwards James II.; and John Churchill, our hero, who was appointed page[Pg 40] to the same prince, indisputably owed his early advancement to his sister's disgraceful connexion with royalty. They were a remarkably handsome race. Arabella Churchill was the only one of James II.'s many mistresses that had any pretension to beauty. Charles II. said that his brother chose his ugly favourites as penances. One of the moral favourites is reported to have said herself, "I know not for what he chose us; we were none of us handsome, and if any of us had wit he was too dull to find it out!" It is remarkable that one of the fruits of the connexion between James and Arabella Churchill, James Fitzjames, Duke of Berwick, proved a commander of renown only less illustrious than his maternal uncle Marlborough.

The natural genius and merits of young John Churchill were, however, of far too high an order to be solely dependent on the patronage which had sullied the honour of his house. He would have found his way to greatness if James had never seen his sister. Not even a neglected education could dwarf his abilities or stop his rise. Except the practical self-tuition he afterwards gave himself, his education was confined to a short residence at St. Paul's school, London; but here he gave early indications of spirit and intelligence, although he failed to acquire that taste and love of literature which must ever form one of the elements of a completely great man. This deficiency, and his want of sympathy with men of letters, added to his want of liberality, were not without their seriously injurious effects on his fortune and reputation in after-life. Except Addison and Prior, the poets bestowed but a forced and stinted praise on his great exploits when his political party was all prevalent in the state and omnipotent at court; and when that party fell, through a court intrigue, they were nearly one and all banded against the duke,—as, also be it said, against patriotism, honour, and common sense.

His desire for a military life having been gratified, at a very early age, by his patron the Duke of York, Churchill did not play the easy part of a carpet-knight, or courtly soldier. He entered upon active service;[Pg 41] he was eager to learn his profession in actual warfare, and he distinguished himself in each of his early campaigns. In the brave defence of Tangiers against the Moors, he gained his first laurels. He had his part in the successive operations in which the English troops shared as auxiliaries to the armies of Louis XIV., during the unprincipled alliance of Charles II. with that monarch against the Dutch and William Prince of Orange (subsequently William III. of England). Here he witnessed the operations—the sieges and campaigns—of some of the most accomplished generals of modern Europe, and began to learn the art of handling great masses of troops,—an art not to be possessed by intuition or to be acquired by brief practice, and which few English-born commanders had then (or have now) the means of acquiring. The wickedness of the cause apart, Churchill could not have been placed in a better school. On the great theatre of continental warfare—the Low Countries, where he afterwards gained immortal renown as a soldier—he continued to serve from 1672 to 1677. His brilliant courage and ability, and attention to the details of duty (without which no officer will ever achieve greatness) no less than the singular graces of his person, attracted the notice of the French marshals, and the illustrious Turenne predicted that "his handsome Englishman" would one day be a thorough master of the art of war.

On the conclusion of the peace of Nimeguen, Churchill, with the rank of colonel, returned to England, where he was soon happily rescued from a career of dissipation and licentiousness (the habitual life of all the men of fashion of that generation) by an ardent and constant attachment for the celebrated woman who became his wife, and who, for good and evil, influenced the whole tenor of his subsequent life. This was Sarah Jennings, a young lady of birth, genius, and exquisite beauty, whose irreproachable purity in a most vicious age, and in the very midst of the temptations of the court, would have rendered her worthy of the uxorious love of the hero, if her imperious temper had not disgraced his submission to[Pg 42] its tyranny, cooled or alienated his political friends, and finally embittered his own domestic peace. She was daughter and co-heir of Richard Jennings, Esq., of Sandridge, near St. Albans, in Hertfordshire. She had been placed, like Churchill himself, at an early age, in the household of the Duke and Duchess of York, where she had become the favourite associate of their daughter the Princess Anne, and had acquired over the future queen that commanding influence which it belongs to the stronger to exercise over the weaker mind. Her marriage separated neither her husband nor herself from their services in the ducal household. Churchill was confidentially employed by the Duke of York on many political occasions, and was the secret agent in whom he most trusted; and when his daughter the Princess Anne was married to George, Prince of Denmark, Lady Churchill was, by the princess's express desire, made a lady of her bedchamber. According to Anne's own passionate declarations, she could not live without her charming friend,—the chosen and constant companion of her girlhood. Previously to this royal marriage Churchill had been raised, through the interest of James, to a Scotch barony. On the accession of James to the throne, he was further promoted to an English peerage by the title of Baron Churchill, of Sandridge. In 1685 he contributed by his effectual military service to the speedy suppression of the Duke of Monmouth's insane rebellion, and was rewarded with his master's unbounded reliance on his fidelity.

But James's infatuated policy soon made the crown shake on his head. Between motives of self-interest, of religion, and of patriotism, he was openly abandoned or secretly betrayed by nearly every man in his service. Among these men were many who had been deeply indebted to his bounty and patronage; for James, though a bad king, and a bitter enemy, had generally been a good, warm friend. Churchill basely betrayed his confidence, before and after the landing of the Prince of Orange at Torbay, with a deliberate, unbounded treachery, which all the sophistry of political and religious party[Pg 43] has vainly laboured to justify, and the infamy of which can scarcely be so much as palliated even by the difficult circumstances of the times. After clandestinely offering his services to William, he accepted the command of a large body of James's troops to oppose him; and after accepting that command he deserted to William. Lady Churchill also played her part at this terrible crisis, in which the ties of filial duty were broken asunder like all others. She induced her mistress, the Princess Anne, to flee from Whitehall to join the revolutionists at Nottingham; and, with the Earl of Dorset, and Compton, Bishop of London, she smuggled Anne out of the palace in a hackney-coach and at the midnight hour. The Prince of Denmark, Anne's husband, had deserted before her: on the 24th of November he supped with King James at Andover, and, straight from the royal table, he got to horse and rode over to the Prince of Orange. The illustrious Dane, though little given to talking, had been profuse in his declarations of fidelity, and had been wont to say, with an expression of the utmost astonishment, when he heard of the desertion of any of those whom James had delighted to honour,—"Est-il possible?"—Is it possible? Upon learning his nocturnal evasion, the king merely said, "How? Est-il possible gone too!" But when, on the morrow of his flight, James arrived at Whitehall and found that his daughter Anne had followed her husband's example, he exclaimed in an agony and with tears, "God help me! My very children have forsaken me."

When the revolution of 1688 was so easily and speedily completed, and when—in February, 1689—William, by the Act of Settlement, became king, Churchill received the reward of his ingratitude, being created Earl of Marlborough, and appointed to the offices of privy-councillor, and lord of the bed-chamber. Yet, like so many others, he was either dissatisfied with his recompense, or apprehensive of a counter-revolution, which would restore the dethroned king; and, throughout the reign of William III. he corresponded with James, and intrigued with the Jacobites at home and abroad. By[Pg 44] this double treason and perjury, he for ever took from his former desertion of his deluded sovereign all extenuation of a conscientious principle; he broke his allegiance to his new king whose favours he had accepted; and he branded his own inconsistency with the meanest motives of self-interest and self-preservation.