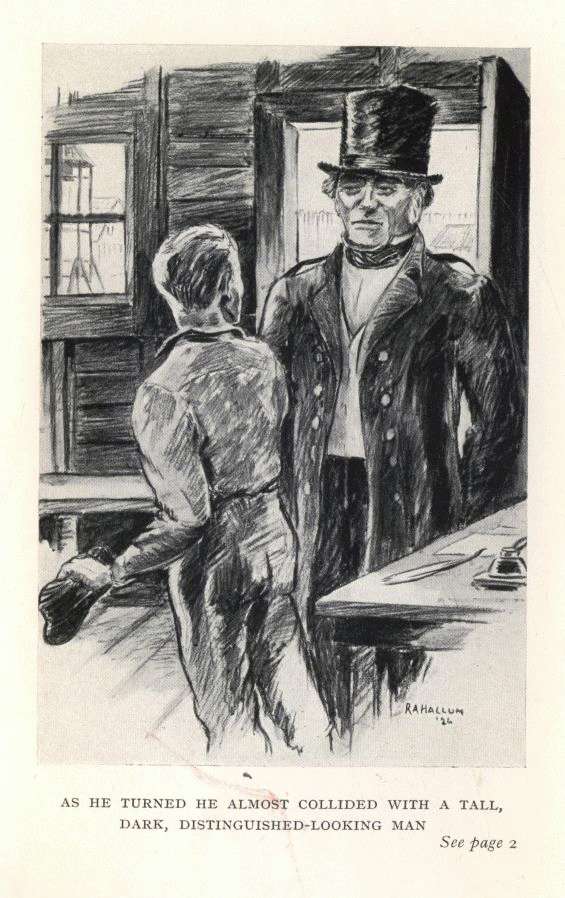

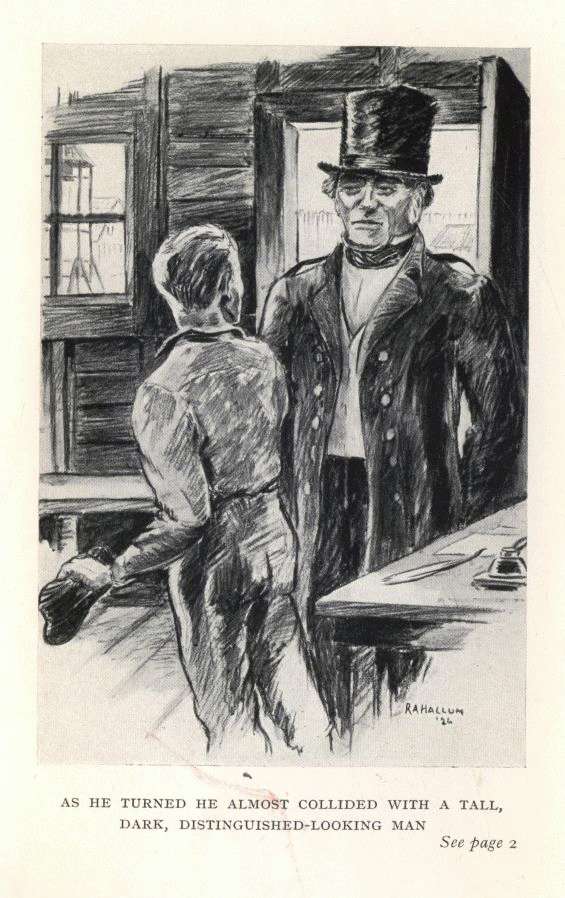

AS HE TURNED HE ALMOST COLLIDED WITH A TALL,

DARK, DISTINGUISHED-LOOKING MAN. See page 2

* An independently-produced eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Black Canyon--a story of '58

Date of first publication: 1927

Author: Bruce Alistair McKelvie (1889-1960)

Date first posted: April 10, 2014

Date last updated: April 10, 2014

Faded Page eBook #20140422

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines

AS HE TURNED HE ALMOST COLLIDED WITH A TALL,

DARK, DISTINGUISHED-LOOKING MAN. See page 2

By

B. A. McKELVIE

1927

London & Toronto

J. M. DENT & SONS LTD.

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

There are few parts of the Western World where a more picturesque and exciting tale has been woven into the fabric of nineteenth-century development than in British Columbia, Canada's Pacific province.

In The Black Canyon an effort has been made to picture just a few of the stirring incidents of a single summer, that of 1858, in the hope that the story will prove entertaining, especially to boys, and create in the minds of some a desire to further explore the romance of the West.

The main features of The Black Canyon may be corroborated by historical research, but unfortunately many of the details of value have been lost to future generations by the indifference of the times. So it is that, although Ned Stout, the last of McLennan's party, lived until January 1924, only half a dozen names of the gallant band of twenty-six are known to-day. Nor is there any exact record of the toll of lives taken in that short, savage war in the gorges above Fort Yale, although it is estimated that at least 132 white men were killed by the Indians.

The late Dr. Wymond W. Walkem, a friend of Stout, and himself a pioneer, set down, after talking to the old miner, some notes, and these, with data from the Provincial Archives, newspaper clippings, and recollections of Mr. Jason Allard, son of the officer in charge at Yale, who was there at the time, have permitted a reconstruction of the incidents with some claim to accuracy. Of course the particular happenings featuring the youthful heroes have been necessary additions for the sake of romantic interest and continuity.

That there has been an endeavour to follow closely the history of the fighting may be gathered from the following excerpts from Dr. Walkem's notes:

Before starting mining they formed a company and elected officers, the foreman being John McLennan and the assistant foreman, Archie McDonald. Jack McLennan was subsequently killed by the savages. After working for some time and getting nothing but fine gold, they started up-stream in search of the motherlode. In the meantime men had been pouring into the country ... so that when they left ... they had no fear of the two men they had left in charge of their boats being murdered by the Indians who were beginning to be aggressive.

... While moving from place to place they met many Indians ... who appeared to be quiet and peaceful. One young woman formed a strong attachment for Jack McLennan, who gave her clothing.... She followed him about, insisting on carrying his pack. At night Jack insisted on her staying with her friends, who always followed the prospectors' trail.

One night this young woman suddenly appeared and said in a subdued voice, "Hist! ... Before sun up you white men go. Go back in the stick (forests) far, far, far. Then go to salt-chuck (the ocean). Indian kill all white men in canyon, by and by kill you all. To-morrow he come. Go quick." The young woman then disappeared as silently as she had come.

... Abandoning everything but their guns and ammunition and a blanket apiece, the party struck across the hills until they reached what was afterwards known as Jackass Mountain near the Fraser River.

While passing from a small bench below Jackass Mountain to another bench the Indians, who were concealed in the brush, fired from above. Three of the miners were wounded.... These men died the next day. Travelling was now continued during the night by this small band of miners, and when day broke they went into camp fortified by timber and brush.... A man was lost every day and among these was Jack McLennan, and at Slaughter Bar six of the party were killed.... As the miners were killed, their comrades threw the bodies into the Fraser.... A night attack was made on an Indian village near the present site of Keefer's, to get food. At the crossing of a little stream four freshly caught salmon were found hanging to a pole. The hungry men were about to seize them when Mike Mallahan noticed that a blue jay that had pecked at the fish had died. The salmon were poisoned.

... At last five, the remnant of the party, ... reached China Bar where they built a fort, but were relieved the next day by Capt. Snyder and a company of volunteer miners.

The incidents related as having taken place at Nanaimo were told to me by Mr. Mark Bate, J.P., the Grand Old Man of the Coal City, who came to the establishment in 1857. For many years he was the manager of the collieries and served sixteen terms as mayor. Mr. Bate was also Government Agent at Nanaimo for a long time. He is still hale and hearty and takes an active interest in all matters of a public nature for the advancement of the community.

B.A.M.

Vancouver, 8 Feb., 1927.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

I. The Gold Stampede

II. The Grease Feast

III. The Ghost Lamp

IV. The Bastion Speaks

V. The Lure of the River

VI. The Indian Trail

VII. The Native Uprising

VIII. The Old Canoe

IX. Shooting the Rapids

X. Unexpected Meetings

ILLUSTRATIONS

He almost Collided with a Dark, Distinguished-looking Man . . . Frontispiece

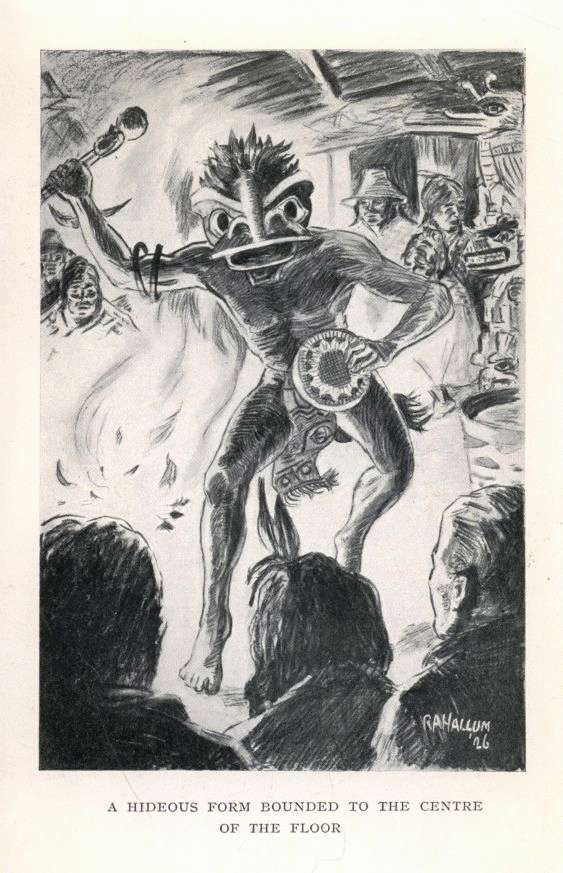

A Hideous Form bounded to the Centre of the Floor . . . facing page 26

THE BLACK CANYON

A STORY OF '58

"Is there a letter here for Neil Alexander?"

The speaker was a bright, manly-looking boy of fifteen, rather above the average height for one of his age and possessed of a width of shoulders suggestive of a strength beyond his years.

It was late in the month of April 1858. The wild flowers and tangled growth about the pickets of the stockade of Fort Victoria bore evidence of the mildness of the Vancouver Island climate, and the postmaster, to whom the inquiry was addressed, provided additional proof of the warmth of the day, for he went about his work in his shirt-sleeves. As he sorted the pile of letters and papers that had come north from San Francisco on the steamer Commodore, he whistled so noisily that he failed to hear the request.

The boy advanced a step nearer to the table on which the mail was piled. "Is there a letter here for me?"

The postmaster stopped his whistling, turned and stared at the lad for a moment, then drawled, "How should I know?"

"You're the postmaster?"

The man nodded.

"Well, you should know."

"Y' aint told me your name yet. How d'you reckon I know?"

"Yes, I did. I asked if you had a letter for Neil Alexander."

"Didn't hear you. No," he said after looking through the sorted envelopes, "nuthin' fer you."

The disappointment of the boy was apparent. His lips tightened and he swallowed hard, while his shoulders drooped in dejection, but only for an instant. He quickly recovered himself, squared his jaw, and drawing himself up to his full height turned towards the door. As he did so he almost collided with a tall, dark, distinguished-looking man wearing a high beaver hat and a dark-blue coat, of semi-military cut, adorned with brass buttons.

"I'm sorry, sir," apologised the lad as he passed out of the building.

"Who is he?" asked the man. "What name did he give?"

"Neil Alexander, yer Excellency," answered the postmaster.

"'Alexander,'" murmured the other reflectively, "'Alexander.' I wonder if he's a relation of Duncan Alexander."

The boy did not proceed far after leaving the post-office. He was worried, for he had expected a letter, and not having received it he was at a loss what to do, and he halted to consider his immediate course of action.

"What is troubling you, Mr. Alexander?" It was the man in the blue coat. "Is there anything I can do for you?"

"I—I—don't know," hesitated the boy.

"It's all right," interposed the man in a kindly tone, "my name is James Douglas——"

"Then you're the——"

"Yes, I'm the Governor of Vancouver's Island. I hope you can trust me."

"Oh, it's not that, sir," exclaimed the boy. "You see, I expected to get a letter from my uncle and I don't know what to do. I thought he was living here, but a man told me he's away up in the North now, so I thought there would be a letter, but there is none."

"Your uncle is Duncan Alexander?"

"Yes, do you know him?"

The governor smiled. "Very well. I sent him to Fort Simpson two months ago."

"Then he could not have got my letter telling him I was coming!"

"It's not likely."

"Well, I'm in a pickle," laughed the boy mirthlessly.

"Why?"

"I came here expecting to meet him, and he don't even know I'm in the country, and he's hundreds of miles away."

"You had better come with me," advised the governor, and together they entered the fort and walked its length to one of the buildings which evidently served as an office-building.

"But how does it come that you are here?" asked the man as they walked. "You're only a boy—what? sixteen?"

"Not quite."

"I would have judged you to be. I was only sixteen when I entered the fur trade—nearly forty years ago. But have you come to apply for a post?"

"I don't know what I want to do," replied the boy. "You see, sir, I landed a little while ago to find my uncle. My father, who came out to San Francisco to teach at a school, was killed there about three months ago. He was shot on the street by a gunman. Two of them were having a fight and one shot. He missed the man he was trying to kill and hit my father. Before he died he told me to come up here to my uncle. I wrote to him and thought he would be at this place or would write me telling me what to do."

"Where's your mother?"

"She died before we left Scotland—when I was a baby."

"Well," observed Governor Douglas after a pause, "we will have to look after you until Duncan can get in touch with you. Come in," he added, and Neil followed him into a plainly furnished office.

A square-shouldered, grey-bearded man was seated at a desk.

"Meet Chief Trader Finlayson, Mr. Alexander."

"Pleased to meet you," and the big fur-trader grasped the boy's hand with a grip that made him wince.

The governor, who was also chief factor in charge of the operations of the Hudson's Bay Company, west of the Rocky Mountains, was soon deep in his correspondence, stopping his reading now and then to comment on some item of business, or to exclaim at some interesting passage he found in his letters. Apparently Neil was forgotten by both men.

"Huhm! Listen. Roderick; listen to what Ogilvy says: 'I hear the Russians from Sitka are offering otters here, and are bargaining with Eickoff and Witzell to supply black foxes at low terms!' Scoundrels, Finlayson; rascals they are, huhm!

"Indeed! Well, well.—Listen—'A schooner left here with potatoes for Owyhee in the Sandwich Islands. Better watch out for your trade from Fort Langley to there!' We must watch our interests there, Finlayson."

"Aye."

"Huhm!" he ejaculated, looking up from another letter. "Rae writes that San Francisco is all excited over the gold finds in the Couteau district on Fraser's River. Thousands are coming as soon as they can find transportation, he says."

"Yes," replied the chief trader, "it's true. More than three hundred came on the Commodore last night. They're at Esquimalt now, trying to get the captain to go over to the river, but he won't chance his boat there. I was over to Esquimalt this morning and I'm afraid we'll have them all here, for they're gold mad. What we'll do with three hundred men about here is beyond me. I don't like it."

"You came by the Commodore?" the governor asked Neil.

"Yes."

"And was there much excitement when you left?"

"Yes. Nothing else was being talked about. Everyone wanted to come with us. The sailors had to fight to keep them from trying to get aboard. Everyone there says Fraser's River is filled with gold sands, and that there's more in the Couteau country than in all California. Other boats were getting ready to come after us."

"I don't like it, Finlayson. They're a lawless lot, those Californian miners—at least a large number of them—for they had to organise vigilance committees to hang the worst of them. There's going to be no lynch law in this part of the world, not in British territory."

"What's best to be done?" asked Finlayson. "As governor of the nearest colony to Fraser's River you'll have to act."

"Yes, I'll have to take charge and see that the laws of Britain are enforced. I don't like it, but it's my duty. I'll have to call the council at once to decide what steps to take."

"It's bad business," commented the chief trader, "bad business," and he shook his head. "It'll disturb trade and excite the Indians. They'll forget fur and start looking for gold. It's a bad business."

"Well, Mr. Alexander," interjected the governor, "you'll take up your quarters for the time being here in the fort, and will eat at the hall. Where's your things?"

"My box is down at the water's edge. It was brought over in the ship's boat that I came in from Esquimalt."

"I'll have it brought up," offered the chief trader.

"We will see you at dinner-time," said Douglas, and, thus dismissed, Neil went out to wander about the fort.

The trading-post consisted of a stockade of poles eighteen or twenty feet in height, enclosing a piece of ground about one hundred yards square. At opposite angles great bastions of hewn timbers guarded the four sides. From the port-holes cannon frowned threateningly in the direction of the water and the Indian village opposite.

Within the enclosure were five storehouses, a blacksmith's shop, dining-hall and chapel, carpenters' shop, a house where the regular employees resided and a cottage for the officer in charge, quarters where visitors were lodged, and one or two warehouses. In the square formed by the arrangement of the houses and shops was a huge tower in which hung a bell, which was used to announce meals, call the inhabitants to chapel, toll during funeral services and celebrate weddings, as well as to give alarm in case of fire or threatened attack. Each stroke of the clapper was the signal for scores of dogs to start barking a hideous accompaniment.

Without the walls of the fort were a few scattered buildings, the most imposing of which was the residence of the Governor. The chief trader resided within the stockade.

Across the harbour was an Indian village of low, flat-roofed, rudely constructed huts. On the beach in front of these shacks a number of canoes, with high, carved prows, were pulled up beyond the tide-line. Even at the distance Neil could make out numbers of men and women moving about the place, their gaily coloured blankets showing brightly against the dull grey of the weather-beaten buildings and the dun-coloured rocks fringing the dark green of the forest.

Several natives were lounging about the main gate of the fort, and he was surprised to find them so different from the Indians he had imagined. Instead of being tall, copper-coloured savages, clothed in fringed buckskin, and wearing gaudy feathers in their hair, he discovered them to be short, broad-shouldered people, with wide, flat faces, who apparently wore little else than a trading blanket for clothing. They appeared to be a listless crowd, moving slowly and with a waddling motion when they walked. One peculiarity he noted. The heads of some were of extraordinary height. He commented on it to one of the men who had engaged him in conversation.

"They be flat-heads," the man said. "They does that themselves."

"Go on, I'm not that green," answered Neil.

"But they does. When a baby is born the squaws binds a board on the young 'un's head and it stays there till he's quite a size. That's their style o' beauty. White women have another style; they squeezes their waists an' wear hoops. It's all in what yuh like, an' they like 'em that way."

Neil did not see the governor or chief trader again until the pealing of the bell announced the evening meal. On entering the hall he was assigned to a seat at a long table over which Governor Douglas presided.

The governor seldom ate in the dining-hall, although formerly it had been his custom to preside at every meal, Neil's neighbour whispered. In the absence of Chief Factor Work, however, he occupied the seat at the head of the table.

"He's a fine old codger, is the gov'ner," his companion volunteered in a low tone as he told Neil of the occupations and importance of the different men about the board. "But he's a stickler on some things. He likes to be called 'Excellency,' an' have everyone speak polite-like. Y' see he thinks it's good fer the young fellahs like me t' learn things that'll be kinda eddicatin' to us, an' so he allus starts talkin' about somethin' or other that'll sort o' improve our minds. Besides he's right in makin' everyone pay respect t' him," he added, "fer if the whites don't, then he'll not get far in makin' th' Injuns do it."

During the meal the governor led the conversation, the others following his lead. A wide range of subjects were introduced and discussed, some bearing on the fur trade, while others were not even remotely concerned with the business of the establishment. Towards the end of the dinner some person mentioned the recent gold discovery on Fraser's River.

The governor turned towards Neil, saying, "Mr. Alexander came north on the Commodore. He tells me that there's great excitement in California over it. I did not think we would start a stampede when we sent the few ounces of gold we got from the Indians to the mint there, but apparently we did."

Neil blushed at the reference to himself and was confused to find all eyes were turned in his direction as the governor spoke. He was soon endeavouring to answer all manner of questions on the subject. "How many came on the Commodore?" asked one. "How do they expect to start mining in a country where there's no supplies?" asked another. "Many more coming?" questioned a third.

He was pleased indeed when an interruption diverted attention from him. It was caused by the appearance of a boy of about his own age, not so tall and muscular, but whose well-knit frame and easy carriage marked him as one inured to hardships and a life in the open.

The youth walked to the head of the table, saluted the governor and laid a thick packet of papers before him. "The dispatches, sir."

"How are you, Harry?" asked the governor. "Did you have a good trip?"

"A good trip, and a fast one, your Excellency. I tried to get here in time for supper. I hope I'm not too late."

Governor Douglas smiled. "No, you're just in time, though. Everything all right at Nanaimo?"

"Yes, but they are very busy and so Captain Stuart sent me with the dispatches."

It was not until the dishes had all been cleared away that Neil had an opportunity of meeting the new-comer. His name, he announced when he introduced himself, was Harry Thomas. He appeared to be a bright, frank, good-natured lad and a general favourite with all. Neil took an instant liking for him.

"Where do you come from?" he asked when they were together later in the evening.

"From Nanaimo, or maybe I should say Colville Town—I don't know."

"Where's that?"

"Why, don't you know? It's the place where the coal comes from. The company has a mine there."

"And is there a fort there, like this one?"

"No, just a bastion—but I guess we would keep the Indians busy if they tried any funny work," he added with a touch of bravado. "We'd put up a real fight and, besides, there's cannons in the bastion."

"You brought letters to the governor?"

"Dispatches," corrected Harry. "Yes, I had charge of the express canoe. It's quite a trip—about seventy-five or eighty miles, I reckon. We had no trouble, but sometimes the Cowichans get after the S'nenymoes—those are the Nanaimo Indians—and of course you have to take a chance with them getting nasty. They wouldn't attack a company canoe, if they knew it. They know better than that, but they might do some damage before they found out, especially if it was about dusk. They're a tough bunch, and its only their fear of Mr. Finlayson and the governor that keeps them from attacking the whites. They have done so. Once they joined the Songhees in trying to take Fort Victoria, but Finlayson taught 'em a lesson. There's a fine man for you; he's afraid of nothing and understands all there is to know about Indians."

"Tell me about it, won't you?" asked Neil.

"It was just after the fort was started here. There was a row about the Indians killing some of the company's cattle. When they were asked to pay for them, they got ugly and said the country belonged to them and they'd kill all the animals they wanted to and would kill the white men, too. There was a big bunch of Cowichans here, and old Tzouhalem, their chief, was really at the bottom of all the trouble.

"They started to shoot at the fort—you can see some of the bullets in the pickets yet—and Finlayson wouldn't let anyone fire back at them. They kept potting away all day long and the next day too, and didn't hit anyone.

"Finlayson knew their powder was about used up on the second afternoon, so he stood up on that platform there and called out to them that they were fools. He sent a man out by the back gate before that and told him to get across the harbour and clear all the people out of the houses in the village. The man made a signal when this was done.

"'Don't you know I could kill you all, if I wanted to?' he asked. They only laughed at him.

"'I'll show you,' he said. 'Look at your houses,' and he told the men in the bastion to fire. The Indians had never heard one of the big guns before, and when it roared and flashed fire they thought the world had come to an end. And when they saw one of the huts blown to pieces they started to yell for him to stop. That ended it. They never tried to capture the fort again. Sometimes they do attack and kill a white man, but the governor always gets after them and punishes them. That's the only way to keep them from killing everybody. Every Indian in the country knows that once the governor gets on his trail he'll never rest till he gets him. He never breaks a promise. If he tells an Indian he'll get a reward for doing something, he'll get it. That's what has built up the company."

"I saw some Indians to-day, but they looked to be a harmless lot," Neil said.

"They are—sometimes, but not always. They get excited very easy, and when they are—look out. But whatever you do, don't show the white feather, or they'll make your life miserable."

"Did you see King Freezy?" Harry asked.

"No. Who's he?"

"He's the big tyee, or head man, over there. You'll know him if you see him. He always wears one of the high hats the governor or one of the factors has thrown away, and a long-tailed coat. He never wears boots, though, for his feet are too big. He's a dandy all right. They say he's got a new hat now, a gold-braided cap one of the naval officers gave him. We must try and see him to-morrow."

In the guest-house where he had been quartered, Neil listened to the men swapping yarns about the big open fireplace. These stories he soon saw were largely told for his benefit, and although he realised they were trying to have some fun at his expense he pretended to accept all that was said as the truth.

"Have you seen any finger-nail cats lately?" Harry asked with seeming innocence.

"No, not lately," responded a man whom the others called Ned, "not lately, but I heard tell as how a couple were about here t'other day."

"Funny things they must be," observed Harry. "I'd like to see one, but I'm not anxious to lose my finger-nails."

"I seed one onct," went on Ned. "They're not exac'ly cats—more like bats, they be. It's bein' able t' fly's what makes 'em dangerous. They comes down chimbleys an' through chinks in the walls an' the like.

"They likes the horns o' deer best, but when they can't get that, why, they gets after finger-nails—that's why they're called 'finger-nail cats.'

"I mind up t' Fort McLoughlin once, as how a young fellow wouldn't believe in 'em and wouldn't put pitch on his nails, or wrap 'em up, or anythin', got caught. The cats—there were three o' them—no, I'm wrong, it were only two—came down the chimbley an' ate three o' his finger-nails. It were too bad, it were."

"Where do you get this pitch?" asked Neil, pretending to be alarmed at the prospect.

"In the woods, but I heard tell as candle-grease 'll do," answered Ned.

Neil excused himself a few minutes later and went to the room that had been allotted him. As he closed the door he could hear the suppressed laughter of the group about the fire at what they believed to be the success of their joke.

By the light of a candle he opened his trunk, and after rummaging in its contents for a moment brought out a stout cord. This he attached to the side of his rude bunk about six inches from the floor and made fast the other end to his box, which he slid along the floor to the opposite side of the room. He waited a few moments and then called out, as if in alarm, "The finger-nail cats! Help!"

There came a wild burst of laughter from the common-room, followed by a rush of feet. His door was pulled open and two or three persons, tripping on the cord, pitched headlong into the room.

"Here, what's the matter?" demanded Neil, jumping up from the bed, and as Harry, Ned and another picked themselves up from the floor, he broke into laughter which was echoed by the two men who had been fortunate enough to escape a fall.

"You fell into the trap I set for the finger-nail cats," he said, when at last he could control his mirth, and the victims of the prank sheepishly joined in the merriment at their expense.

"You'll do, youngster," declared Ned. "You're a chechako, but you're game all right."

"You win," said Harry, extending his hand. "Put it there."

"How would you like to go to Nanaimo?" the governor asked Neil when they met the following morning. "You see, I feel personally responsible for you until you can get in touch with your uncle," he added.

"I think it would be fine," responded Neil.

"I might offer you an apprenticeship in the service," went on Governor Douglas, "but that might not suit either you or your uncle. In any event, I think the best place for you in the meantime is Nanaimo. Captain Stuart can always find something for you to do, and that'll keep you out of mischief. Besides, if this gold rush continues, Fort Victoria will be pretty crowded."

"Thank you, sir."

"The express will leave to-morrow morning. Harry will see that you get there safe and sound," concluded the governor as he moved away.

Harry Thomas was delighted when, a few minutes later, Neil told him that he was to accompany him on his return journey.

"Dandy! That's great!" he exclaimed. "Say, we'll have some fun, won't we?"

They were standing just outside of the fort gate, overlooking the bay. Across the water there was considerable activity about the Indian huts. This was repeated farther along the shore-line where a visiting tribe was encamped. The boys watched the scene for some moments without speaking, then Harry exclaimed, "By Jove, the Songhees are up to something. I think they're going to potlatch."

"What's that?"

"Oh, it's a way they have of giving away blankets and things. They're foolish, I think, but some of the men say that it's the way they bank. When a chief gets a whole lot of blankets he calls his friends and divides them up. Then after a long while they give him all his blankets back and pay him interest—so he doesn't lose anything by it. They have great times at these potlatches, and any old thing is an excuse for holding one.

"Yes, siree, there's something in the wind. Let's go over and see what's doing."

"Will it be all right?"

"Surely; I know old King Freezy—come on," and he started down the trail to the water at a run. Neil followed.

Harry launched a small canoe which had been hollowed from a single log. "You'd better sit still and I'll do the paddling," he cautioned, as Neil stepped into the little craft. Taking up a paddle he sent the canoe skimming over the smooth waters of the harbour.

"Look, there's more Indians coming from that camp over there," and Neil pointed to half a dozen large canoes which were headed for the Songhee village.

"Haidas," responded Harry.

"Who are they?"

"They come from Queen Charlotte Islands, four or five hundred miles up the coast. They're holy terrors; great fighters and have all the other Indians scared of them. They make the other tribes pay them or they'll attack them and kill the braves and make slaves out of the women and children."

"And don't the others ever fight back?"

"Yes. None of the Indians are cowards when it comes to fighting—it's the best thing they do; but the Haidas have the biggest canoes on the coast and are able to put up a better scrap. Just look at the size of those canoes," and he pointed to the Northerners' craft. "See how much longer they are than the ones on the beach."

The Haidas landed before the boys' canoe grounded on the pebbled shore, and they could easily distinguish King Freezy among his people as they advanced to greet their visitors.

"Look at the old boy," Harry said. "What did I tell you about his high hat and long-tailed coat? Don't he fancy himself?"

As the lads walked up the slope towards the large central building Neil had time to look about him, and was surprised to see so many dogs about the place. Some were of a yellowish, woolly breed, unknown to him; others were nondescript curs, some of which snapped and snarled at them as they made their way through the beached canoes, old fish-boxes and other accumulations. The men and women paid but little attention to the boys, but some of the children eyed them curiously.

King Freezy presently emerged from the ceremonial house, and Neil with difficulty restrained his laughter when he saw that the chief's great top-hat was now surmounted by a discarded naval cap, gleaming with golden lace. Both were secured by a bright red strip of cloth which tied beneath his chin.

The chief's face expressed pleasure at the sight of Harry, who greeted him in the Chinook jargon, the language invented by the fur-traders and adopted by the Indians for the purposes of barter in the North-West.

"We're lucky," Harry explained. "It's going to be a grease feast."

The boys were conducted with some ceremony into the house and were given seats close to King Freezy himself.

"Don't laugh, whatever you do," Harry whispered as they entered. "It's all very solemn with them."

A fire was burning on the earthen floor of the big building and the smoke curled up towards a hole in the roof. Not all of it escaped through the opening, and the immense room was filled with a haze that made the boys' eyes smart and burn until they became accustomed to it. Long benches were constructed on platforms about four inches from the ground, along the walls of the building. For the most part these were already occupied by half-naked savages, many of whom had their faces bedaubed with paint. Some of the women had bone ornaments thrust through the flesh of their lower lips. Nearly all held short sticks, not a few of which were curiously carved.

Scarcely had the boys taken their seats when a hideous form bounded to the centre of the floor. It was a man, naked save for a short apron, and wearing a huge mask to represent some fanciful beast. It was painted in livid colours. He started to dance about the fire, and as he turned and twisted he screamed and shouted at the top of his voice. The natives began to beat with their sticks on the boards of the benches and chant a weird refrain. The whole thing was so grotesque and so barbarous that Neil was startled at the scene. He looked at Harry in some alarm and was reassured when he saw that his companion was viewing the ceremony without any display of nervousness.

A HIDEOUS FORM BOUNDED TO THE CENTRE OF THE FLOOR

The din attracted others to the place and soon all the seats were occupied.

When the dancer disappeared Harry looked around the building and an expression of anxiety crossed his face.

"What's the matter?" Neil asked.

"I don't like this very well," was the whispered answer. "The Haidas are all sitting together, close to the door, and there are no squaws among them. It don't look good."

"What can we do?"

"Nothing; just sit still. We can't leave now. It 'd be an insult. Keep quiet, that's all."

"All right," answered Neil, "I'll stick by you and do whatever you do."

"Fine! Now they're going to start again. Wonder what it'll be this time."

The racket started once more, only this time it was worse. Half a dozen masked figures were dancing about the fire in imitation of the animals they were supposed to represent. One huge fellow wearing a head-dress carved to resemble a bear was swaying uncertainly as does Bruin when he attempts to walk on his hindpaws; another was jumping in imitation of a deer, while still another sought to depict the rising, blowing and sounding of a whale—and so it was that each actor in the strange play strove to give a realistic portrayal of his guardian animal spirit. More dancers joined the throng, their jumping, twisting, gyrating bodies and ugly masks bobbing up and down, now in the shadow as they came between the boys and the blaze, and now in the red reflection of the fire as they circled the burning pile.

Neil was startled at first, but he soon overcame his awe, and after he had watched the dancers for a time he leaned over and shouted in Harry's ear, "Don't it look like hell?"

"Never been there," was the answer.

The Haidas took no part in the singing or beating time, and the lads could see by the angry glances in the direction of their Northern guests that the Songhees did not relish the aloofness of the visitors. It was evident by the sneer on the face of the Haida chief that it was his intention to provoke his hosts.

When the dance ended a Songhee chief stepped to the centre of the hall and started to harangue the people. An interpreter translated his words to the Haida tongue.

"Who is he?" Neil asked, motioning towards the orator.

"He's King Freezy's speaker, I think. He's probably telling the world what a fine fellow the king is—or thinks he is."

King Freezy was sitting directly in front of the boys, and he now rose and walked forward. He started to speak in a slow, moderate tone, and from his gestures it was evident that he was bidding the Haidas welcome.

Hardly had he concluded than the Haida leader rose and made reply. As his speech was translated the faces of the Songhees darkened and their eyes blazed. Some insult had been given and men and women muttered angrily. More than one native reached for his knife, but King Freezy quietened them with a wave of his hand.

Advancing he once more addressed the people, his fiery eloquence and snapping black eyes conveying clearly the purport of his words. He was hurling a challenge of some sort at the Haida chief. He concluded with a sharp order. A dozen men sprang to obey.

The boys thought there would be an open outbreak, but instead the Songhees rushed towards the fire with cedar boxes and started throwing oolichan grease on the fire. The flames shot up as if by magic, but still the wild figures continued to feed the blaze. All the while Indians shouted, beat with their sticks and swayed to and fro.

Higher and higher leapt the flames until they were licking the huge logs that served as crossbeams. The faces of the savages glowed red, and the heat was almost unbearable—but still more grease was thrown on the fire.

King Freezy alone sat still, with folded arms. He it was who had ordered this destruction of fish fat, the highly prized food of the Coast Indians, and the more that was consumed, the greater was he in the estimation of his own people and the more powerful had he proved himself over his ancient enemies who were now his guests. It mattered not if the whole tribe was made poor by the extravagance, it must go on, and no one would complain.

When the flames were at their height and charring the beams above, King Freezy stood up and shouted an order. Young men disappeared to return almost immediately carrying blankets. Rushing up to the fire they threw them into the roaring flames. They vanished again and returned carrying one of the largest canoes of the village. King Freezy, seizing an axe, walked to where the canoe had been set down, and deliberately started to chop it to pieces. Willing hands seized the splintered wood as it was hewn from the craft. This was added to the blaze.

Another canoe was brought and chopped to pieces; more blankets and more boxes of grease were carried in by perspiring savages as further sacrifice to the flames. The heat was terrific. The boys could hardly bear it although they were at some distance from the actual fire.

"He's trying to drive the Haidas out," Harry shouted. This was the case, and Neil noticed that as the Songhees added fuel to the blaze they did so in such a manner that the burning area gradually extended towards the visitors. Not a Haida showed the least discomfiture. They only drew their blankets tighter about themselves as if suffering from the cold.

"Look!" Neil exclaimed, pointing through the wreathing smoke to where the Haida chief had arisen. The Northerner leisurely approached the roaring furnace until the heat must have blistered his flesh, and deliberately spat into the centre of the fire. He did so with such an air of contempt that it was easy to interpret his action: he was making clear to King Freezy how little he thought of any fire that the Songhees could kindle.

So intent were all upon the performance that no notice was taken of the stealthy approach of a Haida warrior who had gained admittance through a hole in the wall and had crept along below the seats.

Suddenly the naked savage rose beside Neil. His appearance was so unexpected and startling that, for a second, both boys were unable to grasp his purpose. Then his arm lifted and they saw a long blade. As he leaned slightly forward to plunge the weapon into the back of King Freezy, Neil half rose and swung for his chin with all the strength he could muster. Harry threw himself forward upon the shoulders of the Songhee chief, bearing him to the ground.

Neil's blow landed fairly, and the big Indian staggered back, his knife flying into the air to fall harmlessly to the floor.

The Haida recovered quickly and drew a second knife. His eyes blazed with fury as he made a lunge at the white boy. Neil stepped aside and the blade buried its point in the wood of the seat where he had been sitting.

The action was so swift and unlooked-for that the Songhees were unable to grasp its purport for a second or two. Then all was in an uproar. A dozen braves leapt at the stranger, their knives flashing in the light of the fire, but quick as they were they missed him. He dropped beneath the bench and, worming his way along the wall at an incredible speed, found the hole by which he had entered, and disappeared.

King Freezy picked himself up just in time to see the Haida's futile effort to kill Neil. He shouted to his people to seize the would-be assassin and himself jumped towards the place as the man disappeared.

Such was the confusion that all eyes were turned in the direction of the chief, and Indians came crowding from all quarters. Pandemonium reigned. It was several minutes before the chief could make himself heard above the shouting and yelling of his wild followers. He called for them to rush the Haida party.

It was too late. The visitors were not there. Every one of them had disappeared. Immediately the attempt was made on the life of the chief, the Haidas, taking advantage of the turmoil in the lower end of the hall, had slipped out of the door near which they had been seated, and were well on their way to their canoes before their absence was noted.

The Songhees piled, pell-mell, out of the potlatch house in pursuit, but before they could reach their canoes their enemies were some distance from the shore.

The boys did not join in the general rush from the building and soon found themselves alone. They stood looking at each other for a moment, then Harry whistled softly, ending with, "Whew! that was a close one."

"It was."

"Say, you're all right. I thought at first you were going to be scared, but I think you've got more nerve than me."

"Go on," said Neil, "I was scared—awfully scared, but there was nothing else to do. You did the right thing in pushing Freezy out of the way."

"Well, we'll not quarrel about it. The best thing we can do is to get out of here—and quick, too."

"I'm going to take this," said Neil, and he picked up the knife the Indian had aimed at him.

Outside all was excitement. King Freezy and several other chiefs were haranguing the people. Every man was armed and there was every evidence that retaliation was being planned.

The boys were not interfered with as they ran out their canoe. They paddled along the shore for some distance before crossing to the other side to return to the fort.

Here they found considerable excitement. The cause of the trouble among the Indians had been suspected as soon as the Haidas were seen to rush from the ceremonial hall for their canoes, and a man had been sent off on horseback to Esquimalt. Two hours later a gunboat steamed into the harbour and anchored off the Haida encampment. The big guns of the vessel were arguments in the cause of peace that the natives of the Coast well understood.

It was late in the afternoon when a man met the boys and informed them that the chief trader wished to see them.

"I guess we're in for it," muttered Harry.

"Why? We didn't do anything."

"But can we make anyone believe it? There was trouble and we were there. That's enough."

On entering the office they were surprised to see King Freezy and two Indian girls with the chief trader.

There was a twinkle in the eyes of Mr. Finlayson that set Harry's mind at rest as to the manner in which their adventure would be regarded.

"I hear you distinguished yourselves this morning," he said. "And now you are to be rewarded. King Freezy here," and he nodded towards the smiling chief, "tells me you saved his life."

"It was nothing, sir," stammered Harry.

"Well, he thinks so. I'll hear your story later. He wants to reward you for your services, and has brought you a present of a klootchman each."

Harry's eyes almost started from their sockets and his jaw dropped.

Neil looked at his friend in astonishment. "He's brought us what?" he asked.

"A klootchman," gasped Harry—"a—squaw—a girl. He's giving us each a wife."

"But I say—I—I don't want a wife," exclaimed Neil in consternation.

"Nor me."

"But do we have to take them?" asked Neil, who was first to recover. "Do we really? It's awfully good of him and all that, but I don't want a wife."

"I'll see if I can fix it for you, but I doubt it," replied the chief trader. "You lads had better leave it to me."

He spoke to King Freezy in the native language and motioned for the boys to go, which they did without waiting for a second suggestion.

"Well, this is a nice pickle," murmured Harry when they were outside. "You're making progress, you are, Neil. You only landed yesterday, and now you're established with a princess for a wife."

"How about yourself?"

"Uhm, that's so," and Harry scratched his head in perplexity.

Neil started to laugh and his companion looked at him in amazement. "What's funny? Tell me the joke, for I don't see it."

"Oh, I was just thinking that I'll have the best of it."

"Why?"

"Well, you see, she can't talk to me, and I can't talk to her, but your wife can jaw you in Chinook, and you'll have to listen."

"Has anyone seen the chaplain?" asked Mr. Finlayson in the hall that evening. "Have you seen him—yet, Harry?"

Both boys blushed, and the men present were quick to see and appreciate that the chief trader was having a quiet joke at their expense.

"Who is she, Harry?" asked one. "When is it to take place?" questioned a second. "What'll the girls at Colville Town say?" demanded a third.

"Go on with you," protested Harry, blushing still more. "I don't know what you mean." And then in order to rid himself of his tormentors, "Maybe it's Neil, here, you mean."

"Perhaps it is me," agreed Neil, not minding the banter of the men. "Only I don't know her name. If some of you fellows will teach me Chinook, I may be able to find out."

While Neil was replying to the jesters, Mr. Finlayson motioned to Harry. "I've fixed it all right," he told the boy. "At first the chief could not understand why you did not want his gift, but I told him that neither one of you could hunt or fish enough to keep yourself, let alone a wife. Besides, you were not rich enough to give a potlatch."

"Thank you, sir," answered Harry with a sigh of relief.

The boys retired early and were soon asleep. Indeed Neil could hardly believe that he had been sleeping for some hours when he was aroused by Harry who exclaimed, "Come on. It's time for us to be moving."

The dispatches had been prepared the previous night and everything was in readiness for an early start. Final preparations were soon made and, just as grey dawn was streaking the eastern sky, the lads, with two S'nenymoes bearing Neil's box, filed past the sentry at the fort gate and made their way down to the waiting express canoe.

The lads seated themselves on cedar mats near the stern, directly in front of the steersman, who answered to the name of Titus. The word was given, the paddles were lifted and fell with a single splash, digging deep into the water, and with a quick start the big canoe bounded away.

It was cold and chilly on the water, and as they sat with blankets drawn tightly about them, the boys said but little. Swiftly the canoe passed down the bay and out into the Straits of Juan de Fuca. The rolling and tossing of the craft as the early morning breeze churned the sea into dancing waves made Neil fear he would be sea-sick, but he soon overcame the dread as he became more accustomed to the motions of the dug-out.

As they skirted the shore, turning gradually eastwards, the day began to brighten, uncovering distant islands, while nearer bare rocky islets, against which the waves broke in spray, showed above the water.

"I'm not used to being up so early," Neil yawned. "Do you always start on trips as early as this?"

"Yes, to get all the daylight there is."

"Well, it may be all right for you fellows who were born here, but it's going to take me some time to get used to it."

"I wasn't born here," answered Harry. "I've only been here a little more than two years."

"Is that so?" And then after a pause, "Is your father in the company's service?"

"No," answered Harry gravely. "I don't know where my father is, or whether he's alive."

"What happened?"

"You see, my dad was owner and captain of a ship, the Goliath. He took me with him on a trip after my mother died. When we were at Panama dad was taken with fever and they landed him and Dr. Goodson, a friend of ours who was with us.

"They wouldn't let me land. The ship had to come up here with a cargo of stuff for Victoria. We were to call at Panama on our way back and pick them up.

"Jobsen, the mate, was a rascal, but he was a good sailor. I never liked him. He was in charge after dad went ashore. He was very nice to me, though, and especially after we got to Esquimalt where we unloaded.

"The night before we were to sail he asked me to go ashore with him. It was just about dark. He asked me to wait for him while he went to see about something. Suddenly something was thrown over my head, and I was picked up. I tried to yell, but couldn't. I was put in a canoe or boat and was taken a long way. I didn't know where I was going, but I knew that the Indians had me. After a while the canoe stopped. I was picked up again and carried into the woods. Then I was made to walk, and the sack was taken from my head. An Indian walked on each side of me, and they made signs that if I made a noise they'd kill me. I was too scared to yell if I wanted to.

"They kept me prisoner for three or four days. Then old King Freezy came along with some of his men. They made the other Indians give me to them, and they took me to the fort."

"And what happened to Jobsen?"

"He was drowned. The Goliath waited round for a day or two, and he reported that I was lost. Then he sailed away. I think he was trying to get hold of the ship. He thought that dad was done for, and if he could get rid of me, then he'd do what he wanted with the ship. Anyway he didn't get very far, for the Goliath was wrecked off Barkley Sound. At least pieces of her floated ashore and were brought down by Indians. I guess everyone was lost."

"And you never heard anything of your father?"

"No. I wrote to Panama, but received no answer. Then the governor sent me to Nanaimo to make myself useful—and I've been there ever since."

"We seem to be in about the same fix, don't we?" exclaimed Neil after a brief silence, and he told Harry his story as he had related it to the governor, but in greater detail.

All the morning the Indians kept on, paddling steadily, their blades rising and falling to the time of a chant. Neil marvelled at the endurance of the men. The canoe wound in and out among great islands, wooded to the water's edge, or showing high bluffs of grey limestone or granite.

They stopped at noon and drew the canoe a little way up the shingle of a cove into which a tiny stream emptied.

"Titus says we mustn't make a fire," Harry said. "There may be some Cowichans about, and he's not sure how they'll act. There's been some trouble between the tribes lately."

"The Cowichans are the Indians you were telling me about—the ones that helped the Songhees attack Fort Victoria?"

"Yes. This is their country. The S'nenymoes are related to them, but they're always fighting among themselves over something or other. Sometimes, though, they join to fight the Northern Indians.

"Once there was a great battle fought among these islands. The Cowichans, so I have been told, were away fighting some tribe down in Puget's Sound. The Northern Indians came down and attacked the Cowichans' villages. They killed the old men and took the women and children away as slaves.

"When the Cowichans came back they found their homes in ruins and their families gone. One old man had escaped to the woods and he told them all about it. From a Songhee they learned that the Northerners were coming back. So the Cowichans sent out to all their friends. They have relations over at the mouth of Fraser's River, and they got them and the Squamish and the S'nenymoes and all the other tribes who were afraid of the people from the North, to help them.

"They put sentries along the coast, and then one day they got a signal that the enemy was coming. All the Cowichans and their friends hid behind the islands, and when the enemy arrived, expecting to take them by surprise, they found the villages just as they had been left. They landed from their canoes, little suspecting the ambush prepared by the Cowichans.

"Then a canoe was seen with three or four women in it, and two or three of the Northern canoes started off after it, but the women paddled away and more canoes started off. By and by there was a whole string of canoes chasing the first canoe which headed through between two islands. The Cowichans were in hiding, and after a number of the Northern canoes had passed through they came out and cut the line in two. There was a terrible fight.

"Then the rest of the Northern canoes came up—there were three hundred canoes altogether—and there must have been a couple of hundred Cowichan, Squamish and S'nenymo canoes. The fight lasted for three days, and the Cowichans killed nearly all the Northerners. Some tried to escape, but they were chased as far up as Comox and killed. The women and children were found near Comox.

"I guess there must have been three or four thousand Indians killed in that fight. It is supposed to be one of the biggest fights ever known on the Coast. The man who told me about it, said it happened a long time ago."

The Indians having rested, the journey was resumed. The canoe now kept close to the shoreline of the islands, taking advantage of the shadows of the trees.

It was towards evening when Titus, who had been looking behind every few moments, uttered an exclamation and gave a sharp order. As the paddle-men bent to their task the canoe seemed to fly through the water. The boys looked back and in the distance they could discern a tiny speck, which Titus said was a canoe in pursuit of them.

"I reckon we're in for it," said Harry. "If it was full daylight they probably wouldn't attack us, but it'll be dark by the time they overtake us, and they won't be able to see it's a Company canoe. Have you got a revolver?"

"No, all I've got is the Haida's dagger," answered Neil.

Harry produced a large Colt revolver and powder-horn and commenced carefully to load two of the six chambers that were empty. He drew off the percussion-caps, inspected the nipples of the weapon and replaced them.

"They're gaining," said Neil. "How long can we keep up this speed?"

"I don't know, but Titus is going to dodge between some islands and try and lose them. We'll probably land somewhere. That'll give us a better chance."

Neil was silent for a few moments, his brows puckered in thought. Finally he asked, "Do these Indians believe in spirits?"

Harry appeared to be annoyed at the frivolous nature of the question under circumstances of such peril. He did not answer until Neil had repeated it. Then he snapped, "Yes, but never mind that now."

Producing a key, Neil reached forward and unlocked and lifted the cover of his box. He groped about in its contents for a moment, and then, with a grunt of satisfaction, drew out a piece of candle and a stout fishing-line. Picking up an Indian basket from the bottom of the canoe, without a word of explanation he set to work with his knife cutting holes in the bottom of it.

Harry paid no attention to him, but from time to time spoke in low-toned Chinook to Titus, who grunted replies. The quick breathing of the canoe-men and the phosphorescent glow as their paddles struck the water told of their exertions.

"It's pretty dark now," observed Harry at last. "I think we'll give them the slip for a while anyway. It'll give us a chance to land some place, and put up a better fight if we have to."

Neil did not answer. He was again busy exploring in his box, searching for something which at last he found.

"What's that you've got?" asked Harry.

"A flute."

"A flute! Have you gone crazy? You're not going to play that!"

"Not just now, anyway."

Nothing further was said for some time. The canoe turned and twisted in and out of narrow, dark passages that separated small islands. At last Titus gave a whispered command and the other Indians stopped their paddling. The canoe glided noiselessly onwards for some distance, while every ear was strained to catch the sound of pursuit.

Hearing nothing, the paddles were again dipped gently and the canoe was run ashore in a small crescent-shaped bay.

"Which way will they come?" Neil whispered after they had landed.

"Right into the bay; why?"

"How long will it take for them to find us?"

"Maybe half an hour, maybe an hour or more, I don't know. Perhaps we've given them the slip altogether," answered Harry. "The moon will be up in a little while, and that'll help them."

"What are you going to do?" asked Neil.

"Well, I've been talking it over with Titus and I think the best thing is for us to split up. There's nine of us. If three take one side of the bay, and three the other, and we stay with Titus here, we'll be able to get them between our fire. Titus thinks there's nine of them, so we're about even."

"But you'd rather not fight, wouldn't you?"

"Certainly, but I guess we'll have to."

"I don't know; I've been thinking maybe we won't have to," answered Neil, and he whispered the details of his plan.

"By thunder! I believe you're right," exclaimed Harry. "It might work. I'll tell Titus, so he can let the others know. If they don't expect it, they'll be as scared as the Cowichans." He crept over to the headman who was sitting with his canoe-men, and whispered to him. It took considerable persuasion to make the Indians agree to the proposal, but finally they signified their willingness and, after some further discussion among themselves, silently stole away to take up their positions.

"Well, I guess we'd better get ahead with it," suggested Harry. Gathering up the fishing-line, basket and flute, Neil turned to a nearby tree. Harry followed. With some difficulty the boys climbed up into the branches, keeping close to the trunk on the land side.

It took them the better part of half an hour to adjust things to their satisfaction.

"I hate to leave you alone up here," said Harry when they had finished their work. "It will be tough on you if it don't work."

"That's all right," said Neil, and his companion descended.

It was cold up the tree, and Neil was glad of the additional comfort afforded by Harry's coat which his chum had insisted on leaving with him.

It seemed that hours must have passed when Neil, in his cramped position, heard the call of a night bird. It was the signal agreed upon as a warning of the approach of the Cowichans.

Doffing his coat and using it as a shield, he produced the fire-bag Harry had left with him, and after one or two attempts he succeeded in lighting the candle. This he transferred to the basket which had been lashed between two limbs facing the bay, and which was covered with his own coat. He succeeded in doing it without a gleam of light escaping.

Below, Harry and Titus prepared to give battle.

Not many minutes elapsed before the noise of dipping paddles and the scraping of the handles of the paddles against the sides of the canoe could be faintly distinguished. On shore there was not a sound. Neil hardly dared to breathe and feared that the pounding of his heart must surely be heard.

The nose of the big dug-out showed around the point, as the craft glided into the path of the moonlight. Right across the mouth of the bay the Cowichans passed. It seemed as if they had missed their quarry, but presently they turned and crept stealthily into the cove.

Now they had passed the place where the S'nenymoes were concealed on either shore. Neil listened, every nerve tensed. A twig snapped. It was the signal.

Whipping the coat off the basket, he gave voice to a most blood-curdling yell, and springing back to the fork in the branches he seized his flute and, placing it to his lips and blowing with all his might, he produced a most hideous and weird screeching.

The Cowichans stopped, looked towards the tree and saw a ghostly face grinning at them from among the branches. Terror seized them. Turning their canoe about as quickly as possible, they made a dash for the mouth of the bay. Only one shot was fired by the startled savages, the ball burying itself in the trunk of the tree behind which Neil was sheltering.

It was not until they were half-way out of the cove that Titus fired. Almost at the same instant the sharp "crack" of Harry's revolver sounded. Then from both sides of the bay muskets flashed. One Cowichan was seen to suddenly rise to his feet and pitch forward out of the canoe. Another crumpled and dropped, while cries of pain told that other shots had taken effect. Above the noise of the conflict, the cries of the wounded and the exultant shouting of the S'nenymoes, the high screeching and wailing of Neil's flute could be heard.

When, at last, the surviving Cowichans made good their escape, Titus called his braves back, and Harry, going to the foot of the tree, called delightedly, "Come down, you old war-horse; come down." It was several minutes, however, before he could attract Neil's attention, who was still manufacturing ghastly noises with the aid of his flute.

"We'd better be moving," Harry said when they were together again. "There may be other Indians about, and it's certain that those who have escaped will bring back more later."

In a few moments the canoe was launched and they were on their way again, the joyous S'nenymoes paddling with renewed vigour, anxious to arrive home to tell how they had defended the company's property and to claim reward for their service.

"We owe it all to you, old man," said Harry with just a trace of huskiness in his voice. "I don't know what we'd have done without you and your lamp and flute. I wouldn't have thought of a scheme like that in a hundred years. I don't see how you figured it out."

"It's not exactly original," responded Neil. "I remembered a story I heard of the American Revolution. A couple of boys and a girl started playing a fife and drums when an attack was being made on the village where they lived. The sailors from the British warship thought it was an army band, or something like that, and went away without doing any damage to speak of. They thought a strong body of soldiers were coming. I never thought, though, that this old flute would some day be used in a similar way and save my life."

"It certainly did sound awful," laughed Harry. "I don't blame the Cowichans for being scared. If I didn't know what it was I'd have been frightened myself. But you must play some real music on it when we get to Nanaimo."

"Play real music!" exclaimed Neil. "I can't play a thing on it. It belonged to my father. The only music I can make with it is the kind that you have just heard."

Neil found Nanaimo to be a delightful little place. The settlement was built on a peninsula, which, at times, was almost an island with deep ravines and gullies separating the higher land from the rising forest slopes of the neighbourhood. The mines which were being worked were across one of these ravines, and the miners approached them by way of a bridge that had been recently constructed so as to facilitate the shipment of coal to the loading wharf.

On the highest part of the peninsula stood the defensive works of the establishment in the shape of a single bastion armed with two carronades and loop-holed for muskets. The homes of the miners and regular employees of the Hudson's Bay Company, with the store and other buildings essential to the affairs of the company, were clustered about the little fort with its whitewashed walls of hewn logs. Four streets, or rather, trails, winding in and out between stumps and big boulders, formed the town proper, while a saw-mill operated by water power and a salt-shed where salt was extracted from a brine spring, were a little distance from the other buildings. In the distance, behind the town, rose Mount Wakesiah, while the harbour, on which the village faced, opened between protecting islands to the blue waters of the Gulf of Georgia.

While the establishment and the location of Nanaimo pleased Neil, it was the kindly character of the people that especially delighted him. For the most part the miners were from the colliery districts of England, with a few from other portions of the British Isles, together with three or four French-Canadians and Iroquois Indians who had crossed the continent in the service of the great fur-trading company. Exclusive of Indians, who occupied several villages on the shores of the inlet and numbered between four and five hundred, the total population of the place was less than a hundred and fifty. They all seemed to vie with one another in the cordiality of their welcome to the new-comer.

Neil shared with Harry the room which he occupied at the rear of the Hudson's Bay Company's store and took his meals, for the first week, by invitation of Captain Stuart, at the officers' mess. Later he and Harry ate at the regular dining-hall.

Captain Stuart was a kindly-spoken man who could, however, when necessity required, be stern and enforce his orders by the strength of his will.

"I want to thank you," he said to Neil on the day of the arrival of the party at Nanaimo, after Harry had detailed the story of their voyage. "While Harry and Titus would probably have beaten the rascals, it might have been at some cost. Your scheme probably saved us a heavy loss. I'm going to report your part in the affair to the governor, and I know your conduct will please him greatly."

"It was well done," agreed Dr. Benson, the company physician, who was present when the report was made. "I've always told you, captain, that an ounce of brains is worth a pound of powder."

"You may be right," responded the other, "but still, I like to know that my powder's dry and ready for use if my brain doesn't get me out of a tight place."

The doctor laughed lightly and with a wave of his hand strode away. He was a merry, carefree man, liked by everyone despite his odd manner and disregard for appearances. His usual attire was a pair of old, patched trousers, one leg of which would be enclosed in the top of a high boot, while the other was not. His coat was more often than not fastened on the wrong buttons. Sometimes he wore a stock, but usually he wore neither neckwear nor hat. His skill as a doctor was undoubted despite his manner of administering it.

Later in the day, as Harry and Neil were looking about the little camp, they encountered a miner holding his hand to his face. "What's the matter, Job?" asked Harry.

"Wha's th' maitter!" exclaimed the man. "Yon doucther—th' auld villain—pullit a wee bit tooth, an' he made it hurt waur than need be."

"Surely not!"

"Aye, A'm tellin' ye he did. Whin A went tae see him, Bizzy, his dog, barket at me an' A kicket her. The doc wus keekin' oot an' seed me. When he got me inta his hoose an' pit th' deil's prongs he uses tae pull teeth wi' inta ma mou', he laughet an' said, 'A'll teach ye tae kick Bizzy!' an' he hurted me awfu'." And the miner moved off muttering threats against Bizzy and her master.

Neil found plenty of employment, helping in the store with Harry when required there, or giving a hand at the mill, or again, helping to check the coal as it was loaded when a vessel came for a cargo. There were lots of jobs for him to do, and he undertook them willingly. After the work of the day was done he and Harry walked about the village, or joined with one or two of the younger men in a canoe trip about the harbour.

"The Haidas are coming here on their way from Victoria," Harry said one night two weeks after their arrival. "I guess they sent them home after that trouble with the Songhees. I hope they don't try anything here."

"I wonder if any of them will recognise us," said Neil. "They might be nasty about our saving King Freezy."

"I never thought of that," answered Harry. "I don't suppose any of them would know us again, unless it's that fellow you hit. But we'd better be on our guard anyway."

The Haidas camped near the town and soon made their presence felt. They prowled about the place stealing chickens and anything else that took their fancy. The S'nenymoes were in evident terror of them and did not fraternise with the haughty Northerners, but kept to their own villages.

One afternoon the boys were walking along the trail past the home of a man named Baker. They stopped to pat Baker's dog. Suddenly the dog stopped wagging her tail. The hair on her back bristled and she uttered a low growl. Neil turned quickly to see what had excited the animal. Standing almost behind him was a Haida with a great stone uplifted. Brief as was the glance, he recognised the Indian who had attempted to take the life of the Songhee chief.

"Look out!" he cried and gave Harry a push that sent him sprawling, just as the rock, hurled with all the force the Indian could command, flew past the boy's head. It struck the dog and killed her instantly.

Harry was up in a second and the lads sprang at the savage. They seized him and a desperate struggle followed. The man was strong, and it was all that the boys could do to hang on to him, one on each arm, in their efforts to prevent him reaching the knife they knew he had in his belt.

Backwards and forwards they fought. The Indian struggled madly to free his hands and the boys hung on to the limit of their strength. Suddenly the Haida reached down in an attempt to fasten his teeth in Neil's ear. He narrowly missed his mark, biting the shoulder of the boy's coat and ripping the cloth. Harry drove a tremendous kick against the Indian's shin, almost felling him. The man turned towards him, but Harry was too quick, avoiding the gleaming teeth, while Neil in turn kicked viciously against the savage's other leg.

The outcome of the fight was doubtful. The strength of the boys was weakening, and it seemed as if one or the other must soon lose his hold. To do so, even for an instant, would permit the Haida to reach his knife. Harry's breath was coming in short, sharp gasps, but with gritted teeth he hung on, and Neil felt his fingers slipping, when a shout was heard and three or four men rounded the corner.

The Indian heard their cries and with a tremendous effort managed to throw the lads from him and make his escape.

While the boys were still gasping out their story, Baker arrived on the scene. Great was his indignation when he saw the body of his dog and heard of the murderous attack on the boys.

"Come on," he cried, "let's find Captain Stuart," and he started off at a run, with the others following.

"Bad business. We can't stand that sort of thing," exclaimed the captain when he had been told of the occurrence. "Sound the alarm."

In a moment the big triangle that served as a bell was clanging out its imperative summons. Men dropped their tasks at mine and mill, turned and ran in the direction of the bastion. Women caught up their children and, pale but determined, hastened towards the sound.

Inside the fort muskets were caught up from the racks and the small cannons were moved into position from which they could cover the Haida encampment.

Within half an hour all was in readiness and Captain Stuart sent a party to the Haidas to demand that the culprit should at once be surrendered for trial before him as magistrate. Orders were given that if met by force the little band was to fall back on the bastion without, if possible, engaging in hostilities.

"We'd better show them our strongest weapons first," said the captain as he directed that the carronades should be well loaded with canister.

Harry accompanied the messengers to identify the Indian, if necessary, while Neil stayed at the bastion, making himself useful in quietening the children. The women, accustomed to the dangers that constantly surrounded them, made no outcry. Realising the seriousness of the situation, they made their way without fuss to the big room at the top of the bastion. One or two remained on the gun-room floor, preparing bandages and other necessities for immediate use in case of emergency.

Dr. Benson, whistling and humming to himself, went about his preparations for attending to the wounded. "Here, young fellow," he called to Neil, "I want you to give me a hand. Not afraid of blood, are you? No, that's good. You've got a pretty good head on you, so you stand by in case I want you."

"Do you think there'll be a fight?" asked Neil.

"You never can tell with these Haidas. I don't know them very well. I think the captain's going to try Finlayson's plan, though, and show them what the guns can do, if they don't behave. That'll probably scare them into submission, but you never know."

It did not take long for the little party of white men to reach the Indian camp, and those watching from the bastion could see them parleying with the native chiefs. Then there was a sudden confusion and the Indians could be seen arming themselves with clubs, spears and muskets. Slowly the white men retreated, their faces towards the savages.

"By Jove, they've got grit!" exclaimed the doctor in admiration. "See the leisurely way they're falling back. It's got the Indians puzzled. That's the reason Great Britain's what she is to-day," he added enthusiastically. "No matter who or what they are, Britons are all good fighters at heart."

Beyond throwing a few sticks and stones, the Haidas did not venture to attack, despite the superiority of their numbers. Had the handful of men turned to run, the natives would have been on them in an instant and all would have been butchered.

"All ready with those guns?" It was the quiet voice of Captain Stuart.

"Yes, sir."

"That's right, boys. Now, when our fellows have fallen back another fifty yards, let 'em have it. One at a time. Aim high. We don't want to kill any of them, but we want to show what we can do if we have to."

There was a moment of strained silence. The gun which was to be fired first was sighted and the fuse made ready. All eyes were upon the slowly retreating little party. Now the Indians were beginning to move forward. The shower of stones increased and it was evident the Haidas were preparing for a rush.

"Gunners,—ready—fire!"

There was a flash of fire, a deafening roar, and the building shook with the vibration as the gun sprang back in recoil against the tackle.

"Well placed," commented the captain. "Now the other one."

The second carronade was run out and again belched forth an angry message.

As the smoke cleared after the second shot and the gunners were ramming home another charge, Neil could see how the grape-shot had torn and shattered the tree-trunks and foliage above the Haidas' camp. The Indians stopped their rush at the first shot and were now fleeing in confusion for cover in the forest or behind convenient rocks.

Once more the cannon thundered its warning.

"That will do for now," commanded Captain Stuart. "I think they're properly frightened and will give in."

Neil hurried down to meet his chum as the little band reached the bastion. "I thought we were in for it," Harry declared. "They would have hurt some of us if the cannon had not been fired when it was. I can tell you it was a pleasant sound."

"Well, young fellow, I don't think you're going to get a chance to learn anything about surgery this time," exclaimed the doctor as he slapped Neil on the back. "They see the error of their ways now."

An hour later a small group of Indians approached the settlement, each with his right hand held aloft in token of peace. In the midst of the group stalked the culprit, his head erect, and carrying himself with a haughty dignity that won the admiration of the white men.

They were met by Captain Stuart and three or four of the men, and the Indian was turned over to them. Court was at once convened, and the captain, sitting as a magistrate, heard the witnesses. Both boys gave evidence, as did also Baker and the men who had come to the rescue of the lads.

The Haida chiefs seemed satisfied with the manner in which the proceedings were conducted and offered no objection when the man was found guilty and was sentenced to receive a dozen lashes with the cat-o'-nine-tails.

The savage was taken to the gun-floor of the bastion, where he was lashed to one of the guns. Then the whipping was administered by one of the men, every lash raising huge welts on the skin of his bare back. The Indian never uttered a sound.

The flogging concluded, he was handed over to his friends, who, after listening to a lecture from Captain Stuart on the folly of refusing to surrender the man when asked to do so, were permitted to take him away with them.

A strong guard was maintained about the establishment all night, but there was no disturbance, and when daylight came it was seen that the Haida encampment was deserted and their great canoes had disappeared from the beach.

When it was discovered by the S'nenymoes that the Northern visitors had departed, they came out in force, armed to the teeth, to bravely declare what they had intended to do had the Haidas remained another day.

"I wonder if they really would have attacked the Haidas," mused Neil as he and Harry sat that evening with the doctor.

"No," replied Dr. Benson. "They might have attacked the Squamish, or the Cowichans, or even the Kwakiutls—Cogwelts, the men call them—under like circumstances; but the Haidas! Well, that's another matter. I don't know that I blame them either, for those Queen Charlotte Islanders are holy terrors and they've always been able to back up their reputation.

"But the S'nenymoes are no cowards," he added. "There was trouble between them and the Cogwelts a few years ago, not long after the post was established here. Some of the Cogwelts were working in the woods, getting out timber for the mill. The S'nenymoes didn't like the idea, and ambushed them, killing three. The others escaped and made their way home.