* An independently-produced eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Magic, Murder and Mystery

Date of first publication: 1966

Author: Bruce Alistair McKelvie (1889-1960)

Date first posted: April 10, 2014

Date last updated: April 10, 2014

Faded Page eBook #20140421

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines

By B. A. McKELVIE

(1890-1960)

Author of

Pageant of B.C.

Fort Langley—Outpost of Empire

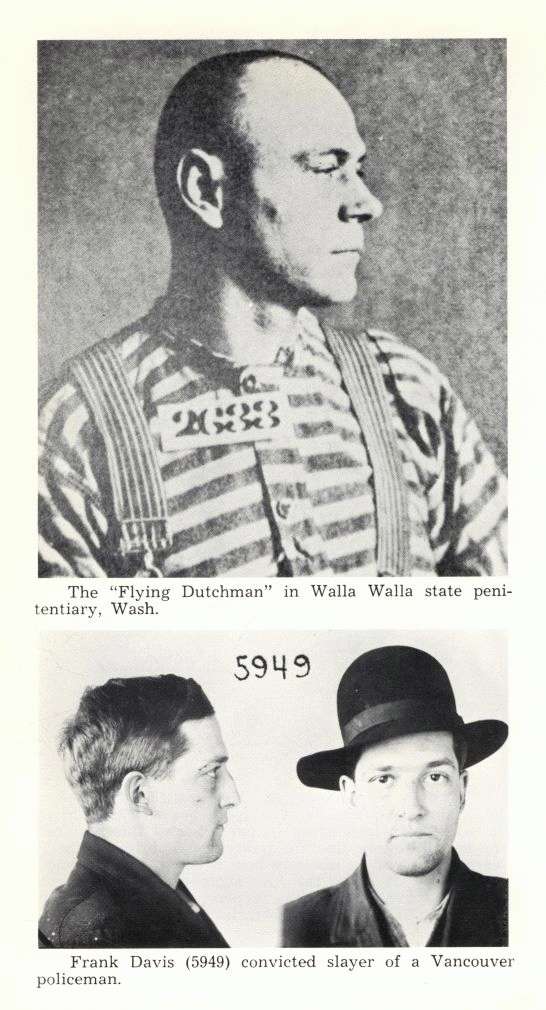

Tales of Conflict

Maquinna the Magnificent

and other B.C. historical works

Family Address: Rural Box 142, Cobble Hill B.C., Canada

COPYRIGHT 1966

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED BY

COWICHAN LEADER LTD.

DUNCAN. B.C.

To my friends of the newspaper profession with whom it has been a

delight to work; and to my gallant acquaintances of the police whose

collaboration made possible so many of the stories retold here—this

book is cordially dedicated.

—The Author

For half a century I have not only been recording the passing scene but have been delving into the history of the Pacific Coast. I have been flattered by the many kind things that my friends have said of my writings, and some of them have suggested that I republish a few of the stories that have made appeal to them. This book is in answer to that request.

It would not be possible, of course, to do so without the generous permission of The Vancouver Province, for which I wrote for more than thirty years, and The Victoria Colonist with which I was associated for seven years.

It is right that I should acknowledge the courtesy and kindness of the Provincial Librarian and Archivist and the competent and efficient members of his staffs. I wish to particularly thank Cecil Clark, whose stories of crimes are so capably portrayed in The Colonist, for the loan of photographs.

Wherever it has been possible to check facts by official records this has been done.

I am again delighted to express my deep appreciation of the inspired skill of Dr. H. G. Grieve, and his brilliant associate, Dr. D. P. North, Victoria ophthalmologists, who twice in the past year have withdrawn grey curtains from my eyes. They made it possible for me to prepare this collection of stories for publication.

Cobble Hill, B.C.

B. A. McKelvie

ILLUSTRATIONS

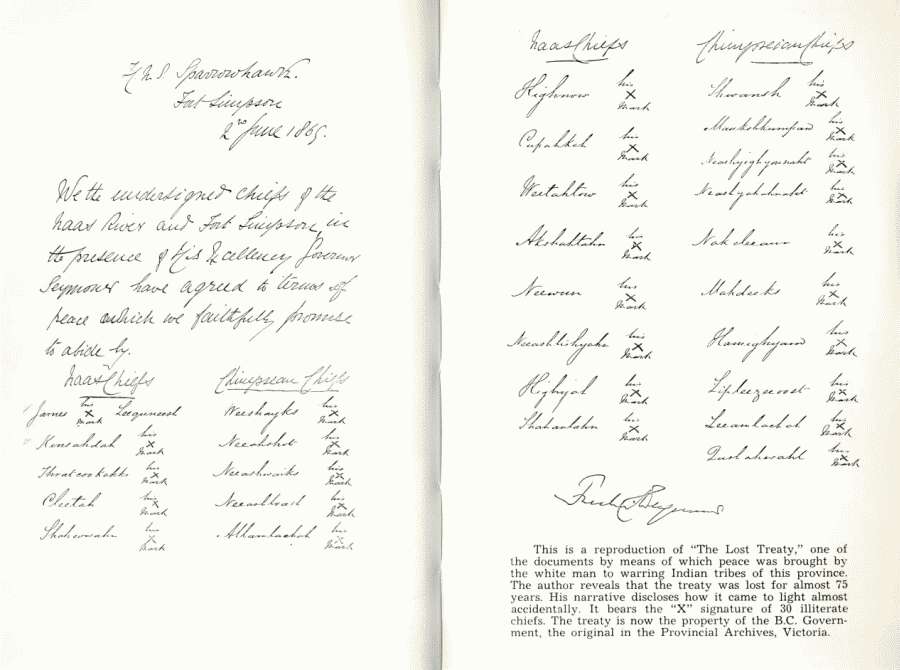

Acknowledgement is made to the Provincial Archives of B.C., Victoria, for a copy of the "Treaty of Fort Simpson," reproduced among eight pages of pictures in the centre of this book.

Contents

Chapter 1. Brother XII's Magic

Chapter 2. Canadian Counter-Spy

a. Germany Planned Conquest

b. Price of Peace

c. The German Mail Pouch

d. The Fat Cook

e. There Was No Strike

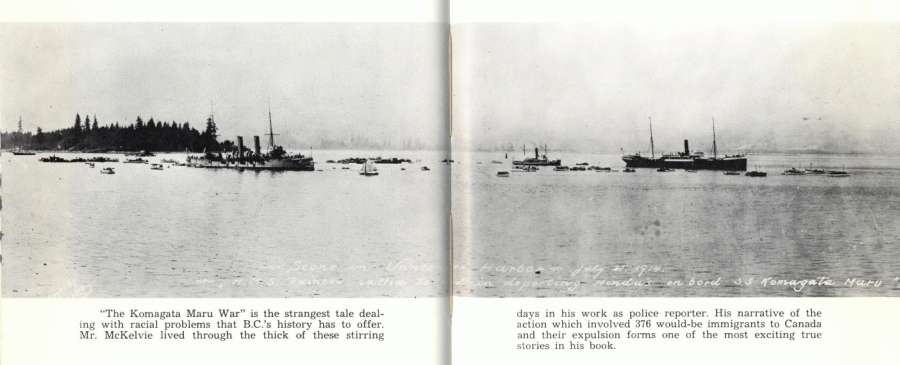

Chapter 3. The Komagata Maru War

Chapter 4. Who Killed Quantrill?

Chapter 5. Gold and Trouble

Chapter 6. Five Aces and Death

Chapter 7. Murder of Young Probert

Chapter 8. The School-Boy Killer

Chapter 9. Who Was the Mystery Figure?

Chapter 10. Death Walked Softly

Chapter 11. Slaying of Dr. Fifer

Chapter 12. Frock-Coated Banditry

Chapter 13. The Penticton Murder Mystery

Chapter 14. Who Slew Aeneas Dewar?

Chapter 15. The Flying Dutchman

Chapter 16. Death Comes to the Bridegroom

Chapter 17. Battle of Hazelton

Chapter 18. The Killer Instinct

Chapter 19. Under the Iron Washtub

Chapter 20. "Hang With the Gang"

Chapter 21. Trading Dangerously

Chapter 22. The Incriminating Knife

Chapter 23. Shipwreck and Slaughter

Chapter 24. Battle in Jail

Chapter 25. The Smallpox War

Chapter 26. Gates of Hell

Chapter 27. Sam Johnston—Canadian Hero

Chapter 28. The Stone Giant

Chapter 29. First Magistrate's Manual

Chapter 30. The Lost Treaty

Chapter 31. The Big Black in Cariboo

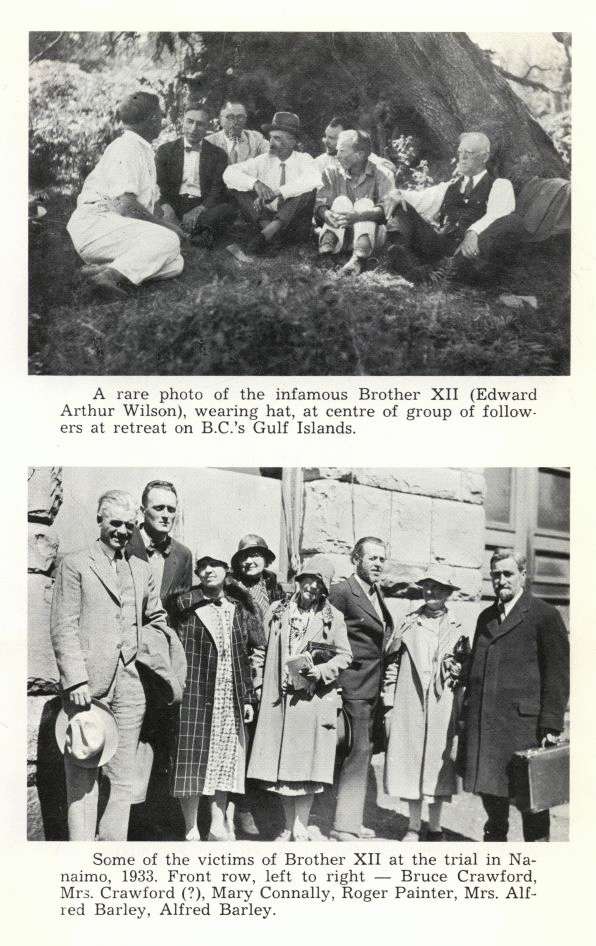

How the protective power of an alleged West Coast charm overcame the malevolent threat of black Egyptian magic was only an incident in the strangest case ever heard by the Canadian courts of justice.

The tale would be unbelievable if it was not supported by official transcripts of evidence taken in police court and at a civil trial. These documents reveal how 8,000 persons throughout the world were held in subjection by a self-styled divinity who claimed to have fathomed the age-old mysteries of Egypt. Not only sorcery but stories of fiendish cruelty, buried gold, islands of the Gulf of Georgia fortified, and attempted murder by mental processes were but some of the things that witnesses described as being directed by Brother XII at the Aquarian Foundation headquarters near Nanaimo, Vancouver Island, B.C.

Since the dawn of time man has been prone to follow leaders who lay claim to mystical knowledge denied to ordinary mortals. Primitive peoples have been dominated by fear of the supernatural, and clever medicine men and voodoo doctors have capitalized upon the credulity of their fellows to enrich themselves. The number of such soul-swindlers is enormous, but for downright genius in the world of spiritual exploitation few can compare with Edward Arthur Wilson, alias Julian Churton Skottowe, alias Amiel de Valdes, alias Brother XII.

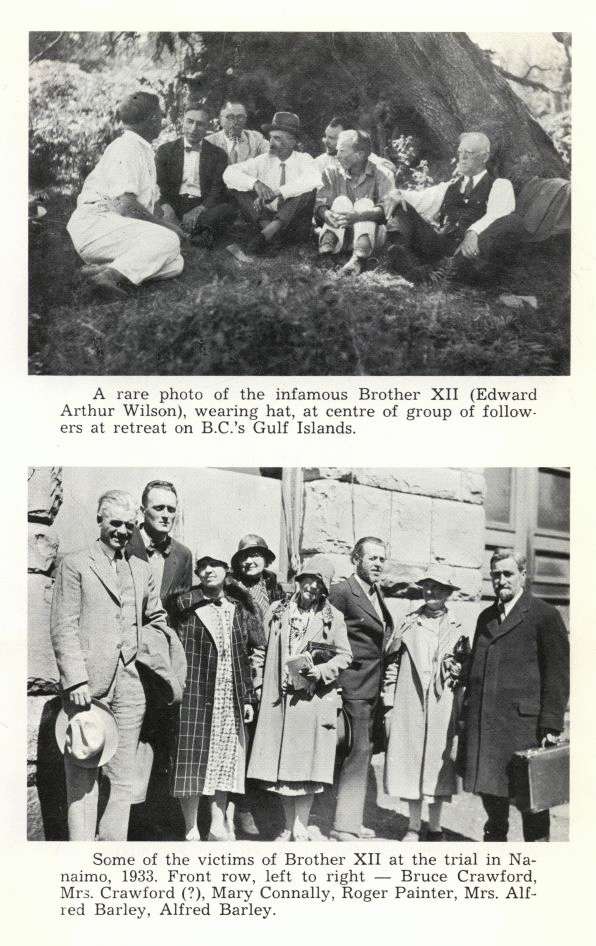

It was in 1928 that I first heard of Wilson and the Aquarian Foundation located on a beautiful site in Cedar district, some few miles from Nanaimo. There, amid the towering firs and hemlocks, the mighty cedars and spreading maples, the guru of a mystical cult had established the Aquarian Foundation on 200 acres of choice land that in early times had been a favorite meeting place for the peoples of Cowichan stock.

At this peaceful and romantic spot he had gathered a few selected followers, from a membership scattered throughout many countries. They were privileged to buy lots, build houses and join in directing the preparation of the world for the coming of a new sixth sub-race, which was being ushered in under the guidance of the star Aquarius. In the centre of the estate, in a little glade, shrouded by the heavy foliage of large cedar trees, Brother XII had constructed the House of Mystery, a small one-roomed structure. Into the sacred precincts of this place, he alone could enter. There he was said to go samadhi and project his ego to the higher planes where he would commune with the Master of the Wisdom, and his fellow members in the Great White Lodge.

During his reputed absences from his bodily habitation the devout brothers and sisters in residence at Cedar-by-the-Sea, were charged with the great responsibility of congregating along a wire that crossed the pathway about 100 yards from the House of Mystery; there they were instructed to concentrate and meditate, thus helping their leader as he passed from plane to plane.

At this point may I interpose to say that I have the utmost respect for the sincerity, the piety and the altruism of the followers of Wilson. Their fault was that they believed him and his doctrines. They suffered terribly, but endured physical and mental agonies in the belief that such came to them to test their fitness to participate in the work that was to save humanity.

The son of a missionary to India, his mother is said to have been a native princess. At the time that he became prominent as a religious leader he was about fifty years of age, a slim, swarthy man with hypnotic eyes and a graying beard.

The commencement of the story of Wilson on the West Coast of Canada goes back to the turn of the century. At that time he was in the employ of the Dominion Express Company and was moved from Calgary to Victoria. He was devoted to the sea; it fascinated him, and on holidays and long week-ends he sailed about the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Gulf of Georgia.

After some time had elapsed since his coming to British Columbia's capital city he asked the express company for an increase in the modest salary being paid to him. This was refused. Wilson resigned. He obtained employment on a steamer running between Seattle and San Francisco and making calls at Victoria. From this coastal employment, he changed into deep-sea ships and in the ensuing years he roamed the sea lanes of the world, and eventually became a master mariner. In the long voyages about the globe he spent much time studying the religious and philosophic mysteries of the ages. He made contacts with groups in many lands who were fascinated by similar research.

In 1924, he was at Nanaimo. He was unemployed, and was unable to settle his room and board bill. To his landlady he explained that he could not pay what he owed her, but that if she would trust him, he would recompense her well, for he would be back in two years with plenty of money, as he was going to start a new religion.

A year later, he was in Genoa, Italy, ill and still low in funds. It was time for him to capitalize upon his years of study. He sent out a veritable flood of letters and announcements to correspondents in England, United States, New Zealand, and elsewhere. Like Joan of Arc, the "Maid of Orleans," he had dreams, and these visions he related in his communications, later incorporating some of them in book form.

Here is his description of the miraculous calling of him into spiritual service:

"About 9:30 p.m., October 19, 1924, I was not well and had gone to bed early. At this time, I wanted to get some milk to drink, so I lighted the candle which stood on a small table at the side of my bed. Immediately after lighting it, I saw the Tau suspended in mid-air just beyond the end of my bed and at a height of eight or nine feet. I thought: 'That is strange, it must be some curious impression upon the retina of the eye which I get by lighting the candle. I will close my eyes and it will then stand out more clearly.' I shut my eyes at once, and there was nothing there. I opened them and saw the Tau in the same place, but much more distinctly; it was like soft golden fire, and it glowed with a beautiful radiance. This time, in addition to the Tau, there was a five-pointed star very slightly below it and a little to the right. Again I closed my eyes and there was nothing on the retina. Again I opened them and the vision was still there, but now it seemed to radiate fire. I watched it for some time, then it gradually dimmed and faded slowly from my sight.

"The next day I made a note of the matter and recorded my own understanding of it, which was as follows: 'The Tau confirmed the knowledge of the special path along which I travelled to initiation, i.e.; the Egyptian tradition, and the star was the Star of Adeptship towards which I have to strive.' Now, today, the Master tells me that that is true but there was also another meaning, hidden from me then, but which he now gives to us. The Tau represents the age-old mysteries of Egypt, and the Star of Egypt is about to rise; the mysteries are to be restored, and the preparation for that restoration has been given into our hands. In the great Cycle of Precession, the Pisces Age has ended, the sign of water and blood has set, and AQUARIUS rises—the mighty triangle of Air is once more ascendent, and we are to restore the 'Path of Wisdom and the First Path—Knowledge.'"

Such, according to this self-proclaimed religious teacher, was the manner in which he first learned of his selection to undertake the restoration of the mysteries of Egypt. It is noteworthy that from the very outset of his great deception, he stressed the mysticism and magic associated with the ancient dwellers in the Valley of the Nile.

He was, at least, keeping faith with his Nanaimo landlady by starting a new religion.

This initial vision was followed by another miracle, which again stressed the Egyptian base for his Aquarian doctrine. Here is what he said. He heard a voice which cried, 'out of its immense and awful distance':

"Thou, who has worn the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, of the High Knowledge and the Low, humble thyself, prepare thy heart, for the Mighty Ones have need of thee. Thou shalt rebuild, thou shall restore. Therefore prepare thy mind for that which shall illuminate thee.

"A cold wind blew down that enormous aisle of pillars; somewhere in the endless distance lights seemed to move, then from above my head the light flooded me so that the distance and the vistas were dissolved. Then the light faded and I lay still, filled with a sense of wonder and great reverence ... The Master bids me say that the voice was the Voice of Dhyanis, of the great Tutelary Deities of Egypt, whom, in the past, we worshipped as 'the Gods.' As I write, further knowledge comes to me. I have to tell you that the moment when you meet in this knowledge and for the purpose of discussing it, will be the moment for which forty centuries have waited."

"I am not a person filled with power, but a power using a personality," he declared in a circular letter written shortly after from the Italian Riviera ... "The hour has struck for this earth to be plowed and harrowed. I have been called to drive the plow, to break the crust and to harrow the surface. You must choose whether you will be the plowshare or the clod which is broken, for the grounds must be prepared that the seed may be sown."

Wilson now announced that he had been spiritually translated to the highest realm, where he met the Masters of Wisdom, who had initiated him as Brother Twelve of the Great White Lodge, thus completing the membership of that body which was, until then, composed of eleven of the greatest religious teachers of all time.

Claiming divine collaboration, he now penned a small volume, which he named "The Three Truths," and which became regarded as the Aquarian Bible—a Holy Book. He circulated this widely after its publication in England. It was a modest little production such as any well-trained writer who had at his disposal a library of mystic beliefs, might have put together.

Having received assistance from friends he was able to go to England where he located in rooms at Southampton. Here, in the old seaport, he claimed that he went samadhi and his spirit soared to the highest heavenly level to confer with the Masters, while his mortal body remained in his lodgings. On this ethereal adventure, so he announced, he had been welcomed anew by the Masters, who gave him a map, and instructed him to go out into the world and locate the place depicted on the chart. They told him it would not be found in either Mexico or California, but in a country known as "southern British Columbia." Making announcement of this revelation, he wrote that he had never been in British Columbia in the flesh:—and his landlady was still waiting at Nanaimo for her money!

Among the serious-minded people who were impressed by the claims and assertions of Brother Twelve was a fine elderly couple residing in London. They went to Southampton to meet him. Alfred H. Barley, a retired chemist, and his wife, Annie, who for twenty-eight years had been a teacher for the London County Council, came into possession of some of the writings of Brother XII. They were captivated by the altruistic aspirations and doctrines of brotherly love, and left their London home to visit Brother XII in his Southampton lodgings. Here they met a woman introduced as his wife. The guru told of woe for the world, and advised the Barleys to sell their securities and home that they had accumulated as a provision of their old age. This they did, selling considerably below the then market.

They volunteered to follow Wilson whither he might lead them, after he showed them the map, depicting the selected spot that the Masters of the Great White Lodge had drawn for him. It was here, at this divinely-favored place that a City of Refuge was to be set up, he assured them.

Another young man, the son of well-to-do parents, was also induced to accompany Brother XII to the West Coast of Canada in search of the acreage chosen by the Masters as the Land of Promise.

The little party crossed the Atlantic and the continent, stopping once or twice to confer with prospective members, but like a homing pigeon Wilson led his little band of disciples directly to Nanaimo. (Whether or not he paid his debt to the landlady was not disclosed.) They took a small dwelling near Northfield, and from there, he led them some five or six miles south of Nanaimo on the old highway to Cedar and then another two or three miles out to the island-studded waters near Boat Harbor. The map was reverently unrolled and spread on the ground. There, in actuality, were the islands, the bays, the points, channels and waterways shown on the chart of the gods. Wilson was justified!

It was an excited little party that hurried back to Nanaimo to start sending out telegrams and cables announcing the finding of the divinely-appointed tract for the location of the Aquarian Foundation and the City of Refuge. The response was stupendous; money started to pour in from every quarter. One lawyer in Carthage, Missouri—or his agent, The O. H. Hess Foundation—could not wait for the slow-moving processes of the recognized banks, or even for the mails to carry his donation. He wired $10,000.

Soon the movement had reached enormous proportions. It was stated that, by the summer of 1928, there were 8,000 members making regular contributions to aid Brother XII in his grand work.

Having located the appointed site, the Brother purchased the 200 acres indicated on the plan and in accordance with the instructions that he said he had received from the Masters, he laid out the land. Along the seafront he had building lots surveyed for sale to those who were to be permitted to come and live at headquarters; in the centre of the tract was located the sacrosanct House of Mystery, and the wire that barred the pathway to it was so placed that the favored few who were in residence at Cedar-by-the-Sea could not even look at the holy structure. It might be embarrassing if they saw smoke issuing from the chimney at a time that The Brother was supposed to be in the heavens!

But just where the trail left the clearing where the houses were built, there was a great moss-draped maple, which became known as the Tree of Wisdom. Here the guru would sit, on occasion, while followers grouped about him and listened in awe to the profound utterances that fell from his lips.

These were the golden days of the Aquarian Foundation—during 1927 and part of 1928. The erstwhile penniless mariner was an uncrowned king. Money continued to flow in with every mail, and the hotels at Nanaimo could not accommodate all who drove up in expensive cars from United States to sit at the feet of the teacher and imbibe wisdom.

Brother Twelve, in selecting those who were to be privileged to reside at headquarters, was careful to invite only one man, or man and wife, from a locality. In this way, those who responded and came to Cedar-by-the-Sea were strangers to each other before their coming, and were consequently more dependent upon him.

What manner of men and women were these followers of Brother XII, who were so persuaded by his teachings that they were prepared to forsake all and follow him? They were individuals who were above the average in learning and in advantages. For instance, there was Will Levington Comfort, the writer; Bob England, for eight years a member of the United States Secret Service; Dr. Coulson Turnbull, Ph.D., Los Angeles; Clara Phillips, a writer for such publications as the Washington Post and the New Orleans Picayune; Maurice and Alice Van Platon, a wealthy couple from United States who erected a fine home at Cedar, while E. A. Lucas, Vancouver lawyer, was also an early adherent.

Not only the wealthy, but poor working men were meat for the Brother. Those who could not contribute their thousands could, at least, work, and a few were chosen to come to Cedar-by-the-Sea to toil at building, farming, and fishing. He had an old naval cutter, and into this he was lifted by the disciples, to the accompaniment of a naval salute of uplifted oars. Then he would be rowed about the waters of the Gulf of Georgia for hours on end. He still loved the sea.

Now Mrs. Mary Connally entered the picture. She was the wife of a millionaire living at Ashville, North Carolina. She was travelling in the west when she first heard of Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation. She read some of his books—for by now there was a regular spate of literature—books, pamphlets, tracts and a monthly magazine, the Chalice—being broadcast. The writings made an appeal to her. She sent a modest contribution of $2,000 but intimated that there was more, if needed.

Brother XII was not one to refuse to follow up such a monetary prospect. He was also aware that the United States laws covering postal fraud were far more severe than any that might be on the statute books of Canada, so he wrote to Mrs. Connally to meet him at the St. George Hotel in Toronto. The appointment was made and he left for the east by way of Seattle, to keep it.

On the train out of Seattle he encountered the wife of a physician at Clifton Springs, New York. He convinced this woman that she was the reincarnation of the goddess Isis, while he was the god Osiris, in person, and it had been decreed for 26,000 years that she should play an important part in preparation for the coming sixth sub-race. She believed him. She waited in Chicago while Brother XII went on to Toronto, where Mrs. Connally, and her cheque book, were waiting. Mrs. Connally was entranced by the vision of helping suffering humanity, and immediately raised her original contribution to $25,000.

Mrs. Connally later told of their talk in the Toronto hotel: "We had a talk for about three hours, and he told me just what he was going to do," said the elderly woman. "He told me about the settlement, and we discussed the City of Refuge. One of the principal reasons I was interested in this work was the fact that children were to be in it. The main purpose, as outlined—the specific purpose—was to gather together a few people who were willing to adopt what they call the simple life and the higher life, and train themselves so that they could teach their children and other children ... and there would be a children's school, and we would teach them so that in the years to come they would have a chance, and not be brought up in this jazz atmosphere..."

And it was on this appeal to the mother love of this fine grandmother of sixty that Brother XII boarded the train at Toronto that night for Chicago and Isis with a cheque for $23,000 in his pocket. He met the reincarnated Egyptian goddess and together they embarked for Cedar-by-the-Sea.

A week later Osiris and Isis appeared at the cult headquarters. There were murmurings. Mrs. Wilson did not like it, and said so. She left the sacred locality. The Van Platons and E. A. Lucas did not like it, nor the former secret service man, Bob England, but for a time they bowed before the immutable laws of the gods. But when Brother XII took his Isis into the holy precincts of the House of Mystery there was a flare-up. Brother XII resented criticism. He decided that the associations of the Egyptian god and goddess reincarnated were matters of personal concern to them alone. So he announced the starting of a new settlement to be called "Mandieh" where only the elect of the elect could assemble. To this end, he took $13,000 of the Connally contribution and purchased 400 acres on Valdes Island, and there he went into retreat with Isis.

Now revolution flamed. England and Lucas and Van Platon doubted the divinity of the instructions concerning Isis. England, who was the secretary of the foundation, had Brother XII arrested, charged with misuse of the Aquarian funds in purchasing the Valdes property for the development of the Mandieh settlement.

Brother XII countered by having England charged with misappropriation of $2,800 and arrested, and, incidentally, in justification of his conduct, Wilson proclaimed a doctrine of free love, which he had printed in the Chalice, the cult magazine. This long attack on conventional marriage is now a part of the records of the Supreme Court of British Columbia.

Mrs. Mary Connally hastened across the continent to give evidence for the guru in the police court, only to find that she was to become keeper of the unfortunate Isis, whose reason gave way. Barley and his wife remained loyal to the Master.

It was a hot September day when they came up for preliminary hearing in the old city council chamber at Nanaimo, before Magistrate C. H. Beevor-Potts. The room was crowded with revolutionists and those who were faithful to Brother XII.

When the charge against England was called in the afternoon, an elderly lawyer, T. P. Morton, appearing for him, had a sudden dizzy spell. This collapse—though only momentary—had a most pronounced influence upon future happenings. Every Aquarian—unless it was Brother XII himself—was convinced that the interruption was a result of the use of black Egyptian magic by the Master!

The magistrate, however, held no such idea; he bound both accused over to stand trial at the forthcoming assizes. But, before the court was called, Bob England vanished. No one heard of him after that time. When he failed to appear to prosecute Brother XII, the case against the leader was not called. There was not a person who dared to append his or her name to new information. They remembered how the lawyer had collapsed—and feared the awful consequences of black magic.

It was earlier in this same year, 1928, that an electrician from Spokane was returning to United States by way of the bus from Vancouver to Bellingham. Seated beside him was an automotive mechanic of the B.C. Electric Company, which operated the bus service. He was going down to the border to repair one of the company's vehicles, which broke down on its way to Vancouver. They, as usual with good artisans, fell to discussing their crafts. The electrician told his fellow-passenger how he had just been at a "strange place near Nanaimo, installing the finest microphone system west of the Rockies." This, he went on to explain, was a work that he had to do in secret. It consisted of a number of microphones hidden behind foliage, stones and tree trunks along the line of a wire crossing a path, and leading into a "mysterious little house." My friend, the automotive man told me, and, as a newspaper man, it interested me.

The wire was the one that Brother XII had stretched as the nearest approach to the House of Mystery that none but he could use. He would announce a visit to the Master of the Wisdom, and that he would be away, possibly four days. The brothers and sisters would be admonished to help him by concentrating upon certain truths. They would gather along the wire, and for some hours not a word would be spoken. Then, perhaps a remark about the weather would be made; an answer, and then conversation would become general. Next afternoon, or even on the third day, the Master would come storming down the path. "You, brother Jones, interfered with me on the Fifth Plane; you said to Brother Smith..." and he would retail what had been said; "And you, Brother Deluce said to Brother England..." and so on. The guilty flock would look at him with mouths open and eyes staring; He was omnipotent! He knew all; saw all! It was with such methods that he had control of the minds and being of every person permitted to dwell at the Foundation.

When the failure of Bob England to appear to prosecute him in the assize court freed him from the charge, Brother XII kicked out the malcontents and set about gathering around him new and more obedient disciples.

Roger Painter and his wife, Leola, were brought from Florida, where the long-haired, bearded Roger was called the "wholesale poultry king" of his state. He had a poultry and produce business with an annual turnover of $1,000,000. His contributions before coming to B.C. had been many and large; "Brother XII would write for money; I would send a cheque for five or ten thousand, or more. I kept no account of how much I gave, he told me, but I do know that when I gave my business to my brothers and came here to dedicate my life to the work, I brought $90,000 in cash. Today I don't have a nickel—he got it all."

Bruce Crawford and his wife, Georgie, another splendid couple, ran a cleaning and dyeing establishment in Lakeland, Florida. They brought $8,000 with them to help the cause. They had made other contributions—and so the story went. The new-comers mostly brought substantial sums in cash.

Came also from Florida Mabel Skottowe, a red-headed woman of about forty, as strange and peculiarly vicious as Wilson himself. She became his first lieutenant, and he declared: "She is my eyes, my ears, my mouth; whatever she says, you must do." To others she became the impersonation of the devil.

The guru kept control of every mind. He confided to each of his disciples that the Masters approved of that particular individual, but he was the only one of the lot who was in such a happy position, and his very soul depended on his not confiding in any other person, except, of course, Brother XII himself. Thus, each became suspicious of his neighbor and more dependent upon the wily Wilson.

Wilson now changed his name by deed poll from Edward Arthur Wilson to Amiel de Valdes, and Mabel Skottowe, by similar legal process, Zura de Valdes. She was immediately dubbed "Madam Zee" by her associates.

Having restored order, the de Valdes pair decided that the Aquarian harvest was ready for the scythe in England, so they went away to Europe. Before leaving they transferred the title of the original settlement at Cedar-by-the-Sea into the name of Alfred Barley, while Painter, the mystical butter and egg man from Florida, was appointed as the erstwhile spiritual guide.

Following their departure, for the first time, there was peace and contentment on the island. The people got together and compared notes—and found that each had been told the same story about consorting with others. But they wanted to show that they were workers while the Master was absent; they toiled hard, and cheerfully that they might have a worthwhile showing for his return.

But after Brother Twelve did return there was more trouble, and eventually the banishment of twelve individuals, including Mrs. Connally, the Painters and Alfred Barley and his wife. This led to a lawsuit in the Supreme Court of British Columbia in April of 1933, before Chief Justice Aulay M. Morrison. What follows is mainly from the sworn evidence given at the trials of Mrs. Mary Connally and Alfred Barley vs. Amiel and Zura de Valdes. The other statements I personally know to be true.

Now, let us go back to England, where we left the precious pair. There his smooth tongue managed to get some wealthy individual to buy him a fishing smack and transform it into a handsome yacht.

But Brother XII wanted to straighten some matters at headquarters before he returned, so he wrote to Roger Painter to remove five of his enemies by the use of black magic. Here is the story as told in the witness box to the chief justice. Under examination by Mrs. Connally's lawyer, V. B. Harrison, Painter said:

"The whole island, as I can look back through it all now—the whole scheme was to drive you into intense fear and confusion so that you were glad to go and leave your money and goods behind, regardless of what it might cost you. That was the operation; so that you could get away, and get away from it and leave it forever. He had our money; he had our goods; he had everything we had. We understood that we had to surrender everything. We believed in it. We did it ... He, mentally, endeavoured to control the mentality, the soul of everybody that came near him. If you raised one little finger—one thing in opposition, implacable hatred was given to you from that time on, and if need be, he would put into operation what I call 'etheric' work, working on the mind and etheric body of a man. He even murdered him.

Have you any example that you can give of his trying to murder people by that process?

A. - "I certainly have.

Q. - "Can you mention the persons?

A. - "I can mention plenty of names. I got a letter from him while he was in England requesting me to go to work immediately on Mr. Pooley, the Attorney General of British Columbia.

Q. - "In what way?

A. - "To sever his etheric body from his physical that he might die."

Q. - "Any other person?"

A. - "E. A. Lucas, attorney in Vancouver; and Mr. Hinchliffe. Now I don't know Mr. Hinchliffe's particular position in the government at Victoria, but I know in his letter he said that he had opposed him in his request on the marriage relationship, and was very bitter, and it was needful that he should be removed ... and then there was Maurice Van Platon and Alice Van Platon that he instructed me to proceed (against) in an endeavor to sever them from their physical bodies.

The court - "Would it be reasonable to construe it as physical force against these people?"

A. - "Not physical force; he didn't use that word."

The court - "If I were to pick up that letter and read it, would it be a fantastic construction for me to say ... that I was to go and kill that person. Have you got any of those?"

The witness replied that he did not have the letter; that he returned it to Brother XII.

Mr. Harrison - "You cannot recall the substance, can you, or any of the phrases?"

A. - "No, not particularly. The letter as a general thing is clear in my mind, but I couldn't repeat the exact language; but he made this remark in the latter part of this letter. He said, 'Now, Admiral, old scout, go to work and have me a scalp by the time I arrive home!'"

Q. - "He said 'Old Admiral'; is that the word he used?"

A. - "'Now Old Admiral'" it's a slang phrase in the States—it's a slang phrase. Now then, in arcanum work,—it's a work in which people sit in a circle or triangle, or in whatever shape they may elect to sit—I found that all his work in that was towards what we term in occult parlance, 'black magic,' of a most devilish kind.

"I side-tracked that work. He couldn't touch the one that he tried to injure before I side-tracked it. He even kept this arcanum up at twelve o'clock at night; and I have heard people say that they did not believe in these things! But, generally, if one will have a little intelligence and dig deeply, they will find that much wickedness has been committed by such things."

The court - "Were you present at any of this?"

A. - "Yes, ... you have an arcanum when there are three in the operation. There is the defendant sitting in one position, and Zura de Valdes sitting in another position, and myself in a third position. Now we make certain statements, and certain statements are made to invoke certain powers, invisible, of course, your Lordship, and the commission; whatever you want to establish or work to be done in the etheric or mental realm, it was done by the one who laid down the area—and that was invariably Wilson. Oh, it would take months to relate all the things!"

The Court - "What did he say?"

A. - "Well, for instance, he would stand a man up there in imagination, someone that he hated—that he had this implacable hatred for...

The Court - "What did he say?"

A. - "He would stand him up there in the centre, in imagination, and then he would begin his tirade, cursing and damning that spirit, and then going down this way with his hand (vertical stroke, from head downward), and this way (horizontally from left to right), cutting what they call the etheric, which is the finer body, and then the physical body, this from which the physical gets its life. Then we cut that ... and the physical organism would gradually become depleted and would die."

Such was the lethal process of mental murder, as solemnly explained to a hushed courtroom by Roger Painter, a firm believer in magic, and formerly a $1,000,000-a-year poultry dealer from Florida.

In due time Brother XII and his alter ego started on their way home aboard the yacht Lady Royal—and she was a sweet little vessel to delight the heart of any sea-lover. She had a crew of English sailors, with Captain Wilson, himself, naturally, in command. At Panama, however, the white crew was discharged and a new crew of Panamanian Indians was employed. In this manner, the Lady Royal came up the American coast, and under cover of darkness slipped into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Passing up immigration and customs, she ran into a cove on one of the San Juan group of islands in U.S. waters. Then Wilson and Zee in a gas boat came up to the Aquarian establishment on the DeCourcy Islands, and a tugboat was sent down to tow her into port.

Brother XII's single-unit navy had grown in the years since he used to have his docile followers give an admiral's salute with their oars when he appeared, lift him into the sternsheets and row him about. It now consisted of several launches, a tugboat, a powerful diesel-engined ocean-going yacht called the Kheunaten, in honor of another Egyptian king and deity, and of course, the new Lady Royal.

When the yacht arrived, the Indian crew unloaded some mysterious packages. These were hidden under the personal direction of Wilson, and the sailors then were shipped back to Panama. After their departure, Brother XII sailed the empty boat into Nanaimo, apologizing for not having reported to immigration and customs, saying it was through ignorance—and him, a master mariner!

Just what was in those packages is not known, but whatever it was the prophet did not want the authorities to know its character. He now purchased cases of rifles from Eaton's store in Edmonton, and ordered all other construction work on the main island of the DeCourcy group to halt while gun pits were constructed, and these he instructed should be manned by the men, while the women walked from one to the other, and kept watch on the bay to give notice of the approach of any government launch. The men had instructions to repel any attempted landing from a government boat. And while his dupes were doing so, he would skip across the island to where the Kheunaten was riding, ready to carry him to safety. But the government was supremely indifferent to him and so there was no shooting. Shooting, at best, was a messy job, and not nearly as hard to prove as mental murder.

The DeCourcy Islands had also been acquired through the generosity of Mary Connally. There were five islands in the group, but only the DeCourcy and Link Islands were utilized. Alfred Barley was again mulcted of a small inheritance to help along this work. It was here that the City of Refuge was to be built, and not on the mainland of Vancouver Island, where the headquarters was located. He told Mrs. Connally that Greystones, a wonderful stone school with walls five feet in thickness, would be built on the island, and beside it would be a wonderfully fine home, and she could live in this palace. But all this was before he and Zee went to England.

Now that he had come back, and found that Painter had not gathered any scalps for him; Mary Connally and the Barleys had no more money, and some of the others were showing a trifle of independence, he banished twelve of them; ordered them off the islands. But he forgot that he had placed the deeds to the Aquarian Foundation's original settlement in the name of Barley. They all went there, to Cedar-by-the-Sea.

Painter, the Barleys and Mrs. Connally journeyed to Nanaimo and interviewed Victor B. Harrison, a prominent lawyer and oft-time mayor of the city.

It was now 1932; I was reporting the Imperial Conference at Ottawa when I received a letter from my old friend, Vic Harrison. He said, "I know you have been trying for years to obtain the truth about Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation, so I thought that I would let you know that I have been retained by two members of the cult to enter suit against Wilson in an effort to recover some of the money they have contributed. I do not expect to have the statements of claim ready for registering for several weeks, by which time you, no doubt, will be home."

I was at the time, managing editor of The Victoria Colonist. I returned and waited. Weeks passed and there was no indication of the action being officially launched. I got into my car and drove to Nanaimo, and asked Mr. Harrison about it.

"I don't know if I can get them to go ahead," he gloomily answered.

"Why?" I asked.

"Do you remember that case in the police court in 1928, and how England's lawyer fainted?"

"Yes."

"That's it: they say that he was knocked over by the black magic of Egypt, and they're afraid that if they start action, they will all be killed by similar dark powers. Then there was the disappearance immediately after of Bob England—and that has never been explained."

"Do you mind if I go and have a talk with these people—where are they living?"

"No," answered the lawyer, "if they will listen to you that will be all right. They're living at Cedar-by-the-Sea. Brother XII transferred the title to that part of the Foundation to Barley, and forgot to have it transferred back to him before he kicked old Alfred off DeCourcy Islands. So they have all gone over to Cedar. I'll tell them that you're coming and that they may talk to you. When will you be there?"

"This is Monday," I mused, "better tell them I'll be there on Friday—it's a mystical day."

So that is how I came to be at Cedar four days later. I took my nephew, Neil, with me. When we arrived at the Foundation the disobedient twelve, who would no longer obey the guru, were waiting for us. They took us into the large house that had been used as the headquarters centre.

We were conducted into a big room. Two chairs were placed against a blank wall for us, and twelve more were arranged in a semi-circle around them. We were seated, and then they started to tell us of the manner in which Brother XII and Madam Zee had been treating them; but repeatedly they stressed, "There is nothing wrong with the religion: it is sound and true; it's Wilson, and the only thing we can believe is that he is not himself; that the powers of darkness have taken control of him."

They were sincere; their tensed attitude and straining eyes showed that they were all in a highly nervous state. I looked around the half-circle of pale faces, and decided to take a chance.

"I understand that you are afraid of Brother XII's magic?"

"Yes," answered Painter, the magician, and before he could say more, another member broke in; "Do you know he tried to kill Mary Connally with magic last Tuesday, but we knew of it through occult means, and she left her house and spent the night with Mrs. Barley. Bruce Crawford slept in her house, and all night he had to wrestle with the black influence!"

"Yes," admitted Crawford, "in the morning I was mentally and physically exhausted; I have hardly recovered yet."

Again I looked at the mentally-harassed group, and then: "This is Egyptian magic, isn't it?" I demanded.

"Yes," answered Painter, "the most virulent kind."

"Pooh!" I snorted and snapping my fingers; "You've forgotten the first principle of magic!"

"What's that?" demanded Painter, as he and several others sprang to their feet—and so did Neil, who took a firm grip on the back of the chair so he would have some defence if needed.

"I mean just what I say," I declared. "Don't you know that where there is magic native to the soil, no foreign magic has any potency—and here you are living on one of the sacred grounds of the Cowichans; here they made their magic; here they made their medicine; here the young men went through their warrior tests—ye gods, the very ground is impregnated with magic! As long as you are here, nothing in the world can harm you."

Never have I seen, never will I again see such a simultaneous look of relief on twelve faces.

They thanked me time and time again, and showed me over the place and even permitted me to inspect the House of Mystery, with its little cook stove and food cupboard, and the cot on which Brother XII went samedhi. Here, too, Wilson listened to the chit-chat from the microphones at the wire and mentally tied them with it.

Next morning they rushed into Nanaimo and told Harrison to go on with the case. He entered suit on behalf of Mrs. Mary Connally and for Alfred Barley.

It was April, 1933, when the case came to trial before Chief Justice Morrison in the old stone court house at Nanaimo.

I went over to the court room a little early, and as I entered the building, Mr. Harrison came running up to me; "Good Lord," he ejaculated, "I can't get them into the witness box!"

"What's the matter, Brother XII has not turned up, has he?"

"No, but it's this damned Egyptian magic again. They say that Wilson has a satellite here who has thrown a spell around the witness box, and if any one of them steps into it, he'll die."

I thought a minute, and realized what a mistake I had made. I had localized the immunity to Cedar-by-the-Sea.

"Can you hold the judge for ten minutes?" I asked the lawyer.

"I think so," he replied, and started for the judge's chambers, while I dashed over to the Malaspina Hotel. I remembered that in my dressing case I had a double labret, or lip ornament, worn by the women of the Queen Charlotte Islands when the whites first came to the Pacific Coast.

Grabbing the bit of stone, I puffed back to the court house. I met Roger Painter in the corridor. "Come on in here, I want to show you something," I told him, and he followed me into an empty witness room. I shut the door.

"See this, Roger?" I asked, and cupped my hands around the labret.

"Yes; what is it?" he inquired.

"It's the greatest charm on the coast," I assured him. "That used to belong to the most famous of Haida medicine women. As long as you are in association with that, no power under heaven can hurt you."

His face lighted. "Lend it to me," he begged.

"Lend it—lend it? Why, man, I'd almost as soon lose my life as to lose that!"

"Oh, lend it to me," he pleaded.

"How long?"

"Just for this case."

"Well, swear I'll get it back," I ordered.

He took a most solemn pledge that I would get the bit of stone back at the end of the trial, so I passed it over to him, and he hurried away to inform the others.

Every witness entered the box holding the labret; looked Brother XII's man straight in the eye and told their story.

Just before Brother XII and Zee went away, Mr. Barley stated to the court, the Brother came to his house one night carrying a heavy burden wrapped up in a towel. "Take charge of this," he said, "I am afraid of fire."

The dutiful disciple did so, without attempting to ascertain the contents of the parcel.

"Later," Barley continued, "he wrote me from England, saying that the package contained gold. He instructed me to put it into a quart jam jar, and to fill the space up with paraffin wax. I was then to have a box made to contain the pot of gold, and was to bury it in a big cistern. I did so."

Mr. Barley went on to explain that Brother XII had insisted that all money that came to him should be in gold or Dominion of Canada one and two dollar bills.

Brother XII had other jars and boxes of gold. Bruce Crawford told of transporting the Brother and his golden hoard from place to place. "He would bury it on one part of the island, and then a few days later he would dig it up again and take it to other place. I was running the tug at the time. I could not say how much he had, for he would not tell me, but from the feel of it, I would say that in one lot I transported $4,000. He had it put into quart jam jars, and then I had to make a cedar box to hold each jar. I made about forty boxes."

The disciples were in no position to estimate the total receipts of the Brother. Each one of them knew of thousands of dollars that had been given to him, but none knew of the aggregate in contributions from the outside members.

In her testimony in her suit against Brother XII and Zee, Mrs. Connally told the court of the brutal treatment meted out to her. She was in her house at Cedar, she explained, when, without warning, the wrecking crew appeared.

"It was about six in the evening. They told me they had orders to move me at once to Valdes. I only had time to gather a few of my things. Then I was transported to Valdes and was dumped down on the beach. I had to carry my things on my back up a long hill from the beach to a house about a quarter of a mile away. The house had been vacant for months. There was one small heating stove and a tin camp stove in the kitchen. No explanation was made for the move. I had never done any manual labor before, but I was compelled to work hard packing great loads up from the beach. A guard was put over me, Mrs. Leola Painter, and she was instructed to make me work and to do nothing for me. I had hardly become settled in the big house before I was moved again. This time to a hut with a gaping hole in the roof, and with cracks in the walls. Here I had a straw mattress to sleep on.

"Then I was moved again, and I was told that I must disc and harrow and cultivate a three-acre field. I was brought up in ease and luxury and was not accustomed to farm work, and was getting along—I am a grandmother, Your Lordship, and am sixty-two. I had to work in that field from daylight till dark. I lost twenty-eight pounds."

Mrs. Painter corroborated the story. "I had to do it," she explained. "Zee told me I was not even to give her a glass of water, and I had to make her work. It was terrible to see her lifting those heavy loads. My heart cried out for her, and I would gladly have helped her if I could."

"Why couldn't you?" asked the court.

"Because I was afraid. Zee told me if I did so, I would lose my own soul."

Witness after witness took the stand to affirm the condition of slavery—slavery as the price of saving their immortal souls. Driven from daylight until long after dark these men and women worked frantically in abject fear, while Brother XII and the sinister Zee cursed them.

"I never knew that any woman could blaspheme as Zee did," said pretty little Mrs. Bruce Crawford.

Bruce Crawford was a businessman in a small way in Lakeland, Florida. He and his wife longed to work for humanity. They heard of the teachings of the great mystic in British Columbia. They became interested and were instructed to sell out all they had and bring the proceeds to Brother XII. They did so.

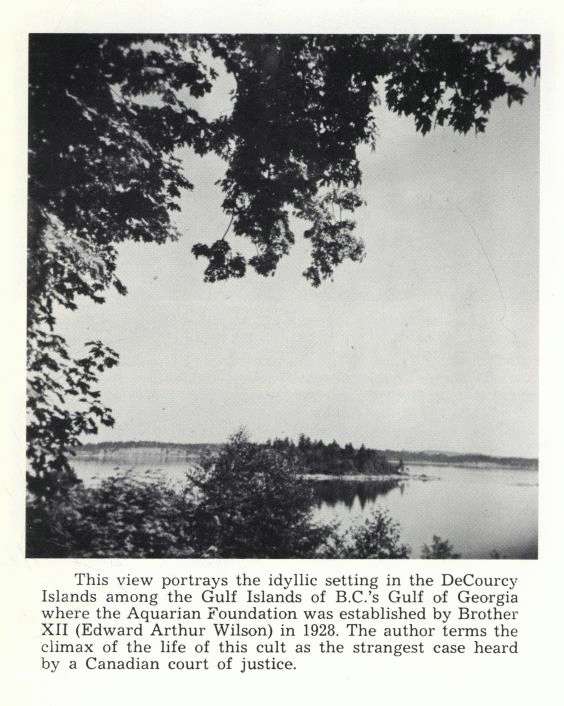

Filled with idealism and the hope that they could serve humanity, this fine-looking couple came to learn from the Master. Mrs. Crawford was immediately set to work as a goatherd. Her husband was placed on the tugboat.

"I had to tend fifteen goats," the woman explained. "One day I fell and hurt my knee. It was very painful. I could not take time to attend to it, and it was soon swollen to twice its size, but Zee would not let me rest. She cursed me, and called me lazy and drove me out to attend the goats. I was hobbling along one day and fell and injured my knee for a second time. I was an hour late in getting back to the farm. Zee swore at me and cursed me, and banished me to Valdes Island. There was a boat going there that afternoon. She would not let them carry my baggage on the boat. I was compelled to put it on my back and travel over the bush trail for several miles. I fell every three or four steps. Then I had to row from the Point to Valdes. My working day was from 2 a.m. until 10 p.m.

"Another time I was compelled to paint an outbuilding that was built over a cliff. It was twenty feet to the stones of the beach below. I had to hang over the cliff with one hand while I painted the back of the shed."

"Why did you stand for it?" asked His Lordship.

"Because, sir, I did not want to be parted from my husband again. I had been parted from him for six weeks before—and I did not want my soul destroyed."

William Lowell, a six-foot Nevada farmer, told of being forced to dynamite a tree so that it would fall between Link Island and DeCourcy Island to block navigation. When the charge only removed the earth from the roots of the tree and it still stood, he was cursed vilely by the delegate of the gods. Lowell was one of the fort guards.

Bruce Crawford told the court of a most distressing case. It was that of a young man of thirty, whom he called Carl, and his wife Alice, a pretty little woman of twenty-five. They had been invited to leave their United States home and visit the settlement. When Brother XII saw the young woman, recently a bride, he wanted her to stay at DeCourcy. He advised her that the divinities wanted her to start back with her husband, but in Seattle she was to quarrel with him and return to DeCourcy Island. She did so. The husband sought for her in Seattle, and finally traced her to the Canadian side. He obtained a boat at Chemainus and rowed the ten miles to the colony. The guards in the fortification saw him coming. He was captured and held prisoner all night, and next morning was taken on the tug to Yellow Point where he was dropped. Carl went to the Provincial Police, and returned with an officer. Brother XII swore that the woman was not there, and the frightened disciples were forced to corroborate his statements. Then, alarmed at the intrusion of the authorities, Brother XII had the unfortunate woman transported in the dead of night on the tug to a lonely beach many miles away. There she was marooned. No one knew what happened to her. She was in a strange country and without funds.

She may have gone insane. "It is a wonder that any of us retained our reason," commented Painter. "Three of our number did go insane," he said, and he gave the Chief Justice the names.

Being driven as slaves, lashed by the fear of losing their souls, robbed of their money, and forbidden to communicate with the outer world, these poor wretches were given only enough food to keep life in their bodies, while the prophet and Zee lived luxuriously.

At the conclusion of the trials Mrs. Connally was awarded judgment for $26,000 plus $10,000 special damages and was given ownership of the DeCourcy Islands and the Valdes Island acreage; Alfred Barley was awarded $14,000 and was not disturbed in his possession of the original settlement.

Wilson, with all his aliases and his riches and his red-headed companion, disappeared without trace. It was not until some weeks before the outbreak of war in 1939 that a legal advertisement in the stilted phraseology of the law courts, appeared in The Vancouver Daily Province. It was from London and announced the winding-up of the estate of the erstwhile Brother XII, and alleged that he died at Neuchatel, Switzerland, November 7, 1934.

But was he really dead? Many doubted it, holding that a man who was so false in life could not be depended upon in death. Then came the war, and the difficulties multiplied every day as London was bombed, and the courts and legal offices were blasted and destroyed—and nothing more was ever heard of Wilson, either as such or under any of his other names, or of the settlement of his estate.

There is a big pulp mill operating in the vicinity today, and the House of Mystery, the last time I saw it, was doing a very useful service as a home for an industrious worker, who was employed in the big mill.

When the German Kaiser plunged the world into the awful conflict that raged from 1914 to 1918, Canada's West Coast was intended as a place of major operation. German agents had migrated to British Columbia in droves for four years prior to the outbreak of hostilities. They had become entrenched in the fast-developing province, and especially about Vancouver that ever since 1907 had been in the grip of a real estate and building boom until its collapse in 1912. Kaiser Wilhelm, himself, was said to have been a heavy investor in Vancouver lots.

To understand why the Pacific Coast should appear so attractive to war-planners it is only necessary to look at the map of the world, as then internationally constituted. It will be noted that Vancouver and Victoria were at the geographical centre of the British Empire. About 75 per cent of the population of the area west of the Rockies was located within a few miles of those two cities. Vancouver was the main developed port, and through it went all trade and communication with Australia, and New Zealand; with Hong Kong and the Straits Settlement, via the Pacific. Japan, Great Britain's ally of that day, and China that kept the express cars of the Canadian Pacific Railway busy with rich cargoes of silk and tea and other expensive commodities, traded through Vancouver and Victoria; and also the Pacific cable stretched from Vancouver Island to other parts of the Empire across the western ocean. Yes, the strategic value of the southwest corner of British Columbia was enormous. So it was that enemy agents set up skeletal organizations to take military and civil control of the country.

That the German plans were not successful and that many plotters came to grief is largely due to Sir Percy Sherwood of the Dominion Intelligence Service and the men under him, who hastily organized as counter-spy operatives, accomplished marvels. By reason of the secrecy required at the time the vast importance of their work and the success that they achieved has gone without public recognition. They served Canada admirably and provided protection that was vital to the maintenance of the Dominion's full participation in the conflict. It is not suggested that all persons of German birth or lineage were trying to betray Canada. That would not be true, and it would be an injustice to many fine men who gave generously of their time, talents and resources to aid the war effort in all its ramifications. These people, for the most part, were naturalized citizens, who were true to their oath of allegiance, despite cruel jibes and insults from unthinking and uninformed people.

Perhaps the most outstanding person in the service of Canada in the west was known in the intelligence service only as "208." Today he is properly recognized as Major Stephen E. Raymer, J. P., an acting magistrate for Richmond, the beautiful municipality adjoining Vancouver at the mouth of the Fraser River.

Stephen Raymer was born in the city of Zagreb in Croatia, now a part of Yugoslavia, but then an unwilling province of Austria. He was of good family, and being particularly active and intelligent, made rapid progress at school. The Austrian government was trying to integrate the youth of the captured country. This was done by removing promising boys from their Croatian home life and influence and educating them in naval and military academies surrounded by Austrian boys. Young Raymer was selected to be one of these, and against his will was sent to school to train for the navy. He hated the Hapsburg dynasty, and the treatment of his fellow-students did more to embitter him. They usually referred to him as "Croatian pig."

He was graduated from the academy and was assigned to a war vessel as a midshipman. The experience did not improve his regard for the rulers of the Austrian empire. He spent his spare time in studying languages. When opportunity offered he joined the Sokol organization. This was a group formed, ostensibly for gymnastic training, but secretly to prepare for the overthrow of the Hapsburgs and the freedom of the Czech and Slovak peoples held in bondage. His sympathy with this movement was suspected, but he was a boy of promise. He might be moulded. He was taken from the navy and was sent to South America to be trained in the consular service, apart from all Croatian associates. When he landed at Rio there was no one there to meet him. He found his way to the consulate, just at the very instant that the consul chose to call from his private office to a clerk in the reception room, "Hasn't that Croatian pig arrived yet?" Raymer dropped his bag, rushed into the inner sanctum and landed a punch on the nose of the consul. That ended his career under the Austrian government!

Going to France he obtained a post as interpreter on a French liner running to New York. He now spoke the following languages; Serbo-Croatian, English, French, German, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Roumanian, Bulgarian, as well as a number of patois of these, and in several more he could carry on a conversation, but did not claim mastery.

In 1911 he came to Vancouver. He got a job as a newspaper writer on the German press, a language paper designed to keep the German people together as a unit. It was as such that I met him in 1912 when I was with The Vancouver Sun. There was some difficulty about that time in getting dependable interpreters in some languages at police headquarters. Steve was asked to break a language impasse on several occasions and gave such satisfaction that he was asked to accept a post as regular interpreter. He did so, for the tongues at his command. Malcolm R. J. Reid was chief inspector of immigration at Vancouver. A former school teacher, he was a well-informed, impulsive sort of a man with a high sense of duty. He saw Raymer at work in Magistrate Shaw's court, and a few days later enlisted his aid to do some interpreting. That started Raymer's association with the Canadian Intelligence Service, for Malcolm Reid was the "chief" of the organization in British Columbia. So it was that Steve Raymer was working for the protection of his adopted country before war broke out.

He remained with the German Press until it was closed down immediately after the outbreak of war. By that time he was serving in a dozen ways. In addition to his police and immigration work he was installed as an interpreter in the censor's office. I was turned down when I offered for service in August of 1914. I was told that I could not get overseas, as my category was too low. That first contingent was made up of men who were just about medically perfect. I wanted to serve, so I offered myself for intelligence service. Malcolm Reid accepted me and swore me in. He stipulated that I should stay with The Province, which I had joined the previous year, explaining that a man known as a reporter could poke around without exciting suspicion. He also told me to work with "208," who, to my surprise, proved to be my friend, Steve Raymer. So it came about that I learned a great deal about "208" and his work.

There follows five little tales about incidents of his activities. These I ran in The Province a few years ago, using his numerical alias. Now I am offering them again in permanent form, but with his consent, I am disclosing the identity of this particular undercover agent to whom Canada owes so much. There is only one addition. I have added two or three paragraphs explaining an exciting sequel to the story of "Von Bernstorff's Mail Bag." Otherwise the stories are as they appeared.

Following the armistice of November 11, 1918, Steve Raymer went to Europe where he was attached to the Serbian section of the Press organization there. He was also employed as a trusted messenger carrying despatches to and from Serbia, and played a part in the formation of Yugoslavia from the shattered Balkans. On one occasion the Italians tried to stop him going through that country. He was carrying important documents. He was at a little station and suspected that he would be stopped if he tried to go through. A train came along, with a British mail van, bearing the British Coat of Arms on its sides. It was hot, and the English sergeant in charge was sitting at an open doorway. The car was just getting under way when Steve ran and jumped head-first into the truck, calling out to the Tommy to hide him. This he did, and Steve went through Italy hidden under the mail bags from the Mediterranean.

Returning to Canada he took special courses at McGill University in economics, insurance and commercial law. Then he returned to Vancouver and opened a general insurance business with his stepsons. He left this a few years later to accept a post with the advertising department of The Sun.

When the second great war broke out in 1939, Steve offered his services again. He joined the Legion of Frontiersmen in which gallant corps he achieved the rank of major. He helped in many ways. He had been foretelling another war by Germany for years, and was called a "warmonger." In 1930 he was commissioned by the B.C. government to prospect for lumber markets in Europe. On his return he made a written prediction; that Hitler would succeed Hindenberg as Chancellor of Germany, and that within ten years Hitler would start a second world conflict. This time, he said, Mussolini would side with the Germans, and they would strike at Russia's "breadbasket," the Ukraine. He visited Hindenberg, and later talked with Hitler and was a guest at Pilsudski's presidential palace at Warsaw.

Now, Steve Raymer, who is above all a real Canadian, and his gracious and charming wife who has inspired him, are carrying on trying to find new ways to serve their adopted land which they have already helped to defend on two occasions.

GERMANY PLANNED CONQUEST

In the spring of 1914 an announcement from Berlin was carried by the official German press agencies, to the effect that a squadron from the German Pacific fleet would pay a courtesy visit to San Francisco on the occasion of the Fourth of July celebration of that year.

The press in Canada was not much concerned with the news item. It was occupied with the Krafchenko trial at Winnipeg, the Millard slaying in Vancouver, as well as the activities of the suffragettes in England and the possibility of civil war in Ireland.

But there were men in Vancouver who were interested in the doings of the German fleet. They had been looking forward to the German announcement. Behind that few lines of press release was a tremendous story of deliberate plotting; of international treachery and all the horrors of war.

For Germany planned to have her ships of war in Vancouver harbor when hostilities commenced.

The port of Vancouver was of even greater strategic value in 1914 than it is today. A map of the world shows its importance in those times, and especially before 1917 when the U.S. entered the war.

It was the bottleneck through which supplies went to China, Japan and Vladivostock; it was the channel through which cable communications were carried on with Australia and New Zealand, and in many other ways it was vital to the cause of the Allies. Germany realized this fully, and, as early as 1909, planned to take Canada's Pacific coastal points at the very outset of a war with the British Empire.

An elaborate underground organization was set up in British Columbia. It was complete with a governor-general; lieutenant-governors of several districts that were to be established; a military commander, a director of intelligence and a civil administrator who was to codify the laws of the province with those of Germany.

So confident were the Germans in the future of the province that large sums of German money came into the country for investment.

Such then was the background of a meeting called in February, 1914. To this gathering, which was held behind closed doors, Germans, loyal to the Fatherland, living in and about Vancouver, were summoned. Several hundred attended.

When the meeting opened, a spokesman stated that he had received word from Berlin that announcement would shortly be made of the proposed visit of the squadron of German war vessels to San Francisco. After spending a few days there the squadron was to proceed up the U.S. coast visiting Portland, Tacoma and Seattle.

When the word was given, Vancouver Germans were to make a concerted drive on Mayor T. S. Baxter and Federal member H. H. Stevens, to have an official invitation extended to the German fleet to spend a week in Vancouver harbor—dating from August 1.

So much was told to the Germans in the meeting held that February night. The possibility of war was not hinted. It was to be a patriotic movement and a gesture of goodwill. This was what the majority of the stolid Teutons believed.

But there was one man who held a different opinion. He was stationed at the door, and later became one of Canada's most efficient secret service men, known to his colleagues as No. 208. He was Stephen E. Raymer.

Forewarned, instead of the German fleet being invited to visit Vancouver for the outbreak of hostilities, late in July two Japanese ships of war—and Japan was Britain's ally then—paid a courtesy call to Vancouver, and were, with other vessels, off the shores of Vancouver Island when war broke out. The British cruiser Newcastle was also in the offing, as was the French cruiser Montcalm.

The German plans to take this coast were not abandoned, however. The Gneisenau, Scharnhorst, Leipzig and Dresden were off the American shores early in August.

They came up the coast, and on August 13th, the cruiser Leipzig was actually within the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. When, later, she was destroyed in the Battle of the Falkland Islands, the British obtained her log and chart of her course on this coast. This showed she was off Cape Flattery on that date.

She intended to enter the strait under cover of a fog that often hangs along the U.S. side of the waterway. The purpose was to get in beyond the arc of fire from the Esquimalt guns. But the fog started to lift, and the captain of the Leipzig did not wish to encounter not only Esquimalt's big guns but the two submarines that Premier Richard McBride had purchased.

It has been a custom of late years to laugh at the two submarines. But they were new vessels, constructed in Seattle for a South American government. They were up to date, and with experienced crews would and could have been effective weapons.

In connection with the presence of the Leipzig off the coast there is an interesting story told in Seattle. It is that a powerful tugboat was ordered to take a barge load of coal out beyond Cape Flattery. The captain was a former Canadian—a blue-nose skipper—who had become naturalized in United States.

He was given sealed orders that were not to be opened until he had passed out of the strait. Now it just happened that the captain strolled into the galley while holding the envelope containing his orders.

Just by accident the steam from the cook's kettle played upon the envelope and it opened. It was only natural that the captain should take a quick glance at the orders—just to see that the steam had not ruined the typing—before he closed the envelope again.

A peculiar thing happened; a sudden fog descended, and while the tugboat escaped it, the coal-laden barge piled high upon a submerged rock.

The Leipzig was short of coal when a few days later she put into San Francisco for a supply.

PRICE OF PEACE

Had Germany succeeded in winning the First Great War and been able to dictate a triumphant peace, Canada would have been torn from the British Empire to become a colony of the Reich.

So certain was the Kaiser that he was destined to rule over the Dominion that his war lords planned the manner in which they would administer the affairs of the country.

Long before the U.S. became a possible enemy, Germany had decided the Monroe doctrine, believing that before the might of her goosestepping legions the republic would not dare to challenge invasion of the continent.

German governors for Canadian provinces were named, while lieutenant-governors were selected for the military districts that were to be established after conquest. British Columbia was divided into several such areas. This fact was discovered with the arrest of one of these dignitaries under dramatic circumstances.

It was in 1915. I was doing what I could to assist Steve Raymer in solving a mysterious chain of circumstances surrounding the construction of a new type of machine gun. The young inventor had been threatened, and efforts were made to destroy the parts of the gun as they were constructed. Steve told me one day to carry on according to a plan we had devised. "I'll be away for three or four days," he said. "The old man is sending me up into the interior."

On his return he told me that he had gone to Kamloops, where another agent of the Dominion Police was waiting for him on the arrival of the train. He explained that suspicions were aroused about a German who was working in a sawmill in the Chase area. He was known as "von Mueller," and was evidently a trained military officer. He lived at a distance of several miles from the mill. He was an arrogant individual and did not consort with his fellow-workers at the mill. His residence was in a large log cabin, and he did not permit anyone to visit him; nor did any person wish to do so, for when he was at home a large Great Dane was allowed to run loose in the yard. When he was absent at work the beast was tied to the door handle.

Having breakfasted, the intelligence men drove to Chase, and having ascertained that von Mueller was at work, they continued on to his house. As the automobile came to a stop, a particularly large dog started to bark viciously at them and tug on the chain that fastened him to the door. The men reconnoitred the building. There was only the one door, and there did not appear to be any possibility of forcing entry through the two or three small windows.

"It looks as if we've got to kill you, old fellow," Steve said to the dog—"but it can't be helped."

"That's right," agreed his companion, "but by doing so, some humans may be saved."

Raymer drew his pistol and fired. The dog fell dead. It took a few moments to tug the big carcass aside and open the door with a master key. They entered a well-furnished sitting room. It was dominated by a life-sized bust of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Von Mueller certainly was not hiding his light under a bushel: he was loyal to his master. Raymer knocked the image to the floor where it broke into countless pieces.

The two investigators started a systematic searching of the dwelling. It was surprisingly productive. From one place they drew two uniforms; one the dress and the other the field garb of a colonel of a Prussian regiment. This was interesting, indeed, but not unexpected, for it was evident that the man was a German officer. There were other uniforms; plenty of them. They found clothing for a sergeant, a corporal and 16 privates; rifles, side-arms, ammunition, dynamite and fuse, and what they assumed to be a part of a machine gun. The place was a veritable arsenal!

It was now well on in the afternoon. "Come on," Steve suggested. "We'd better get back to the mill before quitting time." They did not wait to pack all the equipment and explosives. "Come on," and they raced the Ford car back to Chase.

Asking for von Mueller, they were directed to a tall, well-built man of military appearance.

"Come," said Raymer, "come with us, von Mueller, we want to talk to you."

The German stiffened to attention; clicked his heels and bowed from the waist. He accompanied them to the mill office. There was no necessity of questioning him, for no sooner had they got inside than the big fellow again came to attention. "I know what you want," he challenged. "It's all right. You can shoot me—go ahead, I'm ready to die for the Vaterland."

"Don't get excited," advised Raymer's colleague.

"I'm not excited," responded von Mueller. "You can kill me if you want to, but the Kaiser will avenge my death. He will be here in two months, for Germany is taking over Canada. The Dominion is to be the price of peace."

His captors looked at him, and for a full minute nothing was said. Then with a sneer, the German went on: "I don't mind admitting that I hold the commission as Lieutenant-Governor of the Kamloops district!"

Next morning von Mueller was admitted to the internment camp at Vernon. There he remained until after the war was over.

THE GERMAN MAIL POUCH

Luck is an important factor in intelligence work, but it would be of little value without the human attributes of quick wit, readiness to accept responsibility and act upon evidence presented by chance. Steve Raymer possessed such qualities, as he demonstrated in the matter of von Bernstorff's letter bag from the Orient.

One morning in the spring of 1916 Steve went down on to the C.P.R. dock where an Empress liner had just berthed from across the Pacific. He was attracted by three postal men in argument over a mail sack. One was insisting that it should be put aboard the Seattle-bound ferry that was about to sail. "We'll get into trouble if we don't," he predicted. "You know as well as I do that where it is obvious that a mail sack has been misdirected it must be put on the quickest conveyance to its proper destination."

"That may be," maintained another, "but this is different. We are at war, and I think it should be held for investigation."

"What do you think, Steve?" queried the third clerk.

Raymer took a look at the bag. His eyes opened wide. "It's mine," he exclaimed with decision. "I'll take care of it, and be responsible. I'll take it to the censor's office." It was a diplomatic mail pouch directed to Count von Bernstorff, German ambassador at Washington, D.C. Some bright allied agent or sympathizer at Shanghai had placed it on the boat for Vancouver instead of one for United States.

Raymer, an accomplished linguist, took the sack to the censor's office. It contained 364 letters. He started to go through them scrutinizing them carefully. Included in the contents of the bag were not only communications to the ambassador and members of his staff at Washington, but to individuals in various parts of the republic. The majority of the messages were written in code. These he bundled up to be forwarded to the decoding office at Ottawa.

All day long he was busy opening and reading letters. It was after midnight when he reached the last one. This was not in code, but in German. It was a letter from the Austrian consul-general at Shanghai to the Austrian consul at Chicago. It was translated as follows:—