| Fig. 41.—WALNUT CHAIR, | Fig. 42.—WALNUT SETTEE. |

| UPHOLSTERED. | IN petit point. PERIOD 1710-1720. |

| (In the Galleries of Waring & Gillow. Ltd.) | |

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Antique Furniture

Date of first publication: 1915

Author: Fred W. Burgess

Date first posted: Oct. 23, 2013

Date last updated: Oct. 23, 2013

Faded Page eBook #20131025

This eBook was produced by: David T. Jones, Delphine Lettau, Dianne Nolan & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| Fig. 41.—WALNUT CHAIR, | Fig. 42.—WALNUT SETTEE. |

| UPHOLSTERED. | IN petit point. PERIOD 1710-1720. |

| (In the Galleries of Waring & Gillow. Ltd.) | |

Much interest has been shown of late years in all things appertaining to the home surroundings of past generations. Collectors’ hobbies have multiplied, and things which have in times gone by been discarded as worthless have been placed in honoured positions as venerated curios.

Every piece of household furniture has had a beginning, and has either evolved from some very early object of domestic use, or it has at some period more or less remote been created to meet the requirements of a special need which has then arisen. It is very natural that every householder should wish to know more about his home, and the home comforts by which he is surrounded; and as he pursues his investigations he becomes more and more interested, for there is a veritable romance about most of them.

Many books have been written about furniture—mostly by enthusiasts who have confined their attention to a very limited range; indeed, none have hitherto attempted an exhaustive book of reference about the furniture of all ages and of all peoples. It has been felt, however, that there is a real need for a handy book of reference, one in which the vital issues in the stories of furniture are consolidated. In compiling “Antique Furniture,” and in gathering together reliable information about the furniture likely to come under the purview of the home connoisseur, it has been my aim to confine myself to what is calculated to be of real service to my readers. Such a book should need no introduction, for it ought to find a ready welcome from those who possess at least one or two pieces of old furniture, which have come down to them from former owners, as heirlooms, perhaps, yet without record of their actual age or of the names of their makers.

In bringing this volume under the notice of readers it is especially desirable to lay stress upon the “home connoisseur,” to whom “Antique Furniture” appeals, in that it is only the first volume in the “Home Con[vi]noisseur” Series, which is intended to cover the whole field of household curios. As each volume makes its appearance the value of each separate unit will be enhanced, and little by little other objects than bare household furniture will be discussed. It is, however, desirable to point out that “Antique Furniture” is complete in itself, as will be every other volume in the series, thus like the expanding bookcase the library will grow, and the delights of the collector and home connoisseur will be unfolded.

In preparing this work I have had access to many collections, as well as to public galleries, in which representative pieces are housed. None the less interesting has been my examination of isolated, and sometimes curious and antique, specimens in private dwellings, especially in old houses, where such pieces have been since they were first made. I have been fortunate in securing some excellent photographs, which have enabled me to reproduce a fairly representative selection of examples of the types of old furniture usually met with in “homes.”

My thanks are due to the owners of the pieces I have illustrated in this volume, and I gladly acknowledge their courtesy in giving me permission to do so. I would especially mention Messrs Waring & Gillow, Ltd., of Oxford Street, W.; Messrs Gill & Reigate, Ltd., Soho Galleries, W.; Messrs Mallett & Son, of Bath; Messrs Mawers, Ltd., of South Kensington; Messrs Phillips, of the Manor House, Hitchin; Mr A. Amor, of St James’ Street, S.W.; and The Hatfield Gallery of Antiques. I have also received some valuable information and illustrations from the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington.

The peculiar charm about old furniture—genuinely antique—fascinates those who study it; and my earnest hope is that this volume may be the means of adding to the ranks of those who wax enthusiastic about collectors’ hobbies, and that they may by the interest they take in everything that is old, help to increase that atmosphere of refinement which hangs about the environment of a “home connoisseur.”

FRED. W. BURGESS.

London, 1915.

Making the home—Changing conditions—The relationship between architecture and furniture—Ecclesiastical influence—The arrangement of collections.

There has ever been a halo of romance about furnishing the home, and the pieces of furniture belonging to a past age must always be associated with family life. The dwelling of man, from ancient British homes and far-off days to the present time of luxury and comfort, has always been the gathering ground where household necessaries and comforts have been found. Half the pleasure in possessing old furniture lies in the memories it revives, and the realism with which ancestral homes can be pictured. The home connoisseur points with pride to his possessions, and harps back to the “good old times” when his forbears commissioned some local carpenter or joiner to make them a chest, a chair, or perchance a buffet; and if his family cannot boast an ancient lineage he is content with pointing with pride to the “genuine Chippendale chair” or other object he secured at a bargain at some well-known sale.

The furnishing of the home has occupied the attention of young couples of different social grades for centuries. To each of them the uncertain sea of matrimony was[2] untried, but they were agreed that the joiner, and in more modern days the cabinet-maker, had first to be visited, for a house, however costly and pretentious, was not “home” until at any rate its rudimentary furnishings were installed.

In days gone by it was not possible to “furnish throughout,” and most of the homes from which old furniture comes were furnished by a slow process. House furnishing in the Middle Ages and even in Elizabethan times—the times from which come the older carved oak of which the owners are so proud—was chiefly confined to the wealthier classes. The common people had but scantily furnished homes, and were content with the rough stools and benches village carpenters could make. In the eighteenth century, when the middle classes were gaining ground, the making of the home took time; moreover, furniture was bought as the growing needs of the household required; and when the fortunes of the family increased first one new piece of more costly design and decoration and then another were added.

Furniture in the past was good, solid, and lasting; chairs, chests, cupboards, and bedroom furniture served several generations, and as each succeeding young couple took their toll from the old home, and completed their furnishing in newer style, the household goods became mixed. It is true in the larger and wealthier homes there were rooms furnished throughout in well-defined styles—some had been retained in their entirety for generations, and others had been fitted up by successive owners, thus here and there rooms were distinguished by the names of the styles in which they were furnished, such as the “oak room,” the “Carolean room,” or the “white and gold room” filled with Empire furniture.

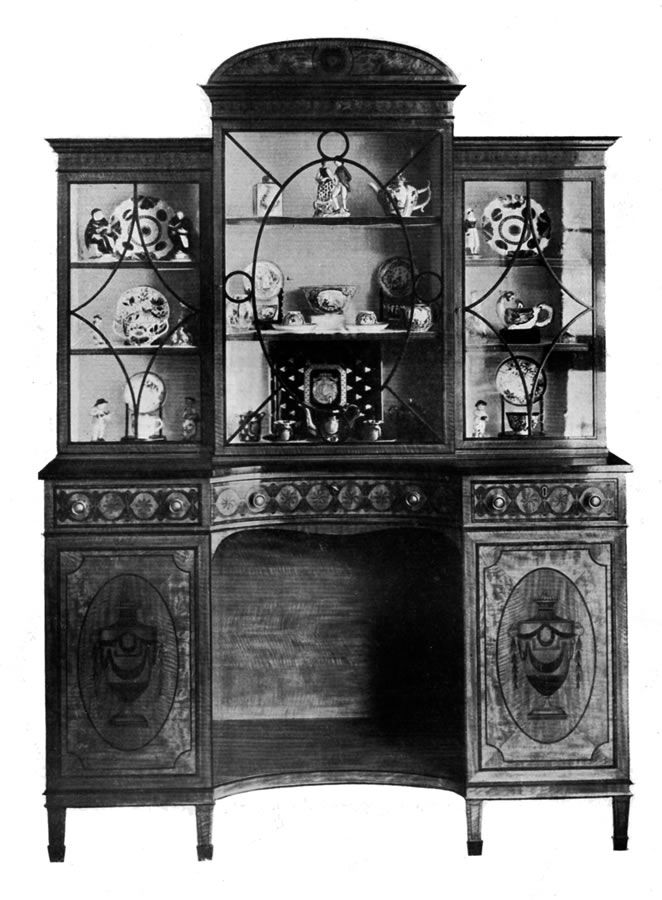

The furnishings of the home are seldom swept and garnished, for to part with family relics is breaking faith with those who handed them on with the remainder of their worldly possessions to their heirs. There were many who made special bequests of their furniture, and one of such would write in his will: “To my dearly-beloved nephew, John, I leave my mahogany bureau-desk and the tea china in the cupboard over it.” Can we imagine nephew John’s grandson or great-grandson parting with that beautiful Hepplewhite bureau-bookcase or cupboard full of priceless Worcester china because his dining-room or library is furnished in modern fumed oak or late Victorian incongruities? No! the home connoisseur values his family possessions.

The furnishings of the home contribute towards its comfort and happiness. To understand home furnishings, and especially those things the present day use of which differs from that to which they were originally put, is a laudable study. It is a delightful pastime, too, for interest grows as the research is continued, and sidelights are thrown upon the aim and objects of old-time furnishers.

In times when men had no settled habitations goods and chattels were few in number, and when huts of wattle and daub had been replaced by more permanent dwellings tribal wars and pillage prevented much increase of household goods. The chest or coffer was at hand when the overlord or chieftain desired to move on to his next domain, so that the produce of the estate could be consumed. There came a time, however, when the chest, although capacious, failed to accommodate the furniture of the home. The collector looks in vain for anything earlier than the wood coffer which gradually became a receptacle in which smaller boxes could be stored. To the chest were eventually added drawers, and from the chest evolved a chest of drawers, and perchance in later years a sideboard[4] or a cabinet, a cupboard, or some more important piece of furniture. In the history of furniture we see the story of the development of social life, and although the connoisseur is puzzled at times over what may be called transition pieces, these connecting links are exceedingly valuable, in that they help to fix more definitely the fully accredited periods and stages.

At first no doubt the sideboard was literally a board fixed against a wall for convenience; in common parlance, a shelf. To give it strength it had front legs; in time it had back legs added, and it became independent. This board, or buffet as it was called later, afforded the possessor of wealth opportunities of display, and it was on the buffet that the work of the pewterer and the silversmith was displayed. The same simple principle may be applied to the cupboard; a simple shelf, another shelf added, a door covering the contents of the two, a framework, and an extension, and the closed-in cupboard, at first plain, afterwards panelled, then carved, finally enriched with inlays, became from the simple shelf a thing of beauty, an ornamental and decorative piece of furniture such as collectors to-day value and admire.

As late as the fifteenth century even those who possessed more than the average wealth, and who had walled dwellings and securely guarded castles, had but few articles of furniture. The primitive stool or bench and the necessary trestle tables, were the chief objects supplementing the chest or coffer, and perchance the cupboard. Gradually ornament crept in, and the living-rooms became enriched with the work of the needle-woman and the metal worker. The painter added to the scenic splendour of the surroundings of a great feast, and the wood carver and the sculptor chiselled away at wood and stone. Here and there, as art progressed, the affinity between the architect and the cabinet-maker was seen.

As is well known, the earliest dwellings consisted of one large open hall. There were frequent signs of feasting, and the table groaned with an over-loaded board. The smith had contributed at an early date to the comfort of the dwelling, for he had fashioned andirons, and provided for the logs of timber to burn brightly on the hearth. The chimney had taken the place of the open flue, and the rafters were no longer blackened daily by smoke. Under somewhat more refined conditions it was possible for the furnishings of the home to be more elaborate. In the sixteenth century as yet there had been no idea of lightening the massive oak, although the plainer panels and beams were carved over. There was, however, a development going on in that bed-chambers were provided, and curtains divided off the sleeping apartments of the women from the men. Beds became common, but the furnishings of the bed-chamber and of the retiring-rooms were simple in the extreme in France, England, and in other countries which in the sixteenth century were coming under the sway and influence of the coming art.

It is said, however, that even as late as the beginning of the sixteenth century the necessity of transport still existed, and the furniture was made to take to pieces. Beds were jointed, and their columns took down. Tables were put up on trestles, but the “cabinets,” so called, were small, and could, on occasion, be enclosed in a large chest or a trunk. Even some of the chairs folded not unlike modern camp furniture. The hangings on the walls and the curtains running on poles could be taken down and removed. That seems to have been the position at the beginning of the sixteenth century, a fact which the student of furniture should remember, enabling collectors to recognise features in antique specimens which would otherwise be difficult to explain. When things became a little more settled, certainly towards the close of the[6] sixteenth century, the growing needs of a more domesticated home had been forced upon the architect, and the builder had provided accordingly. In many a turret, and in many a homestead, there were attics or garrets, the garret in the mansion being called “the wardrobe-room”; and it was to those places, sometimes containing secret chambers, that much of the house furnishings were taken when the household removed, and were perhaps absent for months at a time, to be restored to their original places when their lord returned. Even at that period the dwellings of the lower classes, the craftsman and the labourer, were furnished in a very primitive way, although it would appear that their settles and chairs and cupboards and dressers reflected somewhat the progress then being made in the higher branches of art.

It has been truly said that the furniture of the home has throughout the ages been subservient to the builder’s craft, and also that as civilisation spread, and the wants of the people increased, the builder and the architect have had to provide for the necessities of more furniture and a greater number of comforts in house furnishing and the surroundings of the home. The affinity between architecture and furniture has always been very close. The alliance is realised by the collector when he visits some of the more important palaces, and those buildings which retain their original schemes of decoration, and have but to a small extent been altered to suit so-called modern requirements. Nowhere is this affinity between architecture and architectural decoration, and the furniture used in such buildings, more clearly seen than in those wonderful palaces in France furnished by her kings and emperors. The history of French furniture of those days[7] seems to be bound up with the kings who were to a large extent patrons and supporters of art. A trip to Versailles even to-day shows the architectural influences which controlled and governed the makers of furniture and those luxuriant furnishings which give such a distinctive character to antique French furniture. A visitor to Versailles, who had the advantage of being conducted over the famous palace by the architect attached to the building, in very graphic terms described how realistic the scenes which had been enacted in the Revolution seemed to be. As an enthusiastic collector of furniture he began to understand more than ever not only the general effect of those magnificent pieces of furniture which were at one time assembled in the palace, but he realised that the whole Court atmosphere and influence in those days was such as to inspire the great artists, and to make them, as it were, run riot in the extravagance of their decoration.

In viewing those great apartments at Versailles it is no difficult matter to people them in imagination with royal personages, and obsequious courtiers in gorgeous costumes, and as fitting accompaniments in such scenes to recognise the furniture which would be appropriate to such surroundings. In these prosaic days, when viewing individual pieces of French furniture of the Empire period, we are apt to look upon their rich colouring, almost extravagant decorations and carvings and wealth of gilding, as being unnatural, superfluous, and out of place in the furnishing of any apartment intended for human beings to live in; but when viewed in the light of the architectural buildings which had to be furnished in keeping with their style, we see at once that anything less gorgeous would have been inappropriate. Thus it is that whether viewing architectural efforts of the French Empire period, or the furniture that once filled those apartments and halls, we must view them with full cognisance of the gorgeous[8] apparel of those days, and not from the standpoint of everyday clothing, and what would be suitable furnishings in a London suburban villa in the twentieth century.

Before entering more fully into the styles and types and individual characteristics of collectable furniture, there is an important influence which at all periods seems to have exercised control, and to some extent has given the lead to private needs and requirements, and to the house furnishings of every home throughout the ages, which must be taken into account. That influence may well be termed ecclesiastic. Whether we turn to the religions of the Orientals, the Jewish traditions of the East, to those later religions which for so many centuries influenced Eastern Europe, or to the stronger influences of the Christian religion, we find that this ecclesiastical influence dominates art and craftsmanship. The great interchange and spread of art through the touch of the western nations with the eastern during the Crusades had a marked influence on art. There were collectors of antiques, and especially of what we should nowadays call curios, even then. The cult of the collector seems to have been inborn in Englishmen, for some of the most treasured curiosities in our National Museums, if not actually furniture, but closely allied to house furnishings, are relics of the Crusades. The carvings upon the mother-of-pearl shell, the amulets and the talismans brought back by the Crusader, as well as the heraldic devices on the arms of the knights who fought in those religious wars, and borne by their descendants to-day, show traces of the influence of Eastern ideas; and the carver and the wood-worker of the Middle Ages used those emblems, and sought to discover in those foreign trophies something new with which to embellish[9] his early furniture. It is, however, from the great Gothic Renaissance of art and the influence of the monks of old that we get the strongest ecclesiastical inspirations.

It must be remembered that there was a time when even the vessels used on the cathedral altar, and later in the parish church, were not always exclusively employed for ecclesiastical purposes. Many of them were but the cups and tankards in daily use in the household, and the platters and alms dishes were either what were, or what had been, used for secular purposes. From this we understand more clearly the interchange of ideas, and the commoner use of what nowadays we should regard as sacred symbols, and inscriptions only suitable for ecclesiastical vessels, applied by the metal worker and the wood-worker on furniture and house furnishings. It is a mistake to look among the treasures which were originally made for the use of kings and wealthy ecclesiastics for types of the domestic furniture of any given period. It is equally as inappropriate for the collector of richly carved wood-work to seek for types of the chairs, reading desks, alms boxes, and the like commonly used in parish churches among the records and the examples associated with the great cathedrals and abbeys. There was always an appropriateness in furnishings, and in past years less of that extravagance and evident inappropriateness which is sometimes conspicuous even in model villas to-day.

Another very important point in the history of furniture which should be remembered by the collector is that a vast change has passed over the approved style of arrangement of museums during the last few years, and that change for the better should influence collectors in their selection of specimens and in their arrangement of the art treasures[10] they are able to secure from time to time. In the South Kensington Museums a great effort has been made to classify objects of interest. Different galleries have been apportioned to various articles. No doubt the system of classification could with advantage be still further extended.

In Lancaster House, the home of the London Museum, a chronological scheme of arrangement has been attempted, and the arrangement aims at giving the visitor an opportunity of realising the progress made in home life from the earliest times. There is the dug-out canoe telling of prehistoric men who inhabited the marshes near by the site on which London town was eventually to rise; there are rooms in which relics of Roman, Saxon, and early Norman London are shown in proper sequence; the household curios of mediæval, Tudor, and later days are beautifully arranged; until at last the furnishings of the present day are made evident, and the costumes as worn by Londoners represented. That, up to a point, is an admirable arrangement. It gives, however, but a very poor idea of the condition of the home of the Englishman when the articles of furniture collected by the connoisseur were in everyday use. The reproduction—or, better still, the reconstruction—of some well-known building, or of some of the chief rooms removed from houses now demolished, filled with the correct furniture of the period, just as may be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum, seems to be an admirable scheme of arrangement. The collector may be more cosmopolitan in his tastes, and may see much to admire in objects giving him a more casual survey of household furnishings, as they have been used in this country at different periods. There is, however, a strong plea put forward by those who, whilst connoisseurs of art and collectors of the antique, are believers in appropriateness of arrangement.

The modern architecture of to-day reproducing some old English styles, such, for instance, as the black and white Elizabethan dwellings, once such noted features in many English counties, seems to provide the collector of old furniture with ample means of display. Some of these rooms can be quite appropriately panelled with old oak, the richness of the linen folds of which would give the choicest setting to oaken furniture of the Tudor or Elizabethan periods. There are rooms, too, very appropriately designed to show off to the best advantage the work of Thomas Chippendale, and the later periods when the Brothers Adam, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton founded styles and designs which have been much copied, but never excelled. In rooms furnished in keeping with the furniture collected, not only are the objects of interest to the furniture collector housed in appropriate settings, but they may be enriched by the collection of contemporary ceramics, tapestries, needlework, and other antiques.

The term “house furnishings” is of a somewhat elastic character, and those who stop short at simple wooden furniture do not get the full delight of the more complete collector, who includes in house furnishings everything that has at any period been a necessary part of the domestic surroundings essential to home comfort. As an example it may be mentioned how very incomplete an old Welsh dresser is without its accompanying array of pottery and porcelain. There is something wanting in a scheme of arrangement of an old oak chest, cupboard, buffet, or similar antique without a few pieces of copper and brass or contemporary pottery to suggest its contemporary surroundings; and surely the floral decorations which delight the housewife to-day would look better in vases of priceless china and bowls with a wealth of colour, rather than in modern vessels, when antiques are displayed in the same room. Once again, the collector who revels in the[12] old walnut furniture of the reigns of William and Mary, and Queen Anne would fall short of his realisation of what a collection of furniture should be if it were unadorned by a few pieces of Delft, or the blue and white of the Kang-He Chinese period, at that time being imported. Collectable objects overlap, but the connoisseur may well decide to specialise on some given period, and when collecting furniture add appropriate supplementary objects.

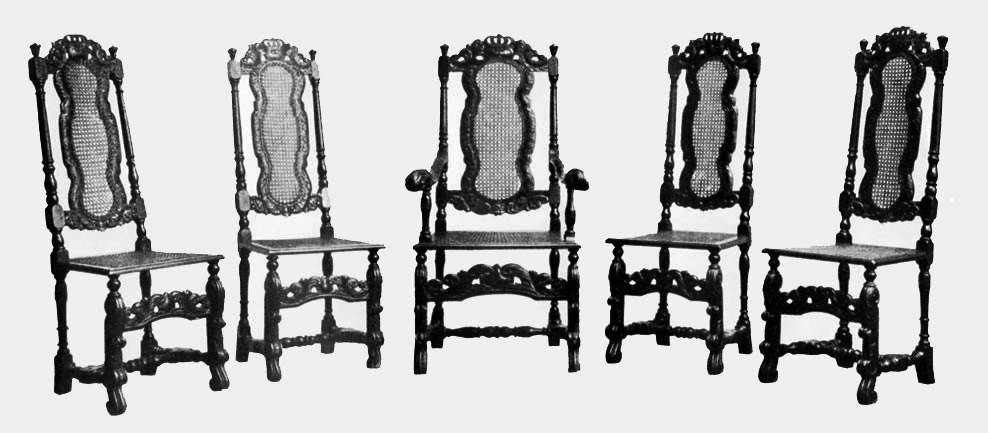

Fig. 1 represents how old furniture in a room suitably fitted up can be made very realistic, and how by providing an appropriate setting the value of antique furniture to the home connoisseur can be considerably increased. The illustration shows the interior of one of the rooms at the Manor House, Hitchin, in which there is some fine old Flemish panelling. The old paintings, hung on walls covered with wall paper of rich colouring, are in keeping. There are Jacobean caned chairs of several well-known types, and there is an excellent gate-legged table, in the centre of which is a branched candlestick suggestive of the days when such a room was lit up by candles. This photograph is reproduced by the courtesy of the owner.

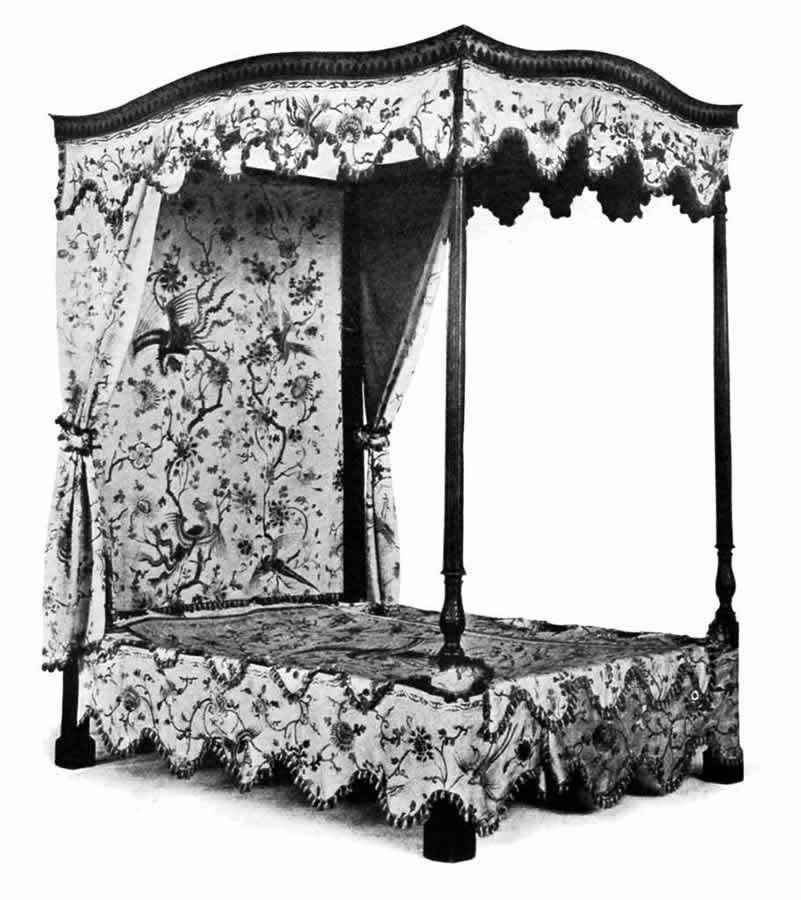

Fig. 2 is suggestive of the grandeur of the bedroom in all its glory when the four-poster was such a conspicuous object.

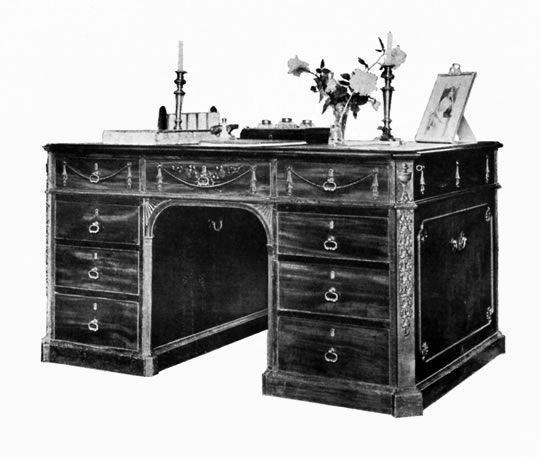

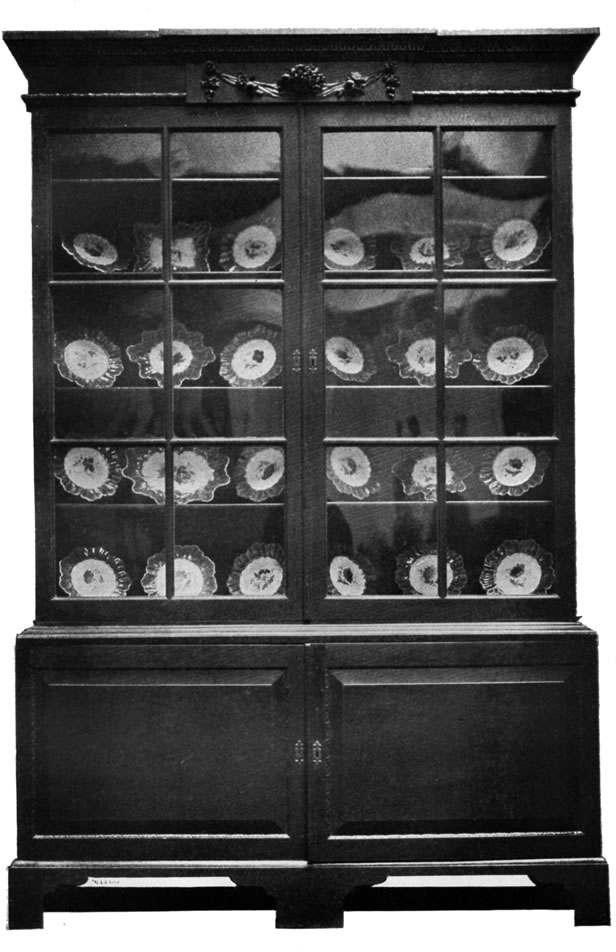

The furnishing of the home in the eighteenth century included some fine pieces of decorative furniture, such as the one shown in Fig. 3, which is a finely carved Chippendale pedestal writing table, on the top of which are appropriate homelike furnishings. This beautiful table was recently in the Hatfield Gallery of Antiques.

Well-defined styles—Gradual and yet complete changes—Some definite features.

Before considering in detail the furniture of the different periods in this country’s history, and tracing the evolution of household furniture from remote ages, together with the influences which have governed its progress, it will be well to point out briefly the styles which have predominated.

When the principal styles which have prevailed at different periods have been grasped, the home connoisseur is prepared for the more difficult study of the minor details of design, which mark different periods and the more gradual changes in intermediate styles.

From the very commencement there appear to have been well-defined styles. At first they were very primitive, and related chiefly to form. Then followed decoration and ornament; as these were controlled by a varying quality in the artist’s work there was less conformity to approved plans, and at each point when some one struck out on new lines there were varied interpretations of that style by copyists who followed it. There were, however, at every period plenty of followers, but few leaders. Therefore, when one man showed greater originality combined[14] with strength and determination of purpose, he forced a new style of ornament until it became general.

Again style progressed according to the circumstances of opportunity. Style changed as new materials came into vogue, because not only did certain woods, inlays, and veneers give greater scope to artistic minds, but the effect was different. In the Age of Oak there was plenty of scope for the strong and vigorous cutting of the carver; those were mediæval days, followed by the Renaissance, which gave many opportunities to the genius of the artist-carver. The Age of Walnut, which produced a smooth surface, yielded different results, and brought into being another style. Then when mahogany became known the carver of those marvellous scrolls, of which Chippendale was the chief exponent, revelled in the new material, which builders had rejected as “too hard to cut.”

Style was frequently controlled and directed by the affairs of State and by Court intrigues. The habits and customs of the people as they became more defined brought about the necessity for a new style. As an instance, the feeling of greater security produced by civilisation gave rise to many changes. This may be seen in the widening of the dining-table in the days of the Restoration, when it was no longer necessary from considerations of safety to sit at meat with back against the wall and sword in readiness. The table was then made wider, and it was placed in the centre of the room so that servants could move freely round it and wait upon the guests.

As will be seen in a subsequent chapter, the incidents of travel gave the cue to the artist who carved or painted the ornament upon chests and coffers—and especially marriage coffers—in early days.

At a still earlier period in Egyptian times the style of ornament evolved from the materials at hand, and from those substances which were brought to that country by native travellers and merchants. There was a plentiful supply of ivory and ebony for overlays, and artists who painted and ornamented wooden furniture found ready at hand a model to copy in the lotus flower growing on the banks of the Nile. Right along the line, through the history of the furniture trade, style was chiefly formulated and controlled by the prevailing influences and surroundings of the day; the materials selected were those at hand, although when there was a variety of materials those chosen were selected to produce ornament by contrast. New styles in furniture resulted from changes in material, and from altered design and ornament in other things. The architecture of the day influenced style in furniture, but outside, or what may be termed foreign, influence, often effected a complete change.

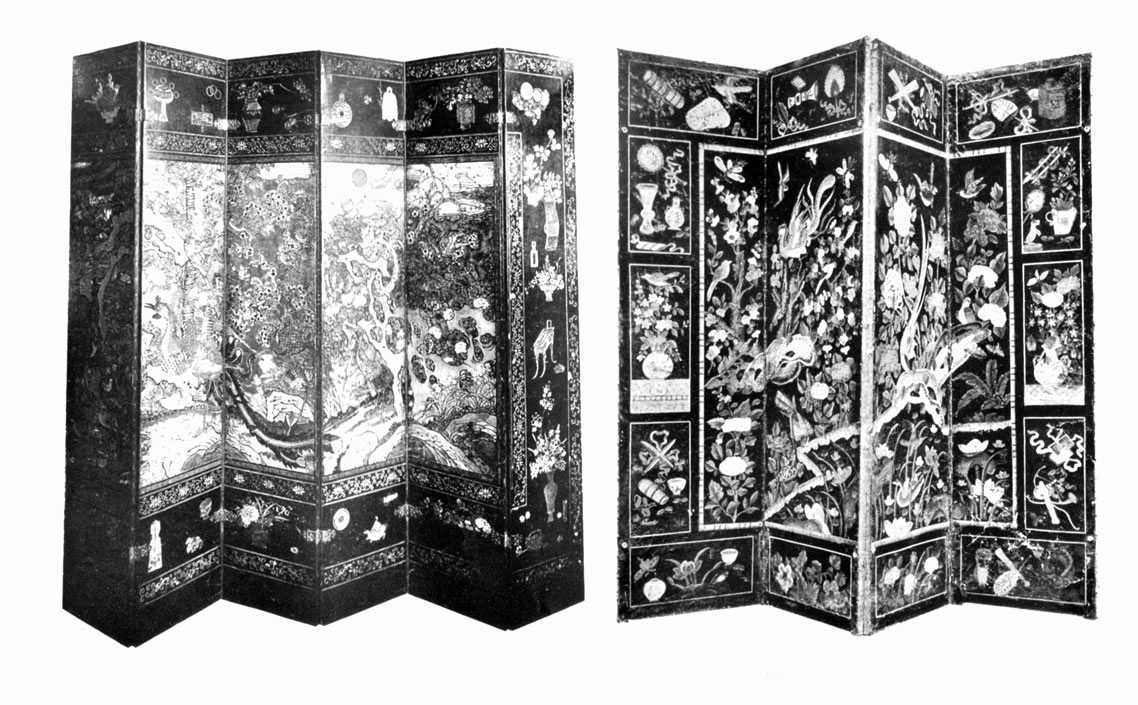

Style changed from the plainest of primitive furniture made for practical use, without any suggestion of ornament, to the more elaborate and extravagant styles, by a gradual process. At every stage in the development, however, there was a cause to which this change was attributable. At the time of the Commonwealth, after the downfall of the Royal cause, all things appertaining to the older order of things were swept away, and a severe style came into being. Again, at the Restoration, the carving as well as the fashioning of the new furniture was a strong contrast. At one time there was French influence, at another Italian; then for a time Eastern designs were popular, followed in due course by periods of carving, of inlays, and of painted design.

Sometimes there does not appear to have been any special reason for a change of style, other than that the change occurred to some one suggested from some common object with which the wood-worker would be familiar. Thus when an ornate oak panelling was desired to replace the plain panels, many of which had been painted after a fashion not then popular, two styles came into vogue; one the parchemin, cut in imitation of rolls of parchment upon rods, the other the linen-fold, which is said to be emblematic of the veil covering the chalice at the consecration of the Host in the Catholic Mass. There are some beautiful examples of this early wood-work at Hampton Court Palace and in other old buildings, although these styles were in vogue but a short time.

The dole cupboard would never have been made had it not been for the bequests and sympathies of religious houses and pious persons, who “remembered the poor.” There would have been no court cupboard or buffet if the habits of the people had not become more choice. Styles changed as times became more luxurious, and increasing refinement called for greater comfort. The hard wood seats and backs did not then satisfy, and chairs with cushions, and wing chairs with easy upholstered backs, were welcomed. The splendid decorative furniture of early French art palled in the reign of Louis XIV. The King wanted something suggestive of life and activity. He gave the signal for advance when he sent the famous instructions to his architect, Mansart, to whom he wrote saying, “Something must be changed. The subjects are too serious, and youth must be introduced into what is to be done . . . childhood must be widespread everywhere.”

The change in style in each individual piece of important[17] furniture is noted in the review given in chapter xxi. to chapter xxvi., and the changes in style appertaining to decoration and ornament in relation to furniture used in conjunction and combination are specially pointed out in chapters v. to xi.

The modern tendency to “furnish throughout” according to one style, which may be that of the present day or one of the older styles not altogether new, is no great novelty, for it has been practised in times gone by. The only difference is that in copying what has gone before we have to-day many styles from which to choose—all of the older ones are reproduced either as they were originally made or as modern adaptations—whereas in the past it was rare for makers to depart from the then prevailing style. It is well that collectors should remember that, as it gives greater confidence when buying antiques.

Reproductions of antiques, although not altogether unknown in the past, are the result of a modern craze.

The styles prevailing in this country at certain periods do not always coincide with the art of other countries at those times. In this work, although greater space has been devoted to English furniture, some attention is given to the antiques of other countries, especially of those continental peoples whose arts materially influence the craftsmen of this country. England has always received some lead from the artists and craftsmen of Italy, France, Holland, and a few other countries. The style of early English furniture was the result of the presence of the Romans in Britain during the first four centuries of the Christian era. That gave rise to a well-defined style, and others followed.

Certain characteristics to be found only in certain countries, or perhaps in some few towns, enable us to trace the evolution of style throughout the ages, and to note the adaptation of advanced workmen, either in the[18] purposes of ornament, or when some new piece of furniture or object of household decoration or utility was being fashioned. There are what are called by some primitive styles, the styles which remain intact when stripped of all superfluous ornament and superadded decoration. It is in the simpler designs and the ruder forms and ornaments that the purity of style is discovered. To take a few examples of the styles prevailing in countries where the earlier peoples were found, and especially those countries where primitive conditions prevail, we find in what is known as the Mahometan style, which emanated from the manner of life of the people, a strong kinship between architecture and furniture, and between architecture and actual necessity. The decoration of the oriental in its purer and earlier form has closer alliance with the inside of the dwelling-house than with the outside. In many dwellings of early Mahometan architecture, while everything was plain on the outside the interior was richly decorated. The most ornamental part of the buildings was found in the porticos surrounding the open courts. In the early furniture, as in the architecture of those countries subjected to Arabian influence, there are three different forms of arches found in arcades, doors, and windows. There is the pointed arch consisting of curves, slightly more elliptical than the Gothic style which developed in the West, found in Egypt and Sicily. In Persia and India the keel arch prevails, differing from the pointed arch in that the ends of the curves at the apex are bent slightly upwards. In Spain the horse-shoe arch prevails. In no place do we find a characteristic style retained so tenaciously as in Persia, for Persian art does not appear to have been influenced by contact with other nations. The strongest influence of foreign design upon Persian art is traceable to the Chinese porcelain, which was introduced into Persia in the sixteenth century. The Arabian influence spread[19] west through Spain, but it is probable that Arabian art had its origin in Persia, for it is well known that Persian workmen erected and decorated many Mahometan mosques. It was from such striking characteristics observable in the Mahometan style and Persian art that the grand Gothic of Western Europe evolved. Its characteristics in its full development are, of course, its pointed arches, pinnacles, and spires, and bold and lofty vaulted roofs and profusion of ornament. Many valuable specimens of the cabinet-maker’s art are enriched with pure Gothic designs, such, for instance, as coffers and cabinets which so closely resemble in design and style the architectural features of contemporary cathedrals and abbeys.

Gothic influence predominated in mediæval days, and French designs became interwoven with those of English origin in the sixteenth century, and intermittently in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Dutch influence and art, especially that of marqueterie, was seen during the reigns of William and Mary, and Anne. The consorts of English kings and queens were responsible for the introduction of foreign art, and for the encouragement of foreign artists, all tending to prevent any one insular style outside foreign influence becoming developed. Thus the wood-workers of this country have been peculiarly cosmopolitan, and they have in turn worked after different styles, favouring a variety of materials and finishes.

The home connoisseur thus meets with many varieties of style in family relics, and discovers side by side the wonderful lacquer cabinets from the Far East and the japan work of English artists; Chinese curios and useful pieces of English-made furniture ornamented in the Chinese style; beautiful French chairs in rich Genoa velvets, along[20] with English-made couches, beds, and cabinets, showing the strong influence of the days of Louis XIV. and the later time of Louis XVI. Collectors may well confuse genuine Dutch marqueterie with the marqueterie cases of grandfather clocks made in this country, just as they do the Italian carving of the Renaissance, and the English-made carved stands of Charles II., frequently surmounted by English lacquer cabinets.

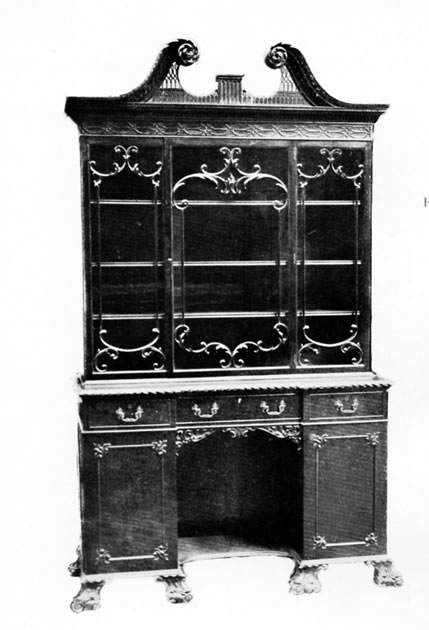

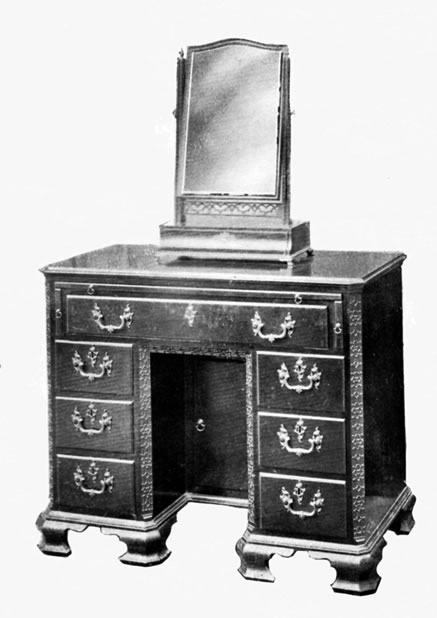

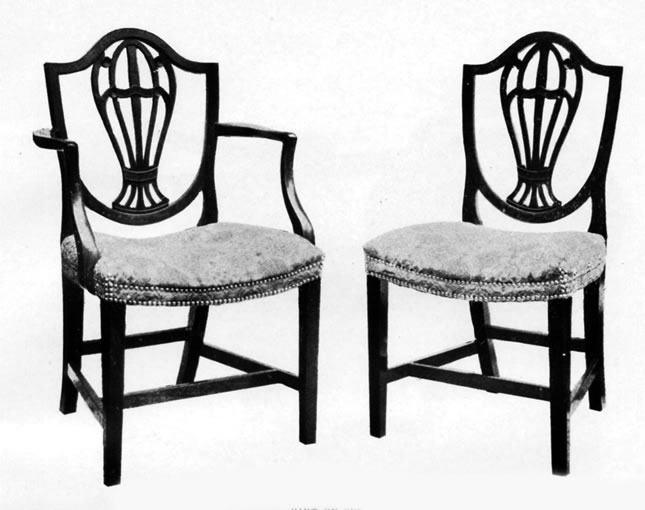

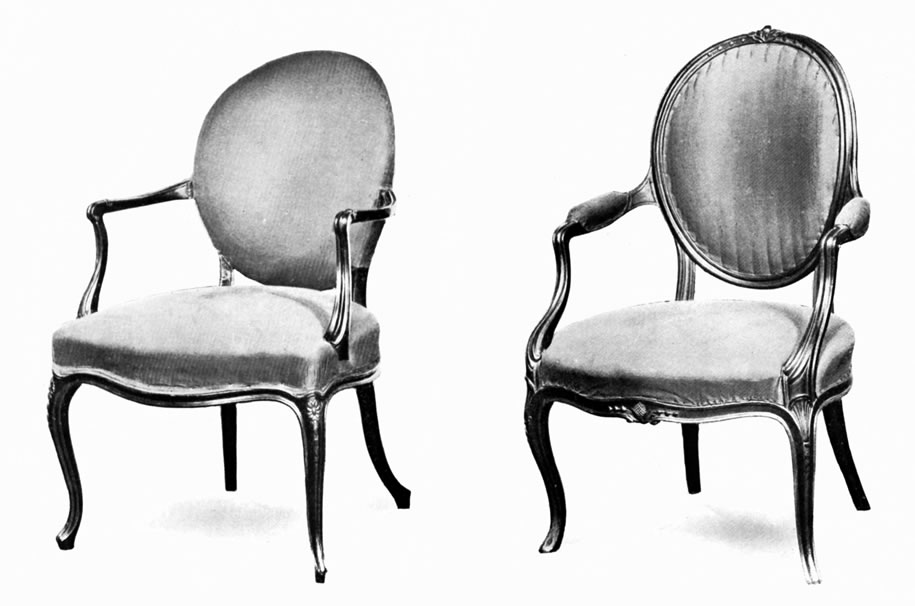

Some may desire a concrete example of distinctive evidence of style which can be easily separated. As an example then let us take the simple distinction in the styles in the chair backs of the eighteenth century. The walnut chairs of the period when Dutch influence was strong had a solid central supporting splat from the chair frame of the seat rising to the top of the back, which under Chippendale’s chisel was cut through and became ornamental, joined to its bow-shaped top. Both these splats, the solid and the decorative, touched the seat-frame. Then came the shield-shaped backs of Hepplewhite, which came down almost to the upholstery of the seat, but the point of the shield did not touch the wood-work; the backs of Sheraton chairs, square at the top and rectangular in form, had almost invariably an open space between the rail of the back and the seat. Yet these chairs were all upholstered, although the Cromwellian chairs had loose cushions!

English cabinet-makers were less dependent upon continental artists in the eighteenth century, when the makers and designers, some of whose work has just been mentioned, issued their own pattern books, although even the designs in the books published by such men as the Brothers Adam, Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton showed unmistakable signs of the influence of other schools. Thus Robert Adam travelled in Italy and became imbued with classic ideas; Chippendale took his rococo from French styles; the designs of Sheraton, perhaps,[21] showed more originality, although he was not free from taint. In subsequent chapters special attention is drawn to local styles which evolved from those more generally practised. Thus in due course a local style sprang up known as Irish Chippendale; the Welsh wood-workers evolved characteristic pieces of Welsh furniture, and as the outcome of their separation from the Mother Country the colonists and settlers in America gradually evolved distinctive styles, although partly based on old-world models.

The chief styles which are reviewed fully in subsequent chapters include as follows:—First, there are the older or primitive styles evolving from imitations of natural furniture, such as might be found in cave and forest; then follow the styles of the older civilised nations—Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine, and afterwards continental styles and those copied or adapted in our own country. Of these there are the Romanesque, followed by the Gothic; the early French school of Louis XII. and Henry II.; the French Renaissance; the Spanish Renaissance; and the later French Empire and regal styles and those of the Republic.

In England, following one another in proper sequence, there are the styles which succeeded the mediæval, mostly known by the names of the reigning sovereigns and their houses. These are commonly called Tudor, Elizabethan or late Tudor, Cromwellian, and Jacobean or Restoration styles. With the end of the Stuarts came the Dutch influence in the reigns of William and Mary, and Anne, followed by early Georgian adaptations and developments from which sprang the much-collected furniture distinguished by the names of the founders of specific designs, among them the Brothers Adam, Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton. Under those and minor distinguishing titles the collector separates his furniture and classifies his collections.

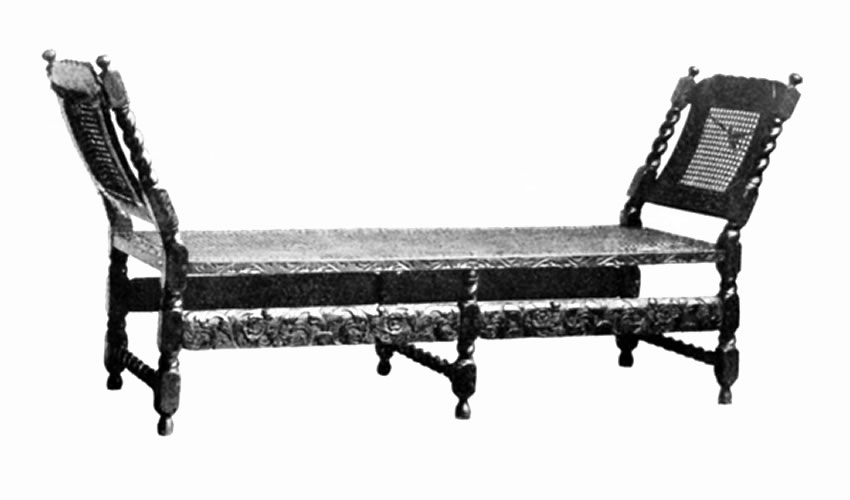

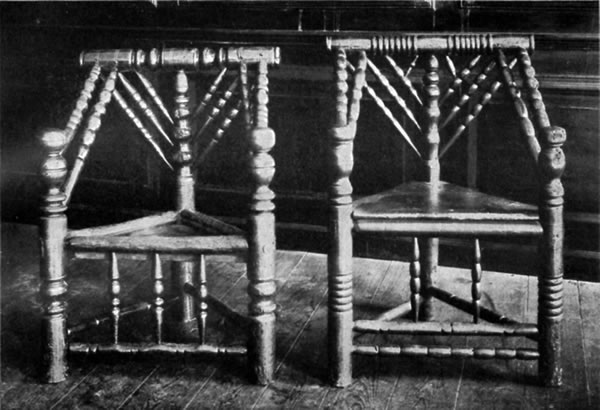

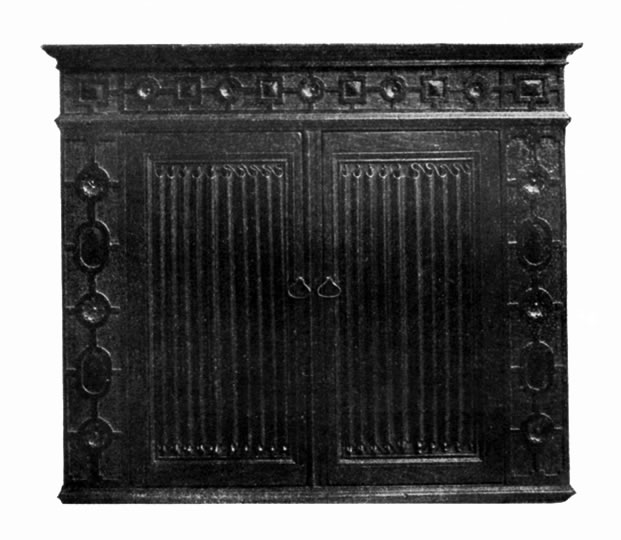

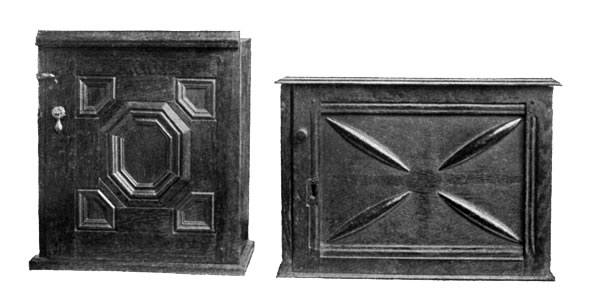

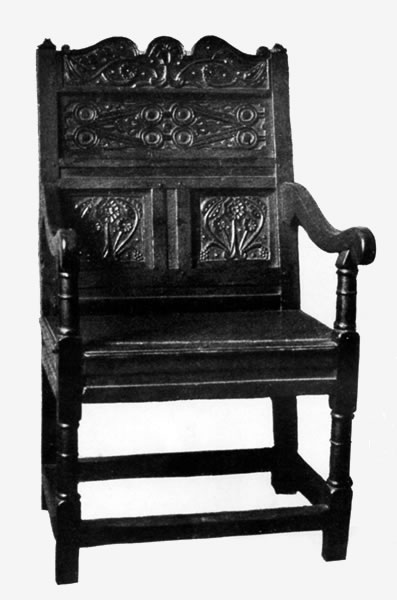

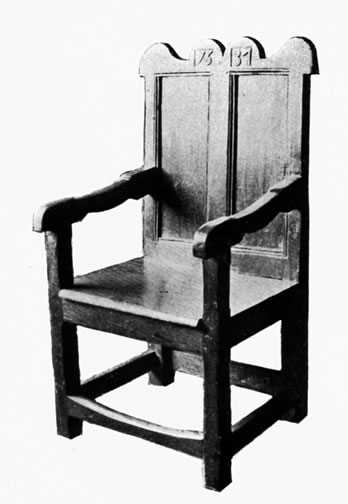

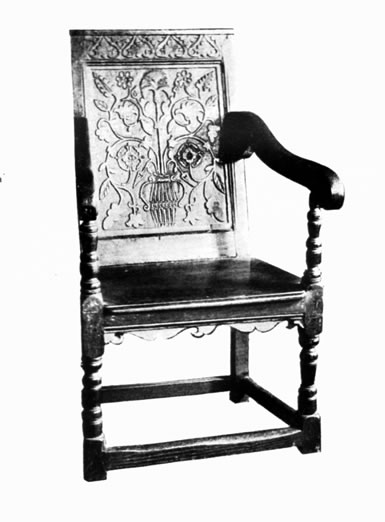

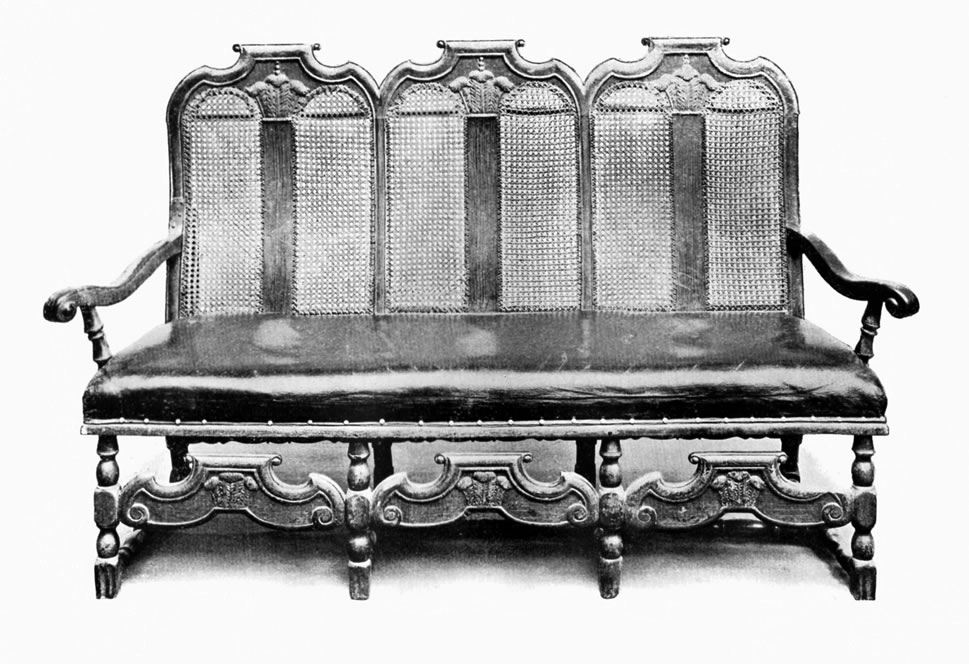

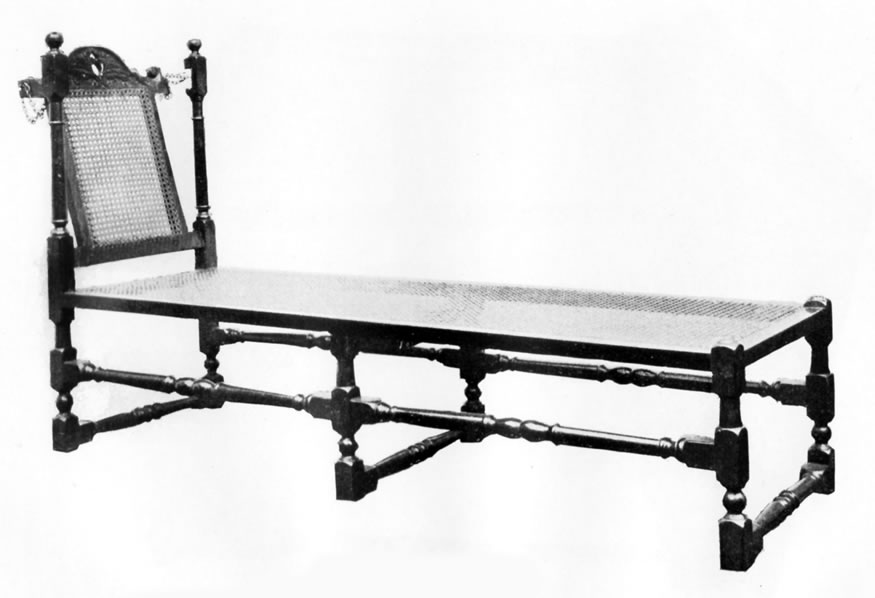

As indicating different styles of furniture, and showing the rapid change in the seventeenth century, during which period several distinct styles prevailed, the accompanying illustrations, Figs. 4, 5, and 6, indicate the progress made in wood-carving during a comparatively short time. In Fig. 4 are shown an oak cupboard and two chairs. The oak cupboard is of early seventeenth century workmanship, crude and yet decorative. It is a cupboard of the type which might have been expected to evolve from a chest or coffer. The two chairs are such as were in vogue about 1705, quite early in the eighteenth century, and show the early form of the cabriole leg (see chapter ix.). Fig. 6 represents one of the beautiful day-beds which came into vogue when the privacy of the bedroom was respected; the bed was then no longer in the living-room, and, therefore, not available as a seat or lounge, the chair-bed, or day-bed as it was frequently called, becoming a favourite piece of furniture and a comfortable lounge. The one shown in Fig. 6, of the period 1670-1680, is handsomely carved, the rail being exceptionally so. There are double ends, although in some instances the day-bed was made with only one (see Fig. 105). Before the seventeenth century closed more decorative carving had been applied to chair backs and a definite style evolved, the carved walnut Jacobean chair of 1689, illustrated in Fig. 5, upholstered in velvet, with fringed border, being an excellent example.

Eastern influence—Early Egyptian—Assyrian—Ancient Greece—Roman furniture—Pompeii and its treasures—Byzantine art—Anglo-Saxon furniture.

The furniture of the ancients is scarcely recognisable in collections and art galleries. Only here and there do we come across specimens which by some accident of good fortune have been preserved throughout the centuries. In these few isolated examples, however, we can realise that many of the nations possessed home lives, if such they can be said to have had, more complete in necessary comforts than we have hitherto imagined. In estimating what those necessaries consisted of, surrounding influences and the degree of civilisation attained, and especially the arts and crafts understood and practised, must be considered. In written manuscripts, picture paintings, in sculpture and pottery, are discovered not only the types of furniture in use in ancient countries, but their actual form, decoration, and colour.

It is due to religious beliefs and superstitions that many of the best preserved specimens have been handed on to us. The tombs around which so much superstition lingered for centuries, although rifled in modern times, were held sacred by the Ancients for many centuries, and knowledge of their contents was unknown until the present race of men, thirsting for greater knowledge of the past without fear of the consequences, took such relics[24] from their resting-places, and placed them in museums and in private collections. It is obvious that the art of past peoples regarded in the light of modern research and knowledge of art and science, is separated widely from art as it is understood to-day. That early art, so-called, is again subdivided into prehistoric, ancient, and barbarous. Everywhere we look for remains of early races, and for indications of their methods of living; and when we have discovered the relics they have left behind we are apt to judge of these people’s status in civilisation by the knowledge of this more enlightened age.

Commencing his chapter on prehistoric furniture the author of a very interesting work says:—“Mother Earth originally sufficed for bed, chair, and sideboard.” That is true indeed, for the most primitive furniture must have been the outcome of the dissatisfaction of man, who as he ate the more of the “tree of knowledge” was no longer content with Mother Earth as universal provider.

It is probable that all primitive nations left alone and untrammelled by outside influences advanced, although slowly, as time went on. The advance would be controlled and guided by their surroundings and gradually acquired habits, together with the progress suggested by their discoveries of natural resources. We know that was the case in our own country, for the relics of the so-called Stone Age are far behind those of the Bronze Age. From the Bronze Age onward there was always some communication with other tribes and with people of more advanced civilisation, and from that time the progress was more or less influenced by contact with others. The craftsmen of the Western World have from very early days received some inspiration from the influences of a greater civilisation eastwards.

It may be interesting to discover from the furniture collector’s point of view what the conditions prevailing[25] in this country were before that outside influence was felt.

In order to gain a clear insight into the actual domestic surroundings of early tribes, it is advisable wherever possible to secure reliable data from actual remains. During the last few years some important excavations have been made in England, resulting in an additional store of reliable knowledge of how the early inhabitants of Britain lived at given periods of history. Not long ago accounts were published of excavations at Hengistbury Head, in Hampshire, where a large number of flint implements, mostly of the Neolithic period, have been found. The barrows on the Head have yielded fine examples of Bronze Age pottery. Excavations have, however, revealed the site of an important settlement, showing that the people lived in huts made of wattle and daub, the floors being of beaten clay. As indicating domesticity and a degree of skill in weaving, it was found that large jars had been sunk in the ground, apparently for the storage of corn, and there were quite a number of loom weights and spindle whorls, but of whatever there might have been in the way of furniture, as we understand the term to-day, all traces had disappeared, notwithstanding that there were unmistakable indications of the occupants of the huts possessing some knowledge of the refining of iron and the working of bronze and tin. In the remains of such early days we have to be content with crude pottery, as indicating domestic furnishings.

The arts and crafts of ancient Egypt came from farther East. Biblical records tell of Assyria and Babylon, and of Judea and Persia. Modern discoveries confirm those accounts of an ancient civilisation with furniture and[26] luxurious upholsteries, such as were possessed by kings and their courtiers, but the richness of the palace furnishings of those Eastern potentates contrasted with the scantiness of the surroundings of their followers and dependents.

The Chinese developed an art almost entirely their own; contact with neighbouring countries spread its principles, and early influenced the arts and crafts of Europe. Ancient Greece caught the infection, and raised art to a higher pitch, by the better knowledge of human form possessed by Grecian artists, who added to Chinese art by more realistic and less conventional ornament.

Classic art spread; the artists of Greece were carried captive to Rome, so that they might teach the Roman workmen, and so the knowledge of art went West. Wherever Roman legions conquered the arts and crafts of Rome followed and were practised. Thus when Britain was occupied, the manufactures of this country were replicas of those objects with which Roman generals were familiar at home.

Notwithstanding the influence brought to bear by other nations, and the interchange of commerce which has at all times spread knowledge of commodities hitherto unknown, there have been always the modifying influences of environment, and thus styles have been created, and new requirements peculiar to certain peoples and countries have stimulated the genius of makers, and enabled them to set up national designs. Here and there new schools of design have been created as the outcome of national ideas. Thus there has been an independent art in India throughout the centuries, although in its application there are traces of early Greek and Mahometan influences, and in more modern days native art in India has been influenced by contact with the Western World. Near at home there have been strong evidences of national thought influencing[27] styles to a greater extent than outside influences. Thus in Ireland independent lines have been taken by craftsmen, and styles evolved quite different to those which have sprung into existence in Great Britain, although traceable to the same sources.

It seems natural that we should look for some guiding influence on the furniture trade among the numerous remains of ancient Egypt, and although the result of one’s research is somewhat disappointing, and the few examples possessed in the British Museum scanty in the extreme, there is abundant evidence that the people of Egypt in early times possessed far handsomer chairs and seats than other nations then in an advanced state of civilisation. As judged from those specimens in the British Museum most of the seats and stools used by the early Egyptians were without backs, although cushions seem to have been provided at a very early date. Folding stools of wood, richly inlaid, have been met with among the relics of ancient Egypt, some beautiful examples having been brought from Thebes. According to statues and other records during the later dynasties backs were added to the chairs of State. They were at first quite upright, but afterwards slightly sloping.

We owe the preservation of much that is interesting among the relics of ancient Egypt to beliefs not unlike some of those which caused the ancient Britons to put in the burying-places of their chiefs replicas of the common objects of everyday use. The Egyptians believed in a future state, and had a deep-seated faith in the literal return of the spirit to the body. It was for that reason that the Egyptians mummified their dead and provided actual supplies and furnishings, or in some instances[28] miniature copies of household necessaries, which they interred with the corpse. It is from these and the paintings preserved by that wonderful climate that more is known about the home life of the ancient Egyptians than of any other races of antiquity.

In the British Museum there are quite a number of chair legs and couch ends, but the examples in the Cairo Museum are far more numerous, and consist of a greater variety of form and ornament. In the British Museum there are a few examples of well-preserved chairs and stools, and from them we are satisfied that the Egyptians aimed at solidity, and to a certain extent at comfort. Their ornament was copied from the human figure, and those living organisms, animal and vegetable, with which they were familiar. To them their symbols were quite understandable, for they were drawn from Nature. The Egyptian artist was familiar with his much-loved Nile, and the plants growing on its banks. What more natural than that he should take the lotus flower and carve or paint it upon the chair he was fashioning. This he did, taking his model in its different stages of growth, from the bud to the opened flower. He placed a jar of reeds and palms by his side as he worked, and in his colouring he ever kept in mind the sand and the mud, baked hard and dry on the sun-kissed banks of the Nile.

In the tombs of Egypt we find the earliest examples, and many of these have been removed for greater safety to the Museum at Cairo and to museums in other countries. In the British Museum may be seen the remains of the throne of Queen Hatshepsut—looking very much like the frame of an old weather and time-worn chair, its legs not unlike the human leg in form—a valuable relic indeed, for it is said to be the oldest piece of furniture in the world. In the same case where it is displayed there is an inlaid stool in very good condition, and a square[29]topped taper frame or stand of painted wood. There are also some minor pieces and sundry remains of chairs and couches.

It is, however, from other resources of research that we are able to affirm with certainty that Egyptian furniture included folding stools and couches with seats of leather and plaited rushes, over which were thrown skins of panthers and other animals. The artists of Egypt and Nineveh understood painting, turning, inlaying, veneering, and cane work, and they were by no means far behind craftsmen who achieved fame in those arts thousands of years later.

In addition to the furniture from Egypt and Babylon there are interesting relics of the tools by which they were made, for under the foundations of many temples have been discovered the votive offerings of workmen; when laying foundation stones those who were to work upon the buildings to be erected thereon placed under them tools to propitiate the spirits of the temple, who were asked to assist the craftsmen who were working then, and who would work in years to come.

The furniture of Assyria has all perished, and it is only from sculptures that any of it can be reconstructed. Furniture pictured on paper only, or in the form of a reconstructed model, is of very little interest to the home connoisseur, and yet it is worth while to enquire into the furnishings of the homes of all nations, past and present, in order that the inspirations which have governed the artists of more modern days may be fully understood, for as we have seen the Far East and the art of Asiatic nations influenced Grecian artists, and from Greece art flowed westward.

From sculptures it would appear that the King’s throne in the palace of Nimrod, B.C. 880, was not a particularly comfortable seat. It was without back, but the seat itself was probably upholstered or covered with skins. This seat or chair was well built on square legs which ended in moulded tapering feet, and it was ornamental, the ram’s head being the chief design incorporated in the decoration. The Assyrians favoured cedar wood, but in Nineveh and Judea, at the time of King Solomon, ebony, teak, and Indian walnut were used, and they were frequently overlaid and inlaid with ivory. Biblical records of the furniture of Judea are especially interesting. Solomon is said to have possessed a bed of cedar wood, with pillars of silver and a golden bottom. The furnishings of a homely residence in the time of the prophet Elisha are recorded in Scripture, for Elisha was provided with a bed, a chair, a table, and a lamp in the guest chamber in which he was entertained.

In the Book of Esther the luxuriant upholstery and textiles of the Persians in the fifth century B.C. are referred to in the following terms:—

“White, green, and blue hangings fastened with cords of fine linen and purple to silver rings and pillars of marble. The beds were of gold and silver.”

The knowledge of Greek furniture comes from sculptures, paintings, and from the somewhat scrappy information of the furnishings of Greek houses, obtained from Grecian writings. Some of the most interesting bronze or wooden chairs from ancient Greece are depicted on the Parthenon frieze which may be examined in the British Museum. There are statues there, too, some of which are seated in chairs framed in square bars, the[31] horizontal pieces being morticed into the upright stays. The bars and frames of chairs and the footstools and pedestals used in Greece were often of cedar wood, inlaid with carved ivories. Representations of Greek furniture may sometimes be noticed on old coins and medals. The paintings on the vases in which the British Museum is so rich are, however, the most reliable. The vases were interred with the dead because of their belief in another world where life was to be lived on a higher plane. Scenes in domestic life were frequently pictured, and although the actual objects have perished there are indications of comfort and refinement in Greek homes. Upon one of the Hamilton vases there is a representation of a bed or couch on which were evidently cushions well stuffed and ornamental in texture. Carving, painting, turning, and inlaying were all used by Greek artists.

The Romans used chiefly cedar and veneered their furniture with olive, box, ebony, Syrian terebinth, maple, palm, holly, elm, ash, and cherry. They are said also to have used tortoise-shell, horn, and ivory in their more decorative inlays. Summarised, Roman furniture consisted of the curule chair, a square seat with X-shaped legs; the bisellium, or double seat; the solium or special chair for the use of the head or ruler of the household; footstools; scamnum, bench, the cathedra, a chair used by women; table (mensa); bed (lectus) and couch (lectus triclinium); and cupboard (armarium). Couches were frequently covered with tilts and curtains, arranged so that they could be carried as litters by slaves. Many articles of furniture were of bronze.

Among the historic furniture treasured by nations and religious bodies an especial halo of romance surrounds[32] the “chair of St Peter,” a solid square seat with pedimental back which is panelled with carved ivory. It was encased in bronze by Bernini in the fourth or fifth century. Legend suggests that the chair was originally in the possession of Pudens, an early Christian convert, and that it had been given to him by St Peter. This remarkable chair is now the throne of the Pontiff of Rome, and its age is undoubted, if not its legendary ownership.

We owe much to Pompeii for our knowledge of Roman civilisation, the fulness of which has only in recent years been realised. Although the chief objects of furniture which have remained uninjured by their long burial beneath the ashes of Pompeii and Herculaneum are of bronze, among the relics of those ancient cities are remains of the wood-worker’s craft. In researches among the remains of Pompeii it has been made clear that a much advanced art was practised by its workmen. There may be seen rows of houses and shops owned probably by citizens—well to do perhaps—not altogether by rulers and nobles. Therefore, the examples of ancient furniture found may be regarded as of the common order and not like some of the exceptional pieces which alone remain to us as examples of the art of some ancient countries. One of the finest pieces discovered is a table, evidently from a Pompeiian temple. The rooms in the houses in that ill-fated city were light and airy, some open to the sky. The upholsteries used are apparently in many instances luxurious, and were probably embroideries and rugs from Eastern looms.

Like the Chair of St Peter, representative of the earliest known European craftsmanship, Italy possesses another chair, known as that of Saint Maximian, at Ravenna, which dates from the sixth century in the Christian era. It is a remarkable piece of early craftsmanship, being overlaid with panels of ivory carved with scenes taken from the life of Joseph. It will be remembered that the Byzantine period began when Constantine removed his seat of empire to Byzantium, A.D. 321, and continued until the year 1204, when the city was taken by the Latins.

Customs which influenced manufacture as well as art were at work during the Byzantine period, for it was then no longer correct style to recline at meals; therefore the couch which had hitherto been used in Rome gave place to chairs at meals. In the decoration of furniture at that time the influence of religious beliefs was seen, for the Mahometans were forbidden to copy the human figure or form. Hence the absence of that which had been so conspicuous in Greek designs and architecture, and in the Roman furniture which had been influenced or wrought by Greek artists. In lieu of the realistic life and figure which had hitherto prevailed floral and geometrical designs were prominent when the Moslems ruled in Southern Europe, for they had destroyed the classic art they found in Constantinople at the time of its overthrow.

Anglo-Saxon art was derived from two sources—the Continent of Europe and from Ireland. Thus it was that the classic art of the old Roman Empire which[34] had prevailed in Britain during the Roman occupation passed away. A new inspiration came from France, Germany, and some other parts of Italy, and Anglo-Saxon workmen, by no means devoid of artistic tendencies, copied the new styles which were springing up in Europe whenever they had an opportunity of doing so. We can quite understand how when freed from the Roman rule they would discard the inspirations they had received from their conquerors, and if possible they would wish to make new departures. Reference has already been made to the independent line of thought prevailing in the Sister Isle. Celtic art was something apart, independently nourished, and even in Anglo-Saxon days moulded from other influences than those which governed English craftsmen. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that Irish cabinet-makers developed the style which became known as Irish Chippendale, rather from its similarity to English cabinet-work than to the source from which it came. Celtic art in the Anglo-Saxon period was sufficiently strong to influence British workmen, and we find that much of the jewellery and art metal work of that period was Celtic in design. Indeed, some furniture, by no means unimportant, indicates another origin to that which influenced so-called Continental inspirations. There is little or no Saxon furniture left. There are a few chests, it is true, mostly preserved in old churches. One of the most reliable examples is a chest of St Beuno, in Clynnog Church, in Wales. It is little more than a tree trunk hollowed out and bound with iron. There is another not unlike it in Wimborne Minster.

Just as the Chair of St Peter is one of the earliest examples of wooden furniture in Italy, so that of Venerable Bede is one of the earliest examples of English chair-making. Of other early chairs there is, of course,[35] the Coronation Chair, which was made about the year 1300, still showing traces of colouring and gilding. In the Pyx Chapel, in Westminster Abbey, may be seen a coffer which tradition says belonged to Edward II. An example of secular furniture is the Dunmow Chair, in which the winners of the Dunmow flitch of bacon are annually chaired according to the custom which began in the reign of Henry III. That chair, however, is of Gothic design and may possibly have once had a place in Dunmow Church.

The castle and its furniture—Early influences upon craftsmen—Symbolism and legend—Some examples.

In tracing the ancient furniture which once served the needs of the people we are brought face to face with the materials they had at hand. We have to realise that in all the early trades of this country local supply sufficed for local demand. It is true there were travelling pedlars, and merchants who sent their wares long distances from the seaboard inland by a packhorse train on mere trackways over hill and dale. Such methods of supplying the commercial requirements of village traders, and isolated dwellers in castle and hamlet were, however, practically useless to the workers in wood, and especially to the makers of furniture. The materials for such things were at hand, and wood-workers had access to the forests of Britain, which gave a plentiful supply of oak—the chief wood employed. Rooms were panelled, and furniture was made of well-seasoned timber as time went on, but not until years after the days of the accession of the Norman kings.

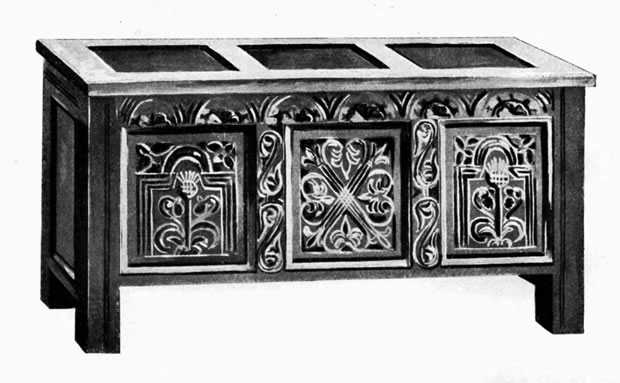

It is difficult to point out the exact time when the carpenter and joiner separated, for they eventually became two crafts, and the cabinet-maker no longer took part in builders’ wood-work. In quite early days men would differ in their abilities as craftsmen just as workmen[37] do now. The carpenter who hewed the beams for the wooden framework of smaller dwellings, and for the flooring of the upper rooms of castle towers, built the chest which was destined to be carried from place to place in mediæval migrations. He built it strongly to resist joltings over rough roads and forest tracks, but he probably called to his aid one who was more skilled than his fellows to carve those curious devices upon it. The panelled work and the smaller divisions in the coffer would be relegated to the joiner, the prototype of the man who was destined to become a cabinet-maker. The decoration of these early chests or coffers differs, according to the ability of the local craftsmen. At times it was merely a few almost meaningless cuts, or at most a fantastic symbol, at others it was really decorative. The artist in wood worked for his feudal lord, and sometimes very cleverly depicted the scenes with which he was familiar, and not infrequently represented episodes in which the chest was destined to figure (see chapter xxi.).

Some early examples of store chests and movable cases, which have been facetiously referred to as the prototypes of the modern pantechnicon van, were elaborately carved. Some of the scenes depicted represented knights with their men-at-arms on the march. Others the forest tracks then common in rural England, and in a few instances women are shown accompanying their lords, and the chest containing much of their household goods—the latter always finding a place in the caravan or cavalcade. The smith’s art does not appear to have been applied in conjunction with that of the wood-worker (with the exception of wrought iron hinges and hasps) until the thirteenth century. There are, however, a few earlier examples of iron-bound coffers which legend has it are of still earlier date, such, for instance,[38] as the treasure trunk in Knaresborough Castle reputed to have been brought over to this country by William the Conqueror. It is an ancient box with arched top and heavily banded, there being no less than eleven hinges with straps on the cover. There is another chest at Knaresborough known as the Castle Records chest, said to have been made originally for Queen Philippa, to whom the castle was presented in 1333. Most of the early mediæval furniture, of which there are any authentic records, has in some way or other been associated with feudal times, and in most instances probably belonged to the feudal lord.

To form some idea of the few pieces of furniture required in early mediæval days, it is necessary to picture the castle, tower, or occasional residence of the baronial lord in those days when England was in a somewhat disturbed state, for petty warfares between powerful chieftains were of common occurrence. Those were times when the furnishings of the home were of small account. They were rough and ready days, and the knights of old had no time or inclination to trouble much about the comforts of home life. The furniture used when the lord and his retainers were in residence was scanty indeed. It was necessarily so, for life in such a place, excepting perhaps in the larger and more important strongholds and the Royal residences, of which there were comparatively few, was uncertain—it changed frequently.

The great hall was in turn the place where feasting and sumptuous entertainment went on, the scene of battle and riot, the meeting place of conspirators, and often a deserted building left alone amidst the solitary grandeur of stone walls, turrets, and courtyards, outside of[39] which were woods and forests, often the dwelling-places of outlaws. We can picture in the mind’s eye the hall of feasting, with its simple trestle tables, ranged above and below the salt. They groaned often with the weight of meats, not always too choice. There was drink in abundance, and a somewhat noisy crowd occupied benches and stools, or stood in attendance upon those who were feasting at the table. The lord of the castle would sit in his chair of state, and his men-at-arms were ready to do his bidding. At such times the bare walls of rough stone were obscured by skilfully worked arras, hung on hooks driven into the walls for that purpose; pikes and bows, and perchance armour, would be piled in the corners and against the walls. The floor was covered with rushes, and as the feast proceeded some one or other frequently became quarrelsome, and misdirected blows often left marks upon the scanty furniture of oak. In a moment the scene might be shifted, for at the signal given by the watchman on the tower the feast would be hurriedly cleared away, and the few pieces of wooden furniture and vessels of metal and leather would be carried in haste up the stone stairs to a place of safety in the towers. In the hall, which had a few moments earlier been the scene of feasting, stern men-at-arms would await the attack of some stronger invading party, or they might man the walls, knowing full well that the great hall of the castle would be where they would make the last stand.

Again, from some urgent reason the lord and his family, and perhaps most of his retainers, would journey over rough roads to some far distant castle. On those migrations the walls were stripped of their tapestries, which were bundled into the chests, soon to be taken along with the cavalcade, and for a season the strong walls of the mediæval castle would be left almost as[40] the masons had left them. With such conditions prevailing in the residences of the nobles we can well imagine that the homes of the retainers, mere mud and plaster shelters within the walls of the outer keep or clustering round them for protection, would be scanty indeed in their furnishings. Such conditions explain the reason why there are so few remains of the earlier mediæval days in England left, and that this period in English cabinet-making is only represented by a few chests and coffers, and here and there by an old chair preserved because of some special interest which clung to it.

The so-called historical chests and seats other than purely ecclesiastical furniture are limited in number, and of the few pieces, the authenticity of which is proved, scarcely any are without evidence of having been added to or restored in later days.

In the earlier mediæval days there was a sharply defined line between fixed and movable furniture. The connection between the architect and the furniture maker was then very real, for the man who worked upon the interior wood-work, and as time went on endeavoured to make the bare rooms of a mediæval castle more homelike, likewise erected the less portable fixtures and the rough benches (some of which were afterwards carved), and no doubt made the oaken trestles and loose table tops. When we come to search for examples of furniture of that period the result is disappointing, for the little there was has long ago, with few exceptions, been “chopped up.”

In ecclesiastical buildings some few pieces have survived, but domestic furniture of English make dating from mediæval days is extremely rare. The Victoria[41] and Albert Museum, at South Kensington, where there are large galleries full of old oak, seems to be the place where one would search for English furniture of olden time; but while the Museum possesses some excellent examples of contemporary art on the Continent of Europe there are comparatively few of very early English manufacture. The collector, therefore, has to be content with those few examples, and comparing them with mediæval furniture of other nations thereby discovers as far as possible the few characteristic English “trade marks.”

The architectural connection between the builder and the furniture maker is still more apparent, as mediæval art advanced, for then the influence of Gothic architecture and style was supreme, and the wood carver was taught to apply that style of design to his works. The “house carpenter” rarely restricted his efforts to furniture, correctly so called, for he worked upon statues, busts, masks, and figure subjects which were applied alike to fixed and portable furniture. The decorations of the interiors of ecclesiastical buildings and mediæval castles consisted of carved ornament, and the same designs were cut upon the solid oak frames or stiles and the panels of chests and settles. Some of those carvings in their earliest use were supports and necessary to architectural designs, but not always so in furniture. In those early days it should be noted that the interior of chests, cupboards, and the like was always plain. The carved ornament was applied to the exterior, whereas in later days much attention was given to the interior of coffers and cabinets.

It was the Gothic perpendicular in architecture that had such a far-reaching influence upon furniture designers, for at that time architectural carvings became upright, and in that form were more readily applied to furniture; carving seemed to be the most appropriate decoration.[42] In reference to the ornamental carving of the later mediæval houses it has been pointed out that although castles, manor houses, and most of the churches and ecclesiastical buildings were of stone and brick, the dwelling-house was chiefly of timber. The timber beams gave abundant opportunity to the decorative carver, who made use of the corner posts and lintels as fitting places for the use of his chisel. Entire towns and villages were built in this way, and in some places entire streets presented a gallery of carvings, and in the fifteenth century the wood-work of the interior had become a reflex of the exterior.

Among the architectural features of mediæval days fine Gothic open roofs have been much admired, especially when the change to the perpendicular came. There is, however, one remarkable example of the time before the perpendicular had become general. It is the roof of Westminster Hall, which was reconstructed in 1399.

Although old houses of this early period are fast disappearing, attempts are being made to retain especially interesting buildings as show places, and where that is not possible considerable portions of carved exteriors are being removed bodily from old houses to the more important museums. In the Victoria and Albert Museum there are some splendid carved beams, and others showing the opportunities which the intersection of the beams gave to the wood-carver of applying simple ornament in relief. Where the beams met he added bosses, and then carved them with leaf ornament, or shaped them as shields upon which the family arms could be carved or painted. These ornaments were in time appropriated by the furniture maker, and the root idea is traceable throughout the ages which followed.

As it has already been suggested, ecclesiastical influence in the Middle Ages was so great that it controlled—indeed[43] it taught and perpetuated—art. The church Gothic of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries has always been much admired for its plain severity, although the artists of the fifteenth century achieved more lifelike and realistic work. The “tabernacle” style of fully-developed Gothic began in the fourteenth century, and its influence remained until Tudor days, as may be seen on mediæval coffers. The canopied stalls of cathedrals and abbeys were taken as the designs from which to carve the fronts of muniment chests, and the same men who worked for laymen would seek their inspiration in the church to which they were attached.

The grotesque carvings on bosses, the clever masks on the walls of mediæval castles, and the ornament on the more portable furniture, were not without their parallel in the grotesque carvings with which the monks delighted to cover the stone and wood of abbeys and private churches. Many of the monks (often skilled craftsmen) were comical old fellows; very wonderful and even dreadful were their conceptions of the pains and punishments of mortal man. As time went on, however, the plain severity of the seats (if any) for the common people, gave place to the more ornate, and the tediousness of the long hours of service in churches found some relief at the hands of the wood-carver. The miserere seats, of which there are such fine examples in Henry VII.’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey, are often pointed out as having tickled the humour of the carver, and induced him to design the most grotesque and sometimes ridiculous characters he could think of as ornaments (see “Miserere seat” in Glossary).