A Field Book of the Stars

|

In the compilation of the volume Star Lore of All Ages, a wealth of interesting material pertaining to the mythology and folk-lore of the sun and moon was discovered, which seemed worth collating in a separate volume.

Further research in the field of the solar myth revealed sufficient matter to warrant the publication of a volume devoted solely to the legends, traditions, and superstitions that all ages and nations have woven about the sun, especially in view of the fact that, to the author’s knowledge, no such publication has yet appeared.

The literature of the subject is teeming with interest, linked as it is with the life-story of mankind from the cradle of the race to the present day, for the solar myth lies at the very foundation of all mythology, and as such must forever claim pre-eminence.

Naturally, there clusters about the sun a rich mine of folk-lore. The prominence of the orb of day, its importance in the maintenance and the development of life, the mystery that has ever[vi] enveloped it, its great influence in the well-being of mankind, have secured for the sun a history of interest equalled by none, to which every age and every race have contributed their pages.

In the light of modern science, this mass of myth and legend may seem childish and of trifling value, but each age spells its own advance, and the all-important present soon fades into the shadowy and forgotten past. It is therefore in reviving past history that progress is best measured and interpreted. The fancy so prevalent among the ancients that the sun entered the sea each night with a hissing noise seems to us utterly foolish and inane, but let us not ridicule past ages for their crude notions and quaint fancies, lest some of the cherished ideas of which we boast be transmuted by the touch of time into naught but idle visions.

It is therefore important for the student of history to study the past in all its phases, and whatever can be brought to light of the lore of bygone ages should have for us a charm and should find a place in our intellectual lives.

W. T. O.

Norwich, Conn.

The thanks of the author are due The Macmillan Company, and Henry Holt & Company, for permission to use much valuable material from their copyrighted publications; and also to Professor A. V. W. Jackson, Mrs. J. R. Creelman, Mr. Leon Campbell, and the Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, for rare illustrations.

| PAGE | ||

| I.— | Solar Creation Myths | 3 |

| II.— | Ancient Ideas of the Sun and the Moon | 35 |

| III.— | Solar Mythology | 53 |

| IV.— | Solar Mythology (Continued) | 91 |

| V.— | Solar Folk-Lore | 119 |

| VI.— | Sun Worship | 141 |

| VII.— | Sun Worship (Continued) | 163 |

| VIII.— | Sun-Catcher Myths | 205 |

| IX.— | Solar Festivals | 227 |

| X.— | Solar Omens, Traditions, and Superstitions | 253 |

| XI.— | Solar Significance of Burial Customs Orientation | 267 |

| XII.— | Emblematic and Symbolic Forms of the Sun | 287 |

| XIII.— | The Sun Revealed by Science | 311 |

| Bibliography | 329 | |

| Index | 333 |

| PAGE | ||

| Aurora | Frontispiece | |

| From the drawing by Guido Reni. | ||

| Photo by Anderson. | ||

| The Days of Creation | 4 | |

| From the drawing by Burne-Jones. | ||

| (Permission of Frederick Hollyer.) | ||

| The Days of Creation | 8 | |

| From the drawing by Burne-Jones. | ||

| (Permission of Frederick Hollyer.) | ||

| The Nimbus-Crowned Figure (Mithras) | 48 | |

| (Courtesy of Professor A. V. W. Jackson and The Macmillan | ||

| Co.) | ||

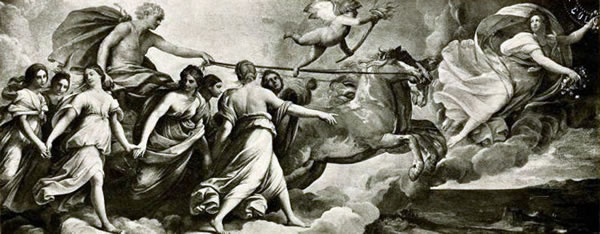

| The Horses of the Sun | 58 | |

| From the sculpture by Robert Le Lorrain, Imprimerie | ||

| Nationale, Paris. | ||

| Photo by Giraudon. | ||

| Apollo and Daphne | 66 | |

| From the photo by Anderson from the statue by Bernini, | ||

| Gallery Borghese, Rome. | ||

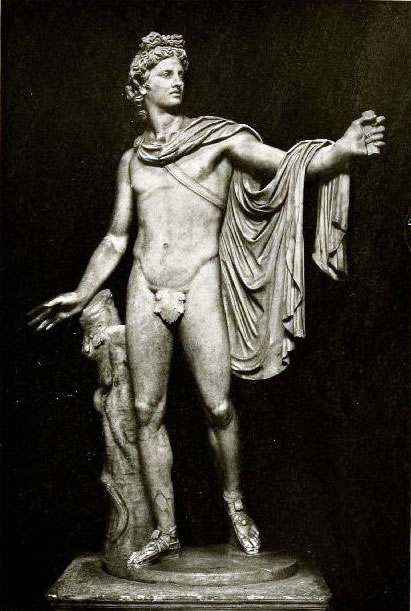

| Apollo Belvedere | 68 | |

| From the photo by Anderson, Museum of Vatican, Rome. | ||

| Kephalos and Prokris | 78 | |

| From the drawing by Guido Reni. | ||

| [x] | Photo by V. A. Bruckmann. | |

| Saint Michael | 124 | |

| From the photo by Anderson of the drawing by Guido Reni. | ||

| Isle of Sun, Lake Titicaca, Peru | 128 | |

| (Courtesy of Mr. Leon Campbell.) | ||

| Inca Ruins, Isle of Sun, Lake Titicaca | 130 | |

| (Courtesy of Mr. Leon Campbell.) | ||

| Ruins of the Incas’ Bath, Isle of Sun, Lake | ||

| Titicaca | 132 | |

| (Courtesy of Mr. Leon Campbell.) | ||

| The Temple of Jupiter, Baalbek, Syria | 148 | |

| Copyright by Underwood & Underwood. | ||

| The Delphic Sibyl | 172 | |

| From the photo by Anderson from the painting by Michelangelo, | ||

| Sistine Chapel, Vatican. | ||

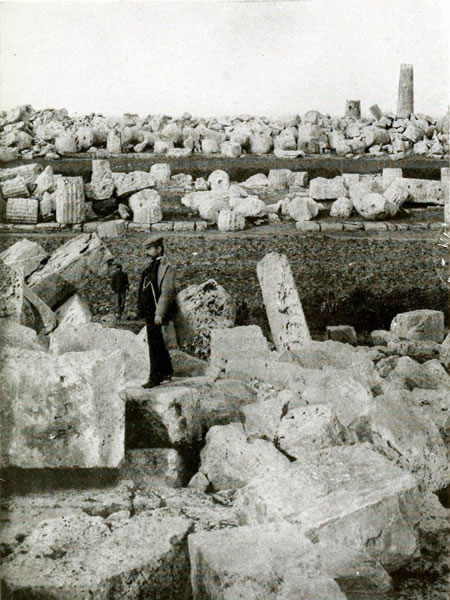

| The Ruins of the Greek Temples of Hercules | ||

| and Apollo, Selinunte, Sicily | 178 | |

| Copyright by Underwood & Underwood. | ||

| The Ruins of the Temple of the Sun, Cuzco, | ||

| Peru | 182 | |

| (Courtesy of Mr. Leon Campbell.) | ||

| The Ruins of the Temple of the Sun, Cuzco, | ||

| Peru | 184 | |

| (Courtesy of Mr. Leon Campbell.) | ||

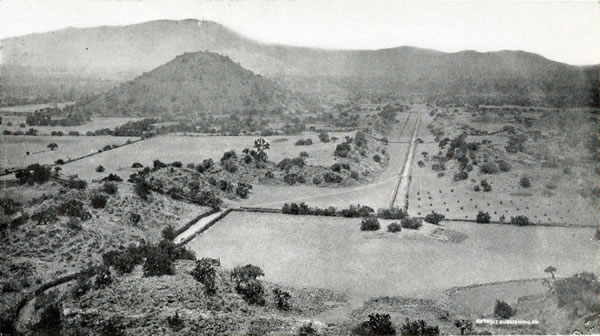

| The Pyramid of the Sun, San Juan Teotihuacan | 186 | |

| From the photo by Detroit Pub’g Co. | ||

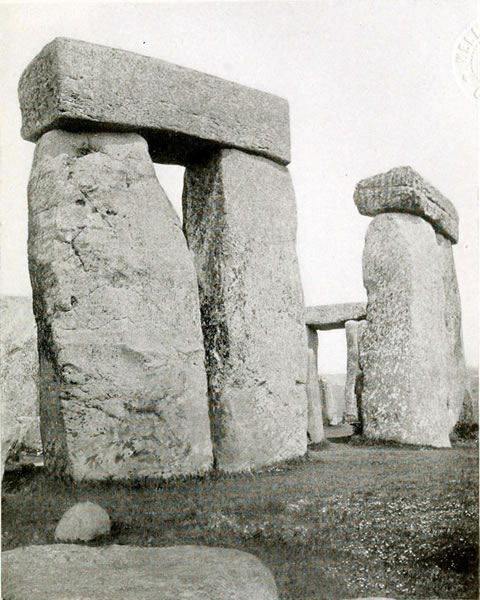

| Stonehenge, England | 198 | |

| Copyright by Underwood & Underwood. | ||

| Joshua Commanding the Sun | 220 | |

| Mosaic S. Maria Maggiore, Rome. | ||

| [xi] | From the photo by Anderson. | |

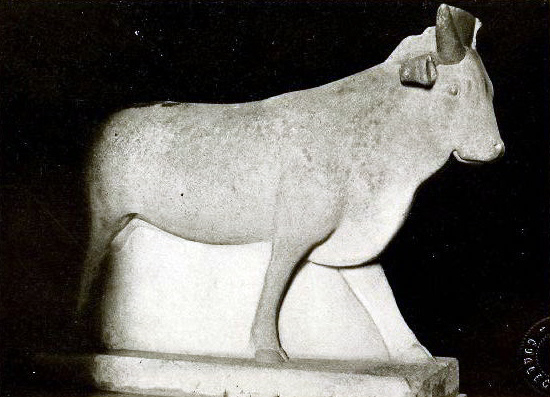

| The Bull Apis, Louvre | 240 | |

| Photo by Giraudon. | ||

| Medicine Lodge Sioux Indian Sun Dance | 258 | |

| From the photo by Mooney. | ||

| (Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American | ||

| Ethnology.) | ||

| The Maypole Dance | 260 | |

| Copyright by Underwood & Underwood. | ||

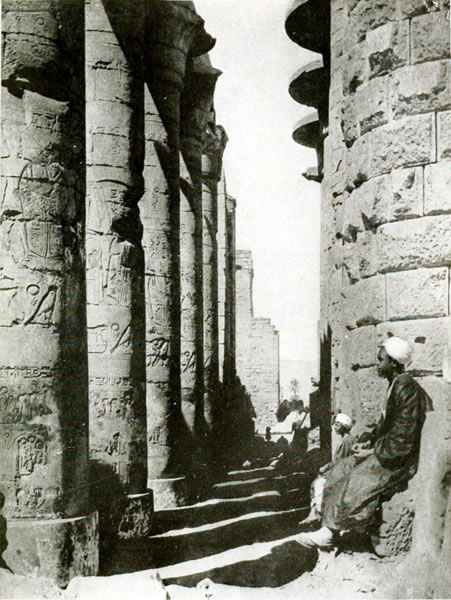

| The Temple of Amen-Ra, Karnak, Egypt | 274 | |

| Copyright by Underwood & Underwood. | ||

| The Gateway of Ptolemy, Karnak | 292 | |

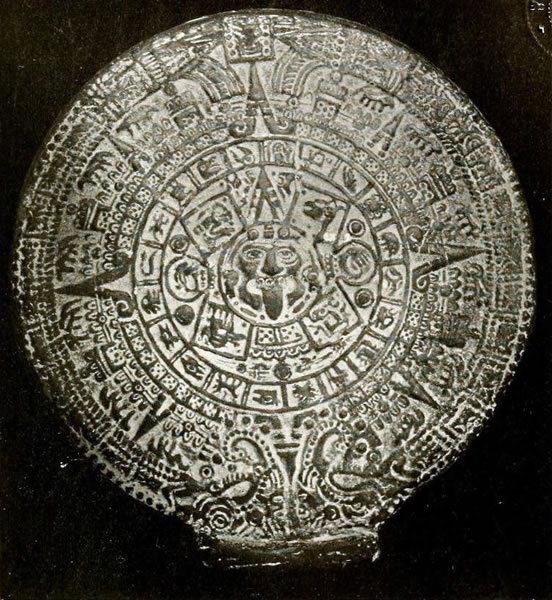

| The Aztec Calendar Stone | 298 | |

| (Courtesy of Mrs. J. R. Creelman.) | ||

| The Royal Arms of England | 302 | |

| Greek Letter Fraternity Escutcheon | 304 | |

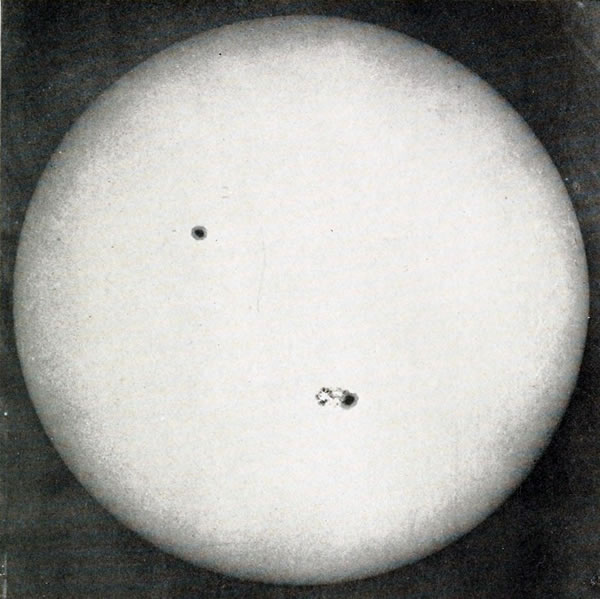

| Sun’s Disk Showing Spots and Granulation, July | ||

| 30, 1906 | 320 | |

| Yerkes. | ||

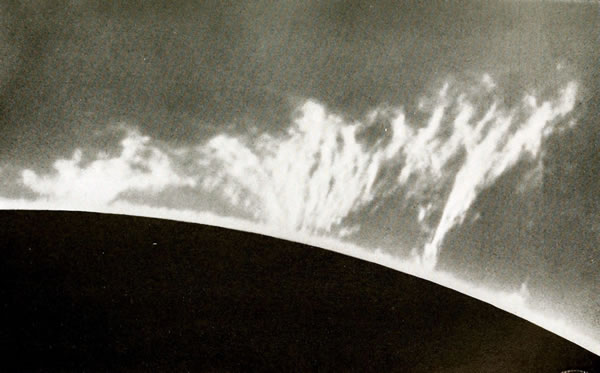

| Sun’s Limb Showing Prominences 80,000 Miles | ||

| High, August 21, 1909 | 324 | |

| From the photo at Mt. Wilson Solar Observatory. | ||

In the literature of celestial mythology, the legends that relate to the creation of the chief luminaries occupy no small part. It was natural that primitive man should at an early date speculate on the great problem of the creation of the visible universe, and especially in regard to the source whence sprang the Sun and the Moon.

This great question, of such vital interest to all nations since the dawn of history, presents a problem that is still unsolved even in this enlightened age, for, although the nebula hypothesis is fairly well established, there are astronomers of note to-day who do not altogether accept it.

The myths that relate to the creation of the sun generally regard that orb as manufactured and placed in motion by a primitive race, or by the God of Light, rather than as existing before the birth of the world. In other legends, the Sun was freed from a cave by a champion, or sprang into life as the sacrifice of the life of a god or hero.

These traditions doubtless arose from the fundamental belief that the Sun and the Moon were personified beings, and that at one time in the world’s history man lived in a state of darkness or dim obscurity. The necessity for light would suggest the invention of it, and hence a variety of ingenious methods for procuring it found their way into the mythology of the ancient nations.

Of all the solar creation myths that have come down to us, those of the North American Indians are by far the most interesting because of the ingenuity of the legends, and their great variety. We would expect to find the same myth relating to the creation of the sun predominating, as regards its chief features, among most of the Indian tribes. On the contrary, the majority of the tribes had their own individual traditions as to how the sun came into existence. They agree, however, for the most part, in ascribing to the world a state of darkness or semi-darkness before the sun was manufactured, or found, and placed in the sky.

The great tribes of the North-west coast believe that the Raven, who was their supreme deity, found the sun one day quite accidentally, and, realising its value to man, placed it in the heavens where it has been ever since.

According to the Yuma Indian tradition, their great god Tuchaipa created the world and then[5] the moon. Perceiving that its light was insufficient for man’s needs, he made a larger and a brighter orb, the sun, which provided the requisite amount of light.

The Kootenays believed that the sun was created by the coyote, or chicken hawk, out of a ball of grease, but the Cherokee myth[1] that related to the creation of the sun was more elaborate, and seems to imply that the Deluge myth was known to them.

“When the earth was dry and the animals came down, it was still dark, so they got the sun and set it in a track to go every day across the island from east to west just overhead. It was too hot this way, and the Red Crawfish had his shell scorched a bright red so that his meat was spoiled, and the Cherokee do not eat it. The conjurers then put the sun another handbreadth higher in the air, but it was still too hot. They raised it another time, and another until it was seven handbreadths high, and just under the sky arch, then it was right and they left it so. Every day the sun goes along under this arch and returns at night on the upper side to the starting place.”

This myth reveals a belief, common to many of the Indian tribes, that originally the sun was much nearer to the earth than now, and his scorching heat[6] greatly oppressed mankind. Strangely enough, although it can be nothing but a coincidence, the nebular hypothesis of modern science predicates that the solar system resulted from the gradual contraction of a nebula. This implies that the planet earth and the sun were once in comparatively close proximity.

Among the Yokut Indians, there was a tradition that at one time the world was composed of rock, and there was no such thing as fire and light. The coyote, who of all the animals was chief in importance, told the wolf to go up into the mountains till he came to a great lake, where he would see a fire which he must seize and bring back. The wolf did as he was ordered, but it was not easy to take the fire, and so he obtained only a small part of it, which he brought back. Out of this the coyote made the moon, and then the sun, and put them in the sky where they have been to this day.

The significant feature of this myth is the fact, that, contrary to the general notion, the moon’s creation antedated that of the sun. The explanation of this seeming incongruity appears in the legend of the Yuma Indians given above. The moon, although created first, did not give sufficient light, hence it was necessary to manufacture a source of light of greater power and luminosity.

The legends of the Mission Indians of California[7] reveal an altogether different view of the situation. In the myths cited above, the sun was manufactured to add to man’s comfort. In the following legend the Earth-Mother had kept the sun in hiding, waiting for mankind to grow old enough to appreciate it; so, when the time came, she produced the sun and there was light.

In order that the Sun might light the world, the people of the earth decided that it must go from east to west, so they all lifted up their arms to the sky three times and cried out each time, “Cha, Cha, Cha!” and immediately the Sun rose from among them and went up to his appointed place in the sky.

One of the Mewan Indian sun myths reveals a novel tale to account for the presence of the sun. These Indians regarded the earth as an abode of darkness in primitive times, but far away in the east there was a light which emanated from the Sun-Woman.

The people wanted light very much, and appealed to Coyote-Man to procure it for them. Two men were sent to induce the Sun-Woman to return with them, but she refused the invitation. A large number of men were then sent to bring her back, even if they had to resort to force. They succeeded in binding the Sun-Woman, and brought her back with them to their land, where she ever after afforded people the light that is so necessary[8] for their well-being. It was said that her entire body was covered with the beautiful iridescent shells of the abalone, and the light which shone from these was difficult to gaze upon.

According to a Wyandot Indian myth, the Little Turtle created the Sun by order of a great council of animals, and he made the Moon to be the Sun’s wife. He also created the fixed stars, but the stars which “run about the sky” are supposed to be the children of the Sun and Moon.

The following Yuma legend[2] indicates that the moon was considered by their ancestors as of greater importance than the sun: “Kwikumat said, ‘I will make the moon first.’ He faced the east, and placing spittle on the forefinger of his right hand rubbed it like paint on the eastern sky until he made a round shiny place. ‘I call it the moon,’ said Kwikumat. Now another god, whom Kwikumat created, rubbed his fingers till they shone, and drawing the sky down to himself he painted a great face upon it rubbing it till it shone brightly. This he called the sun.”

There is a tradition among the Pomo Indians of California, that, in very early times, the sun did not move daily across the heavens as it does now, but only rose a short distance above the eastern horizon each morning, and then sank back again.[9] This arrangement did not suit people very well, and Coyote-Man determined to better conditions, so he started eastward to see what the trouble was with the sun.

He took with him some food, a magic sleep-producing tuft of feathers, and four mice. On the fourth day he arrived at the home of the sun people, who received him cordially, and a great dance was arranged in the dance house. In the midst of this building the sun was suspended from the rafters by ropes of grape-vines.

Coyote-Man liberated the mice, and told them to gnaw at the grape-vine ropes that held the sun. Meanwhile, he danced with the sun people, and, by the aid of the sleep-producing feathers, he succeeded in stupefying all the dancers. The mice by this time had freed the sun, which Coyote-Man seized and carried off with him. On his home-coming, the sun was laid on the ground, and the people discussed what should be done with it, but Coyote-Man decided that it should be hung up in the middle of the sky. This difficult task was delegated to the birds, but they all failed until it came the crows’ turn. They were successful in hanging up the sun, and it has remained in its proper place ever since.

The Apache myth agrees with most of the Indian myths as regards the darkness that traditionally[10] reigned over the world, and the peoples’ desire for light, but their notion of the creation of the sun itself differs materially from the other Indian myths.

The myth relates that, originally, the only light in the world was that which emanated from the large eagle feathers that people carried about with them. This was such an unsatisfactory means of illuminating the world, that a council of the tribe was called for the purpose of devising a better system of lighting. It was suggested that they manufacture a sun, so they set about it. A great disk was made, and painted a bright yellow, and this was placed in the sky. The legend does not relate how this was accomplished. This first attempt at sun-making was not altogether successful, as the disk was too small. However, they permitted it to make one circuit of the heavens before it was taken down and enlarged. Four times it was taken down, and increased in size, before it was as large as the earth and gave sufficient light. Encouraged by their success at sun-making, the people made a moon, and hung it up in the sky. It appears that this light company’s business, and its success, aroused the ire of a wizard and a witch who lived in the underworld. They regarded the manufacture of the sun and moon as presumptuous acts on the part of man, and attempted to[11] destroy the luminaries; but the sun and moon fled from the underworld, leaving it in perpetual darkness, and found a safe abiding place in the heavens, where they have ever remained unmolested.

The Navajo Indian legend of the creation of the sun, moon, and stars is decidedly novel, and reveals the wide range of the imagination of primitive man in his conception of the creation of the celestial bodies.

The early Navajo, it appears, in common with many other Indian tribes, met in council to consider a means of introducing more light into the world; for, in early times, the people lived in semi-darkness, the obscurity resembling that of twilight.

The wise men concluded that they must have a sun, and moon, and a variety of stars placed above the earth, and the first work that was done to bring this about was the creation of the heavens in which to place the luminaries. The old men of the tribe made the sun in a house constructed for this special purpose, but the creation of the moon and stars they left to other tribes.

The work of creating the sun was soon accomplished, and the problem then presented itself of raising it up to the heavens and fixing it there. Two dumb fluters, who had gained considerable prominence in the tribe, were selected to bear the sun and moon (for they had also constructed a[12] moon), Atlas-like, on their respective shoulders. These were great burdens to impose on them, for the orbs were exceedingly ponderous. Therefore, the fluters staggered at first under the great weight that bore them down, and the one bearing the sun came near burning up the earth before he raised it sufficiently high; but the old men of the tribe lit their pipes and puffed smoke vigorously at the sun, and this caused it to retire to a greater distance in the heavens.

Four successive times they had to do this to prevent the burning up of the world, for the earth has increased greatly in size since ancient times; and, consequently, the sun had to be projected higher in the heavens, so that its great heat would not set the world on fire.

It will be noted that the language of the myths, as translated, has been followed closely. This was in order to bring out more fully their quaint imagery. The Indian was ever a poet, and a study of the tribal legends reveals many charming bits that would lose their beauty of expression were they transposed into the diction of our more prosaic tongue.

In the Ute Indian myth which follows, it appears that the sun had to be conquered and subjected to man’s will, before it would perform its daily task in an orderly and regular way.

It is related that the Hare-God was once sitting by his camp-fire in the woods waiting the wayward Sun-God’s return. Weary with watching, he fell asleep, and while he slumbered the Sun-God came, and, so near did he approach, that his great heat scorched the shoulders of the Hare-God. Realising that he had thus incurred the wrath of the Hare-God, the Sun-God fled to his cave in the underworld.

The Hare-God awoke in a rage, and started in pursuit of the Sun-God. After many adventures, he came to the brink of the world, and lay in wait for the object of his vengeance. When the Sun-God finally came out of his cave, the Hare-God shot an arrow at him, but the sun’s heat burned it up before it reached its mark. However, the Hare-God had in his quiver a magic arrow which always hit the mark. This he launched from his bow, and the shaft struck the Sun-God full in the face, so that the sun was shattered into a thousand fragments. These fell to the earth and caused a great conflagration.

It was now the turn of the Hare-God to be dismayed at the results of his actions, and he fled before the destruction he had wrought. As he ran, the burning earth consumed all his members save his head, which went rolling over the face of the earth. Finally, it, too, became so hot that[14] the eyes of the god burst, and out gushed a flood of tears which extinguished the fire.

But the Sun-God had been conquered, and awaited sentence. A great council was called, and, after much discussion, the Sun-God was condemned to pursue a definite path across the sky each day, and the days, nights, and seasons were arranged in an orderly fashion.

The following Cherokee Indian myth reveals the Sun as the arbiter of man’s fate: “A number of people were engaged to construct a sun, which was the first planet made. Originally it was intended that man should live forever, but the sun, when he came to survey the situation, decided that, inasmuch as the earth was insufficient to support man, it would be better to have him succumb to death, and so it was decreed.”

In Creation Myths of Primitive America, by Jeremiah Curtin, there is a particularly interesting solar myth. It is, therefore, given in much detail, as it is considered one of the most remarkable of the solar legends. As a pure product of the imagination, it ranks with the best examples of Egyptian and Grecian mythology.

The myth relates the efforts of a wicked and blood-thirsty old man named Sas,[3] to kill his son-in-law, Tulchuherris. After many ineffectual at[15]tempts to accomplish his fell purpose, he proposed a pine-bending contest, for he felt sure that, by getting his son-in-law to climb to the top of a lofty tree, he could bend it low, and, by letting go of it, suddenly hurl the object of his enmity into the sky and thus destroy him.

Tulchuherris had, however, a wise protector hidden in his hair, in the guise of a little sprite named Winishuyat, who warned him of his peril, and enabled him to turn the tables on his wicked father-in-law.

In the words of the myth: “He [Tulchuherris] rose in the night, turned toward Sas, and said: ‘Whu, whu, whu, I want you Sas to sleep soundly.’ Then he reached his right hand toward the west, toward his great-grandmother’s, and a stick came into it. He carved and painted the stick beautifully, red and black, and made a fire-drill. Then he reached his left hand toward the east, and wood for a mokos [arrow straightener] came into it. He made the mokos, and asked the fox dog for a fox-skin. The fox gave it. Of this he made a head-band, and painted it red. All these things he put into his quiver. ‘We are ready,’ said Tulchuherris. ‘Now, Daylight, I wish you to come right away.’ Daylight came. Sas rose, and soon after they started for the tree. ‘My son-in-law, I will go first,’ said Sas, and he climbed the tree. ‘Go higher,’[16] said Tulchuherris, ‘I will not give a great pull, go up higher.’ He went high and Tulchuherris did not give a great pull so that Sas came down safely. Tulchuherris now climbed the tree, almost to the top. Sas looked at him, saw that he was near the top, and then drew the great pine almost to the earth, standing with his back to the top of the tree. Tulchuherris sprang off from the tree behind Sas, and ran away into the field. The tree sprang into the sky with a roar. ‘You are killed now, my son-in-law,’ said Sas, ‘you will not trouble me hereafter.’ He talked on to himself and was glad. ‘What were you saying, father-in-law?’ asked Tulchuherris, coming up from behind. Sas turned, ‘Oh! my son-in-law, I was afraid that I had hurt you. I was sorry.’ ‘Now, my brother,’ said Winishuyat, ‘Sas will kill you unless you kill him. At midday he will kill you surely unless you succeed in killing him. Are you not as strong as Sas?’

“‘Father-in-law, try again, then I will go to the very top and beat you,’ said Tulchuherris. That morning the elder daughter of Sas said to her sister after Sas had gone, ‘My sister, our father has tried all people, and has conquered all of them so far, but to-day he will not conquer. To-day he will die. I know this. Do not look for him to-day. He will not come back. He will never come back to us.’

“Sas went up high. I will kill him now thought Tulchuherris, and he was very sorry, still he cried: ‘Go a little higher. I went higher. I will go to the top next time. I will not hurt you, go a little higher.’ Sas went higher and higher, till at last he said: ‘I cannot climb any more, I am at the top, do not give a big pull, my son-in-law.’ Tulchuherris took hold of the tree with one hand, pulled it as far as it would bend, pulled it till it touched the earth, and then let it fly. When the tree rushed toward the sky it made an awful noise, and soon after a crash was heard, a hundred times louder than any thunder. All living things heard it. The whole sky and earth shook. Olelbis, who lives in the highest place, heard it. All living things said: ‘Tulchuherris is killing his father-in-law. Tulchuherris has split Sas.’ The awful noise was the splitting of Sas. Tulchuherris stood waiting. He waited three hours perhaps, after the earth stopped trembling, then, far up in the sky he heard a voice saying: ‘Oh, my son-in-law, I am split; I am dead. I thought I was the strongest power living, but I am not. From this time on I shall say Tulchuherris is the greatest power in the world.’

“Tulchuherris could not see any one. He only heard a voice far up in the sky saying: ‘My son-in-law, I will ask you for a few things. Will you give[18] me your fox-skin head-band? Tulchuherris put his hand into his fox-skin quiver, took out the band, and tossed it to him. It went straight up to Sas and he caught it. ‘Now will you give me your mokos?’ Tulchuherris took out the mokos and threw it. ‘Give me your fire-drill.’ He threw that.

“Another voice was heard now, not so loud, ‘I wish you would give me a head-band of white quartz.’ This voice was the smaller part of Sas. When Tulchuherris had given the head-band as requested, he said: ‘My father-in-law, you are split. You are two. The larger part of you will be Sas (the Sun), the smaller part Chanah (the Moon), the white one, and this division is what you have needed for a long time, but no one had the strength to divide you. You are in a good state now. You, Chanah, will grow old quickly and die, then you will come to life, and be young again. You will be always like that in this world. Sas, you will travel west all the time, travel every day without missing a day. You will travel day after day without resting. You will see all things in the world, as they live and die. My father-in-law, take this too from me.’ Tulchuherris then threw up to Sas a quiver made of porcupine skin. ‘I will take it,’ said Sas, ‘and I will carry it always.’ Then Tulchuherris gave Chanah the quartz head[19]band, and said: ‘Wear it around your head always, so that when you travel in the night you will be seen by all people.’

“Sas put the fox-skin around his head, and fastened the mokos crosswise in front of his forehead. The fire-drill he fastened in his hair behind, placing it upright. At sunrise we see the hair of the fox-skin around the head of Sas before we see Sas himself. Next Tulchuherris threw up two red berries saying: ‘Take these and make red cheeks on each side of your face, so that when you rise in the morning, you will be bright and make everything bright.’

“Tulchuherris then went west and got some white roots from the mountains, and threw them up to Sas saying: ‘Put these across your forehead.’ Next he stretched his right hand westward, and two large shells, blue inside, came to his palm. He threw these also up to Sas saying: ‘Put these on your forehead for a sign when you come up in the morning. There is a place in the east which is all fire. When you reach that place, go in and warm yourself. Go to Olelpanti now. Olelbis, your father, lives there. He will tell you where to go.’

“Sas therefore went to Olelpanti where he found a wonderful and very big sweat-house. It was toward morning, and Olelbis was sleeping.[20] Presently he was startled by a noise and awoke, and saw some one near him. He knew at once who it was. Sas turned to him and said: ‘My father, I am split. I thought myself the strongest person in the world, but I am not; Tulchuherris is the strongest.’ ‘Well my son, Sas,’ said Olelbis, ‘where do you wish to be? and how do you wish to live?’ ‘I am come to ask you,’ replied Sas. ‘Well,’ answered Olelbis, ‘you must travel all the time, and it is better that you go from east to west. If you go northward and travel southward, I don’t think that would be well. If you go west and travel eastward I don’t think that will be well either. If you go south and travel northward I don’t think that will be right. I think that best which Tulchuherris told you. He told you to go east, and travel to the west. He said there is a hot place in the east that you must go into and get hot before you start every morning. I will show you the road from east to west. In a place right south of this is a very big tree, a tobacco tree, just half-way between east and west. When you come from the east, sit down in the shade of the tree, rest a few minutes, and go on. Never forget your porcupine quiver or other ornaments when you travel. . . . Go to the east. Go to the hot place every morning. There is always a fire in it. Take a white oak staff, thrust the end of it into the fire,[21] till it is one glowing coal. When you travel westward carry this burning staff in your hand. In summer take a manzanita staff, put it in the fire, and burn the end. This staff will be red-hot all the day. Now you may go east and begin. You will travel all the time day by day without sleeping. All living things will see you with your blowing staff. You will see everything in the world, but you will be always alone. No one can ever keep you company or travel with you. I am your father, and you are my son, but I could not let you stay with me.’”

Among the Yana Indians of California, there is a myth similar, in some particulars, to the preceding legend. It accounts for the creation of the moon, but, as the sun figures prominently in the myth, it is given in full. It relates that once a youth named Pun Miaupa ran away from home after a quarrel with his father, and came to the house of his uncle.

He told his uncle that he desired to win for his wife Halai Auna, the Morning Star, the youngest and most beautiful daughter of Wakara, the Moon. His uncle tried to persuade him from making the attempt, knowing the danger to which his nephew would be exposed, for Wakara always killed his daughter’s suitors; but finding the youth obdurate, he set out with him for Wakara’s house. After a[22] long journey they reached their destination, and now the uncle, who was a magician, knowing his nephew was in great peril, entered his nephew’s heart.

Wakara received the youth cordially, and after a time placing him in the midst of a magic family circle, performed an incantation, and the group were transported magically to the house of Tuina, the Sun. Tuina was wont to slay men by giving them poisoned tobacco to smoke, but, although he presented five pipes to Pun Miaupa, he smoked them all with no ill effects, being protected from harm by his uncle, who all the time dwelt in his heart; and Halai Auna was glad that Tuina had been foiled in his attempt to slay her suitor.

Pun Miaupa’s uncle now came forth from his nephew’s heart, and through his powerful magic caused a great deluge to descend, and Tuina, and Wakara, and their families were all drowned save Halai Auna; but, so great was her grief over the loss of her family, that the magician took pity on her and restored them to life. He then entered his nephew’s heart, and all returned to Wakara’s house. Wakara was still bent on killing Pun Miaupa, and proposed a tree-bending contest similar to that in which Sas and Tulchuherris engaged, but he, too, shared the fate of the wicked Sas and was hurled into the sky where he remained.[23] Pun Miaupa laughed and said: “Now my father-in-law, you will never come here to live again, you will stay where you are now forever. You will become small, and then you will come to life and grow large. You will be that way always, growing old and becoming young again.” Thus the moon changes in its phases from small to great as it pursues its heavenly way.

The following beautiful solar creation myth is from Japan.[4] It is entitled “The Way of the Gods” and contains a reference to a floating cloud in the midst of infinite space, before matter had taken any other form. This well describes the original nebula from which scientists aver the solar system was evolved. It is strange to find in the pages of mythology that record the creation of the celestial bodies allusions, that, in the light of modern science, savour more of fact than of fancy.

The myth is as follows: “When there was neither heaven, nor earth, nor sun, nor moon, nor anything that is, there existed in infinite space the Invisible Lord of the Middle Heaven, with him there were two other gods. They created between them a Floating Cloud in the midst of which was a liquid formless and lifeless mass from which the earth was evolved. After this were born in Heaven seven generations of gods, and the last and most[24] perfect of these were Izanagi and Izanami. These were the parents of the world and all that is in it. After the creation of the world of living things Izanagi created the greatest of his children in this wise. Descending into a clear stream he bathed his left eye, and forth sprang Amaterasu, the great Sun-Goddess. Sparkling with light she rose from the waters as the sun rises in the East, and her brightness was wonderful, and shone through heaven and earth. Never was seen such radiant glory. Izanagi rejoiced greatly, and said: ‘There is none like this miraculous child.’ Taking a necklace of jewels he put it round her neck, and said: ‘Rule thou over the Plain of High Heaven.’ Thus Amaterasu became the source of all life and light, the glory of her shining has warmed and comforted all mankind, and she is worshipped by them unto this day.

“Then he bathed his right eye, and there appeared her brother, the Moon-God. Izanagi said: ‘Thy beauty and radiance are next to the Sun in splendour; rule thou over the Dominion of Night.’”

In Norse mythology it is said that Odin arranged the periods of daylight and darkness, and the seasons. He placed the sun and moon in the heavens, and regulated their respective courses. Day and Night were considered mortal enemies. Light came from above, and darkness from be[25]neath, and in the process of creation the moon preceded the sun.

There is, however, a Norse legend opposed to the view that the gods created the heavenly bodies. This avers that the sun and moon were formed from the sparks from the fire land of Muspelheim. The father of the two luminaries was Mundilfare, and he named his beautiful boy and girl, Maane (Moon) and Sol (Sun).

The gods, incensed at Mundilfare’s presumption, took his children from him and placed them in the heavens, where they permitted Sol to drive the horses of the sun, and gave over the regulation of the moon’s phases to Maane.

Among the Eskimos of Behring Strait the creation of the earth and all it contains is attributed to the Raven Father. It is related that he came from the sky after a great deluge, and made the dry ground. He also created human and animal life, but the rapacity of man threatened the extermination of animal life, and this so annoyed the Raven that he punished man by taking the sun out of the sky, and hiding it in a bag at his home. The people, it is said, were very much frightened, and disturbed at the loss of the sun, and offered rich gifts to the Raven to propitiate him; so the Raven relented somewhat, and would hold the sun up in one hand for a day or two at a time, so that[26] the people could have sufficient light for hunting, and then he would put it back in the bag again.

This arrangement, though better than nothing, was not, on the whole, satisfactory to people, so the Raven’s brother took pity on them, and thought of a scheme to better conditions. He feigned death, and after he had been buried and the mourners had gone away, he came forth from the grave, and took the form of a leaf, which floated on the surface of a stream. Presently, the Raven’s wife came to the stream for a drink, and dipping up the water she swallowed with it the leaf. The Raven’s wife soon after gave birth to a boy who cried continually for the sun, and his father, to silence him, often gave him the sun to play with. One day, when no one was about, the boy put on his raven mask and coat, and taking up the sun flew away with it, and placed it in its proper place in the sky. He also regulated its daily course, making day and night, so that ever thereafter the people had the constant light of the sun to guide them by day.

The ancient Peruvians believed that the god Viracocha rose out of Lake Titicaca, and made the sun, moon, and stars, and regulated their courses. Tylor[5] tells us that originally the Muyscas, who inhabited the high plains of Bogota, lived in a[27] state of savagery. There came to them from the east an old bearded man, Bochica (the Sun), who taught them agriculture and the worship of the gods. His wife Huythaca, however, was displeased at his attentions to mankind, and caused a great deluge which drowned most of the inhabitants of the earth.

This action angered Bochica, and he drove his wicked wife from the earth and made her the Moon (for heretofore there had been no moon). He then dried up the earth, and once more made it habitable, and comfortable for man to live in.

The Manicacas of Brazil regarded the sun as a hero, virgin born. Their wise men, who claimed the power of transmigration, said that they had visited the Sun, and that his figure was that of a man clothed in light; so dazzling was his appearance that he could not be seen by ordinary mortals.

According to Mexican tradition, Nexhequiriac was the creator of the world. He sent down the Sun-God and the Moon-God to illuminate the earth, so that men could see to perform their daily tasks. The Sun-God pursued his way regularly and unhindered, but the Moon-God, being hungry, and perceiving a rabbit in her path, pursued it. This took time, and then she tarried to eat it, but when she had finished her meal, she found her brother, the Sun, had outdistanced her, and was[28] far ahead, so that ever thereafter she was unable to overtake him. This is also the reason, says the legend, why the sun always appears to be ahead of the moon, and why the sun always looks fresh and red, and the moon sick and pale. Those who gaze intently at the moon can still see the rabbit dangling from her mouth.

The Bushmen of South Africa have a curious legend to account for the creation of the sun. According to this tradition, the Sun was originally a man living in a dwelling on earth, and he gave out only a limited amount of light, which was confined to a certain space about his house, and the rest of the country was in semi-darkness. Strangely enough, the light which he gave out emanated from one of his arm-pits when his arm was upraised. When he lowered his arm, semi-darkness fell upon the earth. In the day the Sun’s light was white, but at night the little that could be seen was red like fire. This obscure light was unsatisfactory to the people, and, just as we have seen the Indians of North America met in council to decide the question of a better light for the world, the Bushmen considered the matter, and an old woman proposed that the children seize the Sun while he was sleeping, and throw him up into the sky, so that the Bushman’s rice might become dry for them, and the Sun make bright the whole world.[29] So the children acted on the suggestion, and approached the sleeping Sun warily; finally, they crept up close, and spoke thus to him: “Become thou the sun which is hot so that the Bushman’s rice may dry for us, that thou mayst make the whole earth light, and the whole earth may become warm in summer.” Therewith, they all seized the Sun by the arm, and hurled him up into the sky. The Sun straightway became round, and remained in the sky forever after to make the earth bright, and the Bushmen say that it takes away the moon and pierces it with a knife.

According to New Zealand traditions, the sun is the eye of Maui, which is placed in the sky, and the eyes of his two children became the morning and the evening star. The sun was born from the ocean and the story of its birth is thus related[6]: “There were five brothers all called Maui, and it was the youngest Maui who had been thrown into the sea by Taranga his mother, and rescued by his ancestor Great-Man-In-Heaven, who took him to his house and hung him in the roof. One night, when Taranga came home, she found little Maui with his brothers, and when she knew her last born, the child of her old age, she took him to sleep with her, as she had been wont to take his brothers before they were grown up. But the little Maui[30] became vexed and suspicious when he found that every morning his mother rose at dawn and disappeared from the house in a moment, not to return till nightfall. So one night he crept out, and stopped up every crevice in the wooden window, and the doorway, that the day might not shine into the house. Then broke the faint light of early dawn, and then the sun rose and mounted into the heavens, but Taranga slept on, for she knew not that it was broad daylight outside. At last she sprang up, pulled out the stopping of the chinks, and fled in dismay. Then Maui saw her plunge into a hole in the ground and disappear, and thus he found the deep cavern by which his mother went down below the earth as each night departed.”

Another Maori legend relates that Maui once took fire in his hands, and when it burned him he sprang with it into the sea. When he sank in the waters the sun set for the first time, and darkness covered the earth. When Maui found that all was night he immediately pursued the sun and brought him back in the morning.

The Tonga tribe, of the South Pacific Islands, have a curious myth respecting the creation of the sun and moon. It appears that in primitive times, before there was any light upon the earth, Vatea and Tonga-iti quarrelled as to the parentage of a child. Each was confident the child was his, and[31] to end the dispute they decided to share it. The infant was forthwith cut in two; Vatea took the upper half as his share, and squeezing it into a ball tossed it up into the sky where it became the sun. Tonga-iti allowed his share, the lower part of the infant, to remain on the ground for a day or two, but seeing the brightness of Vatea’s half, he squeezed his share too, and threw it up into the dark sky when the sun was absent in the underworld, and it became the moon. Thus the sun and the moon were created, and the paleness of the moon is due to the fact that all the blood was drained out of it when it lay on the ground.

An Australian legend relates that the world was in darkness till one of their ancestors, who dwelt in the stars, took pity on them, and threw into the sky an emu’s egg, which straightway became the sun.

The Dyaks have a myth that the sun and the moon were created by the Supreme Being out of a peculiar clay which is found in the earth, but is very rare and costly. Vessels made from this clay are considered holy and a protection against spirits. These people, and other tribes dwelling in mountainous regions where the sun’s red disk disappears from sight each night behind the mountains, speak of the sun as setting in a deep cleft in the rocks.

There are numerous other myths, of many[32] lands, that tell in the language of imagination of the birth of the sun and moon. Most of them, however, are fundamentally identical with those cited.

The close agreement in the traditions of many of the primitive inhabitants of the earth, that there was life in the world before the luminaries occupied the heavens, and that people then lived in a state of semi-darkness, is perhaps the most striking feature of the myths.

In fact, these ancient legends reveal many points that are of interest, especially where similarities exist in the early traditions of widely separated tribes. It seems extraordinary that men, in different parts of the world, could have independently conceived the grotesque notions that often characterise the solar creation myths.

There seems to have been no limit to the fancies concerning the creation of the heavenly bodies by the ancients, but there is little doubt that, were the world to-day deprived of the teachings of science, our imaginative instinct would enable us to construct a myth to account for the presence of the sun, a myth that would be fully as fantastical as any which mythology has bequeathed to us.

A study of mythology reveals many legends and traditions that concern the Sun and the Moon as related in some way by family or marital ties. Consequently, in spite of the fact that the purpose of this volume is to afford a comprehensive review of solar lore, these legends were considered sufficiently interesting as a further revelation of the solar myth to be included.

In the early history of all people we find the Sun and Moon regarded as human beings, more or less closely connected with the daily life of mankind, and influencing in some mysterious way man’s existence, and controlling his destiny. We find the luminaries alluded to as ancestors, heroes, and benefactors, who, after a life of usefulness on this earth, were transported to the heavens, where they continue to look down on, and, in a measure, rule over earthly affairs.

The chief nature of the influence supposedly[36] exerted by the Sun and Moon over men was parental. In fact, the very basis of mythology lies in the idolatrous worship of the solar great father, and the lunar great mother, who were the first objects of worship that the history of the race records.

“The great father,” says Faber,[7] “was Noah viewed as a transmigratory reappearance of Adam, and multiplying himself into three sons at the beginning of each world, the great mother was the earth considered as an enormous ship floating on the vast abyss, and the ark considered as a smaller earth sailing over the surface of the Deluge. Of these, the former was astronomically typified by the sun, while the latter was symbolised by the boat-like crescent of the moon.”

As human beings, the Sun and Moon were naturally distinguished as to sex, although there is in the early traditions concerning them no settled opinion as to the sex assigned to each, nor their relation to one another. Thus, in Australia, the Moon was considered to be a man, the Sun a woman, who appears at dawn in a coat of red kangaroo skins, the present of an admirer. Shakespeare speaks of the Moon as “she,” while in Peru, the moon was regarded as a mother who was both sister and wife of the Sun, like Osiris and Isis in[37] Egypt. Thus the sister marriages of the Incas had in their religion a meaning and a justification.

The Eskimos believed that the Moon was the younger brother of the female Sun, while the early inhabitants of the Malay peninsula regarded both the Sun and Moon as women. One of the Indian tribes of South America regarded the Moon as a man, and the Sun his wife. The story goes that she fell twice; the first time she was restored to heaven by an Indian, but the second time she set the forest blazing in a deluge of fire.

Tylor[8] tells us that the Ottawa Indians, in their story of Iosco, describe the Sun and Moon as brother and sister. “Two Indians,” it is said, “sprang through a chasm in the sky, and found themselves in a pleasant moonlit land. There they saw the moon approaching as from behind a hill. They knew her at first sight. She was an aged woman with white face and pleasing air. Speaking kindly to them, she led them to her brother the sun, and he carried them with him in his course and sent them home with promises of happy life.”

Other Indian tribes, such as the Iroquois, Athapascas, and Cherokees, regarded the Sun as feminine, and, as a whole, the North American myths represented the Sun and Moon more frequently[38] as brother and sister than as man and wife. In Central and South America, on the contrary, particularly in Mexico and Peru, the Sun and Moon were regarded as man and wife, and they were called, respectively, grandfather and grandmother.

This confusion in the sex, ascribed to the Sun and Moon by different nations, may have arisen from the fact that the day is mild and friendly, hence the Sun which rules the day would properly be considered feminine, while the Moon which rules the chill and stern night might appropriately be regarded as a man. On the contrary, in equatorial regions, the day is forbidding and burning, while the night is mild and pleasant. Applying these analogies, it appears that the sex of the Sun and Moon would, by some tribes, be the reverse of those ascribed to them by others, climatic conditions being responsible for the confusion.

In the German language, the genders of the Sun and Moon are respectively feminine and masculine, contrary to the rule of the Romance languages, whereas, in Latin, the Sun is masculine and the Moon feminine. In the Upper Palatinate of Bavaria to-day it is still common to hear the Sun spoken of as “Frau Sonne,” and the Moon as “Herr Mond,” and this story is told of them:

“The moon and sun were man and wife, but the moon proving too cold a lover, and too much ad[39]dicted to sleep, his wife laid him a wager by virtue of which the right of shining by day should belong in future to whichever of them should be the first to awake. The moon laughed but accepted the wager, and awoke next day to find the sun had for two hours already been lighting up the world. As it was also a condition and consequence of this agreement that unless they awoke at the same time they should shine at different times the effect of the wager was a permanent separation, much to the affliction of the triumphant sun, who, still retaining a spouselike love for her husband, was, and always is, trying to repair the matrimonial breach.”

From the conception that the Sun and Moon were husband and wife many legends concerning them were created, chief among these being the old Persian belief that the stars were the children of the Sun and Moon.

The primitive natives of the Malay peninsula believed that the firmament was solid. They imagined that the sky was a great pot held over the earth by a slender cord, and if this was ever broken the earth would be destroyed. They regarded the Sun and Moon as women, and the stars as the Moon’s children. A legend relates that the Sun had as many children as the Moon, in ancient times, and fearing that mankind could[40] not bear so much brightness and heat, the Sun and Moon agreed to devour their children.

The Moon pretended to thus dispose of hers, and hid them instead; but the Sun kept faith, and made way with all her children. When they were all devoured, the Moon brought hers out from their hiding-place. When the Sun saw them she was very angry, and pursued the Moon to kill her, and the chase is a perpetual one. Sometimes the Sun comes near enough to bite the Moon, and then men say there is an eclipse. The Sun still devours her children, the stars, at dawn, and the Moon hides hers during the daytime, when the Sun is near, only revealing them at night when her pursuer is far away. One of the native tribes of Northern India believes that the Sun cleft the moon in two for her deceit, and thus cloven and growing old again she remains.

The daughters of the Sun and Moon are represented in Finnish mythology as young and lovely maidens, seated sometimes on the border of a red shimmering cloud, sometimes upon a rainbow, sometimes at the edge of a leafy forest. They were surpassingly skilful in weaving, an accomplishment probably suggested by the resemblance borne by rays of light to the warp of a web. As might be expected in such a climate, the gods of the Sun, Moon, and stars are represented as serene[41] and noble beings, dwelling in glorious palaces, possessing all that earth contained of beauty, and generally willing to share with mankind the knowledge of mundane affairs, which their penetrating rays and lofty position secured for them.

In Finnish, the appellation “Paeivae,” came to mean Sun and Sun-God, “Knu,” Moon and Moon-God. Paeivae had two sons, one of whom was named “Panu.”[9]

There are many legends of the sun and moon that relate their disputes and marital troubles, for mythology reveals that as husband and wife the Sun and Moon did not live happily together.

In the Kanteletar (a collection of Finnish popular songs), an amusing tale is told which concerns the Sun, Moon, and Pole Star, who, as the story goes, were suitors for the hand of a beautiful maiden hatched from a goose egg. “The pole star was successful, and won the maiden, who objected to the moon, as there was nothing stable in his appearance, inasmuch as his face was sometimes narrow, and sometimes broad. Moreover, he had a bad habit of roving about all night, and remaining idle at home all day, which habit was highly detrimental to the true interest of a house[42]hold. She objected to the sun as he caused not only the heat in summer but also the cold in winter, and the variations of the weather. The pole star she accepted because he always came home punctually.”

In Bavaria, a tale is told about a maid “who was drawn up by the moon, thereby incurring the sun’s jealousy. The sun, to get even with her faithless consort, spying the girl’s lover asleep in a wood took him up to herself. The maid and her lover perceiving themselves thus remote from one another were naturally anxious to meet again, and a great grief it was to the moon when he found that the maiden no longer cared for him. The tears he sheds in consequence are what we call ‘shooting stars.’”

Thorpe[10] gives the following account of the relationship between the Sun and Moon:

“The moon and the sun are brother and sister. They are the children of Mundilföri, who, on account of their beauty, called his son ‘Mâni,” and his daughter ‘Sôl,’ for which presumption the gods in their anger took the brother and sister, placed them in the sky, and appointed Sôl to drive the horses that draw the chariot of the sun, which the gods had formed to give light to the world. The names of the horses that bear her car[43] are the ‘Watchful,’ and the ‘Rapid,’ and under their shoulders the gods placed an ice-cold breeze to cool them.

“A shield stands before the sun; if it were not for this, the great heat would set the waves and mountains on fire. Two fierce wolves accompany the sun, a widespread and popular superstition, one named ‘Sköll’ follows the sun, and which she fears will devour her, the other called ‘Hati’ runs before the sun, and tries to seize the moon,—and so in the end it will be. The mother of these wolves is a giantess, who dwells in a wood to the east of Midgard. She brought forth many sons who are giants and all in the form of wolves. One of this race called ‘Managarm’ is said to be the most powerful. He will be sated with the lives of all dying persons. He will swallow up the moon, and thereby besprinkle both heaven and air with blood, then will the sun lose its brightness, and the winds rage and howl in all directions. Mâni directs the course of the moon. He once took up two children from the earth as they were going from a well bearing a bucket on their shoulders. They followed Mâni, and may be observed from the earth.”

Among the Indians of North America we find many legends relating to the Sun and Moon, who were regarded by them as living beings. They[44] taught their children that the sun represents the eyes of the mighty Manito by day, the god the Indians worshipped, and that the moon and stars were his eyes by night, and that they could not hide their words or acts from him. We find practically this same belief among the natives of Australia, who regard the sun as the eye of the greater god, and the moon as the eye of the lesser god.

The following is Father Brébeuf’s version of the Huron legend of “the white one and the dark one,” an interesting bit of Indian mythology:

“The sun and moon were known to the Hurons as Iouskeha and Taoniskaron, respectively. When they were grown up they quarrelled and fought a duel. Iouskeha was armed with a stag horn, while Taoniskaron contented himself with some wild rose berries, persuading himself that as soon as he should thus smite his brother he would fall dead at his feet, but it happened otherwise, and Iouskeha struck him so heavy a blow in the side that the blood gushed forth in streams. Taoniskaron fled and from his blood which fell upon the land came the flints which the savages still call ‘Taoniscara,’ from the victims name. Iouskeha was regarded by the Indians as their benefactor, their kettle would not boil were it not for him, it was he who learned from the Tortoise the art of[45] making fire. Without him they would have no luck hunting, and it is he who makes the corn grow.

“Iouskeha the sun takes care for the living, and all things concerning life, and therefore, says the missionary, they say he is good; but the moon, who is the creatress of earth and man, makes men die, and has charge of their departed souls, and they say she is evil. The sun and moon dwell together in their cabin at the end of the earth, and thither it was that four Indians made a mythic journey. The sun received the travellers kindly, and saved them from the harm the beautiful but hurtful moon must have done them.”[11]

In early Iroquois legends, the Sun and Moon are god and goddess of day and night, respectively, and acquired the characters of the great friend and enemy of man, the good and evil deities.

The Cheyenne Indians have a legend that relates to a dispute that took place between the sun and moon as to which was superior. The Sun said that he was bright and glorious to behold, that he ruled the day, and that no being was superior to him. The Moon replied that he ruled the night, and looked after all things on earth, and kept all men and animals from danger and that he had no superior. The Sun retorted, “It is I who light up[46] the world. If I should rest from my work everything would be darkened, mankind could not do without me.” Then the Moon replied: “I am great and powerful. I can take charge of both night and day, and guide all things in the world. It does not trouble me if you rest.” Thus the Sun and the Moon disputed, and the day they spoke thus to each other became almost as long as two days, so much did they have to say to each other. Neither gained his point, although the Moon declared there were a great many wonderful and powerful beings on his side. He had reference to the stars.

The old theologists ascribed to both the Sun and Moon the guardianship of certain gates or doors in the firmament. These imaginary portals, they claimed, were in the two opposite tropics, and from them it was believed that all human souls were mysteriously born.

The Japanese believe that the moon is inhabited by a hare, and that the sun is the abode of a three-legged crow, hence the expression, “The golden crow, and the jewelled hare,” meaning the sun and moon.

There was a belief current in ancient times, in countries remote from each other, that those great in authority, or of a superior order of society, were descendants of the Sun.

Among the Hindus, the members of the military caste to which the rajahs always belong are styled “Surya-bans,” and “Chandra-bans,” or Children of the Sun, and Children of the Moon.

“The first Egyptian dynasty is said to have been that of the ‘Aurites,’ or Children of the Sun, for the Oriental word ‘Aur’ denotes the solar light.

“The Persian sun-god Mithras bore the name of ‘Azon-Nakis,’ or the lord Sun, and from him both his descendants, the younger hero gods, and his ministers the magi, were denominated ‘Zoni’ and ‘Azoni,’ or the posterity of the Sun.

“Among the Greeks we find an eminent family distinguished by the name of the ‘Heliadæ,’ or Children of the Sun, and originally this family consisted of eight persons. The Greeks were also familiar with the Children of the Moon. This ancient title was the ancient appellation of the Arcadians.

“Among the early Britons it was acknowledged that the solar ‘Hu’ was the father of all mankind. The Incas of Peru traced their genealogy from the sun, and called themselves Children of the Sun.”[12]

It is natural that the diurnal motion of the sun and moon should have stimulated the imagination of ancient man, and led him to account for this[48] movement in a variety of fanciful ways. At an early date the idea was current that there was a subterranean world, into which the sun descended at nightfall, and traversed during the dark hours, to emerge from the cave in the east at dawn.

Among the red races, one tribe thought that the Sun, Moon, and stars were men and women, who went into the western sea every night, and swam out by the east. They say “the sun cometh forth every morning at the Place of Breaking Light.” From this idea there rose the fancy that the Sun at evening was swallowed up by some monster, and the personified sun is a hero or a virgin who is swallowed and afterwards released or rejected, as in the Greek myths of Perseus and Andromeda, and Hercules and Hesione, the old Norse story of Eerick and the Dragon, and the more similar Teutonic myth of Little Red Riding Hood.

The Mexicans believed that “when the old sun was burnt out, and had left the world in darkness, a hero sprang into a huge fire, descended into the shades below, and arose deified and glorious in the east as ‘Tonatiuh,’ the sun. After him there leapt in another hero, but now the fire had grown thin, and he rose only in milder radiance as ‘Metztli,’ the moon.”[13]

The Nimbus-Crowned Figure (Mithras)

Courtesy of Professor A. V. W. Jackson and The Macmillan Co.

From persons possessing an all-powerful influence over mankind, the sun and moon came to be regarded as places where men could be consigned, and the extremes of heat and cold associated with them respectively gave rise to the idea that the sun and moon were places where men were sent in punishment for earthly misdeeds, there to suffer eternally for their sins.

The belief in the power of the sun and moon as persons to take up to them human beings from earth may next be shown to have had an influence over mythology. The sun and moon were both believed to possess this power of abducting mortals whom it pleased them to transport to the sky.

The Greeks of modern Epirus have a tale of a childless woman, who, having prayed to the Sun for a girl, gained her request, subject only to the condition that the girl be restored to the Sun when she became twelve years of age. When the child had reached that age, and was one day picking vegetables in the garden, whom should she meet but the Sun. That luminary bade her go and remind her mother of her promise. The mother, in terror and consternation, shut the doors and windows to keep her child safe from the sun, but unfortunately she forgot the keyhole, by which entrance the Sun penetrated and succeeded in carrying off his prey.

The Bushmen, almost the lowest tribe of South[50] Africa, have the same star lore and much the same mythology as the Greeks, Australians, Egyptians, and Eskimos. They believe that the Sun and Moon originally inhabited the earth and talked with men, but now they live in the sky and are silent.

The Homeric hymn to the Sun-God Helios, in the same way (as Professor Max Müller observes), regards the Sun as a half-god, almost a hero, who had once lived on earth. This mythological sojourn of the Sun and Moon on the earth seems to have stimulated the mind of primitive man, and has given rise to a wealth of legends and traditions which is to be found in the ancient history of all nations.

Some one has said: “If no other knowledge deserves to be called useful but that which helps to enlarge our possessions or to raise our station in society, then mythology has no claim to usefulness. But if that which tends to make us happier and better can be called useful, a knowledge of mythology is useful, for it is the handmaid of literature, and literature is one of the best allies of virtue and promoters of happiness.”

The solar myth, above all others, commands the attention and interest of the student of mythology, for it is the very basis of the science; it permeates the early history of all people, its influence has made itself felt in every age, and many of the customs that govern our lives to-day are of solar origin.

The sun, above all that human eyes behold, is the chief element in life, the very essence of our existence, and to its beneficent influences we owe all that we possess to-day, that is of worth. How[54] few realise this fact. “‘Differentiated sun-shine,’ is the striking and suggestive phrase used by John Fiske in his Cosmic Philosophy to stand for all things whatsoever to be found in this great world of ours; from the tiny sun-dew, hid in the secret abiding places of spreading swamp lands, and the inconsequent midget it opens its sticky little fist to grasp, to the great forest tree, and all-consequent man armed with his conquering broadaxe. It is merely a terse symbolic way of describing the processes of cosmic evolution from the sun as the original source and continuous guiding power of our own special universe.”

“Back of the present sun figures in primitive and culture lore are the animistic conceptions of the sun such as that of Manabozho, or the great white hare, of Algonquin legend, or Indra the bull sun of India. In course of time the zoömorphic sun gives place to the anthropomorphic sun, and finally we arrive at such personifications of the sun as Osiris in Egypt, Apollo in Greece, and Balder in Norse mythology. Indeed it might almost be said that all the great steps in the onward march of the human race could be found recorded in the various and multiple personifications of the sun.”[14]

Our ideas concerning natural phenomena are[55] but the result of past ages of research in the fields of science; but when we come to a consideration of the phenomena that day and night present, in their ever-changing phases, we find it extremely difficult to clearly understand the mental view-point of primitive man regarding this continual change, for the uninterrupted sequence and constant repetition of this phenomena has dulled our faculties and it escapes our attention.

In ancient times, however, this continual daily process was closely observed and seriously considered, and the sun in all its aspects became at an early date in certain countries a personified godhead.

The expression “swallowed up by night” is now a mere metaphor, but the idea it conveys, that of the setting sun, was a matter of great importance to the ancients. However, the daily aspects of the sun were not alone matters of concern, the seasonable changes were closely observed, and the spring-tide sun, returning with youthful vigour after the long sleep in the night of winter, had a different name from the summer and autumnal sun. There are consequently, a multiplicity of names for the sun to be found in a study of primitive history and mythology, and an enormous mass of sun myths depicting the adventures of a primitive sun hero in terms of the varying aspects which the sun assumes during the day and year.

There was simply no limit to the images suggested by these aspects, as Sir George Cox puts it[15]:

“In the thought of these early ages the sun was the child of night or darkness, the dawn came before he was born, and died as he rose in the heavens. He strangled the serpents of the night, he went forth like a bridegroom out of his chamber, and like a giant to run his course. He had to do battle with clouds and storms, sometimes his light grew dim under their gloomy veil, and the children of men shuddered at the wrath of the hidden sun. His course might be brilliant and beneficent, or gloomy, sullen, and capricious. He might be a warrior, a friend, or a destroyer. The rays of the sun were changed into golden hair, into spears and lances, and robes of light.”

From this play of the imagination the great fundamental solar myths sprang, and these furnished the theme for whole epics, and elaborate allegories. Out of this enduring thread there came to be woven the cloth of golden legend, and the wondrous tapestry of myth that illuminates the pages of man’s history.

It is our pleasant task to review this variegated tapestry that fancy displays, and inspect the great treasure-house of tradition where the people of all[57] ages have stored the richest gift of their imagination, the solar myth.

Perhaps the earliest sun myths are those founded on the phenomena of its rising and setting. The ancient dwellers by the seashore believed that at nightfall, when the sun disappeared in the sea, it was swallowed up by a monster. In the morning the monster disgorged its prey in the eastern sky. The story of Jonah is thought to be of solar origin, his adventure with the whale bearing a striking analogy to the daily mythical fate of the sun.

Goldhizer,[16] an eminent mythologist, claims that the Biblical story of Isaac is a sun myth, and the first Enoch, the son of Cain, is of pure solar significance. He is a famous builder of cities, a distinct solar feature, but the fact that he lived exactly 365 days, the length of the solar year, proclaims his solar character. Cain is a sun hero and among his descendants none but solar figures are to be found. Noah is clearly a mythical figure of the sun resting, the word Nôach denoting “him who rests.”

The word which pre-eminently denotes the sun in the Semitic languages, the Hebrew “Shemesh,” conveys the idea of rapid motion, or busy running about. Thus we see in the Psalms the sun likened to a giant or hero running a course.

Swift steeds were associated with the sun in[58] Classical, Indian, Persian, and Hebrew mythologies, and in the Hebrew worship in Canaan, horses were dedicated to the sun, as indeed they were in Greece at a later date.

In the Veda the sun is frequently called “the runner,” “the quick racer,” or simply “the horse.” This idea of the swift flight of the sun is further carried out by attributing wings to the sun, or dawn, and on the Egyptian and Assyrian monuments we find the winged solar disk inscribed.

From this it was but a step of the imagination to regard the sun as a bird, and when the sun set the ancients said: “The bird of day is weary, and has fallen into the sea.” It is even thought that the hare is symbolic of Eastertide, for the very reason that fleetness of foot was its chief attribute. It is also a significant fact that the solar personification of the North American Indians was called “the Great White Hare.”

“The more the Babylonian mythology is examined,” says Sayce, “the more solar is its origin found to be, thus confirming the results arrived at in the Aryan and Semitic fields of research. With two exceptions only the great deities seem all to go back to the sun.”

Of the mythology of Egypt, the eminent authority Renouf makes the statement: “Whatever may be the case in other mythologies, I look upon the[59] sunrise and sunset, on the daily return of day and night, on the battle between light and darkness, on the whole solar drama in all its details that is acted every day, every month, every year, in heaven and in earth as the principal subject of Egyptian mythology.”

The predominant mythological figures of Egypt were so much involved in the sun worship of that country, and to such an extent Sun-Gods, that a discussion of their personality and deeds pertains more properly to the chapter on Sun Worship, and is omitted therefore in this place.

There is one feature of solar mythology that is striking because of its universality, and that is the connection which the figures personifying the sun in various lands have with navigation. The Jewish Midrash compares the course of the sun to that of a ship, and curiously enough to a ship coming from Britain, which is rigged with 365 ropes (the number of days in the solar year), and to a ship coming from Alexandria which has 354 ropes (the number of days of the lunar year).

In Egypt we see on the monuments the figure of Ra, the Sun-God, in his boat sailing over the ocean of heaven. “The sun king Apollo is with the Greeks,” says Goldhizer,[17] “the founder of navigation,” and even the legendary Charon, the ferry[60]man of the underworld, is a development of the solar myth. The Roman Sun-God, Janus, is also brought into connection with navigation, and the Peruvian sun deity came to them from the sea, and took his leave of them in a ship which floated down a river to the sea where it vanished.

The ancient Egyptians called the sun “the Cat,” for, “like the sun,” says Horapollo, “the pupil of the cat’s eye grows larger with the advance of day.” The Egyptians imagined that a great cat stood behind the sun which was the pupil of the cat’s eye.

The following sun myth found in India is quoted from Anthropology by Edward B. Tylor. It relates that: “Vâmana, the tiny Brahman, to humble the pride of King Bali, begs of him as much land as he can measure in three steps, but when the boon is granted, the little dwarf expands into the gigantic form of Vishnu, and striding with one step across the earth, another across the air, and a third across the sky, drives Bali into the infernal regions, where he still reigns. This most remarkable of all Tom Thumb stories seems really a myth of the sun, rising tiny above the horizon, then swelling into majestic power, and crossing the universe. For Vâmana the dwarf is one of the incarnations of Vishnu, and Vishnu was originally the sun. In the hymns of the Veda the idea of[61] his three steps is to be found before it had become a story, when it was as yet only a poetic metaphor of the sun crossing the airy regions in his three strides.”

The ancient Hindus enthroned the Sun-God in a burning chariot, and saw in his flashing rays spirited and fiery steeds arrayed in resplendent and gleaming trappings. Where we would say, “the sun is rising,” or, “he is high in the heavens,” they remarked, “the sun has yoked his steeds for his journey.”

One of the common appellations for the sun in mythology is “the cow,” and the sun’s rays are described as the cow’s milk. In the Veda this is one of the most familiar conceptions. These are good examples of the part imagination has played in the development of solar mythology. Given the notion that the sun is a chariot, the rays are seen immediately to resemble steeds, and, likewise, if the sun be likened to a cow, the rays must peradventure represent milk.

The sun’s rays are compared more consistently with locks of hair or hair on the face or head of the sun. The Sun-God Helios is called by the Greeks “the yellow-haired,” and long locks of hair and a flowing beard are mythological attributes of the sun in many lands. In an American Indian myth the Sun-God is described as an old man with a[62] full beard, and the long beards of the Peruvian and Toltec Sun-Gods are often referred to in the mythological references concerning them.

If mythology is regarded as a wondrous piece of tapestry, wrought by imagination and fancy, displaying in many hues the noble deeds of gods and heroes of the ancient world, then, the part woven by the Greeks may well be considered the most conspicuous for brilliancy of conception and beauty of design of all that enters into this marvellous and priceless fabric.

It has been said that Greek mythology, in its dynastic series of ruling gods, shows an evolution from a worship of the forces of nature to a worship of the powers of the mind. It is beyond question the most complete in its details, the most perfect viewed from an artistic standpoint, the most beautiful and enduring of all the world’s store of legendary lore that has come down to us, and in this wealth of mythology, the solar myth stands out supreme, as the central figure, clothed in the matchless imagery of a naturally poetical and highly artistic people.

In the following discussion of the Greek sun myths, there is much that seems so grotesque and fanciful as to border on absurdity, but the seriousness of the subject cannot be doubted, and, in order to understand it fully, with a true sense of[63] appreciation, we must ever regard the legends as interpreting the natural phenomena of day and night. Bearing this fact in mind will enable us to grasp the significance of much that would otherwise be meaningless.

The daily motions and varying aspects of the living and energetic sun hero may be said to comprise the motif of almost every legend and myth bequeathed to us by the ancients.

As in the study of sun worship, the Sun-God Helios first occupies the scene as the central figure in a widely spread and popular cultus, we will first consider the legends that cluster about this mythical personage whom the Greek nation once revered and worshipped with all the fire of religious ardour.

The most interesting myth concerning Helios is that told of him in the Odyssey. It relates that when the hero Odysseus was returning to his home in Ithaca, the goddess told him of the verdant island of Trinacria, where the Sun-God Helios pastured his sacred herds, consisting of seven herds of cows and seven herds of lambs, fifty in each herd, a number which ever remained constant. Odysseus, desirous of visiting this fair isle, set out forthwith, having been warned by Circe to leave the herds of the Sun unmolested lest he suffer evil consequences. Having landed on the island, his[64] companions enjoyed to the full the delightful climate, but as food was short, they ignored the warning of the goddess, slaughtered the Sun’s best cattle, and feasted on them for six days, when they took their departure.

Helios, deeply incensed by their conduct, and grieving for his lost herds, in which he had taken great pride and pleasure, besought Jove’s aid to punish them:

|

“O Father Jove, and all ye blessed gods

Who never die, Avenge the wrong I bear Upon the comrades of Laertes’ son Ulysses, who have foully slain my beeves, In which I took delight whene’er I rose Into the starry heaven, and when again I sank from heaven to earth. If for the wrong They make not large amends, I shall go down To Hades, there to shine among the dead. The cloud-compelling Jupiter replied: