* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Rex

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Fullerton Waldo

Date first posted: July 4, 2013

Date last updated: July 4, 2013

Faded Page eBook #20130708

This eBook was produced by: David T. Jones, Mary Meehan, Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

ILLUSTRATED

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1932, by

Cupples & Leon Company

Rex

Printed in U. S. A.

| I. | How Rex Got His Name | 9 |

| II. | The Firm of Rex and Tom | 27 |

| III. | The Hunt | 44 |

| IV. | Narrow Escapes | 63 |

| V. | The Kidnappers | 76 |

| VI. | 'Cross-Country | 87 |

| VII. | Wild Dogs | 97 |

| VIII. | Trapped | 111 |

| IX. | The Storm Breaks from the Hills | 122 |

| X. | On the Trail | 135 |

| XI. | A Battle in the Dark | 151 |

| XII. | To the Rescue! | 169 |

| XIII. | The Den of Thieves | 178 |

| XIV. | Rex Takes Command | 204 |

| XV. | Victory | 225 |

"I wish you'd take the little feller home with you," said the village blacksmith, as he lifted the bay mare's left hind foot to pare the hoof.

"The little feller" was a small, inquisitive dog that promised to grow up from his present vest-pocket size into a fine, upstanding specimen of Belgian police-dog.

"I don't want him," said Farmer Alfred Mason, who had brought the mare to be shod. "I've got two dogs up at the house already. The question isn't so much what I'd do with him. What would they do with him?"

The blacksmith pulled the bellows and blew his forge-fire to a rosy heat that shone in his own face. "He's a fine little pup," he insisted. "I don't know who owns him or where he came from. He blew in here a coupla weeks ago and since then nobody's claimed him. He's always under my feet and I'm afraid one o' these here horses some day'll step on him an' squash the life out of him."

The small dog was certainly interested in everything that was going on. With no mother to guide him, this youngster, possibly six months old, was bound to learn for himself all he could about the great round world so full of a number of things.

"Now look at him," said the blacksmith, a note of real liking in his large, rough voice. The man of iron never ceased to drive the nails as he glanced sidewise at the pup. The little animal had an air of superintending and even criticizing the shoeing of the mare. He stood with his ears cocked up, his head on one side then on the other, his bright eyes agleam, now and then uttering a little quavering whine, a sound as small as the whistle of a peanut stand: and it didn't mean unhappiness; it was his way of trying to talk to the men and the mare.

The mare paid little heed: it was beneath her massive dignity.

But Farmer Mason was almost tempted to say: "I'll take him." Mr. Mason, bluff, bearded, hearty and middle-aged, was a great lover of animals. At the hilltop farmhouse a mile away where he lived with his wife and his fourteen-year-old boy Tom, he had a small zoo. It now included white rats and mice, two alligators, two terrapin, a bad-tempered parrot, a Maltese cat, a red squirrel and the two dogs mentioned, named Alphonse and Gaston because they were always pestering each other.

When Mr. Mason thought of taking the dog home, he had a mental picture of all that outfit already domesticated, and the bother one more dog would make. Of course Mother would say to the little stranger that there was plenty of room. But it would be imposing on Mother's good nature. No, no, it wouldn't be fair: Tom had brought home enough birds with crippled wings, enough homeless cats and dogs, enough ailing little creatures to be housed and fed already.

"Sorry," Mr. Mason said to the blacksmith. "I'd like ever so much to have him. But we're full up at home. You just ought to see what we've got there now. Tom brought back thirteen live crabs from the shore two nights ago and had them sleeping in his wash-basin."

"What became of them?" asked the blacksmith.

"We ate them," was the answer. "And Tom hasn't quite forgiven us. He had given them all names. He said he knew them apart."

"Well," sighed the good-hearted blacksmith, as he hung up his pincers and took off his apron, "I certainly would like to find a kind home for the little feller."

Mr. Mason rode the mare homeward up the long hill-road to the farmhouse, and as the freshly-shod hoofs clicked and clashed on the stones through the dust-clouds of a dry midsummer, he almost regretted that he had not brought the dog back with him.

"It would sort of make it up to Tom for losing those crabs," he reflected. "After all, one more dog when you've got two already isn't so many. But I guess it's all right as it is. Gid-dap, Jenny!"

Then he heard a soft whimper from the dust, and looked round.

It was the small dog, trotting after.

"Oho!" he exclaimed. "So you've taken matters in your own paws, have you, youngster? You just thought you'd tag along behind anyway, did you? Go home, sir, go home!" But the tone was not very threatening.

Perhaps because he had no home to go to, and the direction therefore meant nothing, the dog stood still, and looked at the man, irresistibly.

"Don't look at me like that, puppy," said Mr. Mason. "Honest Injun, we haven't any room for you. Unless maybe"—he weakened—"you were to go and sleep in the barn with the calves and the pigs. And just suppose our old Alderney bull got after you. He'd make mincemeat out o' you in no time! He'd just swallow you up in one mouthful! Go home, now, go home!"

But it didn't sound much like a threat—it was more like an invitation.

The little dog not merely stood his ground, but came closer, keeping his eyes fixed on the man's face, as if reading what the face meant and not greatly minding what the words said.

So Mr. Mason, being the man he was, had to give in and admit defeat.

"O well!" he exclaimed, "if you want to come along as much as that, I suppose it wouldn't do so much harm. There's a lot o' rats around the corn-crib lately, anyway, and Alphonse and Gaston are getting too fat and lazy to chase 'em off."

Then, more to the mare than to the dog, he added: "Come along!"

But the dog would have understood the permission, and taken it all for himself, if the man had said it to the clouds and the trees.

He seemed to grow inches taller in a second. No scraping on his stomach in the dust. No fawning, groveling and wheedling now. And no slinking along behind and stopping when the mare stopped.

"My, my, look at that dog run!" exclaimed Mr. Mason to the pointed ears of Jenny. For she was interested, too, as the dog sprang blithely ahead, and rummaged in the ditch to startle a frog this side of the fence or a meadow-lark on the other.

Then, as the dog came back to report to the disdainful Jenny what he had smelt and seen, Mr. Mason laughed aloud. "Why, the little rascal's actually grinning! He knows he's put one over on us!"

By the time they reached the house the dog had covered at least three times the distance the road made it. Could a dog wield a pencil, he could have drawn you a map showing every nest or hole for a strip a hundred feet wide on either side of the road. He could have told you where a woodchuck had lived last season. In this place somebody had crossed the field, crushing the thistles; here a man had slept—and why should he sleep out in a field, instead of under a roof like other men?

Perhaps Mr. Mason in his own thoughts had answered some of the dog's keen questions.

For the farmer had been saying to himself:

"Now a dog like this might be trained to be a mighty good watch-dog. He doesn't seem to miss much. Seems to have his eyes in the air and his nose on the ground at the same time. When you've got a farm a mile from everywhere, like this one of ours, and it's the open season for tramps, it isn't a bad idea to have a dog of this kind around. I don't know. Maybe he'd be too friendly. Some dogs are. It'd be ideal if we could train him so's he'd be amiable with Mamma and Tom and stand-offish with strangers till we told him they were all right. Maybe it'll work out that way. We'll see."

When they got to the house, there was more than a lukewarm welcome for the little new dog from Mother.

Mrs. Mason was the kind that loves to entertain people, and, to her, dogs and horses were people. She was fond, nearly to the point of foolishness, of almost every sort of animal. She was glad that a red fox in winter made his home in an old drain-pipe under the barn. There were bird houses on every other tree—little ones for the wrens, bigger ones for the robins or the cardinals—and there were bird-baths up and down the garden, which were used with a great flutter and spatter to the music of carols on a summer morning.

Man or boy,—dog or horse or bird,—you would have to answer the loving-kindness of Mrs. Mason's mild blue eyes. She mothered everybody, speaking or dumb, four-legged or two-legged.

So when her husband reined in Jenny at the horse-block and she saw the little new dog in Jenny's quivering shadow, she said, "Another dog, Alfred? How nice! He's a young police dog, isn't he? How did you get him?"

"I didn't get him," laughed her husband. "He got me." And thus the dog, still lacking a name, was adopted into the homestead, if not the household.

Tom, the only son, was unspeakably pleased with his new playmate. Tom never could get enough pets anyway, and was always begging his indulgent father and mother for more. At the age of fourteen, he was just a normal school-boy, freckled and shy, all arms and legs, always growing and always hungry, with no particular gifts or graces of which to boast. Dogs he liked better than most of his relatives, because dogs never asked him how he got on at school and which of his studies he liked best. They never gave him good advice, and they never told him things he mustn't do.

When summer came, and Tom was home from school, he was out and abroad over the landscape most of the daylight hours, usually with a string of animals trotting at his heels. When he went swimming in the pond, dogs' heads were about him like young seals. Alphonse and Gaston, fat and puffy, didn't care for swimming, but other dogs gladly reported for duty as boys might run to a fire, from near and far. On the other side of the pond was the railway, about two miles from the Mason farmhouse, and where the highway crossed the rails, outside the village of Waynesboro, was the hut of an Irishman, who had nothing to do but hobble out on the track when the trains came along and wave a red flag at motorists, who, he thought, had a poor right to be on the road anyway. Tom and this Irishman, whose name was Mike Farley, were great friends.

As the summer days went on, Tom and the latest addition grew to like each other better and better. At first, the dog went by the name of Tatters, but Tom wasn't satisfied with that. "He's too—well, noble!" he explained to his mother. "He's getting to look like a prince or something. I guess he's the best dog there is anywhere around here. When he gets to be a great big dog he'll be a wonder to take care of the farm at night and chase away thieves."

That was said just after Abner the hired man reported that thirty-four chickens had been stolen, and dozens of eggs, worth a dollar a dozen. Suspicious characters had been reported loafing about the nearest farm and Mike Farley's little sentry-box. Mike began to carry an old rusty pistol, which he showed with great pride to Tom, saying that his father had carried it in the Civil War and it had never been used since.

Tatters, as he grew in length and strength, and filled out amid-ribs, made friends right and left with dog and man for miles around, since he was a born explorer.

But Alphonse and Gaston were not pleased with him. Those ungainly King Charles spaniels scowled and growled at his most civil advances.

They forgot their standing quarrel with each other, and combined against the newcomer. In every way they knew they told him that they had no use for him, and that a farm of two hundred acres was too small to hold the three of them.

But the fact that he lived with the cattle at the barn, and they lived with the people in the house, saved him many a lashing of their pale pink tongues, many a curling of their snobbish lips over their gleaming teeth.

One day Mr. Mason went down to the barn to look at a new-born calf.

The mother had a pedigree as long as your arm. She was living at the time in a roomy box-stall that gave plenty of space for a calf to take lessons from its mother, spreading its legs and stumbling, falling down and getting up again, and standing astraddle and sprawly like Tom when he was learning to use stilts against the barn.

Mr. Mason let down the top bar of the gate to the stall and climbed over.

Mother cow looked at him with something like resentment in her eyes, and gave a low throaty moo of remonstrance.

"That's all right, Allegra," said her owner, soothingly. "No harm, old lady. Just want to see how your child is. Now be a nice old lady, and get out of the way." For the cow had given the calf some kind of signal only understood between the pair, and the calf had moved over into a further corner where it stood protected by the mother's heaving red bulk.

"Co' boss, co' boss, move over!" the farmer coaxed, in a voice that was mild enough to persuade any cow, at other times, in other places.

But Allegra was not herself to-day. Her calf was very young and she was very nervous. She didn't want anybody fooling round her child. Her trust in man had turned to suspicion deep and dark.

Mr. Mason reached round behind the mother, and took the calf by the short hair on its sand-brown neck. The calf squealed and wriggled, and beat on the floor of the stall with its slippery heels. All these were signals of distress to the mother.

Suddenly, without warning, the cow turned on the man. With a bellow of rage, Allegra lowered her head like a charging bull and in blind anger drove her great curving horns against his blue shirt-sleeves.

Thus taken unawares, Mr. Mason was borne to the floor and found himself unable to rise, for nearly a ton of beef was upon him.

He shouted for help. But the men were far afield with the hay. The farmhouse was two hundred yards off, and his voice would not carry past the closed doors, though he yelled and kicked with all his might.

But Tatters had fortunately set apart that morning for a rat-hunt in the barn. Just now he was resting up in the loft, in the dark, between the cider-mill and a discarded churn. He had killed six rats, and thought he would be lazy and let the next one come to be killed instead of going after him. As he lay with his head snuggled on his paws, he heard the uproar in the basement.

At first he wondered if it might be thieves who had come to steal the chickens. But no—it was the well-remembered voice of his master, uplifted in entreaty.

"Help, help! Mary! Tom! Help!"

The voice grew weaker, and such roaring sounds as a cow is not supposed to make almost drowned out the human cries.

The dog climbed down the ladder—a trick of which he was not a little proud—and raced to the basement.

A strange sight met his brown eyes—his master lying on the floor of Mother Allegra's stall, the cow belligerent and bellowing above him, thrusting and shoving with her horns and the calf trembling and crying in the far corner.

In his own language he flew at the cow, and if he had not been a dog of polite breeding—at least since he came to the farm—you would have said that he was swearing awfully.

Perhaps, therefore, it is just as well to translate his remarks, instead of leaving them in the original dog tongue.

He was saying: "Look here, you great big, silly, crazy cow! Don't you know that your master and mine is the kindest, gentlest master in the world, and wouldn't hurt your baby for anything? Just look what you've done! You've made an awful mess of it. Here he is, all bloody, and you've probably broken his watch and several ribs and——"

But the cow continued to bellow and roar in a mad red rage and wouldn't listen. Legs spread wide apart, eyes fairly aflame, her nostrils flaring and her tail swishing, she seemed to be saying:

"Just let anybody come and try to take my child from me, and I'll show him what's what! I don't care who it is. Get out of my way, you insignificant little worm of a dog, and let me get at him again! I'll fix him!" And with her horns she began again to hook the prostrate, bleeding body of her master.

Then Tatters had a flash of inspiration. A ton of angry cow was too much for two hundred pounds of man, but he would divert the mother's attention and give his master a chance to get to his feet and scramble out of the way. So he flew at the calf, and grabbed it by the nose, and held on. He wasn't really hurting the creature, but it yelled as if it were being murdered.

At once the mother cow deserted the man on the floor and gave her whole attention to the dog. Tatters had the first big fight of his life on his paws.

Whatever became of the human being, the furious cow was bound she would kill the dog ere he could escape from the stall. Plainly her child was begging her to do so. You could imagine the red-spotted nursling boo-hooing: "Mother! He tried to eat me alive! He did, mother, honestly he did. Look at me, mother! He bit me in the nose!"

And the mother was answering back: "Leave that to me! I'll show him, the wretch! He was going to help that wicked man take you away from me. He sha'n't get out of this place alive. Just you wait and see. Get over in your corner there and keep out of the way, and your mother'll tear him to pieces, in two shakes of your tail!"

So the cow lowered her head and rushed at the dog, and Tatters leapt nimbly aside so that she only came crashing against the opposite end of the stall and got several of the splinters of board in her nose. That made her angrier than ever. She lost her horned head completely. She went roaring and smashing about till her own child was afraid of her, and no matter where she poked and prodded, Tatters wasn't there. And what is more, the little dog was laughing at her. In his own fashion he taunted and plagued her, and if you could put down his talk on paper for him it might have been: "You silly old cow, you! You think you can kill me just because there's so much of you and so little of me! But in that little, there is a brain in the top of my head, and I use it to keep out of your way. If I wanted, I could jump at your throat and hang on for dear life and you couldn't shake me off. But what's the use? Don't you see what has happened? While your back was turned, Mr. Mason has come to, and though he looks awfully white and weak and shaky, he has scrambled over the gate and got out of the stall, and you can't do him any harm at all. Now my advice to you is to take good care of your calf and don't think every time anybody comes to see it there's going to be a murder in the family. Anyway, as soon as the calf grows bigger you won't care about it at all. It'll be just the same to you as any other cow's calf. Now I'm going, in a hurry. This is no place for me. I hear Mr. Mason whistling to me, and I always obey his orders. Good-bye, cow! Good-bye, calf!"

And with a rush and a quick spring the dog was at and over the gate of the stall, and the cow lunged after him to prod him with her horns, but she was seconds too late.

Of course after that, they couldn't do enough for Tatters up at the main house. But the first thing they did was to change his name. Tom said: "Didn't I tell you, Mother, there was something kind of—kind of kingly about that dog?" He was beginning to study Latin and had learned that Rex was the Latin word for king. "You just can't call a dog like that any such name as Tatters. Let's call him Rex, 'cause he's a king of beasts. Anyway, Mother, do you know what I saw this afternoon? There he was, running all over the place, and Alphonse and Gaston after him. They were playing follow-my-leader: they were doing everything he wanted them to do. You never saw anything like it. Why, he's taken all the growl and snarl out of 'em, and all the kink out of their tails. They seem to take orders from him just the way he does from Father. Anything he thinks up they have to do—or they think they have to. If he doesn't lose patience with 'em, they may turn into pretty decent dogs after all."

And that was the way Rex got his name. After that, he moved away from the cows and the horses, the pigs and the chickens, and had his own lined box beside the kitchen stove, where Alphonse and Gaston always slept. Or if he liked—and he often did like—he came upstairs and lay in a corner of Tom's room. Once when Tom sprained his ankle he spent a lot of time lying on Tom's bed and—Tom said—talking to him, while the rats down at the barn became uproarious. Thus the boy and the dog fairly grew up together, and there were tragic times when Tom had to go back to school and couldn't take the dog with him. But with every vacation came a joyful reunion.

"When I go to Heaven, Mother," said Tom solemnly, "I mean to take Rex with me, and if they won't let him in, then I really don't want to go."

When Tom came back to the farm from school at the start of Rex's second summer there, the dog was nearly a year and a half old.

By this time Rex, a strong, big fellow, had become a noted character for miles of road and many acres of meadow and woodland round about, all the way to the lonely Blue Hills that rippled the horizon a few miles north of the farm. Nearly everybody except Abner the hired man liked Rex. But Abner shunned and feared him.

Abner came down to the little Waynesboro station driving a rickety Ford, with Rex running ahead of it, to meet Tom at the train. The dog, every nerve and sinew of his lithe body in perfect working order, could run rings around the creaking and infirm machine.

The dog and his young master hugged each other like two dancing bears. Standing on his hind legs, Rex licked Tom's face and ears, jumped up and down with frantic yelps of joy, and acted like a creature who had lost his reason.

Abner looked on, shaking his frowsy head in disapproval. "You hadn't oughta let a dog lick your face that way, Tom. It ain't healthy."

"Couldn't help myself!" laughed Tom.

Abner frowned. "Dogs an' cats is full o' germs. We been trainin' him different. We just got him broke so he don't scare the life outa people runnin' at 'em an' jumpin' up on 'em. You'll spoil him!"

"It's just his natural spirits, Abner," Tom pleaded, as man and boy clambered aboard the flivver. "That's what I like about Rex. He's lively. Always on the go, and ready to start something."

"Wisht he'd start this here car," said Abner, ruefully. "Most broke my arm a-crankin' her. Now I gotta do it again."

He got out of the rickety machine, and made further vain attempts.

"We ought to have a self-starter, Abner."

"We have. This ain't your father's machine. This is my machine. Wanted to show you how she'd run."

"Where'd you get her?"

"Over to the county fair. There was a feller from the city had a carload of 'em. They was a big bargain."

"What did you pay for her?"

"Fifteen dollars."

"How long have you had her?"

"Got her yistidday." Abner opened the hood and peered in. "I guess somethin's bust. I don't know how to mend it. Suppose we leave her here and walk home."

That was Abner's way. He was easily discouraged. He was fine with cows and calves, but ineffectual with mechanism out of order.

"Let me see," said Tom. He made a brief examination. "Well, I wonder that you got her this far. She's all out of whack!"

Abner chewed a straw pulled from his own hat. "Guess she wouldn't 'a' got here at all, if we hadn't been runnin' down hill," he answered, gloomily.

A man who had been sitting on a baggage truck on the platform of the almost deserted little station slouched up to the pair and muttered gruffly: "What'll you take for the old roller-skate?"

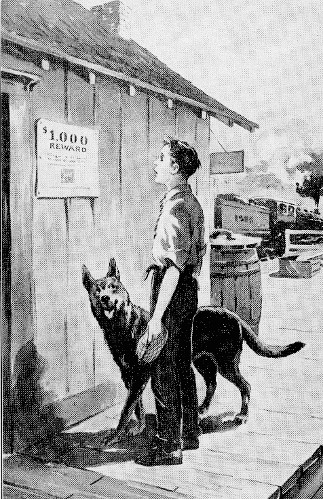

Tom looked at him. He looked like an out-and-out tramp. His hat was a rusted green, with holes where the black hair stuck through: it was evident that soap and razor had been strangers to his ugly face these many days. The narrow, evil eyes were bloodshot and the jaw protruded like a bulldog's, under a brick-red, scowling countenance.

Rex growled, and stepped critically round the stranger, sniffing and studying, as though he were taking notes that he might want to use on a future day.

"Be quiet, Rex!" Tom commanded.

Abner stalled, like the machine itself. "Where do you think you can go in it? 'Twun't be no good to you." That was a queer way to talk, if he wanted to sell it.

"I'm a mechanic," snapped the would-be buyer. "That's my trade. Anybody could see it ain't yours. Why," he went on, warming with enthusiasm for himself, "I bet I could fix her up in twenty minutes so she'd run!"

"Well, if you want her ez bad as all that," said Abner, "you can just give me twelve bucks for her, an' we'll call it square."

The stranger, to Abner's evident surprise, plunged his hand in his jeans and brought up a greasy wad of greenbacks, from which he slowly counted out the money.

It was paid and received in silence, except that each man grunted once, and Rex renewed his growling, as much as to say: "Who's your new friend? I don't like him. I think he's a crook."

And when the man went over to the shabby car, Rex pricked up his ears and watched him, every moment, as he tinkered with it.

"Wish you joy o' the ole wash-tub!" Abner cried as they walked away with Rex. But their customer was too busy fussing with the ruin to answer.

"Did you ever see him before?" asked Tom.

"No. That is, I don't guess so. Well, yes, come to think of it, I guess maybe I did. There was several of 'em. Maybe he was one of 'em and maybe he wa'n't. I can't say. I don't remember."

Abner had a lazy mind in the warm sun, and he hated to disturb its peaceful slumber. But when he once began to talk, he was often too lazy to stop.

"They was a bunch of 'em—five or six, I guess—came to the farmhouse one day lately and asked could they sleep in the barn. I said they'd better not, they might get chewed up. Then one of 'em—I guess maybe it was this one—says: 'What'd we get chewed up with, rats?' An' I says, 'No—dog!' An' then I whistled, an' for about the only time he ever done it, Rex came runnin' up to me, just like askin' me what I wanted. I was goin' to tell him to sic 'em, but I didn't have to. They said they guess'd they didn't wanta sleep in the barn, after all. Rex was lookin' at 'em just the way he looked at that feller just now. Once in a while Rex looks that way at me, and it kinda gives me the cold shivers. I never did see why your pap wanted to have a dog o' that kind. But I guess maybe it's just as well, with crooks like that foolin' around here. I dunno which makes me more nervous, that dog or them fellers."

They took a short cut homeward, along the railway embankment past the crossing where Mike Farley was stationed as flagman.

They found Mike placidly dozing, his chair tilted against his little sentry-box, although the afternoon freight was due in a few minutes. The whistle would have roused him if they hadn't.

"Mike!" shouted Abner, "Tom's home!"

Mike, though he did not rise, lowered his chair's two front feet and his own slowly to the ground, and opened his eyes to their widest blue.

"Welcome home, b'ye!" he exclaimed good-naturedly, as he put out his big hand. "We've missed ye. Glad ye're back. How's yer ma an' pa? They ain't been by here lately. Too busy, I guess. Or maybe I was asleep. I hope not. I hear you got a car over to the fair yistiddy, Ab."

"Yes," said Ab, glumly. "I did. But I sold it."

"To who?"

"A fellow I met down to the station jes' now."

"Why?" asked Mike, beginning to unroll his red flag to give warning of the train.

"It bust down."

"They always do, sooner er later, Ab!" Mike nodded his head sagely. "I told ye 'twas a waste o' money. Who was the fellow ye stuck with it?"

"I dunno his name. I think it was one o' the bunch I told ye about that come to the house an' wanted to sleep in the barn."

"Oh!" said Mike. "Them iron-workers that was thrown out o' the Lamson foundry the other day. They're a bad lot. They was tryin' to wreck the machinery, is what I hear, 'cause the boss wouldn't give 'em any more money. They've been hangin' round here, expectin' him to give in, I s'pose. But he wun't. No, siree, he wun't. I know him. Used to work for him. His name's Jim Sparlin. Hard as the nails he makes. An' loves fightin'. They can't lick him. Ain't no use for 'em to hang round here any more, after he's told 'em to get out. Only I don't want 'em here when the pay-car comes along. Some of 'em's always rambling up an' down the track an' hauntin' round the station lookin' fer trouble. The new ticket agent told me several of 'em wanted to sleep in the station the other night. That was the night you wouldn't let 'em sleep in your barn, I guess. Or maybe the dog wouldn't. I tell you, that's some dog! Goo' boy, Rex, goo' boy!"

He hobbled to the middle of the road and stood there waving his red flag as the freight train hove in sight, chugging round the curve through a deep cut, with a pall of black smoke for the up-grade, and a shrill, long-drawn whistle for the station.

As it crashed and rumbled past, engineer and brakeman waved to Mike a friendly greeting.

"When the pay-car comes along does she always stop here?" Abner asked Mike, in a tone that was meant to sound indifferent and still betrayed a good deal of interest.

"You bet she does!" exclaimed the Irishman. "I go aboard her, too. Used to have to go up to the station to git my money. But since the rheumatiz took me so bad in the right leg they stop for me here. Just long enough to climb aboard an' sign the book an' git a good cigar outa Bill Sykes an' tell 'im a story an' git off again."

"Well, I guess we'll be goin' on upta the house." Abner turned to Tom. "I was goin' to give you a ride in my car. But she ain't no good to me now. Ne'mmind: I only lost three dollars on her. That ain't so much."

Tom whistled to Rex, who was rummaging among charred stumps on the other side of the track, and the trio started up the long, slow hill to the farm. Tom was full of stories of the life at school, to which Abner listened, poking in a "hum" or a "haw" now and then, to show that he heard. But he was not a very exciting audience.

Pretty soon he pulled a brown bottle from his left hip pocket.

"What's that stuff?" asked Tom.

"I hafta take it," answered Abner. "Doctor told me to. Tonic for my liver." He applied it to his lips. If it was medicine, it must have tasted unusually good, for he smacked lusciously and then he took what he called another swig, just for good luck.

At the farmhouse that evening, Tom told his parents about the accident to the car, and mentioned Abner's medicine.

Mr. Mason looked troubled. "It's awful stuff," he said. "It'll be the death of him. I've warned him often enough."

"He's been acting so queerly lately," Mrs. Mason remarked. "There's something curious about the way he got that car yesterday and sold it again to-day. Do you suppose it really broke down, or that he was only pretending he couldn't fix it?"

"Why should he be pretending, Mother?"

"I don't know. Maybe he was a friend of that man, and wanted him to have it."

"But Mother, they didn't act as if they knew each other at all. They didn't talk to each other like friends."

"Well, of course I don't know," Mrs. Mason admitted doubtfully. "I just had an idea, with this drinking and everything, and those queer men hanging round here, that maybe——"

"Maybe what?" Mr. Mason lowered his newspaper and looked at Mother over his glasses.

"Oh, I don't know," said Mrs. Mason.

"I wonder why he asked Mike Farley about the pay-car, Father?"

"What did he say to Mike about it?" inquired Mr. Mason.

"He asked if the pay-car always stopped at the crossing."

"O well," said Mr. Mason, turning to the next sheet of his Wayne County Weekly Gazette, "Abner and Mike have known each other quite a while. I guess Abner just asked the question to make conversation. I told Abner to-day he could look for another place. He gets drunk too often. I'm sick and tired of him. I've lost all patience with him."

Mrs. Mason heaved a sigh of relief. "I'm glad of it, Alfred," she replied. "I never really trusted him. The sooner he goes the better.—Look at Rex. You'd almost think that dog takes in every word we're saying!"

Long afterward they recalled how Rex's eyes shone in the radiance of the new electric lamp that evening. There he lay, nose on paws, looking up at them—ready to caress a knee or nuzzle a hand if offered the least encouragement to do so.

"I tell you," confessed Mrs. Mason, "I'm getting as fond of that dog, almost, as though Tom had a four-footed brother. Tom, when you're away at school I get to missing you so much I'd almost die if Rex didn't comfort me. He's a big help. We're great pals, aren't we, Rex?"

The dog thumped his tail on the rag carpet, meaning yes with all his might.

That same night, about midnight, Tom in his third-story room was dreaming beautifully—all the nice things of which a boy could dream after his first day of summer freedom.

He dreamed, for one thing, that he was flying in a bi-plane with silver wings high over the hills. He was going in a spiral, up and up. Rex was sitting beside him in the cockpit of the plane, barking at all the world below, and especially at the dogs of the different countries they were crossing—Brazil and India and Africa and Japan, all in a few minutes. There were mountains with snow on their tops, and there were roaring seas, with ships that plunged ahead through gales and lashing water-spouts. And then the plane passed directly over the red-hot, flaming top of a volcano, and Rex was barking louder than ever. The smoke rose in choking billows, and Rex was tugging at Tom's sleeve as if to tell his young master that it was very dangerous to stay there, and they must fly away as fast as they could....

Suddenly, as if his plane had crashed to earth with him, Tom woke to find that whatever he had been dreaming, the fire was real.

Smoke was pungent in the air, and it poured into the room under the crack of the door so thick and strong that he could hardly breathe. He rushed to the open window.

Down below his father and mother, hidden by the smoke, were calling him, and Rex barked loudly.

"Coming!" Tom screamed. He snatched up coat and trousers and threw them on.

Then he sprang to the door of the room. It was locked.

Abner's room was next his own.

He ran back to the window, climbed along the rain-gutter, and found his way to Abner's room. Abner was not there.

The bed had been slept in, but Abner's clothes were gone, and his big carpet-bag was missing.

Tom sprang to the window. In the red glare his father caught sight of him, through the smoke-clouds.

"Tom!" Mr. Mason shouted. "Come down! Where's Abner?"

"I don't know!" Tom called back.

The boy wrenched open the door and ran into the hall. The house was full of smoke, and as he looked over the banisters he saw flames licking and leaping below.

That way of escape was cut off.

Once more he sought the window. There was no porch on that side of the house. The winter shutters had been removed. It would have been a drop of more than thirty feet from the sill to the ground.

His father, with Rex at his heels, ran into the house. At the foot of the stairs a wave of fire met them, as from a seething furnace, and Mr. Mason recoiled from it.

But Rex refused to stop for anything. Up the blazing stairway bounded the gallant animal several steps at a time.

"Rex, go back!" Tom cried—but the dog kept on.

And he came just in time.

For Tom was so choked and blinded by the smoke that he no longer knew what he was doing.

As Rex sprang to him, the boy fell upon the animal in a dead faint, his arms tightly clasped round the dog's neck.

Losing not a second, Rex put forth all the strength left in his stalwart frame, turned to the head of the stair and began to drag the half-conscious boy down the stairway.

Rex's hair was afire, and Tom's clothes were burning, too.

Step by step the dog tottered downward into the seething, writhing flames.

It was as if he walked directly to his own destruction.

He could go no faster, for at any instant the boy's fingers might relax their hold.

The flames leapt about him like devils that would snatch away the precious burden if they could.

Once Tom was roused, as they reached the landing, half-way to the second floor.

"Good—old—Rex!" Tom said, but he did not know that he said it.

Round the corner Rex dragged him, and the floor was all but burned through. The rafters sagged and at any instant might collapse into the living-room.

Just then Tom let go his hold and fell, rolling over and over to the bottom of the stair.

The dog stopped an instant as though he could not follow.

The fire was round him, in a high leaping ring, and the smoke coiled through its rage, in angry billows like sea-waves under the lashing of the storm.

With a defiant toss of his head, and the light of the fire gleaming in his eyes, Rex plunged on down to the foot of the stair, before the open front door of the house.

Then he seized the belt of Tom's Norfolk jacket in his teeth, dragged the boy out into the open, and fell over at the feet of Tom's father and mother as though dead.

When Tom came to, he was in his father's arms, by the lilac hedge. His mother was bathing his face and forehead from a tin dipper. Rex, revived, looked on anxiously. Round about them were scattered the few things that Mr. and Mrs. Mason and the faithful cook Martha had been able to save.

"How did it happen, Mother?"

"You know as much as I, dear boy."

"Did somebody set the house on fire?"

"I think Abner did it," Mr. Mason put in. "He wanted to pay me back for getting rid of him. When Abner gets drunk, he goes mad—he'll do anything.—God bless that dog!"

Mrs. Mason put her arm about the animal's neck, and he pawed her knee. "He saved Tom's life," she said in a low voice with tears in it.

"I don't know what happened, Mother. I just remember falling on Rex's neck, and holding on to him. Then I think I must have fallen down the stairs. He must have pulled me to the door when we got to the bottom. Isn't he a wonder?"

By this time a few of their distant neighbors had come, several in their cars and the rest afoot.

But there was nothing they could do. The ancient farmhouse was dry as a bone, and with such a rushing start it was a smoking ruin long before the summer dawn.

There was an old, abandoned house across the road, which Mr. Mason owned, and into it they promptly moved. They wasted little time in vain regrets.

"We've lost just about everything," was the way Mrs. Mason put it. "But things don't matter, compared with those we love. Thank God, only poor Alphonse and Gaston lost their lives. We'll make this house into the cosiest, happiest home that a father, a mother, a boy and a dog ever lived in."

And if you came by several weeks later, and saw the repainted house, with the crimson rambler over the door and the white curtains at the windows, you would say they were succeeding.

But Abner had not returned, and they often puzzled over the riddle of his disappearance.

Two weeks after the fire, Tom and his father went hunting with Rex in the Blue Hills, six miles to the north of the farm.

The Ford, kept in a shed next to the barn, had been saved from the fire, and Rex, who loved motoring in all its forms, hopped gaily aboard.

As they skimmed along the dusty road up which Rex came the first day he ever saw the farm, the dog was turning his head like the weather-vane on the barn, to make sure he wasn't missing anything.

He was full of the joy of life, and he was in such fine condition that the burns he got in the fire had healed already. He talked in his own way to the clouds and the breeze and the sun and the swift birds, hearing and seeing everything, it seemed.

Now and again he spied another dog by the road or in the distance, and—however far away—barked a greeting or a challenge.

The road went directly by the cabin of Mike, the switchman, and instead of a mere passing nod from the flivver they all got out to be sociable a minute with the genial, lonesome Irishman.

"Begorry," said Mike, "I hated to miss the fine big fire ye had. But I could bring ye nothin' to put it out, an' I didn't know till it was over. D'ye know who it was did it?"

"I think Abner must have done it, Mike," Mr. Mason answered. "He had a grudge against me. And I haven't seen him since."

"Well, I've seen him," Mike clenched his fists. "Entirely too much of him. Three times he's gone by here in an old car with one o' them fellers from the iron works—I guess it was the feller he sold the car to. They wanted to borrow money, an' cussed me because I gave 'em none. And I don't think they're hangin' around here for any good. Each time they asked me when the pay-car would be comin' along."

"When does it come?"

"Sh-h-h!" Mike held up a warning finger and looked round, as if telling a state secret. "Next Saturday afternoon about five o'clock."

"Maybe you'd better not be here alone when it comes, Mike," advised Mr. Mason.

"Don't you worry, sor! I'll have a coupla big-fisted fellers here'll make trouble for 'em if they try to start something. Anyhow"—he wiped his hot forehead on the sleeve of his blue-striped jumper—"the crew o' the pay-car could most stand off the German army, I guess, with all the guns 'n' things they got aboard."

Through Mike's valiant bluster you could detect the hollow ring of a shaken confidence.

"What's Rex doing?" Tom exclaimed.

Rex, nose down to the red clay, was making his own slow trail along the road in the direction of the hills.

When Mr. Mason called, the dog stopped, and when the call was repeated he returned, as though reluctant to leave off.

"Maybe he's got Abner's scent." Mr. Mason patted the dog's shoulder, and caressed him behind the ears.

"It's a pretty strong scent," Mike said. "He wouldn't have to go fur to git it."

Mr. Mason laughed and then looked serious. "Mike, I think maybe I'd better be on hand Saturday afternoon, in case you need help when the pay-car stops here."

"Oh, no, don't you bother." The Irishman tried to sound care-free. "Them pay-car fellers can look out for 'emselves."

"But suppose they came along after the pay-car left, and held you up?"

"They wouldn't get much," Mike grinned. "Are you goin' over to the Blue Hills?"

"Yes. The wildcats are getting pretty thick, and there are some bears, too, and they asked me if I wanted to come over and help thin them out." Mr. Mason was a famous shot, and not a hunt in the neighborhood, for many miles around, was considered complete unless he and his faithful Winchester went along.

"Anyway," Mr. Mason continued, "I'm curious to see what the dog can do. He hasn't been to a big hunt yet with me."

"I bet he'd be a wonder in a man-hunt," said Mike. "Guess he knows 'bout everything you say, don't he?"

"He's a regular mind-reader!" put in Tom, eagerly. "He's been hunting a lot of times we don't know anything about."

"Well, daylight's precious: we must be getting on," his father exclaimed. "I want to get back to Mother by sundown. I don't suppose Abner will bother us again, now that we've lost pretty nearly everything in the fire. But it's rather lonesome for her with nobody but Martha.—Good-bye, Mike!"

The road passed into a lonely glen in the foot-hills, and narrowed. There were bold crags on either hand with young oak-trees jutting from the crevices. At a little old bridge they stopped to get water for the radiator from the loudly quarreling stream, while Rex hopped out and took a bath and a good long drink. He loved water, and never missed a chance to take a dip in pond or brook.

Round the first bend beyond the stream was a small house by the road, and Bill Adams, famous hunter, tall, grizzled and raw-boned, was sitting on the stoop waiting for them, his shotgun across his knees.

"Howdy, Mr. Mason! Howdy, Tom! Well, Rex, you've been gettin' a joy-ride, haven't you?" Dog and man were on the best of terms. Rex nearly wagged his tail off as Bill stroked his head. "It's a good day to go huntin', Mr. Mason. That dog o' yours'll be a big help. The animals is gettin' too thick around here."

"Done any damage to your chickens?"

"Yep. The pesky varmints! If there's anythin' a hungry wildcat won't take a fancy to, I'd jest like to know what it is! They come round here nights howlin' somethin' scandalous, like all the devils let out o' hell. Guess you could most make your way along this road by their bright eyes shinin' in the leaves o' the trees."

"Come now, Bill, we know you're a mighty hunter," protested Mr. Mason. "But that's laying it on a bit thick."

"That's the truth, sure as I'm six feet three in my stockin' feet.—Well, let's take the path from behind the chicken-house. That's the one the critters come along mostly. An' believe me, they do come!"

As the procession started, Rex in the lead, Bill kept up a running fire of his memories, most of them quite as tall as himself.

Bill's reputation for stretching the truth was about equal to his great name as a gunner. It was no use to contradict him with the facts—he could wiggle out like a weasel from a hen-roost.

"Yes, sir, as I was sayin', the wildcats certainly is thick in these parts.

"One winter night when I was comin' home from Waynesboro by the short cut through Perry's Woods, I had on a fur cap stood up on my head like a rabbit's ears.

"I come to a place where the branches hung down low over the path, all covered with ice. There was a wildcat settin' thar in the branches I didn't know about.

"Suddenly I see a gleam o' eyes like diamonds, an' out come a long paw with great hooks on the end.

"It was the wildcat reachin' for my hat, thinkin' it was a rabbit. I let the cat have it, 'cause I didn't have nothin' to argue with.

"My, how that cat did cuss an' snort an' rip and tear round with that hat! You could 'a' heard it yellin' an' screechin' from here to Kingdom Come.

"A few nights later there was an awful to-do bust out in the hen-roost, an' I rushes out there, an' what does I see?

"I see my hat, cavortin' in an' out among the chickens, an' every now an' then a paw reachin' out from under it an' killin' a chicken.

"I give a yell, the hat goes rip-snortin', toward the chicken wire, an' then that there ole cat wriggles outa it an' goes skedaddlin' away as fast as a airyplane.

"Yessir, that cat had been usin' my cap just like it was a fur coat, it was so freezin' cold, an' if it hadn't 'a' come off, it woulda been wearin' it yet.

"I can prove it—'cause see, it's the hat I'm wearin' now. Feel it"—he handed it over to Tom—"and you'll find there's big holes in it, lots o' places, where the wildcat stuck his paw through.—Say, is your dog a tree-climbin' dog?"

"He can climb a little way," Tom asserted proudly. "There's a tree at home he goes up, as far as the first crotch in the branches."

"Well, I had a bird dog once," lied Bill cheerfully, "that didn't wait for the birds to come down to the ground. No sir-ee. He'd rush right up a tree after 'em, he would. He'd run right out on the end o' the topmost branches an' catch the birds fast asleep. Sometimes he'd catch 'em sittin' on their nests and wring their necks before they'd wake up. But I had to cure him o' the habit o' eatin' birds. Too messy.—Look a' that dog o' yours! Bet he sees a cat. You'd think he was froze stiff."

Rex was standing at the foot of a big, thick oak-tree—one of the patriarchs of the forest that had somehow outlived the fires that too often swept the mountain.

The dog did not bark to alarm the wild things near and far, but stood motionless as a pointer, like one of these cast-iron dogs people used to put on their front lawns.

"Bet I see the pesky varmint," Bill whispered huskily.

His big forefinger was held like a pistol toward a large dusky lump next the tree-trunk where a low branch projected.

Though there was plenty of sunlight above the canopy of the trees, little found its way into the leafy gloom below.

"The dog's a-goin' after him, blest if he ain't! Git ready to shoot!" commanded Bill, suiting the action to the word.

Rex ran back from the tree a little, in a half-circle.

Then he came rushing at the tree as if he were out for a record.

The trunk sloped, and the bark was heavily ridged. At the first attempt, his claws slipped, and he fell back from a point just below the branch at which he was aiming.

Then he tried again, and again he fell back on the stones and the roots. But he was not a dog to be easily discouraged.

A third time he tried, with might and main, and this time he scrambled up into the crotch.

The dusky lump had retreated, hissing and spitting, out toward the end of the branch till it bowed down and started to crack. Meanwhile the wildcat yelled like a pack of fiends, a cry between a moan and a groan, rising to a mad, derisive screech like the laugh of a hyena.

Bill raised his gun to shoot before Rex crawled out too far on the branch and came too close to the wildcat.

Then the cat leapt like a huge flying squirrel, and landed on Tom's head.

All Tom knew was that a mass of gripping white teeth and tearing nails had fallen on him like a fuzzy cloudburst of cat.

The others rushed to his aid, but the dog was ahead of them.

Without hesitating a second, Rex leapt from the branch on the raging animal below.

Then it was for the dog and the wildcat to settle the dispute between them, for no outsider could help Rex now.

The cat was smaller, but it was a most formidable foe.

For all the tiger was in the blood and claws and teeth. Here was no domestic pussy, playing Robin Hood for fun in the woodland. But it was fifteen spitting, fuzzy pounds of pure deviltry, with barbs and spikes—it seemed—on all sides and at both ends.

Dog and cat rolled over and over, and even Bill, hero of countless frays and forays, didn't try to pry them apart, and didn't dare to shoot for fear of hitting Rex instead of the wildcat.

Tom got to his feet, white and shaky, bleeding at several places, bruised and sore all over. His jacket was torn in shreds.

But all he cared about was Rex. If anything happened to the dog——!

Rex was very well able to take care of himself. The enraged screams of the wildcat grew weaker. Presently with a final howl of despair and defeat, the wildcat relaxed the hold of its jaws on Rex's thick pelt, quivered and lay still. Rex gave the creature a final shake or two by the neck to make sure, and then lay panting beside his prey, heeding little the caresses and congratulations.

Not a shot had been fired in the fight. The blood was all over the rocks and the gray dead leaves. There were bits of fur, some of them Rex's, some of them the wildcat's, scattered about as tokens of the fierce encounter.

"Mebbe that's about enough for this time," said Bill. "Shall we call it a day?"

But Rex wouldn't have it that way. His nose was always telling him strange tales that a man couldn't get—and it seemed to be telling him a new story now.

For already he was on his feet, and his nose was on the leaves close to the path.

"What's he got now?" Bill wondered aloud.

"I'll call him off if you say," Mr. Mason suggested. "He must have killed the king of them all. I think he's entitled to a good long rest before he goes up against another. Let's quit now, and come back another time."

But Rex had started into the deep woods, away from the path.

Bill pushed down the branches and watched the dog intently. "Do you know what he's got now?"

"What?" exclaimed the boy and his father together.

"I bet it's a bear. The way the branches is broken an' the ground looks, it must be a bear. They's been several of 'em around here lately."

"If it is a bear, it won't give him much of a fight, Bill."

"No—a ordinary bear wouldn't. But Tom Sykes told me they's a mother bear with little ones a-prancin' round these parts somewhere. He saw 'em once. If Rex meets up with that mother bear where them cubs are he'll be sorry. What happened just now won't be a patch on the scrap there'll be if he ever finds her."

Rex came running back as if to put a question.

"What is it, old boy?"

Rex nosed the ground, and then looked up eagerly.

"I think I know what he wants to tell us, Father. He means it's something strange and new, something different from the first trail that led to the wildcat. He just wants to ask our permission—and he wants to know if we're coming along."

"Forward march!" Mr. Mason cried.

The dog needed no other orders, and darted ahead, allowing himself a few joyful barks by way of exclamation points.

Over sharp rocks and shaggy windfalls of dead trees they clambered wearily, till they came to a den where several rocks were jumbled together under a projecting forehead of a cliff.

It would have served well as the lair of bear or wolf, or the rendezvous of pirates, a good place to hide their gold.

Tom got down on hands and knees and crawled in between and under the rocks at the entrance.

Then he backed out hastily. "Father!" he cried. "I saw two eyes shining in there!"

Rex, eager as he was, had stood aside to let the boy push his way in if he chose.

As the lad withdrew, Rex presented himself, a more than willing volunteer.

"Don't let him go in, Father!" Tom pleaded. "The bear'll kill him."

They all stood still and listened.

Then Bill spoke. "That ain't the old mother bear," he said. "It's the young uns, waitin' for the mother to come back."

Bill went to the entrance, stooped and peered.

"Great jumpin' Jehoshaphat!" he exclaimed. "There's somethin' in there that ain't no bear. It's a man!"

Mr. Mason came closer with his rifle. "Is he alive?"

"I dunno," answered Bill. "Mebbe he's drunk or asleep."

Then Bill lay flat and squirmed in, pushing his gun ahead of him. They could hear the bear-cubs beating a scrambling retreat, and calling for their mother, in a way that made Bill's venture very risky unless the Winchester should intercept her.

But Bill did not go far. He backed out hauling with him the body of——

"Abner!" exclaimed father and son in the same breath.

"Looks ez if he was tryin' to make his home in the same place with the bear's family," said Bill, grimly. "Wonder if the rest of that gang was here? If they was, they got away, an' this poor feller didn't."

"You knew Abner, didn't you?"

"Sure I knew him. He come by my house yesterday, crazy drunk. Wanted another drink, and when I give him water he swore an' wanted to fight me. I laughed an' he went off mad as a hornet, sayin' he'd get me one o' these days."

Abner's face, hands and body were torn as though in a desperate encounter with the she-bear.

"I s'pose," said Bill, looking down on the body not unkindly, "he crawled in there an' she cotched him asleep."

Then Bill knelt. "Le's see what he's got in his pockets." He pulled out a gold watch and chain. "Why, that's Mother's!" Tom exclaimed. "She thought she lost it in the fire."

They found nothing else of value.

But on a torn bit of brown paper were these words scrawled in pencil:

"Don't ferget to Be at the Pay Car Satterdy five o'clock with the Car."

Bill whistled. "So that's it! He joined their gang. They're goin' to use that ole flivver I seen 'em in lately. Mebbe we can put a crimp in their style. We'll see!"

There was a sudden crashing in the bushes.

Bill grabbed his gun, ready to fire.

"Come back, Rex!" called Mr. Mason.

Then a great black head parted the thicket of birch bushes, and the mother bear raged into the clearing ready to tackle all who stood between her and her crying cubs in the den.

Bill let her have both barrels, and the Winchester spoke at the same instant.

But for once, Mr. Mason missed, and the shotgun's charge was no more than red pepper to the furious animal. Before they could fire again, Rex was on the bear.

Locked in the grip of wrestlers, dog and bear rolled over and over. Rex wasted no breath in reply to the furious grunts of his antagonist.

The bear had her talons out like boat-hooks—you could imagine that you saw them flash like the blue steel of the rifle in the sun.

But Rex fought with the wary cunning of a grizzled old stager. Where had the young dog won such wisdom? How did he know enough to keep out of the way of the foaming jaws and gnashing tusks of the old she-devil, that had already done for Abner?

Rex had his vise-like grip on the bear's throat, and there he hung for dear life, as the animal rose on her hind feet, tottered and swayed, and hurled him this way and that, striving in vain to throw him off.

The little cubs, hearing the fuss, had come to the mouth of the den, and there they stared and cried and tumbled, afraid to come any further, piteously squealing to attract the attention of their preoccupied mother. But nobody noticed them.

The fight did not last long. Bill Adams saw to that. As bear and dog fell to the ground again, Bill produced a huge clasp-knife from his jeans, closed in upon the struggling pair, waited for his chance and then drove the blade between the bodies into the heart of the bear.

With a groan that was almost human, the bear's great paws went limp all at once, but Rex did not relax his hold as the huge shabby carcass fell over and lay still. They had to haul the dog from his prey, and even when Rex had taken his fangs from the lacerated throat he still stood gazing at the creature he had killed as St. George might have looked at the slain dragon. He was not angry now.

"Come on, old scout," coaxed Tom. "You've done enough to-day. One wildcat and one bear."

"Guess that's as many as the law allows," was Bill's grim comment. "We'll put some rocks over Abner's body and tell the coroner about him. Then we'd better look in the den and see if we can find anythin' else, except bear cubs."

They hid the body securely against beast or bird, drove the little crying cubs away with pity in their hearts for the small creatures, and then Tom pushed his way into the den, but found no traces of human occupancy.

Evidently it was not the fixed rendezvous of outlaws, but merely a place that Abner had unluckily chosen for a night's refuge. They would have to continue their search if they wanted to find the permanent abode of the men who planned to hold up the pay-car.

As they rambled homeward with Rex in the lead, they wondered where in the wild and lonely glens of the Blue Hills the others were hiding. Abner was evidently on his way to find them when the bear killed him.

"Them bear-cubs," said Bill to Tom as they said good-bye at Bill's door, "is big enough to get along without their mother. You needn't worry about that. But I wisht I knew where the rest o' that gang might be. They're liable to pop out on us any time an' surprise us. It won't be the first time crooks has been hidin' in the Blue Hills. There's other things oughta be cleaned out o' them hills besides wildcats an' bears!"

Rex might have been a very busy dog, had the attack on the pay-car come off on the Saturday afternoon to which the scribbled note, found in Abner's pocket, had pointed.

But though Mr. Mason, Tom, Rex, the new hired man and eight other men from Waynesboro hid in the bushes near Mike's hut and waited for the robbers to appear, nothing out of the ordinary happened on that Saturday. The pay-car came as usual. Mike boarded it as he always did and got his money, and disembarked, and counted his money a second time as he sat in front of his sentry-box, and nobody appeared except a flock of extremely noisy crows, and a couple of chicken-hawks high against the blue.

Tom and Rex were really disappointed. Tom said it all, for both of them, in Rex's sympathetic right ear.

"Rex, old boy, those robbers were going to do it—we know they were, don't we? But when they found that Abner, who got the flivver for them, had been killed when he broke into the old she-bear's den by mistake, they thought they'd hold off for a while. Tell you what I believe, Rex. They're living somewhere in those woods near the bear's den, or else 'way back in the hills—and they mighta been snooping around the day we went on the bear-hunt, and I guess they thought we were looking for them. But you wait and see, Rex. One of these days when they think everybody's forgotten about 'em they'll come out of the woods and try to pull off the hold-up. Then we'll get them.

"You see," he went on, rubbing behind Rex's ears in the way the dog loved, "they aren't the kind that can live in the woods—they never were Boy Scouts. And they know that Abner's body was taken away to be buried, and they could be pretty sure that the note they wrote to Abner would be found on him.

"So we'd better sit tight and be all ready for 'em any time—especially on a Saturday afternoon when the pay-car's due. The railroad people and the people in Waynesboro that know about it probably think they've given up and gone away forever—but we don't think so, do we? No sir-r-ee!" And he threw his arms round Rex's neck as the dog barked a ready assent to all he said.

Tom and Rex had made a confidant of Captain Victor Austin, the young pilot in charge of the flying field that the Eagle Aircraft Corporation had located not far from the old house into which the Masons had moved after the fire. Captain Austin with his wife and four-year-old daughter lived in a small cottage near the hangar and were all frequent visitors at the Mason home. There was nothing Tom and Rex loved more to do than to walk over to the flying field and watch the Captain and his mechanic overhaul the shiny bi-plane,—the "Eagle," it was named,—"tune up" the roaring motor and "take off" for short trips around the near-by country with passengers who had come out from Waynesboro for the ride. Tom had even been up in the plane and had flown over the wild Blue Hills where he now felt sure that the robber gang was hiding. He had told Captain Austin all about the discovery of Abner's body and how some day soon he wanted to put Rex on the trail of the outlaws. They talked it all over one afternoon while Jack, the mechanic, was repairing a hole in the aluminum painted Irish linen of the lower wing where a lady passenger who had gone up for a ride with the Captain had nervously stuck her foot as she clambered out of the front cockpit.

"When the chase comes off," the Captain said to Tom and Rex, "I want to be in it, with my plane. I can do more in the air than a big crowd can do on the ground.

"If they use that old broken-down flivver I don't know what road they'll take, but I can see 'em wherever they go and beat 'em to it.

"And if they've got a nest in the hills,—well, we don't have to kill 'em by dropping things on 'em, like the Germans, but we can easily make the place too hot to hold 'em with a few bombs."

On his way home from the flying field that evening with Rex romping at his heels Tom tried to imagine the consternation in the robbers' camp when the shiny "Eagle" with its skilful pilot and cargo of destruction should begin to drop explosives around their hiding places.

Dinner was ready when they reached home, and as Tom and his father sat down to their meal Mrs. Mason came in from the kitchen with a plate of Irish stew that she had put in the ice-box the previous night for Rex.

"I gave some to a horrid man that came to the door to-day," said Mrs. Mason. "I could hardly get rid of him. He asked what had become of the dog we used to have here."

"Did you tell him?" asked her husband.

"I did not." She put her lips firmly together, and seemed to be drawing away a little from the mental picture. "Then he asked for Abner—said he used to know him. I just said Abner had left us. He wanted to know if we had hired anybody in his place. What is the matter with Rex?"

For Rex, contrary to his usual habit of polishing off his plate rapidly, was sniffing dubiously at the meat.

"Are you sure the stew hasn't spoiled, Mary?"

"No, I put it in the ice-box over-night. Rex must be hungry. It's the first meal he's had to-day. It's all right, Rex."

Rex gazed at her as much as to say: "I'm sorry. I'd like to believe you. But if you knew what my nose tells me——"

"I wouldn't make him eat it, Mother," put in Tom. "He's a wise dog. Something may have happened to the meat that we don't know anything about. Maybe——"

"Well?"

"Do you suppose that man could have poisoned it?"

"No, because I stood by him every minute.... No I didn't, either. I stepped back into the pantry to see if the refrigerator door was shut. But I couldn't have been gone more than three or four seconds."

"Oh!" said her husband. "Did you leave the dish where he could put anything in it?"

"It was standing on the end of the bench, just outside the back door. I don't see how he could have."

Poor Rex! He sniffed hungrily at the savory dish set before him, but instinct told him not to touch it.

"There must be something the matter with it." Mr. Mason shook his head. "He knows better than we do. What else have we got that he can have for his supper?"

"There's a soup-bone I was saving for to-morrow," his wife reflected, her finger thoughtfully against her chin.

"Well, Tom'll give up his share and so will I! Won't we, Tom?"

"Of course!" the boy agreed, heartily. "Couldn't he have that rat that's in the trap in the barn?"

"He could," answered his father, "but I want that rat for something else. I'm going to put some of this stew in the trap and let the rat eat it and see what happens. For I think it's poisoned, and I'm pretty sure"—he paused significantly—"that man was one of the gang. Those fellows don't want work. They don't want their jobs back. They are a lot of crooks, that's all, bound to live off the country till we catch them and put them behind the bars. Maybe they killed Abner for fear he'd tell on them, and then left him in the bear's den to cover up their tracks, and make people think the bears killed him. I've heard of three burglaries lately at lonely outlying farms. We can't keep too close a watch. Mother, what did the man look like?"

"He had a very red face, and red hair, and a jaw that stuck way out."

"Did he have a scar on his cheek?" asked Tom.

"Yes."

"Then he was the man Abner and I saw that day at the station!" exclaimed Tom, excitedly. "Wonder what's become of the car he got from Abner?"

"He may have left it a little way down the road," his mother said. "Just after he left, I heard one starting up with a great splutter the other side of the hawthorn hedge beyond the hen-house. But I hardly gave it a thought, so many cars go by on this road."

Farmer Mason clapped on his hat. "Think I'll take a look at the hen-house."

The long summer evening made a lantern superfluous. But the sun was setting, and wise old mother hens were telling bedtime stories to fluffy nurselings tucked under their wings.

Fifteen minutes later he was back in the house, with a grave face.

"I had to nail up a hole in the netting big enough for a man to get through, and eight of my prize Plymouth Rocks were gone. I suppose the hunting yonder in the hills is not so good. Well, anyway"—he cast a meaningful glance at the shining barrel of his rifle in the corner—"it won't be long before we're hunting them. I was talking with Tod Rockwell to-day. They fired his hayrick, and he's jumping crazy to start after 'em any time and smoke 'em out, wherever they are. He's lost a couple o' pigs, too. Don't see how they got away with 'em: pigs are better than alarm-clocks in the night."

Rex took his soup-bone from the kitchen into the front yard, and Tom sat on the steps and they held their kind of conversation while the dog gave exercise to strong white teeth on the bone.

"Just suppose that was the bone of a man's leg, Rex!"

You could imagine the dog's answer. It would be something like this: "I'm not a man-eater, Tom. My duty is to chase thieves, and grab them, but not to kill them. Unless I had my orders to kill them. Then I suppose I'd have to."

The great teeth crunched and gritted on the bone: with patient paws Rex turned it over and over and clawed it, as though he was afraid of missing some tiny scrap of flesh that might still adhere to it.

"I think that bone's pretty well worn out, Rex. You might call it a day, and go to bed."

Perhaps Rex would have liked to reply: "I'm having such fun. It makes my teeth strong to do this. I think I ought to have more meat in my diet. I have work to do. Something tells me something's going to happen pretty soon—nobody can tell just when—that'll take all the nerve and strength and wits I've got. And I want to be ready for It, whatever It is, whenever It comes."

Mr. Mason came out of the house and called, "Tom!"

"Yes, Father."

"What do you think happened when I put that meat in the rat trap?"

"Did the rat eat it?"

"Yes. He nibbled at it. I watched him. Pretty soon he stopped eating, had a fit, and died. It must have been very strong poison to do that. Strychnine, I guess."

It was lamp-lighting time, and when they called to Rex to come in, he was like a child reluctant to leave a game. Looking up from the polished bone between his paws, it was as though he asked: "Can I bring it into the house with me?"

"You'd better leave it there, old boy. You'll find it there in the morning. I don't think anybody else will want it now.—Oh, Father!" The boy's face was very serious. "Just suppose it had been Rex, instead of that rat!"

Mr. Mason's face was hard as granite. Tom had never seen such a look in that usually kind and gentle countenance. "That settles it. We must get a posse as soon as we can and go after those fellows."

But the next day when he called up several of his neighbors on the telephone, though they praised the plan, and said somebody certainly ought to get the Sheriff to go after the thieves, they were too busy to promise they would let themselves be sworn in as deputy sheriffs. They had potatoes or tomatoes or grain or hay to look after, and so far the epidemic of robbery hadn't broken out in their section. Or else they said that the blame might belong to a band of gypsies that had recently passed through. Somebody had seen the gypsy king with a colt that belonged to Henry Martin. You had to be mighty sure you were right before you planned war on an armed gang of desperadoes. Better let the law take its course....

Then, late one evening, just after they had gone in the house and turned on the electric light, Tom heard a sound on the verandah as of stealthy footsteps.

"Listen, Father!"

There was silence, except that a long way off, at Simpson's Pond, they heard the lonely music of a whippoorwill.

Father had been reading aloud from "Huckleberry Finn." Rex was lying at his feet. When Tom spoke, Rex raised his head and his nostrils quivered as he scented what they could not see.

"Look!" Mrs. Mason screamed. "There! At the window! I saw a face!"

Whoever it was, he had vanished instantly.

The window was open because of the warm night, and mosquito-netting filled the frame, for the new screens that had been ordered were delayed.

There was a streak of police-dog across the carpet—no time lost in growl or bark—and at a bound Rex cleared the sill, taking most of the mosquito-netting with him. The man, instead of running, had crouched under the window-sill. As Rex leapt over him, he rose, and when the dog stopped and whirled about and came at him furiously he discharged his revolver in the animal's face.

Rex, with an almost human groan, rolled over and lay still.

The brigand ran like a deer across the door-yard, leapt into a car that was waiting in the road for him, and was off like one of August's shooting-stars.

They rushed out on the verandah and knelt by the dog.

"He missed!" cried Mr. Mason, exultantly. "Missed, at that distance! Rex is only stunned. Go get some water."

In ten minutes Rex was on his feet again, shaken and staggering, indignant but unhurt.

"Thank Heaven he isn't blinded!" Mrs. Mason ejaculated. "It's a miracle his head wasn't blown off.—Who's that coming?"

It was Mrs. Austin, weeping uncontrollably, and in her agony of mind hardly able to make herself intelligible.

"They've kidnapped—my—baby!" she wailed. "What shall I do? What shall I do? I must go after them. I must—I must go to-night."

But happily it turned out to be a false alarm.

The baby, with a bandage wound about her face, was found lying under the hawthorn hedge close to the place where the robber got into the car.

The child was wrapped in a tattered horse-blanket, and her wrists and ankles were bound with rope.

When Mrs. Austin was able to talk of it reasonably, she told them that she had been sitting alone on the piazza. All doors and windows of the house were open, the child was upstairs, and the mother must have fallen asleep. How the little girl was spirited from the house she did not know: evidently the car had not been brought near, for fear of the noise, and the baby must have been carried toward the fields and laid under the hedge.

Then, in the hurry to get away, the would-be kidnapper had left the child behind.

Three days later little Susy toddled out of the house while her mother dozed in the hammock on the porch. Poor Mrs. Austin was a frail, nervous little woman, and had to spend much time in bed with one illness after another.

Susy loved to dig in the muddy ditch at the side of the road, where there was a rill that flowed from a watering-trough and she could build a dam with stones and grass to stuff the crevices.

It was a lovely blue sunny day, and she hummed a little song as she went about her work. Rex, her great friend, watched her gravely. He seemed a little troubled. No doubt he was thinking: "That's all very well, little missy. You're having a fine time. But how about your mother on the porch? She thinks you'd better stick pretty close to her for a while. You know what happened the other evening. That man wanted to take you away, and he nearly got you."

Then a brown rabbit ran across the road, his white tail bobbing up and down.

Like a shot Rex was after him. But the rabbit was no foolish little fellow, ignorant of the world. He was a sage veteran.

He darted this way and that in the underbrush. He got in between stones where Rex dug frantically to dislodge him and sprinted through clearings where trees had fallen in a tangle and he could run under but Rex had to climb over. And then, just as Rex thought he had caught up and was about to snap his jaws on a good meal, the rabbit vanished.

Then Rex saw a hole in red clay, with dead leaves about it, under a log. It would take half a day to dig him out.

"I must go back to Susy," Rex probably said to himself disgustedly. It was not a common experience with him to miss what he went after. But lately it had happened to him twice. The man who shot at him and nearly stole the baby got away and now the rabbit had escaped....

He jogged back to the roadway, finding the going harder among the rocks and the windfalls, now that the excitement of the chase was over.

But what was happening there in the road? A rickety old motor-car, a runabout, had stopped just where Susy was building the dam.

A man got out. Susy was standing close to the watering-trough, and the water running in and out made a noise that kept her from hearing his stealthy approach. Her back was turned, and before she could cry out he had thrown a burlap sack over her head and was tying a rope across her mouth.

"Not this time!" said Rex, if his actions could speak for him,—and indeed they often seemed to speak louder than human words.

He forgot his disappointment about the rabbit—he saw only Susy, and thought of nothing but saving her.

The car had a hundred yards the start of him, but he raced after it with might and main.

The man looked round. He had laid the child on the seat, and the car bounced so violently as he urged it forward at top speed that it wouldn't have been surprising had the sack fallen out.

It was like the old picture of the sleigh in Russia, with a wolf racing and raging after, and the traveller about to save himself by throwing a baby to the famished animal.

But Rex was not chasing horses—he had to outrun a motor-car. Luckily for him, it was an old and feeble machine. But it was still good for a speed greater than that of any horse against which Rex's wolf-brother in Russia had to run.

Could he do it, he wondered?

Since he got that blast of fire in his face from the revolver three days before he had been conscious of a swimming head and drumming ears and shaky legs. The rabbit had made him forget these things, and had helped him to recover his wind and his speed. That was fun. This was dead earnest. He was not sure that his strength would hold out much further.