* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Court and the London Theatres during the Reign of Elizabeth

Date of first publication: 1913

Author: Thornton Shirley Graves (1883-1925)

Date first posted: April 5 2013

Date last updated: April 5 2013

Faded Page eBook #20130407

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Ronald Tolkien & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

(This file was produced from scans of public domain material produced by Microsoft for their Live Search Books site.)

Page 25, line 24. For Milton read Melton.

Page 32, line 2. For “early in the nineteenth century” read “late in the eighteenth century”..

Page 34, line 28. For Howe read Howes.

Page 36, line 5. For Howe’s read Howes’.

Page 39, line 22. For “four” read “all”.

Page 43, lines 4 and 17. For Howe read Howes.

Page 67, line 7. For George-a Greene read George-a-Greene.

Page 69, line 19. For Cross read Crosse.

Page 85, line 18. For Burgley read Burghley.

Most of the conclusions in the following monograph were reached in the fall of 1910 and presented a little later before the seminar in Elizabethan Literature conducted by Professor F. I. Carpenter. A short time afterwards Neuendorff’s Die englische Volksbühne im Zeitalter Shakespeares became accessible, thus necessitating the rewriting of the first part of my study. The latter part remains substantially as it was originally written. Since the dissertation was accepted by the Department of English at the University of Chicago, Professor Feuillerat has printed for the German Shakespeare Society the documents proving the existence of an earlier Blackfriars, Professor Wallace has brought out his Evolution of the English Drama, and Mr. W. J. Lawrence has published his two volumes of essays, The Elizabethan Playhouse and Other Studies. Very recently Mrs. C. C. Stopes’s James Burbage has appeared. I regret that I have not been able to make use of the recent works of these scholars; yet I do not see that the theory as presented in the following pages is seriously affected by newly discovered facts.

To the earlier published works of Professor Feuillerat and Mr. W. J. Lawrence, my indebtedness is large, as the foot-notes below reveal. I wish, too, to acknowledge my indebtedness to my friend G. F. Reynolds, not only for the help which his articles have afforded me, but also for suggestions privately made. It is a pleasure to express here my thanks to Professors C. A. Baskervill, A. H. Tolman, and R. M. Lovett, who kindly read my dissertation when it was in manuscript. To Professor Carpenter I am obliged for suggesting to me the present study and advising that I pursue it at a time when I would have turned to something else. And finally, to Professor J. M. Manly I am especially indebted for his criticism and encouragement, and for the privilege of examining, before they were made accessible in Murray’s English Dramatic Companies, a large body of the extant records of theatrical performances in the provinces.

Durham, N.C.

November 29, 1913.

Years ago George Steevens in his endeavor to prove the use of scenes in Elizabethan theatres ended his argument with the following words:

“To conclude, the richest and most expensive scenes had been introduced to dress up those spurious children of the Muse called Masques: nor have we sufficient reason for believing that Tragedy, her legitimate offspring, continued to be exposed in rags, while appendages more suitable to her dignity were known to be within the reach of our ancient Managers. Shakespeare, Burbage, and Condell must have had frequent opportunities of being acquainted with the mode in which both Masques, Tragedies, and Comedies were represented in the inns of court, the halls of noblemen, and in the palace itself.”[1]

This, it seems to me, is a thoroughly sane point of view from which to approach the Elizabethan stage. Owing, however, to Steevens’s unsuccessful encounter with Malone on the subject of modern scenes, and to certain unduly emphasized statements by such personages as Ben Jonson and Sir Philip Sidney, scholarship has until recently insisted on considering the Elizabethan regular and court stages as things apart and unrelated, the one arising from an humble inn-yard original and contenting itself with pleasing an uncultivated inn-yard taste, the other springing from a more aristocratic prototype and holding itself rigidly aloof from its less pretentious contemporary.[2]

And even now when the blanket and bare platform which once satisfied students as a background for Shakespeare’s poetry have been generally discarded, there is still a tendency on the part of some to exclude court influence altogether, or to admit it only late in the reign of James I, implying that the regular theatres during the Elizabethan era proper progressed but little in equipment and efficiency of presentation beyond the pageant-wagons which two centuries earlier had rolled about the streets of England.

But an explanation of the equipment and practices of the[Pg 2] Shakesperian Theatre is not to be sought for in mystery plays. Nor are they to be accounted for by accepting satire at its face value while ignoring or explaining away statements of a contrary nature; or by maintaining that the early London playhouse was exclusively popular in origin and method, a folk institution, as it were, where noise and buffoonery, sword-play and oratory, were the only essentials for a successful two hours’ traffic of the stage.

Such a view is not only eminently unfair to the professional actors and the Elizabethan audiences, but is out of keeping with the whole spirit of the age. It fails to take into proper consideration the prominence in theatrical matters of a court which from the time of Henry VIII had been accustomed to entertainments as elaborate and impressive as sixteenth century England could devise; and it neglects to recognize the various opportunities for court influence upon the London stages long before the reign of James, the numerous incentives for such an influence, the open-mindedness of Elizabethans, and the business sense possessed by such managers as Burbage and Henslowe.

The object of this study, therefore, is to approach the London theatres from an entirely different point of view, the court, and to point out the probability of influence prior to 1603. Features of similarity and possible court influence are, I believe, to be found in the general stage structure of the earlier theatres, in certain principles and practices of staging, in various theatrical devices employed for realistic and spectacular effects, and in the general nature of the properties and costumes employed in public performances during the reign of Elizabeth.

Such a study, like all studies of the Elizabethan stage, is beset with difficulties and uncertainties. In most respects conclusive results are as yet impossible; theories are incapable of demonstration to the satisfaction of all. Students of the stage are at most dealing with probabilities. Owing, however, to the labors especially of Feuillerat and Reyher, we are able to stand on comparatively firm ground in our discussion of the methods employed at court performances; and at court, it must always be remembered, Shakespeare and his fellows acted dramas which were also presented at the public theatres. It is hoped, then, that a study from this point of view, unsatisfactory as it necessarily is, may contribute toward the[Pg 3] solution of certain problems which at present confront the students of the Elizabethan theatre.

In undertaking such a study, it has seemed advisable to divide the discussion into four parts. The first is devoted to a discussion of the structural elements of the Elizabethan theatre with especial reference to the recent theory advanced by Neuendorff in so far as it conflicts with the theory of the present writer; the second concerns itself with the inn-yard and its relationship to the first London playhouses; the third attempts to establish the probability of court influence in general stage structure at the early public theatres; and the fourth deals in a more general way with the indications of court influence in the methods of presenting dramas at the regular playhouses during the reign of Elizabeth.

Notwithstanding the great diversity of opinion regarding certain features and practices of the Elizabethan playhouse, there is now general agreement as to the existence of a balcony or upper stage in all the theatres of Shakespeare’s time. It is generally believed, too, that beneath this upper stage was suspended in most of the theatres of the period a curtain flanked on each side by a door opening upon the outer stage. Behind these doors, it is thought, were the property and dressing rooms, the whole back portion of the stage being often called the “tyring-house”.

This, I believe, was in its essential elements the regular form of the Elizabethan stage from the time of its construction in 1576. Perhaps when managers and actors realized more and more the possibilities of the “place behind the stage” or “alcove” or the “canopy”,[3] they enlarged it; perhaps the oblique doors are a later touch; but that the general plan of two side doors with a middle entrance through rear stage and curtains was in operation from the beginning, and that it was suggested by the Court stage or stages seems highly probable.

Of course this form of stage cannot be actually proved for the Theatre and Curtain. It has hardly been proved at the Rose, although we know with respect to this particular playhouse that it had a balcony and a curtain, three entrances, and behind the stage a place which was presumably larger than the space concealed by a single door. The existence of a similar type of stage can, I believe, be established as probable at the two earlier theatres. To remove certain possible objections to such an idea is the chief object of the first part of this study. The probable court origin of such a type of stage will receive treatment in a later part.

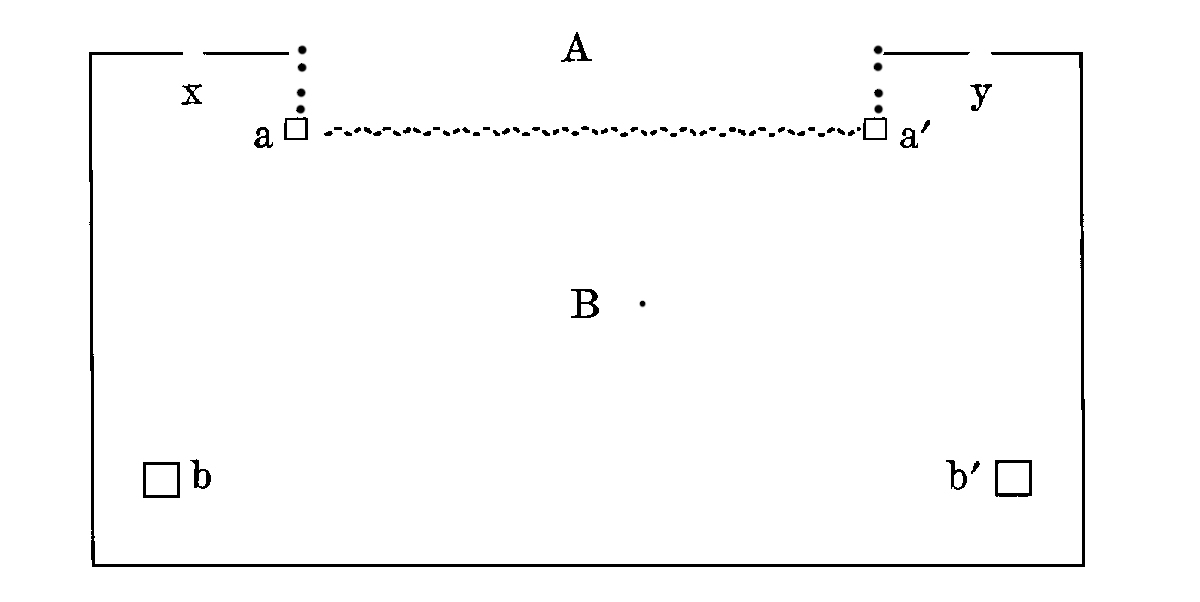

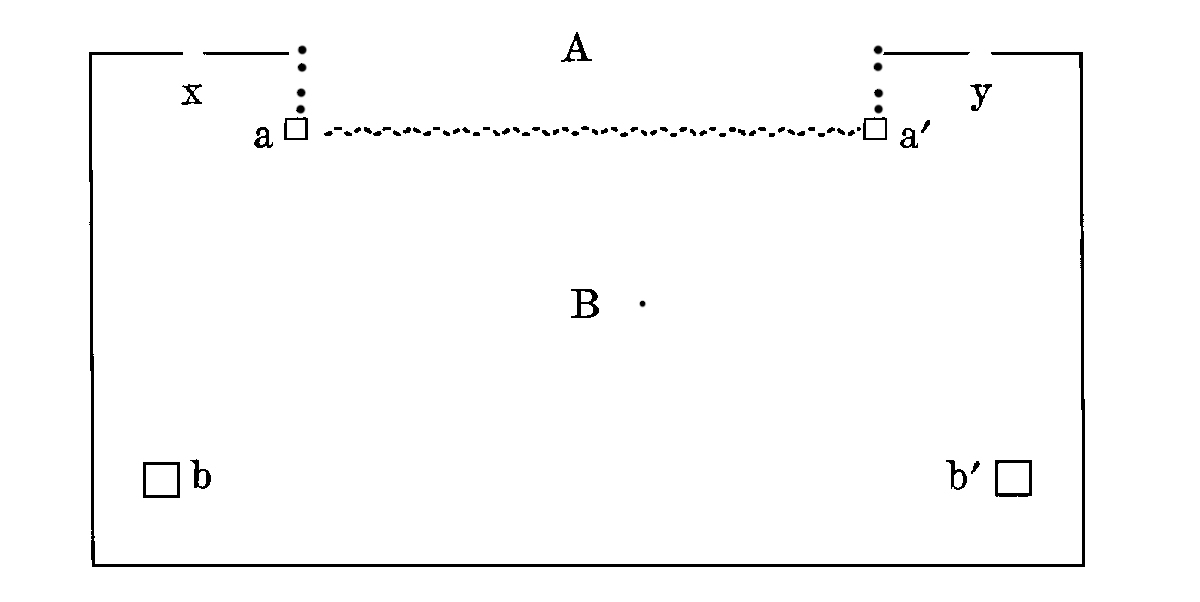

As any such theory is in certain respects radically opposed to that offered by Neuendorff in his recent book Die englische Volksbühne, it is fitting at this point to give a criticism of those features of his study which conflict with the probability of such a theory. Basing his conclusions on what he calls direct and indirect sources[Pg 5] of evidence, he finds three main types of stage in use during the period 1576-1642. The first is a stage without a curtain and with an undivided lower stage. This, he thinks, is the most primitive type, the first experiment in stage building. It is represented in the Red Bull and perhaps in the Roxana[4] pictures. The second type is a lower stage lying entirely before the balcony, divided into two parts by pillars, and approached by two (or three) doors at the rear. The Swan picture is representative here. This, I take it, is the second experiment. The third type, or fully developed stage, is that shown in the Messalina picture, the “canopy stage”, as I shall term it; that is, a structure where the rear stage consists of a recess (A in the figure below) separated from the front stage (B) by a curtain (aa´) and situated beneath a balcony, or upper stage, projected a few feet beyond the line of the side entrances (x and y) and supported at the front by two pillars (a and a´), which pillars are not to be confused with the larger ones (b and b´) supporting the shadow over the front stage.

Along with these various experiments in stage building he traces a more or less regular development in the method of staging. The steps in this development should perhaps be given in his own words: “Blicken wir zunächst zurück: wir hatten gesehen, dass ein einheitliches Bild von der englischen Bühne nicht zu erhalten war. Zur Shakespeare-Zeit stehen wir noch in den Anfängen des Theaterwesens, denn greifbare Versuche konnten erst mit dem Bau[Pg 6] fester Theater gemacht werden. Und so wurde zweifellos experimentiert—eine Reihe von Bühnenformen liess sich nachweisen, Bühnenformen, die eine Entwicklung darstellen.

“Hand in Hand mit dem Fortschritt im Bau der Bühnen ging eine Entwicklung in der Behandlung des Ortes. Diese Entwicklung vollzog sich in drei Stufen, die zwar durchaus nicht streng zu scheiden sind, aber in dem Sinn Geltung haben, dass die erste die am frühesten verschwindende ist (abgesehen von wenigen Resten), die zweite sich länger neben der dritten hält, die dritte aber die herrschende wird. Die Einteilung in Stufen ist also nicht nach dem Auftreten, sondern nach dem Verschwinden, oder doch wenigstens nach dem Zurückgehen, vorgenommen.

“Die erste Stufe ist darnach die gleichzeitige Darstellung mehrerer Orte auf der Bühne. Die zweite ist die Fiktion mehrerer Orte nacheinander innerhalb derselben Szene. Die dritte Stufe ist erst die einer realen Ortsbehandlung: entweder Verlegung verschiedener Örtlichkeiten auf verschiedene Bühnenfelder oder aber Beschränkung einer Szenenhandlung auf einen Ort” (pp. 202-3).

Now let us pause to determine the significance of Neuendorff’s theory in its relationship to the theory outlined above. Neuendorff is doubtless right in supposing that there was a progress in the method of staging. My discussion of the nature and cause of this development will be found in a later section. His fundamental error, it seems to me, lies in his contention that this development went hand in hand with various experiments in stage construction. Indispensable for any such theory is, not only the construction of numerous radically different types of stage between the years 1576 and 1642, but also the wide-spread existence of a very primitive method of staging on an equally primitive form of stage. To secure these necessary primitive conditions, he sometimes resorts to late plays, notably Suckling’s Aglaura, for evidence; and he uses a very late picture, that of the Red Bull, to illustrate his most primitive type of stage, in spite of the fact that this picture is of little or no value in such a discussion.[5] He has great faith in the accuracy of the DeWitt drawing of the Swan, and hence uses it as his chief evidence in arguing for the prevalence of the vorhanglose[Pg 7] Bühne. He admits curtains at the Rose and thinks that it belongs to the Messalina or fully developed type of stage. He admits this, let me repeat, yet he does not offer a satisfactory reason why the Swan, as represented in the drawing, has neither curtains nor any place for them in spite of their earlier existence at the Rose,[6] and the significance of such conveniences in staging; thus advancing what seems to me, I must confess, the inconceivable idea that even after the curtained stage, the fully developed or “canopy stage”, was in existence, the vorhanglose Bühne continued to be constructed and used. He throws doubt on certain evidence pointing to curtains at the Blackfriars; he is skeptical regarding the existence of stage curtains at the Globe and Fortune; and on page 29 he writes that these two theatres, together with the Swan and Hope, apparently belong to the same general type of stage. He says further (p. 43): “Schon jetzt aber erkennen wir, dass die vorhanglose Bühne—drei von den überlieferten Bildern stellen eine solche dar—eine viel grössere Verbreitung in der Shakespeare-Zeit hatte, als wir im allgemeinen annehmen”. On this wide-spread curtainless stage, he asserts, the functions and effects of curtains were secured by the use of canopies, curtained beds, thrones and stage doors.

Neuendorff’s theory, then, is built up on the assumption that the vorhanglose Bühne was a common institution in sixteenth century England. And it is just here that his theory conflicts vitally with the one set forth in the present study; for if it can be established that the vorhanglose Bühne, a more primitive form of stage than that at the Rose, was a wide-spread type in the days of Shakespeare, then there are good a priori reasons for believing that the two earliest playhouses—the Theatre and the Curtain—conformed to this type rather than to that of the Rose. The real question at issue therefore is, Was the vorhanglose Bühne with its various modifications a common form of stage during the Elizabethan period?

Now personally I do not believe that there was ever such a thing as a vorhanglose Bühne among the regular London theatres from 1576 to 1642. That many plays could be, and were, staged without[Pg 8] the use of a curtain is undoubtedly true, but this has little or nothing to do with the point under discussion. That rear stage scenes are comparatively rare is also quite true—it is only natural that they should be so—and that doors were sometimes used to represent shops or even studies may be admitted without affecting the question at issue.

In favor of the general use of stage curtains may be urged the theatrical instinct for such conveniences, the common sense of Elizabethan theatrical people, and the existence of curtains in theatrical entertainments from the earliest times. They may not have been common on the pageant wagons of the cyclic mystery plays, but it is certain that they were used in stationary performances in England[7] as well as in France.[8]

At court entertainments curtains were used at least as early as the time of Henry VIII. In 1511, for instance, a curtain suddenly falling at one end of the hall revealed a gorgeous pageant.[9] In 1518, “immediately after a curtain had been lowered, a handsome triumphal car appeared, with a castle and a rock, all green within and gilded. Within the rock was a cave all gilded, the gates being of wood with silk curtains, like a recess; and within the cave were nine very handsome damsels with wax candles in their hands, all dressed alike, looking through the veil, like radiant goddesses”.[10] At Greenwich, in 1527, there fell at the extremity of the hall “a painted canvas [curtain], from an aperture in which was seen a most verdant cave”.[11] In the same year at York Place a curtain fell, revealing Venus surrounded by six maidens seated on a sort of scaffold.[12] Gibson’s accounts for this year contain “ironwork to hang the curtains with, 2s.”, “4 doz. curtain rings, 4d.”, “a whole piece of cord to draw the curtains, 14d.”[13] Not very clear is the direction in Godly Queen Hester (l. 140), which Greg and Bang think was acted at Court between 1525 and 1529: “Here the Kynge[Pg 9] entry the travers & Aman goeth out”. Even more vague is the rope used for the “travas” in the hall at Greenwich in 1511.[14]

Curtains at court during the reign of Elizabeth were regular features at performances. The only question is whether front curtains were employed.[15] Universities and the Inns of Court recognized the value of curtains. In Legge’s Ricardus Tertius, acted at Cambridge in 1579, occurs the direction: “a curtaine being drawne, let the queene appeare in ye sanctuary, her 5 daughters and maydes about her, sittinge on packs, fardells, chests, cofers. The queene sitting on ye ground with fardells about her”.[16] At Gray’s Inn on Jan. 3, 1594, “at the side of the hall, behind a curtain, was erected an altar to the goddess of amity”, etc. At the conclusion[Pg 10] of the performance, “with sweet and pleasant melody, the curtain was drawn as it was at first”.[17]

Curtains were used on the pageants drawn into the halls of the time. One case in the reign of Henry VIII has already been cited. And the “Rocke, or hill ffor the ix musses to Singe uppone with a vayne of Sarsnett Drawen upp and downe before them”, mentioned in 1564 in connection with a “maske of hunters” and “a play maid by Sir Percyval hartes Sones”,[18] was perhaps a movable structure. Whether curtains were used in the outdoor city pageants of the time, I do not know, but it is certain that at no late time they were used for the purposes of surprise and symbolism. When James I entered London, one of the devices was got up by the Dutch. Above the “Heart of the Trophee” was a “spacious square roome, left open, silke curtaines drawne before it: which upon the approch of his Majestie being put by, Seventeen yong Damsels, all of them sumptuously adorned after their countrey fashion, sate as it were in so many chaires of state”.[19] A curtain painted like a cloud was similarly used in Jonson’s device at Fenchurch on the same occasion.[20]

Curtains, whatever may have been their function, are not unheard of in public performances as early as cir. 1530. This is brought out in the Walton-Rastell lawsuit,[21] where among the playing parcels confessed by Walton are “Two curtains, of green and yellow sarcenet”. And curtains of green and yellow sarcenet, it may be noted, remind one of the striped curtain which, according to George Steevens, adorned the sign of the Curtain theatre.[22]

Such references as these, to be sure, do not prove an “alcove” at the Theatre or Curtain, but they do argue, it seems to me, against the supposition that experienced theatrical people when they undertook to construct permanent theatres would deliberately erect stages on which such theatrical commonplaces and conveniences were impossible or practically useless, platforms on which the effects ordinarily secured by curtains were more or less acceptably secured by the use of stage doors, canopies, curtained thrones and[Pg 11] beds. That such makeshifts were resorted to on improvised stages or in provincial tours I am willing to admit, but that they were ever used in the regular London theatres because a stage curtain was lacking, I must as yet refuse to believe. Neuendorff himself was acquainted with the early use of curtains in English theatricals at court and elsewhere, but he does not give such a fact the importance that it deserves. The proof of a curtain at every London theatre for every year of its existence is probably impossible, but such is entirely unnecessary to establish beyond all reasonable doubt the general employment of a theatrical commonplace.

That canopies above beds, canopies above thrones, canopies to be borne above actors were all used in the London theatres is certainly true, but they were not used as makeshifts for stage curtains.

As a result of his faith in the DeWitt sketch, Neuendorff goes to unnecessary trouble in explaining how Elizabethans overcame the difficulties necessitated by a vorhanglose Bühne. The stage direction in Eastward Hoe, I, 1, “At the middle door enter Golding, discovering a goldsmith’s shop and walking short turns before it”, certainly seems to mean, as Reynolds pointed out,[23] that Golding comes in at the door at the back of the rear stage and draws the stage curtain. Neuendorff,[24] however, asserts that the shop could be discovered by opening a stage door. Of course this is true, provided the doors on the Elizabethan stage were very large and swung out upon the stage instead of swinging back into the tiring-house, and thus interfering with properties on the rear stage, but why suppose any such process, when the play was presented at Blackfriars where the existence of curtains can be abundantly shown?

Again, of the direction in Henry VIII, II, 2, “Exit Lord Chamberlain; and the King draws the curtain and sits reading pensively”, Neuendorff[25] says: “Wie können wir sonst erklären, dass der König selbst den Vorhang zieht, als durch die einfache Annahme, er sitzt auf dem state, zunächst von dem geschlossenen Vorhang dieses Thronsitzes verborgen, wie das in anderen Fällen sicher[Pg 12] belegt ist”. There is no difficulty here. The direction may well mean that the king drew the curtains [before the alcove] and then sat reading pensively. Or he could while sitting have drawn the stage curtains practically as easily as the curtain before a throne. The operation is no more complex than are others called for in stage directions. Bobadilla, for example, in Every Man in his Humor (l. 420), “discovers himself on a bench”; and Laverdure in What You Will, II, i, “draws the curtains, sitting on his bed, apparalling himself; his trunke of apparaile standing by him”.

While canopies were used, still there is a distinction to be made between a canopy and the canopy of Percy’s Faery Pastorall and Marston’s Sophinisba. What could be a more appropriate term for the rear stage than “Canopie”? The author of the stage direction preceding Greene’s Alphonsus, IV, i, was content to call it the “place behind the stage”. Not so with Percy; hence he asserts that over this place behind the stage, the “Canopie”, was to be written “Faery Chappell”. The fact that he was thinking of a permanent part of the stage and not an ordinary canopy is revealed by considering the word “Canopie” in connection with what precedes: “Highest, aloft, and on the Top of the Musick Tree the Title The Faery Pastorall, Beneath him pind on Post of the Tree The Scene Eluida Forrest. Lowest of all ouer the Canopie ΝΑΠΑΙΤΒΟΔΑΙΟΝ or Faery Chappell”. The “Musick Tree” and “Post of the Tree”, then, were directly above the “Canopie”.

There is only one circumstance which in any way implies that a separate structure was employed for the chapel. On page 149 occurs the direction: “Mercury entring by the Midde doore wafted them back by the doore they came in”. On page 165 we find the direction: “They enterd at severall doores Learchus at the Midde doore”.

Says Neuendorff in his endeavor to prove a curtainless stage (p. 75): “Dass hier nun sicherlich nicht mit der Hinterbühne zu rechnen ist, zeigt III, 5 und IV, 8, in denen Personen durch die Midde doore auftreten. Diese Tür hätte auf einer Bühne mit Vorhang nur zu der Hinterbühne führen können—wo wäre sonst Platz für sie?—, wer also durch die Mitteltür hereintrat, wäre von der Hinterbühne gekommen, d. h. aus der Kapelle. So kann der als Faery Chappel festgelegte Raum nicht auf der Hinterbühne, deren[Pg 13] Existenz in diesem Falle damit überhaupt verneint werden muss, gelegen haben”.

I fail to see the force of any such argument. In the first place, there is no reason why the characters should not have entered through the chapel. In the second place, the mention of a “midde doore” instead of midst, especially by so loose a thinker as the gentleman who wrote at Wolves Hill as his Parnassus, does not disprove a curtain before the rear stage. Plays, for example, published at approximately the same date and written for the same theatre call for a middle door and a curtain.[26] In the third place, there is some evidence that this very drama calls for a curtain before the “Canopie”, or rear stage, in which characters and a banquet are shut later in the play. The scene is a forest. Yet arras are referred to on page 179 where we find the direction: “He tooke from behind the Arras a Peck of goodly Acornes pilld”. “Arras” used in the sense of curtains is frequent; and it is rather difficult to see why arras should be referred to in a play calling for three doors and a forest setting, unless the author had in mind the regular curtain (arras) before the rear stage.

This being true, probably the arras from behind which the goodly acorns were taken were closed when Mercury and Learchus entered by the rear door, and as a result they were not conceived as entering from the chapel. Or perhaps the arras were open; hence the author wrote that the characters entered by the “midde doore” instead of “midst”. Or it is possible that Elizabethans, like the dramatists of the Restoration, occasionally referred to the opening of the rear stage itself as a door,[27] although it was larger[Pg 14] than the side doors. Was Thomas Holyoke, for example, thinking of the Roman theatre when he defined scena in his Latin dictionary (1677) as “the middle door of the stage”? As we shall see later, scene was apparently used at times before 1660 to denote the rear stage itself. Cases in Restoration dramas where door is used to refer to the scene or curtain are rather frequent.

Another thing should be noted in connection with Percy’s “Canopie”. Near the end of the play we find the words: “Here they shutt both [i. e., Orion and Hysiphyle] into the Canopie Fane or Trophey together with the banquet” (p. 187). We can understand how a person of Percy’s temper might call a chapel a temple or fane, but not even Percy’s originality would seem to justify the use of the word “Trophey” as a synonym for “Faery Chappell”. There is only one possible motive for such procedure. On page 100 Hysiphyle says to Orion:

And in the margin are written the words: “She hurld her ghirlond Imperiall up to Front of the Fane or Chappell”. It may be urged that by some extraordinary mental process Percy eighty-nine pages further on had these lines in mind when he wrote the word “Trophey”. This, however, would hardly explain why he had the characters “shutt in the Trophey”, since on page 183 the “Imperiall Ghirlond” had been removed from the front of the chapel and placed on the head of Orion.

An explanation of what Percy really had in mind when he wrote the direction may be ventured. He was trying to describe the rear of his stage, that is, a large opening surmounted by a balcony and flanked by two smaller openings. The “trophees” or triumphal arches erected at the coronation of the sovereigns or on similar occasions admirably fit such conditions. At Elizabeth’s coronation, for example, a pageant or arch extended from one side of the street to the other. “And in the same pageant was devised three gates all open, and over the middle part thereof was erected one chaire or seate roiall”, etc. Across the front of the pageant was written[Pg 15] its title.[28] This was at Cornhill. “Against Soper lane was extended from the one side of the street to the other, a pageant which had three gates all open; over the middlemost whereof were erected three severall stages, whereon sat eight children, as hereafter followeth”, etc.[29] The queen and her train passed through the middle and largest gate. When James I entered London in 1603, at Cheapside stood a “stately entraunce into which was a faire gate, in height 18 foote, in breadth 12; the thicknesse of the passage under it being 24. Two posternes stoode wide open on the two sides, either of them being 4 foote wide, and 8 foote high”.[30] The Dutch pageant on the same occasion[31] was similar, the central gate measuring 12 × 18 ft. with “two lesser posternes ... for common feete, cut out and open’d on the sides of the other”. If it be objected that such structures were not called “Trophees”, then I refer the reader to Dekker’s account of the “Italian trophee” erected at James I’s entrance,[32] or to his words regarding the Dutch pageant referred to above: “Above which (being the heart of the trophee) was a spacious square roome, left open, silke curtaines drawne before it”.[33]

Perhaps “Fane” was also used as a descriptive word to apply to the background of the stage. Percy’s position and the stage direction above imply that he knew Greek. Possibly the skene of the Attic theatre, usually penetrated by three openings and frequently representing a fane or temple in Greek tragedy, flashed into his head, but the more suggestive “trophey” was considered a necessary addition for clearness.

Other descriptive words used in connection with the rear stage are perhaps extant. In 1598 Florio writing for Englishmen defined scena in his dictionary as “a skaffold, a pavillion, or forepart of a theatre where players make them readie, being trimmed with hangings, out of which they enter upon the stage”. Florio[Pg 16] probably had the English theatre in mind,[34] the canopy of Percy and Marston. Years before, Palsgrave had used the word “scene” in its old sense of dressing-room, or booth, when in the Prologue to his Acolastus he wrote (cf. N. E. D. under “scenish”): “The settying forth or trymming of our scenes, that is to saye, our places appoynted for our players to come forth of”. About 1520 the author of The englysshe Mancyne apon the foure cardynale vertues spoke of “a disgyser yt goeth into a secret corner callyd a sene of the pleyinge place to chaunge his rayment”.[35] Perhaps some idea of what Florio meant by hangings at the “forepart” of the stage is brought out by Heywood in his Apology for Actors (p. 18), where he has Melpomene to say that the Golden Age was a time

Two late cases of the word “scene” in much the same sense that Florio seems to have used it as applying to the part of the tiring-house behind the curtains are probably to be found. Dekker’s If This Be Not a Good Play (pub. 1612, as lately acted at the Red Bull) has the direction, “Narcisso stepping in before in the Scene, enters here”. This direction clearly means that Narcisso after having been on the rear stage (“scene”) for some time passes to (“enters”) the front stage. Brome’s Joviall Crew (pub. 1641 as acted at the Cockpit) contains the direction, “He opens the scene; the Beggars are discovered in their postures”. Scene in the later sense of curtain or partition was probably pretty common when this play was presented, but in view of what has preceded, it is possible to interpret the words to mean that the curtains before the “scene” (rear stage) were drawn.

Percy’s “Canopie” and Florio’s “pavillion” are both good terms to apply to a recess located beneath a roof or balcony and shut off from the view of the audience by arras or curtains. This being true, there is always the possibility that when stage directions refer to a canopy, the author has in mind the space beneath[Pg 17] the balcony—an ordinary feature of playhouses—and not a separate stage property. And Florio’s “pavillion”, apparently used of stages in general in 1598, as well as Percy’s “canopie”, cannot be well applied, it should be noted, to the mimorum aedes of the Swan sketch.

Not only were canopies employed in the London theatres, but it is pretty certain that separate structures for shops, etc. were also used.[36] Even their use does not show, however, that a regular stage curtain was lacking. The rear stage was primarily designed to take the place of such structures, thereby keeping down expenses and at the same time allowing adequate presentation. But when it was necessary or desirable to employ a shop or stable in addition to the space behind the curtain, then a shop or stable was employed.

Neuendorff’s argument for a vorhanglose Bühne on the basis of the pictures is not convincing. The Red Bull picture is of no significance in this connection. There is surely no reason for assuming, as Neuendorff does, that the Roxana picture represents a type of stage essentially different from that of the Messalina picture. Evidence has been given elsewhere[37] for believing that the Swan in 1602 was provided with hangings and curtains, a matter that will receive further treatment in the following pages.

Stage directions are of little value in proving or disproving the existence of curtains. As Neuendorff recognizes (p. 59), such stage directions as “enter in a bed”, “a bed thrust forth”, do not in any sense prove the absence of a stage curtain. Many examples of this “crudity” can be found in extremely late plays. As Albright remarks (pp. 140-6), such directions may in many cases at least denote the placing of the bed on the rear stage or the actor’s tendency[Pg 18] to present his action as far forward as possible.[38] The bringing in of banquets proves nothing one way or another. Banquets were regularly “brought in” in actual Elizabethan life.

That definite references to curtains in stage directions are comparatively rare is quite true, but again this does not prove their non-existence. It does not prove that they were not employed even in plays where no reference is made to them. The existence or non-existence of curtains is surly not to be determined on the basis of stage directions. There is, I admit, always a presumption against drawing a curtain unless a direction bids one do so; and I heartily approve of Reynolds’s objection to the regular playing back and forth of curtains called for in Albright’s system of staging. No one, however, will deny, I believe, that numerous cases of the operation of curtains are entirely unnoted either in directions or dialogue. After opening they are frequently closed without any reference to the process. One example will make this clear. At the beginning of II, i, of Lord Cromwell, occur the words, “Cromwell in his study” (i. e. discovered). In III, 2, “Hodge sits in the study” (before the curtains are opened). At line 126 the governor says, “Goe draw the curtaines”, and Hodge is discovered writing a letter. The curtains have surely closed since opening at the beginning of II, i, although there is nothing to that effect in stage-direction or text. Somewhat different are such scenes as IV, 3, of the first part of Edward IV, where at the end of the scene Shore’s wife is sitting in the shop while he is standing by. The scene closes with the words of the wife:

Surely the very domestic Shore did not refuse this invitation. Nor is it probable that the couple left the stage to do their sitting, or sat for a moment and then made an exit.

Of more importance are cases of the curtains opening without stage-directions to that effect. Such vague remarks as “Cromwell in his study”, “Let there be a brazen Head set in the middle of the place behind the stage”, cases where “enter” means[Pg 19] “discover”[39] are in a certain sense examples of this. Reynolds[40] has pointed out that in Pericles “two almost certain discoveries are quite unnoted in the directions”. At the beginning of the second act of The Battle of Alcazar Furies are referred to as sounding in a “cave”, but that is all. In the “Plot” of the play, however, occur the words: “to them [l]ying behind the Curtaines 3 Furies”. The whole situation as well as the phraseology of the direction indicates, as Neuendorff notes (p. 85), that the Furies were discovered in a situation. In A Looking Glass for London, II, i, a similar opening of the curtains occurs. The well-known direction in Bussy D’Ambois, I, 1—“Table, chessboard, and tapers behind the arras”—the words at the conclusion of Tancred and Gismunda, Antonio’s Revenge, V, 2, are other examples. In Endymion and Sir Clyoman and Sir Clymades a curtain was surely used although there is no direction to that effect. Other instances of this sort of thing can be cited, but these are sufficient, it seems to me, to justify an assumption of the operation of curtains when the situation demands it, although that operation may be entirely unnoted in stage directions or dialogue. The problem, of course, is to determine when the situation actually demands the opening or closing of curtains.

Again, Neuendorff is, in my opinion, too skeptical when he expresses a doubt (p. 86) whether the reference in Tatham’s prologue to spectators casting various objects against the curtain at the Bull necessarily refers to the stage curtain. The words in the prologue to Cynthia’s Revels, “Slid the boy takes me for a piece of perspective ... or some silke cortaine, come to hang the stage here”, he similarly regards as indefinite. “Curtain”, he remarks, “ist nicht ein ganz sicherer, eindeutiger Ausdruck, wenn er nicht durch Angabe der Funktion verdeutlicht wird”. To be sure the actual function of the curtain in these two cases is not specified, but there seems to be no objection to giving the natural interpretation to the word in both instances, when curtains are obviously referred to as the ordinary and accustomed part of a theatre. Chamberlain’s allusion to the curtains at the Swan in 1602 is a similar case.

The Careless Shepherdess (pr. 1656)[41] contains the lines:

One determined to prove the accuracy of the Swan sketch might restrict this passage as referring to the late Blackfriars,[42] or imagine Reade peeping through bed curtains. Similarly one could arbitrarily restrict Sir Walter Raleigh’s words to the court stage:

It is virtually certain, however, that Sir Walter was taking his figure from general theatrical conditions. Drummond of Hawthorndon in his Cypress Grove Walks[44] uses the old figure: “Every one cometh there to act his part of this tragi-comedy, called life, which done, the courtaine is drawn, and he removing is said to dy”. “Shut up” in Elizabethan English is a rather general expression, but it is likely that Day had in mind the custom of closing the stage curtains at the conclusion of a play when he has Aspero to end Humour out of Breath with the words:

A general practice, and not the opening or closing of specific curtains in a specific theatre, is in all probability referred to in the Chorus preceding II, 1, of Heywood’s Edward IV (second part):

Such quotations, of course, do not aid much in proving a stage curtain at the Theatre or Globe. They are given to show that when[Pg 21] Elizabethans spoke of curtains in a playhouse, they probably did not have in mind curtains to the upper stage, bed curtains or canopies.

When such things as have been referred to above are considered, together with the evidence for curtains which Neuendorff has collected, there is surely no reason for believing that the vorhanglose Bühne was ever a wide-spread type, that it represents an experiment in stage construction as late as the building of the Swan, or that such a type is to be used in tracing a development in the methods of Elizabethan staging. There is no reason for believing that it existed at all in Elizabethan theatres.

Apparently realizing the common use of curtains in London theatres and carrying out his theory of various experimentations in theatre building, Neuendorff conceives a special form of stage to accommodate such scenes as David and Bethsabe, I, 1, Ford’s Love’s Sacrifice, V, 1, Browne’s Novella, IV, 1. “Man nehme”, he writes, “die Swanbühne, statte sie mit einem Vorhang da aus, wo jetzt die beiden Säulen stehen, und denke man nun die ganze Bühne so weit zurückgerückt, dass der Vorhang dort hängt, wo jetzt das Tiring-house beginnt (dabei ist noch gans von den Türen abgesehen). Möglich ist ja auch, dass für solche Scenen gelegentlich auch die Swanbühne einen Vorhang erhielt” (pp. 92-93).

That such a form of stage existed is at least conceivable. Large curtains were used at court; possibly, front curtains existed in private theatres. It is hardly probable, however, that such a stage was suggested by such a one as that shown in the DeWitt sketch, or that curtains were ever suspended between such pillars as are therein revealed. Nor is a special type of stage necessary to explain the scenes cited above. They are admirably explained by oblique doors or the “canopy” stage. Reynolds’s idea that in such scenes the actors need not actually see those on the inner stage is in itself a satisfactory explanation.[46]

Neuendorff is by no means an alternationist; he would not hang permanently a curtain between the pillars of the Swan type of stage; but the fact that curtains are found at the Swan in 1602 and the great importance which he attaches to the DeWitt sketch necessitate[Pg 22] a discussion of the drawing, especially the nature and location of the front pillars.

Is the DeWitt sketch to be accepted as representing the real nature and position of the shadow and pillars at the Swan? If so, were the curtains mentioned by Chamberlain in 1602 suspended between these pillars? And if so, was this type of stage at all common during the Elizabethan period? These are the questions that now demand our attention.

As we have seen, Neuendorff groups the Fortune, Swan, Globe, and Hope under the same general type of stage; and on page 25 he asserts that, probably after the analogy of the Swan, the “heavens” supported by the pillars covered only a part of the lower stage at the Fortune and Globe. Whether he regards these theatres as being substantially like the Swan, or whether he considers them to be examples of the modified Swan stage mentioned above, I am unable to say. I will say, however, that there is no reason for believing that the DeWitt sketch in the matter of shadow and pillars represents conditions as they existed before or after the building of the Swan. In all probability it does not represent conditions as they existed at the Swan.

In a recent article[47] John Corbin has printed a drawing of the Fortune by George Varian, which represents, it seems to me, more truly the real structure of the shadow or “heavens” than does any drawing that has yet appeared. Under the influence, perhaps, of the DeWitt sketch, the designer of the “typical” Elizabethan stage in Albright’s The Shaksperian Stage represents the shadow as a sort of penthouse covering only a small portion of the projecting stage.[48] In Varian’s drawing, however, the shadow is much larger and higher, and it virtually covers the entire stage. I believe that in some theatres at least the “hut” projected further into the yard than is shown even in Varian’s drawing, and that at the Fortune, Globe, Rose and Hope, perhaps at the Curtain and Theatre, the shed attached to it extended practically to the front edge of the stage. My reasons for this view follow.

In the contract for the Fortune[49] it is specified that there is[Pg 23] to be “a shadowe or cover over the saide Stadge”, which stage is “to extende to the middle of the yarde of the saide howse”. “Over the saide Stadge” and “coveringe of the saide stadge” do not, of course, necessarily mean that the cover is to extend over the entire stage, but that is at least the most natural interpretation to give to the expressions. The same is true of Cotgrave’s definition (French Dictionary, 1611) of Volerie as “a place over a stage which we call the Heaven”. Even the words “shadow” and “cover” suggest that the entire stage, and not a part of it, was to be covered. “Heavens” suggests the same thing, as is illustrated in Cotgrave’s definition of “Dais”, for example, as “a cloth of estate, canopie, or Heaven, that stands over the heads of Princes thrones”. In his preface to the 1591 edition of Astrophel and Stella[50] Nash wrote: “here you shall find a paper stage strewed with pearl, an artificial heaven to overshadow the faire frame”. “Overshadow the fair frame” is perhaps more definite; and Nash, be it remembered, was apparently taking his figure from existing conditions at the Curtain and Theatre.[51] At the Hope the “heavens” were to be constructed “all over the saide stage”; and if the picture of the second Globe is of any service in this connection, it is apparent that in this theatre, too, the “heavens” must have extended “all over” the stage, since the foremost of the two huts surely extends to fully half the distance of the yard.

And why assume that practical Englishmen in building shadows for protection should build that protection over half the stage rather than over all of it? One of the reasons, says Gosson, why Life in The Play of Plays chose Commedies for his companion was “because he may sit out of the raine to viewe the same, when many other pastimes are hindred by wether.” When “commedies,” then, were presented at public houses during rainy weather, why believe that actors in their gorgeous and expensive costumes were either exposed to the weather or else confined to the rear portion of the stage?

There is perhaps another reason for believing that the “hut” projected well forward and that the “cover” attached to it was not a mere penthouse, but a structure parallel to the stage floor and[Pg 24] practically as high as the ceiling of the upper gallery. The term “heavens” doubtless had a double significance. In addition to being a cover or canopy over the stage, it was a “heaven” in the sense that it was fitted up, perhaps very elaborately, to represent the firmament.

The representation of heaven by painted canvas stretched overhead was no new thing in 1576. Among the items, for example, delivered on July 4, 1470, by “Master Canynge” to Nicholas Petters, vicar of St. Mary Redcliffe, was a new sepulchre gilt with gold, and among other things belonging to it, “Heaven, made of timber and stain’d cloth”, and “The Holy Ghosht coming out of Heaven into the supulchre”.[52] The masqueing and banqueting houses of the time were regularly covered with canvas painted like the heavens. The one erected in the courtyard of the Bastille in 1519,[53] for example, was covered with “an awning of blue canvas well waxed and powdered with gilt stars, signs and planets”, while Henry VIII’s “theatre”, erected at Calais in 1520, had a roof of azure-colored canvas “decorated with gold stars and planets of looking glass”.[54]

“Heavens” in pageants are not unknown. At the coronation of Edward VI “towardes Chepe there was a doble scafolde one above the other, which was hanged with cloth of golde and silke, besydes rich arras. There was also devised under the upper scafolde an element or heaven, with the sunn, starrs, and clowdes very naturally. From this clowde there spred abroad another lesser clowde of white sarsenet, frenged with sylke, powdered with sterres and bemes of gold, out of the whiche there descended a Phenyx downe to the nether scafolde.” A “crowne imperiall” was also “brought from heaven above, as by ii angelles”, and placed upon a lion’s head.[55]

At court we hear of wages as early as 1564 for work upon “divers devisses as the heavens & clowds”. In the accounts for 1574-5 “Dubble gyrtes to hange the soon in the Clowde” are[Pg 25] mentioned,[56] while in the same year John Carow is referred to as furnishing “heaven, hell, & the devell & all the devell I should saie but not all”.[57]

Nash in 1591 spoke of an artificial heaven overshadowing his fair stage. Henslowe in 1598 mentions the cloth of the sun and moon; three suns apparently performed in Third Henry VI, II, 1, five moons in The Troublesome Reign; and in the Play of Thos. Stucley “with a sudden thunder-clap the sky is on fire and the blazing star appears”. One is reminded, too, of the “Two pieces of blue linen cloth with lyre in them, 67 yds.” mentioned among the playing parcels of Rastell about 1530.[58] At a much later date Heywood in his Apology for Actors (pp. 34-5), describing Caesar’s theatre in very Elizabethan terms, refers to “the covering of the stage, which wee call the heavens (where upon any occasion their gods descended), were geometrically supported by a giant-like Atlas, whom the poets for his astrology feigne to beare heaven on his shoulders; in which an artificiall sunne and moone, of extraordinary aspect and brightnesse, had their diurnall and nocturnall motions; so had the starres their true and coelestiall course”.

In the same writer’s Brazen Age, V, 2, a hand descends from “heaven” in a cloud and “from the place where Hercules was burnt, brings up a starre, and fixeth it in the firmament”. Brome (Antipodes, 1638) mentions “our planets and our constellations” as ordinary occupants of the property room.[59] Milton in his Astrologaster (1620) speaks of the actors at the Fortune making “artificial lightning in their heavens”. And finally R. M. in his “Character” of a player (1629) has the illuminating passage: “If his action prefigure passion, he raves, rages, and protests much by his painted heavens, and seems in the height of this fit ready to pull Jove out of the garret where perchance he lies leaning on his elbows, or is employed to make squibs and crackers to grace the play” (Morley, Character Writings, pp. 285-86).

Now such properties were obviously intended to be seen by the[Pg 26] entire audience, and not by a part of it, as would have been the case beneath such a shadow as is shown in the DeWitt sketch with its impossible dip. Perhaps it should be mentioned, too, that the gods and thrones that descended from and ascended to this “heaven” were apparently spectacular features, which, as Jonson puts it, especially pleased the groundlings.[60] Height was necessary for the successful carrying out of such devices. Those sitting in the upper gallery would hardly receive the full benefit of such operations on such a stage as is shown in the Swan sketch.

Not only did gods and goddesses descend from above, but the heavens themselves, as it were, descended in the form of clouds—a spectacular feature that would seem to call for considerable space above the stage as well as height. And clouds, it is to be remembered, were, like curtains, a commonplace in London theatres. They had been descending in Italian, French[61] and English mystery plays[62] for years before Burbage built his theatre, in city pageants,[63] and at court.[64] They were not unknown to special outdoor entertainments;[65] and their apparent frequency in miracle plays is[Pg 27] attested by Palsgrave’s words:[66] “Of whyche the lyke thyng is used to be shewed now adays in stage-playes, when some god or some saynt is made to appeare forth of a cloude: and succoureth the parties which seemed to be towardes some great danger, through the Soudan’s crueltie”. That they were regular features at public theatres as early as 1578-9, is made probable by the entry in the Revels Accounts for that date:[67] “ffor a hoope and blewe Lynnen cloth to mend the clowde that was Borrowed and cut to serve the rocke in the plaie of the burnyng knight and for the hire thereof and setting upp the same where it was borrowed ... x s.” It was “borrowed”, I venture to say, from Burbage’s theatre; and the “setting upp the same where it was borrowed” consisted in replacing it in the “heavens” of the Theatre.

Just how large the clouds[68] were that descended and rose in the public theatres I am unable to say, but there is good reason for thinking that they were of sufficient size to require considerable space in the “heavens” outside the front edge of the balcony; for it is pretty certain that clouds did not descend from the balcony but came straight down from heaven. This was true even at court until the time of Hymenaei, since at the performance of this piece, observed a spectator, the clouds did not descend in the usual and commonplace manner, like a bucket in a well, but came down in a gentle and graceful curve.[69]

Such are the indications that the “hut” extended well forward with a large shadow or cover at its outer edge, a cover which was parallel or virtually parallel to the platform below, which was as high as the ceiling of the upper gallery, and which extended practically to the front edge of the platform below. On such a stage the hanging of curtains between the front pillars is an obvious absurdity.

The DeWitt sketch, to be sure, does not show such pillars and “heavens”. Nor does it show the curtains which the Swan possessed. And granting that the pillars at this particular theatre were set about midway of the stage, as shown in the drawing, even then the curtains cannot be suspended between the pillars, as Reynolds, Archer and Child have shown.

The difficulty here cannot be evaded by saying that the Swan was an entirely different type of stage from those of the regular playhouses, that it was constructed primarily for variety entertainments, or that it was an amphitheatre in the stricter sense, such a structure as apparently was to have been built later in Lincoln-Inn Fields had not the patent been cancelled by James I. Professor C. W. Wallace has recently shown[70] that it was unquestionably used for plays at an early date. DeWitt’s calling it the “largest and most beautiful” of the London theatres shows nothing one way or the other, but the words of John Weever in 1599,[71] while rather vague, seem to be another reference to the Swan as a place for plays:

Another explanation is surely necessary. Child[72] after a very able discussion of the Swan shadow and pillars concludes as follows: “The fact is significant that, just as the Hope, though planned on the lines of the Swan, was to be built of wood, not flint, so, in the contract with the builder, it is directly stated that he shall ’also builde the Heavens all over the saide stage to be borne or carried without any postes or supporters to be fixed or sett uppon the saide stage’. It is possible, therefore, that the pillars of the Swan were as the drawing shows them, and that the pentroof covered half or nearly half the stage; but that the plan was found inconvenient, was confined to the Swan and was discarded by Henslowe when he built the Hope”.

As Child says, the hitting upon such an unhappy and apparently such an uncommon plan is decidedly strange. And as the Swan was certainly not built of flint but of very skillfully painted wood,[73] and as there is no contrast, expressed or implied, between the materials that were to compose the two theatres, the possibility expressed by Child loses its force. Indeed, if one interprets the passage quoted above in connection with what immediately precedes and follows, one is certainly inclined to say that in 1614 the pillars had been removed from the Swan; that the “heavens” at the Hope were to cover the entire stage and yet be borne without pillars, as was the case at the Swan.

It is more likely, however, that the passage in question is not intended to emphasize any similarity to, or deviation from, the Swan stage, but is intended to stress the fact that although the “heaven” is to be a large structure covering the entire stage, it is nevertheless to be supported without the aid of pillars. This problem was solved by attaching the shadow to the roof above the upper gallery, as is shown in the picture, “The Hope in 1647”, printed facing page 238 of Ordish’s Early London Theatres. The discarding of the front pillars,[74] which had never played a part in Elizabethan staging, was necessitated by the fact that the house was designed not only for plays but also for bear-baiting, a sport that would have been rendered practically impossible by pillars resting upon the front of a fixed stage, as was the case at the Swan, Globe and Fortune.[75]

Rather than believe that the Swan was a radical deviation in stage architecture, I prefer to believe that the DeWitt sketch misrepresents the nature of the shadow and front pillars as it[Pg 30] misrepresents other features of the actual Swan theatre. And if I were asked to make my contribution to the conjectures that have been made regarding the manner in which the DeWitt sketch was fashioned, I should be inclined to say that the apparent dip of the shed before the “hut” was not intended to represent a slanting roof, but is a crude attempt of one sketching from the point of view of the upper gallery, or some higher point, to give perspective to the structure. Since this method of showing perspective, however, if entirely carried out, would have resulted in the hiding of the stage itself, it was therefore abandoned, a process necessarily resulting in a curtailed shadow and the erecting of pillars near the middle of the stage.

And would such a guess be more absurd than to suppose that the builders of the “largest and most distinguished” theatre of its time deliberately constructed a more primitive and less convenient type of stage than that which was already in existence; and that this innovation in stage-construction, so impractical and inconvenient as to be discarded later, a stage on which the “firmament” was invisible to some, actors’ costumes were exposed to the weather and curtains virtually impossible, served as a model, as it were, for the Globe and Fortune? If, as Neuendorff affirms, the late sixteenth century was an era of experimentation in theatre-construction and the author of the Swan sketch is to be trusted, then somebody obviously blundered when the most distinguished theatre of its day was built. Granting that it was Langley and his contractor, then we are certainly not justified in assuming that Peter Street and Henslowe, who had built the more “developed” Rose, Burbage and the rest all followed in their footsteps. The blunder, it seems to me, rests with the author of the drawing.

All this is merely an attempt to show what has been known for a long time: the Swan sketch, even if it be correct, cannot be used to prove the prevalence of the vorhanglose Bühne before 1603, or to mark any step in the development of Elizabethan staging or stage-structure. It is at most an astonishing exception. If this is true, if three entrances,[76] upper stages, and stage curtains were apparently regular features of early theatres, there seems to be at least no a priori reason for thinking that the “alcove” or “canopy”[Pg 31] stage did not exist at the two earlier theatres as well as at the Rose.

I agree with Neuendorff that such a type of stage was the result of study and experience. There were, however, abundant opportunities for all these things long before Burbage built his theatre; there were abundant suggestions for such a form of stage, suggestions, too, which could hardly have failed to appeal to the wide-awake Burbage, himself a carpenter. Before discussing these suggestions and the probable origin of the “alcove” or “canopy” stage—good a priori grounds for its early existence—it is necessary to discuss at some length the inn-yard in its relationship to the first regular theatres.

Speaking of the performance of plays at inns, Malone[77] wrote late in the eighteenth century: “We may suppose the stage to have been raised in this area [the inn-yard], on the fourth side, with its back to the gateway of the inn, at which the money for admission was taken. Thus, in fine weather, a playhouse not incommodious might have been formed”. Ever since this conjecture was made, it has been customary to regard the inn-yard as the regular and preferred place for public plays before the building of the first permanent theatres, and to see in it the structural original of these Elizabethan institutions. But was this actually the case? That inn-yard influence in the construction of the early theatres is possible, I would of course not deny, but that the inn-yard was the favorite place for theatrical performances, or that it was structurally the original of the first theatres is at least questionable. The view that the inn-yard stage served as a model for that at the Theatre or Curtain is almost certainly untenable, as, I believe, the following pages will show.

At the beginning of this discussion it must be said that the presentation of plays in inn-yards cannot be questioned. The Act of the Common Council of Dec. 6, 1574,[78] begins: “Whereas hearetofore sondrye greate disorders and Inconvenyences have beene found to ensewe to this Cittie by the inordynate hauntyinge of greate multitudes of people speciallye youthe, to playes, enterludes, and shewes namelye occasyon of ffrayes and quarrelles, eavell practizes of incontinencye In greate Innes, havinge chambers and secrete places adioyninge to their open stagies and gallyries”, etc.

“Open stagies and gallyries” surely refers to the stage erected in the yard and to the galleries of the inn. All the evils of performances, however, were not confined to inn-yard performances, as is shown in the words, “allso soundrye slaughters and mayheminges of the Quenes Subiectes have happened by ruines of Skaffoldes fframes and Stagies, and by engynes weapons and powder used in plaies”.[79] Nor does the passage first quoted necessarily mean that[Pg 33] the majority of plays were being performed in inn-yards. This is shown by the numerous references to early plays in guild-halls, etc.,[80] and by the words in the document quoted above: “Be yt enacted ... that no Inkeper Tavernekeper nor other person what soeu’ wthin the liberties of thys Cittie shall openlye shewe or playe nor cawse or suffer to be openlye shewed or played wthin the hous yarde or anie other place.... And that no person shall suffer anie plays enterludes Comodyes, Tragidies or shewes to be played or shewed in his hous yarde or other place”.[81]

A decree of May 12, 1569, reads: “Forasmuch as thoroughe the greate resort, accesse and assembles of great numbers of multitides of people unto diverse and severall Innes and other places of this Citie, and the liberties & suburbes of the same, to thentent to here and see certayne Stage playes, enterludes, and other disguisinges, on the Saboth dayes and other solempne feastes commaunded by the church to be kept holy, and there being close pestered together is Small romes, specially in this tyme of Sommer, all not being [clene] and voyd of infeccions and diseases, whereby great infeccion ... may arise and growe [it is ordered] ... that no mannour of parson or parsons whatsoever, dwelling or inhabiting within this Citie of London liberties and suburbes of the same, being Inkepers, Tablekepers, Tavernours, hall-kepers or bruers, Do or shall, from and after the last daye of this moneth of May nowe next ensuinge, untill the last day of September then next following, take uppon him or them to set fourth, eyther openly or privatly, anny Stage play or Interludes, or to permit or suffer to be set fourth or played with[in] his or there mansion howse, yarde, Court, Garden, orchard, or other place or places whatsoever ... anny mannour of Stage play, Enterlude, or other disgiusing whatsoever”.[82]

The objection that persons in plague time were “close pestered together in small romes” perhaps determined the phraseology of the letter of May 20, 1572, to the Common Council, “written in favor of certein persones to have in there howses, yardes, or backe sydes, being overt & open places, such playes, enterludes, Commedies,[Pg 34] & tragedies as maye tende to represse vyce & extoll vertwe”.[83] And in view of what precedes, it appears that interior performances rather than performances in the open yards were regarded as particularly dangerous by the Privy Council, which decreed on June 22, 1600: “And especially it is forbidden that any stage plays shall be played (as sometimes they have been) in any common inn, for public assembly in or near about the city”.

Plays, then, were being presented inside taverns and inns as well as in the yards.[84] Not giving this fact due consideration, some scholars have too rashly concluded that the various references of the time to performances in or at inns refer in all cases to inn-yard theatricals. Child,[85] for example, remarks that when Elizabeth came to the throne, “the usual places of public theatrical performances were certain innyards. An account written in 1628 enumerates five of these yards, where plays were publicly performed.” And he mentions the Bell, Bull, Bell Savage, Whitefriars, “nigh Pauls”. This is obviously a reference to a passage quoted by Prynne[86] from Rawlidge’s Monster Lately Found Out, which Halliwell had interpreted as referring to the “yards” of certain well-known inns.[87]

The passage, however, does not speak of inn-yards, but of “the playhouses in Gracious-street”, etc. Nor is it certain that Whitefriars and “nigh Pauls” were really inns. At least it should be noted that “Blackfriars”, which Fleay,[88] and others misled by the inn-yard theory, pronounced an inn, was far from such;[89] and that Paul’s Children probably performed, not at an inn, but in the music room of St. Gregory’s and the yard adjoining the Convocation House.[90] Howes, too, writing about the same time that Rawlidge wrote, it should be remembered, says that five,[91] and not eight,[92][Pg 35] common hostelries had been turned into theatres; while Stockwood, preaching in 1578 when the Theatre, Curtain and Blackfriars were in operation, asserted that he knew of “eighte ordinarie places in the Citie” where plays were presented.[93]

But even granting that Rawlidge’s “playhouses” were inns, then is it at all certain that actors preferred to act in the yards of such structures rather than in the great halls? To be sure, one of Tarleton’s Jests[94] seems to point to a stage in the yard of the Bull. “At the Bull in Bishops-gate-street”, we are told, “where the Queenes players often times played, Tarleton comming on the stage, one from the gallery threw a pippin at him.” “Gallery” certainly implies the gallery around the yard, though the casting of an apple by a fellow who had a “quean to his wife” perhaps does not agree with the accepted view that this gallery was reserved for the better class of spectators. Of more significance is the statement of Flecknoe[95] in 1664, that the early actors were “without any certain Theaters or set Companies, till about the beginning of Queen Elizabeths Reign they began here to assemble into Companies, and set up Theatres, first in the City (as in the Inn-yards of the Cross-Keyes and Bull in Grace and Bishops-gate Street at this day is to be seen.)”

The lateness of this document and its vagueness make it of little value in our discussion. Flecknoe may possibly mean that “Theatres” had been recently set up and were, in 1664, being used for plays at the Bull and Cross Keys. The passage more probably means, however, that the “Theatres” erected in the yards of the Bull and Cross Keys, in the sixteenth century, were still to be seen. It is difficult to believe, however, that structures erected in such places would have remained in existence for over sixty years,[96] including the destructive period of the Commonwealth.[97] Certainly[Pg 36] this would not have happened had the inn-yard “theatres” been simple or removable structures. If Flecknoe’s statement is to be accepted to prove the inn-yards to be the regular places for performances, then, it is to be also used to show that actors did not regard them as ready-made places for plays. Furthermore Howes’ earlier statement that five common hostelries had been turned into theatres suggests improvements. Stockwood’s statement in 1578, that there were “eight ordinarie places” in London for plays, together with Harrison’s very uncertain passage[98] describing the banishment in 1572 of plays out of London and the reflection that it is a sign of evil times “when plaiers wexe so riche that they can build suche houses”, may indicate, too, that inn-yards were by no means regarded as ready-made theatres even before 1576.

There is also one bit of evidence which seems to contradict Flecknoe’s statement that the regular “playing place” at the Bull was located in the yard. On July 1, 1582, the Earl of Warwick wrote to the Lord Mayor asking permission for John David to play his prize at fencing at the Bull in Bishopsgate. On the 23 of the same month he again wrote complaining of the Mayor’s ignoring his request. In the reply of the latter appear the words: “Onely I did restraine him from playeng in an Inne, wch was somewhat to close for infection and appointed him to playe in an open place of the leaden hall more fre from danger”. Further on he writes: “I have herein yet further done for yor servante what I may, that is that if he obtaine lawfully to playe at the Theatre or other open place out of the Citie, he hath and shall have my permition”, etc.[99] “Close” contrasted with “open” certainly implies interior performances in inns where conditions were especially favorable for the spreading of the plague.[100] These passages, taken with those cited above, show in all probability what[Pg 37] was the real condition of affairs; that is, actors performed sometimes in the yards, sometimes in the halls of the inns used regularly for theatrical purposes. When plays were to be presented during rain[101] or darkness, the actors would naturally use the halls; when danger of the plague was imminent, they would repair to the “open” yards.

Another thing must be considered. It is apparent that when London players traveled in the provinces, they preferred to set up their stages, not in the inn-yards, but in the town-halls. This is well brought out in the various licences and petitions of the time. The licence of 1574 granted to Burbage and others does not specify that they are allowed to perform in town-halls; but that this was taken for granted and they set up their stages where they pleased, is implied in early documents.[102] On Feb. 16, 1595, Lord Dudley issued a warrant to Francis Coffyn and Richard Bradshaw “to travel in the quality of playing and to use music in all cities, towns and corporations”, requesting for them “the use of the Towne Hall or other place and countenance”.[103] In Dec. 1606, Derby wrote the Mayor of Chester regarding his players, adding in a postscript, “I would request you to lett them have the toune hall to playe in the hall.”[104]

The licence to the King’s Players in 1603 takes care to specify that the players are allowed to play, not only at the Globe, but “alsoe within anie towne halls or Monte halls or other conveniente places” in the outlying towns.[105] This last phrase is repeated in the licence of 1604 to the Queen’s Players,[106] and in that of 1606 to Prince Henry’s Players[107] and that of 1609 to the Queen’s Servants.[108] “Schoole howses” and “guild-halls” are added in the licences of 1610 and 1611 to the Duke of York’s Players[109] and[Pg 38] those of Lady Elizabeth,[110] while that to the Elector Palatine’s Servants[111] in 1613 and the one to the King’s Men[112] in 1619 return to the older phraseology.

Now this specific mentioning of mote-halls and town-halls was due to the fact that actors desiring to perform in these places met with opposition by the various city governments. Fearing that city documents and other property might be damaged[113] by such performances, the Mayor and his associates sometimes bought off licenced players, as was the case at Leicester[114] in 1588 and 1589, where a resolution had been passed on November 17, 1582, that no players except those of the Queen and Lords of the Privy Council were to be suffered “to playe att the Towne Hall ... and then butt onlye before the Mayor & his bretherne”.[115] Sometime between 1600 and 1622, the authorities at Worcester decreed “that noe playes bee had or made in the upper end of the Towne-hall of this city, nor council chamber used by any players whatsoever, and that noe playes be had or made in yeald by night tyme, and yf anie players be admytted to play in the yeald hall to be admytted to play in the lower end onlie”.[116] At a later date, 1623, a law was passed at Southampton, prohibiting further performances in the town-hall, since plays there were “very hurtfull troublesome and inconvenyent for that the table, benches and fourmes theire sett and placed for holdinge the Kinges Courtes are by those meanes broken and spoyled”.[117]

Such records as these, as well as the numerous references to town-hall performances, show pretty clearly what the players regarded as the most desirable place in which to set up their stages. The remark of Chambers[118] that after giving their first performance, “the Mayor’s play”, in the guild-hall, actors “would find a profitable pitch in the courtyard of some old-fashioned inn with its convenient range of outside galleries”, does not seem to be borne[Pg 39] out entirely by the records. They obviously preferred the town-hall and used it when possible. This may be partly due to the fact that night performances were rather frequent in the provinces. It may be, too, that plays at inns are not regularly mentioned in the city records; yet in spite of this possibility, one is, I believe, warranted in thinking that actors as a rule found it desirable to use the town-hall whenever possible,[119] rather than to set up their stages in the inn-yards which have so often been called ready-made theatres for dramatic performances. Under such circumstances the question naturally arises whether after all the London theatres were so much indebted structurally to the inn-yard as has been generally supposed.

Some of the so-called “survivals” of the inn-yard period are of no value one way or the other in any attempt to show whether the inn-yard was or was not the structural original of the public theatre. The fact, for example, that both inns and theatres were provided with signs has no weight, when we remember that tenements, brewing-houses, stews, printing-shops, and other Elizabethan institutions were likewise equipped with these conveniences. The term “Yard”, said to have been carried over into the theatre from its immediate prototype, is virtually the inevitable term to be applied to a ground space closed in on all sides. The inn as the usual adjunct of an Elizabethan theatre was, says Ordish,[120] “a survival of the inn-yard performances”. The Elizabethans, however, had a sense for business as well as the men who at the present time conduct bars as adjuncts to their theatres.

Other matters deserve more consideration. Getting his idea from the Swan picture, Mr. Appleton Morgan[121] asserts that the putting of the entrance at the side of the stage instead of at the[Pg 40] opposite end of the yard is “a blind following of the inn-yard custom”. But what he regards as the entrance to the Swan was not intended to represent such. The “ingressus” is simply a rough attempt to draw an entrance to the “orchestra”. There is another one opposite to it.

The public theatres were roofless, we are sometimes led to believe, because roofs were lacking at their immediate prototypes; but surely the real reason that prompted Burbage and Langley to construct open houses rather than roofed ones was something other than a lazy or blind inclination to follow inn-yard precedent. Easy and adequate lighting and general publicity[122] in stage presentation were no doubt weighty considerations; but of prime importance was the necessity of meeting the growing complaint that playing houses were “somewhat to close for infection”, the “state of pestilence” where plague-inflicted persons were accustomed to be “pestered together in Small romes, specially in this tyme of Sommer”. This objection, as we have already seen, actors had attempted to meet by presenting their plays in courts and inn-yards; to meet the same objection Burbage and his followers erected “overt & open places” for their performances. And under the circumstances there seems to be no special reason for believing that the idea of a roofless structure was suggested by the inn-yards rather than by the “game houses”, banqueting houses or bear gardens of the period. At least actors were not following inn-yard precedent blindly.