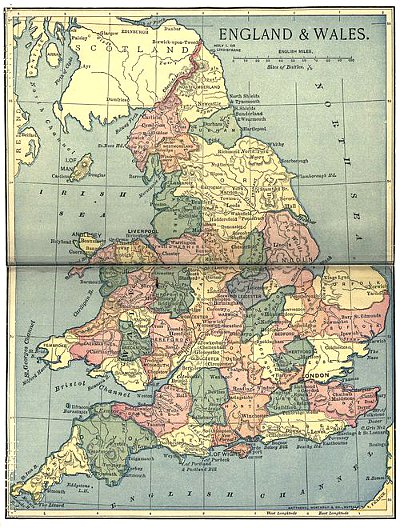

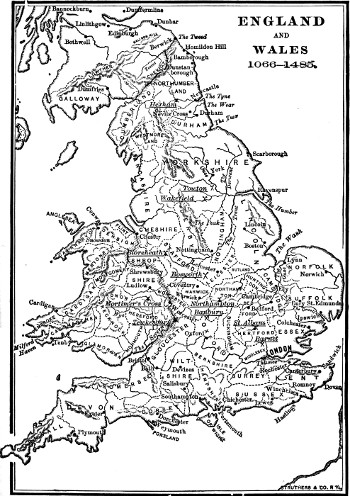

ENGLAND & WALES.

ENGLAND & WALES.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Leading Facts of English History

Date of first publication: 1895

Author: David Henry Montgomery (1837-1928)

Date first posted: December 27 2012

Date last updated: December 27 2012

Faded Page eBook #20121245

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Paul Dring & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

(This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

SECOND EDITION, REVISED.

BOSTON, U.S.A.:

GINN & COMPANY, PUBLISHERS.

1894.

Most of the materials for this book were gathered by the writer during several years’ residence in England.

The attempt is here made to present them in a manner that shall illustrate the great law of national growth, in the light thrown upon it by the foremost English historians.

The authorities for the different periods will be found in the List of Books on page 434; but the author desires to particularly acknowledge his indebtedness to the works of Gardiner, Guest, and Green, and to the excellent constitutional histories of Taswell-Langmead and Ransome.

SECOND EDITION.

The present edition has been very carefully revised throughout, and numerous maps and genealogical tables have been added.

The author’s hearty thanks are due to G. Mercer Adam, Esq., of Toronto, Canada; Prof. W. F. Allen, of The University of Wisconsin; President Myers, of Belmont College, Ohio; Prof. George W. Knight, of Ohio State University; and to Miss M. A. Parsons, teacher of history in the High School, Winchester, Mass., for the important aid which they have kindly rendered.

DAVID H. MONTGOMERY,

Cambridge, Mass.

THE

LEADING FACTS OF ENGLISH HISTORY.

BRITAIN BEFORE WRITTEN HISTORY BEGINS.

THE COUNTRY.

[Pg 1] 1. Britain once a Part of the Continent.—The island of Great Britain has not always had its present form. Though separated from Europe now by the English Channel and the North Sea, yet there is abundant geological evidence that it was once a part of the continent.

2. Proofs.—The chalk cliffs of Dover are really a continuation of the chalk of Calais, and the strait dividing them, which is nowhere more than thirty fathoms deep,[2] is simply the result of a [Pg 2] slight and comparatively recent depression in that chalk. The waters of the North Sea are also shallow, and in dredging, great quantities of the same fossil remains of land animals are brought up which are found buried in the soil of England, Belgium, and France. It would seem, therefore, that there can be no reasonable doubt that the bed of this sea, where these creatures made their homes, must once have been on a level with the countries whose shores it now washes.

3. Appearance of the Country.—What we know to-day as England, was at that time a western projection of the continent, wild, desolate, and without a name.[3] The high hill ranges show unmistakable marks of the glaciers which once ploughed down their sides, and penetrated far into the valleys, as they still continue to do among the Alps.

4. The Climate.—The climate then was probably like that of Greenland now. Europe was but just emerging, if, indeed, it had begun to finally emerge, from that long period during which the upper part of the northern hemisphere was buried under a vast field of ice and snow.

5. Trees and Animals.—The trees and animals corresponded to the climate and the country. Forests of fir, pine, and stunted oak, such as are now found in latitudes much farther north, covered the lowlands and the lesser hills. Through these roamed the reindeer, the mammoth, the wild horse, the bison or “buffalo,” and the cave-bear.

MAN.—THE ROUGH-STONE AGE.

6. His Condition.—Man seems to have taken up his abode in Britain before it was severed from the mainland. His condition was that of the lowest and most brutal savage. He probably stood apart, even from his fellow-men, in selfish isolation; if so, he was [Pg 3] bound to no tribe, acknowledged no chief, obeyed no law. All his interests were centred in himself and in the little group which constituted his family.

7. How he lived.—His house was the first empty cave he found, or a rude rock-shelter made by piling up stones in some partially protected place. Here he dwelt during the winter. In summer, when his wandering life began, he built himself a camping place of branches and bark, under the shelter of an overhanging cliff by the sea, or close to the bank of a river. He had no tools. When he wanted a fire he struck a bit of flint against a lump of iron ore, or made a flame by rubbing two dry sticks rapidly together. His only weapon was a club or a stone. As he did not dare encounter the larger and fiercer animals, he rarely ventured into the depths of the forests, but subsisted on the shellfish he picked up along the shore, or on any chance game he might have the good fortune to kill, to which, as a relish, he added berries or pounded roots.

8. His First Tools and Weapons.—In process of time he learned to make rough tools and weapons from pieces of flint, which he chipped to an edge by striking them together. When he had thus succeeded in shaping for himself a spear-point, or had discovered how to make a bow and to tip the arrows with a sharp splinter of stone, his condition changed. He now felt that he was a match for the beasts he had fled from before. Thus armed, he slew the reindeer and the bison, used their flesh for food, their skins for clothing, while he made thread from their sinews, and needles and other implements from their bones. Still, though he had advanced from his first helpless state, his life must have continued to be a constant battle with the beasts and the elements.

9. His Moral and Religious Nature.—His moral nature was on a level with his intellect. No questions of conscience disturbed him. In every case of dispute might made right.

His religion was the terror inspired by the forces and convulsions [Pg 4] of nature, and the dangers to which he was constantly exposed. Such, we have every reason to believe, was the condition of the Cave-Man who first inhabited Britain, and the other countries of Europe and the East.

10. Duration of the Rough-Stone Age.—The period in which he lived is called the Old or Rough-Stone Age, a name derived from the implements then in use.

When that age began, or when it came to a close, are questions which at present cannot be answered. But we may measure the time which has elapsed since man appeared in Britain by the changes which have taken place in the country. We know that sluggish streams like the Avon, with whose channel the lapse of many centuries has made scarcely any material difference, have, little by little, cut their way down through beds of gravel till they have scooped out valleys sometimes a hundred feet deep. We know also the climate is wholly unlike now what it once was, and that the animals of that far-off period have either wholly disappeared from the globe or are found only in distant regions.

The men who were contemporary with them have vanished in like manner. But that they were contemporary we may feel sure from two well-established grounds of evidence.

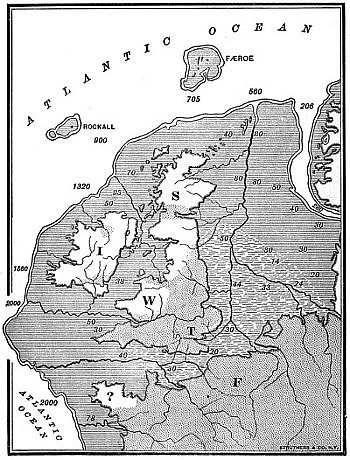

BRITAIN BEFORE ITS SEPARATION FROM THE CONTINENT OF EUROPE.

BRITAIN BEFORE ITS SEPARATION FROM THE CONTINENT OF EUROPE.The dark lines represent land, now submerged.

The dotted area, that occupied by animals.

The white land area, portions once covered by glaciers.

The figures show the present depth of sea in fathoms.

F. (France), T. (Thames), W. (Wales), S. (Scotland), I. (Ireland).

?, doubtful area, but probably glacial.

11. Remains of the Rough-Stone Age.—First, their flint knives and arrows are found in the caves, mingled with ashes and with the bones of the animals on which they feasted; these bones having been invariably split in order that they might suck out the marrow.[4] Next, we have the drawings they made of those very creatures scratched on a tusk or on a smooth piece of slate with a bit of sharp-pointed quartz.[5] Nearly everything else has perished; [Pg 5] even their burial places, if they had any, have been swept away by the destroying action of time. Yet these memorials have come down to us, so many fragments of imperishable history, made by that primeval race who possessed no other means of recording the fact of their existence and their work.

THE AGE OF POLISHED STONE.

12. The Second Race; Britain an Island.—Following the Cave-Men, there came a higher race who took possession of the country; these were the men of the New or Polished-Stone Age. When they reached Britain, it had probably become an island. Long before their arrival the land on the east and south had been slowly sinking, till at last the waters of the North Sea crept in and made the separation complete. The new-comers appear to have brought with them the knowledge of grinding and polishing stone, and of shaping it into hatchets, chisels, spears, and other weapons and utensils.[6] They did not, like the race of the Rough-Stone Period, depend upon such chance pieces of flint as they might pick up, and which would be of inferior quality, but they had regular quarries for digging their supplies. They also obtained polished-stone implements of a superior kind from the inhabitants of the continent, which they in turn got by traffic with Asiatic countries.

13. Government and Mode of Life.—These people were organized into tribes or clans under the leadership of a chief. They lived in villages or “pit circles” consisting of a group of holes dug in the ground, each large enough to accommodate a family. These pits were roofed over with branches covered with [Pg 6] slabs of baked clay. The entrance to them was a long, inclined passage, through which the occupants crawled on their hands and knees.

Armed with their stone hatchets, these men were able to cut down trees and to make log canoes in which they crossed to the mainland. They could also undertake those forest clearings which had been impossible before. The point, however, of prime difference and importance was their mode of subsistence.

14. Farming and Cattle-Raising.—Unlike their predecessors, this second race did not depend on hunting and fishing alone, but were herdsmen and farmers as well. They had brought from other countries such cereals as wheat and barley, and such domestic animals as the ox, sheep, hog, horse, and dog. Around their villages they cultivated fields of grain, while in the adjacent woods and pastures they kept herds of swine and cattle.

15. Arts.—They had learned the art of pottery, and made dishes and other useful vessels of clay, which they baked in the fire. They raised flax and spun and wove it into coarse, substantial cloth. They may also have had woollen garments, though no remains of any have reached us, perhaps because they are more perishable than linen. They were men of small stature, with dark hair and complexion, and it is supposed that they are represented in Great Britain to-day by the inhabitants of Southern Wales.

16. Burial of the Dead.—They buried their dead in long mounds, or barrows, some of which are upward of three hundred feet in length. These barrows were often made by setting up large, rough slabs of stone so as to form one or more chambers which were afterward covered with earth. In some parts of England these burial mounds are very common, and in Wiltshire, several hundred occur within the limits of an hour’s walk.

During the last twenty years many of these mounds have been opened and carefully explored. Not only the remains of the builders have been discovered in them, but with them their tools and weapons. In addition to these, earthen dishes for holding [Pg 7] food and drink have been found, placed there it is supposed, to supply the wants of the spirits of the departed, as the American Indians still do in their interments. When a chief or great man died, it appears to have been the custom of the tribe to hold a funeral feast, and the number of cleft human skulls dug up in such places has led to the belief that prisoners of war may have been sacrificed and their flesh eaten by the assembled guests in honor of the dead. Be that as it may, there are excellent grounds for supposing that these tribes were constantly at war with each other, and that their battles were characterized by all the fierceness and cruelty which uncivilized races nearly everywhere exhibit.

THE BRONZE AGE.

17. The Third Race.—But great as was the progress which the men of the New or Polished-Stone Age had made, it was destined to be surpassed. A people had appeared in Europe, though at what date cannot yet be determined, who had discovered how to melt and mingle two important metals, copper and tin.

18. Superiority of Bronze to Stone.—The product of that mixture, named bronze, perhaps from its brown color, had this great advantage: a stone tool or weapon, though hard, is brittle; but bronze is not only hard, but tough. Stone, again, cannot be ground to a thin cutting edge, whereas bronze can. Here, then, was a new departure. Here was a new power. From that period the bronze axe and the bronze sword, wielded by the muscular arms of a third and stronger race, became the symbols of a period appropriately named the Age of Bronze. The men thus equipped invaded Britain. They drove back or enslaved the possessors of the soil. They conquered the island, settled it, and held it as their own until the Roman legions, armed with swords of steel, came in turn to conquer them.

19. Who the Bronze-Men were, and how they lived.—The Bronze-Men may be regarded as offshoots of the Celts, a large-limbed, [Pg 8] fair-haired, fierce-eyed people, that originated in Asia, and overran Central and Western Europe. Like the men of the Age of Polished Stone, they lived in settlements under chiefs and possessed a rude sort of government. Their villages were built above ground and consisted of circular houses somewhat resembling Indian wigwams. They were constructed of wood, chinked in with clay, having pointed roofs covered with reeds, with an opening to let out the smoke and let in the light. Around these villages the inhabitants dug a deep ditch for defence, to which they added a rampart of earth surmounted by a palisade of stout sticks, or by felled trees piled on each other. They kept sheep and cattle. They raised grain, which they deposited in subterranean storehouses for the winter. They not only possessed all the arts of the Stone-Men, but in addition, they were skilful workers in gold, of which they made necklaces and bracelets. They also manufactured woollen cloth of various textures and brilliant colors.

They buried their dead in round barrows or mounds, making for them the same provision that the Stone-Men did. Though divided into tribes and scattered over a very large area, yet they all spoke the same language; so that a person would have been understood if he had asked for bread and cheese in Celtic anywhere from the borders of Scotland to the southern boundaries of France.

20. Greek Account of the Bronze-Men of Britain.—At what time the Celts came into Britain is not known, though some writers suppose that it was about 500 B.C. However that may be, we learn something of their mode of life two centuries later from the narrative of Pytheas,[7] a learned Greek navigator and geographer who made a voyage to Britain at that time. He says he saw plenty of grain growing, and that the farmers gathered the sheaves at harvest into large barns, where they threshed it under cover, the fine weather being so uncertain in the island that they could not do it out of doors, as in countries farther south. Here, then, we [Pg 9] have proof that the primitive Britons saw quite as little of the sun as their descendants do now. Another characteristic discovery made by Pytheas was that the farmers of that day had learned to make beer and liked it. So that here, again, the primitive Briton was in no way behind his successors.

21. Early Tin Trade of Britain.—Of their skill in mining Pytheas does not speak, though from that date, and perhaps many centuries earlier, the inhabitants of the southern part of the island carried on a brisk trade in tin ore with merchants of the Mediterranean. Indeed, if tradition can be depended upon, Hiram, king of Tyre, who reigned over the Phœnicians, a people particularly skilful in making bronze, and who aided Solomon in building the Jewish temple, may have obtained his supplies of tin from the British Isles. At any rate, about the year 300 B.C., a certain Greek writer speaks of the country as then well known, calling it Albion, or the “Land of the White Cliffs.”

22. Introduction of Iron.—About a century after that name was given, the use of bronze began to be supplemented to some extent by the introduction of iron. Cæsar tells us that rings of it were employed for money; if so, it was probably by tribes in the north of the island, for the men of the south had not only gold and silver coins at that date, but what is more, they had learned how to counterfeit them.

Such were the inhabitants the Romans found when they invaded Britain in the first century before the Christian era. Rude as these people seemed to Cæsar as he met them in battle array clad in skins, with their faces stained with the deep blue dye of the woad plant, yet they proved no unworthy foemen even for his veteran troops.

23. The Religion of the Primitive Britons; the Druids.—We have seen that they held some dim faith in an overruling power and in a life beyond the grave, since they offered human sacrifices to the one, and buried the warrior’s spear with [Pg 10] him, that he might be provided for the other. Furthermore, the Britons when Cæsar invaded the country had a regularly organized priesthood, the Druids, who appear to have worshipped the heavenly bodies. They dwelt in the depths of the forests, and venerated the oak and the mistletoe. There in the gloom and secrecy of the woods they raised their altars; there, too, they offered up criminals to propitiate their gods. They acted not only as interpreters of the divine will, but they held the savage passions of the people in check, and tamed them as wild beasts are tamed. Besides this, they were the repositories of tradition, custom, and law. They were also prophets, judges, and teachers. Lucan, the Roman poet, declared he envied them their belief in the indestructibility of the soul, since it banished that greatest of all fears, the fear of death. Cæsar tells us that “they did much inquire, and hand down to the youth concerning the stars and their motions, concerning the magnitude of the earth, concerning the nature of things, and the might and power of the immortal gods.”[8] They did more; for they not only transmitted their beliefs and hopes from generation to generation, but they gave them architectural power and permanence in the massive columns of hewn stone, which they raised in that temple open to the sky, the ruins of which are still to be seen on Salisbury Plain. There, on one of those fallen blocks, Carlyle and Emerson sat and discussed the great questions of the Druid philosophy when they made their pilgrimage to Stonehenge[9] more than forty years ago.

24. What we owe to Primitive or Prehistoric Man.—The [Pg 11] Romans, indeed, looked down upon these people as barbarians; yet it is well to bear in mind that all the progress which civilization has since made is built on the foundations which they slowly and painfully laid during unknown centuries of toil and strife. It is to them that we owe the taming of the dog, horse, and other domestic animals, the first working of metals, the beginning of agriculture and mining, and the establishment of many salutary customs which help not a little to bind society together to-day.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF ENGLAND IN RELATION TO ITS HISTORY.[10]

[Pg 12] 25. Geography and History.—As material surroundings strongly influence individual life, so the physical features—situation, surface, and climate—of a country have a marked effect on its people and its history.

26. The Island Form; Race Settlements—the Romans.—The insular form of Britain gave it a certain advantage over the continent during the age when Rome was subjugating the barbarians of Northern and Western Europe. As their invasions could only be by sea, they were necessarily on a comparatively small scale. This perhaps is one reason why the Romans did not succeed in establishing their language and laws in the island. They conquered and held it for centuries, but they never destroyed its individuality; they never Latinized it as they did France and Spain.

[Pg 13] 27. The Saxons.—In like manner, when the power of Rome fell and the northern tribes overran and took possession of the Empire, they were in a measure shut out from Britain. Hence the Saxons, Angles, and Jutes could not pour down upon it in countless hordes, but only by successive attacks. This had two results: first, the native Britons were driven back only by degrees—thus their hope and courage were kept alive and transmitted; next, the conquerors settling gradually in different sections built up independent kingdoms. When in time the whole country came under one sovereignty the kingdoms, which had now become shires or counties, retained through their chief men an important influence in the government, thus preventing the royal power from becoming absolute.

28. The Danes and Normans.—In the course of the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries, the Danes invaded the island, got possession of the throne, and permanently established themselves in the northern half of England, as the country was then called. They could not come, however, with such overwhelming force as either to exterminate or drive out the English, but were compelled to unite with them, as the Normans did later in their conquest under William of Normandy. Hence, every conquest of the island ended in a compromise, and no one race got complete predominance. Eventually all mingled and became one people.

29. Earliest Names: Celtic.—The steps of English history may be traced to a considerable extent by geographical names. Thus the names of most of the prominent natural features, the hills, and especially the streams, are British or Celtic, carrying us back to the Bronze Age, and perhaps even earlier. Familiar examples of this are found in the name, Malvern Hills, and in the word Avon (“the water”), which is repeated many times in England and Wales.

30. Roman Names.—The Roman occupation of Britain is shown by the names ending in “cester,” or “chester” (a corruption of castra, a camp). Thus Leicester, Worcester, Dorchester, [Pg 14] Colchester, Chester, indicate that these places were walled towns and military stations.

31. Saxon Names.—On the other hand, the names of many of the great political divisions, especially in the south and east of England, mark the Saxon settlements, such as Essex (the East Saxons), Sussex (the South Saxons), Middlesex (the Middle or Central Saxons). In the same way the settlement of the two divisions of the Angles on the coast is indicated by the names Norfolk (the North folk) and Suffolk (the South folk)[11].

32. Danish Names.—The conquests and settlements of the Danes are readily traced by the Danish termination “by” (an abode or town), as in Derby, Rugby, Grimsby. Names of places so ending, which may be counted by hundreds, occur with scarce an exception north of London. They date back to the time when Alfred made the treaty of Wedmore,[12] by which the Danes agreed to confine themselves to the northern half of the country.

33. Norman Names.—The conquest of England by the Normans created but few new names. These, as in the case of Richmond and Beaumont, generally show where the invading race built a castle or an abbey, or where, as in Montgomeryshire, they conquered and held a district in Wales.

While each new invasion left its mark on the country, it will be seen that the greater part of the names of counties and towns are of Roman, Saxon, or Danish origin; so that, with some few and comparatively unimportant exceptions, the map of England remains to-day in this respect what those races made it more than a thousand years ago.

34. Eastern and Western Britain.—As the southern and eastern coasts of Britain were in most direct communication with the continent and were first settled, they continued until modern [Pg 15] times to be the wealthiest, most civilized, and progressive part of the island. Much of the western portion is a rough, wild country. To it the East Britons retreated, keeping their primitive customs and language, as in Wales and Cornwall. In all the great movements of religious or political reform, up to the middle of the seventeenth century, we find the people of the eastern half of the island on the side of a larger measure of liberty; while those of the western half, were in favor of increasing the power of the king and the church.

35. The Channel in English History.—The value of the Channel to England, which has already been referred to in its early history, may be traced down to our own day.

In 1264, when Simon de Montfort was endeavoring to secure parliamentary representation for the people, the king (Henry III.) sought help from France. A fleet was got ready to invade the country and support him, but owing to unfavorable weather it was not able to sail in season, and Henry was obliged to concede the demands made for reform.[13]

Again, at the time of the threatened attack by the Spanish Armada, when the tempest had dispersed the enemy’s fleet and wrecked many of its vessels, leaving only a few to creep back, crippled and disheartened, to the ports whence they had so proudly sailed, Elizabeth fully recognized the value of the “ocean-wall” to her dominions.

So a recent French writer,[14] speaking of Napoleon’s intended expedition, which was postponed and ultimately abandoned on account of a sudden and long-continued storm, says, “A few leagues of sea saved England from being forced to engage in a war, which, if it had not entirely trodden civilization under foot, would have certainly crippled it for a whole generation.” Finally, to quote the words of Prof. Goldwin Smith, “The English Channel, by exempting England from keeping up a large standing army [Pg 16] [though it has compelled her to maintain a powerful and expensive navy], has preserved her from military despotism, and enabled her to move steadily forward in the path of political progress.”

36. Climate.—With regard to the climate of England,—its insular form, geographical position, and especially its exposure to the warm currents of the Gulf Stream, give it a mild temperature particularly favorable to the full and healthy development of both animal and vegetable life. Nowhere is found greater vigor or longevity. Charles II. said that he was convinced that there was not a country in the world where one could spend so much time out of doors comfortably as in England; and he might have added that the people fully appreciate this fact and habitually avail themselves of it.

37. Industrial Division of England.—From an industrial and historical point of view, the country falls into two divisions. Let a line be drawn from Whitby, on the northeast coast, to Leicester, in the midlands, and thence to Exmouth, on the southwest coast.[15] On the upper or northwest side of that line will lie the coal and iron, which constitute the greater part of the mineral wealth and manufacturing industry of England; and also all the large places except London. On the lower or southeast side of it will be a comparatively level surface of rich agricultural land, and most of the fine old cathedral cities[16] with their historic associations; in a word, the England of the past as contrasted with modern and democratic England, that part which has grown up since the introduction of steam.

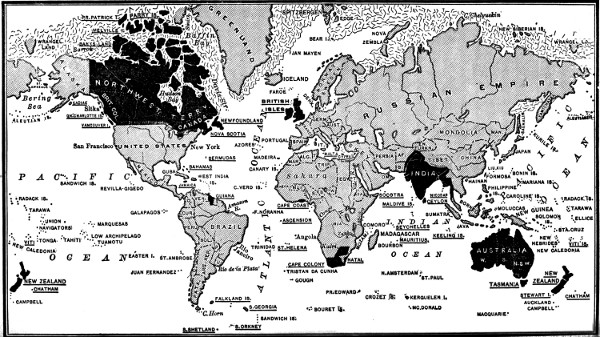

38. Commercial Situation of England.—Finally, the position of England with respect to commerce is worthy of note. It is not only possessed of a great number of excellent harbors, but it is situated in the most extensively navigated of the oceans, between the two continents having the highest civilization and the most [Pg 17] constant intercourse. Next, a glance at the map[17] will show that geographically England is located at about the centre of the land masses of the globe. It is evident that an island so placed stands in the most favorable position for easy and rapid communication with every quarter of the world. On this account England has been able to attain and maintain the highest rank among maritime and commercial powers.

It is true that since the opening of the Suez Canal, in 1869, the trade with the Indies and China has changed. Many cargoes of teas, silks, and spices, which formerly went to London, Liverpool, or Southampton, and were thence reshipped to different countries of Europe, now pass by other channels direct to the consumer. But aside from this, England still retains her supremacy as the great carrier and distributer of the productions of the earth—a fact which has had and must continue to have a decided influence on her history and on her relations with other nations, both in peace and war.

“Force and Right rule the world: Force, till Right is ready.”

Joubert.

ROMAN BRITAIN, 55 B.C. 43-410 A.D.

A CIVILIZATION WHICH DID NOT CIVILIZE.

[Pg 18] 39. Europe at the Time of Cæsar’s Invasion of Britain.—Before considering the Roman invasion of Britain let us take a glance at the condition of Europe. We have seen that the Celtic tribes of the island, like those of Gaul (France), were not mere savages. On the contrary, we know that they had taken more than one important step in the path of progress; still, the advance should not be overrated. For, north of the shores of the Mediterranean, there was no real civilization. Whatever gain the men of the Bronze Age had made, it was nothing compared to what they had yet to acquire. They had neither organized legislatures, written codes of law, effectively trained armies, nor extensive commerce. They had no great cities, grand architecture, literature, painting, music, or sculpture. Finally, they had no illustrious and imperishable names. All these belonged to the Republic of Rome, or to the countries to the south and east, which the arms of Rome had conquered.

40. Cæsar’s Campaigns.—Such was the state of Europe when Julius Cæsar, who was governor of Gaul, but who aspired to be ruler of the world, set out on his first campaign against the tribes north of the Alps. (58 B.C.)

In undertaking the war he had three objects in view: first, he wished to crush the power of those restless hordes that threatened the safety, not only of the Roman provinces, but of the Republic [Pg 19] itself. Next, he sought military fame as a stepping-stone to supreme political power. Lastly, he wanted money to maintain his army and to bribe the party leaders of Rome. To this end every tribe which he conquered would be forced to pay him tribute in cash or slaves.

41. Cæsar reaches Boulogne; resolves to cross to Britain.—In three years Cæsar had subjugated the enemy in a succession of victories, and Europe lay virtually helpless at his feet. Late in the summer of 55 B.C. he reached that part of the coast of Gaul where Boulogne is now situated, opposite which one may see on a clear day the gleaming chalk cliffs of Dover, so vividly described in Shakespeare’s “Lear.” While encamped on the shore he “resolved,” he says, “to pass over into Britain, having had trustworthy information that in all his wars with the Gauls the enemies of the Roman Commonwealth had constantly received help from thence.”[18]

42. Britain not certainly known to be an Island.—It was not known then with certainty that Britain was an island. Many confused reports had been circulated respecting that strange land in the Atlantic on which only a few adventurous traders had ever set foot. It was spoken of in literature as “another world,” or, as Plutarch called it, “a country beyond the bounds of the habitable globe.”[19] To that other world the Roman general, impelled by ambition, by curiosity, by desire of vengeance, and by love of gain, determined to go.

43. Cæsar’s First Invasion, 55 B.C.—Embarking with a force of between eight and ten thousand men[20] in eighty small vessels, Cæsar crossed the Channel and landed not far from Dover, where he overcame the Britons, who made a desperate resistance. After [Pg 20] a stay of a few weeks, during which he did not leave the coast, he returned to Gaul.

44. Second Invasion, 54 B.C.—The next year, a little earlier in the season, Cæsar made a second invasion with a much larger force, and penetrated the country to a short distance north of the Thames. Before the September gales set in, he re-embarked for the continent, never to return. The total result of his two expeditions was, a number of natives, carried as hostages to Rome, a long train of captives destined to be sold in the slave-markets, and some promises of tribute which were never fulfilled. Tacitus remarks, “He did not conquer Britain; he only showed it to the Romans.”

Yet so powerful was Cæsar’s influence, that his invasion was spoken of as a splendid victory, and the Roman Senate ordered a thanksgiving of twenty days, in gratitude to the gods and in honor of the achievement.

45. Third Invasion of Britain, 43 A.D.—For nearly a hundred years no further attempt was made, but in 43 A.D., after Rome had become a monarchy, the Emperor Claudius ordered a third invasion of Britain, in which he himself took part.

This was successful, and after nine years of fighting, the Roman forces overcame Caractacus, the leader of the Britons.

46. Caractacus carried Captive to Rome.—In company with many prisoners, Caractacus was taken in chains to Rome. Alone of all the captives, he refused to beg for life or liberty. “Can it be possible,” said he, as he was led through the streets, “that men who live in such palaces as these envy us our wretched hovels!”[21] “It was the dignity of the man, even in ruins,” says Tacitus, “which saved him.” The Emperor, struck with his bearing and his speech, ordered him to be set free.

47. The First Roman Colony planted in Britain.—Meanwhile the armies of the Empire had firmly established themselves in the [Pg 21] southeastern part of the island. There they formed the colony of Camulodunum, the modern Colchester. There, too, they built a temple and set up the statue of the Emperor Claudius, which the soldiers worshipped, both as a protecting god and as a representative of the Roman state.

48. Llyn-din.[22]—The army had also conquered other places, among which was a little native settlement on one of the broadest parts of the Thames. It consisted of a few miserable huts and a row of entrenched cattle-pens. This was called in the Celtic or British tongue Llyn-din or the Fort-on-the-lake, a word which, pronounced with difficulty by Roman lips, became that name which the world now knows wherever ships sail, trade reaches, or history is read,—London.

49. Expedition against the Druids.—But in order to complete the conquest of the country, the Roman generals saw that it would be necessary to crush the power of the Druids, since their passionate exhortations kept patriotism alive. The island of Mona, now Anglesea, off the coast of Wales, was the stronghold to which the Druids had retreated. As the Roman soldiers approached to attack them, they beheld the priests and women standing on the shore, with uplifted hands, uttering “dreadful prayers and imprecations.” For a moment they hesitated, then urged by their general, they rushed upon them, cut them to pieces, levelled their consecrated groves to the ground, and cast the bodies of the Druids into their own sacred fires. From this blow, Druidism as an organized faith never recovered, though traces of its religious rites still survive in the use of the mistletoe at Christmas and in May-day festivals.

50. Revolt of Boadicea.—Still the power of the Latin legions was only partly established, for while Suetonius was absent with his troops at Mona, a formidable revolt had broken out in the east. The cause of the insurrection was Roman rapacity and cruelty. A native chief, Prasutagus, in order to secure half of his [Pg 22] property to his family at his death, left it to be equally divided between his daughters and the Emperor; but the governor of the district, under the pretext that his widow Boadicea had concealed part of the property, seized the whole. Boadicea protested. To punish her presumption she was stripped, bound, and scourged as a slave, and her daughters given up to still more brutal and infamous treatment. Maddened by these outrages, Boadicea roused the tribes by her appeals. They fell upon London and other cities, burned them to the ground, and slaughtered many thousand inhabitants. For a time it looked as though the whole country would be restored to the Britons; but Suetonius heard of the disaster, hurried from the north, and fought a final battle, so tradition says, on ground within sight of where St. Paul’s Cathedral now stands. The Roman general gained a complete victory, and Boadicea, the Cleopatra of the North, as she has been called, took her own life, rather than, like the Egyptian queen, fall into the hands of her conquerors. She died, let us trust, as the poet has represented, animated by the prophecy of the Druid priest that,—

51. Christianity introduced into Britain.—Perhaps it was not long after this that Christianity made its way to Britain; if so, it crept in so silently that nothing certain can be learned of its advent. Our only record concerning it is found in monkish chronicles filled with bushels of legendary chaff, from which a few grains of historic truth may be here and there picked out. The first church, it is said, was built at Glastonbury.[24] It was a long, shed-like structure of wicker-work. “Here,” says Fuller, “the converts watched, fasted, preached, and prayed, having high meditations under a low roof and large hearts within narrow walls.” [Pg 23] Later there may have been more substantial edifices erected at Canterbury by the British Christians, but at what date, it is impossible to say. At first, no notice was taken of the new religion. It was the faith of the poor and the obscure, hence the Roman generals regarded it with contempt; but as it continued to spread, it caused alarm. The Roman Emperor was not only the head of the state, but the head of religion as well. He represented the power of God on earth: to him every knee must bow; but the Christian refused this homage. He put Christ first; for that reason he was dangerous to the state: if he was not already a traitor and rebel, he was suspected to be on the verge of becoming both.

52. Persecution of British Christians; St. Alban.—Toward the last of the third century the Roman Emperor Diocletian resolved to root out this pernicious belief. He began a course of systematic persecution which extended to every part of the Empire, including Britain. The first martyr was Alban. He refused to sacrifice to the Roman deities, and was beheaded. “But he who gave the wicked stroke,” says Bede,[25] with childlike simplicity, “was not permitted to rejoice over the deed, for his eyes dropped out upon the ground together with the blessed martyr’s head.” Five hundred years later the abbey of St. Albans[26] rose on the spot to commemorate him who had fallen there, and on his account that abbey stood superior to all others in power and privilege.

53. Agricola explores the Coast and builds a Line of Forts.—In 78 A.D. Agricola, a wise and equitable ruler, became governor of the country. His fleets explored the coast, and first discovered Britain to be an island. He gradually extended the limits of the government, and, in order to prevent invasion from the north, he built a line of forts across Caledonia, or Scotland, from the river Firth to the Clyde.

54. The Romans clear and cultivate the Country.—From this date the power of Rome was finally fixed. During the period of [Pg 24] three hundred years which follows, the entire surface of the country underwent a great change. Forests were cleared, marshes drained, waste lands reclaimed, rivers banked in and bridged, and the soil made so productive that Britain became known in Rome as the most important grain-producing and grain-exporting province in the Empire.

55. Roman Cities; York.—Where the Britons had had a humble village enclosed by a ditch, with felled trees, to protect it, there rose such walled towns as Chester, Lincoln, London, and York, with some two score more, most of which have continued to be centres of population ever since. Of these, London early became the commercial metropolis, while York was acknowledged to be both the military and civil capital of the country. There the Sixth Legion was stationed. It was the most noted body of troops in the Roman army, and was called the “Victorious Legion.” It remained there for upward of three hundred years. There, too, the governor resided and administered justice. For these reasons York got the name of “another Rome.” It was defended by walls flanked with towers, some of which are still standing. It had numerous temples and public buildings, such as befitted the first city of Britain. There, also, an event occurred in the fourth century which made an indelible mark on the history of mankind. For at York, Constantine, the subsequent founder of Constantinople, was proclaimed emperor, and through his influence Christianity became the established religion of the Empire.[27]

56. Roman System of Government; Roads.—During the Roman possession of Britain the country was differently governed at different periods, but eventually it was divided into five provinces. These were intersected by a magnificent system of paved roads running in direct lines from city to city, and having London as a common centre. Across the Strait of Dover, they connected with a similar system of roads throughout France, [Pg 25] Spain, and Italy, which terminated at Rome. Over these roads bodies of troops could be rapidly marched to any needed point, and by them officers of state mounted on relays of fleet horses could pass from one end of the Empire to the other in a few days’ time. So skilfully and substantially were these highways constructed, that modern engineers have been glad to adopt them as a basis for their work, and the four leading Roman roads[28] continue to be the foundation, not only of numerous turnpikes in different parts of England, but also of several of the great railway lines, especially those from London to Chester and from London to York.

57. Roman Forts and Walls.—Next in importance to the roads were the fortifications. In addition to those which Agricola had built, later rulers constructed a wall of solid masonry entirely across the country from the shore of the North to that of the Irish Sea. This wall, which was about seventy-five miles south of Agricola’s work, was strengthened by a deep ditch and a rampart of earth. It was further defended by castles built at regular intervals of one mile. These were of stone, and from sixty to seventy feet square. Between them were stone turrets or watch-towers which were used as sentry-boxes; while at every fourth mile there was a fort, covering from three to six acres, occupied by a large body of troops.

58. Defences against Saxon Pirates.—But the northern tribes were not the only ones to be guarded against; bands of pirates prowled along the east and south coasts, burning, plundering, and kidnapping. These marauders came from Denmark and the adjacent countries. The Britons and Romans called them Saxons, a most significant name if, as is generally supposed, it refers to the short, stout knives which made them a terror to every land on which they set foot. To repel them a strong chain of forts was erected on the coast, extending from the mouth of the river Blackwater, in Essex, to Portsmouth on the south.

[Pg 26] Of these great works, cities, walls, and fortifications, though by far the greater part have perished, yet enough still remain to justify the statement that “outside of England no such monuments exist of the power and military genius of Rome.”

59. Roman Civilization False.—Yet the whole fabric was as hollow and false as it was splendid. Civilization, like truth, cannot be forced on minds unwilling or unable to receive it. Least of all can it be forced by the sword’s point and the taskmaster’s lash. In order to render his victories on the continent secure, Cæsar had not hesitated to butcher thousands of prisoners of war or to cut off the right hands of the entire population of a large settlement to prevent them from rising in revolt. The policy pursued in Britain, though very different, was equally heartless and equally fatal. There was indeed an occasional ruler who endeavored to act justly, but such cases were rare. Galgacus, a leader of the North Britons, said with truth of the Romans, “They give the lying name of Empire to robbery and slaughter; they make a desert and call it peace.”

60. The Mass of the Native Population Slaves.—It is true that the chief cities of Britain were exempt from oppression. They elected their own magistrates and made their own laws, but they enjoyed this liberty because their inhabitants were either Roman soldiers or their allies. Outside these cities the great mass of the native population were bound to the soil, while a large proportion of them were absolute slaves. Their work was in the brick fields, the quarries, the mines, or in the ploughed land, or the forest. Their homes were wretched cabins plastered with mud, thatched with straw, and built on the estates of masters who paid no wages.

61. Roman Villas.—The masters lived in stately villas adorned with pavements of different colored marbles and beautifully painted walls. These country-houses, often as large as palaces, were warmed in winter, like our modern dwellings, with currents of heated air, while in summer they opened on terraces ornamented [Pg 27] with vases and statuary, and on spacious gardens of fruits and flowers.[29]

62. Roman Taxation and Cruelty.—Such was the condition of the laboring classes. Those who were called free were hardly better off, for nearly all that they could earn was swallowed up in taxes. The standing army of Britain, which the people of the country had to support, rarely numbered less than forty thousand. The population was not only scanty, but it was poor. Every farmer had to pay a third of all that his farm could produce, in taxes. Every article that he sold had also to pay duty, and finally there was a poll-tax on the man himself. On the continent there was a saying that it was better for a property-owner to fall into the hands of savages than into those of the Roman assessors. When they went round, they counted not only every ox and sheep, but every plant, and registered them as well as the owners. “One heard nothing,” says a writer of that time, speaking of the days when revenue was collected, “but the sound of flogging and all kinds of torture. The son was compelled to inform against his father, and the wife against her husband. If other means failed, men were forced to give evidence against themselves and were assessed according to the confession they made to escape torment.”[30] So great was the misery of the land that it was not an uncommon thing for parents to destroy their children, rather than let them grow up to a life of suffering. This vast system of organized oppression, like all tyranny, “was not so much an institution as a destitution,” undermining and impoverishing the country. It lasted until time brought its revenge, and Rome, which had crushed so many nations of barbarians, was in her turn threatened with a like fate, by bands of barbarians stronger than herself.

63. The Romans compelled to abandon Britain.—When Cæsar returned from his victorious campaigns in Gaul in the first [Pg 28] century B.C., Cicero exultingly exclaimed, “Now, let the Alps sink! the gods raised them to shelter Italy from the barbarians; they are no longer needed.” For nearly five centuries that continued true; then the tribes of Northern Europe could no longer be held back. When the Roman emperors saw that the crisis had arrived, they recalled the legions from Britain. The rest of the colonists soon followed. In the year 409 we find this brief but expressive entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,[31] “After this the Romans never ruled in Britain.” A few years later this entry occurs: “418. This year the Romans collected all the treasures in Britain; some they hid in the earth, so that no one since has been able to find them, and some they carried with them into Gaul.”

64. Remains of Roman Civilization.—In the course of the next three generations whatever Roman civilization had accomplished in the island, politically and socially, had disappeared. A few words, indeed, such as “port” and “street,” have come down to us. Save these, nothing is left but the material shell,—the roads, forts, arches, gateways, altars, and tombs, which are still to be seen scattered throughout the land.

The soil, also, is full of relics of the same kind. Twenty feet below the surface of the London of to-day lie the remains of the London of the Romans. In digging in the “city,”[32] the laborer’s shovel every now and then brings to light bits of rusted armor, broken swords, fragments of statuary, and gold and silver ornaments. So, likewise, several towns, long buried in the earth, and the foundations of upwards of a hundred country-houses, have been discovered; but these seem to be all. If Rome left any traces [Pg 29] of her literature, law, and methods of government, they are so doubtful that they serve only as subjects for antiquarians to wrangle over.[33] Were it not for the stubborn endurance of ivy-covered ruins like those of Pevensey, Chester, and York, and of that gigantic wall which still stretches across the bleak moors of Northumberland, we might well doubt whether there ever was a time when the Cæsars held Britain in their relentless grasp.

65. Good Results of the Roman Conquest of Britain.—Still, it would be an error to suppose that the conquest and occupation of the island had no results for good. Had Rome fallen a century earlier, the world would have been the loser by it, for during that century the inhabitants of Gaul and Spain were brought into closer contact than ever with the only power then existing which could teach them the lesson they were prepared to learn. Unlike the Britons, they adopted the Latin language for their own; they made themselves acquainted with its literature and aided in its preservation; they accepted the Roman law and the Roman idea of government; lastly, they acknowledged the influence of the Christian church, and, with Constantine’s help, they organized it on a solid foundation. Had Rome fallen a prey to the invaders in 318 instead of 410,[34] it is doubtful if any of these results would have taken place, and it is almost certain that the last and most important of all could not.

Britain furnished Rome with abundant food supplies, and sent thousands of troops to serve in the Roman armies on the continent. Britain also supported the numerous colonies which were constantly emigrating to her from Italy, and thus kept open the lines of communication with the mother-country. By so doing she helped to maintain the circulation of the life-currents in the remotest branches of the Roman Empire. Because of this, that [Pg 30] empire was able to resist the barbarians until the seeds of the old civilization had time to root themselves and to spring up with promise of a new and nobler growth. In itself, then, though the island gained practically nothing from the Roman occupation, yet through it mankind was destined to gain much. During these centuries the story of Britain is that which history so often repeats—a part of Europe was sacrificed that the whole might not be lost.

“The happy ages of history are never the productive ones.”—Hegel.

THE COMING OF THE SAXONS, OR ENGLISH, 449 A.D.

THE BATTLES OF THE TRIBES.—BRITAIN BECOMES ENGLAND.

[Pg 31] 66. Condition of the Britons after the Romans left the Island.—Three hundred and fifty years of Roman law and order had so completely tamed the fiery aborigines of the island that when the legions abandoned it, the complaint of Gildas,[35] “the British Jeremiah,” as Gibbon calls him, may have been literally true, when he declared that the Britons were no longer brave in war or faithful in peace.

Certainly their condition was both precarious and perilous. On the north they were assailed by the Picts, on the northwest by the Scots,[36] on the south and east by the Saxons. What was perhaps worst and most dangerous of all, they quarrelled among themselves over points of theological doctrine. They had, indeed, the love of liberty, but not the spirit of unity; and the consequence was, that their enemies, bursting in on all sides, cut them down, Bede says, as “reapers cut down ripe grain.”

67. Letter to Aëtius.—At length the chief men of the country joined in a piteous and pusillanimous letter begging help from [Pg 32] Rome. It was addressed as follows: “To Aëtius, Consul[37] for the third time, the groans of the Britons”; and at the close their calamities were summed up in these words, “The barbarians drive us to the sea, the sea drives us back to the barbarians; between them we are either slain or drowned.” Aëtius, however, was fighting the enemies of Rome at home, and left the Britons to shift for themselves.

68. Vortigern’s Advice.—Finally, in their desperation, they adopted the advice of Vortigern, a chief of Kent, who urged them to fight fire with fire, by inviting a band of Saxons to form an alliance with them against the Picts and Scots. The proposal was very readily accepted by a tribe of Jutes. They, with the Angles and Saxons, occupied the peninsula of Jutland, or Denmark, and the seacoast to the south of it. All of them were known to the Britons under the general name of Saxons.

69. Coming of the Jutes.—Gildas records their arrival in characteristic terms, saying that “in 449 a multitude of whelps came from the lair of the barbaric lioness, in three keels, as they call them.”[38] We get a good picture of what they were like from the exultant song of their countryman, Beowulf,[39] who describes with pride “the dragon-prowed ships,” filled with sea-robbers, armed with “rough-handled spears and swords of bronze,” which under other leaders sailed for the shining coasts of Britain.

These three keels, or war-ships, under the command of the chieftains Hengist and Horsa, were destined to grow into a kingdom. Settling at first, according to agreement, in the island of [Pg 33] Thanet, near the mouth of the Thames, the Jutes easily fulfilled their contract to free the country from the ravages of the Picts, and quite as easily found a pretext afterward for seizing the fairest portion of Kent for themselves and their kinsmen and adherents, who came, vulture-like, in ever-increasing multitudes.

70. Invasion by the Saxons.—The success of the Jutes incited their neighbors, the Saxons, who came under the leadership of Ella, and Cissa, his son, for their share of the spoils. They conquered a part of the country bordering on the Channel, and, settling there, gave it the name of Sussex, or the country of the South Saxons. We learn from two sources how the land was wrested from the native inhabitants. On the one side is the account given by the British monk Gildas; on the other, that of the Saxon or English Chronicle. Both agree that it was gained by the edge of the sword, with burning, pillaging, massacre, and captivity. “Some,” says Gildas, “were caught in the hills and slaughtered; others, worn out with hunger, gave themselves up to lifelong slavery. Some fled across the sea; others trusted themselves to the clefts of the mountains, to the forests, and to the rocks along the coast.” By the Saxons, we are told that the Britons fled before them “as from fire.”

71. Siege of Anderida.—Again, the Chronicle tersely says: “In 490 Ella and Cissa besieged Anderida (the modern Pevensey)[40] and put to death all who dwelt there, so that not a single Briton remained alive in it.” When, however, they took a fortified town like Anderida, they did not occupy, but abandoned it. So the place stands to-day, with the exception of a Norman castle, built there in the eleventh century, just as the invaders left it. Accustomed as they were to a wild life, they hated the restraint and scorned the protection of stone walls. It was not until after many generations had passed that they became reconciled to live within them. In the same spirit, they refused to appropriate [Pg 34] anything which Rome had left. They burned the villas, killed or enslaved the serfs who tilled the soil, and seized the land to form rough settlements of their own.

72. Settlement of Wessex, Essex, and Middlesex.—In this way, after Sussex was established, bands came over under Cerdic in 495. They conquered a territory to which they gave the name of Wessex, or the country of the West Saxons. About the same time, or possibly a little later, we have the settlement of other invaders in the country north of the Thames, which became known as Essex and Middlesex, or the land of the East and the Middle Saxons.

73. Invasion by the Angles.—Finally, there came from a little corner south of the peninsula of Denmark, between the Baltic and an arm of the sea called the Sley (a region which still bears the name of Angeln), a tribe of Angles, who took possession of all of Eastern Britain not already appropriated. Eventually they came to have control over the greater part of the land, and from them all the other tribes took the name of Angles, or English.

74. Bravery of the Britons.—Long before this last settlement was complete, the Britons had plucked up courage, and had, to some extent, joined forces to save themselves from utter extermination. They were naturally a brave people, and the fact that the Saxon invasions cover a period of more than a hundred years shows pretty conclusively that, though the Britons were weakened by Roman tyranny, yet in the end they fell back on what pugilists call their “second strength.” They fought valiantly and gave up the country inch by inch only.

75. King Arthur checks the Invaders.—In 520, if we may trust tradition, the Saxons received their first decided check at Badbury, in Dorsetshire, from that famous Arthur, the legend of whose deeds has come down to us, retold in Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King.” He met them in their march of insolent triumph, [Pg 35] and with his irresistible sword “Excalibur” and his stanch Welsh spearsmen, proved to them, at least, that he was not a myth, but a man,[41] able “to break the heathen and uphold the Christ.”

76. The Britons driven into the West.—But though temporarily brought to a stand, the heathen were neither to be expelled nor driven back. They had come to stay. At last the Britons were forced to take refuge among the hills of Wales, where they continued to abide unconquered and unconquerable by force alone. In the light of these events, it is interesting to see that that ancient stock never lost its love of liberty, and that more than eleven centuries later, Thomas Jefferson, and several of the other fifty-five signers of the Declaration of American Independence were either of Welsh birth or of direct Welsh descent.

77. Gregory and the English Slaves.—The next period, of nearly eighty years, until the coming of Augustine, is a dreary record of constant bloodshed. Out of their very barbarism, however, a regenerating influence was to arise. In their greed for gain, some of the English tribes did not hesitate to sell their own children into bondage. A number of these slaves exposed in the Roman forum, attracted the attention, as he was passing, of a monk named Gregory. Struck with the beauty of their clear, ruddy complexions and fair hair, he inquired from what country they came. “They are Angles,” was the dealer’s answer. “No, not Angles, but angels,” answered the monk, and he resolved that, should he ever have the power, he would send missionaries to convert a race of so much promise.[42]

78. Coming of Augustine, 597.—In 590 he became the head of the Roman church. Seven years later he fulfilled his resolution, and sent Augustine with a band of forty monks to Britain. They landed on the very spot where Hengist and Horsa had disembarked [Pg 36] nearly one hundred and fifty years before. Like Cæsar and his legions, they brought with them the power of Rome; but this time it came not as a force from without to crush men in the iron mould of submission and uniformity, but as a persuasive voice to arouse and cheer them with new hope. Providence had already prepared the way. Ethelbert, king of Kent, had married Bertha, a French princess, who in her own country had become a convert to Christianity. The Saxons, or English, at that time were wholly pagan, and had, in all probability, destroyed every vestige of the faith for which the British martyrs gave their lives.

79. Augustine converts the King of Kent and his People.—Through the queen’s influence, Ethelbert was induced to receive Augustine. He was afraid, however, of some magical practice, so he insisted that their meeting should take place in the open air and on the island of Thanet. The historian Bede represents the monks as advancing to salute the king, holding a tall silver cross in their hands and a picture of Christ painted on an upright board. Augustine delivered his message, was well received, and invited to Canterbury, the capital of Kent. There the king became a convert to his preaching, and before the year had passed ten thousand of his subjects had received baptism; for to gain the king was to gain his tribe as well.

80. Augustine builds the First Monastery.—At Canterbury Augustine became the first archbishop over the first cathedral. There, too, he erected the first monastery in which to train missionaries to carry on the work which he had begun, a building still in use for that purpose, and that continues to bear the name of the man who founded it. The example of the ruler of Kent was not without its effect on others.

81. Conversion of the North.—The North of England, however, owed its conversion chiefly to the Irish monks of an earlier age. They had planted monasteries in Ireland and Scotland from which colonies went forth, one of which settled at Lindisfarne, in Durham. Cuthbert, a Saxon monk of that monastery in the [Pg 37] seventh century, travelled as a missionary throughout Northumbria, and was afterward recognized as the saint of the North. Through his influence that kingdom was induced to accept Christianity. Others, too, went to other districts. In one case, an aged chief arose in an assembly of warriors and said, “O king, as a bird flies through this hall in the winter night, coming out of the darkness and vanishing into it again, even such is our life. If these strangers can tell us aught of what is beyond, let us give heed to them.” But Bede informs us that, notwithstanding their success, some of the new converts were too cautious to commit themselves entirely to the strange religion. One king, who had set up a large altar devoted to the worship of Christ, very prudently set up a smaller one at the other end of the hall to the old heathen deities, in order that he might make sure of the favor of both.

82. Christianity organized; Labors of the Monks.—Gradually, however, the pagan faith was dropped. Christianity organized itself under conventual rule. Monasteries either already existed or were now established at Lindisfarne,[43] Wearmouth, Whitby and Jarrow in the north, and at Peterborough and St. Albans in the east. These monasteries were educational as well as industrial centres. Part of each day was spent by the monks in manual toil, for they held that “to labor is to pray.” They cleared the land, drained the bogs, ploughed, sowed, and reaped. Another part of the day they spent in religious exercises, and a third in writing, translating, and teaching. A school was attached to each monastery, and each had besides its library of manuscript books as well as its room for the entertainment of travellers and pilgrims. In these libraries important charters and laws relating to the kingdom were also preserved.

83. Literary Work of the Monks.—It was at Jarrow that Bede wrote in rude Latin the church-history of England. It was at [Pg 38] Whitby that the poet Cædmon[44] composed his poem on the Creation, in which, a thousand years before Milton, he dealt with Milton’s theme in Milton’s spirit. It was at Peterborough and Canterbury that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was probably begun, a work which stands by itself, not only as the first English history, but the first English book, and the one from which we derive much of our knowledge of the time from the Roman conquest down to a period after the coming of the Normans. It was in the abbeys of Malmesbury[45] and St. Albans that, at a later period, that history was taken up and continued by William of Malmesbury and Matthew Paris. It was also from these monasteries that an influence went out which eventually revived learning throughout Europe.

84. Influence of Christianity on Society.—But the work of Christianity for good did not stop with these things. The church had an important social influence. It took the side of the weak, the suffering, and the oppressed. It shielded the slave from ill usage. It secured for him Sunday as a day of rest, and it constantly labored for his emancipation.

85. Political Influence of Christianity.—More than this, Christianity had a powerful political influence. In 664 a synod, or council, was held at Whitby to decide when Easter should be observed. To that meeting, which was presided over by the Archbishop of Canterbury, delegates were sent from all parts of the country. After a protracted debate the synod decided in favor of the Roman custom, and thus all the churches were brought into agreement. In this way, at a period when the country was divided into hostile kingdoms of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, each struggling fiercely for the mastery, there was a spirit of true religious unity growing up. The bishops, monks, and priests, gathered at Whitby, were from tribes at open war with each other. But in that, and other conferences which followed, they felt that they had a common interest, that they were fellow-countrymen, [Pg 39] and that they were all members of the same church and laboring for the same end.

86. Egbert.—But during the next hundred and fifty years the chief indication outside the church of any progress toward consolidation was in the growing power of the kingdom of Wessex. In 787 Egbert, a direct descendant of Cerdic, the first chief and king of the country, laid claim to the throne. Another claimant arose, who gained the day, and Egbert, finding that his life was in danger, fled the country.

87. Egbert at the Court of Charlemagne.—He escaped to France, and there took refuge at the court of King Charlemagne, where he remained thirteen years. Charlemagne had conceived the gigantic project of resuscitating the Roman Empire. To accomplish that, he had engaged in a series of wars, and in the year 800 had so far conquered his enemies that he was crowned Emperor of the West by the Pope at Rome.

88. Egbert becomes “King of the English.”—That very year the king of Wessex died, and Egbert was summoned to take his place. He went back impressed with the success of the French king and ambitious to imitate him. Twenty-three years after that, we hear of him fighting the tribes in Mercia, or Central Britain. His army is described as “lean, pale, and long-breathed”; but with those cadaverous troops he conquered and reduced the Mercians to subjection. Other victories followed, and in 828 he had brought all the sovereignties of England into vassalage. He now ventured to assume the title, which he had fairly won, of “King of the English.”[46]

89. Britain becomes England.—The Celts had called the land Albion; the Romans, Britain:[47] the country now called itself Angle-Land, or England. Three causes had brought about this consolidation, [Pg 40] to which each people had contributed part. The Jutes of Kent encouraged the foundation of the national church; the Angles gave the national name, the West Saxons furnished the national king. From him as a royal source, every subsequent English sovereign, with the exception of Harold II., and a few Danish rulers, has directly or indirectly descended down to the present time.

90. Alfred the Great.—Of these the most conspicuous during the period of which we are writing was Alfred, grandson of Egbert. He was rightly called Alfred the Great, since he was the embodiment of whatever was best and bravest in the English character. The key-note of his life may be found in the words which he spoke at the close of it, “So long as I have lived, I have striven to live worthily.”

91. Danish Invasion.—When he came to the throne in 871, through the death of his brother Ethelred, the Danes were sweeping down on the country. A few months before that event Alfred had aided his brother in a desperate struggle with them. In the beginning, the object of the Danes was to plunder, later, to possess, and finally, to rule over the country. In the year Alfred came to the throne, they had already overrun a large portion and invaded Wessex. Wherever their raven-flag appeared, there destruction and slaughter followed.

92. The Danes destroy the Monasteries.—The monasteries were the especial objects of their attacks. Since their establishment many of them had accumulated wealth and had sunk into habits of idleness and luxury. The Danes, without intending it, came to scourge these vices. From the thorough way in which they robbed, burned, and murdered, there can be no doubt that they enjoyed what some might think was their providential mission. In their helplessness and terror, the panic-stricken monks added to their usual prayers, this fervent petition: “From the fury of the Northmen, good Lord deliver us!” The power raised up to answer that supplication was Alfred.

[Pg 41] 93. Alfred’s Victories over the Danes; The White Horse.—After repeated defeats, he, with his brother, finally drove back these savage hordes, who thought it a shame to earn by sweat what they could win by blood; whose boast was that they would fight in paradise even as they had fought on earth, and would celebrate their victories with foaming draughts of ale drunk from the skulls of their enemies. In these attacks, Alfred led one-half the army, Ethelred the other. They met the Danes at Ashdown, in Berkshire. While Ethelred stopped to pray for success, Alfred, under the banner of the “White Horse,”—the common standard of the Anglo-Saxons at that time,—began the attack and won the day. Tradition declares that after the victory he ordered his army to commemorate their triumph by carving that colossal figure of a horse on the side of a neighboring chalk-hill, which still remains so conspicuous an object in the landscape. It was shortly after this that Alfred became king; but the war, far from being ended, had in fact but just begun.

94. The Danes compel Alfred to retreat.—The Danes, reinforced by other invaders, overcame Alfred’s forces and compelled him to retreat. He fled to the wilds of Somersetshire, and was glad to take up his abode for a time, so the story runs, in a peasant’s hut. Subsequently he succeeded in rallying part of his people, and built a stronghold on a piece of rising ground, in the midst of an almost impassable morass. There he remained during the winter.

95. Great Victory by Alfred; Treaty of Wedmore, 878.—In the spring he marched forth and again attacked the Danes. They were entrenched in a camp at Edington, Wiltshire. Alfred surrounded them, and starved them into submission so complete that Guthrum, the Danish leader, swore a peace, called the Peace or Treaty of Wedmore, and sealed the oath with his baptism—an admission that Alfred had not only beaten, but converted him as well.

[Pg 42] 96. Terms of the Treaty.—By the Treaty of Wedmore[48] the Danes bound themselves to remain north and east of a line drawn from London to Chester, following the old Roman road called Watling-street. All south of this line, including a district around London, was recognized as the dominions of Alfred, whose chief city, or capital, was Winchester. By this treaty the Danes got much the larger part of England, on the one hand, though they acknowledged Alfred as their over-lord, on the other. He thus became nominally what his predecessor, Egbert, had claimed to be,—the king of the whole country.[49]

97. Alfred’s Laws; his Translations.—He proved himself to be more than mere ruler; for he was law-giver and teacher as well. Through his efforts a written code was compiled, prefaced by the Ten Commandments and ending with the Golden Rule; and, as Alfred added, referring to the introduction, “He who keeps this shall not need any other law-book.” Next, that learning might not utterly perish in the ashes of the abbeys and monasteries which the Danes had destroyed, the king, though feeble and suffering, set himself to translate from the Latin the Universal History of Orosius, and also Bede’s History of England. He afterward rendered into English the Reflections of the Roman senator, Boethius, on the Supreme Good, an inquiry written by the latter while in prison, under sentence of death.

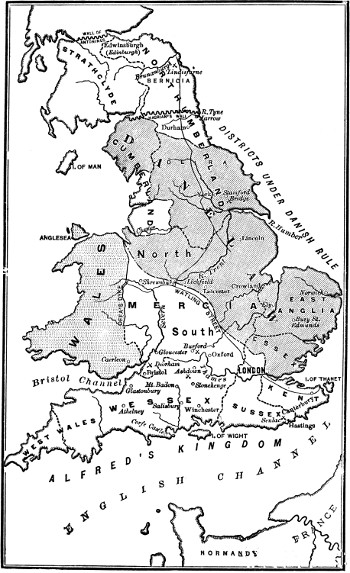

ENGLAND TOWARD THE CLOSE OF THE NINTH CENTURY.

ENGLAND TOWARD THE CLOSE OF THE NINTH CENTURY.The shaded district on the northeast shows the part obtained by the Danes by the Treaty of Wedmore, 878 A.D.

98. Alfred’s Navy.—Alfred, however, still had to combat the Danes, who continued to make descents upon the coast, and even sailed up the Thames to take London. He constructed a superior class of fast-sailing war-vessels from designs made by himself, and with this fleet, which may be regarded as the beginning of the English navy, he fought the enemy on their own element. He thus effectually checked a series of invasions which, had they continued, might have eventually reduced the country to primitive barbarism.

[Pg 43] 99. Estimate of Alfred’s Reign.—Considered as a whole, Alfred’s reign is the most noteworthy of any in the annals of the early English sovereigns. It was marked throughout by intelligence and progress. His life speaks for itself. The best commentary on it is the fact that, in 1849, the people of Wantage,[50] his native place, celebrated the thousandth anniversary of his birth—another proof that “what is excellent, as God lives, is permanent.”[51]

100. Dunstan’s Reforms.—Two generations after Alfred’s death, Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, the ablest man in an age when all statesmen were ecclesiastics, came forward to take up and push onward the work begun by the great king. He labored for higher education, for strict monastic rule, and for the celibacy of the monks.

101. Regular and Secular Clergy.—At that time the clergy of England were divided into two classes,—the “regulars,” or monks, and the “seculars,” or parish priests and other clergy not bound by monastic vows. The former lived in the monasteries apart from the world; the latter lived in it. By their monastic vows,[52] the “regulars” were bound to remain unmarried, while the “seculars” were not. Notwithstanding Alfred’s efforts at reform, many monasteries had relaxed their rules, and were again filled with drones. In violation of their vows, large numbers of the monks were married. Furthermore, many new churches had been endowed and put into the hands of the “seculars.”

102. Danger to the State from Each Class of Clergy.—The danger was that this laxity would go on increasing, so that in time the married clergy would monopolize the clerical influence and clerical wealth of the kingdom for themselves and their families. They would thus become an hereditary body, a close corporation, transmitting their power and possessions from father to son through generations. On the other hand, the tendency of the unmarried [Pg 44] clergy would be to become wholly subservient to the church and the Pope, though they must necessarily recruit their ranks from the people. In this last respect they would be more democratic than the opposite class. They would also be more directly connected with national interests and the national life, while at the same time they would be able to devote themselves more exclusively to study and to intellectual culture than the “seculars.”

103. Dunstan as a Statesman and Artisan.—In addition to these reforms, Dunstan proved himself to be as clever a statesman as theologian. He undertook, with temporary success, to reconcile the conflicting interests of the Danes and the English. He was also noted as a mechanic and worker in metals. The common people regarded his accomplishments in this direction with superstitious awe. Many stories of his skill were circulated, and it was even whispered that in a personal contest with Beelzebub, it was the devil and not the monk who got the worst of it and fled from the saint’s workshop, howling with dismay.

104. New Invasions; Danegeld.—With the close of Dunstan’s career, the period of decline sets in. Fresh inroads began on the part of the Northmen,[53] and so feeble and faint-hearted grew the resistance that at last a royal tax, called Danegeld, or Dane-money, was levied on all landed property in order to raise means to buy off the invaders. For a brief period this cowardly concession answered the purpose. But a time came when the Danes would no longer be bribed to keep away.

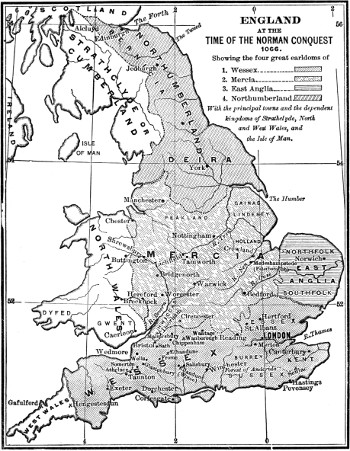

ENGLAND AT THE TIME OF THE NORMAN CONQUEST 1066.

ENGLAND AT THE TIME OF THE NORMAN CONQUEST 1066.Showing the four great earldoms of

1. Wessex

2. Mercia

3. East Anglia

4. Northumberland

With the principal towns and the dependent kingdoms of Strathclyde, North

and West Wales, and the Isle of Man.