* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Father and Daughter

Date of first publication: 1824

Author: Amelia Alderson Opie (1769-1853)

Date first posted: November 23 2012

Date last updated: November 23 2012

Faded Page eBook #20121141

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Mary Meehan & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

NINTH EDITION.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR

LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, BROWN, & GREEN,

PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1824.

Printed by Richard Taylor,

Shoe Lane, London.

TO

Dr. ALDERSON of NORWICH.

DEAR SIR,

In dedicating this Publication to you, I follow in some measure the example of those nations who devoted to their gods the first fruits of the genial seasons which they derived from their bounty.

To you I owe whatever of cultivation my mind has received; and the first fruits of that mind to you I dedicate.

Besides, having endeavoured in "The Father and Daughter" to exhibit a picture of the most perfect parental affection, to whom could I dedicate it with so much propriety as to you, since, in describing a good father, I had only to delineate my own?

Allow me to add, full of gratitude for years of tenderness and indulgence on your part, but feebly repaid even by every possible sentiment of filial regard on mine, that the satisfaction I shall experience if my Publication be favourably received by the world, will not proceed from the mere gratification of my self-love, but from the conviction I shall feel that my success as an Author is productive of pleasure to you.

AMELIA OPIE.

Berners Street,

1800.

It is not without considerable apprehension that I offer myself as an avowed Author at the bar of public opinion,—and that apprehension is heightened by its being the general custom to give indiscriminately the name of Novel to every thing in Prose that comes in the shape of a Story, however simple it be in its construction, and humble in its pretensions.

By this means, the following Publication is in danger of being tried by a standard according to which it was never intended to be made, and to be criticized for wanting those merits which it was never meant to possess.

I therefore beg leave to say, in justice to myself, that I know "The Father and Daughter" is wholly devoid of those attempts at strong character, comic situation, bustle, and variety of incident, which constitute a Novel, and that its highest pretensions are, to be a simple, moral Tale.

The night was dark,—the wind blew keenly over the frozen and rugged heath, when Agnes, pressing her moaning child to her bosom, was travelling on foot to her father's habitation.

"Would to God I had never left it!" she exclaimed, as home and all its enjoyments rose in fancy to her view:—and I think my readers will be ready to join in the exclamation, when they hear the poor wanderer's history.

Agnes Fitzhenry was the only child of a respectable merchant in a country town, who, having lost his wife when his daughter was very young, resolved for her sake to form no second connection. To the steady, manly affection of a father, Fitzhenry joined the fond anxieties and endearing attentions of a mother; and his parental care was amply repaid by the love and amiable qualities of Agnes. He was not rich; yet the profits of his trade were such as to enable him to bestow every possible expense on his daughter's education, and to lay up a considerable sum yearly for her future support: whatever else he could spare from his own absolute wants, he expended in procuring comforts and pleasures for her.—"What an excellent father that man is!" was the frequent exclamation among his acquaintance—"And what an excellent child he has! well may he be proud of her!" was as commonly the answer to it.

Nor was this to be wondered at:—Agnes united to extreme beauty of face and person every accomplishment that belongs to her own sex, and a great degree of that strength of mind and capacity for acquiring knowledge supposed to belong exclusively to the other.

For this combination of rare qualities Agnes was admired;—for her sweetness of temper, her willingness to oblige, her seeming unconsciousness of her own merits, and her readiness to commend the merits of others,—for these still rarer qualities, Agnes was beloved: and she seldom formed an acquaintance without at the same time securing a friend.

Her father thought he loved her (and perhaps he was right) as never father loved a child before; and Agnes thought she loved him as child never before loved father.—"I will not marry, but live single for my father's sake," she often said;—but she altered her determination when her heart, hitherto unmoved by the addresses of the other sex, was assailed by an officer in the guards who came to recruit in the town in which she resided.

Clifford, as I shall call him, had not only a fine figure and graceful address, but talents rare and various, and powers of conversation so fascinating, that the woman he had betrayed forgot her wrongs in his presence, and the creditor, who came to dun him for the payment of debts already incurred, went away eager to oblige him by letting him incur still more.

Fatal perversion of uncommon abilities! This man, who might have taught a nation to look up to him as its best pride in prosperity and its best hope in adversity, made no other use of his talents than to betray the unwary of both sexes, the one to shame, the other to pecuniary difficulties; and he whose mind was capacious enough to have imagined schemes to aggrandize his native country, the slave of sordid selfishness, never looked beyond his own temporary and petty benefit, and sat down contented with the achievements of the day, if he had overreached a credulous tradesman, or beguiled an unsuspecting woman.

But, to accomplish even these paltry triumphs, great knowledge of the human heart was necessary,—a power of discovering the prevailing foible in those on whom he had designs, and of converting their imagined security into their real danger. He soon discovered that Agnes, who was rather inclined to doubt her possessing in an uncommon degree the good qualities which she really had, valued herself, with not unusual blindness, on those which she had not. She thought herself endowed with great power to read the characters of those with whom she associated, when she had even not discrimination enough to understand her own: and, while she imagined that it was not in the power of others to deceive her, she was constantly in the habit of deceiving herself.

Clifford was not slow to avail himself of this weakness in his intended victim; and, while he taught her to believe that none of his faults had escaped her observation, with hers he had made himself thoroughly acquainted.—But not content with making her faults subservient to his views, he pressed her virtues also into his service; and her affection for her father, that strong hold, secure in which Agnes would have defied the most violent assaults of temptation, he contrived should be the means of her defeat.

I have been thus minute in detailing the various and seducing powers which Clifford possessed, not because he will be a principal figure in my narrative,—for, on the contrary, the chief characters in it are the Father and Daughter,—but in order to excuse as much as possible the strong attachment which he excited in Agnes.

"Love," says Mrs. Inchbald, whose knowledge of human nature can be equalled only by the humour with which she describes its follies, and the unrivalled pathos with which she exhibits its distresses—"Love, however rated by many as the chief passion of the heart, is but a poor dependent, a retainer on the other passions—admiration, gratitude, respect, esteem, pride in the object; divest the boasted sensation of these, and it is no more than the impression of a twelvemonth, by courtesy, or vulgar error, called love[1]."—And of all these ingredients was the passion of Agnes composed. For the graceful person and manner of Clifford she felt admiration; and her gratitude was excited by her observing that, while he was an object of attention to every one wherever he appeared, his attentions were exclusively directed to herself; and that he who, from his rank and accomplishments, might have laid claim to the hearts even of the brightest daughters of fashion in the gayest scenes of the metropolis, seemed to have no higher ambition than to appear amiable in the eyes of Agnes, the humble toast of an obscure country town. While his superiority of understanding, and brilliancy of talents, called forth her respect, and his apparent virtues her esteem; and when to this high idea of the qualities of the man was added a knowledge of his high birth and great expectations, it is no wonder that she also felt the last-mentioned, and often perhaps the greatest, excitement to love, "pride in the object."

When Clifford began to pay those marked attentions to Agnes, which ought always on due encouragement from the woman to whom they are addressed to be followed by an offer of marriage, he contrived to make himself as much disliked by the father as admired by the daughter: yet his management was so artful, that Fitzhenry could not give a sufficient reason for his dislike; he could only declare its existence; and for the first time in her life Agnes learned to think her father unjust and capricious.

Thus, while Clifford ensured an acceptance of his addresses from Agnes, he at the same time secured a rejection of them from Fitzhenry; and this was the object of his wishes, as he had a decided aversion to marriage, and knew besides that marrying Agnes would disappoint all his ambitious prospects in life, and bring on him the eternal displeasure of his father.

At length, after playing for some time with her hopes and fears, Clifford requested Fitzhenry to sanction with his approbation his addresses to his daughter; and Fitzhenry, as he expected, coldly and firmly declined the honour of his alliance. But when Clifford mentioned, as if unguardedly, that he hoped to prevail on his father to approve the marriage after it had taken place, if not before, Fitzhenry proudly told him that he thought his daughter much too good to be smuggled into the family of any one; while Clifford, piqued in his turn at the warmth of Fitzhenry's expressions, and the dignity of his manner, left him, exulting secretly in the consciousness that he had his revenge,—for he knew that the heart of Agnes was irrecoverably his.

Agnes heard from her lover that his suit was rejected, with agonies as violent as he appeared to feel.—"What!" exclaimed she, "can that affectionate father, who has till now anticipated my wishes, disappoint me in the wish nearest to my heart?" In the midst of her first agitation her father entered the room, and, with "a countenance more in sorrow than in anger" began to expostulate with her on the impropriety of the connection which she was desirous of forming. He represented to her the very slender income which Clifford possessed; the inconvenience to which an officer's wife is exposed; and the little chance which there is for a man's making a constant and domestic husband who has been brought up in an idle profession, and accustomed to habits of intemperance, expense, and irregularity:——

"But above all," said he, "how is it possible that you could ever condescend to accept the addresses of a man whose father, he himself owns, will never sanction them with his approbation?"

Alas! Agnes could plead no excuse but that she was in love, and she had too much sense to urge such a plea to her father.

"Believe me," he continued, "I speak thus from the most disinterested consideration of your interest; for, painful as the idea of parting with you must be to me, I am certain I should not shrink from the bitter trial, whenever my misery would be your happiness (Here his voice faltered); but, in this case, I am certain that by refusing my consent to your wishes I ensure your future comfort; and in a cooler moment you will be of the same opinion."

Agnes shook her head, and turned away in tears.

"Nay, hear me, my child," resumed Fitzhenry, "you know that I am no tyrant; and if, after time and absence have been tried in order to conquer your unhappy passion, it remain unchanged, then, in defiance of my judgement, I will consent to your marriage with Mr. Clifford, provided his father consent likewise:—for, unless he do, I never will:—and if you have not pride and resolution enough to be the guardian of your own dignity, I must guard it for you; but I am sure there will be no need of my interference: and Agnes Fitzhenry would scorn to be clandestinely the wife of any man."

Agnes thought so too,—and Fitzhenry spoke this in so mild and affectionate a manner, and in a tone so expressive of suppressed wretchedness, which the bare idea of parting with her had occasioned him, that, for the moment, she forgot every thing but her father, and the vast debt of love and gratitude which she owed him; and throwing herself into his arms she protested her entire, nay cheerful, acquiescence in his determination.

"Promise me, then," replied Fitzhenry, "that you will never see Mr. Clifford more, if you can avoid it: he has the tongue of Belial, and if——"

Here Agnes indignantly interrupted him with reproaches for supposing her so weak as to be in danger of being seduced into a violation of her duty; and so strong were the terms in which she expressed herself, that her father entreated her pardon for having thought such a promise necessary.

The next day Clifford did not venture to call at the house, but he watched the door till he saw Agnes come out alone. Having then joined her, he obtained from her a full account of the conversation which she had had with Fitzhenry; when, to her great surprise, he drew conclusions from it which she had never imagined possible.

He saw, or pretended to see, in Fitzhenry's rejection of his offers, not merely a dislike of her marrying him, but a design to prevent her marrying at all; and as a design like this was selfish in the last degree, and ought to be frustrated, he thought it would be kinder in her to disobey her father then, and marry the man of her heart, than, by indulging his unreasonable wishes on this subject once, to make him expect that she would do so again, and continue to lead a single life;—because, in that case, the day of her marrying, when it came at last, would burst on him with tenfold horrors.

The result of this specious reasoning, enforced by tears, caresses and protestations, was, that she had better go off to Scotland immediately with him, and trust to time, necessity, and their parents' affection, to secure their forgiveness.

Agnes the first time heard these arguments, and this proposal, with the disdain which they merited; but, alas! she did not resolve to avoid all opportunity of hearing them a second time: but, vain of the resolution she had shown on this first trial, she was not averse to stand another, delighted to find that she had not overrated her strength, when she reproached Fitzhenry for his want of confidence in it.

The consequence is obvious:—again and again she heard Clifford argue in favour of an elopement; and, though she still retained virtue sufficient to withhold her consent, she every day saw fresh reason to believe he argued on good grounds, and to think that that parent whose whole study, till now, had been her gratification, was, in this instance at least, the slave of unwarrantable selfishness.——

At last, finding that neither time, reflection, nor even a temporary absence, had the slightest effect on her attachment, but that it gained new force every day, she owned that nothing but the dread of making her father unhappy withheld her from listening to Clifford's proposal:—'Twas true, she said, pride forbade it; but the woman who could listen to the dictates of pride, knew nothing of love but the name.

This was the moment for Clifford to urge more strongly than ever that the elopement was the most effectual means of securing her father's happiness, as well as her own; till at last her judgement became the dupe of her wishes; and, fancying that she was following the dictates of filial affection, when she was in reality the helpless victim of passion, she yielded to the persuasions of a villain; and set off with him for Scotland.

When Fitzhenry first heard of her flight, he sat for hours absorbed in a sort of dumb anguish, far more eloquent than words. At length he burst into exclamations against her ingratitude for all the love and care that he had bestowed on her; and the next moment he exclaimed with tears of tenderness, "Poor girl! she is not used to commit faults; how miserable she will be when she comes to reflect! and how she will long for my forgiveness! and, O yes! I am sure I shall long as ardently to forgive her!"—Then his arms were folded in fancy round his child, whom he pictured to himself confessing her marriage to him, and upon her knees imploring his pardon.

But day after day came, and no letter from the fugitives, acknowledging their error, and begging his blessing on their union,—for no union had taken place.

When Clifford and Agnes had been conveyed as fast as four horses could carry them one hundred miles towards Gretna-green, and had ordered fresh horses, Clifford started as he looked at his pocket-book, and, with well-dissembled consternation, exclaimed, "What can we do? I have brought the wrong pocket-book, and have not money enough to carry us above a hundred and odd miles further on the North road!"—Agnes was overwhelmed with grief and apprehension at this information, but did not for an instant suspect that the fact was otherwise than as Clifford stated it to be.

As I before observed, Agnes piqued herself on her knowledge of characters, and she judged of them frequently by the rules of physiognomy; she had studied voices too, as well as countenances:—was it possible, then, that Agnes, who had from Clifford's voice and countenance pronounced him all that was ingenuous, honourable, and manly, could suspect him capable of artifice? could she, retracting her pretensions to penetration, believe she had put herself in the power of a designing libertine? No;—vanity and self-love forbade this salutary suspicion to enter her imagination; and, without one scruple, or one reproach, she acceded to the plan which Clifford proposed, as the only one likely to obviate their difficulties, and procure them most speedily an opportunity of solemnizing their marriage.

Deluded Agnes! You might have known that the honourable lover is as fearful to commit the honour of his mistress, even in appearance, as she herself can be; that his care and anxiety to screen her even from the breath of suspicion are ever on the watch; and that therefore, had Clifford's designs been such as virtue would approve, he would have put it out of the power of accident to prevent your immediate marriage, and expose your fair fame to the whisper of calumny.

To London they set forward, and were driven to an hotel in the Adelphi, whence Clifford went out in search of lodgings; and, having met with convenient apartments at the west end of the town, he conducted to them the pensive and already repentant Agnes.—"Under what name and title," said Agnes, "am I to be introduced to the woman of the house?"—"As my intended wife," cried her lover, pressing her to his bosom;—"and in a few days,—though to me they will appear ages,—you will give me a right to call you by that tender name."—"In a few days!" exclaimed Agnes, withdrawing from his embrace; "cannot the marriage take place to-morrow?" "Impossible!" replied Clifford; "you are not of age,—I can't procure a license;—but I have taken these lodgings for a month,—we will have the banns published, and be married at the parish-church."

To this arrangement, against which her delicacy and every feeling revolted, Agnes would fain have objected in the strongest manner: but, unable to urge any reasons for her objection, except such as seemed to imply distrust of her own virtue, she submitted, in mournful silence, to the plan: with a heart then for the first time tortured with a sense of degradation, she took possession of her apartment; and Clifford returned to his hotel, meditating with savage delight on the success of his plans, and on the triumph which, he fancied, awaited him.

Agnes passed the night in sleepless agitation, now forming and now rejecting schemes to obviate the danger which must accrue to her character, if not to her honour, by remaining for a whole month exposed to the seductions of a man whom she had but too fatally convinced of his power over her heart; and the result of her reflections was, that she should insist on his leaving town, and not returning till he came to lead her to the altar. Happy would it have been for Agnes, had she adhered to this resolution; but vanity and self-confidence again interfered:—"What have I to fear?" said Agnes to herself;—"am I so fallen in my own esteem that I dare not expose myself even to a shadow of temptation?—No;—I will not think so meanly of my virtue:—the woman that is afraid of being dishonoured is half overcome already; and I will meet with boldness the trials which I cannot avoid."

O Vanity! thou hast much to answer for!—I am convinced that, were we to trace up to their source all the most painful and degrading events of our lives, we should find most of them to have their origin in the gratified suggestions of vanity.

It is not my intention to follow Agnes through the succession of mortifications, embarrassments, and contending feelings, which preceded her undoing (for, secure as she thought herself in her own strength, and the honour of her lover, she became at last a prey to her seducer); it is sufficient that I explain the circumstances which led to her being in a cold winter's night, houseless and unprotected, a melancholy wanderer towards the house of her father.

Before the expiration of the month, Clifford had triumphed over the virtue of Agnes; and soon after he received orders to join his regiment, as it was going to be sent on immediate service.—"But you will return to me before you embark, in order to make me your wife?" said the half-distracted Agnes; "you will not leave me to shame as well as misery?" Clifford promised every thing she wished; and Agnes tried to lose the pangs of parting, in anticipation of the joy of his return. But on the very day when she expected him, she received a letter from him, saying that he was under sailing orders, and to see her again before the embarkation was impossible.

To do Clifford justice, he in this instance told truth; and, as he really loved Agnes as well as a libertine can love, he felt the agitation and distress which his letter expressed; though, had he returned to her, he had an excuse ready prepared for delaying the marriage.

Words can but ill describe the situation of Agnes on the receipt of this letter.—The return of Clifford was not to be expected for months at least; and perhaps he might never return!—The thought of his danger was madness:—but, when she reflected that she should in all probability be a mother before she became a wife, in a transport of frantic anguish she implored heaven in mercy to put an end to her existence.—"O my dear, injured father!" she exclaimed, "I, who was once your pride, am now your disgrace!—and that child whose first delight it was to look up in your face, and see your eyes beaming with fondness on her, can now never dare to meet their glance again."

But, though Agnes dared not presume to write to her father till she could sign herself the wife of Clifford, she could not exist without making some secret inquiries concerning his health and spirits; and, before he left her, Clifford recommended a trusty messenger to her for the purpose.—The first account which she received was, that Fitzhenry was well; the next, that he was dejected; the three following, that his spirits were growing better,—and the last account was, that he was married.——

"Married!" cried Agnes rushing into her chamber, and shutting the door after her, in a manner sufficiently indicative to the messenger of the anguish she hastened from him to conceal;—"Married!—Clifford abroad,—perhaps at this moment a corpse,—and my father married!—What, then, am I? A wretch forlorn! an outcast from society!—no one to love, no one to protect and cherish me! Great God! wilt thou not pardon me if I seek a refuge from my suffering in the grave?"

Here nature suddenly and powerfully impressed on her recollection that she was about to become a parent; and, falling on her knees, she sobbed out, "What am I, did I ask?—I am a mother, and earth still holds me by a tie too sacred to be broken!"

Then by degrees she became calmer, and rejoiced, fervently rejoiced, in her father's second marriage, though she felt it as too convincing a proof how completely he had thrown her from his affections. She knew that the fear of a second family's diminishing the strong affection which he bore to her was his reason for not marrying again, and now it was plain that he married in hopes of losing his affection for her. Still this information removed a load from her mind, by showing her that Fitzhenry felt himself capable of receiving happiness from other hands than hers; and she resolved, if she heard that he was happy in his change of situation, never to recall to his memory the daughter whom it was so much his interest to forget.

The time of Agnes's confinement now drew near,—a time which fills with apprehension even the wife, who is soothed and supported by the tender attentions of an anxious husband, and the assiduities of affectionate relations and friends, and who knows that the child with which she is about to present them will at once gratify their affections and their pride. What then must have been the sensations of Agnes at a moment so awful and dangerous as this!—Agnes, who had no husband to soothe her by his anxious inquiries, no relations or friends to cheer her drooping soul by the expressions of sympathy, and whose child, instead of being welcomed by an exulting family, must be, perhaps, a stranger even to its nearest relations!

But in proportion to her trials seemed to be Agnes's power of rising superior to them; and, after enduring her sufferings with a degree of fortitude and calmness that astonished the mistress of the house, whom compassion had induced to attend on her, she gave birth to a lovely boy.—From that moment, though she rarely smiled, and never saw any one but her kind landlady, her mind was no longer oppressed by the deep gloom under which she had before laboured; and when she had heard from Clifford, or of her father's being happy, and clasped her babe to her bosom, Agnes might almost be pronounced cheerful.

After she had been six months a mother, Clifford returned; and, in the transport of seeing him safe, Agnes forgot for a moment that she had been anxious and unhappy. Now again was the subject of the marriage resumed; but just as the wedding day was fixed, Clifford was summoned away to attend his expiring father, and Agnes was once more doomed to the tortures of suspense.

After a month's absence Clifford came back, but appeared to labour under a dejection of spirits which he seemed studious to conceal from her. Alarmed and terrified at an appearance so unusual, she demanded an explanation, which the consummate deceiver gave at length, after many entreaties on her part, and feigned reluctance on his. He told her that his father's illness was occasioned by his having been informed that he was privately married to her; that he had sent for him to inquire into the truth of the report; and, being convinced by his solemn assurance that no marriage had taken place, he had commanded him, unless he wished to kill him, to take a solemn oath never to marry Agnes Fitzhenry without his consent.

"And did you take the oath?" cried Agnes, her whole frame trembling with agitation.—"What could I do?" replied he; "my father's life in evident danger if I refused; besides the dreadful certainty that he would put his threats in execution of cursing me with his dying breath;—and, cruel as he is, Agnes, I could not help feeling that he was my father."——"Barbarian!" exclaimed she, "I sacrificed my father to you!—An oath! O God! have you then taken an oath never to be mine?" and, saying this, she fell into a long and deep swoon.

When she recovered, but before she was able to speak, she found Clifford kneeling by her; and, while she was too weak to interrupt him, he convinced her that he did not at all despair of his father's consent to his making her his wife, else, he should have been less willing to give so ready a consent to take the oath imposed on him, even although his father's life depended on it. "Oh! no," replied Agnes, with a bitter smile; "you wrong yourself; you are too good a son to have been capable of hesitating a moment;—there are few children so bad, so very bad as I am!"—and, bursting into an agony of grief, it was long before the affectionate language and tender caresses of Clifford could restore her to tranquillity.

Another six months elapsed, during which time Clifford kept her hopes alive, by telling her that he every day saw fresh signs of his father's relenting in her favour.—At these times she would say, "Lead me to him; let him hear the tale of my wretchedness; let me say to him, For your son's sake I have left the best of fathers, the happiest of homes, and have become an outcast from society!—then would I bid him look at this pale cheek, this emaciated form, proofs of the anguish that is undermining my constitution; and tell him to beware how, by forcing you to withhold from me my right, he made you guilty of murdering the poor deluded wretch, who, till she knew you, never lay down without a father's blessing, nor rose but to be welcomed by his smile!"

Clifford had feeling, but it was of that transient sort which never outlived the disappearance of the object that occasioned it. To these pathetic entreaties he always returned affectionate answers, and was often forced to leave the room in order to avoid being too much softened by them; but, by the time he had reached the end of the street, always alive to the impressions of the present moment, the sight of some new beauty, or some old companion, dried up the starting tear, and restored to him the power of coolly considering how he should continue to deceive his miserable victim.

But the time at length arrived when the mask that hid his villany from her eyes fell off, never to be replaced. As Agnes fully expected to be the wife of Clifford, she was particularly careful to lead a retired life, and not to seem unmindful of her shame by exhibiting herself at places of public amusement. In vain did Clifford paint the charms of the Play, the Opera, and other places of fashionable resort. "Retirement, with books, music, work, and your society," she used to reply, "are better suited to my taste and situation; and never, but as your wife, will I presume to meet the public eye."

Clifford, though he wished to exhibit his lovely conquest to the world, was obliged to submit to her will in this instance. Sometimes, indeed, Agnes was prevailed on to admit to her table those young men of Clifford's acquaintance who were the most distinguished for their talents and decorum of manners; but this was the only departure that he had ever yet prevailed on her to make, from the plan of retirement which she had adopted.

One evening, however, Clifford was so unusually urgent with her to accompany him to Drury-lane to see a favourite tragedy, (alleging, as an additional motive for her obliging him, that he was going to leave her on the following Monday, in order to attend his father into the country, where he should be forced to remain some time,) that Agnes, unwilling to refuse what he called his parting request, at length complied; Clifford having prevailed on Mrs. Askew, her kind landlady, to accompany them, and having assured Agnes, that, as they should sit in the upper boxes, she might, if she chose it, wear her veil down.—Agnes, in spite of herself, was delighted with the representation,—but, as

she was desirous of leaving the house before the farce began; yet, as Clifford saw a gentleman in the lower boxes with whom he had business, she consented to stay till he had spoken to him. Soon after she saw Clifford enter the lower box opposite to her; and those who know what it is to love, will not be surprised to hear that Agnes had more pleasure in looking at her lover, and drawing favourable comparisons between him and the gentlemen who surrounded him, than in attending to the farce.

She had been some moments absorbed in this pleasing employment, when two gentlemen entered the box where she was, and seated themselves behind her.

"Who is that elegant, fashionable-looking man, my lord, in the lower box just opposite to us?" said one of the gentlemen to the other.—"I mean, he who is speaking to captain Mowbray."—"It is George Clifford, of the guards," replied his lordship, "and one of the cleverest fellows in England, colonel."

Agnes, who had not missed one word of this conversation, now became still more attentive.

"Oh! I have heard a great deal of him," returned the colonel, "and as much against him as for him."—"Most likely," said his lordship; "I dare say that fellow has ruined more young men, and seduced more young women, than any man of his age (which is only four-and-thirty) in the kingdom."

Agnes sighed deeply, and felt herself attacked by a sort of faint sickness.

"But it is to be hoped that he will reform now," observed the colonel: "I hear he is going to be married to miss Sandford, the great city heiress."—"So he is,—and Monday is the day fixed for the wedding."

Agnes started:—Clifford himself had told her he must leave her on Monday for some weeks;—and in breathless expectation she listened to what followed.

—"But what then?" continued his lordship: "He marries for money merely. The truth is, his father is lately come to a long disputed barony, and with scarcely an acre of land to support the dignity of it: so his son has consented to marry an heiress, in order to make the family rich, as well as noble. You must know, I have my information from the fountain-head;—Clifford's mother is my relation, and the good woman thought proper to acquaint me in form with the advantageous alliance which her hopeful son was about to make."

This confirmation of the truth of a story, which she till now hoped might be mere report, was more than Agnes could well bear; but, made courageous by desperation, she resolved to listen while they continued to talk on this subject. Mrs. Askew, in the mean while, was leaning over the box, too much engrossed by the farce to attend to what was passing behind her. Just as his lordship concluded the last sentence, Agnes saw Clifford go out with his friend; and she who had but the minute before gazed on him with looks of admiring fondness, now wished, in the bitterness of her soul, that she might never behold him again!

"I never wish," said the colonel, "a match of interest to be a happy one."—"Nor will this be so, depend on it," answered his lordship; "for, besides that miss Sandford is ugly and disagreeable, she has a formidable rival."—"Indeed!" cried the other;—"a favourite mistress, I suppose?"

Here the breath of Agnes grew shorter and shorter; she suspected that they were going to talk of her; and, under other circumstances, her nice sense of honour would have prevented her attending to a conversation which she was certain was not meant for her ear: but so great was the importance of the present discourse to her future peace and well-being, that it annihilated all sense of impropriety in listening to it.

"Yes, he has a favourite mistress," answered his lordship,—"a girl who was worthy of a better fate."—"You know her then?" asked the colonel.—"No," replied he,—"by name only; but when I was in the neighbourhood of the town where she lived, I heard continually of her beauty and accomplishments: her name is Agnes Fitz—Fitz—"—"Fitzhenry, I suppose," said the other.—"Yes, that is the name," said his lordship: "How came you to guess it?"—"Because Agnes Fitzhenry is a name which I have often heard toasted: she sings well, does she not?"—"She does every thing well," rejoined the other; "and was once the pride of her father, and of the town in which she lived."

Agnes could scarcely forbear groaning aloud at this faithful picture of what she once was.

"Poor thing!" resumed his lordship;—"that ever she should be the victim of a villain! It seems he seduced her from her father's house, under pretence of carrying her to Gretna-green; but, on some infernal plea or other, he took her to London."

Here the agitation of Agnes became so visible as to attract Mrs. Askew's notice; but as she assured her that she should be well presently, Mrs. Askew again gave herself up to the illusion of the scene. Little did his lordship think how severely he was wounding the peace of one for whom he felt such compassion.

"You seem much interested about this unhappy girl," said the colonel.—"I am so," replied the other, "and full of the subject too; for Clifford's factotum, Wilson, has been with me this morning, and I learned from him some of his master's tricks, which made me still more anxious about his victim.—It seems she is very fond of her father, though she was prevailed on to desert him, and has never known a happy moment since her elopement; nor could she be easy without making frequent but secret inquiries concerning his health."—"Strange inconsistency!" muttered the colonel.—"This anxiety gave Clifford room to fear that she might at some future moment, if discontented with him, return to her afflicted parent before he was tired of her:—so what do you think he did?"

At this moment Agnes, far more eager to hear what followed than the colonel, turned round, and, fixing her eyes on her unknown friend with wild anxiety, could scarcely help saying, What did Clifford do, my lord?

—"He got his factotum, the man I mentioned, to personate a messenger, and to pretend that he had been to her native town, and then he gave her such accounts as were best calculated to calm her anxiety: but the master-stroke which secured her remaining with him was, his telling the pretended messenger to inform her that her father was married again,—though it is more likely, poor unhappy man, that he is dead, than that he is married."

At the mention of this horrible probability, Agnes lost all self-command, and, screaming aloud, fell back on the knees of the astonished narrator, reiterating her cries with all the alarming helplessness of phrensy.

"Turn her out! turn her out!" echoed through the theatre,—for the audience supposed that the noise proceeded from some intoxicated and abandoned woman; and a man in the next box struck Agnes a blow on the shoulder, and, calling her by a name too gross to repeat, desired her to leave the house, and act her drunken freaks elsewhere.

Agnes, whom the gentlemen behind were supporting with great kindness and compassion, heard nothing of this speech save the injurious epithet applied to herself; and alive only to what she thought the justice of it, "Did you hear that?" she exclaimed, starting up with the look and tone of phrensy—"Did you hear that?—O God! my brain is on fire!"—Then, springing over the seat, she rushed out of the box, followed by the trembling and astonished Mrs. Askew, who in vain tried to keep pace with the desperate speed of Agnes.

Before Agnes, with all her haste, could reach the bottom of the stairs, the farce ended and the lobbies began to fill. Agnes pressed forward, when amongst the crowd she saw a tradesman who lived near her father's house.—No longer sensible of shame, for anguish had annihilated it, she rushed towards him, and, seizing his arm, exclaimed, "For the love of God, tell me how my father is!" The tradesman, terrified and astonished at the pallid wildness of her look, so unlike the countenance of successful and contented vice that he would have expected to see her wear, replied—"He is well, poor soul! but——"—"But unhappy, I suppose?" interrupted Agnes:—"Thank God he is well:—but is he married?"—"Married! dear me, no! he is—"—"Do you think he would forgive me?" eagerly rejoined Agnes.—"Forgive you!" answered the man—"How you talk! Belike he might forgive you, if—"—"I know what you would say," interrupted Agnes again, "if I would return—Enough,—enough:—God bless you! you have saved me from distraction."

So saying, she ran out of the house; Mrs. Askew having overtaken her, followed by the nobleman and the colonel, who with the greatest consternation had found, from an exclamation of Mrs. Askew's, that the object of their compassion was miss Fitzhenry herself.

But before Agnes had proceeded many steps down the street Clifford met her, on his return from a neighbouring coffee-house with his companion; and, spite of her struggles and reproaches, which astonished and alarmed him, he, with Mrs. Askew's assistance, forced her into a hackney-coach, and ordered the man to drive home.—No explanation took place during the ride. To all the caresses and questions of Clifford she returned nothing but passionate exclamations against his perfidy and cruelty. Mrs. Askew thought her insane; Clifford wished to think her so; but his conscience told him that, if by accident his conduct had been discovered to her, there was reason enough for the frantic sorrow which he witnessed.

At length they reached their lodgings, which were in Suffolk-street, Charing-cross; and Agnes, having at length obtained some composure, in as few words as possible related the conversation which she had overheard. Clifford, as might be expected, denied the truth of what his lordship had advanced; but it was no longer in his power to deceive the awakened penetration of Agnes.—Under his assumed unconcern, she clearly saw the confusion of detected guilt: and giving utterance in very strong language to the contempt and indignation which she felt, while contemplating such complete depravity, she provoked Clifford, who was more than half intoxicated, boldly to avow what he was at first eager to deny; and Agnes, who before shuddered at his hypocrisy, was now shocked at his unprincipled daring.

"But what right have you to complain?" added he: "the cheat that I put upon you relative to your father was certainly meant in kindness; and though miss Sandford will have my hand, you alone will ever possess my heart; therefore it was my design to keep you in ignorance of my marriage, and retain you as the greatest of all my worldly treasures.—Plague on this prating lord! he has destroyed the prettiest arrangement ever made. However, I hope we shall part good friends."

"Great God!" cried Agnes, raising her tearless eyes to heaven,—"and have I then forsaken the best of parents for a wretch like this!—But think not, sir," she added, turning with a commanding air towards Clifford, whose temper, naturally warm, the term 'wretch' had not soothed, "think not, fallen as I am, that I will ever condescend to receive protection and support, either for myself or child, from a man whom I know to be a consummate villain. You have made me criminal, but you have not obliterated my horror for crime and my veneration for virtue,—and, in the fulness of my contempt, I inform you, sir, that we shall meet no more."

"Not till to-morrow," said Clifford:—"this is our first quarrel, Agnes; and the quarrels of lovers are only the renewal of love, you know: therefore leaving the 'bitter, piercing air' to guard my treasure for me till to-morrow, I take my leave, and hope in the morning to find you in a better humour."

So saying he departed, secure, from the inclemency of the weather and darkness of the night, that Agnes would not venture to go away before the morning, and resolved to return very early in order to prevent her departure, if her threatened resolution were any thing more than the frantic expressions of a disappointed woman. Besides, he knew that at that time she was scantily supplied with money, and that Mrs. Askew dared not furnish her with any for the purpose of leaving him.

But he left not Agnes, as he supposed, to vent her sense of injury in idle grief and inactive lamentation; but to think, to decide, and to act.—What was the rigour of the night to a woman whose heart was torn by all the pangs which convictions, such as those which she had lately received, could give? She hastily therefore wrapped up her sleeping boy in a pélisse, of which in a calmer moment she would have felt the want herself, and took him in her arms: then, throwing a shawl over her shoulders, she softly unbarred the hall door, and before the noise could have summoned any of the family she was already out of sight.

So severe was the weather, that even those accustomed to brave in ragged garments the pelting of the pitiless storm shuddered, as the freezing wind whistled around them, and crept with trembling knees to the wretched hovel that awaited them. But the winter's wind blew unfelt by Agnes: she was alive to nothing but the joy of having escaped from a villain, and the faint hope that she was hastening to obtain, perhaps, a father's forgiveness.

"Thank Heaven!" she exclaimed, as she found herself at the rails along the Green Park,—"the air which I breathe here is uncontaminated by his breath!" when, as the watchman called half-past eleven o'clock, the recollection that she had no place of shelter for the night occurred to her, and at the same instant she remembered that a coach set off at twelve from Piccadilly, which went within twelve miles of her native place. She therefore immediately resolved to hasten thither, and, either in the inside or on the outside, to proceed on her journey as far as her finances would admit of, intending to walk the rest of the way. She arrived at the inn just as the coach was setting off, and found, to her great satisfaction, one inside place vacant.

Nothing worth mentioning occurred on the journey. Agnes, with her veil drawn over her face, and holding her slumbering boy in her arms, while the incessant shaking of her knee and the piteous manner in which she sighed gave evident marks of the agitation of her mind, might excite in some degree the curiosity of her fellow-travellers, but gave no promise of that curiosity being satisfied, and she was suffered to remain unquestioned and undisturbed.

At noon the next day the coach stopped, for the travellers to dine, and stay a few hours to recruit themselves after their labours past, and to fortify themselves against those yet to come. Here Agnes, who as she approached nearer home became afraid of meeting some acquaintance, resolved to change her dress, and to equip herself in such a manner as should, while it screened her from the inclemency of the weather, at the same time prevent her being recognised by any one. Accordingly she exchanged her pélisse, shawl, and a few other things, for a man's great coat, a red cloth cloak with a hood to it, a pair of thick shoes, and some yards of flannel in which she wrapped up her little Edward; and, having tied her straw bonnet under her chin with her veil, she would have looked like a country-woman drest for market, could she have divested herself of a certain delicacy of appearance and gracefulness of manner, the yet uninjured beauties of former days.

When they set off again she became an outside passenger, as she could not afford to continue an inside one; and covering her child up in the red cloak which she wore over her coat, she took her station on the top of the coach with seeming firmness, but a breaking heart.

Agnes expected to arrive within twelve miles of her native place long before it was dark, and reach the place of her destination before bed-time, unknown and unseen: but she was mistaken in her expectations: for the roads had been rendered so rugged by the frost, that it was late in the evening when the coach reached the spot whence she was to commence her walk; and by the time she had eaten her slight repast, and furnished herself with some necessaries to enable her to resist the severity of the weather, she found that it was impossible for her to reach her long-forsaken home before day-break.

Still she was resolved to go on:—to pass another day in suspense concerning her father, and her future hopes of his pardon, was more formidable to her than the terrors of undertaking a lonely and painful walk. Perhaps too, Agnes was not sorry to have a tale of hardship to narrate on her arrival at the house of her nurse, whom she meant to employ as mediator between her and her offended parent.

His child, his penitent child, whom he had brought up with the utmost tenderness, and screened with unremitting care from the ills of life, returning, to implore his pity and forgiveness, on foot, and unprotected, through all the dangers of lonely paths, and through the horrors of a winter's night, must, she flattered herself, be a picture too affecting for Fitzhenry to think upon without some commiseration; and she hoped he would in time bestow on her his forgiveness;—to be admitted to his presence, was a favour which she dared not presume either to ask or expect.

But, in spite of the soothing expectation which she tried to encourage, a dread of she knew not what took possession of her mind.—Every moment she looked fearfully around her, and, as she beheld the wintry waste spreading on every side, she felt awe-struck at the desolateness of her situation. The sound of a human voice would, she thought, have been rapture to her ear; but the next minute she believed that it would have made her sink in terror to the ground.—"Alas!" she mournfully exclaimed, "I was not always timid and irritable as I now feel;—but then I was not always guilty:—O my child! would I were once more innocent like thee!" So saying, in a paroxysm of grief she bounded forward on her way, as if hoping to escape by speed from the misery of recollection.

Agnes was now arrived at the beginning of a forest, about two miles in length, and within three of her native place. Even in her happiest days she never entered its solemn shade without feeling a sensation of fearful awe; but now that she entered it, leafless as it was, a wandering wretched outcast, a mother without the sacred name of wife, and bearing in her arms the pledge of her infamy, her knees smote each other, and, shuddering as if danger were before her, she audibly implored the protection of Heaven.

At this instant she heard a noise, and, casting a startled glance into the obscurity before her, she thought she saw something like a human form running across the road. For a few moments she was motionless with terror; but, judging from the swiftness with which the object disappeared that she had inspired as much terror as she felt, she ventured to pursue her course. She had not gone far when she again beheld the cause of her fear; but hearing, as it moved, a noise like the clanking of a chain, she concluded that it was some poor animal which had been turned out to graze.

Still, as she gained on the object before her, she was convinced it was a man that she beheld; and, as she heard the noise no longer, she concluded that it had been the result of fancy only: but that, with every other idea, was wholly absorbed in terror when she saw the figure standing still, as if waiting for her approach.—"Yet why should I fear?" she inwardly observed: "it may be a poor wanderer like myself, who is desirous of a companion;—if so, I shall rejoice in such a rencontre."

As this reflection passed her mind, she hastened towards the stranger, when she saw him look hastily around him, start, as if he beheld at a distance some object that alarmed him, and then, without taking any notice of her, run on as fast as before. But what can express the horror of Agnes when she again heard the clanking of a chain, and discovered that it hung to the ankle of the stranger!—"Surely he must be a felon," murmured Agnes:—"O my poor boy! perhaps we shall both be murdered!—This suspense is not to be borne: I will follow him, and meet my fate at once."—Then, summoning all her remaining strength, she followed the alarming fugitive.

After she had walked nearly a mile further, and, as she did not overtake him, had flattered herself that he had gone in a contrary direction, she saw him seated on the ground, and, as before, turning his head back with a sort of convulsive quickness; but as it was turned from her, she was convinced that she was not the object which he was seeking. Of her he took no notice; and her resolution of accosting him failing when she approached, she walked hastily past, in hopes that she might escape him entirely.

As she passed, she heard him talking and laughing to himself, and thence concluded that he was not a felon, but a lunatic escaped from confinement. Horrible as this idea was, her fear was so far overcome by pity, that she had a wish to return, and offer him some of the refreshment which she had procured for herself and child, when she heard him following her very fast, and was convinced by the sound, the dreadful sound of his chain, that he was coming up to her.

The clanking of a fetter, when one knows that it is fastened round the limbs of a fellow-creature, always calls forth in the soul, of sensibility a sensation of horror: what then, at this moment, must have been its effect on Agnes, who was trembling for her life, for that of her child, and looking in vain for a protector around the still, solemn waste! Breathless with apprehension, she stopped as the maniac gained upon her, and, motionless and speechless, awaited the consequence of his approach.

"Woman!" said he in a hoarse, hollow tone,—"Woman! do you see them? Do you see them?"—"Sir! pray what did you say, sir?" cried Agnes in a tone of respect, and curtsying as she spoke,—for what is so respectful as fear?—"I can't see them," resumed he, not attending to her, "I have escaped them! Rascals! cowards! I have escaped them!" and then he jumped and clapped his hands for joy.

Agnes, relieved in some measure from her fears, and eager to gain the poor wretch's favour, told him that she rejoiced at his escape from the rascals, and hoped that they would not overtake him: but while she spoke he seemed wholly inattentive, and, jumping as he walked, made his fetter clank in horrid exultation.

The noise at length awoke the child, who, seeing a strange and indistinct object before him, and hearing a sound so unusual, screamed violently, and hid his face in his mother's bosom.

"Take it away! take it away!" exclaimed the maniac,—"I do not like children."—Agnes, terrified at the thought of what might happen, tried to sooth the trembling boy to rest, but in vain; the child still screamed, and the angry agitation of the maniac increased.—"Strangle it! strangle it!" he cried—"do it this moment, or——"

Agnes, almost frantic with terror, conjured the unconscious boy, if he valued his life, to cease his cries; and then the next moment she conjured the wretched man to spare her child: but, alas! she spoke to those incapable of understanding her,—a child and a madman!—The terrified boy still shrieked, the lunatic still threatened; and, clenching his fist, seized the left arm of Agnes, who with the other attempted to defend her infant from his fury; when, at the very moment that his fate seemed inevitable, a sudden gale of wind shook the leafless branches of the surrounding trees; and the madman, fancying that the noise proceeded from his pursuers, ran off with his former rapidity.

Immediately the child, relieved from the sight and the sound which alarmed it, and exhausted by the violence of its cries, sunk into a sound sleep on the throbbing bosom of its mother. But, alas! Agnes knew that this was but a temporary escape:—the maniac might return, and again the child might wake in terrors:—and scarcely had the thought passed her mind when she saw him coming back; but, as he walked slowly, the noise was not so great as before.

"I hate to hear children cry," said he as he approached.—"Mine is quiet now," replied Agnes: then, recollecting that she had some food in her pocket, she offered some to the stranger, in order to divert his attention from the child. He snatched it from her hand instantly, and devoured it with terrible voraciousness; but again he exclaimed, "I do not like children;—if you trust them they will betray you:" and Agnes offered him food again, as if to bribe him to spare her helpless boy.—"I had a child once,—but she is dead, poor soul!" continued he, taking Agnes by the arm, and leading her gently forward.—"And you loved her very tenderly, I suppose?" said Agnes, thinking that the loss of his child had occasioned his malady; but, instead of answering her, he went on:—"They said that she ran away from me with a lover,—but I knew they lied; she was good, and would not have deserted the father who doted on her.—Besides, I saw her funeral myself.—Liars, rascals, as they are!—Do not tell any one: I got away from them last night, and am now going to visit her grave."

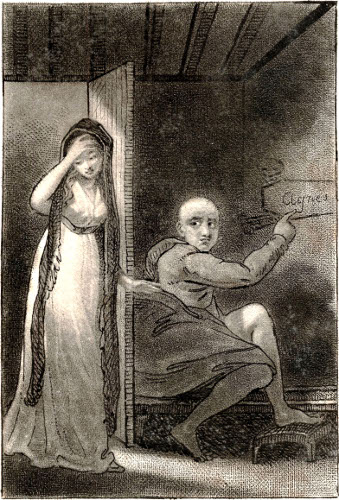

A death-like sickness, an apprehension so horrible as to deprive her almost of sense, took possession of the soul of Agnes. She eagerly tried to obtain a sight of the stranger's face, the features of which the darkness had hitherto prevented her from distinguishing: she however tried in vain, as his hat was pulled over his forehead, and his chin rested on his bosom. But they had now nearly gained the end of the forest, and day was just breaking; and Agnes, as soon as they entered the open plain, seized the arm of the madman to force him to look towards her,—for speak to him she could not. He felt, and perhaps resented the importunate pressure of her hand—for he turned hastily round—when, dreadful confirmation of her fears, Agnes beheld her father!!!

It was indeed Fitzhenry, driven to madness by his daughter's desertion and disgrace!!

After the elopement of Agnes, Fitzhenry entirely neglected his business, and thought and talked of nothing but the misery which he experienced. In vain did his friends represent to him the necessity of his making amends, by increased diligence, for some alarming losses in trade which he had lately sustained. She, for whom alone he toiled, had deserted him—and ruin had no terrors for him.—"I was too proud of her," he used mournfully to repeat,—"and Heaven has humbled me even in her by whom I offended."

Month after month elapsed, and no intelligence of Agnes.—Fitzhenry's dejection increased, and his affairs became more and more involved: at length, absolute and irretrievable bankruptcy was become his portion, when he learned, from authority not to be doubted, that Agnes was living with Clifford as his acknowledged mistress.—This was the death-stroke to his reason: and the only way in which his friends (relations he had none, or only distant ones) could be of any further service to him was, by procuring him admission into a private madhouse in the neighbourhood.

Of his recovery little hope was entertained.—The constant theme of his ravings was his daughter;—sometimes he bewailed her as dead; at other times he complained of her as ungrateful:—but so complete was the overthrow which his reason had received, that he knew no one, and took no notice of those whom friendship or curiosity led to his cell: yet he was always meditating his escape; and, though ironed in consequence of it, the night he met Agnes, he had, after incredible difficulty and danger, effected his purpose.

But to return to Agnes, who, when she beheld in her insane companion her injured father, the victim probably of her guilt, let fall her sleeping child, and, sinking on the ground, extended her arms towards Fitzhenry, articulating in a faint voice, "O God! My father!" then prostrating herself at his feet, she clasped his knees in an agony too great for utterance.

At the name of 'father,' the poor maniac started, and gazed on her earnestly, with savage wildness, while his whole frame became convulsed; then, rudely disengaging himself from her embrace, he ran from her a few paces, and dashed himself on the ground in all the violence of phrensy. He raved; he tore his hair; he screamed, and uttered the most dreadful execrations; and, with his teeth shut and his hands clenched, he repeated the word 'father,' and said the name was mockery to him.

Agnes, in mute and tearless despair, beheld the dreadful scene: in vain did her affrighted child cling to her gown, and in its half-formed accents entreat to be taken to her arms again: she saw, she heeded nothing but her father; she was alive to nothing but her own guilt and its consequences; and she awaited with horrid composure the cessation of Fitzhenry's phrensy, or the direction of its fury towards her child.

At last, she saw him fall down exhausted and motionless, and tried to hasten to him; but she was unable to move, and reason and life seemed at once forsaking her, when Fitzhenry suddenly started up, and approached her.—Uncertain as to his purpose, Agnes caught her child to her bosom, and, falling again on her knees, turned on him her almost closing eyes; but his countenance was mild,—and gently patting her forehead, on which hung the damps of approaching insensibility, "Poor thing!" he cried, in a tone of the utmost tenderness and compassion, "Poor thing!" and then gazed on her with such inquiring and mournful looks, that tears once more found their way and relieved her bursting brain, while seizing her father's hand she pressed it with frantic emotion to her lips.

Fitzhenry looked at her with great kindness, and suffered her to hold his hand;—then exclaimed, "Poor thing!—don't cry,—don't cry;—I can't cry,—I have not cried for many years,—not since my child died.—For she is dead, is she not?" looking earnestly at Agnes, who could only answer by her tears.—"Come," said he, "come," taking hold of her arm, then laughing wildly, "Poor thing! you will not leave me, will you?"—"Leave you!" she replied: "Never:—I will live with you—die with you."—"True, true," cried he, "she is dead, and we will go visit her grave."—So saying, he dragged Agnes forward with great velocity; but as it was along the path leading to the town, she made no resistance.

Indeed it was such a pleasure to her to see that though he knew her not, the sight of her was welcome to her unhappy parent, that she sought to avoid thinking of the future, and to be alive only to the present: she tried also to forget that it was to his not knowing her that she owed the looks of tenderness and pity which he bestowed on her, and that the hand which now kindly held hers, would, if recollection returned, throw her from him with just indignation.

But she was soon awakened to redoubled anguish, by hearing Fitzhenry, as he looked behind him, exclaim, "They are coming! they are coming!" and as he said this, he ran with frantic haste across the common. Agnes, immediately looking behind her, saw three men pursuing her father at full speed, and concluded that they were the keepers of the bedlam whence he had escaped. Soon after, she saw the poor lunatic coming towards her, and had scarcely time to lay her child gently on the ground, before Fitzhenry threw himself in her arms, and implored her to save him from his pursuers.

In an agony that mocks description, Agnes clasped him to her heart, and awaited in trembling agitation the approach of the keepers.—"Hear me! hear me!" she cried; "I conjure you to leave him to my care: He is my father, and you may safely trust him with me."—"Your father!" replied one of the men; "and what then, child? You could do nothing for him, and you should be thankful to us, young woman, for taking him off your hands.—So come along, master, come along," he continued, seizing Fitzhenry, who could with difficulty be separated from Agnes,—while another of the keepers, laughing as he beheld her wild anguish, said, "We shall have the daughter as well as the father soon, I see, for I do not believe there is a pin to choose between them."

But severe as the sufferings of Agnes were already, a still greater pang awaited her. The keepers finding it a very difficult task to confine Fitzhenry, threw him down, and tried by blows to terrify him into acquiescence. At this outrage Agnes became frantic indeed, and followed them with shrieks, entreaties, and reproaches; while the struggling victim called on her to protect him, as they bore him by violence along, till, exhausted with anguish and fatigue, she fell insensible on the ground, and lost in a deep swoon the consciousness of her misery.

When she recovered her senses all was still around her, and she missed her child. Then hastily rising, and looking round with renewed phrensy, she saw it lying at some distance from her, and on taking it up she found that it was in a deep sleep. The horrid apprehension immediately rushed on her mind, that such a sleep in the midst of cold so severe was the sure forerunner of death.

"Monster!" she exclaimed, "destroyer of thy child, as well as father!—But perhaps it is not yet too late, and my curse is not completed."—So saying, she ran, or rather flew, along the road; and seeing a house at a distance she made towards it, and, bursting open the door, beheld a cottager and his family at breakfast:—then, sinking on her knees, and holding out to the woman of the house her sleeping boy, "For the love of God," she cried, "look here! look here! Save him! O save him!"

A mother appealing to the heart of a mother is rarely unsuccessful in her appeal.—The cottager's wife was as eager to begin the recovery of the child of Agnes as Agnes herself, and in a moment the whole family was employed in its service; nor was it long before they were rewarded for their humanity by its complete restoration.

The joy of Agnes was frantic as her grief had been.—She embraced them all by turns, in a loud voice invoked blessings on their heads, and promised, if she was ever rich, to make their fortune:—lastly, she caught the still languid boy to her heart, and almost drowned it in her tears.

In the cottager and his family a scene like this excited wonder as well as emotion. He and his wife were good parents; they loved their children,—would have been anxious during their illness, and would have sorrowed for their loss: but to these violent expressions and actions, the result of cultivated sensibility, they were wholly unaccustomed, and could scarcely help imputing them to insanity,—an idea which the pale cheek and wild look of Agnes strongly confirmed; nor did it lose strength when Agnes, who in terror at her child's danger and joy for his safety had forgotten even her father and his situation, suddenly recollecting herself, exclaimed, "Have I dared to rejoice?—Wretch that I am! Oh! no;—there is no joy for me!" The cottager and his wife, on hearing these words, looked significantly at each other.

Agnes soon after started up, and, clasping her hands, cried out, "O my father! my dear, dear father! thou art past cure; and despair must be my portion."

"Oh! you are unhappy because your father is ill," observed the cottager's wife; "but do not be so sorrowful on that account, he may get better perhaps."

"Never, never," replied Agnes;—"yet who knows?"

"Aye; who knows indeed?" resumed the good woman. "But if not, you nurse him yourself, I suppose; and it will be a comfort to you to know he has every thing done for him that can be done."

Agnes sighed deeply.

"I lost my own father," continued she, "last winter, and a hard trial it was, to be sure; but then it consoled me to think I made his end comfortable. Besides, my conscience told me that, except here and there, I had always done my duty by him, to the best of my knowledge."

Agnes started from her seat, and walked rapidly round the room.

"He smiled on me," resumed her kind hostess, wiping her eyes, "to the last moment; and just before the breath left him, he said, 'Good child! good child!' O! it must be a terrible thing to lose one's parents when one has not done one's duty to them!"

At these words Agnes, contrasting her conduct and feelings with those of this artless and innocent woman, was overcome with despair, and seizing a knife that lay by her endeavoured to put an end to her existence; but the cottager caught her hand in time to prevent the blow, and his wife easily disarmed her, as her violence instantly changed into a sort of stupor: then throwing herself back on the bed on which she was sitting, she lay with her eyes fixt, and incapable of moving.

The cottager and his wife now broke forth into expressions of wonder and horror at the crime which she was going to commit, and the latter taking little Edward from the lap of her daughter, held it towards Agnes:—"See," cried she, as the child stretched forth its little arms to embrace her,—"unnatural mother! would you forsake your child?"

These words, assisted by the caresses of the child himself, roused Agnes from her stupor.—"Forsake him! Never, never!" she faltered out: then, snatching him to her bosom, she threw herself back on a pillow which the good woman had placed under her head; and soon, to the great joy of the compassionate family, both mother and child fell into a sound sleep. The cottager then repaired to his daily labour, and his wife and children began their household tasks; but ever and anon they cast a watchful glance on their unhappy guest, dreading lest she should make a second attempt on her life.

The sleep of both Agnes and her child was so long and heavy, that night was closing in when the little boy awoke, and by his cries for food broke the rest of his unhappy mother.

But consciousness returned not with returning sense;—Agnes looked around her, astonished at her situation. At length, by slow degrees, the dreadful scenes of the preceding night and her own rash attempt burst on her recollection; she shuddered at the retrospect, and, clasping her hands, together, remained for some moments in speechless prayer:—then she arose; and, smiling mournfully at sight of her little Edward eating voraciously the milk and bread that was set before him, she seated herself at the table, and tried to partake of the coarse but wholesome food provided for her. As she approached, she saw the cottager's wife remove the knives. This circumstance forcibly recalled her rash action, and drove away her returning appetite.—"You may trust me now," she said; "I shrink with horror from my wicked attempt on my life, and swear, in the face of Heaven, never to repeat it: no,—my only wish now is, to live and to suffer."

Soon after, the cottager's wife made an excuse for bringing back a knife to the table, to prove to Agnes her confidence in her word; but this well-meant attention was lost on her,—she sat leaning on her elbow, and wholly absorbed in her own meditations.

When it was completely night, Agnes arose to depart.—"My kind friends," said she, "who have so hospitably received and entertained a wretched wanderer, believe me I shall never forget the obligations which I owe you, though I can never hope to repay them; but accept this (taking her last half-guinea from her pocket) as a pledge of my inclination to reward your kindness. If I am ever rich you shall—" Here her voice failed her, and she burst into tears.

This hesitation gave the virtuous people whom she addressed an opportunity of rejecting her offers.—"What we did, we did because we could not help it," said the cottager.—"You would not have had me see a fellow-creature going to kill soul and body too, and not prevent it, would you?"—"And as to saving the child," cried the wife, "am I not a mother myself, and can I help feeling for a mother? Poor little thing! it looked so piteous too, and felt so cold!"

Agnes could not speak; but still, by signs she tendered the money to their acceptance.—"No, no," resumed the cottager, "keep it for those who may not be willing to do you a service for nothing:"—and Agnes reluctantly replaced the half-guinea. But then a fresh source of altercation began; the cottager insisted on seeing Agnes to the town, and she insisted on going by herself: at last she agreed that he should go with her as far as the street where her friends lived, wait for her at the end of it, and if they were not living, or were removed, she was to return, and sleep at the cottage.

Then, with a beating heart and dejected countenance, Agnes took her child in her arms, and, leaning on her companion, with slow and unsteady steps she began to walk to her native place, once the scene of her happiness and her glory, but now about to be the witness of her misery and her shame.

As they drew near the town, Agnes saw on one side of the road a new building, and instantly hurried from it as fast as her trembling limbs could carry her.—"Did you hear them?" asked the cottager.—"Hear whom?" said Agnes.—"The poor creatures," returned her companion, "who are confined there. That is the new bedlam, and—Hark! what a loud scream that was!"

Agnes, unable to support herself, staggered to a bench that projected from the court surrounding the building, while the cottager, unconscious why she stopped, observed it was strange that she should like to stay and hear the poor creatures—For his part, he thought it shocking to hear them shriek, and still more so to hear them laugh—"for it is so piteous," said he, "to hear those laugh who have so much reason to cry."

Agnes had not power to interrupt him, and he went on:—"This house was built by subscription; and it was begun by a kind gentleman of the name of Fitzhenry, who afterwards, poor soul, being made low in the world by losses in trade, and by having his brain turned by a good-for-nothing daughter, was one of the first patients in it himself."—Here Agnes, to whom this recollection had but too forcibly occurred already, groaned aloud. "What, tired so soon?" said her companion: "I doubt you have not been used to stir about—you have been too tenderly brought up. Ah! tender parents often spoil children, and they never thank them for it when they grow up neither, and often come to no good besides."

Agnes was going to make some observations wrung from her by the poignancy of self-upbraiding, when she heard a loud cry as of one in agony: fancying it her father's voice, she started up, and stopping her ears, ran towards the town so fast that it was with difficulty that the cottager could overtake her. When he did so, he was surprised at the agitation of her manner.—"What, I suppose you thought they were coming after you?" said he. "But there was no danger—I dare say it was only an unruly one whom they were beating."—Agnes, on hearing this, absolutely screamed with agony: and seizing the cottager's arm, "Let us hasten to the town," said she in a hollow and broken voice, "while I have strength enough left to carry me thither." At length they entered its walls, and the cottager said, "Here we are at last.—A welcome home to you, young woman."—"Welcome! and home to me!" cried Agnes wildly—"I have no home now—I can expect no welcome! Once indeed——" Here, overcome with recollections almost too painful to be endured, she turned from him and sobbed aloud, while the kind-hearted man could scarcely forbear shedding tears at sight of such mysterious, yet evidently real, distress.

In happier days, when Agnes used to leave home on visits to her distant friends, anticipation of the welcome she should receive on her return was, perhaps, the greatest pleasure that she enjoyed during her absence. As the adventurer to India, while toiling for wealth, never loses sight of the hope that he shall spend his fortune in his native land,—so Agnes, whatever company she saw, whatever amusements she partook of, looked eagerly forward to the hour when she should give her expecting father and her affectionate companions a recital of all that she had heard and seen. For, though she had been absent a few weeks only, "her presence made a little holiday," and she was received by Fitzhenry with delight too deep to be expressed; while, even earlier than decorum warranted, her friends were thronging to her door to welcome home the heightener of their pleasures, and the gentle soother of their sorrows; (for Agnes "loved and felt for all:" she had a smile ready to greet the child of prosperity, and a tear for the child of adversity)—As she was thus honoured, thus beloved, no wonder the thoughts of home, and of returning home, were wont to suffuse the eyes of Agnes with tears of exquisite pleasure; and that, when her native town appeared in view, a group of expecting and joyful faces used to swim before her sight, while, hastening forward to have the first glance of her, fancy used to picture her father!—--Now, dread reverse! after a long absence, an absence of years, she was returning to the same place, inhabited by the same friends: but the voices that used to be loud in pronouncing her welcome, would now be loud in proclaiming indignation at her sight; the eyes that used to beam with gladness at her presence, would now be turned from her with disgust; and the fond father, who used to be counting the moments till she arrived, was now——I shall not go on——suffice, that Agnes felt, to "her heart's core," all the bitterness of the contrast.

When they arrived near the place of her destination, Agnes stopped, and told the cottager that they must part.—"So much the worse," said the good man: "I do now know how it is, but you are so sorrowful, yet so kind and gentle, somehow, that both my wife and I have taken a liking to you:—you must not be angry, but we cannot help thinking you are not one of us, but a lady, though you are so disguised and so humble;—but misfortune spares no one, you know."