* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few

restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make

a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different

display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of

the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please

check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under

copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your

country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright

in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: National Music

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Date first posted: August 30 2012

Date last updated: August 30 2012

Faded Page eBook #20120837

This ebook was produced by: Dianna Adair, Stephen Hutcheson, Mark Akrigg, Marcia Brooks

& the Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE MARY FLEXNER LECTURES

ON THE HUMANITIES

II

These lectures were delivered at BRYN MAWR COLLEGE,

OCTOBER and NOVEMBER 1932 on a fund established by

BERNARD FLEXNER in honour of his sister

NATIONAL MUSIC

NATIONAL MUSIC

By

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

D. Mus.

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON · NEW YORK · TORONTO

1934

Copyright, 1934, by

Ralph Vaughan Williams

FIRST EDITION

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

[3]

I

SHOULD MUSIC BE NATIONAL?

Whistler used to say that it was as ridiculous

to talk about national art as national

chemistry. In saying this he failed to see the difference

between art and science.

Science is the pure pursuit of knowledge and thus

knows no boundaries. Art, and especially the art

of music, uses knowledge as a means to the evocation

of personal experience in terms which will be intelligible

to and command the sympathy of others.

These others must clearly be primarily those who

by race, tradition, and cultural experience are the

nearest to him; in fact those of his own nation, or

other kind of homogeneous community. In the

sister arts of painting and poetry this factor of nationality

is more obvious, due in poetry to the

Tower of Babel and in painting to the fact that

the painter naturally tends to build his visual

imagination on what he normally sees around him.

But unfortunately for the art of music some misguided

thinker, probably first cousin to the man

who invented the unfortunate phrase “a good European,”

has described music as “the universal language.”

It is not even true that music has an

[4]

universal vocabulary, but even if it were so it is the

use of the vocabulary that counts and no one supposes

that French and English are the same language

because they happen to use twenty-five out of

twenty-six of the letters of their alphabet in common.

In the same way, in spite of the fact that they

have a musical alphabet in common, nobody could

mistake Wagner for Verdi or Debussy for Richard

Strauss. And, similarly, in spite of wide divergencies

of personal style, there is a common factor in

the music say of Schumann and Weber.

And this common factor is nationality. As Hubert Parry

said in his inaugural address to the Folk

Song Society of England, “True Style comes not

from the individual but from the products of

crowds of fellow-workers who sift and try and try

again till they have found the thing that suits their

native taste.... Style is ultimately national.”

I am speaking, for the moment, not of the appeal

of a work of art, but of its origin. Some music

may appeal only in its immediate surroundings;

some may be national in its influence and some

may transcend these bounds and be world-wide in

its acceptance. But we may be quite sure that the

composer who tries to be cosmopolitan from the

outset will fail, not only with the world at large,

but with his own people as well. Was anyone ever

more local, or even parochial, than Shakespeare?

Even when he follows the fashion and gives his

characters Italian names they betray their origin

at once by their language and their sentiments.

[5]

Possibly you may think this an unfair example,

because a poet has not the common vocabulary of

the musician, so let me take another example.

One of the three great composers of the world

(personally I believe the greatest) was John Sebastian

Bach. Here, you may say, is the universal musician

if ever there was one; yet no one could be

more local, in his origin, his life work, and his fame

for nearly a hundred years after his death, than

Bach. He was to outward appearance no more

than one of a fraternity of town organists and “town

pipers” whose business it was to provide the necessary

music for the great occasions in church and

city. He never left his native country, seldom even

his own city of Leipzig. “World Movements” in

art were then unheard of; moreover, it was the tradition

of his own country which inspired him.

True, he studied eagerly all the music of foreign

composers that came his way in order to improve

his craft. But is not the work of Bach built up

on two great foundations, the organ music of his

Teutonic predecessors and the popular hymn tunes

of his own people? Who has heard nowadays of

the cosmopolitan hero Marchand, except as being

the man who ran away from the Court of Dresden

to avoid comparison with the local organist Bach?

In what I have up to now said I shall perhaps

not have been clear unless I dispose at once of two

fallacies. The first of these is that the artist invents

for himself alone. No man lives or moves or could

do so, even if he wanted to, for himself alone. The

[6]

actual process of artistic invention, whether it be by

voice, verse or brush, presupposes an audience; someone

to hear, read or see. Of course the sincere artist

cannot deliberately compose what he dislikes. But

artistic inspiration is like Dryden’s angel which

must be brought down from heaven to earth. A

work of art is like a theophany which takes different

forms to different beholders. In other words,

a composer wishes to make himself intelligible.

This surely is the prime motive of the act of artistic

invention and to be intelligible he must clothe his

inspiration in such forms as the circumstances of

time, place and subject dictate.

This should come unself-consciously to the artist,

but if he consciously tries to express himself in a

way which is contrary to his surroundings, and

therefore to his own nature, he is evidently being,

though perhaps he does not know it, insincere. It

is surely as bad to be self-consciously cosmopolitan

as self-consciously national.

The other fallacy is that the genius springs from

nowhere, defies all rules, acknowledges no musical

ancestry and is beholden to no tradition. The first

thing we have to realize is that the great men of

music close periods; they do not inaugurate them.

The pioneer work, the finding of new paths, is left

to the smaller men. We can trace the musical

genealogy of Beethoven, starting right back from

Philipp Emanuel Bach, through Haydn and Mozart,

with even such smaller fry as Cimarosa and Cherubini

to lay the foundations of the edifice. Is

[7]

not the mighty river of Wagner but a confluence

of the smaller streams, Weber, Marschner and

Liszt?

I would define genius as the right man in the right

place at the right time. We know, of course, too

many instances of the time being ripe and the place

being vacant and no man to fill it. But we shall

never know of the numbers of “mute and inglorious

Miltons” who failed because the place and time

were not ready for them. Was not Purcell a genius

born before his time? Was not Sullivan a jewel

in the wrong setting?

I read the other day in a notice by a responsible

music critic that “it only takes one man to write a

symphony.” Surely this is an entire misconception.

A great work of art can only be born under

the right surroundings and in the right atmosphere.

Bach himself, if I may again quote him as an example,

was only able to produce his fugues, his Passions,

his cantatas, because there had preceded him

generations of smaller composers, specimens of the

despised class of “local musicians” who had no other

ambition than to provide worthily and with dignity

the music required of them: craftsmen perhaps

rather than conscious artists. Thus there spread

among the quiet and unambitious people of northern

Germany a habit, so to speak, of music, the

desire to make it part of their daily life, and it was

into this atmosphere that John Sebastian Bach was

born.

The ideal thing, of course, would be for the

[8]

whole community to take to music as it takes to

language from its youth up, naturally, without conscious

thought or specialized training; so that, just as

the necessity for expressing our material wants leads

us when quite young to perfect our technique of

speaking, so our spiritual wants should lead us to

perfect our technique of emotional expression and

above all that of music. But this is an age of specialization

and delegation. We employ specialists

to do more and more for us instead of doing it ourselves.

We even get other people to play our games

for us and look on shivering at a football match,

instead of getting out of it for ourselves the healthy

exercise and excitement which should surely be its

only object.

Specialization may be all very well in purely material

things. For example, we cannot make good

cigars in England and it is quite right therefore

that we should leave the production of that luxury

to others and occupy ourselves in making something

which our circumstances and climate permit of.

The most rabid Chauvinist has never suggested

that Englishmen should be forced to smoke impossible

cigars merely because they are made at

home. We say quite rightly that those who want

that luxury and can afford it must get it from

abroad.

Now there are some people who apply this

“cigar” theory to the arts and especially to music;

to music especially, because music is not one of the

“naturally protected” industries like the sister

[9]

arts of painting and poetry. The “cigar” theory

of music is then this—I am speaking of course

of my own country England, but I believe it

exists equally virulently in yours: that music is

not an industry which flourishes naturally in our

climate; that, therefore, those who want it and can

afford it must hire it from abroad. This idea has

been prevalent among us for generations. It began

in England, I think, in the early 18th century when

the political power got into the hands of the entirely

uncultured landed gentry and the practice of art

was considered unworthy of a gentleman, from which

it followed that you had to hire a “damned foreigner”

to do it for you if you wanted it, from which

in its turn followed the corollary that the type of

music which the foreigner brought with him was

the only type worth having and that the very different

type of music which was being made at home

must necessarily be wrong. These ideas were fostered

by the fact that we had a foreign court at St.

James’s who apparently did not share the English

snobbery about home-made art and so brought the

music made in their own homes to England with

them. So, the official music, whether it took the

form of Mr. Handel to compose an oratorio, or an

oboe player in a regimental band, was imported from

Germany. This snobbery is equally virulent to this

day. The musician indeed is not despised, but it

is equally felt that music cannot be something which

is native to us and when imported from abroad it

must of necessity be better.

[10]

Let me take an analogy from architecture. When

a stranger arrives in New York he finds imitations

of Florentine palaces, replicas of Gothic cathedrals,

suggestions of Greek temples, buildings put up

before America began to realize that she had an

artistic consciousness of her own.

All these things the visitor dismisses without interest

and turns to her railway stations, her offices

and shops; buildings dictated by the necessity of the

case, a truly national style of architecture evolved

from national surroundings. Should it not be the

same with music?

As long as a country is content to take its music

passively there can be no really artistic vitality in

the nation. I can only speak from the experience

of my own country. In England we are too apt to

think of music in terms of the cosmopolitan celebrities

of the Queen’s Hall and Covent Garden Opera.

These are, so to speak, the crest of the wave, but

behind that crest must be the driving force which

makes the body of the wave. It is below the surface

that we must look for the power which occasionally

throws up a Schnabel, a Sibelius, or a Toscanini.

What makes me hope for the musical future of any

country is not the distinguished names which appear

on the front page of the newspapers, but the

music that is going on at home, in the schools, and

in the local choral societies.

Can we expect garden flowers to grow in soil so

barren that the wild flowers cannot exist there?

Perhaps one day the supply of international artists

[11]

will fail us and we shall turn in vain to our own

country to supply their places. Will there be any

source to supply it from? You remember the story

of the nouveau riche who bought a plot of land

and built a stately home on it, but he found that

no amount of money could provide him straightaway

with the spreading cedars and immemorial

elms and velvet lawns which should be the accompaniment

of such a home. Such things can only

grow in a soil prepared by years of humble toil.

Hubert Parry in his book, “The Evolution of the

Art of Music,” has shown how music like everything

else in the world is subject to the laws of evolution,

that there is no difference in kind but only

in degree between Beethoven and the humblest

singer of a folk-song. The principles of artistic

beauty, of the relationships of design and expression,

are neither trade secrets nor esoteric mysteries

revealed to the few; indeed if these principles are

to have any meaning to us they must be founded on

what is natural to the human being. Perfection of

form is equally possible in the most primitive music

and in the most elaborate.

The principles which govern the composition of

music are, we find, not arbitrary rules, nor as some

people apparently think, barriers put up by mediocre

practitioners to prevent the young genius from

entering the academic grove; they are not the tricks

of the trade or even the mysteries of the craft, they

are founded on the very nature of human beings.

Take, for example, the principle of repetition as a

[12]

factor of design: either the cumulative effect of

mere reiteration, such as we get in the Trio of the

scherzo of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, or in a

cruder form in Ravel’s Bolero; or the constant

repetition of a ground bass as in Bach’s organ Passacaglia

or the finale of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony.

Travellers tell us that the primitive savage as soon as

he gets as far as inventing some little rhythmical or

melodic pattern will repeat it endlessly. In all these

cases we have illustrations of the fundamental principle

of emphasis by repetition.

After a time the savage will get tired of his little

musical phrase and will invent another and often

this new phrase will be at a new pitch so as to bring

into play as many new notes as possible. Why?

Because his throat muscles and his perceptive faculties

are wearied by the constant repetition.

Is not this exactly the principle of the second

subject of the classical sonata, which is in a key which

brings into play as many new sounds as possible?

Then we have the principle of symmetry also

found in primitive music when the singer, having

got tired in turn with his new phrase, harks back to

the old one.

And so I could go on showing you how Beethoven

is but a later stage in the development of those

principles which actuated the primitive Teuton

when he desired to make himself artistically intelligible.

The greatest artist belongs inevitably to his country

as much as the humblest singer in a remote village—they

[13]

and all those who come between them

are links in the same chain, manifestations on their

different levels of the same desire for artistic expression,

and, moreover, the same nature of artistic

expression.

I am quite prepared for the objection that nationalism

limits the scope of art, that what we want

is the best, from wherever it comes. My objectors

will probably quote Tennyson and tell me

that “We needs must love the highest when we see

it” and that we should educate the young to appreciate

this mysterious “highest” from the beginning.

Or perhaps they will tell me with Rossini that they

know only two kinds of music, good and bad. So

perhaps we had better digress here for a few moments

and try to find out what good music is, and

whether there is such a thing as absolute good music;

or even if there is such an absolute good, whether

it must not take different forms for different hearers.

Myself, I doubt if there is this absolute standard

of goodness. I think it will vary with the

occasion on which it is performed, with the period at

which it was composed and with the nationality of

those that listen to it. Let us take examples of

each of these—firstly, with regard to the occasion.

The Venusberg music from Tannhäuser is good

music when it comes at the right dramatic moment

in the opera, but it is bad music when it is played

on an organ in church. I am sorry to have to tell

you that this is not an imaginary experience. A

waltz of Johann Strauss is good music in its proper

[14]

place as an accompaniment to dancing and festivity,

but it would be bad music if it were interpolated

in the middle of the St. Matthew Passion. And

may we not even say that Bach’s B minor Mass would

be bad music if it were played in a restaurant as

an accompaniment to eating and drinking?

Secondly, does not the standard of goodness vary

with time? What was good for the 15th Century

is not necessarily good for the 20th. Surely each

new generation requires something different to satisfy

its different ideals. Of course there is some

music that seems to defy the ravages of time and to

speak a new message to each successive generation.

But even the greatest music is not eternal. We can

still appreciate Bach and Handel or even Palestrina,

but Dufay and Dunstable have little more than an

historical interest for us now. But they were

great men in their day and perhaps the time

will come when Bach, Handel, Beethoven, and

Wagner will drop out and have no message left for

us. Sometimes of course the clock goes round full

circle and the 20th century comprehends what had

ceased to have any meaning for the 19th. This is

the case with the modern revival of Bach after nearly

one hundred and fifty years of neglect, or the modern

appreciation of Elizabethan madrigals. There

may be many composers who have something genuine

to say to us for a short time and for that short

time their music may surely be classed as good. We

all know that when an idiom is new we cannot detect

[15]

the difference between the really original mind

and the mere imitator. But when the idiom passes

into the realm of everyday commonplace then and

then only we can tell the true from the false. For

example, any student at a music school can now

reproduce the tricks of Debussy’s style, and therefore

it is now, and only now, that we can discover whether

Debussy had something genuine to say or whether

when the secret of his style becomes common property

the message of which that style was the vehicle

will disappear.

Then there is the question of place. Is music

that is good music for one country or one community

necessarily good music for another? It is true

that the great monuments of music, the Missa

Papae Marcelli, or the St. Matthew Passion, or the

Ninth Symphony, or Die Meistersinger, have a

world wide appeal, but first they must appeal to the

people, and in the circumstances where they were

created. It is because Palestrina and Verdi are essentially

Italian and because Bach, Beethoven and

Wagner are essentially German that their message

transcends their frontiers. And even so, the St.

Matthew Passion, much as it is loved and admired in

other countries, must mean much more to the German,

who recognizes in it the consummation of all

that he learnt from childhood in the great traditional

chorales which are his special inheritance.

Beethoven has an universal meaning, but to the

German, who finds in it that same spirit exemplified

[16]

in its more homely form in those Volkslieder which

he learnt in his childhood, he must also have a specialized

meaning.

Every composer cannot expect to have a world-wide

message, but he may reasonably expect to have

a special message for his own people and many

young composers make the mistake of imagining

they can be universal without at first having been

local. Is it not reasonable to suppose that those

who share our life, our history, our customs, our

climate, even our food, should have some secret to

impart to us which the foreign composer, though

he be perhaps more imaginative, more powerful,

more technically equipped, is not able to give us?

This is the secret of the national composer, the

secret to which he only has the key, which no foreigner

can share with him and which he alone is

able to tell to his fellow countrymen. But is he

prepared with his secret? Must he not limit himself

to a certain extent so as to give his message its

full force? For after all it is the millstream forcing

its way through narrow channels which gathers

strength to turn the water-wheel. As long as composers

persist in serving up at second hand the externals

of the music of other nations, they must not

be surprised if audiences prefer the real Brahms,

the real Wagner, the real Debussy, or the real

Stravinsky to their pale reflections.

What a composer has to do is to find out the

real message he has to convey to the community and

say it directly and without equivocation. I know

[17]

there is a temptation each time a new star appears

on the musical horizon to say, “What a fine fellow

this is, let us try and do something like this at home,”

quite forgetting that the result will not sound at

all the same when transplanted from its natural soil.

It is all very well to catch at the prophet’s robe, but

the mantle of Elijah is apt, like all second-hand

clothing, to prove the worst of misfits. How is the

composer to find himself? How is he to stimulate

his imagination in a way that will lead him to voicing

himself and his fellows? I think that composers

are much too fond of going to concerts—I am

speaking now, of course, of the technically equipped

composer. At the concert we hear the finished

product. What the artist should be concerned with

is the raw material. Have we not all about us

forms of musical expression which we can take and

purify and raise to the level of great art? Have

we not all around us occasions crying out for music?

Do not all our great pageants of human beings require

music for their full expression? We must

cultivate a sense of musical citizenship. Why should

not the musician be the servant of the state and build

national monuments like the painter, the writer, or

the architect?

“Come muse, migrate from Greece and Ionia,

Cross out please those immensely overpaid accounts,

That matter of Troy and Achilles’ wrath, and Æneas’, Odysseus’ wanderings,

Placard ‘removed’ and ‘to let’ on the rocks of your snowy Parnassus,

[18]

Repeat at Jerusalem, place the notice high on Jaffa’s gate and on Mount Moriah,

The same on the walls of your German, French and Spanish castles, and Italian collections,

For know a better, fresher, busier sphere,

A wide, untried domain awaits, demands you.”

Art for art’s sake has never flourished among the

English-speaking nations. We are often called inartistic

because our art is unconscious. Our drama

and poetry have evolved by accident while we

thought we were doing something else, and so it will

be with our music. The composer must not shut

himself up and think about art; he must live with

his fellows and make his art an expression of the

whole life of the community. If we seek for art we

shall not find it. There are very few great composers,

but there can be many sincere composers.

There is nothing in the world worse than sham

good music. There is no form of insincerity more

subtle than that which is coupled with great earnestness

of purpose and determination to do only the

best and the highest, the unconscious insincerity

which leads us to build up great designs which we

cannot fill and to simulate emotions which we can

only experience vicariously. But, you may say, are

we to learn nothing from the great masters? Where

are our models to come from? Of course we can

learn everything from the great masters and one of

the great things we can learn from them is their sureness

of purpose. When we are sure of our purpose

we can safely follow the advice of St. Paul “to prove

[19]

all things and to hold to that which is good.” But

it is dangerous to go about “proving all things”

until you have made up your mind what is good

for you.

First, then, see your direction clear and then by

all means go to Paris, or Berlin, or Peking if you

like and study and learn everything that will help

you to carry out that purpose.

We have in England today a certain number of

composers who have achieved fame. In the older

generation Elgar and Parry, among those of middle

age Holst and Bax, and of the quite young Walton

and Lambert. All these served their apprenticeship

at home. There are several others who

thought that their own country was not good enough

for them and went off in the early stages to become

little Germans or little Frenchmen. Their names I

will not give to you because they are unknown even

to their fellow countrymen.

I am told that when grape vines were first cultivated

in California the vineyard masters used to try

the experiment of importing plants from France or

Italy and setting them in their own soil. The result

was that the grapes acquired a peculiar individual

flavour, so strong was the influence of the

soil in which they were planted. I think I need

hardly draw the moral of this, namely, that if the

roots of your art are firmly planted in your own soil

and that soil has anything individual to give you,

you may still gain the whole world and not lose

your own souls.

[23]

II

SOME TENTATIVE IDEAS ON THE ORIGINS OF MUSIC

In considering the national aspects of music

we ought to think of what causes our inspiration

and also to whom it is to be addressed, that is to

say, how far should the origins of music be national,

how far should the meaning of music be national?

And perhaps before we go on to this we ought to

diverge a little bit and try and find out why it is

we want music at all in our lives.

What is the origin of that impulse to self-expression

by means of sound? We could possibly

trace back painting, poetry and architecture to an

utilitarian basis. I am not saying that this is so,

but the argument can be put forward. Now the

great glory of music to my mind is that it is absolutely

useless. The painter is bound by the same

medium whether he is painting a great landscape

or whether he is touching up the weather-stains on

his front gate. Language is the medium both of

“Paradise Lost” and of an auctioneer’s catalogue.

But music subserves no utilitarian purpose; it is

the vehicle of emotional expression and nothing else.

[24]

Why then do we want music? Hubert Parry in

his “Art of Music” writes, “It is the intensity of the

pleasure or interest the artist feels in what is actually

present to his imagination that drives him to

utterance. The instinct of utterance makes it a

necessity to find terms which will be understood by

other beings.”

Let us try to find out what is the exact process of

the invention and making of music.

Music is only made when actual musical sounds

are produced, and here I would emphasize very

strongly that the black dots which we see printed

on a piece of paper are not music; they are simply

a rather clumsy device invented by composers; a

series of conventional signs to show to those who

are not within hearing distance how they may with

the necessary means at their command reproduce

the sounds imagined by the composer.

A sheet of printed music is like a map where you

see a series of conventional signs, by which the skilled

map reader will know that the road he is on will

go north or south, that at one moment he will go

up a steep hill and that at another he will cross

a river by a bridge. That this town has a church,

and that that village has an inn. Or to use another

simile, heard music has the same relation to the

printed notes as a railway journey has to a time

table. But the printed notes are no more music

than the map is the country which it represents or

the time table the journey which it indicates.

We may imagine that in primitive times—and

[25]

indeed it still happens when someone sits down at

the pianoforte and improvises—the invention and

production of sound may have been simultaneous,

that there was no differentiation between the performer

and the composer. But gradually specialization

must have set in; those who invented music

became separated from those who performed it,

though of course till the invention of writing the

man who invented a tune had to sing it or play it

himself in order to communicate it to others.

Those others, if they were incapable of inventing

anything for themselves, but were desirous, as I believe

everyone is, of artistic self-expression, would

learn that tune and sing it and thus the differentiation

between composer and performer came about.

What is the whole process, starting with the

initial invention of music and leading on to the

final stage when the sounds imagined by the composer

are actually heard on those instruments or

voices for which he designed them? What should

be the object which the performer has in view when

he translates these imaginings into actual sound?

And what should be the object of the composer

when he invents music?

We all, whether we are artists or not, experience

moments when we want to get outside the limitations

of ordinary life, when we see dimly a vision

of something beyond. These moments affect us

in different ways. Some people under their influence

want to do a great or a kind or an heroic deed;

some people want to go and kill something or fight

[26]

somebody; some people go and play a game or just

walk it off; but those whom we call artists find the

desire to create beauty irresistible. For painters

it takes the form of idealizing nature; for architects

the beauty of solid form; for poets the magic of ordered

words, and for composers the magic of ordered

sound. Now it is not enough to feel these things;

the artist wants to communicate them as well, to

crystallize these vague imaginings into, as I have

already said, ordered sound, clear and intelligible;

and to do this he must make a synthesis between

the thing to be expressed and the means of expression.

Thus there has arisen the technical side of

music. Musical instruments have been devised

which will translate these ideas in the most sensitive

manner possible; artists spend years discovering how

to get the best results from these instruments and

composers, of course, have to study how to translate

their ideas into the terms of the means at their command.

And first of all the composer has, as I have

said, to devise a series of dots and dashes which will

explain, it must be confessed, in a very inadequate

manner, the pitch, the duration, the intensity, and

to a certain extent the quality of the sounds he

wishes the performer to produce. The composer

starts with a vision and ends with a series of black

dots. The performer’s process is exactly the reverse;

he starts with the black dots and from these

has to work back to the composer’s vision. First

he must find out the sounds that these black dots

represent and the quicker he can get over this

[27]

process the sooner he will be able to get on to something

more important. Therefore though a good

sight reader is not necessarily a good musician, it is

very useful for a musician to be a good sight reader.

Then the performer has to learn how best to make

these sounds. Here he is partly dependent, of

course, on the instrument maker, but it is here that

vocal and instrumental technique have their use.

Then he must learn to view any series of these black

dots both as a whole and in detail and to discover

the relation of the parts to the whole, and it is under

this heading that I would place such things as phrasing,

sense of form and climax—what we generically

call musicianship. When he has mastered these he

is ready to start and reproduce the composer’s vision.

Then, and then only, is he in a position to find out

whether there is any vision to reproduce.

Thus we come round full circle: the origin of

inspiration and its final fruition should be one and

the same thing.

How are we to find out whether music as a whole,

and especially the music of our own country, has a

national basis? Or perhaps we may go further still

and ask ourselves whether there is any sanction for

the art of music at all, and if so, how we are to discover

it. I suppose that most of you to whom I am

speaking are studying music—some of you perhaps

are teaching it and you find that at present your

time is, quite rightly, largely occupied with the technical

aspect of music, with the means rather than

with the end. Do you not ask yourselves sometimes

[28]

what is the end? Or perhaps I should put it better

by saying, what is the beginning? You can hardly

expect a gardener to be able to cultivate beautiful

flowers in a soil which is so barren that no wild

flowers will grow there. Must we not presuppose

that there must be wild flowers of music before we

occupy ourselves with our hydrangeas and Gloire

de Dijon roses? Before the student undertakes the

task of technical training he should satisfy himself

that his art is something inborn in man. He should

try and imagine whether the absolutely unsophisticated

though naturally musical man—one who has

no learning and no contact with learning, one who

cannot read or write and thus repeat anything

stereotyped by others, one who is untravelled and

therefore self-dependent for his inspiration, one in

fact whose artistic utterance will be entirely spontaneous

and unself-conscious—whether such a one

would be able to invent any form of music, and if

so whether it would be at all like the music which

we admire. “Ought not I,” he may say, “to expect it

to illustrate in embryonic form those principles

which I find in the music of the great masters?

Unless I can imagine such a man surely this great

art of music can be nothing but a house with

no foundation, a sort of fool’s paradise, a mirage

which will disappear before the first touch of real

life.”

In fact if we did not know from actual experience

that there was such a thing as folk-song we should

have to imagine it theoretically.

[29]

But we do find the answer to this enquiry in real

fact. The theoretical folk-singer has been discovered

to be an actuality. We really do find these

unlettered, unsophisticated and untravelled people

who make music which is often beautiful in itself

and has in it the germs of great art.

Some people express surprise and even polite disbelief

in the idea that people who have never seen

a pianoforte or had any harmony lessons and do not

even know what a dominant or consecutive 5th is

should be able to invent beautiful music: they either

shut their ears and declare that it is not really beautiful

but “only sounds so,” or they declare that these

singers must have “heard it somewhere.” Perhaps

you know the story of the missionary who, hearing

some savages chanting this rhythm

,

which after all is a very primitive one and very

likely to be found among unsophisticated people,

expressed his delight in discovering, as he thought,

that Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” had penetrated to

even these benighted regions. Or to give an example

which came under my own notice. A distinguished

English musician could not be persuaded

to believe that a countryman who could not even

read could possibly sing “correctly” in the Dorian

mode. He might as well have expressed surprise

with M. Jourdain at being able to speak prose.

,

which after all is a very primitive one and very

likely to be found among unsophisticated people,

expressed his delight in discovering, as he thought,

that Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” had penetrated to

even these benighted regions. Or to give an example

which came under my own notice. A distinguished

English musician could not be persuaded

to believe that a countryman who could not even

read could possibly sing “correctly” in the Dorian

mode. He might as well have expressed surprise

with M. Jourdain at being able to speak prose.

The truth is, of course, that these scientific expressions

are not arbitrary rules, but are explanations of

phenomena. The modal system, for example, is

simply a tabulation by scientists of the various methods

[30]

in which it is natural for people to sing. Again,

nobody invented sonata form; it is merely a theoretical

explanation of the mould into which people’s

musical thoughts have naturally flowed. Therefore

far from expressing surprise at a folk-song being

beautiful we ought to be surprised if it were not

so, for otherwise we might doubt the authenticity of

our whole canon of musical beauty.

Nevertheless the notion that folk-music is a degenerate

version of what we call composed music

dies hard, so perhaps I had better say a little

more about it. If this were really so, if folk-song

were only half-remembered relics of the composed

music of past centuries, should we not be able to

settle the matter by going to our museums and looking

through the old printed music? We shall find

there nothing remotely resembling the traditional

song of our country except, of course, such things

as the deliberate transcriptions of the popular melodies

in the “Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.”

I cannot see why it should not be equally natural

to presuppose an aptitude for singing in the natural

man as an aptitude for speaking; indeed, singing

of a primitive kind may be supposed to come before

speaking, just as emotion is something more primitive

than thought, and the indeterminate howls

which travellers tell us savages make to accompany

dances or ceremonies in which they are emotionally

excited may be supposed to be the beginnings of

music. However, the difference between real music

and mere sound depends on the fact of definitely

[31]

sustained notes with definite relations to each other.

Some people hold that this definition of sounds can

only have arisen after the invention of the pipe or

some other primitive musical instrument; but I

shall be able to give you personal evidence to the

contrary. I have no doubt myself that song is the

beginning of music and that purely instrumental

music is a later development. Song, then, I believe,

is nothing less than speech charged with emotion.

The German words sagen and singen were in early

times interchangeable and to this day a country

singer will speak of “telling” you a song, not of

singing it. Indeed the folk-singer (of course I am

speaking of England only, the only place of which

I have personal knowledge), the English folk-singer,

seems unable to dissociate words and tune:

if he has forgotten the words of a song he is very

seldom able to hum you the tune and if you in your

turn were to sing the words he knew to a different

tune he would be satisfied that you knew the song,

and I believe the same is true of dance tunes. A

country musician, so Cecil Sharp relates, took it for

granted that when his hearers had got the tune of

a dance they would be able to perform the dance

as well.

The personal evidence I will give you is as follows.

I was once listening to an open air preacher.

He started his sermon in a speaking voice, but as he

grew more excited the sounds gradually became

defined, first one definite note, then two, and finally

a little group of five notes.

[32]

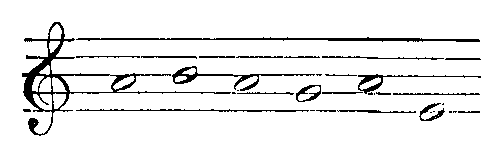

The notes being a, b, a, g, a, with an occasional

drop down to e.

It seemed that I had witnessed the change from

speech to song in actual process. The increased

emotional excitement had produced two results,

definition and the desire for a decorative pattern.

Perhaps I went too far in calling this song, perhaps

I should call it the raw material of song. I will

now give you examples of actual folk-songs built

on this very group of three notes.

(1) “Down in yon forest” (1st phrase)

(2) “Bushes and Briars” (1st phrase)

These are what we call the stock phrases of folk-song

which play an important part in folk-music

just as the stock verbal phrase plays an important

part in ballad poetry. There is a good practical

reason for these stock phrases. Any of you who

are writers, whether you are writing a magazine

article or a symphony, know that the great difficulty

is how to start, and the stock phrase solved this difficulty

with the ballad maker—so nine out of ten

[33]

ballads start with some common phrase such as “As

I walked out” or “It is of a” or “Come all you” and

so on. In the same way we find a common opening

to many folk-tunes, and this opening would naturally

be a variant of some musical formula which

comes naturally to the human voice. Now let us

examine this little phrase again. Can not we suppose

that our reciter in still greater moments of

excitement will feel inclined to add to and embellish

his little group of notes? Embellishment, we all

know, is a natural consequence of heightened emotion,

and it is a good criterion of the more ornamental

phrases in a composer’s work to make up

our minds whether they are the result of an emotional

impulse or whether they are meaningless

ornament. Take, for example, the cadenza-like

passages in the slow movement of Brahms’ Clarinet

Quintet and compare them with the flourishes, say,

in a Vieuxtemps Concerto, or take the melismata

charged with feeling of which Bach was so fond

and compare them with the meaningless coloratura

of his contemporary Italian opera composers.

Increased emotional excitement leads to increase

of ornament so that our original phrase might

eventually grow perhaps into this;

which is as a matter of fact an actual phrase out of a

known folk-song. Here we have what we can call a

complete musical phrase.

[34]

The business of the ballad singer is to fit his music

to the pattern of a rhymed verse, usually a four-line

stanza with some simple scheme of rhyme; so our

melodic phrase has somehow to be developed to

cover the whole ground. I assume for the sake of

simplicity a single invention and will not discuss

here the possibility of communal invention. If the

singer is pleased with his initial little bit of melody

he will feel inclined to repeat it. Repetition is

one of the fundamentals of artistic intelligibility.

Hubert Parry in his chapter on primitive music

gives examples of savage music which consists of

nothing else but a simple melodic phrase repeated

over and over again. But supposing our ballad

singer finds that the verse he has to recite is like the

dream of Bottom the weaver in 8’s and 6’s. The

music which he has adapted to the first line will not

suit the second so something new will have to grow

out of the old to fit the shortened number of

syllables. This gives us a new fundamental of

musical structure, that of contrast. When he gets

to the third line he finds 8 syllables again and to his

great delight he finds he can use his first music that

had pleased him so once more. Here we have a

very primitive example of the formula A.B.A. which

in an infinite variety of forms may be said to govern

the whole of musical structure, whether we look for

it in a simple ballad, in the Ninth Symphony, or in

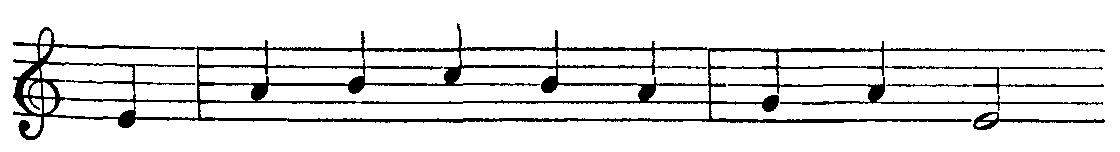

the Prelude to “Tristan.” Let us analyse an actual

example, “Searching for Lambs,” incidentally one

of the most beautiful of the English folk-songs.

[35]

The words of the first stanza, which after all will

largely determine the form of the music, are as

follows:

“As I went out one May morning

One May morning betime

I met a maid from home had strayed

Just as the sun did shine.”

The tune starts off with the elaborate form of our

stock phrase (A). Then comes a short line; so a

new phrase has to grow out of the old—a repetition

in fact a 3rd higher with a major 3rd this time and

an indeterminate ending, for we must not have any

feeling of finality yet (B).

Now for the third line. You might expect a mere

repetition of the first. But the third line of

the words is not an exact metrical repetition of

the first and moreover has a mid-rhyme. So some

variety in the music is suggested. We start off

with a repetition of line 2 which flows in a free

sequence (suggesting by its parallelism the mid-rhyme

(C).

Now for the last line. Here we obviously need

some allusion to the beginning to clench the whole.

So the sequential phrase is merely carried on, and

behold, we have our initial phrase once more complete,

growing naturally out of the sequential phrase

and, to complete all, 3 notes of Coda added to make

up the line (D).

What a wealth of unconscious art in so simple a

tune! All the principles of great art are here

[36]

exemplified: unity, variety, symmetry, development,

continuity.

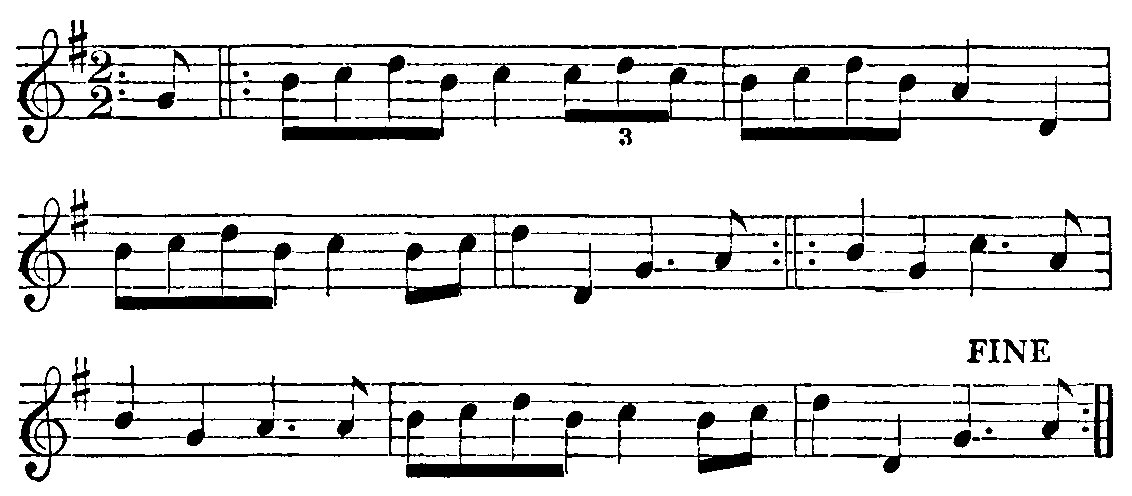

“Searching for Lambs”

(Printed by permission of Miss Karpeles and Messrs. Novello.)

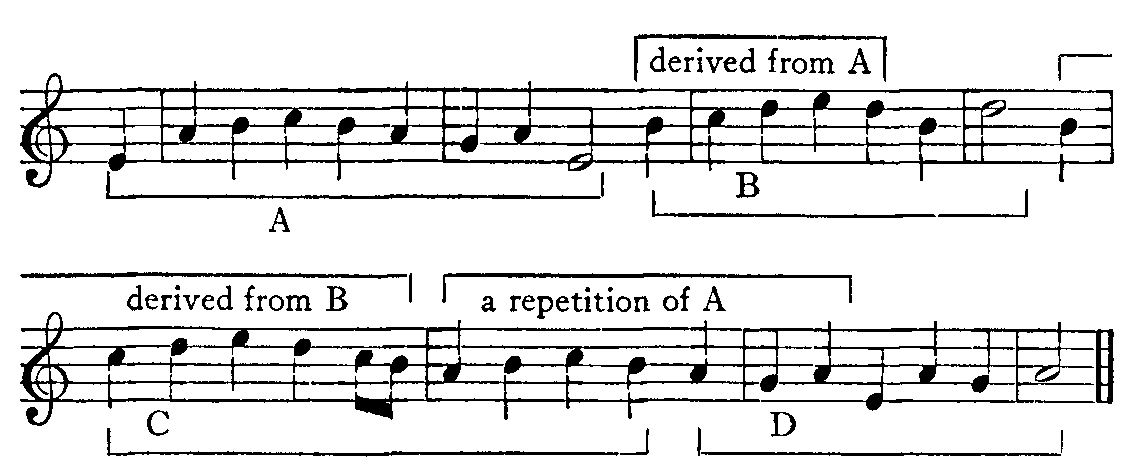

I will give you one more example of the growth

of a tune from the same root idea. This time the

3rd is major and the embellishing notes are consequently

differently placed.

I need not analyse this tune in detail, but the

same principles apply. The song is “The Water is

Wide.”

“The Water is Wide”

(Printed by permission of Miss Karpeles and Messrs. Novello.)

[39]

III

THE FOLK-SONG

We have now traced our course from the excited

speech phrase to the complete song

stanza. But we took no account of the element of

rhythm.

The preacher of whom I told you, when he got

excited established a definite relationship between

the pitch of the notes he used but not between their

duration, and it is this definite relationship between

the duration of successive musical sounds which we

call rhythm. Melody can exist apart from rhythm

just as rhythm can exist apart from melody. But

song can only be said to come into being when the

two are in combination. Rhythm, I suppose, grows

out of the dance, or out of the various bodily actions

which we do in our daily life such as walking, or

pulling on a rope. And even in speech we find that,

unconsciously, if we want to be very emphatic or to

impress something strongly on our memory we introduce

a rhythmical pattern into what we are saying.

Now in primitive times before there were newspapers

to tell us the news, history books to teach us

the past, and novels to excite our imagination, all

[40]

these things had to be done by the ballad singer who

naturally had to do it all from memory. To this

end he cast what he had to tell into a metrical form

and thus the ballad stanza arose. As a further aid

to memory and to add to the emotional value of

what he had to say he added musical notes to his

words, and it is from this that the ordinary folk-tune

of four strains arose. Folk music, you must always

remember, is an applied art. The idea of art for

art’s sake has happily no place in the primitive consciousness.

I have already told you how the country

singer is unable to dissociate the words and tune of

a ballad. Song then was to him the obvious means

of giving a pattern to his words. But this pattern

is influenced by another form of applied music, that

of the dance, the dance in which the alternation of

strong and weak accents and precision of time are

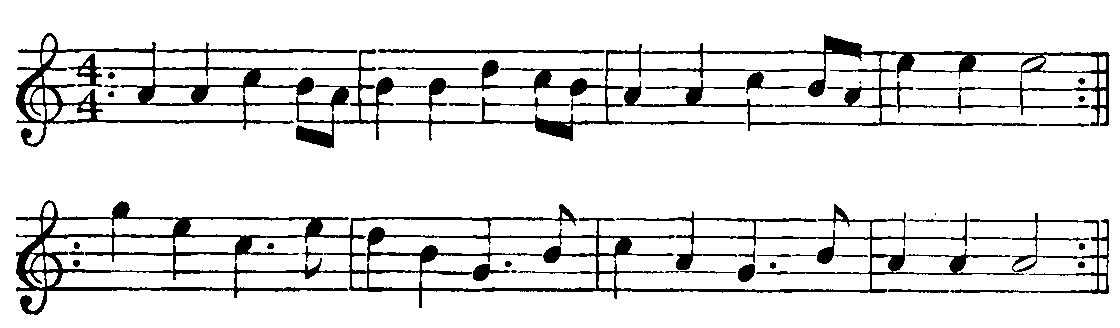

essential. Now let us take the dance tune “Goddesses”

as an example of the rhythmical element

applied to our initial formula. You will notice that

the form is less subtle than in the song tunes.

Regularity of pattern is essential to accompany the

moving feet of the dancers.

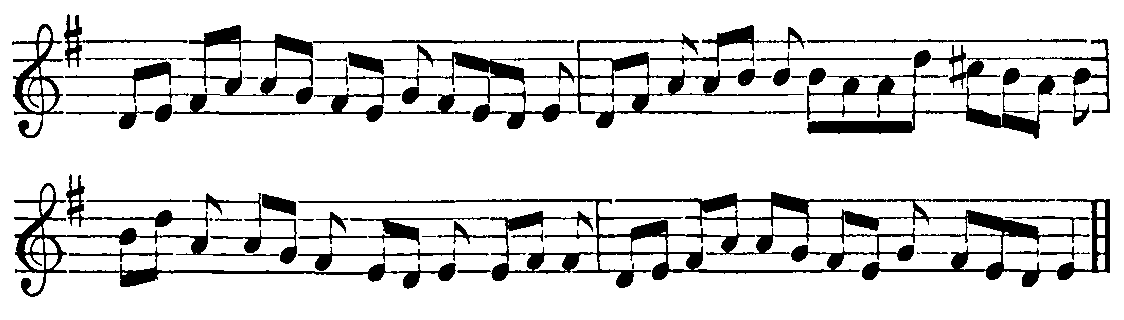

Dance Tune “Goddesses”

(Printed by permission of Miss Karpelese and Messrs. Novello.)

[41]

Next let me give you an example of a tune with

very much the same melodic formula in which the

rhythmical pattern is entirely governed by the

words, a carol tune, “The Holy Well.”

I have now tried to describe to you the folk-song,

but before I go any further I had better give you

some actual examples of what I mean by folk-song,

and try and persuade you that I am telling you not

of something clownish and boorish, not even something

inchoate, not of the half forgotten reminiscences

of fashionable music mouthed by toothless

old men and women, not of something archaic, not

of mere “museum pieces,” but of an art which

grows straight out of the needs of a people and for

which a fitting and perfect form, albeit on a small

scale, has been found by those people; an art which

is indigenous and owes nothing to anything outside

itself, and above all an art which to us today has

something to say—a true art which has beauty and

vitality now in the twentieth century. Let us take a

few typical examples of English folk-song: “The

Cuckoo,” “My Bonny Boy,” “A Sailor From the

Sea,” or “It’s a Rose-bud in June.”

Can we not truly say of these as Gilbert Murray

[42]

says of that great national literature of the Bible and

Homer, “They have behind them not the imagination

of one great poet, but the accumulated emotion,

one may almost say, of the many successive generations

who have read and learned and themselves

afresh re-created the old majesty and loveliness. . .

There is in them, as it were, the spiritual life-blood

of a people.”

A folk-song is at its best a supreme work of art,

but it does not say all that is to be said in music;

it is limited in its scope and this for various reasons.

(1) It is purely intuitive, not calculated. (2) It

is purely oral, therefore the eye does not help the

ear and, prodigious though the folk-singer’s memory

is, owing to the very fact that it has not been

atrophied by reading, it must be limited by the

span of what both the singer and hearer can keep

in their minds at one stretch. (3) It is applied

music, applied either to the words of the ballad or

the figure of the dance. (4) Folk-music, at all

events European folk-music, and I believe it is true

of all genuine folk-music, is purely melodic. These

limitations are not without corresponding advantages.

(a) The folk-singer, being un-selfconscious

and unsophisticated and bound by no prejudices or

musical etiquette, is absolutely free in his rhythmical

figures. If he has only five syllables to which to

sing notes and those syllables are of equal stress

he makes an unit or what in written music we

should call a bar of five beats (to put it into the

language of scientific music). If he is singing

[43]

normally in a metre of 6/8 and he wants to dwell on

one particular word he lengthens that particular

phrase to a metre of 9 beats. If he is accompanying

a dance and the steps of the dance demand it he will

lengthen out the notes to just the number of long

steps, regardless of the feelings of the poor collector

who is afterwards going to come and try and reduce

his careless rapture to terms of bars, time signatures,

crotchets and quavers. We are apt to imagine that

bars of five and seven, irregular bar-lengths and so

on are the privilege of the modernist composer:

he is probably only working back to the freedom

enjoyed by his ancestor. (b) To pack all one has

to say into a tune of some sixteen bars is a very

different proposition from spreading oneself out into

a symphony or grand opera, especially when these

sixteen bars have to be repeated over and over again

for a ballad of some twenty verses. We have often

experienced music which at first seemed attractive

but of which we wearied after repetition. The

essence of a good folk-tune is that it does not show

its full quality till it has been repeated several times,

and I think a great deal of the false estimates of folk-melodies

which are current are due to the fact that

they are read through once, or possibly hummed

through without their words, or worse still strummed

through once on the piano and not subjected to the

only fair test, that of being sung through with their

words.

And now as regards what I may call the vertical

limitation of the folk-song; the fact that it is purely

[44]

melodic. Modern music has so accustomed us to

harmony that we find it difficult to realize that there

can be such a thing as pure melody built up without

any reference to harmony. It is true of course that

we all whistle and hum tunes without harmony;

nevertheless we are all the time unconsciously imagining

an harmonic basis. Many of our most

popular tunes would be meaningless unless in the

back of our minds we supplied their harmonies.

Harmonic music, at all events during the 18th

and 19th Centuries, presupposed the existence of

two modes only, the major and the minor, with all

their harmonic implications of the perfect cadence,

the half close, the leading note and so on, so as to

give points of repose, points of departure and the

like. But in purely melodic music an entirely new

set of considerations come into being. The major

and minor modes hardly ever appear in true melodic

music, but it must be referred to other systems,

chiefly the Dorian mode, the Mixolydian mode and

the Ionian mode, this last having of course the same

intervals as the major mode, but otherwise quite

distinct.

I do not propose to give you a disquisition on the

modes; that would be quite outside the scope of

these lectures, but I want to say just two things.

The epithet “ecclesiastical” which has been applied

to these modes has led to unfortunate misunderstandings.

Because a folk-song can be referred

to one of these “ecclesiastical” modes it is often

imagined that folk-song derives from church music.

[45]

I believe that it is just the other way round, namely,

that church music derives from folk-music. I shall

have more to say about this in a subsequent chapter.

The only thing which the plain-song of the church

and the folk-song of the people have now in common

is that they can sometimes be referred to the

same modal system because they are both purely

melodic. It is surely hard to imagine that such a

melody as “The Cobbler” can be derived from, say,

“Jesu Dulcis Memoria” because they are both in the

Dorian mode. You might as well say that the

“Preislied” derives from the finale of the Fifth Symphony

because they are both in C Major.

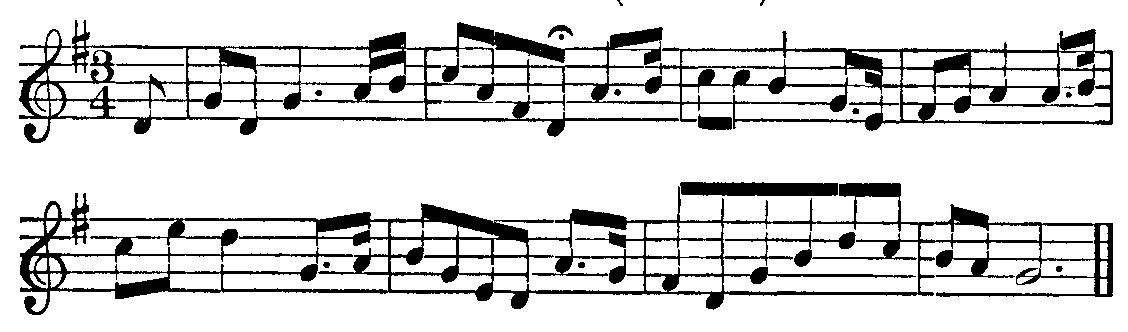

“Jesu Dulcis Memoria”

“The Cobbler”

[46]

The other point I want to make is this. It is not

correct to refer to the modes as “old,” or of pure

modal harmony as “archaic.” Real archaic harmony

is never modal. When harmony grew out of

the Organum, composers found that they could not

work in the modes with their new-found harmonic

scheme and they began to alter the modal melodies

to give them the necessary intervals with which they

could work. The harmony of Palestrina and his

contemporaries is therefore not purely modal; this

was reserved for the 19th century. As I have said,

folk-song is pure melody without an harmonic substructure,

but when modal melodies began to swim

into the ken of composers, the first being probably

the nationalists of 19th Century Russia, they began

to suggest to them all sorts of harmonic implications.

Up to that time harmony was always supposed to be

considered as being built up from the bass. The

Russian nationalists, perhaps owing to the fact that

they were half amateur, evidently preferred to build

their harmony from the melody downwards. We

find this neo-modal harmony prevalent throughout

Moussorgsky’s “Boris.” The lead was taken up by

Debussy and the French contemporaries, some of the

modern Italians and the modern English. It seems

however to have passed by the Germans, possibly

because their folk-songs have become tinged with

harmonic considerations. Debussy’s “Sarabande” is

a good example of pure modal harmony, as are the

cadences in the minuet from Ravel’s “Sonatine.”

I find it difficult to see what there is “archaic”

[47]

about these. If you look at real archaic harmony,

going back even as far as Josquin and Dunstable,

you will find nothing like it.

Some people are much worried about what they

call the “cult of archaism.” They are upset at all

this “borrowing” which is going on among composers

and they are filled with indignation, but as

far as I can make out on moral rather than on

aesthetic grounds.

In an article called “The Cult of Archaism” a recent

writer says, “In the writing of synthetic folk-music

we have to deal with a form of equivocation

which is probably quite as serious, being more insidious

than the wholesale acquisition of folk-melody.

It is reasoned apparently that though they

may be musically unworthy to borrow on an extensive

scale, the situation can be redeemed by writing

artificial folk-melodies and presenting them as original

themes. A student possessing the most elementary

inventive ability can effect work of that

kind without limit; it requires practically no skill

and very little imagination.”

This seems to me to be nothing more or less than

a protest by the “trade,” and the “trade” as you

know always adopt a high moral attitude when their

profits are being interfered with. A brewer will be

extremely annoyed if, when he has spent time,

money and skill on producing beer, he finds that

someone has set up a free water tap just outside his

house. So, when the members of the musical trade

who have learnt how to construct melodies at great

[48]

expense with all the latest devices and improvements

find a composer writing a tune, not based on all

these expensive models but built up on the natural

music of his own people, they of course feel vexed:

the fellow is not playing the game, in fact he is a

blackleg. Which method results in the most beautiful

music is not allowed to affect the issue. It is

merely a trade question, a matter in going outside

the regulations of the guild.

Contrast with this a recent writer on Moussorgsky:

“His invented themes recall those of popular art and

it is to the phenomenon of ‘integration’ that he

owes his appealing originality.” Or as Mr. Kurt

Schindler recently said about the same composer, “It

all depends on whether it is done with love.”

“Integration” and “love.” These are the two key

words. The composer must love the tunes of his

own country and they must become an integral part

of himself. There are, of course, hangers-on of the

folk-song movement who want to be “in the swim”

and think they can do so by occasionally superimposing

a modal cadence, or what they imagine to

be a country dance rhythm, on to their cosmopolitan

style compounded of every composer from Wagner

to Stravinsky. These people, of course, have sinned

against the light: whether they are also morally

reprehensible does not seem to me to matter.

At the risk of wearying you I want to repeat that

originality is not mere novelty. In the article I

have already quoted Haydn is referred to as occasionally

not taking the trouble to say something of

[49]

his own. And is the same true of Beethoven when

he used a theme from Mozart for his Eroica Symphony?

A composer at white heat of invention

does indeed not “trouble to say something of his

own”; he knows instinctively what is the inevitable

theme for his purpose. Music does not grow out

of nothing, one idea leads to another and the test of

each idea is, not whether it is “original” but whether

it is inevitable.

I should like to quote you the following lately

written in the London Mercury: “The best composers

store up half-fledged ideas in the works of

others and make use of them to build up perfect

edifices which take on the character of their maker

because they are ideas which appeal to that special

mind.”

[53]

IV

THE EVOLUTION OF THE FOLK-SONG

The fact that folk-music is entirely oral and

is independent of writing or print has important

and far-reaching results. Scholars are too

apt to mistrust memory and to pin their faith on

what is written. They little realize how reading

and writing have destroyed our memory. Cecil

Sharp gives amazing examples from his own experience

of the power of memory among those who

cannot read or write. The scholars look upon all

traditional versions of a poem or song as being necessarily

“corrupt”—as a matter of fact corruptions are

much more likely to creep in in the written word

than in the spoken. Any alteration in a written

copy is likely to be due to carelessness or ignorance

whereas when we do find variations in versions of

traditional words and music these are as often as not

deliberate improvements on the part of later reciters

or singers.

There is no “original” in traditional art, and there

is no particular virtue in the earliest known version.

Later versions are as likely as not developments and

not corruptions.

There is a well known saying of the folk-lorist

[54]

Grimm that “a folk-song composes itself.” Others

replied to this with the common-sense view that in

the words of our English critic I have already quoted

with regard to the symphony, “It only takes one man

to make a folk-song.” Böhme, in the Introduction

to his “Alt-deutsches Liederbuch,” says, “First of all

one man sings a song, then others sing it after him,

changing what they do not like.” In these words

we have the clue to the evolution of the folk-song.

Let me quote you also from Allingham’s “Ballad

Book.” “The ballads owe no little of their merit

to the countless riddlings, siftings, shiftings, omissions

and additions of innumerable reciters. The

lucky changes hold, the stupid ones fall aside. Thus

with some effective fable, story, or incident for its

soul and taking form from a maker who knew his

business, the ballad glides from generation to generation

and fits itself more and more to the brain and

ear of its proper audience.”

According to Gilbert Murray even a written book

could be ascribed in primitive times to a communal

authorship. Thus, the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” are

both the products of a long process of development.

It is interesting to note that almost up to the time

of the invention of printing more trust was placed

in the spoken than the written word. The Greek

word Logos means a living thing, the spoken word,

not the vague scratchings which in early times served

for writing. Even in A.D. 135 it was possible for a

historian to say, “I did not think I could get so much

[55]

profit from the contents of books as from the utterings

of the living and abiding voice.”

Compare this with what we now realize of the

strength and accuracy of oral tradition.

The book, as Professor Murray says, “must needs

grow as its people grew. As it became part of the

people’s tradition, a thing handed down from antiquity

and half sacred, it had a great normal claim

on each new generation of hearers. They are ready

to accept it with admiration, with reverence, with

enjoyment, provided only that it continued to make

some sort of tolerable terms with their tastes....

The book became a thing of tradition and grew with

the ages.”

Thus you see it is possible to ascribe communal

authorship even to a book. To quote Professor

Murray once again—“The ‘Iliad’ and ‘Odyssey’ represent

not the independent invention of one man,

but the ever-moving tradition of many generations

of men.” If this be true of the book, how much

more so of purely oral music and poetry.

Cecil Sharp, in his book on English folk-song,

argues strongly in favour of the communal authorship

of traditional music and poetry, but it must be

noted that he does not claim a communal origin.

He writes, “The folk-song must have had a beginning

and that beginning must have been the work

of an individual. Common sense compels us to

assume this much, otherwise we should have to

predicate a communal utterance that was at once

[56]

simultaneous and unanimous. Whether or not the

individual in question can be called the author is

another matter altogether. Probably not, because

the continual habit of ‘changing what they do not

like’ must in course of time ultimately amount to the

transference of the authorship from the individual

to the community.”

However, though the case for communal origin

cannot be proved yet I do not see how it can be

disproved. No one, so far as I know, insists on the

individual invention of the common words of our

language and travellers tell us of musical phrases

emanating from excited crowds of people spontaneously

and simultaneously.

But I will grant for the sake of argument that the

separate phrases of any folk-song you may like to

name were invented by some individual. I will not

go further than that because the “skilled ballad-maker”

of Halliwell could put musical phrases together

to form a tune just as he could put lines of

poetry together to form a ballad, and I have already

shown you how certain stock phrases, some of which

I have quoted, appear over and over again in folk-tunes,

just as the stock phrases “as I walked out,”

“lily-white hand” and so on, appear over and over

again in ballad poetry. But would it be right to

call the ballad-maker who has strung these phrases

together so skillfully into a tune the author of that

tune? We will take it, however, for granted that

a folk-singer has invented a whole tune just as

Schubert invented a whole tune. When Schubert

[57]

invented a tune he made it known to his fellow-men

by writing it down; the primitive folk-singer

could only make his invention known by singing it

over to his hearers.

You will say, if that is all the difference between a

composed song and a folk-song there is not much to

choose between them. But it is on this apparently

small difference that the whole question of individual

as against communal authorship depends. If

you hear two or three singers sing the same song—say

by Schubert—they each will show slight differences

in what we call “interpretation” according to

their various temperaments, but these differences

can never become very wide because we are continually

referring back to the printed copy. But

supposing there was no printed copy, supposing

three of you whom I will call A, B and C learnt this

Schubert song, not from the printed copy, but from

the individual performances of the three singers I

have imagined and whom I will call D, E and F; that

is to say, A learnt the song from D, B learnt it from E

and C learnt it from F and then you three, A, B and

C, sang it to each other, adding of course your own

individual predilections—would there not be already

a very wide margin of difference?

Let me give you a homely example. There used

to be an army exercise called “messages” in which

the men were ranged in a row and an officer gave a

verbal message to the first man who passed it on to

the second, and so on to the end of the row; and the

man at the end of the row had to report to the officer

[58]

the message as he received it. Now you will understand

that the message often came out at the end

very different from what it went in at the beginning,

and this in spite of the fact that each man was trying

to be as accurate as possible.

Now this is what happens in the case of the folk-song,

with this added factor which makes for divergence—the

need for accuracy has disappeared. The

second singer who receives the song from the first is

at liberty, in the words of Böhme, to “change what

he does not like.”

This then is the evolution of the folk-song. One

man invents a tune. (I repeat that I grant this much

only for the sake of argument.) He sings it to his

neighbours and his children. After he is dead the

next generation carry it on. Perhaps by this time

a new set of words have appeared in a different

metre for which no tune is available. What more

natural than to adapt some already existing tune to

the new words? Now where will that tune be after

three or four generations? There will indeed by

that time not be one tune but many quite distinct

tunes, nevertheless, but all traceable to the parent

stem.

Now let us return a minute to our military

“messages.” It would often happen, of course, that

the message in the course of transmission became

hopelessly altered and indeed became nonsense when

finally delivered. You may say, is not this the same

with the folk-song? Are you not describing a

process of corruption and disintegration rather than

[59]

of growth and evolution? Let us remind ourselves

once again that the folk-song only lives by oral transmission,

that if it fails to be passed from mouth to

mouth it ceases to exist. Now to go back once more

to our soldiers. It might happen that by the time it

reached the middle of the line the message had

already become nonsense, but the soldier’s duty, as

you know, is not to reason why, but to pass on what

he heard, whatever he might think of its quality.

But a folk-singer is a free agent, there is no necessity

for him to pass on what he does not care about. Let

us suppose an example. John Smith sings a song

to two other men, William Brown and Henry Jones.

William Brown is a real artist and sees possibilities

in the tune and adds little touches to it that give it

an added beauty. Henry Jones is a stupid fellow

and forgets the best part of the tune and has to make

it up the best he can, or he leaves out just that bit

that gave the tune its individuality. Now what will

happen? William Brown’s version will live from

generation to generation while Henry Jones’ will die

with him. So you see that the evolution of the folk-song

is a real process of natural selection and survival

of the fittest.

Please forgive me if I return for a fourth time

to our row of soldiers. Who is the author of the

message in its final form as reported by the last soldier?

Not he, obviously, because he was only repeating

what he heard with possibly a few unconscious

alterations. Neither is the officer who invented

the original message, because we are supposing

[60]

that its final form is only the same in outline

and varies much in detail. Each of the soldiers had

a hand in it, it is a product of their united minds; in

fact it is a crude and rather ridiculous form of communal

authorship. The folk-song in its evolution

goes through exactly the same process, but as I have

already shown, in the folk-song it is a case of growth

and not of disintegration, of development, not of

corruption.

This then is the much discussed and often ridiculed

“communal theory” of folk-song. This is

what Grimm meant when he said, “A folk-song composes