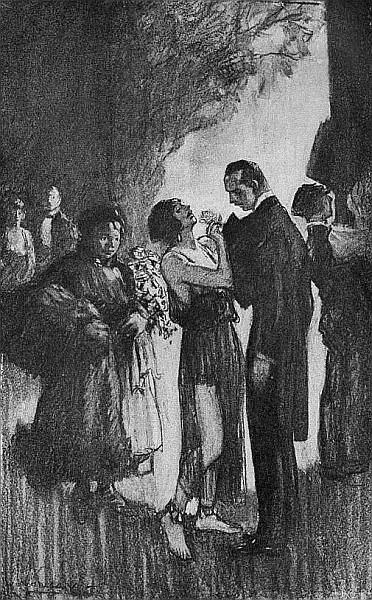

"So!" she whispered. "They will know from whom that rose

comes." Frontispiece.

"So!" she whispered. "They will know from whom that rose

comes." Frontispiece.See page 148.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Seven Conundrums

Date of first publication: 1923

Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim

Date first posted: August 7, 2012

Date last updated: August 7, 2012

Faded Page ebook #20120810

This ebook was produced by: David T. Jones, woodie4, Al Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| Introduction | |

| PAGE | |

| The Compact | 3 |

| Conundrum Number One | |

| The Stolen Minute Book | 15 |

| Conundrum Number Two | |

| What Happened at Bath | 39 |

| Conundrum Number Three | |

| The Spider's Parlour | 97 |

| Conundrum Number Four | |

| The Courtship of Naida | 131 |

| Conundrum Number Five | |

| The Tragedy at Greymarshes | 167 |

| Conundrum Number Six | |

| The Duke's Dilemma | 205 |

| Conundrum Number Seven | |

| The Greatest Argument | 243 |

| "So!" she whispered. "They will know | |

| from whom that rose comes" | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

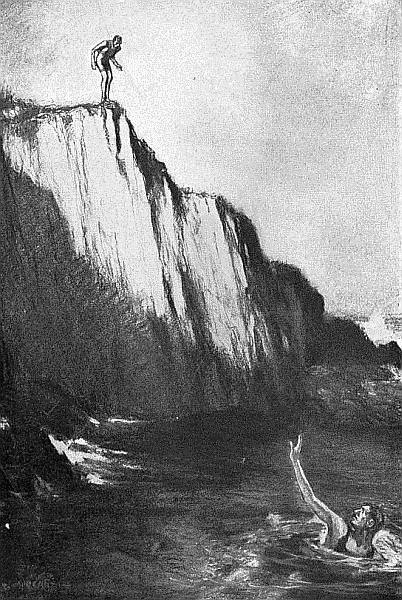

| There were shrieks from the women, and some of | |

| the men, amongst them myself, hurried towards | |

| the staircase | 65 |

| "Don't be a fool," I answered. "There's a | |

| submerged rock right across here" | 191 |

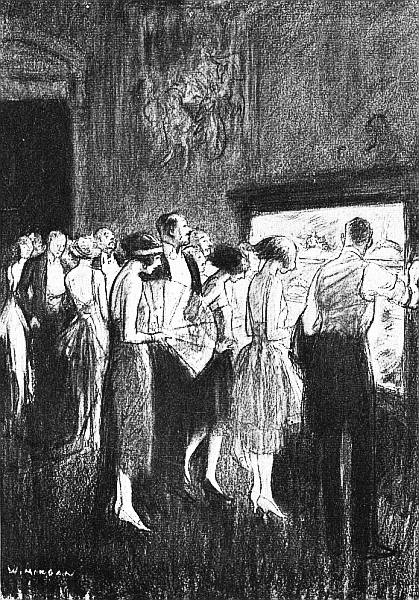

| There seemed to be an almost universal gasp of | |

| astonishment | 216 |

The wind, storming up from the sea, beat against the frail little wooden building till every rafter creaked and groaned. The canvas sides flapped and strained madly at the imprisoning ropes. Those hanging lamps which were not already extinguished swung in perilous arcs. In the auditorium of the frail little temporary theatre, only one man lingered near the entrance, and he, as we well knew, with sinister purpose. In the little make-up room behind the stage, we three performers, shorn of our mummer's disguise, presented perhaps the most melancholy spectacle of all. The worst of it was that Leonard and I were all broken up with trying to make the best of[Pg 4] the situation for Rose's sake, yet prevented by circumstances from altogether ignoring it.

"Seems to me we're in rather a tightish corner, Leonard," I ventured, watching that grim figure in the doorway through a hole in the curtain.

"First turn to the left off Queer Street," Leonard admitted gloomily.

Rose said nothing. She was seated in the one chair which went with the portable property, and her head had fallen forward upon her arms, which were stretched upon the deal table. Her hat, a poor little woollen tam-o'-shanter, was pushed back from her head. Her jacket was unfastened. The rain beat down upon the tin roof.

"I'd sell my soul for a whisky and soda," Leonard, our erstwhile humourist, declared wistfully.

"And I mine," I echoed, thinking of Rose, "for a good supper, a warm fire and a comfortable bed."

"And I mine," Rose faltered, looking up and dabbing at her eyes with a morsel of handkerchief, "for a cigarette."

[Pg 5]There was a clap of thunder. The flap of canvas which led to the back of the stage shook as though the whole place were coming down. We looked up apprehensively and found that we were no longer alone. A clean-shaven man of medium height, dressed in a long mackintosh and carrying a tweed cap in his hand, had succeeded in effecting a difficult entrance. His appearance, even at that time, puzzled us. His face was perfectly smooth, he was inclined to be bald, his eyes were unusually bright, and there was a noticeable curve at the corners of his lips which might have meant either humour or malevolence. We had no idea what to make of him. One thing was certain, however,—he was not the man an interview with whom we were dreading.

"Mephistopheles himself could scarcely have made a more opportune entrance," he remarked, as the crash of thunder subsided into a distant mutter. "Permit me."

He crossed towards us with a courteous little bow and extended a gold cigarette case, amply filled. Rose took one without hesita[Pg 6]tion and lit it. We also helped ourselves. The newcomer replaced the case in his pocket.

"I will take the liberty," he continued, "of introducing myself. My name is Richard Thomson."

"A very excellent name," Leonard murmured.

"A more than excellent cigarette," I echoed.

"You are the gentleman who sat in the three-shilling seats," Rose remarked, looking at him curiously.

Mr. Richard Thomson bowed.

"I was there last night and the night before," he acknowledged. "On each occasion I found with regret that I was alone."

No one likes to be reminded of failure. I answered a little hastily.

"You have established your position, sir, as a patron of our ill-omened enterprise. May I ask to what we are indebted for the honour of this visit?"

"In the first place, to invite you all to supper," was the brisk reply. "Secondly, to ask if I can be of any service in helping you to get rid of that bearded rascal Drummond, whom[Pg 7] I see hanging about at the entrance. And in the third place—but I think," he added, after a queer and oddly prolonged pause, "that we might leave that till afterwards."

I stared at him like a booby, for I was never a believer in miracles. The quiver on Rose's lips was almost pathetic, for like all sweet-natured women she was an optimist to the last degree. Leonard, I could see, shared my incredulity. The thing didn't seem possible, for although he was obviously a man of means, and although his manner was convincing and there was a smile upon his lips, Mr. Richard Thomson did not look in the least like a philanthropist.

"Come, come," the latter continued, "mine is a serious offer. Are you afraid that I shall need payment for my help and hospitality? What more could you have to give than the souls you proffered so freely as I came in?"

"You can have mine," Leonard assured him hastily.

"Mine also is at your service," I told him. "The only trouble seems to be to reduce it to a negotiable medium."

[Pg 8]"We will make that a subject of discussion later on," our new friend declared. "Mr. Lister," he added, turning to me, "may I take it for granted that you are the business head of this enterprise? How do you stand?"

I choked down the pitiful remnants of my pride and answered him frankly.

"We are in the worst plight three human beings could possibly find themselves in. We've played here for six nights, and we haven't taken enough money to pay for the lighting. We owe the bill at our lodgings, we haven't a scrap of food, a scrap of drink, a scrap of tobacco, a scrap of credit. We've nothing to pawn, and Drummond outside wants four pounds."

"That settles it," our visitor declared curtly. "Follow me."

We obeyed him dumbly. It is my belief that we should have obeyed any one helplessly at that moment, whether they had ordered us to set fire to the place or to stand on our heads. We saw Drummond go off into the darkness, gripping in his hand unexpected money, and followed our guide across the windy space[Pg 9] which led to the brilliantly lit front of the Grand Hotel, whose luxurious portals we passed for the first time. We had a tangled impression of bowing servants, an amiable lift man, a short walk along a carpeted corridor, a door thrown open, a comfortable sitting room and a blazing fire, a round table laid for four, a sideboard set out with food, and gold-foiled bottles of champagne. A waiter bustled in after us and set down a tureen of smoking hot soup.

"You needn't wait," our host ordered, taking off his mackintosh and straightening his black evening bow in the glass. "Miss Mindel, allow me to take your jacket. Sit on this side of the table, near the fire; you there, Cotton, and you opposite me, Lister. We will just start the proceedings so," he went on, cutting the wires of a bottle of champagne and pouring out its contents. "A little soup first, eh, and then I'll carve. Miss Mindel—gentlemen—your very good health. I drink to our better acquaintance."

Rose's hand shook and I could see that she was on the verge of tears. It is my belief that[Pg 10] nothing but our host's matter-of-fact manner saved her at that moment from a breakdown. Leonard and I, too, made our poor little efforts at unsentimental cheerfulness.

"If this is hell," the former declared, eyeing the chickens hungrily, "I'm through with earth."

"Drink your wine, Rose," I advised, raising my own glass, "and remember the mummers' philosophy."

Rose wiped away the tears, emptied her glass of champagne and smiled.

"Nothing in the world," she declared fervently, "ever smelt or tasted so good as this soup."

The psychological effect of food, wine, warmth and tobacco upon three gently nurtured but half-starved human beings became even more evident at a later stage in the evening. Its immediate manifestations, however, were little short of remarkable. For my part, I forgot entirely the agony of the last few weeks, and realised once more with complacent optimism the adventurous possibilities of our vagabond life. Leonard, with flushed cheeks,[Pg 11] a many times refilled glass, and a big cigar in the corner of his mouth, had without the slightest doubt completely forgotten the misery of having to try and be funny on an empty stomach to an insufficient audience. With a little colour in her cheeks, a smile once more upon her lips, and a sparkle in her grey eyes, Rose was once more herself, the most desirable and attractive young woman in the world as, alas! both Leonard and I had discovered. The only person who remained unmoved, either by the bounty he was dispensing or by the wine and food of which he also partook, was the giver of the feast. Sphinxlike, at times almost saturnine looking, his eyes taking frequent and restless note of us, his mouth, with its queer upward curve, a constant puzzle, he remained as mysterious a benefactor when the meal was finished as when he had made his ominous appearance behind the stage at the framework theatre. He was an attentive although a silent host. It was never apparent that his thoughts were elsewhere, and I, watching him more closely, perhaps, than the other two, realised[Pg 12] that most of the time he was living in a world of his own, in which we three guests were very small puppets indeed.

Cigars were lit, chairs were drawn around the fire, Rose was installed on a superlatively comfortable couch, with a box of cigarettes at her elbow, and her favourite liqueur, untasted for many weeks, at her side.

"Let me try your wits," our host proposed, a little abruptly. "Tell me your life history in as few words as possible. Mr. Lister? Tabloid form, if you please?"

"Clergyman's son, without a shilling in the family," I replied; "straight from the 'Varsity, where I had meant to work hard for a degree, to the Army, where after three and a half years of it I lost this,"—touching my empty left coat sleeve. "Tried six months for a job, without success. Heard of a chap who had made a concert party pay, realised that my only gifts were a decent voice and some idea of dancing, so had a shot at it myself."

"Mr. Cotton?"

"Idle and dissolute son of a wine merchant at Barnstaple who failed during the war,"[Pg 13] Leonard expounded; "drifted into this sort of thing because I'd made some small successes locally and didn't want to be a clerk."

"Miss Mindel?"

The girl shook her head.

"I am quite alone in the world," she said. "My mother taught music at Torquay and she died quite suddenly. I put my name down for a concert party, and in a way I was very fortunate," she added, glancing sweetly at Leonard and at me. "These two men have been so dear to me and I don't think it's any one's fault that we're such a failure. The weather's been bad, and people stay in their hotels and dance all the time now."

She held out a hand to each of us. She knew perfectly well how we both felt, and she treated us always just like that, as though she understood and realised the compact which Leonard and I had made. So we sat, linked together, as it were, while our host studied us thoughtfully, appreciating, without a doubt, our air of somewhat nervous expectancy. A fine sense of psychology guided him to the conviction[Pg 14] that we were in a properly receptive state of mind. The smile which had first puzzled us played once more upon his lips.

"And now," he said, "about those souls!"

Rose always insisted that she was psychic, and I have some faith myself in presentiments. At any rate, we both declared, on that Monday night before the curtain went up, that something was going to happen. Leonard had no convictions of the sort himself but he was favourably disposed towards our attitude. He put the matter succinctly.

"Here we are," he pointed out, "sold to the devil, body and soul, and if the old boy doesn't make some use of us, I shall begin to be afraid the whole thing's coming to an end. Five pounds a week, and a reserve fund for costumes and posters suits me very nicely, thank you."

"I don't think you need worry," I told him. "It doesn't seem reasonable to imagine that we've been sent to the slums of Liverpool for nothing."

[Pg 16]"Then there are those posters," Rose put in, "offering prizes to amateurs. I'm quite certain there's some method in that. Besides——"

She hesitated. We both pressed her to go on.

"You'll think this silly, but for the last three nights I've had a queer sort of feeling that Mr. Thomson was somewhere in the audience. I can't explain it. I looked everywhere for him. I even tried looking at the people one by one, all down the rows. I never saw any one in the least like him. All the same, I expected to hear his voice at any moment."

"Granted the old boy's Satanic connections," Leonard observed, "he may appear to us in any form. Brimstone and horns are clean out of date. He'll probably send his disembodied voice with instructions."

I strolled to the wings and had a look at the house. Although it still wanted a quarter of an hour before the performance was due to commence, the hall was almost packed with people. The audience, as was natural considering the locality, was a pretty tough lot. It[Pg 17] seemed to consist chiefly of stewards and sailors from the great liners which lay in the river near by, with a sprinkling of operatives and some of the smaller shopkeepers. The study of faces has always interested me, and there were two which I picked out from the crowd during that brief survey and remembered. One was the face of a youngish man, dressed in the clothes of a labourer and seated in a dark corner of the room. He was very pale, almost consumptive-looking, with a black beard which looked as though it had been recently grown, and coal black hair. His features were utterly unlike the features of his presumed class, and there was a certain furtiveness about his expression which puzzled me. A quietly dressed girl sat by his side, whose face was even more in the shadow than his, but it struck me that she had been crying, and that for some reason or other there was a disagreement between her and the young man. The other person whom I noticed was a stout, middle-aged man, with curly black hair, a rather yellow complexion, of distinctly Semitic appearance. His hands were folded[Pg 18] upon his waistcoat, he was smoking with much obvious enjoyment a large cigar, and his eyes were half-closed, as though he were enjoying a brief rest. I put him down as a small shopkeeper, for choice a seller of ready-made garments, who had had a long day's work and was giving himself a treat on the strength of it.

At half-past seven the hall was crammed and the curtain rang up. We went through the first part of our programme with a reasonable amount of success, Leonard in particular getting two encores for one of his humorous songs. At the beginning of the second part, I came out upon the stage and made the little speech which our mysterious patron's wishes rendered necessary.

"Ladies and gentlemen," I said, "I have much pleasure in announcing, according to our posters outside, that if there are any amateurs here willing to try their luck upon the stage, either with a song or a dance, we shall be very happy to provide them with music and any slight change of costume. A prize of one pound will be given to the performer whose song meets with the greatest approval, and[Pg 19] a second prize of five shillings for the next most successful item."

I gagged on for a few more minutes, trying to encourage those whom I thought likely aspirants, amidst the laughter and cheers of the audience. Presently a showily dressed young woman threw aside a cheap fur cloak, displaying a low-cut blue satin gown, jumped nimbly on to the stage, ignoring my outstretched hand, and held out a roll of music to Rose, who came smilingly from the background.

"I'll try 'The Old Folks down Wapping Way', dear," she announced, "and don't you hurry me when the sloppy stuff comes. I like to give 'em time for a snivel or two. Sit you down at the piano. I'm that nervous, I can't stand fussing about here."

They bent over the music together and I turned back to the audience. There were only two others who showed any disposition to follow the example of the lady in blue satin. One was the young man whom I had previously noticed, and who had now risen to his feet. It was obvious that the girl by his side was[Pg 20] doing all she could to dissuade him from his purpose. I could almost hear the sob in her throat as she tried to drag him back to his place. I myself felt curiously indisposed to interfere, but Leonard, who was standing by my side, and who saw them for the first time, imagining that a word of encouragement was all that was necessary, concluded the business.

"Come along, sir," he called out. "You look as though you had a good tenor voice, and nothing fetches 'em like it. You let him come, my dear, and he'll buy you a new hat with the money."

The young man shook himself free and stepped on to the platform, obviously ill at ease at the cheer which his enterprise evoked. He was followed, to my surprise, by the middle-aged man whom I had previously noticed.

"Here, Mister," was his greeting, as he stepped on to the platform, "I'll have a go at 'em. Sheeny patter and a clog dance, eh?"

"You must find me some sort of a change," the young man insisted hurriedly.

"And I'll tidy up a bit myself," his rival observed. "We'll let the gal have first go."

[Pg 21]I conducted them behind and showed the young man into the men's dressing room.

"You'll find an old dress suit of mine there," I pointed out. "Change as quickly as you can. I don't fancy the young lady will hold them for long."

He nodded and drew me a little on one side. His manner was distinctly uneasy, and his clothes were shabbier even than they had seemed at a distance, but his voice was the voice of a person of education, pleasant, notwithstanding a queer, rather musical accent which at the moment was unfamiliar to me.

"Shall I be able to lock my things up?" he asked, in an undertone. "No offence," he went on hastily, "only I happen to be carrying something rather valuable about with me."

I handed him the key of the dressing room, for which he thanked me.

"How long will that screeching woman be?" he asked impatiently.

"You can go on directly she's finished murdering this one," I promised him. "I don't think they'll stand any more."

He nodded, and I turned back towards[Pg 22] where the other aspirant was standing in the shadow of the wings.

"Now what can I do for you, sir?" I asked. "I don't think you need to change, do you?"

There was no immediate reply. Suddenly I felt a little shiver, and I had hard work to keep back the exclamation from my lips. I knew now that Rose had been right. It was a very wonderful disguise, but our master had at last appeared. He drew a little nearer to me. Even then, although I knew that it was Richard Thomson, I could see nothing but the Jew shopkeeper.

"I shall pretend to make some slight change behind that screen," he said in a low tone. "Come back here when you've taken him on the stage. I may want you."

He disappeared behind a screen a few feet away, and I stood there like a dazed man. From the stage I could still hear the lusty contralto of the young lady candidate. I heard her finish her song amidst moderate applause, chiefly contributed by a little group of her supporters. There was a brief pause. The young lady obliged with an encore. Then the[Pg 23] door of the men's dressing room opened, was closed and locked. The young man, looking a little haggard but remarkably handsome, came towards me, clenching the key in his hand.

"I was a fool to take this on," he confided nervously. "You are sure my things will be all right in there?"

I pointed to the key in his hand.

"You have every assurance of it," I told him.

He fidgeted about, listening with obvious suffering to the girl's raucous voice.

"Ever been in the profession?" I enquired.

"Never," was the hasty reply.

"What's your line to-night?"

"Tenor. Your pianist will be able to do what I want. I've heard her."

"If you win the prize, do you want a job?" I asked, more for the sake of making conversation than from any real curiosity.

He shook his head.

"I've other work on."

"Down at the docks?"

"That's of no consequence, is it?" was the[Pg 24] somewhat curt reply.—"There, she's finished, thank heavens! Let me get this over."

I escorted him to the wings. The young lady, amidst a little volley of good-natured chaff, jumped off the stage and returned to her friends. Her successor crossed quickly towards Rose, who was still seated at the piano. I slipped back behind the scenes. Mr. Richard Thomson was examining the lock of the men's dressing room.

"He's got the key," I told him.

There was no reply. Then I saw that our patron held something in his hand made of steel, which glittered in the light of an electric torch which he had just turned towards the keyhole. A moment later the door was opened and he disappeared. Out on the stage, Rose was playing the first chords of a well-known Irish ballad. Then the young man began to sing, and, notwithstanding my state of excitement, I found myself listening with something like awe. The silence in the hall was of itself an extraordinary tribute to the singer. Shuffling of feet, whispering and coughing had ceased. I felt myself holding my own breath,[Pg 25] listening to those long, sweet notes with their curious, underlying surge of passion. Then I heard Mr. Thomson's voice in my ear, curt and brisk.

"You've a telephone somewhere. Where is it?"

"In the passage," I pointed out.

He disappeared and returned just as a roar of applause greeted the conclusion of the song. The young man hurried in from the stage. The Jew shopkeeper was seated in the same chair, with his hands in his pockets and a disconsolate expression upon his face. Outside, the audience was literally yelling for an encore.

"You'll have to sing again," I told him.

"I don't want to," he declared passionately. "I was a fool to come."

"Nonsense!" I protested, for the uproar outside was becoming unbearable. "Listen! They'll have the place down if you don't."

"I sha'n't go on," his rival competitor grumbled sombrely, thrusting a cigar into his mouth and feeling in his pockets for a match. "You've queered my pitch all right. They're[Pg 26] all Irish down in this quarter. You've fairly got 'em by the throat."

The young man stood still for a moment, listening to the strange cries which came from the excited audience. Suddenly inspiration seemed to come to him. His eyes flashed. He turned away and strode out on to the stage almost with the air of a man possessed by some holy purpose. I followed him to the wings, and from there I had a wonderful view of all that happened during the next few minutes. The young man stood in the middle of the stage, waved his hand towards Rose, to intimate that he needed no music, waited for a few more moments with half-closed eyes and a strange smile upon his face, and commenced to sing. I realised then what inspiration meant. He sang against his will, carried away by an all-conquering emotion, sang in Gaelic, a strange, rhythmic chant, full of deep, sweet notes, but having in it something almost Oriental in its lack of compass and superficial monotony. Again the silence was amazing, only this time, as the song went on, several of the women began to sob, and a dozen or[Pg 27] more men in the audience stood up. Afterwards I knew what that song meant. It was the Hymn of Revolution, and every line was a curse.

From my place in the wings I was able to follow better, perhaps, than any one else in the room, the events of the next sixty seconds. I saw two policemen push their way along the stone passage, past the box office and into the back of the hall, led by a man in plain clothes, a stalwart, determined-looking man with a look of the hunter in his face. Almost at the same moment the singer saw them. His song appeared somehow to become suspended in the air, ceased so abruptly that there seemed something inhuman in the breaking off of so wonderful a strain. He stood gazing at the slowly approaching figures like a man stricken sick and paralysed with fear. Then, without a word, he left the stage, pushed past me, sprang for the dressing room, and, turning the key in the lock, disappeared inside. I followed him for a few yards and then hesitated. Behind, I could hear the heavy, slowly moving footsteps of the police, making their way with[Pg 28] difficulty through the crowd, a slight altercation, the stern voice of the detective in charge. Then, facing me, the young man emerged from the dressing room, ghastly pale, shaking the coat in which he had arrived, distraught, furious, like a man who looks upon madness. Mr. Richard Thomson leaned back in his chair, his mouth open, his whole attitude indicative of mingled curiosity and surprise.

"What you break off for like that, young man?" he demanded. "Have you forgotten the words? You've won the quid all right, anyway."

"I've been robbed!" the singer called out. "Something has been stolen from the pocket of this coat!"

"You locked it up yourself," I reminded him, with a sudden sinking of the heart.

"I don't care!" was the wild reply. "It was there and it is gone!"

He flung the coat to the ground with a gesture of despair. The advancing footsteps and voices were louder now. The man in the plain clothes pushed his way through the[Pg 29] wings, beckoned the police to follow and pointed to the young man.

"The game's up, Mountjoy," he said curtly. "We don't want any shooting here," he added, as he saw the flash of a revolver in the other's hand. "I've half a dozen men outside besides these two."

The trapped man seemed in some measure to recover himself. He half faced me, and the revolver in his hand was a wicked looking instrument.

"Some one has been at my clothes," he muttered, his great black eyes glaring at me. "If I thought that it was you——"

I was incapable of reply, but I imagine that my obviously dazed condition satisfied him. He turned from me towards where Mr. Richard Thomson was seated, watching the proceedings with stupefied interest, breathing heavily with excitement, his mouth still a little open.

"Or you," the young man added menacingly.

Thomson held out his hands in front of his face.

[Pg 30]"You put that up, Mister," he enjoined earnestly. "If you're in a bit of trouble with the cops, you go through with it. Don't you get brandishing those things about. I've known 'em go off sometimes."

The singer's suspicions, if ever he had any, died away. He tossed the revolver to the officer, who had halted a few yards away.

"Better take me out the back away," he advised. "There'll be trouble if the crowd in front gets to know who I am."

The officer clinked a pair of handcuffs on his captive's wrists with a sigh of satisfaction. They moved off down the passage. All the time there had been a queer sort of rumble of voices in front, which might well have been a presage of the gathering storm. I moved back to the wings just in time to see the torch thrown. The girl who had been seated with the young man, suddenly leaped upon a bench. She snatched off her hat and veil as though afraid that they might impede her voice. A coil of black hair hung down her back, her face was as white as marble, but the strength of her voice was wonderful. It rang through the hall[Pg 31] so that there could not have been a person there who did not hear it.

"You cowards!" she shouted. "You have let him be taken before your eyes! That was Mountjoy who sang to you—our liberator! Rescue him! Is there any one here from Donegal?"

Never in my life have I looked upon such a scene. The men came streaming like animals across the benches and chairs, which they dashed on one side and destroyed as though they had been paper. I was just in time to seize Rose and draw her back to the farthest corner when the sea of human forms broke across the stage. Nobody took any notice of us. They went for the back way into the street, shouting strange cries, brandishing sticks and clenched fists, fighting even one another in their eagerness to be first. Until they were gone, the tumult was too great for speech. Rose clung to my arm.

"What does it mean, Maurice?" she asked breathlessly. "Who is he?"

"I have no idea," I answered, "but I can[Pg 32] tell you one thing. To-night has been our début."

"Talk plain English," Leonard begged. "Remember we had to be on the stage all the time."

"It means," I explained, "that we've begun our little job as spokes in the wheel which our friend Mr. Richard Thomson is turning. You remember the other competitor, a man who never sang at all, who looked like a Jew fishmonger in his best clothes?"

"What about him?" Rose demanded.

"He was Mr. Richard Thomson," I told her. "You and I, Leonard, are simply mugs at making up. It was the most wonderful disguise I ever saw in my life."

"That accounts for it," she declared, with a little shiver. "He has been here before, watching. I told you that I felt him around, without ever recognising him."

"Where is he now?" Leonard asked abruptly.

We searched the place. There was no sign of our patron. Just as mysteriously as he had come, he had disappeared. The young lady[Pg 33] in blue satin came up and claimed her sovereign. We went down into the auditorium and inspected the damage. Finally, as we were on the point of leaving, a smartly dressed page came in through the back door and handed me a note. It was dated from the Adelphi Hotel and consisted only of a few lines:

Mr. Richard Thomson presents his compliments and will be glad to see Miss Mindel, Mr. Lister and Mr. Cotton to supper to-night at eleven-thirty.

History repeated itself. When we presented ourselves at the Adelphi Hotel and enquired for Mr. Richard Thomson, doors seemed to fly open before us, a reception clerk himself hurried out with smiles and bows, and conducted us to the lift. We were ushered into a luxurious sitting room on the first floor and welcomed by our host, whose carefully donned dinner clothes and generally well-cared-for appearance revealed gifts which filled me with amazement.

"This is a very pleasant meeting," Mr. Thomson declared, as he placed us at the table and gave orders that the wine should be[Pg 34] opened. "We met last on the east coast, I remember. I trust that you are finding business better?"

"Business is wonderfully good," I acknowledged.

"We turned away money last week," Leonard announced.

There was something a little unreal about the feast which was presently served, excellent though it was, and I am quite sure that we three guests breathed a sigh of relief when at last the table was cleared and the waiter dismissed. Our host lit a cigar and leaned back in his high chair. With the passing of that smile of hospitality from his lips, his face seemed to have grown hard and unpropitious.

"I trust," he said slowly, "that you are all satisfied with our arrangement so far?"

"We are more than satisfied," I assured him, trying to infuse as much gratitude as I could into my tone. "I am thankful to say that we are able to put by a little every week, too, towards the capital which you advanced. The new costumes, songs and posters are bringing something of their own back."

[Pg 35]Mr. Thomson waved his hand.

"That is a matter of no concern," he pronounced. "Have you anything further to say?"

I looked at Leonard and at Rose. We all three looked at our host.

"I should like to know," I asked bluntly, "how much of my soul was scotched by to-night's little adventure?"

Mr. Thomson stretched out his hand for the evening paper which the waiter has just placed by his side.

"I do not wish to encourage curiosity," he remarked coldly. "Our bargain renders any explanation on my part unnecessary. You had better read aloud that item in the stop press news, however. It may allay your qualms, if you are foolish enough to have any."

The sheet was wet from the press. I held it under the light and read:—

ARREST OF MOUNTJOY, THE CASTLE DERMOY MURDERER!

Denis Mountjoy was arrested to-night at a music hall in Watergate Street. A determined attempt was made at a rescue, and a[Pg 36] free fight took place outside the Watergate Street police station, all the windows of which were broken. With the arrest of Mountjoy, who will be charged with no less than five murders, it is hoped that the whole conspiracy of which he was the head will be broken up. It is known that he has in his possession the famous minute book of the revolutionary secret society which bore his name, and numerous other arrests may be expected at any moment. The chief constable has received a telephone message of congratulation from Scotland Yard.

I laid down the paper. For the life of me I could not keep back the question which rose to my lips.

"There was five hundred pounds reward for the arrest of Mountjoy. Are you claiming it?"

"Blood money," Mr. Thomson confessed, with a queer smile, "is not in my line."

"It was you who put the police on to Mountjoy?" I persisted.

He made no direct reply. He was stonily thoughtful for a moment.

"I knew," he continued presently, "I believe even the police knew, that Mountjoy was[Pg 37] lying hidden somewhere within a quarter of a mile of Watergate Street. How to draw him out of his hiding place was the problem. I remembered his two failings,—vanity, and love of hearing that beautiful voice of his. I pandered to them."

"You laid a trap on behalf of the police, then?"

Mr. Thomson knocked the ash from his cigar.

"That might be considered the truth," he admitted.

"And the minute book?"

"Concerning the minute book," he replied, "I have nothing to say."

Rose drew her chair a little nearer towards him. The rose-shaded electric light shone upon her fair hair, her wonderful eyes, her piquant face with its alluring smile. She leaned forward towards our host, and it seemed to me that the soft entreaty in her tone and the pleading of her eyes were irresistible.

"Mr. Thomson," she said, "I am a woman, and I am desperately, insatiably curious. I must know—please tell me—what are we[Pg 38]—you and we three? Your confederates, I suppose we are? Are we on the side of the police or the criminal, the informer, or do we come somewhere between? I must adapt my conscience to our position."

Mr. Thomson was unshaken. He looked at Rose just as though she had been an ordinary human being.

"That," he said, "may be put in the category of questions which you will be at liberty to ask me when our agreement comes to an end. Shall we call it Conundrum Number 1? By the bye, if it is any convenience to you to know your movements in advance, I may tell you that you will open at Bath next week."

The thing which surprised me most about the unseen hand which seemed to be always with us was the way in which it disposed of the ladies' orchestra in the Crown Hotel at Bath. I met the pianiste in the street while I was waiting for instructions, and it was she who made the matter plain to me.

"I suppose you have heard that we have finished at the Crown for the present?" she asked.

I had been genuinely surprised to hear that this was the case, and I told her so. After a moment's hesitation, she unburdened herself of a secret.

"Please don't tell a soul," she begged, "except Miss Mindel and Mr. Cotton, if you want[Pg 40] to. The fact of it is, the most extraordinary thing is taking us away. We have been offered, without a word of explanation, a hundred pounds between the four of us to go away for a month."

"Nonsense!" I exclaimed.

"It is perfectly true," she repeated. "A lawyer in the city brought the notes and an agreement, absolutely refusing a single word of explanation. We didn't worry very much, I can tell you. Twenty-five pounds isn't picked up every day, but I don't mind confessing that when I think about it, I get so curious it makes me positively ill. Miss Brown's theory is that it's one of these old cranks in the hotel, with more money than he knows what to do with, who hates music. On the other hand, the management has received no complaints, and there's nothing to prevent another orchestra taking our place next Monday."

I made my way to the lounge of the hotel where Leonard, Rose and I had arranged to meet for afternoon tea. We were having rather a quiet time, having already performed[Pg 41] for a week at the local music hall with some success, and were now obeying instructions by staying on at our rooms and waiting for orders. There were too many people about for me to impart the news to them at that moment, so we fell to criticising the passers-by, an uninteresting crowd with one or two exceptions. There was a large but not unwieldly man, carefully dressed, with a walrus-like beard and moustache, heavy eyebrows and a surly manner, who was generally muttering to himself. His name was Grant, he was reputed to be over eighty, to be without a friend in the hotel, and to growl at every one who spoke to him. Every afternoon at half-past four he came in from a turn in his bath chair, and stumped past the orchestra with his finger to his ear. Then there was a frail, olive-skinned man, tall and gaunt, with wonderful black eyes, escorted every day to the baths and brought back again by a manservant who looked like a Cossack. His name was Kinlosti, and he was reported to have been an official at the Court of the late Tsar, and even to have accompanied him to Siberia. The[Pg 42] third person, who interested us because we all detested her, was an enormously fat old lady, with false teeth, false grey ringlets, a profusion of jewellery, and a voice which Leonard said reminded him of the hissing of a rattlesnake. Her name was Mrs. Cotesham, she was stone deaf, and between her and Mr. Grant there was a deadly feud. They never spoke, but if glances could kill both would have been in their coffins many times a day. They both wanted the same chair in front of the fire, they both struggled for the Times after lunch, they ordered their coffee at the same moment, and whichever was served last bullied the waiter. They provided plenty of amusement for lookers-on and to the guests generally, but I think that the management, and certainly the waiters, were prepared to welcome the day they left the hotel. When the people had thinned out a little, and there was no one in our immediate vicinity, I told my two companions of the strange thing which had happened to the ladies' orchestra.

"It must have been Mr. Grant," Rose declared.

[Pg 43]"I put my money on the old lady," Leonard decided.

But I knew that it was neither, for even while they were speaking the hall porter, who knew me by sight, had brought me a typewritten note, which he said had been left by hand. I tore it open and read. There was no address nor any signature. Neither was needed:

Apply at office of Crown Hotel for permission to give entertainments, commencing soon as possible.

I passed the note on to the others.

"We needn't speculate any more about that hundred pounds," I remarked.

There were no difficulties at the office. The next afternoon, at half-past four, we took the place of the departed orchestra. The change was pleasantly received by the majority of the guests. Mr. Grant, however, while Rose was still in the middle of her introductory pianoforte solo, stumped out of the room with his hand to his ear, and Mrs. Cotesham deliberately turned her chair round and sat with her back to us. On the other hand, Mr. Kinlosti,[Pg 44] passing through the hall leaning on his servant's arm, on his way from his bath, caught sight of Rose at the piano and lingered. He whispered in his servant's ear, found a chair and a table, and seated himself in a dark corner. Presently the latter brought him from upstairs a pot of specially prepared tea and some cigarettes. He remained there throughout the whole of our performance, his eyes fixed upon Rose,—strange, uncanny eyes they were. The corner he had chosen was close to where we were playing, and the flavour of his Russian cigarettes and highly scented tea attracted Rose's attention, so that more than once she turned and looked at him. For the first time I saw a very faint smile part his thin lips.

"A conquest," I whispered to Rose, as I bent over her chair to move some music.

She made a little grimace.

"All the same," she said, "I'd love some of his cigarettes."

That evening, just before the time fixed for the commencement of our performance, another typewritten note was put into my hand,[Pg 45] again unsigned and undated. This is what I read:

It is my wish that if a person of the name of Kinlosti should seek acquaintance with any of you, he should be encouraged. Particularly impress this upon Miss Mindel.

I took Leonard on one side.

"Leonard," I said, "our souls are trash, and what happens to us doesn't matter a damn. But read this!"

Leonard read it and swore.

"Can you get into touch with Thomson?" he asked.

"Only through the banker's address in London," I replied. "Where these typewritten notes drop from not a soul seems to know."

Rose came up and read the message over our shoulders. Her view of the matter was different.

"What fun!" she exclaimed. "Perhaps I shall get some cigarettes."

"You don't suppose we are going to allow this?" I asked hotly.

"Not for one moment!" Leonard echoed.

She laughed softly.

[Pg 46]"You idiots!" she exclaimed. "Do you think I can't take care of myself? Or don't you trust me?"

"You know that it isn't that," I rejoined, "but neither Leonard nor I are willing to see you made a cat's-paw of."

"Russians don't know how to treat women," Leonard put in.

She became serious, but she remained very determined.

"Anyhow," she said, "I know how to treat Russians, so please leave me alone. Remember that I, too, am under contract to Mr. Mephistopheles Thomson, and although I love you both, you're not my guardians."

That was the end of the matter, so far as we were concerned. When we commenced our performance, Kinlosti was established in the dark corner, his coffee and a whole box of his inevitable cigarettes before him. His dinner clothes were severe and unadorned, but three wonderful black pearls shone dully in his shirt front. The lounge was more than ordinarily full, for our previous week's performance in Bath had brought us some popularity. Mr.[Pg 47] Grant, however, again stumped out of the place, muttering rudely to himself as he passed us, and the old lady turned her back and tried by means of an ear trumpet to enter into conversation with any one who was unfortunate enough to be near. These two were the only exceptions, however. The rest of the audience was unmistakably friendly.

Leonard and I were to learn something that night of the subtlety of a woman's ways. No one who had been watching could have said that she deliberately encouraged this mysterious admirer. On the other hand, she returned his bold glances with something which I had never seen in her eyes before, something indefinably provocative, certainly with no shadow of rebuke. Her acceptance of his overt admiration was in itself a more significant thing than the frank smiles of a more easily accessible siren. By the time I started off round with the plate for the usual silver collection, I was in such a temper that I found it difficult to pause even for a moment as I reached his corner. He laid a ten-shilling note upon the little pile of silver, and also placed an envelope[Pg 48] there. I saw with gathering anger that it contained something heavy, and that it was addressed to Miss Mindel.

"I have ventured," he said, in a very low and extraordinarily pleasant voice, "to offer for the young lady's acceptance, in return for her delightful music, a little souvenir from the country in which I have lived all my life."

"Miss Mindel does not accept presents from strangers, sir," I said, returning him the envelope.

He shrugged his shoulders slightly, stretched out his hand for his jade-headed stick, and, leaning heavily upon it, crossed the floor towards the spot where Rose was seated at the piano, playing soft music. Notwithstanding his lameness, his bow, as he approached her, would have done credit to a courtier.

"May I be allowed," he said, "to congratulate you upon your very delightful singing and playing? It has given so much pleasure to an invalid whose life just now is very monotonous, that I am venturing to ask your accept[Pg 49]ance of this little trifle, a souvenir from a great country, now, alas! stricken to the earth."

Rose opened the envelope, and held in her hand a quaint ring in which was a black stone. I leaned over her. It was engraved with the royal arms of the Romanoffs, and at the top was a small 'N.'

"I thank you very much indeed," she replied, smiling up at him, "but I could not possibly accept so valuable a gift."

"Will you believe me," he persisted, "that the ring has little, if any, intrinsic value. It is an offering which an artist in a small way might at any time be permitted to present to such gifts as yours."

He passed on towards the lift with a little bow which included all of us, and somehow or other the ring was on Rose's finger, and whether we liked it or not she had accepted it. After that we saw a great deal of Mr. Kinlosti. He was never obtrusive and yet he was persistent. On the day following the presentation of the ring, we somehow found ourselves lunching with him. On the day after that we used his car, and on the following day, al[Pg 50]though both Leonard and I protested, he took Rose out for a drive alone. She came home sooner than we had expected and was a little silent for the rest of that day. At supper time she took us into her confidence.

"Mr. Kinlosti," she said, "told me a very strange story this afternoon. Parts of it were so horrible that it made me shiver. It seems he was one of the few members of the household who accompanied Nicholas to Siberia. He got away just before the final tragedy."

"What was his excuse for leaving his master?" I asked, a little coldly.

We were all three in the parlour of our lodging house, and quite alone. Nevertheless, Rose lowered her voice as she answered me.

"The Tsar entrusted him with the knowledge of where a portion of the Crown jewels were secreted. He was to find them, raise money, and try and bribe the Siberian Guards. He found the jewels all right, but not until Nicholas and the whole of his family had been assassinated."

"What did he do with the jewels?" Leonard asked.[Pg 51]

"He has not told me so in so many words, but I believe that he has them here," she replied. "He told me they were still in his possession and he held them in trust for the Romanoffs. The terrible part of the business for him is that he has been tracked all over Europe by Bolshevist agents, who claim that the jewels belong to the Russian State."

"Why did he tell you all this?" I enquired, with growing suspicion.

Rose shook her head.

"Perhaps to account for the fact that he seemed so nervous all the time," she suggested. "He started whenever another motor car passed us, and as long as we were in Bath itself he watched the faces on the pavements, as though all the time he were looking for some one. He told me that when first he arrived here he suspected even the masseurs at the baths."

"I still don't see why he was so confidential with you," Leonard grumbled.

"He likes me," she acknowledged, with a demure smile. "In fact, if he tells the truth, he likes me very much. Don't look so black,[Pg 52] please," she went on, with a glance at our faces. "Remember I am only obeying orders."

That phrase cost us a good deal of uneasiness during the next few days. Whenever we performed, Kinlosti sat in his corner, watching and listening. In the intervals, he came and made timid and courteous conversation. Without going so far as to say that he pursued Rose, he certainly took up a great deal of her time. On the fourth afternoon I received another typewritten note, handed to me again from the porter's office without any intimation as to its source. There was only a line or two:

Miss Mindel should show some curiosity as to the Crown Jewels. Mr. Kinlosti would probably like to show them to her.

Within half an hour Rose made her request. Both Leonard and I were within a few yards, and we saw the sudden terror in his face, heard his almost hysterical refusal.

"No one has ever seen them," he told Rose, "since they first came into my possession. I do not dare even to look at them myself.[Pg 53] Directly my rheumatism permits me to move without pain, I shall acquit myself of the trust. It weighs upon me night and day."

With that the matter would have been ended, so far as Leonard and myself were concerned. Rose, however, took it differently. For the rest of that afternoon we were able to appreciate fully the guile of our little companion. She received Kinlosti's refusal in silence. Presently she developed a headache and refused to talk. She sat with her shoulder turned away from him while she played and never once glanced in his direction while she sang. At the close of our performance, he came up and whispered to her earnestly. She shook her head at first and then turned to me.

"Mr. Kinlosti is going to show me something in his sitting room. Please come with us."

For the first time I saw the Russian in this sallow-faced invalid. His lips curved into a snarl and for a moment he glared at me. The fit of anger was gone in a moment, before Rose had even observed it. With a little courteous gesture towards her, he turned and[Pg 54] limped towards the lift. We followed, and he led us into his suite on the first floor.

"Do not be frightened of John," he enjoined, as he opened the door. "John is the guardian of my treasure, and he is obsessed with the idea that there are thieves in this hotel."

From the appearance of John, it seemed as though any adventurous thieves would have had a pretty poor time. He was seated with folded arms upon a hard, straight-backed chair. On a table by his side, only partially concealed by a large handkerchief, was an obvious revolver. There was also a glass of strong brandy and water. He rose to his feet at our entrance, but his bearing was grim and unfriendly. His master talked to him for a few moments in his own language, apparently trying to assure him of the harmlessness of our presence. John, however, remained sulky. Kinlosti crossed to the farthest corner of the room, took a key from his pocket, a key which seemed to be attached to a band of snakelike silver which encircled his leg, and unfastened an ordinary black tin dispatch box, which[Pg 55] stood on the floor. From this he drew out a coffer of some almost black-coloured wood, with brass clamps. He held it up towards Rose.

"Even for you, my dear young friend," he said, "I may not raise the lid, but I show you this much of your desire. This is one of the coffers which for eleven hundred years has held the ceremonial jewels of the Russian Royal Family. There were at one time five of them. This is the one that remains."

"Mayn't I have just one little peep inside?" Rose pleaded.

We heard John's heavy breathing, and Kinlosti scarcely waited even to answer her. He thrust the coffer back into the box and locked it.

"It is impossible," he pronounced. "I do not bear this trust alone. In the spirit I fear that I break it already. You will rest here for a little while, mademoiselle?"

If this was meant as a hint to me, it was of no avail. I stood by Rose's side and she shook her head.

[Pg 56]"You will not let me make you some of our own Russian tea?" he begged.

"Bring me some downstairs," she suggested. "I should love the tea, if it isn't too much trouble, and I will come over and sit in your corner."

In the corridor, on our way down, we met the malevolent Mrs. Cotesham, who paused, leaning on her stick, and watched Rose and her companion with the hungry glare of the professional scandalmonger. Kinlosti hurried past her with a little shiver, and Rose laughed gaily as she descended the stairs.

"I believe that you have a penchant for Mrs. Cotesham," she declared.

"She is the most horrible old lady I have ever seen anywhere," he said fervently. "They tell me that she is over ninety, and that she has but one joy in life—to make where she can mischief and trouble and unhappiness. She comes here every year, and every servant hates her. Even the managers would keep her away if they could, but she has bought shares in the hotel and has interest with the directors."

[Pg 57]"The old man Mr. Grant is nearly as bad," Rose remarked.

"Him I know nothing of," Kinlosti replied, "save that he is one of those who have surely lived too long."

Leonard and I left Rose to her tête-à-tête and took a seat in the lounge. A few yards from us, the little daily comedy which never failed to amuse the onlookers was in progress. Mr. Grant was seated in the easy chair affected by Mrs. Cotesham. She came stumping along from the lift and stopped about a foot from the chair.

"This man has taken my chair!" she exclaimed in a loud voice, for the benefit of every one. "I left a book in it."

Mr. Grant continued to read through his heavy spectacles, unmoved. She struck the side of his chair with her stick.

"I want my chair," she repeated.

Mr. Grant half turned round.

"What does the woman want?" he snarled. "This isn't her chair. It's an hotel chair. I found it empty and I sat down. I am going to stay."

[Pg 58]"Where's my book?" Mrs. Cotesham demanded, handing him the end of her ear trumpet.

"I threw it on the lounge," he shouted. "There it is. Now don't bother me any more."

"He calls himself a gentleman!" the old lady declared, shaking with fury.

"Never called myself anything of the sort in my life," he snapped.

I rose, and wheeled the easy chair in which I was sitting to the side of Mr. Grant's.

"Will you sit here, madam?" I ventured. "It is as near your favourite position as possible."

She pushed her speaking trumpet almost into my face.

"Say that again, young man," she directed.

I repeated it at the top of my voice. She nodded and subsided into the chair.

"I don't like having to sit near such people," she said, "but I prefer this side of the fireplace."

Her neighbour looked out of the corner of his eye.

"I wish the pestilential old woman would[Pg 59] stay up in her room," he growled. "I hate her next me."

She handed him her speaking trumpet.

"Say that again, will you?" she invited. "I don't like people talking about me when I can't hear what they say."

Mr. Grant shut his book with a snap, rose to his feet and hobbled across to a distant part of the lounge.

"That old woman ought to be locked up," he declared at the top of his voice. "She's a damned nuisance to everybody!"

He found another seat and recommenced his book. Mrs. Cotesham, with a purr of content, settled herself down in the chair which he had vacated, stretched out her feet upon the footstool and looked around triumphantly.

"I've been to a good many hotels in my life," she confided to every one within hearing, "but I never met a man who called himself a gentleman, with such disgusting manners!"

Leonard and I strolled away presently to find Rose. It was time for us to go back to our rooms and change for the evening performance. We found her with Kinlosti in his[Pg 60] corner, and the air above them overhung with a thin cloud of blue tobacco smoke. Kinlosti was smoking furiously and talking hard. Rose welcomed our approach, I thought, with something almost like eagerness.

"It is time to go, I am sure," she declared, springing to her feet.

Her companion broke off in the middle of a sentence and frowned.

"We speak together to-night, then?"

She shook her head at him, smiling all the time though, and with that little tantalising look in her eyes which Leonard and I both knew so well.

"I am not sure," she replied. "The management will complain if I talk so much with one of the guests, but I will play 'Valse Triste' for you. Au revoir!"

We had almost left the hotel—we were on the outside steps, indeed—when the hall porter caught me up. I saw at once what he was carrying. It was one of the now familiar typewritten letters. This time I asked him a point-blank question.

"Look here," I said, with my hand in my[Pg 61] trousers pocket, "this is the third note I have received from my friend in this fashion. I want to know how they come into your possession. Who leaves them at the bureau?"

The man saw the ten-shilling note in my hand but he only shook his head. I believe that he was perfectly honest.

"I would tell you in a minute if I knew, sir," he declared, "but to tell you the truth I have never seen one delivered. All three I have picked up from the desk in my office, evidently left there when my back was turned for a moment."

"You haven't any idea who leaves them there, then?" I persisted.

"Not the slightest, sir," the man assured me.

"Keep a good lookout," I begged him, "and let me know if you do find out. There may be another one—I can't tell—but I'll double this ten shillings if you succeed."

The man thanked me and withdrew. We three crossed to the less frequented side of the road. I walked in the middle, with Rose and[Pg 62] Leonard on either arm. We read the note together:

If the box Miss Mindel saw in Kinlosti's room was of purple leather, with gold clasps and corners, let the first item in your repertoire to-night be the Missouri Waltz. If it was a box of any other description, play the selection from "Chu-Chin-Chow."

"Well, I'm damned!" Leonard exclaimed.

"Be careful," I advised. "Thomson's probably underneath these paving stones."

Rose shivered a little.

"Do you think he wants to steal the jewels, Maurice?" she asked me.

"Oh, no!" I answered. "He probably wants to borrow them to wear at the Lord Mayor's show!"

She made a grimace.

"That's all very well, Mr. Lister," she said, with a great attempt at hauteur, "but will you kindly remember that you two are not in at this show? It is I who seem to be chosen as principal accomplice. I am not exactly infatuated with Mr. Kinlosti, but I don't want him to lose his jewels."

[Pg 63]"I bet you a four-pound box of chocolates he does lose them," Leonard observed.

Rose sighed.

"Anyhow," she murmured, "we shall have to play 'Chu-Chin-Chow' to-night."

Leonard and Rose played a selection from "Chu-Chin-Chow" that evening as

well as they could with an extemporised rendering. Rose played the

piano, Leonard the violin, and I pretended to be turning over the pages

of the music, although all the time I was engaged in a furtive search of

the crowded lounge for some sign of our patron or a possible emissary.

There were the usual little groups about, and a more harmless or obvious

set of people I don't think I ever came across. Mrs. Cotesham was seated

with her back to us, with a shawl arranged around her head so as to

still further deaden sound, and ostentatiously reading a novel. Mr.

Grant had stumped past us on his way to the billiard room, muttering to

himself, before the first few bars of our little effort had been played.

The others were nearly all known to us by name or reputation. There

seemed something uncanny in the[Pg 64] thought that somewhere or other were

ears waiting for the message our selection conveyed. We were half-way

through the "Cobbler's Song" when, without the slightest warning, Rose,

who was facing the staircase, broke off abruptly in her playing. I

caught sight of her face, suddenly pale, upturned towards the head of

the staircase, followed the direction of her gaze, and was myself

stricken dumb and nerveless. At the top of the staircase John was

standing, holding out a terrified, struggling figure almost at arm's

length. The fingers of his right hand seemed to be clasped around the

neck of his unfortunate victim, while with his left hand he held him by

the ankle. This was all in full view of the lounge. There were shrieks

from the women, and some of the men, amongst them myself, hurried

towards the staircase. We were too late, however, to be of any practical

use. John, who seemed like a man beside himself with passion, suddenly

swung the prostrate form of his captive a little farther back, and then

dashed it from him down the stairs. A little cry of horror rippled and

sobbed through the [Pg 65]tense air. The man lay on the rug at the bottom of

the stairs, a crumpled-up heap, motionless and without speech.

There were shrieks from the women, and some of the men,

amongst them myself, hurried towards the staircase. Page 64.

There were shrieks from the women, and some of the men,

amongst them myself, hurried towards the staircase. Page 64.

I was one of those who helped to carry the unfortunate victim of John's fury into the manager's office. He appeared to be a man of about medium height and build, dressed in the severest clerical clothes. I remembered having seen him arrive on the previous day. We laid him upon a sofa and left him there while one of us telephoned for a doctor. Out in the lounge, every one was grouped around the stairs, where Kinlosti was talking to John. The veins of the latter's temples were still standing out, but he was rapidly calming down. He spoke in a loud voice, so that every one might hear.

"That man is a thief in disguise," he shouted. "You will find burglar's tools in his pocket and a revolver. He came into the room where I was guarding my master's property, pretended to have mistaken the room, and tried[Pg 66] to slip in behind me. I was too quick for him. He has followed us from Russia, that man. My master will tell you."

The manager, who had been lingering in the background, came down the stairs.

"The man's story may be true," he said. "Two of the maids saw him hanging about. They heard the altercation, and there is a chloroformed handkerchief in the sitting room."

"I have a valuable box there," Kinlosti explained, "which it is my servant's duty to guard. It contains property which belongs to the dead."

"All the same," one of the bystanders observed, "one does not treat even a thief like that. The man's neck is probably broken."

Kinlosti seemed to have lost his nervousness in this minute of crisis.

"I beg," he said to the manager, "that you will await the doctor's verdict before you send for the police. If the man is not seriously injured, he got no more than his deserts. It was John's duty to guard what he was guarding with his life."

[Pg 67]"Here is the doctor," the manager announced.

Half a dozen of us followed the manager and the doctor back to the room where we had carried the injured man. When we opened the door, however, we were faced with a great surprise. There was a current of cold air, the window was wide open, the sofa was empty! To all appearance, a miracle had happened. We examined the ground below the window and found traces of where a man had stepped out. To those of us who had seen the fall, the thing grew more wonderful the more we thought of it.

"I think," the doctor pronounced, "that this is more a case for the police."

Kinlosti shook his head.

"I do not think," he said drily, "that the police of Bath are likely to be of much service in this matter."

"You have a suspicion, perhaps?" the manager asked.

Kinlosti smiled a little bitterly.

"I know the people who have been following me," he replied, "who would follow me[Pg 68] around the world until I am quit of my trust. They are Jugo-Slav Jews, boneless and bloodless as the worm that you cut in two only to find of dual life. No Bath policeman will ever lay hands upon that seemingly reverend gentleman."

"At the same time," the manager said a little stiffly, "I shall give information. It appears that he wrote for a room a week ago, from a vicarage near London, and signed himself 'The Reverend Edward Cummings.'"

"You will find that vicarage a myth," Kinlosti observed, "as much a myth as the Reverend Edward Cummings himself."

The sensation died away. We all drifted back to our places. At the manager's earnest request we recommenced our programme, but I am quite sure that no one listened, for the buzz of conversation almost drowned the sound of our instruments. The manager carried on an earnest conversation with Kinlosti in his corner, greatly, apparently, to the latter's distress. After our first essay we attempted no more music. Leonard went off to speak to some friends in the lounge. I was talking to[Pg 69] Rose and showing her a paragraph in the evening paper, when Kinlosti approached.

"It is very distressing," he said. "Because of this unfortunate happening, the manager has asked me to leave the hotel. Every place in Bath is full, and my cure is not complete."

I showed him the paragraph in the paper.

"You may not be able to go," I pointed out. "It seems that there is every possibility of a railway strike being declared to-night."

He glanced at the paragraph and returned the paper to me unmoved.

"It would not affect me," he said. "I travel everywhere by car. I think after what has happened I shall go. In London I can acquit myself of my trust. I see that the person who is empowered to take over my responsibility is back in London a few days sooner than he was expected."

I looked at the paragraph underneath the one which I had indicated, which announced that a royal personage had returned to London a few days earlier than intended, owing to the threatened strike.

"To-morrow," Kinlosti continued quietly,[Pg 70] "I shall order my car and depart. It will perhaps be better. If things get worse, they may commandeer the petrol. I will rid myself of this responsibility and either return or try Harrogate. You three will come up and have a bottle of wine with me and some sandwiches?"

Rose, to my joy, was quite firm in her refusal. She returned with him to his corner, however, and they sat there with their heads very close together whilst Leonard and I fidgetted about in the lounge. A period of quietude had followed the excitement of the last half-hour. Mr. Grant had apparently fallen asleep in his easy chair. Mrs. Cotesham watched him malevolently through her horn-rimmed spectacles.

"What a pity for a man to make such ugly noises when he's asleep!" she remarked to her neighbour. "I wish some one would wake him up. He's disturbing the whole room."

Mr. Grant opened one eye, then the other. Finally he sat up.

"Madam," he shouted, as she raised her[Pg 71] trumpet to her ear, "you forget that I am not like you—deaf!"

"I don't care whether you are or not," she replied. "I'm glad I woke you up. Bed's the place for you."

"A coffin's the place for you," Mr. Grant muttered under his breath. "How are you going to get away from here, ma'am?" he continued, raising his tone. "I hear your rooms are let from to-morrow."

"I sha'n't ask you for a place in your car," she answered. "Very likely I sha'n't go. They can't turn me out."

"I don't think they'll miss the opportunity," her interlocutor retorted, with a sardonic smile.

She laid her speaking trumpet in her lap.

"I sha'n't listen to you any more," she declared. "You're a rude old man. If it interests any one else to know what will become of me, I have relatives in Bristol who will be only too glad for me to pay them a visit."

"They'll be gladder to get rid of her," Mr. Grant observed, looking around for sympathy.

At that moment the hall porter touched me[Pg 72] on the shoulder. The inevitable note was thrust into my hand.

"I found this on my desk just now, sir," he announced, in answer to my look of enquiry. "Sorry I can't tell you how it got there."

I opened it and read:

You will terminate your engagement at the Crown this evening. Proceed to London to-morrow, where you will find rooms taken for you at the Mayfair Hotel. Accept any offer you may receive of a lift to London, individually or collectively.

I showed Leonard the note, and hurried away to the manager's office. He made no difficulty about letting us go; in fact, I gathered that half the residents in the hotel were hurrying away by motor car, fearing a general confiscation of petrol. He detained me just as I was leaving the room.

"Queer affair, that attempted robbery, Mr. Lister," he remarked.

"Extraordinary," I agreed.

"I notice you people seem quite friendly with Mr. Kinlosti," he continued. "Do you[Pg 73] know if it is true that he is related to the late Tsar?"

"I have no idea," I answered. "All that he has told us is that he was a member of the household."

"He may be a nobleman, and I dare say he is," the manager went on, a little nervously, "but I don't care about people at my hotel with a savage manservant like his and half a million pounds' worth of jewels. Bath isn't the place for that sort of thing. My clients like a quiet life."

"No doubt," I answered. "Anyhow, he's leaving to-morrow."

"Prince or no prince, I am glad to hear it," was the heartfelt reply. "People ought to deposit valuables like that in a bank. They're simply asking for trouble when they cart them about the country. It's a thing I've very seldom done to a client, but I told Mr. Kinlosti this evening that I should be glad for him to leave as soon as convenient."

I went back to the corner where I had left Rose. My disquietude increased as I approached. Both she and her companion were[Pg 74] quite unconscious of my coming. Kinlosti was leaning forward, talking earnestly, and Rose was listening with a queer and unfamiliar look in her eyes. Leonard suddenly gripped me by the arm and led me a little distance away.

"Maurice," he confided, "that fellow Kinlosti is making love to her."

"If I thought so!" I muttered, clenching my fists.

"But she's letting him," Leonard groaned. "What the mischief can we do? We've no hold over her. Owing to that silly bargain we made, she doesn't dream that either of us care a snap of the fingers about her, except as a little pal and a partner. It's all clear sailing for that unwholesome brute."

My anger died away, but a very solid determination was there in its place.

"Leonard," I said, "we aren't going to leave her, and whatever happens, we'll know more about that fellow before many days have passed."

I retraced my steps then and went up to them. There was certainly a change in Rose's[Pg 75] face. Kinlosti looked up at me a little impatiently.

"Is it late?" he asked. "I am leaving to-morrow, and I am anxious to have a few minutes' more conversation with Miss Mindel."

"As it happens, we are leaving ourselves," I replied. "I thought perhaps that Miss Mindel would like to know."

"What, to-morrow?" she exclaimed.

"I have received a message," I told her.

She sprang up and drew me to one side, with a little nod to Kinlosti which seemed to promise a swift return. I showed her the typewritten sheet.

"Maurice," she whispered, "Mr. Kinlosti has already been begging me to accept a seat in his car to London to-morrow."

"Indeed!" I answered coldly.

"Of course, I never had any idea of leaving you two," she went on, "but now—well, you see what our instructions are."

"Damn our instructions!" I muttered, losing control of myself for a moment. "Rose, you're not falling in love with that fellow?"

[Pg 76]"Don't be foolish, please," she answered, "and don't call him a fellow."

"I'll call him a scoundrel if he behaves like one," I retorted.

She looked at me queerly for a moment. I thought that she was going to be angry, but she answered me without any signs of ill-feeling.

"You and Leonard are both very kind in looking after me," she admitted, "but after all I am quite able, when it is necessary, to make up my mind for myself on things that concern me personally."

"You're not going up to London alone with Kinlosti," I said doggedly.

She swung around and rejoined him before I could reply. Leonard and I went and fetched our coats and hats. A little ostentatiously we laid her fur coat upon the top of the piano and waited. In a moment or two she got up and came over towards us, Kinlosti by her side. He turned courteously to me.

"Miss Mindel reminds me that you also are leaving Bath to-morrow. I have two seats in my car, one of which I have offered to Miss[Pg 77] Mindel. If the other is of any service to you, I shall be delighted."

I thanked him a little perfunctorily.

"We don't, as a rule, separate when we have a journey to make," I said. "However, in this case the circumstances are a little exceptional. If you will take Miss Mindel and Mr. Cotton, I dare say I can manage to get up somehow."

"We can't leave you, Maurice," Rose protested.

"So far as I am concerned, I am afraid it must be so," Kinlosti intervened, in a tone full of courteous regret. "I have John outside with the chauffeur, and there is only room for two comfortably in the inside. We shall have to improvise a seat for Mr. Cotton."

"You don't anticipate any adventures on the way, I suppose?" I asked. "Nothing after the style of this evening's happenings?"

"I sincerely trust not," was the earnest reply. "However, both John and I are armed, and I do not think any one will venture so far as to hold up the car."

"In that case, Rose," I said, "I think you and Leonard had better accept Mr. Kinlosti's[Pg 78] offer. At the worst I hear there are some char-à-bancs running. I shall probably get a lift. At what hour did you think of starting?"

"At nine o'clock, if Miss Mindel doesn't mind," Kinlosti answered hastily. "The sooner we get away, the better. My chauffeur tells me that they are asking two pounds a tin for petrol, and a Government order, commandeering stocks, is expected out to-morrow."

We were more silent than usual on our walk home, perhaps because the events of the evening had left us all something to think about. Once Rose pressed my arm.

"I feel rather mean about you to-morrow, Maurice," she ventured.

I reminded her of the mandate we had received.

"No help for it. Two were invited and two have to go. I can't tell what surprises may be in store for me. I may get an invitation myself."

Rose turned a troubled face towards me. Her lips quivered a little, her eyes were full of distress.

"Maurice," she confessed, "I'm afraid of[Pg 79] to-morrow. I'm afraid that we are being made use of to rob Mr. Kinlosti."

"Can't be helped," Leonard put in, as I remained for a moment silent. "We took this business on with our eyes open. Our consciences weren't very active when we were starving and cold and in debt. It's no good finding them too sensitive now that we're living on the fat of the land. We've just got to see the thing through, for a year, at any rate."

"Leonard is right," I assented. "We've got to grin and bear it. This time," I added, "it seems as though you two were going to have the show to yourself."

"You can have my share," Rose sighed.

The hall of the Crown Hotel at a few minutes before nine on the following morning presented a scene of curious animation. All trains had ceased to run, and rumours as to the Government commandeering of petrol were universal. Fully a score of cars were outside, waiting, besides one of the smaller char-à-bancs, and half a dozen luggage porters were working their hardest. Kinlosti, looking[Pg 80] curiously shrunken in a great fur coat, pale and nervous, greeted us on the steps. His car, laden with luggage, stood at the entrance. On the box seat sat John, an immovable figure of fierce watchfulness.

"We could start any time you liked," Kinlosti said, addressing Rose eagerly. "We have left room for your trunk behind, and there will be a quite comfortable place for Mr. Cotton. You are ready, Miss Mindel?"

"Quite," she answered.

He gripped Leonard's arm and commenced to descend the steps. It was obvious that he was in great pain, and I supported him on the other side. Outside, a grey mist hung over the street, and he shivered as we made our slow progress.