* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Birdikin Family

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Archibald Marshall

Date first posted: Sep. 12, 2013

Date last updated: Sep. 12, 2013

Faded Page eBook #20101007

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Ross Cooling, Mark Akrigg & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Thanks are due to the Proprietors of Punch for their courtesy in allowing these stories and many of the illustrations to be published in this volume.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | A Walk with Papa | 1 |

| II. | The Results of Disobedience | 7 |

| III. | The Poacher | 13 |

| IV. | A Visit to the Sea | 20 |

| V. | The Birthday Gift | 27 |

| VI. | The Birthday | 33 |

| VII. | An Afternoon's Play | 39 |

| VIII. | A Talk with Mama | 46 |

| IX. | An Errand of Mercy | 53 |

| X. | A Game of Red Indians | 60 |

| XI. | An Unfortunate Encounter | 66 |

| XII. | An Amateur Conjurer | 72 |

| XIII. | Miss Smith Gives Notice | 79 |

| XIV. | Miss Smith Remains | 86 |

| XV. | The Lost Bracelet | 92 |

| XVI. | Fanny Runs Away | 99 |

| XVII. | The Bishop's Visit | 105 |

| XVIII. | The New Rector | 111 |

| XIX. | A Hunt Dinner | 118 |

| XX. | A Misunderstanding | 125 |

| XXI. | A Lawn Meet | 131 |

| XXII. | An Engagement | 137 |

| XXIII. | A Marriage | 143 |

| XXIV. | Farewell to the Birdikins | 149 |

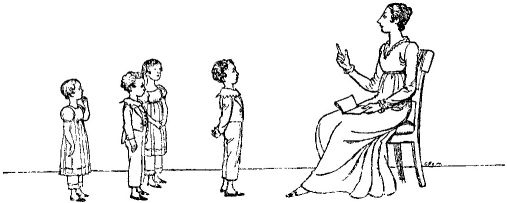

'Come, children,' said Mrs. Birdikin, entering the breakfast-parlour where the four young Birdikins were plying their tasks under the supervision of Miss Smith, 'your good Papa is now able to resume walking exercise and wishes that you should all accompany him on this fine morning, if Miss Smith will kindly consent to release you half an hour earlier than customary.'

Miss Smith, who occupied the position of governess at Byron Grove, the country seat of Mr. Birdikin, was a woman of decent but not lofty parentage, whom her employers treated almost as they would have done if her birth had been equal to her integrity. This toleration, which so well became persons of a superior station, was exhibited on this occasion by Mrs. Birdikin's asking permission of Miss Smith to cut short the hours devoted to study instead of issuing a command. Miss Smith was deeply conscious of the condescension thus displayed and replied in a respectful tone, 'Indeed, ma'am, the advantages that my little charges will gain from the converse of my esteemed employer, while engaging in the healthful exercise of perambulation, would be beyond my powers to impart'.

Mrs. Birdikin inclined her head in token of her appreciation of the propriety of Miss Smith's utterance and said, 'Then go at once to your rooms, children, and prepare yourselves for the treat in store for you'.

The four children trooped obediently out of the room, the two boys, Charles and Henry, politely making way for their sisters, Fanny and Clara; for, although their superiors in age, they had been taught to give place to the weaker sex, and invariably did so when either of their parents were by.

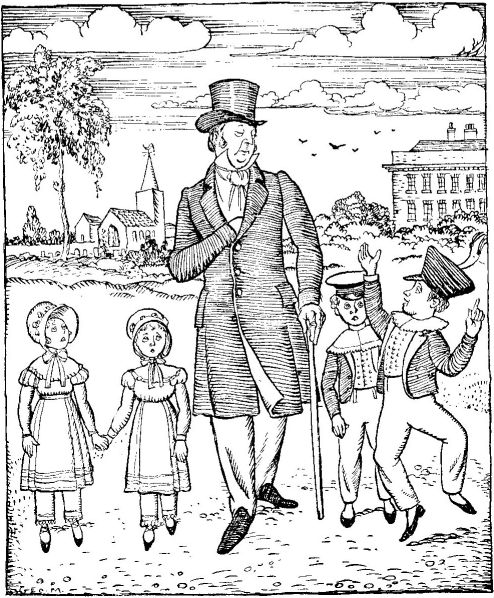

It did not take the little girls long to array themselves in their bonnets and tippets, nor their brothers to prepare themselves in a suitable manner for the excursion. When they were assembled in the hall Mr. Birdikin made his appearance from the library. John, the footman, who was in attendance, handed him his hat, gloves, and walking-cane, and the condescending word of thanks with which he was rewarded sent him back to the domestic quarters of the house in a thankful spirit at having taken service with so excellent a master, who seldom raised his hand in anger against a menial and had never been known to enforce his instructions by an oath. Small wonder then that Mr. Birdikin received willing service from those in his employ, who were assured of a comfortable home and such moral instruction as was suited to those of an inferior order, unless some serious delinquency should bring about their dismissal or illness render them no longer capable of performing the duties of their station.

It was Mr. Birdikin's custom in these delightful walks with his children to question them upon the course of study they were pursuing with Miss Smith and to distribute commendation or censure according as they acquitted themselves well or ill in his examination. But he was well aware that allowance must be made for the natural exuberance of young children, and that you could not expect old heads to grow on young shoulders. He was thus always ready to listen to their remarks as long as they were addressed to him in a proper and respectful manner.

'I am rejoiced, dear Papa,' said Charles, a bright-faced lad of some eleven summers, whose natural high spirits caused him to leap and caper as they walked down the handsome carriage-drive, 'that you are now able to use both your feet. At the same time I should prefer to keep one of my own feet on a rest rather than engage in uncongenial occupations.'

'So would not I,' said Henry, whose more thoughtful disposition seemed to mark him out even at that early age for the clerical profession, in which his maternal uncle held Episcopal office and had preferments of considerable emolument in his bestowal, to one of which Henry might well look forward. 'To my mind a life of benevolent activity is preferable to one of idleness, and I would invite our dear Papa to judge between us in this matter.'

'I have no hesitation, my dear Henry, in pronouncing in your favour,' said Mr. Birdikin, 'and if your brother will consent to use the two members of which he has so lightly expressed himself anxious to pretermit the use of one, instead of bounding about in what I can only refer to as a caprine manner, I will endeavour——'

Here he was interrupted by Fanny, a child of a somewhat sullen and intractable disposition, who inquired, 'Is it true, Papa, that an attack of gout is brought on by overindulgence in the pleasures of the table?'

'And pray where, Fanny,' inquired Mr. Birdikin in his turn, 'did you acquire an idea so unsuited to the intelligence of one of your years?'

His countenance displayed signs which Clara, who was known in the family as the Little Peacemaker, interpreted as indicative of annoyance. Anxious that the harmony of the expedition should be preserved, she hastened to say, 'My sister inquired of Dr. Affable the cause of your ailment, dear Papa, and he informed her that it was sometimes brought on by partaking to an excessive extent of port wine; but——'

Here she was interrupted by Charles who remarked, 'When I grow to manhood I shall drink three bottles of port wine with my dinner every day.'

'So shall not I,' interpolated Henry, 'for do we not read that wine is a mocker, strong drink is raging?'

This apposite remark caused Mr. Birdikin's brow to relax. 'I am glad,' he said, 'that at least one of my children has learnt to express himself with propriety on a question somewhat beyond childish intelligence. Our good Dr. Affable has no doubt had experience of ill-regulated lives where excess has led to bodily ailments. In my case the malady with which I have lately been visited is the result of a possibly over-anxious regard to the performance of my duties and a consequent disregard for my own health.

'But, come, children, let not our walk be wasted in idle discourse. You have the advantage of the instructions of a preceptress whose lack of breeding must not blind you to the admirable use she has made of her understanding. You, Charles, subdue your spirits to a reasonable degree of quietude and inform me to what subject of study your attention was directed this morning.'

Charles, thus admonished, put a curb upon his tendency to leap and curvet and replied with propriety that he and his brother and sisters had been instructed in the use of the Globes. This gave Mr. Birdikin the opportunity of putting various questions suited to the intelligence of his young hearers and administering correction and reproof in such a way that the limits of the walk were attained with profit to all and enjoyment to some.

Fanny, however, whose answers to her father's questions had betrayed a lack of application to the subject in hand that had brought her within measurable degree of a threat of punishment, did not show that spirit of gratitude for the condescension of a kind parent in devoting himself to the instruction and entertainment of his children that could have been wished. As she and Clara were removing their outer garments upon their return from the expedition Clara said to her, 'Are we not fortunate, sister, in the possession of a Papa who, with a mind so well stocked with knowledge, is anxious to put it at the disposal of his children?'

'I apprehend,' replied Fanny, 'that my Papa does not know so much as he thinks he does.'

'Disrespectful child,' ejaculated Clara, the blush of indignation mantling her cheek, 'to speak thus of a kind and indulgent parent! Fie! For shame!'

'Fie to you!' replied the unrepentant Fanny.

And there we must leave our young friends for the present.

The parish in which Byron Grove, Mr. Birdikin's country seat, was situated, was served by a curate of the name of Guff, who was possessed of a considerable family of young children. It speaks well for the unworldliness and condescending kindness of Mr. Birdikin that he should not object to the young Guffs consorting at times with his own children, upon whom he impressed it that poverty was no crime where conduct was satisfactory, and that on no account were the curate's children to be twitted or quizzed on account of their inferiority.

One fine afternoon, two of the Guff children, Thomas and Lucy, were invited to Byron Grove to play with Charles, Henry, Clara, and Fanny. It was usual for Miss Smith to be with the children when they thus disported themselves, but that afternoon Mrs. Birdikin had requested of the governess that she should go through her linen-cupboard with her, and Miss Smith, sensible of the compliment, had put her services at the disposal of her kind employer, adjuring her young charges not to lead their visitors into mischief nor be drawn into the same themselves.

'Well, what shall we do?' cried Charles brightly as the six children found themselves in the handsome grounds surrounding the stately residence. 'My own preference is for a game of tag, if our young guests have no better suggestion to offer.'

'I opine,' said Henry, 'that in view of the sacred character of their parents' calling Thomas and Lucy would prefer a less frivolous occupation. Can we not play at visiting the sick poor? The strawberries are now in season, and those of us who are deputed to bring delicacies to the sufferers can first visit the kitchen-garden.'

All the children clapped their hands at this, except Clara, who said, 'Are you not aware, brother, that our parents have forbidden us to regale ourselves with fruit from the garden except under the supervision of Miss Smith?'

'It would ill become me,' replied Henry, 'to counsel disobedience to a direct command of our parents; but I apprehend that the prohibition would not apply to a diversion of which they could not but approve. You, Thomas, shall take the part of the sick labourer, if you are willing, in what is only a game, to divest yourself of that degree of gentility to which you can lay claim. You, Fanny, shall be the labourer's wife and Clara their daughter. Charles and Lucy will represent the Squire and his lady, and I will content myself with playing the part of the apothecary summoned to attend the sufferer.'

'Will the apothecary himself partake of the delicacies to be conveyed to the sick poor?' inquired Fanny. But Henry made no reply to this question.

The children then devoted themselves to adapting one of the summer-houses, of which there were several in the spacious grounds of Byron Grove, to the simulacrum of a sick-chamber. Miss Smith, relieved for a few minutes from her attendance upon Mrs. Birdikin, who was accustomed to partake of a glass of sherry wine and some light and delicately prepared viands at this time of the afternoon, now came into the garden, and, finding the six children so innocently employed, retired with a word of commendation to her chamber until it should be time to attend again upon Mrs. Birdikin. Her frame was not robust, and her anxiety to save her kind employer undue exertion had led her to take upon herself the heavier duties of the afternoon's occupation, while Mrs. Birdikin sat upon a low chair and directed her. But, though her body was aching, her heart was full of thankfulness at the consideration with which she was treated in this pious and superior family, and, after lying for a few minutes prone upon her bed, she returned to take up the part assigned to her, little thinking of what was going on among those whom she would otherwise have been supervising.

No sooner had the summer-house been arranged for the scene of the little drama so happily projected, and Thomas, Fanny, and Clara left there to prepare for their parts, than Fanny said, 'Let us hide from them.' She ran out of the arbour, followed by Thomas, but Clara remained there, being unwilling, even in play, to depart from the strict rectitude enjoined upon the Birdikin children from their earliest years.

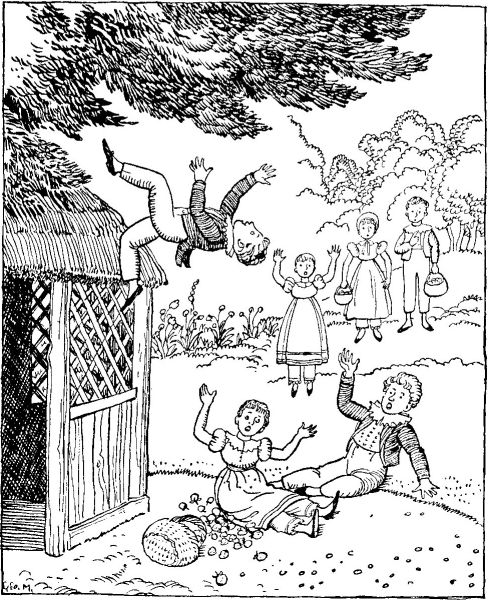

No high degree of censure, however, would have been merited for what would have been no more than an additional mystification introduced into a game of make-believe, but Fanny's next step was a definite invitation to her young guest and companion to an enterprise by no means innocent. This was to climb on to the roof of the arbour, a proceeding involving not only indelicacy on the part of a female, however young, but danger to life and limb for both of them.

It may be urged that Thomas, being the son of a clergyman, who, although not beneficed, was yet the official guardian of parochial behaviour, should have protested. It would have been well if he had reflected for a moment that what in Fanny might have been a venial fault, in him, admitted so generously to the companionship of children vastly superior to himself in station, could only be looked upon as presumption. Alas! the careless boy gave way instantly to the temptation, and even assisted Fanny to clamber up to the roof of the arbour, where they ensconced themselves, concealed by a yew which overhung it, and waited for the return of their playmates.

In the meantime the other children had repaired to the strawberry-beds with their baskets, which they piled up with the luscious fruit, filling their mouths at the same time to an extent far in excess of the requirements of the little drama they were enacting.

They then returned to the summer-house, now supposed to be the homely cot of a tiller of the soil. There they were met by Clara, who had in vain tried to persuade Thomas and Fanny to descend from their hiding-place. She at once disclosed their situation, to the intense annoyance of Fanny, whose ruse was thus discovered. 'Tell-tale!' she cried, and before the word was well out of her lips she had slipped from the precarious slope of the roof and fallen upon Henry, whom she bore to the ground, upsetting the basket he was carrying and ruining her freshly-washed and ironed cotton frock with the juicy fruit, upon which she subsided in a sitting posture.

Fanny's fall had been broken by her collision with her brother. Not so that of Thomas, whom her sudden movement had also dislodged. He fell sheer to the ground, and, instead of rising at once to take part in the angry dispute now proceeding amongst the rest, he lay there groaning.

In response to the cries of the frightened children Miss Smith came running out, followed by John the footman, who lifted Thomas in his arms and bore him into the house, where it was discovered that his discreditable prank had resulted in a broken leg. It was not until Dr. Affable had been sent for and put the limb into splints that Thomas was sent home in Mr. Birdikin's carriage with a note to the curate begging that he should not be further punished for his delinquency and stating that Mr. Birdikin would himself defray the cost of the requisite medical attendance in view of Mr. Guff's straitened circumstances.

This large-hearted generosity towards the curate's child was all the more meritorious since Mr. Birdikin judged it necessary to take a severe view of the misconduct of his own children. As he had no mind to differentiate the degrees of blame attached to each, all were soundly whipped and sent supperless to bed. The tears of all indicated that repentance had come home to them; but Fanny, who had been chiefly responsible for the misconduct that had had such serious results, confided to her sister that her only regret was that she had not eaten her share of the strawberries before sitting on them.

Mr. Birdikin was not himself an adept with the fowling-piece. He saw nothing wrong in the pursuit of fur and feather, judging that birds and animals suitable for human consumption were intended by an all-wise Providence to appear roasted or boiled on the tables of those whose worldly circumstances entitled them to partake of the more costly viands. But some slight obliquity of vision, not otherwise noticeable, made him an indifferent marksman, and a disinclination for the more arduous forms of bodily exercise, resulting in an increase of girth about the midriff, had caused him some years before to relinquish the pursuit of a sport for which he felt himself unfitted. He had at the same time given up preserving feathered game in the woods and fields of his demesne, but members of the coney tribe abounded there, and birds from the coverts of his neighbours, the Earl of Bellacre and Captain Rouseabout, not infrequently transferred themselves to those of Mr. Birdikin.

One of his numerous outdoor staff was deputed to keep down the vermin and to supply his master's table with the toothsome trophies of his gun or his traps, and Mr. Birdikin was wont to prefer the modest boast that his requirements in the way of game when in season were as fully met as those of his neighbours, and at a tithe of the expense to which they were put.

One morning this man Shotter came to his master and informed him that a cottager of the name of Onion had regaled his family the day before with a rabbit, which had no doubt been illicitly snared on Mr. Birdikin's property. It was not the first time that the savoury smell of this rodent had been detected coming from Onion's dwelling, and Shotter, devoted to his master's interests, respectfully suggested that it was time that a stop should be put to his depredations.

Mr. Birdikin judged it his duty to pursue the matter. Onion had been employed in a boot and shoe factory in the neighbouring town, and inhabited a hovel on the outskirts of Mr. Birdikin's estate, from which he could not be dislodged, as it was his own freehold. He was an unsatisfactory character, never attended the ministrations of Mr. Guff, the excellent curate, and had been known to utter subversive sentiments on the subject of landowners in general and Mr. Birdikin in particular over his potations in the 'Pig and Whistle'. In spite of all this, Mrs. Birdikin, a true Lady Bountiful, had included this man's wife and children in the visits she paid to the cottagers on her husband's estate, and since Onion had lost his employment she had given instructions that the scraps from her own table should be supplied to his wife, if called for, and only that morning had picked out a suitable tract on the sin of gluttony to be added to the eleemosynary gift. Small wonder then that Mr. Birdikin's gorge was aroused at the ingratitude and dishonesty brought to his notice. As a magistrate of the county he sent instructions to a police constable to take Onion into custody, and before night fell he was safely lodged in gaol.

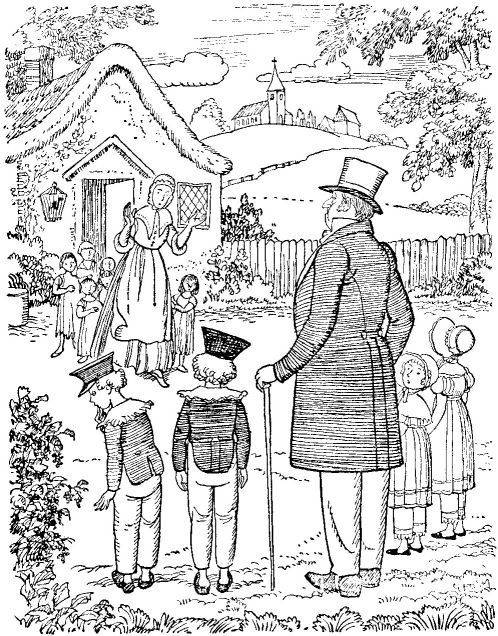

So far the dictates of right and justice had been followed, but Mr. Birdikin's large-minded humanity forbade his including the innocent victims of Onion's turpitude in the punishment he designed for the perpetrator himself. The next morning, in his daily walk with his children, he directed their footsteps to Onion's dwelling, and on the way thither expounded in a manner adapted to their immature understanding the iniquity which he had felt himself bound to punish.

'You will see for yourselves,' he said in conclusion, 'the misery which the turpitude of a husband and father has brought on a comparatively innocent family. The wife is culpable in so far as she cooked the stolen food and the children are to be blamed for having consumed it; but we whose table is bountifully spread may make allowances for those whose food supplies are intermittent, and I do not propose to take further notice in their case of an offence of which I feel bound to exact the full penalty in his.'

'If I were hungry,' said Charles, 'I should eat all the rabbits I could find, and the pheasants too.'

Mr. Birdikin's brow darkened at the thoughtless disposition thus displayed by his elder son, but before he could express his displeasure Henry, who was more responsive to the training he was endeavouring to impart to his children, said, 'So should not I. Our father has continually impressed upon us that the rights of property are sacred, and I would sooner starve than lay a finger on what was not mine'.

Mr. Birdikin was about to commend the propriety of this utterance, but before he could do so Fanny broke in with the question, 'Then why did you gobble up all the comfits that our aunt brought for us yesterday?'

Clara, the Little Peacemaker, hastened to intervene. 'My brother thought they had been a present for himself,' she said, 'and as he was under that misapprehension I willingly resigned to him my share of the dainties.'

'After he had filled his belly with them,' said Fanny, whose propensity to pick up coarse expressions from the stable-lads and others of the lower orders employed in her father's stylish establishment caused her excellent parents much concern.

The rebuke administered by her father withdrew attention from Henry's unfortunate mistake, and by the time it was ended they had arrived at the lowly cot which was the objective of their excursion. Here they were met by Mrs. Onion, who ran out to her benefactor, with half a dozen ragged children hanging on to her skirts, and implored him to have pity upon an innocent man. 'Indeed, your Honour,' said she in her rustic jargon, 'the rabbit were not snared by my Jarge. It come into the garden and was nibbling of our cabbages when it fell down dead, and all we done was to skin it and put it in the pot.'

Mr. Birdikin was not unmoved by this address, and was proceeding to inquire of her the manner of the rabbit's decease, not being without the suspicion that its life had been ended by violence, when her respectful demeanour suddenly changed. She pointed her finger at Henry and shrieked out, 'Who's the thief now? Get out of my sight you old sarpent, and take your greedy brats with you. I'll have the law on you now. Get out!'

The cause of this deplorable outburst, so little to be expected from one who owed so much to Mr. Birdikin's bounty, was that Henry had picked a bunch of currants from a neighbouring bush and was eating them when the woman's eye fell upon him.

The full weight of Mr. Birdikin's displeasure at her outrageous speech and demeanour would have fallen upon her, but she had retired into her hovel and banged the door in his face. He judged it wiser to remove himself from the scene, all the more so as she thrust her head from the window and cried out that she suspected him of hanging about to 'pinch', as she vulgarly expressed it, the family plate, and adjured him in the most indecorous language to take himself off, and his 'spawn' with him.

'Come, children,' he said, with the dignity that he maintained under the most trying circumstances, 'let us begone. You, Henry, who have brought upon us this indecent exposure of low-breeding, shall yourself gather the twigs which I will bind into a birch for your correction. As for this no-doubt demented woman, I command you all to forget her improprieties. Those of you who disobey me, whether male or female, shall feel the weight of my hand.'

For the children the episode was ended by this command and by Henry's chastisement. For Mr. Birdikin, however, the annoyance and injury to which he had been subjected were not yet over. His upright and perhaps over-scrupulous way of conducting himself was not to the mind of his neighbour, Captain Rouseabout, who was addicted to cockfighting and other low sports, and so far forgot himself as habitually to use unseemly language in Mr. Birdikin's presence for the sake of shocking his sense of propriety. Though totally unfitted for judicial office, except in his abhorrence of poaching and poachers, he sat on the Bench as a magistrate, and when the charge was preferred against Onion had the audacity to say that it was Mr. Birdikin who should have been brought before them for shooting and trapping game reared by his neighbours. The woman Onion's counter-accusation of trespass and fruit-stealing caused Captain Rouseabout to burst into a loud and rude guffaw. She was not permitted to prefer a charge, but it was considered by Mr. Birdikin's fellow magistrates that it was a case of tit for tat, and the charge against the poacher was dismissed.

Mr. Birdikin returned home, and regained from the respect and deference of those dependent upon him the serenity which had been somewhat shaken by the annoyance he had undergone at the hands of Captain Rouseabout. In the spacious and opulent surroundings of Byron Grove he felt himself indeed a king among men, and was upheld by the conviction that such a man as his neighbour must inevitably, be it sooner or later, come to a shameful and dishonoured end.

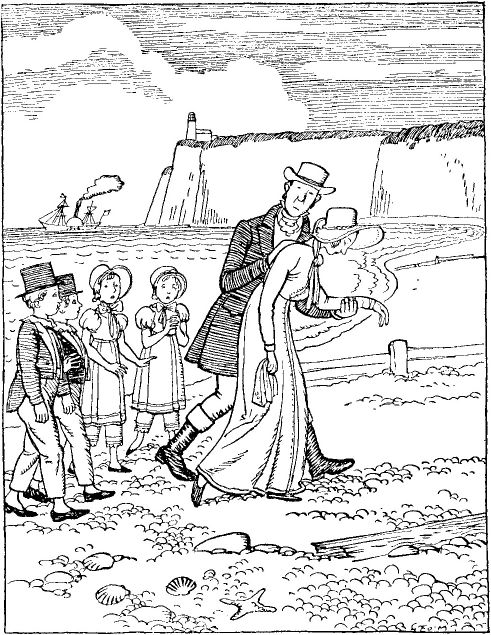

Byron Grove, Mr. Birdikin's country seat, was situate six miles from the seaside town of X, to which, when temperature and weather conditions were favourable, the Birdikin children were sometimes taken for immersion in the ocean, their parents considering that, if due precautions were taken against the dangers of sea-bathing, its benefits could not but add to their health as well as to their enjoyment.

One summer morning, when Mr. Birdikin had satisfied himself by examination of the weather-glass that no immediate change was to be anticipated in the quiescent state of the elements, the four children were sent, under the charge of their instructress, Miss Smith, to spend the day at X. The programme arranged for them, with the thoughtful foresight which Mr. and Mrs. Birdikin exercised in all the details of family life, of which they were such exemplary exponents, was that they were to be driven to the seashore, and while Bodger, the coachman, was putting up his horses the children were to perambulate the sands and the rocks and, under the supervision of Miss Smith, were to investigate such denizens of the deep as star-fishes, winkles, jelly-fish, limpets and the like as came within the range of observation, but on no account, at this stage of the proceedings, were they to get their feet wet or venture beyond the control of their governess.

Upon the return of Bodger, a respectable family man who could be trusted to act responsibly in a case of emergency, Miss Smith was instructed to engage one of the larger bathing-machines, in which the whole party would disrobe themselves, with the exception of Bodger, who would keep watch upon the beach. This accomplished, the two boys and Miss Smith would plunge into the briny element, and, upon the expiry of a quarter of an hour, to be signalled by Bodger, who would stand on the marge of the ocean with his timepiece in his hand, the two girls would take the place of their brothers, Miss Smith being instructed on no account to let go of the hands of her young pupils nor to venture beyond her own middle.

All went according to plan until Bodger signalled, by the springing of a watchman's rattle, that the time allowed for Charles and Henry was at an end. Miss Smith was gratified at the complaisant spirit shown by the boys in returning to the machine, but no sooner had she led out Clara and Fanny than Charles, instead of rubbing himself briskly with a rough towel, as he had been instructed, leapt again into the water and with gleeful shouts began to splash his sisters and the governess. In vain did Miss Smith exhort him to obedience, in vain did Bodger threaten to wade into the water himself and chastise him. The insubordinate lad continued his rough play, and Fanny, always inclined to be refractory when encouraged by Charles, who had so often been adjured to show a good example to his younger brother and sisters, entered incontinently into the boisterous and unmannerly sport, and wrenched her hand away from Miss Smith's in order that she might the better strike the water into her brother's face.

At that moment a wave advancing towards the shore dislodged her foothold, and upon its return carried her some yards away from Miss Smith. The governess, anxious to seize hold of Charles, did not notice this catastrophe for the moment, and but for the presence of mind of the bathing-woman in attendance on the machines, who caught hold of Fanny and jerked her to her feet again, one of those tragedies might have been enacted against which Mr. Birdikin had enjoined all the precautions that were humanly possible. Fanny herself made light of the incident and refused to return to the machine until her appointed time in the water was over. Miss Smith put her and Clara into the charge of the bathing-woman and carried the struggling Charles back to the machine, where she carefully dried him, and did the same for Clara and Fanny before she attended to her own toilet, after which the machine was drawn out of the water and the bathing-party regained the safety of the shore, Miss Smith in a spirit of thankfulness that the peril brought about by Charles's thoughtless prank had mercifully been averted.

Miss Smith, however, had a frame far from robust, and the anxiety to which she had been subjected, together with the chilling effect of standing in her wet but decent serge bathing-dress while she saw to the welfare of her young charges, brought on a fit of shivering and a numbness of the extremities which caused Bodger, who had been trained by his wife to take observation of female ailments, some alarm. Followed by the frightened children he supported Miss Smith up the beach and led her to the first shelter available, which happened to be an establishment devoted to the exhibition and sale of ironmongery, where he demanded succour, suggesting that it should include the administration of a measure of French brandy.

It has already been said that Miss Smith's birth was not equal to her scholastic attainments. Of this Mr. Birdikin had been aware when he had engaged her for the responsible task of administering, under his own direction, the education of his children. What she had omitted, however, to disclose to him was that in this very town of X she had relatives who were by no means of a quality suitable for notice by a man of Mr. Birdikin's superior standing. It was to these relatives that the inscrutable leadings of chance had directed Bodger's unwitting footsteps. Miss Smith's own mother's sister, Mrs. Clott, received her and gave her the willing service and relief dictated by the promptings not only of charity but of consanguinity. A kind heart is not, as some would aver, the peculiar property of those of high or even of medium birth. This good woman's first preoccupation was to administer hot toddy to her relative and put her to bed in a small but decently furnished chamber. Her next was to provide entertainment for the young children who were for the time being in her charge, the coachman, Bodger, announcing that the shock he had undergone necessitated his repairing to a neighbouring hostelry where he could obtain the refreshment required by his condition. So well did Mrs. Clott accomplish her task that when, some hours later, Miss Smith was sufficiently recovered and Bodger was summoned from the 'Mariners' Rest' to drive her and her charges home again, all four children declared that they had never enjoyed themselves better, and took leave of their kind hostess with expressions of goodwill which, coming from the offspring of a man of Mr. Birdikin's superior station, must have caused her considerable gratification.

The adventures and alarms of the day were not yet quite over, for Bodger had not entirely recovered from the agitation that Miss Smith's indisposition had caused him, and showed less than his usual skill on the driving-seat, the carriage deviating from side to side of the road and narrowly escaping reversal in a ditch. Home was reached, however, without actual mishap, and Mr. and Mrs. Birdikin were put in possession of the details of the day's happenings.

It may be imagined that Miss Smith was far from being at her ease over the accident that had led to the children being received in the dwelling of her aunt, for Mr. Birdikin, taking into account the inferiority of her origin, had impressed upon her that it was her special duty to preserve her little charges from contact with anything low. He was inclined, however, to judge her part in the affair leniently, only remarking that had he been aware that she had relatives engaged in retail trade at so short a distance from Byron Grove as the town of X, he might have thought the risk of engaging her too great, and that she would do well to consider the indisposition she had herself experienced as a punishment for her lack of frankness. He could not, of course, countenance any further personal communication with Mrs. Clott, but, in consideration of the seemly way in which she had dealt with the situation, he intimated his intention of transferring his custom from the ironmonger whom he had hitherto honoured with his patronage to Mr. Clott. Thus the dictates of propriety and urbanity were alike honoured, and Miss Smith retired from the interview with a deep sense of the tolerance and benevolence of her employer.

Mr. Birdikin's displeasure with Charles and Fanny for their unprincipled conduct was expressed by a few sharp strokes of the rod for the boy and of the bare hand for the girl. But Fanny's punishment, alas, did not incline her to that compliance of the heart which she had promised with the lips. Her experience of the more obscure ranks of society, by which her excellent parent was above all anxious that his children should not be contaminated, had made no deeper impression upon the heedless child than to cause her to confide to her sister that when she attained maturity she should ally herself in wedlock to an ironmonger and live at the seaside.

The birthdays of the young Birdikins were always made occasions of innocent enjoyment, and high were the anticipations of pleasure with which all four children awoke on the morning upon which Charles entered upon his thirteenth year. No lessons would be required of them, and Miss Smith would be released altogether from her usual attendance upon her young charges, being set free for the soothing occupation of darning their stockings and seeing to the buttons on their underwear, and at full liberty to use what leisure remained over for the pursuance of her own pleasure, so long as it was such as to meet with the approval of her employers.

'Well, my dear Charles,' said Mr. Birdikin when he had received his son's morning duty and congratulated him upon the attainment of another step in life's journey, 'as you have now reached the ripe age of twelve I conjecture that you will scarcely expect to receive the commemorative gifts with which such an occasion as we are now celebrating has been marked in your more immature years.'

Charles's face fell, and Mrs. Birdikin made haste to say, 'Your papa's remark, Charles, is made in a spirit of whimsicality. Pray accept from your mother this volume of virgin paper, bound, as you see, in blue morocco with your initials stamped upon it in gold, in which you are invited to set down such moral reflections as occur to you from time to time, or such as you may derive from your day's reading.'

To this handsome and timely gift were added those of Charles's brother and sisters, prepared under the advice of their parents and the supervision of Miss Smith. These were a volume of sermons by their kinsman, the Lord Bishop of P——chester, from Henry, a warm muffler knitted by her own hand from Clara, and from Fanny the Golden Rule, illuminated in colour by herself and suitably framed for suspension over her brother's bed.

When the expressions of pleasure drawn from the delighted lad over these tokens of fraternal affection had subsided, Mr. Birdikin said, still in that vein of drollery with which he was accustomed to temper the authority of a parent at such times of relaxation, 'For the enjoyment of your father's gift you must wait, my dear Charles, until the claims of appetite have been satisfied. Its immediate contemplation, however, need not be denied you. Come hither.'

With this he led the expectant stripling to a window which commanded a view of the sweep of gravel in front of the mansion. Usually empty at this time of the morning, this was now occupied by the figure of Bodger, the coachman, who was leading a beautiful little Welsh pony, which at a signal from his master he now brought up to the window.

The delight of the fortunate lad at this munificent gift, which marked alike the generosity and the affluence of a fond parent, knew no bounds. Each child in turn was permitted to administer a lump of sugar to the pony, and when at last it was led away by Bodger and the family seated themselves at table it formed the subject of gleeful anticipation, in which all joined, though the enjoyment of the gift was at present to be confined to one.

This was explained by Mr. Birdikin, when he judged that the natural exuberance of childhood had had sufficient scope and that it was time that the voice of authority should be heard. 'I confess,' he said, 'that it was not without some hesitation that I decided to introduce Charles to the science of equitation at this early age. A moderate degree of skill in the use and management of the equine race is becoming to a gentleman, and I myself in my earlier years frequently took pleasure in bestriding a horse.'

'Papa on a horse!' ejaculated Fanny with a laugh. 'That would indeed be a sight to induce mirth.'

Mr. Birdikin's brow darkened. 'Pray subdue your tendency to untimely cachinnation, Fanny,' he said. 'With the increasing bulk that attends middle age in those whose duties call them to occupy their time in sedentary postures I relinquished the use of the saddle some years ago. But as a young man of some consequence I obeyed the wishes of my own father in joining in the pleasures of the chase, and was known far and wide as an intrepid pursuer of the vulpine species.'

'I well remember,' said Mrs. Birdikin, 'being carried in my father's chariot to a meet of the foxhounds. The mark made upon the heart of a modest but not unsusceptible maiden by the sight of your father seated erect upon his elegant steed led eventually to that happy union to which my children owe their being. Do you recollect, Mr. Birdikin, how one of the accidents attendant upon the manly sport led to your being deposited by your mettlesome mount in a duck-pond, and how the proximity of the carriage in which sat a young girl hitherto unknown to you enabled you to be conveyed back to your home with no further damage done than the spoiling of your fine scarlet coat and the risk of a rheumy distemper owing to your immersion, which was mercifully averted by an immediate retirement to the shelter of the blankets?'

'To that fortunate accident,' returned Mr. Birdikin with a courteous inclination of the head towards his helpmate, 'and to the handsome inheritance to which I succeeded not long afterwards I owe whatever satisfaction has hitherto attended me in my progress through this vale of woe.' He then explained that upon the demise of his father and his own approaching marriage he had thought it right to pretermit his pursuit of the dangerous sport of fox-hunting. 'But,' said he, 'I am not unmindful of the preoccupations that beset adventurous youth. You, my dear Charles, have already bestridden the homely and serviceable Jackass. You will now, under the tuition of our good Bodger, proceed somewhat farther by learning to control and guide your Pony; and it is my desire, if I am spared by Providence, to see you some day holding your own in the mimic contest of the chase on a Horse.'

'Indeed, Papa,' returned Charles, 'I shall do my utmost from henceforth to deserve the confidence you have so amiably displayed towards me, and trust you will no longer have to rebuke me for the thoughtless disposition which I am fully aware has given you cause for displeasure in the past.'

'There speaks my own son,' said Mrs. Birdikin, whose preference, if preference she had with regard to her offspring, was towards the mercurial Charles rather than to the more temperate Harry, in spite of the latter's closer resemblance to his worthy father. 'I conceive, Mr. Birdikin, that your birthday gift could not have been better bestowed than upon one who at so early an age shows himself anxious to leave the delinquencies of childhood behind him.'

'From henceforth,' said Clara, with the placable smile that so well became her childish features, 'I shall look to my brother for an example of that behaviour that is to be expected by our parents from all of us.'

'With that sentiment I would associate myself,' said Henry, 'while reserving to myself the right of resisting it should I not consider it of such a character as it would become me to follow.'

'You will always be at liberty,' remarked Fanny, 'to set your own example, which I do not myself propose to follow under any circumstances whatever.'

These several remarks may be taken as indicative of the widely different dispositions already showing themselves in the Birdikin children, and of the wisdom required from their parents in influencing them towards that stability of character to which all their efforts as right-living people not without consequence among their more highly-placed neighbours were directed.

For an account of the proceedings of a day so auspiciously begun we must postpone the expectations of our readers until a further chapter.

Mr. Birdikin, with that degree of worldly wisdom with which he tempered the promptings of a mind as much set upon morality as was consonant with his position as a man of property, had decided that upon the twelfth birthday of his elder son he would make known to him the place in life which he was called upon to fill. Before the diversions with which the day was to be marked were begun, therefore, he summoned the four children into the library, for he deemed it wise that all should hear the words addressed to Charles, and for their own sakes learn to estimate aright the subordinate position to which the females and the younger sons of a family of Quality were called upon by the designs of Providence to occupy.

'You, my dear Charles,' said he, 'will succeed me in the ownership of Byron Grove and the general esteem that goes therewith when I shall be called upon in the course of nature to lay down my earthly dignities and, as it were, to go up higher. It is my earnest desire that in the meantime you should fit yourself, by due observance of the rules of conduct in which you have been nurtured, to take that place in the world in which I trust that I myself have been proved not unworthy. While a reasonable enjoyment of wealth and position is proper to, nay, even demanded from, a man of consequence—otherwise why should he have been placed in a position of superiority?—you must not forget the welfare of those dependent upon you. As long as they remain contented with their lot in life and seek not in any way to claim equality with you or, as the dangerous and subversive phrase has it, to better themselves, it will be your part to smooth their path for them, so that neither man, woman, nor child on your estate shall actually starve, though the unavoidable exigencies of life may sometimes compel them to go what is called short; and, what is more important still, that none of those dependent on you shall be permitted, under pain of losing your countenance and support, to bear themselves in a manner unbecoming in those of an inferior order.

'To you, my dear Henry, is allotted a task of scarcely less importance. You will not enjoy so much of this world's goods as your elder brother, though, with the advantages that will come to you from your relationship to a high dignitary of our established and well-endowed Church, it is to be expected that early preferment to a position of handsome emolument will be found for you. It will be your part to watch over the morals of the flock that will be committed to your charge, and to keep them submissive to their betters and as uncomplaining as possible under such visitations of poverty and hardship as are sent to them as a reminder that they cannot expect to have it all, or even the greater part of it, their own way.

'You, Clara and Fanny, have been sent into the world in the inferior position of females, but you need not let that unduly disturb you. Woman was intended to be the solace and encouragement of man, and in due time, if you comport yourselves with that allurement combined with modesty with which your sex has been endowed with the express object of attracting to itself the notice of the other, you will obtain husbands capable of supporting you either in sufficiency or affluence according as you make use of your opportunities, helped by the efforts of your parents, which will not be wanting to bring about the desired results. I should wish you all now, during the half-hour which will elapse before we engage in the pleasures in store for us, to exercise your minds in retirement upon the duties of life which I have set before you.'

'But may I not, dear Papa, first make acquaintance with the pony which was your amiable birthday gift to me?' inquired Charles.

'I apprehend,' said Mr. Birdikin, 'that the pony, though reasonably fleet of foot, will not run away while you are applying yourselves to the reflections I have enjoined upon you. In half an hour I and your mother will be ready to set out on the expedition with which this festive day is to be marked. Until then you will kindly indulge me by doing as you are bid.'

'Come,' said Charles, when the four children had taken respectful leave of their parent and the door was between him and them; 'my Papa said nothing about where our colloquy was to take place. As it appears that my authority over you is to be greater than I have hitherto counted upon, I ordain that we repair to the stables and combine the duty enjoined upon us with the pleasure of inspecting my pony.'

'I would remind you,' said Henry, 'that affairs of conscience are to appertain to my department. I see nothing wrong, however, in taking the course you suggest.'

'As a member of the weaker sex,' said Clara, 'I conjecture that I shall be fulfilling my papa's behests by submitting myself to the guidance of the stronger.'

'Stronger be bl-w-d!' said Fanny, whose mischievous propensity to pick up and repeat indecorous expressions has already been commented on. She intemperately took to her heels and arrived first at the stables, where Bodger the coachman was ready to lead the pony into an adjacent paddock, where he opined that Charles would wish to mount the diminutive steed and to receive his first lesson in horsemanship.

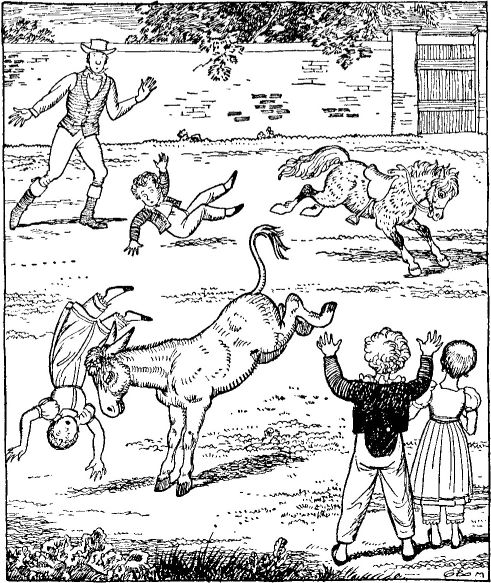

The temptation was too strong for the children to resist. Assisted by Bodger, Charles ensconced himself in the saddle and the others followed him into the paddock, where all considerations of obedience were flung aside and the injunctions of their father were as if they had never been uttered. When Charles had trotted and cantered round the paddock it was suggested by Bodger that Henry should bestride the pony, and Charles, whose generosity of nature was stronger than the sense of responsibility he had so recently promised to cultivate, gave place to him, thus countenancing on the part of Henry direct disobedience to a command of their excellent parent, who had laid it down that at present the use and enjoyment of the pony should be for Charles alone.

Nor did the matter end there, for Fanny, casting to the winds all sense of female propriety, scrambled on the back of the jackass, which was feeding in the paddock, and, sitting astride in a posture that might have brought a flush of shame to the cheek of the most hardened, urged the not unwilling quadruped, by kicking its sides with her heels, to enter into a contest of speed with the hitherto well-behaved pony.

The pony, possibly seized with a spirit of emulation, possibly contemptuous of the homely animal now first brought to its notice, suddenly quickened its pace. The guiding-rein was jerked from Bodger's hand and Henry, as yet unused to controlling his spirited mount, was deposited upon his back upon the grass. At the same time the jackass executed a sudden elevation of its hinder quarters and a playful kick at circumambient space, and Fanny was likewise unseated from her highly indecorous position and precipitated on the sward.

It was at this moment that Miss Smith, looking from an upper window, was made aware of what was going on. Horrified by what she saw she rushed headlong downstairs and made known to Mrs. Birdikin the double accident that had befallen her young charges before proceeding herself to the paddock to render what assistance it might be within her capacity to impart. She was immediately followed by Mr. Birdikin, who could scarcely believe his ears when informed by his spouse of the extent to which his commands had been disobeyed.

By a merciful interposition of Providence no harm to life or even to limb had resulted from what might have brought a disastrous end to the outrageous and lawless prank. So lost were the children to the enormity of their conduct that upon the arrival of their instructress all were laughing at the mishap, and Fanny was adjuring Bodger to 'catch the old Moke' so that she might repeat the dangerous and indelicate game.

Laughter, as may well be imagined, was quickly changed to its reverse when Mr. Birdikin appeared on the scene and without any delay administered that chastisement which the occasion demanded and a stirrup-leather made immediately convenient. The diversions by which the day that had opened so auspiciously was to be marked were countermanded, and Miss Smith was enjoined by her employer to exact double the tasks usually required of her pupils as a further punishment for their disobedience.

By these means the authority of a parent was vindicated and the path of duty was shown to be preferable to that of licence. A slight sprain of the elbow, owing to the severity of the punishment he had felt called upon to administer, was considered by Mr. Birdikin a small price to pay for keeping his children in the paths of rectitude, and he judged rightly that they would not soon forget the events of Charles's twelfth birthday.

One fine morning in September a coroneted note was brought by a mounted groom from Bellacre Castle to Byron Grove, in which the Countess of Bellacre requested that the four young Birdikins should be brought over that afternoon to play with her own children, the Viscount Firebolt, the Lady Mary, and the Honourable John Firebolt.

This invitation was gratifying to Mr. Birdikin. During such seasons as the Earl of Bellacre was in residence at his country-seat a neighbour of such probity of conduct as the owner of Byron Grove, who was always ready to unlock the treasures of a well-furnished mind when in company, might have been expected to be welcomed to frequent intercourse with him. Upon the occasions on which they met in public the Commoner had shown by his ingratiating demeanour that a fuller measure of intimacy would be agreeable to him, but the Nobleman, while treating him with the civility that became his rank, had invariably hastened to remove himself from his immediate vicinity. Mr. Birdikin, after some years of endeavouring to lessen the distance between them, had taken this to indicate that on his Lordship's part that desire was absent. This invitation, however, seemed to show that a more neighbourly intercourse was now desired. The note was answered by Mrs. Birdikin, to whom it had been addressed, Mr. Birdikin himself advising upon the wording of the missive, so that it should express the right degree of cordiality together with the deference due to the rank of the recipient.

High were the anticipations of the four children as they were carried towards the stately edifice which was to be the scene of the afternoon's play, the boys in their best nankeen suits, the girls in freshly laundered sprigged muslin, and it is to be feared that small attention was paid to the cautions of Miss Smith, who had heard from an old nurse of the young Firebolts, resident in the village, that they were what she designated as 'imps of mischief'.

And so it proved to be. The Viscount Firebolt and the Honourable John, who were of about the same age as Charles and Henry, had no sooner set eyes on them than they challenged them to a bout of fisticuffs; and the Lady Mary, who was dressed in an old cotton frock that would have seemed more suitable to a cottager's child than to the descendant of a hundred earls, or thereabouts, took Clara and Fanny off to inspect her tame rabbits, and then led them to an adjacent farmyard, where they were presently joined by the four boys, and that rough play was set in hand which Mr. Birdikin had so strongly deprecated in urging Miss Smith to see that her young charges comported themselves with propriety during the afternoon's intercourse.

Miss Smith would no doubt have done her best to curb the boisterous propensities of all the children, but the Countess, herself addicted to the pleasures of the chase, and bringing up her children on a different principle from that followed by Mr. and Mrs. Birdikin, said to her, 'Pray leave them to play by themselves. You look as if you want a rest'.

Miss Smith allowed herself to be led into a handsomely furnished and comfortable parlour, where she was bidden by her distinguished hostess to entertain herself with Miss Edgeworth's latest romance, hot from the printers, and to forget all about the children for the next two hours. Her sense of duty was, alas! lulled by the seduction of the book and of the place. On the previous evening Mr. Birdikin had jocularly remarked to her that, if anybody felt inclined to rise early and gather mushrooms, he thought he could relish a dish of them with his breakfast. Miss Smith, anxious to make some return for all the consideration she had received from her employer, had left her bed before six o'clock and gathered the materials for the succulent repast. She had gladly forgone the sleep which her somewhat delicate frame required; but it is perhaps not to be wondered at that her present peaceful surroundings induced a drowsiness to which, after fighting it for a time, she gave way. The book dropped from her hand and she slept.

What was her surprise when she was presently awakened by the entry of none other than Mr. and Mrs. Birdikin, who had decided themselves to drive over and conduct their children home, anticipating before they did so a pleasant hour in the company of the Countess and possibly the Earl, with whom they were anxious to consolidate the excellent relationship already inaugurated. The Earl, however, was abroad with his dogs and his gun in pursuit of the elusive partridge, and his Lady had driven forth in her chariot.

Mrs. Birdikin elected to sit in the house while her husband, followed by Miss Smith, went in search of the children. Mr. Birdikin's brow was dark as he elicited from the instructress an account of the circumstances that had led to her forsaking the duty with which she had been charged, but the constraint he habitually placed upon himself prevented him at the moment from expressing himself upon it, and she followed him in silence, deeply conscious of the weight of his not undeserved displeasure.

The children were not at first to be found, but it was not long before their gleeful shouts were heard coming from the direction of the farmyard, and thither Mr. Birdikin and Miss Smith turned their footsteps.

The scene that met their astonished gaze was such as to cause the cloud upon Mr. Birdikin's brow to deepen. Upon a roughly-made raft in the middle of a pond that adjoined the yard were gathered the Viscount Firebolt and the Lady Mary, with Charles and Fanny. The other three children were bombarding them from the bank with lumps of mud, some of which they caught and returned with as much violence as could be imparted by their immature muscles. As Mr. Birdikin debouched upon the scene of combat from behind a barn, one of the gobbets, launched by the hand of the Viscount Firebolt, made impact with his hat and knocked it off his head.

Though going far beyond the bounds of courtesy, this action might have been excused on account of the rank and youth of the assailant, but it was immediately followed by the discharge of further missiles from all the occupants of the raft, Charles and Fanny having lost all sense of propriety from the example they had all too readily followed, or they would scarcely have ventured thus to attack their own parent.

Nemesis, however, quickly overtook them. A blob of liquid mud thrown by Fanny impinged upon Mr. Birdikin's eye, and when he had regained his vision it was to see the raft overturned and the children immersed in the pond.

The protective instinct of fatherhood overcame in Mr. Birdikin's breast all other considerations. 'Save them! Save them!' he cried; and while Miss Smith obediently waded into the muddy water to render what assistance she could, he stood on the bank a prey to the liveliest alarm.

It was fortunate that the pond was no more than two feet deep, or the outrageous play could only have ended in tragedy. The children waded ashore muddy and dripping, and, although Charles and Fanny were sufficiently sobered by their immersion and the dread of what might be in store for them, the climax seemed to afford the Viscount Firebolt and the Lady Mary the height of amusement.

Mr. Birdikin did not conceive it to be his duty to administer rebuke to the children of others, especially as those others were of a rank superior to his own. He hurried Charles and Fanny back to the Castle in order to beg for a change of clothing for them, and was fortunate enough to find the Countess returned from her drive and in conversation with Mrs. Birdikin. Her Ladyship made light of the occurrence and put the wardrobe of her children at the disposal of the young Birdikins. To Mr. Birdikin's surprise she showed more concern at the bedraggled state of Miss Smith, and herself took the governess upstairs to provide her with the change of habiliments that was necessary, thus forgoing the pleasure she might have gained from further converse with her visitors.

Fortunately for the Birdikin children the Countess begged that no further notice should be taken of their delinquencies, and expressed the hope that they would repeat their visit to the Castle on a future occasion. Mr. Birdikin replied with an invitation to the young Firebolts to come to Byron Grove, for, although he could not wholly approve of their intemperate conduct, such was his breadth of mind and intense loyalty to the hierarchy of Rank that he was able to overlook the disquietudes of the afternoon in consideration of the closer contact they had brought him with his highly-placed neighbours. He thought well, however, on the homeward journey to warn Miss Smith that any further dereliction of duty on her part would lead to instant dismissal.

It was Mrs. Birdikin's exemplary habit to gather her children around her on Sabbath afternoons and impart to them that moral instruction which can best be impressed upon infant minds by maternal influence. A father's instructions were not missing in this happy and united family, and disobedience to them was punished with a strong hand, reinforced by rod, birch, or strap; but it is doubtful whether the more persuasive method of a mother was not as efficacious in implanting the desire to act aright without which correction is of little avail where wills are stubborn and unregenerate natures have still to be purged of moral obliquity.

'I propose for our exercise this afternoon,' said Mrs. Birdikin one Sunday when the children had trooped into the parlour in obedience to her summons, 'that we should follow the advice given to us by our worthy curate in his discourse this morning. Can any child inform me of the point to which I refer? You, Charles, as the eldest, shall speak first.'

But Charles was unable to give a satisfactory reply, and Mrs. Birdikin gently rebuked him for indulging in wandering thoughts, remarking that a clergyman who gave himself the trouble of delivering a discourse of an hour's duration might at least expect some attention on the part of his hearers. 'Come, now, Clara,' she said, 'you, I am sure, will have brought something away with you worthy of engaging our thoughts.'

'To my mind,' replied Clara, 'the most striking utterance that fell from Mr. Guff's lips was his description of the feelings of the prophet Jonah on discovering himself in the whale's belly.'

'The word "belly",' said Mrs. Birdikin, 'though innocuous in the time of the prophet Jonah, is not one that befits the lips of a female child in our more enlightened era. But that was not the passage of Mr. Guff's discourse that I had in mind.'

'Was it not, dear Mama,' inquired Henry, 'that advice of our good curate to contribute of our means with a willing spirit when called upon to do so for a charitable object? I confess that it made such an impression on me that, instead of contributing my usual halfpenny to the collection, I deposited twice that amount in the plate.'

'And you were very careful that we should all see it,' said Fanny. 'I conjecture that the passage to which you refer, Mama, was that in which Mr. Guff advised his hearers not to esteem themselves better than they were. I thought at the time that this was particularly applicable to Henry.'

The old Adam was sufficiently strong in Henry to cause him to give a tweak to Fanny's hair, in reply to which she put out her tongue at him. But these exchanges were unnoticed by Mrs. Birdikin, who said, 'It was the passage following that advice which I had in mind. You will remember perhaps that Mr. Guff said it would be well if we were all to confess to others such misconduct as our consciences might from time to time reproach us with. I propose, therefore, that we shall all in turn search our memories for such lapses and bring them to light'.

The children appeared to be turning this suggestion over in their minds, and Fanny inquired, 'Will any misconduct of which we make confession be brought to the notice of our Papa?'

Mrs. Birdikin reassured her on this point, and Charles said brightly, 'Thank you, dear Mama, for devising so excellent a pastime for a wet Sunday afternoon. I have my own transgression ready, but you must take the lead by recounting one of yours'.

It is doubtful whether Mrs. Birdikin had had it in mind to make confession of any lapse from right conduct on her own part, but she made haste to reply, 'The faults of childhood, if not repented of at the time, are apt to rise up in judgment against the transgressor when he or she attains maturity. It is because I wish to spare you the pangs of outraged conscience in after life that I will make known to you a misdeed your mother committed in her early youth which has ever weighed upon her and would be well-nigh insupportable if a lifetime of right conduct had not withdrawn its sting.

'You must know, then, that when a young child not yet fully awakened to the sacred rights of Property, a regrettable vanity caused me to abstract from my Mama's dressing-table a brooch of considerable value and to pin it on to my frock in the seclusion of my bedchamber. When the brooch was missed I grew frightened and concealed it under a cauliflower in the kitchen-garden. My excuse must be that I knew that it would be discovered there when the gardener cut the vegetables. And so it was, but, alas! the gardener's dishonesty was such that, on finding the trinket, he sold it and retained the proceeds. The crime was eventually brought home to him and the brooch recovered; but you may picture the agony of mind I went through before this happy issue was brought about. Nobody would believe the gardener's story that he had found the brooch under a cauliflower, but until he was safely lodged in jail I hardly knew a happy moment. Let this recital be a lesson to you, children, never to depart so much as a hairbreadth from the paths of rectitude, and, if you are led astray, to make instant confession. Had I done so in this instance I might, nay, probably should, have been punished, but should have escaped such pangs of remorse as even now make me shudder to look back upon.'

'Your confession, dear Mama,' said Charles, 'encourages me to substitute a similar experience of my own for that which I had it in mind to acknowledge. Two days ago I abstracted from my Papa's table a box of lucifer matches, the half of which I have amused myself with striking. It had not occurred to me to hide the box under a cauliflower, and I shall now be glad to hand it to you and thus escape the distress of mind, and possibly of body, which you have so feelingly described.'

'The confession I have to make,' said Clara, 'is that when my Papa summoned us to attend him yesterday for examination in our course of study I was employed in cutting out paper roses, and so far forgot myself as to exclaim, "Oh, bother!"'

'My fault, I fear,' said Henry, 'was a graver one. Two days ago I espied among the letters on the hall-table one addressed in the handwriting of our governess to her aunt, Mrs. Clott, and, knowing that my Papa has forbidden her to involve us in further communication with the wife of an ironmonger, I wished to assure myself that his instructions had been obeyed. I broke the seal of the letter, and, finding that it was free from offence in that respect, though I regret to say that Miss Smith made some complaint of the coldness of her bedchamber, I took wax and sealed up the missive again.'

'Then you are a dirty little sneak and tell-tale-tit,' broke in Fanny, 'and when I grow up I shall not acknowledge you as my brother!'

'Hush, hush, Fanny!' said Mrs. Birdikin. 'The fault to which Henry has confessed was a grave one, for it is not permitted to tamper with the correspondence of others however lowly their position. But his desire to satisfy himself that his father's wishes were carried out was not wholly reprehensible, and he has now confessed his fault. Instead of sitting in judgment on him do you confess one of your own, and let us judge which is most to blame.'

Thus adjured, Fanny collected herself and said, 'I caught a hedgehog yesterday just before my Papa called us in to him, and put it under a flower-pot, intending to transfer it later on to Henry's bed. But when I went out again the flower-pot was overturned and the hedgehog had escaped'.

'There,' said Mrs. Birdikin, 'you have an instance of an intended sin prevented by an interposition of Providence. Would that all faults were thus made impossible of achievement!'

'But I didn't want to be prevented,' said Fanny. 'I shall try to find another hedgehog to-morrow.'

'In that case,' said Mrs. Birdikin, 'you will be suitably punished by your father.'

'Now that we have all made our confession,' said Charles, 'I propose that our dear Mama shall pronounce upon the best one. I should be inclined myself to give the palm to her own confession of a fault which involved the punishment of another.'

'Indeed, Charles,' said Mrs. Birdikin with some indignation, 'it ill becomes you to sit thus in judgment upon your mother, who has long since repented of what was after all no very serious fault in a child not yet of an age to estimate the seriousness of all faults. No further notice will be taken of the far more serious delinquencies to which you have all confessed on this occasion, but look well to it that you mend your ways or trouble will ensue.'

This ended the afternoon's instruction, but Mrs. Birdikin did not again invite her children to a confession of faults for which she had promised absolution beforehand, judging it better that they should be discovered and dealt with in the usual way.

One morning as the Birdikin family was seated at the breakfast-table, the footman, John, who was usually as deft as he was willing in the performance of his duties, earned more than one rebuke from his master for his awkward handling of the implements of his service. At last, when he had dropped and broken a valuable porcelain tea-cup, Mr. Birdikin could no longer restrain his anger and ordered him from the room, saying that he preferred to be waited upon by his children rather than submit any longer to the ministrations of an oaf.

'I observed, dear Papa,' said Clara, the little Peacemaker, when the footman had left the room in a burst of tears, 'that John's face was pale and his hands trembled as he supplied us with our viands, and I cannot forbear the impression that some serious stroke of misfortune has befallen him.'

'I know what it is,' said Fanny. 'His mother was brought to bed two days ago and yesterday his father fell from a tree and broke his thigh.'

'Let us repair at the earliest possible opportunity,' said Mrs. Birdikin, 'to the abode of these poor people and take with us such succour as our sense of benevolence may dictate. I apprehend, Mr. Birdikin, that John's not unnatural solicitude on behalf of his parents may on this occasion excuse him for his departure from the conduct that you rightly expect from him.'

'Indeed,' said Mr. Birdikin with a courteous inclination of the head towards his helpmate, 'I would not for a moment impugn the promptings of a heart so full of benignity as that of Mrs. Birdikin. John's offence shall be wiped out by a deduction from his wages of the value of the vessel he has destroyed. Let us consider the form which our charitable contribution to the needs of these unfortunate people is to take. You, I know, will supply from larder and pantry what will support the coarse fare suitable to the station of cottagers when in health. I will contribute the bottle of port wine with which I should have regaled myself yesterday evening had I not found it a trifle corked. Though rendering it unsuitable to my palate, the slight disqualification will hardly be noticed by theirs.'

'I would recommend,' said Henry, 'that there should be included in our charitable grant a bundle of assorted tracts, for, while the nourishment of the body must not be neglected, are we not taught that it is of still more consequence that those in a position of superiority should concern themselves with the souls of those who owe them deference?'

This unworldly spirit, shown so early by one destined for the duties and rewards of the clerical profession, could not but bring gratification to Henry's parents. But Fanny, who had not yet undergone that conversion from the promptings of her lower nature which in her brother's case was already bringing forth such pious fruit, remarked, 'Would it not afford more entertainment to the sufferers if Henry were to read to them from the adventures of Spring-Heel Jack, with which he was regaling himself in the wood-shed yesterday?'

Henry made haste to explain that he had found the publication mentioned in a drawer in John's pantry, and had wished to assure himself that it was fit for perusal by the footman; and Fanny was rebuked by her father for her censorious reference to her brother's well-intentioned action.

Mr. Birdikin himself interrogated the footman upon the details of the accident that had befallen his father, and did not rebuke him when a further gush of tears testified to his gratitude for the benevolence so abundantly shown by his strict but humane employer.

John's family occupied a cottage on the estate of Captain Rouseabout, in whose service the father was employed as woodman. Mr. Birdikin's low opinion of this gentleman, for such he was by birth, if not by conduct, caused him to express a doubt whether the poor labourer's misfortune might not bring upon him dismissal from his occupation. 'A man of the reprehensible habits of our neighbour,' he said as he walked towards the woodman's cottage with his wife and family, John the footman following them at a respectful distance with the laden basket, 'is usually devoid of all bowels of compassion. It would not surprise me to learn that this man, who has suffered disablement in his master's service, has already received notice to quit his cottage.'

'In that case, dear Papa,' said Clara, 'can you not provide him with one until he is able to resume his employment, and take him into your own service?'

'That, I fear, is impossible,' said Mr. Birdikin. 'Nor would it be altogether desirable. Our humane laws provide food and shelter for those of the lower orders who through no fault of their own have lost their employment, and it would not be well to tamper with their working. As long, however, as this family is allowed by Captain Rouseabout to remain in their present situation I shall make it my duty to show him that there are those who are eager to fly to the relief of distress, and thus bring shame, if he is capable of such a feeling, upon one who is ever ready to scoff and jeer at all tokens of high-minded conduct.'

The walk of over a mile seemed short to the little party intent upon their charitable object, and ere long the woodman's lowly cot came into view. A family of young children were playing in the neatly-kept garden, and an older girl appeared at the doorway as Mr. Birdikin stepped up the path and respectfully bade him and his lady enter, if it should be their will to do so.

'My will,' said Mr. Birdikin, 'is ever to show that benevolence towards the deserving poor which is too often, alas! met with ingratitude. I trust it will not be so in this case. You, children, will remain outside, for such abodes as this are apt to be the breeding-ground of contagious disease, perilous to those delicately nurtured. Damsel, lead on!'

Mr. and Mrs. Birdikin entered the cottage, followed by John with the basket. The four children of the woodman stared at the young Birdikins as if they had been visitants from heaven, as indeed they might well have been, coming as they did on such an errand of mercy.

'Come,' said Charles, 'let us engage in a game of tag or hide-and-seek, and see whose legs are fleetest.'

'Might not Henry prefer to take advantage of the situation to impart some moral instruction to these children?' asked Fanny. But Henry himself elected to play at hide-and-seek. Sides were formed and the air soon rang with the gleeful shouts of the children, those of the woodman quickly losing their awe of the gentility of their playmates.

Ten minutes or so had passed in the merry sport when Fanny, who had been hiding behind a hedge, leaped from the bank into a grassy ride and narrowly escaped being trampled underfoot by a horse, the approach of which she had not noticed. The horse was bestridden by a gentleman, who quickly reined it up and said, 'Halloa, my pretty little dear, do you want your brains dashed out?' Without further ado he bent down and, seizing the frightened child, set her in front of him on the saddle, at the same time printing a resounding kiss on her infantile cheek.

What was Fanny's surprise, when she had so far recovered from her fright as to steal a look at the somewhat rubicund and weather-beaten face of her rescuer, to find that it was none other than that of Captain Rouseabout, whom she had been taught to regard as in league with the Evil One. But there are few, however debased, whose better natures are not touched by the innocence of childhood. Upon hearing from Fanny of her parentage and what had brought her hither, Captain Rouseabout emitted a rude guffaw, but made no further comment. On reaching the gate of the cottage, to which he tied his horse, after dismounting and lifting Fanny from the saddle, he presented her with a bright sixpence, accompanying the gift with the whispered remark, 'Not for the missionaries', and another burst of uncouth laughter. Then he gave a loud 'View-halloo!' and entered the cottage.

Fanny informed her brothers and sisters of the identity of the new visitor, and the children lingered in the garden until their father and mother emerged from the cottage and the steps of all were turned homeward.

There was a cloud upon Mr. Birdikin's brow as the walk was commenced, and he kept silence until Mrs. Birdikin said, 'I am glad at least that these poor people are to be relieved from want until the breadwinner can again pursue his avocation'.

Mr. Birdikin's brow cleared. 'But for our errand of mercy,' he said, 'it is doubtful whether one so lost to all sense of propriety as Captain Rouseabout would have exercised the clemency which has now been shamed from him. His barefaced request to me to trust him to look after his own people was a mere covering-up of his indebtedness to my example only to be expected from such a man. Let us remove him from our thoughts.'

'I think,' said Fanny, 'that Captain Rouseabout is the most agreeable gentleman I have ever met, and when I grow up I shall marry him.'