| chap. | page | |

| I. | REDMERE | 9 |

| II. | PAUL AND NEST | 14 |

| III. | JOHNNIE MORELAND | 18 |

| IV. | JOHNNIE'S BUSINESS | 24 |

| V. | HOPE DEFERRED | 33 |

| VI. | CHRISTMAS TIME | 44 |

| VII. | THE SEARCH | 48 |

| DICK CAVE, THE RAGGED SCHOOL BOY | 55 |

The little town of Redmere lay slumbering under a July sun. The trees were decked in their green, and gooseberries and currants tinted the gardens with amber and crimson. The roses were in full flower, and the streets were dusty under a blue sky; but the meadows were cool and fresh, and white with the summer snow of daisies. Redmere could boast of its old ivy-covered church, with its rector's house next to the squire's, only separated from it by the great beech hedge. It had its old inn, too, with the horse-block in the yard, where the idle lads of the town gathered in to chat with the[10] stable-boys, or the men lounged while they smoked their pipes. The inn was called the Boar's Head, leading men's minds back to the days when the cultivated land was a forest, and kings loved to chase the boar amidst its wilderness of oaks and beeches. The Boar's Head inn was the haunt of the men of rod and fly, for near it a river, the delight of anglers, flowed along amongst the daisied meadows. It was also the haunt of artists, for that same river had its little breaks and sylvan nooks, its rustic styles, and mossy banks, that the painter loves. Then there were such lovely wild flowers,—orange coltsfoot, and white ranunculus, and straw-coloured willow leaves drooping into the water. The lovely spots around Redmere for the artist's brush were innumerable; and so it happened that, one fine afternoon, two young men arrived at the Boar's Head with easel and brushes, ready to begin work on the morrow.

These young men were great friends, and they delighted in each other's workmanship. Paul Staunton, the elder of the two, loved to paint portraits, and his friend, Hector Palmer, loved rustic bowers, where the green leaves covered the half-rotten framework with their[11] verdure, or the spot in the meadows where the daisies were broken by patches of yellow butter-cup, crow's-foot, lady's fender, and vetch, and by the crimson clover flowers, or the rusty red of sorrel.

The only family in Redmere that one of the artists knew about was the squire's, his mother being a far-away cousin of the squire's wife. Mrs. Cambridge received her cousin's son cordially; he entered with this introduction: "I am Paul Staunton, and this is my friend, Hector Palmer, son of the gallant Captain Palmer. We are artists on a tour for sketches and commissions."

And so the influential families round Redmere, following the squire's example, showed the two young men no lack of hospitality though the commissions were not so numerous.

The friends were quite different in disposition and manners, as friends usually are; but it is only with Paul Staunton we have to do, for Hector Palmer, being soon called away, passes from our story; while Paul remained behind to finish some sketches he had begun.

Paul was a strange mixture of gentleness and stubbornness, shyness and confidence, scorn and[12] candour. While claiming little from others, he exacted a great deal from himself. Besides, he had an unhesitating faith in his own powers.

The family of the squire consisted of the father, a bluff fox-hunting man, and his energetic wife, who managed every one, even her husband, who trusted her completely; three sons and three daughters, and an orphan niece, a daughter of the squire's brother. Nest Barnet, the squire's niece, seemed a good deal out of place in the family, yet she was so silent and unobtrusive, that no one could really feel her in the way. Her cousins were gay, dashing girls; handsome and bold, they could follow their brothers to the hunt, and leap two-barred gates, and it was said they could hold a gun with any of their brother's companions. Nest, with her broad brow, large eyes, and delicate, girlish mouth and chin, had little in common with that household. She had her flower-painting card boxes, worsted balls, egg-shell baskets, and books, the last greedily devoured. She could not assist her aunt, for Mrs. Cambridge's plans were perfect, and she declined interference with her daily rounds. As little could she help her uncle, though he often drew her to him and patted her soft cheek,[13] and this slight attention, more than she received from any other of the family, drew her heart out to him beyond all others; besides, she fancied often she could see a likeness to her father, his younger brother, who had died so early, leaving her well nigh penniless.

Such was the family to which Paul Staunton, claiming kindred with its mistress, introduced himself and friend that fine summer day.

Strange, and yet we can hardly call it strange, that the only one in all that household to whom Paul Staunton was drawn, was the penniless orphan niece, Nest Barnet; but perhaps the reason was that Mrs. Cambridge, seeing Nest had really a taste for painting, had put her, along with her daughters, into Paul's hands, to be instructed in colours. Her cousins, after a few efforts, gave up in disgust; but Nest, with her usual steady perseverance, stuck to her easel and encouraged her teacher.

Paul Staunton, the most backward lad in society, was free with Nest; and she, with her delicate eye, and the sweetest natural fondness for this simple, common, beautiful world, believed most firmly in her teacher, who was patient and indulgent. Soon Paul was her saint and hero, and she was quite ready to be absorbed in him. It was a characteristic of Paul that the commonest text sufficed him. He carried his treasures within himself, and only the slightest touch from the outside world could draw them out. He would stand and contemplate a piece of moss until every leaf had a tale to tell, and he filled his pockets with what the poorest country lad thought the veriest weed.[15]

Mrs. Cambridge had made enquiries about Paul Staunton, and found that the young man had no prospects save his profession, and therefore could be no match for any of her daughters, and so she did not discourage the intimacy she saw springing up between her orphan niece and the young artist—an intimacy of which, perhaps, they were not themselves aware, but which was no doubt ripening into something truer than friendship, when the time would come to call out the knowledge of it to both their hearts.

And time wore on—as it wears on with all of us through joy or sorrow, absence or presence—with glad fulness, or with bitter achings of heart; and the sunshine left the hills, and the leaves and flowers the woods, but still Paul Staunton lingered at Redmere, and yet he was not idle, he had other pupils besides Nest, and he had got a few commissions which kept him in the neighbourhood. He had never mentioned love to Nest, yet he was getting more and more interested in her, and had he reasoned the matter, he would perhaps never have spoken of what was in his heart. How could he, who could scarcely make a clear subsistence for himself, attach himself to a penniless girl? At last[16] spring came, and though Redmere was beautiful in its glad time, Paul felt he must now leave it. He entered the house one day, and there was a sadness on his brow which Nest saw at a glance.

"I must leave Redmere to-morrow," he said, quietly; "my work is done, Nest, and duty bids me go."

Paul was going, and there was no talk of his return, and Nest's hands trembled as she helped him to put up his pictures.

"I shall miss you, Nest," he said, humbly, "when we are parted."

Nest's breast heaved, her eyes filled with tears, and she managed to say, "Will you ever come back, Paul?"

"I cannot come back," he murmured, sadly, "I am poor, and it may be years before I could offer you a home, Nest." That was all he said of the great love of his heart, and Nest understood him. This was no time for coquetry.

"Could I not help you, Paul?" she said, simply; "I am of no use here, I might help you."

"Do you think so?" he said, his face flushing with pleasure: "Then, Nest, we need not part."

And that was all they said; and Paul felt[17] that Nest was the one, the very one, he would need beside him in his journey through life.

And Nest was content, as she sat, with sweet calm brow, a picture such as it does any man good to gaze upon from his table foot, and know that it is his wife, the mistress of his household, in whom her husband's heart may safely trust for ever. Everything now seemed beautiful to Nest, for the beauty began in her own heart. She was not greatly troubled that she had no grand preparations, and that there were no preliminaries to be attended to, and no lawyers drawing our marriage-contracts before the irrevocable step was taken, and though the aunt and cousins were supremely indifferent; and the servants confided to each other that a bride should be rather crying than laughing, for a crying bride was a happy one. But no one told Nest—she had none to remind her of the tender meaning of the wise old proverb, no one to warn her of the realities of life, so much holier and purer than any mere illusion; and so she sang as she stitched a few things, and dreamt dreams of a long and happy future.

At the door of an old tumble-down-looking tenement in the East End of London, one Sabbath evening, two children sat, a boy and a girl, apparently about the ages of nine and six. The boy was lame, and his crutch lay within reach of his arm; the girl was sickly-looking and scantily clothed, though the evening was chill and damp. There was nothing but misery in sight; wretched men and women gathered in small groups of twos and threes, and bare-footed, bare-headed children quarrelled and fought in out-of-the-way corners; while the two little ones seemed to shrink away from the noise and confusion around, probably their delicate health precluding them from the sports of their more robust companions. Just then a young man entered the square, and tried in vain to attract the attention of the boys busy at play,[19] who either answered him rudely or with derisive laughter, when, turning round, he caught sight of the two solitary children, and going up to them, said kindly,

"What are your names, little ones, and why do you sit there alone?"

"Please sir," said the boy, touching his tattered cap, "They calls me Johnnie Moreland, and this is my little sister Anne; we don't play with the others, 'cause you see I be lame, and Anne likes best to stay with me."

"Will you come with me, Johnnie and Anne," then asked the gentleman, gently, "and I will teach you stories, and you will hear pretty hymns sung?"

"But we 'aint got no hedication," said the boy, "and we don't know nothink."

"I will teach you, though," was the answer.

"Let's go then, Anne," said the boy, starting up, but Anne held back, shy and afraid.

"She be'nt no way used to company," said the boy, making apologies for her; then, putting his arm round her waist, he said, persuasively, "Come, Anne, with the gentleman, that's a good girl."

"Yes, come," echoed their new friend, "and I[20] will teach you to sing hymns too, and you will know about Jesus, and He will take care of you, my poor children."

"Please sir," asked Johnnie, "who is Jesus? wot is to take care of us? Is He very rich, and does He live in one of them big 'ouses I pass every day when I goes to market?"

"You shall hear all about him, Johnnie, when you come to school," was the answer, "and now we are close to it."

Just then they reached a quiet-looking little mission-house, where the hum of voices might be heard through the closed doors, which the gentleman softly opened and entered, followed by the two children. Johnnie's jacket was thin and worn, and his trousers were ragged about the ancles, while Anne wore only an old tippet and tattered frock, fastened together with broken strings. For the first time the children felt ashamed of their scanty clothing, seeing that, though the boys and girls around them were poor, they were clean and comparatively tidy; but they soon forgot the discomfort of the situation, listening to the new and strange words which they heard. Johnnie, especially, was shrewd and intelligent: the life he led had[21] sharpened his wits, and given him wisdom beyond his years.

It was not their friend, but a clergyman, who addressed the meeting, and very kindly did he speak, asking questions every now and then, to see if the children followed him. As they had been promised, he told them of the Lord Jesus Christ, who came down from heaven to save a lost world, and who said, "Suffer little children to come unto me, and forbid them not," and of His good Spirit He would send to help them to be good, and to teach them to ask Him for what they needed. Strange words these were to Johnnie and Anne, and not much of them could they understand. Nevertheless, they liked to hear them, and they liked the hymns that were sung, so the time passed only too quickly. As they were leaving, the gentleman spoke to them, and told them to come back next Sabbath, adding, "And until then, Johnnie, don't forget to pray to the Lord Jesus to take care of you, He will hear you from heaven. Will you promise me to do so, both of you?" To which they answered, "Yes," resolving to do as they were told by the kind gentleman, though scarcely knowing how.[22]

It was now dark, and the children sped homewards without speaking, and climbing to the top floor of the old house from the door of which the gentleman had lured them, they turned into a small room. A farthing candle burned on the table, beside a bed on which lay a woman, who spoke in querulous accents to the children as they entered, and asked them where they had been so late, adding, "There's no getting ye up, Johnnie, in them mornings, when ye don't go to bed early."

"Oh! mother," they both exclaimed, "we've been and heard such beautiful words." "And you can't think how happy they made us," added Johnnie.

"Well, I am glad you've been made happy," she answered wearily, "though, it seems to me long before words makes poor folks happy."

"But we've heard about a great King, who is rich and good, and will be kind to us, and He loves children."

"I hope it may be true then," she exclaimed; "for my part, I've never heard of no king who cares aught for we poor people."

"Well, but we must pray to him, the gentleman said," argued Johnnie, adding, "Come, Anne,[23] we'll do it, for we promised;" and though Anne was very sleepy, they both knelt down and said: "Great King Lord Jesus, send us good Spirit to help us;" and after this they felt happier than they had ever done before, and, slipping into bed, were soon fast asleep.

You may be sure Johnnie and Anne Moreland were regular attendants at the mission-school, and the kind teacher felt encouraged by their earnestness and attention.

They had now learned much about the Lord Jesus and His good Spirit; and the troubles of life, the hunger and the weariness, seemed more easily borne when they knew there was an eye that watched them, and a Friend in heaven who loved them. Their mother did not concern herself much about them; but she tried to make them clean and tidy before they went to school, for she felt that since they attended it, they had become more obedient children, and the hymns they sang to their little brother Dick always[25] quieted him when cross, so she rather encouraged them than otherwise in their love of instruction.

Mrs. Moreland was a widow who sometimes got employment charring, at other times selling apples or oranges on the street. She was a strong-built, hard-featured woman; though not by any means devoid of natural affection. Yet, alas! a large part of her earnings found their way to the gin shop round the corner; and thus Johnnie, weak and delicate though he was, besides being lame, had to give his assistance to maintain the household, and, but for this assistance, Dick and Anne would often have gone days without food. Compared with other families around them, the Morelands were pretty comfortable, and compared with other mothers, Mrs. Moreland was not, upon the whole, a bad one; and now, almost imperceptibly, the good influence of her children was telling upon her own life and character. She was going seldomer to the beer shop, and her temper in consequence was improving; besides, she was getting more industrious and taking better care of her money. Still it needed all Johnnie's help to keep the pot boiling; but, by the wondrous power of love, and the help of the Lord Jesus, whose aid he now[26] sought daily, he was kept from sinking beneath the burden laid upon his young shoulders.

It was in May when Johnnie and Anne first attended their mission-school, and now the bright summer time is past, and autumn too is nearly at a close. They know it by the cold, shortening days; for in the heart of a great city the poor know little of the beauties of the budding spring, the rich luxuriance of summer, or the fading glories of the dying year: it is only by the lengthening or shortening days that they mark the seasons as they pass.

"Get up Johnnie, or the market will be over before you get there," exclaimed Mrs Moreland, one cold October morning, as she bent over her boy, who slept, on his hard shake-down, the calm untroubled sleep of childhood.

"Oh! it surely ain't time yet, mother?" was the answer of the poor little fellow, rubbing his eyes the while to keep himself awake.

"Why, bless you! yes," said the woman; "it must be nigh on five, and if you miss the chance of cresses this morning we must go without our breakfast, as there ain't no bread in the 'ouse."

"Oh, dear!" cried Johnnie, getting slowly out of bed, "it is so dark and chill in the streets,[27] and scarce none will buy my cresses now, they say they make them shiver so."

"We must try and do something, though, to keep body and soul together," said his mother, adding, as Johnnie was coughing violently, "but see that ye put on Dick's comforter, and now when I bethink me, there's a crust hof bread on the table,—take it lad, it will 'elp you along this cold morning."

Johnnie by this time was up, and pulling on his thin garments by the light of the lamp in the court without. Before leaving, he knelt down, and after thanking God for His kind care of him throughout the darkness of the night, he asked Him to bless his mother, brother, and sister, and make himself a good boy, ending with the words which closed his every petition, "for the sake of Him who died to save sich poor sinners as we be," and then flung the basket over his shoulder, and walked forth briskly into the darkness.

One holiday, the only one in his busy life Johnnie had had, when the kind teacher took his little scholars down into the country, and the remembrance of this day helped to cheer him as he trudged along. He thought of the[28] hedgerows he then saw, where the blackberry bunches hung, and the dog-roses bloomed amidst blue straggling vetch and clinging convolvulus, or the many-tubed honeysuckle wafted its fragrance on the breeze. He recalled the picture of the quiet homesteads, with their ponds over-hung by alder-trees, and their little gardens crowded with a medley of old-fashioned flowers; the farmyards, where dogs barked in the sunshine, and cocks crew from raised haystacks. How snug beside them looked the labourer's cottages, either clustered into hamlets, or standing singly, with their backs to the highway, seeming to turn away from everything but their own spot of earth and sky; and the cheerful villages too, with their old grey churches, and neat parsonages; the small shop, in whose bow-windows might be seen sundry wares; and the never-failing "Cross Keys" or "Hunter's Rest," furnished with its wooden horse-block, where two or three men might always be seen lounging and smoking their long pipes.

Though he knew not the names of the flowers he saw in the trim gardens, or those he plucked by the wayside, or on the sunny banks, for his knowledge, as far as this world was concerned, [29]was limited to the buying and selling of water-cresses, his stock-in-trade; yet he had learned at the Sabbath school about God and Christ, and therefore, when he wandered through the depths of that glorious forest, he could look around on everything he saw, and say like the poet, "My Father made them all." How sweet, then, was the song of the lark, or the notes of the robin in the bush—that robin sacred even to mischievous bird hunting boys, because of the pretty tale of the "Babes in the Wood," as well as for the pleasing superstition which has allotted to him the special protection of heaven, insomuch as it is thought that "those who harry their nests will never thrive again."

So, to ears that had never heard aught of these songs, save the twitter of the house-sparrow, or the lay of the imprisoned lark in some cage at a bird-catcher's door, this forest music was never to be forgotten. It was well that Johnnie had some pleasant remembrance to make his path bright this dull morning.

As he went along, the blinds drawn down over the windows of the houses showed that life in the great city, with very few exceptions, still slept. Here and there a milk-woman, earliest of[30] her class, passed him by; or, it might be a policeman, who, at the approach of footsteps, turned full upon the small pale face his bull's-eye lantern, but quickly withdrew it again, reading there no harm to the community over which he kept watch.

As he proceeded on his way, daylight began to dawn, and, from the doors of small houses, tradesmen and labourers began to issue forth, to commence their daily toil, and, ere he had reached Farringdon Market, the din of voices was heard mingling with the sound of vehicles which brought the goods from the neighbouring country.

To an inexperienced child, the dim light and confusion would have been terrifying and distracting; but Johnnie was too much accustomed to it to have any fear. Coolly he wended his way to the stall of the kind Irishwoman, past the waggoners with smock-frocks, carrying the baskets brought from distant gardens to their different customers—past the barrows full of carrots and turnips which some old tattered-looking men were wheeling to their stall—and past the crowd of eager purchasers already assembled around their favourite merchant.[31]

By the light of the flickering candle placed upon the lid of the hamper, Johnnie selected his fresh water-cresses, receiving from his old friend a bunch or two into the bargain, who said, as she wrapped her arms in her apron, "God help the poor childer this could morning, and God help that little one, he don't seem fit anyhow for sic a life," muttering to herself, "They 'aint got no chance, them young things. Well, well, there is a heaven above, and surely One there takes heed to them poor infants."

Johnnie, having got his supply, threaded his way, as swiftly as his lameness would permit him, out of the market, and soon might be heard his "Fresh water-cresses, oh!" mingling with, "Potatoes, sprats, periwinkles, wink, wink, cats' meat, old clo," and the common street cries.

As he went along on his way, shops began to be opened, and his cry attracted customers. The general grocer hurries from over his counter to secure a few bunches to place in the window beside candles, soap, cheese, fish, etc.; and the broker, over whose door hangs the three golden balls, proclaiming to the poor a speedy and convenient road to ruin, steps out of his wide shop-front to buy some for breakfast,[32] which his buxom wife, with gilt ear-rings and brooch, has been preparing in the little room leading from the shop. Now and then a labourer stops at the familiar cry and purchases from his store, giving him, it may be, a halfpenny over and above, or a smart tablemaid calls him to the door of a better-class house, and drops a coin into his hand in return for the fresh bunch of his cresses for "Missis' breakfast." And in this way, long ere the morning is gone, Johnnie returns homeward with a pretty good supply of coppers. His poor little feet are blue with cold, and his hands well-nigh powerless, still the discomforts of his lot are nearly forgotten, as he thinks how this money will enable him to provide a breakfast for his household.

The family room of a poor artist in St. Martin's Lane, London—we can fancy it. Traces of gentle birth and breeding may be seen. Casts, prints, and portfolios, with scant furniture, such as might only have belonged to a tradesman or better sort of mechanic, and all not in absolute disorder, they were too busy for that, but colours, canvas, and pottery, all huddled together, without any wish for effect.

The artist himself, half a dreamer, half a drudge, lapsing into absorbing trances and again returning from dreamland to this everyday world to find everything going wrong and threatening nearly to make his wife and child victims; feeling at times nearly crazed, and yet[34] he had worked and starved till his face grew thin and sunken, and his eye strained.

The world keeps saying that a man may prosper if he will, and it points to the successful men in triumph as examples, as a Sir Joshua Reynolds or a Vandyke, of those who knew their business and could do it. But the race is not always to the swift nor the battle to the strong; and though Paul Staunton could do his work well, he lacked a something which took with the multitude. And what of his gentle, patient wife, who had married him, believing thoroughly in her husband, and did so still, loving and honouring him so much that it almost drove her frantic to see him suffer? Had she been a wiser woman, or had been more worldly, she would have hesitated before she cast in her lot with a penniless artist, even though he was acknowledged a genius. But Nest Barnet was chosen by the poor artist. The squire's family, at Redmere, rather encouraged than discouraged the match; though the squire himself, to do him justice, was not clear about the wisdom of the step. His wife, however, ruled him in this, as in other matters, and so he gave up the point to her superior judgment. Then Nest and Paul were[35] like two children, eager to have the business over; and so, on a grey October morning, with the autumn sunbeams faintly brightening the yellowing vine over the sexton's house, and the orange and grey lichens ornamenting the church with its heavy Saxon arches, these two were made man and wife, amidst the congratulations of their friends, and set off together on the voyage of life, for their city home, Paul's lodgings in London, on the strength of £50 in hand and future orders. Oh! these old simple beginnings, they deserved to have sunshine in their path, if only for their firmness and faith.

All Nest's friends were not so easy about the match, however. She had an old uncle in the great city whither she was bound, who stormed and raged; but he had scarcely noticed his sister's child, so she had not thought he would care whom she married, and had not consulted him and did not much care now about his anger.

It is more than two years since that knot was tied, and Paul and Nest have been combating flesh and blood woes among the bricks and mortar of London. These years had not been sunshiny ones. Paul had striven and worked, but all in vain. His paintings would not sell,[36] he tried every kind of imaginable sketch in flower and figure; he was not proud, he would do much for Nest and his little son, much, but not truckle to the world's low taste for commonplace. To Nest it had been a seen evil, and she had looked into the gulf, but missed the depths in her youthful boldness and faith. She had never lost her faith in her Paul, she could have borne anything for her husband, and she worked marvels for him. She learned to engrave, drew and painted, from old, fresh memories, articles of stone-ware for the potteries. She was clothed in the cheapest and most lasting of printed linen gowns and aprons, and fed herself and child on miraculously small morsels; but her face had lost its roundness, and had got sharp and worn, since the day she stood beside her lover in the old church of Redmere. Still she had never lost her sweetness of nature, and could not be pinched into meanness, or be brought to part with her love, charity, and patience.

It was a cold morning, when Paul came into his room, which Nest had made as comfortable as she well could for her husband's breakfast. True, there was the litter of brushes and colours, and wild pictures, but a fire burned in the grate;[37] and on the table, though the food was frugal, it was not uninviting. Some letters were lying, which the postman had just brought in, and before Paul tasted his food, he hastily opened them and began to read. Nest came behind him, and gently laid her hand on his head, for she saw he was getting agitated by the contents. "It's the old thing, Nest," he said, "nothing but disappointment: the rich man has returned the picture, I see nothing but the workhouse for us, little wife."

"Do you not remember, Paul," answered his wife, cheerfully, "that when the night is darkest, the day is breaking? Never fear, my husband will get on yet, and I will see my Paul acknowledged by all as a great artist."

Paul looked up in her face and said, bitterly, "I wish I had never seen you, Nest, and then you would have been happy; I could have borne sorrow and pain alone, but that you and our child must suffer, maddens me. I wish I had left you in your country home."

"Paul, Paul!" cried his loving wife, "why do you say such horrible things, 'wish you had never seen me,' 'wish you had left me behind,' when you went to battle with the world? How[38] little you know the heart of a wife. I would rather be with you, my husband, poor and tried as we are, than living in a palace. Have faith in God, Paul, and all things will come right again."

But Paul heard not the cheering words, for his brain seemed on fire, and he lifted his hat from the table, and rushed into the street, leaving his breakfast untasted. He knew not why he fled, or why he sought the open air, and he knew not where he was, until he found himself suddenly on the banks of the Thames. For the first time the wish crossed his mind, as he looked on its waters, rolling on to the ocean, to plunge into them and be at rest, forgetful of the grief he would have caused the heart of his poor wife.

As Paul stood and looked, fascinated by the river calling him, as he almost fancied, to seek by it to get rid of his troubles, Johnnie Moreland passed along with his basket, muttering to himself, as he counted his money, "Good luck to-day, one and fivepence for mother." Then, his eye catching sight of the water, it at once recalled to his mind the verse of Scripture he had been taught a few days before in the Sabbath school, and he said, half-aloud, just as he came in front of Mr. Staunton, and quite unconscious that his[39] words were heard, "There is a river, the streams whereof maketh glad the city of our God."

Though it was scarcely more than a whisper, Mr. Staunton caught the sound, and over his mind rushed the memories of a quiet home and of an aged grandmother who had well supplied the place of mother to the orphan boy, and of texts of Scripture that boy used to repeat every evening by her knee, when he went to bed with the birds, and the remembrance of these things overpowered the careworn, desperate man. He leant against the bridge for a few seconds, before he could recover himself from the whirl of mind which these words had caused.

Johnnie, all unconscious, went on his way chucking his money, and saying again, "One and fivepence this morning already, well, Dick and Anne won't go without breakfast, nohow."

When Mr. Staunton was in some measure restored to a calmer frame, he turned and looked after the retreating figure of the boy limping slowly along, then, taking a few rapid steps, he soon overtook him, and said hurriedly,

"Child, who taught you that verse of Scripture you have just repeated?"

At first Johnnie did not speak, for he had[40] hardly known to what Mr. Staunton alluded, and so troubled and perplexed was the face that bent over him, that the boy seemed lost in astonishment at the voice and appearance of the stranger; but at last finding words, he stammered, "Was it about the stream that makes glad the city of our God? Teacher at Sunday-school made us learn 'em, an' somehow I minded them when I saw the water."

"Repeat them again," exclaimed Mr. Staunton eagerly, as if afraid to let go the impression thus received.

Johnnie slowly and deliberately did as requested, without comment.

"Thank you, thank you," said Mr. Staunton, when the boy had finished, adding sadly, "I wish I could give you some money, for you must need it greatly; but I have not a copper in my pocket."

"I have one and fivepence in my pocket for breakfast," said Johnnie, cheerfully, "and many mornings we be worse hoff; thank you all the same Measter."

"Good-bye then, and God bless you!" said Mr. Staunton, and passed on quickly, leaving Johnnie and his crutch far behind.[41]

Half-an-hour's speedy walking brought Mr. Staunton home to his own door, a humbler and more patient man. He no sooner entered the sitting-room than his wife met him with a bright smile, saying, "Here is an order for a picture, Paul; it came after you left, and see the enclosed cheque for a hundred pounds. Are we not rich, my husband? and did I not say 'the night was darkest just before dawn?'"

"Oh! my God," exclaimed the poor man, sinking on his knees, and remembering with a thankful heart the danger he had just escaped; "Oh! my God, I do not deserve this great kindness, 'Lord be merciful to me a sinner;'" and Mrs. Staunton, sinking down beside him, changed the "me" to "us," and echoed the petition most fervently.

After a few minutes thus spent, Paul was able to tell his wife what had just happened to him, and how he had been saved from, it might be, the commission of a terrible crime by the words of a poor lame boy; and the kind wife wept while she thanked God for his deliverance, saying through her tears: "Ah! my husband, you see the very hairs of our head are all numbered, and not a sparrow can fall to the ground[42] without our heavenly Father's permission. He sent the boy with the message, and His providence, though unseen, was watching over your steps."

"Yes, I see it all Nest," answered Mr. Staunton, "and I humbly pray that the lesson I have now been taught may never be forgotten. I thought, in my pride and self-sufficiency, that I could be independent of God, but He has showed me differently."

That day was but the beginning of good things to Paul Staunton, and though he still had many trials and difficulties to encounter, he never let go his faith in an all-wise God. A few months later, on the death of Mr. Staunton's rich uncle, when he succeeded to a large fortune, they received the gift with a humble, grateful spirit, and he tried, as far as he could, to seek out and help those who once, like himself, were on the brink of despair.

Amongst the first that he sought to discover and reward was the little water-cress boy, who had been the means, under Providence, of saving him from destruction, and he left no stone unturned to find out his abode. Policemen were engaged to help him in the search, but all means[43] seemed in vain, for no trace could now be found of the child, once a familiar sight in the neighbourhood where he gained his bread.

"I love to see this day well kept by rich and poor; it is a great thing to have one day in the year, at least, when you are sure of being welcome wherever you go, and of having, as it were, the world all thrown open to you."

Washington Irving.

Christmas time had come, and even to the dwellers in poor lanes and closes there were tokens of its presence; for here and there might be seen ragged, dirty children blowing penny trumpets, or sucking oranges; while the streets in the fashionable part of the town were filled with well-dressed boys and girls, with their spruce nurses, carrying all sorts of beautiful toys.

Here went a butcher's lad driving past, with a sprig of holly in his coat and evergreens at his horse's head; while the fat turkeys lay in his cart side by side, between pieces of prime beef, all covered with red berries and glancing[45] green leaves. Then the boy followed in the fish-cart, he and his horse both showing signs of Christmas having come. A savour of ginger-bread and other good things issued from the baker's shop, and the windows of the confectioner were a perfect fairyland of bright and beautiful things, not to speak of the bazaars and toy shops, with their trees hung with lamps and balls of brilliant colours.

The Christmas sun shone on that morning into the small room of Johnnie Moreland; but Johnnie was too ill to rise from his bed and join the merry groups on the street. He was very happy, though; perhaps there was not a happier child in London, in spite of his hard, racking cough and aching head, and he watched Anne with pleasure going off to the meeting in the mission school and church.

"What nice hymns you'll sing, Anne," said Johnnie, "and you'll hear about Jesus and heaven. I should like to have gone wid you."

Anne leant down and kissed him, saying gently, "I'll tell you all about them things when I come back, Johnnie; only I do wish you could have come too, and mother as well."

"I am glad you are going though," said Mrs.[46] Moreland, giving Johnnie a little hot tea and toast for his breakfast, of which the boy would not partake without his customary blessing. Mrs. Moreland, since Johnnie was too feeble to help to earn bread for the family, had turned over a new leaf, and never entered the gin-shop. The good example of her children was not lost upon the poor ignorant woman, while remorse for the treatment Johnnie had been subjected to, in having been tasked beyond his strength for her self-indulgence, helped to make her a different character. By the aid of friends that the children had made in the mission-school, and the little assistance Johnnie's teacher could give them, she was able to make a scant livelihood, and even provide the sick boy with a few comforts.

By-and-by, Anne returned from church, and Johnnie's eyes glistened with pleasure as she described how pretty it looked, hung with evergreens and verses of Scripture, oh! such beautiful verses: "Suffer little children to come unto Me," and "Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace." Then there were large tables in front of the pulpit, filled with nice things, apples, ginger-bread, and picture books, and "the music was so[47] grand," said Anne, "and the hymns, one was 'Rest for the Weary,' and another,

And the clergyman had told them such nice Bible stories; she had been sent away with pockets stuffed with good things, and the teacher had taken care that Johnnie should have his share, and mother too, for here was a warm flannel petticoat and gown for her, in this cold weather.

Johnnie listened attentively to all he heard, making Anne repeat again and again, and try to sing the hymn, "Yes, we'll gather at the river."

Christmas passed, and the New Year dawned, and still Johnnie lay. His mind sometimes wandered; but it was always of heaven he spoke,—the golden city, the Lamb on the white throne, the elders around it, and of the water of life. Strange words these were for the rough neighbours to hear, as they gathered, from time to time, round him; and tears would be seen stealing over cheeks unused to weep; then Johnnie would say, "Mother, my feet must be clean, for the ground there is pure, shining gold."

"I hope it may be the boy I'm in search of," said Mr. Staunton to a young man who was telling him of Johnnie Moreland. This young man was Johnnie's first friend and teacher.

"He answers to your description," was the reply, "I think you said you did not know his name."

"No, unfortunately," responded Mr. Staunton. "In the hurry and agitation of the moment I never thought of asking it; but he was lame, used a crutch, had a pale, pleasant face, with large, brown eyes. I would know him again among a thousand."

"Then come with me," said the stranger, "and we'll see if he is the right child. Will you drive or walk?"[49]

"Walk," replied Mr. Staunton, "that is to say, if you can spare time; for I would wish to see with my own eyes some of these miserable dwellings of poverty and woe."

So saying, he took the young teacher's arm, and together they went forth to seek the house of Johnnie Moreland. Resolutely they proceeded amid throngs of people and conveyances, in and out, among the closes and alleys, their hearts sore with the terrible sights they then witnessed,—women and men fighting and swearing, or lying drunk on the pavement; children almost naked, shivering with cold and hunger, holding out poor thin hands for a copper to buy bread.

At last the old, tumble-down tenement was reached, and they climbed the frail, rickety stair, and paused at the half-open door of a room on the top landing.

"Hark," said the young man, "do you hear a child's voice?"

They listened, and heard the verses of a hymn being repeated. It was this:—

Gently they tapped at the door, which was opened by Anne, who smiled brightly when she saw her kind friend.

"Johnnie will be so happy to see you," she[51] said, "for he wearies for you to come;" and so saying, she ushered them into the room, where the sick boy lay on his little bed, his face white and pinched, but a brightness in his eyes which showed the peace of the heart.

"Mother has gone out," he said, holding out his thin, wasted hand, "but Anne was reading to me, oh! such pretty verses, and I were thinking of the trip you took us in summer to the grand forest, where I saw the waters and the flowers,—them must be somethink like heaven."

"Heaven will be far, far grander than all that, Johnnie," answered his friend, kindly adding, "but I have brought a gentleman to see you to-day."

"My little fellow, do you remember me?" said Mr. Staunton, drawing near the bed, convinced that he was the boy he had sought so anxiously.

"No," replied Johnnie, musing, "don't think I nowhere saw you before."

"Yes, yes, Johnnie, you did," replied Mr. Staunton. "Don't you remember a gentleman who once spoke to you when you were looking at the river, and repeating the verse of Scrip[52]ture, 'There is a river, the streams whereof make glad the city of our God?'"

"Ah! yes," exclaimed Johnnie, a sudden light breaking over his face; "but you be'nt he; he were pale and sadlike."

"Yes Johnnie, I am the same, though I may look different; and as I am now a rich man, I have come to see you, and take you where you shall be well cared for, and nursed, and, please God you, yet may get well."

"How kind of you," replied the boy, amazed at the tidings, adding, "but what made you think on me."

"Just because I loved you, and you know our Saviour, when on earth loved little children, and said, 'Of such is the kingdom of Heaven.'"

"But Mother, and Anne, and Dick,—oh! you are kind, but I would rather be with them, for Anne to say hymns to me, and my teacher to come and see me."

"But Anne will go and visit you often, and so will your friend here, and I will arrange for your mother to go with you, and be your nurse, and you will have good and warm clothing and everything nice."

"Oh! sir," said Johnnie, "I can say nothink[53] to thank you. I will just do what you and teacher say is best."

Just then Mrs. Moreland entered, she had been to the shop for some more needlework, and great was her astonishment and thankfulness when she heard Mr. Staunton's kind offer.

Johnnie Moreland, the doctors say, is now improving, under careful treatment in an hospital, in which his mother is one of the nurses, and a good and kind one she makes. Dick and Anne have been boarded in a comfortable home, and are sent to school by their kind friend.

Mr. Staunton still pursues his beloved art, but now only as a recreation, and Nest has as much faith in him as ever, and her face beams kindly on him at his easel. Over the handsome mantlepiece, in his fine mansion, may be seen his last work, which the connoisseurs he loves to assemble round his hospitable table, declare is one of great merit. It represents a lame boy seated on a sunny bank on the edge of a forest, with a purling stream flowing near. It is an Arab of the city, viewing for the first time the flowers and the clear waters, and listening to the song of birds. He has a strange, bewildered expression on his face, half pleasure, half wonder.[54] The scene represents the visit to the forest, which was so well remembered, and the form and features are those of Johnnie Moreland.

In a dark, dingy-looking room, in a public house in Westminster, there might have been seen, a few years ago, a number of boys gathered together. A stranger would have been puzzled to know what they were about.

These boys are thieves, and they are met to practice the art of pocket-picking.

Many of them are well known at the various Police Offices in London. Committed to prison again and again, they leave it to follow their old trade. One of them is called Dick Cave—let us follow him, and learn his history.

His bringing up was a strange one, but, alas! there are many wretched boys who could tell the same tale.

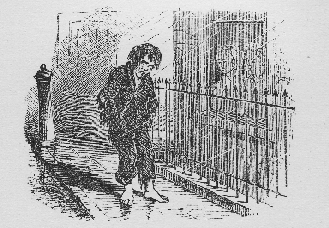

His mother had taught him one thing—to beg. When he was left like an orphan, he had not a[56] single relation in the world to care for him; but, as he was clever at begging, he was taken by a man who kept a thieves' lodging-house, and was expected to beg his own living. Many a time did poor little Dick make a door-step his bed, rather than return to meet the kicks and blows that awaited him. He dragged on this miserable life till he was about eight years old, when he ran away from his persecutor. For three years he never slept in a house, except when he got into prison for stealing. He usually slept under the arches of one of the bridges, along with other boys as wicked and as wretched as himself. He did not know that God watched over him, as he[57] lay there on his hard, cold bed; no one had ever instructed him about God or eternity; no mother had taught him to pray; he was living in Christian London, and yet was as ignorant of religion as the wild bushmen in Africa.

One cold evening in winter, Dick was wandering the streets, wondering how he should get his supper. It was raining, and he felt very miserable. He stood for some time at the window of a print-shop, looking at the pictures. One of them struck him especially: it was one that I daresay some of you have seen, "The Cottar's Saturday Night." Poor Dick gazed at it till his eyes swam with tears. Though he could not read, he could understand its meaning, and the contrast between that happy family round the fire, and his own life, stung him to the heart.

He exclaimed aloud, "I wish I was that lad!" and then, as if to get rid of the painful thoughts that oppressed him, he set off running as hard as he could. The next morning, however, he returned to his old course of life.

One Sabbath evening, he was hanging about the doors of a large church; not that he had any thoughts of going in—what did he know about worshipping God! He was waiting for the con[58]gregation to come out, to pursue his trade.

He was in the act of drawing out a handkerchief from a gentleman's pocket, when the owner of it turned sharply round. Dick had some impertinent apology on his lips, but the gentleman stopped him, by speaking to him in a friendly way, and inviting him to come to school next Sabbath. There was something in the kind voice and manner of the gentleman, that made Dick consent at once.

The next Sabbath found him in a ragged school. There were two teachers; one of them was the same gentleman Dick had met with the Sunday before, and he felt quite proud to find himself recognised.

This school had only been opened a few weeks; and as it was composed of the very worst of characters, many of them even more depraved than Dick, it had not much of the order and solemnity of a Sabbath school.

Dick Cave had not been long there before he and several of his companions felt a strong desire to leave off their thieving practices, and learn something better. He and another boy had been talking of this one Sunday morning, and finished by saying, as they had done many a time before[59]—"But what's the use? Who would employ us? What could we do?"

Dick started, and thought surely the teacher must have overheard them, when at the close of the school he said—

"Are there not many of you boys who are tired of your evil course of life? Would you not gladly leave it, and become honest lads?"

"Yes! yes!" shouted many a voice; while some (Dick among them) started to their feet, and said, "Only tell us how we can do it!"

The reason of the teacher speaking thus, was, that he had now an opportunity of recommending four boys to situations; and before the next Sabbath, four, who had distinguished themselves by their good conduct and attention at school, were placed in their situations. One of the fortunate candidates was our friend Dick. His joy at the change, and his gratitude to his kind teacher, knew no bounds.

"You, sir," said he, "are the only friend I ever had in my life."

"Well, Dick," said the gentleman, "be an industrious, good lad; mind your master's business as if it were your own; beware of following evil companions and your own bad habits, and I'm[60] your friend for life. And, Dick, if you will take the Bible for your guide, God will be your friend too."

"Well, sir," said Dick, brushing away a tear; "to tell the truth, I think it's a strange thing that God Almighty should care for such a wicked chap as me; but, somehow, I don't much like to talk about these things, because, you see, sir, it might look like hypocrisy."

The teacher read to him the beautiful words of Jesus, "I came not to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance;" and reminded him of the lesson they had lately had of the Prodigal Son. He gave him much good advice, as to how he should conduct himself in his new employment; and so they parted.

Dick shewed that kindness and instruction had not been lost upon him. He fulfilled his duties as errand-boy so well, that his master was pleased with him, and offered to raise his wages after a few months' trial.

One Sabbath, Dick lingered behind the rest of the boys, when the school was dismissed. He wanted to speak in private with his teacher.

"Well, Dick," said the latter, "what is the matter? you look as if you were in trouble."[61]

"Oh, sir, I shall never do for an errand-boy."

"Why not, Dick? Your master told me, only a few days ago, how well you suited him."

"Oh, but master does not know. The truth is, sir, I've been so long used to bad ways, that they are strong upon me—and—and—I'm come to tell you"——

"Well, Dick, go on."

"Why, sir, I'm afraid I shall be at my old trade again."

"Dick! What do you mean?"

"Oh sir, you don't know what it is to have been born a thief, as I may say. Many a time, when I have been going errands, I have been tempted to steal when I saw opportunities—it seems so natural to do as I have been used to all my life. Sometimes the thought has come so strong on me, that I have set off a running as hard as I could. I'm afraid, sir, the old habit will be too much for me some day, and then——"

"Then what, Dick?"

"Then, I should disgrace the school, and you, sir, that have been such a good friend to me—and I should be the same miserable wretch that I was when you picked me up. What must I do, sir?"[62]

"Do you think, Dick, that if I could walk along with you, when you are going on your errands, you could steal with me at your side?"

"No, sir, indeed!"

"Well, Dick, if you like, you may have a better friend than me along with you always—you cannot steal if He is with you."

"I know what you mean, sir; do you think I might make so bold as to ask Him?"

"Do I think?—Nay, I am sure. Is he not the 'friend of sinners?' Come, Dick, let us ask Him together to be your friend, to keep you safe in temptation, and deliver you from all evil." They knelt and prayed together.

Many a time after that did that poor orphan lad pray to his Father in heaven; and vagabond, thief, as he had been, he found that there was pardon and a Father's blessing for him, through Jesus, "the friend of sinners."

His kind teacher kept his promise that he would be a friend to him. When, by the exertions of some benevolent people, a number of boys from the different ragged schools were provided with means to emigrate to Australia, through his recommendation Dick Cave was one of them.[63]

He often writes to his old teacher, and delightful it is to read his letters, so full of gratitude to him for his kind efforts for his good, and to God for having plucked him as a brand from the burning.

Reader, is it thus with you? Dick Cave, ignorant, depraved as he was, heard and obeyed the voice of God; have you?

If your mercies and your privileges are greater than his—if your temptations are less—remember that "to whomsoever much is given, of him shall much be required."

1. page 28—corrected 'trig' to 'trim'

2. page 53—removed repeated 'of' in sentence "It is an Arab of of the city,..."

Throughout book, replaced 'Johnny' with 'Johnnie' to reflect book title