* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXXII, No. 3 (March 1848)

Date of first publication: 1848

Author: George R. Graham

Date first posted: Mar. 13, 2009

Date last updated: Jan. 13, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20090306

This ebook was produced by: David T. Jones, Juliet Sutherland, Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXII. March, 1848. No. 3.

Table of Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

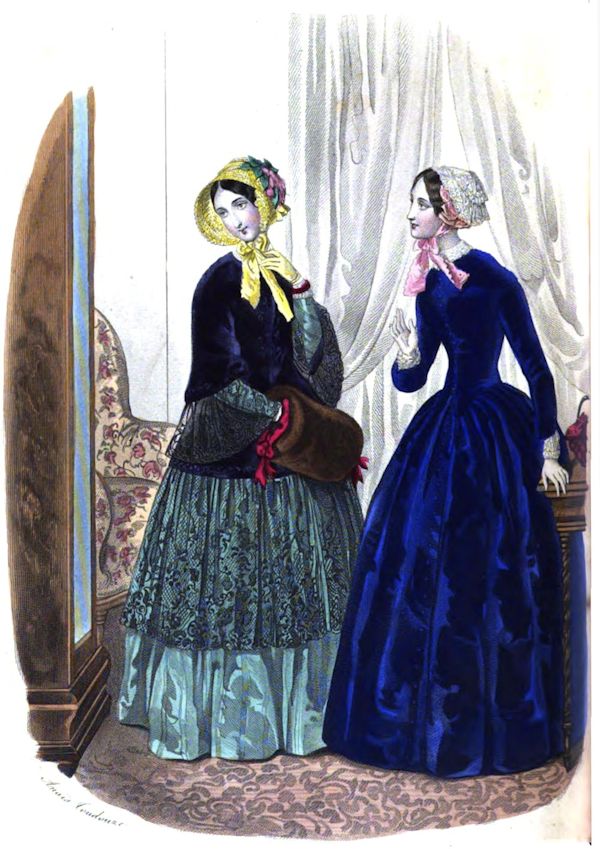

Anaïs Toudouze

LE FOLLET

Boulevart St. Martin, 61.

Robes de Mme. Mercier, r. Nve. des Pls. Champs, 82.

Bonnet de Mlle. Fleury, gal. de la Madeleine, 7—Manchons du Cardinale, bt. Poissoniere 9.

Chapeau de Mme. Leclère, r. St. Honoré, 335bis.—Dentelles de Violard, r. Choiseul, 2bis.

Fleurs de Chagot—Gants Xveline, r. de la Paix, 18-20—Chaussures Meier, r. Tronchet, 17

Graham’s Magazine.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXII. PHILADELPHIA, March, 1848. No. 3.

———

BY FRANK BYRNE.

———

In which the reader is introduced to several of the dramatis personæ.

On the evening of the 25th of March, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and thirty-nine, the ship Gentile, of Boston, lay at anchor in the harbor of Valetta.

It is quite proper, gentle reader, that, as it is with this ship and her crew that you will chiefly have to do in the following yarn, they should be severally and particularly introduced to your notice.

To begin, then. Imagine yourself standing on the parapet of St. Elmo, about thirty minutes past five o’clock on the evening above mentioned; the Gentile lies but little more than a cable’s length from the shore, so that you can almost look down upon her decks. You perceive that she is a handsome craft of some six or seven hundred tons burthen, standing high out of water, in ballast trim, with a black hull, bright waist, and wales painted white. Her bows flare very much, and are sharp and symmetrical; the cut-water stretches, with a graceful curve, far out beyond them toward the long sweeping martingal, and is surmounted by a gilt scroll, or, as the sailors call it, a fiddle-head. The black stern is ornamented by a group of white figures in bas relief, which give a lively air to the otherwise sombre and vacant expression, and beneath the cabin-windows is painted the name of the ship, and her port of register. The lower masts of this vessel are short and stout, the top-masts are of great height, the extreme points of the fore and mizzen-royal poles, are adorned with gilt balls, and over all, at the truck of the main sky-sail pole, floats a handsome red burgee, upon which a large G is visible. There are no yards across but the lower and topsail-yards, which are very long and heavy, precisely squared, and to which the sails are furled in an exceeding neat and seaman-like manner. The rigging is universally taut and trim; and it is easy to perceive that the officers of the Gentile understand their business. The swinging-boom is rigged out, and fastened thereto, by their painters, a pair of boats, a yawl and gig, float lovingly side by side; and instead of the usual ladder at the side, a handy flight of accommodation steps lead from the water-line to the gangway.

Now, dear reader, leaving the battlements of St. Elmo, you alight upon the deck of our ship, which you find to be white and clean, and, as seamen say, sheer—that is to say, without break, poop, or hurricane-house—forming on each side of the line of masts a smooth, unencumbered plane the entire length of the deck, inclining with a gentle curve from the bow and stern toward the waist. The bulwarks are high, and are surmounted by a paneled monkey-rail; the belaying-pins in the plank-shear are of lignum-vitæ and mahogany, and upon them the rigging is laid up in accurate and graceful coils. The balustrade around the cabin companion-way and sky-light is made of polished brass, the wheel is inlaid with brass, and the capstan-head, the gangway-stanchions, and bucket-hoops are of the same glittering metal. Forward of the main hatchway the long-boat stands in its chocks, covered over with a roof, and a good-natured looking cow, whose stable is thus contrived, protrudes her head from a window, chews her cud with as much composure as if standing under the lee of a Yankee barn-yard wall, and watches, apparently, a group of sailors, who, seated in the forward waist around their kids and pans, are enjoying their coarse but plentiful and wholesome evening meal. A huge Newfoundland dog sits upon his haunches near this circle, his eyes eagerly watching for a morsel to be thrown him, the which, when happening, his jaws close with a sudden snap, and are instantly agape for more. A green and gold parrot also wanders about this knot of men, sometimes nibbling the crumbs offered it, and anon breaking forth into expressions which, from their tone, evince no great respect for some of the commandments in the Decalogue. Between the long-boat and the fore-hatch is the galley, where the “Doctor” (as the cook is universally called in the merchant service) is busily employed in dishing up a steaming supper, prepared for the cabin mess; the steward, a genteel-looking mulatto, dressed in a white apron, stands waiting at the galley-door, ready to receive the aforementioned supper, whensoever it may be ready, and to convey it to the cabin.

Turning aft, you perceive a young man pacing the quarter-deck, and whistling, as he walks, a lively air from La Bayadere. He is dressed neatly in a blue pilot-cloth pea-jacket, well-shaped trowsers, neat-fitting boots, and a Mahon cap, with gilt buttons. This gentleman is Mr. Langley. His father is a messenger in the Atlas Bank, of Boston, and Mr. Langley, jr. invariably directs his communications to his parent with the name of that corporation somewhere very legibly inscribed on the back of the letter. He is an apprentice to the ship, but being a smart, handy fellow, and a tolerable seaman, he was deemed worthy of promotion, and as his owner could find no second mate’s berth vacant in any of his vessels, the Gentile has rejoiced for the last twelve months in the possession of a third mate in the person of Mr. Langley. He is about twenty years of age, and would be a sensible fellow, were it not for a great taste for mischief, romance, theatres, cheap jewelry, and tight boots. He quotes poetry on the weather yard-arm, to the great dissatisfaction of Mr. Brewster, (to whom you will shortly be introduced,) who often confidentially assures the skipper that the third mate would have turned out a natural fool if his parents had not providentially sent him to sea.

But while you have been making the acquaintance of Mr. Langley, the steward has brought aft the dishes containing the cabin supper. A savory smell issues from the open sky-light, through which also ascends a ruddy gleam of light, the sound of cheerful voices, and the clatter of dishes. After the lapse of a few minutes the turns of Mr. Langley in pacing the deck grow shorter, and at last, ceasing to whistle and beginning to mutter, he walks up to the sky-light and looks down into the cabin below. Gentle reader, place yourself by his side, and now attend as closely as the favored student did to Asmodeus.

The fine-looking seaman reclining upon the cushioned transom, picking his teeth while he scans the columns of a late number of the Liverpool Mercury, is Captain Smith, the skipper, a regular-built, true-blue, Yankee ship-master. Though his short black curls are thickly sprinkled with gray, he has not yet seen forty years; but the winds and suns of every zone have left their indelible traces upon him. He is an intelligent, well-informed man, though self-taught, well versed in the science of trade, and is a very energetic and efficient officer.

The tall gentleman, just folding his doily, is the mate of the ship, Mr. Stewart. You would hardly suppose him to be a sailor at the first glance; and yet he is a perfect specimen of what an officer in the merchant service should be, notwithstanding his fashionably-cut broadcloth coat, white vest, black gaiter-pants, and jeweled fingers. He is dressed for the theatre. Mr. Stewart is a graduate of Harvard, and at first went to sea to recover the health which had been somewhat impaired by hard study; but becoming charmed with the profession, he has followed it ever since, and says that it is the most manly vocation in the world. He is a great favorite with the owner of the ship; and when he is at Boston, always resides with him. He will command a ship himself after this voyage. His age is twenty-eight. Mr. Stewart is a handsome man, a polite gentleman, an accomplished scholar, a thorough seamen, a strict but kind officer, a most companionable shipmate, and, in one word—a fine fellow.

Next comes Mr. Brewster, the second mate. That is he devouring those huge slices of cold beef with so much gusto, while Langley mutters, “Will he never have done!” He with the blue jacket, bedizzened so plentifully with small pearl buttons, the calico shirt, and fancifully-knotted black silk cravat around his brawny neck.

Mr. Micah Brewster hails from Truro, Cape Cod, and, like all Capemen, is a Yankee sailor, every inch of him. He commenced going to sea when only twelve years old, by shipping for a four months’ trip in a banker; and in the space of fourteen years, which have since elapsed, he has not been on shore as many months. He is complete in every particular of seamanship, and is, besides, a tolerably scientific navigator. He knows the color and taste of the water all along shore from Cape Farewell to the Horn, and can tell the latitude and longitude of any place on the chart without consulting it. Bowditch’s Epitome, and Blunt’s Coast Pilot, seem to him the only books in the world worth consulting, though I should, perhaps, except Marryatt’s novels and Tom Cringle’s Log. But of matters connected with the shore Mr. Brewster is as ignorant as a child unborn. He holds all landsmen but ship-builders, owners, and riggers, in supreme contempt, and can hardly conceive of the existence of happiness, in places so far inland that the sea breeze does not blow. A severe and exacting officer is he, but yet a favorite with the men—for he is always first in any emergency or danger, his lion-like voice sounding loud above the roar of the elements, cheering the crew to their duty, and setting the example with his own hands. He is rather inclined to be irritable toward those who have gained the quarter-deck by the way of the cabin-windows, but, on the whole, I shall set him down in the list of good fellows.

That swarthy, curl-pated youngster, in full gala dress for the theatre, drawing on his gloves, and hurrying Mr. Stewart, is, dear reader, your most humble, devoted, and obedient servant, Frank Byrne, alias, myself, alias, the ship’s cousin, alias, the son of the ship’s owner. Supposing, of course, that you believe in Mesmerism and clairvoyance, I shall not stop to explain how I have been able to point out the Gentile to you, while you were standing on the bastion of St. Elmo, and I all the while in the cabin of the good ship, dressing for the theatre, and eating my supper, but shall immediately proceed to inform you how I came there, to welcome you on board, and to wish you a pleasant cruise with us.

About two years ago, (I am speaking of the 25th of March, A. D. 1839, in the present tense,) I succeeded in persuading my father to gratify my predilection for the sea, by putting me on board of the Gentile, under the particular care of Captain Smith, to try one voyage—so I became the ship’s cousin. Contrary to the predictions of my friends, I returned determined to go again, and to become a sailor. Now a ship’s cousin’s berth is not always an enviable one, notwithstanding the consanguinity of its occupant to the planks beneath him, for he, usually feeling the importance of the relationship, is hated by officers and men, who annoy him in every possible way. But my case was an exception to the general rule. Although at the first I was intimately acquainted with each of the officers, I never presumed upon it, but always did my duty cheerfully and respectfully, and tried hard to learn to be a good seaman. As my father allowed me plenty of spending money, I could well afford to be open-handed and generous to my shipmates, fore and aft; and this good quality, in a seaman’s estimation, will cover a multitude of faults, and endears its possessor to his heart. In fine, I became an immense favorite with all hands; and even Mr. Brewster, who at first looked upon my advent on board with an unfavorable eye, was forced to acknowledge that I no more resembled a ship’s cousin than a Methodist class-leader does a midshipman.

Mr. Stewart and myself had always been great friends before I went to sea. When I first came on board, Mr. Langley, who had been my school-mate and crony, was, though one of the cabin mess, only an apprentice, and had not yet received his brevet rank as third mate—Mr. Stewart, of course, stood his own watch, and chose Langley and myself as part of it. The mate generally kept us upon the quarter-deck with him, and many were the cozy confabs we used to hold, many the choice cigars we used to smoke upon that handy loafing-place, the booby-hatch, many the pleasant yarns we used to spin while pacing up and down the deck, or leaning against the rail of the companion. As I have said, Mr. Stewart was a delightful watch-mate—and Bill Langley and I used to love him dearly, and none the worse that he made us toe the line of our duty. He always, however, appeared to prefer me to Langley, and to admit me to more of his confidence. Since Bill’s promotion we had not seen so much of the mate, but still, during our late tedious voyage from Calcutta, he had often come upon deck in our watch, and hundreds of long miles of the Indian Ocean had been shortened in the old way.

Gentle reader, you are as much acquainted with the Gentile, and the quint who compose her cabin mess, as you could hope to be at one interview.

——

News from Home.

Mr. Langley had just commenced his supper with a ravenous appetite, stimulated by the tantalizing view of our previous gastronomic performances, which he had had through the sky-light, the mate and myself were on the point of going on deck to go ashore, the captain had just lighted a second cigar, when Mr. Brewster, who had relieved poor Langley in the charge of the deck, made his appearance at the cabin door, bearing in his hands a large packet.

“She’s in, sir!” he shouted, “she came to anchor in front of the Lazaretto while we were at supper, and Bill here didn’t see her. The quarantine fellows brought this along. Bill, you must be a bloody fool, to let a ship come right under our stern, and sail across the bay, and not know nothing about it.”

Langley, whose regards for the supper-table had drawn his attention from the arrival of a ship which had been expected by us for more than a week, and by whom we had anticipated the receipt of the packet the skipper now held in his hands, Langley, I say, blushed, but said nothing, and turned toward the captain, who, with trembling hands, was cutting the twine which bound the precious bundle together.

Now our last letters from Boston had been written more than a year before, had been read at Calcutta, since then we had sailed fifteen thousand miles from Calcutta to Trieste, and from Trieste to Valetta, and here we had been pulling at our anchor for three weeks, waiting orders from my father by the ship which had just arrived; it is not wonderful, therefore, that the group which surrounded Capt. Smith were very pale, eager, anxious-looking men. How much we were to learn in ten minutes time; what bitter tidings might be in store for us in that little packet.

At last it is open, and newspapers and letters in rich profusion meet our gaze; with a quick sleight the captain distributes them, sends a half dozen to their owners in the forecastle by the steward, and then ensues a silence broken only by the snapping of seals, and the rattling of paper. Suddenly Mr. Stewart uttered an exclamation of surprise, and looking up from my letter, I noticed the quick exchange of significant glances between the captain and mate.

“You’ve found it out, then,” said the skipper.

The mate nodded in reply, and gathering up his letters, retired precipitately to his state-room.

At this juncture, Mr. Brewster, who had just finished the perusal of a very square, stiff-looking epistle, gave vent to a prolonged whistle.

“Beats thunder, I swear!” said he, “if the old woman haint got spliced again—and she’s every month of fifty-six years old.”

“That’s nothing,” cried Langley, “only think, father has left the Atlas Bank, and is now Mr. Byrnes’ book-keeper; and they talk of shutting up the Tremont theatre, and Bob here says that Fanny Ellsler is—”

“Avast there!” interrupted the skipper, “clap a stopper over all that, and stand by to hear where we are bound to-morrow, or next day. Have any of you found out yet?”

“No, sir,” cried Langley and I in a breath, “Home, I hope.”

“Not so soon,” replied Captain Smith, “as soon as maybe we sail for Matanzas de Cuba, to take aboard a sugar freight for the Baltic—either Stockholm or Cronstadt; so that when we make Boston-light it will be November, certain. How does that suit ye, gentlemen?”

I was forced to muster all my stoicism to refrain from whimpering; Mr. Langley gave utterance to a wish, which, if ever fulfilled, will consign the cities of Cronstadt, Stockholm, and Matanzas to the same fate which has rendered Sodom, Gomorrah, and Euphemia so celebrated. Mr. Brewster alone seemed indifferent. That worthy gentleman snapped his fingers, and averred that he didn’t care a d—n where he went to.

“Besides,” said he, “a trip up the Baltic is a beautiful summer’s work, and we shall get home in time for thanksgiving, if the governor don’t have it earlier than common.”

“Matanzas!” inquired Langley; “isn’t there where Mr. Stowe moved to, captain?”

“Yes,” replied the skipper, “he is Mr. Byrnes’ correspondent there—”

“Egad, then, Frank, we shall see the girls, eh, old fellow!” and Mr. Langley began to recover his serenity of mind.

“Beside all this,” added the skipper, “Frank has a cousin in Matanzas—a nun in the Ursuline Convent.”

“So I have just found out,” said I; “father bids me to be sure and see her, if possible, and says that I must ask you about it. It is very odd I never have heard of this before. By the bye, Bill, my boy, look at this here!” and I displayed a draft on Mr. Stowe for $200.

At this moment Mr. Stewart’s state-room door opened, and he appeared. It was evident that he had heard bad news. His face was very grave, and his manner forced.

“Frank,” said he, “you must excuse my company to-night. Langley will be glad to go with you; and as we sail so soon, I have a good deal to do—”

“But,” said I, hesitating, “may I inquire whether you have received bad news from home?”

“On the contrary, very good—but don’t ask any questions, Frank; be off, it is very late to go now.”

“Langley,” said I, as we were supping at a café, after the closing of the theatre, “isn’t it odd about that new cousin of mine?”

“Ay,” replied my companion, “and it is odd about Stewart’s actions to-night; and it will be odd if I don’t kiss Mary Stowe; and it will be odd if you don’t kiss Ellen; and it will be odd if I arn’t made second mate after we get home from this thundering long voyage; and, finally, it will be most especially odd if we find all our boat’s crew sober when we get down to the quay.”

Nothing so odd as that was the case; but after some little difficulty we got on board, and Langley and myself retired to the state-room which we held as tenants in common.

——

In which four thousand miles are gained.

We laid almost a week longer wind-bound. At last the skipper waxed impatient, and one fine morning we got out our boats, and with the help of the Pharsalia’s boats and crew, we were slowly towed to sea. Here we took a fine southwesterly breeze, and squared away before it. Toward night we had the coast of Sicily close under our lee, and as far away as the eye could reach, the snow-capped summit of Ætna, ruddy in the light of the setting sun, rose against the clear blue of the northern sky.

We had as fine a run to Gibralter as any seaman could wish; but after passing the pillars of Hercules there was no more good weather beyond for us until we crossed the tropic, which we did the 10th of May, in longitude about sixty degrees, having experienced a constant succession of strong southerly and westerly gales. But having passed the tropic, we took a gentle breeze from the eastward, and with the finest weather in the world, glided slowly along toward our destined port.

I shall never forget the evening and night after the 15th of May. We were then in the neighborhood of Turks Island, heading for the Caycos Pass, and keeping a bright look-out for land. It was a most lovely night, one, as Willis says, astray from Paradise; the moon was shining down as it only does shine between the tropics, the sky clear and cloudless, the mild breeze, just enough to fill our sails, pushing us gently through the water, the sea as glassy as a mountain-lake, and motionless, save the long, slight swell, scarcely perceptible to those who for long weeks have been tossed by the tempestuous waves of the stormy Atlantic. The sails of a distant ship were seen, far away to the north, making the lovely scene less solitary; the only sounds heard were the rippling at the bows, the low sough of the zephyr through the rigging, the cheeping of blocks, as the sleepy helmsman allowed the ship to vary in her course, the occasional splash of a dolphin, and the flutter of a flying-fish in the air, as he winged his short and glittering flight. The air was warm, fragrant, and delicious, and the larboard watch of the tired crew of the Gentile, after a boisterous passage of forty days from Gibralter, yielded to its somnolent influence, and lay stretched about the forecastle and waists, enjoying the voluptuous languor which overcomes men suddenly emerging from a cold into a tropical climate.

Mr. Langley, myself, and the skipper’s dog, reclined upon the booby-hatch. The first having the responsibility of the deck contrived to maintain a half upright position, and to keep one eye open, but the other two, prostrate by each others’ side, slumbered outright.

“What’s the time, Bill?” I asked, at length, rousing myself, and shaking off the embrace of Rover, who was loth to lose his bedfellow.

“‘We take no note of time,’” spouted the third mate, drawing his watch from his pocket. “For’ard, there! strike four bells, and relieve the wheel. Keep your eye peeled, look-out; and mind, no caulking.”

“Ay ay, sir,” was the lazy response, and in a moment more the ting-ting, ting-ting, of the ship’s bell rang out on the silent air, and proclaimed that the middle watch was half over, or, in landsmen’s lingo, that it was two o’clock, A. M.

“Lay along, Rover,” I muttered, preparing for another snooze.

“Oh! avast that Frank; come, keep awake, and let’s talk.”

“Talk!” said I, “about what, pray?”

“Oh! I don’t know,” replied Bill. “I tell you what, Frank, if it wasn’t for being cock of the roost myself, I should wish that Stewart headed this watch now. What fine times we used to have, eh?—but he has altered as well as the times—how odd he has acted by spells ever since we got that packet at Malta. I’m d—d if I don’t believe he got news of the loss of his sweetheart.”

“He never had any that I know of,” I rejoined, “but he certainly did hear something, for he has changed in his manner, and the skipper and he have long talks by themselves, and I heard Stewart tell him one day that after all it would have been better to have left the ship at Gibralter, and not gone the voyage.”

“Did he, though!” cried Langley; “in that case I should have been second mate—however, I’m glad he didn’t quit.”

“Thank you, Bill,” said a voice behind us; and turning in some confusion we beheld Mr. Stewart standing in the companion. “How is her head?” he continued, asking the usual question, to allow us to recover from our embarrassment.

“About west, sir,” replied Langley.

“Well, as the wind freshens a little and is getting rather to the nor’ard, you’d better give your larboard braces a pull or two, and then put your course rather north of west to hit the Pass.”

“Ay ay, sir,” said the third mate. “For’ard, there, come aft here, and round in on the larboard braces. Keep her up, Jack, about west nor’west.”

After the crew had complied with the orders of the officer they retired forward, and we of the quarter-deck seated ourselves on the booby-hatch.

“We were talking about you when you came on deck, sir,” said I, after a short silence.

“Ah! indeed,” replied the mate smiling.

“Yes,” said Langley, “we thought it was rather odd you hadn’t been on deck lately, to see whether we boys were not running away with the ship in your watch. It has been deuced lonesome these dark blowy nights along back. If you had been on deck to spin us a yarn it would have been capital.”

“Boys,” said the mate, taking out his cigar-case, “I’ve a great mind to spin you a yarn now.”

“Oh! do, by all means,” cried the third mate and the ship’s cousin together.

We lighted our cigars; the mate took a few puffs to get fairly under way, and then began.

——

The Mate’s Yarn.

“I’ve told you about a great many days’ works, boys, but there is one leaf in my log-book of which you as yet know nothing. It is now about six years since I was in this part of the world, for the first and only time. I was then twenty-two, and was second mate, Frank, of your father’s ship, the John Cabot. Old Captain Hopkin’s was master, and our present skipper was mate. One fine July afternoon we let go our anchor alongside of the Castle of San Severino, in Matanzas harbor. A few days after our arrival I was in a billiard-room ashore, quietly reading a newspaper, when one of the losing players, a Spaniard of a most peculiarly unpleasant physiognomy, turned suddenly around with an oath, and declared the rustling of the paper disturbed him. As several gentlemen were reading in different parts of the room I did not appropriate the remark to myself, though I thought he had intended it for me. I paid no attention to him, however, until, just as I was turning the sheet inside out, the Spaniard, irritated by another stroke of ill luck, advanced to me, and demanded that I should either lay the newspaper aside or quit the room. I very promptly declined to do either, when he snatched the paper from my hands, and instantly drew his sword. I was unarmed, with the exception of a good sized whalebone cane, but my anger was so great that I at once sprung at the scamp, who at the instant made a pass at me. I warded the thrust as well as I could, but did not avoid getting nicely pricked in the left shoulder; but, before my antagonist could recover himself, I gave him such a wipe with my cane on his sword-arm that his wrist snapped, and his sword dropped to the ground. Enraged at the sight of my own blood, which now covered my clothes in front, I was not satisfied with this, but applying my foot to his counter, two or three vigorous kicks sufficed to send him sprawling into the street. Captain Hopkins arrived just as the fracas was over, and instantly sent for a surgeon, and in the meantime I received the congratulations of all present on my victory. I learned that my man was a certain Don Carlos Alvarez, a broken down hidalgo, who had formerly been the master of a piratical schooner, at the time when Matanzas was the head-quarters of pirates, before Commodore Porter in the Enterprise broke up the haunt. When the surgeon arrived he pronounced my wound very slight, and a slip of sticking-plaster and my arm in a sling was thought to be all that was necessary. After Captain Hopkins and myself got on board that night, he told me a story, the repetition of which may somewhat surprise you, Frank. Do you remember of ever hearing that a sister of your father married a Cubanos merchant, some thirty odd years ago?”

“I remember hearing of it when a child,” I replied, “and father in his last letter says that I have a cousin now in the nunnery at Matanzas. I suppose she is a daughter of that sister.”

“You are right,” resumed the mate, sighing slightly. “Your grandfather had only two children. When your father was but a small boy, the whole family spent the winter in Havana, to recruit your grandmother’s health, while your grandfather collected some debts which were due him. While there, a young Creole merchant, heavily concerned in the slave-trade, became deeply enamored with your aunt, and solicited her hand. The young lady herself was nothing loth, but the elders disliked and opposed the match; the consequence was an elopement and private marriage, at which your grandfather was so exceedingly incensed that he disowned his daughter, and never afterward held any communication with her. Your aunt had two children, and died some fifteen years ago. Your father shortly after received this intelligence by means of a letter from the son, and the correspondence thus begun was continued in a very friendly manner. Señor Garcia, your uncle by marriage, became concerned, in a private way, like many other Cubanos merchants, in fitting out piratical craft, and one of his confidential captains was this same Alvarez whom I so summarily ejected from the billiard-room. Garcia died in 1830, leaving a large property to his children, and consigning the guardianship of the younger, a girl, to his friend Don Carlos Alvarez. The will provided that in case she should marry any person, but an American, without her guardian’s consent, her fortune should revert to her guardian; and in the choice of an American husband her brother’s wishes were not to be contravened. The reservation in favor of Americans was made at the entreaty of the brother, who urged the memory of his mother as an inducement. Now it so turned out that Don Carlos, though forty years old, and as ugly as a sculpin, became enamored with the beauty and fortune of his ward, and, hoping to win her, kept her rigidly secluded from the society of every gentleman, but especially that of the American residents. Pedro Garcia, the brother, whom Captain Hopkins represented to be a fine, manly fellow, was, however, much opposed to such a plan, and ardently desired that his sister should marry an American, being convinced that this was the only way for her to get a husband and save her fortune. ‘If,’ said Captain Hopkins, in conclusion, ‘some smart young Yankee could carry the girl off, it would be no bad speculation. Ben, you had better try yourself, you couldn’t please Mr. Byrne better.’

“‘Much obliged,’ I replied, ‘but Yankee girls suit my taste tolerably well, much better than pirates’ daughters, and I hope that I can please my owner well enough by doing my duty aboard ship.’

“‘Pshaw! she is not a pirate’s daughter exactly; she’s Mr. Byrne’s niece.’

“‘For all that,’ I answered, ‘I should expect to find my throat cut some fine morning.’

“‘Well, well,’ said the old skipper, ‘I only wish that I was a young man, for the girl is said to be as handsome as a mermaid, and as for money, I s’pose she’s worth devilish nigh upon two hundred thousand dollars.’

“The next day but one was Sunday, so after dressing myself in my go-ashore toggery, I went with the skipper to take another stroll in the city. We dined at a café, and then hearing the cathedral bells tolling for vespers, I concluded to leave the skipper to smoke and snooze alone, and go and hear the performances. It was rather a warm walk up the hill, and, upon arriving at the cathedral, I stopped awhile in the cool airy porch to rest, brush the dust from my boots, arrange my hair and neckcloth, and adjust my wounded arm in its sling in the most interesting manner. Just as I had finished these nice little preliminaries, a volante drove up to the door, which contained, why, to be sure, only a woman, but yet the loveliest woman I have ever seen in any part of the world. Yes, Bill, your little dancer at Valetta ought not to be thought of the same day.

“Well, boys, I fell in love incontinently at first sight, and was taken all aback, but inspired by a stiff glass of eau-de-vie which I had taken with my pineapple after dinner, I forged alongside, before the negro postillion, cased to his hips in jack-boots, could dismount, and offered my hand to assist the lady to alight from the carriage. She at first gave me a haughty stare, but finally putting one of the two fairest hands in the world into my brown paw, she reached terra firma safely.

“‘Thank you, señor,’ said she, with a low courtesy, after I had led her into the church.

“‘Entirely welcome, ma’am,’ I replied, as my mother had taught me to do upon like occasions, ‘and the more welcome, as I perceive you speak English so fluently, that you must be either an English woman or my own countrywoman.’

“‘I am a Cubanos, señor,’ said the lady, with a smile, ‘but my mother was an American, and I learned the language in the nursery—but, señor, again I thank you for your gallantry, and so adios.’ She dipped her finger in the holy-water vase, crossed herself, and then looking at me from under her dark fringed eyelids with a most bewildering glance, and a smile which displayed two dazzling rows of pearls between her ruby lips, she glided into the church.

“‘Who is your mistress?’ cried I, turning to the negro postillion, but that sable worthy could not understand my question. The most expressive pantomimes were as unavailable as words, and so in despair I turned again into the porch, and stood in a reverie. I was clearly a fathom deep in love, and as my extreme height is but five feet eleven and a half, that is equivalent to saying that I was over head and ears in love with the strange lady. I began to talk to myself. ‘By Venus!’ said I, aloud, ‘but she is an angel, regular built, and if I only could find out her name and—’

“A smothered laugh behind me reminded me that so public a place was hardly appropriate for soliloquizing about angels. I turned in some vexation and encountered the laughing glance of a well dressed young man, apparently about twenty-five, who had probably been edified by my unconscious enthusiasm.

“‘You are mistaken, señor,’ said he in English, and looking quizzical; ‘those images in the niches are said to represent saints and not angels, though I must own they are admirably calculated to deceive strangers. As you said you wished to know their names, I will tell them to you—that is San Pablo, and that is San Pedro, and that is—’

“‘You are kind, sir,’ said I, interrupting him angrily, ‘but I’ve heard of the twelve apostles before.’

“‘I want to know, as your countrymen say,’ retorted the stranger, with a good-natured mocking laugh.

“I fired up on this. ‘Señor,’ said I, ‘if my countrymen are not so polished in their speech as the Castilians and their descendants, they never insult strangers needlessly. I have been insulted once before in your city within a few days, and allow me to add for your consideration, that the rascal got well kicked—’

“‘You are very kind to give me such fair warning,’ replied the stranger, bowing, ‘but allow me to ask whether the name of this person you punished is Alvarez?’

“‘I have heard so, and if he is a connection of yours I am—’

“‘Stay, señor, don’t get into a passion; believe me, that I thank you most heartily for the good service you performed on the occasion to which we allude. I only wish that I can be of use to you in return.’

“‘Well, then, señor,’ I replied, much mollified, and intent upon finding out my fair incognito, ‘a lady just now passed through into the church, and if you can only tell me who she is, I will promise to flog you all the bullies in Cuba.’

“‘Ah, that would be a long job, dear señor, but if you will accept my arm into the church, and point out the angel who has attracted your notice, I will tell you her name and the part of heaven in which she resides. She was very beautiful I suppose?’

“‘Oh! exquisitely beautiful.’

“‘Come, then, I am dying to find out which of our Matanzas belles has had the good fortune to fascinate you—this way—do you use the holy water?’

“In we went and found the organ piping like a northeast snow squall, and the whole assembly on their knees. The stranger and myself ensconced ourselves near a large pillar, and I stood by to keep a bright look out for the lady.

“At last I discovered her among a group of other women, kneeling at the foot of an opposite pillar.

“‘There she is,’ I whispered to my companion, who had knelt upon his pocket-handkerchief.

“‘Well, in a moment,’ he replied. ‘I’m in the middle of a crooked Latin prayer just now, and have to tell you so in a parenthesis.’

“A turn came to the ceremonies, and all hands arose.

“‘Sæcula sæculorum,’ muttered my companion, rising, ‘Amen! now where’s your lady?’

“‘Yonder, by the pillar,’ I whispered, in a fit of ecstasy, for my beautiful unknown in rising had recognized me, and given me another thrilling glance from her dark eyes.

“‘But there are a score of pillars all around us,’ urged the stranger, ‘point her out, señor.’

“‘Well, then,’ said I, extending my arm, ‘there she is; you can’t see her face to be sure, but there can be only one such form in the world. Isn’t it splendid?’

“‘There are so many ladies by the pillar that I cannot tell to a certainty which one you mean,’ whispered my would-be informant. Stooping and glancing along my arm with the precision of a Kentucky rifleman, I brought my finger to bear directly upon the head of the unknown, who, as the devil would have it, at this critical juncture turned her head and encountered the deadly aim which we were taking at her.

“‘That’s she,’ said I, dropping my arm, which had been sticking out like a pump brake, ‘that’s she that just now turned about and blushed so like the deuce—do you know her?’

“‘Yes, but I can’t tell you here,’ was the laconic reply of my companion; ‘come, let’s go. You are sure that is the lady,’ he continued, when we had gained the street.

“‘Sure! most certainly; can there be any mistake about that face; besides, didn’t you notice how she blushed when she recognized me?’

“‘Maybe,’ suggested my new friend, ‘she blushed to see me.’

“‘Well,’ said I, ‘I don’t know to be sure, but I think that the emotion was on my account; but don’t keep me in suspense any longer, tell me who she is; can I get acquainted with her?’

“‘Softly, softly, my friend, one question at a time. Step aboard my volante, and as we drive down the street I’ll give you the information you so much desire. Will you get in?’

“I climbed aboard without hesitation, and was followed by my strange friend; the postillion whipped up and we were soon under weigh.

“‘Now,’ resumed my companion, ‘in reply to your first and oft-repeated inquiry, I have the honor to inform you that the lady is my only sister. As to your second question—I beg you wont get out—sit still, my dear sir, I will drive you to the café—your second question I cannot so well answer. It would seem that my sister herself is nothing loth—sit easy, sir, the carriage is perfectly safe—but unfortunately it happens that the gentleman who has the control of her actions, her guardian, dislikes Americans extremely; and I have reason to believe that he has taken a particularly strong antipathy to you. Indeed, I have heard him swear that he’ll cut your throat—pardon me, Mr. Stewart, for the expression, it is not my own.’

“Surprise overcame my confusion. ‘Señor,’ cried I, interrupting him, ‘it seems you know my name, and—’

“‘Certainly I do—Mr. Benjamin Stewart, of the ship John Cabot.’

“‘Señor,’ I cried, half angrily, ‘since you know my address so well, will you not be so kind as to favor me with yours?’

“‘Mine! oh yes, with pleasure, though I now recollect that I have omitted to state my sister’s name—hers first, if you please; it is Donna Clara Garcia.’

“‘And yours is Pedro Garcia.’

“‘Exactly, with a Don before it, which my poor father left me. You perceive, Mr. Stewart, by what means I knew you after your warning about the kicking, eh? I suspected it was yourself, when I saw an American gentleman with his arm in a sling, and so I made bold to accost you in the midst of your rhapsody about angels—’

“‘Ah! Don Pedro,’ I stammered in confusion, when I recalled the ludicrous scene, ‘how foolish I must appear to you.’

“‘For what, señor—for thinking my sister handsome? You do my taste injustice. I think so myself.’

“We rode on in silence a few minutes. I recalled all that Captain Hopkins had told me about my new acquaintance, his sister, and her guardian. I took heart of grace, and determined to know more of the beautiful creature whom I had now identified; but when I turned toward my companion, his stern expression, so different from the one his features had hitherto borne, almost disheartened me.

“‘Don Pedro,’ said I, with hesitation, ‘may I ask if you are angry at the trifling manner with which I have spoken of your sister before I knew her to be such?’

“‘Is it necessary for me to assure you to the contrary?’ he asked, with a smile again lighting up his face.

“‘But if,’ I continued, ‘I should say that the admiration I have manifested is sincere, that even in the short time I have seen her to-day, I have been deeply interested, and that I ardently desire her acquaintance.’

“‘Why, señor, in that case, I should reply, that my sister is very highly honored by your favorable notice, and that I should do my possible to make you know each other better. If,’ he continued, ‘the case you have supposed be the fact, I think I can manage this matter, her old janitor to the contrary notwithstanding.’

“‘I do say, then,’ I replied, with enthusiasm, ‘that the sight of Donna Clara has excited emotions in my bosom I have never felt before. I shall be the happiest man in the world to have the privilege of knowing her.’

“‘Attend, then. Don Carlos is absent at Havana, and will probably remain so for a few days, until his wrist gets well; in the meantime, his sister acts as duenna over Donna Clara. She is quite a nice old lady, however, and allows my sister far greater liberty in her brother’s absence than ordinarily, as, for instance, to-day. I will get her to permit Clara to spend a few days at my villa down the bay—Alvarez himself would not dare to refuse this request, if—’ my companion stopped short, and his brow clouded. ‘But I forget the best of the matter,’ he continued a moment after, in a lively tone. ‘Señor, you will dine with me to-morrow, and spend a day or two with me. I keep bachelor’s hall, but I have an excellent cook, and some of the oldest wine in Cuba. Beside, you will see my sister. Will you honor me, Mr. Stewart?’

“I was transported, ‘Senior,’ I cried, ‘if Capt. Hopkins—’

“‘Oh! a fig for Hopkins,’ shouted my volatile friend, ‘he shall dine with me too. He is an ancient of mine—he dare not refuse to let you go. But there is the fine old sinner himself in the verandah of the café; now we can ask him.’

“We rattled up to the door, to the infinite astonishment of my worthy skipper, who was greatly surprised to see Don Pedro and his second mate on such excellent terms, and all without his intervention.

“‘Hillo!’ he shouted, ‘how came you two sailing in company?’

“The worthy old seaman was briefly informed of my afternoon’s adventures over a bowl of iced sangaree; and when Pedro made his proposition about the morrow’s dinner, and a little extra liberty for me, the reply was very satisfactory.

“‘Sartainly, sartainly,’ said he, ‘and I hope good will come of it.’

“‘Well, then,’ said Pedro, ‘as this matter is settled, I must take my leave. I shall expect you early, gentlemen. Adieu’—and, with a graceful bow, my new friend entered his carriage, and was driven away.

“‘Now,’ said the skipper, after our boat’s crew had cleared their craft from the crowd at the stairs, ‘now, Stewart, what do you think of the pirate’s daughter, my boy? D’ye see, I never happened to sight her, though her brother and I have been fast friends these five years. Is she so handsome, Ben?’

“‘Full as good-looking as the figure-head of the Cleopatra,’ replied I.

“‘Egad! you don’t say so!’ exclaimed the skipper, who thought that the aforesaid graven image on the cut-water of his old ship, far excelled the Venus de Medici in beauty of feature and form. ‘She must be almighty beautiful; and then, my son, she is as rich as the Rajah of Rangoon, who owns a diamond as big as our viol-block. Did you fall in love pretty bad, Ben?’

“‘Considerable,’ I replied, grinning at the old gentleman’s simplicity.

“‘By the laws, then, if you don’t cut out that sweet little craft from under that old pirate’s guns, you’re no seaman, that’s a fact! Egad! I should like to do it, and wouldn’t ask only one kiss for salvage, and you’ll be for having the whole concern.’

“The next morning I packed my portmanteau and dressed myself with unusual care. About ten the skipper and myself got aboard the gig, and pushed off for Don Pedro’s villa, which lay on the eastern shore of the bay, two miles from the city, and nearly opposite the barracks and hospital.

“We landed at a little pier at the foot of the garden; the house, embowered in a grove of orange and magnolia trees, was close at hand. Don Pedro met us on the verandah.

“‘Welcome! welcome!’ he cried; ‘how do you like the appearance of my bachelor’s hall? But come, let’s go in; my sister has arrived, and knows that I expect Captain Hopkins and Mr. Stewart, of the Cabot, and,’ he added, with a significant smile, ‘nothing more, though she has been very curious to find who the gentlemen is with whom I entered the church yesterday.’

“We entered the drawing-room, and there, sure enough, was my angel of the cathedral-porch. Her eye fell upon me as I passed the doorway, and, by the half start and blush, I saw that I was plainly recognized, and with pleasure. We were formally presented by Don Pedro, and, after the old skipper had been flattered into an ecstasy of mingled admiration and self-complacency, Donna Clara turned again to me.

“‘I do not know that I ought to have bid you welcome, Mr. Stewart,’ she said, with an arch smile, ‘you treated my poor guardian shamefully, I am told.’

“‘Yes,’ cried Pedro, ‘and just to let you know what a truculent person he is, know that yesterday he more than insinuated that he would serve me in the same way that he did Don Carlos.’”

“Land ho!” sung out the man on the look-out.

“Where away?” shouted Langley, walking forward.

“Pretty near ahead, sir; perhaps a point on our starboard bow, sir.”

“Land ho!” bellowed the man at the wheel, “just abeam, sir, to loo-ard.”

“What had I better do, sir?” inquired Langley, of the mate.

“I was looking at the chart just at night, and I should reckon the land ahead might be Mayaguana, and the Little Caycos under our lee.”

“Head her about west, then; but we shall have the lead going soon.”

We filled away before the wind, which had now veered again to the eastward, and in a few moments were dashing bravely on, sailing right up the moon’s wake toward the Pass, the land lying on each side of us like blue clouds resting on the horizon. We settled ourselves again on the hatch, lighted fresh cigars, and the mate resumed his broken yarn.

“It is getting late, boys, almost six bells, and I must cut my story a little short. I will pass over the dinner, the invitation to stay longer, Captain Hopkins’ consent, the undisguised pleasure and the repressed delight of Clara at this arrangement, and I will pass over the next two days, only saying that the memory of them haunts me yet; and that though at the time they seemed short enough, yet when I look back upon them, it is hard to realize they were not months instead of days, so much of heart experience did I acquire in the time. I found Clara to be every thing which the most exacting wife-hunter could wish—beautiful as a dream. Believe me, boys, I do not now speak with the enthusiasm of a lover, but such beauty is seldom seen on the earth. Added to this, she was intellectual, refined, accomplished, and highly educated. I went back four years in life, and with all the enthusiasm of a college student I raved of poetry and romance. We read German together, and we talked of love in French; and the musical tongue of Italy, it seemed to me, befitted her mouth better than her own sonorous native language, and when in conversation she would look me one of those dreamy glances which had at the first set my heart in agitation, it perfectly bewildered me. You needn’t smile, Langley, (poor Bill’s face was guilty of no such distortion,) but if your little danseuse should practice for years, she couldn’t attain to the delicious glance which my handsome creole girl can give you. The heavily-fringed eyelid is just raised, so that you can look as if for an interminable distance into the beautiful orb beneath, and at the end of the vista, see the fiery soul which lies so far from the voluptuous exterior.

“But, though I was madly in love, I had not yet dared with my lips to say so to the lady, whatever my eyes might have revealed; but Pedro was my confident, and encouraged me to hope.

“The third day of my sojourn on shore was spent in a visit to Don Pedro’s plantation in the vale, and it was dark when we arrived home. After the light refreshment which constitutes the evening meal of Cuba, Don Pedro pleaded business, and left the apartment—and for the first time that day I was alone with Clara.

“‘Now,’ thought I, ‘now or never.’

“If upon the impulse of the moment a man proceeds to make love, he generally does it up ship-shape; but if he, with malice aforethought, lays deliberate plans, he finds it the most awkward traverse to work in the world to follow them—but I did not know this. I sat by the table, and in my embarrassment kept pushing the solitary taper farther and farther from me, until at last over it went, and was extinguished upon the floor.

“‘I beg ten thousand pardons!’ cried I apologizing.

“‘N’importe,’ replied Clara, ‘there is a fine moon, which will give us light enough.’

“She rose and drew the curtain of the large bow-window, so common in the West Indian houses, and the rich moonlight, now unvexed by the dull glare of the taper, flowed into the apartment, bathing every object it touched with silvery radiance. Clara sat in the window, in the full glow of the light, leaning forward toward the open air, and I, with a beating heart, gazed upon her superb beauty. Shall I ever forget it? Her head leaned upon a hand and arm which Venus herself might envy; the jetty curls which shaded her face fell in graceful profusion, Madonna-like, upon shoulders faultless in shape, and white as that crest of foam on yonder sea. Her face was the Spanish oval, with a low, broad feminine forehead, eyebrows exquisitely penciled, and arching over eyes that I shall not attempt to describe. Her lovely bosom, half exposed as she leaned over, reminded me, as it heaved against the chemiset, of the bows of a beautiful ship, rising and sinking with the swell of the sea, now high in sight, and anon buried in a cloud of snowy spray. One hand, buried in curls, I have said, supported her head, the other, by her side, grasped the folds of her robe, beneath which peeped out a tiny foot in a way that was rather dangerous to my sane state of mind to observe.

“We had sat a few moments in silence, when Clara suddenly spoke.

“‘Come hither, señor,’ said she, ‘look out upon this beautiful landscape, and tell me whether in your boasted land there can be found one as lovely. Have you such a sky, such a moon, such waters, and graceful trees, such blue mountains—and, hark! have you such music?’

“I approached to her side and looked out. The band at the barracks had just begun their nightly serenade, and the music traveled across the bay to strike upon our ears so softly, that it sounded like strains from fairy land.

“‘They are playing an ancient march of the days of Ferdinand and Isabel,’ whispered Clara; ‘could you not guess its stately measures were pure old Castilian? Now mark the change—that is a Moorish serenade; is it not like the fitful breathings of an Eolian harp?’

“The music ceased, but it died in cadences so soft that I stood with lips apart, half in doubt whether the spirit-sound I yet heard were the effect of imagination or not. Reluctantly I was compelled to believe myself deceived, and then turned to look upon the landscape. I never remember of seeing a lovelier night. It was now nine o’clock, and the sounds of business were hushed on the harbor, but boats, filled with gay revelers, glided over the sparkling surface of the water, whose laugh and song added interest and life to the scene. Nearly opposite to us, upon the other side of the bay, were the extensive barracks, hospital, and the long line of the Marino, their white stuccoed walls glowing in the moonlight. On our left the beautiful city rose like an amphitheatre around the head of the bay; the hum of the populace, and the rumbling of wheels sounding faintly in the distance. Behind the town the blue conical peaks of the mountains melted into the sky. On our right was the roadstead and open sea, the moon’s wake thereon glittering like a street in heaven, and reaching far away to other lands. All around us grew a wilderness of palm, orange, cocoa, and magnolia trees, vocal with the thousand strange noises of a tropical night. Directly below us, but a cable length from the overhanging palms which fringed the shore, lay a heavy English corvette in the deep shade of the land; but the arms of the sentry on her forecastle glinted in the moonbeams as he paced his lonely watch, and sung out, as the bell struck twice, his accustomed long-drawn cry of ‘All’s well!’ Just beyond her, in saucy propinquity, lay a slaver, bound for the coast of Africa—a beautiful, graceful craft. Still farther out the crew of a clumsy French brig were chanting the evening hymn to the Virgin. Ships from every civilized country lay anchored, in picturesque groups, in all directions, and far down, her tall white spars standing in bold and graceful relief against the dark, gray walls of San Severino, I recognized my own beautiful craft, sitting like a swan in the water; and still farther, in the deep water of the roadstead, lay an American line-of-battle ship, her lofty sides flashing brightly in the moonlight, and her frowning batteries turned menacingly toward the old castle, telling a plain bold tale of our country’s power and glory, and making my heart proud within me that I was an American sailor.

“‘Say,’ again asked Clara, in a low, hushed voice, ‘saw you ever aught so lovely in your own land?’

“To tell the truth, I had forgotten my sweet companion for a moment. ‘I am sorry,’ said I, taking her hand, ‘very sorry, that you think the United States so unenviable a place of residence. I hope, dear lady, to persuade you to make it your home.’

“The small hand I clasped trembled in mine.

“‘Señora,’ said I, taking a long breath, and beginning a little speech which I had composed for the occasion, while sitting at the table pushing the candle-stick, ‘Señora, I have your brother’s permission to address you. I am—a—sure, indeed, convinced, that I love you—ahem—considerably. I have known you, to be sure, but a few days, but, as I said before—at least—at all events—I could be quite happy if you were my wife—you know. Señora, and if you could—a—’

“I had proceeded thus far swimmingly, except that a few of the words I had previously selected seemed, when I came to pronounce them, as extravagant, and so I had substituted others in their place, not so liable to be censured for that fault; beside, a lapse of memory had once or twice occasioned temporary delay and embarrassment; but I had got along thus far, I say, as I presumed, exceedingly well, when, oh, thunder! Donna Clara disengaged her hand, curtseyed deeply, bade me good-night, and swept haughtily out of the room. Egad! I felt as if roused out of my berth by a cold sea filling it full in the middle of my watch below. ‘Lord!’ thought I, aloud, ‘what can I have done? There I was, making love according to the chart, and before I knew it, I’m high and dry ashore. One thing is clear as a bell, she is a regular-built coquette, and all her fine looks to me are nothing but man-traps, decoys, and false lights. Yet how beautiful she is, how she has deceived me, and how much I might have loved her. Shall I try again? No, I’m d—d if I do! once is enough for me. Egad! I can take a hint without being kicked. To-morrow I’ll go aboard again, and to work like a second mate as I am; that’s decided. But—’

“Absorbed in very disagreeable reflections, I sat by the window, insensible to the charms without, which had before been so fascinating, when I was suddenly aroused by the opening of the door. I looked around, and saw Don Pedro. ‘Where’s Donna Clara?’ he asked.

“‘Gone,’ I replied, in an exceeding bad humor.

“‘What! so early? I made sure to find her here as usual.’

“‘Well,’ said I, ‘you perceive that you were mistaken, I presume’—I was very cross.

“‘Why, señor, something has gone wrong; you appear chagrined.’

“‘Oh! no, sir; never was so good-natured in my life—ha! ha! beautiful evening, Don Pedro! remarkably fine night! How pleasant the moon shines, don’t it?’

“‘Mr. Stewart,’ said Don Pedro, gravely, ‘I do not wish to press you, but you will greatly oblige me by telling me what has passed between yourself and Donna Clara this night?’

“So, rather ashamed of my petulence, I recounted my essay at love-making.

“‘Carramba!’ ejaculated Don Pedro, ‘how d—d foolish—in her, I mean. She is a wayward girl, sir, but yet I think she loves you. I tell you frankly that I ardently desire her to marry you; pardon me, then, when I say, that if you love her, do not be discouraged, but try again.’

“‘I think not,’ said I, decidedly, ‘I go on board to-morrow.’

“My usually lively and mercurial friend sighed heavily, and then drawing a chair, sat down opposite me. ‘Listen to me a moment, sir,’ said he. ‘Cast aside your mortified pride, and answer me frankly. Do you really love my sister? Would you wish to see her subjected to the alternative, either to become the wife of Don Carlos Alvarez, or else to be confined in a convent, perhaps be constrained or influenced to take the hateful veil? You alone can save her from this dreadful dilemma.’

“My Yankee cautiousness was awakened, but I replied, ‘I do love your sister, sir, and would do any thing but marry a woman who does not love me to save her from such a fate as you represent; but still, sir, I cannot perceive how that I, till lately unknown to you, can have such an influence over you and yours. Is not your own power sufficient to prevent such undesirable results?’

“I saw by the moonlight that my companion’s eyes flashed with anger, but he made a strong effort to control himself.

“‘I do not wonder,’ he said, a moment after, ‘that you are angry, Mr. Stewart, after the conduct of my madcap sister, or indeed that you deem it strange to find yourself of so much importance suddenly,’ he added, a little maliciously, ‘but I will explain the last matter to you, relying upon your honor. About two years ago, I accompanied Alvarez to Havana, upon some business relative to Clara’s estate. While returning late one evening to our hotel, we heard in a retired street the cries of a woman in distress. Midnight outrages were then very common in the city, and usually the inhabitants, if they were not themselves interested in the issue, paid very little attention to calls for assistance, and Alvarez, upon my suggesting to him to go with me to the aid of the lady making the outcry, advised me to consult my own safety by keeping clear of the fracas, but when a louder cry for help reached my ears, I could restrain myself no longer, but started for the scene of action. I soon perceived a carriage drawn up before a house which had been broken open. Two of the professional bravos were forcing a lady into this carriage, whom, by the light of the lanterns, I recognized to be an actress at the San Carlos. A gentleman in a mask stood by, apparently the commander of the expedition. I called to the ruffians to desist, but was hindered from attacking them by the gentleman, who drew his sword and kept me off, while the robbers forced the lady into the carriage and drove rapidly away. My antagonist seemed also disposed to retreat, but I was very angry and kept him engaged, until, growing angry in his turn, he seriously prepared himself to fight. He was a very expert swordsman, nevertheless in a few minutes I ran him through the body, and he instantly fell and expired. At this juncture Don Carlos stepped up, and when we removed the mask from the face of the corpse, I found to my consternation that I had killed the Count ——, an aid-de-camp of the captain-general, and a son of one of the most powerful noblemen in the mother country. Horror-struck, we fled. The next day the whole city resounded with the fame of the so-called assassination. The government offered immense rewards for the discovery of the murderer. Since that time I hold my life, fortune and honor by the feeble tenure of Don Carlos’ silence. His power over me is very great. I distrust him much. Unknown to but very few, I have a yacht lying at a little estate in a rocky nook at Point Yerikos, in complete order to sail at any moment. On board of her is a large amount of property in money and jewels, but still, alas! I should, in case of flight, be forced to leave behind the greater part of my patrimony, which is in real estate, which I dare not sell for fear of exciting Alvarez’ suspicion. I live on red-hot coals. Clara alone detains me. It is true that she might fly with me, but she would leave her large fortune behind in the hands of her devil of a guardian. Now, with what knowledge you already have of my father’s will, you can easily guess the rest. You are no stranger to me. I know your history, your family, your education, and, under the most felicitous circumstances, would be proud and happy to call you brother. Now, then, decide to try again. Clara shall not refuse you; she does not wish to do so; on the contrary, she loves you; but some of her oddness was in the ascendant to-night, and so it happened as it did. At any rate I can no longer trifle with my own safety, and have no authority or means to prevent Don Carlos from exercising unlimited power over my sister’s actions. Good-night, señor, you can strike the gong when you wish for a servant and a light. I shall have your answer in the morning.’

“Don Pedro left the room in great agitation, and soon after I retired to bed. I lay a long time thinking over the events and revelations of the evening; love and pride alternately held the mastery of my determinations. I loved Clara well and truly, and sympathized with her and her brother in their unfortunate situation, but I had been virtually refused once, and my pride revolted from accepting the hand thus forced into mine by the misfortunes of its owner. At last, as the clock struck three, I fell asleep, still undecided. The sun had first risen in the morning when I started from an uneasy slumber. I dressed myself, passed through my window to the verandah, and down to the water, where I bathed, and returning through the garden entered an arbor and stretched myself on a settee, the better to collect my thoughts.

“I had been here but a very short time when I heard voices approaching me, and upon their drawing nearer, I perceived Don Pedro and his sister engaged in earnest conversation. It was now too late to retreat, for they were approaching me by the only way I could effect it, and I was upon the point of going forth to meet them, when they paused in front of the arbor, and I heard Clara pronounce my name so musically, that I hope you will not think I did wrong, when told that I drew back, determined to listen, and thereby to obtain a hint whereupon to act. Clara leaned upon her brother’s arm, who had evidently been expostulating with her, for his voice was earnest and reproachful, and Clara’s eyes looked as if she had been crying.

“‘And yet you say,’ continued Pedro, ‘that you can love this gentleman.’

“‘Can love him!’ cried Clara passionately, ‘oh! Pedro, if you only knew how I do love him!’

“‘Why, then, in the name of all that is consistent, did you act so strangely last night? In your situation an offer from any American gentleman deserved consideration, to say the least; but Mr. Stewart, a friend and protégé of our uncle’s, a refined, educated man, a man whom you say you love. Clara, I wonder at you! What could have been the reason?’

“‘This, Pedro,’ said Clara, looking at the toe of her slipper, which was drawing figures in the gravel-walk. ‘You must know that I did it to punish him for making love so awkwardly. Now, instead of going down on his knees, as the saints know I could have done to him, the cold-blooded fellow went on as frigidly as if he had been buying a negro, and that too with a moon shining over him which should have crazed him, and talking to a girl whose heart was full of fiery love for him. Pedro, my heart was chilled, and so, to punish him, I—’

“‘Diablo!’ swore Pedro, dropping his sister’s arm, and striding off in a great rage.

“‘Oh! stay, brother!’ sobbed poor Clara; ‘indeed, I could not help it. Oh, dear!’ she continued, as Pedro vanished from her sight, ‘now he’s angry. What have I done?’ She buried her face in her hands, entered the arbor, threw herself on the settee, and began sobbing with convulsive grief. Here was a situation for an unsophisticated youth like myself. Egad! my heart bounced about in my breast like a shot adrift in the cook’s biggest copper. I approached the lady softly, and, grown wiser by experience, knelt before I took her hand. She started, screamed faintly, and endeavored to escape.

“‘Stay, stay, dearest Clara!’ cried I, detaining her, ‘I should not dare to again address you after the repulse of last night, had I not just now been an inadvertent, but delighted listener to your own sweet confession that you loved me. Let me say in return that I love you as wildly, tenderly, passionately, as if I, like you, had been born under a southern sun; that I cannot be happy without you. Forgive me for last night. It was not that my heart was cold, but I was fearful that unless I constrained myself I should be wild and extravagant. Dearest Clara, will you say to me that which you just now told Pedro?’

“Her head sunk upon my shoulder. ‘Señor,’ she murmured, ‘I do love you, and with my whole heart.’

“‘And will be my wife?’ I asked.

“‘Whenever you please.’”

Here the mate paused, and gave several very energetic puffs, and lighted a new cigar.

“I clasped the dear girl to my heart,” he resumed, “and kissed her cheeks, her lips and eyes, a thousand times, and was just beginning on the eleventh hundred, when, lo, there stood mine host in the doorway, evidently very much amused, and, considering that it was his sister with whom these liberties had been taken, extremely satisfied.

“I came immediately to the conclusion, in my own mind, to defer any farther labial demonstrations, and felt rather foolish; but Clara arranged her dress and looked defiance.

“‘I beg ten thousand pardons,’ said Don Pedro, entering, hat in hand, and bowing low, ‘but really the scene was so exquisitely fine, so much to my taste, that I could not forbear looking on awhile. Clara, dear, has Mr. Stewart discovered the way to make love à la mode? I understood you to say he did it oddly and coldly; but, by Venus! I think he does it in the most natural manner possible, and with some warmth and vigor, or else I’m no judge of kissing—and I make some pretensions to being a connoisseur.’

“‘And an amateur also,’ retorted Clara.

“‘I wont deny the soft impeachment—but, my friends, breakfast is waiting for you, if Mr. Stewart can bring his appetite to relish coffee after sipping nectar from my sweet sister’s lips.’

“We made a very happy trio that morning around the well-spread board of my friend Pedro. Just as we were rising, however, a servant brought in a note for his master. Don Pedro’s brow darkened as he read it. ‘It is from Carlos,’ said he, folding it up, ‘and informs me that he will be at home to-night, and will call for you, Clara—for it seems he has been informed of your visit here, and is determined that it shall be as short as possible. We must work quick then.’

“‘But what is to be done?’ I inquired.

“‘You need do nothing at present but keep Clara company, while I go to town to see Capt. Hopkins. We will arrange some plan.’

“Clara and I passed the morning as you may imagine; it seemed but a few minutes from Pedro’s departure for the city, till his return in company with my skipper.

“‘Ben,’ shouted the latter, seizing my hand, ‘may I be d—d but you’re a jewel—begging your pardon, Donna Clara, for swearing in your presence, which I did not notice before.’

“When Clara retired to dress for dinner, Capt. Hopkins divulged to me the plans which had been formed by him and Pedro. ‘D’ye see, Ben, my child, Don Pedro and I have arranged the matter in A No. 1 style; and if we can only work the traverse, it’ll be magnificent—and I don’t very well see why we can’t. To-day is Thursday, you know. Well, I shall hoist my last box of sugar aboard to-morrow night, and, after dark, Don Pedro is going to run a boat alongside with his plunder and valuables. Your sweetheart must go home, it appears, but before she goes you must make an arrangement with her to be at a certain window of Alvarez’ house, Pedro will tell her which, at twelve o’clock Saturday night. You and her brother will be under it ready to receive her; and when you have got the lady, you will bring her aboard the ship, which shall be ready to cut and run, I tell you; up killock, sheet home, and I’ll defy all the cutters in Havana to overhaul us with an hour’s start! Those chaps in Stockholm are almighty particular about your health, if your papers show that you left Havana after the first of June, and so, to pull the wool over their eyes, and save myself a long quarantine, I was intending to stop at Boston and get a new clearance, so it’ll be no trouble at all to set you all ashore, for Don Pedro and his sister will not wish to go to Sweden; and my second mate, I suppose, will want to get married and leave me. Now, Ben, my boy, that’s what I call a XX plan; no scratch brand about that; superfine, and no mistake, and entitled to debenture.’

“‘Excellent, indeed!’ replied I.

“‘Well, after dinner, we’ll give you time to tell your girl all about it, and to kiss her once or twice; but you must bear a hand about it, now I tell you, because we must be out of that bloody pirate’s way when he comes, and there’s a sight of work to do aboard.’

“After dinner the whole matter was again talked over and approved by all, and then the skipper and myself took our leave and went aboard.

“As Captain Hopkins had arranged, we finished our freight on Friday evening, and in the night Pedro came off to us with a boat-load of baggage, pictures, heirlooms, and money. The next day we cleared at the custom-house, and in the afternoon hove short on our anchor, loosed our sails, and made every preparation for putting to sea in a hurry. A lieutenant from the castle came off with our blacks after dark, and while he was drinking a glass of wine in the cabin, Don Pedro, most unfortunately, came on board. I heard his voice and started to intercept him; but he met me in the companion, and seizing me by the hand, exclaimed, ‘Well, Stewart, you are all ready to cut and run, I see; by this time to-morrow I hope we will be far beyond reach—’

“‘Hush! hush! for God’s sake!’ I whispered, pointing to the companion; ‘there is an officer from the castle below.’

“We walked to the sky-light and looked down.

“‘Diablo!’ muttered Pedro, with a start, ‘do you think he heard me?’

“‘No, I think not; the skipper and he did not cease conversation. The steward is so glad to get back amongst his crockery, that he was kicking up a devil of a row in the pantry; that may have drowned your voice.’

“‘If he did hear me I’m ruined. He is Don Sebastian Alvarez, a nephew of Carlos’, and dependent on him; he has watched me closely for three months. What is his errand?’

“‘He brought off our cook and steward, who have been confined in the castle.’

“‘Well, I dare say all is right; he is a lieutenant in the castle, and there is nothing strange in his being here on such business; but I’ll keep out of sight.’

“The officer soon came on deck, shook hands with Captain Hopkins, wished him a pleasant voyage, and then went down into his boat, ordering the men to pull for the castle.

“‘All right, I trust,’ cried Pedro, emerging from the round-house, ‘if he had started for the city, it would have been suspicious.’

“The skipper called the crew, who were principally Yankees, upon the quarter-deck, and in a brief speech stated the case in hand to them. ‘Now, my men,’ said he, ‘which of you will volunteer to go with Don Pedro Garcia and Mr. Stewart?’

“Every man offered his services. We chose six lusty fellows, and supplied them with pistols and cutlasses. Don Pedro gave them a doubloon a-piece, and to each of the rest of the crew a smaller sum. At eleven o’clock we descended into the boat and pushed off for the shore. The night had set in dark and rainy, with a strong breeze, almost a gale, from the south. The men rowed in silence and with vigor, but the wind was ahead for us, and when we landed at the end of the mole, behind a row of molasses-hogsheads, it wanted but a few moments of twelve. Leaving two men for boat-keepers, Don Pedro and myself, with the other four, traversed the silent streets until we stopped in a dark lane, in the rear of a large house, which appeared to front upon a more frequented street, for even at that late hour a carriage occasionally was heard.

“‘Now, hist!’ whispered Pedro, ‘listen for footsteps.’

“We strained our ears, but heard nothing but the clang of the deep-toned cathedral bell, striking the hour of twelve. A moment after a window above us opened, and a female form stepped out upon the balcony.

“‘Pedro, whispered the musical voice of Clara, ‘is that you?’

“‘Yes, yes—hush! Mr. Stewart is here, and some of his men. Are you all ready?’

“‘Yes,’ replied Clara; ‘but how am I going to descend?’

“‘Catch this line, which I will throw to you,’ said I, making a coil.

“The fair girl caught the line as handily as—as—a monkey, I suppose I must say.

“‘Now, haul away,’ I said; ‘there is a ladder bent on to the other end, which you must make fast to the balustrade.’

“‘What!’ cried Clara, quite aloud, ‘a ladder!—a real, live rope-ladder! how delightfully romantic!’

“‘Hush! hush! you lunatic!’ said Pedro, in a hoarse whisper.

“‘Oh, Pedro!’ continued his sister, ‘just think how droll it is to run away with one’s lover, and one’s brother standing by aiding and abetting! Oh, fie! I’m ashamed of you! There, now, I’ve fastened this delightful ladder—what next?’

“I ascended, and taking her in my arms, prepared to assist her to the ground.

“‘Am I not heavy?’ she asked, as she put her arms about my neck.

“My God! boys, I could have lifted twenty of her as I felt then.

“‘This is the second time, señor, that you have helped me to the ground within a week; now get me on the water, and I will thank you for all at once.’

“‘In a few moments more all danger will be behind us, dearest.’

“Clara leaned upon my arm, enveloped in a boat-cloak, while we rapidly retraced our steps to the boat, which we reached in safety, but, behold, the men whom we had left were missing. Hardly had we made ourselves sure of this unwelcome fact when a file of men, headed by the same officer who had boarded us in the evening, sprang out from behind the molasses-hogsheads. In a moment more a fierce fight had begun. I seized Clara by the waist with one arm, and drew my cutlas just in time to save my head from the sabre of Carlos Alvarez, who aimed a blow at me, crying, ‘Now, dog of a Yankee, it is my turn!’

“‘In the name of the king! in the name of the king!’ shouted the officer—but it made no difference, we fought like seamen. Clara had fainted, but I still kept my hold of her, when suddenly a ton weight seemed to have fallen on my head; my eyes seemed filled with red-hot sparks of intense brilliancy and heat; the wild scene around vanished from their sight as I sunk down stunned and insensible.