"He that is slow to anger, is better than the mighty; and he that ruleth his own spirit, than he that taketh a city."—Proverbs, xiv. 32.

The leading features of the following Tale, are founded on facts which occurred some years ago in France; and which appeared to me so striking, that I have ventured to enlarge upon the circumstances, in some measure, and now offer them in their[vi] present form to my young readers, in the hope that they may serve as a warning to such as are in the habit of indulging in the dangerous and sinful passions of anger and hatred, which are alike destructive in their effects, both to themselves and their fellow-creatures.

Anger is the first step towards murder: it was through an indulgence in it, that the first blood was shed upon the earth. We read, in the fourth chapter of Genesis, that "Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell.[vii] And Cain talked with Abel his brother: and it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up and slew his brother."

Who knows, when he gives way to anger, where its effects will stop? For this cause it is written, "Be ye slow to speak, slow to wrath." And St. Paul commands us, saying, "Let not the sun go down upon your wroth." Our Saviour also has declared, that "if we forgive not, from our hearts, every one his trespasses, neither will our[viii] heavenly Father forgive us our trespasses."

Therefore, let me entreat you, my young friends, not to let angry passions have place in your hearts; but let them be the seat of peace, and love, and good-will towards your fellow-creatures. So shall you find favour both with God and man.

Just before the commencement of the harvest of the year 1788, several fertile and beautiful provinces of northern France were visited by the most terrible tempest of thunder, hail, rain, and wind, that ever was recorded in the annals of history [1].

The once fruitful land was, by its devastating effects, converted into a desolate and barren wilderness. Fields of half-ripened corn were beaten to[3] the earth; the vines broken and utterly destroyed: even the vegetable-garden of the humble peasant shared the same fate, and was involved in[4] one general ruin. A dreadful scarcity was the result. Bread rose to an unheard-of price; the farmers were ruined by the entire failure of their crops; and the peasants were unemployed, and reduced to the greatest distress. One general voice of woe and lamentation was heard throughout the land, "because the harvest of the field was perished."

But God, who in his wisdom sometimes sees it necessary to afflict his people, that they may acknowledge the greatness of his power, and learn to know that it is but lost labour for them to till the ground and sow the seed, unless the Lord give the increase, and send down his fertilizing showers to quicken its growth; that, "unless the Lord build the city, their labour is but lost that build it;" and[5] "unless the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain:" since it is by his favour alone "we live, and move, and have our being."

Yet he heareth the cries of the poor and destitute, when they call unto him in the time of dearth; and raises up friends to those who languish in poverty and distress.

In this time of great scarcity, God moved the hearts of the inhabitants of the distant provinces (that had been so fortunate as to escape the effects of the tempest) to commiserate the sufferings of those who had lost their all; and many liberal subscriptions were raised for their relief. Those persons who were possessed of much wealth, and who resided in the immediate neighbourhood of the sufferers, threw[6] open their granaries and stores of corn, and sold out the grain at a very low price, to such as could purchase it; and to the very poor, who were in a starving condition, they commissioned a certain portion of bread to be allotted to each family, according to their wants.

Among those noblemen who were the most remarked for their generosity to their poor neighbours, there was none showed a more benevolent spirit than the seigneur of the little village of L—— in the Pontoise district. This worthy man left no means untried, by which he could lessen the distresses of his people. He appointed trusty persons of the village to take account of those who were most in need of assistance, and placed in their hands certain sums of money,[7] with which they were to procure food and raiment for the sufferers.

Among those whom he deputed to be his almoners, was the curé, M. de Santonne, a worthy shepherd of the flock of his master Jesus Christ, whose minister he was, and whose example and precepts he humbly endeavoured to follow.

Three times a week did the peasants and their families assemble in the court-yard in front of the curé's dwelling, to receive their lord's donation of bread; and it was a beautiful sight to see the venerable man dispensing the bread to his flock, accompanied by his blessing and an exhortation to them to return thanks to God, who had not forsaken them utterly in the time of need; and bidding them, at the same time, remember[8] their benefactor in their prayers, who had so liberally provided food for their relief. Though this was insufficient for supplying all their wants, it was still a great help to them, as, without some such aid, many must have perished with hunger and cold; for, to add to their misfortunes, the winter set in with more than its usual rigour.

One morning, when the curé was in the court-yard, distributing the usual supply of bread to his distressed parishioners, a youth of singularly wretched appearance presented himself before his gate, and pushing aside the crowd, forced his way towards the spot where the minister stood, saying, in hurried accents, "Give me bread, or I starve!" Surprised at the abrupt manner in which this request was made, the curé looked up to examine[9] the person who had thus unceremoniously made known his wants; but surprise was soon changed to feelings of deepest commiseration, when he beheld the famished looks and wasted form of the youth, who appeared to be scarcely seventeen years of age. His cheeks were of a ghastly paleness: his eyes hollow, and deeply sunk beneath his brows, over which hung heavy masses of dark hair, which added a yet greater expression of misery and famine to the countenance of the wretched being who now stood before him with extended hand, and eyes so eagerly fixed on the only remaining loaf which the curé had to bestow, as though he feared it would be denied him in his dire necessity.

The youth was a stranger to the curé, who was intimately acquainted[10] with all the inhabitants of the village, both old and young. His curiosity was a little excited, to know who his new claimant for bread might be; and as he considered himself in duty bound to render a proper account of the manner in which his lord's charity was bestowed, and upon whom, he asked the youth whence he came.

"You are a stranger in this village," he said, addressing himself to the young man: "What is your name?"

"Philippe," was the brief reply.

"You have another name besides Philippe?"

"It is of no moment," he answered, with an impatient movement, as if unwilling to remain longer to be questioned.[11]

"Where are your parents?" interrogated the curé.

"They are dead: I have no parents."

"Are you then alone?"

In great agitation he replied: "I have a brother, a sick brother, who is dying for want of food. And oh! Sir," he added, wringing his hands, while his voice was rendered almost inarticulate through excessive emotion, "if you will not give me the bread for myself, yet let me have a morsel of it for my brother, who is dying, I fear, with hunger."

Here the unfortunate Philippe paused, and, covering his face with his hands, wept bitterly for some minutes.

The benevolent heart of the curé was touched by the sight of his an[12]guish. "Go, my child," he said: "take this bread to your brother; and may God restore him to you. But stay," he added, "I will myself accompany you. Perhaps I may be able to administer consolation to you yet further, by speaking the word of peace to your sick brother."

Philippe did not hear the last words of the curé. With eager hand he had seized the loaf of bread, and murmuring his thanks in broken tones, disappeared from among the crowd.

The only intelligence that could be obtained respecting this singular young man was, that a few days previous to the present time, he had been seen to enter the village, supporting a pale, emaciated youth, apparently somewhat younger than himself; but evidently suffering under the effects[13] of famine and disease. They were accompanied by a Newfoundland dog, of extraordinary size, on whom Philippe, from time to time, bestowed many marks of affection.

"They applied to my wife and I, for food and shelter," said one of the peasants, who stood near at the time the curé made the enquiry concerning the stranger; "but we could not think of taking the bread out of our children's mouths, who had not sufficient, poor rogues, to satisfy their cravings, to bestow it on strangers; and I made free to ask them, if they were really so much distressed, how they could afford to keep the great dog they had with them? But they could not say a word to that, and walked away."[14]

"Surely, Jacques," said the curé, in a tone of more than usual gravity, "you have not, in this matter, acted according to the precepts which are taught in the Scriptures, to do unto others as you would be done unto yourself. What saith the apostle of our Lord? 'He that seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him?' If you had spared a morsel of food from your own necessity, for the relief of a suffering fellow-creature, think you not that God would have returned it four-fold, into your bosom? since he that giveth to the poor and needy, blessed is he. Surely, my friends, if ye turn away your faces from the poor man, and from him that crieth unto you in his trouble, shall not the Lord also turn[15] away his face from you, and mock when your hour of distress is at hand?"

There was an expression of severe, yet sorrowful reproof, in the look with which the worthy pastor surveyed his flock, as he pronounced these words, that abashed those who had so cruelly disregarded the sufferings of the unfortunate Philippe and his brother; and, ashamed to meet the reproachful glance of their justly offended pastor, the crowd dispersed, and silently withdrew to their several homes.

Desirous of affording some relief to the unfortunate and destitute strangers, the curé made every possible enquiry after them among the villagers; but no one seemed to be acquainted with their place of abode. Neither had Philippe been seen in the[16] street of the village, since he first entered it. The curé thought it possible he had left the place; but, after a few days, he again saw him enter the court-yard, accompanied by the very dog which had been described by the peasants. The animal, like his master, appeared to be in a starving condition: hunger and misery were so strongly depicted on both their faces, that the compassionate heart of the curé was touched with feelings of pity for their sufferings.

On perceiving the curé, Philippe hastily approached him, and besought a fresh supply of bread. "That which you gave us is eaten, and now we perish with hunger," he said, in a hoarse and broken voice.

The curate regarded the petitioner with a searching glance. There was[17] a fierceness in his look and manner, which convinced the curé he had still to learn to conquer a proud heart, which had not yet been tamed by the sweet uses of adversity; since there was a tone of command, rather than of entreaty, in the manner in which he made his request. The curé did not hesitate to notice this to him.

Philippe cast his eyes on the ground, sad and dejected. "Alas!" he said, sighing heavily, "I did not mean to offend you, Sir; but I am not accustomed to solicit charity; and, believe me, it is only the severest distress that could have forced me to do so now. But it is not for myself I ask relief: I know I am not worthy of it; but I cannot see those I love, and to whom I am bound by the tenderest ties,[18] die, because I am too proud to ask it for them!"

"You told me you had no parents; and spoke but of one brother. Have you then a sister?"

Philippe replied in the negative, but with evident embarrassment.

"Of whom then did you speak: your words implied more than one belonging to you?"

Philippe was silent. He bent his head down, to meet the caresses of the shaggy animal that stood beside him; his pallid cheek, for an instant, suffused with a hectic colour.

The curé, resolving to learn the truth, repeated his question. "Perhaps you alluded to a friend."

"Yes, it was of the most faithful of friends I spoke," replied Philippe, in hurried accents.[19]

"Where is that friend," asked the curé.

"Here," answered Philippe, greatly agitated, throwing his arms round the neck of the noble animal, and bathing his head with his gushing tears.

The curé was touched by the singular affection which this strange young man evinced towards his mute companion; yet he thought it was not right, in a time of such unparalleled distress and scarcity, to bestow that bread, which was given by his master to satisfy the hungry peasants, to support the life of a useless animal, when so many human beings were perishing from want of food.

"It is not right," he said at length, "to take the children's bread and cast it to the dogs. You cannot af[20]ford to keep that creature; and if you suffer him to provide for himself among the neighbouring flocks, you are guilty of a great sin against your fellow-creatures; especially at a time when the whole land groans beneath the hand of famine and poverty. You must resolve to part from your dog."

"It is impossible, Sir," replied Philippe, resolutely. "I cannot, will not take his life. Ask it not of me," he continued, while the tears chased each other rapidly down his wan cheek. "You do not know the gratitude I owe to this animal: a debt I never can repay; and while I have life, I will not part from my dog, but he shall share with me the last morsel of food I have."

The mind of the good curé was[21] troubled how to act. He felt he had no right to appropriate a portion of the bread, designed by the noble donor to supply the wants of his starving people, to feed an animal; yet, compassion for the unfortunate youth before him, urged him to give the bread.

The curé was poor, and he had been a considerable sufferer in the general misfortunes which had befallen the inhabitants of the district; but he had a feeling and benevolent heart, ever awake to the woes of his fellow-creatures. He felt a singular degree of interest excited by the strong affection which existed between Philippe and his dog; but his questions as to the nature of those ties of obligation which Philippe had acknowledged to subsist between him and his brute[22] friend, seemed only to awaken recollections of the most painful nature in the young stranger.

He was yet deliberating as to what course he should pursue, when Philippe again implored him to give him a loaf, that he might hasten back to his brother, since he would be uneasy at his absence. "He takes no other nourishment than a small piece of bread, soaked in water. It is all I have to give him. But he will soon cease to want even that," he added, in a tremulous voice, "and then I shall be left alone in the world, with no one to love me, or care what becomes of me—but you, my poor faithful Achille." He then looked down, with eyes filled with tears, on his companion, and was silent.

"My child, you will not be for[23]gotten," returned the curé, looking upwards: "there is yet one friend to protect you left; even He who is the father of the fatherless, and the friend of all such as are left destitute. He heareth the deep sighing of the captive, from the walls of his prison: he healeth the woes of the widow, and stilleth the cries of the orphan: he smooths the pillow of sickness, and speaks peace to the broken and contrite heart. He will not leave thee utterly destitute. Believest thou this, my son?"

"Yes!" replied Philippe, with much earnestness; "for I have felt the goodness and mercy of God deeply in my heart. If he has chastened me, I submit to his chastisements: for to me they have been sure signs of his mercy;[24] and I am content to say, 'O Lord, thy will be done!'"

The curé commended him for his pious resignation to the will of God. He then gave him the bread he requested, and added to it such food as he thought most necessary for his present wants. "This," he said, "I can give you: it is my own. Do with it as is most convenient to you," putting into his hand a small piece of silver.

The eyes of Philippe spoke the gratitude of his heart more eloquently than words could have done. "Ah! Sir," he said, "I am not worthy of this goodness. I am an unhappy, erring creature; not deserving of your notice. Did you know half my faults, you would flee from me, as a wretch to be hated and despised."

"It would ill beseem my office, as[25] a minister of that Saviour who came down upon earth to save sinners, and to teach the forgiveness of sins, to turn away from a repentant child, who acknowledges himself to have been in error," replied the curé. "Christ came not to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance. I know, my son, that there is none that doeth good, and sinneth not; for the Lord himself has declared, that the imagination of man's heart is evil from his youth upwards. But what have you done?" added the worthy minister, observing Philippe's excessive agitation, with mingled sensations of compassion and curiosity.

"What sin have you committed, that weighs so heavily on your mind, and occasions these tears and sighs?"[26]

"Spare the recital of my past errors," replied Philippe, greatly moved. "I cannot tell you my sad story now; but believe me, Sir, that if I have sinned, I have repented, most deeply, of my faults. I will tell you all, one day, but not now."

The curé was touched by his sorrow, and kindly endeavoured to soothe him. "Come," he said, "show me where you live. I will walk with you, and visit your sick brother. Possibly I may be able to render him some consolation."

Philippe thankfully accepted the offered kindness. "We live in a little cottage," he said, "just beyond the village. You may see the chimneys below the hill. It is the dwelling of a poor old widow woman, who took compassion on our desolate condition,[27] and kindly afforded us a shelter from the piercing cold. She left us, a few days since, to visit a daughter who is ill, at a distant town; but before her departure, she shared her last piece of bread with us, and charged me to apply to you for more, when that was done. It was not, however, till forced to do so by the agonies of hunger, that I ventured to solicit charity for myself and my dying brother."

During their walk to the cottage, Philippe became more composed, and informed his new friend a few particulars respecting his parentage and former situation in life. His father, he said, had for many years of his life cultivated a small farm, near a village in the district of the isle of[28] France[2]. His own mother died when he had just attained his fourteenth year; and not long after her decease, his father married again, a widow with one son, a youth about six months younger than himself. His father's second marriage was a source of great unhappiness to him, as he was greatly attached to the memory of his own mother, who had ever been the tenderest of parents; but he did not like his step-mother, who was of an imperious temper, rude, and coarse in her manners; and one who dissipated his father's property, by her extravagance and want of care. "I was jealous of her son," continued Philippe, "and treated [29]him with the utmost cruelty; persecuting my unfortunate, unoffending step-brother in every possible way. He was of a meek and saint-like disposition, and strove, by every means in his power, to win my regard. But I saw his attentions with a jealous eye, and, like Cain, I hated my brother, because my heart was evil and his was good. But if my crimes have been great, so has been my repentance, and my punishment also; yet not more than I merited."

He then informed the curé, that the village near which his father's farm was situated, had been almost entirely destroyed by the fury of the late dreadful tempest; that his father and his step-mother were both buried beneath the ruins of their dwelling,[30] which was struck by the lightning; that every thing they possessed was utterly destroyed by the storm: corn-fields, orchards, cattle, implements of husbandry, were all involved in the general ruin. And in one hour they found themselves destitute orphans, without a home or any means of subsistence.

"Alas! poor children," said the curate, touched by the picture of misery which Philippe had drawn, "yours has been a lot of hardship. But God does all things for the best. Let us not presume to question his goodness, or his wisdom; for his ways are past finding out, neither can we search into them."

They were now within a few paces of the cottage-door, which the curé[31] had not noticed till the joyful bark of Achille caused him to look up.

Philippe chid his favourite gently. "Hist! hist! Achille," he said: "your noisy barking will disturb your master. Then softly lifting the latch, he entered the cottage, or rather hovel; as it consisted but of one wretched apartment, through whose mud-walls the winter blast found many entrances. On a rude sort of crib, at the furthermost corner of the room, barely covered by the scanty remains of an old woollen rug, lay a youth, apparently about sixteen years of age, whose death-like paleness, and features sharpened by famine and disease, betokened plainly to those who looked upon him, that he was fast withdrawing from a world of pain[32] and sorrow, to the friendly refuge of an early grave.

A faint smile broke over his languid countenance, and for an instant lit up his hollow eye, as Philippe drew near the crib. He made an effort to raise himself, to meet the extended hand of his step-brother; but the exertion was followed by such convulsive fits of coughing, that they seemed to threaten the poor sufferer with immediate suffocation.

The paroxysms ceased at length, and he sunk back on the shoulder of Philippe, in a state of exhaustion, which nearly resembled the stupor of death.

The fierce and impatient expression which had so strongly marked the countenance of Philippe, when he first presented himself at the curé's gate,[33] was now softened into one of tenderness, mingled with the deepest woe, as he gazed, in silent anguish, on the inanimate form of Antoine.

The curé did not look on this scene unmoved. He had a kindly heart, ever ready to sympathize in the sorrows of his fellow-creatures—"to weep with those who wept, and to rejoice with those who did rejoice."

He might truly be called a faithful shepherd of the flock; for none ever appealed to him in vain. To the hungry he gave his bread; (if, indeed, he had bread to give;) and to the broken-hearted sinner he administered the words of peace and consolation, pouring into their wounds that balm which descendeth from above, and is indeed above all price. Yet, after all these things were done, the curé would[34] meekly declare he was yet but an unprofitable servant.

Such was the pastor of the village, who now stood by the bed of sickness, with folded hands, and in silent prayer beseeching the Lord to look down in pity upon his suffering children, and so to sanctify his fatherly correction to them, that they might take his visitation with humility, and be led, by his grace, into the path that leadeth unto everlasting life.

With the kindness of a parent he strove to soothe the grief of Philippe; but it was not till the eyes of Antoine slowly re-opened, that he would be convinced that they had not, indeed, closed on him for ever.

It was evident to the curé that Antoine's days, nay, almost his hours, were numbered; and that he would[35] shortly cease to be, and to suffer: since the laboured manner in which he drew his breath, showed that an imposthume had formed on the lungs, which would most likely terminate his sufferings very soon. There was a patient look of endurance in the poor youth, that bespoke the meek and pious resignation of a Christian spirit. He seemed to struggle to conceal his bodily pain as much as possible, that he might not increase the grief of Philippe, who watched, with the utmost anxiety, the varying expression of his countenance, as, from time to time, Antoine raised his eyes to his face, and in terms of affectionate regard bade him take comfort.

"Weep not, Philippe," he said, kindly pressing his hand. "God will not leave you comfortless: he will[36] raise up a friend, to supply my place when I am gone hence."

Philippe's tears fell fast over the pale brow over which he leant, while Antoine, raising himself with all the energy his weak frame was capable of exerting, continued, in an earnest tone: "Grieve not for me, my brother; for my earthly sufferings will soon be over. I shall go hence to a place of rest, where there comes no sorrow to disturb my repose; where death no more can approach me, to terrify me; where I shall awake from the cold and cheerless winter, to an eternal spring and summer, which will know no change, and no decay of brightness. I look through the clouds of suffering which now encompass me, to a life of immortality. Remember, my brother, that 'whom the Lord[37] loveth he chasteneth.' We have been sorely smitten by the rod of affliction: yet it has been in mercy; since, 'before we were troubled we went astray.'"

"I acknowledge my error," replied Philippe, meekly; "and it is not for a sinner like myself to repine at His dispensations. Yet, how shall I find comfort when you are taken from me: you, who have been to me more than a brother—a friend, a counsellor, when I did not deserve kindness at your hands? Who will be my friend, when you are gone?"

"The same who has watched over you from your youth upwards," replied Antoine, impressively. "He will be your friend and your counsellor, while you continue to walk[38] steadfastly in his ways. Forsake him not, my brother; for his ways are ways of pleasantness, and all his paths are peace."

The curé was surprised to find so excellent a spirit in one so young, and he almost marvelled whence he had attained so much wisdom. But Antoine's god-mother had been a lady of great learning and piety, and she had brought him up and educated him, till he had attained his fourteenth year. At that time, when she was considering about sending him to college, to take orders for the church, she was attacked by a brain-fever, which terminated her life in the course of three days. She had not made a provision for her godchild, by will; she had relations, who claimed all her property; and Antoine was[39] forced to return to his mother, who was then a widow, in indifferent circumstances. But hard as the change was to him, he felt it was his duty to submit to the reverse with patience; and he was never heard to murmur, but conformed to his lot as though he had known no other.

The curé felt a considerable degree of interest excited by the strong attachment that appeared to subsist between the step-brothers; which was the more surprising, since Philippe had given him to understand that formerly there had been a division between them. It was evident then, it had been the result of some circumstance, which had occurred to change sentiments of hatred and envy into gratitude and affection; but what had wrought this change,[40] Philippe had expressed an unwillingness to declare; and the curé forbore to question him on the subject. For the present, he contented himself with supplying their immediate wants, and endeavouring to soften the hardness of their condition by his soothing words; and promising to see them again as soon as possible, he left the cottage.

For several days the worthy pastor was unable to visit the brothers, owing to the snow, which had continued to fall without intermission. Meantime, he had not been entirely unmindful of their comforts, but had sent a blanket and a few other necessaries for the sick Antoine.

A cessation from the falling of the snow was embraced by the curé, for visiting his poor parishioners in the[41] village; and having satisfied their wants, as far as his abilities and means permitted, he turned his steps towards the snow-covered path that led to the widow's dwelling.

It was not without great difficulty and some danger, that the good man made his way through the snow-wreaths that choked the untrodden path; but, urged by feelings of active benevolence, which induced him to overcome every selfish consideration of personal comfort, he proceeded onwards.

The wintry sun, already verging towards his decline, shed a dim and yellow light on the snowy landscape, tinging with stormy brightness the white edges of the ridge of snow-clouds, which lay piled above each[42] other like distant mountains, at the verge of the horizon. The wind whistled drearily among the trees, which creaked beneath the weight of their frozen burdens. Not a bird was to be seen flitting across the fields: not even a hare or a rabbit crossed the path, as the curé proceeded in his walk towards the cottage. It seemed as if nature herself slept in this frozen solitude.

The curé lingered on the threshold of the cottage-door, lest his sudden entrance should disturb its inmates. A deep silence reigned within, which was at length broken by the low whining of Achille. This sound was followed by a deep, stifled sob: it spoke the inward anguish of heart-felt grief, and fell on the ears of the[43] curé as though it were the knell of death.

With trembling hands he lifted the latch, and entered the house of woe and mourning. Stretched on his crib, with closed eyes and pallid brow, lay the body of Antoine. One damp relaxed hand lay over his breast: the other hung, in lifeless languor, over the side of the crib, wet with a brother's tears. A peaceful smile seemed to hover upon the half-closed lip; and, from the serene and placid expression of the face, you would almost have been tempted to exclaim, "Weep not: he is not dead, but sleepeth."

At the side of the bed, with his face concealed in the foldings of the covering, knelt Philippe. His grief was neither loud nor violent: it spoke only in deep sighs, and convulsive[44] starts of agony, which, from time to time, shook his frame, and told the inward anguish of his soul.

Death had, indeed, rendered his heart desolate: it had robbed him of the only tie which seemed to render life supportable. No wonder that he felt it deeply. Was he the only mourner there, think you? No: there was one mute, faithful friend, whose wistful eye continued to regard the dead face of his master with woeful curiosity; whose restless and impatient moanings broke upon the stillness of the scene with melancholy tones.

Whoever entered the chamber of death unawed, or without asking his own heart, "What is our life? It is even as the grass of the field, which in the morning is green; but in the[45] evening it is cut down, dried up, and withered."

We gaze on the inanimate clay before us, and wonder within ourselves where is that principle of life which vivified the whole; which breathed on the lips, looked through the eyes, and spoke the feelings of the mind in every expressive feature? The casket is there, but the jewel it once contained is gone. While we continue to gaze on the lifeless form of the dead, a strange chillness creeps through our veins. It seems, indeed, no longer the being we once loved, but only the silent memorial of what once was dear to us. It is, then, the soul that animated that body which was the object of our affection; since our grief remains undiminished, although the mortal part is yet before our eyes.[46] But we long for the communion of that invisible spirit which we were wont to converse with; which has withdrawn itself from its earthly tenement, and returned to the presence of the God who gave it.

The closing shades of evening cast a solemn twilight through the narrow casement of the room, rendering the scene of death yet more impressive; and the hollow moaning of the wind, sweeping in gusts through the leafless branches of the snow-covered trees, that stretched their broad arms over the roof of the cottage, seemed to be sighing in mournful unison with the sad inmates of the chamber of death.

With pious hand did the good curate perform the last offices for the dead, and strive to mitigate the grief that wrung the heart of the poor[47] mourner; bidding him raise his thoughts above the lifeless remains of what had once been his brother; to follow the spirit, to those realms of light and life whither it was gone, to inherit a crown of everlasting brightness, whose glory fadeth not away.

That long night was spent by the curé in deep and fervent prayer; nor did the worthy man leave Philippe, until he had acknowledged that he no longer sorrowed "as one without hope."

The spot chosen by the curé for the last resting-place for Antoine, was at the foot of a lofty ash-tree, which grew on the edge of a steep and broken acclivity in the village church-yard, over the side of which it bent its drooping boughs.

In spring and summer this was a[48] lovely spot, adorned with the greenest swards, and flowers of various hues. The ground was unbroken, save by one solitary mound, which had been raised over a soldier's widow and her orphan child. The widow, after many years of absence, had sought her native village to die there, and had been, by her own particular request, buried beneath the great tree, which had been the scene of her childish sports. A wooden tablet at the head of the grave, green with moss and lichens, served to recall to the memory of the villagers, who slept beneath the sod.

The ground was covered deeply with snow, when the funeral procession entered the church-yard; and the still yet heavy shower of snow that covered the coffin as it was lowered[49] into the grave, seemed to spread itself, like a funeral shroud, over the last relics of the dead.

The dejected spirit of Philippe seemed to catch the feeling of holy inspiration with which the curé, in solemn tones, pronounced those words of the suffering prophet: "I know that my redeemer liveth." He raised his eyes towards heaven, radiated with an expression of faith and hope, which told that the spirit of peace was there, hallowing the grief of the mourner, and turning his sorrows into joy.

When the burial rites were concluded, and the peasants who had borne the bier had retired from the church-yard, the curé approached the spot where Philippe stood looking on the little heap of earth, which was[50] being piled above him whom his soul still yearned after with a brother's affection. "Come," said the good man, drawing Philippe's arm through his own, "you shall accompany me to my home: from henceforth it shall be your own; at least, while you stand in need of one."

"Alas! Sir," said Philippe, "you are not, perhaps, aware of the many faults, I may say the many crimes, which have stained the character of him on whom you would place your friendship. I am unworthy of your regard; nor will I presume to accept your proffered kindness, till I have first laid open to you the sins and follies of my youth."

That evening, while he was seated before a cheerful fire in the curé's study, with his faithful companion[51] Achille stretched at his feet, Philippe related to his benefactor the history of his past life.

I have promised to hide nothing from you, Sir, (said Philippe;) and I will now endeavour to give you a faithful account of my life; although the recital of past scenes of guilt, cannot but awaken in me feelings of a most painful nature.

I was, as I believe I before stated, an only child; and, consequently, rather more indulged by my parents than was altogether good for me;[52] especially by my father, who would not suffer my mother to contradict or correct me for any of my faults. For the first few years of my childhood, he lavished on me the most unbounded marks of affection; but, by the time I had reached my eighth year, I was become so wilful and wayward in my temper, that his regard for me began greatly to diminish, and he even treated me with neglect and unkindness, which change I felt very keenly.

I say this not with the design of extenuating my fault; but to show the ill effect which injudicious partiality is apt to produce, on the character and temper of a child.

My mother, whose affection for me was governed by principles of religion and virtue, far from casting me off when my faults began to show them[53]selves, endeavoured, by every means in her power, to improve my mind, and to render me good and amiable; and strove, with unremitting care, to check those dangerous bursts of passion, which I was apt to give way to on the slightest possible occasions, and to soften that proud and tyrannical spirit which arose from the high opinion I entertained of my own merits.

Had I constantly kept in view those excellent lessons of virtue and forbearance, which that dear mother tried to inculcate in me, I had been spared hours of the bitterest remorse and misery in my after life.

I had just attained my fourteenth year when I lost my beloved mother, whose kindness and love for her erring child will ever claim my most grateful[54] remembrance. From her death, I seem to date all my sorrows; for if I had found the task of curbing my impetuous temper a difficult matter while I was aided by her advice, and encouraged to persevere by her approbation, no wonder, when she was no longer with me to point out my faults, that I suffered them daily to gain strength and accumulate, till at length I became all that she had warned me not to be!

My faults at this period of my life were confined, principally, to a hasty and imperious temper, accompanied by a considerable share of vanity, and a desire of bettering my condition; and the foolish ambition of becoming, in the course of time, a rich man, and being able, with the fruits of my own industry, to purchase the land which[55] we then rented. Encouraged by this idea, I worked with unremitting industry on the farm, which my father and I contrived to cultivate between us, with only a little additional help in busy times; such as harvest, and the gathering in of our fruits in the autumn.

I was of a selfish and covetous disposition; and to this latter trait I owe many of the errors of my life; though I may at the same time declare, that I do not believe any temptation would have induced me to commit a breach of honesty, in any shape whatever.

Our little stock began to increase and flourish; and I was beginning to flatter myself with hopes of future independence and prosperity, when a change took place in our domestic establishment, which overturned all[56] my expectations, and crushed all my fancied prospects.

Before I proceed any further, it is necessary I should tell you, that my father and I agreed but in one point, and that was, endeavouring to make the most of our little occupation; but on no other subjects were our minds in unison. If we conversed on any topic, our discussion ended in disputes and angry contradiction of each other's opinion. My father's temper was uncertain, sarcastic, and morose: mine, quick, irritable, revengeful, and impatient of the least degree of contradiction. I am aware that my duty to my parent should have obliged me to yield to my father; but if his commands and his opinions did not meet with my ideas, I excused myself from the[57] accusation of disobedience, on the plea of injustice on the part of my father. At length he ceased to hold any conversation with me; but often absented himself from home of an evening, leaving me to amuse myself as I pleased. It did not occur to me, that my unamiable conduct was one of the causes which made home distasteful to my father; but I imagined it was on account of the loneliness of our fire-side, which had been wont to be so cheerful, when enlivened by the society of my dear mother; and I felt her loss more keenly than ever.

One evening, my father had not gone out as usual to the village, but sat looking on the fire, and appeared restless and uneasy. I ventured to exchange a few words with him. He answered me at random, as though[58] he had not heard me. "You used to be much happier, father!" I said, "when my mother was alive. How much we seem to miss her from the fire-side; and we shall be yet more lonely when the evenings begin to lengthen: she used to make every thing so comfortable and lively in the house."

"You are right, boy," said my father, rising, and reaching down his hat as he spoke. "Home is not a home, without a mistress to enliven it. I am very lonely and dull here; but I will soon make a change," he added, laying his finger on the latch of the door, with an emphasis that made me start. With these words he left the house; while I, greatly surprised by his manner, passed the rest of the night in forming conjectures as[59] to the real meaning I was to affix to these words. But I was not suffered to remain long in suspense.

The following morning, while busily employed in the harvest-field with my reaping-hook, my ears were on a sudden saluted by the ringing of the village-bells, whose light and lively chime did not fail to excite in me feelings of pleasure and curiosity. There is a natural inclination in young people to enjoy sweet sounds, especially those that are connected with ideas of mirth and gaiety.

I left the half-bound sheaf of corn on the ground, and flinging aside my reaping-hook, hastened towards the brow of the hill which overlooked the road, where I beheld a gay procession advancing from the village. Thinking it was the bridal of one of[60] the village belles, and desirous of seeing the bride and bridegroom, I bent my way through the rustling corn, and gained the road just as the party came up. But how shall I describe to you my feelings of surprise, rage, and indignation, when, in the bridegroom, I recognized my own father; and in the bride, who leant on his arm, gaily attired and in exuberant spirits, I beheld the widow of the late tax-gatherer of the village.

She was a person against whom I had always entertained a singular degree of aversion, for having repeatedly caused me to be punished at school, by sending complaints to my school-master, when I indulged in any childish follies, which she imagined were intended to annoy her.

By her side walked her son, whose[61] pale and pensive countenance seemed to accord but ill with the gaiety that surrounded him. Antoine had even been to me an object of dislike and envy; because he had been singled out by the lady of the chateau, Madame D'Estelle, as a favourite, and considered almost in the light of an adopted child. He went to the same school as I did, and so far excelled me in the progress he made in learning, that, though nearly six months younger than myself, he was always above me in the class, and consequently held up to me as a pattern of excellence worthy to be copied. I had long beheld him with secret envy; and even felt a degree of satisfaction when the unexpected death of his benefactress robbed him of those expectations which he had looked for[62]ward to, and obliged him to return to his own humble home, and labour to help support himself and his mother.

And now, as if willed by fate, this Antoine was destined to become my future companion—to share in my labours, and to supplant me in my rights.

Rage, jealousy, and every other evil passion assailed me at the sight of my father's new wife and her son; and when commanded by my father to approach and pay my duty to my future mother, and bid her and my new brother welcome to our home, I angrily refused to obey, declaring, with great vehemence, nothing should ever force me to acknowledge a stranger for my mother, nor the son of a stranger as my brother; at the same time, reproaching my father for having so[63] soon forgotten the memory of my beloved mother.

In a voice terrible with anger, my father bade me begone from his presence, until I had learned what was due to the authority of a parent. I obeyed, and left him in a state of mind which I cannot now reflect upon without feelings of shame and remorse.

So great was my indignation, that at first I resolved to quit my home for ever, and seek my livelihood elsewhere in some distant province; where I should be far away from father, step-mother, and that step-brother whose name had always been hateful to me, but doubly so now he was to be an inmate of the same dwelling, and thrust, as it were, upon my society.

These thoughts occupied my mind, while tears of rage fell from my eyes,[64] and rolled, in quick succession, down my burning cheeks. Tired and exhausted by my own miserable feelings, and sick at heart, I flung myself on the grass, beneath a clump of maple-trees, which grew on the banks of the stream that formed a boundary to one part of my father's land. In this situation I was found by a person who had been accustomed to assist me, at times, in the labours of the farm, when we had occasion for any extra help; but my father, having had cause for anger, had discharged him, greatly to his indignation.

He approached me cautiously, and in soothing tones began to condole with me on the hardness of my lot. At first I turned an impatient and unwilling ear to his words; but he knew well how to attract my atten[65]tion, and soon began to praise my conduct, as the most industrious and virtuous youth in the village; declaring that few fathers were blessed with so promising a son. I listened to his flattery, and believed myself to be all he declared I was. His artful commendations of myself had the effect of raising my anger yet higher against my father. And I avowed to this man my intention of leaving my home for ever.

He laughed at my resolution. "What!" said he, "will you leave your birth-right to another, and the substance you have laboured so hard to obtain, to be enjoyed by strangers, who will rejoice in your absence, that they may reap the fruits of your industry unchecked?"[66]

"You are right," I cried, starting from the ground, anger flashing from my eyes as I spoke. "I will not go. This woman and her son shall not drive me from my home, to become a wretched wanderer and outcast, oppressed by want and misery, while they revel in plenty: at least, their mirth shall be embittered by my presence." With a spirit of revengeful exultation in my heart, I hastily strode towards my home; and leaping the enclosure that separated me from the garden, I entered the house. My sudden entrance caused an interruption to the general hilarity of the guests. They were then about to sit down to supper, for it was getting late. Although I had not tasted a morsel of food since an early hour in the morning, I refused to partake of[67] the supper that was prepared, and withdrew to a distant part of the room, regarding, with gloomy aspect, the scene before me.

You, Sir, (continued Philippe, addressing himself to the curé,) who never have allowed such evil passions to take possession of your breast, can scarcely form an idea of the dreadful state of my mind. Few, perhaps, there are, who would have suffered a circumstance of this kind to affect them as it did me. But in this marriage I beheld all my hopes of future advantage entirely crushed, and my place usurped by strangers, to whose caprices I must, in some measure, be subjected; and on whose will, many of my future comforts might depend.

And when I contrasted the coarse manners and person of my step[68]-mother, with the remembrance of my own mother, who was so gentle and so amiable in every respect, my aversion to the former seemed to increase, while all my mother's excellence rose to my mind; and when I thought thereon, I wept. But the tears I shed, were tears of anger more than of tenderness, or they would have softened my proud, rebellious heart, and have caused me to reflect of how little value was the love I bore to the memory of that dear mother, when I was at that minute acting in direct opposition to those precepts of forbearance which she had so often recommended me to observe; and was even hardening my heart against my only surviving parent, whom I was bound, by every law, both human[69] and divine, to submit to with meekness, and to honour and obey.

But these thoughts did not then present themselves to my mind; or if they did, they were banished by the crowd of impetuous passions that had taken possession of it, and which, so far from striving to check, were rather encouraged by me.

I did not try to conciliate the friendship of my step-mother; but, on the contrary, I sought every opportunity of opposing her wishes; and by the carelessness and indifference of my manners towards her and her son, endeavoured to show how little esteem I felt for her. I really believe I should have been extremely mortified and disappointed, had she treated me with any show of kindness or consideration; as my behaviour would[70] then have wanted even the shadow of an excuse. But if I hated my step-mother, she beheld me with equal share of dislike, and, by her disdainful manners, proved she had not forgotten the salutation she had received from me upon her bridal morning; and she found a thousand ways of making me feel her power, and rendering me miserable. I upbraided, but in vain. Incessant altercation took place between us. The house was filled with noise and contention. My father threatened and remonstrated with me, but in vain. I had cast off my duty towards him, encouraged in so doing by my invidious adviser, who seemed to take a malicious pleasure in seeing us all unhappy; and who contrived to irritate my mind, under the show of soothing[71] and giving me comfort under my afflictions. Afflictions, did I say? Yes! I may well call the feelings I endured by that name; since the rankling of an angry and revengeful heart is, above all other things, afflicting!

It may seem strange and contradictory when I affirm, that though I had long ceased to treat my father with respect or affection, I was greatly hurt and afflicted by his unkindness and indifference towards me, and the regard which he evinced towards my step-brother, Antoine; whom I accused of having robbed me of my father's love, and that, like Jacob, he had stolen from me my birth-right and my blessing. Nor did I perceive that it was my own unruly temper and disobedience, which had wrought the change. How different from the[72] mild, gentle Antoine, whose uniform goodness and sweet temper were such as to win all hearts but mine, which was steeled against him by every evil passion of jealousy and hatred.

When irritated by my step-mother, I vented my anger on her son; and took a cruel delight in aggravating his usually serene temper, and rousing emotions of anger in his pure heart. All his attempts to win my regard, or to reason with me on the cruelty and injustice of my conduct, served the rather to increase my dislike to him.

It is now with feelings of remorse and shame, that I look back on the series of persecution I practised against one, whose excellence has scarcely ever been equalled. But this world was not his home; and he is gone[73] now to that place where the wicked cease from troubling, and where the weary are at rest.

One day, I remember it well, Antoine and I were at work together at the furthest part of the farm, in the little maple-copse by the stream which I before mentioned. Our employment was that of hewing the boughs of a large tree, that had lately been felled.

Antoine was naturally of a weak and delicate frame, little adapted to laborious work. I, though not so strong as some youths of my age, was yet capable of enduring greater hardships, and making far greater bodily exertions than he was. I often observed my step-brother pause during our labours, and stay his axe while he[74] rested or took breath: while I, nerved by the perverse spirit that was in me, sullenly toiled on, without giving myself a moment's respite. At length, perceiving the blows struck by Antoine grew more feeble, and made less way in our work, I reproached him, in contemptuous terms, for his want of principle in not working faster; and finished by tauntingly bidding him repose himself under the shade of the maple-trees, and look on, while he saw me, the rightful owner of the field, labouring that he might eat the bread of idleness earned by the sweat of my brow.

A flush of indignant feelings crimsoned the ashy paleness of Antoine's cheeks, at these words. I see him now. It seemed as if all the energy of his soul was roused, at that mo[75]ment, to supply him with almost superhuman strength. He caught the axe, which his last blow had struck deeply into the trunk of the tree, and with one single effort disengaged it; and with frightful vehemence he continued to smite the tree. Bough after bough gave way beneath his reiterated blows. Nor did he cease from his exertions till the task was completed, and the axe fell from his nerveless grasp; when he sunk down on the ground at my feet, with convulsed limbs, and eyes closed, apparently in the agonies of death. I gazed on him in silent horror, as he lay, pale as a corpse, before me. My trembling knees smote each other. Remorse and terror seized my heart. "Alas! what have I done!" I exclaimed, gazing with fixed eyes upon[76] the prostrate form before me. "He is dead, and I have been the cause of his death. Wretch that I am. O Antoine! dear Antoine!" I cried, regardless of my former hatred, throwing myself on the grass beside him, and vainly endeavouring to raise him in my arms; but excessive agitation had deprived me of all my strength, and he sunk over my knees a dead weight, in utter insensibility.

At that moment I suffered in my mind all the horrors of a murderer. I had, in fact, roused in the gentle bosom of my step-brother all those impetuous passions, which reason and religion had taught him to subdue, and keep under a proper degree of command; but which, once awakened, had, like the irresistible force of a torrent, whose waters had been con[77]fined by some rocky barrier, burst forth at length with uncontrolled fury, and borne down all before them. Overpowered by the violence of his feelings, and by the great bodily exertion he had used, Antoine had sunk into a death-like swoon.

I believed him to be dead; and, in unspeakable anguish, I strove to recall him once more to life. I chafed his cold hands: I bathed his humid temples with the water from the stream that flowed at my feet; and opened his breast to meet the fresh breeze. At length I beheld the faint tinge of returning animation spread itself over his pale lips and marbled cheek. I watched, with intense anxiety, his countenance. I heard, at length, his deep-drawn breath, and the sudden[78] start which proclaimed he was reviving; and soon had the happiness of seeing his eyes slowly re-open, and look upon me for some minutes, long and fixedly, as I wept over him. There was a mute, yet expressive language in that look, which spoke to my heart, and I burst into a flood of tears. They were the first I had shed for many weeks, which had not sprung from anger or mortified pride. Covering my face with my hands, I now wept long and passionately. Well had it been for me if I had listened to the awakening calls of conscience, and that those had been the last tears wrung from me by remorse; but my heart was still proud and stubborn, and was not then sufficiently touched by a sense of my own unworthiness. Possibly my feelings at that time were[79] more the result of fear, lest I had been the cause of my step-brother's death; and from extreme agitation, than of any real contrition for my faults.

However, be that as it may, for many days after this affair, I behaved less harshly to Antoine; whose weak frame and spirits had received a shock, from which they were very long in recovering. He became restless and uneasy, and a prey to nervous debility, which deprived him of his strength; and I, although the first cause of all he suffered, felt a rankling jealousy in my mind, when I beheld the tenderness which was bestowed upon him by my father and his own mother; who, whatever might be her faults, was a fond and doting parent to her son, of whose virtues and[80] abilities she was not a little proud. Antoine had been given a superior education; because, as I before stated, Madame D'Estelle, his god-mother, had intended, had she lived, to have seen him in the church; and he was about to commence his studies for that purpose, when she was suddenly called away by death, and her designs frustrated.

Though Antoine's prospects were changed entirely, his habits and inclinations still remained the same; and he was never so happy as when he was studying.

About this time, a new source of disquiet arose to vex me, which, though trifling in itself, served to increase my dislike against Antoine.

There was a custom in our village, once a year, for the pastor, assisted by[81] the neighbouring clergy, to examine all the young people, from six years old up to those of eighteen, requiring them to answer certain moral and religious questions which were proposed to them, and enquiring into their general principles and conduct.

The meeting took place in the church; and a little festival was held on the church-green, where the children all dined. The curate presided at this feast, and adjudged certain honorary gifts to those young persons who had distinguished themselves most, particularly in their replies during the examination.

That presumptuous self esteem, which had always marked my character, even from my earliest years, made me feel certain that I should be singled out among my fellows by the[82] curate. The year before, I had received a token from the curate, for my answers; and now my pride rendered me ambitious of bearing away the first prize, at the approaching day of examination.

I spent every spare hour in study, and in resolving in my mind how I should answer the curate's questions, so as to obtain me the universal applause of himself and his friends. My anxiety was not to gain the approbation of God and of my own heart, but to be looked upon as the cleverest youth in the village. Animated by a spirit like this, no wonder that I failed and fell far short of the mark; and I had the mortification of seeing the prize adjudged to another, and that other was my rival, Antoine, whose modest replies, fraught with true piety[83] and wisdom, showed how sincerely he had made religion his first thought, and its practice his delight.

I can see it, now that my heart is changed; but I could not then. I only marked the triumphant looks cast upon me by his mother, who stood among the crowd, listening with unconcealed delight to the commendations bestowed on her son.

My heart seemed bursting; and willing to hide my feelings of mortification from every eye, I bowed lowly to the curate, and withdrew, to give vent, in solitude, to the angry emotions of my heart.

I had suffered my mind to become the seat of evil and corroding passions; and, like a neglected garden, it had become one wild and thorny waste.[84]

The fair seeds of virtue, which my mother had striven so carefully to implant and nourish, had faded away for want of due attention and culture; and were choked and withered by the noxious weeds which had been suffered to accumulate amongst them.

Those baneful passions had usurped the place of kindlier and better feelings. I was a miserable, wretched creature; and imagined myself an object of scorn and hatred to every one who beheld me.

Embittered by disappointed hopes, and filled with envy against my unoffending rival, who seemed destined to cross my path and supplant me in every respect, I left the village, and wandered about the fields and woods, I scarcely knew whither, a prey to gloomy and revengeful feelings.[85]

The evening was hot and sultry, and I sought the banks of the stream, hoping to find the air cooler by the water-side. It had been a favourite amusement with me, of late, to pass some hours on the water, after the labour of the day was at an end, in a little boat which belonged to my father. I often amused myself by rowing up the stream, which, though inconsiderable just in front of my father's land, widened considerably further on, and became so rapid as to turn the wheels of a water-mill which had lately been erected over it, and which occasioned a strong current to be felt when the wheels were at work.

I was weary and oppressed by the heat of the air; and being now near the water's edge, I unloosed the boat[86] from the willow-stump to which she was fastened; and, paddling myself into the middle of the stream, let myself be carried along by the gentle motion of the waters.

I felt the light breeze that occasionally swept over the surface, refresh my fevered brow; though it could not allay the fever of my mind, which was in a state of warfare that I tremble now to recall. Every thing around me breathed the spirit of peace and happiness: the birds sung, in sweet choruses, their evening songs: the soft, plaintive bleating of the lambs from the neighbouring pastures mingled with the hum of the insect tribe, and with the murmuring of the waters as they rippled past me: the gay, joyous shouts of the children from the village, as they finished the holiday[87] they had enjoyed, with dances and sportive games, filled the air with a thousand agreeable sounds, sweet to every ear but mine, in whom they served but to awaken sensations of the most distressing nature.

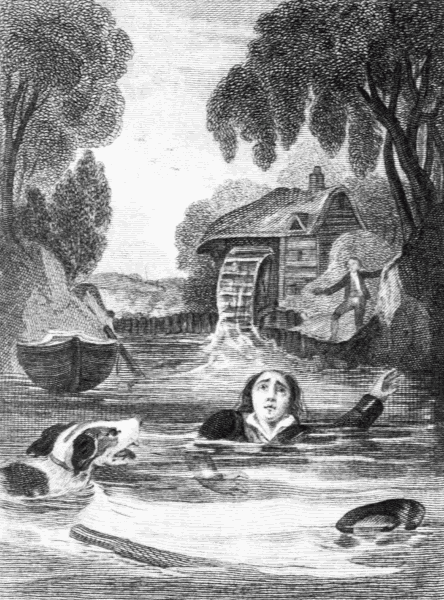

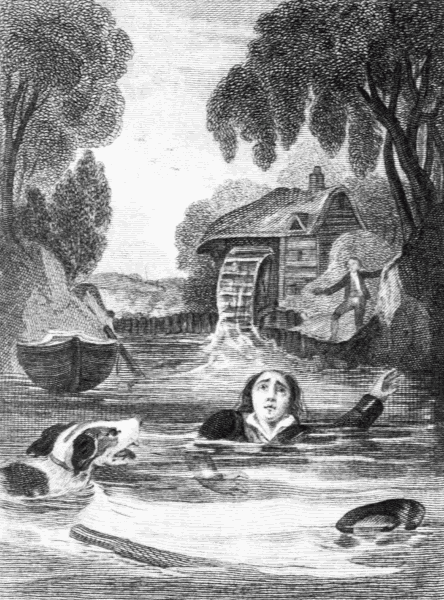

I was in this frame of mind, when a heavy plunge in the water caused me to start, and turn my eyes towards the part of the stream whence the sound had arisen. It was occasioned by Achille, Antoine's faithful and beloved dog, (the same which you now behold at my feet.) He having perceived me in my boat, had taken to the water; and stemming the tide, which was here uncommonly strong, swam towards me.

Achille had been given, when a very young puppy, to Antoine, by his god-mother, Madame D'Estelle. He[88] was a dog of the Newfoundland breed, and uncommonly large; and so sagacious, that he seemed only to want the use of speech to render him a rational creature. Antoine had taught him many tricks, which made him valuable and useful. He would fetch and carry, and was an excellent diver; of extraordinary strength and courage, yet gentle as a lamb to those he loved.

I envied Antoine the possession of this animal, and several times offered him any sum of money he would name, if he would part with Achille; but he always resolutely refused to sell him to me, declaring, with more vehemence than he usually displayed, that no inducement should tempt him to sell his beloved dog.

Angry with myself for having con[89]descended to ask a favour of one whom I hated, and still more enraged with him for having so peremptorily refused my request, I had brooded, in sullen displeasure, over the matter, and secretly encouraged a wish that, by some means, Antoine might be deprived of his favourite: so selfish and cruel was I become, by a long indulgence in evil and vindictive passions.

And now the sight of the dog recalled all my mortification to my mind, and the indignity I had suffered on his account. The regard I had entertained for Achille was turned into bitter hatred: a spirit of revenge was in my heart. I thought of his detested master, and of my fancied wrongs; and, as the unoffending ani[90]mal approached the boat, and was on the point of raising himself to leap into it, as he had often been encouraged to do, I raised the oar I had in my hand, and yielding to my dreadful and wicked impulse of hatred, I aimed a desperate blow at his head. I missed my aim. The dog dropped into the water unhurt; but the stroke descending on the edge of the boat, broke the oar short off in my hands. Determined not to be foiled in my purpose, and roused to a frantic fit of fury, I seized the other, and exerting all my strength, I again pursued the victim of my unjust revenge; and with the oar I endeavoured to drown him. I heard the bubbling of the water over his head, and the struggles of the panting animal. Exulting in the idea of having effected my pur[91]pose, again I raised my arm. At that minute a shout, a cry from the shore, arrested my attention, but did not deter me from my cruel purpose; for it was the imploring accents of Antoine's voice that met my ear, beseeching me to spare the life of Achille. The sound of his voice recalled all my past mortification. "It is now in my power to inflict a pang on his heart," I thought; and again I raised my arm, nerved with fresh rage. But there was a mightier arm than mine interposed in his behalf—an arm mighty to save. The blow I struck fell wide of the mark; but with the effort I lost my balance. The boat upset, and I was instantly precipitated into the stream.

I had never learned to swim; but a dreadful consciousness of danger[92] seemed, for a few minutes, to give me power to sustain myself upon the water, though it was only to give me time to see the horrors of my situation. I felt the irresistible current of the mill-dam hurrying me forward to destruction. Ay, to the destruction both of body and soul. I strove to cry for help, but a strangling sensation in my throat choked my utterance.

Struggling at length with frightful violence, to overcome the choking feeling that oppressed me, I cried aloud, in accents of wild despair, "Is there no one to help me? I shall die. Oh, save me! save me: I dare not die!" I wildly screamed; for I felt, at that dreadful moment, that for me there was no hope for mercy beyond the grave. I heard a voice calling to[93] me from the shore; but the sound rung confusedly in my ears. I felt a whirling sensation in my head—an intense weight pressing on my brain. As the gurgling waters closed over me, a sound of many waters was in my ears: a dense suffocation; and a bewildering idea of death, and of the judgment to come, presented itself to my mind, as I sunk below the rushing waters.

I had risen again for the last time. The horrors of death were upon me. A horror of thick darkness was before my eyes. A bewildering, confused idea that I was in the grasp of some one, who was forcibly striving with the current to drag me to the shore, was the last thought that presented itself to my mind; and then all was forgotten.[94]

"Think, Sir," continued Philippe, when, after a pause of great agitation, he resumed his story, "what must have been my feelings of remorse and shame, when I at length unclosed my eyes and became conscious of existence, to find myself supported in the arms of my injured step-brother; while Achille, the innocent victim of my unjust fury, lay beside me, dripping from the stream with starting eyes; and panting from the desperate efforts he had made to sustain me above the water, and combat with the eddying current of the mill-stream."

"Yes, noble, generous Achille!" exclaimed Philippe, stooping to caress the dog, who lay stretched at his feet, "it was you, who, disdaining revenge, had nobly turned to save a sinking[95] wretch, who, but an instant before, had inhumanly sought to deprive you of your life! You, who with unparalleled generosity, urged by the commands of your dear master, rescued me from a watery grave, and saved my soul from bitter pangs and everlasting torments, where 'the worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched[3].'"

"Marvel not, Sir," he added, addressing himself to the curé, "that I [96]should refuse to forsake this animal; or that I should resist, with indignation, the idea of depriving him of life, who had so generously saved mine. No, I would have perished with hunger, ere I would have deserted him." Here his voice faltered; and bending to meet the caresses of the faithful Achille, he wept, for some minutes, in silence: then, struggling to overcome his emotion, he once more resumed his tale.

"The first object that met my eyes was my step-brother, who, in sweet, soothing words, strove to reconcile me to myself, bidding me to be comforted. But I felt I was a wretch unworthy to live. Yet, was I fit to die? Alas, no! to die with all my unrepented-of, unatoned-for sins upon my head. A sick feeling came[97] over me: a deadly shuddering crept through my veins: the horrors of death seemed approaching. I strove to speak; but my voice died away, in faint murmurs, on my trembling and convulsed lips. There was a faint fluttering at my heart, as if its pulses were about to cease for ever. A dull mistiness spread before my open eyes. I felt the warm gushing tears of Antoine fall fast over my brow. 'Brother, dear brother, forgive me!' I would have said; but before my lips could frame the words, I had sunk upon his shoulder in a death-like swoon.

"How long I remained in that unconscious state, I can form no idea, since time passed unheeded by me for many days; during which, I was un[98]der the influence of a raging fever, whose violence threatened to terminate my life, or reduce me to a state of mental insanity.

"The violence of the disease at length abated, and with returning reason came the dreadful consciousness of all my crimes. For the first few moments after my restoration from the waters, I had said in my heart, 'Surely the bitterness of death is past;' but I now found the pangs of a guilty and awakening conscience far more painful to endure, than even the struggles of death had been. When the full conviction of all my crimes burst upon me, I covered my burning face with my hands, that no eye might look upon me; and exclaimed, in the excess of my despair, 'I have sinned past all hope of forgive[99]ness. It were better for me to die, than to live despised, degraded, and abhorred by myself and by the whole world. Oh! that I had gone down to the grave, and died in that fearful hour, when the waters closed me in on every side—when the weeds were wrapped about my head.' But as I uttered these words, conscience whispered to me of judgment—of a world to come, where all shall be summoned to deliver up an account of the deeds which they have done; and not only of every evil action, but even of every evil thought, word, or look. And how should I have appeared before a righteous and just Judge? Would he not have exclaimed, 'I know you not: depart from me, all ye who work iniquity?' Such were the reflections that occupied my mind, as I lay on the[100] bed of sickness. Sometimes I thought of my mother, and of all the pains she had taken to root out the evil inclinations of my nature; and I felt happy in the consciousness that she, at least, was spared the sorrow of seeing her child suffering under the agonies of remorse, and stained with crime. Ah! little did that dear mother think that the child she so fondly cherished would ever live to weep the hour she gave him birth. 'Surely,' I exclaimed, 'my mother, you have been mercifully taken from the evil to come.'

"During my long illness, Antoine never left me: he was my nurse by night as well as by day. His arm it was that supported my drooping head: his hand smoothed my pillow, and held to my parched lips the cooling draught: his sweet voice soothed my[101] ravings, and spoke peace to my broken heart. He whom I had hated, envied, and outraged in every possible way, was now the only friend who came near, to watch by my bed and administer to my wants. How often, when he imagined me to be asleep, has my pillow been bathed with tears of anguish and contrition for my past faults.

"How often did I resolve to throw myself on his neck, and pour out my whole soul before him, and implore him to forgive me; but a sense of shame and false pride sealed my lips, and the words I would have spoken died away, as though my rebellious tongue refused to obey the dictates of my heart.

"How often would I grasp his[102] hand, and look wistfully in his face, while tears chased each other, in quick succession, down my cheeks; and the confession I was about to make was choked by sobs and tears.

"One evening, he perceived me to be more than usually agitated; and, as if he understood what was passing in my mind, he took my hands, and kindly pressing them in his own, said, in a soothing tone, 'Philippe! dear Philippe! weep no more. Forget that you have ever erred against me. Let us henceforth live as brothers—as though we had both been children of the same parents."

"'Is it possible you can forgive me, Antoine?' I replied, regarding him with tears in my eyes. 'And can you forget all the injuries I have so often done you, and the hatred I have[103] borne against you? And will you look with affection on one who has so often slighted your friendship?'

"He replied, by throwing himself on my neck, and mingling his tears with mine. 'Ask not forgiveness of me, my brother,' he said: 'I am a frail, erring creature, like yourself: it is against God only that you have sinned, and done this evil in his sight.'

"I trembled exceedingly. 'Alas!' I cried, 'how shall I venture to ask forgiveness, when my sins are so manifold? or how shall the merciless dare to look for mercy? Will he not say, With the measure that you meted, it shall be measured to you again.' I groaned, and hid my face beneath the coverlet of the bed: despair was in my heart.

"'Remember, Philippe,' Antoine[104] replied, 'that the Saviour who died for you, has promised remission of sins to all who turn to him with humble and contrite hearts, and call upon his name. Your Redeemer is mighty to save, and nigh unto the prayer of the penitent sinner.'

"'Antoine,' I said, mournfully shaking my head, 'is it not written in the holy book, The soul that sinneth it shall die.'

"'Yes,' he replied quickly, 'the hardened, guilty, and impenitent soul, that will not repent, and forsake his sins and live. It is written in the same Scripture, Let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts; and let him turn unto the Lord his God, and he will save him, and to our God, and he will abundantly pardon. We are all sin[105]ners, and all fall short of those commands, which require us to be perfect even as our Father who is in heaven is perfect; but we have a Mediator, who has given himself to be a ransom for the sins of the whole world.'

"I listened, hoping, fearing, trembling: Antoine bade me pray.

"'Pray for me, and with me,' I cried, overcome by a sense of my own unworthiness; and, bowing my face on my hands, I poured out, for the first time, a humble and fervent petition, for pardon and forgiveness of all my sins. The tears I then shed, were the first fruits of a real and lasting repentance: my proud spirit was subdued—bowed to the very dust.

"Antoine knelt beside my bed: I felt his tears fall fast over my hands, which he held clasped in his; I heard[106] him offering up prayers of intercession for me at the throne of grace; I felt his prayers were accepted. The spirit of Peace seemed to be with him, and near him. Raising his eyes to my face, full of hope and faith, he said: 'The Lord, my brother, has heard the voice of thy weeping: thou shalt not die, but live, and declare his glory to those who are yet to come.' I listened with trembling hope to his words of consolation: I believed, and finally found rest to my wearied spirit.

"One morning, when I was beginning to recover my strength, so as to be able to sit up during part of the day in my chamber, Antoine came to me: 'There is a friend,' he said, smiling, 'who is desirous of seeing you, and congratulating you on being[107] thus far recovered.' I shrunk from the idea of being seen by strangers, or by any of my former acquaintance. 'Antoine,' I said, in an earnest tone of entreaty, 'do not let me be seen by any one: they will ask me questions as to the cause of my illness, which I cannot endure to answer.'

"But your friend will ask you none," he said.

"Nevertheless, I cannot see him," I replied, while tears came into my eyes.

"Well, then," he answered, "I will tell him so;" and he went to the door: there was a sound of steps on the stairs.

"See," said Antoine, "he will not take his dismissal but from your own lips; and, as he spoke, my faithful friend and preserver, Achille, rushed[108] into the room, and springing on me, caressed me with every mark of affection. The sight of the dog renewed all my former grief. 'Hast thou come,' I inwardly exclaimed, 'to call my sin to remembrance?' and, leaning my head upon his shaggy neck, I burst into a flood of tears. 'And could I ever have been such a wretch, as to strive against thy innocent life, noble animal,' I said: 'and how didst thou revenge thyself on thy enemy? even by saving his life, at the risk of thine own!'

"Antoine told me, that Achille had made many attempts to obtain admittance to me; but, fearing lest the sight of him should agitate me in my weak state, he had not suffered him to enter my chamber; but this day[109] he had not been able to restrain his impatience.

"I was so touched by the interest and affection which Achille evinced in my behalf, (far greater than that shown to me by my own father, who but seldom visited my sick bed,) that I vowed solemnly, that from that hour Achille should never want food, while I had a morsel to share with him, nor would I ever part from him while I lived. Little did I then think the time was approaching, when I should feel the pangs of hunger, and want morsel of bread wherewith to satisfy the cravings of nature.

"I was now once more again able to leave my chamber, and breathe the fresh air. But what a change had taken place in me, since last I had[110] paced the limits of our little garden! How different were my feelings a few weeks back, I thought, as, for the first time since my illness, I crossed the threshold of the door, leaning heavily on the arm of my step-brother for support. I turned my eyes on the face of Antoine, as I pondered these things in my mind: he seemed as though he had read my thoughts.

"Little did you think, nine weeks ago," he said, "that the time would ever come, when you should enter this garden, resting in perfect love and confidence on the arm of your once-hated step-brother, Antoine."

"Now bound to me," I hastily interrupted, "by ties of affection more holy than that of kindred. But how shall I ever repay you, Antoine, for all your goodness to me, who have[111] hitherto proved myself so unworthy of your regard?"