It has become the fashion, in sketching the life of the present Governor-General of Canada, to preface the narrative of his personal career by an historical account of the great Scottish family to which he belongs. Such an account is very easy to write, for the materials are ample; and very easy to read, for the subject-matter is interesting. Those persons, however, who desire such information will be at no loss where to look for it. In the present sketch we can merely afford space to glance at two or three of the most noteworthy events in the history of the great house of Argyll.

Our late Governor-General, in his picturesque work of travel called “Letters from High Latitudes,” indulges in a monologue which he calls “The Saga of the Clan Campbell,” wherein he goes over the accumulated traditionary lore of centuries, and brings the account of the family down to the present times. The account is half mythical and wholly poetical, but doubtless contains a large element of fact. The earliest records of the house of Argyll are enveloped in the twilight of fable. During the comparatively modern period of the eleventh century, Gillespick Campbell acquired by marriage the Lordship of Lochow, in Argyleshire, and from him descended Sir Colin Campbell of Lochow, who, distinguished as well by the great acquisitions he had made to his estate as by his valorous achievements in war, obtained the surname of “Mohr,” or “Great.” From him the chief of the house is to this day styled, in Gaelic, MacCallum Mohr—a corruption of “the Great Colin.” He was knighted by Alexander III., in 1280, and in 1291 was one of the prominent adherents of Robert Bruce in the contest for the Scottish Crown. This chieftain was slain in a contest with his powerful neighbour the Lord of Lorne, at a place called the String of Cowal. The event occasioned continued feuds for a series of years between the houses of Lochow and Lorne, which terminated at last, after the fashion in which such quarrels frequently terminated in those days, by the marriage of the first Earl of Argyll with the heiress of Lorne. The history of the family for several centuries after this event may almost be said to be the history of Scotland. Early in the seventeenth century the head of the house, called Gillespie Grumach, or Archibald the Grim, became the first and last Marquis of Argyll, and during Cromwell's Protectorate was brought to the scaffold for his espousal of the Royalist cause. His son and heir escaped to the continent, but subsequently returned to Scotland to co-operate with the Duke of Monmouth's ill-starred rising in the south. Upon the defeat of that enterprise he was captured and put to death. The estates were confiscated, and the family name seemed doomed to extinction. The Revolution of 1688, however, brought it once more to the front, Pg 2 and its representative was created Duke of Argyll and Marquis of Lorne. The next successor to the title, though a somewhat unstable politician, played a very conspicuous part in the history of his time, and has been immortalized in verse by Pope, and in prose by Sir Walter Scott. The chief representative of the family at the present time is the eighth Duke of Argyll, a statesman who has held office under several administrations, and who has achieved some reputation as a scientist and a man of letters. The last official position held by him was that of Secretary of State for India, which he held from the time of the formation of Mr. Gladstone's cabinet, in December, 1868, down to the deposition of the Liberal Government in February, 1874. While still young he took an active part in the controversy respecting patronage in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. He arrayed himself on the side of Dr. Chalmers, by whom he was esteemed as a potent adherent, and both his voice and his pen were vigorously lifted up in exposition of his views on ecclesiastical matters. In 1844 he married Lady Elizabeth Georgiana Sutherland Leveson-Gower, eldest daughter of the second Duke of Sutherland, and late Mistress of the Royal Robes. To the extra-Parliamentary world the present Duke of Argyll is probably best known by his “Reign of Law,” a series of essays published in 1866, in which the evidences of a presiding will, as opposed to those who would refer all phenomena to the operation of non-intelligent causes, are ably brought out. His work on “Primæval Man,” published in 1869, deals with a similar subject, and attacks in an acute, a popular, and withal a scientific fashion, the theories of evolution and development. His latest important work, “The Eastern Question, from the Treaty of Paris, 1856, to the Treaty of Berlin, 1878, and to the second Afghan War,” made its appearance at the beginning of last year. It was the first adequate attempt to set forth in detail the important subject of which it treats: an attempt in which the author was remarkably successful. The book threw new light on a great deal of matter which had previously been unknown to the world at large, and no one who is unacquainted with its contents is capable of intelligently criticising or discussing the Eastern Question. The Duke's visit to this country last year, and his intelligent criticisms subsequently published on both sides of the Atlantic, are still fresh in the minds of all readers of these pages. He has a numerous family, the eldest of whom, John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, by courtesy known as the Marquis of Lorne, is the present Governor-General of Canada. Another son is a banker in London; and another is, or recently was, prominently connected with the trade of London, Liverpool and New York.

On the corner of the Green Park and the avenue known as “The Mall,” with its west front overlooking the former and its south front facing St. James's Park, stands Stafford House, the town residence of the Duke of Sutherland, the finest private residence in London, and, in its interior appointments, probably the most splendid private mansion in the world. It is readily accessible to the public, and philanthropists and other persons interested in social reform are occasionally permitted to hold meetings in the magnificent drawing-rooms, which are in their way as well worth seeing as anything that London has to show. Many of our readers will recall the novel exhibition of multiform wicker coffins held there several years ago, when the question of human sepulture was the subject of so much discussion. In one of the imperial chambers of this mansion, on the 6th of August, 1845, was born the subject of the present sketch. The only information respecting his childish days which has come under our notice is contained in Her Majesty's Pg 3 “Journal of Our Life in the Highlands,” under date of August, 1847, at which time Her Majesty and the late Prince Consort paid a visit to Inverary, the ancestral seat of the Argylls. Speaking of the reception at the Castle, the Royal journalist writes:—“It was in the true Highland fashion. The pipers walked before the carriage, and the Highlanders on either side, as we approached the house. Outside stood the Marquis of Lorne, just two years old, a dear, white, fat, fair little fellow, with reddish hair, but very delicate features, like both his father and mother; he is such a merry, independent little child. He had a black velvet dress and jacket, with a sporran, scarf, and Highland bonnet.” The Royal visitor took the little fellow in her arms and kissed him. About nine months subsequent to this event Her Majesty gave birth to a daughter, who was destined to become the bride of the “white, fat, fair little fellow” eulogized in the foregoing passage.

His early education was received at Eton, whence, later on, he passed successively to the University of St. Andrew's and Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1866 he was appointed Captain of the London Scottish Rifle Volunteers, and subsequently became Lieutenant-Colonel of the 105th Rifle Volunteers. During the same year he made a tour through the West Indies and the eastern part of the North American continent. The result of his observations during this trip were published under the title of “A Tour in the Tropics,” a work said to display a keenness of observation and a soundness of judgment not often found in the productions of titled or untitled travellers. His tour included brief visits to the principal cities of the Dominion, and the work contains short notices of Niagara, Toronto, Kingston, and Ottawa. In 1868 he entered the House of Commons as member for Argyleshire, and continued to represent that constituency down to the time of his appointment to his present high position. During part of his father's tenure of office as Secretary of State for India the Marquis acted as his private secretary. On the 21st of March, 1871, occurred what up to the present time has been the most important event of his life—his marriage with Her Royal Highness the Princess Louise. The wedding took place in St. George's Chapel, Windsor, and was solemnized with imposing ceremonies. There is as yet no issue of the marriage. Soon after this event his name was spoken of in connection with the Governor-Generalship of Canada, and it was then for a short time believed that he would succeed Sir John Young; but after some delay it was considered expedient to appoint Lord Dufferin to the office. He subsequently devoted himself chiefly to literary and artistic pursuits, for which he has a highly cultivated taste and considerable ability. Several years ago he published “Guido and Lita, a Tale of the Riviera,” a poem of much sweetness and beauty, which would have attracted attention even if it had proceeded from an obscure and unknown hand. In August, 1877, he put forth another poetical venture, “The Book of Psalms Literally Rendered in Verse.” The rendering is smooth and harmonious, and has been highly praised for the taste, industry, and general literary ability displayed in its composition.

When Lord Dufferin's term of office had nearly expired, and it became necessary to appoint a successor, it began to be rumoured that the appointment was to be conferred upon the Marquis of Lorne. Towards the end of July, 1878, the announcement was made that the appointment had been actually offered to and accepted by him. In advising Her Majesty to confer this appointment upon her son-in-law, Lord Beaconsfield signally manifested his aptitude for gauging the sympathies of the English people in this country. The feeling of effusive loyalty which he has of late years been so assiduous in cultivating in the public mind of Great Pg 4 Britain found a hearty echo on this side the Atlantic when it became known that the Marquis of Lorne and his consort were to take up their abode among us. The appointment was hailed with satisfaction in all parts of the Dominion, and the new Governor-General entered upon his term of office with the hearts of the people strongly prepossessed in his favour. In Canada, loyalty has by no means degenerated into a mere feeble sentiment of expediency. Throughout the length and breadth of our land the name of Queen Victoria is regarded with an affectionate love and veneration which is felt for no other human being, and this love has gone out with fervour towards the fair young daughter who, during her residence among us, has been, and will be—and that in no merely conventional sense—the first lady in the land.

His Excellency has not yet been long enough among us to enable us to know him as we had all learned to know Lord Dufferin before his departure from our shores, and it is perhaps too early to pass a final judgment upon him. Instead of any comments of our own upon his qualifications for the high position which he occupies, we submit the opinion of the London Times, which in a recent article remarked that “The experiment which was tried when the Marquis of Lorne was appointed Governor-General of the Dominion has been crowned by complete success. It has been found possible to appeal effectively to the loyalty of our colonial fellow-subjects without placing in jeopardy for a moment the dignity of the Crown or the solid interests of the Imperial connection. It is only fair to acknowledge that Lord Lorne has played a difficult part with remarkable ability. The very enthusiasm of which his illustrious consort was the object might easily have misled him. The Canadians, like other colonists, are painfully susceptible. They are on the watch for slights which are never intended; they resent bitterly anything which seems like an assumption that they are aliens, but not less so anything which may be construed to mean that they are dependents.”

Her Royal Highness Princess Louise Caroline Alberta, Duchess of Saxony, was born March 18th, 1848, and at the time of her marriage had just completed her twenty-third year. She is the sixth child and fourth daughter of Her Majesty. Since her marriage brought her prominently before the public she has been regarded with affectionate interest by the people of Great Britain, and her personal qualities, independently of her high rank, are such as to have earned for her the love and respect of her associates. She is very proficient in art and music, and it is said that some of the brightest fashion and art notes in one of the leading fashionable journals were written or inspired by her. Her work on lace is pronounced by competent critics to be of exceptionally high merit, and she has also shown much ability in design. The bridal veil of Honiton lace worn by her at her marriage was designed by her, and her etchings and sculpture repeatedly exhibited at the Royal Academy are said to show a high degree of excellence.

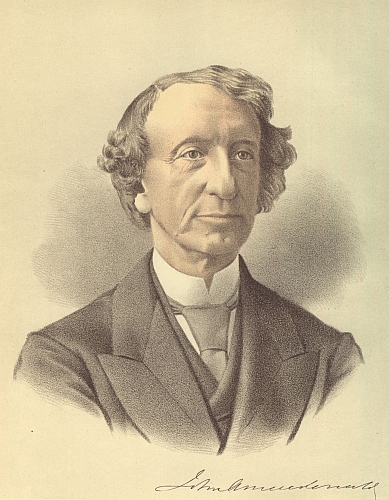

No other public man has held influential positions in the government of Canada so long as Sir John Macdonald. And yet he has not far passed that time of life when English statesmen are held to be in their prime. If he had the constitution of a Palmerston or a Brougham, he might still count on fifteen years of future activity.

In looking back on the public career of Sir John, one cannot avoid asking what are the qualities which have enabled him to take a prominent part in the government for an exceptionally long period. The shortest answer that could be given would perhaps be that he possesses unusual facility for falling into well defined grooves of public opinion, and of conciliating opponents when conciliation becomes necessary. In this way he profits by the labour of others, and knows how to reap where he had not sown. Sometimes, so far from having encouraged the sowers, he did all he could to obstruct their operations. When the crop was ripe, he was ready to put in the sickle. To this power of appropriation, which enabled him to profit by the labour of others, he owes much of his success. He recognizes the truth that there is a time to oppose and a time to accept. He will pursue one line of policy as long as it is tenable, and abandon it for an opposite line when it has ceased to be practicable. This treatment he extends to measures; so that, in the progress of his public career, it has happened that he has accepted at one period what he had previously rejected, combated, and decried. In this way, Sir John has kept nearly abreast of matured public opinion, and he may always be relied on to move with the current, when it has become strong enough to bear down the minor forces which impeded its progress, and a reliance on which, for a time, best suited his purpose. In the early and hopeless stages of an agitation for some new reform, his conservative instincts are indulged; when the hour of victory approaches, he recognizes the necessity of the change. A man whose Conservatism is thus qualified and limited is the reverse of a doctrinaire, but in the path of practicable political progress he can never be far behind others.

Sir John's power of appropriation is not confined to measures. He is at least equally successful in utilizing men, in overcoming their antipathies, and in gaining the assistance of old opponents. He has the rare faculty of attaching these recruits to his banner at the very time when he has the most need of them; sometimes when his political fortunes would be desperate without their aid. His personal magnetism, here of the greatest use to him, combined with the attractions of office, proves stronger than old party ties, stronger than the recollection of old alliances, and even stronger than the fear which men have of losing that sympathy which comes in the form of the expression Pg 6 of a favourable opinion from those whose disregard is most dreaded. In thus strengthening himself, Sir John is seldom able very seriously to weaken the enemy. The changed personal convictions and the new sense of duty implied in these accretions to the forces of the minister are generally confined to a few, and are often deviations from the rising current of public opinion. The recruit who goes into battle for the new cause recognizes the danger he runs, if he takes the trouble to count up the victims of these somewhat miraculous conversions. But Sir John gets the needed accession of strength, his policy is sustained, and his administration continued. The enmities he makes in the collision of political strife are never, on his side, implacable. He must have made it a rule of his public life never to refuse to co-operate with any public man on account of former antagonism; for he has always shown himself ready, if there were a good reason for it, to accept as colleagues men by whom he had been bitterly opposed, and whose hostility he had duly reciprocated. The allegiance borne him by his party is a willing and voluntary allegiance; but, in individual cases, its ardour is often damped, and mutiny threatened in muffled tones to some confidential friend. This usually happens when distance removes the follower from the personal influence of the leader; but a single interview generally converts a rebellious subject into a devoted partisan. The secret of this influence, which is so commanding as to be almost irresistible, is chiefly personal. Sir John's estimate of motives seldom errs by ranking them too high; but there cannot be a doubt that, on the whole, he measures men with a singular degree of accuracy. It has happened scores of times that, in half an hour, he has reclaimed an old friend whose feelings had been almost wholly alienated. By what secret magic did he bring about this result? In most cases, it will be found that he has promised no part of the patronage which it is in the power of a first minister to bestow. He has removed some misapprehension under which the semi-rebellious subject laboured; he has met every objection with a plausible if not unanswerable reply, and has so managed to get the better of the argument. It has been charged against him that he insinuates promises in so general a way that he can never be called upon to fulfil them; as if the reverse of that which Clarendon said of Lord Falkland were true of him, that “he could as easily have given himself leave to steal as to dissemble, or to suffer any man to think that he would do a thing which he resolved not to do; which he thought a more mischievous kind of lying than a positive averring what could be more easily contradicted.” We do not believe that the insinuation, put in this gross form, is true, though it may well be that many have too hastily inferred, without any direct promise, that Sir John would do what they had asked of him. The misapprehension, when such exists, is, we believe, frequently on their side.

The practice of keeping up the strength of his parliamentary following by winning recruits from the enemy, is one that has often shaken, for the moment, the mental fidelity of old friends, though the discontent may not have been translated into any overt act. The new recruits which have so often closed up the shattered ranks of the ministerial party, have not unfrequently been worked upon by the envious as successful rivals for the favour of the distribution of patronage, and they have lamented that their own claims, which they have believed to be paramount and incontrovertible, have been postponed to those of men who, till yesterday, had always been found in the opposite camp. But these complaints, which in a personal view were not altogether without foundation, were almost invariably silenced in the first interview between the Pg 7 offending minister and the offended follower. It was easy for the minister to show that the measure taken was the best for the party, and that in no other way could its effective strength have been kept up, and its hold on power maintained.

It must sometimes happen that the supply of new supporters won from the ranks of the opposition will fall short of the requirement. Under some conditions, Sir John has found it all but impossible to obtain from the ranks of either party the material to fill vacancies in the Cabinet, or to give a little much needed additional strength in the House. There have been other occasions in which tenders of outside support have been refused, on account of the conditions attached to them. It has happened, too, that conditions which the minister refused one day, would have been accepted the next, when the danger of defeat became imminent, unless the ministerial forces could be recruited. It may safely be said that Sir John never seeks or accepts outside aid from preference; every new alliance of the kind under consideration is, in some measure, forced upon him by the pressure of necessity. These new recruits are generally the most timid of mortals; fearing, as the worst punishment that could overtake them, to forfeit the good opinion of those whom they appear to desert. The manifestation of this fear has many degrees; the greatest of which is that of encountering the scoffs which they know will follow their changing their habitual manner of voting. Some old opponents who have joined with Sir John in the same Cabinet, whom the public would not generally credit with a want of courage, have made the change with fear and trembling; they have never felt at ease under the hostile criticism to which their new position exposed them, and have soon been at a loss whether to retreat or advance. A man who felt that he could, by a determined effort, recover his position, would probably retreat; a man of less force, and smaller personal resources, had nothing to do but to remain where he was, enjoying his present opportunity, and finally go down with the ship on which he had embarked. A minister with such a contingent of allies and supporters has more than the usual opportunities of seeing the different sides of public men. The knowledge thus obtained is far from being useless to him if, like Sir John, he possesses in an eminent degree the faculty of turning it to account.

Sir John's power of placating sullen followers, or of alluring recruits from the hostile camp, is probably about equally great. A remarkable instance of the latter occurred soon after the epoch of Confederation, and it may be given as an example. Nova Scotia had been protesting against the union, into which Mr. Howe and his friends complained that he had been dragged. Everything short of rebellion, and very little short of that, had been threatened. The leader of the Federal Government saw the necessity of allaying an opposition which was as persistent as it was fervent and active; and the best way of doing this was to reconcile Howe, the most stalwart son of Nova Scotia, to the new state of things, and induce him to aid in working the detested machine of Confederation; a feat the accomplishment of which would be a guarantee to Mr. Howe's friends that its supposed dangerous qualities would be minimized in the operation. At this time the leader of the Ontario Government had, for some reason, become thoroughly disaffected to the Premier of the Dominion. The hostility, though not very notorious, was restrained with difficulty, and was in danger of finding open expression on some unforeseen emergency. In obtaining the services of Mr. Howe, the aid of the Ontario Premier would be very useful if it could be got. Sir John resolved to ask this aid; though most persons in his position would probably have concluded that Mr. Pg 8 Howe, to whom a seat in the Cabinet could be offered, would prove an easier conquest than the Ontario Premier, who was already in possession of all Sir John had to give him, and whose ill-concealed hostility was taking a more personal form than that of Mr. Howe. When the two Premiers met in the Queen's Hotel, Toronto, there was much reason to fear an explosion, for it was with great difficulty that Mr. Sandfield Macdonald restrained the expression of his feelings. They walked separately to the Attorney-General's office, and when they were left alone their mutual friends feared that an open rupture would be the result of their meeting. What happened? In less than an hour the Ontario Premier confided to a friend, whom he met in the street, that he and his namesake of the Dominion were to start next morning, by different routes, to win over Howe, by their joint persuasions. Such an exertion of personal influence over a man who could himself exercise no small share of magnetic influence, is as remarkable as it is rare, and it attests the possession by Sir John of those qualities which pre-eminently qualify a man to be a leader of men.

Sir John's habit of delaying, often for weeks together, to fill offices that fall vacant, has been an enigma alike to friends and foes. There is no reason to conclude that it is referable to constitutional indolence. It is the result of some inexplicable calculation of policy; but it is not the less difficult to believe that it is a policy that pays. When remonstrated with on the seeming folly of disappointing fifty persons, whose applications might easily have been forestalled, and the opposite policy of Sir Francis Hincks has been held up in contrast, he has, in vindication of his own course, pointed to the fact that the life of his administration has been much longer than that of the gentleman named. It may be that when a large number of men, more or less influential, have asked favours from the head of the government, they feel to a certain extent in his power, and that to do anything that might, under the circumstances, look like desertion, would be a disgrace. Once, on quitting office, Sir John gave mortal offence to his followers by leaving, as a prize for his successor, half a hundred offices vacant; but on a subsequent occasion, resolving not again to subject himself to a like reproach, he ran too near the wind by making a large number of appointments when his administration was in a moribund condition, and almost virtually defunct.

Mr. Macdonald had not the advantage of a University education, and was put to the law when a lad of fifteen years of age, having been born on the 11th January, 1815. His father, who had emigrated from Sutherlandshire, Scotland, in 1820, and settled in business at Kingston, Ontario, sent his son to the Royal Grammar School, in the latter town, where at first the boy had Dr. Wilson, and afterwards Mr. George Baxter, for teachers. Here the pupil showed more than the average talent for mathematics. Beyond this, his teachers did not observe in the pupil any marked signs that he was destined for the career he has actually run. At twenty-one our future statesman was called to the bar, an age at which law students of the present day very often only enter on their studies. It is impossible to believe that this early maturing was an advantage, in point of thoroughness; the only thing in its favour was that it gave the subject of it an early start in the career of active life. Greater leisure, more prolonged preliminary studies, the opportunity of travelling before settling down to serious work, would have given the young lawyer an advantage similar to that which a man gets from a run before he jumps. But his genius for government, added to long experience, went far to supply the want of those advantages.

The young lawyer commenced practice in Pg 9 the town where his father lived, and where he had pursued his studies. He was attentive to the duties of his profession, and soon acquired a considerable practice. As barristers often owe much to the occurrence of some conspicuous opportunity for the display of their talents, the trial of Von Shultz, who had led the band of marauders which came across the border, in the name of liberators and sympathizers, in 1838, gave this opportunity to young Macdonald. Von Shultz had been entrapped, as it were, by illusive representations, into an enterprise which was an anachronism and a folly, for the rebellion had long before been put down, and the invasion had not the remotest chance of success. Mr. Macdonald could not prevent his client being convicted and hanged—that would have been impossible, in the face of the evidence—but he gave proof of the possession of forensic talents which at once established his reputation, and gave him no mean position among the leaders of the bar. This was accomplished in the year 1839, when the advocate was only twenty-five years of age. That year he had entered into a law partnership with Mr. (now Senator) Campbell.

If a very early call to the bar be a doubtful advantage, an early connection with politics is almost essential to success in that line. A man who has no taste for politics till he is forty, had better conclude that his vocation is to be sought elsewhere. At thirty-one, Mr. Macdonald was elected to represent Kingston in the second legislature under the union. The times were not propitious for the formation, out of raw materials, of promising Conservative statesmen. Portentous clouds overcast the political horizon. Responsible Government was then only struggling for recognition; and Sir Charles Metcalfe, the new Governor-General, jealous of his own supposed prerogatives, and conscientious in the discharge of what he believed to be the duties of his position, was prepared to resist its application in the way his ministers thought it ought to be applied. If the ministerial contention were true, that the government must mainly be conducted on the English model, the great anxiety of Sir Charles was to know what would become of the Governor-General? That question assumed additional importance in his eyes from the fact that the person who asked it happened to be Governor-General. He could not brook the thought that the Governor-General should be reduced to the deplorable condition of the sovereign. He had governed in India, he had governed in Jamaica, and he had come to Canada to govern; and what was more, he was not going to be driven from the path of duty, which was to him also the path of honour. A quarrel with his ministry over appointments to office led to their resignation before the end of November. Nothing could show more convincingly that during the whole of its existence this administration had been under some external restraint, than the fact that, of all the officials gazetted, it had consented to become responsible for the appointment of a majority of them from the ranks of its political opponents.

The battle of Responsible Government was now to be fought; and the Conservatives who succeeded to office were in a measure bound to adopt, in theory at least, the views of the Governor-General. To do so was in exact accord with the habitual temper of the old official party. Young Macdonald was fated to take his first practical lessons in statesmanship in an illiberal school; but his elastic mind was destined in due time to break through the restraints of their unconstitutional doctrines. He was not spoiled by the bad training he underwent. He did not plunge with premature impetuosity, as young members often do, into the debates of the House; he had the discretion and the good sense to speak only when he had something Pg 10 to say. In 1847 his official experience began; in May, he was selected by Mr. Draper for the office of Receiver-General. As he was destined in future to hold by turns nearly every office in the Government, so it was not long before he was transferred to the Crown Lands. In these days, the Crown Lands Office was as much noted as the Court of Chancery in England, its worst days, for the interminable delays that prevented adjudication upon rival claims and disputed questions. Mr. Macdonald obtained, as most of his successors afterwards obtained, credit for his prompt decisions. Before the Draper Administration had been defeated in the beginning of 1848, the country had, through a change of Governors, been assured of a constitutional régime. Lord Cathcart filled the gap between the retirement of Lord Metcalfe and the arrival of Lord Elgin. Lord Elgin, who was thoroughly imbued with constitutional ideas, carried out to its full and legitimate extent the principle which Metcalfe had lashed the Province into a storm of anger to defeat. But at no time could the Draper Ministry have existed a single day without a majority in the Legislative Assembly; and it is remarkable by what a small majority this administration was enabled to hold power from November, 1844, to March, 1848.

Mr. Macdonald, with his party, was now in opposition, where he was destined to remain until 1854; and then only to share power with the other party, in a Coalition Government. These years of opposition were years of valuable experience and useful discipline. Before he went back to office, his powers of debate had been greatly strengthened, and there was but a single antagonist in the House for whom he was not a full match. In 1849 he opposed the reform of King's College, which, by the abolition of the Divinity chair, took away its sectional character and gave it the impress of a national institution; but after the second reading of the bill his opposition practically ceased. The Rebellion Losses Bill of the same year found in him, as well as in the whole Conservative party, a persistent opponent. Regarding the intended object and certain results of the measure, the two parties expressed the most opposite views. The Conservatives described it as a Bill to compensate rebels for the loss of property which they had suffered as the consequence of their own acts, by which great injuries had been inflicted upon others; the Government and its supporters contending that this class would be utterly excluded from its benefits. The violence of party excitement reached its highest pitch. If this state of feeling had long continued, the public interests would have greatly suffered. As a consequence of the excitement the Parliament buildings had already been burned by an infuriated mob, which comprised many persons of the highest reputed respectability. Never were the two political parties in a state of more bitter antagonism. But the truth of the adage that there is a tendency of extremes to come together was soon to be exemplified in a remarkable degree. The Lafontaine-Baldwin Ministry had not been a year in existence when it became apparent that more was expected from it than was likely to be realized. As time wore on, men listened in vain for any response to the demand that the Clergy Reserves should be secularized. The violent opposition to the Rebellion Losses Bill, by uniting the supporters of the Government, arrested the forces of disintegration for a while. In 1851 they again acquired activity. After the retirement of the two leaders of the double-headed Government this year, and after Mr. Hincks had become premier, all hope of preventing a disruption of the Reform party was gone. At the head of one section was Mr. Brown; at the head of the other the First Minister. Besides this Pg 11 new opposition, the Government encountered the whole force of the Conservative party. Against an opposition composed of two distinct sections the Government was able to bear up till the close of 1853; but it was evident that its doom was soon to be pronounced. The two opposite parties, which had casually united in the House, had reason to expect greater results from their union in the constituencies; and they were not disappointed. Their united forces served to rout the Government party, and win for themselves a victory at the polls. The coalition in the constituencies was destined to be reproduced in the House, but not in the same form. The defeated wing of the Reform party took the place which the successful wing might have been expected to take in the new Coalition. Mr. Macdonald now, for the first time, obtained an office which was directly in the line of his profession, the Attorney-Generalship. To these events the McNab-Morin Coalition owed its birth; and of that Coalition Mr. Macdonald had become a member. Numerous were the speculations as to which wing of the Coalition would ultimately prevail over the other; whether the balance would incline in favour of the Conservative or the Reform section. At first, judging by the programme carried out, a stranger might have thought the Reformers held full sway; but a closer inspection would have revealed the fact that the real control was in the Conservatives. To that result the tact and ability of Mr. Macdonald contributed in no small degree.

Though Sir John had always been a Conservative, his name was henceforth to become connected with several measures of Reform. The connection has generally been that of a passive recipient, not of a persistent advocate. If we except the adjustment of the mere mechanism of the Government, it must be allowed that the two greatest Reform measures that have been passed, in this country, are the abolition of the Feudal Tenure of Lower Canada, and the secularization of the Clergy Reserves. These measures, which the Lafontaine-Baldwin Government refused to initiate or accept, were carried by the Coalition of which Sir John was a member. The part acted by the Coalition was to carry out a pre-concerted programme; a programme framed by the party that had been beaten in the election. Nothing but the conviction that the last battle over the Clergy Reserves which there had been the slightest chance of winning had been fought, coupled with a stern sense of duty, induced some members of the Conservative section to vote for secularization. The voice of the country had so often been heard declaring for secularization that further resistance was out of the question. The Conservative section, including Sir John, accepted the inevitable, some of them with visible signs of painful regret. The policy of conforming to public opinion under such circumstances, had no terrors for Sir John; it pointed to the line that he would naturally follow. So completely dead was the Feudal Tenure of Lower Canada that it retained no real support even in Conservative opinion. The last argument made, against abolition was the argument of an advocate retained by the Seigniors, at the bar of the House. For such a reform Sir John was quite prepared, and he accepted it with a good will.

Good faith required that the abolition of the Seignorial Tenure should not assume the character of a spoliation of the Seigniors, and that the life claims of those in possession of the Clergy Reserves should be respected. The Coalition was in a good position to do the special work of securing these guarantees, and it was done with substantial justice to all parties. Sir John bore his part in this work with courage and success. The practical carrying out of these two great reforms was thus tempered with Pg 12 a spirit of conservative justice, conservative not in a party sense, but in the sense of commuting vested rights, pecuniarily beneficial to individuals, in the act of decreeing their abolition in the public interest.

On another question, which formed an item in this programme—an elective second chamber—Sir John has shown that, under different circumstances, he could be equally ready to recede or to advance. The change from nomination to election was voted with an approach to unanimity seldom witnessed in the Legislative Assembly; there being but one dissentient voice. When the bases of Confederation came to be laid, this step was retraced, and nomination revived. The reaction was not the work or the fault of an individual; it was due to the accession of Provinces in which the affection for nomination had not lost its influence.

Till the year 1856, Sir John nominally occupied only a secondary position in his party and his Province. Sir Allan McNab was, by right of seniority and possession, the Upper Canada leader of the Conservatives; by right of the strongest, it at last came to belong to Sir John. Repeated attacks of gout made it evident to all observers that as leader Sir Allan must soon give place to another; and it was well understood that he was desirous that Mr. Hillyard Cameron should be his successor. Mr. Cameron was apparently as anxious to obtain as Sir Allan was to secure for him a reversionary interest in the leadership. Sir John and Mr. Cameron, both members of the same party, came to be looked upon as rivals. Mr. Cameron, miscalculating the power of the press when employed for the promotion of individual aims, made arrangements which converted the Colonist into a personal organ; but his chances of succeeding to the leadership were rather lessened than increased by his costly expedient, in which he is believed to have laid out forty thousand dollars; for other and more influential journals took up the cause of his rival. Whatever may have been the effect of these extraneous influences, Sir John was to win by the force of his own inherent qualities. In the spring of this year Sir Allan McNab was suffering from a prolonged attack of his old enemy, the gout. Parliament was in session, and the continued absence from the House of the leader of the Government was a source of daily embarrassment. A section of the ministerial supporters, becoming impatient, declared Sir John their leader; and a crisis was brought about which compelled the valetudinarian minister to resign. He threw the blame on Sir John, and gave free vent to his indignation; having been almost carried to his seat for that purpose, when the ministerial explanations were made. Sir John succeeded naturally, and without any further contest, to the leadership of the Upper Canada Conservatives, which he has retained for a period of twenty-five years.

Like all public men, Sir John Macdonald has sometimes found it necessary to defer to the opinions of colleagues, in which he did not share. Against the policy of what is known as the double-shuffle, in 1858, his own opinion was unequivocal. But he took the responsibility of the course which his colleagues were anxious to pursue. A few words will describe the double-shuffle. A Government which had been formed, with Mr. Brown for its Upper Canada, and Mr. Dorian for its Lower Canada chief, encountering a hostile vote in a House elected under the auspices of their opponents, retired, and the Conservatives came back to office. Under cover of a law passed to enable any minister to change from one executive office to another without the necessity of reëlection, all the Ministers, in going back, temporarily took offices which they did not intend to hold, for the mere purpose of being Pg 13 able to evade the ordeal of the constituencies by making a wholesale exchange. Although it was quite clear that the framers of the Act never contemplated such a contingency, the wording would bear the construction on which Ministers acted; and so the courts held. But Sir John was not proud of the victory, the result of which was a moral gain for the Opposition. The effect was to produce a profound impression on his mind that he was never safe in acting against his own better judgement.

In Lower Canada, Sir George Cartier was the coming man; and in him Sir John found not only a trusty colleague but a firm personal friend. Their friendship lasted many years, but was once interrupted before the death of Sir George, and was probably never so cordial as before. It was a trivial thing that snapped asunder what was apparently one of the strongest bonds that ever united two personal and political friends. In the distribution of imperial honours among those who had taken a prominent part in bringing about a federal union of the Provinces, Sir George considered himself slighted, and he attributed that slight to the advice of his colleague. Sir John did what he could to heal the wound which had been given to Sir George's susceptibilities, by recommending him for a higher mark of distinction than he had himself received. But the broken glass was not to be restored to its former condition. Sir John, accepting knighthood for himself, obtained a baronetcy for his colleague. But the difficulty was that he took imperial honours for himself first, and only obtained imperial honours for his colleague after the latter had given vent to the bitterness of his indignation at the disappointment Both transactions serve to illustrate the character of Sir John. He feels that he is entitled to the first consideration among colleagues; and he will make concessions under political pressure that he would not voluntarily make if he were free.

To Sir George Cartier, Sir John Macdonald owed the majorities by which he carried on his Government. Lower Canada, with a population which, at the time of the union, had been much greater than that of the other Province, and which has now become inferior in numbers, thought her safety consisted in retaining an equal number of representatives; while Upper Canada insisted that the representation ought to bear a fair proportion to the respective populations. On this question, Lower Canada was long a unit; and Sir George Cartier, rowing with the stream, was assured of his majority. In Upper Canada, Sir John Macdonald, buffeting the waves of a fast rising tide, went back to the House from each succeeding election with a diminished majority. His whole parliamentary strength came through Sir George Cartier; and it is not surprising if the latter was able to exact favourable terms for his Province. By the nature of his position, Sir John was condemned to be, in one sense, an unpopular ruler in his own Province. From this disability, Confederation, by removing the irritation caused by a galling sense of inadequate representation, rescued him; and, as the last general election to the House of Commons showed, there is now no reason why he should not command a majority in any Province of the Dominion. If, in presence of the large majority obtained, we are to suppose the recollection of the Pacific scandal in any degree weakened his strength in the constituencies, it will be understood how much he lost in former times by the sense of inadequate representation under which Upper Canada smarted. Why then did he cling to a losing cause? The truth is, no one could see whence a remedy was to come; for not a single Lower Canada vote could be got in favour of changing the basis of the representation. Confederation changed the issue. Numerical representation was not the same thing when applied to four Provinces—that being Pg 14 the original number—under a federation, that it was when applied to two Provinces, one of which had a large majority of inhabitants of French and the other a large majority of English speaking people, under a legislative union. Besides, there is a time for all things; and it is very doubtful whether Confederation could have been brought about even a single year sooner than it was. Sir John Macdonald was one of that large number of persons who opposed great constitutional changes till the necessity for them had been fully demonstrated, and a majority of the electors who had to be consulted had become convinced that there was no longer anything to be gained by further delay. He was not a convert to representation of numbers during the many years it found advocates even in the ranks of his own party; he was not in favour of Confederation when it was first mooted; but when the time came that the change could be made with advantage, his objections were put aside, and he was one of its foremost advocates. Here we get a glimpse of the line where his conservatism ends and his readiness to reform begins. He will not consent to be hurried; but no one can say that; on any given question, his finality of to-day may not be his starting point at some future time.

Though born on the other side of the water, Sir John Macdonald may be called a Canadian; for that is a man's country where his mind is formed and attains maturity. And take him all in all, his faults and his virtues, his weaknesses and his public services, his figure occupies a larger space than that of any other public man on the stage of Canada; and to him we should have to point if obliged to select the most distinguished son of this Dominion. In many particulars, others leave him far behind, but, taken all in all, he stands unrivalled. His enemies delight to dwell on his blemishes and magnify his faults. As our aim is to act in a judicial spirit, we are obliged to touch on the weaknesses of our foremost statesman; but we have no pleasure in the task. The Pacific scandal has been condoned, but it has not been and cannot be justified. As leader of the Government, Sir John Macdonald took, for party election purposes, large sums of money from Sir Hugh Allan, who had an Atlantic mail contract with the Government, and was to get the contract for building the Pacific Railway. These sums were altogether too large to be regarded as ordinary contributions from a supporter of the Government towards a fund for election purposes, and they were too large to be consistent with the supposition that they were to be employed only for legal purposes. Coming from a person who had one contract with the Government and was on the point of getting another, the natural inference is that they represented an undefined and indefinite assessment on the profits of the actual or the prospective contract, or both; that the giver was in effect purchasing or paying for favours which the Government had then or previously had it in its power to withhold; and that, in this way, the Government could, indirectly, take so much money out of the public treasury for party election purposes. It has been said, in excuse, that Sir John Macdonald became the custodian of this election fund, in default of such party machinery as exists in other countries for that purpose. The answer is that a change of the custodian, though it might have veiled the transaction, would not have altered its character. It is quite true that electoral corruption was not the exclusive weapon of any party. But no one would give such large sums as Sir Hugh gave, unless he were dealing with the Government, and expected to be recouped by contracts of which the Government had the disposal. Bribery is bribery, whether the sum be large or small; the briber is equally Pg 15 guilty of a crime whether he operate on a large or a small scale; but he who gives his own money commits one crime the less than he who takes the money he distributes in bribes indirectly out of the public treasury, through the forms of a contract. We make these statements with a sense of pain; for it is duty and not pleasure that causes us to point to the stain on the robe of the statesman whom, in spite of this fault, the electorate of Canada have found reasons for placing in the highest position of trust which it is their prerogative to confer.

Although we place Sir John Macdonald in the highest niche reserved for our public men, we are far from saying that there may not be, even now, in public life in Canada men who may not live to make a higher mark than he has been able to reach. Twenty-seven years ago, he was the best debater in the House with the exception of Sir Francis Hincks; he lived to distance all others in this particular; but, if he has not already lost this pre-eminence, the sceptre is visibly passing over to the left of the Speaker. As a speaker, distinguished from a debater, Sir John has steadily improved, and his latest efforts are the best. He will be remembered as the author of three great speeches, whatever may become of his other efforts in that line: the first on the Treaty of Washington; the second in his own defence when the Pacific scandal charges were before the House; the third on the Letellier case. On the two former occasions he spoke with the embarrassment of a man under accusation. He had assisted in making a treaty in which, in the general belief, the interests of Canada had been sacrificed to Imperial considerations. When he was appointed one of the English Commissioners, it was too hastily assumed that he represented Canada in some special manner. But it was England, not Canada, that was making the treaty, and the negotiators were acting in strict accordance with the instructions of the British Cabinet. Sir John received his appointment from the British Government, and by their instructions he was bound to be guided. Whether he ought to have placed himself in this position may be a question. But he could furnish important local information to his colleagues with which they could not, on the instant, have furnished themselves. He might argue in favour of Canadian claims; and though what he did do, in this particular, the protocols tell not, it is no secret that he did not please the British Government. The Fenian claims were excluded, assuredly by no fault of his; the omission it was not in his power to prevent. But he got in lieu of direct payment an Imperial guarantee of a Canadian loan which served to lessen the cost of our railway expenditure; and no one will now undertake to say that, under the operation of that treaty, we have not been liberally paid for the concession to the Americans of the rights to fish on our coasts. On the whole, the Washington Treaty has proved much less injurious than it was feared it would. In any case, the responsibility for that treaty rests with the British Government. So long as treaties binding on Canada are made by a Government not her own, they will be likely to be more favourable to that Government than to her.

The speech on the Pacific scandal was a great effort, without being a great success. But it showed the power and resource of the speaker better than they had ever been shown before, except, perhaps, on the one occasion before mentioned. The speech on the Letellier case, whether the ground taken was right or wrong, showed that he possessed the faculty of grasping the full import of difficult constitutional questions.

Whatever estimate may be formed of Sir John as a constitutional lawyer, the fact remains that the ground he takes on constitutional questions generally proves, in the end, to be the true one. This can hardly be Pg 16 the result of accident or lucky blundering. The man who generally gives a correct opinion on constitutional questions cannot be an indifferent or unfair constitutional lawyer. Some critics have taken the ground that Sir John has no convictions on the question of the National Policy; that, wanting a cry, and finding this one ready to his hand, he utilized it without any regard to his own real opinions. This is certainly an error. He is known to have entertained, for twenty years, views similar to those on which his Government has now acted. But he was too busy most of the time to engage in the work of agitation: he waited till a maturing opinion filled the sails of the vessel on which he had, at any time, been ready to embark. He believed that the abolition of the protective system, under which the colonies had grown up and prospered, would deal a severe blow at their prosperity; though he did not concur with the opinion despondingly expressed by Lord Cathcart in a despatch written, in 1846, in his capacity of Governor-General, that the political consequences would be the alienation of Canada from the mother country and its annexation to the United States. On the question of a national tariff policy, Sir John has never held but one opinion. He may not be the most profound of political economists—it would be difficult to point to any of our public men who are—but no statesman would perform his whole duty if he confined himself to carrying out the prescriptions of the political economists. A nation has other and higher interests that demand consideration.

The result of the electoral battle of 17th September, 1878, which brought Sir John back to power, had not been universally foreseen. That the National Policy had a large share in bringing it about, is beyond question; though there were, no doubt, by-currents that helped to swell the main stream. Expectation had risen beyond the possibility of fulfilment. Whether, in the face of revenue necessities, this policy can ever be completely reversed, is doubtful; though it may be taken for granted that the ballot-box is pregnant with surprises not less startling than that of September. That Sir John is premier to-day is proof of the high estimate in which the country holds his abilities, and that on his shortcomings it is willing to look with an indulgent, if regretful eye. Out of respect for the magnitude and importance of his public services, posterity will not grudge him a high place in the Canadian Pantheon.

The life of Robert Baldwin forms so important an ingredient in the political history of this country that we deem it unnecessary to offer any apology for dealing with it at considerable length. More especially is this the case, inasmuch as, unlike most of the personages included in the present series, his career is ended, and we can contemplate it, not only with perfect impartiality, but even with some approach to completeness. The twenty and odd years which have elapsed since he was laid in his grave have witnessed many and important changes in our Constitution, as well as in our habits of thought; but his name is still regarded by the great mass of the Canadian people with feelings of respect and veneration. We can still point to him with the admiration due to a man who, during a time of the grossest political corruption, took a foremost part in our public affairs, and who yet preserved his integrity untarnished. We can point to him as the man who, if not the actual author of Responsible Government in Canada, yet spent the best years of his life in contending for it, and who contributed more than any other person to make that project an accomplished fact. We can point to him as one who, though a politician by predilection and by profession, never stooped to disreputable practices, either to win votes or to maintain himself in office. Robert Baldwin was a man who was not only incapable of falsehood or meanness to gain his ends, but who was to the last degree intolerant of such practices on the part of his warmest supporters. If intellectual greatness cannot be claimed for him, moral greatness was most indisputably his. Every action of his life was marked by sincerity and good faith, alike towards friend and foe. He was not only true to others, but was from first to last true to himself. His useful career, and the high reputation which he left behind him, furnish an apt commentary upon the advice which Polonius gives to his son Laertes;—

To our thinking there is something august in the life of Robert Baldwin. So chary was he of his personal honour that it was next to impossible to induce him to pledge himself beforehand, even upon the plainest question. Once, when addressing the electors at Sharon, some one in the crowd asked him if he would pledge himself to oppose the retention of the Clergy Reserves. “I am not here,” was his reply, “to pledge myself on any question. I go to the House as a free man, or I go not at all. I am here to declare to you my opinions. If you approve of my opinions, and elect me, I will carry them out in Parliament. If I should alter those opinions I will come back and surrender my trust, when you will have an opportunity of reëlecting me or of choosing Pg 18 another candidate; but I shall pledge myself at the bidding of no man.” A gentleman still living in Toronto once accompanied him on an electioneering tour into his constituency of North York. There were many burning questions on the carpet at the time, on some of which Mr. Baldwin's opinion did not entirely coincide with that of the majority of his constituents. His companion remembers hearing it suggested to him that his wisest course would be to maintain a discreet silence during the canvass as to the points at issue. His reply to the suggestion was eminently characteristic of the man.

“To maintain silence under such circumstances,” said he, “would be tantamount to deceiving the electors. It would be as culpable as to tell them a direct lie. Sooner than follow such a course I will cheerfully accept defeat.” He could not even be induced to adopt the suppressio veri. So tender and exacting was his conscience that he would not consent to be elected except upon the clearest understanding between himself and his constituents, even to serve a cause which he felt to be a just one. Defeat might annoy, but would not humiliate him. To be elected under false colours would humiliate him in his own esteem; a state of things which, to a high-minded man, is a burden intolerable to be borne.

It has of late years become the fashion with many well-informed persons in this country to think and speak of Robert Baldwin as a greatly over-estimated man. It is on all hands admitted that he was a man of excellent intentions, of spotless integrity, and of blameless life. It is not disputed, even by those whose political views are at variance with those of the party to which he belonged, that the great measures for which he contended were in themselves conducive to the public weal, nor is it denied that he contributed greatly to the cause of political freedom in Canada. But, it is said, Robert Baldwin was merely the exponent of principles which, long before his time, had found general acceptance among the statesmen of every land where constitutional government prevails. Responsible Government, it is said, would have become an accomplished fact, even if Robert Baldwin had never lived. Other much-needed reforms with which his name is inseparably associated would have come, it is contended, all in good time, and this present year, 1880, would have found us pretty much where we are. To argue after this fashion is simply to beg the whole question at issue. It is true that there is no occult power in a mere name. Ship-money, doubtless, was a doomed impost, even if there had been no particular individual called John Hampden. The practical despotism of the Stuart dynasty would doubtless have come to an end long before the present day, even if Oliver Cromwell and William of Orange had never existed. In the United States, slavery was a fated institution, even if there had been no great rebellion, and if Abraham Lincoln had never occupied the Presidential chair. But it would be a manifest injustice to withhold from those illustrious personages the tribute due to their great and, on the whole, glorious lives. They were the media whereby human progress delivered its message to the world, and their names are deservedly held in honour and reverence by a grateful posterity. Performing on a more contracted stage, and before a less numerous audience, Robert Baldwin fought his good fight—and won. Surrounded by inducements to prove false to his innate convictions, he nevertheless chose to encounter obloquy and persecution for what he knew to be the cause of truth and justice.

says Professor Lowell. The moment came to Robert Baldwin early in life. It is not Pg 19 easy to believe that he ever hesitated as to his decision; and to that decision he remained true to the latest hour of his existence. If it cannot in strictness be said of him that he knew no variableness or shadow of turning, it is at least indisputable that his convictions never varied upon any question of paramount importance. What Mr. Goldwin Smith has said of Cromwell might with equal truth be applied to Robert Baldwin: “He bore himself, not as one who gambled for a stake, but as one who struggled for a cause.” These are a few among the many claims which Robert Baldwin has upon the sympathies and remembrances of the Canadian people; and they are claims which we believe posterity will show no disposition to ignore.

In order to obtain a clear comprehension of the public career of Robert Baldwin it is necessary to glance briefly at the history of one or two of his immediate ancestors. In compiling the present sketch the writer deems it proper to say that he some time since wrote an account of Robert Baldwin's life for the columns of an influential newspaper published in Toronto. That account embodied the result of much careful and original investigation. It contained, indeed, every important fact readily ascertainable with reference to Mr. Baldwin's early life. So far as that portion of it is concerned there is little to be added at the present time, and the writer has drawn largely upon it for the purposes of this memoir. The former account being the product of his own conscientious labour and investigation, he has not deemed it necessary to reconstruct sentences and paragraphs where they already clearly expressed his meaning. With reference to Mr. Baldwin's political life, however, the present sketch embodies the result of fuller and more accurate information, and is conceived in a spirit which the exigencies of a newspaper do not admit of.

At the close of the Revolution which ended in the independence of the United States, there resided near the city of Cork, Ireland, a gentleman named William Willcocks. He belonged to an old family which had once been wealthy, and which was still in comfortable circumstances. About this time a strong tide of emigration set in from various parts of Europe to the New World. The student of history does not need to be informed that there was at this period a good deal of suffering and discontent in Ireland. The more radical and uncompromising among the malcontents staid at home, hoping for better times, and many of them eventually took part in the troubles of '98. Others sought a peaceful remedy for the evils under which they groaned, and, bidding adieu to their native land, sought an asylum for themselves and their families in the western wilderness. The success of the American Revolution combined with the hard times at home to make the United States “the chosen land” of many thousands of these self-expatriated ones. The revolutionary struggle was then a comparatively recent affair. The thirteen revolted colonies had become an independent nation, had started on their national career under favourable auspices, and had already become a thriving and prosperous community. The Province of Quebec, which then included the whole of what afterwards became Upper and Lower Canada, had to contend with many disadvantages, and its condition was in many important respects far behind that of the American Republic. Its climate was much more rigorous than was that of its southern neighbour, and its territory was much more sparsely settled. The western part of the Province, now forming part of the Province of Ontario, was especially thinly peopled, and except at a few points along the frontier, was little better than a wilderness. It was manifestly desirable to offer strong incentives to immigration, with a view to the speedy settlement of the Pg 20 country. To effect such a settlement was the imperative duty of the Government of the day; and to this end, large tracts of land were allotted to persons whose settlement here was deemed likely to influence colonization. Whole townships were in some cases conferred, upon condition that the grantees would settle the same with a certain number of colonists within a reasonable time. One of these grantees was the William Willcocks above-mentioned, who was a man of much enterprise and philanthropy. He conceived the idea of obtaining a grant of a large tract of land, and of settling it with emigrants of his own choosing, with himself as a sort of feudal proprietor at their head. With this object in view he came out to Canada in or about the year 1790, to spy out the land, and to judge from personal inspection which would be the most advantageous site for his projected colony. In setting out upon this quest he enjoyed an advantage greater even than was conferred by his social position. A cousin of his, Mr. Peter Russell, a member of the Irish branch of the Bedfordshire family of Russell, had already been out to Canada, and had brought home glowing accounts of the prospects held out there to persons of capital and enterprise. Mr. Russell had originally gone to America during the progress of the Revolutionary War, in the capacity of Secretary to Sir Henry Clinton, Commander-in-chief of the British forces on this continent. He had seen and heard enough to convince him that the acquisition of land in Canada was certain to prove a royal road to wealth. After the close of the war he returned to the old country, and gave his relatives the benefit of his experience. Mr. Russell also came out to Canada with Governor Simcoe in 1792, in the capacity of Inspector-General. He subsequently held several important offices of trust in Upper Canada. He became a member of the Executive Council, and as senior member of that body the administration of the Government devolved upon him during the three years (1796-1799) intervening between Governor Simcoe's departure from Canada and the appointment of Major-General Peter Hunter as Lieutenant-Governor. His residence in Canada, as will presently be seen, was destined to have an important bearing on the fortunes of the Baldwin family. Meanwhile, it is sufficient to note the fact that it was largely in consequence of the valuable topographical and statistical information furnished by him to his cousin William Willcocks that the latter was induced to set out on his preliminary tour of observation.

The result of this preliminary tour was to convince Mr. Willcocks that his cousin had not overstated the capabilities of the country, as to the future of which he formed the most sanguine expectations. The next step to be taken was to obtain his grant, and, as his political influence in and around his native city was considerable, he conceived that this would be easily managed. He returned home, and almost immediately afterwards crossed over to England, where he opened negotiations with the Government. After some delay he succeeded in obtaining a grant of a large tract of land; forming part of the present township of Whitchurch, in the county of York. In consideration of this liberal grant he on his part agreed to settle not fewer than sixty colonists on the land so granted within a certain specified time. An Order in Council confirmatory of this arrangement seems to have been passed. The rest of the transaction is involved in some obscurity. Mr. Willcocks returned to Ireland, and was soon afterwards elected Mayor of Cork—an office which he had held at least once before his American tour. Municipal and other affairs occupied so much of his time that he neglected to take steps for settling his trans-Atlantic domain until the period allowed Pg 21 him by Government for that purpose had nearly expired. However, in course of time—probably in the summer of 1797—he embarked with the full complement of emigrants for New York, whither they arrived after a long and stormy voyage. They pushed on without unnecessary delay, and in due course arrived at Oswego, where Mr. Willcocks received the disastrous intelligence that the Order in Council embodying his arrangement with the Government had been revoked. Why the revocation took place does not appear, as there had been no change of Government, and the circumstances had not materially changed. Whatever the reason may have been, the consequences to Mr. Willcocks and his emigrants were very serious. The poor Irish families who had accompanied him to the New World—travel-worn and helpless, in a strange land, without means, and without experience in the hard lines of pioneer life—were dismayed at the prospect before them. Mr. Willcocks, a kind and honourable man, naturally felt himself to be in a manner responsible for their forlorn situation. He at once professed his readiness to bear the expense of their return to their native land. Most of them availed themselves of this offer, and made the best of their way back to Ireland—some of them, doubtless, to take part in the rising of '98. A few of them elected to remain in America, and scattered themselves here and there throughout the State of New York. Mr. Willcocks himself, accompanied by one or two families, continued his journey to Canada, where he soon succeeded in securing a considerable allotment of land in Whitchurch and elsewhere. It is probable that he was treated liberally by the Government, as his generosity to the emigrants had greatly impoverished him, and it is certain that a few years later he was the possessor of large means. Almost immediately after his arrival in Canada he took up his abode at York, where he continued to reside down to the time of his death. Being a man of education and business capacity he was appointed Judge of the Home District Court, where we shall soon meet him again in tracing the fortunes of the Baldwin family. He had not been long in Canada before he wrote home flattering reports about the land of his adoption to his old friend Robert Baldwin, the grandfather of the subject of this sketch. Mr. Baldwin was a gentleman of good family and some means, who owned and resided on a small property called Summer Hill, or Knockmore, near Carragoline, in the county of Cork. Influenced by the prospects held out to him by Mr. Willcocks, he emigrated to Canada with his family in the summer of 1798, and settled on a block of land on the north shore of Lake Ontario, in what is now the township of Clarke, in the county of Durham. He named his newly-acquired estate Annarva (Ann's Field), and set about clearing and cultivating it. The western boundary of his farm was a small stream which until then was nameless, but which has ever since been known in local parlance as Baldwin's Creek. Here he resided for a period of fourteen years, when he removed to York, where he died in the year 1816. He had brought with him from Ireland two sons and four daughters. The eldest son, William Warren Baldwin, was destined to achieve considerable local renown as a lawyer and a politician. He was a man of versatile talents, and of much firmness and energy of character. He had studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and had graduated there two years before his emigration, but had never practised his profession as a means of livelihood. He had not been many weeks in this country before he perceived that his shortest way to wealth and influence was by way of the legal rather than the medical profession. In those remote times, men of education and mental ability were by no means numerous in Upper Canada. Pg 22 Every man was called upon to play several parts, and there was no such organization of labour as exists in older and more advanced communities. Dr. Baldwin resolved to practise both professions, and, in order to fit himself for the one by which he hoped to rise most speedily to eminence, he bade adieu to the farm on Baldwin's Creek and came up to York. He took up his quarters with his father's friend and his own, Mr. Willcocks, who lived on Duke street, near the present site of the La Salle Institute. In order to support himself while prosecuting his legal studies, he determined to take in a few pupils. In several successive numbers of the Gazette and Oracle—the one newspaper published in the Province at that time—we find in the months of December, 1802, and January, 1803, the following advertisement:—“Dr. Baldwin, understanding that some of the gentlemen of this town have expressed some anxiety for the establishment of a Classical School, begs leave to inform them and the public, that he intends, on Monday the 1st day of January next, to open a school, in which he will instruct Twelve Boys in Writing, Reading, Classics and Arithmetic. The terms are, for each boy, eight guineas per annum, to be paid quarterly or half-yearly; one guinea entrance and one cord of wood to be supplied by each of the boys on opening the School. N.B.—Mr. Baldwin will meet his pupils at Mr. Willcocks' house on Duke street. York, December 18th, 1802.” This advertisement produced the desired effect. The Doctor got all the pupils he wanted, and several youths who in after life rose to high eminence in the colony received their earliest classical teaching from him.

It was not necessary at that early day that a youth should spend a fixed term in an office under articles as a preliminary for practice, either at the Bar or as an attorney. On the 9th of July, 1794, during the regime of Governor Simcoe, an Act had been passed authorizing the Governor, Lieutenant-Governor, or person administering the Government of the Province, to issue licenses to practise as advocates and attorneys to such persons, not exceeding sixteen in number, as he might deem fit. We have no means of ascertaining how many persons availed themselves of this statute, as no complete record of their names or number is in existence. The original record is presumed to have been burned when the Houses of Parliament were destroyed during the American invasion in 1813. It is sufficient for our present purpose to know that Dr. Baldwin was one of the persons so licensed. By reference to the Journals of the Law Society at Osgoode Hall, we find that this license was granted on the 6th of April, 1803, by Lieutenant-Governor Peter Hunter. We further find that on the same day similar licenses were granted to four other gentlemen, all of whom were destined to become well-known citizens of Canada, viz., William Dickson, D'Arcy Boulton, John Powell, and William Elliott. Dr. Baldwin, having undergone an examination before Chief Justice Henry Alcock, and having received his license, authorizing him to practise in all branches of the legal profession, married Miss Phœbe Willcocks, the daughter of his friend and patron, and settled down to active practice as a barrister and attorney. He took up his abode in a house which had just been erected by his father-in-law, on what is now the north-west corner of Front and Frederick streets. [It may here be noted that Front street was then known as Palace street, from the circumstance that it led down to the Parliament buildings at the east end of the town, and because it was believed that the official residence or “palace” of the Governor would be built there.] Here on the 12th of May, 1804, was born Dr. Baldwin's eldest son, known to Canadian history as Robert Baldwin. Pg 23