* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Wonder of All the Gay World

Date of first publication: 1949

Author: James William Barke (1905-1958)

Date first posted: Apr. 16, 2015

Date last updated: Apr. 16, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20150421

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE WONDER OF ALL THE GAY WORLD

By the same author

Novels

THE WELL OF THE SILENT HARP

THE SONG IN THE GREEN THORN TREE

THE WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY

THE LAND OF THE LEAL

MAJOR OPERATION

THE END OF THE HIGH BRIDGE

THE WILD MACRAES

THE WORLD HIS PILLOW

Autobiography

THE GREEN HILLS FAR AWAY

THE WONDER OF

ALL THE GAY WORLD

A Novel of

the Life and Loves

of

Robert Burns

by

JAMES BARKE

COLLINS ST. JAMES’S PLACE LONDON

| FIRST IMPRESSION | AUGUST, 1949 |

| SECOND IMPRESSION | SEPTEMBER, 1949 |

| THIRD IMPRESSION | JANUARY, 1953 |

| FOURTH IMPRESSION | OCTOBER, 1956 |

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

COLLINS CLEAR-TYPE PRESS: LONDON AND GLASGOW

TO

JOHN DeLANCEY FERGUSON

‘Friend of the Poet tried and leal’

In admiration and gratitude

IMMORTAL MEMORY

comprises

THE WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY

THE SONG IN THE GREEN THORN TREE

THE WONDER OF ALL THE GAY WORLD

THE CREST OF THE BROKEN WAVE

THE WELL OF THE SILENT HARP

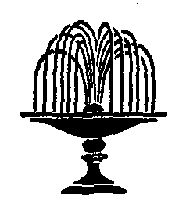

MAP OF BURNS TRAVEL ROUTE THROUGH SCOTLAND AND ENGLAND

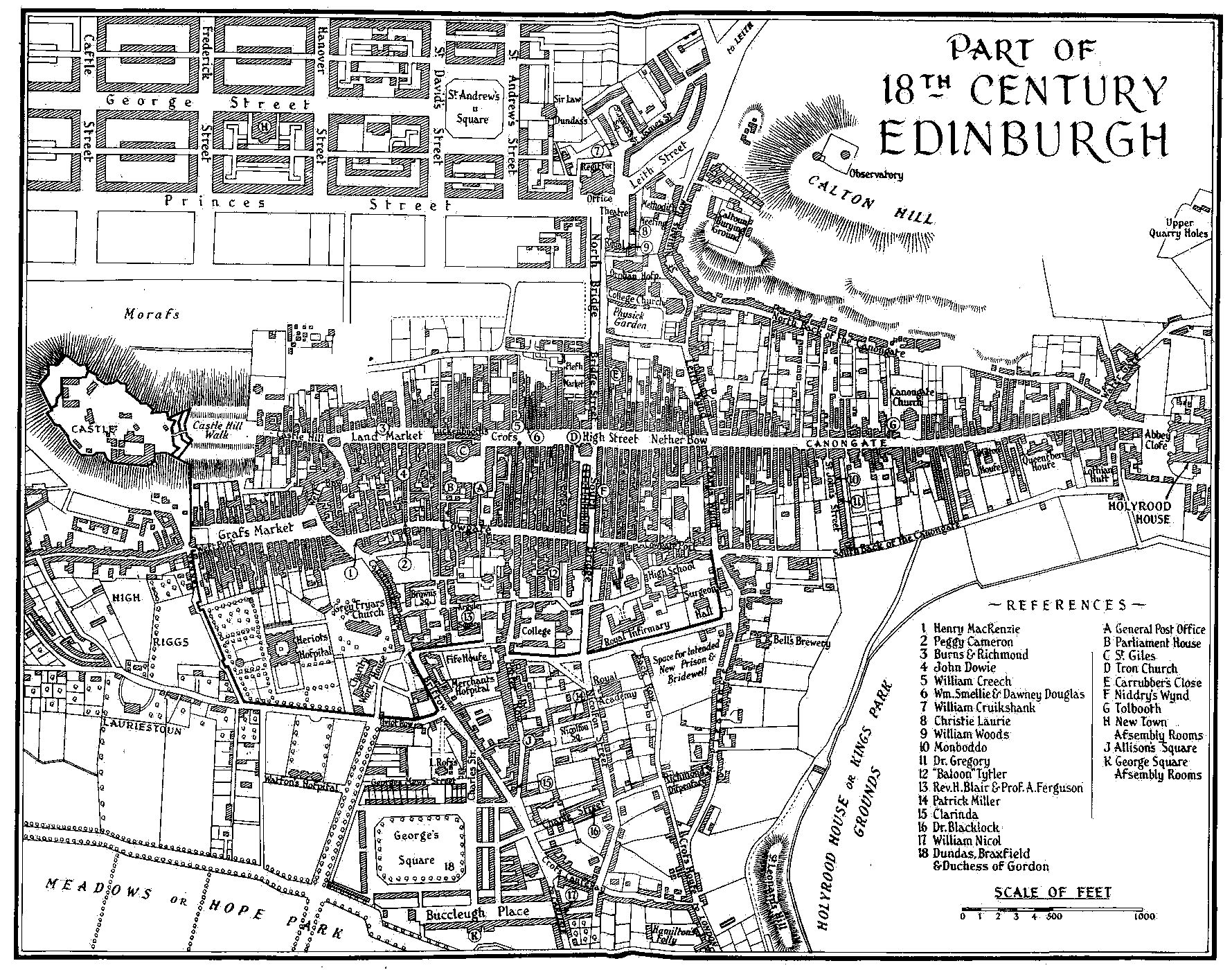

MAP OF 18th CENTURY EDINBURGH

Burns’s Edinburgh days (November, 1786-March, 1788) were the most crucial days of his life. Perhaps for this reason the biographers have accorded them scant attention. Or perhaps they shirked the labour involved in uncovering the facts of this period. But, whatever the reason, the reader ‘hot for certainties’ concerning Burns’s life in Edinburgh gets a decidedly ‘dusty answer’ from every biographer.

But, though the novelist can get much closer to life (and hence truth) than the biographer, the best he can do is to reflect life in its odd moments. He can however select his odd moments from the flux of time. I have made my selections with such care and honesty as I possess; and the reader may be assured that no vital fact has been suppressed deliberately.

If there is no account, for example, of the meeting between Burns and the young Walter Scott, the reason is that there is no proof that the meeting ever took place. Indeed such proof as does exist (and it is considerable) decisively explodes the legend.

If I have identified Christina Laurie as the recipient of the “My dear countrywoman” letter and not Margaret Chalmers (as the historians have hitherto done) it is because the available evidence is slightly in Christie’s favour. But I am conscious of the fact that in giving her the benefit of the doubt I have here, willy-nilly, removed it.

And so with Jenny Clow. There is insufficient evidence to assert without fear of future contradiction that she was Clarinda’s maid. But that she was a poor Edinburgh lass who stood in some such relation to Clarinda is vouched for both by Burns and Clarinda. Since this is the only conclusion that makes sense I have adopted it without undue misgiving.

With these indications of where I may have parted from the strict tenets of historical accuracy I leave the remaining facts to speak for themselves.

For facilitating my fact-finding labours I gladly acknowledge debts to the following: Mr. Robert Butchart and Miss Balfour, Edinburgh Public Libraries; Mr. W. J. Murison of Duns Public Library for taking up the history of Cimon Gray with rare enthusiasm and intriguing results; Mr. and Mrs. R. Rae Hogarth of Stodrig House, Kelso, for doing me the honours of the house once occupied by Burns’s Border host, Gilbert Ker; and to Mr. “Topaz” Hogg of Fochabers in his role of incomparable guide, and piquant philosopher, around bonnie Castle Gordon. I am also under a special debt of gratitude to Mr. James Campbell of The Mitchell Library, Glasgow.

To the erudite contributors to the publications of the Old Edinburgh Club it is difficult adequately to express thanks; I have drawn heavily on their brilliant research work.

Lastly: the dedication of this book to Professor Ferguson is but a token acknowledgment of my indebtedness to him, not only for sharing with me his unequalled knowledge of Burns but for his advice and guidance. This does not necessarily imply that Professor Ferguson is in any way committed to my portrait of Burns and his contemporaries. Nor does his published work on Burns need any suggestion of endorsement by me. But I welcome the opportunity of expressing gratitude for his indispensable public labours and his many private kindnesses.

J.B.,

Daljarrock House, Ayrshire.

November 3rd, 1948.

| page | |

| MAP OF BURNS TRAVEL ROUTE THROUGH SCOTLAND AND ENGLAND | 5 |

| MAP OF 18TH CENTURY EDINBURGH | 6 |

| NOTES | 7 |

| CHARACTERS | 14 |

| THE CUP OF FAME | |

| Grey Daylight | 23 |

| Patron | 47 |

| Publisher | 48 |

| Printer | 56 |

| Thin Ice | 62 |

| Scotia’s Darling Seat | 71 |

| The Tenth Worthy | 86 |

| The Edinburgh Gentry | 90 |

| The Bard and the Bishop | 109 |

| Henry MacKenzie’s Verdict | 122 |

| The Offer of Patrick Miller | 126 |

| Letters to Ayr | 131 |

| Substitutes | 133 |

| James Sibbald | 144 |

| Verdicts | 148 |

| The Caddie’s Advice | 152 |

| Corporal Trim’s Hat | 154 |

| Balloon Tytler | 159 |

| The Portrait Painter | 164 |

| Dundas and Braxfield | 167 |

| The Men of Letters | 173 |

| The Bubble of Fame | 177 |

| Lowland Peggy | 178 |

| Letter to John Ballantine | 187 |

| The Friend of Fergusson | 189 |

| Saint Cecilia’s Hall | 191 |

| A Friendship is Born | 195 |

| Crochallan Cronies | 203 |

| Look Up and See | 208 |

| The Forgotten Grave | 224 |

| All the Blue Devils | 227 |

| Beginning to Drift | 230 |

| Robert Cleghorn | 239 |

| Spring Sunshine | 246 |

| A Question of Faith | 253 |

| Sale of a Birthright | 256 |

| Good-bye to Peggy Cameron | 259 |

| Purpose | 264 |

| Mrs. Carfrae Says Good-bye | 268 |

| Gratitude | 268 |

| May Morning | 273 |

| THE LONG WAY HOME | |

| Over the Lammermuirs | 277 |

| Sunday at Berrywell | 299 |

| On English Soil | 302 |

| Melting Pleasure | 304 |

| The Guidwife of Wauchope House | 311 |

| Sweet Isabella Lindsay | 317 |

| Gilbert Ker of Stodrig | 324 |

| Willie’s Awa’ | 329 |

| Elibanks and Elibraes | 334 |

| Back to Dunse | 338 |

| The Nymph with the Mania | 341 |

| Dr. Bowmaker and Cimon Gray | 352 |

| Sweet Rachel Ainslie | 359 |

| English Journey | 365 |

| The Lass at Longtown | 370 |

| Native Heath | 374 |

| JEANIE’S BOSOM | |

| Lassie, My Dearie | 387 |

| Family Favourite | 390 |

| James Armour Forgets | 393 |

| Friends and Enemies | 396 |

| Present for John Rankine | 398 |

| Daljarrock Peggy | 400 |

| A Snub for Holy Willie | 406 |

| Daddy Auld is Troubled | 408 |

| Lassie Lie Near Me | 410 |

| The Fair Eliza | 414 |

| Inquest on Mary Campbell | 421 |

| Campbell Country | 424 |

| Hymn to the Sun | 431 |

| Freedom of Dumbarton | 433 |

| Cowgate Nights | 435 |

| OSSIAN’S COUNTRY | |

| Heat Wave in Auld Reekie | 443 |

| Bed at Willie Nicol’s | 444 |

| Interviews | 444 |

| What of the Future? | 447 |

| Hurrah for the Highlands | 448 |

| A Classic Text | 450 |

| A Lovely Morning | 452 |

| The Old Blue Whinstone | 455 |

| Stirling Castle | 457 |

| On Devon’s Banks | 460 |

| Instincts of a Gentleman | 462 |

| The Bob o’ Dunblane | 466 |

| Northern Scenes | 471 |

| The Birks of Aberfeldy | 476 |

| A Fiddler from the North | 479 |

| Cumha Chlaibhers | 481 |

| Worth Going a Mile | 482 |

| Ghosting the Gloaming | 485 |

| Never at the Centre | 488 |

| Scene of a Murder | 490 |

| A Highland Baillie | 492 |

| The Long Graves | 494 |

| Bonnie Castle Gordon | 498 |

| Aberdeen Awa’ | 505 |

| Fatherland | 510 |

| Back to Auld Reekie | 513 |

| DIALECTICS OF DESIRE | |

| End of An Idyll | 517 |

| Reason for Living | 520 |

| The Rosebud | 522 |

| Ayrshire Interview | 525 |

| No Escape | 527 |

| More Patience | 529 |

| History of a Young Widow | 531 |

| Mistress and Maid | 536 |

| The Onslaught | 537 |

| The First Letter | 543 |

| Evil Star | 544 |

| Love Letters | 546 |

| The Weakest Link | 551 |

| Women Must Wait | 555 |

| Masks Off | 561 |

| To Graham of Fintry | 567 |

| News of Jean | 568 |

| Behind the Scenes | 569 |

| Heaven—and Clarinda | 572 |

| Jenny Clow | 574 |

| Humiliation | 578 |

| The Barriers Down | 582 |

| The First Parting | 586 |

| The Thought for the Deed | 590 |

| Clarinda Shows Her Cards | 594 |

| Provision for Jean | 597 |

| The Recantation of Father Auld | 599 |

| The Mahogany Bed | 600 |

| On the Banks of the Nith | 603 |

| No Question of Baptism | 609 |

| Tait’s Masterpiece | 610 |

| Gavin Hamilton’s Clay Feet | 613 |

| To Robert Muir, Dying | 615 |

| Clarinda’s Claws | 616 |

| Weal or Woe | 618 |

| Auld Reekie Again | 619 |

| The Secret Chamber | 620 |

| The Excise Commission | 625 |

| James Johnson | 626 |

| The Installation of Ainslie | 629 |

| Jenny’s Bawbee | 631 |

| The Death of Sylvander | 632 |

| Farewell to Auld Reekie | 639 |

| OF A’ THE AIRTS | |

| A Crack wi’ Adamhill | 643 |

| Concerning the Excise | 647 |

| Song Without Words | 650 |

| Daddy Auld Deliberates | 654 |

| The Mother | 656 |

| Eternity in a Sigh | 658 |

| The Words and the Song | 662 |

| GLOSSARY | 672 |

in their order of appearance

(Fictional characters are printed in Italics)

ROBERT BURNS.

ARCHIBALD PRENTICE, farmer, near Biggar.

JAMES STODART, farmer, near Biggar.

MRS. STODART, wife to James Stodart.

JOHN BOYD, street caddie, Edinburgh.

JOHN SAMSON, brother of Tam Samson, Kilmarnock.

JAMES DALRYMPLE, squire of Orangefield, Ayrshire.

MRS. CARFRAE, landlady, Baxters’ Close, Edinburgh.

JOHN RICHMOND, writer, Baxters’ Close, Edinburgh.

JOHN DOWIE, vinter, Libberton’s Wynd, Edinburgh.

JAMES CUNNINGHAM, Earl of Glencairn, Coates House, Edinburgh.

ELIZABETH MacGUIRE, Dowager Countess of Glencairn.

LADY ELIZABETH CUNNINGHAM, sister of Earl of Glencairn.

WILLIAM CREECH, bookseller, Craig’s Close, Edinburgh.

WILLIAM SMELLIE, printer, Anchor Close, Edinburgh.

MR. and MRS. DAWNEY DOUGLAS, tavern-keepers, Anchor Close, Edinburgh.

HENRY MacKENZIE, author and lawyer, Cowgatehead, Edinburgh.

JAMES BURNETT, Lord Monboddo, 13, Saint John Street, Edinburgh.

DUGALD STEWART, Professor of Moral Philosophy, Edinburgh University.

REVEREND DOCTOR HUGH BLAIR, Argyle Square, Edinburgh.

REVEREND WILLIAM GREENFIELD, Bristo Port, Edinburgh.

PETER HILL, clerk to Creech, 160, Nicolson Street, Edinburgh.

ELIZABETH LINDSAY, wife to Peter Hill.

MR. (and MRS.) JOHN WOOD, solicitor and surveyor of windows, Libberton’s Wynd, Edinburgh.

JANE MAXWELL, Duchess of Gordon, George Square, Edinburgh.

HON. HENRY ERSKINE, Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, 27, Princes Street, Edinburgh.

COL. WILLIAM DUNBAR, Writer to the Signet, 18, Princes Street, Edinburgh.

SIR JAMES HUNTER BLAIR, Lord Provost, George Street, Edinburgh.

JANE ELLIOT, Brown Square, Edinburgh.

CAPTAIN MATTHEW HENDERSON, Saint James’s Square, Edinburgh.

REVEREND ALEXANDER (JUPITER) CARLYLE, Inveresk.

ALEXANDER, Duke of Gordon, George Square, Edinburgh.

MRS. PRINGLE, tavern-keeper, Buccleuch Pend, Edinburgh.

ELIZABETH BURNETT, daughter of Lord Monboddo, 13, Saint John Street, Edinburgh.

BISHOP JOHN GEDDES, Saint John Street, Edinburgh.

PROFESSOR JAMES GREGORY, 15, Saint John Street, Edinburgh.

PATRICK MILLER, 18, Nicolson Square, Edinburgh.

MARGARET (PEGGY) CAMERON, serving-girl, Cowgate, Edinburgh.

CHRISTINA LAURIE, Shakespeare Square, Edinburgh.

ARCHIBALD LAURIE, divinity student, Shakespeare Square, Edinburgh.

JAMES SIBBALD, bookseller and librarian, Parliament Close, Edinburgh.

MRS. ALISON COCKBURN, Crighton Street, Edinburgh.

ANDREW DALZEL, Professor of Greek, Edinburgh University.

JAMES (BALLOON) TYTLER, Hastie’s Close, Edinburgh.

ALEXANDER NASMYTH, portrait painter, Wardrop’s Close, Edinburgh.

JOHN BEUGO, engraver, Princes Street, Edinburgh.

HENRY DUNDAS, George Square, Edinburgh.

ROBERT MacQUEEN, Lord Braxfield, George Square, Edinburgh.

PROFESSOR ADAM FERGUSON, Argyle Square, Edinburgh.

JANET BERVIE RUTHERFORD, wife to Reverend William Greenfield.

REVEREND DOCTOR THOMAS BLACKLOCK, West Nicolson Street, Edinburgh.

MARGARET (PEGGY) CHALMERS, cousin of Gavin Hamilton, Edinburgh and Harviestoun.

REVEREND WILLIAM ROBB of Tongland and Balnacross.

WILLIAM WOODS, actor, 4 Shakespeare Square, Edinburgh.

WILLIAM NICOL, teacher, Buccleuch Pend, Edinburgh.

ALEXANDER YOUNG, lawyer, Hanover Street, Edinburgh.

CHARLES HAY, lawyer, George Street, Edinburgh.

ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, lawyer, Blackfriars’ Wynd, Edinburgh.

ROBERT AINSLIE, law student, Carrubber’s Close and Saint James’s Square, Edinburgh.

ROBERT CLEGHORN, farmer of Saughton Mills, Corstorphine.

ROBERT BURN, mason and architect, Edinburgh.

BARBARA ALLAN, wife to Robert Cleghorn, Corstorphine.

JAMES JOHNSON, engraver, Bell’s Wynd, Edinburgh.

WILLIAM TYTLER, Laird of Woodhouselee, Glencorse.

STEPHEN CLARKE, teacher of music, Gosford’s Close, Edinburgh.

PACK-MAN at Fasney Burn.

LANDLORD, change-house at Fasney Burn.

DOUGLAS AINSLIE, brother of Robert Ainslie, Berrywell.

RACHEL AINSLIE, sister of Robert Ainslie, Berrywell.

ROBERT AINSLIE, land factor, Berrywell.

CATHERINE WHITELAW, wife to Robert Ainslie, Berrywell.

WILLIAM DUDGEON, farmer, East Lothian.

REVEREND DOCTOR ROBERT BOWMAKER, minister of Dunse.

CIMON GRAY, retired London bookseller, Dunse.

PATRICK BRYDONE, traveller, Lennel House, Coldstream.

MARY ROBERTSON, wife to Patrick Brydone, Lennel House, Coldstream.

MR. and MRS. FAIR, Jedburgh.

MISS LOOKUP, sister of Mrs. Fair.

MR. POTTS, lawyer, Jedburgh.

REVEREND THOMAS SOMERVILLE, minister of Jedburgh.

MISS HOPE, Jedburgh.

ISABELLA LINDSAY, sister of Doctor Lindsay, Jedburgh.

PEGGY LINDSAY, sister of Doctor Lindsay, Jedburgh.

DOCTOR ELLIOT, Bedrule.

WALTER SCOT, farmer, Wauchope House.

ELIZABETH RUTHERFORD, wife to Walter Scot, Wauchope House.

ESTHER EASTON, Jedburgh.

GILBERT KER, farmer of Stodrig, Kelso.

SIR ALEXANDER DON of Newton-Don, Kelso.

LADY HENRIETTA CUNNINGHAM, wife to Sir Alexander Don.

DOCTOR CLARKSON, Selkirk.

REVEREND JAMES SMITH, minister of Mordington, Merse.

ANDREW MEIKLE, farmer and inventor, East Lothian.

THOMAS HOOD, farmer, Merse.

ROBERT and WILLIAM GRIEVE, merchants, Eyemouth.

BETSY GRIEVE, Eyemouth.

MR. SHERRIFF, farmer of Dunglass Mains, Dunglass.

NANCY SHERRIFF, sister of Sherriff, Dunglass.

JOHN LEE, landlord of Skateraw Inn.

JAMES MITCHELL, merchant, Carlisle.

REVEREND WILLIAM BURNSIDE, minister of New Church, Dumfries.

ANNE HUTTON, wife to Reverend William Burnside.

PROVOST WILLIAM CLARK, Dumfries.

MR. and MRS. JOHN DOW, The Whitefoord Arms, Machlin.

JEAN ARMOUR, eldest daughter of James Armour, Machlin.

GILBERT BURNS, brother of Robert, Mossgiel.

WILLIE BURNS, brother of Robert, Mossgiel.

ISABELLA BURNS, sister of Robert, Mossgiel.

ANNABELLA BURNS, sister of Robert, Mossgiel.

AGNES BURNS, sister of Robert, Mossgiel.

MRS. AGNES BURNS, mother of Robert, Mossgiel.

JAMES ARMOUR, mason and wright, Machlin.

MARY SMITH, wife to James Armour, Machlin.

ADAM ARMOUR, brother of Jean Armour, Machlin.

JOHN RANKINE, farmer of Adamhill.

GAVIN HAMILTON, writer, Machlin.

HELEN KENNEDY, wife to Gavin Hamilton, Machlin.

MARGARET (PEGGY) KENNEDY, sister of Mrs. Hamilton, Daljarrock House.

DOCTOR JOHN MacKENZIE, physician, Machlin.

ROBERT AIKEN, lawyer and collector of taxes, Ayr.

WILLIAM FISHER, farmer of Montgarswood and Machlin Kirk elder.

REVEREND WILLIAM AULD, Machlin Parish minister.

ELIZA MILLER, Machlin belle.

MRS. CAMPBELL, mother of Mary Campbell, Greenock.

DOCTOR GEORGE GRIERSON, Glasgow.

LANDLORD of Inn at Inveraray.

MR. MacLAUCHLAN of Bannachra, Loch Lomondside.

DUNCAN MacLAUCHLAN, son of Mr. MacLauchlan.

MARY MacLAUCHLAN, daughter of Mr. MacLauchlan.

A HIGHLANDER, Arden, Loch Lomondside.

JOHN MacAULAY, Town-clerk, Levengrove House, Dumbarton.

JAMES COLQUHOUN, Provost of Dumbarton.

REVEREND JAMES OLIPHANT, minister of Dumbarton.

CAPTAIN GABRIEL FORRESTER, officer in charge, Stirling Castle.

CHARLOTTE HAMILTON, half-sister of Gavin Hamilton, Harviestoun.

MR. JOHN TAIT of Harviestoun, and Park Place, Edinburgh.

REVEREND DOCTOR DAVID DOIG, Rector of Stirling Grammar School, Stirling.

CHRISTOPHER BELL, Stirling.

LANDLADY, Dunblane.

NIEL GOW, Dunkeld.

JOSIAH WALKER, tutor, Blair Castle, Blair Atholl.

SIR JAMES and LADY GRANT, Castle Grant, Speyside.

JOHNNY FLECK, coachman, Pleasance, Edinburgh.

MRS. ROSE, cousin of Henry MacKenzie, Kilravock.

MRS. ROSE, mother of Mrs. Rose of Kilravock.

REVEREND ALEXANDER GRANT, minister of Cawdor.

WILLIAM INGLIS, Baillie of Inverness.

MRS. INGLIS, wife to William Inglis.

MISS ROSS, Kilravock.

JAMES BRODIE OF BRODIE, Nairn.

JAMES HOY, librarian to Duke of Gordon, Castle Gordon.

JAMES CHALMERS, printer, Aberdeen.

PROFESSOR THOMAS GORDON, King’s College, Aberdeen.

BISHOP JOHN SKINNER, Aberdeen.

JAMES BURNESS, lawyer, Montrose.

DOCTOR JAMES MacKITTRICK ADAIR, Edinburgh.

MRS. CATHERINE BRUCE, Clackmannan Tower, Clackmannan.

WILLIAM CRUIKSHANK, teacher, 2, Saint James’s Square, Edinburgh.

MRS. CRUIKSHANK, wife to William Cruikshank.

JENNY CRUIKSHANK, daughter of William and Mrs. Cruikshank.

WILLIAM NIMMO, Supervisor of Excise, Alison Square, Edinburgh.

MISS ERSKINE NIMMO, sister of William Nimmo, Alison Square, Edinburgh.

MRS. AGNES MacLEHOSE, General’s Entry, Potterrow, Edinburgh.

JENNY CLOW, maid to Mrs. MacLehose, Potterrow, Edinburgh.

ALEXANDER (LANG SANDY) WOOD, surgeon, Edinburgh.

ALLAN MASTERTON, writing master, Stevenlaw’s Close, Edinburgh.

JOHANN GEORG CHRISTOFF SCHETKY, musician, Foulis’s Close, Edinburgh.

MRS. STEWART, Alison Square, Edinburgh.

SAUNDERS TAIT, Tarbolton tailor and rhymster.

WILLIAM MUIR, The Mill, Tarbolton.

BALDY MUCKLE, tailor, Backcauseway, Machlin.

MATTHEW MORISON, cabinet-maker, Machlin.

JEAN SMITH, sister of James (Wee) Smith, Machlin.

JOHN TENNANT, factor-farmer, Glenconner.

NANCE TINNOCK, ale-wife, Backcauseway, Machlin.

MRS. MARKLAND, merchant’s wife, Machlin.

JAMES FINDLAY, Excise Officer, Tarbolton.

DAVID CULLIE, farmer, Ellisland.

NANCE CULLIE, wife to David Cullie.

FIDDLING SANDY, itinerant fiddler.

‘Every pulse along my veins

Tells the ardent lover.’

From: “Thine Am I, My Faithful Fair.”

By: Robert Burns.

Part One

THE CUP OF FAME

It was a cloudy lowering day and visibility was something less than an honest Scots mile. A dowie day, when the trees stood listless, dripping and clammy with dampness, in a slouched halt by the roadside. The saffron-grey grass seemed to have decayed so long in death that it would take all the miracle of spring to resurrect in it the green sap of life. A few white-breasted sea-mews, freshly daubed on a withered lea-rig, appeared curiously disinterested in the new-turned furrows. Above them, some tattered crows flapped disconsolately—occasionally venting an inconsequential caw.

The November day was wearing late: it was at its dowiest. And Robert Burns, as he jogged in the saddle and allowed the pony to pick his own way, felt leaden-dull. Lack of sleep, hard riding and an unaccustomed overdose of alcohol (pressed on him by ardent admirers) had lowered his spirits and vitiated his immediate appetite for life.

When he had made his halt in the early evening of the previous day, when he had ridden into the snod steading of Covington Mains, on the Biggar road, his host, farmer Prentice, had at once hoisted a white sheet on a pitchfork and had planted it in his highest grain-stack.

It had been a pre-arranged signal: the neighbours knew its meaning. Big Jamie Stodart had seen it flutter in the evening breeze and had gone into his wife saying: “That’s the Ayrshire Bard arrived—I’ll awa’ ower and grasp his hand afore they hae it shook aff him.” And then, as he had busied himself with a rough toilet: “Guid kens when we’ll be back—but see and keep a hot stane in the bed for him.”

They had made merry at Prentice’s till early in the morning. When at length he had expressed the wish that he might be bedded, Big Jamie had linked him across to his biggin where, as she had been instructed, Mrs. Stodart had the bed warmed.

But it seemed he had hardly slept when the house began to fill up for breakfast. Those who had not managed to see him the previous night began to clatter into the court-yard.

At breakfast, as at supper, the whisky and the home-brewed ale had flowed with a friendly freeness. It was only with the greatest difficulty he had escaped from their exuberant hospitality.

There was not so much to wonder at here: the folks about Biggar were kind-hearted honest country folk such as he had always known. Aye: kind-hearted free-spirited folks—but foolish company when so much of his journey lay before him. . .

He eased himself in the saddle and pressed his hand across his stomach. The excess of alcohol had outraged his innards and he twisted his face in a grue of nausea. He had never drunk much at any time and only to excess in moments of great emotional crisis. But now, in addition to the alcoholic reaction, there was the nervous agitation of anticipation. He had taken a big step in severing his Ayrshire roots and staking his immediate future on the gamble of an Edinburgh edition for his poems. The nearer he approached the Capital, the more violent did the nervous spasms become. His star had ever been a malign one. Was there any reason to suppose that his fortune would change with a change of country?

And yet, as always, his profound sense of the inevitability of events saved him from despair. For good or for evil, he must go forward and press his fortune in Edinburgh. What would come to pass would come to pass. For his own part, he would strive with all his strength for success. But, if success was not to be, he would weep no tears of useless regret. At best, fortune was but a bitch: cold crafty and senselessly cruel. When she smiled, the other side of her face was never very far away.

His arches were sore pressing on the stirrup irons. Maybe it would be easier if he dismounted and walked for a mile; but then, if he did, there would be the effort of remounting!

Surely by now he must be nearing the Capital? But he was past the Toll and jogging down the Twopenny Custom Road when he raised his head and there before him, and above him, the Rock and the Castle that crouched on it seemed to hang in the damp grey mist.

The pony placed a hind foot in an awkward rut and sprachled clumsily to regain a surer footing. The movement, coming at so abstracted a moment, almost unseated him.

He patted the beast reassuringly on the neck. “Steady, boy, steady—if you throw me now I’ll never rise.”

Having recovered his balance, he found his jaded nerves responding to the sight. Auld Reekie at long last! God, but he was pleased to see it, even if it was shrouded in a cold damp of misty twilight.

But this was not how he had pictured the scene. He had always imagined the Castle and the Rock responding to strong sunlight, grave yet gallant, head upwards-thrown in proud and gay defiance. And there was little in the towering masonry of the town that suggested the canty hole Robert Fergusson had sung about.

Glad as he was to be within sight of his journey’s end, he could not wholly warm to this sight of Scotland’s capital. It was too grim and grey, too cold and blurred in its outlines to cast forth anything of its essential inner warmth. But perhaps there was greyness within him as well as around him; and the tired tail-end of a dowie day was not the best time to witness the realisation, in stone and lime, of a long-cherished vision.

The pleasant familiarity of Machlin and Mossgiel lay sixty miles behind him; and many a wet moss and weary hag lay between. From the ridge of Mossgiel, Edinburgh, lying beyond the far blue hills, had beckoned in his imagination like a city celestial.

Now he was about to enter the gates of the city and meet the challenge of a new world. Never before had he felt less like meeting any challenge. Maybe he had been over-bold, over-venturesome. To stride and dominate the centuries-hardened ridge of Scotland’s capital was a vastly different business from striding and dominating the ridge of Mossgiel.

But he must go forward and face it. Maybe once he was settled in with his old Machlin friend, John Richmond, and had enjoyed a night of quiet rest, things would take on a different aspect.

He shook the reins; and the pony, with a tired pent-up snort and a shake of the head, hastened his forward step.

He wheeled sharply to his right, came in the Portsburgh road where tired bedraggled and dilapidated houses flanked either side, and entered the Town by the West Port. Here, even as his Ayr friend, Robert Aiken, had predicted, a caddie came forward and offered his services as messenger or as guide. He asked to be directed to the White Hart Inn in the Grassmarket, that he might stable his horse and make arrangements for him to be taken back to Ayrshire by carrier Patterson.

John Boyd, the caddie, tried to take him in with a swift penetrating glance. “You’re in the Grassmarket noo, sir! That’s the Inn ower there on your left. Will I tak’ the beast?”

He dismounted; and the caddie led the pony forward.

He looked around him. The Grassmarket was a vast rectangle, and though the fading light was deceptive, he reckoned it was close on two-hundred-and-fifty yards long and maybe forty full yards in breadth.

Above it, on his left, with vague sinister menace, towered the south cliff of the Castle Rock. Beyond the quaint irregular buildings on his right loomed the turret towers of Heriot’s Hospital, while farther up towards the Cowgate corner and the slit of the Candlemaker Row he could discern the ghostly bulk of the Greyfriars Kirk.

These landmarks, though he could not as yet identify them, he noted in a sweeping glance. Then the Market itself fascinated him. He had never seen so many well-made carts, carriages and hand-barrows. And here and there about the causeway, placed with no seeming order, stood little wooden booths about which groups of idling gossiping folks were loosely knotted. And occasionally above the rattle of wheels on the paving stones he could hear the harsh but indistinct call of a vendor or the curse of a carter.

A great pile of hay was stacked in front of the inn door. And above the door, on a painted board, he saw the sign with the name of the proprietor, Francis MacKay, inscribed in bold, if irregular, letters. It seemed that he could not have entered the Town by a more convenient route.

No sooner had he made his business known to the groom than he brought out Tam Samson’s brother John to greet him.

“By God, Rab, you’re a sicht for sair een. Man, but I’m glad to see ye. I heard ye were on your way: so I’ve been waiting. I want to borrow your pownie so that I can ride back to Kilmarnock at my pleasure—and do a bit business on the road.”

“Well . . . it’s no’ mine to give, John. It belongs to George Reid o’ Barquharrie; and I promised him I would return it by Patterson. . .”

“It’ll be safer wi’ me; and Geordie Reid and me are good friends: he’ll raise no objections. . .”

While they were discussing the matter, out came James Dalrymple of Orangefield. He too gave him a hearty welcome. The Bard shook his head in perplexity. He had never expected to meet two Ayrshire men the moment he entered the Town. He explained his difficulty about the pony to Dalrymple. Dalrymple was decisive. He knew John Samson. He would vouch for him. The Bard decided that Samson must carry back with him a letter of explanation to George Reid. This was agreed upon and they entered the inn to have a drink while the Bard penned his brief note.

“Yes,” said the Squire of Orangefield in his large and elegant manner, “I stable my own mount with MacKay here—and my carriage beasts, of course. Good fellow, MacKay—and he keeps damn good grooms—ken how to treat a good animal—especially after a hard day’s riding. Noo see here, Burns: you give me a note of your lodgings in the Town and I’ll keep in touch wi’ you. Maybe the morn—or maybe the next day—I’ll tak’ you out to Coates House to see my cousin Glencairn. I ken he’s delighted wi’ your book and will gladly give you his patronage. No reason why you shouldna hae a happy time in the Town, Burns: no reason at all. And you deserve it. But—you’re not drinking?”

“If you’ll excuse me, sir . . . I never had much of a stomach for drinking, and the savage hospitality I have had thrust upon me on my journey here has ruined what little stomach I had.”

“Ha! we’ll soon put that right for you here. Your stomach hasn’t been properly tanned: that’s what’s wrong with you. In no time you’ll turn the bottoms of five bottles with the best. But I see you’re tired, Mr. Burns. Get up to your lodgings and have a good night’s rest and you’ll be as fit as a fiddle in the morning: it’s damned hard riding to make Edinburgh in twa days. The caddie will carry your saddle-bags up the hill for you. And don’t worry: Samson will look after the pony. . . You ken, Burns, the Town’s waiting on you. Your fame’s here afore you. Indeed . . . eh . . . there’s been a lot o’ talk about you. One of the prints here has been carrying some of your Kilmarnock verses.”

“What print would that be, sir?”

“Eh . . . the Edinburgh Magazine.”

“Edited and wrote mostly by a Mr. James Sibbald, I understand.”

“In the Parliament Close—that’s the fellow! Well . . . I suppose a man canna have friends without he has enemies as well. I’m glad you had the good sense to visit the Town. I’m sure your appearance, in person, will have the effect of laying much rumour i’ the dust.”

Beneath his tan the blood ran hot. “What rumours, sir? Have the goodness not to spare my feelings in a matter that so closely affects my honour.”

“It’s difficult, Burns. But we’re friends. . . The fact is that some nasty rumours have got abroad affecting your moral character. I was about to rise to your defence the other night when Sir John Whitefoord immediately manned the breach and defended you so stoutly that your enemies were completely routed.”

“Sir John Whitefoord rose in my defence?”

“That he did, Burns, and did nobly. Of course I backed him up—though as things turned out there was little need for my artillery: a musketry ball or two cleared the field. No: don’t thank me, Burns——What I mean is that rumours have a way of spreading in the Town—and your friends canna be everywhere to defend you. But—you will be your own best defence. And that’s why I’m glad you have made your appearance. Think no more of it, I pray you—I merely put you on your guard and, at the same time, let you know that your friends are with you.”

“But I must thank——”

“No, sir: I will hear of no thanks. And once my worthy kinsman Glencairn takes you under his protection no one will dare to utter a word against you.”

For some moments the Bard remained in gloomy silence. So the Holy Willies were here in Edinburgh as well as in Machlin! Well, he would make his stay short. The Roselle was due to leave Leith for Jamaica at the end of December—he could always work his passage there—and be damned to all the Holy Willies and evil-tongued gossip-mongers of Scotland. But there were men like Sir John Whitefoord—and Dalrymple here! He took his hand slowly from his head.

“Forgive my manners, sir. I have a miserable aching head—and I confess your news has depressed me.”

“Ah, you mauna be depressed, Burns. If you would have fame you must learn to reckon with envy. Why! people say of me that I am a foolish man squandering my estate and riding to the devil. Am I depressed? Do I give a damn for what they say? But just let any damned cad say ocht to my face and I’ll whip the lights out of him. . . Now a poet——”

“A mere rustic bard, sir, who was foolish to abandon the plough——”

“Stuff, sir! You are under the weather for the moment. Toss back your drink and have the caddie take your bags up to the Landmarket. You have more friends in the Town than you think. Come—finish your drink and think no more of it. Here’s John Samson back from having seen to Reid’s pony. . .”

When he ventured out into the wide gloomy square of the Grassmarket, the weather seemed to have changed. A keen wind sliced at his face and hands. But the thinly-clad caddie grasped his bags and did not seem to mind it.

Inside the mellow warm inn Dalrymple and Samson had seemed big hearty fellows, their personalities roundly and warmly defined. Now they seemed small and insignificant specks of humanity in this mass of beings weaving about the causeway. Even his own identity seemed to ooze away from him among the press of individuals as unknown to him as they seemed to be unknown and indifferent to each other.

Unlike his caddie, many of them crouched in their walk against the bitter winds that knifed through the narrow streets, the narrower wynds and the yet narrower closes: winds that cut and slashed from all angles like sword blades in desperate and closely-joined battle.

As he approached the head of the Grassmarket, walking east into the biting east wind, the great gloomy lands of tenements seemed to rise to fantastic heights. Noticing a long pillared roof that stood on the causeway at the foot of the tenement crags, he asked the caddie what it was.

“That’s the Corn Market, sir.”

“Ah! The Corn Market, is it? And where exactly did they murder James Renwick?”

“Murder? I heard nocht about that, sir.”

“James Renwick, the last martyr of the Covenant. Murdered on the gallows-tree somewhere hereabouts.”

“Oh, the gibbet, sir? Ye see that meikle stane wi’ the hole in’t. That’s whaur the gibbet was fixed. Aye, sir; mony a guid man met a sair death here—in the auld days. Aye, but mony a weel-deservit hanging too. The last man that was hangit there—let me see noo—aye, jist twa year ago come Feebrywar—aye, he robbit a man in the Hope Park. . . They string them up now fornenst the auld Tolbooth—no’ a dizzen o’ guid steps frae whaur ye’re for biding at Baxters’ Close. . . Aye, an’ Half-Hangit Maggie Dickson was hangit there, sir. It’s a wee whilie back—but my faither saw it. Aye, the surgeons’ laddies were for takin’ her awa’ for cutting up at the Surgeons’ Ha’; but her frien’s wheecht her awa’ in a cairt. Syne, the dirlin her banes got on the causeway, sir, set her heart beating again. Aye . . . and she had bairns efter that, sir, and sold salt aboot the streets o’ the Toon for mony a day.”

But the Bard was listening with only half an ear. His mind was turning back the pages of history and he was seeing again the ordeal of the Martyrs. . . And as he stood there, his head bowed, he knew that every generation had its martyrs and that the fight for liberty had to be endlessly waged. He sighed deeply and turned to the caddie who was beginning to show signs of impatience. They moved up into the steep chasm, the dog’s hind leg, of the West Bow that led up and on to the high ridge of the Town.

As they moved up into the ever-narrowing street and the buildings began to overhang him, he felt that now he was entering into the city of which Robert Fergusson had sung so bravely and Tobias Smollett had written so graphically.

The caddie, seeing that his fare was interested in the Town and its history, and thinking also that he might win from him an extra bawbee, voiced a running commentary as they proceeded.

“This is ca’ed the Bowfoot, sir. When there was a hanging taking place the crowd got a grand view frae the brae here: packed like herring in a barrel they were. Aye: if thae auld stanes could talk they would tell a queer story. . .

“See that arched pend there? Aye: well, it was through there that Major Weir bided wi’ his sister. Him that sellt himself to the Devil. Damn the doubt about that, sir. His ain confession. Na: he didna recant even when they put the rope round his neck and lit the meikle bonfire ablow him. That was a wheen years ago noo; but the house is still empty. God help onybody that tries to bide in it! For the Major pays it a visit back and forwards. It’s no’ the yae body aboot the Bow that’s seen him. Hunders, sir. Aye, and hunders mair hae heard the ongauns when Auld Nick drives up wi’ a carriage-an’-fower to convey him back to Hell. God’s truth, sir! If I were you I wadna think o’ venturing aboot the Bow after twelve on a dark nicht. . .

“That’s the auld Assembly Rooms, sir, whaur the Quality had their dances: my auld faither used to tell me how he’d seen the Bow fair chokit on an Assembly nicht wi’ sedan chairs: lords, dukes, earls and their leddies, sir: a grand sicht: aye, and the attendants wi’ their lanthorns on a bit pole and the chairmen cursing and swearing in Erse through each other, and the bits o’ laddies egging them on and laughing at them. Ah, but ye’ll get a better view o’ the place in full daylicht. That was Provost Stewart’s hoose. He entertained the Prince when he was here in the Forty-five. The hoose is fu’ o’ secret chaumers and stairs and passages. Mony a murder would be done there in the auld days that naebody ever heard aboot: aye, and could be yet. . .

“Ah well: here we are, sir, coming up onto the Landmarket: the Bowhead, sir, fornenst the Weigh-house. Aye, it’s a stiff brae and a damn rough causeway: if ye ever think o’ takin’ a beast up or doon it, ye’d be weel advised to lead it. Break your neck gin ye were coupit on thae causeys: aye, bluidy quick. Here ye are then, sir: this is you in the Landmarket.”

Against the clip and drawl of the caddie’s accent the Bard had swivelled his head from right to left, fascinated by the amazing diversity of architecture displayed by the façades of the Bow houses. Not only were there no two houses alike: almost every stone seemed to have been laid without artistic reference to its neighbours. And yet the seemingly haphazard craziness of the architecture gave the place a fantastic charm that could not be denied. But there was a grim, almost diabolic, element in the fantasy that repelled. From such dark and foul-smelling entries any imaginable evil might well emerge under the cover of darkness. He was glad to stand for a moment and take his breath in the airier Landmarket.

Many of the Machlin streets were narrow enough in all conscience. But the buildings that flanked them were small and seldom climbed beyond a modest attic. But here, everywhere around him, the lands climbed to the appalling height of six and eight storeys. And the gaunt lands of dirty grey stone and soot-black ashlar were separated by the narrowest of slits of closes and wynds into which only the greyest and dirtiest of daylight ever managed to filter. The builders had grudged these slits of openings. From the second floors the building lines projected over the base, so that the upper tenants could grip hands and hold intimate converse with their neighbours across the gap. . .

Coming after twenty-seven years of farm life in the uplands of Ayrshire, all this had a stunning effect. He could well remember the narrow vennels and the high buildings of Irvine; and he could recall the stenches and stinks of that seaport town. But the stinks of Irvine were scents compared to the vile stenches that had assailed his nostrils since he entered the Town.

And now he was standing on the south side of the Landmarket, part of the uninterrupted mile that ran upwards from the Palace of Holyrood through the Canongate and the High Street to the Castle. It was a moment he had long imagined, and indeed many a time in his imagination he had traversed this far-famed mile of history.

The caddie saw he was lost in a dwam and sought, tactfully, to rouse him from it.

“Aye: it’s a great Toon, sir. Ye could look aboot you a’ day an’ never light on Mr. Richmond. Aye, and ye could just as easy lose yoursel’. On your left, sir: that’s Castle Hill straight up to the Walk and the Castle. To your right here, the Landmarket: that’s the Toll and the Luckenbooths ye see doon there i’ the middle o’ the causeway fornenst Saint Giles’s. . . And further doon’s the North Brig that tak’s ye to the New Toon. Oh aye: they’re comin’ on weel wi’ the New Toon. Will ye be biding lang, sir?”

The Bard roused himself.

“Biding? I don’t rightly know. But as like as not I’ll be here for some time—a week or two anyway.”

“Ye’ll hae business in the Toon, sir? It wouldna be a law plea? If it’s the Court o’ Session, ye may hae lang enough to wait: the Lords’ll no’ gee themsel’s much unless ye can mak’ it worth their while.”

“That, my lad, I know only too well. No: what my business is in Edinburgh will be known to you soon enough—if it prospers. And if it doesn’t, then it’ll be of no interest to you—or to anyone.”

“It was just that folk micht be spiering for you.”

“Give them my best compliments and tell them where they can find me.”

The caddie was an excellent judge of human nature. But he found it difficult to place Robert Burns. The West country was in his intonation but it was not in his speech. He spoke much too correctly to be a country farmer or a small country squire, though his dress indicated that such might be his station in life. He might be a teacher of languages or a tutor to one of the sons of the nobility. But here again the coarseness of his hands and the rhythm of his gait—to say nothing of his weather-tanned and exposed complexion—belied anything but an outdoor life. Close and observant, it was clear that he had all his wits about him. A kindly man; but a tough customer if he were crossed. . .

“I suppose you could direct me to my Lord Glencairn, or the Honourable Andrew Erskine, or Sir John Whitefoord, or Doctor Blacklock, the blind poet. . . .? Do all these good gentlemen have their residences about here?”

For a split second the caddie was nonplussed. “The nobility of Scotland live in thae lands, sir. Some now bide in the New Toon; but the maist o’ them prefer here—or the South side o’ the Toon: the other side o’ the Cowgate. The New Toon’s on the North side, sir. The Earl of Glencairn bides just outside the Toon here at Coates House. There’s nothing aboot the New Toon but a wheen braw buildings and a lot o’ cauld winds. I’ve heard mony a gentleman lamentin’ aboot the cauld since he flitted across: it’s far too open: ower much o’ the cauld nicht air’s no’ good for a body—unless, of course, they’re brocht up to it in the country. . .”

“Well: it’s getting too dark to see much now. Lead on, my lad: I am grateful for your intelligence.”

“Follow me, sir: we’re almost there: across the street and to your right. Excuse me, sir: Mr. Robert Burns is no’ an uncommon name i’ the Toon: how would I ken you were the gentleman I micht be askit for?”

“Robert Burns: the Ayrshire ploughman.”

“You wouldna joke wi’ a puir caddie, sir?”

“A poor ploughman, my lad, has little authority to joke with a poor caddie—or with anyone.”

A bluidy queer ploughman, thought the caddie as he led him diagonally across the street and entered Baxters’ Close. He took him along the narrow passage and up the narrow flight of rough worn steps. He indicated a narrow door.

“That’s Mistress Carfrae’s, sir. Gin you’re looking for anither caddie, there’s aye a wheen o’ us aboot the Luckenbooths.”

The Bard thanked him warmly and handed him a small piece of silver. The caddie was delighted: he expressed his satisfaction and quickly disappeared down the dark stair.

The middle-aged widow, Mrs. Carfrae, had been apprised of the Bard’s visit. After making a few cautious but shrewd enquiries she conducted him along a dark passage to Richmond’s room.

“Weel now, Mr. Burns: I hope ye’ll be contentit here. It’s a respectable hoose I keep: which is mair nor can be said aboot some folks; and I wad like it keepit that way. It’s a sinfu’ warld, Mr. Burns; and the Toon’s gettin’ wickeder and wickeder every day. . . Aye; but nae doubt ye’ll be tired after your lang journey. Mr. Richmond’s siccan a nice quiet gentleman. He doesna drink and he doesna gandie wi’ the bawds. I just canna abide my gentlemen rinnin’ after the bawds, Mr. Burns. . . Ye’ll ken that I dinna serve ony meals: excepting a bowl o’ guid parritch in the morning? I aye say that whan ye hae a bowl o’ guid parritch lining your stammick i’ the morning, ye dinna need to fash yoursel’ for the rest o’ the day. Mr. Richmond’ll no’ be lang now.”

There was a sudden interruption of high-pitched laughter from above, revealing that there was little or no deafening behind the internal lath and plaster walls and ceilings. Mrs. Carfrae screwed her face in disgust.

“That’s thae bawds abune, Mr. Burns. Wicked shameless hizzies. Ah, but the pit o’ hell’s lowin’ for them: that’s a punishment they’ll no’ escape. Weel may they hae their fling now, for they’ll hae a’ eternity to squeal and skirl. . .

“But it’s a terrible affliction for a decent Christian widow to lie in her bed i’ nichts and be keepit aff her Christian sleep by the gandie ongauns o’ brazen bawds and their filthy fellows. Aye: and the Sabbath nicht worse nor a’. Sae dinna you be tempted up the stair, Mr. Burns, or you and me’ll fa’ out completely. . . Ah, but I see you’re a decent respectable man and think mair o’ yoursel’ and your Maker than degrade yoursel’ in the company o’ abandoned women: you wadna be a friend o’ Mr. Richmond if you werena. . . And here’s The Courant if you want to pass the time—juist in.”

When at last the garrulous landlady had retired, the Bard sat on the bed and surveyed his room. It was furnished barely; but it wasn’t a bad room. There was a double bed that at one time had been an elegant-enough four-poster; but the trappings had long disappeared. The walls, above the half-panelling, were roughly plastered and were in a dirty and dilapidated condition. The floor was sanded with coarse yellow sand which helped to fill in the gaping seams of the floor-boards. A once-scrubbed table, with a missing leaf, stood against the wall. The small window that looked out on Lady Stair’s Close had a bunker-locker beneath it. There was a deep press with a door to serve as a wardrobe. On the table sat a basin and a water jug. At the foot of the bed, covered by a rough wooden lid, was a large slop-can suitable for all domestic needs. . . There was a polished stone fireplace with a corner of the mantelpiece broken off.

It would be possible to sit into the table and write in reasonable comfort—if the bawds did not prove too distracting. He was intrigued at the thought of living immediately below them. With the thin roof it was possible to hear all that was going on there. It would be interesting to see them, to speak to them and to find out what they were like and how they reacted to life. . . It was obvious that the landlady protested too much. She envied the bawds: that was plain. He knew well enough that a bawd was not to be envied; but he knew also that a bawd was a source of interest. It was strange that Richmond, in his letters, had never referred to them. But then Jock had always been a canny cautious chiel. . .

The noise from the adjoining close filtered into the room. It was a drowsy noise: the murmur of voices and the scliff of many feet on the paving. Now and again there was the sound of a voice raised in a high pitched call as if it might be hawking some ware or other. . .

He lay back on the bed and closed his eyes. He was dog-tired; but it was a great relief to be within the four walls of a room and resting quietly. And he would rest quietly for a day or two. At least he wouldn’t stir much until James Dalrymple sent word to him. Had he been serious when he had spoken of the possibility of Glencairn’s patronage? Ah, that was too much to hope for. An earl didn’t bestow patronage on a ploughman merely because he had written a book of verses. Yet Sir John Whitefoord, who had once been the laird of Ballochmyle and who had once been the patron of his Tarbolton Masons’ lodge, had stood up among the gentry and defended him! He would have to write a letter of thanks to Sir John.

He sprang up from the bed at this thought and looked underneath it. Thank heaven his sea-chest had arrived safely before him! Maybe his white buckskin breeches and his tailed blue coat would serve him well enough for dress. If he could add to this a pair of polished knee-boots and a new waistcoat he would be elegant enough to call upon any of the gentry.

Darkness had come down on the Town. He lit the candle, waited till the flame reached its full brightness and then spread the Edinburgh Evening Courant before him on the table.

But apart from learning that William Wallace, Sheriff-depute of Ayrshire and Professor of Scots Law at the University, had died that morning it contained little news to interest him. It was Wallace who had ratified Hamilton of Sundrum’s findings regarding the dispute between his father and MacLure; and James Armour’s writ against him had issued from the same office.

His eye travelled over the small print listlessly. Just as he finished reading that the pupils of Mr. Nicol’s class at the High School were to dine at Mr. Cameron’s Tavern, and before he had time to speculate about Mr. Nicol, there was a sound from the front door.

As he folded the paper he heard the stair door shutting and the sound of steps in the passage. Before he could rise to his feet John Richmond, in his great-coat and cravat, hat in hand, was in the room.

“Well: you managed at last, Rab! Damned, but I’m real glad to see you. I got away as early as I could. You’ll have had a word with Mrs. Carfrae? Good! Now I daresay you’ll be feeling like a bite of meat?”

“Aye; and your bowl o’ parritch will be far down gin now, Jock?”

“It’s the cheapest way to live. I can feed well in the howffs here for sixpence a day: sometimes fourpence: aye, and many a day I’ve put in for twopence. I’ve got to practise an extreme economy. I hope to save up enough to go back to Machlin one day and set up there for myself. How was Jenny Surgeoner when you left her? Dammit, Rab: I canna marry her the now. But one of these days I’ll do the right thing and go back and marry her. You say the bairn’s like me?”

“Well: who else would she be like, Jock? Only you might write and tell her that: it would ease her mind.”

“It’s a bad thing to write to a woman. What you say by word of mouth is one thing: what you put down on paper is another. Never put pen to paper, Rab, unless you’re dead certain; and seldom then. I’ve seen more lives wrecked through folks putting down their silly notions on paper than by ony other cause. But come on: we’ll find a quiet place where we can talk. Oh: I was forgetting to congratulate you on the success of your turning author in print. There’s some talk in the Town about your verses as it is. . . Sibbald’s Edinburgh Magazine has been cracking you up and publishing some of your verses. The Town’s talking about them. I listen and say nothing. I wad hae sent you copies o’ the papers—only I knew you’d be here ony day. Come on out and have a bite and let me hear a’ the Machlin news. Mind you, Rab, there’s times I miss Machlin—and John Dow’s. . . Damned, and I was forgetting to congratulate you on being the father o’ twins! So Jean Armour did pay you double! But maybe I should be careful o’ the word father, seeing you managed that bachelor’s certificate out o’ Daddy Auld. . . But come on: get into your coat and we’ll go out and celebrate wi’ a bite and a sup o’ ale. I ken a good place, down Libberton’s Wynd across the street. God, Robert, but I’m glad to see you. . .”

And for the moment, in the emotion of seeing his old friend and hearing his voice, the Bard’s tiredness left him and he was eager to fall in with his plans.

They went out onto the Landmarket in the darkness relieved only by the feeble lights from the windows. An odd public lamp on an odd corner provided more stink and fumes than illumination.

Though the business of the day was over there were still folks about and not a few skirling urchins.

The wynds and closes that led off the main thoroughfare on the crest of the ridge descended either to the drained basin of the Nor’ Loch or to the sunken Cowgate.

They crossed the Landmarket and descended Libberton’s Wynd that ran down to the Cowgate.

Richmond explained something of the geography of the Town as they went along. . .

At a gushet in the narrow rough-cobbled wynd they entered a tavern whose host, John Dowie, was one of the most popular in Auld Reekie.

Dowie was in many ways an older and more mellowed edition of Johnny Dow in Machlin.

At the moment Dowie was not too busy; but in an hour or so his apartments would be packed, almost literally, to suffocation—as the Bard was soon to know.

Dowie, like a good landlord, never forgot a face. Richmond was not one of his regular customers. But a customer was always a customer. Two customers at the quiet time of night were more welcome than one.

“A cauld raw nicht, Mr. Richmond. Aye . . . and are you for a bite, maybe? Something tasty to warm you up?”

Richmond introduced the Bard. “Aha now. The Ayrshire bard! And verra welcome, sir, to my bit place here. Aye: the Toon’s talking about ye, Mr. Burns. . . The skirl o’ the pan, Mr. Richmond, certainly. I’ll send a lass ben wi’ a platter for ye. . . No: there’s naebody in the coffin the noo—aye, aye: just the thing if ye’re wantin’ a quiet jaw thegither.”

The main room in which they now stood was used mostly for casual drinking. Beyond that was another room where folk who liked to spend a while over their meal might do so in better comfort. Beyond that was a tiny room that held a small table and two wall seats.

The place held two folks in modest comfort and complete seclusion. It was incapable of holding three.

And so it was that Richmond and the Bard sat and talked in the coffin, as the room had been named.

They had much to talk about. Richmond asked many questions about Machlin: the Bard asked many questions about Edinburgh. But they had many personal things to discuss. . .

“So you got a bachelor’s certificate frae Daddy Auld?”

“I did. And Jean has no legal claim on me.”

“Don’t you be daft enough to admit of ony other claim. What’s your plans?”

“Plans, Jock? I wish I had some kind of a plan. I came here on impulse—and maybe because I couldna bide Machlin ony longer. First I hope to get my poems brought out in a second edition here. I don’t suppose that’ll be easy; and even if I succeed I don’t suppose I’ll win more money than I did out of Kilmarnock Johnny. But if I can make fifty pounds maybe I’ll sail for the Indies yet. I see the Roselle sails frae Leith at the end o’ December——”

“You’ll no’ get your poems printed before then.”

“No . . . I don’t suppose I will. But as a second line I’m thinking o’ exploring the ins and outs concerning the Excise. A gauger’s job is nae catch: I ken that fine enough. But there’s a measure o’ security attached to it that I could fine be doing wi’.”

“We’re a’ looking for security.”

“Well, I’m coming twenty-eight, Jock—and I’m about ready for turning beggar ony day. That’s a fine look-out after all the years I’ve slaved on rented ground.”

“You canna live in Edinburgh on nothing, Robin. But surely you had some plan about publishing your verses?”

“Well, Bob Aiken spoke about a William Creech—I understood he was writing him.”

“Creech? A most important man in the Town. But don’t build your hopes too high, Rab.”

“Why? Do you think my verses are too poor for the great Mr. Creech?”

“No, no! But Creech publishes only the most elegant writers. I don’t know that he would look too kindly on the Scotch dialect. . . He holds court every morning. Creech’s Levees they’re called. The first wits and scholars i’ the Town gather there. Nothing can hold a candle to them for wit and learning.”

“I’m hoping that my Lord Glencairn will maybe do something for me by way o’ patronage.”

“Glencairn! You’re moving in exalted circles now! Creech used to be some kind of a companion and tutor to the Earl o’ Glencairn: travelled abroad wi’ him, I believe. If my lord takes notice of you, you’re made. Creech’ll fall on your neck.”

“I would like to have my poems published without anyone’s assistance. But I’m told that’s no’ the way to go about things.”

“That’s true: without influence you’ll get nowhere. Everything’s influence here. . . You’ll be tired after your long ride?”

“Tired enough. I’d a night o’ dissipation on the road here: I don’t want to see drink for another year. . . Jock: how long did it take you to get used to the smell o’ this place? No: I mean the whole Town. The one place seems to smell worse than the other. . .”

“You soon get used to the smells: except on a right hot day; and then when they start throwing the slops over the windows it can be wicked. You’ve got to keep to the main streets after dark or you might get yourself into a hell o’ a mess.”

“You mean that they just open the window and throw everything out?”

“What else would they do? They’ve got to throw it somewhere: they canna keep it in the house—unless them that hae gardens. Of course they get fined if they’re caught throwing muck out the windows—but everybody takes the risk. You’ll get used to it. You see, there’s not a hole or corner in the Town but has got somebody living in it. Plenty down in cellars below the street level, without windows or a damned thing. Aye; and you’ll find pig-styes right in the highest attics: so that when the beasts get ready for the knife they’ve got to lower them down to the ground wi’ ropes. It cost me a bit o’ influence to get in wi’ Mrs. Carfrae. She’s an auld bitch like a’ landladies; but she could be a lot worse. For God’s sake dinna go near the bawds up the stair or she’ll fling the pair o’ us out. Besides: there are better places; and you’re better to go as far away from where you bide as possible: that’s only sense——”

“The only sense about brothels, Jock, is to give them a wide berth. I’ve never been wi’ a bawd yet; and I never hope to be.”

“Don’t be too sure: there’s some fine lassies i’ the Town; and when you’ve paid for their favours they have no come-back on you; and that’s a big factor—as you should ken. I had my lesson wi’ Jenny Surgeoner: I don’t need another.”

“Whatever you say, Jock: we won’t quarrel about that: or anything else. You’re free to go your way and I’m free to go mine. I don’t know that I’m going to like this place: I’m going to miss the caller air for one thing.”

“Don’t worry, Rab: once you’ve had a night’s sleep and a look round the Town in daylight, you’ll think differently. I was hame-sick when I cam’ here at first. By God I was hame-sick! And that’s when you’re damned glad to go to a bawd. At least she’ll speak kindly to you; and you can speak to her; and you can forget that you’re paying her. A human being needs company in a place like this more than in Machlin; and sometimes that’s the only way you can get company. Aye; and you could get a damned sight worse. Besides, everybody does it here. They have different values on such things than they have back hame. Folk are sensible here: civilised. Damnit, I hardly ken a man that doesna pay a regular visit to his own particular house.”

“Are there as many houses as that?”

“There’s thousands o’ bawds in Edinburgh: thousands! That’s no exaggeration. I could take you to a dozen houses in the Landmarket alone. Some are damned particular: it’s no’ everybody they’ll let in. A lot o’ them you’ve got to be introduced into; and vouched for. Some o’ them are harder to get into than a Masons’ lodge. You don’t judge by Machlin standards here, Rab. Aye; and some of the ministers are as bad as onybody else: you want to be here when the General Assembly’s meeting. . . And then the hypocrites go back to their parishes and rate poor devils for a simple houghmagandie ploy.”

“I’ve heard tell o’ the wickedness o’ Edinburgh. I never thought it was as bad as you suggest.”

“You’ll see for yourself.”

“So we’re just a lot o’ puir gulls in the country?”

“You’re no gull, Rab. You’ll soon find your feet; and when you do you’ll no’ want to go back to the plough: you’d be a fool if you did.”

“You don’t paint a pretty picture, Jock.”

“You’ll need to forget a’ about pretty pictures, Rab: sentiment doesna count here. Life’s a grim struggle for lads like you and me; and we’ve got to fight with every weapon we can lay our hands on. If you go down there’s nobody weeps for you: or cares. And why should they? There’s no money in it.”

“And money’s the talisman?”

“You see how far you can go without it. I ken I’ve got to make every bawbee I earn a prisoner. If you have to take to your bed wi’ an illness, unless you have money, they’ll let you lie till you die: if they don’t throw you out into the gutter to die there!”

“So it’s not surprising that they let puir Fergusson die?”

“Don’t say ocht about Fergusson wi’ the literati here. They hate the very mention o’ his name.”

“Oh, they do?”

“Fergusson was only a poor scrivener; and he made the mistake of insulting Henry MacKenzie: see that you don’t make a like one.”

“I mean to pay my respects to Henry MacKenzie; but first I’ll pay my respects to Robert Fergusson: or to where his last remains were cast into the earth. I don’t suppose they were laid there with any pious reverence. But never heed me, Jock: we’ll have some good nights together in this same stinking Auld Reekie. I’ll maybe have to go back to the plough some day; but before I do I mean to enjoy myself. I must confess that when I rode into Embro this afternoon . . . and the great bustle o’ folks and not one of them paying the slightest attention to me, I thought that my poetry would hardly affect them either.”

“I’m glad it’s you that’s saying that, Robert, and no’ me; for the truth is that there’s nobody gives a damn about poetry here unless it’s the poets themselves . . . and the critics. Since poetry neither fills bellies nor purses, why should they?”

“What’s come over you since you left Machlin? Something’s hurt you, Jock. You’ve become hard in your judgments. Are things no’ prospering wi’ you? You don’t need to tell me if you’d rather no’.”

“Maybe I’m a bit bitter nowadays. You’re a success: our old friend Jamie Smith’s gotten a good partnership in Linlithgow. I’m just a lawyer’s clerk working my fingers to the bone for a miserable pittance. No: don’t think that I grudge you or Smith your success: I’m more nor pleased about it: especially you, Robert. You’re a genius; and you’ve more right to success, to fame and fortune, than ony other man I know. Only I don’t see you getting justice. I came to Edinburgh wi’ high hopes; and I see you’ve come the same way. But I ken what goes on; and you dinna. But go forward your own way and maybe things will turn out for the best: I don’t suppose they could be worse than Mossgiel.”

“We’ll see, Jock, we’ll see. I’ve kent misfortune a’ my days. I don’t think I’ll start shedding tears now.”

“You’ll be all right. I wish I had half your chance. Well. . . I’ve to get up in the morning and get along to Willie Wilson’s desk. Come on: we’ll get away up to bed.”

Night had settled down on the capital of Scotland, the Athens of the North. . . A cold biting darkness it was. This side of the Ural mountains the wind sprang up and swept across the snow-deep steppes of Russia and the frost-iron plains of Europe; from its sweep across the North Sea it gathered a keenness and a new vitality to attack the great stone-scaled dragon that crouched on the ridge of the rock that was Edinburgh. It clawed at the serrated stone scales with a cold ferocity: it lashed and tore at the beings who huddled there.

The Town Guard, muffled to the ears, came down from the Castle: the wind whipped the drum-beats from the glinting skin and scattered them through the wynds and closes.

It was the official signal that the day had ended. From the howffs and the taverns folks muffled themselves up and bent their heads to the homeward journey.

Before another hour had passed the great dragon crouched on the ridge was asleep. The blade-keen winds howled and moaned and shrieked and clawed at the rattling pantiles. Only in some of the clubs and taverns did parties sit drinking and eating. The bulk of folks, their work before them in the morning, were snug abed.

Stretched on the chaff bed beside John Richmond, the Bard lay listening to the howling winds, though sometimes a busy bawd, entertaining a more than usually boisterous customer upstairs, distracted him with the fear that the ceiling might come down on top of him. His own thoughts were distracting enough. It seemed like a century since he had said good-bye to Jean Armour in the Cowgate of Machlin and taken the long hilly road to Muirkirk; and it seemed that nothing short of a century must elapse before he became familiar with the strange new life the city offered.

But before he slept he remembered Jean Armour and thought of her lying in the Cowgate with a twin in either arm. His heart softened towards her: softened and melted. He was far from her now; and it might be a long time before he saw her and the twins again. He had no regret that he was legally free of her. But he knew he would miss her: that no matter what happened in this life he would never again be able to shut her out of his mind. She would always be there to haunt him. Haunt him with her body and the music of her voice: with the memory of those nights they had spent together beneath the green thorn tree by the banks of the river Ayr. . . Nor would all the melody in Scotland ever drown the haunting measure of that slow strathspey she had lilted to him. No: whatever happened to him there would always be Jean Armour . . . and the twins. Robert and Jean: she had paid him double as he might have known she would. Jean Armour and he had not given their love by halves. Doubly they had loved: doubly their love had borne fruit.

And yet the love and the fruit of it belonged to the past. There was nothing but the memory of it for the future. Nothing but a memory that carried with it an agony in the core of its longing.

But there was agony at the core of life as he knew only too bitterly. Why had death come the way it had to Mary Campbell? His blood ran cold at the thought of her, at the senseless pitiless cruelty of her dying. What had she thought of him before she died? The agony of her longing must have been terrible. But he would never know. Here lay the burning hell of his torment. He would never know what poor Mary had suffered in her bitter brutal death. If only he could have spoken to her once before she died. If only he could have assured her that the thought to betray or desert her had never once found a lodgment in his brain. . .

He groaned involuntarily and turned on his side. . . The wind howled and shrieked through the grey town and bawds plied their trade for the hunger of men for their bodies never ceased. Always man craved to be free of the agony that was at the core of life; and only with woman could he share the agony of creation, however corruptly and unequally divided the sharing might be. . .

If only men and women would cease to bind life with their petty laws. If only men would free themselves from the menace of morality and realise that the laws of life were more profound than the depths of man’s mind. Life was but an endless dance of endless patterns. No one had yet been able to solve the riddle of the patterns. But the measure of the dance was knowable: this was the deepest knowledge to which man could attain. When a man and a woman danced against the measure there was confusion and unhappiness. When they danced to the measure the harmony of life was restored and there was deep fulfilment. Yet to find the measure of life’s dance, man had to be free; and the evil was that everywhere he was in shackles and in thrall. And while one human being remained in thrall, mankind could never be wholly free. . .

The truths of life were simple profound and clear. Only the lies of life were strange and shallow and confused. Herein lay the terrible evil of morality: it sought to give the sanction of law to the lies of life. . .

Once more in the circle of his thoughts he had encompassed the riddle of the universe. To-morrow when he awoke he would find the circle broken. But in daylight or in darkness he must cling steadfastly to his simplicity and clarity; and profundity might be added unto him.

Slowly the wheel of his thoughts ceased to turn. . .

James Dalrymple, the Ayrshire Squire of Orangefield, was a man of his word. He took the Bard out to Coates House (it was but a short walk) and introduced him to his kinsman James Cunningham, Earl of Glencairn.

The Earl was good-hearted, good-looking and he wasn’t over-clever. He liked the Bard. He insisted that he stay for a meal, meet his mother the Dowager-Duchess and his sister Lady Elizabeth.

The Dowager had a hard unemotional face and a hard unemotional voice. She was somewhat given to religion. But she spoke sparingly.

“Tak’ your meat, Mr. Burns: it’ll stick to your ribs when words winna.”

Lady Betty, on the other hand, was soft and coy. She was young and life had treated her gently.

“I thocht your verses on the Mountain Daisy so filled with sensibility, Mr. Burns. . .”

The Dowager clattered her spoon unceremoniously on the table and rifted with loud but evident satisfaction.

When the Bard took his leave, the Earl said: “I’ll tak’ you to Willie Creech’s myself. I’ll send word to you. We’ll fix you up somehow, Burns. We canna let the Bard o’ Ayrshire down. Na, na. . .”

Robert took an immediate instinctive liking to James Cunningham. It was difficult for him to believe that a man of such rank and wealth could be so unaffectedly modest and warm-heartedly interested in his welfare. After all, he had nothing to give him; and the Earl had nothing to gain by taking him by the hand.

From early morning the Landmarket clattered with life—hummed, jostled, throbbed and hog-shouldered.

The wynds and closes emptied their life onto it in the morning even as they emptied their excrement onto it in the night.

In his shut-away narrow segment of Edinburgh the Bard was conscious of its jundying and hog-shouldering . . . and the interminable scliff-scliffing of feet in Lady Stair’s Close. . .

He emerged rather late in the morning from Baxters’ Close, almost colliding with a bleary-eyed bawd at the close-head. He grued; for he was not feeling well. The unaccustomed alcohol still played havoc with his stomach.

The Landmarket was cold and grey and bitterly wind-swept for it lay high on the ridge of the Rock. The booths and stalls that were put up close to the side-walk were bare and hungry and Decemberish enough for this time of the year. But they had potatoes and kail and a few turnips and plenty of leeks and some roots fresh dug that morning from the Portobello sandpits. . .

Had he been an unlettered rustic he would have stood and stared in wonder and awe. But he was a much-lettered rustic and his wonder and awe were of a higher order.

He had read much about Edinburgh—and even about London and Paris. Many things did not surprise him. But he thrilled to the active physical contact of Edinburgh; its cobbled causeways; its high tenement lands piled stone on stone to dizzy heights; its noises and stinks and smells. And above all: its humanity.

The citizenry of Auld Reekie were an amazingly diverse yet homogeneous lot. All classes intermingled and jostled and yet did not quite mix. There was every variety of dress and clothes imaginable. Many clung to the styles (and perhaps to the actual garments) of half a century ago. Some were in the latest fashion. And so many of the very poor were clad in the patched cast-offs of the wealthier class. . .

Such Landmarket (and Gosford’s Close) personalities as James Brodie, the surgeon, John Caw, the grocer, and John Anderson, the wig-maker, could and did exchange pleasantries whenever and wherever they met. Even James Home Rigg, Esquire, of Morton, having a chat with General John Houston, would bow to Mrs. MacPherson who, though a landlady, described herself as a setter of elegant-rooms and who was considered a distinct cut above Mrs. MacLeod who let rooms in the same close. Nor was it thought amiss that Robert Middlemist, the dancing master, stood laughing and joking with Mrs. Robertson who kept “the best ales.” They were more than citizens: they were all inhabitants of the vertical street that was called Gosford’s Close, emptying on to the Landmarket. Stephen Clarke, the organist of the Episcopal Church, might not care very much for James Leishman, the bookbinder; but both were very civil to Mrs. Harvey, the writer’s wife.

The Bard, as he slowly sauntered down the Landmarket, could not tell General John Houston from organist Stephen Clarke, nor had he any means of knowing that they both lived in the same dark smelly turnpike-staired vertical street, with slum-dwellers on the ground and slum-dwellers in the attics and with various grades of gentry in between.

But he was aware of a close familiarity between many of the folks who jostled about the narrow side-walks or who exchanged greetings or conversed on the causeway: conscious of the fact that pools of human friendship or neighbourliness gathered on the edge of the general stream of human indifference.

He sauntered slowly down to the Luckenbooths—that long rectangular block of narrow buildings (the locked booths of the merchants) that almost blocked the street in front of the four kirks that huddled beneath the crown spire of Saint Giles’s. . .

In front of the Luckenbooths (and attached to them) stood the Tolbooth—the grim prison where so many famous and infamous Scots had dreed their weirds, and where, even as the Bard passed it, languished many debtors and felons in incredible dirt darkness and pestilential foulness. Yet such was the thickness of its walls that nothing of the human misery and suffering seeped through to the passers-by. In the stillness of the night weird and pitiful shrieks and groans sometimes emerged half-strangled from the narrow slits of windows. . .

But the Bard was conscious of outlines and façades in a generalised way: the scene was too variegated and diversified for him to note (and relate) the details.

He went down through the Buthraw between the booths and the close-mouths on the left side of the High Street. He now emerged onto the broadened High Street at its greatest breadth. Here faced the east gable-end (and entrance) to Creech’s Land and, in the Saint Giles’s corner, the main entrance to the Parliament Close. Though Creech’s Land dated back to the year 1600 the wretched Luckenbooths to which it was attached dated back to the year 1400.

A couple of hundred yards from Creech’s Land and a little to the right side stood the Mercat Cross, the centre of Edinburgh and hence, in a very true sense, the centre of Scotland.

Already, for the morning was wearing on, there was a great crowd of people, apart from the ebb and flow of traffic, gathered round the Cross. It was an extraordinary crowd of people; but then it was rather extraordinary that here (unless the weather were too inclement) the business and gossip of the Edinburgh morning was done. Almost anybody of even the least consequence could be found about the Cross between eleven and twelve o’clock on every working day. At twelve o’clock there was a general break-up and men moved off to their respective howffs to enjoy their meridians!

As the Bard emerged from the narrow Buthraw the morning session of gabble and gossip was at its height.

Some chatted gaily and some discoursed gravely and many listened with an anxious and attentive ear cocked over two or three twists of knitted cravat. It was a raw morning and hats were well pulled down where wigs allowed. And what a variety of hats there were: cocked hats, three-cornered hats, beaver hats, hats trimmed with lace, slouch hats, hats with brims that drooped and hats with brims that curled—and some blue-bonnets. All, except the blue-bonnets, sitting or perched on as wide a variety of wigs.